Abstract

Since pulmonary nontuberculous mycobacteria (PNTM) lung disease was last reviewed in CHEST in 2008, new information has emerged spanning multiple domains, including epidemiology, transmission and pathogenesis, clinical presentation, diagnosis, and treatment. The overall prevalence of PNTM is increasing, and in the United States, areas of highest prevalence are clustered in distinct geographic locations with common environmental and socioeconomic factors. Although the accepted paradigm for transmission continues to be inhalation from the environment, provocative reports suggest that person-to-person transmission may occur. A panoply of host factors have been investigated in an effort to elucidate why infection from this bacteria develops in ostensibly immunocompetent patients, and there has been clarification that immunocompetent patients exhibit different histopathology from immunocompromised patients with nontuberculous mycobacteria infection. It is now evident that Mycobacterium abscessus, an increasingly prevalent cause of PNTM lung disease, can be classified into three separate subspecies with differing genetic susceptibility or resistance to macrolides. Recent publications also raise the possibility of improved control of PNTM through enhanced adherence to current treatment guidelines as well as new approaches to treatment and even prevention. These and other recent developments and insights that may inform our approach to PNTM lung disease are reviewed and discussed.

Nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) are species other than the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex (MTBC) and Mycobacterium leprae. Molecular biologic techniques have facilitated recognition of > 140 species of mycobacteria, many nonpathogenic for humans. The pulmonary NTM (PNTM) species most commonly implicated in human disease in North America are Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC), Mycobacterium kansasii, and increasingly, Mycobacterium abscessus. Since NTM were last reviewed in CHEST,1 our understanding of these organisms has expanded in potentially important ways. This review provides background for several important areas related to PNTM and then focuses on new insights generally published since 2008. We emphasize disease in ostensibly immunocompetent patients and concentrate on the most clinically important species encountered in North America because these insights may also inform our understanding of other species.

Epidemiology

NTM are ubiquitous in the environment and normal inhabitants of natural and drinking water systems, pools and hot tubs (able to survive chlorination), biofilms, and soil. Infection is accepted to occur from the environment; person-to-person spread is believed not to occur. Although exposure and infection (as shown by skin test surveys2) is nearly universal in some locales, PNTM occurs in a minority of those infected. Capturing accurate data to estimate PNTM incidence and prevalence is challenging because PNTM is not reportable to public health authorities, and disease diagnosis requires satisfying a constellation of criteria,3 often necessitating extended patient follow-up.

Recent Insights

Prevalence:

The mere presence of NTM in sputum does not equate with disease. This notwithstanding, the annual prevalence of PNTM is increasing as consistently demonstrated by population-based estimates,4 large inpatient databases,5 and Medicare records.6 An analysis of a 5% sample of Medicare Part B beneficiaries calculated a US prevalence (as defined by diagnostic codes on medical claims) of 47 cases per 100,000 population in 2007, with an annual increase of 8.2% per year from 1997 to 2007.6 Similar experience has been reported in Canada7 and areas outside North America, although species have differed, with Mycobacterium xenopi, Mycobacterium malmoense, and Mycobacterium simiae being significant species.8,9 Studies have also variously emphasized the importance of environmental factors, such as climate and soil composition; age; comorbid conditions, particularly cystic fibrosis (CF), COPD, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and rheumatoid arthritis; and immunosuppressive therapies. US prevalence varies by ethnicity, with Asians and Pacific Islanders having the highest prevalence and blacks the lowest. Whites were the only race with women having a higher prevalence than men. Comorbid conditions, especially involving the lungs, were more common among PNTM cases, and individuals with PNTM were 40% more likely to die over the study period than those with PNTM. Adjemian and colleagues10 also described variability of PNTM by geographic locale, ranging from > 200 per 100,000 in some western states (Hawaii was highest) to < 50 per 100,000 in some Midwestern states. The geographic distribution of PNTM among patients with CF has shown a similar pattern. Factors predicting high-risk PNTM areas are greater population density, higher income, and greater evapotranspiration.11 Current prevalence studies differ from original reports that the highest NTM prevalence is in the southeastern United States, perhaps reflecting the evolution of PNTM diagnostic criteria, an overall increase in detection due to increased awareness, or improved microbiologic detection techniques.

Transmission and Pathogenesis

The environment has been the historically accepted source of NTM disease transmission. Sequencing of NTM DNA obtained from households of patients with PNTM has shown that in many instances, the NTM from the patient has the exact fingerprint as an isolate obtained from his or her household plumbing.12

Host immunity to NTM includes both systemic and local factors and has been reviewed.13‐15 Mycobacteria are inhaled and initially subject to both local clearance factors and systemic innate immune defenses. Mycobacteria are processed by alveolar macrophages, which release cytokines, including IL-12 and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), augmenting innate immune responses. Macrophages also present mycobacterial antigens on their surface, signaling T lymphocytes to differentiate into T-helper cells producing antigen-specific immunity, including natural killer cells, which further augment host defense. Other important elements involve natural killer cell killing of infected macrophages and IL-8, which supports phagocytosis. Ultimately, mononuclear cells and epithelioid histiocytes surround foci of infected macrophages, resulting in the classic histopathologic granuloma. Given the ubiquitous nature of NTM, infection is common. PNTM, however, is not because NTM generally are not highly virulent, and host defenses typically prevent progression to disease.

Recent Insights

Source of NTM Infection and Disease:

Evidence for person-to-person transmission is building, at least in the CF community. Whole-genome sequencing and drug susceptibility patterns of M abscessus isolates from patients with CF attending the same UK CF center were reported to show patterns highly suggestive of person-to-person spread, including drug-resistant strains.16 At a Seattle CF center, an outbreak was implicated when M abscessus subspecies massiliense (Mam) developed in the sputum of four patients with previously negative acid-fast bacilli (AFB) cultures after a patient with a long history of Mam PNTM and more than four AFB-positive sputum cultures had transferred to the center. Isolates from all five patients were indistinguishable by molecular analysis.17 All patients had overlapping clinic visit days with the index case, although no shared space or social interaction was identified. It was hypothesized that direct patient-to-patient transmission was unlikely, but indirect transmission through fomites could not be excluded. Complicating matters is the recent observation of high-level molecular relatedness between strains recovered from these two distinct CF outbreaks on two continents, raising the additional possibility of genetic variants of M abscessus that may facilitate infectiousness.18

Predisposing Factors

Recent Insights

Body Habitus:

Dirac and colleagues19 reported a study of 52 matched pairs of healthy control subjects and patients with pulmonary MAC (PMAC) disease. PMAC was more closely associated with low BMI, thoracic skeletal abnormalities, preexisting COPD, and steroid use than were home water sources and activities likely to generate water and soil aerosols.

