Abstract

BACKGROUND/OBJECTIVES

To encourage healthier food choices for children in fast-food restaurants, many initiatives have been proposed. This study aimed to examine the effect of disclosing nutritional information on parents' meal choices for their children at fast-food restaurants in South Korea.

SUBJECTS/METHODS

An online experimental survey using a menu board was conducted with 242 parents of children aged 2-12 years who dined with them at fast-food restaurants at least once a month. Participants were classified into two groups: the low-calorie group (n = 41) who chose at least one of the lowest calorie meals in each menu category, and the high-calorie group (n = 201) who did not. The attributes including perceived empowerment, use of provided nutritional information, and perceived difficulties were compared between the two groups.

RESULTS

The low-calorie group perceived significantly higher empowerment with the nutritional information provided than did the high-calorie group (P = 0.020). Additionally, the low-calorie group was more interested in nutrition labeling (P < 0.001) and considered the nutritional value of menus when selecting restaurants for their children more than did the high-calorie group (P = 0.017). The low-calorie group used the nutritional information provided when choosing meals for their children significantly more than did the high-calorie group (P < 0.001), but the high-calorie group had greater difficulty using the nutritional information provided (P = 0.012).

CONCLUSIONS

The results suggest that improving the empowerment of parents using nutritional information could be a strategy for promoting healthier parental food choices for their children at fast-food restaurants.

Keywords: Fast-food restaurant, nutritional labeling, children, parents, meal choice

INTRODUCTION

As obesity has come to be considered a serious issue in children's health, public interest has increased in children's food consumption at fast-food restaurants. Fast foods are well known as being higher-calorie and less-nutritive foods [1,2] and fast-food consumption has been linked to higher caloric intake and greater risk for obesity [3,4]. Consequently, the fast-food industry is frequently blamed as one of the major causes of the childhood obesity problem [5]. As in most countries worldwide, concern has increased in South Korea about the high prevalence of childhood obesity. The prevalence of obesity among South Korean children and adolescents has increased significantly from 5.8% in 1997 to 9.6% in 2012 [6].

To encourage healthier food choices for children in fast-food restaurants, many initiatives have been proposed. Mandatory nutritional information disclosure by fast-food restaurants is one of these initiatives. In the United States, New York City was the first to implement this legislation, in July 2008. Although the proposed regulatory details differ across localities, the statutes typically require restaurants with a certain number of locations in a city or state to present the caloric content of their menu items [7]. In South Korea, the Special Act on Safety Management of Children's Dietary Life was signed into law in March 2008. This Act includes the provision of calorie and nutrient (sugars, protein, saturated fat, and sodium) information on menus at fast-food restaurants. Any restaurant chain with 100 or more units nationally is required to provide nutritional information on their menus and menu boards [8].

Many studies have examined the effectiveness of mandated disclosure of nutritional information. However, the findings of these studies have been mixed. Some studies found a decrease in calories ordered by participants when exposed to calorie information [9,10,11,12]. There were also studies showing no significant difference in consumers' calories ordered between menulabeling conditions [13,14,15].

These mixed findings imply that nutritional information disclosure alone may not necessarily lead to healthful choices. Boles et al. [16] suggested that researchers should consider the potential factors interplaying with disclosed nutritional information on affecting consumers' food choices when attempting to clarify the relationship between nutritional information disclosure and consumers' food choices. Previous studies reported that the effect of nutritional information disclosure on consumers' food choices interplayed with their attributes and perceptions such as nutrition knowledge [17,18], health awareness [19,20], and perceived healthiness of restaurants [21,22].

The perceived consumer empowerment from nutritional information disclosure is one of the potential factors influencing consumers' choices. The concept of empowerment has been widely used in the behavioral and social sciences. Customers feel increased self-determination and empowerment in their decision making when they are provided with information about their choices [23,24,25]. Empowered customers are more likely to have feelings of responsibility for their choice and satisfaction with what they chose [26]. Sawhney et al. [27] mentioned that empowered customers might be more willing to buy products through a closer relationship with the underlying products. However, relatively few studies researched the concept of consumer empowerment in food-service settings; they assumed nutritional information was a tool of empowerment because it is additional information [28,29]. More specifically, few studies examined the underlying relationship between consumers' perceived empowerment after exposure to nutritional information and their food choices at fast-food restaurants.

