Abstract

Objective

Psychiatric, medical, and substance use comorbidities are highly prevalent among smokers, and many of these comorbidities have been found to associate with reduced rate of success in clinical trials for smoking cessation. While much has been established about the best available treatments from these clinical trials, little is known about the effect of concomitant psychiatric medications on quit rates in smoking cessation programs. Based on results in populations with tobacco dependence and other substance use disorders, we hypothesized that smokers taking antidepressants would have a lower rate of quitting in an outpatient smoking cessation program.

Method

We performed a naturalistic chart review of Veterans (N=144) enrolled in the Veterans Affairs Greater Los Angeles Mental Health Clinic Smoking Cessation Program from March of 2011 through July of 2013, who met DSM-IV-TR criteria for nicotine dependence. The primary outcome was smoking cessation with treatment, as evidenced by a patient report of at least 1 week of abstinence and an exhaled carbon monoxide of ≤ 6 ppm (if available) at the end of acute treatment, with comparators including concomitant psychotropic medication treatment, psychiatric and medical comorbidities, and the presence of a substance use disorder history. We utilized stepwise binary logistic regression as the main statistical technique.

Results

We found that current antidepressant treatment (p=0.015) and history of substance use disorder (p=0.01) (particularly cocaine (p=0.02)) were associated with a lower rate of quitting smoking. Furthermore, the association between antidepressant treatment and reduced rate of smoking cessation was primarily seen in patients with a history of substance use disorder (p=0.003).

Conclusions

While preliminary, these results suggest an important clinical interaction meriting future study. If these findings are confirmed, clinicians may want to consider the risk of reduced ability to quit smoking in patients with a history of substance use disorder taking antidepressants.

Keywords: substance use disorder, antidepressant, tobacco, smoking, treatment, Veteran

Introduction

Despite many years of public health efforts, tobacco smoking remains the largest modifiable risk factor for increased morbidity and mortality worldwide, with the current rate of smoking at around 20% in the U.S.1. Smoking has been estimated to result in 400,000 excess deaths per year in the U.S. alone, due to the increased risk for lung disease (including cancer) and cardiovascular disease (including stroke and myocardial infarction)2. Current treatment modalities, both psychological and pharmacological, are effective for only a minority of smokers seeking treatment3. In addition, psychiatric and substance use comorbidities are highly prevalent among smokers, and many of these factors have been found to associate with reduced smoking cessation rates in both naturalistic studies and clinical trials4, 5. Smoking rates of up to 80% have been reported in patients with substance use disorders, while patients with psychotic disorders and bipolar disorder also have very high rates compared to the general population (~50–60%)5. Depression has been shown to have a strong comorbid relationship with smoking, in that individuals with a history of depression are more likely to smoke (~37–44% rate) than those without6, 7. Smokers with depression also have a modestly reduced rate of smoking cessation in clinical trials8. Combined with the observation that nicotine withdrawal results in increased depressive symptoms in depressed smokers, these data highlight the significant public health problem that smoking in depressed individuals represents8, 9.

These clinical observations have provided ample reason for large numbers of clinical trials of antidepressants for smoking and depression, with the thought being that ameliorating depressive symptoms among smokers may assist in smoking cessation efforts8, 9. However, the combined effort of many years of clinical trials involving thousands of depressed smokers worldwide provides support only for the use of bupropion and tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs)), which are effective for smokers with or without depression8, 9. Because of the high comorbidity of depression and smoking, active smokers with cardiovascular comorbidities10, or who are treatment-seeking (cf.11) have high rates of antidepressant use (25 and 17%, respectively). Therefore, the fact that antidepressants are commonly prescribed to active smokers indicates a vital need to better understand the interaction of pharmacological treatment for depression and smoking cessation treatment outcome in smokers.

Surprisingly, several studies of antidepressant usage in smokers have shown a tendency for antidepressant use to be associated with lower rates of smoking cessation10–13. These findings, which are somewhat counterintuitive, have some parallels in studies of antidepressant treatment for other substance-use disorders, where similar results have been reported (cf.14). Heavy-drinking alcoholics (“Type B”) have shown a strong tendency to increased alcohol consumption with several antidepressants in clinical trials (reviewed in15, with more recent confirmation of this effect for sertraline16). An outpatient study of sertraline for methamphetamine dependence showed increased methamphetamine use in patients taking active medication17. Similarly, a recent placebo-controlled trial of fluoxetine for cocaine dependence showed that fluoxetine treatment reduced the efficacy of contingency management18.

