Abstract

The reduced uterine perfusion pressure (RUPP) rat model of preeclampsia exhibits much of the pathology characterizing this disease, such as hypertension, inflammation, suppressed regulatory T cells (TRegs), reactive oxygen species (ROS), and autoantibodies to the ANG II type I receptor (AT1-AA) during pregnancy. The objective of this study was to determine whether supplementation of normal pregnant (NP) TRegs into RUPP rats would attenuate the pathophysiology associated with preeclampsia during pregnancy. CD4+/CD25+ T cells were isolated from spleens of NP and RUPP rats, cultured, and injected into gestation day (GD) 12 normal pregnant rats that underwent the RUPP procedure on GD 14. On GD 1, mean arterial pressure (MAP) was recorded, and blood and tissues were collected for analysis. One-way ANOVA was used for statistical analysis. MAP increased from 99 ± 2 mmHg in NP (n = 12) to 127 ± 2 mmHg in RUPP (n = 21) but decreased to 118 ± 2 mmHg in RUPP+NP TRegs (n = 17). Circulating IL-6 and IL-10 were not significantly changed, while circulating TNF-α and IL-17 were significantly decreased after supplementation of TRegs. Placental and renal ROS were 339 ± 58.7 and 603 ± 88.1 RLU·min−1·mg−1 in RUPP and significantly decreased to 178 ± 27.8 and 171 ± 55.6 RLU·min−1·mg−1, respectively, in RUPP+NP TRegs; AT1-AA was 17.81 ± 1.1 beats per minute (bpm) in RUPP but was attenuated to 0.50 ± 0.3 bpm with NP TRegs. This study demonstrates that NP TRegs can significantly improve inflammatory mediators, such as IL-17, TNF-α, and AT1-AA, which have been shown to increase blood pressure during pregnancy.

Keywords: hypertension, pregnancy, inflammation, oxidative stress, regulatory T cells

preeclampsia is a pregnancy-associated disorder that affects 5–8% of pregnancies and is a major cause of maternal, fetal, and neonatal morbidity and mortality (9, 29, 37). Hallmark characteristics of preeclampsia are new-onset hypertension after 20 wk gestation, proteinuria, chronic immune activation, fetal growth restriction, and maternal endothelial dysfunction. The pathophysiological mechanisms that lead to the development of preeclampsia are poorly understood. It is thought that poor invasion of trophoblasts leads to insufficient spiral artery remodeling, resulting in placental ischemia (4, 10, 31). The hypoxic environment that results from this placental ischemia is suggested to be an important factor in the development of oxidative stress and a shift in the balance of antiangiogenic and proangiogenic factors, which plays a role in endothelial dysfunction of the placenta and maternal vasculature (10). Previous studies from our laboratory in the reduced uterine perfusion pressure (RUPP) rat model of preeclampsia demonstrate that the total population of CD4-positive (CD4+) T cells isolated from RUPP spleens and transferred to NP rats causes similar pathology to that seen in RUPP rats (46), demonstrating a role for this population in mediating pathophysiology in response to placental ischemia. Recent data from both clinical and animal model studies demonstrate an imbalance in the subpopulations of CD4+ T cells and a role for these cells as mediators of inflammation and hypertension during pregnancy (5, 36, 41, 43, 46, 47). Specifically, it has been proposed that the imbalance between two CD4+ T-cell subtypes, regulatory T cells (TRegs), and T-helper 17 cells (TH17s), is involved in the pathophysiology of preeclampsia (38, 41, 43).

Regulatory T cells play a major role in the development and maintenance of immune tolerance (8) and are classically identified by surface expression of CD4 and CD25, as well as the transcription factor forkhead box protein 3 (FoxP3) (8, 35). Regulatory T cells regulate the immune system by suppressing autoreactive T cells, dampening inflammation, and inducing tolerance in normal pregnancy. Maternal immune tolerance is dependent on TRegs and uterine natural killer (NK) cells, recognizing and accepting the fetal antigens and facilitating placental growth (44, 45). Studies suggest that failure of the maternal immune tolerance mechanisms precedes the development of placental ischemia and oxidative stress, both of which are known to be involved in the pathophysiology of preeclampsia (18). Clinical studies have shown that there is a decrease in the number of TRegs in preeclamptic women compared with women with normal pregnancies (5, 38, 42, 43). Our data echo these findings in that the TReg population is a low percentage among total CD4+ T cells isolated from RUPP rats. There is approximately a 47% decrease in TRegs in their peripheral circulation of RUPP rats compared with normal pregnant rats (46).

We hypothesize that this decreased population of TRegs leads to the failure of maternal immune tolerance and the induction of placental ischemia, oxidative stress, AT1-AA, inflammatory cytokines, and other pathophysiologies associated with preeclampsia during pregnancy. Therefore, the objective of the study was to determine whether supplementation of TRegs from normal pregnant (NP) rats into RUPP rats before placental insult would attenuate or lessen the pathology associated with placental ischemia. This current study could shed light as to whether or not TReg numbers present in response to placental ischemia plays a role in allowing factors to be stimulated that cause hypertension and are associated with preeclampsia.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Pregnant Sprague-Dawley rats purchased from Harlan Sprague Dawley (Indianapolis, IN) were used in this study. Animals were housed in a temperature-controlled room (23°C) with a 12:12-h light-dark cycle. All experimental procedures executed in this study were in accordance with the National Institutes of Health guidelines for use and care of animals. All protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Mississippi Medical Center.

Regulatory T-cell isolation, culture, and differentiation.

At the time of harvest (gestation day 19), spleens were collected from NP rats, and lymphocytes were isolated from spleens by centrifugation on a cushion of Ficoll-Hypaque (Lymphoprep, Accurate Chemical & Scientific, Westbury, NY), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Anti-CD4 and anti-CD25 antibodies (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) were biotinylated using the DSB-X biotin protein labeling kit (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Isolated lymphocytes were incubated with biotinylated anti-CD4 antibody. The CD4+ population was isolated using FlowComp Dynabeads (Invitrogen, Oslo, Norway), according to the manufacturer's protocol. The CD4+ population of lymphocytes was then incubated with biotinylated anti-CD25 antibody, and the CD4+/CD25+ population was again isolated using FlowComp Dynabeads. Biotinylated antibodies and FlowComp Dynabeads were separated from cells, according to manufacturer's protocol, prior to culture and expansion. The CD4+/CD25+ splenocytes were incubated on anti-CD3 and anti-CD-28 beads in T-helper media (RPMI, 10% FBS, 5% PenStrep, 1% HEPES) in 96-well plates at 103 cells/well on day 0. On day 2, cells were removed from magnetic beads and cultured in T-helper specific media (RPMI, 10% FBS, 5% Pen-Strep, 1% HEPES, 20 ng/ml IL-2, 5 ng/ml TGF-β1, 10 ng/ml TNF-α) for 5–6 days, following standard protocols for expansion of the existing TReg population in culture (14–17). Differentiation of isolated cells into TReg cells was verified via flow cytometry.

Determination of circulating cultured TReg lymphocyte population.

