There is a significant need to develop an efficient treatment, without sacrificing efficacy, for older fit patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) as fludarabine, cyclophosphamide and rituximab (FCR) have very often led to treatment-related toxicities, causing delay or therapy discontinuation and thus precluding clinical benefits.1,2

Pentostatin is better tolerated and less myelosuppressive than fludarabine when used in combination with cyclophosphamide. Several studies have investigated the role of pentostatin (P) and cyclophosphamide (C) as the backbone of immunochemotherapy in CLL treatment.3–5

We designed this phase II trial (www.clinicaltrials.gov: NCT01681563) using PC chemotherapy in combination with the fully-human anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody ofatumumab (O) specifically designed for untreated CLL fit patients aged ≥65 years.

Patients were required to have a confirmed B-cell CLL showing a progressive disease in need of treatment,6 an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status ≤2, CIRS ≤6 and CrCl ≥70 mL/min. Having provided written informed consent, 47 patients, median age 72 years (range: 65–83), 68% male, were enrolled in the study between September 2011 and May 2013 in 12 Italian centers. Responses were categorized according to the Guidelines of the International Workshop on CLL,6 related adverse effects were graded with the use of the NCI Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) version 4.03.7 In patients achieving a CR, MRD was quantified by four-color flow cytometry on peripheral blood samples collected 3 months after the last course of treatment with a sensitivity of at least (10−4), according to the technique previously described.8 MRD results were categorized into low levels, <10−4 corresponding to “MRD negativity”, and high levels, ≥10−4 corresponding to “MRD positivity”.

The regimen consisted of intravenous pentostatin 2 mg/m2 and cyclophosphamide 600 mg/m2 on day 1 every 3 weeks for a total of 6 courses. On the first course, intravenous ofatumumab was administered at 300 mg on day 1 and 1000 mg on day 8. For the subsequent cycles, patients received ofatumumab on day 1 at the dose of 1000 mg. During the first and second courses, ofatumumab infusion reaction prophylaxis consisted of oral paracetamol 1000 mg, intravenous clorfenamine 10 mg and intravenous prednisolone 50 mg. Pre-medication with glucocorticoid could be reduced or omitted from the third course. Anti-infective prophylaxis consisted of cotrimoxazole 960 mg 3 times a week and acyclovir 400 mg twice a day for up to 3 months following PCO discontinuation. Granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) and erythropoietin were allowed according to the physician’s discretion. The first course of treatment was administered at full doses regardless of pre-existing cytopenias.

