Abstract

Colonic drug delivery is intended not only for local treatment in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) but also for systemic delivery of therapeutics. Intestinal myeloperoxidase (MPO) determination could be used to estimate the average level of inflammation in colon as well as to determine the efficacy of drugs to be used in the treatment of inflammatory bowel diseases or study the specificity of dosage forms to be used for colonic targeting of anti-inflammatory drugs. Colonic prodrug sulfasalazine (SASP) gets metabolized to give 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA), which is the active portion of SASP. However, when given orally, 5-ASA is absorbed in upper part of gastrointestinal tract (GIT) and not made available in colon. In the present study, colon-targeted delivery of 5-ASA was achieved by formulating tablets with two natural polymers namely guar gum and pectin using compression coating method. Colonic specificity of 5-ASA tablets (prepared using guar gum and pectin as polymers) was evaluated in vitro using simulated fluids mimicking in vivo environment as well as in vivo method using chemically (2,4,6-trinitrobenzenesulfonic acid and acetic acid)-induced colitis rat model. Both colon-specific formulations of 5-ASA (guar gum and pectin) were observed to be more effective in reducing inflammation in chemically induced colitis rat models when compared to colon-specific prodrug sulfasalazine as well as conventional 5-ASA administered orally.

KEY WORDS: colitis, colon-specific drug delivery, myeloperoxidase

INTRODUCTION

Targeted drug delivery system to colonic region of gastrointestinal tract (GIT) has been explored extensively in the last two decades not only for local treatment of colon diseases such as colon cancer and inflammatory bowel diseases (ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease) but also for systemic delivery of peptides and proteins (1). It has been demonstrated that insulin, vasopressin, and calcitonin can be absorbed in the colonic region (1,2). Colon is the preferred site for delivery of therapeutics due to low level of enzyme activity, nearly neutral pH, and long transit time (2–4). Designing of the oral formulation intended for colon-specific drug targeting is a challenging task, as it requires that the incorporated drug should exclusively release in the colon without chemical or enzymatic degradation in upper GIT (stomach and small intestine).

Different strategies based on employing various physiological parameters such as pH, enzyme activity, microbial flora, GI transit time, and pressure (5–7) have been attempted to design the formulation for colon-specific delivery. Natural biodegradable polymers have been extensively used for developing solid oral dosage forms designed for colon-specific delivery of therapeutics (8,9). Guar gum and pectin are linear polysaccharides used preferably for colon drug delivery formulations (10–12). These linear polysaccharides remain intact in the upper GIT and are degraded by the microbial flora of colon. This attribute makes these polymers as preferable carriers for site-specific delivery.

Investigation of sulfasalazine metabolism suggests that 5-aminosalicylic (5-ASA) acid is the therapeutically active portion of the drug (13,14) in inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD). However, it has been reported that 5-ASA is extensively absorbed and metabolized in the upper gastrointestinal tract by first pass metabolism and is not made available to the desired site, i.e., colon (15). To improve the site availability of the drug, several approaches have been utilized (16,17).

Intestinal inflammation either in human inflammatory disease or induced colitis in experimental animal model is usually a patchy and inhomogeneous process. Myeloperoxidase (MPO) is a specific marker for neutrophils (18–20). It is released extracellularly after neutrophil activation in vitro or in vivo. Extracellular MPO is an index of neutrophil activation in a variety of clinical conditions including inflammatory bowel disease, rheumatoid arthritis, and acute respiratory distress.

MPO determination could be used to estimate the average level of inflammation in colon using either surgical or biopsy specimens. This technique is more useful for evaluating efficacy of drugs as well as site-specific dosage forms in animal models of inflammation (21,22).

In the present study, we have prepared colon-specific 5-ASA tablets with polymers guar gum and pectin using formulation approach of compression coating. In vitro release profiles confirmed the concept of “site-specific colonic tablet.” However, the results of in vitro tests had to be confirmed by the in vivo study that would provide the “proof of concept.” The aim of the present study was to compare the pharmacodynamic effect of the developed colon-specific tablets of 5-ASA [formulated using guar gum (GC1) and pectin (PC1)] with colon-specific prodrug of 5-ASA, viz. sulfasalazine and standard 5-ASA given orally with respect to the anti-inflammatory effect in experimentally induced colitis model.

We observed site-specific release of drug and alleviation of inflammatory bowel syndrome as assessed by MPO activity measurement and histological examination in experimental colitis model, and the formulations were found to be comparable to the colon-specific drug sulfasalazine and more effective than conventional 5-ASA.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Formulation for Colon-Specific Delivery

For Human Use

Compression coated tablets with guar gum ULV 1000 (GC1; Indian Gums Ltd., India) and pectin (degree of methoxylation 9%; PC1) (Enzochem Pvt. Ltd., India) containing 250 mg of 5-ASA (Sun Pharmaceuticals Ltd., India) were formulated for the experiment. Drug core tablet granules containing 5-ASA were prepared along with excipients, like Avicel PH 102 (FMC Biopolymer) and hydroxypropyl methylcellulose E5 (Dow Chemicals Ltd., India). The granules were mixed with talc and finally lubricated with magnesium stearate (Table I). The tablets were compressed using biconvex punches.

Table I.