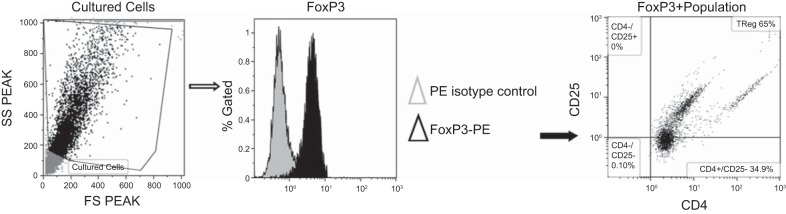

Circulating TReg lymphocyte population was determined from peripheral blood leukocytes (PBL) collected at day 19 of gestation from NP, RUPP, and RUPP+NP TReg animals by flow cytometry. At the time of harvest, plasma was collected, and peripheral blood mononuclear cells were isolated from plasma by centrifugation on a cushion of Ficoll-Hypaque (Lymphoprep, Accurate Chemical & Scientific, Westbury, NY), according to the instructions of the manufacturer. The cultured CD4+ TReg cell population was analyzed for purity of CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ cells. For flow cytometric analysis, 1 × 106 cells were incubated for 30 min at 4°C with antibodies against rat CD4 and rat CD25 (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). After washing, cells were labeled with secondary fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC; Southern Biotech, Birmingham, AL) and phycoerythrin with cyanin-5 (PE-Cy5; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) antibody for 30 min at 4°C. Cells were washed, permeabilized, and stained with anti-mouse/rat FoxP3 conjugated to phycoerythrin (PE; eBioscience, San Diego, CA) for 30 min at 4°C. As a negative control for each individual rat, cells were treated exactly as described above, except they were incubated with isotype control antibodies conjugated to FITC, PE-Cy5, or PE secondary antibodies alone. Subsequently, cells were washed, fixed, and resuspended in 500 μl of Rosswell Park Memorial Institute medium (RPMI) and analyzed for single, double, and triple staining on a Gallios flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA) (Fig. 1). The lymphocyte population of cells was gated, and cells were examined for Foxp3-positive staining. The FoxP3-positive-stained cells were then examined for CD4- and CD25-positive staining. The percent of positive stained cells above the negative control was collected for three separate cultures or individual rats, and the mean values for each experimental group were calculated.

Fig. 1.

Flow cytometry analysis of TReg population. To examine cultured TReg cells, a subset of cells from culture was stained for the external markers CD4 and CD25. Cells were permeabilized and fixed before staining for the intracellular transcription factor, FoxP3. Cells were gated in the forward and side scatterplot. The percentage of FoxP3+ cells were measured within the gate. TRegs are CD4+ and CD25+ cells within the FoxP3+ gate. Representative flow cytometry plot showing TRegs differentiated in culture.

Adoptive transfer of NP and RUPP TReg cells.

For consistency with previous adoptive transfer studies performed in our laboratory, 500 μl of cultured TReg cells, in sterile saline, were injected, intraperitoneally, into normal pregnant (NP) rats at 2 × 106 cells/ml on day 12 of gestation (GD12). In addition, GD12 was chosen to examine the effect of TReg supplementation prior to placental insult on pathology in response to placental ischemia. On GD14, under isoflurane anesthesia, recipients of the NP TReg cells underwent the RUPP procedure, as described below. The groups of rats examined in this study were NP (n = 12), RUPP (n = 21), and RUPP recipients of NP TReg cells (RUPP+NPTRegs, n = 17).

Reduction of uterine perfusion pressure.

On GD14, under isoflurane anesthesia, a subset of NP rats and all NP recipients of NPTRegs underwent RUPP with the application of a constrictive silver clip (0.203 mm) to the aorta superior to the iliac bifurcation, while ovarian collateral circulation to the uterus was reduced with restrictive clips (0.100 mm) to the bilateral uterine arcades at the ovarian end (11, 21, 46). Rats were excluded from the study when the clipping procedure resulted in total reabsorption of all fetuses.

Measurement of mean arterial pressure in chronically instrumented conscious rats.

Under isoflurane anesthesia, on day 18 of gestation, carotid arterial catheters were inserted for blood pressure measurements. The catheters inserted were V3 tubing (SCI), which is tunneled to the back of the neck and exteriorized. On day 19 of gestation, arterial blood pressure was analyzed after placing the rats in individual restraining cages. Arterial pressure was monitored with a pressure transducer (Cobe III tranducer CDX Sema) and recorded continuously for 30 min after a 30-min stabilization period. Subsequently, blood and urine samples were collected; kidneys, placentas, and spleens were harvested; and litter size and pup weights were recorded under anesthesia.

Determination of cytokine production.

Plasma and serum collected from all pregnant rats were measured for IL-4, IL-6, IL-10, IL-17, transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), IFN-γ, and TNF-α concentrations using commercial ELISA kits available from R&D Systems (Quantikine-IL4, IL-6, Il-10, IL-17, TGF-β, IFN-γ) and MyBioSource (IL-35), according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Determination of placental endothelin-1 levels in pregnant rats.

Placentas were weighed and quickly frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C. Total RNA was extracted using the RNeasy Protect mini-kit supplied by Qiagen, as outlined in the instructions provided by the manufacturer. Real-time PCR was used, as previously described, to determine tissue preproendothelin-1 levels (23, 26). Briefly, cDNA was synthesized from 1 μg of RNA with Bio-Rad Iscript cDNA reverse transcriptase, and real-time PCR was performed using the Bio-Rad SYBR Green Supermix and iCycler. The following primer sequences, provided by Life technologies, were used for preproendothelin (PPET), as previously described: forward 1, ctaggtctaagcgatccttg and reverse 1, tctttgtctgcttggc (21, 24, 25). Levels of mRNA were calculated using the mathematical formula for 2−ΔΔCt (2avg.Ct gene of interest − avg Ct β-actin) recommended by Applied Biosystems (Applied Biosystems, User Bulletin, No. 2, 1997).

Determination of placental and renal reactive oxygen species.

Superoxide production in the placenta and renal cortex was measured by using the lucigenin technique, as we have previously described (21, 34). Rat placentas and cortices from NP, RUPP, and RUPP+NPTRegs rats were snap frozen in liquid nitrogen directly after collection and stored at −80°C until further processing. Placentas and cortices were removed and homogenized in RIPA buffer (PBS, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, and a protease inhibitor cocktail; Santa Cruz, Santa Cruz, CA), as described previously (21, 34). The samples were centrifuged at 16,000 g for 30 min, the supernatant was aspirated, and the remaining cellular debris was discarded. The supernatant was incubated with lucigenin at a final concentration of 5 μmol/l. The samples were allowed to equilibrate for 15 min in the dark, and luminescence was measured every second for 10 s with a luminometer (Berthold, Oak Ridge, TN). Luminescence was recorded as relative light units (RLU) per minute. An assay blank with no homogenate but containing lucigenin was subtracted from the reading before transformation of the data. Each sample was repeated five times, and the average was used for data transformation. The protein concentration was measured using a protein assay with BSA standards (Pierce, Rockford, IL). The data are expressed as RLU per minute per milligram of protein.

Determination of circulating AT1-AA.

On day 19 of gestation, blood was collected and immunoglobulin was isolated from 200 μl of serum by protein G Sepharose on a bioline protein purification system (Knauer, Germany). This IgG fraction was used in a bioassay. The AT1-AA activity was measured using spontaneously beating neonatal rat cardiomyocytes and characterized and antagonized specifically using AT1 receptor antagonists. The results express the difference between the basal beating rate of the cardiomyocytes and the beating rate measured after the addition of the AT1-AA (increase in number of beats/min or Δ beats/min) (6, 7, 19, 21, 32, 33). AT1-AAs were assessed in NP, RUPP controls, and RUPP+NPTRegs rats.

