Abstract

Background

Heart failure (HF) is a major healthcare burden and there is a growing need to develop strategies to maintain health and sustain quality of life in persons with HF. The purpose of this review is to critically appraise the components of nutrition interventions and to establish an evidence base for future advances in HF nutrition research and practice.

Methods and results

CINAHL, PUBMED, and EMBASE were searched to identify articles published between 2005–2015. A total of 17 randomized controlled trials were included in this review. Results were divided into two categories of nutrition-related interventions: (1) educational and (2) prescriptive Educational interventions improved patient outcomes such as adherence to dietary restriction in urine sodium levels and self-reported diet recall. Educational and prescriptive interventions resulted in decreased readmission rates and patient deterioration. Adherence measurement was subjective in many studies. Evidence showed that a normal sodium diet and 1 liter fluid restriction, along with high diuretic dosing enhanced BNP, aldosterone, TNF-a, and IL-6 markers.

Conclusions

Educational nutrition interventions positively impact patient clinical outcomes. While clinical practice guidelines support a low sodium diet and fluid restriction, research findings have revealed that a low sodium diet may be harmful. Future research should examine the role of macronutrients, food quality and energy balance in HF nutrition.

Keywords: diet, sodium restriction, fluid restriction

Background

Heart failure (HF) is an international public health concern with increasing prevalence and direct health costs. Currently more than 5 million people in the United States and an estimated 23 million people are living with HF worldwide.1 By 2030 an estimated 8 million persons or one out of 33 individuals will have HF in the United States and medical costs are expected to more than double.2 Within the context of rapidly developing healthcare technologies that prolong the lives of persons with HF, there is a growing need to develop strategies to maintain health and sustain quality of life.

There are 6 nutrients that are essential to nutrition: carbohydrates, fats, proteins, water, vitamins, and minerals (including sodium).3–5 Adequate nutrition is particularly important for persons with HF as the risk for developing electrolyte imbalance and vitamin and micronutrient deficiencies increase with the use of diuretics.

Behavior change to modify nutrition is challenging for persons with HF to accomplish as they are frequently managing multiple comorbidities and organ failure.6,7 Adding to the challenges of adherence, there is conflicting evidence to support optimal HF nutrition, particularly sodium and fluid intake.8 A current meta-analysis examined evidence regarding sodium intake and mortality, found low sodium restrictions to increase overall mortality rates in general cardiac disease populations.9 Much of the evidence related to HF nutrition is based on observational studies. The evidence from trials testing nutritional interventions in HF has not been summarized in the literature to date. The purpose of this review is to summarize the current evidence and provide insight for future innovations in HF nutrition research and practice.

Methods

To identify the latest literature, we searched CINAHL, PUBMED and EMBASE for studies published from 2005–July 2015 for studies on nutrition and HF as exemplified by the following PUBMED search strategy: ((“Diet”[Mesh] OR “Nutrition Therapy”[Mesh] OR “Thirst”[Mesh] OR “Sodium Chloride, Dietary”[Mesh] OR “Sodium, Dietary”[Mesh] OR “salt”[Title/Abstract] OR “thirst”[Title/Abstract] OR nutri*[Title/Abstract] OR diet*[Title/Abstract]) AND (“Heart Failure”[Mesh] OR “heart failure”[Title/Abstract] OR “CHF”[Title/Abstract] OR “HF”[Title/Abstract])).

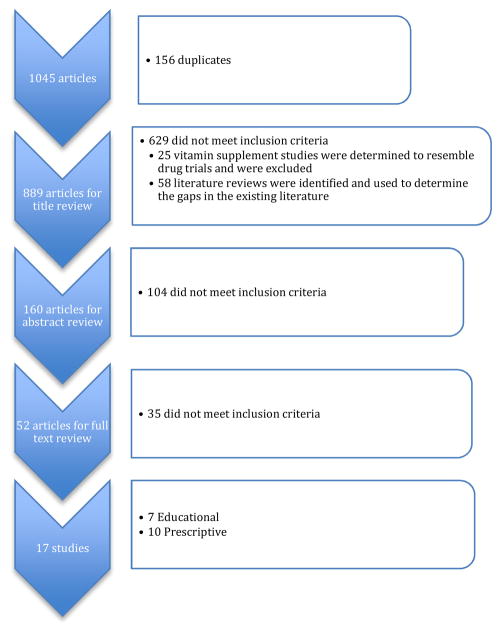

The search returned 1045 studies. In addition to the search terms, studies were included if they were: written in English, human research, nutrition and nutritional supplement (ie protein shakes) interventional studies, adults, left-sided HF. Studies were excluded if they reported on pharmaceutical or vitamin supplement intervention. Several studies mentioned dietary education as part of a self-care intervention, but did not elaborate on what the dietary education provided or did not measure nutrition-related outcomes and were therefore excluded. See figure 1. Titles, abstracts and full text were reviewed by at least two independent reviewers to determine eligibility (DB & JA, 68% agreement and AX &AC, 73% agreement). A third reviewer (MA) reconciled disagreements. After full text review 17 studies met the criteria. After discussing the studies, the reviewers divided the studies into two categories: education-based interventions and prescriptive nutrition interventions. (See Tables 1 & 2) While not mutually exclusive categories, studies that examined knowledge-related factors and that included education in their purpose statement were categorized as educational interventions. We defined prescriptive nutritional interventions, as interventions that required a particular dietary intake, dietary sodium, and/or fluid consumption regimen for participants without an emphasis on education.

Figure 1.

Article Selection

Table 1.

