Abstract

Telomere DNA-binding proteins protect the ends of chromosomes in eukaryotes. A subset of these proteins are constructed with one or more OB folds and bind with G+T-rich single-stranded DNA found at the extreme termini. The resulting DNA-OB protein complex interacts with other telomere components to coordinate critical telomere functions of DNA protection and DNA synthesis. While the first crystal and NMR structures readily explained protection of telomere ends, the picture of how single-stranded DNA becomes available to serve as primer and template for synthesis of new telomere DNA is only recently coming into focus. New structures of telomere OB fold proteins alongside insights from genetic and biochemical experiments have made significant contributions towards understanding how protein-binding OB proteins collaborate with DNA-binding OB proteins to recruit telomerase and DNA polymerase for telomere homeostasis. This review surveys telomere OB protein structures alongside highly comparable structures derived from replication protein A (RPA) components, with the goal of providing a molecular context for understanding telomere OB protein evolution and mechanism of action in protection and synthesis of telomere DNA.

Keywords: Telomere structural biology, single-stranded DNA-binding proteins, OB fold, x-ray crystallography, NMR, intrinsically disordered protein regions, molecular recognition, allostery

Introduction

Organization of the genome as linear DNA chromosomes capped by telomeres is a defining feature of Eukarya. Linear chromosomes present challenges with respect to stability and replication, and special handling procedures are required to prevent degradation, end-to-end fusion, and attrition with each cell division. Telomere specific proteins stabilize linear genomes through two principal functions: DNA protection and DNA synthesis (Verdun and Karlseder, 2007; de Lange, 2009). For DNA protection, telomere proteins bind with telomere DNA and ensure that natural chromosome ends are not recognized as DNA breaks. For DNA synthesis, telomere proteins recruit two polymerase enzymes: telomerase and DNA polymerase α/primase. Telomerase adds short tandem repeats of a G+T-rich sequence to the 3′-terminus using instructions encoded in a constitutive RNA template. DNA polymerase α/primase initiates and continues synthesis of the C+A-rich strand using the G+T-rich strand as a template. In all organisms investigated, the 3′-terminal G+T-rich strand ends with a portion that is single stranded, a structural feature that is consistent with biochemical requirements of telomerase, but which imparts risks and dangers since this form of DNA is more reactive chemically, is easily hydrolyzed by nucleases, looks like damaged DNA, and promotes recombination. OB fold proteins bind with the single-stranded G+T-rich strand and thus protect this highly sensitive DNA. The DNA-protective role that OB fold proteins play has been well appreciated. Recent results point also to a role for OB fold proteins in DNA synthesis by coordinating interactions among telomere components, including telomerase and DNA polymerase. The structures of these telomere OB proteins are the subject of this review.

OB fold proteins are widely distributed among all domains of life and participate in several aspects of single-stranded nucleic acid metabolism including DNA replication, DNA repair, protein translation, as well as telomere protection. Several excellent reviews examine the evolution and function of OB fold proteins (Theobald et al., 2003b; Agrawal and Kishan, 2003; Arcus, 2002; Flynn and Zou, 2010). The aim here is to survey DNA-binding and protein-binding OB proteins found at telomeres with a particular emphasis on three-dimensional molecular structure. This work is motivated by newly reported structures of telomere associated OB proteins and the realization that telomere OB protein complexes are more widely conserved than previously thought. The hope is that patterns (and exceptions) identified through structural comparison will generate expectations and testable ideas for newly discovered telomere OB proteins.

Overview of telomere and RPA OB proteins for which structures are available

The first structures of OB folds derived from telomere proteins and replication protein A (RPA) subunits focused on those proteins and domains with high affinity DNA-binding activity. RPA was isolated as an essential multi-subunit complex required for cell-free SV40 DNA replication reactions (Fairman and Stillman, 1988; Wold and Kelly, 1988; Brill and Stillman, 1991). Replication protein A is conserved across Eukarya, and is considered the central single-stranded DNA-binding component of DNA replication forks and DNA repair centers (Wold, 1997; Fanning et al., 2006). Constructed with large, medium, and small subunits, replication protein A closely resembles subcomplexes found at telomeres. Telomere DNA synthesis shares biochemical requirements with DNA replication, and the telomere OB proteins and replication protein A were likely preceded by a common ancestor that could protect single-stranded DNA and coordinate DNA exchange with polymerases and DNA repair enzymes. The telomere OB protein family includes protein-binding members, and structures of protein-interacting telomere OB proteins demonstrate structural homology with protein-interacting RPA subunits. The idea emerging is that replication protein A-like complexes were duplicated and rapidly acquired several specialized functions that all fall in the general category of genome guardians (Flynn and Zou, 2010).

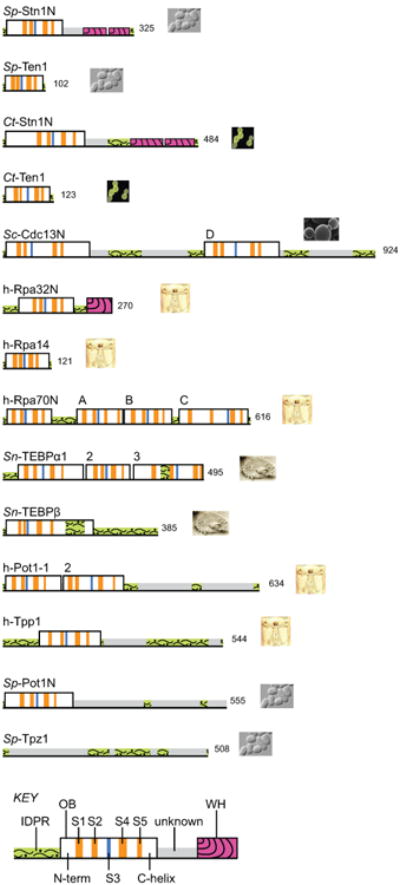

Figure 1 provides an overview of telomere and RPA OB-containing proteins for which three-dimensional structures are available. Stn1 and Ten1 were first characterized as proteins which interact with Cdc13 to regulate telomere length in budding yeast (Grandin et al., 1997; Grandin et al., 2001). The Cdc13–Stn1–Ten1 (CST) complex appears to be conserved across eukaryotes with homologs of Stn1 and Ten1 identified in fission yeast (Martin et al., 2007), plants (Song et al., 2008), and vertebrates (Miyake et al., 2009; Wan et al., 2009), and an analog of Cdc13 (called Ctc1) identified in plants and mammals (Surovtseva et al., 2009; Miyake et al., 2009) [reviewed in (Wellinger, 2009; Price et al., 2010)]. Mammalian Stn1 and Ctc1 had previously been characterized as accessory factors that complex with and stimulate polymerase α/primase (Goulian et al., 1990; Goulian and Heard, 1990; Casteel et al., 2009). The analogous Stn1 and Cdc13 proteins in yeast, similarly interact with polymerase α/primase (Qi and Zakian, 2000; Hsu et al., 2004), and also with telomerase (Qi and Zakian, 2000; Pennock et al., 2001).

Figure 1.

Overview of OB folds in telomere OB proteins and RPA. See on-line version for color; print version lacks color. Protein regions for which three-dimensional structures have been determined by x-ray crystallography or NMR are outlined as tall boxes; regions not yet structurally characterized are low profile. Numbers at the C-terminus indicate the number of residues in that protein. OB units are labeled to indicate the source organism, the protein name, and a unique identifier if the protein contains more than one OB unit or folded domain (see also Table 1 for names of OB units). Icons provide visual cues for the protein source organisms, which are listed here in order of appearance: Schizosaccharomyces pombe, Candida tropicalis, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Homo sapiens, and Sterkiella nova. Within each OB fold, the conserved structural elements are highlighted with color as follows: S3, blue; S1, S2, S4, and S5, orange (see Fig 2 for further explanation of these elements). Winged helix-turn-helix (WH) motifs found at the C-terminus of Rpa32 and Stn1 are colored magenta with curved stripes. Sp-Ten1 represents the smallest OB unit with very short loops connecting each of the conserved S1 – S5 elements. Segments with a high probability of adopting intrinsically disordered structure are colored green with a wavy pattern. Note that in some cases an intrinsically disordered protein region (IDPR) adopts a fixed structure upon association with a binding partner, as is the case for the IDPR contained within the Sn-TEBPβ OB unit (tall box). Structurally uncharacterized regions within Sc-Cdc13, Sp-Pot1, Sp-Tpz1 and h-Pot1 with low IDPR scores (grey and no pattern) likely contain additional OB units as previously predicted (Theobald and Wuttke, 2004; Miyoshi et al., 2008). Amino acid sequence profiling to score for intrinsically disordered regions was accomplished with the program DISPro (Hecker et al., 2008) as implemented with the SCRATCH protein structure prediction server (Cheng et al., 2005).

In this review, each OB protein unit will be labelled with a short name indicating source organism, name of the complete protein, and either a letter or a number differentiating one OB unit from others in those proteins that have multiple parts (see Table 1 for a complete list of OB unit names used in this review). Thus, Sp-Stn1N is the N-terminal OB unit derived from Schizosaccharomyces pombe Stn1, and Sc-Cdc13D is the DNA-binding OB unit derived from Saccharomyces cerevisiae Cdc13 protein. The N-terminal domain of Stn1 is an OB fold (box with vertical stripes in Fig 1) and the structures of Sp-Stn1N and Ct-Stn1N have been determined in complex with species-specific homologs of Ten1 from Schizosachharomyces pombe and Candida tropicalis (Sun et al., 2009). The C-terminal domain of Stn1 consists of two winged helix-turn-helix (WH) motifs as deduced from crystal structures of the corresponding domain from Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Sun et al., 2009; Gelinas et al., 2009).