Formulation of Colon-Specific Tablet for Human Consumption

| Guar gum formulation | Pectin formulation | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Core tablet | |||

| Ingredients | (mg) | Ingredients | (mg) |

| Drug (5-ASA) | 250 | Drug (5-ASA) | 250 |

| Avicel PH 102 | 22 | Avicel PH 102 | 22 |

| HPMC E5 | 22 | HPMC E5 | 22 |

| Magnesium stearate | 3 | Magnesium stearate | 3 |

| Talc | 1.5 | Talc | 1.5 |

| Weight of core tablet | 300 | Weight of core tablet | 300 |

| Polymer coat | |||

| Guar gum | 250 | Pectin | 250 |

| Avicel PH 102 | 120 | Avicel PH 102 | 120 |

| HPMC E5 | 24 | HPMC E5 | 24 |

| Magnesium stearate | 4 | Magnesium stearate | 4 |

| Talc | 2 | Talc | 2 |

| Weight of polymer coat | 400 | Weight of polymer coat | 400 |

| Total tablet weight | 700 | Total tablet weight | 700 |

| Drug/polymer ratio | 1:1 | Drug/polymer ratio | 1:1 |

| Polymer (%) | 36 | Polymer (%) | 36 |

| Enteric coat | |||

| (Tabcoat TC W22 (Et) containing HPMCP | 56 | ||

| Total tablet weight | 700 | Total tablet weight with enteric coat | 756 |

HPMCP hypromellose phthalate, HPMC hydroxypropyl methylcellulose, 5-ASA 5-aminosalicylic acid

For compression coating, guar gum granules comprising of guar gum ULV 1000 (250 mg/tablet; Indian Gums Ltd. India) Avicel PH 102 (FMC Biopolymer) and hydroxypropyl methylcellulose E5 (Dow Chemicals Ltd., India) were prepared, mixed with talc, and lubricated with magnesium stearate. The compression coat was applied over the core tablet as depicted in Fig. 1a and Table I.

Fig. 1.

Profile overview of colon-specific tablets of 5-ASA formulated with polymer guar gum and pectin and in vitro drug release of the formulations. a Schematic diagram of colon-specific tablet using compression coating method with guar gum. b Schematic diagram of colon-specific tablet using compression coating method with pectin. c The thermograph of 5-ASA as a pure drug (i), formulations containing guar gum (ii) and formulation based on pectin (iii) showed single peak of drug (5-ASA) depicting compatibility of drug and added excipients. d The colon-specific formulations of 5-ASA prepared with guar gum (black circle) and pectin (black square) were analyzed for drug release with in-house developed method using second-order derivative spectrophotometer. The cumulative drug released was estimated at different time points beginning at 1 h till 24 h (n = 4)

For pectin-based tablets, drug core tablets used were similar as that of guar gum tablets. Compression coating granules of pectin (with low degree of methoxylation) comprising of 250 mg pectin/tablet were prepared along with Avicel PH 102 (FMC Biopolymer) and hydroxypropyl methylcellulose E5 (Dow Chemicals Ltd.), mixed with talc, and lubricated with magnesium stearate. Similarly, the compression coat was applied over the core tablet as depicted in Fig. 1b and Table I.

In case of formulation with pectin, additional enteric coat was applied over the tablets. The enteric coat comprising of hydroxypropyl methylcellulose phthalate [(Tabcoat TC W22 (Et) as powder mixture—Pharmaceutical Coatings Pvt. Ltd., India] was applied over the pectin compression coated tablets to obtain the weight gain of 8% as shown in Fig. 1b and Table I.

For Experimental Colitis Model in Animal

Compression coated tablets with guar gum ULV 1000 (GC1; Indian Gums Ltd., India) and pectin (degree of methoxylation 9%) (PC1; Enzochem Pvt. Ltd., India) containing 50 mg of 5-ASA (Sun Pharmaceuticals Ltd., India) were formulated for the experiment. Drug core tablet granules containing 5-ASA were prepared along with excipients, like Avicel PH 102 (FMC Biopolymer) and hydroxypropyl methylcellulose E5 (Dow Chemicals Ltd., India). The granules were mixed with talc and finally lubricated with magnesium stearate. The tablets were compressed using biconvex punches.

For compression coating, guar gum granules comprising of guar gum ULV 1000 (50 mg/tablet; Indian Gums Ltd. India) Avicel PH 102 (FMC Biopolymer) and hydroxypropyl methyl cellulose E5 (Dow Chemicals Ltd., India) were prepared, mixed with talc, and lubricated with magnesium stearate. The compression coat was applied over the core tablet as depicted in Fig. 1a.

For pectin-based tablets, drug core tablets used were similar as that of guar gum tablets. Compression coating granules of pectin (with low degree of methoxylation) comprising of 50 mg pectin /tablet were prepared along with Avicel PH 102 (FMC Biopolymer) and hydroxypropyl methylcellulose E5 (Dow Chemicals Ltd.), mixed with talc, and lubricated with magnesium stearate. Similarly, the compression coat was applied over the core tablet as depicted in Fig. 1b.

In case of formulation with pectin, additional enteric coat was applied over the tablets. The enteric coat comprising of hydroxypropyl methylcellulose phthalate [(Tabcoat TC W22 (Et) as powder mixture—Pharmaceutical Coatings Pvt. Ltd., India] was applied over the pectin compression coated tablets to obtain the weight gain of 8% as shown in Fig. 1b.

The core tablets containing 50 mg of 5-ASA were prepared. The weight of core tablets was 65 mg and diameter 7 mm. Polymer coat (guar gum or pectin) granules = 65 mg were compressed over the core tablets to yield compression coated tablets of diameter 9 mm. The excipients and their proportions used were just the same as that present in the formulation applicable for human consumption, i.e., the ratio of drug/polymer was maintained as 1:1. The size of the tablet was reduced so as to enable us to insert the tablet in the cecum. Average thickness of core tablets (n = 10) was 0.78 mm, and average thickness of coated tablets either with GC1 or PC1 (n = 10) was 1.35 mm as shown in Table II.