Educational Intervention Studies

| Author Year published Country | Sample, Demographic and HF Characteristics | Design | Measures, Follow-up and Timepoints | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dunbar, S.15 2014 USA | N= 65 Control Group: n= 19 Intervention Group: n= 46 Female: 32.8 % Race distro: African American – 60.7% Caucasian and Other – 39.3% Mean age: 58 years NYHA I: 31.7% NYHA II: 56.7% NYHA III: 11.7% |

RCT (Used 1:2 randomization ratio) Control: Usual Care – 2 brochures Intervention: Usual Care + Intervention 1. Two 45-minute individual education and counseling sessions 2. Nurse-led (using flip charts & script) Content: dietary Na, carbs, fat content charts, common and fast foods, quick nutrition reference guides and suggested snacks, restaurant tips and sample meal plans with recipes |

Measures: Summary of Diabetes Self-Care Activities (SDSCA)* Type of Follow-up: Questionnaires sent via mail. Follow-up with nurse during HF clinic visits. Time points: Baseline, 30 and 90 days Sodium/Fluid Parameters: 2–3g as defined by the HFSA |

1. Increases in SDSCA-General Diet scores for the Intervention group from baseline to 30 days (p=0.05) 2. Decreases in SDSCA-General Diet scores for usual care group from 30 to 90 days (p=0.05) |

| Dunbar, S.16 2013 USA | N= 117 dyads Control: n= 38 dyads Patient Family Education: n= 42 Family Partnership Intervention: n= 37 Female: 37% Race distro: African American – 42% Caucasian – 58% Mean age: 56 years Family/Partner: Spouse: 52.6% Child: 22.4% Other: 25% NYHA II: 72.6% NYHA III: 11.7% |

RCT (3 group) Control: Usual care + informational brochure covering HF self-care Intervention: 1. Patient Family Education (PFE) + 2 hour family partnership training 2. Family Partnership Intervention (FPI)-Two 2-hour sessions of nurse-led training in first 2 months. |

Measures: 3-day food record, 24-hour urine Na Type of Follow-up: Telephone follow-up (PFE) and study newsletter (FPI) Time points: Baseline, 4 months, 8 months Sodium/Fluid Parameters: Urine Na ≤ 2,500 mg/d |

1. Higher adherence to low Na diet (≤2500 mg/d) found in PFE and FPI groups, in comparison to usual care (p=0.016) 2. Lower 24-hour urinary Na in PFE and FPI groups at 4 month follow-up, in comparison to usual care (p=0.018) |

| Welsh, D.17 2013 USA | N= 52 Control group: n= 25 Intervention group: n= 27 Female: 46.2% Race distro: Caucasian – 75% Other – 25% Mean age: Control group: 59 years Intervention group: 53 years NYHA II: 48.1% NYHA III or IV: 51.9% |

RCT (repeated measures) Control: Usual care, no specific diet instructions Intervention: 1. Six weekly education sessions 2. Low Na education materials |

Measures: 3-day food diary, Dietary Sodium Restriction Questionnaire (DSRQ)* Type of Follow-up: Home visit or phone calls over 6-week period Time points: Baseline, 6 weeks, and 6 months Sodium/Fluid Parameters: 2 g as defined by HFSA |

1. Dietary Na intake did not differ between usual care and intervention groups at 6 weeks 2. Lower dietary Na intake in the intervention group at 6 months (p=0.01) 3. Attitudes toward low Na diet improved in the intervention group at 6 weeks (p<0.01) |

| Donner Alves, F.20 2012 Brazil | N= 46 Control group: n= 23 Intervention group: n= 23 Female: 30% Race distro: not specified Mean age: 58 years NYHA class I–III |

RCT Control: Usual care 1. MD and nurse session 2. Nutritionist session Intervention: 1. UC + diet education focused on relationship between HF and diet 2. Low Na (2–3g/day) and cholesterol 3. Macro & micronutrients |

Measures: Nutrition knowledge questionnaire**, 24-hour urine, 24-diet recall Type of Follow-up: HF clinic visits Time points: Baseline, 6 weeks & 6 months Sodium/Fluid Parameters: Na: 2–3g/day as defined by AHA, individualized to disease severity |

1. Reduction in reported Na intake by 24-hour recall in the intervention group (p = 0.017) 2. No significant difference in urinary Na excretion between groups 3. Reduced calorie intake in the intervention group (p = 0.034) |

| Kugler, C.12 2012 Germany | N= 70 Control group: n= 36 Intervention group: n= 34 Female: 15% Race distro: not specified Mean age: 52 years Outpatients with LVADs Mean 44 days post LVAD-implant 55% Heartmate II 45% Heartware |

RCT Control: Standardized usual care for healthy diet, BMI target, regular exercise and reasons to seek psychosocial support Intervention: Dietary Counseling with follow-up every 2 weeks, physical rehab and psychosocial support counseling |

Measures: BMI, exercise tolerance Type of Follow-up: Outpatient visits Time points: Baseline, 6 weeks, 6, 12 and 18 months Sodium/Fluid Parameters: Not defined |

1. Both groups increased exercise tolerance. No significant difference between groups, although trend toward significance in intervention group 2. Nutritional management effects on BMI after 18 months showed significant increase in BMI in control group compared with the Intervention group (P< 0.02) |

| Ferrante, D.14 2010 Argentina | N= 1518 Control group: n= 758 Intervention group: n= 760 Female: 29% Race distro: not specified Mean age: 65 years LVEF ≥ 40: 20.5% LVEF < 40: 79.5% |

RCT Control: Usual care Intervention: 1. Handbook-nutrition, exercise, weight & symptom monitoring 2. Nurse-led telephone call |

Measures: Diet compliance, hospital readmissions, weight control, mortality Type of Follow-up: Individualized, nurse-led telephone follow-up over 16 to 57 months Time points: Participants received calls every 14 days, then frequency can change after 4th phone call; based in individualized needs and severity of case Sodium/Fluid Parameters: Not defined |

1. HF related death and HF hospitalization occurred less in the Intervention group compared to Control (p=0.026) 2. Improved diet compliance in 40% of Intervention group 3. Improved daily weight control in 34.9% of Intervention group 4. Nurse-based telephone intervention was associated with decreased hospitalizations for patients with chronic HF 1 and 3 years after the intervention stopped |

| Arcand, J.L.21 2005 Canada | N= 47 Control group: n= 23 Intervention group: n= 24 Female: 61% Race distro: not specified Mean age: 59 years Mean LVEF: 22.5% |

RCT Control: 1. Prescribed 2g/day Na diet 2. Self-help nutritional literature Intervention: 1. Prescribed 2g/day Na diet 2. Two counseling session with a nutritionist |

Measures: 3 day food record used Type of Follow-up: Sessions with nutritionist Time points: Baseline and 3 months Sodium/Fluid Parameters: Na: 2g/day |

1. Decreased Na intake over 3 months for the intervention group (p<0.05) |

Table 2.

