Abstract

Context:

The Chinese were afflicted by great famine between 1959 and 1962. These people then experienced rapid economic development during which the gross domestic product per capita increased from $28 in 1978 to $6807 in 2013. We hypothesize that these two events are associated with the booming rate of diabetes in China.

Objective:

We aimed to explore whether exposure to famine in early life and high economic status in adulthood was associated with diabetes in later life.

Design and Setting:

Our data of 6897 adults were from a cross-sectional Survey on Prevalence in East China for Metabolic Diseases and Risk Factors study in 2014. Among them, 3844 adults experienced famine during different life stages and then lived in areas with different economic statuses in adulthood.

Main Outcome Measure:

Diabetes was considered as fasting plasma glucose of 7.0mmol/L or greater, hemoglobin A1c of 6.5% or greater, and/or a previous diagnosis by health care professionals.

Results:

Compared with nonexposed subjects, famine exposure during the fetal period (odds ratio [OR]1.53, 95% confidence interval [CI]1.09–2.14) and childhood (OR 1.82, 95% CI 1.21–2.73) was associated with diabetes after adjusting for age and gender. Further adjustments for adiposity, height, the lipid profile, and blood pressure did not significantly attenuate this association. Subjects living in areas with high economic status had a greater diabetes risk in adulthood (OR 1.46, 95% CI 1.20–1.78). In gender-specific analyses, fetal-exposed men (OR 1.64, 95% CI, 1.04–2.59) and childhood-exposed women (OR 2.81, 95% CI, 1.59–4.97) had significantly greater risk of diabetes.

Conclusions:

The rapid increase in the prevalence of diabetes in middle-aged and elderly people in China is associated with the combination of exposure to famine during the fetal stage and childhood and high economic status in adulthood. Our findings may partly explain the booming diabetes phenomenon in China.

In China, the prevalence of diabetes has increased to 11.6% and is associated with rapid economic growth during the most recent 3 decades (1, 2). However, the observation that the diabetes prevalence in China exceeds that in the United States cannot be explained simply by economic factors (3). The famine in China from 1959 to 1962, called China's Great Famine, may be another factor. The developmental origin hypothesis postulates that responsiveness to malnutrition in early life or in utero leads to metabolic and structural changes (4). This responsiveness might be useful to survive in early life but also increases the risk of diabetes in later life.

The association between prenatal malnutrition and later-life metabolic outcomes has been well supported by animal studies showing that impaired glucose homeostasis can be induced by malnutrition during gestation (5). In human beings, prenatal exposure to undernutrition in people born during the Dutch famine (6, 7), during China's Great Famine (8), and in poor countries (9) is linked to impaired glucose tolerance or diabetes in later life. On the other hand, the long-term effects of postnatal exposure to undernutrition on metabolic status are relatively unclear. It has been reported that women exposed to undernutrition during childhood had an increased diabetes risk in adulthood (10, 11). However, another study found that diabetes is diagnosed more often in women exposed to severe undernutrition between the ages of 11–14 years (adolescence) (12). Using national data from 1 decade ago, Li et al (8) reported no significant association between famine exposure in early life and diabetes. Thus, because of different cohort ethnicities, inconsistent conclusions, and limited sex-specific results, the effect of early-life exposure to famine on the risk of diabetes needs further study.

Economic development increases the average income, which in turn improves nutritional status (13). However, a low-birth-weight baby who gained weight rapidly (overnutrition) in later life may represent the worst-case scenario for metabolic diseases (14). Therefore, individuals who were exposed to famine and then experienced the nutritional excess brought on by economic development may have an unusually high risk of diabetes.

We performed a large investigation called the Survey on Prevalence in East China for Metabolic Diseases and Risk Factors (SPECT-China) in 2014 to analyze the relationship between famine exposure in early life, economic development during adulthood, and risk of diabetes.