Genetic Predisposition:

The hypothesis that there is a genetic predisposition to allow for PNTM to develop is supported by the observation that many affected patients with nodular bronchiectasis (NB) PNTM fit a stereotypical phenotype. Kim and colleagues20 reported that in a referral cohort of women with NB PNTM, a tall, lean body habitus; scoliosis; mitral valve prolapse; and pectus excavatum are common, raising the possibility that fibrillin abnormalities are a pathogenic factor. Additionally, 36.5% of the cohort expressed at least one CFTR gene mutation, often without other stigmata.20 Colombo and colleagues21 studied 120 patients with PNTM for familial clustering of the disease. Six families with at least two members with PNTM were identified and assessed by history and by laboratory and radiographic testing. The majority of cases were sibling pairs of white patients who did not smoke. These patients also manifested a high prevalence of scoliosis, and five of 12 patients in whom CFTR gene analysis was performed had single-allele mutations.

Immune Factors:

An autopsy study compared 11 patients with intact immune systems with patients with PNTM and five patients with disseminated NTM (DNTM) disease due to primary immunodeficiency involving the interferon-γ/IL-12 axis and demonstrated differences in histopathology among these groups.22 All patients had positive cultures for NTM (primarily MAC and M abscessus) within 6 months of death. Patients with PNTM were predominantly women with histopathologic findings, including well-organized necrotizing and nonnecrotizing granulomatous inflammation; a few had diffuse granulomatous consolidation. When present, mycobacteria were scant and were identified within bronchial walls at the edge of the granulomas. Patients with DNTM (primarily MAC) were all men, and pulmonary granulomatous disease was uncommon and characterized by poorly organized granulomas. Mycobacteria were more numerous and seen within macrophages and multinucleated giant cells. The findings suggested that patients with PNTM have impaired airway surface defenses, resulting in disease limited to the chest, whereas patients with DNTM have little chest involvement presumably because of intact local defenses.

Vitamin D modulates innate immune response by stimulating cathelicidin production by granulocytes and macrophages, which destroys the lipoprotein membrane of mycobacteria.23 Severe vitamin D deficiency (< 10 ng/mL) has been reported to be independently associated with PNTM lung disease.24

Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) improves T-helper 1 phenotype differentiation25 and production of IL-2,26 creating a milieu that mediates killing of mycobacteria-infected macrophages. In a single-center cross-sectional analysis, albumin-bound levels of DHEA were, independent of BMI, significantly lower in women with pulmonary M avium compared with age-, sex-, and racially matched control subjects,27 raising the question of whether low levels of DHEA might predispose some women to PNTM.

Ciliary Abnormalities:

PNTM is prevalent in patients with genetic disorders of mucociliary clearance, such as primary ciliary dysfunction (PCD) and CF, suggesting that aberrant mucociliary function may be a predisposing factor in acquiring PNTM disease. Fowler and colleagues28 studied ex vivo respiratory epithelial ciliary function in 58 patients with PNTM due to MAC, M abscessus, or M xenopi compared with cilia from eight patients with PCD, five patients with CF, and 41 healthy control subjects. The cilia in patients with PNTM showed intermediate results between the control and the PCD and CF groups with respect to ciliary beat frequency and responses to Toll-like receptor agonists; function did not correlate with abnormalities of CF transmembrane conductance regulator or the presence of NTM. Nasal nitric oxide production, known to affect ciliary beat frequency, appeared to be reduced compared with normal patients but greater than in patients with PCD.

Iatrogenic Risk Factors:

The increasing prevalence of PNTM coincides with more widespread use of immunosuppression to treat a variety of conditions. Use of agents that inhibit TNF-α (ie, infliximab, etanercept, adalimumab) has been appreciated as a particular risk factor for NTM disease. Winthrop and colleagues29 analyzed data from a US Food and Drug Administration postmarketing questionnaire to identify patients with NTM disease using anti-TNF-α drugs. In 239 reports, the pulmonary region was the most common site involved (56%). M avium was identified in about 50% of cases and M abscessus in 11.4%. Confirmed PNTM infection was statistically more likely to develop in patients who were using concomitant prednisone, methotrexate, or both than in those not receiving these additional medications; female sex and rheumatoid arthritis were also associated with PNTM. Reports of PNTM due to other species, including M xenopi,30 and in the setting of various transplants17 are also becoming more common.

Bacterial Virulence:

Certain species appear to be associated with greater morbidity than others.8,9 Mycobacteria have high genetic diversity, even within species,31 and varying virulence could be part of this diversity. Tatano and colleagues32 compared in vitro virulence of five strains of M avium isolates from patients with NB with five strains isolated from patients with cavitary PNTM, a form of disease associated with higher mortality,33 to determine whether differences in virulence correlated with different patterns of disease. No significant differences were found among any of the strains tested with respect to cellular internalization, replication within human type 2 alveolar cells and macrophages, or macrophage production of reactive nitrogen or oxygen species or susceptibility to either of these macrophage antimicrobial mechanisms.32

