We have identified a novel mechanism by which salt-sensitive hypertension disrupts normal function of the sympathetic nervous system. Antioxidants may be helpful in treating some forms of hypertension.

Keywords: salt-sensitive hypertension, immune activation, sympathetic nervous system, α2-adrenergic autoreceptors, amperometry

Abstract

We tested the hypothesis that vascular macrophage infiltration and O2− release impairs sympathetic nerve α2-adrenergic autoreceptor (α2AR) function in mesenteric arteries (MAs) of DOCA-salt hypertensive rats. Male rats were uninephrectomized or sham operated (sham). DOCA pellets were implanted subcutaneously in uninephrectomized rats who were provided high-salt drinking water or high-salt water with apocynin. Sham rats received tap water. Blood pressure was measured using radiotelemetry. Treatment of sham and DOCA-salt rats with liposome-encapsulated clodronate was used to deplete macrophages. After 3–5, 10–13, and 18–21 days of DOCA-salt treatment, MAs and peritoneal fluid were harvested from euthanized rats. Norepinephrine (NE) release from periarterial sympathetic nerves was measured in vitro using amperometry with microelectrodes. Macrophage infiltration into MAs as well as TNF-α and p22phox were measured using immunohistochemistry. Peritoneal macrophage activation was measured by flow cytometry. O2− was measured using dihydroethidium staining. Hypertension developed over 28 days, and apocynin reduced blood pressure on days 18–21. O2− and macrophage infiltration were greater in DOCA-salt MAs compared with sham MAs after day 10. Peritoneal macrophage activation occurred after day 10 in DOCA-salt rats. Macrophages expressing TNF-α and p22phox were localized near sympathetic nerves. Impaired α2AR function and increased NE release from sympathetic nerves occurred in MAs from DOCA-salt rats after day 18. Macrophage depletion reduced blood pressure and vascular O2− while restoring α2AR function in DOCA-salt rats. Macrophage infiltration into the vascular adventitia contributes to increased blood pressure in DOCA-salt rats by releasing O2−, which disrupts α2AR function, causing enhanced NE release from sympathetic nerves.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY

We have identified a novel mechanism by which salt-sensitive hypertension disrupts normal function of the sympathetic nervous system. Antioxidants may be helpful in treating some forms of hypertension.

increased sympathetic nerve activity contributes to high blood pressure in some animal models of hypertension, including the DOCA-salt model (10, 57). Hypertension in the DOCA-salt model is driven by reduced renal mass (removal of one kidney), high circulating mineralocorticoid levels, and high salt intake (57). Elevated salt increases central sympathetic drive to the cardiovascular system (17, 48), but there are also alterations in the local mechanisms that modulate sympathetic neurotransmission in salt-sensitive hypertension, including impaired function of α2-adrenergic autoreceptors (α2ARs) on sympathetic nerves associated with mesenteric arteries (MAs) (41, 49). α2ARs provide negative feedback control over norepinephrine (NE) release, and MAs are part of the splanchnic circulation, a major resistance arterial bed critical for blood pressure regulation (2, 28, 30). MA diameter (and therefore vascular resistance) is controlled partly by NE released from periarterial sympathetic nerves (51) as removal of the celiac ganglion, which contains the cell bodies of sympathetic nerves supplying MAs, reduces blood pressure in DOCA-salt-treated rats (28). These data indicate that NE released from sympathetic nerves supplying MAs contributes to blood pressure regulation. Impaired function of α2ARs in the mesenteric circulation will increase NE release, MA constriction, and blood pressure (61). Identification of the mechanism by which α2AR function is disrupted will help elucidate the pathophysiology of salt-sensitive hypertension.

The specific factors contributing to DOCA-salt hypertension are time-dependent. Yemane et al. (69) described three phases of DOCA-salt hypertension: 1) an early phase (1–5 days) driven by increased plasma Na+, volume expansion, and circulating vasopressin levels; 2) a developed phase (2–6 wk) driven by increased sympathetic nervous system activity and elevated vasopressin and endothelin-1 levels; and 3) the malignant phase (>6 wk) driven by increased vasopressin, endothelin-1, and vascular and cardiac remodeling. Therefore, studies of the pathophysiology of DOCA-salt hypertension need to consider phase specific variations.

ROS, especially O2−, contribute to the pathophysiology of hypertension (35, 40, 60). This is particularly true for DOCA-salt hypertension as the superoxide dismutase mimetic tempol lowers blood pressure and sympathetic nerve activity in DOCA-salt hypertensive rats (68). A major source of O2− is NADPH oxidase, and increased NADPH oxidase activity contributes to hypertension (60, 70). Macrophage NADPH oxidase has an intracellular p47phox subunit and membrane-bound Nox-1/gp91phox and p22phox subunits (34). Hypertensive stimuli upregulate the p22phox subunit and enzyme activity (70). DOCA-salt mice deficient in NADPH oxidase have reduced blood pressure compared with wild-type DOCA-salt mice (44). Vascular inflammation also contributes to the initiation and development of hypertension (4, 18, 21, 31). Vascular inflammation is due partly to the infiltration of lymphocytes (19, 20, 21, 25, 43) and macrophages (3, 6, 11, 23, 39), which release O2−. A previous study (40) has shown that NADPH oxidase activation by ANG II contributes to hypertension development by activating the sympathetic nervous system via an action in the brain. However, the effects of macrophage infiltration and oxidative stress on the function of periarterial sympathetic nerves have not been studied. This is important because the activation and proliferation of macrophages in the vascular adventitia contributes to inflammation, vascular remodeling, fibrosis, and endothelial dysfunction in hypertension (8, 12, 15, 17, 47). For example, mice deficient in macrophage colony-stimulating factor have reduced vascular inflammation and damage in ANG II-mediated hypertension (11). Furthermore, an antagonist of chemokine (C-C motif) receptor type 2 prevents vascular macrophage infiltration and reduces blood pressure in DOCA-salt mice (5). It is unclear whether macrophage-derived O2− disrupts α2AR function, causing further increases in blood pressure in the DOCA-salt model. In the present study, we tested the hypothesis that there is a time-dependent infiltration of activated macrophages into the adventitia of MAs of DOCA-salt hypertensive rats causing increased vascular O2−, leading to impaired α2AR function. To test this hypothesis, we capitalized on the innate ability of macrophages to engulf cellular debris and pathogens. We introduced liposome-embedded clodronate (Lipo-Clod) to our animal model, which was engulfed by macrophages. Macrophages were subsequently killed by clodronate via apoptosis (63, 64).

METHODS

DOCA-salt hypertension.

All animal use procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Michigan State University. Male Sprague-Dawley rats (∼200 g, Charles River Laboratories, Portage, MI) were acclimated for 5 days before entry into experimental protocols. Rats were anesthetized via isoflurane inhalation; sham-operated (sham) control rats were uninephrectomized and placed on normal tap water. DOCA-salt rats were uninephrectomized, and a DOCA (150 mg)-containing silastic pellet was implanted subcutaneously in the midscapular region. After surgery, all rats received enrofloxacin antibiotic (5 mg/kg im) and carprofen analgesic (5 mg/kg sc). DOCA pellet-implanted rats were placed on high-salt drinking water (1% NaCl + 0.2% KCl) available ad libitum.

Blood pressure measurements and in vivo drug treatments.

In some experiments, blood pressure was measured in conscious rats using the automated CODA rat tail-cuff system (Kent Scientific, Torrington, CT). Rats were restrained and allowed to sit quietly to prewarm for 10 min. The tail cuff was inflated five times to 250 mmHg and slowly deflated over a period of 15 s. Blood pressure was obtained during each inflation cycle by a volume recording sensor. Blood pressure values were an average of five readings.

In some experiments, blood pressure was recorded continuously in conscious unrestrained rats used radiotelemetry. In these experiments, rats were uninephrectomized, and the catheter of a radiotelemetry-based pressure transmitter (TA11PA-D70, DSI) was implanted into the femoral artery and the body of the transmitter was placed subcutaneously at the inner thigh. Rats were allowed 4 days to recover with free access to food and water. Rats were housed in an individual cage on top of a radiotelemetry receiver (RPC-1, DSI) that was connected to a data exchange matrix and computerized data-acquisition program (Dataquest ART 3.0, DSI) to monitor arterial pressure remotely. Mean arterial pressure (MAP) was sampled for 10 s every minute for 24 h. Rats were placed on either high-salt drinking water (1% NaCl + 0.2% KCl, n = 13) or high-salt drinking water containing the NADPH oxidase inhibitor apocynin (2 mM, n = 8) available ad libitum. All rats were fed standard rat chow. On day 3, rats were anesthetized with isoflurane, a DOCA (150 mg)-containing pellet was implanted as described above, and blood pressure monitoring resumed. As the DOCA-salt protocol is used routinely in our laboratory and the model reliably produces hypertension, sham treated rats were not included in the apocynin-treatment protocol.