Materials and Methods

Study population

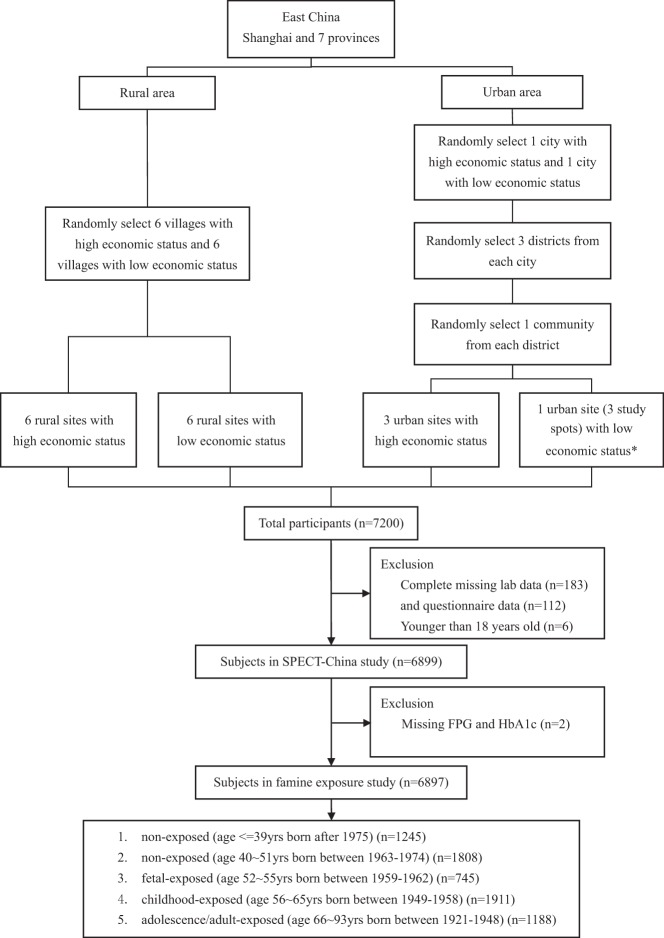

SPECT-China is a cross-sectional survey on the prevalence of metabolic diseases and risk factors in east China. The registration number is ChiCTR-ECS-14005052 (www.chictr.org.cn). We used a stratified cluster sampling method to select a sample in the general population. The sampling process was stratified according to rural/urban area and economic development status in Shanghai, Jiangxi Province, and Zhejiang Province (Figure 1). Random sampling was completed with IBM SPSS Statistics, version 22 (IBM Corp) before data collection. In urban areas, we randomly chose one city with a low economic status and one city with a high economic status. Then, in both cities, we randomly chose three districts. In each district, three communities were randomly selected. Because the three communities chosen in Jiangxi Province were all very large communities, to maintain the study feasibility and to avoid oversampling in this area, we randomly chose one community (three study spots) from these three communities. In rural areas, we randomly chose six villages with low economic status and six villages with high economic status. From February to June 2014, this study was performed in three urban sites in Shanghai, one urban site in Jiangxi Province, three rural sites in Shanghai, three rural sites in Zhejiang, and six rural sites in Jiangxi Province. Adults aged 18 years old and older who were Chinese citizens and lived in their current residence for 6 months or longer were selected and invited into our study. Those with severe communication problems, acute illness, and an unwillingness to participate were excluded from the study (n = 551). A total of 7927 individuals were selected, and finally 7200 people participated in this investigation. The overall response rate was 90.8%. We excluded participants who were missing laboratory results (n = 183), were missing questionnaire data (n = 112), and were younger than 18 years old (n = 6). In total, 6899 subjects were included in the SPECT-China study. Finally, after excluding participants who had missing fasting plasma glucose (FPG) and hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) results (n = 2), 6897 subjects were included in this famine exposure study.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the sampling frame and participants in the famine exposure study selected from SPECT-China. *, Because the three communities chosen were all very large communities, to maintain the study feasibility and avoid oversampling in this area, we randomly chose one community (three study spots) from these three communities.

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shanghai Ninth People's Hospital, Shanghai JiaoTong University School of Medicine. All participants provided written informed consent before data collection.

Clinical, anthropometric, and laboratory measurements

The same staff performed all data collection. They were trained according to a standard protocol that made them familiar with the specific tools and methods used. Trained staff used a questionnaire to collect information on the demographic characteristics, medical history, and lifestyle risk factors. Current smoking was defined as having smoked at least 100 cigarettes in one's lifetime and currently smoking cigarettes (2). Self-reported educational levels ranging from illiteracy to junior and senior high school and to college and postgraduate were recorded as illiterate and nonilliterate. Body weight, height, waist circumference, and blood pressure (BP) were measured with the use of standard methods as described previously (2). Central obesity was defined as a waist circumference of 90 cm or greater in males or of 80 cm or greater in females (15).

Venous blood samples were drawn after an overnight fast of at least 8 hours. The blood samples for the plasma glucose test were collected into vacuum tubes with the anticoagulant sodium fluoride and centrifuged within 1 hour after collection. Blood samples were stored at −20°C when collected and shipped by air on dry ice to a central laboratory within 2–4 hours of collection, which was certified by the College of American Pathologists. HbA1c was assessed by HPLC (MQ-2000PT, Medconn, Shanghai, China). FPG and the lipid profile, including total cholesterol, triglycerides, high-density lipoprotein (HDL), and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) were measured by a Beckman Coulter AU 680 and insulin by chemiluminescence method (Abbott i2000 SR). Insulin resistance was estimated by the homeostasis model assessment index of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR): (fasting insulin [milliinternational units per liter]) × (FPG [millimoles per liter])/(22.5) (16). Insulin secretion was estimated by the homeostasis model of β-cell function (HOMA-β) percentage (HOMA-β%): (20 × fasting insulin [milliinternational units per liter])/(FPG [millimoles per liter] − 3.5] (percentage) (16) and by the disposition index, calculated as HOMA-β%/HOMA-IR (17).

Exposure age and area categories

Compared with the Dutch Famine, the Great Chinese Famine lasted longer, from the late 1950s to the early 1960s, and affected more people, causing approximately 20 million to 30 million deaths (18, 19). The famine exposure period was between 1959 and 1962 (18).

Exposure to famine was based on a proxy, the year of birth. Based on the study by van Abeelen et al (10) and Bogin's life cycle theory (20), subjects were categorized into five groups according to their life stages when exposed to famine from January 1, 1959, to December 31, 1962: fetal period (current age 52–55 y) born between 1959 and 1962 (n = 745), childhood (current age 56–65 y) born between 1949 and 1958 (n = 1911), adolescence and young adult (current age 66–93 y) born between 1921 and 1948 (n = 1188), nonexposed (current age 40–51 y) born between 1963 and 1974 (n = 1808), and nonexposed (current age ≤ 39 y) born after 1975 (n = 1245). In China, the prevalence of diabetes has risen dramatically in people older than 40 years (2). As such, we separated the nonexposed group into two groups: current age of 40–51 years and current age of 39 years or younger.

Current economic status was assessed by the gross domestic product (GDP) per capita in 2013 at each site (8). Each of the 16 study sites was categorized into high and low economic status according to the GDP per capita of the whole nation (6,07 US dollars from the World Bank) in 2013. If the GDP per capita of the site was higher than the national GDP per capita, it was regarded as having a high economic status and vice versa.

Because of preferential food supply to cities, rural areas were more severely affected by famine than urban areas (19). Rural areas also had different characteristics from urban areas, including education and dietary patterns. Hence, rural/urban residence was chosen as one of the covariates.

Definition of type 2 diabetes

In accordance with the American Diabetes Association 2014 criteria, diabetes was defined as a previous diagnosis by health care professionals or an FPG of 7.0 mmol/L or higher or an HbA1c of 6.5% or higher.

Statistical analysis

We performed survey analyses with IBM SPSS Statistics, version 22 (IBM Corp). All analyses were two sided. A value of P < .05 indicated a significant difference. Continuous variables were expressed as the mean ± SD, and categorical variables were described as a percentage. Characteristics of the study sample were compared by a Student's t test or an ANOVA for continuous variables with normal distribution, the Mann-Whitney U test or Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous variables with a skewed distribution, and the Pearson χ2 test for categorical variables.

We used linear regression analyses to investigate the association of FPG and HbA1c with waist circumference, height, and waist to height ratio in men and women. The model was adjusted for age, rural/urban residence, economic status, LDL, HDL, triglycerides, and systolic BP. Data were expressed as standardized coefficients (β). Because FPG had skewed distribution, it was log transformed.