Clinical Considerations

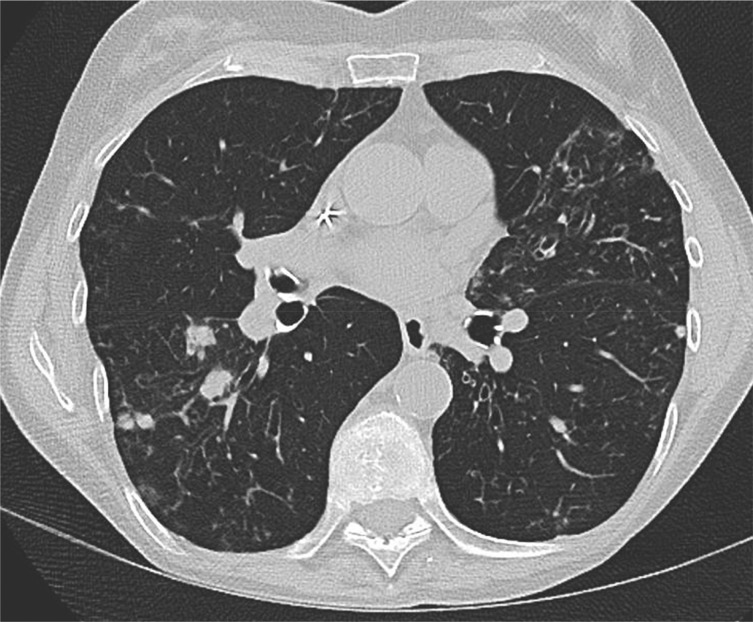

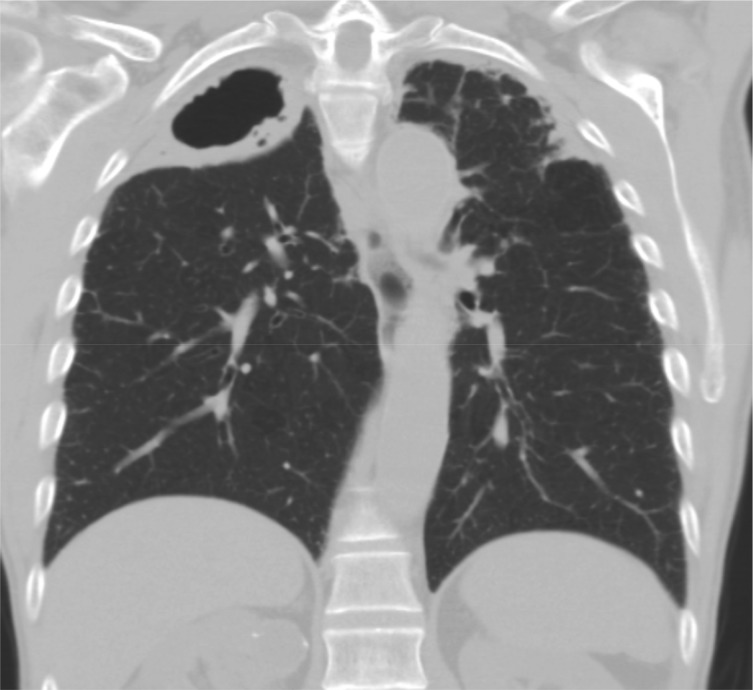

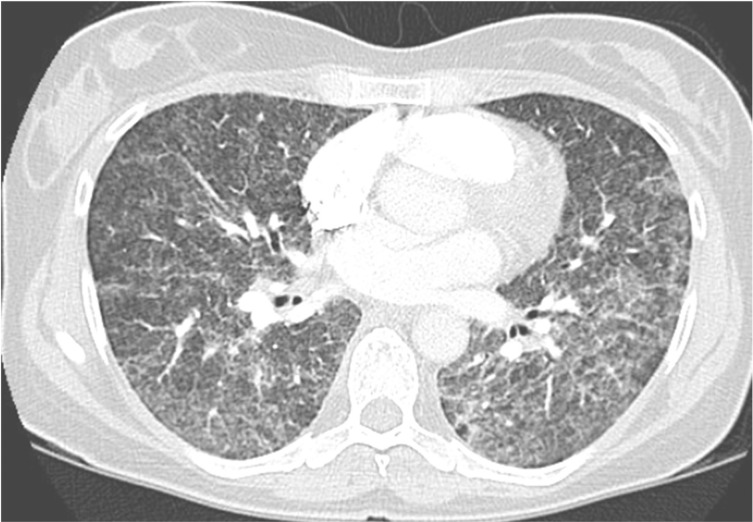

Most PNTM present in one of three prototypical phenotypes: (1) NB (Figs 1, 2), which is commonly seen in women who are postmenopausal, tall, thin, and nonsmokers with no history of lung disease and often with scoliosis or other thoracic abnormalities, where cavities may occur late and tend to be small; (2) a TB-like pattern involving the upper lobes, often with cavities (Fig 3) and classically seen in men with a history of smoking and, often, COPD; and (3) least commonly, hypersensitivity pneumonitis (sometimes called “hot tub lung”), which can occur after exposure to NTM in hot tubs,34,35 swimming pools, medicinal baths, and other settings with concentrated aerosolized NTM, such as metalworking fluids.36 Symptoms and radiographic presentation (Fig 4) of this form are indistinguishable from other forms of hypersensitivity pneumonitis.

Figure 1 –

Chest CT image of a 70-y-old woman with a tall, lean body habitus; mitral valve prolapse; and a single CFTR gene mutation (G551D). She has an intermediate sweat chloride test result and presented with a chronic debilitating cough. Sputum cultures were positive for Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare complex. The CT image demonstrates multiple nodules bilaterally with patchy bronchiectatic changes and tree-in-bud abnormalities (arrow).

Figure 2 –

Chest CT image of a 65-y-old woman who presented with productive cough, weight loss, and fatigue. Sputum was acid-fast bacilli smear positive and culture positive for Mycobacterium abscessus. This CT image shows a more advanced stage of bilateral nodular bronchiectasis than seen in the patient presented in Figure 1.

Figure 3 –

Chest CT coronal view image of an 81-y-old man with COPD, cough, and sputum showing a large right-side upper-lobe cavitary process with bilateral apical pleural thickening. Multiple sputum specimens were acid-fast bacilli smear negative, but cultures were positive for Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare complex.

Figure 4 –

Chest CT image of a 47-y-old woman with diffuse reticulonodular infiltrates bilaterally. The patient presented with acute onset of cough, dyspnea, and low-grade fever after swimming. A diagnosis of hypersensitivity pneumonitis was made, and etiology was traced to Mycobacterium avium exposure at the pool.

Symptoms of NB and cavitary PNTM disease are similar regardless of the demographic group affected37 or causative species. One-half of patients experience symptoms for > 1 year before diagnosis, the majority experience cough; fatigue, dyspnea, low-grade fever, and weight loss are common; and hemoptysis and chest pain occur less commonly. Symptoms of comorbid conditions may be present.

