Abstract

Context:

Patients with von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) syndrome have a 25–30% chance of developing pheochromocytoma. Although practice guidelines recommend biochemical and radiological screening every 1–2 years for pheochromocytoma in patients with VHL, there are limited data on the optimal age and frequency for screening.

Objective:

Our objective was to determine the earliest age of onset and frequency of contralateral and recurrent pheochromocytomas in patients with VHL syndrome.

Methods:

This is a retrospective analysis of a prospective cohort of patients with VHL enrolled in a natural history study.

Results:

A total of 273 patients diagnosed with VHL were enrolled in a natural history clinical study. Thirty-one percent (84) were diagnosed with pheochromocytoma. The mean age of diagnosis was 28.8 ± 13.9 years. The earliest age at diagnosis was 5.5 years. Median follow-up for the cohort was 116.6 months (range, 0.1–613.2). Ninety-nine percent (83) of patients underwent adrenalectomy. Fifty-eight and 32% of patients had metanephrines and/or catecholamines elevated more than two times and more than four times the upper limit of normal, respectively. Twenty-five percent (21) of pheochromocytomas were diagnosed in pediatric patients younger than 19 years of age, and 86% and 57% of pediatric patients had an elevation more than two times and more than four times upper limit of normal, respectively. Eight patients had a total of nine recurrences. The median age at recurrence was 33.5 years (range, 8.8–51.9). Recurrences occurred as short as 0.5 years and as long as 39.7 years after the initial operation.

Conclusions:

Our findings among VHL pediatric patients supports the need for biochemical screening starting at age 5 with annual lifelong screening.

Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome (VHL) is a hereditary disease with an incidence of 1 in 36 000 live births and 95% penetrance by 60 years of age (1–3). Pheochromocytomas are associated with type 2 VHL and affect 25–30% of all patients with VHL (4–6). VHL-associated pheochromocytomas arise during the third decade of life in most cases (4–6). In the pediatric population, pheochromocytomas may be the first manifestation of VHL (7). Screening guidelines for adults with VHL have been established and provide clinicians with a clear care plan for pheochromocytoma screening and monitoring. However, in pediatric patients with VHL, the screening guidelines are less clear and provide no widely accepted age of when to initiate biochemical screening for pheochromocytoma. Moreover, it is unclear how frequently patients (pediatric and adult) with VHL should have screening for pheochromocytoma and what the subsequent risk of a second primary pheochromocytoma and recurrence is in patients who undergo partial or total adrenalectomy. Hence, well-designed studies are essential to provide evidence-based guidelines for optimal timing and frequency of screening for pheochromocytoma in patients with VHL.

The purpose of this study was to evaluate patients with VHL-associated pheochromocytoma, to determine the youngest age of onset, the biochemical profile of VHL-associated pheochromocytomas, and the risk of contralateral lesions and recurrent disease.

Materials and Methods

We conducted a retrospective analysis of a prospective natural history study of patients with VHL enrolled at the National Cancer Institute (clinicaltrials.gov: NCT00062166) from 2002 to 2015. This study was approved by the National Cancer Institute's Institutional Review Board. Patients gave written informed consent.

Patient population

Two hundred seventy-three patients diagnosed with VHL were enrolled in the study; 189 patients did not have or develop adrenal pheochromocytoma and 84 patients (31%) had a history or developed a pheochromocytoma during the study period. Clinical, demographic, laboratory, and histopathologic data were collected prospectively. However, data on previous pheochromocytoma diagnosis and treatment before study enrollment was also ascertained but laboratory data points were not available for 46 of 84 patients. Patients had annual follow-up with 24-hour urinary and serum catecholamines and metanephrine measurements. Patients were all taken off any medications known to interfere with the testing for catecholamines, metanephrines, and vanillylmandelic acid. All patients had annual imaging with computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan to monitor for renal and pancreatic manifestations of VHL, and adrenal specific anatomic imaging when the catecholamine and or metanephrine levels were greater than two times the upper limit of normal (ULN).