Table II.

Formulation Parameters for Experimental Colitis Model

| Formulation parameters | |

|---|---|

| Drug (5-ASA) | 50 mg |

| Weight of core tablet | 65 mg |

| Diameter of core tablet | 7 mm |

| Guar gum/pectin | 50 mg |

| Weight of polymer coat | 65 mg |

| Drug/polymer ratio | 1:1 |

| Diameter of compression coated tablet | 9 mm |

5-ASA 5-aminosalicylic acid

The differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) was used to assess the compatibility of the drug with the added excipients and polymers of the formulations. DSC thermographs were taken using Shimadzu DSC-41 equipment under nitrogen atmosphere. The graphs were reported at the temperature between 30°C and 300°C at the rate of 10°C min for the pure drug and formulations containing guar gum and pectin.

Guar gum and pectin being natural polymers were characterized by gel permeation chromatography. By gel permeation chromatography (GPC), molecular weight of these two polymers was determined. The gelling ability of the polymers depends on the viscosity. The viscosity in turn depends on the molecular weight. For GPC, refractive index (RI) detector was used. Prior to GPC, the polymers were standardized as per the compendial standards and characterized by rheology. In case of pectin, degree of methoxylation was determined.

In Vitro Dissolution Study

Colonic specificity of the two formulations was evaluated using in-house developed method. The dissolution studies were performed in simulated gastric fluid for 2 h followed by simulated small intestinal fluid for 4 h and simulated colonic fluid comprising of colonic microflora for 18 h to mimic in vivo environment. The released drug was analyzed by second-order derivative spectrophotometry at 333 nm.

Animals

Adult albino rats weighing 200–250 g of either sex were purchased from Haffkine Research Institute, Mumbai, India. All experiments were performed according to the institutional guidelines that comply with national and international regulations. The rats were fed with standard food pellets with ad libitum food and water access, controlled temperature, and lighting (12-h light–dark cycles). The animals were divided into seven groups (four to five animals per group) such as group I (untreated; colitis-induced), group II (colitis-induced and treated with pectin tablets; tablet instilled in cecum), group III (colitis-induced and treated with guar gum tablets; tablet instilled in cecum), group IV (colitis-induced and treated with standard 5-ASA given per orally), group V (colitis-induced and treated with standard sulfasalazine (SASP) given per orally), group VI (sham; colitis-induced and subjected to cecal ligation without insertion of tablets), and group VII (normal; colitis not induced).

Experimental Design and Scheme

Induction of Colitis

Colonic inflammatory lesions were induced (23–26) in rats by instilling 2,4,6,-trinitrobenzenesulfonic acid (2,4,6-TNBS; Sigma-Aldrich, India) (5% solution in ethanol) at the dose of 20 mg/rat or acetic acid (Qualigens, India; 5% solution in saline) (at the dose of 0.5 ml/rat) instilled into the colon via the anus using the rectal needle under mild anesthesia (ketamine (Neon Laboratories, India) (23 mg/kg injected intraperitoneally). Before inducing colitis, the animals were fasted for 12 h. The animals were allowed water ad libitum during the fasting period. Colitis was induced in groups I to VI. During rectal injection, the inducing agent was injected slowly, and needle was held in position for 10 s so as to ensure that agent has been injected properly.

After rectal instillation of colitis, the animals were placed in cages and allowed to recover from anesthesia. The animals were then provided food and water ad libitum. The animals were observed daily, and presence of colitis was marked by the occurrence of watery stools exuded by the animals. Four days after intracolonic administration, the animals of groups II to V were subjected to the treatment.

TREATMENT

Dose Calculation

The oral dose of 5-ASA (molecular weight (M.W.) = 153.14) for human is 250–400 mg/3–4 times daily. 5-ASA is the therapeutically active moiety of sulfasalazine, SASP (M.W. = 398.164).

For rats weighing 200–250 g (27),

Dose regimen is twice daily; therefore, dose of 5-ASA/rat/day = 9 mg and treatment schedule was 6 days. So, dose per rat was 9 × 6 = 54 mg. The dose for rats = 50 mg divided for 6 days.

The dose is as mentioned earlier. Groups II and III were subjected to treatment of 5-ASA using colon-specific tablets GC1 and PC1. Because of the size of the animals, oral administration of non-disintegrating solid dosage form is difficult. Therefore, the tablets had to be surgically inserted directly into the region of interest, i.e., cecum instead of per oral administration. The tablets were instilled by performing cecal ligation under aseptic condition. Briefly, the rats were not fed 12 h prior to the procedure. During the fasting period, the animals were provided with water ad libitum. The abdominal skin was gently shaved after securing the rat to a dissection board. After cleaning and shaving the abdominal skin, the peritoneal cavity was opened by a small right lateral incision under ketamine (Neon Laboratories) anesthesia (100 mg/kg intraperitoneally). The cecum was identified on the right side and delivered out of the abdominal cavity. The tablet was inserted in the cecum by making a small incision. The tablet was secured in position by simultaneously inserting a small piece of sterile gelatin sponge (Aegis Life Science, India). The cecum was ligated carefully using sterile silk suture 2-0 (Ethicon, India) so as to close the incision without interrupting the blood flow. The cecum was placed back to its position and abdominal incision was closed using chromic catgut for peritoneal and muscle and finally using suture clips [100 STICHS suture clips, 14 mm N.S. Medicon)], and povidone iodine ointment (Betadiene Win Medicare, India) was applied over the sutured area. Post-operatively, the animals were placed in the clean cage (one animal per cage) on a bedding of autoclaved husk. The animals were allowed to recover from anesthesia and provided with water and food ad libitum, and povidone iodine ointment (Betadine Win Medicare, India) was applied on the incision wound daily. For group VI, denoted as sham, all the steps were followed for these group animals. However, no tablet was inserted, and only gelatin sponge was inserted. The objective behind keeping this group was to evaluate the effect caused by trauma of surgical operation on the inflammatory process.

