SUMMARY

Estrogen receptor (ER) is expressed in approximately 70% of newly diagnosed breast tumors. Although endocrine therapy targeting ER is highly effective, intrinsic or acquired resistance is common, significantly jeopardizing treatment outcomes and minimizing overall survival. Even in presence of endocrine resistance, a continued role of ER signaling is suggested by several lines of clinical and preclinical evidence. Indeed, inhibition or down-regulation of ER reduces tumor growth in preclinical models of acquired endocrine resistance, and many patients with recurrent ER+ breast tumors progressing on one type of ER-targeted treatment still benefit from sequential endocrine treatments that target ER by a different mechanism. New insights into the nature and biology of ER have revealed several mechanisms sustaining altered ER signaling in endocrine-resistant tumors, including deregulated growth factor receptor signaling that results in ligand-independent ER activation, unbalanced ER co-regulator activity, and genomic alterations involving the ER gene ESR1. Therefore, biopsies of recurrent lesions are needed to assess the changes in epi/genomics and signaling landscape of ER and associated pathways in order to tailor therapies to effectively overcome endocrine resistance. In addition, more completely abolishing the levels and activity of ER and its co-activators, in combination with selected signal transduction inhibitors or agents blocking the upstream or downstream targets of the ER pathway, may provide a better therapeutic strategy in combating endocrine resistance.

Keywords: Breast cancer, Estrogen receptor, Endocrine resistance, Crosstalk, Co-regulators, ER genomic aberrations

Introduction

About 70% of breast cancers express estrogen receptor alpha (ER)1. Molecular profiling of breast cancers has identified several intrinsic breast cancer subtypes2-4. The majority of ER positive (+) breast cancers are classified as either luminal A or luminal B.2 Luminal A tumors are typically more sensitive to therapy, while luminal B tumors show a more aggressive and endocrine-resistant phenotype2-4. ER and its ligand, estrogen, play a critical role in the development and progression of breast cancer5. Accordingly, endocrine therapies, which target ER activity, are standard treatments for patients with ER+ breast cancer in both the early and the advanced/metastatic stages. But, despite the substantial benefit from endocrine treatment, resistance is still common, and it significantly influences overall morbidity and mortality in patients.

Endocrine therapy modalities are based on three main strategies: depriving the tumor of its ligand by systemically depleting estrogen production using aromatase inhibitors (AIs) or ovarian suppression; inhibiting estrogen binding to ER by using selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) such as tamoxifen; or degrading ER using selective estrogen receptor down-regulators (SERDs) such as fulvestrant, which result in a more complete inhibition of the ER pathway. Tamoxifen, which has been used as an effective anti-estrogen therapy since the 1970s6,7, continues to represent the standard adjuvant treatment for many pre-menopausal women with ER+ tumors, though recent results also suggest a potential role for adding ovarian suppression to tamoxifen or using AIs instead for higher risk tumors in this setting8,9. Over the past decade AIs have been shown to be more effective than tamoxifen in postmenopausal women in both early and advanced stages of ER+ breast cancer10. A more potent inhibition of ER with SERDs, such as fulvestrant, preferably at high doses as suggested from recent studies (reviewed in 11), may improve patient outcome by preventing or delaying resistance in both early and metastatic settings.

But despite these favorable outcomes, intrinsic or acquired resistance frequently occurs with all endocrine therapies. In particular, in the metastatic setting about 50% of patients do not benefit from endocrine treatment despite the presence of ER (intrinsic/de novo resistance), and all patients who initially respond to the therapy eventually relapse (acquired resistance)12. Loss of ER has only been reported in less than 25% of tamoxifen-resistant tumors13,14 and references therein. The fact that the majority of the treatment-refractory tumors still express ER, and that subsequent sequential treatments with different endocrine therapies are often still effective in these patients15 as well as in preclinical models of acquired endocrine resistance16,17, implicate a continued, albeit altered, role for ER at the time of resistance.

ER structural/functional organization and activity

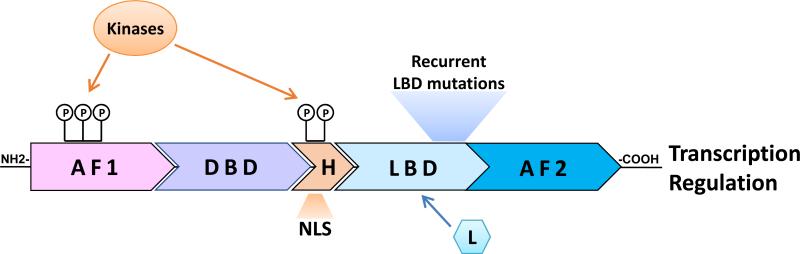

Estrogen receptor is a member of the family of ligand-dependent nuclear receptor transcription factors, sharing the common structural and functional organization of other members of this family (Figure 1). The N-terminus of ER contains a ligand-independent transcriptional activity known as activation function 1 (AF1)18. The center of the molecule harbors the DNA-binding domain (DBD) and the hinge domain. The DBD mediates ER binding to specific sequences on the DNA called estrogen responsive elements (EREs), while the hinge region includes a nuclear localization signal (NLS) and is also believed to mediate important kinase signaling that regulates ER activity and function19. The C-terminus of the ER molecule contains the ligand-binding domain (LBD) and the activation function 2 domain (AF2), which is responsible for the ligand-dependent activation of ER in regulating gene expression18. As will be discussed below, several hotspot point mutations, recently identified in metastatic ER+ endocrine resistant tumors, are clustered within the LBD (see below).

Figure 1. Estrogen Receptor α (ER) structural/functional organization.