Table 1. Structurally characterized telomere protein and RPA-derived OB units.

| name | description (residue range; chain id pdb id*) |

|---|---|

| Sp-Stn1N | N-terminal OB unit found in Stn1, a ubiquitous telomere protein that closely resembles the medium-sized subunit of replication protein A, Rpa32. Stn1N forms a stable heterodimer with Ten1. Source: Schizosaccharomyces pombe. (16-154; chain A 3kf6) |

| Ct-Stn1N | ibid. Source: Candida tropicalis. (19-214; chain A 3kf8) |

| h-Rpa32N | N-terminal OB unit found in Rpa32, the DNA-replication and repair factor most closely related with telomere protein Stn1. Rpa32N forms a stable heterodimer with Rpa14 and a stable heterotrimer with Rpa14 and Rpa70C. Source: human. (41-176; chain A 2pi2, 1quq, also chain B 1l1o) |

| Sp-Ten1 | The single OB unit comprising Ten1, a ubiquitous telomere protein closely resembling the small subunit of replication protein A, Rpa14. Ten1 forms a stable heterodimer with Stn1. Source: Schizosaccharomyces pombe. (1-102; chain B 3kf6, also chain A 3k0x) |

| Ct-Ten1 | ibid. Source: Candida tropicalis. (2-121; chain B; 3kf8) |

| h-Rpa14 | The single OB unit comprising Rpa14, the DNA-replication and repair factor most closely related with telomere protein Ten1. Rpa14 forms a stable heterodimer with Rpa32 and a heterotrimer with Rpa32 and Rpa70C. Source: human. (2-118; chain E 2pi2, chain A 1l1o, chain B 1quq) |

| Sc-Cdc13N | OB unit from the cell division control protein Cdc13, a telomere protein with multiple OB units. Cdc13 appears related, by analogy or paralogy, to the large subunit of replication protein A (Rpa70) and to Ctc1. Cdc13N is the N-terminal OB unit and forms a stable homodimer which binds the catalytic unit of the DNA polymerase α/primase complex. Dimerization is additionally linked to modest binding activity for long single-stranded DNA fragments. Source: Saccharomyces cerevisiae. (13-224; chain A 3oiq; 3oip; 3nws; 3nwt) |

| Sc-Cdc13D | ibid. Cdc13D binds single-stranded DNA, with ultra-high affinity to the sequence d(GTGTGGGTGTG). Source: Schizosaccharomyces pombe. (500-686; chain A 1s40; 1kxl) |

| h-Rpa70N | OB unit from Rpa70, the large subunit of replication protein A. Rpa70N is the N-terminal OB unit and binds with the tumor suppressor and DNA-damage checkpoint protein p53. Source: human. (1-128; chain A 2b3g) |

| h-Rpa70C | ibid. Rpa70C is the C-terminal OB unit which forms a heterotrimer with Rpa32 and Rpa14. Source: human. (439-616; chain C 1l1o) |

| h-Rpa70A | ibid. Rpa70A and Rpa70B bind single-stranded DNA. Source: human. (183-298; chain A 1jmc, 1fgu) |

| h-Rpa70B | ibid. (299-420; chain A 1jmc, 1fgu) |

| h-Pot1-1 | OB unit from protection of telomere protein 1, a ubiquitous telomere protein with dual roles in protection and synthesis of telomere DNA. Pot1-1 and Pot1-2 form a stable single-stranded DNA-binding domain that is highly comparable in structural form with the DNA-binding domain of Sn-TEBPα and that exhibits high affinity and specificity for the sequence d(TTAGGGTTAG). Source: human. (6-145; chain A 1xjv, 3kjo, 3kjp) |

| h-Pot1-2 | ibid (149-299; chain A 1xjv, 3kjo, 3kjp) |

| Sp-Pot1N | N-terminal DNA-binding OB unit in Pot1 from fission yeast. The complete DNA-binding domain probably includes a second OB unit, the structure of which is unavailable. The structure of Sp-Pot1N complexed with d (GGTTAC) is highly comparable with structures of h-Pot1-1 and Sn-TEBPα1 seen as portions of DNA-complexed proteins. Source: Schizosaccharomyces pombe. (5-174; chain A 1qzh, 1qzg) |

| h-Tpp1 | A Pot1-interacting protein containing at least one OB unit that is highly comparable to Sn-TEBPβ in terms of structure and function. Tpp1 enhances DNA-binding affinity, DNA versus RNA discrimination, and telomerase processivity activity measured for Pot1. Source: human. (96-241; chain A 2i46) |

| Sn-TEBPα1 | OB unit from the telomere end-binding protein alpha subunit. TEBPα1 and α2 form the N-terminal DNA-binding domain which binds d(TTTTGGGG) with modest affinity and sequence specificity. The complete TEBPα protein forms a complex with TEBPβ that is stable only in the presence of DNA. Source: Sterkiella nova. (36-204; chain A 2i0q, 1otc, 1jb7, 1kix, 1k8g, 1ph1, 1ph2, and several others) |

| Sn-TEBPα2 | ibid. (205-313; chain A 2i0q, 1otc, 1jb7, 1kix, 1k8g, 1ph1, 1ph2, and several others) |

| Sn-αN | The N-terminal DNA-binding domain of TEBPα, synonymous with TEBPα1 + α2. Source: Sterkiella nova. (36-313; chain A 2i0q, 1otc, 1jb7, 2kix, 1k8g, 1ph1, 1ph2, and several others) |

| Sn-TEBPα3 | The C-terminal OB unit from the telomere end-binding protein alpha subunit which interacts with TEBPβ, the second telomere end-binding subunit. TEBPα–TEBPβ association is DNA-dependent. Source: Sterkiella nova. (325-495; chain A 2i0q, 1otc, 1jb7, 1ph1, etc.) |

| Sn-TEBPβ | The second telomere end-binding protein subunit from Sterkiella nova, which appears related by paralogy with human Tpp1 and with the fission yeast protein Tpz1. TEBPβ contains one OB unit, an internal IDPR insertion (residues 165-200), and a C-terminal IDPR tail (residues 234-385). TEBPβ associates with the TEBPα-DNA complex, extending the DNA-binding interface to include d(TTTTGGGGTTTTGGGG), and enhancing DNA affinity. Source: Sterkiella nova. (9-223; chain B 2i0q, 1otc, 1jb7, 1ph1, etc.) |

| Sn-αNβΔ | Chimera protein constructed with two DNA-binding OB units of TEBPα fused to the OB unit of TEBPβ. αNβΔ binds d(TTTTGGGGTTTTGGGG), and a crystal structure shows DNA interactions not seen in previous structures. Source: Sterkiella nova. (35-316 of α, 1-155+201-231 of β, [156-200, including IDPR of β deleted]) |

Certain crystal space groups contain multiple copies of the same protein. In these cases only the first instance of a particular chain is identified. For OB units that have been structurally determined multiple times multiple pdb ids are listed, the first of which corresponds with structures used in analyses presented in this review.

The structural domains of Stn1 are highly comparable with those found in the medium-sized RPA subunit, Rpa32 (Sun et al., 2009). Stn1 and Rpa32 each contain an N-terminal OB unit and a C-terminal WH motif. Tandem duplication of the WH unit appears to be a telomere-specific innovation since Rpa32 has one WH and Stn1 has two (Gelinas et al., 2009). The structure of the OB fold from human Rpa32, h-Rpa32N, has been determined as part of a heterodimer with the RPA small subunit, Rpa14 (Bochkarev et al., 1999), and as part of a heterotrimer with Rpa14 and the C-terminal OB unit derived from the RPA large subunit, Rpa70 (Bochkareva et al., 2002). The structure of a winged helix-turn-helix domain of human Rpa32 has been determined by NMR, in an unliganded form and as complexes with peptides derived from DNA-repair enzymes (Mer et al., 2000). These and other structures of RPA-derived subcomplexes illustrate the modular nature of OB units in forming OB-DNA and OB-protein complexes, a theme that also applies to telomere OB proteins.

In budding yeast, the Stn1–Ten1 subcomplex recruits Cdc13, a larger telomere protein with multiple OB units. Two OB units contained within Cdc13 have been structurally characterized (Mitton-Fry et al., 2002; Mitchell et al., 2010; Sun et al., 2011), and two others were predicted by sequence profile analysis (Theobald and Wuttke, 2004). A centrally located OB unit in Cdc13, Sc-Cdc13D, binds telomere single-stranded DNA with high affinity, and the solution structure of a Sc-Cdc13D-DNA complex has been determined by NMR (Mitton-Fry et al., 2004). Structures of the N-terminal OB unit of Cdc13, Sc-Cdc13N, are now available in an unliganded state (Mitchell et al., 2010; Sun et al., 2011) and as a complex with a peptide derived from Pol1 (Sun et al., 2011), the catalytic component of the DNA polymerase α/primase complex essential for initiation of semi-conservative DNA synthesis.

The large subunit of replication protein A, Rpa70, contains four OB units, each of which has been structurally characterized. A structure of the N-terminal OB unit, Rpa70N, was determined in complex with a peptide derived from the tumor suppressor and DNA-damage checkpoint protein p53 (Bochkareva et al., 2005). Structures of the tandem Rpa70A+Rpa70B DNA-binding OB units have been determined by x-ray crystallography, as an unliganded protein (Bochkareva et al., 2001) and in complex with single-stranded DNA (Bochkarev et al., 1997). A structure of the C-terminal OB unit, Rpa70C, was obtained as part of a higher-order assembly involving Rpa32N and Rpa14 (Bochkareva et al., 2002).

The Cdc13(or Ctc1)–Stn1–Ten1 complex works alongside a second telomere specific complex centered on Pot1 and its interacting partner Tpp1. OB units within the Pot1–Tpp1 subcomplex are structurally similar to OB components within the Sn-TEBPα–TEBPβ heterodimer from Sterkiella nova (formerly Oxytricha nova), consistent with the idea that this subcomplex has been conserved across evolution (Baumann and Cech, 2001; Xin et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2007). The Pot1–Tpp1 complex has a ying/yang relationship with telomerase, acting to sequester and protect single-stranded DNA so that access to telomerase is limited (Liu et al., 2004; Ye et al., 2004; Lei et al., 2005), and also serving to recruit telomerase and enhance telomerase processivity (Xin et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2007; Zaug et al., 2010; Latrick and Cech, 2010). Presumably these two diametrically opposed activities are regulated to meet requirements at different stages of the cell cycle.

Principle DNA-binding activity for Pot1–Tpp1 and TEBPα–TEBPβ resides with two N-terminal OB units (Pot1-1 and Pot1-2 in Pot1; TEBPα1 and TEBPα2 in Sn-TEBPα), and structures for these domains in complex with species-specific single-stranded telomere DNA are available (Lei et al., 2004; Classen et al., 2001; Peersen et al., 2002). Additional OB units contained within Pot1 and Sn-TEBPα mediate interaction with Tpp1 and Sn-TEBPβ, respectively. The structure of a Sn-TEBPα–TEBPβ heterodimer complexed with single-stranded DNA showed details for DNA interaction and protein-protein association (Horvath et al., 1998).

A crystal structure of the OB unit derived from Tpp1 showed structural features shared with Sn-TEBPβ but not seen in other OB proteins (Wang et al., 2007). Multiple regions in both Tpp1 and Sn-TEBPβ score high probability for intrinsically disordered protein regions (IDPR)s (see Fig 1), providing additional support for the idea that Tpp1 and Sn-TEBPβ are descendants of a common ancestral protein. Outside of the OB unit, structural information for Tpp1 is sparse and a detailed view of the Pot1–Tpp1 interface is unavailable. The C-terminal IDPR of Sn-TEBPβ comprises residues 231-385 which are similarly recalcitrant to structure determination (Buczek and Horvath, 2006a). As observed in crystal structures of a Sn-TEBPαβ–DNA complex (Horvath et al., 1998; Buczek and Horvath, 2006a) the TEBPα–TEBPβ interface is constructed by OB-OB contacts between the OB unit of Sn-TEBPβ and the middle (Sn-TEBPα2) and C-terminal (Sn-TEBPα3) OB unit of Sn-TEBPα. The OB-OB portion of the TEBPα–TEBPβ interface is augmented by 46 residues in Sn-TEBPβ (residues 165β-200β) which adopt relatively extended peptide structure that partially wraps around Sn-TEBPα3. 2D-NMR spectra recorded for Sn-TEBPβ and deletion variants of Sn-TEBPβ indicated residues 165β-200β are highly mobile prior to association with Sn-TEBPα and single-stranded DNA, meaning these residues are an IDPR insertion contained within the Sn-TEBPβ OB unit that co-fold upon assembly of the ternary complex, as inferred from inspection of the Sn-TEBPαβ–DNA crystal structure (Horvath et al., 1998).