Parents influence their children's eating behaviors from birth [30,31]. Even though children are able to choose foods for themselves, their caregivers still influence their food selection by helping children choose foods or selecting foods directly for children to eat. In addition, when eating at restaurants, children are usually accompanied by their parents who have the power to decide where and what their children eat. Therefore, an understanding of parental decisions about food selection for their children is important. Nevertheless, few studies have investigated parental influence on their children's meal choices at fast-food restaurants, including how parents respond to mandatory nutrition labeling.

Therefore, this study was designed to examine whether increased perceived empowerment and other attributes would correlate with the effect of nutritional information disclosure on food choices. In particular, we focused on parents' reactions rather than children's by considering the substantial role of parents in the meal choices of their children.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

Participants and data collection

Participants were recruited from consumer panels of a research company in South Korea. Participants were required to meet two criteria to participate in the survey: they must be (a) one of parents (father or mother) of children who were between 3 and 12 years old; and (b) parents who dined with children at fast-food restaurants at least once a month in the past 3 months. A Web link in the survey directed participants who met the criteria to the experimental condition, which included a menu board. Participants were asked to select a meal for their children from the menu board (one main dish, one side dish, and one beverage) and to respond to a series of questions. After excluding incomplete cases, the answers of 242 participants were analyzed. The survey was conducted from March 31, 2014, to April 14, 2014. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Myongji University (MJU-2014-03-001-01).

Menu board development

Using fixed prices, the menu board was developed and comprised five items for each menu category of main dish, side dish, and beverage, with 15 items in total. The menu board included items for children that are typically sold at fast-food restaurants (Lotteria, McDonald, Burger King, Popeyes, and KFC) in South Korea, such as hamburgers, French fries, and soft drinks. The menus presented nutritional information for all items per portion: calorie (kcal), sugar (g), protein (g), saturated fat (g), and sodium (mg). This nutritional information was obtained from the Web sites of the fast-food restaurant chains. These information items are required to be presented on children's menus at restaurants with more than 100 units in South Korea [8].

Measures

The questionnaire included questions related to general characteristics (sex, age, education level, occupation type, and monthly household income), perceived consumer empowerment with nutritional information provided, influence over their children's menu choices, nutrition-labeling awareness, considering potential factors when choosing restaurants for children, use of nutritional information provided, and perceived difficulties in using the nutritional information provided. In this study, we defined empowerment as parents' increased sense of control over their menu selection using nutritional information. Perceived empowerment was measured by three items including "I have control over selecting menu items for my child at this restaurant" (Cronbach's α = 0.68). To measure influence over their children's menu choices at fast-food restaurants, one item was used, "I have influence on my child's menu choice at fast-food restaurants."

Ten items were used to measure nutrition-labeling awareness, including "I am knowledgeable about nutritional labels" and "I am interested in nutrition labels provided by the fast-food restaurant" (Cronbach's α = 0.92). Potential factors to consider when choosing restaurants for children included flavor, quantity, price, nutritional value, convenience, store ambience, and children's preference.

To measure the use of nutritional information provided when selecting menus in the current study, three items were used (Cronbach's α = 0.85), including "I used the nutritional information provided when selecting meals." The perceived difficulties in using the nutritional information provided were measured by one item, "The nutritional information provided is complex and difficult to understand."

All measurement items were modified from reference scales according to the context of the current study and measured on a seven-point Likert-type scale (1 = strongly disagree; 7 = strongly agree). The total calories selected were calculated by summing the calorie values for all food and beverage items selected by each participant.

Statistical analysis

To test the differences in perceptions and attributes between participants who selected low-calorie menus and those who did not, we divided the participants into two groups. Participants who chose at least one of the lowest calorie meals in each menu category (main dish, side dish, and beverage) were classified into the low-calorie group. Those who did not select the lowest calorie meals at all were classified into the high-calorie group.

All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS 18.0 for Windows. Variables were compared between the two groups using the χ2 test and Student's t-test. The results were presented as frequency and percentage or average and standard deviation.