Structural/functional domains of ER include the ligand-independent activating function 1 (AF1); the DNA binding domain (DBD); the hinge region (H) harboring a nuclear localization signal (NLS); and the ligand binding domain (LBD) containing also the ligand (L)-dependent activating function 2 (AF2). Posttranslational modifications of ER, such as phosphorylation (P), by multiple cellular kinases on ER at sites residing within the AF1 and the H domains modify ER activity and sensitivity to various endocrine treatments. Gain-of-function recurrent mutations clustered in a hotspot within the LBD have recently been identified in ~20% of metastatic ER+ endocrine resistant tumors.

ER activity includes genomic and non-genomic functions. The genomic nuclear functions include a classical activity, where ER binds to EREs, and a non-classical activity, where ER is tethered to other transcription factors, functioning as a co-regulator to modulate transcriptional activity on different sites, such as AP1 and Sp120. Both classical and non-classical genomic signaling regulate gene transcription leading to proliferation, survival, and other key tumor characteristics such as angiogenesis and invasiveness20. ER non-genomic functions occur outside the nucleus, where ER interacts directly or indirectly with growth factor receptors (GFRs) such as IGFR and HER2, and with other signaling molecules, resulting in the activation of downstream signaling pathways such as PI3K/AKT and p42/44 MAPK21,22.

This review will summarize potential key molecular mechanisms underlying altered ER activity in endocrine resistance, focusing on ER crosstalk with other kinase pathways, the potential role of ER co-regulators, and recently identified ER genomic aberrations.

Underlying mechanisms of altered ER activity in endocrine resistance

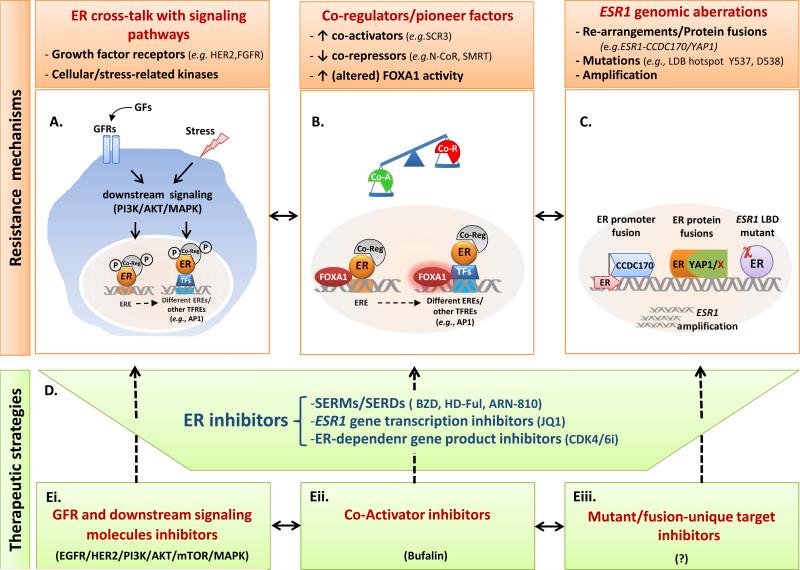

Altered ER activity and downstream signaling found in endocrine-resistant tumors are exemplified by the ligand-independent activity of ER, enhanced agonistic activity in presence of SERMs, decreased sensitivity to SERDs, and activation of differential ER-dependent transcriptional programs. Several mechanisms have been suggested to explain the altered role and activity of ER in the context of endocrine resistance. Below we will discuss three key mechanisms causing altered ER activity (Figure 2A-C).

Figure 2. Endocrine resistance mechanisms and altered ER functions in breast cancer and novel therapeutic strategies.

A. ER cross-talk with signaling pathways: Hyperactive growth factor receptor (GFR) and other cellular/stress-related pathways, via downstream signaling kinases (e.g., PI3K/AKT/MAPK), lead to phosphorylation (P) of ER and its co-regulators and can result in altered ER DNA binding profiles [involving a distinct set of EREs as well as other transcription factor responsive elements (TFREs)], ER transcriptional regulation, and endocrine resistance. B. Co-Regulators/Pioneer factors: Changes in the balance of ER co-regulators (Co-Reg) can occur due to (1) increased levels of co-activator (Co-A; e.g., SRC3) and decreased levels of co-repressor (Co-R, e.g., N-CoR, SMRT), especially in presence of hyper GFR signaling or (2) increased or altered activity of the ER pioneer factor FOXA1. This in turn can enhance or reprogram ER DNA binding and transcriptional activity on different EREs or on other TFREs (e.g., AP1/SP1 sites), reducing sensitivity to endocrine therapies. C. ESR1 genomic aberrations. ESR1 gene re-arrangements with diverse genes (e.g., CCDC170; YAP1; or others (X)), ESR1 amplifications, and ESR1 recurrent point mutations (χ) in the ligand binding domain (LBD) can activate fused oncogenes or generate increased ER levels or constitutively active/ligand-independent ER proteins. D-E. Novel therapeutic strategies inhibiting ER in combination with tailored agents targeting various settings of endocrine resistance. Novel or high dose-SERMs/SERDs, ESR1 gene transcription inhibitors, and inhibitors targeting ER-dependent gene products (D) have been suggested to more potently abolish levels, activity, and signaling of wild type and mutant ERs in endocrine-resistant tumors under various mechanisms illustrated in A-C. In addition, these endocrine drugs may be combined with one or more agents targeting other signaling pathways (Ei), ER co-activators (Eii), or ER mutant/fusion-unique gene products (Eiii) to effectively overcome endocrine resistance. Abbreviations: BZD bazedoxifene; ER, estrogen receptor; EREs, estrogen responsive elements; GFs, growth factors; HD-Ful, high dose-fulvestrant; SERDs, selective estrogen receptor downregulators; SERMs, selective estrogen receptor modulators.