The Pot1–Tpp1 and Sn-TEBPα–TEBPβ complexes are recapitulated in fission yeast as a Sp-Pot1–Tpz1 complex. The structure of the N-terminal OB unit resident in Sp-Pot1 has been determined in complex with single-stranded DNA (Lei et al., 2003). The DNA-binding Sp-Pot1N OB unit is thought to collaborate with a second, immediately adjacent OB unit (Trujillo et al., 2005; Croy et al., 2006); however, the two-OB Sp-Pot1 DNA-binding domain was difficult to express and a structure for the putative second OB fold is currently unavailable. At the time this review was prepared, a structure for the S. pombe Tpp1 homolog, Tpz1 was also unavailable. Sequence profiling shows C-terminal regions of Sp-Tpz1 score a high probability of adopting intrinsically disordered structure (Fig 1), meaning IDPRs are likely a conserved feature important for some aspect of h-Tpp1/Sn-TEBPβ/Sp-Tpz1 function.

Structural architecture of the OB fold

Structural similarity among OB proteins was first described by Murzin (Murzin, 1993). Elements defining the OB fold comprise five beta strands arranged as two anti-parallel beta sheets that form a partially closed structure reminiscent of a barrel (Fig 2). Previously, OB folds were reliably identified only by structure determination. With advances in sequence profile searches and a now robust collection of OB structures, it is currently possible to pull out OB proteins from genome databases with a fair degree of confidence (Baumann and Cech, 2001; Theobald and Wuttke, 2004; Martin et al., 2007; Gao et al., 2007; Miyake et al., 2009). Sequence matching is challenging because the core beta strand elements support diverse insertions and embellishments at connecting segments as well as N-terminal and C-terminal extensions. Plasticity in structure likely makes the OB protein especially well suited for divergent evolution and establishment of new functions. For this review we are most interested in three principle OB functions: binding single-stranded DNA, binding extended peptide or helical segments, and binding other OB fold units. Figure 2 illustrates the conserved core OB structure engaged in each of these three activities.

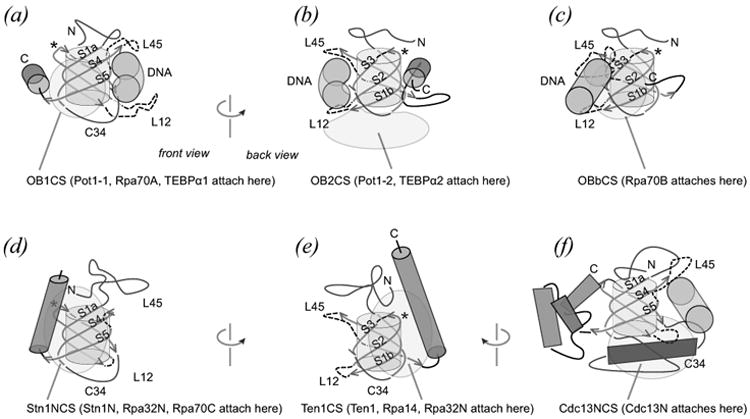

Figure 2.

Architecture of RPA and telomere protein OB folds. See on-line version for color; print version lacks color. Conserved beta strand elements (orange arrows, labeled) wrap around the OB fold core (grey cylinder). Loops (dashed) connect the beta strands in a characteristic topology so that beta strands S1a-S4-S5 form one anti-parallel beta sheet and strands S1b-S2-S3 form a second sheet. From the vantage point chosen here, the N-terminal region (blue, labeled N) and S3-S4 connecting portion (blue, labeled C34) cap the OB beta barrel from “above” and “below”. The view shown in panels (a), (d) and (f) correspond with the “front” of the OB fold, and the view shown in panels (b), (c) and (e) correspond with the “back”. Contact surfaces typically seen in telomere OB protein structures are indicated with transparent pink shapes. (a-c) Examples of single-stranded DNA-binding OB folds show DNA (green cylinder) at the classical oligo-binding surface defined by L45 and L12 from above and below. For DNA-binding OB units, the C-terminal helix (blue, labeled C) lies along the equator of the OB fold (a, b) or is absent (c) as observed for Rpa70A. Each of these DNA-binding OB folds collaborates with a second OB unit that makes intramolecular contact at one of three contact surfaces, labeled OB1CS (a) OB2CS (b) and OBbCS (c). (d-f) Examples of protein-binding OB folds. For these protein-binding OB units, the C-helix aligns in an axial manner and participates in defining two contact surfaces used in OB fold inter-molecular association, labeled Stn1NCS (d) and Ten1CS (e) on the front and back of the structure. (f) A third OB protein association interface is defined by the dimer interface of Cdc13N, which is constructed with symmetry equivalent C34-helices (dark blue). In this (Sc-Cdc13N)2 structure, the classical oligo-binding site is altered so that C34-helices assume the role normally played by L12 in contacting an oligopeptide ligand (green cylinder).

The naming of structural elements and contact surfaces will simplify further analysis and discussion. As labeled in Figure 2, the five beta strands are called S1a, S1b, S2, S3, S4, and S5. Strand S1 forms the outer edge of both beta sheets, with topology S1a-S4-S5 in one beta sheet, and S1b-S2-S3 in the second beta sheet. Connecting loops are L12, L23, and L45, with the name indicating the two connected strands. S3 connects to S4 with either extended peptide or helical structure or a mixture of both, and this structural element is labeled C34 to indicate a different, more elaborate connection compared with the Lij loops. C34 seals the “bottom” of the OB barrel along the otherwise open S1b/S5 seam. In some cases L45 serves a similar role and folds so as to connect the two beta sheets at the “top” of the OB barrel along the S1a/S3 seam. The N-terminal region consistently forms some kind of elaboration that caps the OB barrel. Most OB folds end with a C-terminal helix (C-helix). The C-helix is characteristically embedded between or alongside L23 and the C-terminal portion of C34. In most telomere OB proteins, the C-helix is oriented along the equator of the OB structure or parallel to the barrel's axis of radial symmetry. For some telomere protein and RPA-derived OB units (e.g. Sn-TEBPα3) the C-helix is missing, and in two OB proteins (Sn-TEBPβ and h-Tpp1) the C-helix is removed from its normally observed location and is found instead towards the “back” and “top” of the OB structure interacting with residues of the N-terminal element.

OB fold units generally work in pairs, either covalently tethered in one protein or as individual subunits of a heterodimer. For example, DNA-binding domains of the S. nova telomere protein Sn-TEBPα and its human homolog h-Pot1 each comprise two OB folds. In both of these DNA-binding domains, OB1 fits onto the “front” of OB2 as defined by the S1aS4S5 sheet (Fig 2(a)). For this review, contact surfaces will be named according to the prototypical OB unit that fits into each surface. Accordingly, the OB1-associated contact surface is designated OB1CS. OB2 fits onto the “bottom” of OB1 as defined by the C34 connector and L12, and this OB2-associated contact surface is called OB2CS (Fig 2(b)).

Contact surfaces connecting two OB units may associate in response to binding of DNA, or these may stably associate in both DNA-bound and ligand-free states. The N-terminal DNA-binding domain of Sn-TEBPα, Sn-TEBPαN, serves as an example of the latter category. The crystal structure of Sn-TEBPαN has been determined in unbound and DNA-bound states, and the two OB units (Sn-TEBPα1 and Sn-TEBPα2) make the same interactions with each other in both states, meaning intramolecular OB-OB contacts do not change in response to DNA-binding for this protein (Classen et al., 2001; Peersen et al., 2002).

Different from the situation described for Sn-TEBPα, the principal DNA-binding OB units of Rpa70 (Rpa70A and Rpa70B) respond dramatically to binding of single-stranded DNA (Bochkarev et al., 1997; Bochkareva et al., 2001). In the unliganded state, Rpa70A and Rpa70B are loosely tethered and make very modest contact with each other. In the DNA-bound state, Rpa70 OB units are rotated by 45 ° and make more significant interaction. Rpa70A contacts Rpa70B at OB1CS very similarly to the arrangement seen for DNA-binding OB units in Sn-TEBPα and Pot1, but Rpa70B contacts Rpa70A not at OB2CS but at a different surface, OBbCS, defined by a highly extended L45 and the outer edge of the S1aS2S3 sheet on the “back” of the OB structure (Fig 2 (c)).

The path taken by single-stranded DNA is either straight or bent depending on the particular contact surface connecting two DNA-binding OB units. Each of the structurally characterized single-stranded DNA-binding OB units cradles ssDNA at the classical oligo-binding site defined by L45 and L12 (Fig 2(a-c)). In Rpa70, with front-to-back arrangement of OB1CS and OBbCS, single-stranded DNA continues from the oligo-binding site on Rpa70A to that of Rpa70B in a straight path without changing direction. In the DNA complexes observed for h-Pot1 and Sn-TEBPα, the telomere single-stranded DNA must bend sharply to maintain contact with the oligo-binding sites at two OB units because these are arranged front-to-bottom with use of OB1CS and OB2CS. Bending of single-stranded DNA may be a telomere-specific innovation, as previously noted (Croy and Wuttke, 2006).

These examples show that structural organization of OB units within an OB protein has consequences for DNA structure. Further levels of organization and new contact surfaces are apparent from examination of how telomere proteins associate with each other. Telomere OB proteins often assume asymmetrical quarternary structure through association of unequal protein subunits. For example, the telomere OB proteins from S. nova were isolated from ciliates as a DNA-bound TEBPα–β heterodimer (Gottschling and Zakian, 1986; Price and Cech, 1989). In this case, subunit association is DNA-dependent (Fang and Cech, 1993; Fang et al., 1993; Buczek et al., 2005) and involves OB-OB contacts, OB-oligopeptide contacts, as well as OB-DNA contacts.