To analyze the relationship among life stages when exposed to famine, economic status, and risk of diabetes in adulthood, a logistic regression analysis was used. The total subjects as well as separate males and females were analyzed. In different life stages, nonexposed (1963–1974) was the reference. Model 1 included terms for age, sex, rural/urban residence, and economic status. Model 2 included terms for model 1 and waist circumference. Model 3 included terms for model 2 and height. Height may be taken as a growth surrogate of undernutrition exposure (21). Model 4 was a fully adjusted model including all of the covariates in model 3 and metabolic factors (LDL, HDL, triglycerides, and systolic BP). The interaction between life stages when exposed to famine and economic status as well as between rural/urban residence and economic status was tested by adding a multiplicative factor in the logistic regression model.

Sensitivity analyses were performed. In logistic regression models, we used waist to height ratio as a composite measure instead of waist circumference and height. Because the exact start and end date of the famine was not clear, subjects born in 1959 and 1962 were excluded to perform the regression analyses.

Results

General characteristics of participants by glycemic status

The general characteristics of subjects by glycemic status are shown in Table 1. The prevalence of diabetes among adults was 11.4%, and 30.5% of subjects were diagnosed as having central obesity. Of all subjects, 2767 subjects (40.1%) had hypertension. With regard to the lipid profile, 36.1% and 31.0% of subjects had high LDL and high triglycerides, respectively.

Table 1.

General Characteristics of Subjects in SPECT-China (n = 6897)

| Total | Nondiabetes | Diabetes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 6897 | 6112 | 785 |

| Demographics | |||

| Age, y | 53 ± 14 | 52 ± 14 | 60 ± 11a |

| Men, % | 42.6 | 41.8 | 49.2a |

| Current smoker, % | 21.9 | 21.2 | 27.1a |

| Illiteracy, % | 11.7 | 11.1 | 16.5a |

| Anthropometry | |||

| Height, cm | 161.3 ± 8.4 | 161.3 ± 8.4 | 161.2 ± 8.8 |

| Weight, kg | 63.0 ± 11.3 | 62.5 ± 11.1 | 66.7 ± 11.8a |

| WC, cm | 79.1 ± 10.1 | 78.3 ± 9.9 | 85.0 ± 9.8a |

| SBP, mm Hg | 129.7 ± 21.1 | 128.3 ± 20.6 | 140.5 ± 21.8a |

| Laboratory results | |||

| HbA1c, % | 5.4 ± 0.8 | 5.2 ± 0.5 | 6.8 ± 1.5a |

| FPG, mmol/L | 5.64 ± 1.31 | 5.34 ± 0.58 | 7.98 ± 2.48* |

| HOMA-IRb | 1.5 ± 1.9 | 1.3 ± 1.1 | 3.2 ± 4.5a |

| HOMA-β%c | 61.8 ± 60.0 | 63.5 ± 57.5 | 48.3 ± 75.2a |

| Disposition indexd | 50.9 ± 55.6 | 54.8 ± 57.2 | 20.4 ± 26.6a |

| TG, mmol/L | 1.66 ± 1.59 | 1.57 ± 1.37 | 2.33 ± 2.65a |

| LDL, mmol/L | 2.93 ± 0.72 | 2.91 ± 0.71 | 3.04 ± 0.76a |

| HDL, mmol/L | 1.46 ± 0.32 | 1.47 ± 0.32 | 1.40 ± 0.35a |

Abbreviations: DBP, diastolic BP; SBP, systolic BP; TG, triglycerides; WC, waist circumference. There were 364 and 264 missing values for waist circumference and systolic blood pressure, respectively; 14 missing values for insulin; and two missing values for triglycerides, LDL, and HDL. Continuous variables were expressed as the mean ± SD, and categorical variables were described as a percentage. The Mann-Whitney U test and Student's t test were used for continuous variables with skewed distribution and normal distribution.

P < .05, compared with nondiabetes.

HOMA-IR is as follows: (fasting insulin [milliinternational units per liter]) × (FPG [millimoles per liter])/22.5.

HOMA-β% is as follows: (20 × fasting insulin [milliinternational units per liter])/(FPG [millimoles per liter] − 3.5) (percentage).

Disposition index is as follows: HOMA-β%/HOMA-IR.

Sex-specific characteristics of participants by life stages when exposed to famine

The results of variables by life stages when exposed to famine are summarized in Table 2. In men and women, compared with nonexposed (birth year 1963–1974), fetal-exposed and childhood-exposed subjects had significantly higher HbA1c, FPG, and prevalence of diabetes (all P < .05). In men and women, childhood-exposed subjects were significantly shorter than nonexposed (P < .05). In men, the waist circumference and HOMA-IR of fetal and childhood exposed were comparable with those of nonexposed (birth year 1963–1974), but both their HOMA-β% and disposition index were significantly lower (both P < .05). In women, the waist circumference and HOMA-IR of the two groups were significantly higher and the disposition index was lower (all P < .05).

Table 2.

Characteristics of Study Population by Age of Exposure to Famine

| Fetal Exposed (1959–1962) | Childhood Exposed (1949–1958) | Adolescence/Adult Exposed (1921–1948) | Nonexposed (1963–1974) | Nonexposed (1975 and Later) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age in 2014, y | 52–55 | 56–65 | 66–93 | 40–51 | ≤39 |

| Men | |||||

| n | 332 | 809 | 536 | 736 | 528 |

| Current smoker, % | 60.9a | 52.8 | 43.8b | 51.5 | 31.4b |

| Diabetes, % | 18.1a | 18.3a | 16.0a | 10.6 | 2.7b |

| Central obesity, % | 23.5 | 23.9 | 25.6 | 22.6 | 14.0b |

| Height, cm | 168.0 ± 5.9 | 166.2 ± 6.3b | 163.7 ± 6.4b | 168.6 ± 6.3 | 171.8 ± 6.2a |

| Weight, kg | 70.5 ± 10.1 | 68.4 ± 10.3b | 64.2 ± 10.6b | 70.5 ± 10.5 | 71.3 ± 11.3 |

| WC, cm | 83.9 ± 8.9 | 83.6 ± 9.5 | 83.4 ± 9.7 | 82.8 ± 8.8 | 80.1 ± 9.3b |

| SBP, mm Hg | 130.3 ± 20.3a | 135.8 ± 19.4a | 143.1 ± 21.4a | 127.7 ± 17.8 | 122.6 ± 15.6b |