Prescriptive Nutritional Interventions

| Study | Sample, Demographic and HF Characteristics | Design | Measures, Follow-up and Timepoints | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biddle, M.J.34 2015 USA | N= 40 Control group: n= 18 Intervention group: n= 22 Female: 43% Race distro: not specified Mean age: 65 years NYHA II: 70% NYHA III: 30% |

RCT Control: Usual diet Intervention: 11.5-oz can of V8 juice per day + usual diet |

Measures: 24 hour dietary recalls, blood uric acid, CRP, BNP, lycopene Timepoints: Baseline, 1 month |

1. No differences between intervention and control groups in uric acid, BNP, CRP, or Na levels 2. In the intervention group CRP levels decreased among women but not men 3. Plasma lycopene levels increased significantly in intervention group compared to control group (P = 0.02) |

| Colin-Ramirez, E.35 2015 Canada | N= 38 Control group: n= 19 Intervention group: n= 19 Female: 53% Race distro: Caucasian: 95% Other: 5% Mean age: 65.5 years NYHA II: 90% NYHA III: 10% |

RCT Intervention: Group 1: moderate Na (100 mmol or 2300 mg daily) Group 2: low-Na (65 mmol or 1500 mg daily) |

Measures: 3 day food record for previous week; serum labs, plasma BNP Type of Follow up: Research dietitian called monthly Timepoints: Baseline, 3 months, 6 months |

1. Between baseline and 6 months, Na intake did not significantly differ between the two groups 2. Median BNP levels decreased at 6 months for the low Na diet group, but no significant difference in BNP levels between groups |

| Albert, N.29 2013 USA | N= 46 Control group: n= 26 Intervention group: n= 20 Female: 39% Race distro: Caucasian: 50.8% Other: 49.2% Mean age: 63 years NYHA I: 2% NYHA II: 13% NYHA III: 61% NYHA IV: 24% |

RCT Control: Usual Care, often a 2,000-mL/d fluid restriction Intervention: 1,000-mL/d fluid restriction for 60 days after discharge |

Measures: Thirst, Adherence to dietary and fluid restrictions, All-cause mortality, HF hospitalization Type of Follow-up: Reminder phone call and phone interview Time points: 60-day follow-up |

1. Higher self-reported adherence to Na restricted diet reported among Intervention group in comparison to Control (55% vs. 3%) 2. HF emergency room visits were numerically but not significantly higher in the usual care group compared with the 1,000 mL/d group 3. Developed and tested reliability of Fluid Adherence Behaviors Scale (Cronbach’s alpha 0.825–0.85) |

| Badin Aliti, G.13 2013 Brazil | N= 75 Control group: n= 37 Intervention group: n= 38 Female: 31% Race distro: Caucasian: 84% Other: 16% Mean age: 60 years Hospitalized for HF admission NYHA III: 47% NYHA IV: 45% Mean LVEF: 26% |

RCT Control: 1. Standard hospital diet 2. Liberal fluid (at least 2.5L/day) and dietary Na (3–5g/day) Intervention: 1. Fluid restriction (max 800ml/day) 2. Dietary Na restriction (max 800mg/day) |

Measures: Serum labs, Perceived thirst, readmission Type of Follow-up: Nurse-led admission and follow-up exams during hospitalizations Time points: Admission, 3 days into hospital stay and 30-days post discharge |

1. Significantly worse thirst in the Intervention group (p=0.01) at 3-day follow-up 2. Restricting dietary Na leads to activation of the antidiuretic and anti-natriuretic systems 3. No significant difference in readmissions between groups |

| Philipson, H. 182013 Sweden | N= 97 Control group: n= 48 Intervention group: n= 49 Female: 38% Race distro: Unspecified Mean age: 75 years NYHA II: 24% NYHA III: 74% NYHA IV: 0% |

RCT Control: Dietitian or Nurse-led session with brief information to decrease salt and fluid intake Intervention: Individualized dietary support from and RD or RN fluid restriction (max 1500ml/day) and dietary Na restriction (max 5g/day) |

Measures: NYHA class, thirst, weight, 24-hour recall, and HF hospitalization Type of Follow-up: Follow-ups were performed during HF clinic visits and phone calls by RD and RN. Time points: Baseline with follow-up after 4 weeks by the nurse, every 2–3 weeks for 12 weeks by a registered dietician or RN, 12 weeks and follow up in 10–12 months |

1. At the composite endpoint, there were significant improvements in NYHA class, and leg edema the among the intervention group (51% vs., 16%; p<0.001). 2. A significant difference in the numbers of improved patients in the intervention group and deteriorated patients in the in control groups (p<0.001). 3. Interventions designed to individualize salt and fluid restriction were associated with improved NYHA class, weight, lowered diuretic dose QoL, thirst, reduced fluid retention and hospitalizations for patients with chronic HF. |

| Rozentryt, P.10 2010 Poland | N= 29 Control group: n= 6 Intervention group: n= 23 Female: 24% Race distro: not specified Mean age: 51 years NYHA II: 28% NYHA III: 59% NYHA IV: 0.03% |

