Abstract

As initial steps in a broader effort to develop and test pediatric Pain Behavior and Pain Quality item banks for the Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS®), we employed qualitative interview and item review methods to 1) evaluate the overall conceptual scope and content validity of the PROMIS pain domain framework among children with chronic /recurrent pain conditions, and 2) develop item candidates for further psychometric testing. To elicit the experiential and conceptual scope of pain outcomes across a variety of pediatric recurrent/chronic pain conditions, we conducted semi-structured individual (32) and focus-group interviews (2) with children and adolescents (8–17 years), and parents of children with pain (individual (32) and focus group (2)). Interviews with pain experts (10) explored the operational limits of pain measurement in children. For item bank development, we identified existing items from measures in the literature, grouped them by concept, removed redundancies, and modified remaining items to match PROMIS formatting. New items were written as needed and cognitive debriefing was completed with children and their parents, resulting in 98 Pain Behavior (47 self, 51 proxy), 54 Quality and 4 Intensity items for further testing. Qualitative content analyses suggest that reportable pain outcomes that matter to children with pain are captured within and consistent with the pain domain framework in PROMIS.

Keywords: child, self-report, pain assessment, patient reported outcomes, qualitative, PROMIS

Introduction

As part of its broader initiative to enhance the efficiency, utility and wide applicability of patient self-report measurement in clinical research and practice, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) developed the Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS®) to apply modern measurement theory to the development of a suite of patient reported outcome measures to assess multiple aspects of self-reported health across a range of chronic conditions. The PROMIS cooperative networks of researchers follow rigorous, mixed-method development, testing and validation protocols to create streamlined, reliable and valid tools that assess different components (i.e. physical, mental, social) of adult and child self-reported health, including patient-reported experiences of pain (3, 4, 12).

PROMIS investigators conceptualize and assess the domain of pain in terms of 4 sub-domains: Quality, Intensity, Interference, and Behavior. Pain Quality refers to the specific subjective sensations associated with pain (e.g. temperature, sharpness, pressure) and also to the intensity, frequency and duration of pain. Pain Interference refers to the impact of pain upon daily activities (social, psychological, physical, and recreational activities, and sleep). Pain Behavior refers to behaviors that are observable and communicate to others that an individual is experiencing pain. Pain behaviors can be actions or reactions, verbal or nonverbal, involuntary or deliberate and include displays such as sighing or crying, and pain severity behaviors such as resting, guarding, or asking for help (http://www.nihpromis.org/measures/domainframework2#ph).

Measurement of most domains of health within PROMIS starts with calibrated item banks to derive either brief, static “short form” scales or computer adaptive tests (CATs) to provide a summary score. When there are too few items to comprise an item bank for CAT, PROMIS utilizes item pools, or collections of related, calibrated items, to be administered as short forms or as single item measures. The calibration of items using Item Response Theory (IRT) means very few items are needed to generate precise scores, and these scores-- unlike those developed using classical test theory-- can be directly compared on the same metric even when different items are administered. PROMIS pain measures for adults are now available for each of the 4 pain sub-domains: a Pain-Behavior item bank, a Pain-Interference item bank, Pain-Quality calibrated items (a second version in development), and a calibrated Pain Intensity scale (2, 12, 13).

Development of PROMIS pain measures for children and adolescents is ongoing, with an available, calibrated Pain Interference item bank (15). Apart from PROMIS, validated pediatric pain intensity measures using both numeric and visual response scales are available (9, 19), and the Pediatric Pain Questionnaire (16) assesses pain intensity and location. However, there are no validated self-report pediatric pain quality or behavior measures, and the only existing pain behavior measure for adolescents, the Adolescent Pain Behavior Questionnaire, is designed as a parent proxy measure for parents to report pain behaviors of children ages 11–19 years (8).

In this paper we provide a detailed description of the iterative, qualitative methodology utilized to 1) evaluate the overall conceptual scope and content validity, or ‘fit,’ of the PROMIS pain domain framework among children and adolescents suffering from chronic or recurrent pain conditions, and 2) develop and evaluate item candidates for new PROMIS Pediatric Pain Quality and Pain Behavior item banks, and Pain Intensity items. Valid patient-reported pain outcome measures must consider and incorporate experiences, categories, and language derived from, and meaningful and relevant to pain patients and their families. Thus we qualitatively examined the experiences and perspectives of young pain patients and their families managing a broad range of conditions. Here we describe how these perspectives, along with those of pain researchers, informed a stepwise qualitative process to bring PROMIS from conceptual construct to banks of candidate pediatric pain items ready for calibration testing in a large scale quantitative study.

Methods

Design

In support of our first objective to examine the relevance and meaningfulness of the PROMIS domain framework and pain subdomains for children and adolescents with chronic or recurrent pain, we conducted semi-structured individual and focus group interviews with children and their parents across a range of ages and pain conditions. These interviews focused largely on experiences and episodes of recurrent pain and elicited language, cognitions and other reportable dimensions of their pain. We also interviewed content experts in pediatric pain research and clinical care to explore the scope and limits of pediatric pain constructs and outcomes assessment. For the second objective of developing new item banks for pain behavior and pain quality, we followed the qualitative item review (QIR) process established by PROMIS, which included two rounds of cognitive interviews with children and parents, as well as pain expert input to generate the most comprehensive selection of final items in these subdomains. All procedures and protocols were approved by the hospital’s Institutional Review Board. There is an intentional effort to link pediatric and adult PROMIS item banks across the life course. To the extent the previously established adult pain domain framework and definitions would satisfy the content requirements for the pediatric item banks as based on the content analysis of the interviews, the plan was to adopt them, or adapt them if needed. Our working definition additionally considered the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) taxonomy and definition of pain as “an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage, or described in terms of such damage,” as a widely utilized standard by the pain research community (11).

Pain Experience and Content Expert Interviews (Aim 1)

We conducted focus groups and semi-structured one-on-one, pain-experience-focused interviews with children and with parents to elicit the forms and meanings of children’s pain experiences and episodes. In addition, we conducted 10 semi-structured, telephone interviews with experts in the field of pain study and management to further explore and consider pediatric, pain-related assessment and measures. The expert interviews and focus groups were led by experienced doctoral level scientists in psychology or anthropology.