Statistical analysis.

All of the data are expressed as means ± SE. Comparisons of control with experimental groups were analyzed by ANOVA with Tukey's multiple-comparison test as post hoc analysis. A value of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Adoptive transfer of NP TReg cells significantly decreased blood pressure in RUPP rats.

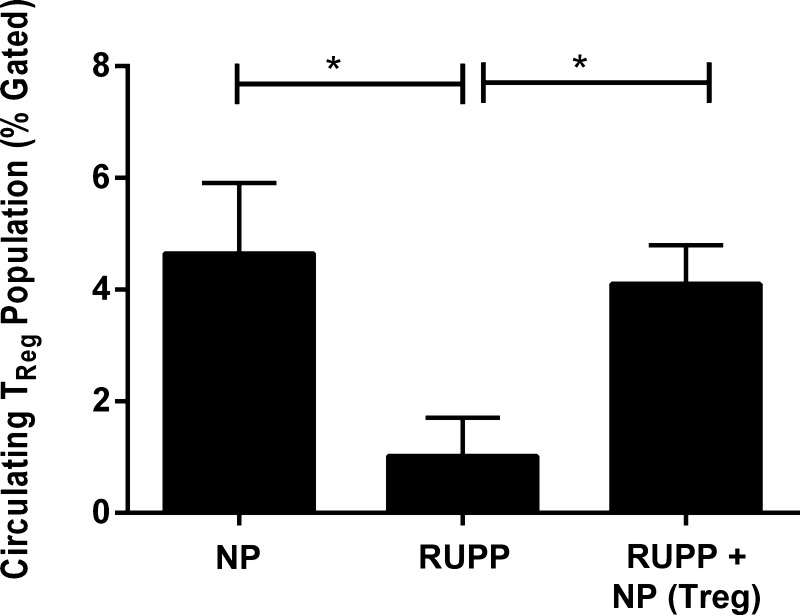

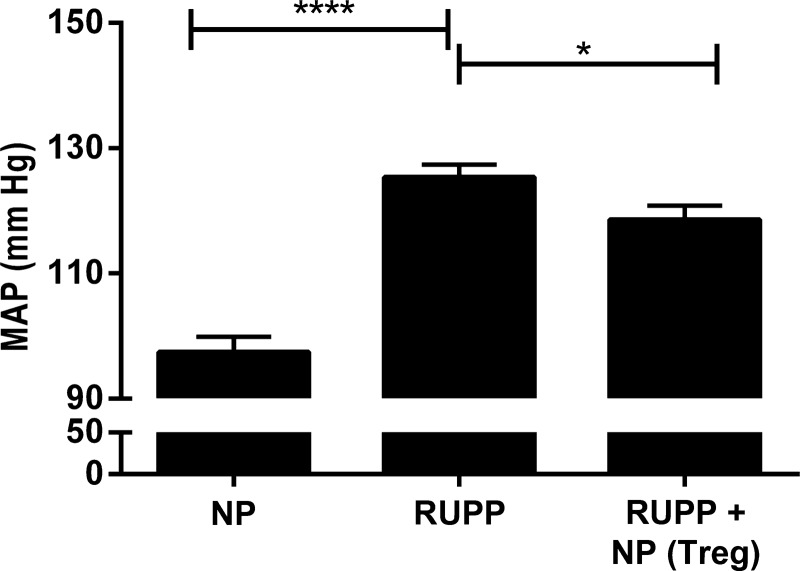

CD4+/CD25+ T cells were isolated from NP spleens and cultured, as described above; flow cytometry was performed to verify differentiation of cells into TReg population as shown in Fig. 1. Ninety-nine percent of the stained cells were double-positive for CD4+ and FoxP3+, and 65% of the stained cells were triple-positive for CD4+, FoxP3+, and CD25+ (Fig. 1). Adoptive transfer of NP TRegs significantly increased the circulating population of TRegs in the RUPP rat to levels similar to what is observed in NP animals [NP (n = 5) 4.65 ± 1.2% gated, RUPP (n = 6) 1.02 ± 0.68% gated (P < 0.05 vs. NP), RUPP+NP TRegs (n = 5) increased to 4.1 ± 0.69% gated (P < 0.05 vs. RUPP)] (Fig. 2). Mean arterial pressure (MAP) was measured on day 19 of gestation in NP, RUPP, and RUPP+NPTRegs rats (Fig. 3). The MAP increased significantly from 99 ± 2 mmHg in NP rats (n = 12) to 127 ± 2 mmHg in RUPP rats (n = 21, P < 0.0001). Supplementation of NP TRegs prior to placental insult into RUPP rats caused a significant decrease in blood pressure to 118 ± 2 mmHg in RUPP+NPTRegs (n = 17, P < 0.05 vs. RUPP). These statistics indicate the increase in blood pressure from NP compared with RUPPs was much greater than NP compared with RUPP+NPTRegs. In addition, RUPP+NPTRegs had significantly lower blood pressure than control RUPPs, although blood pressure in RUPP+NP TRegs remained higher than NP (P < 0.0001), thus, indicating that other mechanisms also contribute to the increased blood pressure in response to placental ischemia.

Fig. 2.

Circulating TRegs are significantly increased after adoptive transfer into reduced uterine perfusion pressure (RUPP) rats. The population of TRegs was measured in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from NP, RUPP, and RUPP+NP TReg rats. Adoptive transfer of NP TRegs significantly increased circulating TRegs in RUPP+NPTRegs rats similar to that observed in NP rats. Tukey's test was performed as post hoc analysis to generate P values. (*P < 0.05).

Fig. 3.

Normal pregnant (NP) TRegs significantly decrease blood pressure in RUPP rats. Mean arterial pressure (MAP) was measured on day 19 in NP (n = 12), RUPP (n = 21), RUPP+ NPTRegs rat (n = 17). RUPP+NPTRegs, RUPP recipients of TRegs from NP rats. Tukey's test was performed as post hoc analysis to generate P values. (*P < 0.05, ****P < 0.0001).

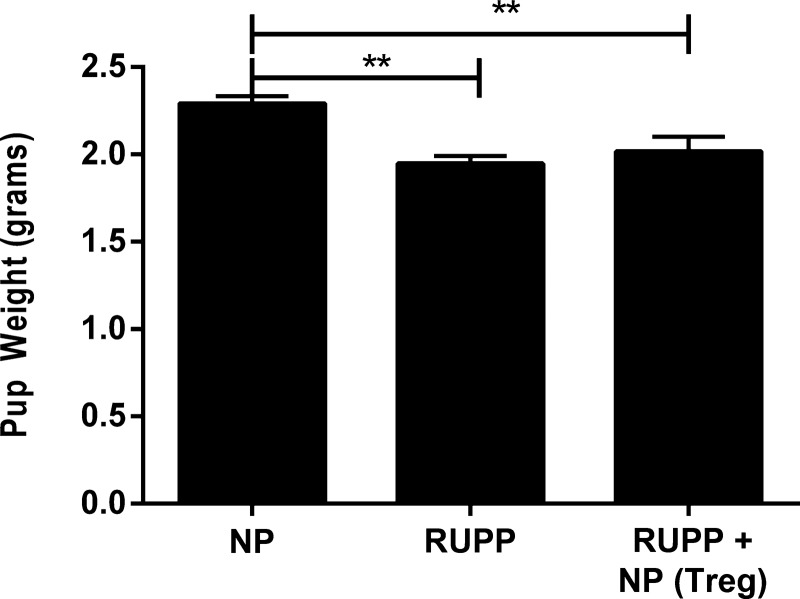

Adoptive transfer of NP TReg cells does not significantly improve intrauterine growth restriction in RUPP rats.

