Abstract

Context

Palliative care, including symptom management and attention to quality of life (QOL) concerns, should be addressed throughout the trajectory of a serious illness such as lung cancer.

Objectives

This study tested the effectiveness of an interdisciplinary palliative care intervention for patients with stage I–IV non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC).

Methods

Patients undergoing treatments for NSCLC were enrolled in a prospective, quasi-experimental study whereby the usual care group was accrued first followed by the intervention group. Patients in the intervention group were presented at interdisciplinary care meetings, and appropriate supportive care referrals were made. They also received four educational sessions. In both groups, QOL, symptoms, and psychological distress were assessed at baseline and 12 weeks using surveys which included the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Lung and the lung cancer subscale, the 12-item Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Spiritual Well-Being, and the Distress Thermometer.

Results

A total of 491 patients were included in the primary analysis. Patients who received the intervention had significantly better scores for QOL (109.1 vs. 101.4; P<0.001), symptoms (25.8 vs. 23.9; P<0.001) spiritual well-being (38.1 vs. 36.2; P=0.001), and lower psychological distress (2.2 vs. 3.3; P<0.001) at 12 weeks, after controlling for baseline scores, compared to patients in the usual care group. Patients in the intervention group also had significantly higher numbers of completed advance care directives (44% vs. 9%; P<0.001), and overall supportive care referrals (61% vs. 28%; P<0.001). The benefits were seen primarily in the earlier stage patients versus those with stage IV disease.

Conclusion

Interdisciplinary palliative care in the ambulatory care setting resulted in significant improvements in QOL, symptoms, and distress for NSCLC patients.

Keywords: lung cancer, palliative care, quality of life, symptoms, distress, interdisciplinary care

Introduction

Palliative care supports the best possible quality of life (QOL) for patients with serious and complex illnesses such as lung cancer. While advancements in the treatment of lung cancer have been made over the past decade,1 it remains the leading cause of cancer death in the United States, with an estimated five-year survival rate of 16.6% for all stages.2 Lung cancer is often diagnosed at advanced stages of disease that are associated with poor prognosis and high symptom burden, impacting functional status and QOL.3 For early stage patients, symptom burden and significant decreases in QOL also are observed.4,5

The National Quality Forum’s Consensus Report defines palliative care as patient and family-centered care that optimizes QOL by anticipating, preventing, and treating suffering.6 Palliative care should be provided and coordinated by an interdisciplinary team (IDT), and services should be available concurrently with curative or life-prolonging treatments.7 Several published studies confirm the benefits of concurrent palliative care on QOL and survival in cancer patients. Temel and colleagues demonstrated that patients with metastatic non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) who received concurrent, early palliative care and disease-focused therapies reported better QOL, lower depressive symptoms, and longer survival compared to patients who received disease-focused therapies only.8 The Project ENABLE II randomized trial found that a nurse-led concurrent palliative care intervention improved the QOL and mood of patients with advanced gastrointestinal, lung, genitourinary, or breast cancer.9 Several other palliative care trials published over the last 10 years observed better patient satisfaction,10,11 improved QOL in family caregivers,12 improved symptom relief,13 and lower health care costs.10,11 The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) issued a Provisional Clinical Opinion with recommendations that all cancer patients with metastatic disease and/or high symptom burden be given concurrent palliative and oncology care.14

Although palliative care should be integrated for patients across all stages of disease,15,16 most published trials have focused on cancer patients with metastatic disease. Previous studies have often not specified the elements of the intervention, leading to questions about what is in “the black box” of palliative care. The purpose of the current study was to test the effect of a concurrent interdisciplinary palliative care intervention in stage I–IV NSCLC patients. We hypothesized that patients who received the intervention would report improved QOL, improved symptom relief, and lower psychological distress compared to the control (usual care) group.

Methods

Study Design

The study was a prospective, quasi-experimental trial of an interdisciplinary palliative care intervention for patients with NSCLC. Patients were sequentially enrolled into the control and intervention groups. This design was selected to eliminate the potential of contamination or crossover effect for both patients and physicians, which may result in biased estimates of the treatment effect. All patients completed written informed consent prior to enrollment. Patients in the control group were enrolled between November 2009 and December 2010, and intervention group enrollment occurred between July 2011 and August 2014. Data collection for all outcomes ended in September 2014. The study was conducted through a National Cancer Institute-supported Program Project (P01), with patients enrolled into two projects based on stage of disease (early versus late), and one project dedicated to intervention for family caregivers. This manuscript presents findings from the projects which focused on patients. The study protocol and procedures were approved by the City of Hope Institutional Review Board.

Patients

Patients treated in the outpatient thoracic surgery and medical oncology clinics were invited to participate in the study by their treating physicians. Written informed consents were obtained. Patients were eligible for study participation if they had pathologically confirmed stage I–IV NSCLC, were scheduled to undergo treatments at the City of Hope, and were able to read and understand English. Patients diagnosed with Stage I–IIIB disease were enrolled into the Early Stage project, and those with Stage IV disease were enrolled into the Late Stage project.