New Item Development Qualitative Item Review Process (Aim 2)

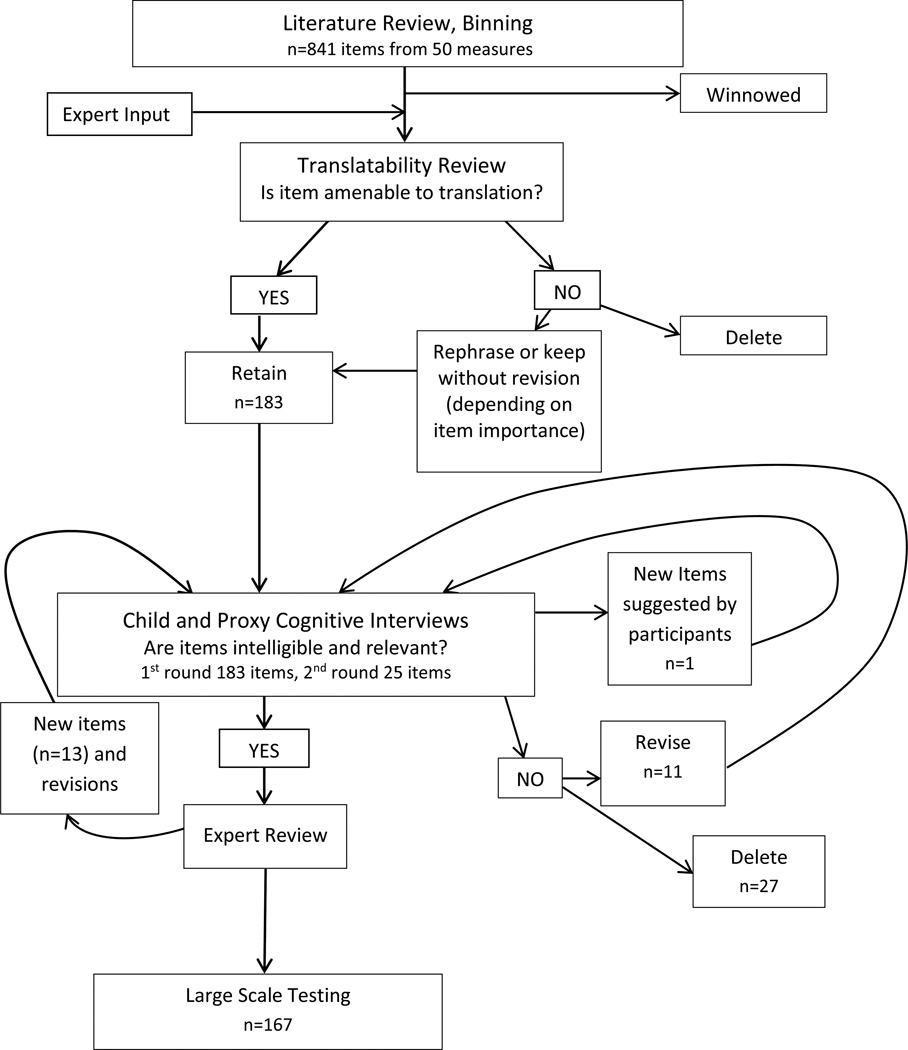

To develop new pediatric item candidates for pain quality, pain behavior (both self and proxy report) item banks, and pain intensity items, we followed the QIR process established by PROMIS and described in detail by DeWalt and colleagues (4). The QIR process consists of 6 steps aimed at identifying, evaluating, and optimizing the form and content of candidate items prior to quantitative evaluation: identification of extant items; item classification and selection (binning and winnowing); item review and revision; individual and focus group input on domain coverage; cognitive interviews on individual items; and final revisions before large-scale field testing (4, 5). Because our QIR procedures so closely parallel those described by DeWalt for the development of adult item candidates, we limit description to processes specific to pediatric (and proxy) pain item development and review (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Steps in Development of Child Pain Quality, Child and Proxy Pain Behavior and Pain Intensity Items

In developing and modifying proxy items, pain quality and pain intensity were conceived as being ideally reported by the person experiencing the sensation subjectively, whereas pain behavior reporting lends itself to both self-report and observation. Proxy pain behavior items were thus developed in conjunction with pediatric pain behavior self-report items whereby items created for self-report were re-written to serve as analogous proxy-report items (7). Proxy report items were also developed for pain intensity items in order to be able to carry out the analysis plan for establishing known groups validity during the subsequent large scale calibration testing.

Interviews for the patient and parent portions of the study were led by 3 female research assistants who all held master’s degrees in a relevant field (social work, psychology, education) and all had previous experience interviewing children with chronic painful conditions. Interviewers received extensive training in cognitive interviewing techniques and in conducting experience-centered qualitative interviews from a doctoral level qualitative research expert. Training included practice sessions in paired or research group contexts, pilot interviews with children in the target age groups, and research team review of transcripts from pilot and early participant interviews. In all, we conducted 7 different interview protocols involving over one hundred interview participants (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Interview Participants and Sample Questions

| Interview | N | Elicitation of Pain Concepts: Sample Interview Questions/Probes |

|---|---|---|

| Semi-structured (Child) | 28 |

|

| Semi-structured (Proxy) | 14 |

|

| Focus groups (Child) | 12 |

|

| Focus groups (Proxy) | 12 |

|

| Pain experts & researchers | 10 |

|

| Eliciting Thinking about PROMIS Candidate Pain Items: Sample Cognitive Probes | ||

| Cognitive (Child) | 15 |

|

| Cognitive (Proxy) |

|

|

Participants

Children and parents of children with a chronic pain condition were recruited from outpatient Rheumatology and Behavioral Medicine and Clinical Psychology (BMCP) clinics at a large Midwestern children’s hospital between February and December 2011. Our intent was to have a sample with diverse pain experiences to assess whether PROMIS items were appropriate measures for use across chronic/recurrent pain conditions, and our final sample included children with sickle cell disease (SCD), juvenile fibromyalgia (JFM), juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA)), headache, and abdominal pain. To participate, children had to be between 8–18 years (inclusive), fluent in English, and diagnosed by a physician with a chronic pain condition. Individuals were ineligible if concurrent medical, psychiatric, or cognitive condition(s) would interfere with their participation.

We identified potential participants through an electronic medical record system. Families were contacted via letter regarding the study, and a research coordinator explained the study and addressed any questions or concerns to those interested in taking part. Interviews were scheduled to take place at a time most convenient for the family, at a location within the hospital. At the time of the interview, the interviewer obtained parental informed consent and children signed an assent document. Parents were asked to complete a socio-demographic form with questions regarding the child’s age, gender, ethnicity, race, chronic health conditions, and grade in school as well as the parent/guardian’s education and relationship to the child. Parent participants were selected based on parents’ interest and willingness to take part, as well as interviewer availability. All (child and parent) participants received a cash incentive in return for their time and effort.

