Abstract

We compared T cell recognition of 59 prevalently recognized Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MTB) antigens in individuals latently infected with MTB (LTBI), and uninfected individuals with previous BCG vaccination, from nine locations and populations with different HLA distribution, MTB exposure rates, and standards of TB care. This comparison revealed similar response magnitudes in diverse LTBI and BCG-vaccinated cohorts and significant correlation between responses in LTBIs from the USA and other locations. Many antigens were uniformly recognized, suggesting suitability for inclusion in vaccines targeting diverse populations. Several antigens were similarly immunodominant in LTBI and BCG cohorts, suggesting applicability for vaccines aimed at boosting BCG responses. The panel of MTB antigens will be valuable for characterizing MTB-specific CD4 T cell responses irrespective of ethnicity, infecting MTB strains and BCG vaccination status. Our results illustrate how a comparative analysis can provide insight into the relative immunogenicity of existing and novel vaccine candidates in LTBIs.

Keywords: Tuberculosis, T cell antigen, vaccine, CD4, LTBI, BCG

1. Introduction

The majority of MTB-infected individuals control the pathogen by mounting a successful, long-lived and protective immune response, leading to either resolution or a clinically latent TB infection (LTBI). Approximately 10% of LTBI individuals develop active TB [1, 2]. Established MTB infection provides considerable protection against TB disease from subsequent reinfection, compared with primary infection [3]. This suggests that immune responses introduced by MTB infection provide benefit in those who do not progress to TB disease immediately after they become infected. CD4 T cells secrete IFNγ, which is critical for immune control in MTB infected individuals [4, 5]. Therefore, it is important to identify the antigens that are consistently recognized by T cells in LTBI.

An issue of significant relevance in development of improved TB vaccines is which antigens should be selected. The recent disappointing results of the proof-of-concept trial of MVA85A have added urgency to the debate [6]. At least 13 vaccine candidates against TB are in clinical studies, most of which are aimed at enhancing immunity induced by BCG to prevent disease, but not to achieve sterile eradication or prevention of stable infection [7]. Most subunit vaccine candidates are based on one to four antigens, defined using traditional biochemical methods that are recognized by T cells from patients with LTBI or with cured TB [4, 8]. However, side-by-side comparisons of the frequency (immunodominance) and magnitude (immunogenicity) of immune responses have not been performed.

Significant issues to consider when studying different antigens are the pattern of antigen and epitope recognition in diverse populations associated with different HLA distributions, MTB exposure rates, BCG vaccine strains and circulating MTB strains, variable exposure to environmental mycobacteria, and different standards of clinical care. Therefore, it is important to determine both how frequently and vigorously antigens are recognized overall, and how consistently they are recognized in different locations.

MTB is classified into seven main phylogenetic lineages, which are non-randomly distributed around the world, potentially due to migration with, and adaptation to, different human populations [9, 10]. The main MTB lineage in the Americas and Europe is Lineage 4, whereas, Lineages 1 and 3 are predominant in East Africa and India [10]. However, whether these differences influence the hierarchy of antigen recognition has not been addressed.

T cells recognize peptides bound to MHC molecules. Human (HLA) MHC molecules are extremely polymorphic and thousands of different variants are known [11]. However, at the population level almost 90% of each locus is covered by less than 50 HLA alleles [12] and promiscuous epitopes, recognized by multiple HLA variants, have been shown to represent a large fraction of total responses [13]. Whether promiscuous peptides can be used to monitor responses in multiple ethnicities remains to be experimentally demonstrated.

Another important issue in MTB antigen selection is the relationship between immunogenicity in MTB infection versus BCG vaccination. This is relevant since several TB vaccines currently considered rely on a BCGprime/TB vaccine boost concept [7]. Childhood vaccination with M. bovis BCG mostly protects against disseminated TB in young children. However, in non-endemic countries BCG vaccination is not performed due to the relatively low incidence of disease and variable effectiveness in preventing pulmonary TB in adults [14–16]. After its original development, BCG was distributed to multiple countries worldwide leading to diversification of BCG into distinct sub-strains, which in turn lead to differential ability of BCG strains to induce specific immune responses [17, 18]. However, the results of clinical trials do not provide evidence for a correlation between the vaccine strain used and efficacy in preventing TB [19–21]. Accordingly, side-by-side comparison of the immunogenicity of different MTB antigens following BCG vaccination is also of high interest.

Here we describe reactivity to a set of antigens, previously identified in a non-biased genome-wide study [22], in donor cohorts derived from locations spanning the Americas, Europe, Asia, and Africa. As a result, we have identified a panel of antigens uniformly recognized by LTBIs from different geographical locations. In addition, by comparing the relative ranking in LTBIs and BCG-vaccinated subjects we identified several antigens that might be good targets for boosting BCG responses.

2. Methods

2.1. Study subjects

The different geographical locations, number of donors analyzed and general demographic and clinical characteristics of the populations are shown in Table 2. LTBI for all cohorts except Uganda was confirmed by a positive IGRA (QuantiFERON-TB Gold In-Tube, Cellestis or T-SPOT.TB, Oxford Immunotec). All the Ugandan LTBI subjects had a history of a positive tuberculin skin test (TST). All BCG vaccinated subjects from an area where BCG vaccination is prevalent were assumed to have been vaccinated. The BCG cohort from the USA were recruited based on self-reporting. The MTB-naïve donors did not endorse vaccination with BCG, were all born in countries where BCG vaccination is not used and were IGRA negative. None of the subjects studied had physical exam and/or chest X-ray consistent with active TB, or evidence of HIV or Hepatitis B. Research conducted for this study was performed with approvals from respective Institutional Review boards. All participants, except anonymously recruited blood bank donors in India, provided written informed consent prior to participation in the study. The majority of the LTBI cohort (23 of 25 donors) from USA analyzed here was also utilized in our previous study [22].

Table 2.