| HbA1c, % | 5.6 ± 0.9a | 5.6 ± 1.0a | 5.6 ± 0.9a | 5.4 ± 0.9 | 5.0 ± 0.7b |

| FPG, mmol/L | 5.86 ± 1.33a | 5.91 ± 1.57a | 5.92 ± 1.33a | 5.54 ± 1.36 | 5.13 ± 1.04b |

| HOMA-IRc | 1.4 ± 1.3 | 1.5 ± 2.2 | 1.4 ± 2.0 | 1.4 ± 1.5 | 1.6 ± 2.3 |

| HOMA-β%d | 49.7 ± 35.0b | 49.7 ± 43.7b | 46.7 ± 57.7b | 61.6 ± 50.8 | 89.2 ± 89.2a |

| Disposition indexe | 44.8 ± 26.6b | 44.2 ± 27.7b | 42.4 ± 31.1b | 55.4 ± 38.8 | 72.8 ± 142.8a |

| TG, mmol/L | 1.99 ± 1.45 | 1.81 ± 1.79b | 1.51 ± 1.28b | 2.22 ± 2.29 | 1.91 ± 2.27b |

| LDL, mmol/L | 3.05 ± 0.76 | 2.98 ± 0.71 | 2.83 ± 0.69b | 2.97 ± 0.71 | 2.82 ± 0.62b |

| HDL, mmol/L | 1.36 ± 0.30 | 1.41 ± 0.34a | 1.44 ± 0.35a | 1.34 ± 0.29 | 1.29 ± 0.25b |

| Women | |||||

| n | 413 | 1102 | 652 | 1072 | 717 |

| Current smoker, % | 1.0 | 2.5a | 6.9a | 0.9 | 1.5 |

| Diabetes, % | 8.7a | 14.8a | 21.3a | 5.0 | 1.0b |

| Central obesity, % | 36.6a | 46.2a | 54.4a | 23.1 | 11.2b |

| Height, cm | 157.1 ± 5.5 | 155.5 ± 5.6b | 152.5 ± 6.0b | 157.8 ± 5.8 | 159.4 ± 5.9a |

| Weight, kg | 60.6 ± 9.4a | 59.8 ± 9.4a | 56.8 ± 9.7b | 58.9 ± 8.9 | 56.2 ± 8.9b |

| WC, cm | 77.4 ± 8.7a | 79.6 ± 9.3a | 81.7 ± 10.2a | 74.1 ± 8.2 | 69.7 ± 8.0b |

| SBP, mm Hg | 129.5 ± 18.1a | 135.1 ± 20.6a | 144.6 ± 21.7a | 121.6 ± 18.5 | 111.6 ± 13.2b |

| HbA1c, % | 5.3 ± 0.8a | 5.5 ± 0.8a | 5.7 ± 0.9a | 5.1 ± 0.6 | 4.9 ± 0.5b |

| FPG, mmol/liter | 5.66 ± 1.31a | 5.86 ± 1.34a | 5.99 ± 1.53a | 5.43 ± 1.03 | 5.11 ± 0.66b |

| HOMA-IRc | 1.7 ± 1.8a | 1.7 ± 2.6a | 1.8 ± 2.3 | 1.4 ± 1.3 | 1.3 ± 0.8 |

| HOMA-β%d | 63.2 ± 46.3 | 59.9 ± 59.6b | 55.6 ± 55.3b | 63.9 ± 55.7 | 76.9 ± 75.0a |

| Disposition indexe | 46.9 ± 24.9b | 43.7 ± 39.7b | 39.9 ± 22.6b | 53.4 ± 31.3 | 67.0 ± 75.5a |

| TG, mmol/L | 1.76 ± 2.17a | 1.68 ± 1.14a | 1.67 ± 1.23a | 1.31 ± 1.11 | 1.07 ± 0.65b |

| LDL, mmol/L | 3.10 ± 0.74a | 3.12 ± 0.77a | 3.14 ± 0.79a | 2.79 ± 0.64 | 2.54 ± 0.57b |

| HDL, mmol/L | 1.52 ± 0.31 | 1.53 ± 0.33 | 1.55 ± 0.33a | 1.52 ± 0.30 | 1.52 ± 0.29 |

Abbreviations: DBP, diastolic BP; SBP, systolic BP; TG, triglycerides; WC, wasit circumference. There were 364 and 264 missing values for waist circumference and systolic BP, respectively; 14 missing values for insulin; and two missing values for triglycerides, LDL, and HDL. Continuous variables were expressed as the mean ± SD, and categorical variables were described as a percentage. The Kruskal-Wallis test and ANOVA were used for continuous variables with skewed distribution and normal distribution and Pearson χ2 test for categorical variables.

P < .05, significantly higher than nonexposed (1963–1974).

P < .05, significantly lower than nonexposed (1963–1974).

HOMA-IR is as follows: (fasting insulin [milliinternational units per liter]) × (FPG [millimoles per liter])/22.5.

HOMA-β% is as follows: (20 × fasting insulin [milliinternational units per liter])/(FPG [millimoles per liter] − 3.5) (percentage).

Disposition index is as follows: HOMA-β%/HOMA-IR.

Characteristics of participants by economic status and rural/urban residence

Table 3 represented the total results of variables by economic status and rural/urban residence. The sex-specific results are summarized in Supplemental Tables 1 and 2. Compared with those in urban areas, subjects in rural areas were 2.5 cm shorter and 2.3 kg lighter but had a greater waist circumference (all P < .05). A similar phenomenon was seen between different economic statuses. Women in rural areas or in areas with high economic status were more likely to be centrally obese (Supplemental Tables 1 and 2).

Table 3.