Pediatric patients were defined as younger than 19 years old at diagnosis of the first pheochromocytoma. Primary pheochromocytoma was defined as the first pheochromocytoma diagnosed, second primary pheochromocytoma was defined as tumor development in the contralateral adrenal, and recurrence was defined as pheochromocytoma development in a previously operated adrenal gland/adrenal bed or metastatic disease. Follow-up was defined from the date of initial pheochromocytoma diagnosis to the date of last follow-up in patients with pheochromocytoma and from the date of VHL diagnosis to date of last follow-up for patients without pheochromocytoma. Laboratory values are reported as normal, elevated, two times the ULN and four times the ULN of the reference range as the reference laboratory values changed during the study period. Normal values were defined as a value that was below the ULN for a given test and elevated was defined as a laboratory value that was greater than the ULN but less than two times the ULN for a given test. Two times the ULN was defined as a value that was greater than two times the upper limit but less than four times, and four times the ULN was defined when the value exceed four times the ULN. These cutoffs were defined arbitrarily for data analysis.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 5 software (GraphPad Software). Parametric and nonparametric data were analyzed using a two-tailed t test and the Mann-Whitney U test, respectively. Two-tailed P < .05 was considered statistically significant. Data are presented as mean ± SD or median (range).

Results

Eight-four (31%) of 273 patients with VHL enrolled in the clinical protocol were diagnosed with a pheochromocytoma during a median follow-up of 116.6 weeks (range, 0.1–613.2 weeks). There were 189 patients enrolled in the protocol who did not develop a pheochromocytoma over a median follow-up of 203.8 months (range, 0.7–912). The demographics and clinical characteristics of the study cohort are summarized in Table 1. Eighty-three (99%) patients diagnosed with pheochromocytoma underwent surgical resection. Sixty-two (75%) patients presented with a unilateral adrenal pheochromocytoma and 13 (16%) presented with bilateral adrenal pheochromocytomas. Seventeen (20%) patients developed a contralateral second primary tumor requiring adrenalectomy, and five of 17 of these patients had hypertension. The median interval between the first and second primary pheochromocytoma was 4.2 years (range, 0.21–28 years). Table 2 shows the time interval between the development of the first and second primary tumor in each patient.

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Study Cohort (n = 273)

| Variable | Pheochromocytoma Group (n = 84) | Non-Pheochromocytoma Group (n = 189) |

|---|---|---|

| Value n (%) or n (Range) | Value n (%) or n (Range) | |

| Median age of VHL diagnosis | 27.6 (5–68) | 25.6 (4.7–63.5) |

| Median age of pheochromocytoma diagnosis | 28 (5.5–68) | NA |

| Male:female | 46:38 | 80:109 |

| Pediatric patients (<19 years) | 21 | 44 |

| Median age of pheochromocytoma diagnosis in pediatric group | 12.4 (5.5–18.7) | NA |

| Follow-up duration (weeks) | 116.6 (0.1–613.2) | 203.8 (0.7–912) |

| Location of tumor at first surgery | ||

| Left adrenal (%) | 35 (45.2) | NA |

| Right adrenal (%) | 27 (32.1) | NA |

| Bilateral adrenal (%) | 13 (15.5) | NA |

| Retroperitoneal (%) | 4 (4.8) | NA |

| Periadrenal (%) | 1 (1) | NA |

| Unknown (%) | 3 (3.6) | NA |

| Pathology of tumor at first surgery | ||

| Pheochromocytoma (%) | 81 (96.4) | NA |

| Missing (%) | 3 (3.6) | NA |

| Median tumor size at first surgerya | 2.7 cm (0.6–18) | NA |

| Second surgery for primary tumor (n) | 17 | NA |

| Recurrences (n) | 9 | NA |

Abbreviation: NA, not applicable.

Including additional tumors that were identified at the time of partial adrenalectomy.

Table 2.