RESULTS

General characteristics of participants

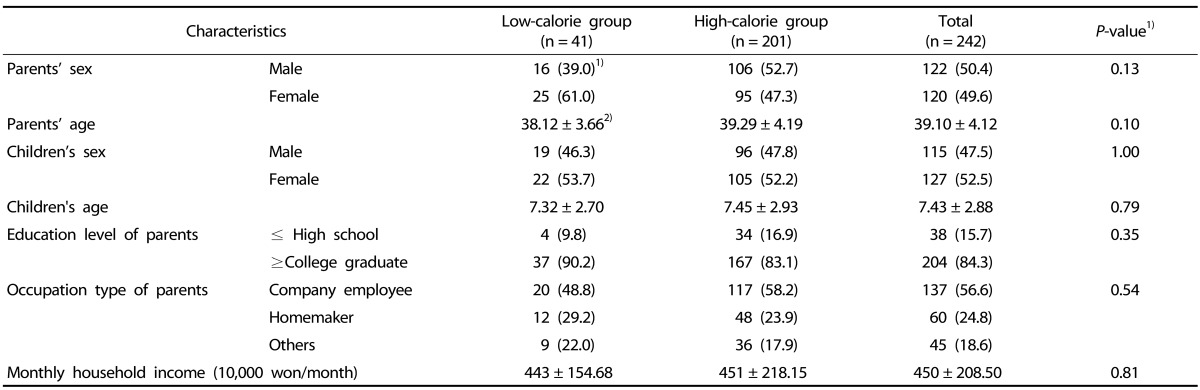

The general characteristics of the subjects are shown in Table 1. Among a total of 242 participants, 41 selected more than one of the lowest calorie meals in each menu category and were classified as the low-calorie group. There was no significant difference in the sex and average age of respondents and their children between the two groups. The average age of parents was 39.0 years. Half of the parents were male (50.4%) and half were female (49.6%). The average age of children was 7.4 years and just over half were female (52.5%).

Table 1. General characteristics of participants (n (%) or mean ± SD).

1)P-value by χ2 test or student's t-test

There were no significant differences in education levels, kinds of jobs, and monthly household income between the two groups. The majority of respondents had an educational level higher or equal to a college degree (84%), and their occupational status was widely distributed from company employee (57%) to homemaker (25%).

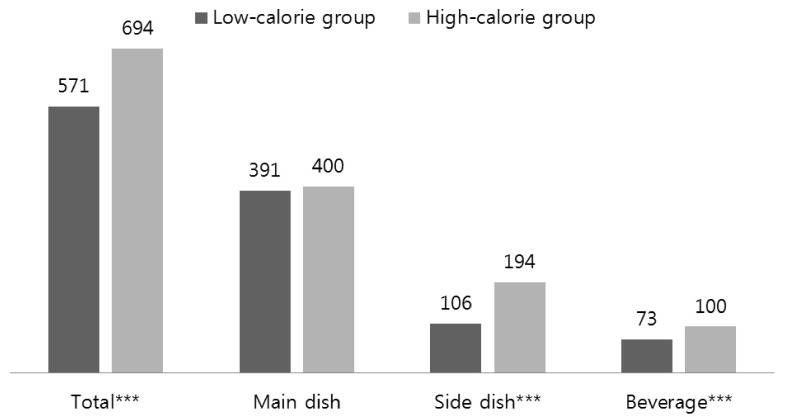

Calories selected

The calories of meals selected by the two groups are presented in Fig. 1. The total amount of calories selected by the low-calorie group was 571 kcal, which was significantly lower than in the high-calorie group (694 kcal; P < 0.001). Participants in the low-calorie group selected an average of 123 kcal fewer calories for their children than did those in the high-calorie group. We found the same tendencies in other menu categories. The low-calorie group selected very significantly lower calorie side dishes (P < 0.001) and beverages (P < 0.001). However, there was no significant difference in the calories of main dishes selected between the two groups.

Fig. 1. Calories selected (kcal). *** P < 0.001.