RCT – double-blind, placebo-controlled Control: 12 kcal per day drink of similar taste and consistency as NutriDrink® + usual diet Intervention: 600 kcal per day as a commercially available formulation NutriDrink® + usual diet |

Measures: Weight, inflammatory markers, lipoproteins Type of Follow up: not specified Timepoints: Baseline, 6 weeks, 18 weeks |

1. Increased edema-free body weight and lean tissue mass after 6 weeks in the intervention group 2. Significant reduction of TNFα, soluble TNF-R1, and TNF-R2 from baseline to 18 weeks 3. Significant increase in serum lipoprotein concentration |

| Philipson, H.26 2010 Sweden | N= 30 Control group: n= 13 Intervention group: n= 17 Female: 27% Race distro: not specified Mean age: 74 years NYHA II: 17% NYHA III: 83% |

RCT Control: general diet info on heart failure Intervention: 1. Na restriction (2–3g/day) and 1.5L/day fluid restriction 2. Individualized dietary recommendations to maintain constant energy level |

Measures: Urine volume & Na level, Thirst, weight, appetite Type of Follow-up: Phone calls with nurse or dietitian every 2–3 weeks Time points: Baseline and 12 weeks |

1. No significant changes in weight, thirst or appetite in Intervention group over 12 weeks 2. Better adherence to fluid restriction in Intervention group 3. Reduced Na excretion in Intervention group (p=0.049) 4. Reduced urine volume and urine Na in Intervention group (p= 0.042 and p=0.039) |

| Parrinello, G.25 2009 Italy | N= 173 Control group: n= 87 Intervention group: n= 86 Female: 39% Race distro: not specified Mean age: 73 years Recent admission for ADHF (class IV) Currently Class II after discharge LVEF < 35% |

RCT Control: 1. Low Na diet (80 mmol-1.8 g/day) 2. 1000 ml fluid restriction, 3. Lasix (125–250 mg BID) Intervention: 1. Moderate Na diet (120 mmol-2.8 g/day) 2. 1000 mg fluid restriction, 3. Lasix (125–250 mg BID) |

Measures: Adherence to fluid and diet, Neurohormonal and cytokines activation, weight, readmissions, mortality Type of Follow-up: Phone call from physician or dietitian Time points: Weekly follow-up for 30-days Then 1x week, 2x month and monthly for 12 months |

1. Neurohormonal (brain natriuretic peptide, aldosterone, plasma rennin activity) and cytokines values (tumor necrosis factor-alpha, interleukin-6) were significantly reduced with a significant increase of the anti-inflammatory cytokine interleukin-10 at 12 months in Intervention group (p≤0.0001) 2. Intervention group showed no significant variation in body weight, whereas the low Na group showed a significant increase (p<0.001) 3. The low-Na diet showed a significant activation of neurohormones and cytokines and worsening of body hydration, whereas moderate Na restriction maintained dry weight and improved outcomes 4. Significant reductions in readmissions (P<0.0001) and mortality (P<0.005) in intervention group |

| Paterna, S.11 2009 Italy | N= 410 8 Groups with 50–52 participants each Female: 63% Race distro: not specified Mean age: 75 years Recent admission for ADHF (class IV) Currently Compensated HF NYHA class II to IV LVEF < 35% |

RCT Randomized 8 groups with all possible combinations of: 1 or 2L fluid restriction 125 or 250 furosemide per day 800 or 120mmol of Na per day |

Measures: Food diaries, lab values, readmissions, mortality Type of Follow-up: Assigned medical visits Time points: 1x week for 1 month, every 2 weeks for next 2 months, every other month thru 6 months |

1. Group A (normal Na diet, fluid intake restriction, and high diuretic dose) showed a significantly lower incidence in readmissions (p <0.001) and a lower rate of mortality than all other groups 2. Food diaries showed good compliance with assigned diets and fluid restriction among all groups 3. Data suggest that the combination of a normal-Na diet with high diuretic doses and fluid intake restriction, leads to reductions in readmissions, neurohormonal activation, and renal dysfunction |

| Paterna, S.24 2008 Italy | N= 232 Group 1= 118 Group 2= 114 Female: 38% Race distro: Not specified Mean age: 73 years NYHA class II–IV, Ejection fraction <35% |

RCT Group 1: 120mmol Na, Oral furosemide (250–500 mg, bid), 1L fluid per day Group 2: 80mmol Na, Oral furosemide (250–500 mg, bid), Fluid intake of 1000 ml per day * Both groups’ diets had same amount of fat, fruit, vegetables, etc. |

Measures: Readmission, serum labs, Mortality Type of Follow-up: Not specified Time points: 1x week for 1 month, every 2 weeks for next 2 months, every other month thru 6 months |

1. Decreased readmissions and deaths in the normal-Na group (P<0.05) 2. Lower BNP values in the normal-Na group compared with the low Na group (P<0.0001) 3. Significant (P<0.0001) increases in aldosterone and PRA in the low-Na group during follow-up while the normal-Na group had a small significant reduction (P=0.039) in aldosterone levels and no significant difference in plasma renin activity 4. Normal-Na diet improves outcomes, but low Na depletion has detrimental renal and neurohormonal effects with worse clinical outcomes in compensated CHF patients |

has established reliability

has established validity

Na - Sodium

NYHA – New York Heart Association Classification System

LVAD – Left Ventricular Assistive Device

LVEF – Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction

CRP – C-reactive protein

BNP – B-type natriuretic peptide

BID – Two Times a Day

HFSA – Heart Failure Society of America

AHA—American Heart Association

RD – Registered Dietician

RN – Registered Nurse

Results

Populations studied

Of the 17 studies included in this review, 7 studies focused on educational interventions to improve nutritional knowledge and compliance with dietary recommendations in HF patients and 10 studies were prescriptive nutritional interventions. (See Tables 1 &2) All of the studies were randomized control trials (RCT). Of the 17 RCTs, 7 were conducted in North America, 7 in Europe and 3 in South America. Sample populations of these studies are reflective of the demographics of the country and only studies from Brazil, Canada, and the United States reported racial diversity. Mean age across studies ranged from 51 years10 to 75 years.11 Overall, women were under represented in the samples ranging from 15%12 to 65%11 with most of the studies including less than 40% women. One trial included decompensated HF patients while the remaining studies included compensated or stable HF patients.13 There was one study including HF patients with Left Ventricular Assist Devices (LVAD); this study was included because there is little data available supporting a difference in dietary restrictions between patients diagnosed with HF with and without an LVAD.12 Sample sizes varied among studies; most studies had 40–100 participants. The largest educational RCT was the DIAL trial with 1518 participants; the largest prescriptive RCT was by Paterna et al with 410 participants.11,14 Two studies addressed power analysis.15,16 Finally, two studies used a family or dyadic approach for the intervention.17,16