Age and Time Interval Between Primary Pheochromocytoma Diagnosis and Recurrences

| Patient No. | Age at Time of Second Primary Tumor (years) | Interval Between First and Second Primary Tumors (months) | Age at Time of First Recurrence (years) | Interval Between Primary Tumor and First Recurrence (months) | Age at Time of Second Recurrence (years) | Interval Between Primary Tumor and Second Recurrence (months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 42 | 25.4 | 31.2 | ||||

| 53 | 39.5 | 336.0 | ||||

| 79 | 27.2 | 70.1 | ||||

| 84 | 22.4 | 120.0 | ||||

| 127 | 26.2 | 106.0 | ||||

| 128 | 32.9 | 255.1 | ||||

| 130 | 17.4 | 50.0 | 17.4 | 50.0 | ||

| 139 | 28.2 | 2.5 | ||||

| 154 | 18.9 | 22.8 | ||||

| 207 | 45.4 | 312.0 | ||||

| 246 | 23.1 | 3.9 | ||||

| 248 | 39.3 | 91.7 | 33.5 | 21.3 | ||

| 250 | 28.3 | 1.7 | ||||

| 252 | 18.4 | 30.1 | ||||

| 253 | 8.3 | 25.5 | ||||

| 266 | 8.4 | 17.4 | 8.8 | 6.0 | ||

| 271 | 26.0 | 86.7 | ||||

| 17 | 51.9 | 229.5 | ||||

| 135 | 41.9 | 123.7 | ||||

| 234 | 17.9 | 72.0 | 51.6 | 476.0 | ||

| 258 | 17.0 | 10.8 | ||||

| 261 | 47.9 | 52.3 |

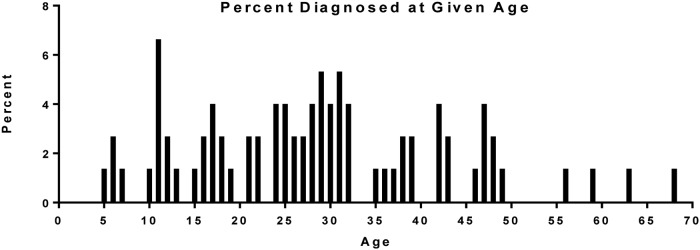

Twenty-one (25%) patients were diagnosed as pediatric patients on initial pheochromocytoma presentation. Figure 1 shows the percentage of patients per age group at the time of pheochromocytoma diagnosis. The youngest age at diagnosis was 5.5 years; the median age of diagnosis in the pediatric subgroup was 12.4 years (range, 5.5–18.7 years). The youngest patient was initially diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder before being referred to our clinic for VHL, at which time a diagnosis of pheochromocytoma was made. Two-thirds (14) of patients presented with unilateral adrenal masses and 19% (4) of patients had bilateral adrenal pheochromocytomas at presentation. Eight (38%) patients presented with a contralateral second primary tumor. Fifteen (71%) pediatric patients presented with symptomatic pheochromocytomas. Two patients were asymptomatic and four had unknown symptom status at time of pheochromocytoma diagnosis. Seventeen (81%) of the 21 pediatric patients had a known family history of VHL before their diagnosis of pheochromocytoma and three (14%) patients were index cases and underwent genetic testing when diagnosed with a pheochromocytoma. Table 3 summarizes the demographic characteristics comparing the pediatric and adult pheochromocytoma cohorts. The two groups were similar with exception of age of VHL and pheochromocytoma diagnosis.

Figure 1.

Age of first pheochromocytoma diagnosis in study cohort (n = 84). Age in years.

Table 3.

Demographic Data of Pediatric and Adult Pheochromocytoma Patients

| Variable | Pediatric Group (n = 21) | Adult Group (n = 63) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Value n (%) or n (Range) | Value n (%) or n (Range) | ||

| Median age of VHL diagnosis | 12.4 (5.5–18.7) | 25.8 (2.6–57.4) | <.0001 |

| Median age of pheochromocytoma diagnosis | 12.4 (5.5–18.7) | 31.8 (19.4–68.9) | <.0001 |