For expert interviews we identified research and clinical experts in pain assessment based on their national reputation for clinical care or research in pediatric pain as a primary focus (as demonstrated by significant publications in the field and/or participation in national pediatric pain networks).

Procedures

Individual interviews

In cases in which both the child and parent were being interviewed, interviews took place simultaneously in different rooms. In cases where the child was the respondent, the parent was asked to leave the room for the duration of the interview. Interviews were conducted in a comfortable, private environment and lasted approximately one hour. Participants were allowed to take a break or end the interview at any time, though no participants ended the interview prematurely. All interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Focus group interviews

We conducted 4 focus groups, 2 each with children and parents, divided on the basis of groupings of child age, 8–12 and 13–18. Interviews took place during the early evening in hospital meeting rooms and lasted about an hour. Participants were provided dinner prior to the interview sessions.

Expert telephone interviews

Research assistants made introductory phone calls to describe the study purpose and protocol and then followed up by email to schedule 30–40 minute, recorded semi-structured interviews conducted by a doctoral level member of the research team and aimed to cover all areas that pain experts would consider as being important in pediatric pain assessment.

Content Elicitation/Key Informant Interviews

Semi-structured, one-on-one interviews explored children’s lived experience of pain roughly along a continuum from the private/unseen to the public/observable with an emphasis on recent and typical pain episodes. We asked children and adolescents to describe: what their pain felt like, its qualities, location, frequency and intensity; the impact or interference of pain on activities, mood, social relationships; the expressions, actions, or behaviors that others could observe that would signal they are in pain; and any other significant aspects or consequences of their pain. All interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed with identifiers removed.

Our qualitative analytic strategy for examining key informant interviews with children, parents and pain experts involved a binning and winnowing process analogous to that used in the development of the item pools. The goal was to identify, categorize and code pain language, expressions and concepts into 4 bins: pain-qualities, -interference, -behaviors, and ‘other’ for reports/quotes that did not fit into these conceptual domains (as defined within the PROMIS domain framework). Though PROMIS Pain Interference items and measures have been created and validated (15), we included reports of pain interference in our coding and analysis as part of the overall conceptual evaluation of the PROMIS pediatric pain outcomes framework. Bins were winnowed by removing duplicate content and by condensing longer excerpts into shorter semantic kernels, conceptually analogous to ‘items.’ We then re-grouped the condensed material by consolidating the excerpts into tables corresponding to each of the PROMIS pain outcome domains (see Supplemental Tables 1 – 6).

Cognitive Interviews as Part of QIR

We conducted child and parent cognitive interviews to ensure that candidate items and response options were written in language that was easily understood by respondents and that the meaning of the items to the respondents reflected domain definitions used in the PROMIS framework. Cognitive interviews served as another opportunity to identify any perceived content gaps. For children, the cognitive interview was preceded by a brief test of reading ability using the Sentence Comprehension and Word Reading subtests of the Wide Range Achievement Test-4 (17).

Interviewers utilized a retrospective debriefing technique in which the respondent first completed a subset of items on paper, after which the interviewer briefly inquired into the respondent’s understanding of the item, decision making processes for choosing among the response choices, and difficulties experienced while answering the questions (4, 18). Cognitive interview questions were modified from procedures described by Irwin (7). The first round of child and adolescent cognitive interviews reviewed a total of 125 items (51 pain behavior, 70 pain quality, 4 pain intensity/global health). Items were divided into five subsets, with 25 to 31 items per set. To minimize participant burden each child reviewed only two subsets (up to 58 items total). Each item was reviewed by at least 6 respondents, including 2 younger children (between 8–12 years of age) and at least 1 child from a non-white racial group. For parents, cognitive interviews were conducted on the proxy report items, with a total of 54 proxy-report pain behavior items and 4 proxy-report pain intensity/global health items. Each item was reviewed by 9 or 10 parents.

After completion of the initial round of interviews, the research team jointly reviewed respondents’ comments for each of the 125 items to identify items needing revision or deletion. We established a procedure whereby if an item received two negative comments such as difficulty with interpretation or lack of applicability to personal experience it would be considered for revision or deletion. A second round of cognitive interviews assessed items newly introduced or modified through the first round or from the expert review of items. In the second round of cognitive interviews, items lacking in consensus or those yet to be reviewed by at least 6 children (due to being newly created or revised) were reviewed. For these interviews, 19 additional children and adolescents were recruited. The same 26 items were reviewed by each respondent.

Results

Across the various interview portions of the study, child respondents were predominantly female (61.3% child, 89.6% parents) and racially diverse (66.2% white, 29.0% African American, 4.8% Other) though largely non-Hispanic (96.8%). Characteristics of study participants completing individual semi-structured interviews are described in Table 2 and of those completing cognitive interviews in Table 3. Characteristics of focus group participants mirrored the gender, racial-ethnic, and diagnostic distributions of participants described in Tables 2 and 3.

Table 2.

Participant Demographics for Pain Experience Elicitation Interviews

| Child/Teen (N=28) | Parent-Proxy (N=14) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | N (%) | Variable | N (%) |

| Gender | -- | Child Gender | -- |

| Male | 10 (36%) | Male | 3 (21%) |

| Female | 18 (64%) | Female | 11 (79%) |

| Diagnosis* | -- | Child’s Diagnosis | -- |

| SCD | 5 (18%) | SCD | 2 (14%) |

| JIA | 11 (39%) | JIA | 5 (36%) |

| JFM | 4 (14%) | JFM | 3 (21%) |

| Misc. | 8 (29%) | Misc. | 4 (29%) |

| Age | -- | Child’s Age | -- |

| 8–12 years | 10 (36%) | 8–12 years | 4 (29%) |

| 13–18 years | 18 (64%) | 13–18 years | 10 (71%) |

| Ethnicity | -- | Child’s Ethnicity | -- |

| Non-Hispanic | 27 (97%) | Non-Hispanic | 14 (100%) |

| Hispanic | 1 (3%) | Hispanic | 0 (0%) |

| Race | -- | Child’s Race | -- |

| White/Caucasian | 19 (68%) | White/Caucasian | 9 (64%) |

| More than one race | 1 (3%) | More than one race | 1 (7%) |

| Black/African American | 8 (29%) | Black/African American | 4 (29%) |

| Highest Grade Completed | -- | Highest Grade Completed (Child) | -- |

| 3rd or lower | 2 (7%) | 3rd or lower | 0 (0%) |

| 4th or 5th | 5 (18%) | 4th or 5th | 3 (21%) |

| 6th–8th | 10 (36%) | 6th–8th | 6 (43%) |

| 9th–11th | 10 (36%) | 9th–11th | 5 (36%) |

| High school degree/GED | 1 (3%) | High school degree/GED | 0 (0%) |

| Parent Ethnicity | -- | ||

| Non-Hispanic | 14 (100%) | ||

| Hispanic | 0 (0%) | ||

| Parent Race | -- | ||

| White/Caucasian | 9 (64%) | ||

| More than one race | 1 (7%) | ||

| Black/African American | 4 (29%) | ||

| Highest Grade Completed (Parent) | -- | ||

| 7th or 8th grade | 1 (7%) | ||

| High school degree/GED | 2 (14%) | ||

| Some college | 5 (36%) | ||

| College degree | 6 (43%) | ||

SCD = Sickle Cell Disease; JIA = Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis; JFM = Juvenile Fibromyalgia; Misc.= migraine (2), back pain (2), postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome with chronic pain (2),chest/gastric pain, complex regional pain syndrome (hand)