On the tenth day, all the animals of all the groups were sacrificed. The colon was isolated, and a 10-cm segment of the distal colon proximal to rectum was resected, rinsed in ice-cold saline, and evaluated for histological examination and quantitative myeloperoxidase activity.

Quantitative Measurement of MPO Activity

The MPO activity measurement was done as described earlier (21,28). Briefly, tissue specimens accurately weighed in range 200–400 mg were triturated using 1 ml hexadecyltrimethyl ammonium bromide buffer (Sigma-Aldrich, India) (0.5% HTAB in 50 mM phosphate buffer, pH 6) in an ice bath and homogenized using a cyclomixer (Remi Pvt. Ltd., India). After homogenization, the container was rinsed twice with 1 ml of HTAB. The pooled 3-ml homogenate of each specimen was sonicated and freeze–thawed thrice. Freeze–thawing helps to release the enzyme from the cells. The homogenate was centrifuged at 3,000 rpm for 5 min, and MPO activity of the supernatant was estimated by method mentioned below.

Briefly, 100 μl of supernatant was combined with 2.9 ml of 50 mM phosphate buffer, pH 6, containing 0.167 mg/ml of o-dianisidine dihydrochloride (Sigma-Aldrich, India) and 0.0005% H2O2 in an ice bath. The absorbance is measured at 460 nm against the blank (i.e., reagent without the supernatant).

Histological Examination of Colon for Presence of Myeloid Cells and Inflammation

The colonic tissues were harvested as described in “Experimental Design and Scheme” section. The tissues were post-fixed overnight in 10% w/v formaldehyde in saline (Sigma-Aldrich, India) at 4°C, dehydrated over a graded series of alcohol, and paraffin embedded. Sections of 5 μm were cut on a microtome (Leica, Germany). The sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Interpretations were made on the basis of lesions. Lesions were graded on the basis of tissue reaction, inflammatory cells, tissue damage, and architecture of tissue with grade V as the most severe and grade I as mild. In small laboratory animals, degeneration of mucosa with occasional mononuclear infiltration is usually a normal feature, and this fact was considered while interpreting the results.

Statistical Analysis

The results were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Bonferroni’s multiple comparison post hoc test using GraphPad Prism statistical software. P values < 0.05 were considered to be significant. Error bars depict S.E.M. if not mentioned differently.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The 5-ASA is effective in the treatment of inflammatory bowel diseases especially ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. It has been reported that 5-ASA is extensively absorbed and metabolized in the upper gastrointestinal tract by first pass metabolism and is not made available to the desired site, i.e., colon (15). With this objective, colonic delivery tablets based on natural polymers like guar gum and pectin were designed to pass through the upper part of gastrointestinal tract in the intact form without diffusion of active ingredients. Once the tablets reached the large intestine, the drug release should commence. Based on this concept, colon-specific 5-ASA tablets were prepared with release retardant guar gum (Grade ULV 1000) and pectin (with low degree of methoxylation) using formulation approach of compression coating represented by the schematic diagram (Fig. 1a, b). The 5-ASA (250 mg in case of human consumption and 50–54 mg for experimental colitis model study) was incorporated in the core tablet over which polymer coat of guar gum or pectin was applied by compression coating method (Tables I and II). In case of pectin tablets, additional enteric coat of hydroxypropyl methylcellulose phthalate was applied over the compression coat. This is because pectin tablet formulations showed disintegration in pH 1.2 buffer and swelling in pH 6.8 buffer. This was attributed to the polyelectrolyte nature and lower degree of methoxylation of pectin. Therefore, in case of pectin formulation, protective enteric coat was applied as shown in Fig. 1. Both formulations were analyzed for drug excipient compatibility by DSC method. An endothermic transition assignable to the melting of the compound was observed at a temperature of 279–280°C for the pure drug (5-ASA) as well as formulations of 5-ASA with guar gum and pectin polymers. The drug and added excipients were found to be compatible since no endothermic peak other than drug was obtained. The thermographs of pure drug as well guar gum and pectin formulations were similar (Fig. 1c). Compatibility of the drug with the excipients was maintained.

In vitro drug release profile of formulated tablets showed negligible release (3.45% in case of guar gum and 4.96% in case of pectin) at the end of 6 h in simulated gastric fluid and intestinal fluid representing upper GIT. However, in simulated colonic fluid comprising of colonic microflora, a constant and continuous drug release was obtained for a period of 18 h as shown in Fig. 1d. The drug release was observed to be about 80% indicating colon specificity of both the formulations prepared using guar gum and pectin as release retarding polymers.

The order of drug release kinetics was predicted by computing regression (R) coefficient of the curves, viz. % drug released (Q) vs. time and log % drug retained vs. time, and values obtained for “R” are as depicted in Table III. The lower values of “R” for the curve % drug released vs. square root time indicate that drug release is not certainly by diffusion of the drug through the polymer. The “R” values of the curves % drug released vs. time and log % drug retained vs. time indicate that both the formulations follow pseudo-zero/first-order drug release. Such system can be classified as bioerodible dissolution-controlled reservoir type of system.

Table III.