Intervention

The interdisciplinary palliative care intervention integrated recommendations from the National Consensus Project’s Clinical Practice Guidelines for Palliative Care.7 The intervention consisted of three key components. First, a nurse completed a comprehensive baseline assessment, including QOL, symptoms, and psychological distress. The assessment was transferred to a personalized palliative care plan, and categorized into the physical, psychological, social, and spiritual domains of QOL. Second, patients were presented at weekly IDT meetings, and case presentations were guided by the comprehensive QOL assessment as documented in the palliative care plan. The IDT comprised nurses, palliative medicine physicians, thoracic surgeons, medical oncologists, geriatric oncologist, pulmonologist, social worker, chaplain, dietitian, and physical therapist. Based on the assessment as provided through case presentations, recommendations were made for palliative care consultations and/or referrals to supportive care services (such as social work, chaplaincy, etc.). The treating oncologist approved all recommendations and initiated all consultations and referrals. A total of 139 IDT meetings were conducted between July 2011 and August 2014. On average, each case presentation lasted 20 minutes.

Third, the patients received four educational sessions, where content was organized around the physical, psychological, social, and spiritual domains of QOL. Patients were given an educational manual containing content organized by the QOL domains. Patients were presented with a list of common QOL topics, and were given the opportunity to select the topics that they were interested in discussing. This provided for tailoring of the content to the patient’s needs and preferences. The nurse also discussed any relevant supportive care resources that were identified and recommended by the IDT. Mean length of the educational sessions was 36 minutes. Two hundred forty-four of the 272 intervetion subjects (90%) completed all four teaching sessions. The baseline assessment was done in the clinic setting and the educational sessions were held in the place preferred by the patient, either in the clinic or by phone. Patients in the usual care group received disease-focused therapies and procedures and were referred by their treating oncologist to supportive care services as needed per standard of care. These services included formal referrals to City of Hope’s clinical palliative care team. The research nurses were Masters prepared with more than 20 years of experience in oncology and extensive palliative care training. They completed the baseline assessments, presented the patient at the IDT meeting and did the didactic teaching but the patient’s oncologists and nurse practitioner continued to provide their care.

Patient-Reported Outcome Measures

The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Lung (FACT-L) tool was used to assess QOL and symptoms. The FACT-L contains 27 items with questions divided into the physical, social/family, emotional, and functional well-being domains. An additional lung cancer subscale (LCS) is included to assess disease-specific symptoms. All items are scored on a 5-point Likert scale (0=not at all; 4=very much). Higher scores indicate better QOL, and the total score ranges from 0 to 140.17 The FACT-L Trial Outcome Index (TOI) score is derived from the physical, functional, and LCS subscales, and focuses more on symptoms and functional well-being. Spiritual well-being was assessed using the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Spirituality subscale (FACIT-Sp-12). This is a 12-item, 5-point Likert scale that assesses sense of meaning, peace, and faith in illness. Total score ranges from 0 to 48, and higher score indicate better spiritual well-being.18 The Distress Thermometer (DT) was used to assess psychological distress. The DT is an efficient, low burden method to evaluate distress, based on a scale of 0 to 10 (0=no distress; 10=extreme distress).19 Patients completed a demographic data tool at baseline.

Heath Care Utilization and End-of-Life Quality Measures

Data on health care utilization and end-of-life measures were extracted through electronic medical chart audits. The time frame for data extraction was from the enrollment date to study completion date. Variables included palliative/supportive care referrals, unscheduled admissions, outpatient unscheduled encounters (by phone or in-person), advance care planning, proxy decision maker preferences, power of attorney status, resuscitation preferences, chemotherapy treatment in the last two weeks of life, and hospice referrals.

Data Collection

Upon enrollment, patients completed baseline questionnaires. Patients enrolled in the Early Stage project completed follow-up questionnaires at 6, 12, 24, 36, and 52 weeks, and patients in the Late Stage project completed follow-up questionnaires up to 24 weeks. Primary outcome analysis, established a priori, was at the 12-week evaluation point. Data were collected during in-person encounters at outpatient clinics or through mailed questionnaires if patients did not have a scheduled clinic encounter. The accepted time frame for data collection was within two weeks before and after the actual follow-up date.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, v. 21 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). All results described herein are based on an intention-to-treat analysis. Patients who completed their baseline measurement were included for analysis. After auditing the data for accuracy, data were matched by ID, and a single imputation method deemed appropriate for the planned analysis was used, with sensitivity analysis, to impute the 3% of the data that were missing. The most appropriate data replacement approach was the Estimation and Maximization (EM) method.

A priori estimates of power for the patient studies (early and late stage) were based on retaining 395 patients in the study at 12 weeks. Power for a moderate effect size range was estimated to be from 0.86 to 1.0, whereas the actual power was 1.0 and 0.92 (QOL and spiritual well-being, respectively), 0.93 (symptoms), and 0.90 (psychological distress).

Selected demographic and chart audit data were compared by group (usual care vs. intervention) and by disease stage (stages I–III vs. IV), using contingency table analysis and the Chi-square statistic. Preliminary analysis revealed that for many outcomes, disease stage groups behaved differently. Therefore each study hypothesis for the four main outcomes was tested using factorial analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) controlling for baseline scores with group and disease stage (Early versus Late Stage) as factors. Multivariate ANCOVA were used in the case of analyzing two or more subscales of a measure, such as QOL subscales in order to account for moderate intercorrelation and control inflation of alpha.