In Fig. 4, pup weight of litters from RUPP rats (1.98 ± 0.05 g, n = 21) was significantly lower than pup weight from NP rats (2.3 ± 0.04 g, n = 14; P < 0.01). Adoptive transfer of NP TRegs prior to placental insult into RUPP rats did not significantly increase pup weight (2.02 ± 0.08 g, n = 17; P = 0.15 compared with RUPP; P < 0.05 compared with NP). Placental weight and resorption rate were also unchanged. These statistics indicate that the effect of RUPP to decrease pup weight and cause fetal morbidity is not inhibited with the increased number of NP TRegs used in this study.

Fig. 4.

NP TRegs do not improve pup weight in RUPP rats. At the time of harvest, the average weight of pups was calculated for all experimental groups. A: NP (n = 12), RUPP (n = 21), RUPP+NPTRegs (n = 17) rats. Tukey's test was performed as post hoc analysis to generate P values. (**P < 0.01).

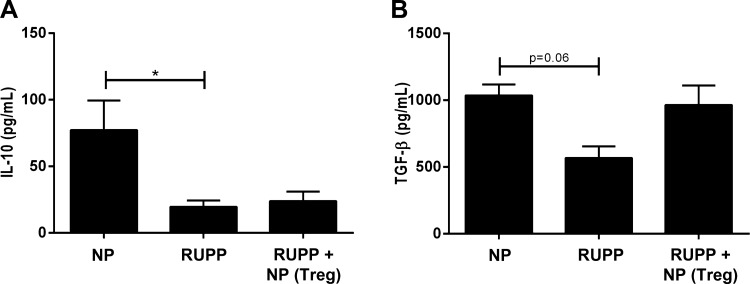

NP TReg cell supplementation normalizes TGF-β in RUPP rats.

Circulating levels of the anti-inflammatory cytokines IL-10, IL-35, IL-4, and TGF-β were measured in plasma (IL-4, IL-10) and serum (IL-35, TGFβ1) from all experimental groups. IL-10 was significantly decreased in RUPP rats compared with NP rats (RUPP 19.6 ± 4.8 pg/ml, n = 11 vs. NP 77.3 ± 22.2 pg/ml, n = 11, Fig. 5A). Adoptive transfer of NP TRegs into RUPP rats (n = 8) did not alter circulating IL-10 (Fig. 5A). Circulating IL-35 and IL-4 were not different among the three groups. Serum levels of IL-35 were 2.4 ± 1.1 pg/ml in NP, 2.7 ± 2.6 pg/ml in RUPP, and 15.1 ± 11.1 pg/ml in RUPP+ NPTRegs (n = 5/group). Plasma levels of IL-4 were 22.4 ± 3.7 pg/ml in NP, 18.7 ± 9.6 pg/ml in RUPP, and 42.3 ± 8.2 pg/ml in RUPP+ NPTRegs (n = 5/group). Additionally, as we have previously published (12), serum TGF-β trended toward a decrease in response to placental ischemia (NP 1,036 ± 82 pg/ml vs. RUPP 567 ± 88 pg/ml, n = 4/group, P = 0.06) and was normalized after adoptive transfer of NP TRegs into RUPP rats (965 ± 145 pg/ml, n = 6) (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

NP TReg cells normalize anti-inflammatory cytokine levels in RUPP rats. Circulating levels of the anti-inflammatory cytokines, IL-10, and TGF-β were measured in all groups. Tukey's test was performed as post hoc analysis to generate P values. (*P < 0.05).

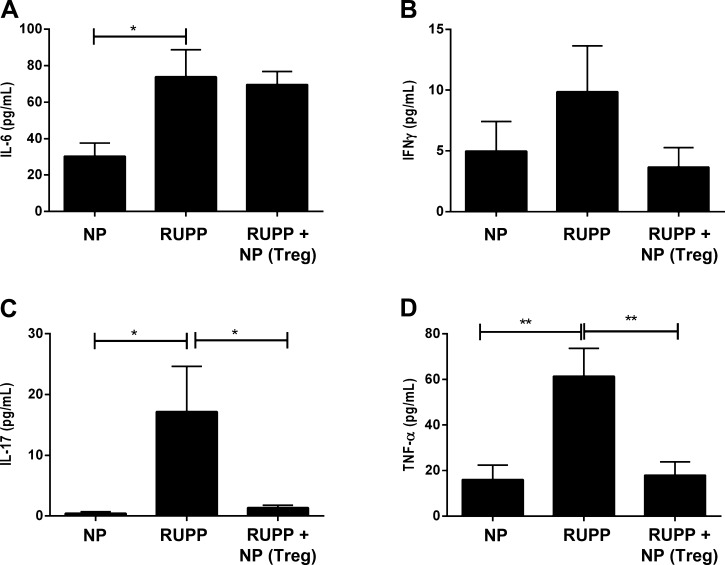

NP TReg cell supplementation attenuates increased IL-17 and TNF-α in RUPP rats.

Circulating levels of the proinflammatory cytokines IL-6, IFN-γ, IL-17, and TNF-α were measured in plasma from all experimental groups. Plasma IL-6 was significantly higher in RUPPs (NP: 30 ± 7 pg/ml, n = 10 vs. RUPP: 74 ± 15 pg/ml, n = 13, P < 0.05), and adoptive transfer of NP TRegs did not alter circulating IL-6 in RUPP recipients (n = 16, Fig. 6A). Plasma IFN-γ was nearly doubled in response to placental ischemia (NP 5.0 ± 2.4 pg/ml vs. RUPP 9.9 ± 3.8 pg/ml, n = 6/group) and was normalized with adoptive transfer of NP TRegs into RUPP rats (3.7 ± 1.6 pg/ml, n = 6) (Fig. 6B). Importantly circulating IL-17 and TNF-α levels significantly increased in RUPP rats compared with NP rats, and supplementation of NP TRegs into RUPP attenuated this increase: IL-17: NP (n = 7) 0.44 ± 0.24 pg/ml; RUPP (n = 7) 17.19 ± 7.42 pg/ml, P < 0.05 vs. NP, RUPP+NPTRegs (n = 8) 1.37 ± 0.43 pg/ml, P < 0.05 vs. RUPP (Fig. 6C); TNF-α: NP (n = 11) 16.0 ± 6.4 pg/ml; RUPP (n = 14) 61.4 ± 12.2 pg/ml, P < 0.01 vs. NP, and RUPP+ NPTRegs (n = 17) 18 ± 6, n = 17, P < 0.01 vs. RUPP (Fig. 6D).

Fig. 6.

NP TReg cells blunt the inflammatory response in RUPP rats. Circulating levels of the proinflammatory cytokines, IL-6, IFN-γ, IL-17, and TNF-α were measured in all animal groups. Tukey's test was performed as post hoc analysis to generate P values. (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01).