| Male | 15 (71.4) | 31 (49.2) | .08 |

| Female | 6 (28.6) | 32 (50.8) | |

| Follow-up duration (months) | 193.9 (0.5–613.2) | 88.2 (0.1–575.1) | .13 |

| Location of tumor at first surgery | |||

| Unilateral adrenal (%) | 14 (66.7) | 45 (71.4) | .6 |

| Bilateral adrenal (%) | 4 (19) | 8 (12.7) | .5 |

| Retroperitoneal (%) | 2 (9.5) | 2 (3.2) | .26 |

| Periadrenal (%) | 1 (4.8) | 0 | .25 |

| Unknown (%) | 0 | 7 (11.1) | .2 |

| Pathology of tumor at first surgery | |||

| Pheochromocytoma (%) | 18 (85.7) | 53 (84.1) | .33 |

| Paraganglioma (%) | 3 (14.3) | 1 (1.6) | .06 |

| Unknown (%) | 0 | 2 (3.2) | 1.0 |

| Median tumor size at first surgery | 3.1 (1.4–5) | 2.7 (0.6–18) | .81 |

| Second surgery for primary tumor (n) | 10 | 7 | .49 |

| Recurrences (n) | 5 | 4 | 1.0 |

| Preoperative laboratory values (n)a | 7 | 31 | |

| Elevated but <2 times ULN | 3 | 11 | .4 |

| ≥2 times ULN but <4 times ULN | 0 | 9 | .16 |

| ≥4 times ULN | 4 | 11 | .4 |

| Dominant preoperative biochemical abnormalitya | |||

| Metanephrine | 0 | 1 | |

| Normetanephrine | 7 | 25 | .57 |

| Dopamine | 0 | 0 | |

| Epinephrine | 0 | 1 | |

| Norepinephrine | 6 | 6 | .002 |

First primary surgery only.

Eight patients had nine total recurrences during the study follow-up period after partial adrenalectomy. In three of the nine recurrences, the patients had hypertension at the time of their diagnosis of recurrence. Summarized in Table 2 is the interval between the primary tumor removal and the development of recurrence. The shortest recurrence interval in the cohort was 0.5 years and the longest was 39.7 years after the primary pheochromocytoma removal. The median age at recurrence was 33.5 years (range, 8.8–51.9) for the entire cohort and 17.2 years (range, 8.8–51.9) for the pediatric cohort. Four (50%) of the nine patients with recurrence were pediatric patients and developed their recurrence before age 19. Table 2 summarizes patient age at the time of recurrence. There was no significant association between age at diagnosis and time to first recurrence (P = .84).

Laboratory evaluation

Thirty-eight patients in the cohort had laboratory evaluation of metanephrines and catecholamines 12 months or less before surgical intervention at our institution. Thirty-four (89.5%) patients had elevated biochemical markers. Twenty-four (63.2%) and 15 (39.5%) patients had plasma or urinary catecholamines or metanephrines more than two times the ULN and more than four times the ULN, respectively. Summarized in Table 4 are the preoperative laboratory data. Most patients had elevated normetanephrine or norepinephrine preoperatively. Twenty-one percent (8) had urinary normetanephrine levels more than four times the ULN and 34% (13) had serum normetanephrine more than four times the ULN.

Table 4.

Preoperative Adrenergic and Noradrenergic Characteristics of All Surgical Patientsa

| Laboratory Parameter (n = 38) | Normal n (%) | Elevated n (%) | ≥2 Times ULN n (%) | ≥4 Times ULN n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serum | ||||

| Metanephrine | 20 (52.6) | 1 (2.6) | 0 | 0 |

| Normetanephrine | 1 (2.6) | 9 (23.7) | 7 (18.4) | 13 (34.2) |

| Dopamine | 19 (50) | 1 (2.6) | 2 (5.3) | 1 (2.6) |

| Epinephrine | 21 (55.3) | 1 (2.6) | 0 | 0 |

| Norepinephrine | 10 (26.3) | 9 (23.7) | 3 (7.9) | 8 (21.1) |

| Urinary | ||||

| Metanephrine | 25 (65.9) | 0 | 2 (5.3) | 0 |

| Normetanephrine | 1 (2.6) | 11 (28.9) | 8 (21.1) | 8 (21.1) |

| Dopamine | 26 (68.4) | 2 (5.3) | 0 | 0 |

| Epinephrine | 26 (68.4) | 0 | 1 (2.6) | 1 (2.6) |

| Norepinephrine | 13 (34.2) | 6 (15.8) | 1 (2.6) | 7 (18.4) |

| VMA | 17 (44.7) | 1 (2.6) | 0 | 2 (5.3) |

Abbreviation: VMA, vanillylmandelic acid.

Some patients had elevation in more than one laboratory value; therefore, the total number does not equal the number of patients but number rather of elevated values.