Patient cohorts and characteristics

| Location | TB Incidence per 100,000 populationa |

Childhood BCG vaccination |

Cohort | No. individualsb |

Age Median (range) |

Gender M/F (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| USA | 3.3 (3.1–3.7) | No | LTBI BCG MTB naïve |

25 12 30 |

44 (20–65) 32 (20–58) 31 (23–60) |

64/36 58/42 73/27 |

| India | 171 (162–184) | Yes | LTBI BCG |

9 11 |

27 (20–57) N/A |

100/0 N/A |

| Peru | 124 (110–142) | Yes | LTBI | 8 | 36 (20–49) | 75/25 |

| Russia | 89 (82–100) | Yes | LTBI BCG |

9 13 |

41 (24–70) 37 (23–60) |

17/83 39/61 |

| South Africa |

860 (776–980) | Yes | LTBI BCG |

25 23 |

15 (13–18) 16 (12–18) |

36/64 43/57 |

| Central Americac |

see footnoted | Yes | LTBI BCG |

20 23 |

N/A N/A |

N/A N/A |

| Brazil | 46 (41–52) | Yes | LTBI BCG |

14 25 |

32 (18–55) 30 (19–58) |

55/45 31/69 |

| Italy | 5.7 (5.5–6.4) | No | LTBI | 8 | 32 (14–63) | 37/63 |

| Uganda | 166 (149–193) | Yes | LTBI | 10 | N/A | N/A |

| Average (range) | 17 (8–30) | 31 (12–63) | 52/48 | |||

Incidence includes HIV+TB. Ranges in parenthesis represent uncertainty intervals (WHO, March 2015, www.who.int/tb/data)

Indicates the number of different individuals each peptide pool was tested in

Central America includes Jamaica, Haiti, Puerto Rico and Dominican Republic

Jamaica: 6.5 (5.9–7.4), Haiti: 206 (179–231), Puerto Rico: 1.6 (1.4–1.8), Dominican Republic: 60 (54–68)

2.2. Peptides

Sets of 15-mer peptides synthesized by A and A (San Diego) as crude material on a 1 mg scale were combined into pools of up to 20 peptides per antigen (median 18, 3–20 range, Supplementary Table 1). The IEDB submission number for previous described epitopes is 1000505 [22].

2.3. PBMC Isolation

PBMC were obtained by density gradient centrifugation, according to manufacturer’s instructions. Cells were suspended in fetal bovine serum containing 10% dimethyl sulfoxide, and cryo-preserved in liquid nitrogen.

2.4. Ex vivo IFNγ ELISPOT Assay

PBMCs incubated at 2×105 cells/well were stimulated in triplicate with peptide pools (5 µg/ml), PHA (10 µg/ml) or medium containing 0.25% DMSO (percent DMSO in the pools, as a control) in 96-well plates (Immobilion-P; Millipore) coated with 5 µg/ml anti-IFNγ (1-D1K; Mabtech). After 20 h incubation at 37°C, wells were washed with PBS/0.05% Tween 20 and incubated with 2 µg/ml biotinylated anti-IFNγ (7-B6-1; Mabtech) for 2 h. The spots were developed using Vectastain ABC peroxidase (Vector Laboratories) and 3-amino-9-ethylcarbazole (Sigma-Aldrich) and counted by computer-assisted image analysis (KS-ELISPOT reader, Zeiss). Responses were considered positive if the net spot-forming cells (SFC) per 106 were ≥20, the stimulation index ≥2, and p≤0.05 (Student’s t-test, mean of triplicate values of the response against relevant pools vs. the DMSO control). All cohorts, except Brazil and India, were tested at La Jolla Institute for Allergy and Immunology. Samples tested in Brazil and India was tested in a manner analogous to the other cohorts. Samples were excluded if the viability was below 75%, as determined by trypan blue, and reactivity to PHA below 430 SFC/106 cells.

2.5. Factorial peptide pool testing

The number of cells available for each donor from Uganda, Brazil, Italy, and Russia was limiting and did not allow testing of all pools in the same donors. In these cases we tested each pool in the same number of donors but not all in the same individual donor.

3. Results

3.1. Definition of a set of MTB antigens and clinical sites to probe T cell reactivity

To evaluate CD4 T cell reactivity in LTBI donors from different geographical locations, we focused on 59 MTB antigens (Rv number and synonyms in Table 1). In our previous genome-wide study of MTB protein targets for CD4 T cell recognition [22], these antigens accounted for 77% of the total reactivity in LTBIs recruited in San Diego, USA. With the exception of regulatory proteins, these antigens are representative of all protein categories described for the MTB proteome (Table 1), and include those used in the IFNγ release assay (IGRA) test, four currently being evaluated in human vaccines, and 25 previously described. Of interest, around half (28 out of 59) of these antigens were not described as T cell antigens prior to the genome-wide study and are characterized in detail for the first time in the present study.

Table 1.

List of antigens

| Category | Rv no. | Synonym(s)a | Antigen classificationb |

Category | Rv no. | Synonym(s) | Antigen classification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell wall and cell processes |