Table 3.

Demographics and clinical characteristics of Cognitive Interview participants

| N=15 Round 1 | Approx. % | N=19 Round 2 | Approx. % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 4 | 26.7% | 10 | 52.6% |

| Female | 11 | 73.3% | 9 | 47.4% |

| Age | ||||

| 8–9 years | 2 | 13.3% | 2 | 10.5% |

| 10–12 years | 5 | 33.3% | 8 | 42.1% |

| 13–18 years | 8 | 53.3% | 9 | 47.4% |

| Grade Completed in School | ||||

| 2nd −5th | 5 | 33.3% | 7 | 36.8% |

| 6th-12th | 10 | 66.7% | 12 | 63.2% |

| Reading Score* | N/A | N/A | ||

| 80–100 | 6 | 40.0% | N/A | N/A |

| 100–120 | 4 | 26.7% | N/A | N/A |

| 120 + | 5 | 33.3% | N/A | N/A |

| Mean | 109.53 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Race | ||||

| Caucasian | 10 | 66.7% | 12 | 63.2% |

| African American | 3 | 20.0% | 7 | 36.8% |

| Other-Mixed | 2 | 13.3% | 0 | 0% |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Hispanic | 0 | 0% | 1 | 5.3% |

| Non-Hispanic | 15 | 100% | 18 | 94.7% |

| Diagnosis | ||||

| JIA | 4 | 26.7% | 8 | 42.1% |

| Musculoskeletal pain | 7 | 46.7% | 6 | 31.6% |

| Migraine/Chronic headache | 2 | 13.3% | 0 | 0% |

| Sickle cell disease | 1 | 6.7% | 5 | 26.3% |

| Abdominal pain | 1 | 6.7% | 0 | 0% |

| Guardian Relationship to Child | ||||

| Mother, Stepmother | 12 | 80.0% | 17 | 89.5% |

| Father, Stepfather | 0 | 0% | 1 | 5.3% |

| Grandmother | 0 | 0% | 1 | 5.3% |

| Missing | 3 | 20.0% | 0 | 0% |

| Guardian Education Status | ||||

| Advanced degree | 2 | 13.3% | 3 | 15.8% |

| College | 4 | 26.7% | 7 | 36.8% |

| Some College | 3 | 20.0% | 6 | 31.6% |

| High school degree/GED | 2 | 13.3% | 2 | 10.5% |

| 7th or 8th grade | 1 | 6.7% | 1 | 5.3% |

| Missing | 3 | 20.0% | 0 | 0% |

based on WRAT Reading Composite standard score where 100 represents the mean (SD=10), age-adjusted.

Semi-structured Pain Experience and Concept Elicitation Interviews

We evaluated content validity and the overall conceptual suitability of the PROMIS pain domain framework among child and parent respondents by comparing the experiential, verbal and conceptual content of their accounts of pain episodes with the conceptual content of the PROMIS pain-outcome sub-domains Quality/Intensity, Interference, and Behavior. In a similar fashion, we inspected content of the pain expert interviews to identify the perceived scope of the constructs as well as potential gaps, deficiencies, or promising directions in child pain outcomes assessment. Our qualitative analyses were both confirmatory-- in that we sought to identify language and reports corresponding to a template of PROMIS sub-domains and items—and exploratory, in that we were open and alert to alternative, or emergent wordings or suggestions and for previously unidentified pain outcome themes or dimensions.