In the pediatric cohort, seven patients had preoperative values for metanephrines and catecholamines at our institution within 1 year before pheochromocytoma surgery. All pediatric patients had elevated preoperative serum and/or urinary normetanephrine levels and 86% (6) had at least two times the ULN. Fifty-seven percent (4) had serum and/or urinary levels that were more than four times the ULN. Serum and urinary norepinephrine were more than four times the ULN in 29% (2) and 43% (3) of patients, respectively. Table 5 summarizes the preoperative laboratory phenotype for the pediatric cohort. Table 3 compares the preoperative biochemical evaluation at the first primary adrenal surgery between the pediatric and adult cohorts. One significant difference between the two cohorts was that pediatric pheochromocytoma patients were more likely to have both normetanephrine and norepinephrine elevated as compared to only normetanephrine elevation in the adult cohort.

Table 5.

Preoperative Adrenergic and Noradrenergic Characteristics of Pediatric Surgical Patientsa

| Laboratory Parameter (n = 7) | Normal n (%) | Elevated n (%) | ≥2 Times ULN n (%) | ≥4 Times ULN n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serum | ||||

| Metanephrine | 6 (85.7) | 1 (14.3) | 0 | 0 |

| Normetanephrine | 0 | 3 (42.9) | 0 | 4 (57.1) |

| Dopamine | 5 (71.4) | 1 (14.3) | 1 (14.3) | 0 |

| Epinephrine | 6 (85.7) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Norepinephrine | 2 (28.6) | 1 (14.3) | 2 (28.6) | 2 (28.6) |

| Urinary | ||||

| Metanephrine | 6 (85.7) | 0 | 1 (14.3) | 0 |

| Normetanephrine | 0 | 3 (42.9) | 0 | 4 (57.1) |

| Dopamine | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Epinephrine | 6 (85.7) | 0 | 0 | 1 (14.3) |

| Norepinephrine | 3 (42.9) | 1 (14.3) | 0 | 3 (42.9) |

| VMA | 2 (28.6) | 1 (14.3) | 0 | 0 |

Abbreviation: VMA, vanillylmandelic acid.

Some patients had elevation in more than one laboratory value; therefore, the total number does not equal the number of patients but number rather of elevated values.

Thirty-four patients in the study had postoperative laboratory evaluation at a median follow-up of 14.6 months (range, 2.3–24.8 months). Six of these patients were pediatric patients with postoperative laboratory evaluation at a median follow-up of 9.7 months (range, 4.5–15.5 months). The majority (67.6%) of patients had normalization of their laboratory values postoperatively. Four patients (11.8%) had mildly elevated laboratory values, six (17.6%) patients had laboratory values elevated two times the ULN, and only one (2.9%) patient had an elevation four times the ULN. Two of the six patients with elevations two times the ULN were pediatric patients. One of the two pediatric patients had a contralateral pheochromocytoma that was removed 10.8 months later with normalization of elevated laboratory values. The other patient had a contralateral pheochromocytoma that was resected 30.1 months after the first surgery and postoperative laboratory values were not available after the second primary tumor surgery. The remaining four patients with elevations greater than two times the ULN were not pediatric patients. One of these four had normalization of labs 28 months postsurgery, one patient was lost to follow-up after 11.1 month postoperatively, one patient continued with elevated biochemical laboratory values secondary to metastatic pheochromocytoma, and the final patient had a contralateral right lesion and a recurrence in the left adrenal bed with eventual resolution of laboratory values after additional surgery. The patient with postoperative laboratory values four times the ULN was a pediatric patient with an additional primary tumor on the contralateral side that underwent surgical resection 17.4 months later with normalization of catecholamines and metanephrines postoperatively.

Of the 189 patients without pheochromocytoma, 21 (9.5%) had an elevation in either catecholamines or metanephrines at last follow-up. Three (1.6%) patients had biochemical elevation two times the ULN without evidence of a lesion on anatomic imaging with CT scan or MRI. No patient had biochemical elevations four times the ULN at last follow-up.