Rv0287 | EsxG/ TB9.8 |

Prev. known | Inter- mediary metabol- ism and respiration |

Rv0291 | - | Novel |

| Rv0288 | EsxH/ CFP7/ TB10.4 |

Vaccine | Rv0294 | - | Novel | ||

| Rv0289 | - | Novel | Rv2874 | - | Novel | ||

| Rv0290 | - | Novel | Rv2996c | serA/ serA1 |

Novel | ||

| Rv0292 | - | Novel | Rv3025c | nifS/iscS | Novel | ||

| Rv0985c | - | Novel | Lipid metabol- ism |

Rv0129c | 85C/ fbpC/ mpt45 |

Prev. known | |

| Rv0987 | - | Novel | Rv1886c | 85B/ fbpB/ mpt59 |

Vaccine | ||

| Rv1198 | EsxL/ ES6_4/ MTB9.9C |

Prev. known | Rv3804c | 85A/ fbpA/ mpt44 |

Vaccine | ||

| Rv2875 | mpt70/ mpb70 |

Prev. known | PE/PPE | Rv0256c | PPE2 | Prev. known | |

| Rv3019c | EsxR/ ES6_9/ TB10.3 |

Prev. known | Rv0280 | PPE3 | Prev. known | ||

| Rv3020c | EsxS/PE28 | Prev. known | Rv0453 | PPE11 | Prev. known | ||

| Rv3330 | - | Novel | Rv1172c | PE12 | Novel | ||

| Rv3615c | - | Prev. known | Rv1195 | PE13 | Novel | ||

| Rv3874 | EsxB/ CFP10 |

IGRA | Rv1196 | PPE18/ mtb39a |

Vaccine | ||

| Rv3875 | EsxA/ ESAT-6 |

IGRA/Vaccine | Rv1387 | PPE20 | Prev. known | ||

| Rv3876 | - | Novel | Rv1705c | PPE22 | Prev. known | ||

| Conserved hypothe- ticals |

Rv0293c | - | Novel | Rv1788 | PE18 | Novel | |

| Rv0298 | - | Novel | Rv1789 | PPE26 | Prev. known | ||

| Rv0299 | - | Novel | Rv1791 | PE19 | Novel | ||

| Rv0690c | - | Novel | Rv1802 | PPE30 | Prev. known | ||

| Rv1366 | - | Novel | Rv1808 | PPE32 | Prev. known | ||

| Rv2024c | - | Novel | Rv2123 | PPE37 | Prev. known | ||

| Rv2823c | - | Prev. known | Rv2853 | PE_PGRS48 | Novel | ||

| Rv3015c | - | Prev. known | Rv3018c | PPE46 | Prev. known | ||

| Inform- ation pathways |

Rv1317c | - | Novel | Rv3021c | PPE47 | Prev. known | |

| Rv3012c | - | Novel | Rv3022c | PPE48 | Novel | ||

| Rv3024c | - | Novel | Rv3135 | PPE50 | Novel | ||

| Insertion sequences and phages |

Rv1199c | - | Prev. known | Rv3136 | PPE51 | Prev. known | |

| Rv3023c | - | Prev. known | Virulence, detoxi- fication, adaptation |

Rv2031c | hspX | Prev. known | |

| Rv3418c | groES/ cpn10/ mpt57 |

Prev. known |

Synonyms as indicated in TubercuList [50].

Antigen classification denotes antigens previously known as T cell antigens (Prev. known) or novel T cell antigens (Novel) based on previously published work [22], antigens contained in IGRA (Interferon gamma release assay) and antigens currently included in vaccines in clinical trials (Vaccine).

For each antigen, we assessed ex vivo IFNγ ELISPOT T cell reactivity using PBMC samples derived from nine different locations: USA, Central America, Peru, Brazil, South Africa, Uganda, India, Russia and Italy (Table 2), thereby spanning the Americas, Europe, Asia and Africa. We utilized peptide pools containing, for each antigen, all previously described epitopes and, to minimize the impact of different HLA distributions in different ethnicities, additional peptides selected on the basis if predicted promiscuous HLA class II binding capacity (Supplementary Table 1).

Table 2 lists the range of TB incidence in each respective location, ranging from 1.6 per 100,000 population for Puerto Rico to 860 per 100,000 for South Africa. In order to account for existing BCG immunity in the different cohorts, Table 2 lists whether BCG vaccination at birth is routinely administered to the general population [23]. It is generally expected that, with the exception of the USA and Italy, the individuals participating to the study were BCG-vaccinated at birth.

General epidemiological characteristics as well as composition of the various cohorts tested for each site are also detailed in Table 2. The average age for the various cohorts was 31 (ages 12 to 63), and the overall gender ratio was 52% male/48% female. Whenever possible we studied a cohort of LTBI and a control cohort of non-LTBI donors per site. On average each pool was tested in 17 individuals per cohort with a range of 8 to 30. Overall these data demonstrate that the clinical samples investigated span a significant range of location, gender, and age.

3.2. Differential reactivity in the different LTBI cohorts and BCG-vaccinated MTB uninfected cohorts

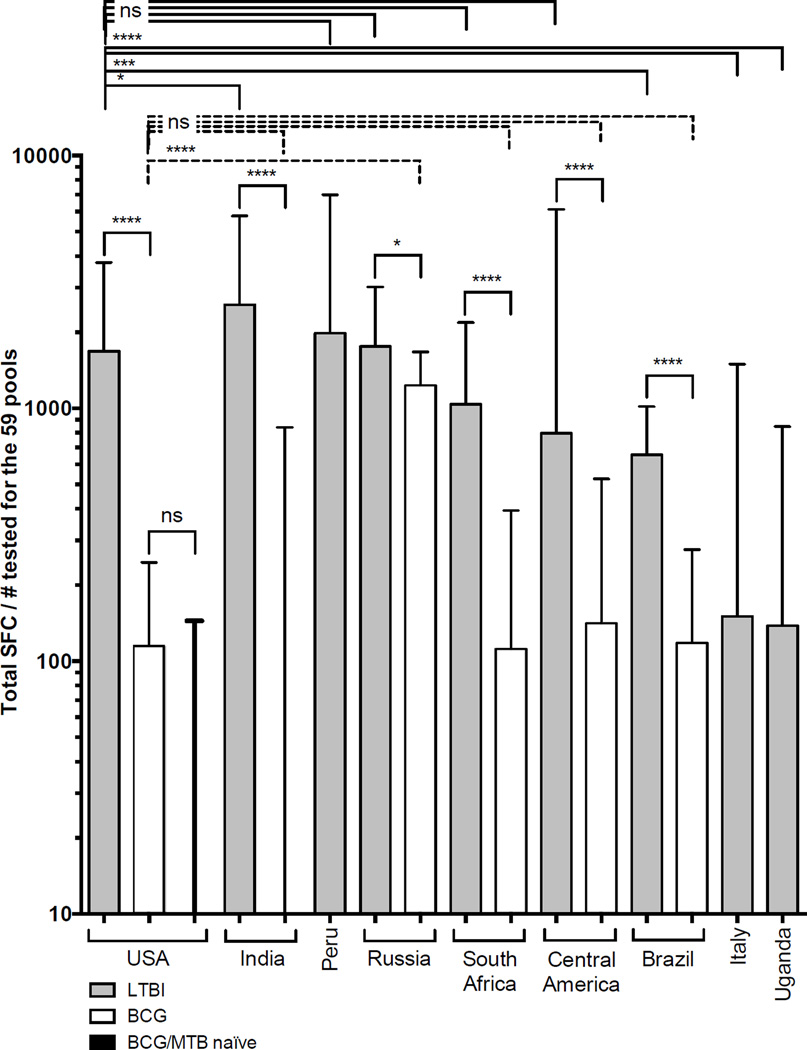

The peptide pools representing each of the 59 antigens (Table 1) were tested for reactivity in the various cohorts (Table 2). Fig. 1 shows the overall reactivity observed expressed as Total SFC/individuals tested. As expected, significantly higher reactivity was noted for LTBIs as compared to BCG.