Drug Release Kinetic Prediction by Regression Coefficient

| Regression coefficient | Guar gum | Pectin |

|---|---|---|

| % drug released vs. time | 0.9413 | 0.9611 |

| Log % drug retained vs. time | 0.8802 | 0.8839 |

| % drug release vs. square root time | 0.7702 | 0.7982 |

The polymer coat got degraded and eroded by the virtue of colonic flora present in the simulated colonic fluid and drug release occurred. These observations confirmed the concept of site-specific sustained release tablet from compression coated formulations of these two polymers. In fact, in absence of colonic microflora, the tablets were found to be intact, and there was no erosion of the polymers.

Having done in vitro drug release profile, we further analyzed developed formulations using colitis rat model. Colitis was induced in the distal colon of the rats using 2,4,6-trinitrobenzenesulfonic acid and acetic acid (23–26). Overall, acetic acid (0.163 ± 0.013) was found to be a stronger colitis-inducing agent than 2,4,6-trinitrobenzenesulfonic acid (0.141 ± 0.0063) as seen in Table IV. The degree of inflammation observed in untreated (2,4,6-TNBS-induced colitis 0.143 ± 0.014 and acetic acid-induced colitis 0.1525 ± 0.019) and sham (2,4,6-TNBS-induced colitis 0.141 ± 0.0063 and acetic acid-induced colitis 0.163 ± 0.013) group animals were similar (Table IV). Surgical insertion procedure of colonic tablet did not cause any added inflammation in animals indicating it as non-traumatic. The inflammation observed in sham group animals was attributed because of an inducing agent.

Table IV.

Absorbance at 460 nm Depicting Myeloperoxidase Activities

| Groupsa | 2,4,6-TNBS (mean ± SEM) | Acetic acid (mean ± SEM) |

|---|---|---|

| Normal | 0.0287 ± 0.0009 | 0.0287 ± 0.0009 |

| Sham | 0.141 ± 0.0063 | 0.163 ± 0.013 |

| Guar gum | 0.0146 ± 0.0005 | 0.0203 ± 0.0021 |

| Pectin | 0.026 ± 0.0078 | 0.0538 ± 0.0015 |

| 5-ASA | 0.0995 ± 0.004 | 0.1364 ± 0.026 |

| SASP | 0.064 ± 0.002 | 0.094 ± 0.0083 |

| Untreated | 0.143 ± 0.014 | 0.1525 ± 0.019 |

5-ASA 5-aminosalicylic acid, SEM standard error of mean, SASP sulfasalazine, 2,4,6-TNBS 2,4,6,-trinitrobenzenesulfonic acid

a N = 4–5 animals per group

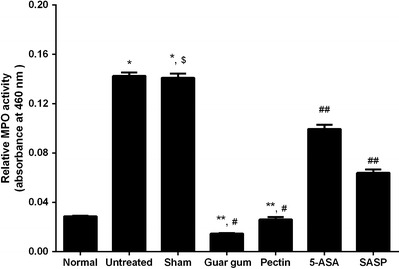

Treatment with 5-ASA was found to alleviate inflammation up to 30% in 2,4,6-TNBS-induced colitis (0.0995 ± 0.004) and 10% in acetic acid-induced colitis (0.1364 ± 0.026) as compared to untreated and sham group animals as seen in Figs. 2 and 3. Oral treatment with prodrug SASP was observed to be effective as an anti-inflammatory agent in both colitis models, i.e., reducing the inflammation up to 65% in 2,4,6-TNBS-induced colitis (0.064 ± 0.002) and 68% in acetic acid-induced colitis (0.094 ± 0.0083) as shown in Figs. 2 and 3.

Fig. 2.

Estimation of degree of inflammation measured as myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity in 2,4.6-TNBS-induced colitis model. The MPO activity measurement showed the significant inflammation in untreated and sham group animals as compared to normal animals (*p < 0.05 significant vs. normal), and the degree of inflammation in untreated and sham group animals was similar ($p > 0.05 non-significant vs. untreated). Colon-specific tablets formulated with guar gum and pectin showed significant reduction in inflammation as compared to untreated and sham group (**p < 0.05 significant) animals as well as 5-ASA and SASP group animals (#p < 0.05 significant). The inflammation observed in 5-ASA and SASP treatment group animals also reduced significantly as compared to untreated and sham group animals (##p < 0.05 significant) (Animals used in each groups were n = 4–5)

Fig. 3.

Estimation of degree of inflammation measured as MPO activity in acetic acid-induced colitis model. The significant inflammation was observed in untreated and sham group animals as compared to normal animals (*p < 0.05 significant vs. normal), and the degree of inflammation in untreated and sham group animals was similar ($p > 0.05 non-significant vs. untreated) as measured by myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity. Colon-specific tablets formulated with guar gum and pectin showed significant reduction in inflammation as compared to untreated and sham group (**p < 0.05 significant) animals. Similarly, the inflammation observed with guar gum and pectin formulations were significantly reduced compared to 5-ASA and SASP group animals (#p < 0.05 significant). The inflammation observed in 5-ASA and SASP treatment group animals also reduced significantly as compared to untreated and sham group animals (##p < 0.05 significant). (Animals used in each groups were n = 4–5)

Colon-targeted formulations prepared with guar gum and pectin were found to be more effective as anti-inflammatory dosage forms as compared to conventional oral treatment with 5-ASA and SASP. The colon-specific formulation with guar gum was demonstrated to reduce the inflammation up to 90% in 2,4,6-TNBS-induced colitis (0.0146 ± 0.0005) and 87% in acetic acid-induced colitis (0.0203 ± 0.0021) compared to untreated and sham group animals as depicted in Table IV and Figs. 2 and 3. Similarly, other formulation using pectin as polymer was found to be effective colon-specific formulation as anti-inflammatory dosage forms decreasing inflammation up to 82% in 2,4,6-TNBS-induced colitis (0.026 ± 0.0078) and 65% in acetic acid-induced colitis (0.0538 ± 0.0015) as compared to untreated and sham group animals (Table IV and Figs. 2 and 3). Colon-targeted formulation with pectin was found to be more effective in 2,4,6-TNBS model as compared to acetic acid models.