ER crosstalk with receptor tyrosine and other kinases

Clinical and preclinical evidence has revealed extensive mutual interplay between ER and other kinase signaling pathways, leading to amplification or reduction of signaling from each of the associated pathways. Indeed, various growth factor receptors, cellular and stress-related kinases, as well as downstream signaling components, have been shown to bi-directionally crosstalk with the ER pathway (Figure 2A)23,24. Such circuits, which may be already present or arise during the course of treatment, can bypass ER blockade by providing alternative proliferation and survival signals or by regulating ER activity and signaling25. It has long been demonstrated that high levels of HER signaling working via the PI3K and MAPK pathways can reduce ER levels and signaling on one hand, while on the other hand, it can simultaneously activate the pathway by posttranslational modifications (PTMs, e.g., phosphorylation) of ER, its co-regulators, and other components of the cell transcriptional machinery24,26,27. Consequently, tumor estrogen-dependency decreases because the receptor is activated in the absence of estrogen rendering the tumor resistance to estrogen deprivation therapies. Likewise, the inhibitory effects of SERMS on tumor growth and survival are disrupted or weakened25. These effects may also be partly attributed to ER transcriptional reprogramming triggered by hyperactive growth factor receptor signaling. Indeed, studies mapping genome-wide ER-DNA binding sites (i.e.., the ER cistrome) have shown that the epidermal growth factor (EGF)-induced ER cistrome is distinct from the one induced by its ligand estrogen, shifting from sites containing an ERE-motif to those enriched for AP-128. Similarly, as discussed below, reprogramming of ER DNA binding was also reported in preclinical models of endocrine resistance and in clinical tumors associated with hyper growth factor signaling29.

Importantly, signaling of the ER pathway can also activate or inhibit HER and other GFR pathways by direct and indirect mechanisms30. As such, while ER can induce the expression of various GFRs and ligands [e.g., insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF1), its receptor (IGFR), and the HER ligand transforming growth factor-α (TGFα)31,32] or activate these pathways through its non-genomic activity, it can also inhibit the expression of key receptors such as HER1 and HER233,34. Thus, endocrine therapy, by blocking ER genomic activities, can relieve this repression, resulting in increased expression of HER1 and HER2 receptors and downstream signaling34, which in turn can further promote resistance to endocrine therapies.

Additional potential escape pathways from endocrine therapy include those related to the fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 (FGFR1)35, the insulin receptor (IR)36, RON37, and RET38. For example, FGFR1 is amplified in about 10% of breast cancers and more frequently in highly aggressive ER+ breast tumors (luminal B subtype). Breast cancer cells harboring amplification or overexpression of FGFR1 display anchorage-independent proliferation and resistance to endocrine therapies. As would be expected, patients with FGFR1-amplified breast cancer receiving adjuvant tamoxifen have a poor prognosis compared to patients with FGFR1-normal tumors35. Similarly, IR and IGF-1R have been shown to modulate ER function mainly through ER phosphorylation in preclinical models, and gene expression signatures of IGF-pathway activation were associated with poor prognosis in patients with ER+ breast cancers39-41. PI3K/AKT/mTOR and MEK/ERK pathways are common conductors of the diverse tyrosine kinase receptors involved in endocrine resistance42. In addition, the PI3K pathway itself is often dysregulated in human breast cancers due to mutation and/or amplification of the genes encoding its components (PIK3CA, PIK3CB, PIK3R1, AKT1, AKT2) or due to decreased expression of negative regulators of the pathway, such as PTEN and INPP4B43-45. PI3K pathway activation confers resistance to endocrine therapy in ER+ breast cancer cell lines46, and signatures of hyperactive PI3K signaling are associated with reduced ER levels and activity and poor outcome in patients receiving adjuvant endocrine treatment47-49. PI3K pathway inhibitors restore ER levels and can reverse endocrine resistance in preclinical models and patients50 Additional preclinical and clinical studies have also shown that intrinsic and acquired endocrine resistance is associated with increased oxidative stress and the activation of two important stress-related signaling kinases, JNK and p38, as well as increased JNK-dependent AP-1 phosphorylation and activity23,51-53. Interestingly, both p38 and JNK can also be induced by GFR signaling pathways known to be involved in endocrine resistance, such as the HER1/HER2 pathways. Activation of p38 and JNK pathways can lead to increased phosphorylation of ER and/or its important co-activator SRC326, thereby altering ER activity and sensitivity to endocrine agents34. Preclinical studies employing genetic strategies have suggested that inhibition of AP-1 transcriptional activity can alter ER activity and circumvent endocrine resistance28,54.

Co-regulators of ER activity

Upon binding to its ligands, ER changes conformation, exposing interaction surfaces for recruitment of accessory factors also known as co-regulators of the transcription machinery55 (Figure 2B). The expression of these co-regulators is often redundant and ubiquitous and the cellular context is critical for their function56. Depending on the nature of the bound ligand, ER recruits and interacts with proteins that can either enhance (co-activators) or repress (co-repressors) its transcriptional activity57. Interestingly, the level and the activity of these co-regulators can enhance ligand-independent activation of ER or modulate the agonist/antagonist activity of SERMs such as tamoxifen. In breast cancer cells, tamoxifen acts predominantly as an antagonist of ER, blocking its activity and leading to decreased tumor cell growth and survival. In the presence of high co-activator levels, however, tamoxifen can act as an agonist, promoting ER transcriptional activity and allowing cancer cell growth58. Indeed, overexpression of the ER co-activator SRC3 (also known as amplified-in-breast-cancer-1, AIB1) is associated with preclinical and clinical resistance to tamoxifen25,59. High levels of SRC3 resulted in worse outcome in tamoxifen-treated patients, especially when the tumor co-expressed high levels of HER2 or other members of the HER family59,60. Similarly, decreased levels of co-repressors [e.g. nuclear receptor co-repressor (N-CoR) and silencing mediator for retinoid and thyroid hormone receptors (SMRT)] correlate with the acquisition of tamoxifen resistance in preclinical models 61 and in clinical specimens of breast cancer62. As reported above, post-translational modifications, such as phosphorylation, induced by hyperactive GFR signaling have also been reported to modulate co-regulator activity. As such, phosphorylation of SCR3 by different cellular kinases results in enhanced recruitment of other co-regulators resulting in increased ER transcriptional activity, even in presence of tamoxifen26. Similarly, phosphorylation of N-CoR leads to its own exclusion from the nucleus, thereby reducing its inhibitory effects on ER activity62.