Based on the reported association of antidepressant use and poor outcomes in some studies of smoking cessation and substance use disorder treatment, we performed a naturalistic chart review study, using clinical data containing comprehensive listings of prescribed medications and comorbid conditions during smoking cessation treatment at the Greater Los Angeles Veterans Affairs Mental Health Clinic Smoking Cessation Program. Our hypothesis was that current antidepressant treatment would be associated with a lower rate of smoking cessation as compared to antipsychotic and mood stabilizer treatment, and that this effect would be more prominent in patients with a history of substance use disorder. The relationship of smoking cessation to both antidepressant treatment and history of substance use disorder has not previously been reported.

Method

Participants

The chart review protocol was approved by the VA Greater Los Angeles Institutional Review Board. Charts selected for review included all patients seen for smoking cessation treatment at the VA Greater Los Angeles Mental Health Clinic Smoking Cessation Program, from the period of March of 2011 through July of 2013. All patients treated in this clinic have a history of psychiatric and/or substance use disorders, while meeting DSM-IV-TR criteria for nicotine dependence; details of the clinic treatment and patient entry criteria were described previously4. Clinic treatment consists of a 12–16 week course of nursing medical case management, weekly 45 min group cognitive behavioral therapy sessions with a psychologist, and weekly medication management visits with a psychiatrist (A.L.B and T.Z.). Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI19), Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND20), and exhaled carbon monoxide levels (CO) were collected typically at clinic entry; however, due to occasional clinic staffing shortages or equipment malfunction, these measures were not collected on all patients.

Participants were included in this chart review if they showed at least minimal participation in the clinic, by attending at least two clinic sessions within 60 days with medication treatment for smoking cessation, or at least three clinic sessions without medication treatment. A participant was considered to have ended treatment if he or she was absent from the clinic for more than 60 days. Participants were considered to have quit smoking if they had reported >7 days smoking abstinence along with exhaled CO levels of ≤ 6 PPM (when available) at the end of acute (typically 3–4 month) treatment. If a participant had multiple clinic quit attempts during the study time frame only the longest period of treatment was included in this review. Exclusionary criteria for the study were: insufficient clinical information (e.g., missing documentation of prescribed medications); any other treatment for smoking within the last 30 days prior to clinic entry; smoking fewer than 5 cigarettes per day on entry into clinic; treatment still ongoing as of July, 2013; smoking pipes, cigars, or rolled tobacco; primarily using chewing tobacco; or starting or stopping psychotropic medication use during the course of smoking cessation treatment (aside from bupropion).

Comorbid Medical and Psychiatric Conditions and Medication Treatment

Current and past medical and psychiatric diagnoses (including histories of substance use disorder) were obtained from the participants’ electronic medical records. For documentation of the primary substance use disorder (where present), we first surveyed their current and past computer health record problem lists, then reviewed any prior treatment episodes that documented a history of substance use disorder (including emergency room visits, inpatient hospitalizations, and documentation of substance use disorder treatment episodes). Diagnoses and adjunctive medication treatments were included in the analysis if they represented > 5% of the sample.

Antidepressants included therapeutic doses of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (such as fluoxetine), tricyclic antidepressants (such as amitriptyline), and atypical antidepressants such as nefazodone, mirtazapine, and trazodone. Low-dose trazodone (≤ 150 mg/ day) used for insomnia was not counted as antidepressant treatment for the purposes of this study, as it has not shown efficacy as an antidepressant in this dose range21. Antipsychotics included both older typical and newer atypical antipsychotics. Mood stabilizers included therapeutic doses of lithium, carbamazepine, valproate, and lamotrigine.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were accomplished using R v. 2.13 (R Core Team: Vienna, Austria, 2012) and IBM SPSS v.21.0 (IBM: Armonk, New York, USA; 2012). ANOVA and Fisher’s exact tests were used to assess for potential confounding factors based upon the clinical data. We utilized a stepwise binary logistic regression to assess for the effect of psychotropic medication treatment while accounting for confounding factors. To account for multiple comparisons for different categories of psychotropic medication, we utilized Bonferroni correction, accounting for each set of regressions run on the data (three for Figure 1, two for Figure 2).