Discussion

Early diagnosis of VHL is critical to achieving successful patient outcomes by implementing optimal evidence-based surveillance programs. Current screening guidelines recommend annual metanephrine and catecholamine screening for adult patients. There is little consensus on the earliest age to initiate biochemical screening and how frequently such screening should be performed. Some guidelines recommend annual blood pressure monitoring and initiation of biochemical screening at 8 years of age in families with known pheochromocytoma (8, 9). Lefebvre and Foulkes recommend annual blood pressure screening starting at 5 years of age and initiation of biochemical screening at 11 years of age (10). Others have suggested earlier biochemical screening beginning at 5 years of age (11, 12). Our data support the initiation of biochemical screening at 5 years of age given that the earliest age of pheochromocytoma diagnosis was 5.5 years in our study.

Biochemical elevation of plasma metanephrines and/or urinary catecholamines and fractionated metanephrines are required for the diagnosis of pheochromocytoma. VHL-associated pheochromocytomas are known to secrete noradrenergic compounds and very rarely to secrete adrenergic compounds (12–15). Normetanephrine was the most commonly elevated laboratory value in our cohort followed by norepinephrine. All of the pediatric patients in our cohort had evidence of elevation in normetanephrine levels and more than 87% had elevations more than two times the ULN. These data support the abnormal noradrenergic hormonal secretion in pediatric patients and confirm that the use of biochemical screening in young patients with VHL is prudent.

Children compose 20% of the pheochromocytoma population and, unlike adults, most of them have a hereditary syndrome (16). More than half of the hereditary pheochromocytomas in pediatric patients are caused by VHL, thus necessitating clear comprehensive guidelines for this age group (16–19). Our study represents a large number of pediatric patients, with 25% of the study cohort consisting of patients younger than 19 years of age at the time of diagnosis. In addition, what would be considered routine anatomical imaging in adults is challenging in children. The young age of potential pheochromocytoma development increases the cumulative lifetime exposure of ionizing radiation and development of secondary malignancies with CT scans. MRI has become the preferred form of cross-sectional imaging in the pediatric population. However, this modality requires extended periods without movement, which is a challenge in the pediatric population and may require general anesthesia and significant logistical support (20). Therefore, given the young age of pheochromocytoma development and the clear evidence of biochemical elevation in our cohort, we support the role of early routine metanephrine and catecholamine screening in pediatric patients with VHL and the use of anatomic imaging for localization of pheochromocytomas in patients with elevated normetanephrine and/or norepinephrine more than two times the ULN. Furthermore, we believe the first age of onset should guide when to start screening patients with VHL for pheochromocytoma. Although pheochromocytomas are not malignant/metastatic in most patients with VHL, we have seen three patients develop metastatic disease albeit at an older age. Last, biochemical testing is not invasive, even though it may be difficult in children to collect 24-hour urine samples.

VHL presents a lifetime risk of developing pheochromocytoma that requires surveillance throughout a patient's life. Recently, Bausch et al reported a 38% risk of developing a second (new primary or recurrence) paraganglioma in pediatric patients diagnosed with pheochromocytoma (16). They described an increasing frequency of second tumors over time, with the risk reaching 50% at 30 years from initial diagnosis (16). In our study, 17 patients developed a second primary pheochromocytoma in the contralateral adrenal gland. The longest interval between the two primary tumors was 28 years and the shortest interval was 0.21 years. Our cohort also had nine recurrences in eight patients, with the longest interval between primary surgery and development of recurrence being 39.7 years and the shortest being 0.5 years. The chance of tumor recurrence or development of a second primary tumor resulting from the hereditary nature of VHL supports the need for lifelong surveillance. In addition, the increasing use of partial adrenalectomies in patients with VHL, to minimize the need for lifelong steroid replacement, may increase the risk of recurrent pheochromocytomas developing in the remnant adrenal gland (21). Therefore, given the long term between primary surgery and development of either a second primary lesion or a recurrent lesion, yearly lifelong biochemical surveillance is needed for monitoring and early detection of a new (second primary) or recurrent pheochromocytoma.

There are several limitations to our study. Although patients were enrolled in a prospective study, data on previous pheochromocytoma diagnosis and treatment before study enrollment were ascertained, but no laboratory data were available for those patients treated at another institution. Also, the follow-up regimen in these patients before enrollment into our study protocol was not standardized to allow direct comparison in all cases. Furthermore, we did not have follow-up data on all patients enrolled in the protocol and within 1 year because the patients did not return for follow-up. Thus, a pheochromocytoma might have been missed in those patients who had no biochemical follow-up.