In macrophage depletion experiments, rats were treated with Lipo-Clod. Clodronate was incorporated into liposomes as previously described (60, 61). Control groups received liposome-encapsulated PBS (Lipo-PBS). After sham or DOCA-salt treatment and radiotelemeter implantation (as described above), Lipo-Clod or Lipo-PBS was injected intravenously at a dose of 50 mg/kg clodronate. Thereafter, 25 mg/kg clodronate was administered intraperitoneally every 7 days. Control rats received 1 ml/kg Lipo-PBS.

Immunohistochemistry.

MAs (diameter: 200–300 μm) from DOCA-salt and sham rats were excised and cleaned of perivascular fat. MAs were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight at 4°C and then permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS (0.1 M, pH 7.2) containing 4% goat serum for 1 h at room temperature. Tissues were then incubated in the same buffer solution but containing the appropriately diluted primary antibodies for 2 h at room temperature followed by a 1-h incubation with the appropriate secondary antibodies (Table 1). MAs were washed three times with 0.1 M PBS between primary and secondary antibody incubations and after secondary antibody incubation. MAs were than mounted on glass microscope slides using Prolong antifade mounting medium (Life Technologies, Grand Isle, NY) and a glass coverslip. Images were acquired using a TCS SL laser scanning confocal microscope (Leica Microsystems, Heidelberg, Germany).

Table 1.

Sources of primary and secondary antibodies and working dilutions

| Primary Antibodies | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antigen | Target | Source | Host Species | Dilution |

| CD163 | Rat CD163 | AbD Serotec | Mouse | 1:200 |

| p22phox | NADPH oxidase | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | Rabbit | 1:400 |

| TNF-α | Inflammatory cytokine | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | Goat | 1:200 |

| Neuropeptide Y | Sympathetic nerves | Amersham Biosciences | Rabbit | 1:200 |

| Secondary Antibodies | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Target Species | Host Species | Conjugated to | Dilution |

| Mouse | Donkey | FITC | 1:50 |

| Rabbit | Donkey | Cy3 | 1:400 |

| Goat | Donkey | Cy3 | 1:400 |

When assessing the levels of expression of CD163, TNF-α, and p22phox using fluorescence microscopy, we measured fluorescence intensity associated with each antigen in five random areas (each 0.1 mm2) from a single MA from each of five sham and five DOCA-salt hypertensive rats. Image acquisition parameters were kept constant across all tissues.

Dihydroethidium staining.

When dihydroethidium (DHE) reacts with O2−, ethidium bromide is formed, and it intercalates into DNA, yielding a red fluorescent signal when excited at 488 nm. MAs were removed from euthanized rats in chilled Krebs-Ringers-HEPES (KRH) solution of the following composition (in mM): 130 NaCl, 1.3 KCl, 2.2 Ca2Cl2, 1.2 MgSO4, 1.2 KH2PO4, 1.0 HEPES, and 0.09 glucose (pH 7.4). MAs were incubated in DHE (2 μM) solution for 1 h at 37°C. After DHE incubation, MAs were washed with Krebs-Ringer-HEPES solution and mounted for microscopy. Confocal fluorescence images were obtained with 488-nm excitation and 560-nm emission wavelengths.

Amperometric measurement of NE release from periarterial sympathetic nerves in vitro.

Tertiary MAs were isolated, cleaned of fat and connective tissue, carefully pinned to the base of a silastic elastomer-lined chamber recording chamber (4-ml volume), and then perfused with warmed (36°C) and oxygenated (95% O2-5% CO2) Krebs buffer [composed of (in mM) 117 NaCl, 4.7 KCl, 2.5 CaCl2, 1.2 MgCl2, 25 NaHCO3, 1.2 NaH2PO4, and 11 dextrose] at a flow rate of 4 ml/min. Tissues were allowed to equilibrate for 1 h before experiments begun.

Continuous amperometry with a carbon fiber microelectrode was used to measure dynamic changes in NE concentration at the blood vessel surface. The carbon fiber microelectrodes were prepared as previously described (49, 50). The electrode was positioned on the surface of the MA using a micromanipulator. This allowed the detection of NE release from nearby release sites on the artery surface as an oxidation current. A mini-Ag/AgCl reference electrode (Cypress Systems, Lawrence, KS), which also served as the counter electrode, was positioned in the chamber. Oxidation currents were recorded using a BioStat multimode potentiostat (ESA Products, Chelmsford, MA). Detection was accomplished at a constant potential of 600 mV versus the Ag/AgCl reference. This applied potential was used to detect NE release elicited by short trains of electrical stimulation (10 Hz, 5 s, 80 V) using a bipolar focal stimulation electrode positioned on the artery surface (49, 50). A control oxidation current in response to nerve stimulation was obtained in each tissue, and either UK-14304 (α2AR receptor agonist) or idazoxan (α2AR receptor antagonist) were then applied by addition to the Krebs solution. The drug solution was perfused for 40 min before the recording of NE oxidation currents.

Isolation of peritoneal macrophages.

Rats were anesthetized with pentobarbital (50 mg/kg ip), and the abdomen was exposed. Peritoneal cells were collected via lavage using 1× Ca2+-free HBSS (Invitrogen-Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY). The cell suspension was centrifuged at 300 g (4°C). Erythrocytes were removed using ACK lysing buffer (Invitrogen-Life Technologies). The total number of viable leukocytes was determined using trypan blue exclusion and an automatic cell counter (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA).

Flow cytometry.

Harvested peritoneal cell suspensions (1 × 106 cells/sample) were treated with Fc Block (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), and macrophages were identified by incubation with anti-CD11b Alexa Fluor- and anti-CD163 RPE-conjugated antibodies (AbD Serotec, Raleigh, NC). Cells were then fixed with Cytofix (BD Biosciences). Data were acquired using a FACSCanto II cell analyzer (BD Biosciences) and analyzed using FlowJo software (version 8.8.6, TreeStar, Ashland, OR).

Drugs.

All drugs were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich Chemical (St. Louis, MO), and concentrated stock solutions were prepared using deionized water. Working dilutions were made in Krebs buffer at the time of the experiment.

Statistics.

Data are presented as means ± SE; n is the number of animals from which the data were obtained. Data were analyzed with Graphpad Prism (version 5.0) using a Student's t-test or one-way or two-way ANOVAs with Bonferonni's post hoc test as appropriate. Nonparametric data were analyzed with a Kruskal-Wallis test. For multivariate anlaysis of flow cytometry data, FlowJo 8.8.6 was used for probability binning comparisons. Differences were considered significant at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Time course of DOCA-salt hypertension: effects of apocynin and Lipo-Clod.