Recent Insights

General:

A review of 1,255 patients suggested that worldwide, M xenopi may be increasingly associated with the cavitary form of PNTM. Patients generally fit the profile of being middle-aged men with a history of COPD or prior TB.38

Prognostic Factors:

A retrospective study in 634 Japanese patients without HIV but with newly diagnosed PNTM disease due to MAC39 (mean age, 68.9 years; 59% women; median follow-up, 4.7 years) reported that only 27% received therapy within 6 months of diagnosis. Of these, 24%, 19%, and 57% were treated with one, two, or three or more drugs, respectively. Five- and 10-year MAC-specific mortality was 5.4% and 15.7%, respectively. The presence of fibrocavitary features at the time of diagnosis portended worse survival than the NB pattern alone. Additional negative prognostic indicators were BMI < 18.5 kg/m2, anemia, and elevated C-reactive protein level.39

The significance of more than one mycobacterial species in the same patient has been uncertain. A recent report considered 53 patients encountered over a 12-year period who received treatment for MAC PNTM and had M abscessus subspecies abscessus (Maa) isolated during therapy.40 Twenty-one had clinically significant Maa infection (ie, multiple positive cultures and clinical and radiographic deterioration after initial improvement with MAC therapy), and 32 were without clinically significant Maa infection. Patients with clinically significant Maa infection had more positive cultures and were more likely to show worsening radiographic features, including new or enlarging cavitary lesions. Patients without clinically significant Maa disease were more likely to have only a single positive Maa culture. This study suggested that coinfection with Maa in patients with MAC PTNM may not be unusual and may be important prognostically and that readily discernible clinical parameters may herald polymicrobial disease.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of PNTM is made from a constellation of clinical, microbiologic, and chest imaging findings (Table 1).3 Skin testing and interferon-γ release assays are not useful in diagnosing PNTM, although they may be helpful in excluding disease due to M tuberculosis. Culture is the gold standard for the identification of NTM, and two or more specimens confirming a species are preferred. Sputum and BAL are the common specimen sources; less often is tissue biopsy specimen. Like TB, NTM are slow-growing relative to many other bacteria; even rapidly growing species may take days to 1 week to grow in culture. Initial species identification involves observation of growth rate, colony morphology, and color. Final species identification uses chemical and biologic testing. Nucleic acid probes (AccuProbe Inc) and sequencing of specific genes are available to identify some species of NTM. The role of in vitro antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST) for PNTM, particularly for initial (ie, primary) isolates, remains an issue of some debate, although it is usually recommended for certain species and for recurrent infections or failing therapy (Table 2).

TABLE 1 ] .

Diagnostic Criteria for PNTM Disease

| Criteria | Findings (Some or All May Exist) |

| Symptoms | Cough, productive or nonproductive Fatigue Weight loss Fever Hemoptysis Chest pain |

| Radiographic | Chest radiography: cavitary opacities, small nodular opacities, or both with or without bronchiectasis (latter should be confirmed by HRCT scan) HRCT scan: multifocal bronchiectasis with or without small nodules, tree-in-bud opacities, cavities |

| Microbiologic (three or more sputum specimens examined for AFB and culture) | Two or more positive cultures from expectorated sputum or One positive culture from BAL or wash or Transbronchial or other lung biopsy specimen demonstrating granulomatous inflammation or AFB plus one positive culture for NTM (sputum, lavage, wash, or biopsy specimen) |

| Comments | Bronchoscopy for wash or lavage should be pursued for patients in whom a diagnosis of PNTM is suspected but sputum cultures are negative. Patients who are suspected of having PNTM but do not meet diagnostic criteria should be monitored closely until PNTM is established or excluded. NTM should be identified to the species level and in some cases, to the subspecies level. Other atypical radiographic findings (eg, solitary pulmonary nodule) may be seen. |

The diagnosis of PNTM disease should meet all of the following criteria: symptoms consistent with mycobacterial disease, radiographic abnormalities, microbiologic findings, and exclusion of another diagnosis (eg, TB, fungal disease). AFB = acid-fast bacilli; HRCT = high-resolution CT; NTM = nontuberculous mycobacteria; PNTM = pulmonary nontuberculous mycobacteria. (Adapted with permission from Griffith et al.3)

TABLE 2 ] .

Commonly Encountered Species Causing PNTM: An Approach to AST3

| Species | Primary Isolates | Primary Resistance, Failed Treatment, Recurrence, Reinfection |

| Mycobacterium avium complex (limited disease) | Clari1, a; monitor patients with intermediate-level MICs for emerging resistance | Amik, Clari,a EMB, Moxi,a Rifbn |

| Cavitary or extensive disease | Clari + Amika | |

| Mycobacterium abscessus2 | In vitro response to Clari may suggest subspecies identity | … |

| Subspecies abscessus or bolletii | Amik,a Cef,a Clari,1,3, a Imi,a Lin,a Min,a Moxi,a Tiga | Amik, Cef, Clari,1,3 Imi, Lin, Min, Moxi, Tig |

| Subspecies massiliense | Clari1, a | Clari,1, a Amik,a Cef,a Imi, Lin,a Min, Moxi,a Tig |

| Mycobacterium kansasii | Rif1, a | Amik,a Clari,1, a EMB,a INH, Moxi, Rifbn,a Sulfaa |

| Mycobacterium fortuitum | Amik,a Cipro,a Clari,3, a Imi,a Lin,a Sulfa | Same + Cef, Doxy, Min, Moxi |

| Mycobacterium chelonae | Clari,a Tob, Imi | Same + Amik, Doxy, Moxi |

| Mycobacterium malmoense4 | INH,a Rif, EMB ± Clari, Moxi | Same |

| Mycobacterium simiae | Clari,a Moxi | Same + Amik, EMB, Sulfa |

| Mycobacterium szulgai | AST standard anti-TB medications | Same + Clari, Moxi |

| Mycobacterium xenopi4 | No AST, empiric Rx Clari, Rif, EMB | Moxi, Clari, Rif, EMB, Strep, Lin |

Broth microdilution method is recommended as the gold standard for performing AST of NTM. 1, Class = results representative of other drugs in class; 2, identify to the subspecies level; 3, should be studied ≥ 14 d to assess for inducible erm-related macrolide resistance; and 4, may require extended incubation. Amik = amikacin; AST = antimicrobial susceptibility testing; Cef = cefoxitin; Cipro = ciprofloxacin; Clari = clarithromycin; Doxy = doxycycline; EMB = ethambutol; Imi = imipenem; INH = isoniazid; Lin = linezolid; MIC = minimum inhibitory concentration; Min = minocycline; Moxi = moxifloxacin; Rif = rifampin; Rifbn = rifabutin; Sulfa = sulfonamide; Strep = streptomycin; Tig = tigecycline; Tob = tobramycin. See Table 1 legend for expansion of other abbreviations.