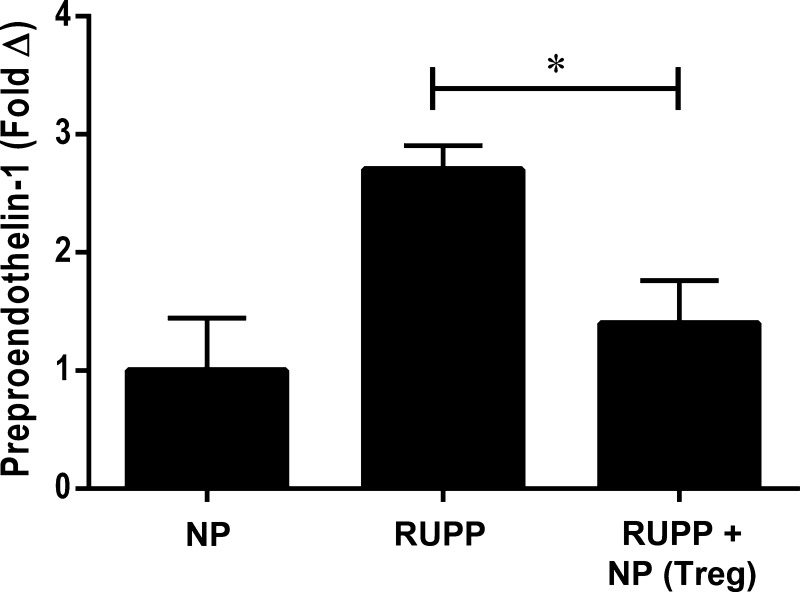

NP TRegs decrease placental preproendothelin mRNA levels.

Endothelin-1 is a potent vasoconstrictor that is increased in preeclampsia, and we have shown an important role for increased ET-1 to increase blood pressure in the RUPP rat (40). Real-time PCR was used to measure preproendothelin in the placenta of rats from each group. In Fig. 7, preproendothelin decreased in RUPP rats after supplementation with NP TRegs. Preproendothelin (PPET-1) mRNA was twofold higher in the placentas of RUPP rats (n = 6) compared with NP rats (n = 6) and was blunted to 0.26-fold with NP TRegs (n = 6) supplementation.

Fig. 7.

NP TRegs decrease placental preproendothelin mRNA levels. mRNA of preproendothelin was measured in the placental of NP (n = 6), RUPP (n = 6), and RUPP+ TRegs (n = 6) rats using quantitative RT-PCR. Tukey's test was performed as post hoc analysis to generate P values. (*P < 0.05).

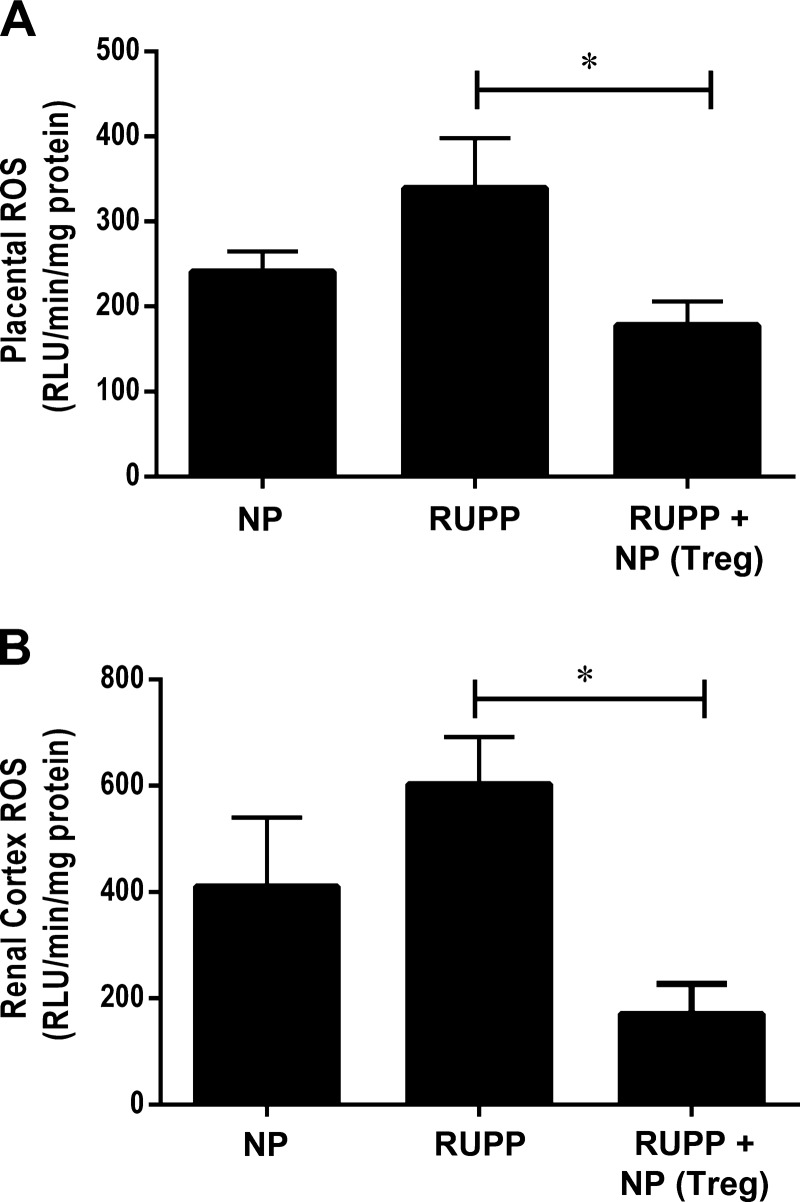

Adoptive transfer of NP TReg cells normalizes reactive oxygen species production in RUPP rats.

Placental oxidative stress has been shown to be increased in preeclamptic women, and placental and renal oxidative stress is observed in preclinical models preeclampsia, and it is implicated in contributing to the development of vascular dysfunction, proteinuria, and hypertension during pregnancy (9, 13, 27, 28). Importantly reactive oxygen species (ROS) is a byproduct of inflammation and is elevated in response to RUPP CD4+ T cells and IL-17- and AT1-AA-induced hypertension during pregnancy. Therefore, we wanted to determine whether supplementation with NP TRegs into RUPP rats prior to placental ischemia could lower inflammation and ROS. Fig. 8A shows that placental ROS was 240.9 ± 24.1 RLU·min−1·mg−1 in NP rats (n = 8), and 339.3 ± 58.7 RLU·min−1·mg−1 in RUPP (n = 7) rats. Adoptive transfer of NP TRegs into RUPP (n = 8) rats significantly lowered oxidative stress in the RUPP recipient placentas (178.1 ± 27.8 RLU·min−1·mg−1, P < 0.05 compared with RUPP), Fig. 8B shows that renal ROS was 410.5 ± 129.9 RLU·min−1·mg−1 in NP rats (n = 8) compared with 603.3 ± 88.1 RLU·min−1·mg RUPP−1 rats (n = 7). NP TReg supplementation into RUPP rats (n = 8) significantly reduced renal oxidative stress to below that observed in NP controls (171.3 ± 55.6 RLU·min−1·mg−1; P = 0.001 vs. RUPP rats).

Fig. 8.