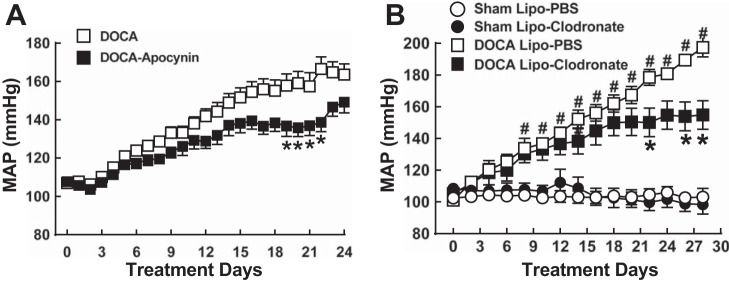

After 5 days of DOCA-salt treatment, MAP increased slightly by days 10–13; it had increased by >20 mmHg and reached a plateau by day 13 in untreated DOCA-salt rats. By day 18, MAP began to increase again and continued to increase until day 25, when the experiment was completed (Fig. 1, A and B). MAP rose with a similar time course in apocynin-treated DOCA-salt rats, but MAP increases were smaller than in untreated DOCA-salt rats. This difference was most prominent between days 17 and 21, where MAP plateaued in untreated DOCA-salt rats (Fig. 1A). Similar increases in MAP occurred in DOCA-salt rats treated with Lipo-PBS, whereas MAP was significantly lower during days 23–28 in DOCA-salt rats treated with Lipo-Clod (Fig. 1B). Lipo-Clod treatment did not affect MAP of sham rats (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Time course of DOCA-salt hypertension development and effects of apocynin (A) and liposome-embedded clodronate (Lipo-Clod; B) treatment. A: DOCA-salt hypertension developed with a biphasic time course. Mean arterial pressure (MAP) rose steadily through day 13 (∼20-mmHg increase) and reached a plateau near day 16. MAP rose again after day 21. DOCA-salt treatment began on day 2 of the protocol. The NADPH oxidase inhibitor apocynin (2 mM in drinking water) reduced blood pressure between days 15 and 21. B: MAP of sham-operated (sham) normotensive and DOCA-salt hypertensive rats treated with liposome-embedded PBS (Lipo-PBS) or Lipo-Clod. Lipo-Clod reduced blood pressure during days 23–28 compared with DOCA-salt rats treated with Lipo-PBS. Lipo-Clod treatment did not affect MAP in sham groups. Data are means ± SEM and were analyzed by two-way ANOVA and a Bonferonni's post hoc test; n = 6–8 for all groups. *,#P < 0.05 vs. DOCA alone (A) or vs. DOCA Lipo-PBS (B).

Time-dependent macrophage infiltration into the adventitia of MAs.

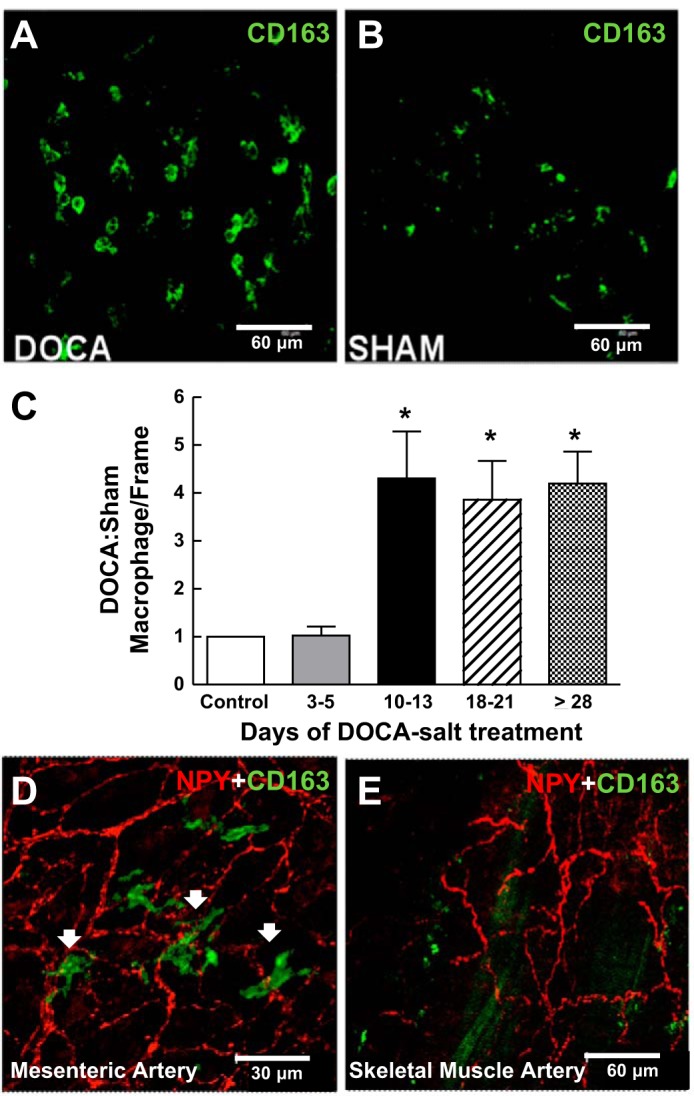

As MAP increased in two phases (an early phase insensitive to apocynin and Lipo-Clod and a later phase sensitive to apocynin and Lipo-Clod), we tested the possibility that macrophage infiltration into MAs might follow a similar biphasic time course. CD163 is a hemoglobin-haptoglobin scavenger receptor expressed by activated macrophages (59). The number of CD163-positive macrophages in the adventitia of DOCA-salt MAs was higher than in arteries from sham control rats on day 28 (Fig. 2, A and B). Macrophage infiltration was first detected between days 10 and 13 and remained high through day 28 (Fig. 2C). Some macrophages were in close apposition to perivascular sympathetic nerves identified by neuropeptide Y immunoreactivity (Fig. 2D). This response was specific for MAs as we did not detect adventitial macrophages in abdominal skeletal muscle arteries (Fig. 2E).

Fig. 2.

Time-dependent macrophage infiltration into the adventitia of mesenteric arteries (MAs) but not skeletal muscle arteries of DOCA-salt hypertensive rats. A and B: whole mount immunohistochemical labeling of CD163-positive macrophages in the adventitia of MAs from DOCA-salt (A) and sham control rats (day 21; B). C: normalized number of macrophages per region. Macrophage numbers were four to five times higher in arteries from DOCA-salt rats compared with those from sham control rats beginning on days 10–13. Data are means ± SE and were analyzed by one-way ANOVA and a Bonferonni's post hoc test; n = 5. *P < 0.05 vs. control and days 3–5. D and E: whole mount immunohistochemical labeling of MA (D) and skeletal muscle (E) perivascular sympathetic nerves labeled by neuropeptide Y (NPY) immunoreactivity along with macrophage labeling with anti-CD163. Macrophages were found in close proximity to periarterial sympathetic nerves in MAs but not skeletal muscle arteries from DOCA-salt rats.

Time-dependent increase in O2− levels in the adventitia of MAs.

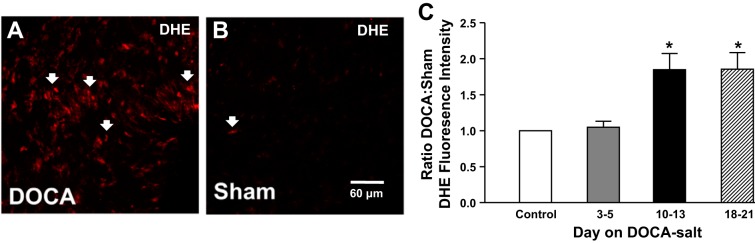

The relative level of O2− (measured using DHE fluorescence) in the adventitia was significantly higher in MAs from DOCA-salt rats compared with sham rats on day 10 (Fig. 3, A and B). Semiquantification of O2− revealed that DHE-derived fluorescence intensity increased in DOCA-salt rats relative to sham control rats starting on day 10 and remained high through day 21 (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3.

Detection of O2− in the adventitia of MAs. A and B: photomicrographs showing dihydroethidium (DHE; arrows) fluorescence in MAs from DOCA-salt (A) and sham control (B) rats. C: normalized mean DHE fluorescence intensity showing twofold higher DHE labeling in DOCA-salt compared with sham control MAs beginning after day 10 of DOCA-salt hypertension. Data are means ± SE and were analyzed by one-way ANOVA and a Bonferonni's post hoc test; n = 5. *P < 0.05 vs. control and days 3–5.

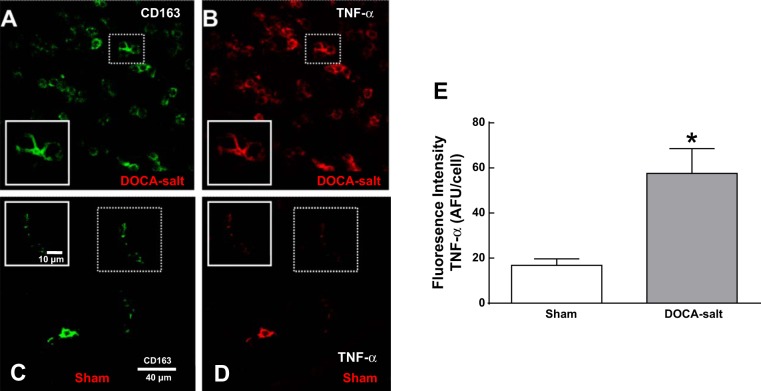

Adventitial macrophages in DOCA-salt MAs express high levels of TNF-α.