In addition to co-regulator proteins like those described above, ER transcriptional activity is also regulated by pioneer factors. Pioneer factors are transcription factors that can directly bind to and open condensed chromatin to assist the binding of other transcription factors, such as ER and other NRs. The pioneer factor FOXA1, a member of the FKHR family of transcription factors (TFs), has been shown in multiple studies to play a key role in ER-chromatin interactions and the gene transcriptional program induced by ER, and it may also have a role in endocrine resistance29,63,64. Indeed, analysis of ER cistromes in endocrine-resistant breast cancer cell lines, as well as in ER+ tumor samples from patients with poor outcomes or metastatic disease, have documented a dynamic process in which a differential ER-binding program, involving ERE, FOXA1, PAX2, and AP-1 motifs, is acquired due to the FOXA1-mediated reprogramming of ER binding. In support of these findings, results of histological staining have revealed that while in primary breast tumors a high level of FOXA1 correlates with good prognosis, it correlates with worse prognosis at the time of resistance29. Our new studies in acquired endocrine-resistant preclinical models suggest that FOXA1 gene amplification or overexpression involves the activation of a unique set of genes which can mediate endocrine resistance65.

ER genomic aberrations and resistance

Recently whole genome sequencing and targeted next-generation sequencing have revealed multiple genomic aberrations at the ER locus, including re-arrangements, point mutations, and gene amplification (Figure 2C).

The ER gene ESR1 has been shown to be re-arranged with its adjacent gene CCDC170, encoding a protein with unknown function. The resulting fusion protein, ER-CCDC170, expresses a truncated form of the CCDC170 protein that is transcribed from the constitutively active promoter of ESR1. ER-CCDC170 is preferentially expressed in the luminal B breast cancer subtype and its ectopic expression in preclinical models shows a gain-of-function activity, with enhancement of motility, tumor formation, and endocrine resistance66. Another recently described partner for fusion with ESR1 is YAP1, found in a patient-derived xenograft (PDX) from an ER+ endocrine-resistant patient. This ER-YAP1 fusion loses the LBD of ER and shows a completely ligand-independent activity of the receptor on classical ERE-dependent genes67. Additional ER partners have also recently been reported68 and remarkably in all the cases the ER promoter is used to direct the transcription of the fused proteins, which consist of different lengths of the N-terminal regions of ER. These resulting fusion proteins mostly enhance ERE-independent transcription activity and endocrine resistance 68.

Single-nucleotide mutations of ESR1 have been reported and usually consist of activating mutations. More than a decade ago the K303R ER mutation, residing in the hinge region, was reported to be present in one third of premalignant lesions and in ~50% of primary invasive breast cancer69. However the frequency and the clinical implication of this mutation are still controversial 70.

Over the past year, a few parallel studies utilizing next-generation sequencing have identified ESR1 gain-of-function recurrent mutations in the LBD of the ER in ~20% of patients with resistant metastatic breast cancers that emerge mostly after endocrine therapy. ER mutations have been described mainly in a “hotspot” of the LBD, where Y537 and D538 are the most mutated residues71. Missense mutations Y537S and D538G confer higher stabilization of the mutant protein in the agonistic conformation, resulting in a ligand-independent activation of ER72,73. Indeed, most of the reported ER mutations confer constitutive ligand-independent activity on the receptor, causing resistance to estrogen-deprivation and reduced sensitivity to tamoxifen and fulvestrant. Interestingly, the allele frequency of the ER mutations increases after more than one line of endocrine therapy is given, suggesting clonal selection of these mutations as a potential driver for resistance74. In addition, recent reports suggest that these ER LBD mutations may promote the expression of a unique set of genes leading to a more aggressive and invasive phenotype. ESR1 amplification has also been described in about 2% of primary and metastatic breast cancers74,75 but its clinical significance is still unclear.

Epigenetic modification, a reversible modification in gene expression without changing the DNA sequence, can also alter ER activity. A growing number of studies are showing the importance of epigenetic alteration, including DNA methylation, histone modifications, and non-coding RNA, in endocrine resistance (reviewed in76,77). For example, DNA methylation can repress ER expression, leading to loss of ER and endocrine resistance78,79. The histone methyl-transferase WHSC1, interacting with the BET protein BRD3/4, has been shown to facilitate ESR1 gene expression and ER signaling. Interestingly, the small molecule BET inhibitor JQ1, already in use for hematological cancer, can potently deplete the classical ER signaling pathway and, in combination with fulvestrant, can more completely abolish ER protein levels in tamoxifen-resistant preclinical models80. These findings highlight a potential therapeutic role for ER epigenetic regulators in dealing with endocrine resistance81.

Clinical implications and new therapeutic strategies

The research efforts to understand the altered ER biology and signaling in endocrine resistance provide additional predictive markers and the rationale for testing novel therapeutic tailored strategies (Figure 2 D, E).