Perceived empowerment and other attributes

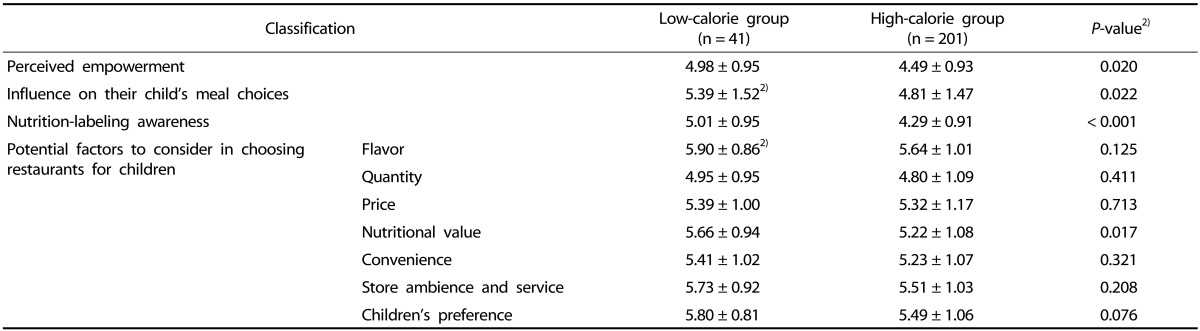

Table 2 shows the perceived empowerment of parents using the nutritional information provided and other participant attributes, including their influence over their children's meal choices, nutrition-labeling awareness, and considering potential factors when choosing restaurants for their children. Participants in the low-calorie group perceived significantly higher empowerment from using nutritional information than those in the high-calorie group (P = 0.020). Parents in the low-calorie group also reported that they have stronger influence on their children's meal choices at fast-food restaurants than those in the high-calorie group (P = 0.022).

Table 2. Perceived empowerment and other attributes (mean ± SD1)).

1)Scale of 1 = strongly disagree; 7 = strongly agree

2)P-value by Student's t-test

In addition, participants in the low-calorie group were more interested in the nutrition labeling provided in fast-food restaurants and they were more knowledgeable about nutrition than participants in the high-calorie group (P < 0.001). Among various potential factors to consider when selecting restaurants for their children, only "nutritional value" showed a significant difference between the two groups (P = 0.017), with 5.66 points in the low-calorie group and 5.22 points in the high-calorie group.

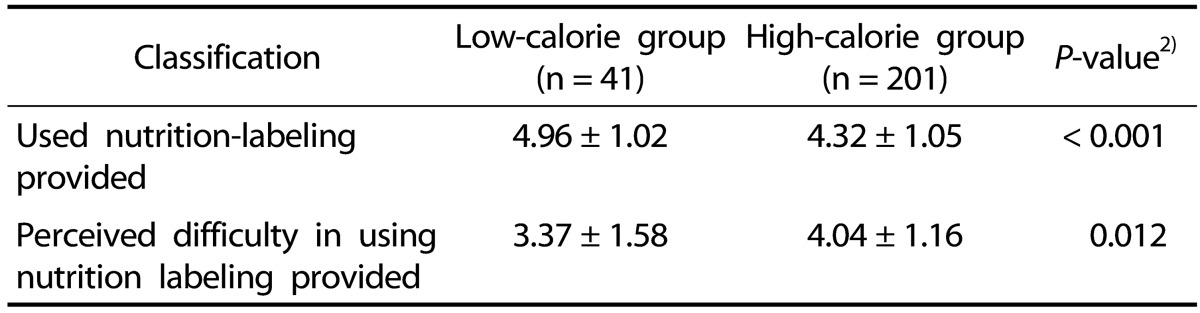

Use of provided nutritional information and perceived difficulties

Table 3 presents parents' use of nutritional information provided on the menu board in the current study when choosing meals for their children and their perceived difficulties in using the information. Participants in the low-calorie group considered and used nutritional information when choosing meals for their children significantly more than participants in the high-calorie group did (P < 0.001), with 4.96 points in the low-calorie group compared with 4.32 points in the high-calorie group. However, the high-calorie group had greater difficulty using the nutritional information provided than did the low-calorie group (P = 0.012).

Table 3. Use of nutrition labeling and perceived difficulty (mean ± SD1)).

1)Scale of 1 = strongly disagree; 7 = strongly agree

2)P-value by student's t-test

DISCUSSION

This study examined parents' reactions to nutritional information on children's menus at fast-food restaurants. Participants in the low-calorie group who chose at least one of the lowest calorie meals in each three menu category (main dish, side dish, and beverage) selected averagely 123 kcal fewer than participants in the high-calorie group who did not choose any of the lowest calorie meals.

