Abstract

Background

Acquired heart diseases (AHD) in children cause significant morbidity and mortality especially in low resource settings. There is limited description of acquired childhood heart diseases in Cameroon, making it difficult to estimate its current contribution to childhood morbidity and mortality. Echocardiography is the main diagnostic modality in low resource settings and has a key role in the characterization and management of these disorders. We aimed to determine the prevalence and spectrum of AHD in children in Yaoundé-Cameroon, in an era of echocardiography. These data are needed for health service and policy formulation.

Methods

Echocardiography records from August 2003 to December 2013 were reviewed. Echocardiography records of children ≤18 years with an echocardiographic diagnosis of a definite AHD were identified and relevant data extracted from their records.

Results

One hundred and fifty eight children (13.4%) ≤18 years had an AHD. The mean [± standard deviations (SD)] age was 11.9 (±4.4) years .The most common affected age group was 15-18 years (36.1%). Heart failure (20.3%), suspicion of rheumatic heart disease (RHD) (12.0%) and the presence of a heart murmur (8.9%) were the most common indications for echocardiography. RHD (41.1%), pericardial disease (25.3%), dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) (15.8%) and endomyocardial fibrosis (EMF) (13.9%) were the most common AHD. Cor pulmonale was rare (1.3%). Fifty-seven (87.7%) children with RHD had mitral regurgitation alone or in combination with other heart valve lesions and 63.3% of the lesions were severe.

Conclusions

RHD remains the most common AHD in children in this setting and is frequently severe. Multicenter collaborative studies will help to better describe the pattern of AHD and there should be a renewed focus on the prevention of RHD.

Keywords: Acquired heart disease (AHD), children, sub-Saharan Africa, Cameroon

Introduction

Acquired heart diseases (AHD) in children are still a major cause of significant morbidity and mortality in developing countries especially in Africa where the epidemiologic factors responsible for many are still prevalent (1,2). The spectrum of AHD in children varies in different regions of the world and there have been significant changes in the epidemiology of AHD in children in the past decades. In developed nations, Kawasaki’s disease appears to have replaced rheumatic heart disease (RHD) as the most common AHD in children, while in resource limited regions of the world, RHD prevails as the most common AHD (3,4). Preventive measures, based mainly on penicillin use and associated with economic and social development, are very efficient and have nearly eradicated RHD in developed countries. In Nigeria, reports dating back three or four decades indicated that “idiopathic cardiomegaly”, endomyocardial fibrosis (EMF), RHD and infective pericarditis were the most commonly encountered AHD among children (5). However, recent reports still in Nigeria indicate that EMF may be disappearing (6,7). The advent of echocardiography has afforded a better and more accurate diagnosis of cardiac diseases, thus accurate prevalence and better description of cardiac diseases that were once suspected or thought to be rare in developing countries are now available. Data on the spectrum of AHD in children in Cameroon is limited. In Cameroon, a retrospective study in the University Teaching Hospital of Yaoundé dating back to two decades showed that AHD accounted for 42.7% of heart diseases in children and RHD was the most common AHD accounting for 70% of the cases (8). Although studies on the pattern of AHD in children have been done in some African countries, there is scarcity of contemporary data in Cameroon with the changing epidemiology of AHD.

Echocardiography plays a major role in accurate diagnosis and management of these disorders. It is the main diagnostic modality for cardiac diseases in our setting. The objective of this 11-year review was to determine the contemporary prevalence and echocardiographic pattern of AHD in children in a major cardiac referral hospital in the capital city of Cameroon. The data is important to inform management and prevention strategies.

Methods

Study setting

The study was conducted in the echocardiography department of the Yaoundé General Hospital, a major cardiac referral centre in the capital city of Cameroon with a population of about 2 million inhabitants. The hospital receives referrals from other health institutions for the investigation and/or management of suspected heart disease.

Recruitment and data collection

All pediatric echocardiographies over an 11-year period from August 2003 to December 2013 were reviewed. Children with definite diagnosis of AHD based on standard guidelines were included.

Echocardiographic examination was performed in the parasternal long axis, short axis, and apical four chambers and in the subcostal and suprasternal views. Indices analyzed included the left ventricle end systolic diameter (LVESD), left ventricle end diastolic diameter (LVEDD) and the ejection fraction (EF). Children were included if they were less than or equal to 18 years old. Information obtained from the register included age at the time of echocardiography, gender, clinical indication for the echocardiography, and the echocardiography findings and diagnosis. Echocardiographic diagnoses were based on standard guidelines and on the diagnostic criteria for each AHD. Repeated studies and isolated congenital heart diseases were excluded.