Follow up

The duration of the studies and interventional time points varied, ranging from 14 days to 36 months. Most patients were contacted between 4–6 weeks from baseline and were followed up for at least 6 months. Four of the studies provided longer follow up ranging from 8 to 57 months.12,14,16,18 Ferrante et al followed patients for a total of three years after completion of the trial.14

Dietary restrictions to improve nutrition in Heart Failure

There was a common focus on sodium in heart failure nutrition RCTs and practice. Studies included in this review referred to nutrition as “dietary” and “nutrition” teaching as well as “dietary self-care”. These terms were used broadly to cover a very narrow educational focus on teaching a low-sodium diet and food selection. The educational studies provided different parameters to define sodium-restricted or low-sodium diets, most ranging from 2–3g/day. Prescriptive nutritional interventions tested the range of sodium dosing, with sodium restrictions ranging from 0.8g/day to 5 g/day. (See Table 3 & 4)

Table 3.

Educational Strategies

| Strategies | Dunbar 201415 | Dunbar 201316 | Welsh 201317 | Donner Alves 201220 | Kugler 201212 | Ferrante 201014 | Arcand 200521 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nurse/Dietitian led sessions | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Sodium Goal | 2–3g | 2g | 2g | 2–3g | Not stated | Not stated | 2g |

| Study developed materials | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Standardized materials | HFSA | HFSA | HFSA | AHA | ✓ | ||

| Face to Face visits | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Individualized education/planning | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Food diary review with participant | ✓ | ||||||

| Involve family | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Follow-up phone calls | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Published materials/online resources available | ✓ | ✓ |

HFSA – Heart Failure Society of America

AHA—American Heart Association

Table 4.

Sodium and Fluid Restrictions used in Prescriptive Interventions

| Study | High Sodium | Normal/Moderate | Low Sodium | High Fluid | Low Fluid |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biddle 2015 | - | - | - | ||

| Colin-Ramirez 2015 | 2.3g | 1.5 g | |||

| Albert 2013 | 2 L/day | 1 L/day | |||

| Badin Aliti 2013 | 3–5g | 0.8 g | 2.5 L/day | 0.8 L/day | |

| Philipson 2013 | 5g | 1.5 L/day | |||

| Rozentryt 2010 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Philipson 2010 | 2–3 g/day | 1.5 L/day | |||

| Evangelista 2009 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Parrinello 2009 | 2.8 g/day | 1.8 g/day | 1 L/day | ||

| Paterna 2009 | 120 mmol | 800 mmol | 2 L/day | 1 L/day | |

| Paterna 2008 | 120 mmol | 800 mmol |

Beyond sodium, fluid restriction was a key component of prescriptive nutritional studies, but not mentioned in studies describing educational interventions. The widest restriction difference between comparison groups was seen in the study by Badin Aliti et al, with the least restrictive (specified) fluid allowance of 2.5L/day and the most restrictive of 0.8 L/day.13

Quality of food selection and nutrient balance were addressed in few of the intervention studies. Nutritional drinks were examined as simple interventions to improve nutrient balance for persons living with HF.10,19 Also, 3 studies examined caloric/energy balance. Dunbar et al focused on food choices, diet planning and managing the often-conflicting recommendations for diet with multiple co-morbidities, especially diabetes.15 Donner Alves et al and Kugler et al also included instruction on food groups and nutrients.12,20 While many studies used food diaries, most of these studies examined only quantity of sodium, not the source of sodium or change in quality of food choices.

Strategies Utilized to Change Behavior

Seven studies demonstrated that intense HF education improved compliance with dietary restrictions in a HF population. The control group in five studies received written HF education materials that highlighted basic therapeutic life style changes including daily weights and sodium and fluid restrictions.15,12,16,20,21 The intervention groups routinely received the same written materials along with either face-to-face counseling or telephone education sessions. Table 3 describes the general strategies used by educational RCTs. All of the studies used multiple strategies; most common strategies were the use of nurses and dietitians to lead educational sessions, use of study-developed materials, and delivery of individualized, patient-specific sessions. No study provided exemplars of individualized sessions, and therefore it is difficult to understand how this variability may have impacted results.

Educational sessions that were held face to face were common and ranged from 30 minutes to 2 hours. Two studies described the educational focus as a “low-sodium diet” and did not mention providing numeric goal sodium consumption.12,14 The Heart Failure Society of America and American Heart Association have online resources available for patient education that were used in four out of seven studies. Only two studies have published their study protocol or made their study materials publicly available.22,23 The least commonly used strategies were the involvement of family in the designed intervention and the use of food diary review.16

Among prescriptive nutritional interventions, the approach to assist participants to understand how to follow the prescribed sodium/fluid/diet dosing varied. Most used a single handout on how to reduce sodium/fluid consumption, some used standardized diet plans for the participants to follow11,24,25, and 1 study used a face to face session approach acknowledging the importance of social networks and culture on food choices26. Philipson et al explained in the most detail the protocol they used to support participants to maintain the dose required for each study group.26 One study had tighter control over intake because patients were hospitalized.13

Control groups in education interventions and intervention groups in prescriptive nutritional trials (except Philipson et al 2010) used similar methods to give general instructions through the use of general HF education pamphlets. Because improved outcomes were noted in the educational intervention groups, it is possible that prescribed nutrition trials would see different results if more attention was given to support participants to achieve the desired nutritional dosing through the use of additional education strategies.