Characteristics of Subjects by Economic Status or Rural/Urban Area

| Economic Status of Areas (n = 6897) |

Urbanization (n = 6897) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | High | P | Rural | Urban | P | |

| n | 2008 | 4889 | 4073 | 2824 | ||

| Demographics | ||||||

| Age, y | 52 ± 13 | 53 ± 14 | <.05 | 56 ± 13 | 49 ± 13 | <.05 |

| Men, % | 40.6 | 43.5 | <.05 | 41.0 | 45.1 | <.05 |

| Current smoker, % | 20.8 | 22.3 | .20 | 24.4 | 18.3 | <.05 |

| Illiteracy,% | 19.6 | 9.5 | <.05 | 18.3 | 1.2 | <.05 |

| Diabetes, % | 8.8 | 12.4 | <.05 | 12.4 | 9.8 | <.05 |

| Central obesity, % | 27.3 | 29.5 | .14 | 32.1 | 24.2 | <.05 |

| Anthropometry | ||||||

| Height, cm | 159.8 ± 8.2 | 161.8 ± 8.5 | <.05 | 160.2 ± 8.3 | 162.7 ± 8.4 | <.05 |

| Weight, kg | 61.3 ± 11.1 | 63.7 ± 11.3 | <.05 | 62.0 ± 11.0 | 64.3 ± 11.5 | <.05 |

| WC, cm | 78.6 ± 10.2 | 79.3 ± 10.0 | <.05 | 80.0 ± 10.0 | 78.3 ± 10.2 | <.05 |

| SBP, mm Hg | 128.1 ± 22.7 | 130.3 ± 20.4 | <.05 | 132.9 ± 21.7 | 125.2 ± 19.3 | <.05 |

| Laboratory results | ||||||

| HbA1c, % | 5.4 ± 0.8 | 5.4 ± 0.9 | .32 | 5.4 ± 0.9 | 5.3 ± 0.8 | <.05 |

| FPG, mmol/L | 5.41 ± 1.27 | 5.73 ± 1.31 | <.05 | 5.79 ± 1.35 | 5.42 ± 1.20 | <.05 |

| HOMA-IRa | 1.3 ± 1.2 | 1.6 ± 2.2 | <.05 | 1.6 ± 2.0 | 1.4 ± 1.9 | <.05 |

| HOMA-β%b | 59.7 ± 42.0 | 62.6 ± 65.9 | .23 | 58.8 ± 50.8 | 66.0 ± 71.0 | <.05 |

| Disposition indexc | 56.9 ± 31.8 | 48.5 ± 62.7 | <.05 | 45.2 ± 29.7 | 59.2 ± 78.7 | <.05 |

| TG, mmol/L | 1.65 ± 1.68 | 1.66 ± 1.55 | .26 | 1.60 ± 1.46 | 1.73 ± 1.75 | <.05 |

| LDL, mmol/L | 2.94 ± 0.73 | 2.93 ± 0.72 | .33 | 2.88 ± 0.72 | 3.00 ± 0.72 | <.05 |

| HDL, mmol/L | 1.49 ± 0.33 | 1.45 ± 0.32 | <.05 | 1.48 ± 0.32 | 1.44 ± 0.32 | <.05 |

Abbreviations: DBP, diastolic BP; SBP, systolic BP; TG, triglycerides; WC, wasit circumference. Participants living in areas with a high vs low economic status and in rural vs urban areas were, respectively, compared. There were 364 and 264 missing values for waist circumference and systolic BP respectively, 14 missing values for insulin, two missing values for triglycerides, LDL, and HDL. Continuous variables were expressed as the mean ± SD, and categorical variables were described as a percentage. Mann-Whitney U test and Student's t test were used for continuous variables with skewed distribution and normal distribution, and Pearson χ2 test for categorical variables.

HOMA-IR is as follows: (fasting insulin [milliinternational units per liter]) × (FPG [millimoles per liter])/22.5.

HOMA-β% is as follows: (20 × fasting insulin [milliinternational units per liter])/(FPG [millimoles per liter] − 3.5) (percentage).

Disposition index is as follows: HOMA-β%/HOMA-IR.

For those with high economic status, FPG, fasting insulin, and HOMA-IR were significantly greater, whereas the disposition index was significantly lower compared with low economic status (all P < .05). As expected, a significantly greater prevalence of diabetes was observed in areas with high economic status (12.4% vs 8.8%, P < .05). Similar results were observed in men and women separately (Supplemental Table 1).

In rural areas, HbA1c, FPG, fasting insulin, and HOMA-IR were significantly greater compared with urban areas (all P < .05). HOMA-β% and the disposition index were also significantly lower in rural areas (both P < .05). Rural areas had a greater prevalence of diabetes (12.4% vs 9.8%, P < .05). Sex-specific results showed similar results (Supplemental Table 2).

Prevalence of diabetes by life stages, economic status, and rural/urban residence

The prevalence of diabetes by different life stages when exposed to famine is shown in Supplemental Figure 1. Compared with low economic status, subjects in areas with high economic status had higher prevalence of diabetes in the childhood-exposed (17.1% vs 12.9%, P < .05) and adolescence/adult-exposed groups (20.6% vs 14.8%, P < .05). In rural vs urban areas, the prevalence of diabetes was only significantly higher among adolescent/adult-exposed subjects (17% vs 25.7%, P < .05). In rural areas, the prevalence reached a plateau in childhood-exposed subjects.

Association of famine exposure and economic status with diabetes

Table 4 provides the association of famine exposure and economic status with diabetes. In fetal- and childhood-exposed subjects, the odds ratio (OR) of diabetes was 1.53 (95% confidence interval [CI] 1.09–2.14; P < .05) and 1.82 (95% CI 1.21–2.73; P < .05), significantly greater than that in the nonexposed group (birth year 1963–1974) after adjusting for age and sex (Table 4, model 1). Adjusting for waist circumference and height did not weaken this association (Table 4, model 3). Further adjustment for other metabolic factors did not attenuate the association either (Table 4, model 4). In rural areas and areas with high economic status, the OR of diabetes was 1.22 (95% CI 1.02–1.46; P < .05) and 1.46 (95% CI 1.20–1.78; P < .05), significantly higher than in urban areas and areas with low economic status, respectively (Table 4, model 1). In the fully adjusted model, the association between economic status and diabetes was still significant (Table 4, model 4). No interaction was found between age classification when exposure to famine and economic status or between rural/urban residence and economic status (all P > .05). Sex-specific results were also observed. During early life, fetal-exposed men (OR 1.64, 95% CI 1.04–2.59; P < .05) and childhood-exposed women (OR 2.81, 95% CI 1.59–4.97; P < .05) had a significantly higher risk of diabetes than nonexposed men or women (birth year 1963–1974).

Table 4.