Figure 1. Reactivity to selected antigens in all tested cohorts.

Reactivity as total SFC/number of tested donors for each individual cohort, LTBI (grey bars), BCG (white bars) and MTB naïve (black bar, third from left). Median ± interquartile range is shown. Two-tailed Mann-Whitney test, ****, p<0.0001, ***, p<0.001, *, p<0.05 and ns, no significant difference. Dashed lines indicate comparison between USA BCG and other BCG cohorts, solid lines indicate comparison between LTBI versus LTBI or LTBI versus BCG.

LTBI donors from the USA had similar overall reactivity to LTBIs from most locations: highest reactivity was seen in Indian LTBIs, and reactivity in American LTBI was not significantly different when compared to donors from Russia, Central America, South Africa or Peru. Strikingly, the Italian, Ugandan and, to a lesser extent, Brazilian LTBI cohorts, had lower reactivity than the other LTBI cohorts. The reasons for these differences are not clear, but might include disparities in circulating MTB strains, local standard of clinical care or cell isolation protocols.

The reactivity in LTBIs was generally significantly higher than the reactivity in BCG-vaccinated donors and MTB naïve controls (non-BCG vaccinated and non-LTBI). The Russian BCG cohort had higher reactivity than any of the other BCG cohorts, which may reflect the common practice of repeated BCG immunizations in Russia and likely in the recruited cohort [23]. With the exception of the Russian BCG cohort, no significant difference was noted when comparing BCG cohorts to each other. Although not significant the Indian BCG cohort had lower reactivity than any of the other cohorts. The reasons for this difference is not clear, but might be due to BCG stain used for vaccination.

3.3. Immunogenicity and immunodominance ranking of the antigen panel

We next analyzed whether hierarchies of immunogenicity and immunodominance would be similar across the different cohorts. For this purpose, we considered both the relative frequency (e.g. immunodominance) and magnitude of responses (e.g. immunogenicity) detected in the cohorts against each antigen. For these analyses, the USA LTBI cohort that was originally used to define the top antigens was compared to each of the LTBI cohorts.

In all cases, this analysis demonstrated a significant correlation between USA and the other LTBI cohorts in terms of immunodominance (Spearman correlation 0.56 (Brazil) to 0.77 (Central America) p<0.0001 in all cases, (Supplementary Figure 1)). Similarly, a significant correlation (Spearman correlation between 0.58–0.85, p<0.0001) was detected in terms of immunogenicity (Supplementary Figure 2). These results demonstrate that despite significant variability in the overall response magnitude, the ranking of the various antigens is similar, suggesting that human immune recognition of the set of antigens is highly consistent in a diverse set of geographical locations.

Next, we calculated the relative immunodominance and immunogenicity ranking of the 59 antigens for each LTBI cohort, respectively, which was averaged to generate overall rankings. These two variables were highly correlated with each other (Spearman correlation r=0.98, p<0.0001, Fig. 2). The antigens that ranked highly for both parameters were from the cell wall and cell processes, as well as PE/PPE protein categories and included both IGRA proteins, previously known and novel T cell antigens (Fig. 2 and Table 3). Interestingly, some of the current vaccine candidates (Rv0288, Rv1196 and Rv3875) were highly ranked while others (Rv1886c and Rv3804c) were not.

Figure 2. Correlation between immunodominance and immunogenicity.

Correlation of average ranking of response frequency (x-axis) versus average ranking of magnitude (y-axis) calculated from all 9 LTBI cohorts. Previously known T cell antigens (grey dots), antigens currently in vaccine trials (blue dots), IGRA antigens (red dots) and novel T cell antigens (black dots). Box indicates top 20 antigens of the 59 selected. Correlation is indicated by Spearman r and associated two-tailed p-value.

Table 3.

Antigens frequently recognized in all LTBI cohorts

| Antigen characteristic |

Rv# | LTBI Average ranking (± SD) |

Diagnostic | Uniform recognition in LTBIa |

Shared dominant with BCGb |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Magnitude | Response frequency |

|||||

| IGRA Vaccine / IGRA |

Rv3874 | 7 (±12) | 5 (±8) | Yes | ||

| Rv3875 | 9 (±7) | 11 (±5) | Yes | Yes | ||

| Prev. known | Rv3136 | 16 (±6) | 13 (±10) | Yes | ||

| Novel | Rv1788 | 15 (±6) | 16(±7) | Yes | Yes | |

| Novel | Rv2853 | 20 (±8) | 13 (±8) | Yes | Yes | |

| Prev. known | Rv0280 | 14 (±6) | 11 (±6) | Yes | Yes | |

| Prev. known | Rv0453 | 11 (±4) | 9 (±6) | Yes | Yes | |

| Prev. known | Rv3018c | 11 (±5) | 9 (±8) | Yes | Yes | |

| Prev. known | Rv3020c | 10 (±8) | 9 (±6) | Yes | Yes | |

| Prev. known | Rv3021c | 13 (±7) | 12 (±10) | Yes | Yes | |

| Vaccine | Rv0288 | 4 (±7) | 7 (±7) | Yes | Yes | |

| Vaccine | Rv1196 | 18 (±7) | 14 (±7) | Yes | Yes | |

| Novel | Rv1195 | 17 (±10) | 14 (±9) | Yes | ||

| Prev. known | Rv0256c | 14 (±11) | 8 (±6) | Yes | ||

| Prev. known | Rv0287 | 13 (±17) | 12 (±12) | Yes | ||

| Prev. known | Rv2123 | 16 (±12) | 10 (±8) | Yes | ||

| Prev. known | Rv3019c | 10 (±15) | 11 (±14) | Yes | ||

| Novel | Rv1791 | 22 (±6) | 17 (±10) | |||

| Prev. known | Rv1387 | 13 (±11) | 9 (±8) | |||

| Prev. known | Rv3615c | 21 (±20) | 19 (±16) | |||

Antigens identified as uniformly recognized in all LTBI cohorts studied (Figure 3A and B).