Survival analysis was conducted using the Kaplan-Meier approach by group. We conducted survival estimates for patients with Stage IV disease only. All study patients with Stage IV disease were followed to the close of the study in August 2014 to determine whether they had died. Duration of survival was computed as date of death or close of the study minus date of diagnosis.

Results

Baseline Demographic Characteristics

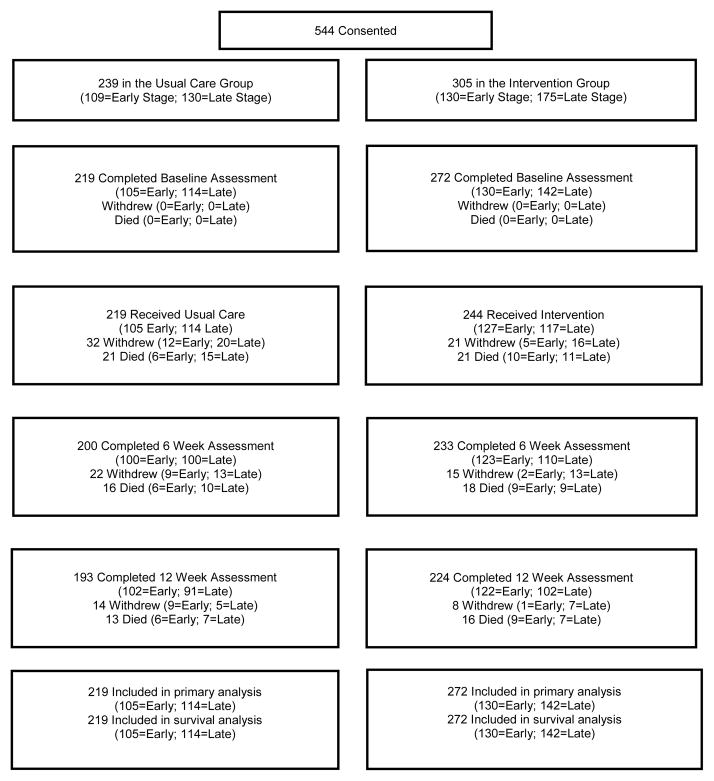

A total of 544 patients were eligible and enrolled in the study between November 2009 and August 2014 (Fig. 1). Of this total, 219 patients in the control group and 272 patients in the intervention group who completed baseline assessments were included in the primary outcome analysis (N=491).

Figure 1.

Patient Enrollment, Treatment, and Data Analysis

Significant between-group differences in baseline demographic characteristics were observed for variables such as age, employment status, and religion (Table 1). This significant difference also was observed for surgical treatment while on study, where patients in the intervention group were more likely to be treated surgically (P=0.002). Within-group and stage differences (Early versus Late Stage) were observed for the following: age, race/ethnicity, living situation, religion, income, and smoking history. Otherwise, no statistically significant differences were observed for the remainder of the demographic and clinical characteristics.

Table 1.

Basic Demographics by Group and Stage Groupings (N=491)

| Standard Care (N=219) | Intervention (N=272) | p-value | Early (N=235) | Late (N=256) | Total (N=491) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |||

| Stage Groupings | |||||||

| Early Stage | 105 (47.9%) | 130 (47.8%) | 1.0 | 235 (47.9%) | |||

| Late Stage | 114 (52.1%) | 142 (52.2%) | 256 (52.1%) | ||||

| Disease Stage | |||||||

| Stage I | 34 (15.5%) | 54 (19.9%) | .29 | 88 (17.9%) | |||

| Stage II | 20 (9.1%) | 29 (10.7%) | 49 (10.0%) | ||||

| Stage III | 51 (23.3%) | 47 (17.3%) | 98 (20.0%) | ||||

| Stage IV | 114 (52.1%) | 142 (52.2%) | 256 (52.1%) | ||||

| Age | |||||||

| <65 | 119 (54.3%) | 109 (40.1%) | .005 | 91 (38.7%) | 137 (53.5%) | 228 (46.4%) | .002 |

| 65–74 | 67 (30.6%) | 100 (36.8%) | 87 (37.0%) | 80 (31.3%) | 167 (34.0%) | ||

| >/= 75 | 33 (15.1%) | 63 (23.2%) | 57 (24.3%) | 39 (15.2%) | 96 (19.6%) | ||

| Gender | |||||||

| Male | 90 (41.1%) | 99 (36.4%) | .30 | 98 (41.7%) | 91 (35.5%) | 189 (38.5%) | .16 |

| Female | 129 (58.9%) | 173 (63.6%) | 137 (58.3%) | 165 (64.5%) | 302 (61.5%) | ||

| Ethnicity | |||||||

| Hispanic/Latino | 15 (6.8%) | 19 (7.0%) | 1.0 | 11 (4.7%) | 23 (9.0%) | 34 (6.9%) | .07 |

| Non Hispanic/Latino | 204 (93.2%) | 253 (93.0%) | 224 (95.3%) | 233 (91.0%) | 457 (93.1%) | ||

| Race | |||||||

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 2 (0.9%) | 0 (0%) | .42 | 1 (0.4%) | 1 (0.4%) | 2 (0.4%) | <.001 |

| Asian | 32 (14.6%) | 32 (11.8%) | 15 (6.4%) | 49 (19.1%) | 64 (13.0%) | ||

| Black or African American | 13 (5.9%) | 14 (5.1%) | 16 (6.8%) | 11 (4.3%) | 27 (5.5%) | ||