RHD was defined by the world heart federation criteria by the presence of any definite evidence of valve regurgitation or stenosis seen in two planes on Doppler examination, and at least two morphologic abnormalities, such as restricted leaflet mobility, focal or generalized valvular thickening, and abnormal subvalvular thickening of the affected valve (9).

Dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) was diagnosed in the presence of poor left ventricular (LV) contractility (fractional shortening less than 28%), and if the LV dimensions were above the upper limit of normal for age (10). Non-dilated cardiomyopathy (NDCM) was diagnosed if the LV dimensions were within normal limits for age with poor LV contractile function (11).

Pericardial effusion was diagnosed when there was an echo free space between the visceral and parietal pericardium. EMF was diagnosed in the presence of a small ventricle with obliteration of the apex and a large atrium in two-dimensional echocardiography. Cor pulmonale was diagnosed in the presence an alteration in the structure or function of the right ventricle without evidence of left heart disease (12). Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy was diagnosed when there was asymmetrical septal hypertrophy and septal disorganization on M-mode (10). Other diagnoses were based on standard echocardiographic findings.

The study was approved by the institutional review board of Yaoundé General Hospital, Cameroon.

Statistical analysis

The data collected was analyzed using SPSS version 20 for windows. Descriptive statistics including means, standard deviations (SD), and frequencies were generated and stratified by age, gender, and heart lesions as appropriate. Means of continuous variables were compared using student’s t-test while proportions were compared using the Chi-square test. A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

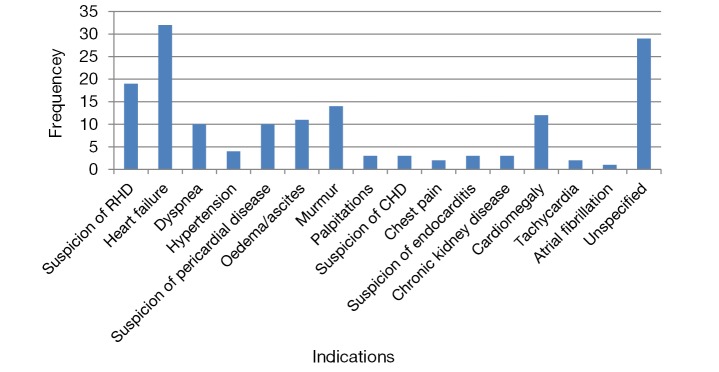

A total of 9,777 echocardiographic examinations were performed over the 11-year period of the study including 4,600 (47.1%) male participants. There were 1,178 children ≤18 years with a suspicion of heart disease, with 158 (13.4%) children having a definite AHD. Out of the 158 children with AHD, 79 (50%) were males. The mean (± SD) age of the children was 11.9 (±4.4) years. The most common affected age group was children aged between 15-18 years (36.1%) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Distribution of children with acquired heart disease by age and sex.

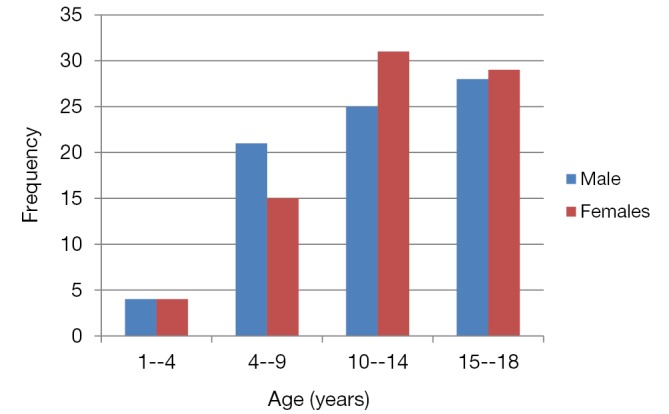

Indications of echocardiography

The most common clinical indication and referral for echocardiography was heart failure (20.3%), suspicion of RHD (12%), and the presence of a heart murmur on clinical examination (8.9%) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Indications of echocardiography in children identified with acquired heart disease. RHD, rheumatic heart disease.