On day 21, adventitial macrophages in DOCA-salt MAs expressed higher levels of TNF-α compared with those found in MAs from sham rats (Fig. 4, A–D). TNF-α expression in macrophages was evaluated semiquantitatively, and we found that adventitial macrophages from DOCA-salt MAs expressed higher levels of TNF-α than those in MAs from sham rats (Fig. 4E).

Fig. 4.

Macrophages in the adventitia of MAs of DOCA-salt rats express high levels of TNF-α. A–D: whole mount immunohistochemical labeling of CD163-positive and TNF-α in MAs from DOCA-salt (A and B) and sham control (C and D) rats on day 21. E: mean macrophage TNF-α fluorescence intensity was three times higher in DOCA-salt MA adventitial macrophages compared with that in MAs from sham control rats. AFU, arbitrary fluorescence units. Data are means ± SE; n = 5 rats/group. *P < 0.05 vs. sham rats.

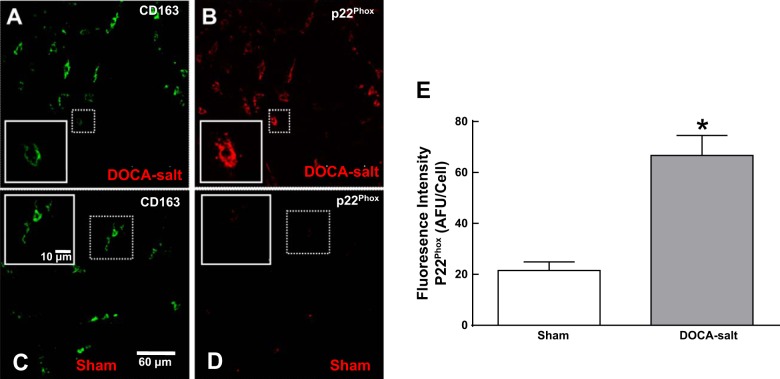

Increased expression of p22phox by adventitial macrophages in MAs of DOCA-salt rats.

CD163-positive macrophages in the adventitia of MAs from DOCA-salt rats expressed higher levels of the NADPH oxidase subunit p22phox (Fig. 5, A and B). There was relatively little p22phox expression in adventitial macrophages from sham rats (Fig. 5, C and D). Semiquantitative analysis of fluorescence intensity showed higher expression of p22phox in macrophages in MAs from DOCA-salt rats compared with those from sham rats (Fig. 5E).

Fig. 5.

Macrophages in the adventitia of MAs of DOCA-salt rats express elevated levels of p22phox. A–D: whole mount immunohistochemical labeling of macrophages positive for CD163 and p22phox in MAs from a DOCA-salt hypertensive rat (A and B) and a sham control rat (C and D) on day 21. E: mean macrophage p22phox fluorescence intensity showing three times higher levels in DOCA-salt MAs compared with those from control rats. Data are means ± SE; n = 5 rats/group. *P < 0.05 vs. sham rats.

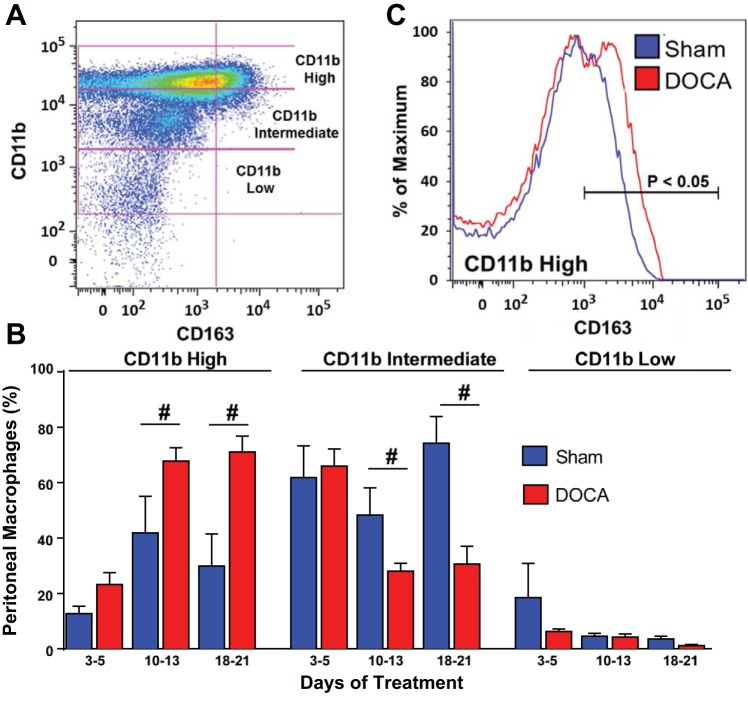

Time-dependent activation of peritoneal macrophages.

CD11b is an integrin protein expressed by activated macrophages (25). Using flow cytometry, we detected three populations of peritoneal macrophages: CD11b low, CD11b intermediate, and CD11b high (Fig. 6A). On days 3–5, there were no differences in the proportions of CD11b low, intermediate, or high macrophages between samples taken from sham versus DOCA-salt rats (Fig. 6B). By day 10 and continuing through day 21, sham rats had a significantly lower percentage of CD11b high macrophages and a significantly higher percentage of CD11b intermediate macrophages (Fig. 6B). CD11b high macrophages from DOCA-salt rats also expressed a higher level of CD163 compared with those from sham control rats (Fig. 6C).

Fig. 6.

Flow cytometry analysis of the time course of peritoneal macrophage activation in DOCA-salt hypertensive rats. A: dot plot of DOCA-salt hypertensive peritoneal macrophages showing three populations of macrophages: CD11b low, intermediate, and high on day 21 of DOCA-salt hypertension. B: the percentage of CD11b high macrophages was significantly higher in DOCA-salt MAs beginning on days 10–13. The percentage of CD11b intermediate macrophages was lower in DOCA-salt compared with sham MAs during the same time period. There were no changes in the CD11b low macrophage population. Data are means ± SE and were analyzed using a Kruskal-Wallis test; n = 5. #P < 0.05 vs. sham rats. C: CD163 fluorescence intensity histogram of the CD11b high macrophage population showing the higher expression of CD163 in DOCA-salt compared with sham control MAs.

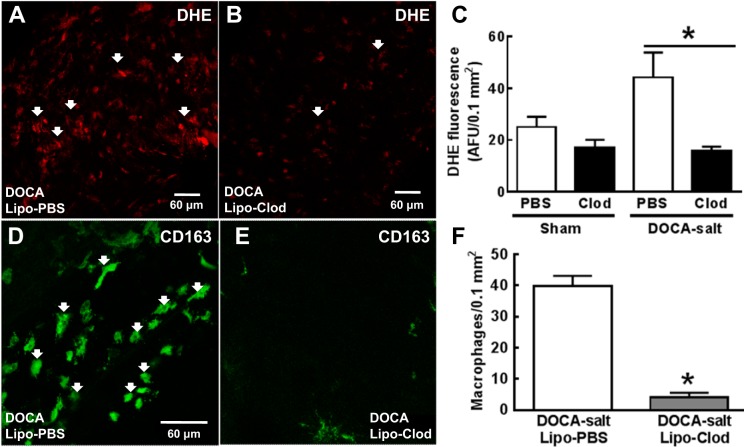

Lipo-Clod depleted macrophages.

Using DHE fluorescence, we found that relative levels of O2− in MAs of DOCA-salt rats treated with Lipo-Clod were lower than in DOCA-salt rats treated with Lipo-PBS (Fig. 7, A and B). Semiquantification of O2− levels revealed that the levels of O2− in MAs of DOCA-salt rats treated with Lipo-Clod were significantly lower than in DOCA-salt rats treated with Lipo-PBS (Fig. 7C). Lipo-Clod also reduced the baseline levels of O2− in control rats (Fig. 7C). The number of CD163-positive macrophages in the adventitia of MAs from DOCA-salt rats treated with Lipo-Clod was significantly lower than DOCA-salt rats treated with Lipo-PBS (Fig. 7, D–F).

Fig. 7.