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander | 3 (1.4%) | 7 (2.6%) | 2 (0.9%) | 8 (3.1%) | 10 (2.0%) | ||

| White (Includes Latino) | 166 (75.8%) | 217 (79.8%) | 199 (84.7%) | 184 (71.9%) | 383 (78.0%) | ||

| More than one race | 3 (1.4%) | 2 (0.7%) | 2 (0.9%) | 3 (1.2%) | 5 (1.0%) | ||

| Education Completed | |||||||

| Elementary School | 3 (1.4%) | 2 (0.7%) | .71 | 3 (1.3%) | 2 (0.8%) | 5 (1.0%) | .84 |

| Secondary/High School | 78 (35.8%) | 93 (34.2%) | 83 (35.3%) | 88 (34.5%) | 171 (34.9%) | ||

| College | 137 (62.8%) | 177 (65.1%) | 149 (63.4%) | 165 (64.7%) | 314 (64.1%) | ||

| Marital Status | |||||||

| Other (Single, Separated, Widowed, Divorced) | 72 (32.9%) | 101 (37.3%) | .34 | 92 (39.3%) | 81 (31.6%) | 173 (35.3%) | .08 |

| Married/Partnered | 147 (67.1%) | 170 (62.7%) | 142 (60.7%) | 175 (68.4%) | 317 (64.7%) | ||

| Living Situation: Live Alone? | |||||||

| No | 179 (81.7%) | 216 (79.4%) | .56 | 176 (74.9%) | 219 (85.5%) | 395 (80.4%) | .003 |

| Yes | 40 (18.3%) | 56 (20.6%) | 59 (25.1%) | 37 (14.5%) | 96 (19.6%) | ||

| Employment | |||||||

| ≥ 32 hours per week | 46 (21.0%) | 37 (86.4%) | .03 | 44 (18.7%) | 39 (15.2%) | 83 (16.9%) | .33 |

| < 32 hours per week | 173 (79.0%) | 235 (86.4%) | 191 (81.3%) | 217 (84.8%) | 408 (83.1%) | ||

| Religion | |||||||

| Protestant | 90 (41.1%) | 109 (40.1%) | .04 | 95 (40.4%) | 104 (40.6%) | 199 (40.5%) | .001 |

| Catholic | 50 (22.8%) | 76 (27.9%) | 45 (19.1%) | 81 (31.6%) | 126 (25.7%) | ||

| Jewish | 9 (4.1%) | 14 (5.1%) | 13 (5.5%) | 10 (3.9%) | 23 (4.7%) | ||

| Muslim | 1 (0.5%) | 1 (0.4%) | 1 (0.4%) | 1 (0.4%) | 2 (0.4%) | ||

| Buddhist | 7 (3.2%) | 2 (0.7%) | 1 (0.4%) | 8 (3.1%) | 9 (1.8%) | ||

| None | 54 (24.7%) | 47 (17.3%) | 62 (26.4%) | 39 (15.2%) | 101 (20.6%) | ||

| Other | 8 (3.7%) | 23 (8.5%) | 18 (7.7%) | 13 (5.1%) | 31 (6.3%) | ||

| Income | |||||||

| </= $50K | 81 (37.0%) | 93 (34.3%) | .38 | 93 (39.6%) | 81 (31.8%) | 174 (35.5%) | <.001 |

| > $50K | 96 (43.8%) | 135 (49.8%) | 122 (51.9%) | 109 (42.7%) | 231 (47.1%) | ||

| Prefer not to answer | 42 (19.2%) | 43 (15.9%) | 20 (8.5%) | 65 (25.5%) | 85 (17.3%) | ||

| Smoking History | |||||||

| Current Smoker | 14 (6.4%) | 16 (5.9%) | .44 | 18 (7.7%) | 12 (4.7%) | 30 (6.1%) | <.001 |

| Former Smoker | 138 (63.0%) | 186 (68.4%) | 181 (77.0%) | 143 (55.9%) | 324 (66.0%) | ||

| Non-Smoker | 67 (30.6%) | 70 (25.7%) | 36 (15.3%) | 101 (39.5%) | 137 (27.9%) | ||