Antigens identified as shared dominant between LTBI and BCG cohorts (Figure 4A and B).

3.4. Antigen selection based on uniformity of recognition

Uniform recognition in different geographical locations may be an important consideration in the selection of candidate vaccine antigens for worldwide use. Accordingly, the average ranking for each of the antigens was plotted against the associated standard deviation (SD), both in terms of immunogenicity and immunodominance (Fig. 3A and B, Table 3). The average ranking and associated standard deviation for each individual antigen is shown in Supplementary Table 2.

Figure 3. Uniformity of antigen recognition.

Correlation of average ranking of magnitude (A) or response frequency (B) (y-axis) versus standard deviation of ranking (x-axis). Top 20 antigens are above the horizontal dashed line. Uniform recognition SD <10 and heterogeneous recognition SD >10 indicated by vertical dashed line. Previously known T cell antigens (grey dots), antigens currently in vaccine trials (blue dots), IGRA antigens (red dots) and novel T cell antigens (black dots). Correlation is indicated by Spearman r and associated two-tailed p-value, ns, no significant correlation.

Interestingly, the correlation between immunodominance or immunogenicity and the associated SDs was rather poor. This highlights that selection of the most immunogenic antigens will not necessarily ensure uniform geographic and/or ethnic recognition. Nevertheless, the analysis identified 11 (including the IGRA antigen Rv3875) out of the top 20 antigens that ranked high for both immunogenicity and immunodominance, and had also low inter-cohort variation (i.e. were uniformly recognized in the LTBI cohorts; top right quadrant, Fig. 3A and B).

In terms of heterogeneity of responses each antigen were recognized by at least 3 (33%) of the 9 LTBI cohorts tested (Table 4). In fact, 47% were recognized by all of the LTBI cohorts tested and 88% of the antigens were recognized by more than half.

Table 4.

Recognition of antigens in all LTBI cohorts tested

| Rv no. | LTBI cohorts responding (%)a |

Antigen classification |

Rv no. | LTBI cohorts responding (%)a |

Antigen classification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rv0129c | 89% | Prev. known | Rv1802 | 100% | Prev. known |

| Rv0256c | 100% | Prev. known | Rv1808 | 89% | Prev. known |

| Rv0280 | 100% | Prev. known | Rv1886c | 100% | Vaccine |

| Rv0287 | 100% | Prev. known | Rv2024c | 100% | Novel |

| Rv0288 | 100% | Vaccine | Rv2031c | 100% | Prev. known |

| Rv0289 | 56% | Novel | Rv2123 | 100% | Prev. known |

| Rv0290 | 67% | Novel | Rv2823c | 44% | Prev. known |

| Rv0291 | 56% | Novel | Rv2853 | 100% | Novel |

| Rv0292 | 78% | Novel | Rv2874 | 44% | Novel |

| Rv0293c | 33% | Novel | Rv2875 | 100% | Prev. known |

| Rv0294 | 67% | Novel | Rv2996c | 100% | Novel |

| Rv0298 | 44% | Novel | Rv3012c | 78% | Novel |

| Rv0299 | 67% | Novel | Rv3015c | 33% | Prev. known |

| Rv0453 | 100% | Prev. known | Rv3018c | 100% | Prev. known |

| Rv0690c | 78% | Novel | Rv3019c | 100% | Prev. known |

| Rv0985c | 67% | Novel | Rv3020c | 100% | Prev. known |

| Rv0987 | 67% | Novel | Rv3021c | 100% | Prev. known |

| Rv1172c | 89% | Novel | Rv3022c | 78% | Novel |

| Rv1195 | 100% | Novel | Rv3023c | 56% | Prev. known |

| Rv1196 | 100% | Vaccine | Rv3024c | 44% | Novel |

| Rv1198 | 100% | Prev. known | Rv3025c | 67% | Novel |

| Rv1199c | 78% | Prev. known | Rv3135 | 89% | Novel |

| Rv1317c | 100% | Novel | Rv3136 | 100% | Prev. known |

| Rv1366 | 67% | Novel | Rv3330 | 78% | Novel |

| Rv1387 | 100% | Prev. known | Rv3418c | 67% | Prev. known |

| Rv1705c | 78% | Prev. known | Rv3615c | 100% | Prev. known |

| Rv1788 | 100% | Novel | Rv3804c | 67% | Vaccine |

| Rv1789 | 100% | Prev. known | Rv3874 | 100% | IGRA |

| Rv1791 | 89% | Novel | Rv3875 | 100% | IGRA/Vaccine |

| Rv3876 | 44% | Novel |

% of the 9 LTBI cohorts tested that respond to each antigen

3.5. The relative ranking comparing BCG donors to LTBIs

Differential reactivity in LTBIs versus BCG vaccinees is a potentially important factor for vaccine and diagnostics development. Accordingly, immunogenicity and immunodominance of the 59 different MTB antigens in each of the BCG cohort were compared to the corresponding LTBI cohort.

A significant correlation was detected for immunodominance in all cases except for Brazil (Spearman correlations between 0.38–0.60 p<0.01; Supplementary Figure 3). Interestingly, in all cases immunogenicity in the BCG and respective LTBI cohorts was significantly correlated (Spearman correlation between 0.27–0.62, p<0.05; Supplementary Figure 4).

The overall relative immunogenicity and immunodominance rankings in LTBIs and BCG vaccinees were also significantly correlated (p<0.0001; Fig. 4). This analysis identified antigens with diagnostic potential (LTBI-specific) as well as promising antigen targets for boosting of BCG-induced responses (dominant antigens in both BCG and LTBI groups: Fig. 4 and Table 3). Interestingly, only two of the five antigens tested that are currently in vaccine trials were identified as dominant antigens in both BCG and LTBI cohorts.

Figure 4. Shared dominant antigen recognition in BCG versus LTBI.

Correlation of average ranking of response frequency (A) or magnitude (B) in BCG (y-axis) versus average ranking in LTBI (x-axis). Shared dominant antigens (average ranking >20) are indicated by box (small dashes) and LTBI-specific antigens are indicated by dashed box. Previously known T cell antigens (grey dots), antigens currently in vaccine trials (blue dots), IGRA antigens (red dots) and novel T cell antigens (black dots). Correlation is indicated by Spearman r and associated two-tailed p-value.