In vitro testing results may be difficult to interpret; other agents may be useful.

Recent Insights

First Positive Culture in CF:

A retrospective study of 96 patients with CF with a first positive sputum culture for NTM (overwhelmingly MAC, M abscessus, or both) and ≥ 1 year of follow-up reported that although 60% of patients had either transient or persistent NTM, they did not meet criteria PNTM because they did not have radiographic or clinical progression apart from that attributed to CF. Among the 40% deemed to have progressive PNTM, a lower FEV1 and more marked decline in FEV1 were present in the year before their initial positive NTM culture.41 The issue of whether PNTM contributed to accelerating CF or vice versa could not be addressed.

M abscessus:

Taxonomists continue to debate the classification of this species, which now appears to comprise at least three distinct subspecies (or species): Maa, M abscessus subspecies bolletii, and Mam.42 Because Mam usually has a truncated erm gene, rendering previously untreated Mam susceptible to clarithromycin, whereas Maa and M abscessus subspecies bolletii contain the complete gene and are usually (> 80%) resistant to macrolides, identification to the subspecies level and ≥ 14 days incubation with erythromycin to determine likely susceptibility of these rapidly growing mycobacteria is essential.42‐44

Rapid Detection:

A TaqMan real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay detecting the 16S to 23S ribosomal RNA internal transcribed spacer region of MAC directly from respiratory specimens was developed. When used in combination with real-time PCR testing for MTBC, the assay could guide management and reduce medical costs. Using culture as the gold standard, the combined real-time PCR assay for MTBC-MAC demonstrated a sensitivity, specificity, and positive predictive value of 71.1%, 99.5%, and 98%, respectively, for all specimens and was cost-efficient when compared with the AccuProbe.45 Average time to final identification with combined MTBC-MAC was 5 days; many specimens required < 2 days.

In Vitro AST:

Kobashi and colleagues46 investigated the relationship between AST and treatment outcome for MAC over a 6-year period. Sixty immunocompetent patients with MAC PNTM were treated with a four-drug regimen consisting of clarithromycin, rifampin, ethambutol, and streptomycin. Conversion to sputum negative occurred in 75% of patients after treatment. Low clarithromycin minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) was associated with strain eradication, but this relationship did not exist for rifampin, ethambutol, or streptomycin, suggesting that AST for clarithromycin may be uniquely valuable. Moreover, although most initial isolates for MAC were presumed sensitive to macrolide therapy, this was not universally the case.

Another study reviewed MIC of 462 consecutive MAC isolates to amikacin and established a resistance breakpoint of 64 μg/mL.47 All MAC strains that consistently demonstrated MIC > 64 μg/mL contained a mutation of 16S ribosomal RNA at position 1408. MAC strains that demonstrated MIC < 64 μg/mL exhibited the wild-type base pair in the same location. A consistent feature of isolates with MICs > 64 μg/mL was prior prolonged exposure to amikacin. Based on these results, the authors recommended primary AST of MAC isolates to amikacin using current MIC guidelines for M abscessus.

Treatment

Current PNTM treatment recommendations are based on available clinical studies and expert opinion and reflect experience with the more frequently encountered species.3 For treatment of less common species, regimens are commonly derived from case reports. General considerations regarding treatment are summarized in Table 3.

TABLE 3 ] .

Pulmonary NTM: Treatment Considerations

| Consideration |

| Treatment of most species is informed by experience with several common species and expert opinion |

| The species of NTM involved is predictive of the treatment outcome |

| In vitro antimicrobial susceptibility testing often uses critical MIC levels used for Mycobacterium tuberculosis; these may not be validated by or relevant to NTM |

| Antimicrobial susceptibility testing of primary isolates generally uses few drugs selected on a species-specific basis |

| More extensive susceptibility testing is recommended for rapidly growing mycobacteria, for failed treatment, or retreatment of all species |

| Macrolides are a key antimicrobials for treating many species of NTM |

| Pattern and extent of disease have important implications for the choice of treatment |

| Limited noncavitary nodular bronchiectactic disease of several common species uses therapy three times a week |

| Extensive and cavitary disease of all species generally requires daily therapy with multiple drugs; an injectable agent should be considered to supplement the initial phase of therapy |

| The duration of therapy varies |

| Initial therapy for most species is 12 mo postsputum conversion |

| Therapy of rapidly growing mycobacteria must be customized; suppression vs cure may be a reasonable goal for some patients and species |

| Therapy for recurrent disease or salvage cases must be individualized |

| Hard-to-treat species and refractory disease, if localized, may be candidates for surgical resection |

Recent Insights

Guidelines:

Although guidelines for NTM therapy are available2 and being validated,48 data show that physician guideline adherence is poor. Adjemian and colleagues49 reported a sample of 349 US physicians treating 915 patients with MAC or M abscessus PNTM. Less than 15% prescribed antibiotic regimens consistent with expert guidelines. This low rate of guideline adherence may reflect underestimation of NTM disease. An article from the Pulmonary MAC Outcomes group revealed that PMAC experts, more than nonexperts, perceive patients with a positive sputum culture for MAC to have disease. These experts estimated higher success rates with intensive therapy of new cases and were more likely to use intensive therapy and less likely to observe without treatment.

Therapy administered 3 days per week offers the theoretical advantage of improving tolerability and reducing medication expense. Preliminary, single-center data limited by variability in drug regimens suggested that an intermittent regimen could be effective in treating noncavitary PNTM due to MAC.50,51 Data from the same center also suggested that treatment of M kansasii three times a week would be effective for select patients. On the basis of these data, expert guidelines recommend intermittent therapy for patients with limited disease.3 A recent retrospective study of treatment-naive patients with noncavitary NB MAC lung disease reexamined this issue, comparing 118 patients receiving macrolide, rifampin, and ethambutol three times a week with 99 receiving the same regimen daily supplemented by streptomycin three times a week for the first 3 months of therapy.52 All MAC strains were deemed macrolide sensitive at therapy onset; there were no differences between groups regarding extent of smear positivity and time from diagnosis to treatment. After 12 months of therapy, neither symptoms nor high-resolution CT image changes differed between the two regimens. Likewise, sputum conversion rate, time to sputum negativity, recurrence rate, and acquired resistance patterns were not statistically different between groups. The daily group required significantly more therapy modifications. This study provides additional support for the recommendation of intermittent therapy of noncavitary PNTM due to MAC.