Adherence measurement could be improved

Urinary sodium has been acknowledged as the gold standard measure of sodium consumption.27 However, despite under-reporting of sodium in food-recall methods documented in previous work, many studies used this method of assessing sodium consumption. Use of a 3-day food diary15,17,21,28, 24-hour diet recall20,19,18 and urine sodium16,20,26 measurement were employed in the trials. Most of the prescriptive studies also collected serum labs and assessed serum sodium.

Alternative approaches to measuring adherence were also utilized in 4 studies. Albert et al developed and assessed reliability of the Fluid Restriction Behaviors Scale, an instrument to measure adherence to fluid restriction (Cronbach’s alpha 0.83–0.85).29 Three studies reported distributing standardized diets as part of the prescriptive regimen.11,24,25 Participants were to prepare the foods as described and reported in a food diary any deviations. Additionally physicians or dietitians called the participants weekly to provide additional assistance with and assessment of adherence.

Adherence was an outcome variable for most educational interventions, but for prescriptive interventions the measure of adherence was used as a process measure to determine if a participant actually followed their prescribed regimen. It was difficult to determine how the data for participants with poor adherence was used. It is unclear if studies used a cutoff threshold level of adherence to include patient data (depending on the study design) or used another approach.

Outcomes of educational and prescriptive nutritional interventions

Educational interventions resulted in significant improvement in urine sodium excretion17,16, self-reported sodium intake17,14,16,20 and daily weight monitoring.12,14 One study reported that participants experienced challenges in obtaining urine sodium which may have limited the ability to detect the effect of the intervention.18

Prescriptive interventions demonstrated improvement in adherence by self report26,29, decreased BNP24,28, aldosterone, TNF-a, and IL-624. Patients reported more difficulty in adhering to lower fluid allotments with as few as 60% reporting adherence to the 1L fluid restriction.29 There was no difference in perceived thirst with moderate fluid restriction26,29, but thirst worsened in a very low sodium and fluid intervention (0.8 g/day and 0.8 L/day).13

Readmissions were decreased by interventions with a normal sodium diet (120mmol)11,24,25 and in an educational intervention delivered via telephone.14 Additionally one study reported a trend toward decreased readmissions29, while a protein shake intervention resulted in no change in readmissions.10 Mortality was also decreased in one educational intervention.14 Low incidence rates may have biased the data in the studies that were shorter in length.

Trials had mixed results regarding changes in weight. Two trials found no difference in change in weight between the intervention and control groups13,26, while intervention group LVAD patients who had dietary counseling along with physical training were able to maintain their BMI, while the control group gained weight.12

Discussion

Defining an appropriate dietary regimen that provides the best overall nutrition for the HF population is still a moving target. Evidence supports reducing sodium to a “normal” level, 2–3g/day. In the context of American sodium consumption, this goal is half of normal sodium consumption.30 In addition, fluid restrictions were rarely included in education interventions, but prescriptive interventions suggest that a 1–1.5 L/day restriction may be beneficial.11,24,25,29 Studies testing prescribed nutrition interventions found low sodium restrictions did not improve clinical outcomes. Our findings show reduced readmissions for normal versus low sodium diets. The utility of a low sodium diet needs to be addressed through further research and by organizations that set HF nutrition guidelines to achieve consensus moving forward.

Heart failure nutrition interventions did not adequately address the composition of overall diet with regard to other nutrient or quality of food choices that may impact outcomes. It is important for studies to report more details about the dietary intake of participants. Adding supplemental nutritional drinks such as V8 or protein shakes to a HF dietary regimen shows initial improvements in some outcomes, but should be further studied particularly with respect to fluid restriction.10,19 Dunbar et al demonstrated the benefit of including additional food quality and nutrient balance education, particularly for co-morbid HF and diabetes.15 Paterna et al demonstrated the benefit of a 120 mmol sodium diet and stated this included a “variety of fruits and vegetables”. It is possible participants in the study benefited from their intake of fruits and vegetables more than adhering to a low sodium diet. Furthermore, understanding the overall nutritional intake for the participants would allow readers to determine if the findings are generalizable to their clinical population. Overall nutritional intake in a normal sodium diet may differ radically between populations by race, ethnicity and geographical location as food choices are heavily influenced by cost, availability and culture.

There were several confounders of outcomes including small sample sizes, multi-dimensional interventions, inconsistent adherence to the intervention, brief follow-up period and low incidence rates. Additionally the samples were homogenous, predominately white and male, making it difficult to generalize the results to many settings.

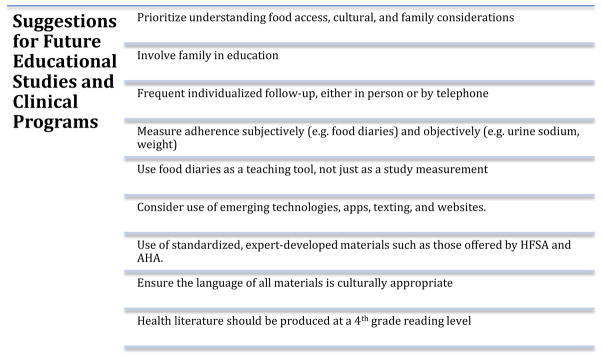

Because of the various strategies employed in each of the educational studies, it is difficult to determine which approaches are most effective. Most interventions involved individualized planning, which is not well explained and may impact overall outcomes. To allow comparisons across nutrition studies, interventions need to be described in more detail through the publication of protocols and making developed educational materials available for use in research as well as to support translation into practice. (See Figure 2)

Figure 2.