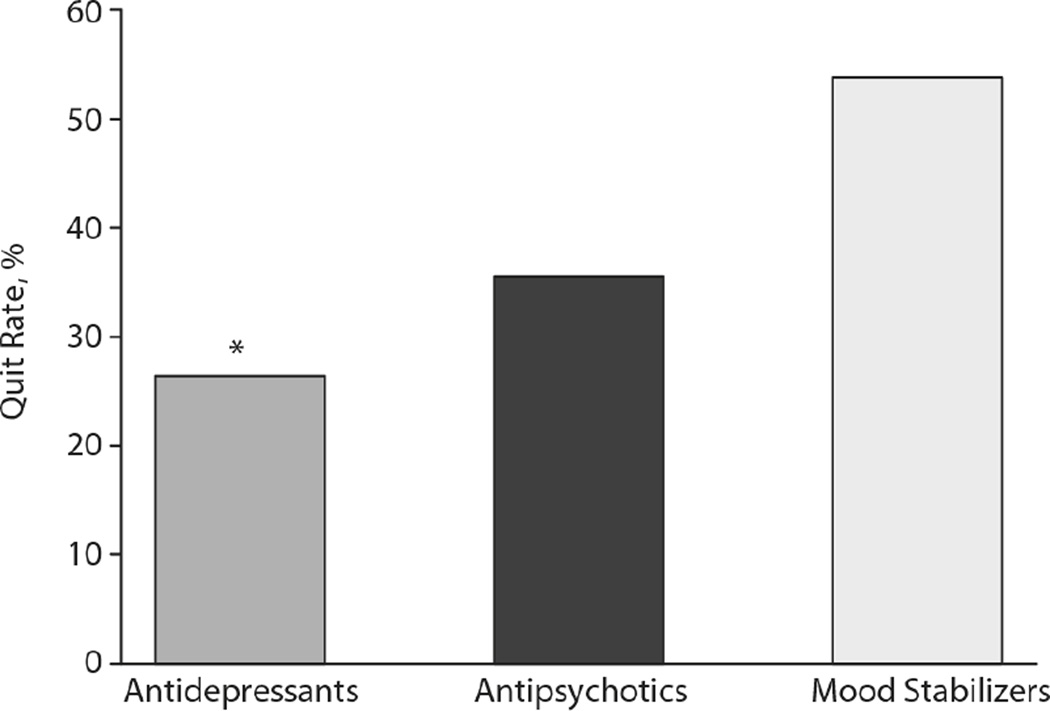

Figure 1.

Smoking cessation clinic quit rates for patients with respect to psychotropic medication treatment. Bars represent percentage quit rate for patients taking serotonergic antidepressants (ADP), antipsychotic (AP), and mood stabilizers (MS) out of the total number of patients taking each medication, while undergoing treatment for smoking cessation. *: indicates statistical significance (p<0.05) by stepwise binary logistic regression for group comparison, after Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons.

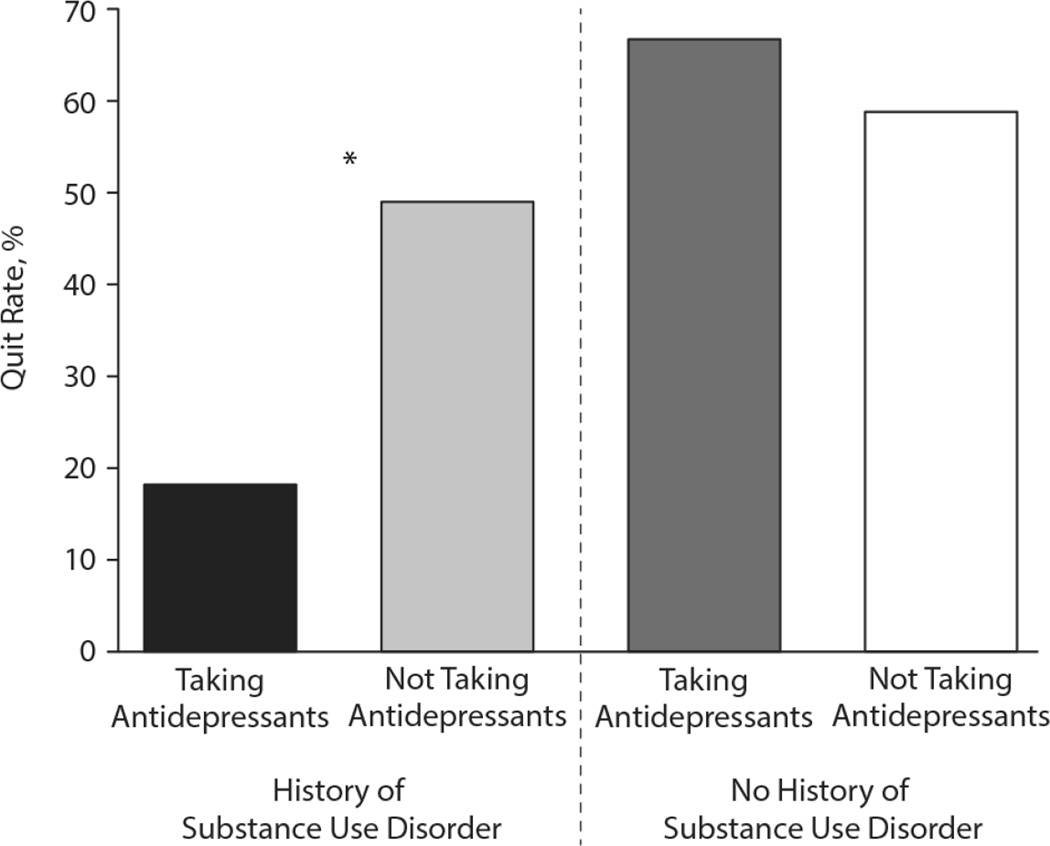

Figure 2.