4. Discussion

We report a side-by-side comparison of responses to dominant antigens previously identified in LTBI donors from the USA [22] and LTBI and BCG cohorts from multiple geographical locations representative of five continents and nine locations. The overall goal of this study was to define the antigens that are consistently recognized by LTBI donors across a wide-breadth of geographic locations, thus demonstrating their general applicability and potential usefulness worldwide. The analysis led to the identification of a set of 11 consistently recognized MTB antigens, which thereby represent potential candidates for vaccine development.

An important caveat to note within the study is that antigens recognized solely in specific populations are overlooked. The rationale for the employed design is based on the idea that epitopes and antigens of greatest interest are those commonly and uniformly recognized by geographically diverse populations. Furthermore, it is important to note the relatively small sample size for each of the sites, especially since the response frequency is less than 50% for most antigens tested.

The study was designed to determine whether the antigens identified in the American cohort were also recognized worldwide in populations that differ in several important aspects. Indeed, the ethnic composition and genetic background of the donor population is diverse between the various sites, and present an important diversity of HLA class II alleles. Further, because of socioeconomic and geographic differences, the clinical presentation, care and treatment of TB disease will vary, leading to potential differences in disease severity and antigen exposure. Finally, differences in circulating MTB strains, and whether childhood BCG vaccination is performed, may also impact antigen recognition [9, 23, 24]. Our results showing remarkably consistent immunodominance and immunogenicity amongst the 9 distinct human populations, suggest that CD4 T cell recognition of MTB antigens is largely independent of the abovementioned covariates. The disparity in correlation seen when comparing immunodominance to immunogenicity highlights the importance of looking at both parameters when evaluating immune responses to a group of antigens. Previous studies, using fewer antigens and whole blood assays, have also seen remarkable similarities in antigen recognition by individuals across diverse sites in Africa [25, 26].

This study included 5 of 11 antigens (Rv0288, Rv1196, Rv1886c, Rv3804c and Rv3875) currently included in TB vaccine candidates [27]. Three of these antigens, Rv0288, Rv1196 and Rv3875, were consistently recognized by persons with LTBI, while BCG-vaccinated cohorts also recognized Rv0288 and Rv1196. As expected, the BCG donors did not recognize Rv3875, since it is localized within the RD1 genomic region that is missing in M. bovis BCG [28]. Interestingly, the closely related Rv1886c and Rv3804c, together with Rv0129c part of the antigen 85 family, were not consistently recognized despite being highly conserved amongst mycobacterial species and present in all BCG strains [29]. Rv3804c is expressed by the MVA85A vaccine candidate, which was developed as a heterologous boost for BCG [30, 31]. The recent landmark MVA85A trial failed to show any additional efficacy against TB disease or MTB infection above that afforded by BCG in infants [6]. A recent phylogenetic study of 12 BCG strains reported an amino acid substitution in Rv1886c in all strains that affects protein structure and/or stability [24]. This protein instability may underlie the differential T cell recognition patterns of Rv1886c, and the largely homologous Rv3804c, between the different settings, since relative contributions of BCG vaccination, exposure to MTB and environmental mycobacteria will differentially influence T cell responses to these antigens.

Our focus on LTBI individuals could also explain the lack of consistent recognition of the antigen 85 family of proteins. It is well known that MTB has adapted to survival in the immune host. Once LTBI has been established, it is thought that the bacteria transform from a replicating metabolically active state to non-replicating persistence with low metabolic activity [32, 33]. This process results in modification of the antigenic repertoire where, for example, expression of Rv0129c, Rv1886c and Rv3804c are down-regulated to very low levels [34–36]. Several human studies have reported differential immune recognition of certain antigens by LTBI individuals as compared to patients with active TB [26, 37–40].

It was recently found that T cell epitopes are hyperconserved, thus suggesting that T cell recognition may be beneficial to MTB and consistency in immune recognition may be undesirable for antigen selection for TB vaccines [41]. Conversely, 90% of individuals with LTBI do not develop TB disease [1, 2] and, importantly, a meta-analysis of risk of progression to active TB suggested that established LTBI provides 79% protection against disease upon re-infection [3]. Both support the idea that the immune response in LTBI, and thus selection of antigens that are immunodominant, is of significant benefit. Under the assumption that consistent T cell recognition of antigens is beneficial for MTB containment by the host, several antigens were identified as promising vaccine candidates. These include previously known T cell antigens (Rv0280, Rv0453, Rv3018c, Rv3020c, Rv3021c, and Rv3136) and the novel T cell antigens, Rv1788 and Rv2853. With the exception of Rv3020c, these antigens are from the large PE/PPE protein category, which are proteins believed to mostly be secreted by MTB and involved in antigenic variation and disease pathogenesis [42]. Rv1196 falls into the same protein category and is included in the M72 vaccine candidate, which has been successfully evaluated in preclinical models [43] and in phase I, I/II, and II trials in high endemic regions with promising results [44–49].

Here we detected high T cell reactivity in the Russian BCG cohort, possibly explained by multiple BCG vaccinations and/or non-tuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) exposure. A genomic comparison of predicted epitopes from MTB and BCG strains identified variations in the number of epitopes present in different BCG strains [24]. Interestingly, BCG Russia had fewer epitopes deleted than other BCG strains, which could also explain the higher and more frequent responses.

Our study underlines the need for an independent genome wide analysis of the antigens recognized following BCG vaccination. The majority (9 of 11) of the antigens consistently recognized in our study were recognized by both LTBIs and BCG donors. Since we studied adolescent and adult populations who received BCG during childhood, and who likely have been exposed to NTM and/or MTB, it is not possible to infer how responses to different antigens are influenced by these different sources of sensitization. T cell responses to dominant antigens primed following BCG vaccination are therefore not yet known, which, along with antigens dominantly recognized in natural MTB infection, is important for the design of BCG prime-boosting vaccines. It is possible that differences in the immune repertoire between pathogenic infection and BCG may be associated with protection and vaccine targeting. However, at this point this is conjectural. An important caveat to note is that BCG, which contains these antigens, is not protective against the main pulmonary from of TB in adults. While the tested antigen targets may indeed be potentially protective, a suitable, yet unknown vaccine formulation remains the limiting factor.