NP TRegs blunt placental and renal oxidative stress. Oxidative stress is a hallmark of preeclampsia. Oxidative stress was measured in the placentas (A) and renal cortices (B) of NP (n = 8), RUPP (n = 7), and RUPP+NPTRegs (n = 8) rats using chemiluminescence methods. Tukey's test was performed as post hoc analysis to generate P values. (*P < 0.05).

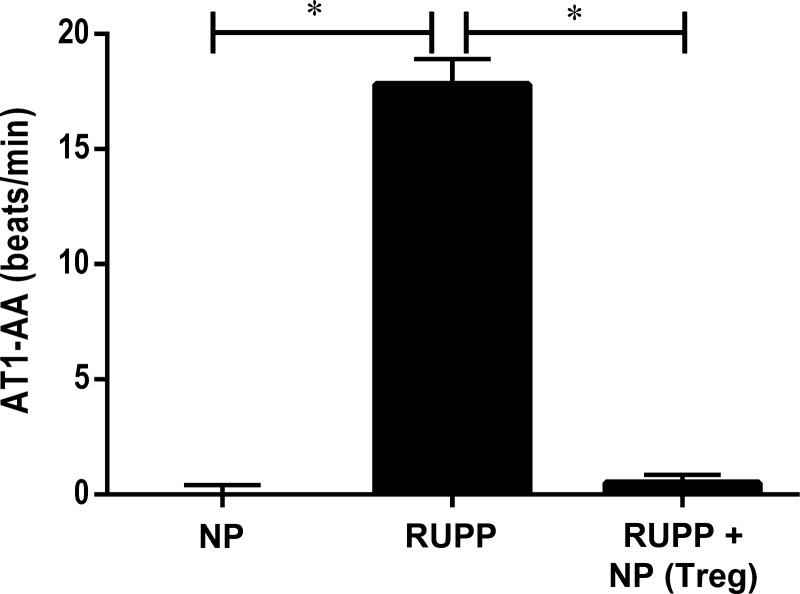

Adoptive transfer of NP TReg cells attenuates AT1-AA in RUPP rats.

AT1-AA is an important mediator of hypertension during preeclampsia, and we have shown it to be increased in RUPP rats. AT1-AAs in NP rats (n = 8) were 0.08 ± 0.25 bpm. AT1-AAs increased significantly to 17.81 ± 1.1 bpm in RUPP rats (n = 8) (Fig. 9, P < 0.0001) but were attenuated with supplementation of NP TRegs into RUPP rats (n = 8) (0.50 ± 0.3 bpm, P < 0.0001 Fig. 7).

Fig. 9.

NP TRegs decrease production of AT1-AA. AT1-AA levels were measured via chronotropic events in cardiomyocytes in culture (beats/min). Tukey test was performed as post hoc analysis to generate P values. (*P < 0.0001).

DISCUSSION

The objective of this study was to determine a role for NP TRegs to counteract the pathology observed in response to placental ischemia in the RUPP rat. Data from this study demonstrate that adoptive transfer of NP TRegs into RUPP rats prior to placental insult results in lower blood pressure, blunts inflammation and ET-1 expression, normalizes tissue oxidative stress, and attenuates AT1-AA production in response to placental ischemia. This suggests that the number of TRegs is important to control inflammation and vasoactive factors contributing to hypertension during pregnancy, such as oxidative stress, AT1-AA, and ET-1. Although no improvement in fetal morbidity was observed with adoptive transfer of NP TRegs into RUPP rats, improving pathophysiology in the mother may indirectly benefit the fetus by increasing time to delivery, thereby, giving the fetus more time to develop and mature.

Immunosuppressive factors known to be secreted by TRegs include IL-10, TGFβ, and more recently, IL-35. All of these soluble factors have direct suppressive effects on effector T cells (3). IL-35 directly inhibits effector T-cell expansion and could affect TH17 cells and, thus, IL-17 (3). Although IL-35 was not significantly increased with TReg supplementation in our model, it was elevated fivefold in the majority of our samples, which could have resulted in the significantly lower IL-17 in RUPP + NP TRegs. Future studies on the role of IL-35 will determine whether this cytokine is a mechanism that could be used by TRegs to inhibit pathology in response to placental ischemia.

TGF-β and IL-10 are critical for inhibition of spontaneous and induced development of autoimmune diseases, respectively. TGF-β is thought to be important for peripheral tolerance and the induction of inducible TRegs. In this study, circulating TGF-β was normalized in RUPP rats after TReg supplementation. IL-10 and IL-4 also have important immunoregulatory and anti-inflammatory function. Surprisingly, increases in the circulating levels of IL-10 were not detected after adoptive transfer of NP TRegs into placental ischemic RUPP rats. We have recently shown that IL-10 supplementation significantly lowered blood pressure, TNF-α, and AT1-AA, while increasing Tregs in RUPP rats (12). In that study, elevations in IL-10 were not detected; however, it could be that in each study, IL-10 is bound to its receptors and mediating anti-inflammatory function, such as repressing TNF-α, AT1-AA, and stimulating TRegs. In addition, IL-4, although not statistically significant, was elevated twofold with supplementation of RUPP rats with NP TRegs. Not many studies have been performed with IL-4 during preeclampsia; however, we know that it is important in programming of TH2 cells, which are known to be decreased in preeclampsia. Although not measured in this study, it could be that the twofold increase in IL-4 may have an effect on further influencing the T-cell profile and will be the subject of future investigations from our laboratory.

In this study, we demonstrate that adoptive transfer of TRegs from NP rats into RUPP rats reduced TNF-α stimulated in response to placental ischemia. We have previously shown an important role for TNF-α to stimulate AT1-AA, oxidative stress, and ET-1 as mechanisms of hypertension when it is infused into NP rats (1, 22, 24). Conversely, TNF-α has no effect to increase blood pressure in virgin rats. Furthermore, administration of the soluble inhibitor of TNF-α to RUPP rats significantly lowered blood pressure, ET-1, and endothelial cell activation (20). Likewise, in the current study, with supplementation of TReg numbers in the RUPP rat, ET-1, placental and renal oxidative stress, and AT1-AA were all attenuated, possibly by lowering TNF-α. These data indicate not only the importance of inhibition of these hypertensive mechanisms in response to placental ischemia but how influential TReg numbers are in controlling TNF-α and important vasoactive factors that are stimulated in response to placental ischemia. Therefore, these data support a role for a loss of TReg numbers in the pathophysiology of preeclampsia, potentially by controlling factors stimulated by TNF-α and/or IL-17. The supplementation of TRegs prior to the time of placental ischemia (GD 12 vs. GD 14) suggests the importance of TRegs in immune regulation in maintaining lower levels of oxidative stress, AT1-AA, and PPET-1, factors, which contribute to higher blood pressure, in the face of placental ischemia.

The importance of TRegs in maintenance of early pregnancy has previously been established (2, 39). Regulatory T cells from NP animals were introduced at the beginning of late pregnancy, but prior to placental ischemia, and were able to prevent much of the pathophysiology that usually occurs in response to placental ischemia. This would suggest that the TReg maintenance of proper immune function may be important in the middle to late pregnancy, as well. From a clinical perspective, preeclampsia can develop in the middle of pregnancy (∼24 wk) or in late gestation (∼39 wk). Our study demonstrates that maintenance of proper immune regulation, even in middle to late gestation, may be important to blunt the inflammatory mediators leading to vasoactive pathways that cause hypertension and the pathophysiology that accompanies preeclampsia.