Smoking cessation clinic quit rates for participants taking or not taking antidepressant medications with and without substance use disorder. The vertical axis represents the percentage of participants in each listed condition who quit during the study. ADP+: patients taking antidepressants; ADP−: patients not taking antidepressants; SUD: patients with a history of substance use disorder; no SUD: patients with no history of substance use disorder. *: indicates statistical significance (p<0.05) by stepwise binary logistic regression after Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons..

Results

Demographics and Clinical Characteristics

A total of 417 patients were enrolled in the clinic from March of 2011 through July of 2013. Of these, 205 met criteria for treatment engagement, as defined above. Seventeen patients were repeat patients, and thus excluded, while six patients were excluded due to insufficient clinical information available. Four patients were excluded for having been in another smoking cessation program within 30 days of entry to the clinic, eight were excluded for smoking non-cigarette forms of tobacco or using primarily chewing tobacco, and three patients were excluded because they either stopped or started psychotropic medication treatment during treatment for smoking cessation. Overall, 144 patient charts met full study criteria (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographics and Clinical Characteristicsa

| Category | Quitb | Not Quitb |

P Valuec |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total sample (N = 144) | 62 (43) | 82 (57) | NA |

| Age, y | 56.3 (11.0) | 55.3 (9.0) | .58 |

| BDI score, (n = 70) | 5.2 (3.8) | 5.5 (4.6) | .79 |

| Carbon monoxide level, ppm (n = 52) | 9.7 (5.0) | 14.8 (7.7) | .03* |

| No. of cigarettes/d | 15.6 (6.7) | 17.3 (9.6) | .24 |

| No. of weeks in treatment | 13.1(11.0) | 10.3 (10.3) | .11 |

| No. of sessions attended | 7.8 (4.8) | 6.7 (5.2) | .19 |

| FTND score (n = 71) | 5.5 (1.7) | 5.3 (2.0) | .79 |

| White | 21 (34) | 31 (38) | .82 |

| Male | 56 (90) | 80 (98) | .13 |

| Psychiatric/SUD history | |||

| Any SUD | 36 (58) | 64 (78) | .01* |

| Alcohol | 13 (21) | 29 (35) | .07 |

| Cocaine | 6 (10) | 21 (26) | .02* |

| Opiate | 9 (15) | 4 (5) | .08 |

| Methamphetamine | 2 (3) | 7 (9) | .3 |

| Multiple SUDs | 5 (8) | 4 (5) | .5 |

| Posttraumatic stress disorder | 16 (26) | 23 (28) | .85 |

| Psychosis | 11 (18) | 15 (18) | 1 |

| Depression | 19 (31) | 30 (37) | .48 |

| Bipolar disorder | 10 (16) | 12 (15) | .82 |

| Medical history | |||

| Cardiac | 8 (13) | 8 (10) | .6 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 18 (29) | 9 (11) | .01* |

| Hypertension | 36 (58) | 45 (55) | .74 |

| Liver disease | 8 (13) | 6 (7) | .27 |

| Lung disease | 14 (23) | 25 (30) | .35 |

| Back pain | 30 (48) | 32 (39) | .31 |

| Adjunctive medications | |||

| Antidepressants | 14 (23) | 39 (48) | .003* |

| Antipsychotics | 16 (26) | 29 (35) | .28 |

| Mood stabilizers | 7 (11) | 6 (7) | .56 |

| Opiates | 17 (27) | 16 (20) | .36 |

| Sedatives | 4 (6) | 5 (6) | 1 |

| Nicotine replacement therapy | 49 (79) | 59 (72) | .44 |

| Bupropion | 11 (18) | 25 (30) | .12 |

| Varenicline | 13 (21) | 10 (12) | .07 |

Listed statistical contrasts are uncorrected for multiple comparisons.

Values reported as n (%) for categorical variables and as mean (SD) for continuous variables.

Analysis of variance was used for continuous variables, and the Fisher exact test was used for categorical variables.