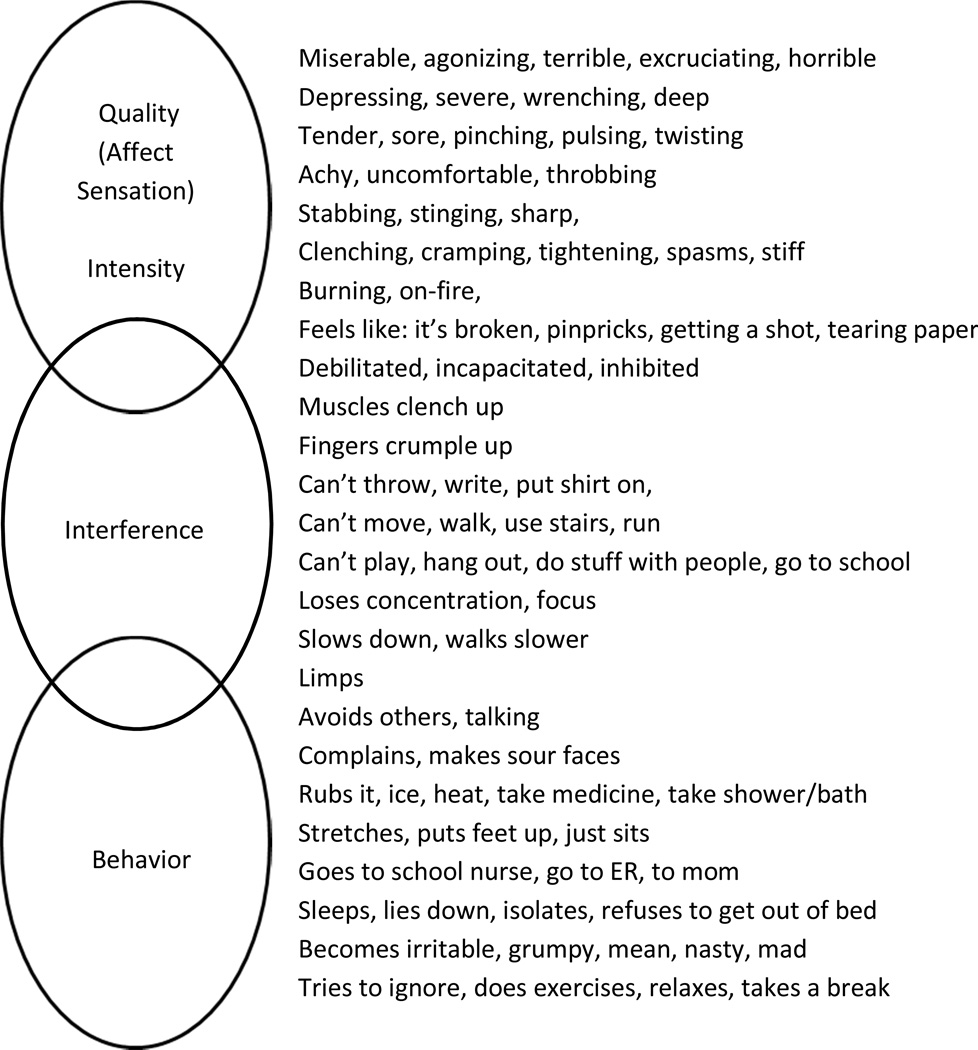

Thus for each of the semi-structured group or individual interview transcripts, we coded and sorted content into 4 bins, 3 corresponding to the aforementioned PROMIS subdomains and 1 additional bin for content that did not conceptually correspond to or fit those domains. Figure 2 presents a parsimonious sampling of pain language used by children and adolescents in the rough form of overlapping Venn ovals clustered by PROMIS pain sub-domain and roughly along a phenomenal continuum from private/subjective to public/observable. Supplemental tables 1 – 6 display an expanded version of these results for child and parent-proxy respondents by domain and across the 3 most frequent diagnostic subgroups (the remaining, miscellaneous pain patients offered no unique, additional terms or expressions) . As the figure and tables show, children and adolescents produced a rich and diverse vocabulary to describe their pain experiences, episodes and impacts; and the vast majority of their pain related utterances fit into one of the three PROMIS pain subdomain bins.

Figure 2.

Examples of Pain Quality, Interference, and Behavior Language Used by Children.

We also found some pain-episode accounts that did not fit the framework. These generally related to depictions of pain coping behaviors and strategies. Examples of coping behaviors include self- distraction (“when I’m doing other stuff, I don’t think about it and I don’t really pay attention and then it don’t really hurt”), exercise activity (“I started exercising, that helped so much”), and environmental accommodations (“I had notes that I was able to get out of class 5 minutes early to make it to next class”). Cognitive and meaning making coping strategies included reappraisals (“put it aside and keep going, save it for another day… and then for the rest of your life”), explanatory or causal models (stress, weather changes, inactivity), and posing existential questions about self, identity, stigma, trust and communication.

Expert Interviews

Analysis of interviews with pain assessment experts also supported the PROMIS domain framework for pain, primarily through informants’ references to or own definitions and measures of pain. All reported familiarity with published measures of pain intensity, impact, and behavior, though we observed considerable variations in preferences and emphases concerning pain assessment in children. Pain intensity measures of diverse kinds (visual analog, numeric 1–10 rating scale, ‘pieces of hurt,’ etc.) were regarded as the most common and widely used. But concerns were raised about: the information lost by using a single number; younger children’s ability to discern 11 levels on a 0–10 scale; and the potentially greater effects of anxiety or other emotional/situational factors in pain intensity reports of children compared to adults. Some preferred to elicit metaphors from children, and others de-emphasized intensity altogether, favoring interference or impact measures including daily diary measures. For assessing the impact of pain on children, informants emphasized the functional dimensions of sleep, concentration, peer relations, mood, and appetite, but they also mentioned the importance of activity avoidance as well as withholding disclosures (e.g., minimizing pain in order to appear more like their peers). Informants’ use of measurement tools for pain behavior was less common likely due to the paucity of such measures, but several emphasized their importance because children’s limited cognitive and verbal abilities may require additional assessment of more readily observable behavioral expressions of pain, particularly in the younger age ranges. Other aspects of pain assessment mentioned focused primarily on coping, self-efficacy, and use of self-management techniques.

Cognitive Interviews

As a group, the 15 children and adolescents who participated in the first round of cognitive interviews had a mean WRAT-4 Reading Composite score of 109.5, which is slightly higher than age adjusted population norms (mean=100; SD=10) and probably characteristic of the middle class, relatively well-educated population that presents to the hospital’s pain clinics.

Participants at all ages grasped that the recall period referred to the past week, but we found the need to reiterate the 7 day time frame for some younger children. Modification or removal of items resulting from the cognitive interviews occurred for reasons of poor understanding, irrelevance, or inappropriateness (see Table 4). We removed 8 pain-quality items of as a result of respondents’ not understanding their meaning (e.g., “thrashed,” “oppressive,” “gnawing”) or not understanding how the item was related to pain (e.g. “vicious”). Several pain behavior items were deleted because children associated the behavior more strongly with things other than pain. The behavior “I crawled” was considered better suited for babies and “I clenched my teeth” with displays of anger. Anger as a class of behavior (i.e. “I said mean words to people” and “I got mad and threw or hit something”) was rarely endorsed to any degree by the children and adolescents in the setting of an individual interview.

Table 4.

Dropped Items and issues discovered in cognitive debriefing

| Item Dropped | Reason(s) |

|---|---|

| I clenched my teeth (B) | 3/6 did not associate this behavior with pain (tended to associate with anger instead). |

| My face looked sad (B) | One child said her face doesn’t only look sad when she’s in pain. 4/6 preferred “it showed on my face” (broader meaning). |

| I had to bend over when I was walking (B) | 3/6 did not understand or like this item. |

| I asked people to not bother me (B) | 2/6 preferred “I asked people to let me be by myself.” |

| I squirmed (B) | Children had difficulty understanding how squirming was related to pain—felt only little kids squirmed. |

| I drew my knees up to my chest (B) | Children denied doing this behavior or felt that doing this behavior would cause more pain. |

| I walked careful (B) | 2/6 had difficulty understanding this item or reported walking carefully was not related to pain. |

| I bit my lips (B) | 4/6 denied doing this behavior when in pain. |

| I thrashed (B) | 4/6 did not know the meaning of the word “thrashed.” |

| I held my body where it hurt (B) | 4/6 preferred “I protected the part of my body that hurt.” Children did not endorse the item or noted that it’s not always possible to hold your body where it hurts (i.e., back). |

| I refused to walk (B) | 4/6 did not like this item—felt that it’s impossible to “refuse” to walk. |