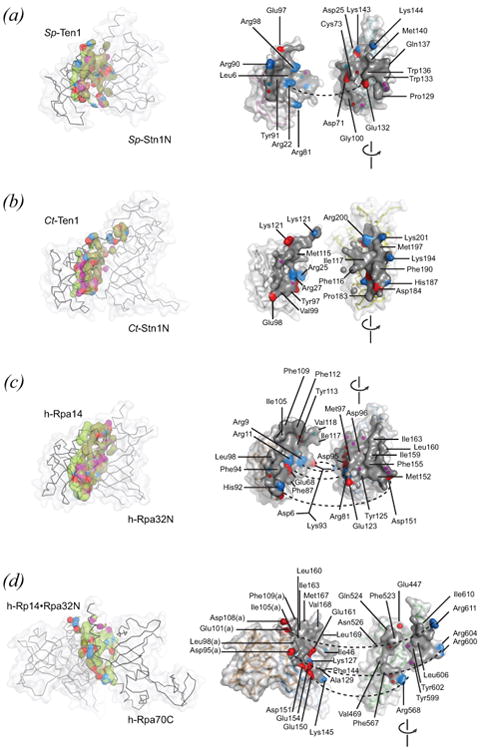

The telomere proteins Stn1 and Ten1 form a stable heterodimer, which binds single-stranded DNA and other telomere components, such as Sc-Cdc13 in budding yeast and Ctc1 in plants and vertebrates, with functional consequences for telomere homeostasis (Pennock et al., 2001; Gao et al., 2007; Martin et al., 2007; Song et al., 2008; Wan et al., 2009; Surovtseva et al., 2009; Miyake et al., 2009) [also reviewed in (Linger and Price, 2009)]. Recently determined structures of the Stn1 N-terminal OB fold (Stn1N) complexed with Ten1 from two yeast species show that the Stn1N–Ten1 interface relies heavily on C-helices contributed from both OB proteins (Sun et al., 2009). The C-helix of Stn1 lies along a surface on Ten1 defined by the S1aS4S4 beta sheet and C-helix of Ten1, (Stn1CS in Fig 2(d)). The C-helix of Ten1 lies along a different surface on Stn1 defined by the opposite S1bS2S3 beta sheet and C-helix, (Ten1CS in Fig 2 (e)). Each of these contact surfaces is highly analogous with those found at the Rpa32–Rpa14 heterodimer interface, with Rpa14 fitting into the Ten1CS on Rpa32N and Rpa32N fitting into the Stn1CS on Rpa14. At the interface of Rpa70C and the Rpa32–Rpa14 subcomplex, Rpa32N provides the Stn1CS which interfaces with Ten1CS provided by Rpa70C.

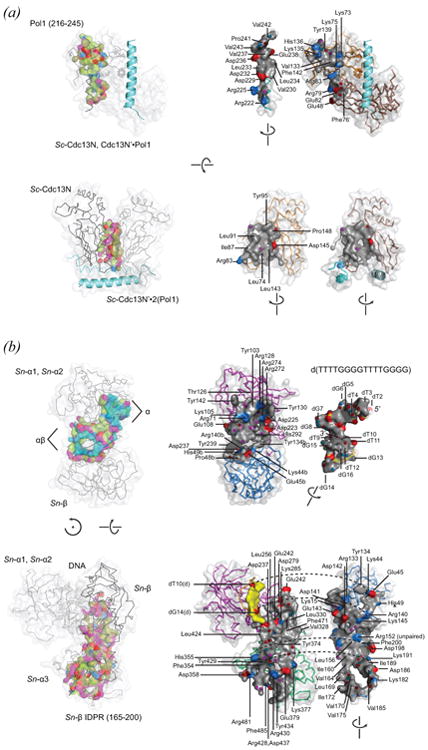

The crystal structures of the N-terminal OB fold from Sc-Cdc13 revealed a dimeric quarternary structure with C2 rotational symmetry (Mitchell et al., 2010; Sun et al., 2011). Symmetrical dimers and tetramers are familiar OB arrangements for single-stranded DNA-binding proteins in Eubacteria and Archaea [reviewed in (Horvath, 2008b)], but unusual for eukaryote OB proteins with a role in DNA metabolism which are generally constructed as asymmetrical hetero-oligomers. The Sc-Cdc13N OB unit contains a highly developed C34 region. A large helix in the N-terminal portion of C34 fits into a groove formed between the C34 helix and S5 of a symmetry related Sc-Cdc13N subunit (Cdc13NCS in Fig 2 (f)). As will be discussed further below, the Sc-Cdc13N dimer interface is functionally important for telomere DNA synthesis (Mitchell et al., 2010; Sun et al., 2011), and Cdc13 dimerization is evolutionarily conserved (Sun et al., 2011).

The examples discussed so far have served to partially introduce structural elements that differentiate telomere OB protein from each other and from replication protein A subunits. The following sections further analyze structural similarities and differences with the aim of identifying innovations that were functionally important for telomeres and also to detangle evolutionary relationships. Structure is especially important for this quest because much (but not all) of the historical record for OB proteins has been scrambled at the amino acid sequence level.

Structural conservation and diversity

Structures of telomere OB proteins have been instrumental in the hunt for homologous telomere OB proteins. The first crystal structure of telomere OB fold proteins from Sterkiella nova provided molecular details explaining DNA binding and recognition and revealed structural homology with replication protein A (RPA), another OB fold protein involved in DNA metabolism (Horvath et al., 1998). The next telomere OB protein to be described structurally was the single-stranded DNA-binding domain derived from Cdc13, the principle single-stranded telomere DNA-binding agent in budding yeast. The NMR structure of Sc-Cdc13D showed that OB folds would be a conserved feature of telomere end protection (Mitton-Fry et al., 2002). The N-terminal OB fold unit in S. nova TEBPα facilitated identification of a homologous telomere DNA-binding OB protein, Pot1, (Baumann and Cech, 2001), and structural similarity for S. pombe Pot1, human Pot1 and Sn-TEBPα derived DNA-binding domains support an evolutionary relation (Lei et al., 2003; Lei et al., 2004).

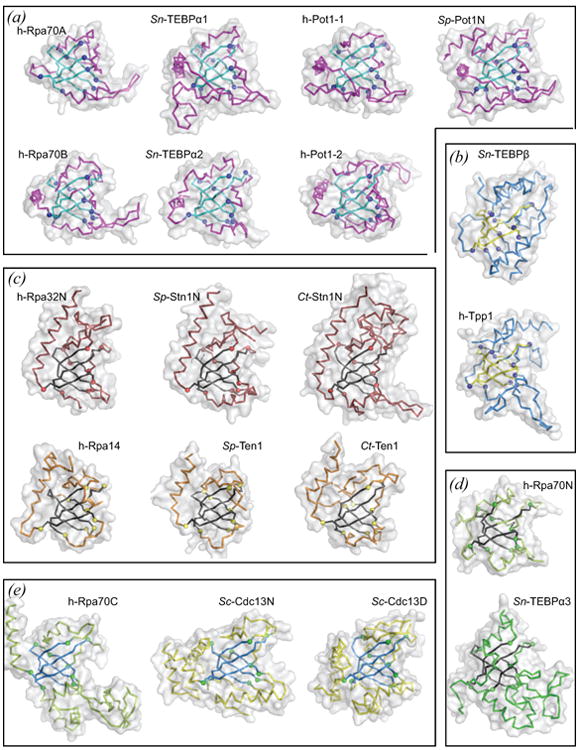

Figure 3 shows three-dimensional models of OB units grouped according to function and structural criteria. Each unit is either derived from a telomere OB protein or from replication protein A. Each example is viewed in the same orientation, with the S1aS4S5 sheet toward the viewer, the C-helix on the left (if present), and loops L12 and L45 on the right. Root mean squared deviations calculated for representative pairwise comparisons ranges from 0.9 to 2.6 Å (mean rmsd = 2.0 Å, n = 36) for 44-49 overlapping Cα positions (Table 2). Aligned in this way, the five conserved beta strands are recognizable in each OB unit (contrasting ribbon color in Fig 3). While OB conserved elements have been preserved nearly intact over millions of years of evolution, slight truncations and insertions in the beta strands are nevertheless apparent. For example, several members, especially those belonging to the DNA-binding group (Fig 3(a)), have one extra residue in S4 that is not found in S4 of the Stn1 group (Fig 3(c)). Also, the N-terminal portion of S1 is shorter by two residues in the Sn-TEBPβ/Tpp1 group (Fig 3(b)). Conserved element S2 terminates with a tight turn configured with an Asp-Gly-Thr/Ser-Gly motif, and deviations from this pattern are evident in newly determined structures of a Candida tropicalis Ct-Stn1N–Ten1 heterodimer (Sun et al., 2009) and structures of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Sc-Cdc13N)2 homodimer (Mitchell et al., 2010; Sun et al., 2011).

Figure 3.

Structures of telomere protein and RPA-derived OB folds. See on-line version for color; print version lacks color. Each OB unit is depicted as an alpha-carbon trace inside a semi-transparent accessible surface (grey) oriented as in Fig 2(a) with the classical oligo-binding surface on the right, N-terminal extension on top and C34 connecting element on bottom. Each OB fold was aligned on the basis of 43-49 equivalent alpha carbon positions contained within the structurally conserved core comprising strands S1 – S5 (contrasting color). Representative pairwise root mean squared deviations are reported in Table 2. Each panel groups OB structures according to shared binding function and shared structural features. (a) The single-stranded DNA-binding group includes two OB units from each of h-Rpa70, Sn-TEBPα, and h-Pot1, and the N-terminal OB unit from Sp-Pot1. In addition to DNA-binding function, six of the seven OB units in this group position the C-helix along the equator of the OB barrel. (b) Structures are shown for Sn-TEBPβ and its human homolog Tpp1, each of which collaborates with its respective DNA-binding partner (Sn-TEBPβ with Sn-TEBPα, h-Tpp1 with h-Pot1) to enhance DNA-binding affinity. Sn-TEBPβ and Tpp1 additionally position the C-helix at the back of the OB unit, interacting with the N-terminal extension. (c) Members of the Rpa32N/Stn1N group each dimerize with a smaller subunit from the Rpa14/Ten1 group, and all members of these two groups feature a C-helix that is positioned axially along the OB barrel. (d) Rpa70N and Sn-TEBPα3 each bind polypeptide ligands and lack a C-helix. (e) The three OB units grouped here feature a highly elaborate C34 element connecting S3 and S4. Note that Sc-Cdc13D could be placed with the group containing Sn-TEBPα1 and h-Pot1-1 on the basis of DNA-binding function; however, recently discovered structural similarity with Sc-Cdc13N and the phylogeny presented in Figure 4 argue for placement together with h-Rpa70C and Sc-Cdc13N. Structures were rendered with PyMOL [PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 0.99, Schrödinger, LLC] using atomic coordinates obtained from the protein data bank (PDB) listed here by PDB identifier: h-Rpa70A and h-Rpa70B, 1jmc (Bochkarev et al., 1997); Sn-TEBPα1, Sn-TEBPα2, Sn-TEBPα3, and Sn-TEBPβ, 2i0q (Buczek and Horvath, 2006a); h-Pot1-1 and h-Pot1-2, 1xjv (Lei et al., 2004); Sp-Pot1N, 1qzh (Lei et al., 2003); h-Tpp1, 2i46 (Wang et al., 2007); h-Rpa32N and h-Rpa14, 2pi2 (Deng et al., 2007); Sp-Stn1N and Sp-Ten1, 3kf6; Ct-Stn1N and Ct-Ten1, 3kf8 (Sun et al., 2009); h-Rpa70N, 2b3g (Bochkareva et al., 2005); h-Rpa70C, 1l1o (Bochkareva et al., 2002); Sc-Cdc13N, 3oiq (Sun et al., 2011); Sc-Cdc13D, 1s40 (Mitton-Fry et al., 2004).