Choice of Macrolide:

A retrospective, single-center analysis of sputum response to guideline-directed triple-drug therapy containing either azithromycin or clarithromycin in 180 patients who were nonsmokers with NB due to MAC and who completed 12 months of therapy demonstrated no significant differences in the microbial responses between regimens.53 Patients given daily medication were more likely to change to three times weekly regimens due to GI side effects, but overall treatment success was achieved in 84% of patients. No macrolide resistance developed in any patients. Of note, recurrent disease was usually due to reinfection (ie, new strain) and occurred much later compared with relapse (ie, same strain isolated), averaging 17.5 and 6.2 months, respectively.

Inducible Macrolide Resistance:

Treatment response rates differ between Maa and Mam. In a study comparing treatment efficacy using > 12 months of clarithromycin-based therapy, including an initial 4-week course of cefoxitin and amikacin in 24 patients with Maa and 33 patients with Mam, sustained sputum negativity was achieved in 88% of patients with Mam but in only 25% of patients with Maa.54 Separately, CT scan findings before and after therapy showed that most patients with Mam had improvement compared with only one-third of patients with Maa.55 As noted previously, differing response to macrolide-based regimens among subspecies of M abscessus relates to the presence or absence of a truncated erm gene.42‐44 This raises the question of whether different macrolides equally affect erm induction. An in vitro study by Choi and colleagues44 compared both azithromycin and clarithromycin against Maa vs Mam. Over a 14-day in vitro exposure, no changes were seen in the azithromycin and clarithromycin MIC required to inhibit the growth of 90% of organisms for any of the Mam isolates. In vitro exposure of Maa to either macrolide induced resistance in all the isolates tested by day 14, although elevation of MIC was somewhat less after azithromycin exposure. Antimycobacterial activities were then analyzed in bone marrow-derived mouse macrophages and in a mouse lung model of M abscessus PNTM. Results were similar in that azithromycin reduced bacteria more than did clarithromycin in Maa infection, reflecting greater erm expression with clarithromycin exposure. The macrolides were equally effective against Mam. Although azithromycin may have some advantages over clarithromycin in treating Maa, further experience is required before any recommendation can be made.

Optimizing Drug Treatment:

In a retrospective study of 481 patients treated for PNTM MAC disease, pharmacologic analysis indicated that current dosing and drug combination strategies frequently result in a peak serum concentration (Cmax) below the MIC of macrolides and ethambutol in MAC isolates.56 Moreover, concomitant use of rifampin often led to reduced Cmax for macrolides and moxifloxacin. Cmax to MIC and area under the curve to MIC ratios were generally below bactericidal target levels for all these drugs.

Salvage Therapy:

Olivier and colleagues57 published an initial experience with adding inhaled amikacin to the regimens of 20 patients with MAC or M abscessus infection who had failed an average of 60 months (range, 6-190 months) standard treatment. Forty percent of the patients’ sputum cultures converted to negative after initiation of therapy and 62% of those patients’ cultures remained negative after a median follow-up of 19 months. A multisite randomized placebo-controlled trial of inhaled liposomal amikacin for the treatment of patients with refractory M avium or M abscess is ongoing.

Bedaquiline, a diarylquinolone the US Food and Drug Administration approved for TB, shows promise for treating refractory PNTM. A retrospective analysis of adding bedaquiline to the regimens of 10 previously treated macrolide-resistant patients with PNTM showed that at 6 months of therapy, 50% of patients had one or more negative cultures, and 90% had improvement of symptoms.58 No patient stopped the drug for adverse events.

Prevention:

Macrolides are being prescribed for long-term use as single agents because of their antiinflammatory effect in patients with CF. Given the prevalence of NTM infection in these patients, concerns have been raised regarding the prevention of NTM and promoting resistant NTM infection. In a nested case-control study of > 6,500 patients with CF and negative AFB cultures before entry, 191 patients had first positive NTM cultures during the study for either MAC or M abscessus and were deemed incident cases.59 These patients were significantly less likely to have used azithromycin before their NTM diagnosis, and patients with the longest azithromycin use were least likely to have PNTM. For now, however, patients considered for long-term macrolide monotherapy (eg, those with CF) should be screened to exclude PNTM before starting therapy.

Summary

PNTM prevalence is increasing, and given still partially understood inherited and acquired host factors, further increases are likely. Although the environment is probably the source of most PNTM, the possibility of person-to-person spread must also be considered in highly susceptible populations. However infection occurs, host factors appear critical in determining progression to PNTM, and NTM virulence factors may be less critical. Perturbations, in particular local or systemic host defense mechanisms, may account for different disease phenotypes. This more nuanced view of infection, transmission, and susceptibility may suggest new approaches to screening, prevention, establishing the prognosis for, and treatment of PNTM.

Microbiologic techniques are advancing, and molecular methods for NTM diagnosis are becoming more practical. However, even in highly susceptible populations like patients with CF, it is important to be circumspect in interpreting a single positive culture for NTM. Strategies for AST of clinically important NTM species are being informed by evidence suggesting more relevant parameters for defining their susceptibility to critical antibiotics.

Although therapy remains challenging for many types of NTM, therapeutic gains are possible by intelligently applying existing treatment regimens, even as new strategies for drug selection and adjunctive treatments evolve. Studies, although preliminary, raise the possibility that modified dosing regimens using currently available drugs might result in improved clinical outcomes of PNTM treatment. Because treatment is guided by species type, speciation of NTM isolates and subspeciation of M abscessus are essential. Evidence continues to emerge supporting the appropriateness of expert guidelines underscoring the need for closer adherence to guidelines. Finally, as our ability improves in identifying individuals at the highest risk for PNTM, the possibility of preventive regimens for PNTM may become a reality.

Acknowledgments

Conflict of interest: None declared.