Hospital administrators looking for ways to minimize heart failure readmissions through an educational intervention would likely want to know the most cost-effective means to achieve improved outcomes. The long follow-ups in several of the studies bring to question the feasibility and transferability of such interventions to usual practice. Likewise, the cost and resources required to complete interventions are of concern within a currently overburdened health care environment. Nevertheless transitions of care models have proven beneficial and may be able to incorporate many aspects of these interventions.31

Many studies reported improvement in adherence to restriction by participant self report, but divergent findings for urine sodium. Others did not collect an objective measurement to assess adherence. Future research and clinical practice should implement the use of gold standard measurement of sodium restriction adherence, urine sodium. Additional instruments should be developed, such as the Fluid Restriction Behaviors Scale to assess adherence to fluid restriction. Improvement in daily weight monitoring and the use of weight logs may further assist in assessing fluid restriction adherence. Also, family caregivers are heavily involved in the care of persons with HF and often help make decisions on the type of foods to buy and meals to prepare.32 More studies are needed to compare the effect of individual versus group education interventions on nutrition outcomes on an individual and family level

This review has some important limitations. It is possible relevant studies were not included in the review. However, efforts to minimize this were taken by consulting with an experienced health care librarian to finalize search terms. The types of interventions and outcomes measured were heterogeneous, limiting our ability to make comparisons across studies and draw conclusions. In addition, many of the studies included in this review were pilot studies and may not have been adequately powered to see significance in the outcomes of interest. However, the findings of this review agree with many suggestions from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institutes’ Executive Summary for next steps in HF nutrition trials.33 Strengths of this review include the evaluation of RCTs and the evaluation of these studies by a multi-disciplinary team.

Conclusions

Educational nutritional interventions to limit sodium are effective in improving HF patient outcomes, though it is unclear which components of educational programs are most effective. Additional trials are needed to test nutrition education regarding other nutrients, food quality and energy balance. The majority of studies did not randomize an adequate number of women, elderly adults, or underrepresented minorities. Further research will need to include greater diversity in patient populations. Healthcare professionals must take into account cost, availability, and culturally appropriate food when recommending nutrition interventions to their patients with HF. This review supports findings in other cardiac populations that about very low sodium diets (<2g/day) may increase risk of readmission and mortality. Support of programs with ongoing follow-up is needed to improve the nutritional status of HF patients to reduce hospital admissions and to improve quality of life.

HIGHLIGHTS.

Educational nutrition interventions positively impact patient clinical outcomes including self-reported sodium diet adherence, urine sodium and daily weight monitoring.

Normal sodium diets when compared to low sodium resulted in decreased readmissions and mortality

Future research should examine the role of macronutrients, food quality and energy balance in HF nutrition.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge grant support for doctoral student work: Ms. Abshire and Ms. Jiayun Xu and Ms. Jingzhi Xu have been funded by the Interdisciplinary Training in Cardiovascular Health Research, National Institute of Nursing Research (T32 NR012704).

Ms. Jiayun Xu is currently funded through the Interdisciplinary Training in Cancer, Aging and End-of-Life Care, National Institute of Nursing Research, (5 T32 NR013456-03) and was funded by the National Institute of Nursing Research, NIH, (1 F31 NR014750-01) and the American Nurses Foundation. Her prior funding was from the Jonas Nurse Leaders Scholar Program.

Ms. Abshire is additionally funded by National Institute of Nursing Research, NIH, (F31 1 F31 NR015179-01A1, 2015–2017), the Heart Failure Society of America Nurse Research Grant (2014–2016) and the Predoctoral Training in Research Program (NIH 5TL1TR001078-02, 2014–2015)

Footnotes

The authors have no disclosures.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics--2014 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2014;129(3):e28–e292. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000441139.02102.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heidenreich PA, Albert NM, Allen LA, et al. Forecasting the impact of heart failure in the United States: a policy statement from the American Heart Association. Circ Heart Fail. 2013;6(3):606–19. doi: 10.1161/HHF.0b013e318291329a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.FoodPyramid.com. [Accessed September 30, 2015];The 6 Essential Nutrients. 2013 Available at: http://www.foodpyramid.com/6-essential-nutrients/