| Treatments | |||||||

| Chemotherapy | 146 (66.7%) | 199 (73.2%) | .13 | ||||

| Surgery | 36 (16.4%) | 76 (27.9%) | .002 | ||||

QOL and Symptoms at 12 weeks

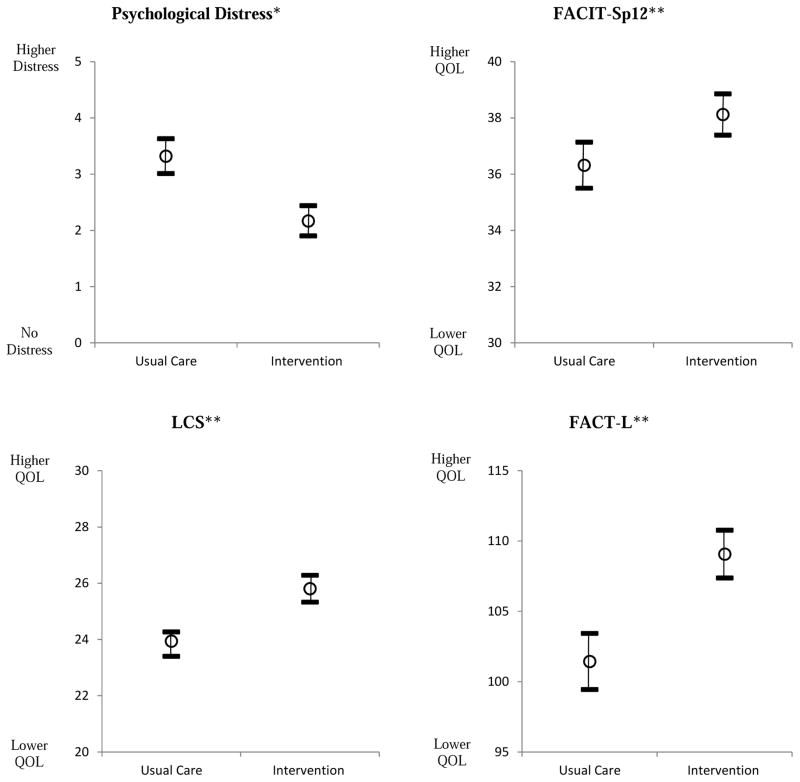

Multivariate analysis of QOL and symptoms revealed that patients in the intervention group had significantly higher scores for the FACT-L, the LCS, and the TOI compared to patients in the usual care group (Fig. 2). A significant interaction between group and stage also was observed for QOL, whereby Early Stage patients in the intervention group had significantly higher scores than those in the usual care group. The two stages were significantly different within each group, with Late Stage patients scoring better under usual care and Early Stage patients scoring better under intervention conditions (Table 2). There were no statistically significant interactions by group for Late Stage patients. For the four QOL subscales, patients in the intervention group had significantly higher scores for the physical, emotional, and functional well-being domains, but this was not observed for the social/family domain.

Figure 2.

Mean Changes in QOL, Symptoms, and Psychological Distress Scores from Baseline to 12 Weeks by Group

*Lower score = less distress

**Higher scores = better QOL

Table 2.

Multivariate Analysis of Main Outcomes at 12 weeks, Controlling for Baseline

| Outcome | Usual Care | Intervention | P Value | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | x̄±SD | x̄a | N | x̄±SD | x̄a | Mainb | Interc | ||

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

| FACT-L (Range = 0–140; higher = better QOL) | Early | 102 | 93.7±20.6 | 97.7 | 129 | 115.4±12.6 | 112.5 | <.001 | <.001 |

| Late | 91 | 105.3±20.1 | 105.2 | 135 | 105.8±18.8 | 105.7 | |||

| Total | 193 | 99.2±21.1 | 101.4 | 264 | 110.5±16.8 | 109.1 | |||

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

| Lung Cancer Subscaled (Range = 0–32; higher = better QOL) | Early | 105 | 22.2±4.8 | 23.1 | 129 | 27.1±3.4 | 26.2 | <.001 | .003 |

| Late | 106 | 24.7±5.1 | 24.8 | 135 | 25.2±4.6 | 25.4 | |||

| Total | 211 | 23.4±5.1 | 23.9 | 264 | 26.2±4.2 | 25.8 | |||

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

| Trial Outcome Index (Range =0–136; higher = better QOL) | Early | 105 | 56.3±13.1 | 58.4 | 129 | 70.0±8.4 | 67.8 | <.001 | <.001 |

| Late | 106 | 63.4±14.0 | 63.5 | 135 | 64.1±12.2 | 64.5 | |||

| Total | 211 | 59.9±14.0 | 60.1 | 264 | 67.0±10.9 | 66.2 | |||

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

| Physical Well Beingd (Range = 0–28; higher = better QOL) | Early | 105 | 19.5±6.2 | 20.2 | 129 | 23.3±3.3 | 22.4 | <.001 | .004 |

| Late | 106 | 21.2±6.2 | 21.4 | 135 | 22.2±4.9 | 22.4 | |||

| Total | 211 | 20.3±6.2 | 20.8 | 264 | 22.8±4.2 | 22.4 | |||

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

| Social/Family Well Beingd (Range = 0–28; higher = better QOL) | Early | 105 | 20.4±6.9 | 21.9 | 129 | 24.5±5.0 | 24.1 | .49 | <.001 |

| Late | 105 | 24.1±4.3 | 23.8 | 135 | 22.7±6.5 | 22.2 | |||

| Total | 211 | 22.3±6.0 | 22.9 | 264 | 23.6±5.8 | 23.1 | |||

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

| Emotional Well Beingd (Range = 0–24; higher = better QOL) | Early | 105 | 16.7±4.8 | 17.2 | 129 | 20.8±3.5 | 20.7 | <.001 | <.001 |