The comparison of both the formulations showed that colon-specific formulation with guar gum was superior in comparison to pectin as anti-inflammatory dosage form with respect to myeloperoxidase activity measurements.

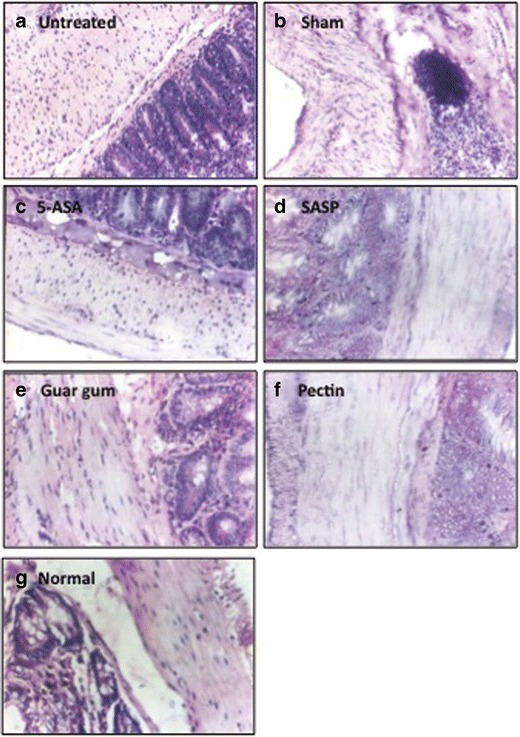

We further confirmed the results with histological analysis of tissue samples harvested from each group of animals. Interpretations were made on the basis of lesions, infiltration of mononuclear cells, and tissue architecture. Lesions were graded on the basis of tissue reaction, inflammatory cells, tissue damage, and architecture of tissue with grade V as the most severe lesion and grade I as mild comparable to normal.

In 2,4,6-TNBS-induced colitis model, untreated and sham group animals showed grades III and IV lesions with mucosal degeneration, exfoliation, and mononuclear infiltration. In sham group animals, glandular epithelium revealed advanced degenerative changes, which was evident in submucosa and muscularis layer, and at many foci, villi revealed necrosis whereas in untreated group animals tissue architecture was maintained (Fig. 4a, b). The animals treated orally with 5-ASA showed grade III lesions wherein mucosal epithelium revealed degeneration and mononucler infiltration. Muscularis layer appeared degenerated with infiltration by mononuclear lymphocytes (Fig. 4c). Very mild lesions were observed in animals treated with prodrug SASP as shown in Fig. 4d comparable to the normal group animals (Fig. 4g; grade I). Lesions were very mild without much exfoliation degeneration and mononuclear in filtration (grade I), i.e., comparable to normal in animals treated with colon-specific formulations made with guar gum (Fig. 4e) and pectin (Fig. 4f).

Fig. 4.

Anti-inflammatory effect detected in the colon tissue with 2,4,6-TNBS-induced colitis model. The untreated a and sham group b animal tissue showed degenerative changes, mononuclear infiltration indicating inflammation. The 5-ASA c treatment showed degeneration in tissue architecture with mononuclear infiltration, whereas SASP d treated animals showed mild degeneration with few mononuclear cells comparable to normal group animals. g The animals treated with colon-specific drug delivery formulation, viz. guar gum e and pectin f showed no signs of inflammation, and it was comparable to the normal group animals g

Acetic acid-induced colitis model was severe colitis-inducing model in comparison with 2,4,6-TNBS. Untreated group animals in this model showed severe lesions with necrosis loss and replacement of villi with inflammatory reaction and hemolysis, and submucosa appeared thickened and edematous (grade V) as seen Fig. 5a. In sham group animals, mucosal epithelium revealed hyperplasia and focal exfoliation with degenerative changes and mononuclear infiltration (grade IV; Fig. 5b). The animals treated with 5-ASA showed distorted architecture, and all the layers revealed mononuclear cell infiltration. At many foci, mucosa appeared as replaced by inflammatory tissue (grade IV+) as delineated in Fig. 5c, whereas degeneration in cells of mucosa, architecture maintained but lesions of mild intensity were observed (grade III) in SASP-treated animals as seen in Fig. 5d. Changes were mild; mononuclear cells were seen in mucosa only. Architecture was well maintained (grade II) in animals treated with colon-specific guar gum tablets (Fig. 5e). The colon-targeted pectin tablet showed very mild lesions without much exfoliation degeneration and mononuclear in filtration (grade II), i.e., comparable to normal group animals Fig. 5g as depicted in Fig. 5f.

Fig. 5.