Association of Famine Exposure and Economic Status With Diabetes

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | ||||

| Life stage when exposed to famine (birth year) | ||||

| Nonexposed (1975 and later) | 0.28 (0.16, 0.50)a | 0.28 (0.16, 0.50)a | 0.28 (0.16, 0.50)a | 0.25 (0.13, 0.45)a |

| Fetal exposed (1959–1962) | 1.53 (1.09, 2.14)a | 1.57 (1.10, 2.24)a | 1.59 (1.11, 2.26)a | 1.63 (1.13, 2.35)a |

| Childhood exposed (1949–1958) | 1.82 (1.21, 2.73)a | 1.93 (1.25, 2.96)a | 1.95 (1.27, 3.00)a | 1.90 (1.22, 2.95)a |

| Adolescence/adult exposed (1921–1948) | 1.58 (0.82, 3.01) | 1.91 (0.96, 3.81) | 1.93 (0.96, 3.85) | 1.95 (0.95, 3.98) |

| Nonexposed (1963–1974) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) |

| Economic status of areas | ||||

| High | 1.46 (1.20, 1.78)a | 1.52 (1.23, 1.87)a | 1.51 (1.22, 1.87)a | 1.56 (1.25, 1.95)a |

| Low | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) |

| Urbanization | ||||

| Rural area | 1.22 (1.02, 1.46)a | 1.20 (1.00, 1.45) | 1.21 (1.01, 1.47)a | 1.22 (1.00, 1.48) |

| Urban area | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) |

| Men | ||||

| Life stage when exposed to famine (birth year) | ||||

| Nonexposed (1975 and later) | 0.30 (0.14, 0.63)a | 0.30 (0.14, 0.66)a | 0.31 (0.14, 0.67)* | 0.30 (0.14, 0.67)a |

| Fetal exposed (1959–1962) | 1.64 (1.04, 2.59)a | 1.62 (1.00, 2.63)a | 1.65 (1.02, 2.67)a | 1.74 (1.06, 2.84)a |

| Childhood exposed (1949–1958) | 1.34 (0.75, 2.41) | 1.41 (0.76, 2.62) | 1.44 (0.77, 2.68) | 1.40 (0.74, 2.66) |

| Adolescence/adult exposed (1921–1948) | 0.87 (0.34, 2.24) | 1.04 (0.38, 2.87) | 1.06 (0.38, 2.93) | 1.00 (0.35, 2.85) |

| Nonexposed (1963–1974) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) |

| Economic status of areas | ||||

| High | 1.38 (1.04, 1.84)a | 1.33 (0.98, 1.80) | 1.28 (0.95, 1.74) | 1.32 (0.96, 1.81) |

| Low | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) |

| Urbanization | ||||

| Rural area | 1.07 (0.83, 1.37) | 1.17 (0.90, 1.52) | 1.03 (1.00, 1.07) | 1.20 (0.90, 1.59) |

| Urban area | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) |

| Women | ||||

| Life stage when exposed to famine (birth year) | ||||

| Nonexposed (1975 and later) | 0.22 (0.09, 0.54)a | 0.24 (0.10, 0.61)a | 0.24 (0.10, 0.60)a | 0.22 (0.08, 0.58)a |

| Fetal exposed (1959–1962) | 1.47 (0.88, 2.44) | 1.58 (0.92, 2.69) | 1.57 (0.92, 2.69) | 1.51 (0.87, 2.62) |

| Childhood exposed (1949–1958) | 2.81 (1.59, 4.97)a | 2.85 (1.55, 5.23)a | 2.88 (1.57, 5.30)a | 2.61 (1.38, 4.92)a |

| Adolescence/adult exposed (1921–1948) | 3.34 (1.37, 8.19)a | 3.70 (1.43, 9.59)a | 3.71 (1.42, 9.69)a | 3.71 (1.37, 10.09)a |

| Nonexposed (1963–1974) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) |

| Economic status of areas | ||||

| High | 1.59 (1.20, 2.09)a | 1.79 (1.32, 2.41)a | 1.82 (1.35, 2.47)a | 1.89 (1.37, 2.60)a |

| Low | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) |

| Urbanization | ||||

| Rural area | 1.43 (1.11, 1.84)a | 1.23 (0.94, 1.62) | 1.23 (0.94, 1.62) | 1.22 (0.91, 1.63) |

| Urban area | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) |

Data were ORs (95% CI), which were calculated by logistic regression models. Model 1 included terms for age, sex (only in total), rural/urban residence, and economic status of areas. Model 2 included terms for model 1 and waist circumference. Model 3 included terms for model 2 and height. Model 4 was a fully adjusted model including all covariates in model 3 and metabolic factors (LDL, HDL, triglycerides, and systolic BP). No interaction was found between life stages and economic status or between rural/urban residence and economic status.

P < .05.

Sensitivity analyses

We explored waist to height ratio as a composite measure instead of waist circumference and height. The association did not change between diabetes and fetal-exposed subjects (OR 1.60, 95% CI 1.12–2.27; P < .05) or childhood-exposed subjects (OR 1.91, 95% CI 1.24–2.94; P < .05) (Supplemental Table 3). We also excluded subjects born in 1959 and 1962 to perform the regression analyses. The significance of fetal exposure to famine still existed without making this change (OR 2.00, 95% CI 1.28–3.12; P < .05) (Supplemental Table 4).

Discussion

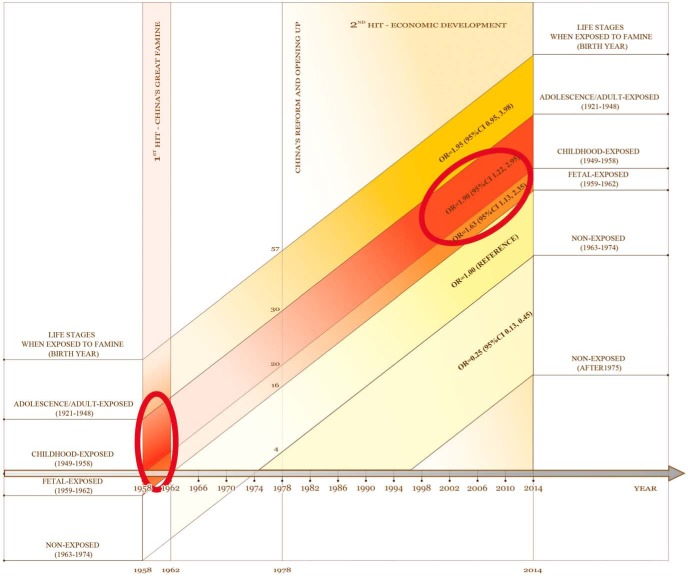

In this study, we found that there was a significant association between diabetes and famine exposure in utero (male) and during childhood (female). Living in areas with high economic status in adulthood is further associated with an increased risk of diabetes. Thus, our findings (undernutrition followed by overnutrition) (Figure 2) may partly explain the worrisome increased diabetes prevalence in China. This study also supports the developmental origins of health and disease hypothesis (22, 23) and suggests the adverse effects of undernutrition may extend beyond the first 1000 days.