Previous studies have persistently pointed out the necessity to understand better the potential factors that affect the relationship between nutritional information disclosure and consumer food choices [16,22,28,32]. In the current study, parents in the low-calorie group perceived significantly higher empowerment using the nutritional information provided than did parents in the high-calorie group. These results suggest that consumer empowerment could be a considerable factor that interplays with nutritional information disclosure to influence food choices. In other words, parents who feel empowered when exposed to nutritional information are enabled to make a reasoned choice by considering the advantages and disadvantages of their food selections and ensure healthier food consumption by their children.

It is well known that providing information facilitates empowerment in the decision-making process [23] Therefore, when consumers are choosing their meal in a restaurant, providing additional nutritional information can be a tool of empowerment for consumers. A report from the White House Task Force on Childhood Obesity also stated that nutrition labeling is an important tool for empowering parents and caregivers [33]. However, our study showed that providing nutritional information by itself would not be enough to promote healthier meal choices of parents for their children. Not a few studies have also reported that nutritional information disclosure alone may not necessarily lead to healthful choices [13,14,15]. Other additional strategies along with nutritional information disclosure are needed to encourage healthier food choices and the present study showed that increasing perceived empowerment when exposed to nutritional information could be one of them. As Kent [34] pointed out, the object of empowerment is not simply to convey new bits of information, but to support people in making their own analyses so that they themselves can decide what is good for them. Kent [34] suggested nutrition education as an important instrument of empowerment. Thus, nutritional information disclosure in fast-food restaurants needs to be accompanied by appropriate nutrition education to enhance perceived empowerment when choosing menus.

In our study, the parents in the low-calorie group showed more positive attributes relating to food choice behaviors. They are more interested in nutrition labeling, have more knowledge about nutrition, and consider nutrition more when choosing meals at restaurants. In addition, when choosing restaurants for their children, nutritional value was the more important potential factor for them. They also have a stronger influence on their children's meal choices at fast-food restaurants than do their counterparts in the high-calorie group. Previous studies showed that the dietary behavior and knowledge of participants who read nutrition labeling were more positive than those who did not [35,36]. Other studies also reported that the more customers consider nutrition labels and the more they are interested in nutrition, the more frequently they choose the lower calorie and healthier food [32,37,38].

Moreover, the low-calorie group experienced less difficulty in using the nutritional information provided in the current study to choose meals for their children. The use of nutritional information has relevance to understanding nutrition labeling. People who considered nutrition labeling felt that the nutritional information was reliable and useful when selecting meals [39]. However, people who did not consider nutrition labeling regarded nutritional information as being complex and difficult to understand [40,41]. These results support the necessity of nutrition education to cultivate parental nutritional knowledge to maximize the effectiveness of the mandatory nutritional information disclosure at fast-food restaurants.

On the other hand, in South Korea, menu-labeling legislation requires the presentation of calorie and nutrient information in a numerical format only [8]. A previous study examining the influence of different nutrition labeling formats on the calories ordered by participants found that there was no significant difference in calories ordered between the calorie-label and no calorie-label groups, which suggests that calorie labels need to be in an easily understood format to increase the effectiveness of menu labeling [42]. Many other studies have tried to find the most effective menu-labeling format to lead customers to choose healthier items [13,43]. The results of the current study indirectly suggested that nutritional information needs to be effectively provided using a simple design to consumers to enhance their understanding of nutritional information so they can easily select a low-calorie meal.

In conclusion, parents having a high level of perceived empowerment by actively using the nutritional information provided at fast-food restaurants were more likely to select lower calorie meals for their children. Therefore, to promote healthier parental food choices at fast-food restaurants, a need exists for nutrition education to increase the perception of empowerment of parents when exposed to nutritional information by enhancing their nutritional knowledge and enable them to consider the provided nutritional information. In addition, a more effective and simple nutritional information format needs to be created to help parents to choose healthier food for their children.

There are some limitations in our study. First, as this study was based on a scenario-based experimental design and online survey, it did not reflect the real-world situation. Future research needs to conduct field studies to examine how nutritional information may influence parents' actual food choices and perceptions at fast-food restaurants in real-world settings. Second, the number of subjects was not large enough; therefore, a large-scale study is required. Third, we focused only on calorie selection by the participants, although information for other nutrients (sugar, protein, saturated fat, and sodium) was also provided. Fourth, although it is possible that fathers and mothers behave in different way when choosing menus for their children, this study did not consider it.