Types of acquired heart disease (Table 1)

Table 1. Type of acquired heart disease by age group.

| Heart diseases | Frequency (%) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0-4 years | 5-9 years | 10-14 years | 15-18 years | Total | |

| Rheumatic heart disease | 1 (1.5) | 17 (26.2) | 32 (49.2) | 15 (23.1) | 65 (41.1) |

| Pericardial disease* | 3 | 10 | 12 | 15 | 40 (25.3) |

| Dilated cardiomyopathy | 4 | 4 | 5 | 12 | 25 (15.8) |

| Endomyocardial fibrosis | 0 | 4 | 9 | 9 | 22 (13.9) |

| Hypertensive heart disease | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 (1.9) |

| Cor pulmonale | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 (1.3) |

| Endocarditis | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 (1.9) |

| Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 (1.9) |

| NDCM | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 3 (1.9) |

| Total | 9 | 38 | 61 | 58 | 166 |

*, eight cases of pericardial disease were associated with other forms of AHD (3 EMF, 1 RHD, 3 DCM, 1 NDCM) which accounts for the excess. NDCM, Non-dilated cardiomyopathy; AHD, acquired heart diseases; EMF, endomyocardial fibrosis; RHD, rheumatic heart disease; DCM, dilated cardiomyopathy.

Rheumatic heart disease (RHD)

Overall, the most common AHD was RHD accounting for 41.1% of all cases. Fifty-seven (87.7%) children with RHD had mitral regurgitation alone or in combination with other valve lesions. The mitral valve was the commonest affected valve in 57 (92%) children. Twenty-six children (42%) had a combination of mitral and aortic valve involvement. The most common echocardiographic diagnosis was pure mitral regurgitation present in 29 (44.6%) children, followed the association of mitral and aortic regurgitation in 23 (35.4%) children. No child was found to have an abnormal morphology (thickening) of the tricuspid valve or pulmonary valve. The tricuspid regurgitation reported in 6 (9.2%) children was functional. Thirty eight (63.3%) of the children with RHD had severe lesions.

Pericardial effusion

This was the second most common AHD occurring in 40 (25.3%) children. Eight cases of pericardial disease were associated with other forms of heart diseases. The pericardial disease consisted of pericardial effusions with no direct pointers to possible etiologies.

Cardiomyopathies

DCM was the third most common AHD found in 25 (15.8%) children. Three children (1.9%) had non dilated but poorly contractile left ventricles consistent with NDCM. DCM was most common in the 15-18 years age group.

Other acquired heart diseases (AHD)

Other diagnosed AHD included EMF and infective endocarditis in 22 (13.9%) and 3 (1.9%) children respectively. The three children with infective endocarditis had visible vegetations all on the mitral valve. Cor pulmonale was diagnosed in 2 (1.3%) children. The etiology of cor pulmonale could not be ascertained. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and hypertensive heart disease were both diagnosed in 3 (1.9%) children. The children with hypertensive heart disease were patients with secondary hypertension due to chronic kidney disease.

Discussion

In this study covering more than a decade of activities in a major referral echocardiography laboratory in Cameroon, we have reported the contemporary pattern of AHD in children. We found that RHD remains the most common AHD in children ≤18 years, representing about 41% of AHD in the pediatric population, followed by pericardial disease, DCM and EMF respectively. Heart failure and clinical suspicion of RHD were the most common indications or reasons for referral for cardiac echography. Although based only on patients that came to specialist medical attention and thus not representative of the community prevalence of the various AHD in the region, our data nevertheless provide contemporary insight in era of echocardiography into the types of AHD common among children in this urban setting. Like Bode-Thomas et al. in Nigeria, we found more girls than boys with AHD (13).

Rheumatic heart disease (RHD)