Table 2. Root mean squared deviation for pairwise comparison of representative telomere OB units*.

| RMSD (Å) | Sp-Ten1 | Sn-α3 | Sc-Cdc13N | h-Tpp1 | h-Pot11 | h-Pot12 | Sn-α1 | Sn-α2 | min | max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sp-Stn1N | 1.1 | 1.8 | 1.5 | 1.7 | 1.8 | 1.9 | 2.0 | 1.8 | 1.1 | 2.0 |

|

|

||||||||||

| Sp-Ten1 | 2.1 | 1.5 | 1.6 | 2.1 | 2.0 | 2.1 | 2.1 | 1.1 | 2.1 | |

|

|

||||||||||

| Sn-α3 | 1.7 | 2.3 | 2.4 | 2.6 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 1.7 | 2.6 | ||

|

|

||||||||||

| Sc-Cdc13N | 2.2 | 2.4 | 2.3 | 2.6 | 2.4 | 1.5 | 2.6 | |||

|

|

||||||||||

| h-Tpp1 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 2.2 | 2.2 | 1.6 | 2.3 | ||||

|

|

||||||||||

| h-Pot1-1 | 1.7 | 0.9 | 1.6 | 0.9 | 2.4 | |||||

|

|

||||||||||

| h-Pot1-2 | 1.6 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 2.6 | ||||||

|

|

||||||||||

| Sn-α1 | 1.7 | 0.9 | 2.6 | |||||||

|

|

||||||||||

| Sn-α2 | 1.5 | 2.5 | ||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

Only amino acid residues in the structurally conserved OB core (n = 42-49) were included in pairwise superpositions.

Structural diversity outside of the conserved beta core is readily apparent. For example, the N-terminal OB barrel “lid” comprises segments of extended structure plus a short helix in most OB units, but in Ct-Stn1N, this region constitutes a large subdomain sitting on top of the OB fold (Fig 3 (c)). Insertions are apparent in loops connecting beta strand core elements. The L12 loop connecting strands S1 and S2 normally comprises between 0-16 residues but contains 43 residues in the N-terminal OB fold of Rpa70 (Rpa70N in Fig 3(d)) and 33 residues in the C-terminal OB fold of Sn-TEBPα (Sn-TEBPα3 in Fig 3(d)). Insertions such as these in L12 of h-Rpa70N and Sn-TEBPα3 were likely fixed in the course of evolution because these provided some advantageous function. The structure of Rpa70N shows at least a portion of the L12 insertion making contact with a helical peptide element derived from the tumor suppressor protein p53, suggesting that a function of insertions may be to increase contact surface with other proteins active in DNA repair and cell cycle check points (Bochkareva et al., 2005). In the structure of Sn-TEBPα complexed with Sn-TEBPβ and single-stranded DNA, the L12 insertion in Sn-TEBPα3 contributes to interactions with an oligopeptide element derived from Sn-TEBPβ (Horvath et al., 1998).

Insertion in the region connecting L23 and S3 has occurred for at least three DNA-binding telomere OB proteins. In DNA-binding OB units derived from Sc-Cdc13, Sn-TEBPα and h-Pot1, the L23 insertion exceeds 10 residues (24 in Sc-Cdc13D, 13 in Sn-TEBPα1 and 28 residues in h-Pot1-2). As seen in the NMR structure of Sc-Cdc13D complexed with single-stranded DNA, the L23 insertion contributes a significant portion of the DNA-protein interface (Mitton-Fry et al., 2004). Analysis of the dynamic properties of Sc-Cdc13D by NMR showed that the L23 insertion is folded with similar topology in both unliganded and DNA-bound states (Eldridge and Wuttke, 2008). Motions in the slow (ms) and intermediate (μs) timescales respond to DNA-binding, however, indicating that L23 residues participate in an induced-fit type of mechanism for molecular recognition of telomere DNA (Eldridge and Wuttke, 2008).

Structural roles played by analogous L23 insertions found in Sn-TEBPα1 and h-Pot1-2 are less clear but apparently do not involve direct contact with DNA. The structure of h-Pot1 complexed with telomere DNA shows that the L23 insertion found in h-Pot1-2 fits over the S1bS2S3 beta sheet and thus occludes OBbCS (Lei et al., 2004), possibly so as to block interaction with other proteins at this contact surface. Comparison of several crystal structures containing Sn-TEBPα1 shows that the L12 insertion in that OB unit can adopt a range of positions (Horvath et al., 1998; Classen et al., 2001; Peersen et al., 2002; Theobald and Schultz, 2003; Buczek and Horvath, 2006a). In some of these, it appears as an appendage, and temperature factors in these cases are elevated, indicating L12 insertion residues are flexible and likely dynamic in solution.

Elaboration of the C34 element is apparent in several examples: in Sc-Cdc13N (described above), in the DNA-binding OB fold unit of Sc-Cdc13 (compare Sc-Cdc13N and Sc-Cdc13D, Fig 3 (e)), and also in the C-terminal OB folds of Rpa70C and Sn-TEBPα3 (Fig 3 (d, e)). In addition to constructing a dimer interface, C34 elaboration in Sc-Cdc13N contributes to binding of a helical peptide element derived from the catalytic subunit of the polymerase α/primase complex (Sun et al., 2011). The C34 elaboration in Rpa70C appears to provide structural reinforcement for an equally large L12 insertion. Concave surfaces and grooves apparent for this C34 + L12 elaboration in Rpa70C suggest a role in binding DNA or peptide elements in other proteins. In Sn-TEBPα3 at least a portion of the C34 + L12 elaboration serves to increase the Sn-TEBPα–β protein-protein interface (Horvath et al., 1998), which is critical for cooperative DNA binding (Fang et al., 1993; Buczek et al., 2005).

Evolutionary relationships

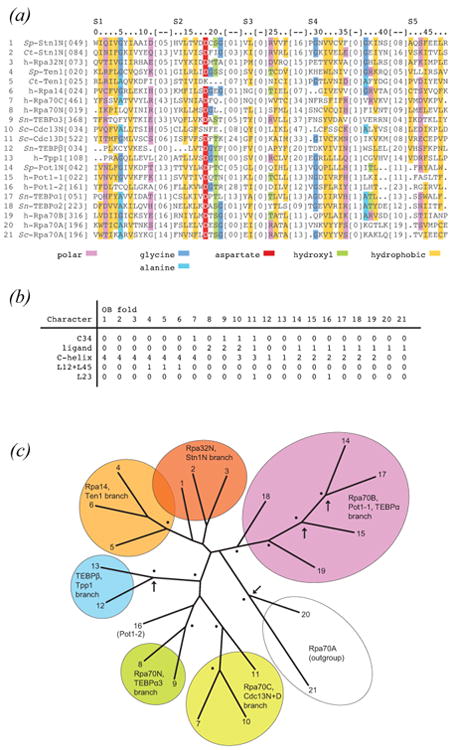

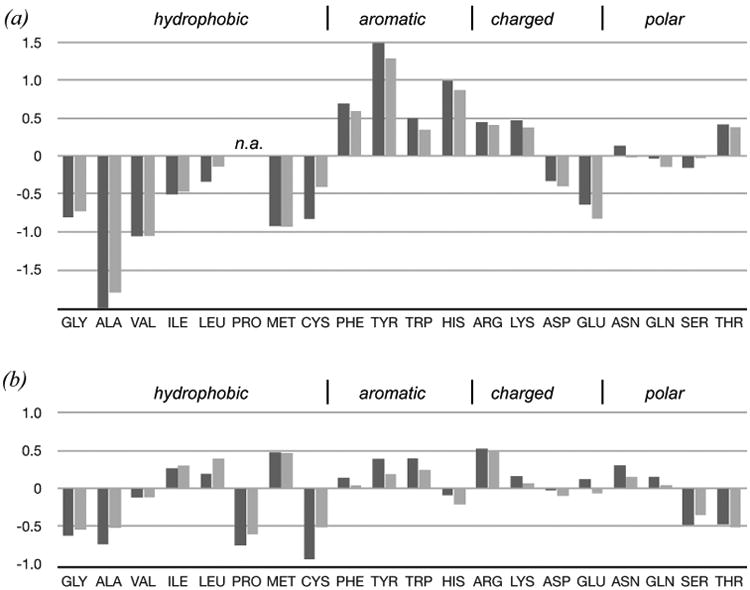

OB proteins likely evolved from a single common ancestor (Theobald and Wuttke, 2005); therefore, it is reasonable to consider evolutionary paths by which telomere OB units and RPA OB units were derived. Telomere and RPA OB units can be grouped into clades on the basis of homologous structural features (e.g. disposition of C-helix) and on the basis of analogous function (e.g. binding directly with single-stranded DNA). After completing the structural alignment of telomere and RPA OB folds (Fig 3), I wondered if evolutionary relations among the OB units could be inferred from amino acid character in the corresponding sequence alignment. Figure 4(a) shows the structure-based alignment of 21 OB fold amino acid sequences. This alignment is similar to a structure-based alignment of OB fold proteins involved in nucleic acid recognition (Theobald et al., 2003b) and a structure-based alignment of a more limited set of DNA-binding telomere OB fold proteins (Horvath, 2008a).

Figure 4.

Evolutionary history of telomere OB proteins. See on-line version for color; print version lacks color. (a) Amino acid sequences corresponding with structurally conserved elements (S1 – S5, labeled) were aligned on the basis of alpha carbon structural superpositions. Indexes (top of alignment) reference positions within the sequence alignment beginning with zero and ending with 48. To calculate the position within any one OB protein simply add the alignment index and [inserted residues] to the [first position] provided. Sequence positions meeting chi-squared test criteria for significance are color coded as indicated. (b) Morphological and binding function characters of OB proteins are as follows: “C34” scored 1 if more than 30 residues connect strands S3 and S4, and scored 0 otherwise; “ligand” scored 0 if current structures do not contain a ligand at the classical oligo-binding site, scored 1 if this ligand is single-stranded DNA, and scored 2 if this ligand is polypeptide; “C-helix” scored 0 if the C-helix is missing (e.g. h-Rpa70A), scored 1 if the C-helix is displaced to the back of the OB fold (h-Tpp1 and Sn-TEBPβ), scored 2 for equatorially positioned C-helix (e.g. h-Pot1 and Sn-TEBPα1), scored 3 for a three-helix cluster (Sc-Cdc13N and Sc-Cdc13D), and scored 4 for axially positioned C-helix (e.g. Stn1N); “L12+L45” scored 1 if the combined number of residues in L12 and L45 is less than 10 residues (Ten1 and Rpa14), and scored 0 otherwise; L23 scored 1 if the number of residues in the L12 connection between S2 and S3 exceeded 20 residues (Sc-Cdc13D and h-Pot1-2), and scored 0 otherwise. (c) Tree obtained from analysis of combined sequence and morphological characters. The tree is deeply rooted with each clade containing OB members from unicellular and metazoan lineages, implying gene duplications probably occurred in a common ancestor prior to divergence of ciliates, yeast, and vertebrates. Analysis of mixed data types was accomplished with MrBayes [Bayesian Analysis of Phylogeny, version 3.1.2, (Altekar et al., 2004)]. A total of 10,000 trees were sampled during the course of parallel Metropolis coupled Markov chain Monte Carlo simulations which applied gamma-distributed LG rates of amino acid exchange (Le and Gascuel, 2008). Nodes which were observed in more than 50% of sampled trees are labeled with a dot; nodes with greater than 50% frequency for analysis of sequence characters alone (no morphological characters) are also marked with an arrow. h-Rpa70A was chosen as the outgroup in this analysis because of long branch lengths obtained in preliminary analyses with ProtTest [ProtTest, Selection of Models of Protein Evolution, version 2.4 (Abascal et al., 2005)].