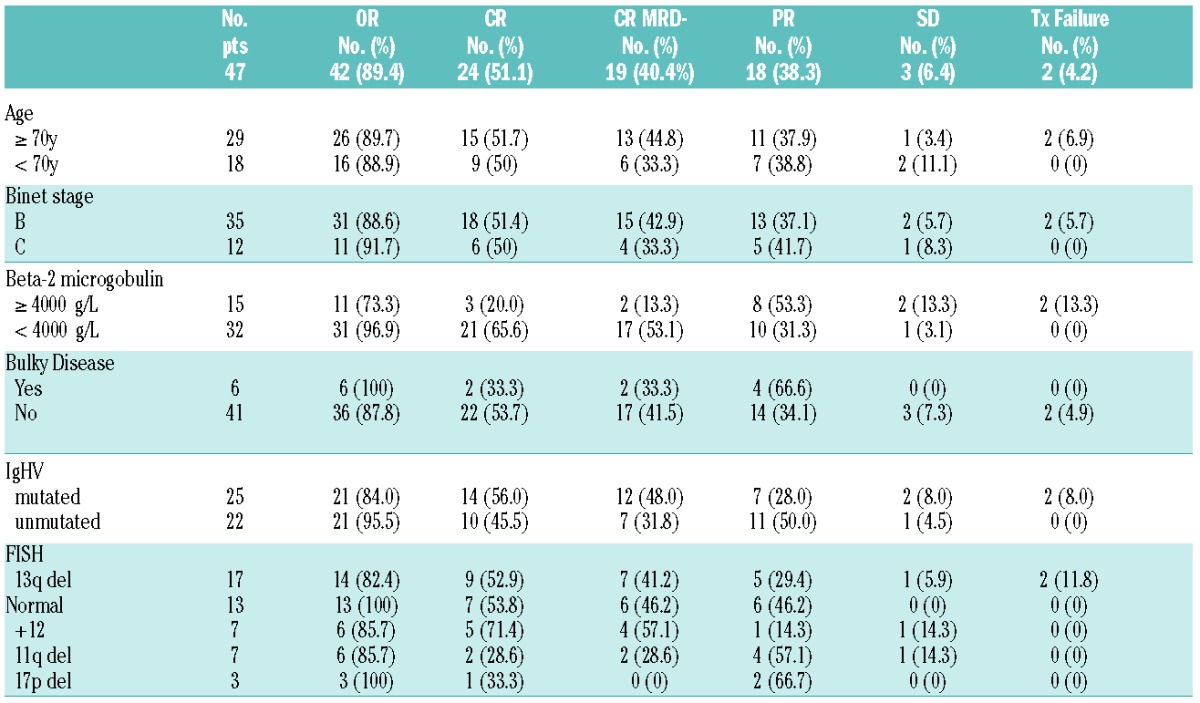

Clinical and disease characteristics are shown in Table 1. Patients received a median of 6 courses of therapy (range: 2–6), with 44 (94%) completing the intended treatment. 3 patients discontinued treatment: 2 cases, considered as treatment failures at the final evaluation, received only 2 courses as they developed acute renal failure and septic shock, respectively. In one case treatment was withheld after 5 courses due to persisting skin rash. On an intention-to-treat analysis, ORR resulted as 89.4% (95% CI, 80.9 % to 97.9%), with 24 (51.1%) CRs, including 6 CRi (12.8%), and 18 (38.3%) PRs. Responses according to clinical and biological disease characteristics are shown in Table 1. None of the prognostic and clinical features considered significantly impacted on OR attainment, Β2MG ≥4000 μg/L was the only characteristic influencing the achievement of a lower CR rate (P=0.003).

Table 1.

Responses after PCO according to clinical and biological characteristics.

Among the 24 CR patients, 19 (79%) reached MRD negativity. Overall 40.4% of all patients enrolled in the study obtained a MRD negative CR status at final restaging. Patients presenting with a lower B2MG level had a trend toward a higher chance of achieving MRD negativity (54.8% versus 18.2%, P=0.06). None of the other prognostic features associated with a negative MRD.

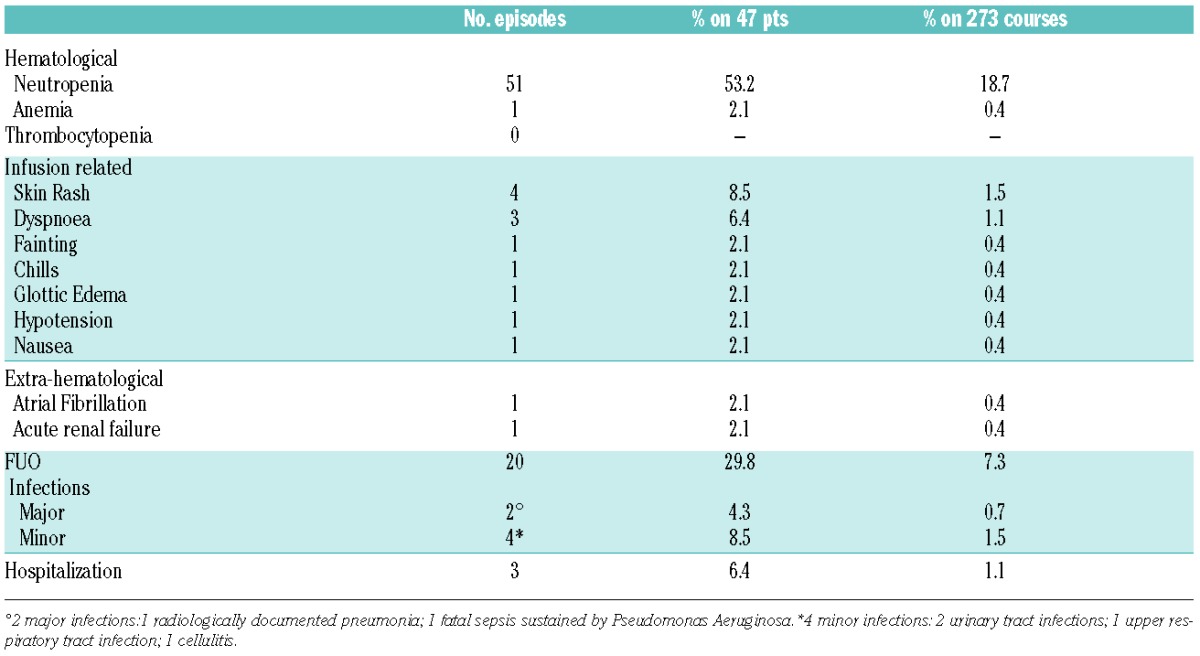

Overall 273 PCO courses were administered, adverse events are listed in Table 2. Neutropenia was the major cause of treatment delay or chemotherapy dose reduction, occurring in 9.9% and 4% of courses, respectively. G-CSF, either as prophylaxis or to treat neutropenia, was administered for a median of 3 days (3–6) in 74 courses (27.1%). After the last course of treatment, five patients showed a delayed onset neutropenia lasting a median of 1 month (range: 1–9), resolving in all cases. Development of neutropenia, treatment delay and/or discontinuation were not influenced by age or any of the patients clinical characteristics.