An earlier study in the Yaoundé University teaching hospital done about two decades ago found that AHD accounted for 42.7% of heart diseases in children with RHD representing 70% of the cases (8). Although RHD disease remains the most frequent AHD in children in this study, our study found a lower prevalence of RHD than that reported by Abena-Obama et al. (8). It is not clear whether this lower proportion of RHD is due to a decline in the prevalence of RHD. The improvement in the living condition of the population could be one of the factors that account for this decline. A similar declining trend in RHD has been observed in Nigeria. In a recent echocardiographic study in Nigeria, the proportion of RHD was 17.4% (14) which was lower than the 68% obtained among children in Jos (7), the 35.8% obtained in Ibadan (5), and the 26.8% obtained in Lagos (6). However, in another study Bode-Thomas et al. (13) found that the prevalence of AHD in children ≤18 years in Jos was 28.8% with RHD disease representing a significantly higher proportion (57.7%) of the cases. A report from Nigeria reported effusive pericarditis to be the most frequent AHD in children with RHD the second most frequent (15). Despite these differences in the proportion of RHD reported in the various studies in the Sub region, RHD remains a significant cause of morbidity in children in Sub-Saharan Africa. It was the most common cause of heart failure in children in a rural area in Cameroon (16). In contrast to developed countries, where there is an improvement in the living condition of the population, Kawasaki disease has replaced RHD as the most common AHD in children (3). We did not report any case of Kawasaki’s disease contrary to some studies in Nigeria (13,14). This could be suggestive of the rarity of Kawasaki’s disease in our milieu or of a low index of suspicion by physicians. The proportion of RHD reported here may not reflect the true epidemiology of RHD in the community as only symptomatic patients are likely to seek medical care and hence an echocardiographic examination. Thus, milder cases may not be captured in a hospital based study.

The age range of children with RHD is similar to that reported by other studies in Africa (13). The most common valvular involvement in children with RHD was isolated mitral regurgitation followed by a combination of mitral and aortic regurgitation. Similar patterns have been reported from other parts of Africa (13,17). The tricuspid and the pulmonary valves were not involved in our study. Mitral stenosis was rare.

Pericardial effusion

Pericardial disease was the second most common AHD in our study, frequently associated with other cardiac conditions and presenting as pericardial effusion. This is similar to a previous study in Nigeria by Wilson et al. (14). However, a similar study reported a relatively lower prevalence (13) and Asani et al. reported no cases of pericardial disease (18). We could not ascertain the etiology of pericardial effusion in our study as no pericardial fluid aspiration was performed. In a study in Nigeria, the authors reported mycobacterium tuberculosis and staphylococcus aureus as the most common causes of pericarditis in children (19).

Dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM)

DCM ranked third as a cause of AHD in children similar to a recent report in Nigeria (15). Whereas in an earlier report, it was the least common AHD in children (5). The etiology of DCM was not ascertained but it is widely accepted that most cases of DCM in children are secondary to myocarditis (20). With limited diagnostic possibilities it is usually difficult to ascertain the etiology of DCM in resource limited settings like ours but studies from developed countries suggest that most cases are due to viral infections (20).

Endomyocardial fibrosis (EMF)

EMF was found in 13.9% of children with AHD in this study. This contrasts with some Nigerian studies that reported a lower prevalence of EMF. A report by Akinwusi et al., in which patient records from a teaching hospital in southwest Nigeria were reviewed, found that the disease had a prevalence of just 0.02% among medical patients in general and 0.04% among cardiac cases specifically, between January 2003 and December 2009 (21). This was a considerable reduction from the 10% prevalence among cardiovascular cases in southwest Nigeria in the 1960s and 1970s. Similarly; other authors in Nigeria have suggested that there might be a decline in the proportion of EMF among children with AHD in Nigeria (6,22). The authors suggested that EMF may be disappearing in Nigeria due to improved sanitation and health education in the country. We could not find an explanation for this higher proportion of EMF in our study. This may suggest that EMF is still a common AHD in children in our setting. Community based studies are thus needed to throw more light on the true burden of the disease.

Other acquired heart diseases (AHD)

Hypertensive heart disease, infective endocarditis, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and non-dilated cardiomyopathy were each reported in 1.9% of the children. The children with hypertensive heart disease were patients with chronic kidney disease and secondary hypertension. The low proportion of endocarditis has been reported in other similar studies in Nigeria. No underlying heart disease was reported in children with endocarditis as reported in other studies (13). The rarity of NDCM in our study probably reflects the rarity of this heart lesion as reported in other studies (6,18).

Cor pulmonale was also rare in our study, present in only 2 (1.3%) children. This is similar to previous studies in Nigeria where the authors reported fewer cases of cor pulmonale (5,6). However, Bode-Thomas et al. reported a prevalence of 8.7% in a recent report in Nigeria with diverse causes of cor pulmonale (13). We could not ascertain the causes of cor pulmonale in our cohort.