ABBREVIATIONS

- AFB

acid-fast bacilli

- AST

antimicrobial susceptibility testing

- CF

cystic fibrosis

- Cmax

peak serum concentration

- DHEA

dehydroepiandrosterone

- DNTM

disseminated nontuberculous mycobacteria

- Maa

Mycobacterium abscessus subspecies abscessus

- MAC

Mycobacterium avium complex

- Mam

Mycobacterium abscessus subspecies massiliense

- MIC

minimum inhibitory concentration

- MTBC

mycobacterium TB complex

- NB

nodular bronchiectasis

- NTM

nontuberculous mycobacteria

- PCD

primary ciliary dysfunction

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- PMAC

pulmonary Mycobacterium avium complex

- PNTM

pulmonary nontuberculous mycobacteria

- TNF-α

tumor necrosis factor-α

Footnotes

Drs McShane and Glassroth contributed equally to this manuscript.

Reproduction of this article is prohibited without written permission from the American College of Chest Physicians. See online for more details.

References

- 1.Glassroth J. Pulmonary disease due to nontuberculous mycobacteria. Chest. 2008;133(1):243-251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pitchenik AE. PPD-tuberculin and PPD-Battey dual skin testing of hospital employees and medical students. South Med J. 1978;71(8):917-918, 922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Griffith DE, Aksamit T, Brown-Elliott BA, et al. ; ATS Mycobacterial Diseases Subcommittee; American Thoracic Society; Infectious Disease Society of America. An official ATS/IDSA statement: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of nontuberculous mycobacterial diseases [published correction appears in Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175(7):744-745]. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175(4):367-416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prevots DR, Shaw PA, Strickland D, et al. Nontuberculous mycobacterial lung disease prevalence at four integrated health care delivery systems. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182(7):970-976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Billinger ME, Olivier KN, Viboud C, et al. Nontuberculous mycobacteria-associated lung disease in hospitalized persons, United States, 1998-2005. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15(10):1562-1569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adjemian J, Olivier KN, Seitz AE, Holland SM, Prevots DR. Prevalence of nontuberculous mycobacterial lung disease in US Medicare beneficiaries. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185(8):881-886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marras TK, Mendelson D, Marchand-Austin A, May K, Jamieson FB. Pulmonary nontuberculous mycobacterial disease, Ontario, Canada, 1998-2010. Emerg Infect Dis. 2013;19(11):1889-1891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Levy I, Grisaru-Soen G, Lerner-Geva L, et al. Multicenter cross-sectional study of nontuberculous mycobacterial infections among cystic fibrosis patients, Israel. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14(3):378-384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Andréjak C, Thomsen VO, Johansen IS, et al. Nontuberculous pulmonary mycobacteriosis in Denmark: incidence and prognostic factors. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181(5):514-521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adjemian J, Olivier KN, Prevots DR. Nontuberculous mycobacteria among patients with cystic fibrosis in the United States: screening practices and environmental risk. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;190(5):581-586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Adjemian J, Olivier KN, Seitz AE, Falkinham JO, III, Holland SM, Prevots DR. Spatial clusters of nontuberculous mycobacterial lung disease in the United States. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186(6):553-558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Falkinham JO., III Nontuberculous mycobacteria from household plumbing of patients with nontuberculous mycobacteria disease. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17(3):419-424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McGarvey J, Bermudez LE. Pathogenesis of nontuberculous mycobacteria infections. Clin Chest Med. 2002;23(3):569-583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dorman SE, Holland SM. Interferon-gamma and interleukin-12 pathway defects and human disease. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2000;11(4):321-333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sexton P, Harrison AC. Susceptibility to nontuberculous mycobacterial lung disease. Eur Respir J. 2008;31(6):1322-1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bryant JM, Grogono DM, Greaves D, et al. Whole-genome sequencing to identify transmission of Mycobacterium abscessus between patients with cystic fibrosis: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2013;381(9877):1551-1560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aitken ML, Limaye A, Pottinger P, et al. Respiratory outbreak of Mycobacterium abscessus subspecies massiliense in a lung transplant and cystic fibrosis center. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185(2):231-232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tettelin H, Davidson RM, Agrawal S, et al. High-level relatedness among Mycobacterium abscessus subsp. massiliense strains from widely separated outbreaks. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20(3):364-371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dirac MA, Horan KL, Doody DR, et al. Environment or host? A case-control study of risk factors for Mycobacterium avium complex lung disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186(7):684-691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim RD, Greenberg DE, Ehrmantraut ME, et al. Pulmonary nontuberculous mycobacterial disease: prospective study of a distinct preexisting syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178(10):1066-1074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Colombo RE, Hill SC, Claypool RJ, Holland SM, Olivier KN. Familial clustering of pulmonary nontuberculous mycobacterial disease. Chest. 2010;137(3):629-634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.O’Connell ML, Birkenkamp KE, Kleiner DE, Folio LR, Holland SM, Olivier KN. Lung manifestations in an autopsy-based series of pulmonary or disseminated nontuberculous mycobacterial disease. Chest. 2012;141(4):1203-1209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bartley J. Vitamin D: emerging roles in infection and immunity. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2010;8(12):1359-1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jeon K, Kim SY, Jeong BH, Chang B, Shin SJ, Koh WJ. Severe vitamin D deficiency is associated with non-tuberculous mycobacterial lung disease: a case-control study. Respirology. 2013;18(6):983-988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Angerami M, Suarez G, Pascutti MF, Salomon H, Bottasso O, Quiroga MF. Modulation of the phenotype and function of Mycobacterium tuberculosis-stimulated dendritic cells by adrenal steroids. Int Immunol. 2013;25(7):405-411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Suzuki T, Suzuki N, Daynes RA, Engleman EG. Dehydroepiandrosterone enhances IL2 production and cytotoxic effector function of human T cells. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1991;61(2):202-211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Danley J, Kwait R, Peterson DD, et al. Normal estrogen, but low dehydroepiandrosterone levels, in women with pulmonary Mycobacterium avium complex. A preliminary study. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2014;11(6):908-914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fowler CJ, Olivier KN, Leung JM, et al. Abnormal nasal nitric oxide production, ciliary beat frequency, and Toll-like receptor response in pulmonary nontuberculous mycobacterial disease epithelium. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187(12):1374-1381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Winthrop KL, Chang E, Yamashita S, Iademarco MF, LoBue PA. Nontuberculous mycobacteria infections and anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha therapy. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15(10):1556-1561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gommans EP, Even P, Linssen CF, et al. Risk factors for mortality in patients with pulmonary infections with non-tuberculous mycobacteria: a retrospective cohort study. Respir Med. 2015;109(1):137-145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rindi L, Garzelli C. Genetic diversity and phylogeny of Mycobacterium avium. Infect Genet Evol. 2014;21:375-383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tatano Y, Yasumoto K, Shimizu T, et al. Comparative study for the virulence of Mycobacterium avium isolates from patients with nodular-bronchiectasis- and cavitary-type diseases. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2010;29(7):801-806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ito Y, Hirai T, Maekawa K, et al. Predictors of 5-year mortality in pulmonary Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare complex disease. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2012;16(3):408-414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Embil J, Warren P, Yakrus M, et al. Pulmonary illness associated with exposure to Mycobacterium-avium complex in hot tub water. Hypersensitivity pneumonitis or infection? Chest. 1997;111(3):813-816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Khoor A, Leslie KO, Tazelaar HD, Helmers RA, Colby TV. Diffuse pulmonary disease caused by nontuberculous mycobacteria in immunocompetent people (hot tub lung). Am J Clin Pathol. 2001;115(5):755-762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gupta A, Rosenman KD. Hypersensitivity pneumonitis due to metal working fluids: sporadic or under reported? Am J Ind Med. 2006;49(6):423-433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kotilainen H, Valtonen V, Tukiainen P, Poussa T, Eskola J, Järvinen A. Clinical symptoms and survival in non-smoking and smoking HIV-negative patients with non-tuberculous mycobacterial isolation. Scand J Infect Dis. 2011;43(3):188-196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Varadi RG, Marras TK. Pulmonary Mycobacterium xenopi infection in non-HIV-infected patients: a systematic review. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2009;13(10):1210-1218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hayashi M, Takayanagi N, Kanauchi T, Miyahara Y, Yanagisawa T, Sugita Y. Prognostic factors of 634 HIV-negative patients with Mycobacterium avium complex lung disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185(5):575-583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Griffith DE, Philley JV, Brown-Elliott BA, et al. The significance of Mycobacterium abscessus subspecies abscessus isolation during Mycobacterium avium complex lung disease therapy. Chest. 2015;147(5):1369-1375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Martiniano SL, Sontag MK, Daley CL, Nick JA, Sagel SD. Clinical significance of a first positive nontuberculous mycobacteria culture in cystic fibrosis. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2014;11(1):36-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Griffith DE, Brown-Elliott BA, Benwill JL, Wallace RJ., Jr Mycobacterium abscessus. “Pleased to meet you, hope you guess my name...”. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2015;12(3):436-439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nessar R, Cambau E, Reyrat JM, Murray A, Gicquel B. Mycobacterium abscessus: a new antibiotic nightmare. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012;67(4):810-818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Choi GE, Shin SJ, Won CJ, et al. Macrolide treatment for Mycobacterium abscessus and Mycobacterium massiliense infection and inducible resistance. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186(9):917-925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tran AC, Halse TA, Escuyer VE, Musser KA. Detection of Mycobacterium avium complex DNA directly in clinical respiratory specimens: opportunities for improved turn-around time and cost savings. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2014;79(1):43-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kobashi Y, Abe M, Mouri K, Obase Y, Kato S, Oka M. Relationship between clinical efficacy for pulmonary MAC and drug-sensitivity test for isolated MAC in a recent 6-year period. J Infect Chemother. 2012;18(4):436-443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brown-Elliott BA, Iakhiaeva E, Griffith DE, et al. In vitro activity of amikacin against isolates of Mycobacterium avium complex with proposed MIC breakpoints and finding of a 16S rRNA gene mutation in treated isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 2013;51(10):3389-3394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Winthrop KL, McNelley E, Kendall B, et al. Pulmonary nontuberculous mycobacterial disease prevalence and clinical features: an emerging public health disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182(7):977-982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Adjemian J, Prevots DR, Gallagher J, Heap K, Gupta R, Griffith D. Lack of adherence to evidence-based treatment guidelines for nontuberculous mycobacterial lung disease. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2014;11(1):9-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Griffith DE, Brown BA, Murphy DT, Girard WM, Couch L, Wallace RJ., Jr Initial (6-month) results of three-times-weekly azithromycin in treatment regimens for Mycobacterium avium complex lung disease in human immunodeficiency virus-negative patients. J Infect Dis. 1998;178(1):121-126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Griffith DE, Brown BA, Cegielski P, Murphy DT, Wallace RJ., Jr Early results (at 6 months) with intermittent clarithromycin-including regimens for lung disease due to Mycobacterium avium complex. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30(2):288-292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jeong BH, Jeon K, Park HY, et al. Intermittent antibiotic therapy for nodular bronchiectatic Mycobacterium avium complex lung disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;191(1):96-103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wallace RJ, Jr, Brown-Elliott BA, McNulty S, et al. Macrolide/azalide therapy for nodular/bronchiectatic Mycobacterium avium complex lung disease. Chest. 2014;146(2):276-282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Koh WJ, Jeon K, Lee NY, et al. Clinical significance of differentiation of Mycobacterium massiliense from Mycobacterium abscessus. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183(3):405-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kim HS, Lee KS, Koh WJ, et al. Serial CT findings of Mycobacterium massiliense pulmonary disease compared with Mycobacterium abscessus disease after treatment with antibiotic therapy. Radiology. 2012;263(1):260-270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.van Ingen J, Egelund EF, Levin A, et al. The pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of pulmonary Mycobacterium avium complex disease treatment. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186(6):559-565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Olivier KN, Shaw PA, Glaser TS, et al. Inhaled amikacin for treatment of refractory pulmonary nontuberculous mycobacterial disease. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2014;11(1):30-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Philley JV, Wallace RJ, Jr, Benwill JL, et al. Preliminary results of bedaquiline as salvage therapy for patients with nontuberculous mycobacterial lung disease. Chest. 2015;148(2):499-506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Binder AM, Adjemian J, Olivier KN, Prevots DR. Epidemiology of nontuberculous mycobacterial infections and associated chronic macrolide use among persons with cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188(7):807-812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]