Table 2.

Grade 3–4 toxicity and infections.

Median PFS of all enrolled patients has not been reached after a median follow-up of 22 months, 2-year PFS resulted as 69% (95% CI, 50.95% to 81.33%). We observed one treatment related death with a 2-year OS of 97.9%. 9 (21%) of the 42 responding patients progressed after a median of 15 months (range: 9–27). In 6 of them at least one adverse prognostic feature was recorded (6 unmutated, 3 del 17p)

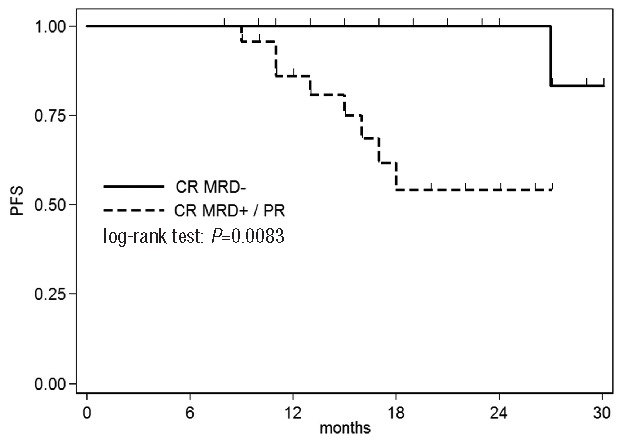

The only pre-treatment feature significantly associated with a shorter PFS was a B2MG ≥4000 μg/L (median 15 months vs. n.r. P=0.008). PFS resulted significantly longer in patients reaching MRD negativity (P=0.008) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Progression-free survival according to response and MRD status.

During follow-up 2 cases developed a myelodysplastic syndrome, following treatment completion in one case and after 15 months in the other case. PC based immunochemotherapy studies in treatment-naïve patients demonstrated that these combinations are as effective as FCR in terms of response attainment.3,5 It is noteworthy that PCR led to a similar clinical benefit when comparing younger to older patients (ORR 93% versus 83%, CR 41% versus 39%). In this study we confirm the good tolerability and efficacy of PC in combination with ofatumumab even in an elderly CLL population. Treatment was completed in the majority of patients (94%) with no difference when patients were categorized according to age. The enhanced tolerability of the therapy is also confirmed by the low rate of treatment delay (9.9% of cycles) and need for dose reduction (4%). FCR administration in the CLL 8 trial, in a relatively young and fit population, led to a high rate (26%) of patients not completing the intended 6 courses with dose reductions, more than 10% in 47% of patients.1 Furthermore the MDACC study experience revealed that early discontinuation and long-term cytopenias were significantly associated with an age >65 years.2 The enhanced tolerability of PCO enabled us to preserve the dose intensity allowing for the attainment of similar results, even in terms of CR, observed in the elderly treated with FCR both in the CLL 8 and MDACC trials.1,9

It should be emphasized that the addition of ofatumumab, with its ability to promote CDC, allowed a significant proportion of patients to achieve not only a high CR rate, but also a MRD negative CR. It is difficult to compare MRD results among trials as methods, time points and sample sources differ widely across studies. It is well known that MRD is a key factor for durable remission and Böttcher et al. demonstrated that the profound reduction of tumor load, regardless of treatment regimen, represents the most important prognostic feature.10 In our series we confirm the prognostic value of MRD level as PFS showed a clear difference (P=0.008) when patients were categorized according to their MRD status.

Bendamustine could represent a suitable alternative to more intensive schedules for treatment-naïve elderly patients, even though there are no prospective clinical trials specifically addressing the role of bendamustine in combination with anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies in this setting. A subanalysis of the older population (>70 years) enrolled in a study by Fisher et al. in which bendamustine was administered at 90mg/m2, showed that a low CR rate was attained (11.5%) with a significantly higher incidence of non-hematologic toxicity when compared to younger patients.11 Similarly, in a retrospective Italian trial the same bendamustine dosage had to be reduced in 55.7% of patients aged ≥65 years due to hematological toxicity.12

To ameliorate tolerability in elderly patients with coexisting comorbidities and/or not suitable for purine analogs, chlorambucil-based approaches have been evaluated.13,14 The addition of either rituximab, ofatumumab or obinutuzumab to chlorambucil translates into a superior CR rate and prolongation of PFS when compared to monotherapy alone. Furthermore, the combination of anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies with chlorambucil allowed patients to obtain a negative MRD in bone marrow and peripheral blood.13,14 In respect to patients enrolled in these studies our population showed a reduced number of comorbidities, but median age was very similar. As expected, PCO, which may be considered a more intensive treatment, led to a better quality of responses and allowed for the attainment of higher MRD negative CRs, resulting in a better clinical outcome. Notably, this more intensive treatment did not exert an increased incidence of infections or grade 3–4 neutropenia.