Inhibition of endogenous effector T-cell activation in RUPP rats could also be the mechanism by which inflammation and oxidative stress are decreased after adoptive transfer of TRegs from NP rats. Without T-cell activation, inflammatory cytokine production would be decreased. This, in turn, would result in fewer inflammatory cells and less production of ROS. Our previous study of T-cell depletion with abatacept indicated that decreasing the overall CD4+ T-cell count improved the pathology in RUPP rats. However, abatacept also inhibits maturation of T helper 2 and TRegs and, thereby, calling into question the maternal benefit of treating preeclampsia with a global T-cell inhibitor such as abatacept. Therefore, we feel it is important to continue looking for safe alternatives to boost Tregs during pregnancy. In our current study, we did not quantitate the total CD4+ T-cell population after TReg supplementation, nor did it measure the TReg/H17 ratio in our recipient rats (30). However, the data from this study suggest that supplementation of TRegs had a suppressive effect on immune activation, as supported by significant decreases in plasma TNF-α and IL-17, tissue oxidative stress, and AT1-AA.

Studies investigating the mechanistic pathways modulating TReg inhibition of the pathophysiology in preeclampsia need to be conducted. Supplementation of TReg soluble factors, such as IL-10, TGFβ, and IL-35, or IL-4 into preeclampsia animal models may provide insight into the mechanisms involved in the effect that TRegs have in averting preeclampsia. Future studies investigating TReg modalities or stimulators will be important to determine a role for the TReg cell in the normal development and growth of the fetus, as well as correcting the chronic inflammation known to exist following placental ischemia. These type of studies will lend insight into mechanisms and pathways that could lead to the identification of drug targets and development of more effective treatments for this maternal syndrome.