Figure 2.

Association of famine exposure and economic status with diabetes. The horizontal axis is the calendar year from 1958 to 2014, and the vertical axis is the residents' age when the events occurred. In China, people aged 52 years or older experienced both of the two events. The first event was China's Great Famine from 1958 to 1962, which mainly affected people exposed as a fetus or during childhood (small ellipse). The second event was the rapid economic development after reform and opening up in 1978. As presented, people exposed to famine in utero and during childhood and economic development in adulthood had a significantly higher risk of diabetes after adjusting for age, sex, waist circumference, height, HDL, LDL, triglycerides, and systolic BP (large ellipse).

There are some potential mechanisms to explain the associations between famine exposure and diabetes in later life. Previous studies have demonstrated that permanently altered hypothalamic gene expression may be induced by undernutrition during the pre- and postnatal period, which is a key step in the development of endocrine and metabolic diseases (24, 25). Additionally, impaired glucose tolerance in adult life after prenatal exposure to famine may be mediated through a defect in insulin secretion (26). Moreover, epigenetic modulation by early life malnutrition may promote an adverse metabolic phenotype in later life (27). Because of the importance of this issue to human health, an even better understanding of this phenomenon will require further study.

Li et al (8) did not find a significant association between famine exposure at an early age and diabetes. The study by Li et al was conducted in 2002 when the diabetes prevalence was relatively low. In contrast, our study was performed in 2014, with a much higher prevalence of diabetes, perhaps allowing these associations to be revealed. We observed the sex-specific results of famine, which influenced men in utero and women in childhood. What underlies this gender dichotomy with regard to famine? Men may be more vulnerable to malnutrition during pregnancy. In a rat model, fetal protein deficiency led to insulin resistance and higher lipids in male offspring (28). In young adults with very low birth weight, the male sex was a significant independent risk factor for hyperglycemia (29). After birth, girls may suffer more from famine at that time. In traditional Chinese values, sons are considered more important than daughters (the son preference). When children were exposed to famine, the average welfare of the surviving girls is much worse than that of boys during childhood. Thus, the consequence of preferring sons may worsen women's health outcomes including glucose and lipid metabolism in later life (30). We also observed that the association between famine exposure and diabetes extended into adolescence and young adulthood in women. We suspected that male preference and mental stress might be involved with this association (31). Studies in this life period are limited, requiring further exploration.

Rural residence raised the diabetes risk in our study, although this association was attenuated by metabolic factors. Li et al (8) reported a stronger famine effect on diabetes risk in the severely affected famine areas. Van Abeelen et al (10) also demonstrated that famine severity increased the risk of diabetes in a significant dose-dependent manner in adult life, from unexposed to severely exposed subjects. In China, the prevalence of prediabetes in rural areas is higher than in urban areas (2), and more severe famine in rural areas may have played a role in this phenomenon. Rural residence might also be related to the socioeconomic development. For example, long-term malnutrition at an early age might affect brain development and intellectual capacity in school-age children (32). In our study, the illiterate adults are more likely to live in rural areas. In China, the distribution of educational resources is unequal in rural and urban areas, and most students from rural areas are shunted into lower-quality colleges (33).

After China's reform and opening up, the GDP per capita soared from 28 US dollars in 1978 to 6807 US dollars in 2013. Whereas this rapid economic development has ameliorated undernutrition and elevated living conditions, it may have also created its own health problems. Along with industrialization, urbanization, and lifestyle changes induced by economic development, diabetes has attained epidemic proportions in the Chinese population. In a recent national investigation, the prevalence of diabetes was 14.3% in developed areas and about 10% in intermediately developed and underdeveloped areas (2). In our study, the prevalence of diabetes was also significantly higher in participants living in areas with high economic status.

Our study has some strengths. For the first time, we found that exposure to famine during the fetal period (men) and childhood (women) was associated with diabetes in Chinese people. Second, anthropometric measurements and questionnaires were all completed by the same trained research group with strong quality control. Third, our study enrolled men and women (age18–93 y) living in rural and urban areas. Previous studies did not have such full-scale recruitment (8, 10).

There were also some limitations to our study. First, we enrolled residents living in their current residence for 6 months or longer. We assumed that they were born in the same province or area and did not transfer from other areas. The fact is only 2.68% of the rural population lived in provinces other than their birthplaces according to a national report (8). Although population mobility is increasing alongside economic development in China, permanent residency acquisition has strict and advanced requirements and must be approved by the Chinese government, especially in the metropolises that we chose in this study. Second, the exact start and end date of the famine was not clear. However, even though subjects born in 1959 and 1962 were excluded, the association still existed (Supplemental Table 4). Finally, this is an observational study, and different age groups were taken into the analysis but not the famine and nonfamine exposure groups with comparable age. However, this has to be an observational study. Because the Chinese great famine swept across all the areas in China (19), we could find no place where people did not suffer from famine. Thus, the reality determines the nature and method of the study. It is still a precious chance for us to look into the long-term effect of undernutrition in early life.

In conclusion, the rapid increase in the prevalence of diabetes in middle-aged and elderly people in China may be associated with the combination of exposure to famine in utero and childhood and high economic status in adulthood. Our findings (undernutrition followed by overnutrition) may partly explain the booming diabetes phenomenon in China.

Acknowledgments

We thank Weiping Tu, Bin Li, and Ling Hu for helping organize this investigation. We also thank all the team members and participants from Shanghai, Zhejiang, and Jiangxi Province in the SPECT-China study.