| Late | 106 | 18.5±4.9 | 18.3 | 135 | 19.0±3.9 | 18.9 | |||

| Total | 211 | 17.6±4.9 | 17.7 | 264 | 19.9±3.8 | 19.8 | |||

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

| Functional Well Beingd (Range = 0–28; higher = better QOL) | Early | 105 | 14.6±4.9 | 15.4 | 129 | 19.5±3.5 | 19.1 | <.001 | <.001 |

| Late | 106 | 17.5±5.4 | 17.2 | 135 | 16.6±6.0 | 16.5 | |||

| Total | 211 | 16.1±5.4 | 16.3 | 264 | 18.0±5.1 | 17.8 | |||

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

| FACIT-Sp-12 (Range = 0–48; higher = better spiritual well-being) | Early | 105 | 33.4±9.5 | 35.5 | 129 | 40.3±7.5 | 39.1 | .001 | .001 |

| Late | 106 | 37.3±8.9 | 37.2 | 135 | 37.5±9.7 | 37.1 | |||

| Total | 211 | 35.4±9.3 | 36.3 | 264 | 38.9±8.8 | 38.1 | |||

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

| Meaning (Range = 0–32; higher = better spiritual well-being) | Early | 105 | 24.0±5.9 | 24.8 | 129 | 29.3±3.5 | 28.3 | <.001 | <.001 |

| Late | 106 | 25.5±6.1 | 25.8 | 135 | 25.7±6.3 | 25.9 | |||

| Total | 211 | 24.7±6.0 | 25.3 | 264 | 27.5±5.4 | 25.8 | |||

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

| Psychological Distress (Range = 0–10; higher = more distress) | Early | 102 | 3.5±2.8 | 3.5 | 129 | 1.8±1.9 | 1.7 | <.001 | .001 |

| Late | 91 | 3.0±2.5 | 3.1 | 135 | 2.6±2.4 | 2.7 | |||

| Total | 193 | 3.2±2.7 | 3.3 | 264 | 2.2±2.2 | 2.2 | |||

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

Adjusted means

Main effect of group

Interaction between group and stage

Pillai’s Trace Multivariate p value of < .001 for group and for group by stage interaction

Spiritual Well-Being and Psychological Distress at 12 weeks

A comparison of mean scores for spiritual well-being and psychological distress revealed that patients who received interdisciplinary palliative care had significantly better scores for the FACIT-Sp-12 and DT compared to patients who received usual care (Fig. 1). An interaction between group and stage also was observed, and Early Stage patients who received the intervention had significantly better scores for both measures compared to Early Stage patients who received usual care (Table 2). For spiritual QOL in the usual care condition, Late Stage patients scored significantly better than Early Stage patients. We did not observe a statistically significant difference in between groups for Late Stage patients.

Healthcare Resource Utilization and End-of-Life Care Outcomes

We observed a statistically significant difference in the number of overall referrals (to palliative care, supportive care and other medical services) and unscheduled encounters, with patients in the intervention group having more referrals (61% versus 28%; P<0.001) and unscheduled encounters (32% versus 18.7%; P=0.001) compared to patients in the usual care group (Table 3). The intervention group also had a higher number of referrals to chaplaincy, nutrition, and social work (P<0.001). In addition, there were more pain/palliative care consultations in the intervention group (P=9.048). Patients in the intervention group also had significantly higher numbers of advance care directives (44% versus 9%; P<0.001), more documented proxy decision makers, more documentation of power of attorney, and had more preference for do-not-resuscitate status. There were no statistically significant differences observed between groups for unscheduled admissions, chemotherapy in the last two weeks of life, and hospice referral.

Table 3.

Health Care Utilization Outcomes and Quality Measures for End of Life Care*

| Usual Care | Intervention | Total | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | ||