Pairwise comparison of representative sequences within the group considered here gave a range of percent identity from 4.7% (random) to 33.3% (homologous), with an average percent identity of 15% (Table 3). Universally conserved sequence motifs are absent. Consequently, more sensitive methods were applied to identify positions experiencing constraints during evolution (color coded in Fig 4(a)). Chi-squared statistical tests (with Yates correction for continuity) gave especially strong signals (p < 0.001) for positions 5 and 18, where the occurrence of Gly and Asp were significantly more frequent than expected by chance. Glycine at position 5 is thought to facilitate wrapping of S1 around the core, allowing this beta strand to form the outer edge of both SaS4S5 and SbS2S3 beta sheets. Ten of the 21 members use Gly at this position. Seven of the 21 OB proteins satisfy the same structural constraint with Ala, the second smallest amino acid residue, at position 5, but there are four examples that violate the Gly5/Ala5 guideline for constructing an OB fold.

Table 3. Percent identity for pairwise comparison of representative telomere OB sequences*.

| Identity (%) | Sp-Ten1 | Sn-α3 | Sc-Cdcl3N | h-Tppl | h-Pot1-1 | h-Pot1-2 | Sn-α1 | Sn-α2 | min | max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sp-Stn1N | 10.2 | 16.3 | 12.8 | 17.0 | 20.0 | 11.1 | 13.3 | 21.3 | 10.2 | 21.3 |

| Sp-Ten1 | 12.2 | 8.5 | 21.3 | 13.3 | 17.8 | 11.1 | 14.9 | 8.5 | 21.3 | |

| Sn-α3 | 12.8 | 12.8 | 11.1 | 13.3 | 8.9 | 14.9 | 8.9 | 16.3 | ||

| Sc-Cdcl3N | 8.9 | 4.7 | 16.3 | 16.3 | 15.6 | 4.7 | 16.3 | |||

| h-Tppl | 14.0 | 30.2 | 11.6 | 13.3 | 8.9 | 30.2 | ||||

| h-Potl-1 | 13.3 | 33.3 | 17.8 | 4.7 | 33.3 | |||||

| h-Potl-2 | 13.3 | 24.4 | 11.1 | 30.2 | ||||||

| Sn-α1 | 22.2 | 8.9 | 33.3 | |||||||

| Sn-α2 | 13.3 | 24.4 |

Only amino acid residues included in the structurally conserved OB core (n = 42-49) were compared.

Aspartate at position 18 of the alignment followed by glycine and threonine comes closest to defining a conserved sequence motif. Although each of these positions was associated with high chi-squared signals (Asp18 has the highest score encountered) exactly zero of the 21 telomere OB folds has an exact match to the putative Asp18Gly19[Thr/Ser]20Gly21 motif, highlighting the difficulty associated with defining diagnostic sequence criteria for this protein family. Asp18 and residues 19-21 define a tight turn at the end of S2 which is followed either immediately or closely by S3. The most likely explanation for conservation at these positions is that the combination of Asp18, Ser20/Thr20, and either Gly19 or Gly21 stabilizes the OB structure or an otherwise rarely encountered folding intermediate. Constraints dictating relatively high conservation for these residues appear to have vanished for two newly reported structures (Ct-Ten1 and Sc-Cdc13N), which retain no vestige of the motif.

Sequence positions define alternating hydrophobic/polar positions (gold/magenta in Fig 4(a)), a pattern which has been noted previously for nucleic acid-binding OB proteins (Theobald et al., 2003b). Inspection of the telomere and RPA OB structures shows this pattern corresponds with the inside/outside disposition expected for beta sheet structure surrounding a hydrophobic core. Of the two types of positions, hydrophobic character has been more strongly preserved as judged by chi-squared scores (gold, p < 0.001). Positions marked as polar are apparently more tolerant to accepting a hydrophobic residue (magenta, p < 0.01). This situation likely reflects high thermodynamic penalties for burying a polar moiety and relatively low penalties for leaving a hydrophobic group on the outside of the OB fold. Another explanation is that hydrophobic patches close to the surface of the protein may be necessary to form functional interaction surfaces.

Attempts to define evolutionary relationships among OB proteins on the basis of the structure-aligned amino acid sequences consistently yielded trees (not shown) with comb-like structure and only two clearly supported clades: one defined by h-Tpp1 and Sn-TEBPβ, and the second defined by h-Pot1-1, Sp-Pot1N, and Sn-TEBPα1 (nodes marked with arrows in Fig 4(c)). The close evolutionary relationship for members in these two clades has been previously supported by functional and structural similarity (Baumann and Cech, 2001; Lei et al., 2003; Lei et al., 2004; Xin et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2007). Encouraged by this result, I attempted to further detangle the other branches by including morphological characters and binding function (Fig 4(b)) in addition to sequence information. The resulting unrooted tree (Fig 4(c)) exhibits topology congruent with previously published phylogenies (Theobald and Wuttke, 2005; Horvath, 2008a) and includes additional clades and inferences.

One expected branch includes Stn1N, Rpa32N, Ten1 and Rpa14. Structure determinations of the Rpa32N–Rpa14 heterodimer (Bochkarev et al., 1999) and two examples of a Stn1N–Ten1 complex (Sun et al., 2009) show clear similarity at multiple levels of organization. Each member possesses an axially oriented C-helix (Fig 3(b)) that is a central structural element of the heterodimer interface (Bochkarev et al., 1999; Sun et al., 2009). The Ten1 and Rpa14 members have ablated L12 and L45 loops, a trait that appears to be derived since most OB units have substantially longer L12 and L45 loops. Winged helix-turn-helix motifs are found in C-terminal domains particular to members of the Stn1 and Rpa32 clade (Mer et al., 2000; Sun et al., 2009; Gelinas et al., 2009), further supporting the close relationship of Stn1 with Rpa32 deduced from functional homology and sequence similarity (Gao et al., 2007).

Conservation of structure for Stn1N–Rpa32N and Ten1–Rpa14 subcomplexes suggests a conserved function that is similar for both telomere maintenance and for DNA replication and repair. Indeed, the Stn1N-derived OB fold can substitute for Rpa32N to restore function in rpa32−/− deletion mutants of S. cerevisiae (Gao et al., 2007). The principle role for the Rpa32–Rpa14 heterodimer is to contribute to single-stranded DNA binding and simultaneously coordinate protein-protein association and exchange events. The Rpa32–Rpa14 heterodimer recruits Rpa70 via OB-OB interactions with Rpa70C, as viewed in a crystal structure of the RPA trimerization core (Bochkareva et al., 2002), and the C-terminal winged helix-turn-helix (WH) domain of Rpa32 recruits an assortment of DNA repair proteins as observed by NMR (Mer et al., 2000). Genetic and biochemical tests suggest that the Stn1–Ten1 heterodimer functions at telomeres similarly with the protein recruitment functions provided by Rpa32–Rpa14 at DNA replication forks and repair centers. Stn1 and Ten1 each bind with single-stranded DNA (Gao et al., 2007), and S. cerevisiae Stn1–Ten1 delivers telomerase and the DNA polymerase α/primase complex to telomeres in a regulated manner (Pennock et al., 2001; Puglisi et al., 2008).

In S. cerevisiae, telomerase and polymerase α/primase recruitment by Sc-Stn1–Ten1 works through interactions with Cdc13 (Qi and Zakian, 2000; Chandra et al., 2001; Sun et al., 2011). Telomerase recruitment may work differently in other organisms since in S. pombe this function is executed by a Sp-Pot1-associated subcomplex that includes Tpz1 and Ccq1 (Miyoshi et al., 2008). Nevertheless, DNA polymerase α/primase recruitment by a Stn1-centered complex appears conserved. In plants and humans, Stn1 interacts with the conserved telomere component protein Ctc1 (Miyake et al., 2009; Surovtseva et al., 2009) with analogous functional consequence to Stn1 and Cdc13 in budding yeast; both Cdc13 and Ctc1 appear to deliver polymerase α/primase to telomere ends for synthesis of the C+A-rich strand.

OB units associated with high-affinity single-stranded DNA-binding protein domains were grouped in a single clade, but two expected members were placed in orphan branches: h-Pot1-2 and Sp-Cdc13D. The second DNA-binding OB unit in the human Pot1 protein, h-Pot1-2 is surprisingly located at the base of a branch defined by h-Rpa70N and Sn-TEBPα3, OB units which are known to function in protein-protein interactions. The relatively large L23 insert found in h-Pot1-2 may lead to long-branch attraction with Sc-Cdc13D which is located on a neighboring branch and also has a large L23 insertion. And it is certainly possible that divergent evolution has scrambled the protein pedigree for h-Pot1-2.

The telomere protein Sc-Cdc13 presents a challenge for the molecular evolutionist because character traits give conflicting conclusions regarding homology. On the basis of DNA-binding function, Sc-CDC13D would be placed together with the h-Pot1-1/Sp-Pot1N/Sn-TEBPα1 clade. Apparent structural similarity and inferred homology noted for Sc-Cdc13D and Sn-TEBPα (Mitton-Fry et al., 2002; Theobald et al., 2003a) may need reevaluation in light of a newly determined structure for the N-terminal OB unit of Cdc13, Sc-Cdc13N (Sun et al., 2011). Sc-Cdc13N possesses two structural characters that are shared with Sc-Cdc13D, but not commonly found among other telomere OB folds: (i) a highly elaborated C34 element connecting strands S3 and S4, and (ii) replacement of the prototypical single C-helix with a cluster of three or more helices. Dali-derived structure matching corroborate structural similarity between Sc-Cdc13N and Sc-Cdc13D (Mitchell et al., 2010; Sun et al., 2011). In addition to these structural similarities with Sc-Cdc13N, differences in DNA recognition that distinguish Sc-Cdc13D from other telomere single-stranded DNA-binding OB folds (to be discussed further below) support the idea that Sc-Cdc13D was derived by gene duplication within an ancestral Sc-Cdc13 protein and not through divergence from an ancestral DNA-binding OB fold (Sun et al., 2011).

Similar to the puzzle of placing Sc-Cdc13D within the telomere OB family, conflicting evidence exists for the relation between Cdc13 and Rpa70. The Rpa70–Rpa32–Rpa14 complex functions at DNA replication forks and during the course of DNA repair and recombination reactions [reviewed in (Wold, 1997; Fanning et al., 2006)]. The Cdc13–Stn1–Ten1 complex is similarly organized with large, medium and small subunits and functions to regulate DNA synthesis at telomeres. Argument by analogy leads to a conclusion that Rpa70 and Cdc13 are homologs; however, structural differences cast this Cdc13–Rpa70 relation in doubt. One difference involves the number of DNA-binding OB units. The DNA-binding domain of Cdc13 comprises a single OB unit; the high-affinity DNA-binding domain of Rpa70 comprises two OB units. Tandem DNA-binding OB units appears to be the ancestral state, since other telomere OB proteins from Sterkiella nova, fission yeast, and humans also use two OB units for binding single-stranded telomere DNA. Evolution may have replaced a primordial two-OB DNA-binding domain in Cdc13 so as to cope with a telomerase template “crisis” in the hemiascomycetes lineage –– a crisis that also lead to heterogeneous telomere DNA sequences and loss of double-stranded DNA binding factors such as TRF1 (Li et al., 2000; Teixeira and Gilson, 2005).