Conclusions

Our data support biochemical screening for pheochromocytoma in pediatric patients with VHL starting at 5 years of age with lifelong biochemical surveillance every year and the use of anatomic imaging when normetanephrine levels are elevated more than two times the ULN.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ms Lily Yang for database management and Ms Roxanne Merkel and Candice Cottle-Delisle for patient coordination and protocol management.

This research was supported by the intramural research programs of the Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Footnotes

- CT

- computed tomography

- MRI

- magnetic resonance imaging

- ULN

- upper limit of normal

- VHL

- von Hipple-Lindau.

References

- 1. Maher ER, Iselius L, Yates JR, et al. Von Hippel-Lindau disease: a genetic study. J Med Genet. 1991;28:443–447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Maddock IR, Moran A, Maher ER, et al. A genetic register for von Hippel-Lindau disease. J Med Genet. 1996;33:120–127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Neumann HP, Wiestler OD. Clustering of features and genetics of von Hippel-Lindau syndrome. Lancet. 199;338:258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ong KR, Woodward ER, Killick P, Lim C, Macdonald F, Maher ER. Genotype-phenotype correlations in von Hippel-Lindau disease. Hum Mutat. 2007;28:143–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Maher ER, Yates JR, Harries R, et al. Clinical features and natural history of von Hippel-Lindau disease. Q J Med. 1990;77:1151–1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Richard S, Beigelman C, Duclos JM, et al. Pheochromocytoma as the first manifestation of von Hippel-Lindau disease. Surgery. 1994;116:1076–1081. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Barontini M, Dahia PL. VHL disease. Best practice, research Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;24:401–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Maher ER. Von Hippel-Lindau disease. Curr Mole Med. 2004;4:833–842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Richard S, Graff J, Lindau J, Resche F. Von Hippel-Lindau disease. Lancet. 2004;363:1231–1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lefebvre M, Foulkes WD. Pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma syndromes: genetics and management update. Curr Oncol. 2014;21:e8–e17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Binderup ML, Bisgaard ML, Harbud V, et al. Von Hippel-Lindau disease (vHL). National clinical guideline for diagnosis and surveillance in Denmark. 3rd ed. Dan Med J. 2013;60:B4763. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Waguespack SG, Rich T, Grubbs E, et al. A current review of the etiology, diagnosis, and treatment of pediatric pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:2023–2037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Eisenhofer G, Lenders JW, Linehan WM, Walther MM, Goldstein DS, Keiser HR. Plasma normetanephrine and metanephrine for detecting pheochromocytoma in von Hippel-Lindau disease and multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1872–1879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pacak K, Eisenhofer G, Ilias I. Diagnosis of pheochromocytoma with special emphasis on MEN2 syndrome. Hormones. 2009;8:111–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Eisenhofer G, Lenders JW, Timmers H, et al. Measurements of plasma methoxytyramine, normetanephrine, and metanephrine as discriminators of different hereditary forms of pheochromocytoma. Clin Chem. 2011;57:411–420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bausch B, Wellner U, Bausch D, et al. Long-term prognosis of patients with pediatric pheochromocytoma. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2014;21:17–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Barontini M, Levin G, Sanso G. Characteristics of pheochromocytoma in a 4- to 20-year-old population. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2006;1073:30–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Neumann HP, Bausch B, McWhinney SR, et al. Germ-line mutations in nonsyndromic pheochromocytoma. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1459–1466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Armstrong R, Sridhar M, Greenhalgh KL, et al. Phaeochromocytoma in children. Arch Dis Child. 2008;93:899–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Schmid S, Gillessen S, Binet I, et al. Management of von Hippel-Lindau disease: an interdisciplinary review. Oncol Res Treat. 2014;37:761–771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Volkin D, Yerram N, Ahmed F, et al. Partial adrenalectomy minimizes the need for long-term hormone replacement in pediatric patients with pheochromocytoma and von Hippel-Lindau syndrome. J Pediatr Surg. 2012;47:2077–2082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]