P values indicating a statistically significant comparison.

Abbreviations: BDI = Beck Depression Inventory, FTND = Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence, NA = not applicable, SUD = substance use disorder.

Table 1 presents an overview of the demographics of the patient population, broken down by whether they were able to quit smoking during clinic treatment or not. Quitters did not differ from non-quitters in terms of average age, intake BDI, reported cigarettes per day, number of weeks in treatment, number of sessions attended, entry FTND score, ethnicity, or gender distribution. Intake CO was higher for non-quitters (14.8±7.7 ppm) than quitters (9.7±5 ppm) in the participants for which this value was available (F(1,50)=4.8, p=0.03; Table 1).

With regard to psychiatric and medical histories of the participants, quitters and non-quitters did not differ in the frequency of diagnoses of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), psychotic disorders (including schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorders), major depression, or bipolar disorders (either I, II, or not otherwise specified), cardiac disease, hypertension, liver disease (including chronic hepatitis and cirrhosis), lung disease (including emphysema, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and asthma), or chronic back pain (Table 1). However, non-quitters had a higher rate of comorbid substance use disorder history than quitters (78% vs. 58%; p=0.01; Table 1). When broken down by primary substance use disorder, a history of cocaine use disorder was present more frequently in non-quitters than quitters (26% vs. 10%; p=0.02; Table 1). Furthermore, there was a trend to significance in quitters having a lower rate of alcohol use disorder history than non-quitters (21% to 35%, p=0.07; Table 1). There were no differences between quitters and non-quitters in the overall rate of methamphetamine use disorder or multiple substance use disorders (Table 1). By contrast, there was a trend to quitters having a higher rate of opiate use disorder than non-quitters (15% vs. 5%, p=0.08; Table 1). Quitters were also more likely than non-quitters to have a history of diabetes mellitus (29% vs. 11%, p=0.01). In terms of other adjunctive medications, quitters did not differ from non-quitters in the rate of concomitant prescription opiate treatment or sedative-hypnotic medication, or in the use of nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) or bupropion as smoking cessation treatments (Table 1). However, there was a strong trend to quitters being more likely to be taking varenicline for smoking cessation than non-quitters (21% vs. 12%; p=0.07; Table 1).

Psychotropic medication treatment and smoking cessation rates

In order to assess whether antidepressant treatment status continued to exhibit a significant effect after taking into account possible confounding factors, we performed a series of stepwise binary logistic regressions with quit status as the dependent variable (Figures 1 and 2; Tables 2 and 3). For the binary logistic regression with quit status versus antidepressant, antipsychotic, and/or mood stabilizer treatment, a smaller proportion of participants taking antidepressants quit (26% of N=53) than participants not taking antidepressants (53%; p=0.0025, Figure 1). By contrast, there was no significant difference in the proportion of patients quitting while taking antipsychotic (36% of N=44, p=0.22) or mood stabilizer medications (54% of N=13, p=0.41) (Figure 1).

Table 2.

Logistic Regression Models for Psychiatric History and Psychotropic Treatment

| Category | B | SE | Wald χ2 |

Pa | OR | 95% CI for OR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antidepressant treatment | ||||||

| Diabetes | 1.15 | 0.47 | 6 | .014* | 3.15 | 1.28–8.19 |

| Psychosis | −0.1 | 0.48 | 0.045 | .83 | 0.9 | 0.35–2.29 |

| Depression | 0.27 | 0.43 | 0.39 | .53 | 1.31 | 0.57–3.09 |

| Bipolar disorder | 0.57 | 0.54 | 1.1 | .29 | 1.78 | 0.62–5.21 |

| Antidepressant | −1.26 | 0.42 | 8.8 | .003* | 0.28 | 0.12–0.64 |

| Antipsychotic treatment | ||||||

| Diabetes | 1.25 | 0.46 | 7.3 | .0069* | 3.49 | 1.44–9 |

| Psychosis | 0.5 | 0.46 | 0.79 | .37 | 1.64 | 0.55–5.06 |

| Depression | −0.18 | 0.56 | 0.2 | .65 | 0.84 | 0.38–1.82 |

| Bipolar disorder | 0.48 | 0.4 | 0.76 | .38 | 1.61 | 0.55–4.84 |

| Antipsychotic | −0.91 | 0.51 | 0.32 | .073 | 0.4 | 0.14–1.05 |

| Mood stabilizer treatment | ||||||

| Diabetes | 1.17 | 0.46 | 6.6 | .01* | 3.23 | 1.35–8.19 |

| Psychosis | −0.06 | 0.46 | 0.016 | .9 | 0.94 | 0.37–2.33 |

| Depression | −0.13 | 0.39 | 0.1 | .75 | 0.88 | 0.4–1.91 |

| Bipolar disorder | −0.12 | 0.58 | 0.043 | .84 | 0.89 | 0.27–2.74 |

| Mood stabilizer | 0.49 | 0.72 | 0.47 | .49 | 1.63 | 0.4–2.93 |

Listed P values are uncorrected for multiple comparisons.