While reactivity of patients from different geographical locations might differ in terms of actual epitopes recognized, the overall reactivity against each pool (protein) was anticipated to reflect the pattern of immunodominance at the antigen level. Due to the limited number of available cells the peptide pools were not deconvoluted to address whether different individual epitopes were recognized amongst the different cohorts.

Taken together, the results presented herein provide insight into the relative immunogenicity in LTBI cohorts of existing and novel vaccine candidates, across a variety of geographical locations with genetically, and environmentally diverse populations. This type of comparative analysis is especially relevant for selection of new TB vaccine candidates and also provides new information relevant to current candidates in ongoing clinical trials.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank K. Roman, M. Alvarez and C. Puernape for technical support in Peru, the IPEC-Fiocruz hospital staff for their help during clinical procedures in Brazil.

Funding:

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [contract HHSN272200900044C to A.S., contract HHSN266200700022C/NO1-AI-70022 to W.H.B, grant R37AI052731 to E.G.K]: the IOC/FIOCRUZ [CNPq research fellowship PQ-2-Brazil to P.R.A.]: the Italian Ministry of Health [Ricerca Corrente to D.G.], the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation [OPP1066265 to T.J.S.], and the HIV Vaccine Trials Network [RAMP scholarship to O.A.P.]. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- MTB