Lipo-Clod treatment reduces adventitial O2− and macrophage infiltration in MAs from DOCA-salt rats. A: photomicrograph showing DHE fluorescence in a MA from a DOCA-salt rat treated with Lipo-PBS. B: photomicrograph showing DHE fluorescence in a MA from a DOCA-salt rat treated with Lipo-Clod. C: semiquantitative measurement of DHE fluorescence intensity in MAs of DOCA-salt rats treated with Lipo-PBS or Lipo-Clod. Data are means ± SE; n = 5 rats/group. *P < 0.05. D: whole mount immunohistochemical labeling of CD163-positive marcrophages in the adventitia of DOCA-salt rats treated with Lipo-PBS. E: there were fewer CD163-positive macrophages in the adventitial of MAs from DOCA-salt rats treated with Lipo-Clod. F: the mean number of adventitial macrophages in MAs from Lipo-Clod-treated DOCA-salt rats was lower than that in MAs from Lipo-PBS-treated DOCA-salt rats. Data are means ± SEM and were analyzed by a Mann-Whitney test; n = 5. *P < 0.05.

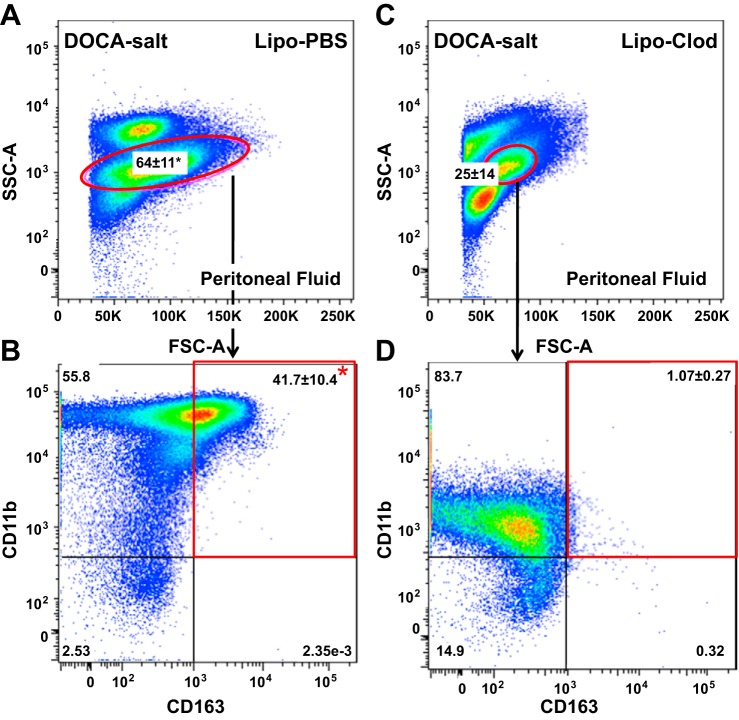

Using flow cytometry, we found that the percentage of peritoneal macrophages detected in DOCA-salt rats treated with Lipo-CLod was significantly lower than in DOCA-salt rats treated Lipo-PBS (Fig. 8, A and B). With further gating on the peritoneal macrophage population, we found that Lipo-Clod reduced the number of CD11b-positive/CD163-positive peritoneal macrophages in DOCA-salt rats (Fig. 8, C and D).

Fig. 8.

Flow cytometry dot plots of peritoneal macrophages from DOCA-salt rats treated with Lipo-PBS or Lipo-Clod. A: macrophages isolated from the peritoneal fluid from DOCA-salt rats treated with Lipo-PBS. B: CD11b/CD163 expression by macrophages from DOCA-salt rats treated with Lipo-PBS. C: macrophages isolated from the peritoneal fluid from DOCA-salt rats treated with Lipo-Clod. There were significantly fewer macrophages compared with DOCA-salt rats treated with Lipo-PBS. D: the percentage of activated (CD11b-positive/CD163-positive) peritoneal marcrophages was significantly lower in DOCA-salt rats treated with Lipo-Clod. Data are means ± SE and were analyzed by a Kruskal-Wallis' test; n = 5 rats/group. *P < 0.05. Dot plots are a concatenated analysis of 5 rats/group.

Lipo-Clod restores the function of prejunctional α2ARs in MAs from DOCA-salt hypertensive rats.

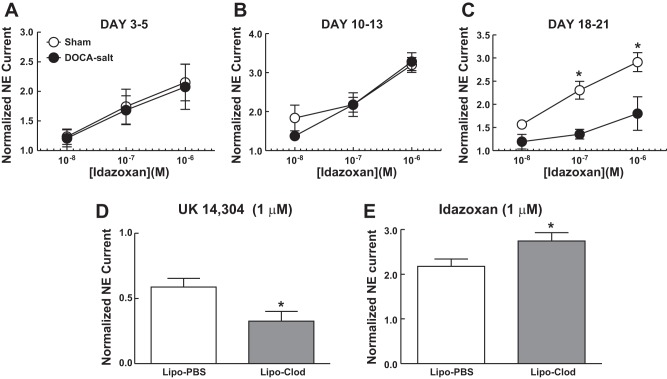

We used idazoxan (α2AR antagonist)-induced facilitation of NE release as a measure of α2AR function. Blockade of the prejunctional α2AR increases the amplitude of NE oxidation current (11). In the early stages of hypertension development (days 3–5 and 10–13), idazoxan increased NE oxidation current equally well in MAs from sham and DOCA-salt rats (Fig. 9, A and B). However, by days 18–21, when DOCA-salt hypertension had established, idazoxan-induced enhancement of NE oxidation current was reduced compared with that in sham control MAs (Fig. 9C).

Fig. 9.

Time-dependent impairment of α2-adrenergic autoreceptor (α2AR) function and restoration by Lipo-Clod treatment of DOCA-salt hypertensive rats. Idazoxan, an α2AR antagonist, increased norepinephrine (NE) oxidation currents equally well in MAs from sham control and DOCA-salt rats on days 3–5 (A) and days 10–13 (B). Idazoxan-induced enhancement of the oxidation current was significantly reduced in MAs from DOCA-salt rats on days 18–21 (C). Data are means ± SE and were analyzed by two-way ANOVA and a Bonferonni's post hoc test; n = 5 rats/group. *P < 0.05 vs. DOCA-salt MAs. D: on days 23–25, UK-14304 (1 μM), an α2AR agonist, decreased NE oxidation current in DOCA-salt rats treated with Lipo-PBS and Lipo-Clod, but this effect was larger in treated rats. E: idazoxan (1 μM) induced an increase in normalized NE oxidation current in DOCA-salt rats treated with Lipo-PBS and Lipo-Clod, but this effect was significantly greater Lipo-Clod-treated DOCA-salt rats. Data are means ± SE and were analyzed by a Student's t-test; n = 5 rats/group. *P < 0.05 vs. Lipo-PBS. Nerve stimulation: 10 Hz, 5 s, 80V.

We tested if macrophage depletion in DOCA-salt rats would restore the function of prejunctional α2ARs in established DOCA-salt hypertension (>day 21) by testing the effects of UK-14304 and idazoxan in MAs from Lipo-PBS- and Lipo-Clod-treated rats. At low concentrations of both drugs (0.01 and 0.1 μM), there were no differences in oxidation currents between tissues obtained from Lipo-PBS- and Lipo-Clod-treated DOCA-salt rats. However, UK-14304 (1 μM) produced a larger inhibition in DOCA-salt rats treated with Lipo-Clod (Fig. 9D). Similarly, idazoxan (1 μM) increased NE oxidation currents in MAs from DOCA-salt rats treated with Lipo-PBS, but idazoxan produced a much larger increase in MAs from Lipo-Clod-treated DOCA-salt rats (Fig. 9E). These pharmacological data indicate that macrophage depletion minimizes α2AR dysfunction in DOCA-salt rats.

DISCUSSION

The results from this study indicate that 1) DOCA-salt hypertension develops with a biphasic time course; 2) the initial elevation of blood pressure recruits macrophages, which are a source of O2− in the adventitia of MAs; 3) sustained increases in vascular O2− impair α2AR function, leading to increased NE release from periarterial sympathetic nerves; and 4) macrophage depletion attenuates the development of the later phase of DOCA-salt hypertension and restores α2AR function by reducing vascular O2−. We propose that the modest increase in blood pressure during the early stage of DOCA-salt hypertension causes vascular damage and neoantigen formation. These changes lead to macrophage infiltration into the vascular adventitia and initiation of an inflammatory response that results in a dysregulation of NE release from periarterial sympathetic nerves and further increases in blood pressure. There is substantial evidence pointing to increased sympathetic nerve activity in DOCA-salt hypertension. For example, there is increased lumbar sympathetic nerve activity (48), increased circulating plasma catecholamines (5), and greater decreases in blood pressure caused by ganglion blockade (15). In addition, removal of the celiac ganglion (which provides sympathetic innervation of the splanchnic circulation) lowers blood pressure in DOCA-salt rats (28). In addition to the increase in sympathetic nerve activity, local changes at the level of the vascular neuroeffector junction may also contribute to increased sympathetically mediated vasoconstriction in DOCA-salt hypertension. These changes include impaired function of the prejunctional α2AR, which regulates neurotransmitter release from sympathetic nerve fibers (12, 41, 49).