Statistical significance (P < .05) after Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons.

Abbreviations: B = regression coefficient, CI = confidence interval, OR = odds ratio, SE = standard error.

Table 3.

Substance Use Disorder Logistic Regression Results

| Category | B | SE | Wald χ2 |

Pa | OR | 95% CI for OR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All SUD | ||||||

| SUD history | −0.78 | 0.39 | 3.9 | .047 | 0.46 | 0.2–1.0 |

| Diabetes | 1.07 | 0.47 | 5.2 | .023* | 2.9 | 1.2–7.5 |

| Antidepressant treatment | −0.95 | 0.39 | 5.9 | .015* | 0.39 | 0.2–0.8 |

| Cocaine only | ||||||

| Cocaine history | −1.13 | 0.53 | 4.5 | .034 | 0.32 | 0.1–0.9 |

| Diabetes | 1.19 | 0.47 | 6.3 | .012* | 3.3 | 1.3–8.7 |

| Antidepressant treatment | −1.00 | 0.39 | 7 | .01* | 0.37 | 0.2–0.8 |

Listed P values are uncorrected for multiple comparisons.

Statistical significance (P < .05) after Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons.

Abbreviations: B = regression coefficient, CI = confidence interval, OR = odds ratio, SE = standard error, SUD = substance use disorder.

In order to provide convincing evidence that the deleterious effect of antidepressant treatment was not due to psychiatric history, we also performed stepwise binary logistic regressions with diabetes, psychiatric diagnoses, and psychotropic treatments as variables (Table 2). Antidepressant treatment remained the only significant medication treatment variable (p=0.003), though a strong trend was observed for antipsychotic treatment (p=0.072; Table 2). Subsequently, we looked at possible substance use disorder confounders, and found that the effect of adding antidepressant treatment status remained significant even after incorporating either history of substance use disorder (p=0.015) or cocaine use disorder (p=0.010), together with diabetes mellitus, into the model (Table 3). Analysis of the interaction of antidepressant treatment with either substance use disorder or cocaine use disorder reduced the overall quality of the model fit due to collinearity between substance use disorder and antidepressant treatment status (R2= 0.25; see next section), while there were no significant effects of the interactions between antidepressant treatment and diabetes history.

Smoking cessation quit rates, antidepressant treatment, and substance use disorder history

Based on the studies cited above showing that substance use disorders associate with poor response to antidepressant treatment15, 16, 22, 23, along with the collinearity we observed between substance use disorder history and antidepressant treatment, we tested the hypothesis that the negative effect of antidepressant treatment on smoking cessation quit rate would be seen primarily in patients with a history of substance use disorder (Figure 2). We separated the sample into patients with (N=101) and without (N=43) substance use disorder history, and compared the quit rate among those participants taking antidepressants in each category. We again utilized a stepwise binary logistic regression with history of diabetes mellitus as a potential confounding factor. Among patients with a history of substance use disorder, those taking antidepressants (N=8 (18%)) were less likely to quit smoking than those not taking antidepressants (N=28 (49%); p=0.003; Figure 2). By contrast, in patients without a history of substance use disorder, there was no overall difference in quit rate between patients taking (N=6 (67%)) or not taking (N=20 (58%)) antidepressants after accounting for diabetes history (p=0.82; Figure 2).

Discussion

Antidepressant treatment is associated with a lower rate of smoking cessation in a naturalistic clinic setting

We found that antidepressant treatment among Veterans with psychiatric and/or substance use disorder comorbidities was associated with a lower rate of smoking cessation, even after taking into account other possible confounding factors (Tables 2 and 3; Figure 2). These data support results from other recent clinical trials and naturalistic studies showing that concomitant antidepressant treatment reduces the rate of smoking cessation10–13. Our results also support findings from other naturalistic treatment settings showing that antidepressant use is associated with a lower rate of subsequent smoking cessation, either in a smoking cessation treatment paradigm11, or in a cohort of medically ill outpatients not in treatment for tobacco dependence10. These prior associational findings were ascribed variously to depressive symptoms or amotivation associated with antidepressant treatment; however, we found that baseline depressive symptoms did not differ between quitters and non-quitters, and there was no difference in either time spent in treatment or prevalence of either diagnoses of major depression or bipolar disorders in our cohort (Table 1). Therefore, neither baseline depressive symptoms nor treatment engagement nor psychiatric history are good explanatory factors for the negative effect of antidepressant treatment on smoking cessation quit rate.