Anti-inflammatory effect in the colon tissue using acetic acid-induced colitis model. The untreated a and sham group b animal tissue showed degenerative changes, mononuclear infiltration indicating inflammation. The 5-ASA c treatment showed degeneration in tissue architecture with mononuclear infiltration. The animals treated with SASP d showed mild degeneration with few mononuclear cells comparable to normal group animals. g The colon-specific drug delivery formulation, viz guar gum e and pectin f treatment, showed no signs of inflammation, and it was comparable to the normal group animals g

DISCUSSION

The colon-specific formulation of 5-ASA using release retardant polymers guar gum and pectin were formulated using compression coating approach. Both formulations were evaluated for drug excipient compatibility. The polymers were analyzed by rheology and gel permeation chromatography and characterized as per compendial standards. The developed formulations were found to be colon-specific as shown by in vitro drug release profile in simulated colonic fluid comprising colonic microflora. The release of drug from both formulations followed pseudo/first-order kinetics implicating bioerodible dissolution-controlled, reservoir type of system. Since in vitro data showed a site-specific drug release, we further evaluated specificity of colon-targeted formulations using two colitis-induced inflammatory in vivo rat models with quantitative estimation of myeloperoxidase activity as the measure of inflammation to provide proof of concept and further confirm that these developed formulations were comparable to colon-specific prodrug sulfasalazine in treating inflammatory bowel conditions.

The distal colon colitis was induced using two chemical agents, namely 2,4,6-trinitrobenzenesulfonic acid and acetic acid (23–26). The objective behind using two colitis-inducing agents was to make their comparative evaluation and to determine whether the formulations developed are effective in acute as well as chronic conditions (21,29).

Colon-specific tablets of guar gum and pectin were inserted surgically in the cecum. The tablets disintegrated in the cecum by the virtue of degradation of the polymer brought about by colonic microflora, and the drug was made available for healing the inflammation-induced artificially in the distal colon. The anti-inflammatory effect of the tablets was compared against standard 5-ASA and sulfasalazine (a colon-specific prodrug) given orally in another treatment groups.

5-ASA administered in three forms as conventional, as colonic prodrug SASP, and as polymeric formulation (with guar gum and pectin) showed protective anti-inflammatory effect to a variable extent. Colon-specific prodrug sulfasalazine, although administered, daily could not provide anti-inflammatory effect comparable to guar gum and pectin formulations.

Guar gum consists of polysaccharide built by β-(1→4) linkages with a side branching unit of a single d-galactopyranose unit joined to every other mannose unit by α-(1→6) linkages. Guar gum consists of primarily galactomannans, whereas pectin predominantly comprises of linear polymers of α-(1–4)-linked d-galacturonic acid residues interrupted by 1,2-linked l-rhamnose residues (9,30).

The formulations prepared with polymers (guar gum and pectin) found to be more beneficial with respect to anti-inflammatory activity compared to prodrug SASP. It has been reported that these two polymers have protective effect against inflammation in GIT (31,32). Guar gum, as a water-soluble fiber, has been reported to have beneficial effect in bowel-related ailments such as diverticulosis, Crohn’s disease, colitis, and irritable bowel syndrome (33). The C-glycosylated and sulfated derivatives of guar gum have been shown to have anti-inflammatory activity (34). Low methoxylated (LM) pectin showed more anti-inflammatory effect than high methoxylated (HM) pectin upon oral administration. LM pectin was found to inhibit both local and systemic inflammation (35). The presence of galacturan in the pectin imparts anti-inflammatory effect. The galacturonan isolated from pectin, the main carbohydrate chain (backbone) of its macromolecule, showed a marked anti-inflammatory effect.

We speculate that the structural characteristics of two polymers could be the contributing factor for added anti-inflammatory effect since they act synergistically along with 5-ASA.

Interpretation of data obtained from in vivo study should be taken into account certain limitations of the experimental model. The dosages designed in present study are for oral use for human consumption and to study their site-specific release in disease state using animal model is challenging. Considering all these challenges and to mimic in vivo biology, we evaluated our dosage forms with necessary controls. After obtaining the data from in vivo study, we further tested the formulations for human consumption using gamma scintigraphy in humans for colon-specific drug release, and we confirmed the colon-specific drug release in human (unpublished data).

Further investigation of these formulations in human will warrant their application in various colon-specific inflammatory ailments.

CONCLUSION

Taken together, our results showed that the colon-targeted formulation of 5-aminosalicylic acid prepared with two polymers (guar gum and pectin), using compression coating method, was found to release drug (~80%) in colon as revealed by in vitro drug data. Furthermore, evaluation of these colon-specific formulations showed anti-inflammatory effect alleviating chemically induced colitis in rat model, and it was more effective than prodrug SASP as well as 5-ASA when given orally.

Acknowledgments

The Board of Radiation and Nuclear Sciences, Department of Atomic Energy, Bhabha Atomic Research Centre (BARC), India funded this project. We thank Dr. D.K. Chatterjee, Head of Toxicology, Quest Institute of Life Sciences, India for the guidance and helpful discussion and Dr. Mayur Yergeri, Principal, Dr. Bhanuben Nanavati College of Pharmacy, for his support.

REFERENCES

- 1.Antonin KH, et al. Colonic absorption of human calcitonin in man. Clin Sci (Lond) 1992;83(5):627–31. doi: 10.1042/cs0830627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saffran M, et al. A new approach to the oral administration of insulin and other peptide drugs. Science. 1986;233(4768):1081–4. doi: 10.1126/science.3526553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gibson SA, et al. Significance of microflora in proteolysis in the colon. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1989;55(3):679–83. doi: 10.1128/aem.55.3.679-683.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Youan BB. Chronopharmaceutics: gimmick or clinically relevant approach to drug delivery? J Control Release. 2004;98(3):337–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2004.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kinget R, et al. Colonic drug targeting. J Drug Target. 1998;6(2):129–49. doi: 10.3109/10611869808997888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang L, Chu JS, Fix JA. Colon-specific drug delivery: new approaches and in vitro/in vivo evaluation. Int J Pharm. 2002;235(1-2):1–15. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Rubinstein A. Microbially controlled drug delivery to the colon. Biopharm Drug Dispos. 1990;11(6):465–75. doi: 10.1002/bdd.2510110602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brondsted H, Kopecek J. Hydrogels for site-specific drug delivery to the colon: in vitro and in vivo degradation. Pharm Res. 1992;9(12):1540–5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Shah N, Shah T, Amin A. Polysaccharides: a targeting strategy for colonic drug delivery. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2011;8(6):779–96. doi: 10.1517/17425247.2011.574121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wakerly Z, et al. Pectin/ethylcellulose film coating formulations for colonic drug delivery. Pharm Res. 1996;13(8):1210–2. doi: 10.1023/A:1016016404404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krishnaiah YS et al. Guar gum as a carrier for colon specific delivery; influence of metronidazole and tinidazole on in vitro release of albendazole from guar gum matrix tablets. J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2001;4(3):235–43. [PubMed]