| I crawled (B) | All 6 children reviewing this item denied crawling when in pain. They reported that crawling is for babies or could make pain worse. |

| Heavy (S) | Several children had trouble relating this word to pain. |

| Pressing (S) | 2/6 could not understand the meaning of this word. |

| Freezing (S) | 5/6 did not like this word to describe pain—could not understand how “freezing” is related to pain, felt it was too extreme of a word choice. |

| Piercing (S) | 4/6 did not know the meaning of the word and/or felt the word was not a good descriptor of pain. |

| Cutting (S) | 3/6 did not know the meaning of the word and/or felt the word was not a good descriptor of pain. |

| Gnawing (S) | All 6 children reviewing this item felt it was a difficult word to understand/not a good descriptor of pain. |

| Penetrating (S) | 4/6 did not understand this word/would not use this word to describe pain. |

| Searing (S) | 5/6 did not know the meaning of the word and/or would not use the word to describe their pain. |

| Scalding (S) | 3/6 did not know the meaning of the word and/or would not use the word to describe their pain. |

| Suffocating (S) | 5/6 did not feel this word was a good descriptor of pain. |

| Oppressive (A) | 5/6 did not know the meaning of the word “oppressive.” |

| Scary (A) | 4/6 felt that pain could not be “scary.” |

| Terrifying (A) | Children had similar issues as with “scary.” |

| Vicious (A) | 5/6 did not understand the meaning of the word and/or felt it was not a good descriptor for pain. Several children related the word to villains, dog attacks, etc. rather than pain. |

| Punishing (A) | 3/6 related this item to being punished (grounded, hit) by a person rather than pain. |

(S)=pain quality sensory item; (A)=pain quality affective item; (B)=behavior item

Expert review and item revision

For the purposes of alignment between PROMIS® adult and pediatric item banks, consultant pain experts and study team members of a research project aimed specifically at refining adult PROMIS Pain Quality items were invited to review the list of items. This review resulted in the addition of 13 new items to be tested in a second round of cognitive interviews (see Table 5).

Table 5.

Items Added (interviewee feedback and expert suggestion)

| Pain Behavior | In the past 7 days, when I was in pain |

| I took breaks | |

| I asked for someone to help me. | |

| I told people I couldn’t do things with them. | |

| I told people I couldn’t do my usual chores. | |

| I tried to think of something nice/fun. | |

| I went to sleep. | |

| I had to stop what I was doing. | |

| I got angry at people. | |

| Pain Quality (S) | In the past 7 days, did your pain [feel] |

| Punching? | |

| Twisting? | |

| Move to a different part of your body? | |

| Light? | |

| Electrical? | |

| Pain Quality (A) | In the past 7 days, did your pain ever feel |

| Weird? |

(B) Pain Behavior; (S)=pain quality sensory item; (A)=pain quality affective item.

Also, expert reviews resulted in pain quality items being split into two categories: affective and sensory. This was done for more relevant assignment of response options, as the intensity response choices (‘a little bit,’ ‘somewhat,’ etc.) were appropriate for sensory descriptors but were deemed inappropriate for affective items (pain cannot be ‘somewhat’ excruciating). Response choices for the affective items were thus changed to ‘Yes/No,’ and the item context was modified to read: “In the past 7 days, did your pain ever feel…” Expert review also resulted in the addition of a new response option for pain behavior items: ‘Had no pain’ to avoid administration of unnecessary items if not relevant.

In total, following first round interviews, 27 items were deleted, 14 items were added, and 11 items were modified. Tables 4–6 list items deleted, added, or revised due to both respondent and expert feedback. Following the second round of cognitive interviews, 2 more items were added, 1 was modified, and 3 were deleted. The newly created item “I took breaks” was modified to “I took breaks from what I was doing” because a majority of participants felt it clarified the item meaning. Several new pain quality items generated at the suggestion of the experts were deleted because they were difficult for participants to understand: “punching,” “twisting,” and “light.” A new pain quality item “stressful” was added based on participant feedback. Finally, the research team decided to keep both intensity items “how bad was your usual pain” and “how intense was your average pain” for further investigation in the large scale testing phase due to mixed reviews/preference from participants.

Table 6.

Item Response Options: Original version with options as presented for cognitive interviews and revised version for large scale testing

| Original Version | Revised Version | |

|---|---|---|

|

Pain Behavior |

Never | Almost Never | Sometimes | Often | Almost Always |

Had no pain | Never | Almost Never | Sometimes | Often | Almost Always |

|

Pain Quality (Sensory) |

Not at all | A little bit | A medium amount | A lot| A whole lot versus Not at all | A little bit | Somewhat | Quite a bit | Very much |

Not at all | A little bit | Somewhat | Quite a bit | Very much |

|

Pain Quality (Affective) |

Not at all | A little bit | A medium amount| A lot| A whole lot versus Not at all | A little bit | Somewhat | Quite a bit | Very much |

No | Yes |

| Intensity | [Had] no pain | Mild | Moderate | Severe | Very Severe | No revisions |

The final item pool intended for future large scale testing and calibration with children included 111 items: 47 Pain Behavior items, 59 Pain Quality items (36 sensory and 23 affective), and 5 Pain Intensity items. The final item pool intended for future large scale testing and calibration with parents/guardians included 56 items: 51 proxy pain behavior items, and 5 proxy pain Intensity items.

Discussion

We have described the stepwise qualitative methodology and findings employed in the development and conceptual evaluation of self-reported pediatric pain-quality, -intensity and -behavior items and proxy-reported pain intensity and behavior items for further, psychometric testing and possible inclusion in PROMIS pediatric item banks and pools. First, we evaluated content validity and the overall conceptual fit of the PROMIS Pain sub-domain framework for use with children and adolescents with chronic/recurrent pain conditions by eliciting their experiential accounts and descriptions of pain in semi-structured individual and group interviews. This step also involved interviews with pain researchers and experts to further explore and define the conceptual and operational limits of pain outcomes measurement in children. Second, we conducted a comprehensive, multistep qualitative item review (QIR) process to refine, modify, or discard existing pain-quality, -intensity, and -behavior items, and to create new items where needed.

Our findings confirm that children as young as 8 are able to discuss their experiences of chronic pain in constructive and meaningful ways, and they can effectively self-report dimensions of pain such as its intensity, qualities, and associated behaviors. Children at all ages used a varied vocabulary to describe the affective and sensory qualities, behavioral correlates, and functional impacts of their pain episodes, as detailed in supplementary Tables 1 – 6 and summarized in Figure 2. As noted, child accounts and descriptions of pain experiences from semi-structured interviews predominantly took the form of language and expressions consistent with the PROMIS framework for pain outcomes (intensity/quality/ interference/behavior). The only exception concerned a group of statements that we classified as pain coping behaviors and strategies, including self-distraction or meaning-focused strategies like reappraisal or efforts to address existential questions about self, identity, and stigma. While generally not considered to be clinical “outcomes,” pain coping strategies and self-management techniques and their assessment were also identified by pain experts as being meaningful in the clinical assessment of young chronic pain patients.