Antidepressants reduce smoking cessation treatment efficacy in patients with a history of substance use disorders

Clinical trials of antidepressants for active smokers typically exclude participants with recent history of substance use disorder, and do not keep track of how many have a more remote history of this disorder (e.g.,24). To our knowledge, our current findings represent the first report of the association of reduced smoking cessation efficacy in patients with a history of substance use disorder taking antidepressants. There are currently no accepted theories as to why antidepressant treatment is associated with reduced efficacy of treatment for the underlying substance use disorder (including smoking), but one possible explanation was found in a re-analysis of a placebo controlled trial of sertraline for methamphetamine dependence14, 17. Participants who were taking sertraline demonstrated increased craving and use of methamphetamine, as compared with all other participants14. Therefore, there may be increased craving for tobacco and other substance of abuse with antidepressant treatment. However, further studies are needed to follow up on this preliminary finding, and to better characterize this phenomenon.

Limitations

While our data are compelling, it is important to recognize study limitations. This was a naturalistic chart review study, and therefore is capable only of indicating associations between possible explanatory variables and treatment outcomes, not causative relationships. Our sample of Veterans is mostly male, and thus may not generalize to populations of treatment-seeking female smokers. Furthermore, the sample size was relatively small, especially for subpopulations (e.g., individuals with opiate or cocaine use disorder). Psychiatric disorders (including substance use disorders) were based upon clinician report via electronic records, and therefore may not have been determined with a standard rating scale or standard questions using DSM criteria. There is also a possibility of bias present in the historical information available from electronic medical records about diagnostic histories of the patients by participant reports or treating clinicians’ interpretations. While there is no a priori reason to assume that the pattern of missing information from patients about intake CO, BDI, or FTND levels was anything other than random, this remains a possible source of bias as well.

Conclusions

In our sample of urban Veteran smokers with extensive psychiatric, medical, and substance use disorder comorbidities, antidepressant use was associated with a lower rate of smoking cessation in an outpatient treatment program. By comparison, the same sample did not reveal an effect of baseline depressive symptoms, demographic factors, psychiatric disorders (aside from substance-use disorders), medical conditions (aside from diabetes mellitus), antipsychotic usage, or mood stabilizer usage. This effect of antidepressant use reducing the efficacy of the smoking cessation treatment was primarily seen in patients with a history of substance use disorder. While the underlying cause of this phenomenon remains unknown, these results, taken together with other studies demonstrating a similar effect both in smoking cessation treatment10–13 and in treatment studies for other substances of abuse14–18, indicate a clinically important phenomenon worthy of additional research. If these finding are borne out by future research, then the possible detrimental effects of antidepressants on the ability of patients with a history of substance use disorder to quit smoking should be included in the risk/benefit analysis carried out by treating physicians.

Clinical Points.

Antidepressant treatment is associated with a reduced rate of smoking cessation in a Veteran-based smoking cessation clinic setting.

The detrimental effect of antidepressant treatment on smoking cessation outcome was primarily seen in those patients with a history of substance use disorders.

If these findings are confirmed, clinicians may want to consider the risk of reduced ability to quit smoking in patients with a history of substance use disorder taking antidepressants.

Footnotes

The authors report no financial support for this project.

These data have not previously been reported elsewhere.

No outside assistance was rendered for this study.

The authors report no financial or other relationship relevant to the subject of this article.

Bibliography

- 1.Giovino GA, Mirza SA, Samet JM, et al. Tobacco use in 3 billion individuals from 16 countries: an analysis of nationally representative cross-sectional household surveys. Lancet. 2012 Aug 18;380(9842):668–679. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61085-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prevention USCfDCa. Health effect of cigarette smoking. [cited 2013 October 9];Smoking and tobacco use. 2013 Aug 1; 2013 Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/fact_sheets/health_effects/effects_cig_smoking/index.htm.