Perspectives and Significance

Importantly, this study demonstrates a role for decreased TRegs in the pathophysiology of preeclampsia. The data presented suggest that regulation of the immune response by TRegs is critical to maintenance of maternal health during pregnancy. Increasing the population of TRegs may help to normalize the altered immune response and regulate inflammation, resulting in decreased blood pressure, endothelial dysfunction, inflammation, oxidative stress, and AT1-AA production. The benefits of restoration in number of the TReg population could lead to healthier, prolonged pregnancies and decreases in the maternal and perinatal morbidity and mortality associated with preeclampsia.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: D.C.C., L.M.A., A.C.H., K.W., A.J.T., N.C., J.S., F.H., J.M., G.W., and R.D. performed experiments; D.C.C., L.M.A., A.C.H., K.W., F.H., N.H., G.W., R.D., and B.D.L. analyzed data; D.C.C., K.W., and B.D.L. prepared figures; D.C.C., K.W., and B.D.L. drafted manuscript; D.C.C., L.M.A., A.C.H., K.W., J.S., R.D., and B.D.L. edited and revised manuscript; D.C.C., L.M.A., A.C.H., K.W., A.J.T., N.C., J.S., F.H., N.H., G.W., R.D., and B.D.L. approved final version of manuscript; A.C.H., K.W., R.D., and B.D.L. interpreted results of experiments; R.D. and B.D.L. conception and design of research.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants HL-105324, HL-126301, HL-124715, HL-51971, HL-78147, and HD-067541. R. Dechend and F. Herse are supported by the German Research Foundation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alexander BT, Cockrell KL, Massey MB, Bennett WA, Granger JP. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha-induced hypertension in pregnant rats results in decreased renal neuronal nitric oxide synthase expression. Am J Hypertens 15: 170–175, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aluvihare VR, Kallikourdis M, Betz AG. Regulatory T cells mediate maternal tolerance to the fetus. Nat Immunol 5: 266–271, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bettini M, Vignali DA. Regulatory T cells and inhibitory cytokines in autoimmunity. Curr Opin Immunol 21: 612–618, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Conrad KP, Benyo DF. Placental cytokines and the pathogenesis of preeclampsia. Am J Reprod Immunol 37: 240–249, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Darmochwal-Kolarz D, Kludka-Sternik M, Tabarkiewicz J, Kolarz B, Rolinski J, Leszczynska-Gorzelak B, Oleszczuk J. The predominance of Th17 lymphocytes and decreased number and function of Treg cells in preeclampsia. J Reprod Immunol 93: 75–81, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dechend R, Homuth V, Wallukat G, Kreuzer J, Park JK, Theuer J, Juepner A, Gulba DC, Mackman N, Haller H, Luft FC. AT1 receptor agonistic antibodies from preeclamptic patients cause vascular cells to express tissue factor. Circulation 101: 2382–2387, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dechend R, Homuth V, Wallukat G, Muller DN, Krause M, Dudenhausen J, Haller H, Luft FC. Agonistic antibodies directed at the angiotensin II, AT1 receptor in preeclampsia. J Soc Gynecol Invest 13: 79–86, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Geiger TL, Tauro S. Nature and nurture in Foxp3+ regulatory T cell development, stability, and function. Hum Immunol 73: 232–239, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.George EM, Granger JP. Recent insights into the pathophysiology of preeclampsia. Expert Rev Obstet Gynecol 5: 557–566, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gilbert JS, Ryan MJ, LaMarca BB, Sedeek M, Murphy SR, Granger JP. Pathophysiology of hypertension during preeclampsia: linking placental ischemia with endothelial dysfunction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 294: H541–H550, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Granger JP, LaMarca BB, Cockrell K, Sedeek M, Balzi C, Chandler D, Bennett W. Reduced uterine perfusion pressure (RUPP) model for studying cardiovascular-renal dysfunction in response to placental ischemia. Methods Mol Med 122: 383–392, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harmon A, Cornelius D, Amaral L, Paige A, Herse F, Ibrahim T, Wallukat G, Faulkner J, Moseley J, Dechend R, LaMarca B. IL-10 supplementation increases Tregs and decreases hypertension in the RUPP rat model of preeclampsia. Hypertens Preg 34: 1–16, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoffmann DS, Weydert CJ, Lazartigues E, Kutschke WJ, Kienzle MF, Leach JE, Sharma JA, Sharma RV, Davisson RL. Chronic tempol prevents hypertension, proteinuria, and poor feto-placental outcomes in BPH/5 mouse model of preeclampsia. Hypertension 51: 1058–1065, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoffmann P, Eder R, Boeld TJ, Doser K, Piseshka B, Andreesen R, Edinger M. Only the CD45RA+ subpopulation of CD4+CD25 high T cells gives rise to homogeneous regulatory T-cell lines upon in vitro expansion. Blood 108: 4260–4267, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoffmann P, Eder R, Kunz-Schughart LA, Andreesen R, Edinger M. Large-scale in vitro expansion of polyclonal human CD4(+)CD25high regulatory T cells. Blood 104: 895–903, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hougardy JM, Verscheure V, Locht C, Mascart F. In vitro expansion of CD4+CD25highFOXP3+CD127low/−-regulatory T cells from peripheral blood lymphocytes of healthy Mycobacterium tuberculosis-infected humans. Microbes Infect 9: 1325–1332, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Housley WJ, Adams CO, Nichols FC, Puddington L, Lingenheld EG, Zhu L, Rajan TV, Clark RB. Natural but not inducible regulatory T cells require TNF-α signaling for in vivo function. J Immunol 186: 6779–6787, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.LaMarca B, Cornelius D, Wallace K. Elucidating immune mechanisms causing hypertension during pregnancy. Physiology 28: 225–233, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.LaMarca B, Parrish M, Ray LF, Murphy SR, Roberts L, Glover P, Wallukat G, Wenzel K, Cockrell K, Martin JN Jr, Ryan MJ, Dechend R. Hypertension in response to autoantibodies to the angiotensin II type I receptor (AT1-AA) in pregnant rats: role of endothelin-1. Hypertension 54: 905–909, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.LaMarca B, Speed J, Fournier L, Babcock SA, Berry H, Cockrell K, Granger JP. Hypertension in response to chronic reductions in uterine perfusion in pregnant rats: effect of tumor necrosis factor-alpha blockade. Hypertension 52: 1161–1167, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.LaMarca B, Wallace K, Herse F, Wallukat G, Martin JN Jr, Weimer A, Dechend R. Hypertension in response to placental ischemia during pregnancy: role of B lymphocytes. Hypertension 57: 865–871, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.LaMarca B, Wallukat G, Llinas M, Herse F, Dechend R, Granger JP. Autoantibodies to the angiotensin type I receptor in response to placental ischemia and tumor necrosis factor alpha in pregnant rats. Hypertension 52: 1168–1172, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.LaMarca BB, Bennett WA, Alexander BT, Cockrell K, Granger JP. Hypertension produced by reductions in uterine perfusion in the pregnant rat: role of tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Hypertension 46: 1022–1025, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.LaMarca BB, Cockrell K, Sullivan E, Bennett W, Granger JP. Role of endothelin in mediating tumor necrosis factor-induced hypertension in pregnant rats. Hypertension 46: 82–86, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.LaMarca BD, Alexander BT, Gilbert JS, Ryan MJ, Sedeek M, Murphy SR, Granger JP. Pathophysiology of hypertension in response to placental ischemia during pregnancy: a central role for endothelin? Gender Med 5 Suppl A: S133–S138, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.LaMarca BD, Gilbert J, Granger JP. Recent progress toward the understanding of the pathophysiology of hypertension during preeclampsia. Hypertension 51: 982–988, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li J, LaMarca B, Reckelhoff JF. A model of preeclampsia in rats: the reduced uterine perfusion pressure (RUPP) model. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 303: H1–H8, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matsubara K, Higaki T, Matsubara Y, Nawa A. Nitric oxide and reactive oxygen species in the pathogenesis of preeclampsia. Int J Mol Sci 16: 4600–4614, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Noris M, Perico N, Remuzzi G. Mechanisms of disease: Pre-eclampsia. Nat Clin Pract Nephrol 1: 98–114; quiz 120, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Novotny S, Wallace K, Herse F, Moseley J, Darby M, Heath J, Gill J, Wallukat G, Martin JN, Dechend R, Lamarca B. CD4+ T cells play a critical role in mediating hypertension in response to placental ischemia. J Hypertens 2: 14873, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Page EW. The relation between hydatid moles, relative ischemia of the gravid uterus, and the placentaal origin of eclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol 37: 291–293, 1939. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Parrish MR, Murphy SR, Rutland S, Wallace K, Wenzel K, Wallukat G, Keiser S, Ray LF, Dechend R, Martin JN, Granger JP, LaMarca B. The effect of immune factors, tumor necrosis factor-alpha, and agonistic autoantibodies to the angiotensin II type I receptor on soluble fms-like tyrosine-1 and soluble endoglin production in response to hypertension during pregnancy. Am J Hypertens 23: 911–916, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parrish MR, Ryan MJ, Glover P, Brewer J, Ray L, Dechend R, Martin JN Jr, Lamarca BB. Angiotensin II type 1 autoantibody induced hypertension during pregnancy is associated with renal endothelial dysfunction. Gender Med 8: 184–188, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Parrish MR, Wallace K, Tam Tam KB, Herse F, Weimer A, Wenzel K, Wallukat G, Ray LF, Arany M, Cockrell K, Martin JN, Dechend R, LaMarca B. Hypertension in response to AT1-AA: role of reactive oxygen species in pregnancy-induced hypertension. Am J Hypertens 24: 835–840, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Peterson RA. Regulatory T-cells: diverse phenotypes integral to immune homeostasis and suppression. Toxicol Pathol 40: 186–204, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Prins JR, Boelens HM, Heimweg J, Van der Heide S, Dubois AE, Van Oosterhout AJ, Erwich JJ. Preeclampsia is associated with lower percentages of regulatory T cells in maternal blood. Hypertens Pregnancy 28: 300–311, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Saito S. Th17 cells and regulatory T cells: new light on pathophysiology of preeclampsia. Immunol Cell Biol 88: 615–617, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Santner-Nanan B, Peek MJ, Khanam R, Richarts L, Zhu E, Fazekas de St Groth B, Nanan R. Systemic increase in the ratio between Foxp3+ and IL-17-producing CD4+ T cells in healthy pregnancy but not in preeclampsia. J Immunol 183: 7023–7030, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shima T, Sasaki Y, Itoh M, Nakashima A, Ishii N, Sugamura K, Saito S. Regulatory T cells are necessary for implantation and maintenance of early pregnancy but not late pregnancy in allogeneic mice. J Reprod Immunol 85: 121–129, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tam Tam KB, George E, Cockrell K, Arany M, Speed J, Martin JN Jr, Lamarca B, Granger JP. Endothelin type A receptor antagonist attenuates placental ischemia-induced hypertension and uterine vascular resistance. Am J Obstet Gynecol 204: 330 e331–e334, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Toldi G, Rigo J Jr, Stenczer B, Vasarhelyi B, Molvarec A. Increased prevalence of IL-17-producing peripheral blood lymphocytes in pre-eclampsia. Am J Reprod Immunol 66: 223–229, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Toldi G, Saito S, Shima T, Halmos A, Veresh Z, Vasarhelyi B, Rigo J Jr, Molvarec A. The frequency of peripheral blood CD4+ CD25high FoxP3+ and CD4+ CD25-FoxP3+ regulatory T cells in normal pregnancy and pre-eclampsia. Am J Reprod Immunol 68: 175–180, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Toldi G, Svec P, Vasarhelyi B, Meszaros G, Rigo J, Tulassay T, Treszl A. Decreased number of FoxP3+ regulatory T cells in preeclampsia. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 87: 1229–1233, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vacca P, Mingari MC, Moretta L. Natural killer cells in human pregnancy. J Reprod Immunol 97: 14–19, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vacca P, Moretta L, Moretta A, Mingari MC. Origin, phenotype and function of human natural killer cells in pregnancy. Trends Immunol 32: 517–523, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wallace K, Richards S, Dhillon P, Weimer A, Edholm ES, Bengten E, Wilson M, Martin JN Jr, LaMarca B. CD4+ T-helper cells stimulated in response to placental ischemia mediate hypertension during pregnancy. Hypertension 57: 949–955, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zenclussen AC, Fest S, Joachim R, Klapp BF, Arck PC. Introducing a mouse model for pre-eclampsia: adoptive transfer of activated Th1 cells leads to pre-eclampsia-like symptoms exclusively in pregnant mice. Eur J Immunol 34: 377–387, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]