As mentioned above, even in the context of acquired endocrine resistance ER is still expressed and actively contributes to tumor growth, so that its inhibition remains essential. While aromatase inhibitors, SERMs, and SERDs are effective in inhibiting ER+ breast tumor growth, especially in the early-stage disease, a more potent ER blockade may be needed in cases of endocrine-resistant tumors where ER activity is altered due to additional cell signaling or ER genomic aberrations (Figure 2D). High doses of fulvestrant have been shown to be more effective in patients with endocrine-resistant tumors11. This strategy, as well as new generation SERMs and SERDs, such as bazedoxifene82 and ARN-81083, are currently in clinical development, and preclinical studies in tumors harboring ER LBD mutations are promising 67,72-74,84.

Blocking the transcription of the ER gene itself by an epigenetic approach using JQ180 (Figure 2D) or targeting ER co-activators, such as the recently described SRC-3 small molecule inhibitors (e.g., bufalin)85,86 (Figure 2Eii) are additional innovative and fascinating strategies to more potently abolish ER expression and signaling. In addition, ER gene products such as cyclin D1 may represent suitable therapeutic targets for improving endocrine sensitivity, as proven by recent results from clinical trials of the CDK4/6 inhibitor palbociclib, in advanced breast cancers87. Furthermore, genomic insights into ER reprogramming and its acting regulators, such as AP-128,54 and FOXA129,63,65, in endocrine-resistant tumors may not only point to the therapeutic role of these regulators, but also reveal additional key downstream candidate genes for development of predictive biomarkers as well as novel targets to circumvent endocrine resistance.

The proof of an extensive and bidirectional crosstalk between ER and HER2 signaling has suggested that simultaneous inhibition of these two pathways is necessary in patients with ER+/HER2+ breast tumors25,88,89 (Figure 2Ei). Similarly, the efficacy and safety of targeting other relevant growth factor receptor-related pathways, (i.e. FGFR) in addition to endocrine treatment is currently under clinical evaluation. Moreover, pharmacological inhibition of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway in addition to endocrine therapy has proved to be clinically relevant in patients with ER+/HER2-negative endocrine-resistant breast cancer50,90,91. However, since many ‘escape’ signaling pathways are involved in resistance and may even co-exist and/or co-operate, simultaneously inhibiting multiple pathways or identifying and inhibiting a converging downstream regulator/mediator, such as AP-154 may be a more successful strategy to overcome endocrine resistance. Finally, the multiplicity and heterogeneity of the molecular mechanisms sustaining endocrine resistance and their evolution over the course of the disease highlight the desirability of routine biopsy of recurrent lesions to assess the changes in epi/genomics and signaling landscape for tailoring therapies to effectively overcome endocrine resistance. Because sequential tumor biopsies from metastatic sites are challenging, the implementation of alternative and more feasible approaches such as liquid biopsy (e.g. assessment of circulating tumor cells or cell-free DNA from blood samples) is strongly needed. Future tailored clinical trials are warranted to test the efficacy and safety of new ER antagonists alone (Figure 2D) or in combination with agents targeting relevant signaling pathways up- or downstream of the ER axis (Figure 2Ei-iii).

Acknowledgements

This manuscript was partly supported by the Susan G. Komen for the Cure: Promise Grant PG12221410 (to R.S. and C.K.O.); the Breast Cancer Research Foundation; the NIH: SPORE Grants P50 CA058183 and CA186784-01, and Cancer Center Grant P30 CA125123; and the Cancer Prevention & Research Institute of Texas: CPRIT RP 140102, and Baylor College of Medicine Comprehensive Cancer Training Program (to C.D.)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest statement

R. Schiff and C.K. Osborne have received research funding from AstraZeneca and GlaxoSmithKline. C.K. Osborne is a member of advisory boards for Pfizer, Nanostring, Genentech, and AstraZeneca.