- 3.Stead LF, Lancaster T. Combined pharmacotherapy and behavioural interventions for smoking cessation. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2012;10 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008286.pub2. CD008286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gershon Grand RB, Hwang S, Han J, George T, Brody AL. Short-term naturalistic treatment outcomes in cigarette smokers with substance abuse and/or mental illness. The Journal of clinical psychiatry. 2007 Jun;68(6):892–898. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v68n0611. quiz 980–891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mackowick KM, Lynch MJ, Weinberger AH, George TP. Treatment of tobacco dependence in people with mental health and addictive disorders. Current psychiatry reports. 2012 Oct;14(5):478–485. doi: 10.1007/s11920-012-0299-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lasser K, Boyd JW, Woolhandler S, Himmelstein DU, McCormick D, Bor DH. Smoking and mental illness - A population-based prevalence study. Jama-Journal of the American Medical Association. 2000;284(20):2606–2610. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.20.2606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ziedonis D, Hitsman B, Beckham JC, et al. Tobacco use and cessation in psychiatric disorders: National Institute of Mental Health report. Nicotine & tobacco research : official journal of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco. 2008 Dec;10(12):1691–1715. doi: 10.1080/14622200802443569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hitsman B, Papandonatos GD, McChargue DE, et al. Past major depression and smoking cessation outcome: a systematic review and meta-analysis update. Addiction. 2013 Feb;108(2):294–306. doi: 10.1111/add.12009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van der Meer RM, Willemsen MC, Smit F, Cuijpers P. Smoking cessation interventions for smokers with current or past depression. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2013;8 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006102.pub2. CD006102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gravely-Witte S, Stewart DE, Suskin N, Grace SL. The association among depressive symptoms, smoking status and antidepressant use in cardiac outpatients. Journal of behavioral medicine. 2009 Oct;32(5):478–490. doi: 10.1007/s10865-009-9218-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stolz D, Scherr A, Seiffert B, et al. Predictors of Success for Smoking Cessation at the Workplace: A Longitudinal Study. Respiration; international review of thoracic diseases. 2013 Apr 10; doi: 10.1159/000346646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Attebring MF, Hartford M, Hjalmarson A, Caidahl K, Karlsson T, Herlitz J. Smoking habits and predictors of continued smoking in patients with acute coronary syndromes. Journal of advanced nursing. 2004 Jun;46(6):614–623. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03052.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Spring B, Doran N, Pagoto S, et al. Fluoxetine, smoking, and history of major depression: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 2007 Feb;75(1):85–94. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.1.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zorick T, Sugar CA, Hellemann G, Shoptaw S, London ED. Poor response to sertraline in methamphetamine dependence is associated with sustained craving for methamphetamine. Drug and alcohol dependence. 2011 Nov 1;118(2–3):500–503. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pettinati HM. The use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in treating alcoholic subtypes. The Journal of clinical psychiatry. 2001;62(Suppl 20):26–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kranzler HR, Armeli S, Tennen H, et al. A double-blind, randomized trial of sertraline for alcohol dependence: moderation by age of onset [corrected] and 5-hydroxytryptamine transporter-linked promoter region genotype. Journal of clinical psychopharmacology. 2011 Feb;31(1):22–30. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e31820465fa. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shoptaw S, Huber A, Peck J, et al. Randomized, placebo-controlled trial of sertraline and contingency management for the treatment of methamphetamine dependence. Drug and alcohol dependence. 2006 Oct 15;85(1):12–18. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Winstanley EL, Bigelow GE, Silverman K, Johnson RE, Strain EC. A randomized controlled trial of fluoxetine in the treatment of cocaine dependence among methadone-maintained patients. Journal of substance abuse treatment. 2011 Apr;40(3):255–264. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2010.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beck A, Steer R. Manual for BDI-II. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fagerstrom KO. Measuring the degree of physical dependence to tobacco smoking with reference to individualization of treatment. Addictive behaviors. 1978;3:235–241. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(78)90024-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fagiolini A, Comandini A, Catena Dell'Osso M, Kasper S. Rediscovering trazodone for the treatment of major depressive disorder. CNS drugs. 2012 Dec;26(12):1033–1049. doi: 10.1007/s40263-012-0010-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dundon W, Lynch KG, Pettinati HM, Lipkin C. Treatment outcomes in type A and B alcohol dependence 6 months after serotonergic pharmacotherapy. Alcoholism, clinical and experimental research. 2004 Jul;28(7):1065–1073. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000130974.50563.04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pettinati HM, Volpicelli JR, Kranzler HR, Luck G, Rukstalis MR, Cnaan A. Sertraline treatment for alcohol dependence: interactive effects of medication and alcoholic subtype. Alcoholism, clinical and experimental research. 2000 Jul;24(7):1041–1049. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saules KK, Schuh LM, Arfken CL, Reed K, Kilbey MM, Schuster CR. Double-blind placebo-controlled trial of fluoxetine in smoking cessation treatment including nicotine patch and cognitive-behavioral group therapy. The American journal on addictions / American Academy of Psychiatrists in Alcoholism and Addictions. 2004 Oct-Dec;13(5):438–446. doi: 10.1080/10550490490512762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]