|

| ||||

| One or More Referrals | 62 (28.3%) | 166 (61.0%) | 228 (46.4%) | <.001 |

| Chaplaincy | 2 (0.9%) | 40 (14.7%) | 42 (8.6%) | <.001 |

| Nutrition | 17 (7.8%) | 60 (22.1%) | 77 (15.7%) | <.001 |

| Pain/Palliative Care | 6 (2.7%) | 18 (6.6%) | 24 (4.9%) | .04 |

| Psychology/Psychiatry | 7 (3.2%) | 12 (4.4%) | 19 (3.9%) | .48 |

| PT/OT | 8 (3.7%) | 6 (2.2%) | 14 (2.9%) | .33 |

| Pulmonary Rehabilitation | 16 (7.3%) | 33 (12.1%) | 49 (10.0%) | .07 |

| Social Work | 28 (12.8%) | 89 (32.7%) | 117 (23.8%) | <.001 |

| Unscheduled Admissions | 17 (7.8%) | 12 (4.4%) | 29 (5.9%) | .11 |

| Unscheduled Encounters | 41 (18.7%) | 87 (32.0%) | 128 (26.1%) | .001 |

| Advance Care Directive | 20 (9.1%) | 120 (44.1%) | 140 (28.5%) | <.001 |

| Proxy Decision Maker | 0 (0.0%) | 42 (15.4%) | 42 (15.4%) | <.001 |

| Power of Attorney | 1 (0.5%) | 118 (43.4%) | 119 (24.2%) | <.001 |

| Do Not Resuscitate | 10 (4.6%) | 47 (17.3%) | 57 (11.6%) | <.001 |

| Chemo in the last 2 weeks (N=45) | 3 (14.3%) | 4 (16.7%) | 7 (15.6%) | 1.00 |

| Hospice Referral | 11 (52.4%) | 11 (45.8%) | 22 (48.9%) | .66 |

|

|

||||

For patients who answered yes only

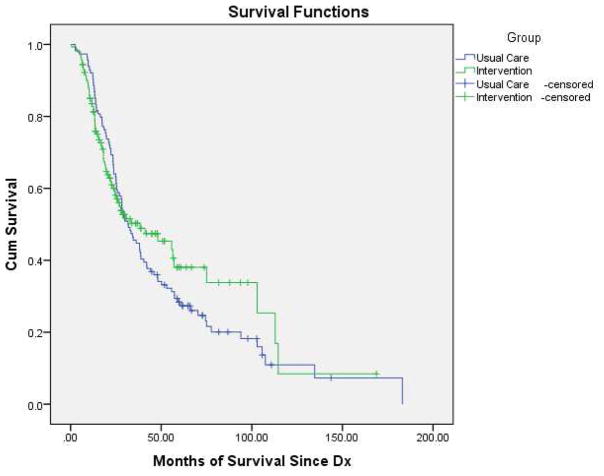

Survival

One hundred sixty-nine patients (77%) in the control group and 217 (80%) patients in the intervention group were alive at the final data collection and censor date (August 25, 2014). Survival analysis for Stage IV patients (date of diagnosis to date of death or study censor date) demonstrated a six-month difference in survival between the two groups (Fig. 2) that did not achieve statistical significance. Median survival was 32.2 months for the control group and 38.3 months for the intervention group (log-rank test, P=0.50) (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier Survival Estimates for Stage IV Patients According to Treatment Group

Discussion

This study demonstrated that a concurrent, interdisciplinary palliative care intervention resulted in statistically significant improvements in QOL, symptoms, and psychological distress in patients with NSCLC. The intervention also had a significant impact on the number of palliative/supportive care referrals and advance care planning.

Although it is widely recommended that palliative care should be delivered concurrently from point of diagnosis to end of life regardless of disease stage, early stage patients are not included in recent published RCTs. To our knowledge, this is one of the first large comparative trials to test concurrent, interdisciplinary palliative care for patients with all stages of disease. The statistically significant effects on primary outcomes observed for patients in the Early Stage project highlights the under-appreciated importance of palliative care for this patient population. This trial adds to the growing evidence that palliative care integrated with disease-focused care benefits patients across all stages of disease but is most effective, as the results indicated, when provided earlier in the course of the disease.

The study also has provided a replicable model for the elements needed in palliative care interventions. These elements should include 1) comprehensive baseline and ongoing QOL assessments, 2) interdisciplinary care coordination, and 3) patient education on QOL issues. The three key components are clearly delineated, and are complementary/synergistic with each other in supporting the patient’s QOL and improving symptoms. The educational component is novel, as we used a tailored approach where the teaching content included those issues endorsed by each specific patient as high priority.

We recognize that most palliative care teams are overwhelmed in meeting the needs of late-stage patients and the study does not suggest that all patients require palliative care consultation. Rather, the study suggests that comprehensive assessment of needs, interdisciplinary care, patient teaching and early referral to palliative care when indicated can benefit patients. The study findings should guide the integration of these palliative care principles into lung cancer care.

Consistent with findings reported by Bakitas9 and Temel,8 this study also observed improvements in QOL, symptoms, and psychological distress with the interdisciplinary palliative care intervention. These findings were demonstrated in the main group effect, with the interaction effect observed significantly for the Early Stage patients only. The improvements seen in QOL and symptoms for this study are clinically meaningful differences. According to Cella and colleagues, a 2–3 point difference in mean scores for the FACT-L and LCS is considered a clinically important change.20 Although Late Stage patients had no significant improvements, scores were overall relatively stable, with small improvements that were not statistically significant. Evidence suggests that it is common to observe gradual, steady increases in symptom intensity with declining functional status and QOL in metastatic disease, a phenomenon known as the “longitudinal terminal QOL decline.”21,22

Healthcare utilization outcomes are becoming increasingly important in palliative care research, and measures such as chemotherapy in the last two weeks of life are standard quality measures for ASCO. Our findings related to resource utilization and quality measures regarding end-of-life care demonstrated improvements in referrals to chaplaincy, nutrition, pain/palliative care, and social work. We did not observe a significant difference in chemotherapy within the last two weeks of life, hospice referrals, and unscheduled admissions. Previous research has shown that the Los Angeles area is a high-cost Medicare region, and that reported aggressiveness in end-of-life care may have been reflected in our findings.23 The observed increases in unscheduled encounters for the intervention group may potentially be a function of more providers being involved in patient care.