Language editing was performed by a distinguished professional service (http://webshop.elsevier.com/).

The SPECT-China study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grants 81270885 and 81070677); Shanghai Jiaotong University School of Medicine (2014); the Ministry of Science and Technology in China (Grant 2012CB524906), and the Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality (Grant 14495810700).

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- BP

- blood pressure

- CI

- confidence interval

- FPG

- fasting plasma glucose

- GDP

- gross domestic product

- HbA1c

- hemoglobin A1c

- HDL

- high-density lipoprotein

- HOMA-β

- homeostasis model of β-cell function

- HOMA-IR

- homeostasis model assessment index of insulin resistance

- LDL

- low-density lipoprotein

- OR

- odds ratio

- SPECT-China

- Survey on Prevalence in East China for Metabolic Diseases and Risk Factors.

References

- 1. International Diabetes Federation. IDF Diabetes Atlas. 6th ed (article online); 2013. http://www.idf.org/diabetesatlas Accessed October 18, 2014.

- 2. Xu Y, Wang L, He J, et al. 2010 China Noncommunicable Disease Surveillance Group. Prevalence and control of diabetes in Chinese adults. JAMA 2013;310:948–959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Yisahak SF, Beagley J, Hambleton IR, Narayan KM. IDF Diabetes Atlas: diabetes in North America and the Caribbean: an update. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2014;103:223–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Barker DJ, Osmond C, Kajantie E, Eriksson JG. Growth and chronic disease: findings in the Helsinki Birth Cohort. Ann Hum Biol. 2009;36:445–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. McMillen IC, Robinson JS. Developmental origins of the metabolic syndrome: prediction, plasticity, and programming. Physiol Rev. 2005;85:571–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ravelli AC, van der Meulen JH, Michels RP, et al. Glucose tolerance in adults after prenatal exposure to famine. Lancet. 1998;351:173–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. de Rooij SR, Painter RC, Roseboom TJ, et al. Glucose tolerance at age 58 and the decline of glucose tolerance in comparison with age 50 in people prenatally exposed to the Dutch famine. Diabetologia. 2006;49:637–643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Li Y, He Y, Qi L, et al. Exposure to the Chinese famine in early life and the risk of hyperglycemia and type 2 diabetes in adulthood. Diabetes. 2010;59:2400–2406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yajnik CS. Early life origins of insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes in India and other Asian countries. J Nutr. 2004;134:205–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. van Abeelen AF, Elias SG, Bossuyt PM, et al. Famine exposure in the young and the risk of type 2 diabetes in adulthood. Diabetes. 2012;61:2255–2260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Khoroshinina LP, Zhavoronkova NV. Starving in childhood and diabetes mellitus in elderly age. Adv Gerontol. 2008;21:684–687. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Portrait F, Teeuwiszen E, Deeg D. Early life undernutrition and chronic diseases at older ages: the effects of the Dutch famine on cardiovascular diseases and diabetes. Soc Sci Med. 2011;73:711–718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ravallion M. Growth, inequality and poverty: looking beyond averages. World Dev. 2001;29:1803–1815. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Victora CG, Adair L, Fall C, et al. Maternal and Child Undernutrition Study Group. Maternal and child undernutrition: consequences for adult health and human capital. Lancet 2008;371:340–357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Low S, Chin MC, Ma S, Heng D, Deurenberg-Yap M. Rationale for redefining obesity in Asians. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2009;38:66–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Matthews DR, Hosker JP, Rudenski AS, Naylor BA, Treacher DF, Turner RC. Homeostasis model assessment: insulin resistance and β-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia. 1985;28:412–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Matsuda M. Measuring and estimating insulin resistance in clinical and research settings. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2010;20:79–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Luo Z, Mu R, Zhang X. Famine and overweight in China. Rev Agricultural Econ. 2006;28:296–304. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lin JY, Yang DT. Food availability, entitlements and the Chinese famine of 1959–61. Econ J. 2000;460:136–158. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bogin B. Patterns of Human Growth. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chen Y, Zhou LA. The long-term health and economic consequences of the 1959–1961 famine in China. J Health Econ. 2007;26:659–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gillman MW, Barker D, Bier D, et al. Meeting report on the 3rd International Congress on Developmental Origins of Health and Disease (DOHaD). Pediatr Res. 2007;61:625–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Uauy R, Kain J, Corvalan C. How can the Developmental Origins of Health and Disease (DOHaD) hypothesis contribute to improving health in developing countries? Am J Clin Nutr 2011;94:1759S–1764S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kongsted AH, Husted SV, Thygesen MP, et al. Pre- and postnatal nutrition in sheep affects β-cell secretion and hypothalamic control. J Endocrinol. 2013;219:159–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Orozco-Solís R, Matos RJ, Guzmán-Quevedo O, et al. Nutritional programming in the rat is linked to long-lasting changes in nutrient sensing and energy homeostasis in the hypothalamus. PLoS One. 2010;5:e13537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. de Rooij SR, Painter RC, Phillips DI, et al. Impaired insulin secretion after prenatal exposure to the Dutch famine. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:1897–1901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tobi EW, Goeman JJ, Monajemi R, et al. DNA methylation signatures link prenatal famine exposure to growth and metabolism. Nat Commun. 2014;5:5592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zambrano E, Bautista CJ, Deás M, et al. A low maternal protein diet during pregnancy and lactation has sex- and window of exposure-specific effects on offspring growth and food intake, glucose metabolism and serum leptin in the rat. J Physiol. 2006;571:221–230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sato R, Watanabe H, Shirai K, et al. A cross-sectional study of glucose regulation in young adults with very low birth weight: impact of male gender on hyperglycaemia. BMJ Open. 2012;2:e000327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mu R, Zhang X. Why does the Great Chinese Famine affect the male and female survivors differently? Mortality selection versus son preference. Econ Hum Biol. 2011;9:92–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kelly SJ, Ismail M. Stress and type 2 diabetes: a review of how stress contributes to the development of type 2 diabetes. Annu Rev Public Health. 2015;36:441–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ivanovic DM, Leiva BP, Perez HT, et al. Long-term effects of severe undernutrition during the first year of life on brain development and learning in Chilean high-school graduates. Nutrition. 2000;16:1056–1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wang Q. Rural students are being left behind in China. Nature. 2014;510:445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]