References

- 1.Clark GM, Osborne CK, McGuire WL. Correlations between estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, and patient characteristics in human breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1984;2:1102–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1984.2.10.1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Perou CM, Sorlie T, Eisen MB, et al. Molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature. 2000;406:747–52. doi: 10.1038/35021093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Curtis C, Shah SP, Chin SF, et al. The genomic and transcriptomic architecture of 2,000 breast tumours reveals novel subgroups. Nature. 2012;486:346–52. doi: 10.1038/nature10983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prat A, Parker JS, Karginova O, et al. Phenotypic and molecular characterization of the claudin-low intrinsic subtype of breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2010;12:R68. doi: 10.1186/bcr2635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weatherman RV, Fletterick RJ, Scanlan TS. Nuclear-receptor ligands and ligand-binding domains. Annu Rev Biochem. 1999;68:559–81. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.68.1.559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Early Breast Cancer Trialists' Collaborative G. Davies C, Godwin J, et al. Relevance of breast cancer hormone receptors and other factors to the efficacy of adjuvant tamoxifen: patient-level meta-analysis of randomised trials. Lancet. 2011;378:771–84. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60993-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cole MP, Jones CT, Todd ID. A new anti-oestrogenic agent in late breast cancer. An early clinical appraisal of ICI46474. Br J Cancer. 1971;25:270–5. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1971.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Francis PA, Regan MM, Fleming GF, et al. Adjuvant ovarian suppression in premenopausal breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:436–46. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1412379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pagani O, Regan MM, Walley BA, et al. Adjuvant exemestane with ovarian suppression in premenopausal breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:107–18. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1404037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Strasser-Weippl K, Badovinac-Crnjevic T, Fan L, et al. Extended adjuvant endocrine therapy in hormone-receptor positive breast cancer. Breast. 2013;22(Suppl 2):S171–5. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2013.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Robertson JF, Lindemann J, Garnett S, et al. A good drug made better: the fulvestrant dose-response story. Clin Breast Cancer. 2014;14:381–9. doi: 10.1016/j.clbc.2014.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ring A, Dowsett M. Mechanisms of tamoxifen resistance. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2004;11:643–58. doi: 10.1677/erc.1.00776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yao ZX, Lu LJ, Wang RJ, et al. Discordance and clinical significance of ER, PR, and HER2 status between primary breast cancer and synchronous axillary lymph node metastasis. Med Oncol. 2014;31:798. doi: 10.1007/s12032-013-0798-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoefnagel LD, Moelans CB, Meijer SL, et al. Prognostic value of estrogen receptor alpha and progesterone receptor conversion in distant breast cancer metastases. Cancer. 2012;118:4929–35. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dodwell D, Wardley A, Johnston S. Postmenopausal advanced breast cancer: options for therapy after tamoxifen and aromatase inhibitors. Breast. 2006;15:584–94. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2006.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morrison G, Fu X, Shea M, et al. Therapeutic potential of the dual EGFR/HER2 inhibitor AZD8931 in circumventing endocrine resistance. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2014;144:263–72. doi: 10.1007/s10549-014-2878-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Osborne CK, Coronado-Heinsohn EB, Hilsenbeck SG, et al. Comparison of the effects of a pure steroidal antiestrogen with those of tamoxifen in a model of human breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1995;87:746–50. doi: 10.1093/jnci/87.10.746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tora L, White J, Brou C, et al. The human estrogen receptor has two independent nonacidic transcriptional activation functions. Cell. 1989;59:477–87. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90031-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schiff ROCFS. Diseases of the Breast. (Edition 4) 2009:408–430. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Osborne CK, Schiff R, Fuqua SA, et al. Estrogen receptor: current understanding of its activation and modulation. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:4338s–4342s. discussion 4411s-4412s. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nemere I, Pietras RJ, Blackmore PF. Membrane receptors for steroid hormones: signal transduction and physiological significance. J Cell Biochem. 2003;88:438–45. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Levin ER. Extranuclear steroid receptors are essential for steroid hormone actions. Annu Rev Med. 2015;66:271–80. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-050913-021703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnston SR, Lu B, Scott GK, et al. Increased activator protein-1 DNA binding and c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase activity in human breast tumors with acquired tamoxifen resistance. Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5:251–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Giuliano M, Trivedi MV, Schiff R. Bidirectional Crosstalk between the Estrogen Receptor and Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2 Signaling Pathways in Breast Cancer: Molecular Basis and Clinical Implications. Breast Care (Basel) 2013;8:256–62. doi: 10.1159/000354253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shou J, Massarweh S, Osborne CK, et al. Mechanisms of tamoxifen resistance: increased estrogen receptor-HER2/neu cross-talk in ER/HER2-positive breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96:926–35. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wu RC, Qin J, Yi P, et al. Selective phosphorylations of the SRC-3/AIB1 coactivator integrate genomic reponses to multiple cellular signaling pathways. Mol Cell. 2004;15:937–49. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Font de Mora J, Brown M. AIB1 is a conduit for kinase-mediated growth factor signaling to the estrogen receptor. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:5041–7. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.14.5041-5047.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lupien M, Meyer CA, Bailey ST, et al. Growth factor stimulation induces a distinct ER(alpha) cistrome underlying breast cancer endocrine resistance. Genes Dev. 2010;24:2219–27. doi: 10.1101/gad.1944810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ross-Innes CS, Stark R, Teschendorff AE, et al. Differential oestrogen receptor binding is associated with clinical outcome in breast cancer. Nature. 2012;481:389–93. doi: 10.1038/nature10730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schiff R, Massarweh SA, Shou J, et al. Advanced concepts in estrogen receptor biology and breast cancer endocrine resistance: implicated role of growth factor signaling and estrogen receptor coregulators. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2005;56(Suppl 1):10–20. doi: 10.1007/s00280-005-0108-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee AV, Cui X, Oesterreich S. Cross-talk among estrogen receptor, epidermal growth factor, and insulin-like growth factor signaling in breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:4429s–4435s. discussion 4411s-4412s. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Umayahara Y, Kawamori R, Watada H, et al. Estrogen regulation of the insulin-like growth factor I gene transcription involves an AP-1 enhancer. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:16433–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bailey ST, Westerling T, Brown M. Loss of estrogen-regulated microRNA expression increases HER2 signaling and is prognostic of poor outcome in luminal breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2015;75:436–45. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-1041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Osborne CK, Schiff R. Mechanisms of endocrine resistance in breast cancer. Annu Rev Med. 2011;62:233–47. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-070909-182917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Turner N, Pearson A, Sharpe R, et al. FGFR1 amplification drives endocrine therapy resistance and is a therapeutic target in breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2010;70:2085–94. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yee D. Targeting the insulin-like growth factor receptor. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol. 2009;7:452–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McClaine RJ, Marshall AM, Wagh PK, et al. Ron receptor tyrosine kinase activation confers resistance to tamoxifen in breast cancer cell lines. Neoplasia. 2010;12:650–8. doi: 10.1593/neo.10476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gattelli A, Nalvarte I, Boulay A, et al. Ret inhibition decreases growth and metastatic potential of estrogen receptor positive breast cancer cells. EMBO Mol Med. 2013;5:1335–50. doi: 10.1002/emmm.201302625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fox EM, Miller TW, Balko JM, et al. A kinome-wide screen identifies the insulin/IGF-I receptor pathway as a mechanism of escape from hormone dependence in breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2011;71:6773–84. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-1295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Becker MA, Ibrahim YH, Cui X, et al. The IGF pathway regulates ERalpha through a S6K1-dependent mechanism in breast cancer cells. Mol Endocrinol. 2011;25:516–28. doi: 10.1210/me.2010-0373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Creighton CJ, Casa A, Lazard Z, et al. Insulin-like growth factor-I activates gene transcription programs strongly associated with poor breast cancer prognosis. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:4078–85. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.4429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hennessy BT, Smith DL, Ram PT, et al. Exploiting the PI3K/AKT pathway for cancer drug discovery. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2005;4:988–1004. doi: 10.1038/nrd1902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ellis MJ, Lin L, Crowder R, et al. Phosphatidyl-inositol-3-kinase alpha catalytic subunit mutation and response to neoadjuvant endocrine therapy for estrogen receptor positive breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;119:379–90. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0575-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stemke-Hale K, Gonzalez-Angulo AM, Lluch A, et al. An integrative genomic and proteomic analysis of PIK3CA, PTEN, and AKT mutations in breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2008;68:6084–91. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fu X, Creighton CJ, Biswal NC, et al. Overcoming endocrine resistance due to reduced PTEN levels in estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer by co-targeting mammalian target of rapamycin, protein kinase B, or mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase. Breast Cancer Res. 2014;16:430. doi: 10.1186/s13058-014-0430-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Miller TW, Hennessy BT, Gonzalez-Angulo AM, et al. Hyperactivation of phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase promotes escape from hormone dependence in estrogen receptor-positive human breast cancer. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:2406–13. doi: 10.1172/JCI41680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Creighton CJ. A gene transcription signature of the Akt/mTOR pathway in clinical breast tumors. Oncogene. 2007;26:4648–55. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Creighton CJ, Fu X, Hennessy BT, et al. Proteomic and transcriptomic profiling reveals a link between the PI3K pathway and lower estrogen-receptor (ER) levels and activity in ER+ breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2010;12:R40. doi: 10.1186/bcr2594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Miller TW, Perez-Torres M, Narasanna A, et al. Loss of Phosphatase and Tensin homologue deleted on chromosome 10 engages ErbB3 and insulin-like growth factor-I receptor signaling to promote antiestrogen resistance in breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2009;69:4192–201. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Baselga J, Campone M, Piccart M, et al. Everolimus in postmenopausal hormone-receptor-positive advanced breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:520–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1109653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schiff R, Reddy P, Ahotupa M, et al. Oxidative stress and AP-1 activity in tamoxifen-resistant breast tumors in vivo. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:1926–34. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.23.1926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gutierrez MC, Detre S, Johnston S, et al. Molecular changes in tamoxifen-resistant breast cancer: relationship between estrogen receptor, HER-2, and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:2469–76. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhou Y, Yau C, Gray JW, et al. Enhanced NF kappa B and AP-1 transcriptional activity associated with antiestrogen resistant breast cancer. BMC Cancer. 2007;7:59. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-7-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Malorni LGM, Migliaccio I, Wang T, Creighton CJ, Lupien M, Hilsenbeck SG, Healy N, Mazumdar A, Trivedi MV, Jeselsohn R, He HH, Fu X, Gutierrez C, Brown M, Brown PH, Osborne CK, Schiff R. AP-1 Blockade Potentiates the Anti-Tumor Effect of Endocrine Treatment and Reverts the Resistant Phenotype in Hormone Receptor-Positive Breast Cancer.. 34th San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium; San Antonio, Texas, USA. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bulynko YA, O'Malley BW. Nuclear receptor coactivators: structural and functional biochemistry. Biochemistry. 2011;50:313–28. doi: 10.1021/bi101762x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Clarke R, Leonessa F, Welch JN, et al. Cellular and molecular pharmacology of antiestrogen action and resistance. Pharmacol Rev. 2001;53:25–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schiff R, Massarweh S, Shou J, et al. Breast cancer endocrine resistance: how growth factor signaling and estrogen receptor coregulators modulate response. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:447S–54S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Smith CL, Nawaz Z, O'Malley BW. Coactivator and corepressor regulation of the agonist/antagonist activity of the mixed antiestrogen, 4-hydroxytamoxifen. Mol Endocrinol. 1997;11:657–66. doi: 10.1210/mend.11.6.0009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Osborne CK, Bardou V, Hopp TA, et al. Role of the estrogen receptor coactivator AIB1 (SRC-3) and HER-2/neu in tamoxifen resistance in breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95:353–61. doi: 10.1093/jnci/95.5.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kirkegaard T, McGlynn LM, Campbell FM, et al. Amplified in breast cancer 1 in human epidermal growth factor receptor - positive tumors of tamoxifen-treated breast cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:1405–11. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Keeton EK, Brown M. Cell cycle progression stimulated by tamoxifen-bound estrogen receptor-alpha and promoter-specific effects in breast cancer cells deficient in N-CoR and SMRT. Mol Endocrinol. 2005;19:1543–54. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lavinsky RM, Jepsen K, Heinzel T, et al. Diverse signaling pathways modulate nuclear receptor recruitment of N-CoR and SMRT complexes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:2920–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.6.2920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Carroll JS, Meyer CA, Song J, et al. Genome-wide analysis of estrogen receptor binding sites. Nat Genet. 