Notwithstanding these limitations, our findings have some important implications. Above all, the findings of the current study suggested that improving parental empowerment using nutritional information could be a strategy for promoting healthier food choices for children at fast-food restaurants.

References

- 1.Guthrie JF, Lin BH, Frazao E. Role of food prepared away from home in the American diet, 1977-78 versus 1994-96: changes and consequences. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2002;34:140–150. doi: 10.1016/s1499-4046(06)60083-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.French SA, Story M, Neumark-Sztainer D, Fulkerson JA, Hannan P. Fast food restaurant use among adolescents: associations with nutrient intake, food choices and behavioral and psychosocial variables. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2001;25:1823–1833. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Niemeier HM, Raynor HA, Lloyd-Richardson EE, Rogers ML, Wing RR. Fast food consumption and breakfast skipping: predictors of weight gain from adolescence to adulthood in a nationally representative sample. J Adolesc Health. 2006;39:842–849. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ebbeling CB, Sinclair KB, Pereira MA, Garcia-Lago E, Feldman HA, Ludwig DS. Compensation for energy intake from fast food among overweight and lean adolescents. JAMA. 2004;291:2828–2833. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.23.2828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rosenheck R. Fast food consumption and increased caloric intake: a systematic review of a trajectory towards weight gain and obesity risk. Obes Rev. 2008;9:535–547. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2008.00477.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ministry of Health and Welfare; Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Korea Health Statistics 2012: Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES V-3) Cheongwon: Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 7.New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (US) Notice of Intention to Repeal and Reenact Sec.81.50 of the New York City Health Code. New York (NY): New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ministry of Food and Drug Safety (KO) The special act on safety management of children's dietary life [Internet] Cheongju: Ministry of Food and Drug Safety; 2014. [cited 2014 May 27]. Available from: http://www.law.go.kr/lsInfoP.do?lsiSeq=154149&efYd=20140521#AJAX. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burton S, Creyer EH. What consumers don't know can hurt them: consumer evaluations and disease risk perceptions of restaurant menu items. J Consum Aff. 2004;38:121–145. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burton S, Creyer EH, Kees J, Huggins K. Attacking the obesity epidemic: the potential health benefits of providing nutrition information in restaurants. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:1669–1675. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.054973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pulos E, Leng K. Evaluation of a voluntary menu-labeling program in full-service restaurants. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:1035–1039. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.174839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roberto CA, Larsen PD, Agnew H, Baik J, Brownell KD. Evaluating the impact of menu labeling on food choices and intake. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:312–318. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.160226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harnack LJ, French SA, Oakes JM, Story MT, Jeffery RW, Rydell SA. Effects of calorie labeling and value size pricing on fast food meal choices: results from an experimental trial. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2008;5:63. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-5-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yamamoto JA, Yamamoto JB, Yamamoto BE, Yamamoto LG. Adolescent fast food and restaurant ordering behavior with and without calorie and fat content menu information. J Adolesc Health. 2005;37:397–402. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tandon PS, Zhou C, Chan NL, Lozano P, Couch SC, Glanz K, Krieger J, Saelens BE. The impact of menu labeling on fast-food purchases for children and parents. Am J Prev Med. 2011;41:434–438. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.06.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boles M, Maher JE, Moore JM, Knapp A. Variability in the nutritional value of fast-food purchases before the implementation of a statewide menu labeling policy; Proceedings of APHA 138th Annual Meeting and Exposition; 2010 Nov 6-10; Denver (CO). Washington, D.C.: American Public Health Association; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Drichoutis AC, Lazaridis P, Nayga RM., Jr Nutrition knowledge and consumer use of nutritional food labels. Eur Rev Agric Econ. 2005;32:93–118. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grunert KG, Wills JM, Fernández-Celemín L. Nutrition knowledge, and use and understanding of nutrition information on food labels among consumers in the UK. Appetite. 2010;55:177–189. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2010.05.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim SY, Nayga RM, Jr, Capps O., Jr Health knowledge and consumer use of nutritional labels: the issue revisited. Agric Resour Econ Rev. 2001;30:10–19. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Drichoutis AC, Lazaridis P, Nayga RM. Consumers' use of nutritional labels: a review of research studies and issues. Acad Mark Sci Rev. 2006;9:1–22. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tangari AH, Burton S, Howlett E, Cho YN, Thyroff A. Weighing in on fast food consumption: the effects of meal and calorie disclosures on consumer fast food evaluations. J Consum Aff. 2010;44:431–462. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wei W, Miao L. Effects of calorie information disclosure on consumers' food choices at restaurants. Int J Hosp Manag. 2013;33:106–117. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Spreitzer GM. Social structural characteristics of psychological empowerment. Acad Manage J. 1996;39:483–504. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fuchs C, Prandelli E, Schreier M. The psychological effects of empowerment strategies on consumers' product demand. J Mark. 2010;74:65–79. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wathieu L, Brenner L, Carmon Z, Chattopadhyay A, Wertenbroch K, Drolet A, Gourville J, Muthukrishnan AV, Novemsky N, Ratner RK, Wu G. Consumer control and empowerment: a primer. Mark Lett. 2002;13:297–305. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Steel JL. Interpersonal correlates of trust and self-disclosure. Psychol Rep. 1991;68:1319–1320. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sawhney M, Verona G, Prandelli E. Collaborating to create: The Internet as a platform for customer engagement in product innovation. J Interact Mark. 2005;19:4–17. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cranage DA, Conklin MT, Lambert CU. Effect of nutrition information in perceptions of food quality, consumption behavior and purchase intentions. J Foodserv Bus Res. 2004;7:43–61. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cranage D, Sujan H. Customer choice: A preemptive strategy to buffer the effects of service failure and improve customer loyalty. J Hosp Tour Res. 2004;28:3–20. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Farrow CV, Blissett J. Controlling feeding practices: cause or consequence of early child weight? Pediatrics. 2008;121:e164–e169. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-3437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ventura AK, Birch LL. Does parenting affect children's eating and weight status? Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2008;5:15. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-5-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barreiro-Hurlé J, Gracia A, de-Magistris T. Does nutrition information on food products lead to healthier food choices? Food Policy. 2010;35:221–229. [Google Scholar]