Inhibitors of kinases downstream of the B-cell receptor and the selective B-cell lymphoma antagonist represent a novel class of drugs whose mechanisms of action are different from traditional cytotoxic agents and antibodies. Emerging data on these therapies, showing impressive results on relapsed/refractory CLL and their ability to overcome the negative impact of adverse prognostic factors, challenge the standard front-line treatment.15 Moreover, the low degree of myelosuppression reported along with the low levels of non-hematological toxicities, make these agents useful, primarily in elderly patients. In seeking to eliminate chemotherapy from the initial treatment approach, a number of studies are continuing to combine them with other non-cytotoxic agents. However, the clinical advantage of these combinations needs to be consistently proven because of the relevant economic consequences that might preclude the overall sustainability of such treatments.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Clinical Organization for Strategies & Solutions Company for data management and MRD analysis.

Footnotes

Funding: this study was conducted with a grant from the “Fondazione Regionale per la Ricerca Biomedica” of the Region of Lombardy.

EUDRACT no. 2010-022332-37CLIN GOV n° NCT01681563.

Information on authorship, contributions, and financial & other disclosures was provided by the authors and is available with the online version of this article at www.haematologica.org.

References

- 1.Hallek M, Fischer K, Fingerle-Rowson G, et al. ; International Group of Investigators; German Chronic Lymphocytic Leukaemia Study Group. Addition of rituximab to fludarabine and cyclophosphamide in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2010;376(9747):1164–1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Strati P, Wierda W, Burger J, et al. Myelosuppression after frontline fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia: analysis of persistent and new-onset cytopenia. Cancer. 2013;119(21):3805–3811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kay NE, Geyer SM, Call TG, et al. Combination chemoimmunotherapy with pentostatin, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab shows significant clinical activity with low accompanying toxicity in previously untreated B chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2007; 109(2):405–411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shanafelt TD, Lin T, Geyer SM, et al. Pentostatin, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab regimen in older patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Cancer. 2007;109(11):2291–2298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shanafelt T, Lanasa MC, Call TG, et al. Ofatumumab-based chemoimmunotherapy is effective and well tolerated in patients with previously untreated chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL). Cancer. 2013;119(21):3788–3796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hallek M, Cheson BD, Catovsky D, et al. ; International Workshop on Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a report from the International Workshop on Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia updating the National Cancer Institute-Working Group 1996 guidelines. Blood. 2008;111(12):5446–5456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) Version 4.0 Published: May 28, 2009 (v4.03: June 14, 2010). U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES. National Institutes of Health National Cancer Institute.

- 8.Rawstron AC, Villamor N, Ritgen M, et al. International standardized approach for flow cytometric residual disease monitoring in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Leukemia. 2007;21(5);956–964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tam CS, O’Brien S, Wierda W, et al. Long-term results of the fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab regimen as initial therapy of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2008;112(4):975–980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Böttcher S, Ritgen M, Fischer K, et al. Minimal residual disease quantification is an independent predictor of progression-free and overall survival in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a multivariate analysis from the randomized GCLLSG CLL8 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2012; 30(9):980–988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fischer K, Cramer P, Busch R, et al. Bendamustine in combination with rituximab for previously untreated patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia: A multicenter phase II trial of the German Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(26):3209–3216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Laurenti L, Autore F, Innocenti I, et al. Bendamustine with rituximab is safe and effective as front line therapy in elderly B-CLL patients. An Italian retrospective multicenter experience. Blood. 2013;122(21): Abstract 5309. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hillmen P, Robak T, Janssens A, et al. COMPLEMENT 1 Study Investigators. Chlorambucil plus ofatumumab versus chlorambucil alone in previously untreated patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (COMPLEMENT 1): a randomised, multicentre, open-label phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2015;385(9980):1873–1883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goede V, Fischer K, Busch R, et al. Obinutuzumab plus chlorambucil in patients with CLL and coexisting conditions. N Eng J Med. 2014;370(12):1101–1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Woyach JA, Johnson AJ. Targeted therapies in CLL: mechanisms of resistance and strategies for management. Blood. 2015;126(4):471–477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]