There were no differences seen in overall survival by group. Although there was a six- month difference in overall survival between groups, this difference was not statistically significant. The ability to assess the intervention effect on overall survival may have been compromised by the fact that the intervention group was significantly older than the usual care group, and only a relatively small group of patients died while on study.

Several limitations of the study warrant further discussion. First, this study utilized a sequential design, which can potentially result in temporal bias if treatment, practice, or enrollment patterns change over time, therefore creating a source of bias in comparing the two groups. Second, study design did not allow for the identification of specific components of the intervention that resulted in the observed outcomes. This would potentially involve a tremendous amount of resources, a larger sample size, and a study design that includes multiple treatment arms to deconstruct intervention components and treatment effects. Finally, this was a single-site trial, where usual care within our institution may be different than other settings. The investigators are now conducting an National Institutes of Health-National Institute of Nursing Research-funded R01 study testing dissemination of the palliative care intervention for lung cancer patients treated at three Kaiser Permanente hospitals.

In conclusion, this study supports recommendations made by ASCO, the Institute of Medicine and other organizations for quality care through early, concurrent palliative care from point of diagnosis to end of life. Future studies should test palliative care interventions in other cancer diagnoses and other serious illnesses.

Acknowledgments

The research described was supported by grant P01 CA136396 (PI: B. Ferrell) from the National Cancer Institute.

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Cancer Institute or NIH.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ettinger DS. Ten years of progress in non-small cell lung cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2012;10:292–295. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2012.0029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel R, Ma J, Zou Z, et al. Cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64:9–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.21208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Iyer S, Roughley A, Rider A, et al. The symptom burden of non-small cell lung cancer in the USA: a real-world cross-sectional study. Support Care Cancer. 2014;22:181–187. doi: 10.1007/s00520-013-1959-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Poghosyan H, Sheldon LK, Leveille SG, et al. Health-related quality of life after surgical treatment in patients with non-small cell lung cancer: a systematic review. Lung Cancer. 2013;81:11–26. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2013.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koczywas M, Williams AC, Cristea M, et al. Longitudinal changes in function, symptom burden, and quality of life in patients with early-stage lung cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:1788–1797. doi: 10.1245/s10434-012-2741-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Quality Forum. Palliative care and end-of-life care - A consensus report. Washington, DC: NQF; 2012. Available at: http://www.qualityforum.org/Publications/2012/04/Palliative_Care_and_End-of-Life_Care_Consensus_Report.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Consensus Project. Clinical practice guidelines for quality palliative care. Pittsburgh, PA: NCP; 2011. Available from: www.nationalconsensusproject.org. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:733–742. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1000678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bakitas M, Lyons KD, Hegel MT, et al. Effects of a palliative care intervention on clinical outcomes in patients with advanced cancer: the Project ENABLE II randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;302:741–749. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brumley R, Enguidanos S, Jamison P, et al. Increased satisfaction with care and lower costs: results of a randomized trial of in-home palliative care. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:993–1000. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01234.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gade G, Venohr I, Conner D, et al. Impact of an inpatient palliative care team: a randomized control trial. J Palliat Med. 2008;11:180–190. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2007.0055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meyers FJ, Carducci M, Loscalzo MJ, et al. Effects of a problem-solving intervention (COPE) on quality of life for patients with advanced cancer on clinical trials and their caregivers: simultaneous care educational intervention (SCEI): linking palliation and clinical trials. J Palliat Med. 2011;14:465–473. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2010.0416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rabow MW, Dibble SL, Pantilat SZ, et al. The comprehensive care team: a controlled trial of outpatient palliative medicine consultation. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:83–91. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith TJ, Temin S, Alesi ER, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology provisional clinical opinion: the integration of palliative care into standard oncology care. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:880–887. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.5161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Institute of Medicine. Improving palliative care for cancer. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Institute of Medicine. Dying in America: Improving quality and honoring individual preferences near the end of life. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cella DF, Bonomi AE, Lloyd SR, et al. Reliability and validity of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Lung (FACT-L) quality of life instrument. Lung Cancer. 1995;12:199–220. doi: 10.1016/0169-5002(95)00450-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peterman AH, Fitchett G, Brady MJ, et al. Measuring spiritual well-being in people with cancer: the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Spiritual Well-being Scale (FACIT-Sp) Ann Behav Med. 2002;24:49–58. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2401_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Graves KD, Arnold SM, Love CL, et al. Distress screening in a multidisciplinary lung cancer clinic: prevalence and predictors of clinically significant distress. Lung Cancer. 2007;55:215–224. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2006.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cella D, Eton DT, Fairclough DL, et al. What is a clinically meaningful change on the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Lung (FACT-L) questionnaire? Results from Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) Study 5592. J Clin Epidemiol. 2002;55:285–295. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(01)00477-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Diehr P, Lafferty WE, Patrick DL, et al. Quality of life at the end of life. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2007;5:51. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-5-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hwang SS, Chang VT, Fairclough DL, et al. Longitudinal quality of life in advanced cancer patients: pilot study results from a VA medical cancer center. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2003;25:225–235. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(02)00641-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nicholas LH, Langa KM, Iwashyna TJ, et al. Regional variation in the association between advance directives and end-of-life Medicare expenditures. JAMA. 2011;306:1447–1453. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]