- 12.Prasad YV, Krishnaiah YS, Satyanarayana S. In vitro evaluation of guar gum as a carrier for colon-specific drug delivery. J Control Release. 1998;51(2-3):281–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Azad Khan AK, Piris J, Truelove SC. An experiment to determine the active therapeutic moiety of sulphasalazine. Lancet. 1977;2(8044):892–5. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(77)90831-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chourasia MK, Jain SK. Pharmaceutical approaches to colon targeted drug delivery systems. J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2003;6(1):33–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bondesen S. Intestinal fate of 5-aminosalicylic acid: regional and systemic kinetic studies in relation to inflammatory bowel disease. Pharmacol Toxicol. 1997;81(Suppl 2):1–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0773.1997.tb01944.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Friedman G. Sulfasalazine and new analogues. Am J Gastroenterol. 1986;81(2):141–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klotz U. Clinical pharmacokinetics of sulphasalazine, its metabolites and other prodrugs of 5-aminosalicylic acid. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1985;10(4):285–302. doi: 10.2165/00003088-198510040-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bos A, Wever R, Roos D. Characterization and quantification of the peroxidase in human monocytes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1978;525(1):37–44. doi: 10.1016/0005-2744(78)90197-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matheson NR, Wong PS, Travis J. Isolation and properties of human neutrophil myeloperoxidase. Biochemistry. 1981;20(2):325–30. doi: 10.1021/bi00505a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bradley PP, et al. Measurement of cutaneous inflammation: estimation of neutrophil content with an enzyme marker. J Invest Dermatol. 1982;78(3):206–9. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12506462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krawisz JE, Sharon P, Stenson WF. Quantitative assay for acute intestinal inflammation based on myeloperoxidase activity. Assessment of inflammation in rat and hamster models. Gastroenterology. 1984;87(6):1344–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tozaki H, et al. Validation of a pharmacokinetic model of colon-specific drug delivery and the therapeutic effects of chitosan capsules containing 5-aminosalicylic acid on 2,4,6-trinitrobenzenesulphonic acid-induced colitis in rats. J Pharm Pharmacol. 1999;51(10):1107–12. doi: 10.1211/0022357991776796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morris GP, et al. Hapten-induced model of chronic inflammation and ulceration in the rat colon. Gastroenterology. 1989;96(3):795–803. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.MacPherson B, Pfeiffer CJ. Experimental colitis. Digestion. 1976;14(5-6):424–52. doi: 10.1159/000197966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Selve N, Wohrmann T. Intestinal inflammation in TNBS sensitized rats as a model of chronic inflammatory bowel disease. Mediat Inflamm. 1992;1(2):121–6. doi: 10.1155/S0962935192000206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fitzpatrick LR, et al. Antiinflammatory effects of various drugs on acetic acid induced colitis in the rat. Agents Actions. 1990;30(3-4):393–402. doi: 10.1007/BF01966304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Paget GE, Branes GM. Evaluation of drug activities. In: Laurance, Bacharach, editors. Pharmacometrics. New York: Academic; 1964. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fedorak RN, et al. Colonic delivery of dexamethasone from a prodrug accelerates healing of colitis in rats without adrenal suppression. Gastroenterology. 1995;108(6):1688–99. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90130-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vogel G, V, ed. Drug discovery and evaluation: pharmacological assays. In: V G, editors. Frankfurt am Main, Springer-Verlag Heidelberg Berlin New York. 1997; 3.5:508–9.

- 30.Sinha VR, Kumria R. Polysaccharides in colon-specific drug delivery. Int J Pharm. 2001;224(1-2):19–38. doi: 10.1016/S0378-5173(01)00720-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fan MZ, et al. Consumption of guar gum and retrograded high-amylose corn resistant starch increases IL-10 abundance without affecting pro-inflammatory cytokines in the colon of pigs fed a high-fat diet. J Anim Sci. 2012;90(Suppl 4):278–80. doi: 10.2527/jas.54006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Popov SV, et al. Antiinflammatory activity of the pectic polysaccharide from Comarum palustre. Fitoterapia. 2005;76(3-4):281–7. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2005.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Takahashi T, et al. Hydrolysed guar gum decreases postprandial blood glucose and glucose absorption in the rat small intestine. Nutr Res. 2009;29(6):419–25. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2009.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Popov SV, et al. Anti-inflammatory activity of low and high methoxylated citrus pectins. Biomed Prev Nutr. 2013;3(1):59–63. doi: 10.1016/j.bionut.2012.10.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Markov PA, et al. Anti-inflammatory activity of pectins and their galacturonan backbone. Russ J Bioorg Chem. 2011;37(7):817–21. doi: 10.1134/S1068162011070132. [DOI] [Google Scholar]