- 4.Jequier E, Constant F. Water as an essential nutrient: the physiological basis of hydration. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2010;64(2):115–23. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2009.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lichtenstein AH, Russell RM. Essential nutrients: food or supplements? Where should the emphasis be? JAMA. 2005;294(3):351–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.3.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vanstone M, Giacomini M, Smith A, et al. How diet modification challenges are magnified in vulnerable or marginalized people with diabetes and heart disease: A systematic review and qualitative meta-synthesis. Ont Health Technol Assess Ser. 2013;13(14):1–40. Available at: http://www.embase.com/search/results?subaction=viewrecord&from=export&id=L 369965366. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Galani C, Schneider H. Prevention and treatment of obesity with lifestyle interventions: Review and meta-analysis. Int J Public Health. 2007;52(6):348–359. doi: 10.1007/s00038-007-7015-8. Available at: http://www.embase.com/search/results?subaction=viewrecord&from=export&id=L 351166077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McMurray JJV, Adamopoulos S, Anker SD, et al. ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2012: The Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute and Chronic Heart Failure 2012 of the European Society of Cardiology. Developed in collaboration with the Heart. Eur J Heart Fail. 2012;14(8):803–69. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfs105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Graudal N, Jurgens G, Baslund B, Alderman MH. Compared with usual sodium intake, low- and excessive-sodium diets are associated with increased mortality: a meta-analysis. Am J Hypertens. 2014;27(9):1129–37. doi: 10.1093/ajh/hpu028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rozentryt P, von Haehling S, Lainscak M, et al. The effects of a high-caloric protein-rich oral nutritional supplement in patients with chronic heart failure and cachexia on quality of life, body composition, and inflammation markers: a randomized, double-blind pilot study. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2010;1(1):35–42. doi: 10.1007/s13539-010-0008-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Paterna S, Parrinello G, Cannizzaro S, et al. Medium Term Effects of Different Dosage of Diuretic, Sodium, and Fluid Administration on Neurohormonal and Clinical Outcome in Patients With Recently Compensated Heart Failure. Am J Cardiol. 2009;103(1):93–102. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2008.08.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kugler C, Malehsa D, Schrader E, et al. A multi-modal intervention in management of left ventricular assist device outpatients: dietary counselling, controlled exercise and psychosocial support. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2012;42(6):1026–32. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezs206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aliti GB, Rabelo ER, Clausell N, Rohde LE, Biolo A, Beck-da-Silva L. Aggressive fluid and sodium restriction in acute decompensated heart failure: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(12):1058–64. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ferrante D, Varini S, MacChia A, et al. Long-term results after a telephone intervention in chronic heart failure: DIAL (Randomized trial of phone intervention in chronic heart failure) follow-up. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56(5):372–378. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.03.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dunbar SB, Butts B, Reilly CM, et al. A pilot test of an integrated self-care intervention for persons with heart failure and concomitant diabetes. Nurs Outlook. 2014;62(2):97–111. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2013.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dunbar SB, Clark PC, Reilly CM, et al. A trial of family partnership and education interventions in heart failure. J Card Fail. 2013;19(12):829–841. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2013.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Welsh D, Lennie Ta, Marcinek R, et al. Low-sodium diet self-management intervention in heart failure: pilot study results. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2013;12(1):87–95. doi: 10.1177/1474515111435604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Philipson H, Ekman I, Forslund HB, Swedberg K, Schaufelberger M. Salt and fluid restriction is effective in patients with chronic heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2013;15(11):1304–10. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hft097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Biddle JM. Lycopene and its potential nutritional role for patients with heart failure. 2011 Available at: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=rzh&AN=2012154637&site=ehost-live&scope=site.

- 20.Donner Alves F, Correa Souza G, Brunetto S, Schweigert Perry ID, Biolo a. Nutritional orientation, knowledge and quality of diet in heart failure; randomized clinical trial. Nutr Hosp. 2012;27(2):441–448. doi: 10.3305/nh.2012.27.2.5503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arcand JAL, Brazel S, Joliffe C, et al. Education by a dietitian in patients with heart failure results in improved adherence with a sodium-restricted diet: a randomized trial. Am Heart J. 2005;150(4):716. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2005.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Welsh D, Marcinek R, Abshire D, et al. Theory-based low-sodium diet education for heart failure patients. Home Healthc Nurse. 2010;28(7):432–443. doi: 10.1097/NHH.0b013e3181e324e0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grancelli H, Varini S, Ferrante D, et al. Randomized Trial of Telephone Intervention in Chronic Heart Failure (DIAL): study design and preliminary observations. J Card Fail. 2003;9(3):172–9. doi: 10.1054/jcaf.2003.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Paterna S, Gaspare P, Fasullo S, Sarullo FM, Di Pasquale P. Normal-sodium diet compared with low-sodium diet in compensated congestive heart failure: is sodium an old enemy or a new friend? Clin Sci (Lond) 2008;114(3):221–230. doi: 10.1042/CS20070193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Parrinello G, Di Pasquale P, Licata G, et al. Long-term effects of dietary sodium intake on cytokines and neurohormonal activation in patients with recently compensated congestive heart failure. J Card Fail. 2009;15(10):864–873. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2009.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Philipson H, Ekman I, Swedberg K, Schaufelberger M. A pilot study of salt and water restriction in patients with chronic heart failure. Scand Cardiovasc J. 2010;44(4):209–214. doi: 10.3109/14017431003698523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McLean R. Measuring Population Sodium Intake: A Review of Methods. Nutrients. 2014;6(11):4651–4662. doi: 10.3390/nu6114651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Colin-Ramirez E, Mcalister F, Zheng Y, Sharma S, Armstrong P, Ezekowitz J. The SODIUM-HF (Study of Dietary Intervention Under 100 MMOL in Heart Failure) pilot results. Eur Heart J. 2014;35:721–722. Available at: http://www.embase.com/search/results?subaction=viewrecord&from=export&id=L 71649436. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Albert NM, Nutter B, Forney J, et al. A Randomized Controlled Pilot Study of Outcomes of Strict Allowance of Fluid Therapy in Hyponatremic Heart Failure (SALT-HF) J Card Fail. 2013;19(1):1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2012.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bibbins-Domingo K. The institute of medicine report sodium intake in populations: assessment of evidence: summary of primary findings and implications for clinicians. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(1):136–7. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.11818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Albert NM, Barnason S, Deswal A, et al. Transitions of care in heart failure: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circ Heart Fail. 2015;8(2):384–409. doi: 10.1161/HHF.0000000000000006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Buck HG, Harkness K, Wion R, et al. Caregivers’ contributions to heart failure self-care: a systematic review. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2015;14(1):79–89. doi: 10.1177/1474515113518434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.NHLBI WG. [Accessed October 1, 2015];Designing Clinical Studies to Evaluate the Role of Nutrition and Diet in Heart Failure Management. 2013 Available at: http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/research/reports/2013-heart-failure-management.

- 34.Biddle MJ, Lennie TA, Bricker GV, Kopec RE, Schwartz SJ, Moser DK. Lycopene dietary intervention: a pilot study in patients with heart failure. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2015;30(3):205–212. doi: 10.1097/JCN.0000000000000108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Colin-Ramirez E, McAlister FA, Zheng Y, et al. The long-term effects of dietary sodium restriction on clinical outcomes in patients with heart failure. the SODIUM-HF (Study of Dietary Intervention under 100 mmol in Heart Failure): A pilot study. Am Heart J. 2015;169(2):274–281. e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2014.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]