Although the DNA-binding domains of Sc-Cdc13 and Rpa70 are structurally different, the N-terminal and DNA-binding domains of Sc-Cdc13 share structural features also found in the C-terminal domain of Rpa70. The phylogram derived from Baysian analysis of telomere protein and RPA-derived OB units placed these three OB units (Sc-Cdc13N, Sc-Cdc13D, h-Rpa70C) in one clade (Fig 4). Structure determination of the remaining two predicted OB units within Sc-Cdc13 could help resolve the question of when and how Sc-Cdc13 and Rpa70 diverged during evolution. These questions also call attention to the possibility that certain OB units within otherwise homologous telomere and RPA proteins may have been lost or reinvented.

The human Sn-TEBPβ ortholog is h-Tpp1 (formerly PIP1, also PTOP) initially characterized as a protein that interacts with Pot1 and other telomere components (Ye et al., 2004; Liu et al., 2004; O'Connor et al., 2006). Homology with Sn-TEBPβ is based on distinguishing structural features shared by h-Tpp1 and Sn-TEBPβ that are rarely encountered or not apparent for other telomere OB proteins (Wang et al., 2007). For instance, the C-helix in both Sn-TEBPβ and h-Tpp1 is displaced from its prototypical location alongside the OB core and instead coalesces with L45 and elements of the N-terminal extension. The h-Tpp1 + Sn-TEBPβ branch stands out because of high probability confidence values (this node was observed in ∼90% of sampled trees) and also because it is the only branch in the tree that lacks an RPA-derived member. This last observation suggests the ancestral protein from which Sn-TEBPβ and h-Tpp1 descended may have been fixed in the eukaryotic lineage because it acquired a highly advantageous function at telomeres that was dispensable at DNA replication forks and DNA repair centers.

Given the critical importance of telomeres for genome stability one would expect h-Tpp1/Sn-TEBPβ orthologs in all extant taxa that maintain chromosome ends with telomeres and telomerase. A search for Sn-TEBPα and Sn-TEBPβ orthologs in Euplotes crassus (a distantly related marine cousin to Sterkiella nova) revealed two proteins with telomere single-stranded DNA-binding function and high sequence similarity to OB units derived from the N-terminal domain of Sn-TEBPα, but no match for Sn-TEBPβ (Price, 1990) [also reviewed in (Linger and Price, 2009)]. A similar situation appeared to hold for humans and fission yeast when Pot1 was first reported on basis of sequence similarity with Sn-TEBPα1 (Baumann and Cech, 2001). More recently, Sn-TEBPβ orthologs have been identified in humans (Xin et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2007), Schizosaccharomyces pombe (Miyoshi et al., 2008), Candida albicans (Yu et al., 2008), Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Lee et al., 2008; Lee et al., 2010), Candida parapsilosis and Lodderomyces elongisporus (Yen et al., 2011). Genetic tests for function in yeast clearly indicate that Sn-TEBPβ homologs function to coordinate telomere homeostasis (Miyoshi et al., 2008; Lee et al., 2010; Yen et al., 2011).

Structural character of OB interfaces

OB protein modules provide interaction surfaces for the recognition of diverse ligands including oligosaccharides, single-stranded nucleic acid, oligopeptide, and proteins. Understanding telomere OB protein function requires an appreciation for interactions leading to molecular recognition. With this goal in mind, this section examines interfaces observed in crystal and NMR structures of telomere OB proteins. Relevant RPA-derived structures provide perspective and hint at analogous assemblies likely at play for telomere protection and maintenance. The structures can be roughly divided into three categories according to ligand type and complexity: OB-oligomer, OB-OB, and composite OB. In the OB-oligomer category, telomere OB proteins bind with polypeptide or single-stranded DNA ligands (Fig 5). The OB-DNA interfaces have been expertly reviewed previously (Theobald et al., 2003b; Croy and Wuttke, 2006). The current analysis revisits some of this previous work so as to compare these OB-DNA interfaces with new OB-DNA structures and the second category of OB-OB interfaces (Fig 6). Composite OB structures constructed with both OB-oligomer and OB-OB interaction types feature more elaborate and inter-woven interfaces (Fig 7).

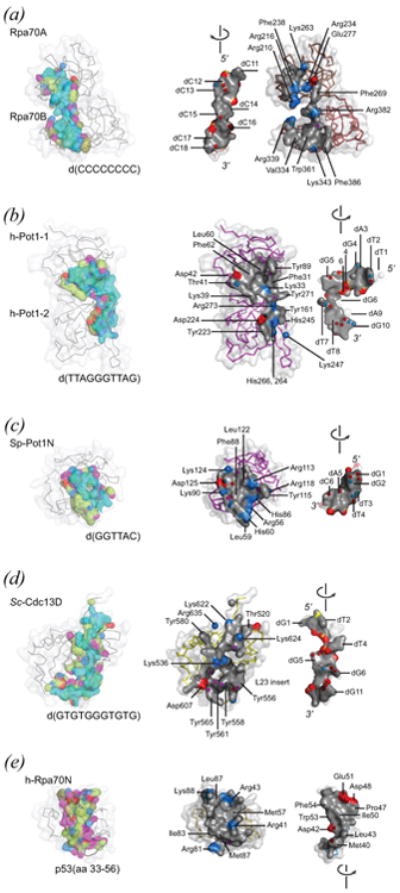

Figure 5.

Simple OB-oligomer interfaces. See on-line version for color; print version lacks color. Each interface is depicted in two ways: as found in the complex (left-hand view) and in an exposed form generated by separating the DNA or peptide ligand from the OB component (right-hand view). In the complexed model, protein and DNA are both wrapped in a semi-transparent accessible surface. Protein is additionally rendered as an alpha carbon trace. DNA is colored cyan. Protein residues making contact with ligand (4 Å cutoff) are colored according to chemical type with aliphatic carbon atoms colored olive or lime, hydrogen bond acceptor groups colored red, hydrogen bond donor groups colored blue, groups ambivalent with respect to hydrogen bond donor/acceptor quality colored magenta. In the dissociated model, contact residues of the OB-oligomer interface are rendered as solid accessible surfaces (grey, with positively charged surface blue, and negatively charged surface red), and electronegative atoms making hydrogen bonds across the interface shown as spheres. Landmark residues are labeled. PDB identifiers are as follows: (a) 1jmc, major DNA-binding domain derived from Rpa70 (residues 183-420) complexed with d(C8); (b) 1xjv DNA-binding domain derived from h-Pot1 (residues 6-299) complexed with d(TTAGGGTTAG); (c) 1qzh, N-terminal OB unit derived from Sp-Pot1 (residues 5-174) complexed with d(GGTTAC); (d) 1s40, minimal DNA-binding domain derived from Sc-Cdc13 (residues 500-686) complexed with d(GTGTGGGTGTG); (e) 2b3g, N-terminal OB of h-Rpa70, h-Rpa70N (residues 1-128) complexed with p53-derived peptide (residues 33-56).

Figure 6.

OB-OB interfaces as found in simple heteromeric telomere and RPA OB protein complexes. See on-line version for color; print version lacks color. The protein-protein interface is depicted in two ways: as found in the complex (left-hand view) and as exposed by separating protein components (right-hand view). In the model of the complex, aliphatic carbon atoms at the interface (4 Å cutoff) are colored lime for one component and olive for the second component. Groups with hydrogen-bonding potential are colored as in Figure 5 with hydrogen bond donor groups red, acceptor groups blue, and ambivalent (donor or acceptor) groups magenta. In the exposed view, interfaces are rendered as solid accessible surfaces (grey), with charged surfaces highlighted (red, negative; blue, positive), and electronegative atoms making hydrogen bonds across the interface depicted as spheres. Certain landmark residues are labeled. PDB identifiers are as follows: (a) 3kf6, Sp-Ten1 (full-length protein) associated with the N-terminal domain of Sp-Stn1 (residues 2-159); (b) 3kf8, Ct-Ten1 (full-length protein) associated with the N-terminal domain of Ct-Stn1 (residues 2-217); (c), 2pi2, h-Rpa14 (full-length protein, residues 2-118) associated with the N-terminal domain of h-Rpa32 (residues 41-176); (d) 1l1o, h-Rpa14 (full-length, residues 3-117) and h-Rpa32N (residues 44-171) associated with the C-terminal domain of h-Rpa70 (residues 439-616).

Figure 7.

Composite OB interfaces as found in intricate multi-subunit OB protein complexes. See on-line version for color; print version lacks color. Interface surfaces are rendered and color-coded as described in Figures 5 and 6. (a) Multiple views are shown for homodimeric Sc-Cdc13N (residues 13-224) complexed with two copies of a Pol1-derived peptide (residues 216-245). One Pol1-derived peptide is shown as an accessible surface and a second is shown as a ribbon cartoon (blue). The (Sc-Cdc13N)2 OB-Pol1 interface involves residues contributed by each of the C2 symmetry-related Sc-Cdc13N subunits. The OB-peptide interface is highlighted in the top view, as found in the complex (left-hand view) and as separated components (right-hand view). The homodimer interface is highlighted in the bottom view of panel (a). Note that the two surfaces are nearly equivalent, and for this reason residue labels are only provided for one subunit. (b) Multiple views are shown for Sn-TEBPα and Sn-TEBPβ complexed with single-stranded telomere DNA. The DNA-protein interface formed between Sn-TEBPαβ and d(TTTTGGGGTTTTGGGG) is highlighted in the top view of panel (b). This structure contains a more complete view of the DNA-interface compared with previously published structures. It was determined to the 1.88 Å resolution limit (Rfree = 0.195, Rwork = 0.165) with use of an engineered protein constructed by fusing DNA-binding OB units of Sn-TEBPα and Sn-TEBPβ. The DNA occupies two connected binding surfaces – one comprising OB units Sn-TEBPα1 and Sn-TEBPα2 (labeled α), and a second involving Sn-TEBPβ and surfaces on Sn-TEBPα1 and Sn-TEBPα2 (labeled αβ). The protein-protein interface of Sn-TEBPα–β is highlighted in the bottom view. This structure was determined to the 1.91 Å resolution limit with use of full-length Sn-TEBPα and Sn-TEBPβ bound to d(GGGTTTTGGGG), which is a 5′-truncated form of the telomere single-stranded DNA. The protein-protein interface (grey with charged surfaces and hydrogen-bonded atoms highlighted) dwarfs contacts made by DNA with Sn-TEBPβ (yellow). PDB identifiers are as follows: (a) 3oiq, (Sun et al., 2011); (b) 2i0q, (Buczek and Horvath, 2006a).