2006;38:1289–97. doi: 10.1038/ng1901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Robinson JL, Carroll JS. FoxA1 is a key mediator of hormonal response in breast and prostate cancer. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2012;3:68. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2012.00068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fu XJR, Hollingsworth EF, Lopez-Terrada D, Creighton CJ, Nardone A, Shea MJ, Heiser LM, Anur P, Wang N, Grasso C, Spellman P, Gutierrez C, Rimawi MF, Hilsenbeck SG, Gray JW, Brown M, Osborne CK, Schiff R. FoxA1 gene amplification in ER+ breast cancer mediates endocrine resistance by increasing IL-8. 37th San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium; San Antonio, Texas, USA. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Veeraraghavan J, Tan Y, Cao XX, et al. Recurrent ESR1-CCDC170 rearrangements in an aggressive subset of oestrogen receptor-positive breast cancers. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4577. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Li S, Shen D, Shao J, et al. Endocrine-therapy-resistant ESR1 variants revealed by genomic characterization of breast-cancer-derived xenografts. Cell Rep. 2013;4:1116–30. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.08.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Jieya Shao JZ, Crowder Robert J, Goncalves Rodrigo, Phommaly Chanpheng, Breast AWG, Network Charles M, Perou CAM, Aubrey Thompson E, Ellis Matthew J. ESR1 gene fusions implicated in endocrine therapy resistance of ER+ breast cancer. 37th San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium; San Antonio, Texas, USA. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Fuqua SA, Wiltschke C, Zhang QX, et al. A hypersensitive estrogen receptor-alpha mutation in premalignant breast lesions. Cancer Res. 2000;60:4026–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fuqua SA, Gu G, Rechoum Y. Estrogen receptor (ER) alpha mutations in breast cancer: hidden in plain sight. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2014;144:11–9. doi: 10.1007/s10549-014-2847-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Alluri PGSC, Chinnaiyan AM. Estrogen receptor mutations and their role in breast cancer progression. Breast Cancer Research. 16:2014. doi: 10.1186/s13058-014-0494-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Toy W, Shen Y, Won H, et al. ESR1 ligand-binding domain mutations in hormone-resistant breast cancer. Nat Genet. 2013;45:1439–45. doi: 10.1038/ng.2822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Robinson DR, Wu YM, Vats P, et al. Activating ESR1 mutations in hormone-resistant metastatic breast cancer. Nat Genet. 2013;45:1446–51. doi: 10.1038/ng.2823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Jeselsohn R, Yelensky R, Buchwalter G, et al. Emergence of constitutively active estrogen receptor-alpha mutations in pretreated advanced estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:1757–67. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-2332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Cancer Genome Atlas N Comprehensive molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature. 2012;490:61–70. doi: 10.1038/nature11412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Abdel-Hafiz HA, Horwitz KB. Role of epigenetic modifications in luminal breast cancer. Epigenomics. 1-16:2015. doi: 10.2217/epi.15.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Pathiraja TN, Stearns V, Oesterreich S. Epigenetic regulation in estrogen receptor positive breast cancer--role in treatment response. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2010;15:35–47. doi: 10.1007/s10911-010-9166-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Parrella P, Poeta ML, Gallo AP, et al. Nonrandom distribution of aberrant promoter methylation of cancer-related genes in sporadic breast tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:5349–54. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lapidus RG, Nass SJ, Davidson NE. The loss of estrogen and progesterone receptor gene expression in human breast cancer. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 1998;3:85–94. doi: 10.1023/a:1018778403001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Feng Q, Zhang Z, Shea MJ, et al. An epigenomic approach to therapy for tamoxifen-resistant breast cancer. Cell Res. 2014;24:809–19. doi: 10.1038/cr.2014.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Alluri PG, Asangani IA, Chinnaiyan AM. BETs abet Tam-R in ER-positive breast cancer. Cell Res. 2014;24:899–900. doi: 10.1038/cr.2014.90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Pinkerton JV, Thomas S. Use of SERMs for treatment in postmenopausal women. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2014;142:142–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2013.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Mayer IABA, Dickler MN, Manning HC, Mahmood U, Ulaner GA, Hager JH, Rix P, Zack N, Maneval EC, Chen I, Baselga J, Arteaga CL. Phase I study of ARN-810, a novel selective estrogen receptor degrader, in post-menopausal women with locally advanced or metastatic estrogen receptor positive breast cancer. 36th San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium; San Antonio, Texas, USA. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Merenbakh-Lamin K, Ben-Baruch N, Yeheskel A, et al. D538G mutation in estrogen receptor-alpha: A novel mechanism for acquired endocrine resistance in breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2013;73:6856–64. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Yan F, Yu Y, Chow DC, et al. Identification of verrucarin a as a potent and selective steroid receptor coactivator-3 small molecule inhibitor. PLoS One. 2014;9:e95243. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0095243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wang Y, Lonard DM, Yu Y, et al. Bufalin is a potent small-molecule inhibitor of the steroid receptor coactivators SRC-3 and SRC-1. Cancer Res. 2014;74:1506–17. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-2939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Finn RS, Crown JP, Lang I, et al. The cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 inhibitor palbociclib in combination with letrozole versus letrozole alone as first-line treatment of oestrogen receptor-positive, HER2-negative, advanced breast cancer (PALOMA-1/TRIO-18): a randomised phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:25–35. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)71159-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kaufman B, Mackey JR, Clemens MR, et al. Trastuzumab plus anastrozole versus anastrozole alone for the treatment of postmenopausal women with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive, hormone receptor-positive metastatic breast cancer: results from the randomized phase III TAnDEM study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5529–37. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.6847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Johnston S, Pippen J, Jr., Pivot X, et al. Lapatinib combined with letrozole versus letrozole and placebo as first-line therapy for postmenopausal hormone receptor-positive metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5538–46. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.3734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Bachelot T, Bourgier C, Cropet C, et al. Randomized phase II trial of everolimus in combination with tamoxifen in patients with hormone receptor-positive, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-negative metastatic breast cancer with prior exposure to aromatase inhibitors: a GINECO study. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:2718–24. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.0708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Fox EM, Arteaga CL, Miller TW. Abrogating endocrine resistance by targeting ERalpha and PI3K in breast cancer. Front Oncol. 2012;2:145. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2012.00145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]