- 33.White House Task Force on Childhood Obesity Report to the President (US) Solving the Problem of Childhood Obesity within a Generation. Washington, D.C.: White House Task Force on Childhood Obesity Report to the President; 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kent G. Nutrition education as an instrument of empowerment. J Nutr Educ Behav. 1998;20:193–195. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marietta AB, Welshimer KJ, Anderson SL. Knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors of college students regarding the 1990 Nutrition Labeling Education Act food labels. J Am Diet Assoc. 1999;99:445–449. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8223(99)00108-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cho SH, Yu HH. Nutrition knowledge, dietary attitudes, dietary habits and awareness of food-nutrition labelling by girl's high school students. Korean J Community Nutr. 2007;12:519–533. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim MG, Oh SW, Han NR, Song DJ, Um JY, Bae SH, Kwon H, Lee CM, Joh HK, Hong SW. Association between nutrition label reading and nutrient intake in Korean adults: Korea National Health and Nutritional Examination Survey, 2007-2009 (KNHANES IV) Korean J Fam Med. 2014;35:190–198. doi: 10.4082/kjfm.2014.35.4.190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gracia A, Loureiro M, Nayga RM., Jr Do consumers perceive benefits from the implementation of a EU mandatory nutritional labelling program? Food Policy. 2007;32:160–174. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Din N, Zahari MS, Shariff SM. Customer perception on nutritional information in restaurant menu. Procedia Soc Behav Sci. 2012;42:413–421. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Saha S, R Vemula S, Mendu VV, Gavaravarapu SM. Knowledge and practices of using food label information among adolescents attending schools in Kolkata, India. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2013;45:773–779. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2013.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim YS, Kim BR. Intake of snacks, and perceptions and use of food and nutrition labels by middle school students in Chuncheon area. J Korean Soc Food Sci Nutr. 2012;41:1265–1273. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu PJ, Roberto CA, Liu LJ, Brownell KD. A test of different menu labeling presentations. Appetite. 2012;59:770–777. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2012.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Morley B, Scully M, Martin J, Niven P, Dixon H, Wakefield M. What types of nutrition menu labelling lead consumers to select less energy-dense fast food? An experimental study. Appetite. 2013;67:8–15. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2013.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]