In keeping with the PROMIS QIR protocol, we employed cognitive interview techniques to review items and to guide the refinement, modification, deletion or creation of new items. Children and adolescents in this study demonstrated the ability to comprehend the majority of oral and written candidate pain behavior and quality items including many adult items. However, their feedback led to deletion of several items originally sourced from the (adult) McGill Pain Questionnaire (10) due to difficulties in understanding or in the perceived relevance to their pain experience (e.g. penetrating, piercing, cutting, pressing, suffocating, punishing, and vicious). We found other differences in children’s reported understanding of items that underlined the importance of eliciting their input when developing pediatric PROs and that ultimately enhanced the quality of the final item pool (See Figure 1 and Tables 4–6).

While adolescents expressed understanding of pain qualities such as “pulsing,” “excruciating,” and “distressing,” younger children had difficulty verbalizing the meanings of these words. For now, for items where there was some equivocal understanding in the younger ages, these words have been retained for large-scale testing. Empirical results of large scale testing (including study of psychometric properties and evaluation for differential item functioning according to age) will help to determine whether these items will be utilized for all participants in the future, or only for participants within a certain age range. Although gender differences in pain vocabulary were observed (as expected) with girls being more descriptive than boys, no major gender differences were found in expressed understanding of the items.

Participants of all ages could define (e.g. ‘since last Tuesday’) or otherwise demonstrate comprehension of a recall period of 7 days, however younger participants occasionally reverted to discussing their pain in general and needed to be reminded of the recall period by the interviewer. Because the format of the written item already presented the recall period in bold font, there was no other reasonable way to make it more salient. As with any cognitive interview study, the research team had to make judgments about the value of an item being added, dropped, or modified. In some cases, items were kept because children understood the item meaning even though they could not personally relate to the item. For the item “…did your pain [ever] feel unending?” participants understood the meaning of the word “unending,” although two children noted that they did not experience unending pain. Additionally, in some instances words that are commonly used to describe pain were difficult for the children to define or explain (e.g. “tender,” “dull”). The research team determined that these words were necessary to test in a larger sample. Although children generally did not endorse the items “I said mean words to people” and “I got angry and threw or hit something,” experience of anger and irritable mood were divulged by children in the group setting and by parents. These items were thus kept for testing, and final decisions about inclusion will be made based on the psychometric properties of the calibrated items.

It is noteworthy that, overall, children reported greater difficulty understanding pain quality items than they did pain behavior items. Compared to pain quality items, pain behavior items are more concrete in meaning and refer to readily observable behaviors. On the other hand, pain quality items refer to internal/subjective sensations and contain more abstract language with minimal context for deciphering item meaning. This finding is not unexpected considering the substantial variation in cognitive development of children ages 8 to 18. It will be important to evaluate how pain quality items perform in large scale testing in order to create the optimal range of questions for pediatric use.

The sample of participants in this study was demographically diverse. However, a limitation was the somewhat restricted age range of participants with a relatively small number of children ages 8 and 9. This is typical of recurrent/chronic pain clinic samples, but some important findings for this younger age group could have been missed. Additionally, a relatively small number of boys (26.7%) made up the first round interview sample. A larger proportion (52.6%) of boys made up a more gender-balanced second round interview sample. However, we anticipated recruitment of a smaller proportion of male participants given the demographics of the disease populations: children with JIA and chronic pain are disproportionally female (1, 6, 14). Although translatability review was conducted to facilitate future translation and cross-cultural validation, in future research, it would be useful to include populations of children for whom English is not the primary language spoken at home. Also, because 3 people were responsible for conducting these interviews, it is possible that interviewers influenced participants differently, contributing to variation in interviewee feedback. Differences in interviewer style were minimized as much as possible through training, debriefing, and the use of interview guides.

Conclusion

We employed a comprehensive, qualitative interview and item-review methodology to support the development and content validity of PROMIS pediatric Pain-Quality, -Intensity and -Behavior item pools for use by children and adolescents aged 8–17, and by parent proxy for Pain-Intensity and Pain-Behavior items. Interviews with children diagnosed with a variety of chronic/recurrent pain conditions and their parents in combination with interviews with pain research experts allowed us to examine and compare respondents’ experiential, verbal, behavioral and conceptual expressions and understandings of pain and pain communication in relation to the PROMIS pain sub-domain conceptual framework. With exception of a group of statements that we classified as pain coping behaviors and strategies and that represent an area of potential further study as an “outcome,” our findings strongly confirm the content validity and overall conceptual scope and fit of the PROMIS framework for use with children and adolescents with chronic/recurrent pain conditions.

The final item pools generated and refined through the item revision and cognitive interview processes subsequently were subject to large scale calibration testing in children with chronic painful conditions as part of PROMIS® Pediatric Item Bank development. This process will provide a spectrum of validated pediatric pain self-report items including Pain Intensity, Pain Quality, Pain Interference and Pain Behavior that will be publicly available for clinical and research use.

Supplementary Material

Perspective.