Immune activation in hypertension.

Hypertension is a multiorgan disease that involves activation of the immune system and vascular inflammation (13, 21, 37, 53, 58, 65). Mice lacking T and B cells have blunted hypertension and do not develop vascular remodeling during ANG II infusion or DOCA-salt treatment, whereas adoptive transfer of T cells, but not B cells, restores these changes (19). In addition to lymphocytes, macrophage infiltration into blood vessels as well as the brain, heart, and kidneys also contribute to the pathophysiology of hypertension and its consequences (23). Macrophage accumulation in the vascular wall during hypertension contributes to oxidative stress, endothelial dysfunction, and inflammation (14, 16, 44). Although hypertension involves inflammation and periarterial sympathetic nerve dysfunction, the interaction among inflammatory mechanisms and sympathetic nerve function (particularly at the vascular neuroeffector junction) and hypertension is poorly understood.

One component of vascular inflammation in hypertension is the accumulation of high levels of ROS, including O2− (8, 68). Adventitial fibroblasts are one source of O2− (8), but activated macrophages express high levels of NADPH oxidase, an enzyme that produces O2−, suggesting that adventitial macrophages are a source of vascular O2− (5). Macrophages are phagocytic cells that release O2− in response to a variety of stimuli (3, 11). We show here that perivascular macrophages contribute to the increased levels of O2− in the adventitia of MAs, as macrophage depletion using Lipo-Clod reduced vascular O2− in DOCA-salt rats.

In the present study, we examined two macrophage markers: CD163 and CD11b. Macrophages in the adventitial layer of MAs from DOCA-salt rats with established hypertension expressed high levels of CD163, a hemoglobin/haptoglobin scavenger receptor (52). CD163 expression is typically associated with alternative activation of macrophages and an anti-inflammatory response (47). However, CD163 activation is also linked to an upregulation of inflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α (52). CD11b is an integrin αM-subunit that forms the heterodimeric integrin αMβ2 molecule (59). αMβ2 is a cell surface receptor expressed by many leukocytes, including macrophages. αMβ2 is linked to the activation of NF-κB, which upregulates proinflammatory cytokines (38, 42). While we did not measure the coexpression of CD11b and TNF-α, we did find that CD163-positive macrophages in the adventitia of MAs of DOCA-salt hypertensive rats expressed elevated levels of TNF-α. High levels of TNF-α would enhance the inflammatory response in the blood vessel wall, leading to vascular injury. Vascular macrophage infiltration may be somewhat specific for the splanchnic circulation as we found macrophages in MAs but not in skeletal muscle arteries. Macrophage infiltration into the wall of mesenteric resistance arteries is a common finding in DOCA-salt and ANG II-induced systemic hypertension (11, 31, 36). Macrophage infiltration into the wall of the pulmonary artery also occurs in animal models of pulmonary hypertension (45). Others (5, 31, 54) have found that macrophages infiltrate into the wall of the thoracic aorta in DOCA-salt, ANG II-infused, and stroke-prone spontaneously hypertensive rats, so the macrophage response may not be specific for MAs; however, macrophage infiltration into resistance arteries, other than MAs, has not been reported to our knowledge. In addition, other investigators used different macrophage/monocyte marker (F4/80, CD63, and MOMA-2) antibodies to identify aortic macrophages. We used CD163 as a macrophage marker, which might identify a different macrophage subpopulation (7). In addition, macrophages infiltrating into the adventitia of MAs may come from the large population of peritoneal macrophages. Our data showed that, like macrophages in the MA adventitia, peritoneal macrophages expressed CD163 and hypertension upregulated the expression of CD163. Furthermore, peritoneal macrophages express the αMβ2-integrin cell adhesion molecule, and intergrin expression is upregulated in hypertensive rats. Most interestingly, the time at which the peritoneal macrophage intergrins are upregulated in the hypertensive animals was similar to that of macrophage infiltration into the mesenteric adventitia. It is tempting to speculate that these integrin adhesion molecules contribute to the recruitment and attachment of macrophages to sites of inflammation (32) and that increased αMβ2-integrin expression enhanced the attachment of peritoneal macrophages to the adventitia of MAs. The somewhat selective macrophage infiltration into the adventitia of MAs with subsequent disruption of α2AR function may be sufficient to alter systemic blood pressure. The sympathetic nerve supply of the mesenteric circulation is critical for the regulation of systemic blood pressure, as discussed in more detail below.

α2AR impairment is caused by O2−.

Many animal and clinical studies have shown an increase in O2− production during hypertension (9, 34, 35, 44, 60, 68). Vascular O2− is produced primarily by NADPH oxidase (39). Under physiological conditions, O2− is maintained at a low level by the enzymes superoxide dismutase, catalase, and glutathione peroxidase. However, in hypertension, there is increased O2−, which activates signaling pathways involved in smooth muscle cell growth and proliferation and inflammation (39). Uncontrolled O2− causes cellular damage and eventually apoptosis, because O2− damages proteins, lipids, and DNA (20). O2− is a reactive and short-lived molecule. However, we showed that some macrophages are in close apposition with sympathetic nerves supplying MAs, which could allow O2− to disrupt α2AR function. α2ARs couple to inhibition of NE release by activation of the Go subtype of G protein with subsequent inhibition of activation of the Ca2+ channels needed for neurotransmitter release (27). Inhibition of Ca2+ channel function is caused by binding of the β-γ subunit of the G protein directly to the channel (55). ROS can directly disrupt G protein-coupled receptor signaling. For example, the oxidant molecule H2O2 causes G protein uncoupling from the D1-dopamine receptor in renal proximal tubule cells maintained in cell culture (1). Thus, a possible mechanism of O2− disruption of α2R function is through receptor-G protein-effector uncoupling. This proposed general mechanism is supported by our recent data showing that the function of prejunctional A1 adenosine receptors on periarterial sympathetic nerves is also impaired in DOCA-salt hypertensive rats (56).

We have previously shown that apocynin [a drug that can block NADPH oxidase (51)]-treated DOCA-salt rats with established hypertension (>day 21) reduced MA and sympathetic ganglion O2− levels and improved α2AR function (12). In the present study, we show that chronic apocynin treatment reduced blood pressure in the later phase (>day 21) of DOCA-salt hypertension. This suggests that the later phases of DOCA-salt hypertension may be exacerbated by oxidative damage of α2AR and/or its signaling pathway in perivascular sympathetic nerves, resulting in increased NE release.

Our study supports the hypothesis that macrophage-derived O2− disrupts α2AR function because depletion of macrophages restores its function. Inflammation through recruitment, activation, and proliferation of macrophages in the vascular adventitia is part of the pathophysiology of hypertension (39), as mice deficient in macrophage colony-stimulating factor exhibit reduced vascular inflammation and are protected against the damage caused by DOCA-salt hypertension (11). Our data suggest that one putative protective mechanism is the prevention of impaired α2AR function.

Impaired function of α2ARs is not specific for DOCA-salt hypertension or MAs. There is an increase in circulating catecholamines in DOCA-salt rats due to reduced α2AR function, and this would come from sympathetic nerves supplying multiple organ systems as well as the adrenal gland (47). α2AR function is also reduced in sympathetic nerves supplying the caudal artery and portal vein of spontaneously hypertensive rats (66, 67) and the heart of Dahl salt-sensitive hypertensive rats (24). Although impaired α2AR function is not specific for the mesenteric circulation, removal of the celiac ganglion attenuates hypertension in DOCA-salt rats (24). The celiac ganglion provides much of the sympathetic nerve supply of the mesenteric circulation, which plays a key role in the regulation of systemic blood pressure. Impaired α2AR function is also only one component of the overall pathophysiology of DOCA-salt hypertension and probably contributes to the developed phase (>2 wk) of DOCA-salt hypertension (69), when increased sympathetic nervous system activity is a major contributor to blood pressure elevation.