Limitations and strengths

Our study is a hospital based retrospective analysis hence subject to bias. Children diagnosed with RHD may be those with symptomatic disease hence more likely to seek medical attention. Thus our results may not reflect the true burden of RHD in the general population. Furthermore, we could not ascertain the exact etiology of the other AHD. Despite these shortcomings, our study is one of the few contemporary studies that have looked at the spectrum of AHD in children in this resource limited setting with the changing epidemiology of AHD in children worldwide. Furthermore, our study has covered a long period of observation, thus likely to provide reliable estimates of the burden of AHD in children in this urban setting.

Conclusions

RHD remains the most common AHD in children in our setting and is frequently severe. There should be a renewed focus on RHD prevention and increased assessment to cardiac surgery for affected children. Multicenter collaborative studies will help to better describe the pattern of AHD in children and guide in health service and policy formulation.

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.The World Health Organization Global Programme for the Prevention of RF/RHD. Report of a Consultation to Review Progress and Development Activities. Geneva, WHO: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Essop MR, Nkomo VT. Rheumatic and nonrheumatic valvular heart disease: epidemiology, management, and prevention in Africa. Circulation 2005;112:3584-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rowley AH, Shulman ST. Kawasaki syndrome. Clin Microbiol Rev 1998;11:405-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carabello BA. Modern management of mitral stenosis. Circulation 2005;112:432-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jaiyesimi F. Acquired heart disease in Nigerian children: an illustration of the influence of socio-economic factors on disease pattern. J Trop Pediatr 1982;28:223-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Okoromah CA, Ekure EN, Ojo OO, et al. Structural heart disease in children in Lagos: profile, problems and prospects. Niger Postgrad Med J 2008;15:82-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bode-Thomas F, Okolo SN, Ekedigwe JE, et al. Paediatric Echocardiography in Jos University Teaching Hospital: Problems, Prospects and Preliminary Audit. Niger J Paediatr 2003;30:143-9. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abena-Obama MT, Muna WFT, Leckpa JP, et al. Cardiovascular disorders in sub-Saharan African children: a hospital-based experience in Cameroon. Cardiologie trop 1995;21:5-11.

- 9.Reményi B, Wilson N, Steer A, et al. World Heart Federation criteria for echocardiographic diagnosis of rheumatic heart disease--an evidence-based guideline. Nat Rev Cardiol 2012;9:297-309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Snider R. The normal echocardiographic examination. In: Snider RA, Ritter SB, Serwer GA. Echocardiography in paediatric heart disease. 2 edition. United States of America: Walsworth; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Okeahialam BN, Anjorin FI. Non-dilated cardiomyopathy in Nigerians evaluated by echocardiography. Acta Cardiol 1998;53:97-100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kang TK, Park WH. Comparison of Noninvasive Criteria for Diagnosing Cor Pulmonale - With Particular Reference to Comparison of Electrocardiogrhphic Diagnostic Criteria and Echocardiographic Diagnostic Criteria. JCU 1999;7:63-74. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bode-Thomas F, Ige OO, Yilgwan C. Childhood acquired heart diseases in Jos, north central Nigeria. Niger Med J 2013;54:51-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wilson SE, Chinyere UC, Queennette D. Childhood acquired heart disease in Nigeria: an echocardiographic study from three centres. Afr Health Sci 2014;14:609-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bode-Thomas F, Ebonyi AO, Animasahun BA. Childhood dilated cardiomyopathy in Jos, Nigeria. Sahel Med J 2005;8:100-5. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tantchou Tchoumi JC, Butera G. Profile of cardiac disease in Cameroon and impact on health care services. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther 2013;3:236-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Danbauchi SS, David SO, Wammanda R, et al. Spectrum of rheumatic heart disease in Zaria, northern Nigeria. Ann Afr Med 2004;3:17-21. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Asani MO, Sani MU, Karaye KM, et al. Structural heart diseases in Nigerian children. Niger J Med 2005;14:374-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jaiyesimi F, Abioye AA, Antia AU. Infective pericarditis in Nigerian children. Arch Dis Child 1979;54:384-90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gardiner JH, Keith JD. Prevalence of heart disease in Toronto children; 1948-1949 cardiac registry. Pediatrics 1951;7:713-21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Akinwusi PO, Odeyemi AO. The changing pattern of endomyocardial fibrosis in South-west Nigeria. Clin Med Insights Cardiol 2012;6:163-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ike SO, Onwubere BJC, Anisiuba BC. Endomyocardial Fibrosis: Decreasing Prevalence Or Missed Diagnoses? Niger J Clin Pract 2003;6:95-8. [Google Scholar]