PROMIS Pediatric Pain Behavior, Quality and Intensity items were developed based on a theoretical framework of pain that was evaluated by multiple stakeholders in measurement of pediatric pain, including researchers, clinicians, and children with pain and their parents, and the appropriateness of the framework was verified.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures: The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) is an NIH Roadmap initiative to develop a computerized system measuring PROs in respondents with a wide range of chronic diseases and demographic characteristics. PROMIS II was funded by cooperative agreements with a Statistical Center (Northwestern University, PI: David Cella, PhD, 1U54AR057951), a Technology Center (Northwestern University, PI: Richard C. Gershon, PhD, 1U54AR057943), a Network Center (American Institutes for Research, PI: Susan (San) D. Keller, PhD, 1U54AR057926) and thirteen Primary Research Sites which may include more than one institution (State University of New York, Stony Brook, PIs: Joan E. Broderick, PhD and Arthur A. Stone, PhD, 1U01AR057948; University of Washington, Seattle, PIs: Heidi M. Crane, MD, MPH, Paul K. Crane, MD, MPH, and Donald L. Patrick, PhD, 1U01AR057954; University of Washington, Seattle, PIs: Dagmar Amtmann, PhD and Karon Cook, PhD, 1U01AR052171; University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, PI: Darren A. DeWalt, MD, MPH, 2U01AR052181; Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, PI: Christopher B. Forrest, MD, PhD, 1U01AR057956; Stanford University, PI: James F. Fries, MD, 2U01AR052158; Boston University, PIs: Stephen M. Haley, PhD and David Scott Tulsky, PhD (University of Michigan, Ann Arbor), 1U01AR057929; University of California, Los Angeles, PIs: Dinesh Khanna, MD and Brennan Spiegel, MD, MSHS, 1U01AR057936; University of Pittsburgh, PI: Paul A. Pilkonis, PhD, 2U01AR052155; Georgetown University, PIs: Carol. M. Moinpour, PhD (Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle) and Arnold L. Potosky, PhD, U01AR057971; Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, PI: Esi M. Morgan DeWitt, MD, MSCE, 17 1U01AR057940; University of Maryland, Baltimore, PI: Lisa M. Shulman, MD, 1U01AR057967; and Duke University, PI: Kevin P. Weinfurt, PhD, 2U01AR052186). NIH Science Officers on this project have included Deborah Ader, PhD, Vanessa Ameen, MD, Susan Czajkowski, PhD, Basil Eldadah, MD, PhD, Lawrence Fine, MD, DrPH, Lawrence Fox, MD, PhD, Lynne Haverkos, MD, MPH, Thomas Hilton, PhD, Laura Lee Johnson, PhD, Michael Kozak, PhD, Peter Lyster, PhD, Donald Mattison, MD, Claudia Moy, PhD, Louis Quatrano, PhD, Bryce Reeve, PhD, William Riley, PhD, Ashley Wilder Smith, PhD, MPH, Susana Serrate-Sztein, MD, Ellen Werner, PhD and James Witter, MD, PhD.

This manuscript was reviewed by PROMIS reviewers before submission for external peer review.

References

- 1.Adib N, Hyrich K, Thornton J, Lunt M, Davidson J, Gardner-Medwin J, Foster H, Baildam E, Wedderburn L, Thomson W. Association between duration of symptoms and severity of disease at first presentation to paediatric rheumatology: results from the Childhood Arthritis Prospective Study. Rheumatology. 2008;47:991–995. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ken085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amtmann D, Cook KF, Jensen MP, Chen WH, Choi S, Revicki D, Cella D, Rothrock N, Keefe F, Callahan L, Lai JS. Development of a PROMIS item bank to measure pain interference. Pain. 2010;150:173–182. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.04.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cella D, Yount S, Rothrock N, Gershon R, Cook K, Reeve B, Ader D, Fries JF, Bruce B, Rose M. The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS): progress of an NIH Roadmap cooperative group during its first two years. Med Care. 2007;45:S3–S11. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000258615.42478.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DeWalt DA, Rothrock N, Yount S, Stone AA. Evaluation of item candidates: the PROMIS qualitative item review. Med Care. 2007;45:S12–S21. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000254567.79743.e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Forrest CB, Bevans KB, Tucker C, Riley AW, Ravens-Sieberer U, Gardner W, Pajer K. Commentary: The Patient-Reported Outcome Measurement Information System (PROMIS®) for children and youth: application to pediatric psychology. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2012;37:614–621. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jss038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guite JW, Logan DE, Sherry DD, Rose JB. Adolescent self-perception: associations with chronic musculoskeletal pain and functional disability. J Pain. 2007;8:379–386. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2006.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Irwin DE, Varni JW, Yeatts K, DeWalt DA. Cognitive interviewing methodology in the development of a pediatric item bank: a Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) study. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2009;7:3. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-7-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lynch-Jordan AM, Kashikar-Zuck S, Goldschneider KR. Parent perceptions of adolescent pain expression: the adolescent pain behavior questionnaire. Pain. 2010;151:834–842. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.09.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McGrath PJ, Walco GA, Turk DC, Dworkin RH, Brown MT, Davidson K, Eccleston C, Finley GA, Goldschneider K, Haverkos L, Hertz SH, Ljungman G, Palermo T, Rappaport BA, Rhodes T, Schechter N, Scott J, Sethna N, Svensson OK, Stinson J, von Baeyer CL, Walker L, Weisman S, White RE, Zajicek A, Zeltzer L. Core outcome domains and measures for pediatric acute and chronic/recurrent pain clinical trials: PedIMMPACT recommendations. J Pain. 2008;9:771–783. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2008.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Melzack R. The McGill Pain Questionnaire: major properties and scoring methods. Pain. 1975;1:277–299. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(75)90044-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Merskey H, Bogduk N. Part III: Pain Terms, A Current List with Definitions and Notes on Usage (pp 209–214) Classification of Chronic Pain. 2 Edition. Seattle: IASP Task Force on Taxonomy, IASP Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reeve BB, Hays RD, Bjorner JB, Cook KF, Crane PK, Teresi JA, Thissen D, Revicki DA, Weiss DJ, Hambleton RK, Liu H, Gershon R, Reise SP, Lai JS, Cella D. Psychometric evaluation and calibration of health-related quality of life item banks: plans for the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Med Care. 2007;45:S22–S31. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000250483.85507.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Revicki DA, Chen WH, Harnam N, Cook KF, Amtmann D, Callahan LF, Jensen MP, Keefe F. Development and psychometric analysis of the PROMIS pain behavior item bank. Pain. 2009;146:158–169. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.07.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saurenmann RK, Rose JB, Tyrrell P, Feldman BM, Laxer RM, Schneider R, Silverman ED. Epidemiology of juvenile idiopathic arthritis in a multiethnic cohort: ethnicity as a risk factor. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:1974–1984. doi: 10.1002/art.22709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Varni JW, Stucky BD, Thissen D, Dewitt EM, Irwin DE, Lai JS, Yeatts K, DeWalt DA. PROMIS Pediatric Pain Interference Scale: an item response theory analysis of the pediatric pain item bank. J Pain. 2010;11:1109–1119. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2010.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Varni JW, Thompson KL, Hanson V. The Varni Thompson Pediatric Pain Questionnaire .1. Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain in Juvenile Rheumatoid-Arthritis. Pain. 1987;28:27–38. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(87)91056-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilkinson GS, Robertson GJ. Wide Range Achievement Test 4 professional manual. Lutz, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Willis GB. Cognitive Interviewing: A Tool for Improving Questionnaire Design. SAGE Publications; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wong DL, Baker CM. Pain in children: comparison of assessment scales. Pediatric nursing. 1988;14:9–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.