Mycobacterium tuberculosis

- LTBI

Latent tuberculosis infection

- BCG

Bacillus Calmette-Guérin

- TB

tuberculosis

- IGRA

Interferon gamma release assay

- TST

tuberculin skin test

- SFC

spot-forming cells

- NTM

non-tuberculous mycobacteria

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of interest: none

REFERENCES

- 1.Comstock GW. Epidemiology of tuberculosis. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1982;125:8–15. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1982.125.3P2.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaufmann SH. Is the development of a new tuberculosis vaccine possible? Nat Med. 2000;6:955–960. doi: 10.1038/79631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andrews JR, Noubary F, Walensky RP, Cerda R, Losina E, Horsburgh CR. Risk of progression to active tuberculosis following reinfection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2012;54:784–791. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lindestam Arlehamn CS, Lewinsohn D, Sette A, Lewinsohn D. Antigens for CD4 and CD8 T cells in tuberculosis. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in medicine. 2014;4:a018465. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a018465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Winslow GM, Cooper A, Reiley W, Chatterjee M, Woodland DL. Early T-cell responses in tuberculosis immunity. Immunol Rev. 2008;225:284–299. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00693.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tameris MD, Hatherill M, Landry BS, et al. Safety and efficacy of MVA85A, a new tuberculosis vaccine, in infants previously vaccinated with BCG: a randomised, placebo-controlled phase 2b trial. Lancet. 2013;381:1021–1028. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60177-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Karp CL, Wilson CB, Stuart LM. Tuberculosis vaccines: barriers and prospects on the quest for a transformative tool. Immunol Rev. 2015;264:363–381. doi: 10.1111/imr.12270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaufmann SH, Hussey G, Lambert PH. New vaccines for tuberculosis. Lancet. 2010;375:2110–2119. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60393-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coscolla M, Gagneux S. Consequences of genomic diversity in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Semin Immunol. 2014;26:431–444. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2014.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gagneux S, DeRiemer K, Van T, et al. Variable host-pathogen compatibility in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:2869–2873. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511240103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Greenbaum J, Sidney J, Chung J, Brander C, Peters B, Sette A. Functional classification of class II human leukocyte antigen (HLA) molecules reveals seven different supertypes and a surprising degree of repertoire sharing across supertypes. Immunogenetics. 2011;63:325–335. doi: 10.1007/s00251-011-0513-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McKinney DM, Southwood S, Hinz D, et al. A strategy to determine HLA class II restriction broadly covering the DR, DP, and DQ allelic variants most commonly expressed in the general population. Immunogenetics. 2013;65:357–370. doi: 10.1007/s00251-013-0684-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Paul S, Lindestam Arlehamn CS, Scriba TJ, et al. Development and validation of a broad scheme for prediction of HLA class II restricted T cell epitopes. J Immunol Methods. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2015.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Colditz GA, Berkey CS, Mosteller F, et al. The efficacy of bacillus Calmette-Guerin vaccination of newborns and infants in the prevention of tuberculosis: meta-analyses of the published literature. Pediatrics. 1995;96:29–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fine PE. Variation in protection by BCG: implications of and for heterologous immunity. Lancet. 1995;346:1339–1345. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)92348-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Trunz BB, Fine P, Dye C. Effect of BCG vaccination on childhood tuberculous meningitis and miliary tuberculosis worldwide: a meta-analysis and assessment of cost-effectiveness. Lancet. 2006;367:1173–1180. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68507-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Behr MA, Small PM. A historical and molecular phylogeny of BCG strains. Vaccine. 1999;17:915–922. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(98)00277-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ritz N, Hanekom WA, Robins-Browne R, Britton WJ, Curtis N. Influence of BCG vaccine strain on the immune response and protection against tuberculosis. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2008;32:821–841. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2008.00118.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davids V, Hanekom WA, Mansoor N, et al. The effect of bacille Calmette-Guerin vaccine strain and route of administration on induced immune responses in vaccinated infants. J Infect Dis. 2006;193:531–536. doi: 10.1086/499825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gorak-Stolinska P, Weir RE, Floyd S, et al. Immunogenicity of Danish-SSI 1331 BCG vaccine in the UK: comparison with Glaxo-Evans 1077 BCG vaccine. Vaccine. 2006;24:5726–5733. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vijayalakshmi V, Murthy KJ, Kumar S, Kiran AL. Comparison of the immune responses in children vaccinated with three strains of BCG vaccine. Indian pediatrics. 1995;32:979–982. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lindestam Arlehamn CS, Gerasimova A, Mele F, et al. Memory T Cells in Latent Mycobacterium tuberculosis Infection Are Directed against Three Antigenic Islands and Largely Contained in a CXCR3+CCR6+ Th1 Subset. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003130. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zwerling A, Behr MA, Verma A, Brewer TF, Menzies D, Pai M. The BCG World Atlas: a database of global BCG vaccination policies and practices. PLoS Med. 2011;8:e1001012. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Copin R, Coscolla M, Efstathiadis E, Gagneux S, Ernst JD. Impact of in vitro evolution on antigenic diversity of Mycobacterium bovis bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG) Vaccine. 2014;32:5998–6004. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.07.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sutherland JS, Lalor MK, Black GF, et al. Analysis of host responses to Mycobacterium tuberculosis antigens in a multi-site study of subjects with different TB and HIV infection states in sub-Saharan Africa. PLoS One. 2013;8:e74080. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0074080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Black GF, Thiel BA, Ota MO, et al. Immunogenicity of novel DosR regulon-encoded candidate antigens of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in three high-burden populations in Africa. Clinical and vaccine immunology : CVI. 2009;16:1203–1212. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00111-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kaufmann SH. Tuberculosis vaccines: time to think about the next generation. Semin Immunol. 2013;25:172–181. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2013.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harboe M, Oettinger T, Wiker HG, Rosenkrands I, Andersen P. Evidence for occurrence of the ESAT-6 protein in Mycobacterium tuberculosis and virulent Mycobacterium bovis and for its absence in Mycobacterium bovis BCG. Infection and Immunity. 1996;64:16–22. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.1.16-22.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.D'Souza S, Rosseels V, Romano M, et al. Mapping of murine Th1 helper T-Cell epitopes of mycolyl transferases Ag85A, Ag85B, and Ag85C from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infection and Immunity. 2003;71:483–493. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.1.483-493.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McShane H, Pathan AA, Sander CR, et al. Recombinant modified vaccinia virus Ankara expressing antigen 85A boosts BCG-primed and naturally acquired antimycobacterial immunity in humans. Nature medicine. 2004;10:1240–1244. doi: 10.1038/nm1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Scriba TJ, Tameris M, Mansoor N, et al. Dose-finding study of the novel tuberculosis vaccine, MVA85A, in healthy BCG-vaccinated infants. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2011;203:1832–1843. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Andersen P, Doherty TM, Pai M, Weldingh K. The prognosis of latent tuberculosis: can disease be predicted? Trends in Molecular Medicine. 2007;13:175–182. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2007.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barry 3rd CE, Boshoff HI, Dartois V, et al. The spectrum of latent tuberculosis: rethinking the biology and intervention strategies. Nat Rev Micro. 2009;7:845–855. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aagaard C, Hoang T, Dietrich J, et al. A multistage tuberculosis vaccine that confers efficient protection before and after exposure. Nat Med. 2011;17:189–194. doi: 10.1038/nm.2285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Commandeur S, van Meijgaarden KE, Prins C, et al. An unbiased genome-wide Mycobacterium tuberculosis gene expression approach to discover antigens targeted by human T cells expressed during pulmonary infection. J Immunol. 2013;190:1659–1671. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1201593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shi L, North R, Gennaro ML. Effect of growth state on transcription levels of genes encoding major secreted antigens of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in the mouse lung. Infect Immun. 2004;72:2420–2424. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.4.2420-2424.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Demissie A, Leyten EMS, Abebe M, et al. Recognition of Stage-Specific Mycobacterial Antigens Differentiates between Acute and Latent Infections with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2006;13:179–186. doi: 10.1128/CVI.13.2.179-186.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Leyten EMS, Lin MY, Franken KLMC, et al. Human T-cell responses to 25 novel antigens encoded by genes of the dormancy regulon of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Microbes and Infection. 2006;8:2052–2060. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2006.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schuck SD, Mueller H, Kunitz F, et al. Identification of T-Cell Antigens Specific for Latent Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Infection. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e5590. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Goletti D, Butera O, Vanini V, et al. Response to Rv2628 latency antigen associates with cured tuberculosis and remote infection. European Respiratory Journal. 2010;36:135–142. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00140009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Comas I, Chakravartti J, Small PM, et al. Human T cell epitopes of Mycobacterium tuberculosis are evolutionarily hyperconserved. Nat Genet. 2010;42:498–503. doi: 10.1038/ng.590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gey van Pittius N, Sampson S, Lee H, Kim Y, van Helden P, Warren R. Evolution and expansion of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis PE and PPE multigene families and their association with the duplication of the ESAT-6 (esx) gene cluster regions. BMC Evolutionary Biology. 2006;6:95. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-6-95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Reed SG, Coler RN, Dalemans W, et al. Defined tuberculosis vaccine, Mtb72F/AS02A, evidence of protection in cynomolgus monkeys. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:2301–2306. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712077106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Von Eschen K, Morrison R, Braun M, et al. The candidate tuberculosis vaccine Mtb72F/AS02A: Tolerability and immunogenicity in humans. Hum Vaccin. 2009;5:475–482. doi: 10.4161/hv.8570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Spertini F, Audran R, Lurati F, et al. The candidate tuberculosis vaccine Mtb72F/AS02 in PPD positive adults: a randomized controlled phase I/II study. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 2013;93:179–188. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2012.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Montoya J, Solon JA, Cunanan SR, et al. A randomized, controlled dose-finding Phase II study of the M72/AS01 candidate tuberculosis vaccine in healthy PPD-positive adults. Journal of clinical immunology. 2013;33:1360–1375. doi: 10.1007/s10875-013-9949-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Day CL, Tameris M, Mansoor N, et al. Induction and regulation of T-cell immunity by the novel tuberculosis vaccine M72/AS01 in South African adults. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2013;188:492–502. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201208-1385OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Leroux-Roels I, Forgus S, De Boever F, et al. Improved CD4(+) T cell responses to Mycobacterium tuberculosis in PPD-negative adults by M72/AS01 as compared to the M72/AS02 and Mtb72F/AS02 tuberculosis candidate vaccine formulations: a randomized trial. Vaccine. 2013;31:2196–2206. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Idoko OT, Owolabi OA, Owiafe PK, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of the M72/AS01 candidate tuberculosis vaccine when given as a booster to BCG in Gambian infants: an open-label randomized controlled trial. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 2014;94:564–578. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2014.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lew JM, Kapopoulou A, Jones LM, Cole ST. TubercuList - 10 years after. Tuberculosis. 2011;91:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2010.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.