The DNA-binding domain of Rpa70 bound with d(C8) is shown in Fig 5(a). DNA binds at the classical oligo-binding surface found at each of two OB units, and follows a straight path with 5′-proximal nucleotides contacting Rpa70A and 3′-proximal nucleotides contacting Rpa70B. The DNA strand orientation is the same for both Rpa70A and Rpa70B, with 5′→3′ pointed to the “back” when the OB unit is oriented as in Fig 2(a) with L45 on top, L12 below, and the oligomer binding surface on the right-hand side. The same DNA and OB unit polarity is observed in OB-DNA complexes of telomere proteins h-Pot1 (Fig 5(b)) and Sn-TEBPα (not shown), which also employ two OB units to contact a similar number of nucleotides. Different from the situation seen for Rpa70, DNA in these complexes bends sharply so as to follow a path defined by oligo-binding surfaces on the two OB units. OB-DNA interfaces seen for single-OB units derived from Sp-Pot1 (Fig 5(c)) and Sc-Cdc13 (Fig 5(d)) conserve the 5′→3′ DNA strand polarity. As pointed out previously, conservation in DNA strand polarity argues for descent by divergent evolution from a common OB ancestor (Theobald et al., 2003b).

Table 4 compares features of six OB-DNA interfaces for RPA and telomere proteins. The S. pombe Pot1 protein likely uses two OB units for binding DNA (Trujillo et al., 2005; Croy et al., 2006), meaning values such as surface area reported for the Sp-Pot1N–DNA complex reflect a portion of the total interface since the crystal structure was obtained for one OB unit. Also, the very large interface observed in a crystal structure of S. nova telomere-derived DNA complexed with DNA-binding portions of Sn-TEBPα and Sn-TEBPβ was divided into two parts so as to facilitate comparisons (the full DNA-TEBPαβ interface is summarized in Table 6). These parts correspond with 5′ and 3′-terminal halves of the 16-nucleotide S. nova telomere single-stranded DNA. Nucleotides of the 5′-half bind with a surface on Sn-TEBPα called the α-site; nucleotides of the 3′-half bind with a more intricate surface called the αβ-site that involves three OB units: the two DNA-binding OB units of Sn-TEBPα and portions of the OB unit of Sn-TEBPβ.

Table 4. Character of OB-DNA interfaces**.

| Character | Rpa70A+B | h-Pot1-1+2 | Sp-Pot1N | Sc-Cdc13D | Sn-TEBP α-site | Sn-TEBP αβ-site |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OB units | 2 | 2 | 1* | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| PDB id | 1jmc | 1xjv | 1qzh | 1s40 | 1k8g | 2i0q |

| DNA sequence | CCCCCCCC | TTAGGGTTAG | GGTTAC | GTGTGGGTGTG | T2TTGGGG8 | T9TTTGGGG16 |

| SA% (Å2) | 1,387 | 1,610 | 875 | 1,666 | 1,303 | 1,678 |

| SA / OB (Å2) | 694 | 805 | 875 | 1,666 | 652 | 559 |

| DNA atoms (apolar)£ | 93 (13) | 124 (29) | 65 (11) | 124 (28) | 95 (12) | 98 (18) |

| Protein atoms (apolar)& | 96 (56) | 132 (72) | 90 (37) | 130 (77) | 98 (48) | 123 (59), α 86 (40), β 37 (19) |

| Salt bridge (bidentate)∞ | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 4 (2) |

| Phosphate H-bond, not salt$ | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 1 |

| H-bonds (bidentate)¢ | 7 | 15 (2) | 10 (2) | 8 | 14 (6) | 9 (2) |

| Base atoms | 50 | 65 | 44 | 57 | 59 | 54 |

| Aromatic (base)§ | 49 (34) | 60 (54) | 20 (14) | 38 (12) | 54 (45) | 53 (41) |

| C2′ atoms | 3 | 6 | 3 | 7 | 2 | 3 |

| C2′ contact (apolar) | 7 (7) | 10 (2) | 4 (1) | 19 (16) | 4 (3) | 7 (7) |

| Thymine C7 atoms | 0 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 4 |

| C7 contact (apolar) | 0 | 6 (5) | 0 | 1 (0) | 5 (0) | 7 (0) |

| Tyrosine / total residues (%) | 0 / 28 (0) | 5 / 31 (16.1) | 1 / 20 (5.0) | 7 / 28 (25.0) | 5 / 23 (21.7) | 9 / 47 (19.2) |

Values differ modestly from previously published values because these were computed here for protein and DNA components with first shell solvent molecules included. Also, the DNA-protein complex analyzed for Sn-TEBPα has clear electron density for nucleotides G2, G3 and G4, positions which were missing in previously published structures.

Sp-Pot1 DNA-binding domain is thought to comprise two OB units. Only the N-terminal OB unit has been structurally characterized, meaning these quantitative values likely reflect a portion of the full DNA-OB complex.

Surface area calculated by the program volume within the 3V package (Voss and Gerstein, 2010), using a 1.4 Å probe radius and 0.25 Å grid spacing. Note that results reported here include contributions from the first hydration shell and differ from literature reported values in some cases.

A DNA atom was counted if it was located within 4 Å of the DNA-protein interface. Apolar atoms of DNA (counted given in parentheses) were defined as aliphatic carbons of the deoxyribose moiety and the C5-methyl of the thymine base group.

Apolar atoms defined as any aliphatic carbon lacking aromatic character.

Salt bridge defined by phosphate oxygen less than 3.2 Å from positively charged hydrogen bond donor. Bidentate salt bridges involve two hydrogen bonds contributed by different N atoms of one arginine residue.

Phosphate H-bond (not salt) defined by non-bridging phosphate oxygens within 3.2 Å of a neutral (uncharged) hydrogen bond donor with appropriate geometry.

Hydrogen bond defined by complementary donor/acceptor pair within 3.2 Å with appropriate geometry that is not already included in the salt bridge count. Bidentate hydrogen bonds are constructed by two different atoms of one amino acid residue H-bonding with two different atoms of one DNA base moiety.

Aromatic contacts counted for atoms within 4.0 Å of DNA contributed by protein aromatic moieties, which includes the sidechains of Tyr, Phe, Trp, and His residues, and the guanidinium group of Arg residues. Numbers in parentheses count the number of aromatic protein atoms in close proximity with base moieties of the DNA.

Table 6. Character of composite OB interfaces.

| Character | Cdc13N2•Pol1 | Cdc13N(Pol1)2• Cdc13N′ | αNβΔ–DNA^ | (DNA)α–β‡ | α3–β162-195 | (DNA)α–βΔ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OB units | 2 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 3 |

| PDB id | 3oiq | 3oiq | n.a. | 2i0q | 2i0q | 2i0q |

| Surface area% (Å2) | 1,280 | 1,514 | 2,996 | 4,176 | 1,874 | 2,232 |

| Protein 1 (apolar)& | Cdc13N, 50 (24) | Cdc13N, 75 (36)# | α, 178 (86) | β, 261 (116) | β162-195, 116 (56) | βΔ, 145 (60) |

| Protein 2 (apolar) | Cdc13N′, 27 (5) | Cdc13N′, 62 (26) | β, 37 (19) | α, 237 (88) | α3, 102 (36) | α, 138 (53) |

| Component 3 (apolar) | Pol1, 84 (43) | n.a. | DNA, 193 (30) | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| Salt bridges (bidentate)∞ | 7 (2) | 0 | 7 (2) | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| Ion pairs@ | 3 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| H-bonds¢ | 7 | 3 | 21 | 28 | 14 | 13 |

| Tyrosine / total residues (%) | 2 / 34 (5.9) | 2 / 31 (6.5) | 9 / 47 (19.1) | 7 / 96 (7.3) | 4 / 48 (8.3) | 3 / 54 (5.6) |

Although the two Sc-Cdc13N subunits are symmetrical, the number of contact atoms differ in number because first-shell waters were assigned to the first subunit.

The DNA-protein interface contained in this complex is also analyzed in Table 4 as TEBPα–DNA and TEBPαβ–DNA subcomplexes

The TEBPα–β interface is analyzed as a complete protein-protein interface and also as OB-peptide [α3–β162-195] and OB-OB [(DNA)α–βΔ] subcomplexes (see columns to the right).

Surface area buried as a consequence of DNA binding with protein ranges from 875 (Sp-Pot1N) to 1678 (αβ-site) Å2, and the average value is 1,420 Å2 (with Sp-Pot1N excluded it is 1,530 Å2). These surface area calculations were obtained by assuming the solvent accessible surface of individual dissociated components can be estimated by structures seen in the associated complexes. This assumption introduces some systematic error since single-stranded DNA is likely to become more or less extended when free in solution. Even so, the values have some meaning and are useful for making comparisons within the OB-DNA category and with OB-protein interfaces described below.

When normalized by the number of OB units, the Sc-Cdc13 interface with DNA, measuring 1,666 Å2 OB−1, is the largest of this group. As explained previously (Mitton-Fry et al., 2004), the large contact surface of Sc-Cdc13D results from a large L23 insertion. Normalized in this way, the Sp-Pot1N interface with DNA, measuring 875 Å2 OB−1, is also somewhat larger than the median value of 750 Å2 OB−1. Consistent larger than average surface area per OB unit suggests that additional surfaces are accessible to DNA when single OB units are not involved in contacts with neighboring OB units. This OB versus DNA competition for limited surfaces on any one OB unit explains why the normalized DNA-buried surface area is so small (560 Å2 OB−1) for the three DNA-binding OB units comprising the Sn-TEBP αβ-site.

On average, a DNA-OB interface is constructed with 100 DNA atoms and 110 protein atoms. Generally, more than half of the atoms contributed by DNA belong to base groups (average, 55 atoms). Significantly fewer apolar atoms are contributed by DNA (average, 19 atoms). The number of apolar DNA atoms is also low by comparison with apolar protein atoms (average, 58 atoms). In this atom counting analysis, an atom was considered part of the interface if it came within 4 Å of an atom contained within the partner molecule, and apolar atoms were defined as aliphatic carbons with sp3 molecular orbital centers. Few apolar atoms contributed by DNA is likely a consequence of the fact that most atoms in DNA are either polar or heteroaromatic and only ∼25% are aliphatic.

The low proportion of hydrophobic contact surface characteristic of single-stranded DNA has consequences for the thermodynamic balance of enthalpy and entropy driving DNA-protein association. Large favorable entropy terms characterize processes that bury hydrophobic surfaces such as folding of globular, water soluble proteins. Studies of the thermodynamic character of Sn-TEBPαN binding with single-stranded d(T4G4) DNA showed that this process was entropy neutral (ΔS = 0) and entirely enthalpy driven (ΔH < 0) at 20 °C (Buczek and Horvath, 2006b). At higher temperatures entropy opposed DNA binding and enthalpy compensated by becoming larger in magnitude. This same pattern of favorable enthalpy and unfavorable entropy terms was also measured for Sp-Pot1N binding with d(GGTTAC) and single-nucleotide substitution variants (Croy et al., 2008). These trends indicate that single-stranded telomere DNA binding is not strongly driven by the hydrophobic effect, consistent with few apolar atoms contributed by single-stranded DNA at the OB-DNA interface.