Conclusions.

The present study suggests that inflammatory mechanisms play an important role in blood pressure regulation through their effect on sympathetic nerve function. In the future, it is possible that vascular macrophage markers could be used in patients with hypertension to identify those at risk for long-term changes in sympathetic nerve function or as a target for antihypertensive treatment.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant HL-070687. L. V. Thang was supported by PhRMA Paul Calabresi Medical Student Fellowship, Spectrum Health Fellowship, and the Gates Millennium Fellowship.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: L.V.T., S.L.D., G.M.S., and J.J.G. conception and design of research; L.V.T., S.L.D., and R.C. performed experiments; L.V.T., S.L.D., N.E.K., G.M.S., and J.J.G. analyzed data; L.V.T., S.L.D., N.E.K., G.M.S., and J.J.G. interpreted results of experiments; L.V.T., N.E.K., and J.J.G. prepared figures; L.V.T. drafted manuscript; L.V.T., S.L.D., N.E.K., G.M.S., N.v.R., and J.J.G. edited and revised manuscript; L.V.T., S.L.D., R.C., N.E.K., G.M.S., N.v.R., and J.J.G. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Asghar M, Banday AA, Fardoun RZ, Lokhandwala MF. Hydrogen peroxide causes uncoupling of dopamine D1-like receptors from G proteins via a mechanism involving protein kinase C and G-protein-coupled receptor kinase 2. Free Radic Biol Med 40: 13–20, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Averina VA, Othmer HG, Fink GD, Osborn JW. A new conceptual paradigm for the haemodynamics of salt-sensitive hypertension: a mathematical modelling approach. J Physiol 590: 5975–5992, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barin JG, Rose NR, Cihakova D. Macrophage diversity in cardiac inflammation: a review. Immunobiology 217: 468–475, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bouvier M, de Champlain J. Increased basal and reactive plasma norepinephrine and epinephrine levels in awake DOCA-salt hypertensive rats. J Auton Nerv Syst 15: 191–195, 1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chan CT, Moore JP, Budzyn K, Guida E, Diep H, Vinh A, Jones ES, Widdop RE, Armitage JA, Sakkal S, Ricardo SD, Sobey CG, Drummond GR. Reversal of vascular macrophage accumulation and hypertension by a CCR2 antagonist in deoxycorticosterone/salt-treated mice. Hypertension 60: 1207–1212, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clozel M, Kuhn H, Hefti F, Baumgartner HR. Endothelial dysfunction and subendothelial monocyte macrophages in hypertension - effect of angiotensin converting enzyme-inhibition. Hypertension 18: 132–141, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cassado Ados A, D'Império Lima MR, Bortoluci KR. Revisiting mouse peritoneal macrophages: heterogeneity, development, and function. Front Immunol 6: 225, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Csányi G, Taylor WR, Pagano PJ. NOX and inflammation in the vascular adventitia. Free Radic Biol Med 47: 1254–66, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dai X, Galligan JJ, Watts SW, Fink GD, Kreulen DL. Increased O2− production and upregulation of ETB receptors by sympathetic neurons in DOCA-salt hypertensive rats. Hypertension 43: 1048–1054, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.deChamplain J, Bouvier M, Drolet G. Abnormal regulation of the sympathoadrenal system in deoxycorticosterone acetate salt hypertensive rats. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 65: 1605–1614, 1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Ciuceis C, Amiri F, Brassard P, Endemann DH, Touyz RM, Schiffrin EL. Reduced vascular remodeling, endothelial dysfunction, and oxidative stress in resistance arteries of angiotensin II-infused macrophage colony-stimulating factor-deficient mice: evidence for a role in inflammation in angiotensin-induced vascular injury. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 25: 2106–2113, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Demel SL, Dong H, Swain GM, Wang X, Kreulen DL, Galligan JJ. Antioxidant treatment restores prejunctional regulation of purinergic transmission in mesenteric arteries of deoxycorticosterone acetate-salt hypertension rats. Neuroscience 168: 335–345, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dorffel Y, Latsch C, Stuhlmuller B, Schreiber S, Scholze S, Burmester GR, Scholze J. Preactivated peripheral blood monocytes in patients with essential hypertension. Hypertension 34: 113–117, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.El Kasmi KC, Pugliese SC, Riddle SR, Poth JM, Anderson AL, Frid MG, Li M, Pullamsetti SS, Savai R, Nagel MA, Fini MA, Graham BB, Tuder RM, Friedman JE, Eltzschig HK, Sokol RJ, Stenmark KR. Adventitial fibroblasts induce a distinct proinflammatory/profibrotic macrophage phenotype in pulmonary hypertension. J Immunol 193: 597–609, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fink GD, Johnson RJ, Galligan JJ. Mechanisms of increased venous smooth muscle tone in desoxycorticosterone acetate-salt hypertension. Hypertension 35: 464–469, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gomolak JR, Didion SP. Angiotensin II-induced endothelial dysfunction is temporally linked with increases in interleukin-6 and vascular macrophage accumulation. Front Physiol 5: 396, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grassi G. Assessment of sympathetic cardiovascular drive in human hypertension achievements and perspectives. Hypertension 54: 690–697, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grundy SM. Inflammation, hypertension, and the metabolic syndrome. JAMA 290: 3000–3002, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guzik TJ, Hoch NE, Brown KA, McCann LA, Rahman A, Dikalov S, Goronzy J, Weyand C, Harrison DG. Role of the T cell in the genesis of angiotensin II induced hypertension and vascular dysfunction. J Exp Med 204: 2449–2460, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hare JM. Nitroso-redox balance in the cardiovascular system. N Engl J Med 351: 2112–2114, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harrison DG, Guzik TJ, Goronzy J, Weyand C. Is hypertension an immunologic disease? Curr Cardiol Rep 6: 464–469, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.He K, Nukada H, McMorran PD, Murphy MP. Protein carbonyl formation and tyrosine nitration as markers of oxidative damage during ischaemia-reperfusion injury to rat sciatic nerve. Neuroscience 94: 909–916, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hilgers KF. Monocytes/macrophages in hypertension. J Hypertens 20: 593–596, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hirano Y, Tsunoda M, Shimosawa T, Matsui H, Fujita T, Funatsu T. Suppression of catechol-O-methyltransferase activity through blunting of α2-adrenoceptor can explain hypertension in Dahl salt-sensitive rats. Hypertens Res 30: 269–278, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hoch NE, Guzik TJ, Chen W, Deans T, Maalouf SA, Gratze P, Weyand C, Harrison DG. Regulation of T-cell function by endogenously produced angiotensin II. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 296: R208–R216, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hoch H, Hering L, Crowley S, Zhang J, Yang G, Rump LC, Vonend O, Stegbauer J. Sympathetic nervous system drived renal inflammation by α2A adrenoceptors. J Hypertens 33, Suppl 1: e118, 2015.26102701 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ikeda SR, Dunlap K. Voltage-dependent modulation of N-type calcium channels: role of G-protein subunits. Adv Second Messenger Phosphoprotein Res 33: 131–151, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kandilkar SS, Fink GD. Splanchnic nerves in the development of mild DOCA-salt hypertension. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 301: H1965–H1973, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kataru RP, Jung K, Jang C, Yang H, Schwendener RA, Baik JE, Han SH, Alitalo K, Koh GY. Critical role of CD11b+ macrophages and VEGF in inflammatory lymphangiogenesis, antigen clearance, and inflammation resolution. Blood 113: 5650–5659, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.King AJ, Osborn JW, Fink GD. Splanchnic circulation is a critical neural target in angiotensin II salt hypertension in rats. Hypertension 50: 547–556, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ko EA, Amiri F, Pandey NR, Javeshghani D, Leibovitz E, Touyz RM, Schiffrin EL. Resistance artery remodeling in deoxycorticosterone acetate-salt hypertension is dependent on vascular inflammation: evidence from m-CSF-deficient mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 292: H1789–H1795, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Krieglstein CF, Granger DN. Adhesion molecules and their role in vascular disease. Am J Hypertens 14: 44S–54S, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lambeth JD. Nox enzymes and the biology of reactive oxygen. Nat Rev Immunol 4: 181–189, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Landmesser U, Cai H, Dikalov S, McCann L, Hwang J, Jo H, Holland SM, Harrison DG. Role of p47phox in vascular oxidative stress and hypertension caused by angiotensin II. Hypertension 40: 511–515, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Landmesser U, Dikalov S, Price SR, McCann L, Fukai T, Holland SM, Mitch WE, Harrison DG. Oxidation of tetrahydrobiopterin leads to uncoupling of endothelial cell nitric oxide synthase in hypertension. J Clin Invest 11: 1201–1209, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lemkens P, Nelissen J, Meens MJ, Fazzi GE, Janssen GJ, Debets JJ, Janssen BJ, Schiffers PM, De Mey JG. Impaired flow-induced arterial remodeling in DOCA-salt hypertensive rats. Hypertens Res 35: 1093–1101, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Libby P, Ridker PM, Maseri A. Inflammation and atherosclerosis. Circulation 105: 1135–1143, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lin TH, Rosales C, Mondal K, Bolen JB, Kaskill S, Juliano RL. Integrin-mediated tyrosine phosphorylation and cytokine message induction in monocytic cells: a possible signaling role for the Syk tyrosine kinase. J Biol Chem 270: 16189–16197, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu J, Yang F, Yang XP, Jankowski M, Pagano PJ. NAD(P)H oxidase mediates angiotensin ii-induced vascular macrophage infiltration and medial hypertrophy. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 23: 776–782, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lob HE, Schultz D, Marvar PJ, Davisson RL, Harrison DG. Role of the NADPH oxidases in the subfornical organ in angiotensin II-induced hypertension. Hypertension 61: 382–387, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Luo M, Fink GD, Lookingland KJ, Morris JA, Galligan JJ. Impaired function of α2-adrenergic autoreceptors on sympathetic nerves associated with mesenteric arteries and veins in DOCA-salt hypertension. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 286: H1558–H1564, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McGilvray ID, Lu Z, Wei AC, Rothstein OD. MAP-kinase dependent induction of monocytic procoagulant activity by β2-integrins. J Surg Res 188: 1267–1275, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Marvar PJ, Thabet SR, Guzik TJ, Lob HE, McCann LA, Weyand C, Gordon FJ, Harrison DG. Central and peripheral mechanisms of T-lymphocyte activation and vascular inflammation produced by angiotensin II-induced hypertension. Circ Res 107: 263–270, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Matsuno K, Yamada H, Iwata K, Jin D, Katsuyama M, Matsuki M, Takai S, Yamanishi K, Miyazaki M, Matsubara H, Yabe-Nishimura C. Nox1 is involved in angiotensin II-mediated hypertension–a study in Nox1-deficient mice. Circulation 112: 2677–2685, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Matsuo S, Saiki Y, Adachi O, Kawamoto S, Fukushige S, Horii A, Saiki Y. Single-dose rosuvastatin ameliorates lung ischemia-reperfusion injury via upregulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase and inhibition of macrophage infiltration in rats with pulmonary hypertension. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 149: 902–902, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Montezano AC, Nguyen Dinh Cat A, Rios FJ, Touyz RM. Angiotensin II and vascular injury. Curr Hypertens Rep 16: 431–442, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Moreau P, Drolet G, Yamaguchi N, de Champlain J. Alteration of prejunctional alpha 2-adrenergic autoinhibition in DOCA-salt hypertension. Am J Hypertens 8: 287–293, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.O'Donaughy TL, Brooks VL. Deoxycorticosterone acetate-salt rats: hypertension and sympathoexcitation driven by increased NaCl levels. Hypertension 47: 680–685, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Park J, Galligan JJ, Fink GD, Swain GM. Alteration in sympathetic neuroeffector transmission to mesenteric arteries but not veins in DOCA-salt hypertension. Auton Neurosci 152: 11–20, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Park J, Galligan JJ, Fink GD, Swain GM. Differences in sympathetic neuroeffector transmission to rat mesenteric arteries and veins as probed by in vitro continuous amperometry and video imaging. J Physiol 584: 819–834, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Paterniti I, Galuppo M, Mazzon E, Impellizzeri D, Esposito E, Bramanti P, Cuzzocrea S, 2010. Protective effects of apocynin, an inhibitor of NADPH oxidase activity, in splanchnic artery occlusion and reperfusion. J Leukoc Biol 88: 993–1003, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Polfliet MM, Fabriek BO, Daniëls WP, Dijkstra CD, van den Berg TK. The rat macrophage scavenger receptor CD163: expression, regulation and role in inflammatory mediator production. Immunobiology 211: 419–425, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pons H, Ferrebuz A, Quiroz Y, Romero-Vasquez F, Parra G, Johnson RJ, Rodriguez-Iturbe B. Immune reactivity to heat shock protein 70 expressed in the kidney is cause of salt sensitive hypertension. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 304: F289–F299, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rehman A, Leibowitz A, Yamamoto N, Rautureau Y, Paradis P, Schiffrin EL. Angiotensin type 2 receptor agonist compound 21 reduces vascular injury and myocardial fibrosis in stroke-prone spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertension 59: 291–299, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ruiz-Velasco V, Ikeda SR. Multiple G-protein β-γ combinations produce voltage-dependent inhibition of N-type calcium channels in rat superior cervical ganglion neurons. J Neurosci 20: 2183–2191, 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sangsiri S, Dong H, Swain GM, Galligan JJ, Xu H. Impaired function of prejunctional adenosine A1 receptors expressed by perivascular sympathetic nerves in DOCA-salt hypertensive rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 345: 32–40, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schenk J, McNeil JH. The pathogenesis of DOCA-salt hypertension. J Pharmacol Toxicol Meth 27: 161–170, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schillaci G, Pirro M, Gemelli F, Pasqualini L, Vaudo G, Marchesi S, Siepi D, Bagaglia F, Mannarino E. Increased C-reactive protein concentrations in never-treated hypertension: the role of systolic and pulse pressures. J Hypertens 21: 1841–1846, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Stewart M, Thiel M, Hong N. Leukocyte integrins. Curr Opin Cell Biol 7: 690–696, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Touyz RM. Reactive oxygen species, vascular oxidative stress, and redox signaling in hypertension what is the clinical significance? Hypertension 44: 248–252, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tsuda K, Tsuda S, Nishio I, Masuyama Y. Inhibition of norepinephrine release by presynaptic alpha-2-adrenoceptors in mesenteric vasculature preparations from chronic DOCA-salt hypertensive rats. Japan Heart J 30: 231–239, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Van Gorp H, Delputte PL, Nauwynck HJ. Scavenger receptor CD163, a Jack of all trades and potential target for cell directed therapy. Mol Immunol 47: 1650–1660, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.van Rooijen N, Sanders A. Liposome mediated depletion of macrophages: mechanism of action, preparation of liposomes and applications. J Immunol Methods 174: 83–93, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.van Rooijen N, Sanders A, Van den Berg T. Apoptosis of macrophages induced by liposome-mediated intracellular delivery of drugs. J Immunol Methods 193: 93–99, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wenzel P, Knorr M, Kossmann S, Stratmann J, Hausding M, Schuhmacher S, Karbach SH, Schwenk M, Yogev N, Schulz E, et al. . Lysozyme M-positive monocytes mediate angiotensin II-induced arterial hypertension and vascular dysfunction. Circulation 124: 1370–1381, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Westfall TC, Badino L, Naes L, Meldrum MJ. Alterations in the field stimulation-induced release of endogenous norepinephrine from the coccygeal artery of spontaneously hypertensive and Wistar-Kyoto rats. Eur J Pharmacol 135: 433–437, 1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Westfall TC, Meldrum MJ, Badino L, Earnhardt JT. Noradrenergic transmission in the isolated portal vein of the spontaneously hypertensive rat. Hypertension 6: 267–274, 1984. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Xu H, Fink GD, Galligan JJ. Tempol lowers blood pressure and sympathetic nerve activity but not vascular O2− in DOCA-salt rats. Hypertension 43: 329–334, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yemane H, Busauskas M, Kurris S, Knuepfer M. Neurohumoral mechanisms in deoxycorticonsterone acetate (DOCA)-salt hypertension in rats. Exp Physiol 95: 51–55, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zalba G, San José G, Moreno MU, Fortuño MA, Fortuño A, Beaumont FJ, Díez J. Oxidative stress in arterial hypertension: role of NAD(P)H oxidase. Hypertension 38: 1395–1399, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]