Abstract

Background:

Mobile health (mHealth) is an expanding field which includes the use of social media and mobile applications (apps). Apps are used in diabetes self-management but it is unclear whether these are being used to support safe drinking of alcohol by people with type 1 diabetes (T1DM). Alcohol health literacy is poor among young adults with T1DM despite specific associated risks.

Methods:

Systematic literature review followed by critical appraisal of commercially available apps. An eSurvey investigating access to mHealth technology, attitudes toward apps for diabetes management and their use to improve alcohol health literacy was completed by participants.

Results:

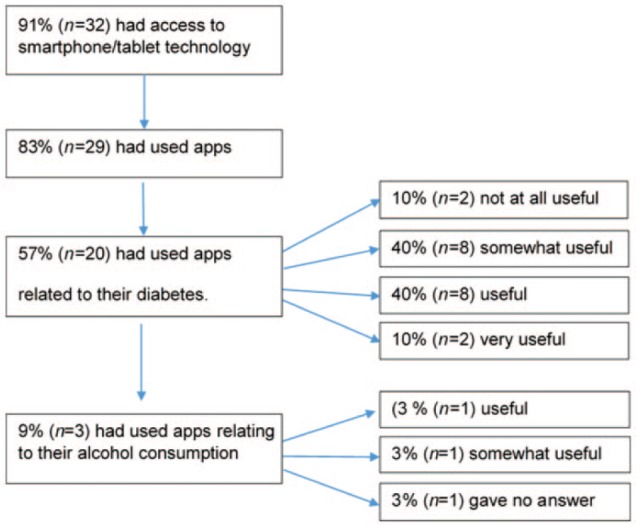

Of 315 articles identified in the literature search, 7 met the inclusion criteria. Ten diabetes apps were available, most of which lacked the educational features recommended by clinical guidelines. In all, 27 women and 8 men with T1DM, aged 19-31 years were surveyed. Of them, 32 had access to a smartphone/tablet; 29 used apps; 20 used/had used diabetes apps; 3 had used apps related to alcohol and diabetes; 11 had discussed apps with their health care team; 22 felt more communication with their health care team would increase awareness of alcohol-associated risks.

Conclusions:

Use of mobile apps is commonplace but the use of apps to support safe drinking in this population was rare. Most participants expressed a preference for direct communication with their health care teams about this subject. Further research is needed to determine the preferences of health care professionals and how they can best support young adults in safe drinking.

Keywords: alcohol, diabetes, mHealth, mobile apps, smartphone

The popularity of mobile applications (apps) for smartphones and tablets has grown in recent years. They are increasingly being used to support health behaviors, particularly for chronic conditions such as diabetes, and this is predicted to increase.1 Currently there are almost 100 000 health-related apps available on Apple’s App Store and Google’s Playstore. It is estimated that there will be some 500 million smartphone users worldwide using mHealth apps by 2015.1

Despite government initiatives for sensible drinking, binge drinking remains a sociocultural norm among young adults in the United Kingdom.2 Excessive alcohol consumption is associated with suboptimal glycemic control and specific diabetes related risks.3 Previous research has shown that young people use social media and mobile technologies to seek information regarding diabetes self-management and alcohol education.4 However the medical relevance or accuracy of information cannot be guaranteed.4

As apps become more established as health tools, they could offer potential to help increase alcohol health literacy. It is necessary to first determine the value of apps in type 1 diabetes (T1DM) self-management and how this resource can be utilized. Previous studies have demonstrated the distinct lack of effective interventions to help combat the risks of drinking for young adults with T1DM.3

Method

Literature Review

A search of MEDLINE, PubMed, and Google Scholar was conducted. Search terms included “diabetes mobile apps,” “diabetes smartphone,” and “diabetes mHealth.” Articles were judged for relevance by their titles and abstracts. Those that met the inclusion criteria were retrieved in full and reviewed. Inclusion criteria were that mHealth apps in studies were diabetes-specific and study findings were relevant to young adults (aged 18-30 years) with T1DM.

Critical Appraisal of mHealth apps

Online marketplaces (Google Play Store and Apple iTunes App Store) were systematically searched for mobile applications using the search term “diabetes.” Apps were filtered for relevance by their titles and descriptions; those included had to be designed for people with T1DM and contain information on alcohol.

Once downloaded, Android apps were reviewed on a Samsung Galaxy Mini and iOS apps were reviewed on an Apple iPad. Each app was critically appraised against the APPS (appliance/platform, purpose, person, safety) checklist (based on FDA criteria), which covered the safety of individual apps as well as their purpose, medical content, usability, and cost.5 Gap analysis was used to identify differences between the content of the apps and their stated aims.

Participant Survey

A 17-question eSurvey was developed to explore current attitudes toward resources for diabetes self-management and alcohol education. A total of 173 potential participants from a previous alcohol health literacy study by Jones et al,3 who had agreed to take part in future research, were contacted by email. They had been recruited for the previous study via Diabetes UK User Involvement Group, Facebook, Twitter, T1DM social network sites, and diabetes forums. Data from the completed surveys were subjected to thematic and content analysis.

Results

Literature Review

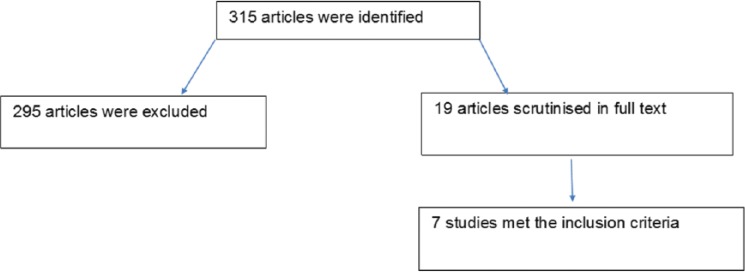

In all, 315 articles were identified in the literature search. Of these, 295 were excluded for not being suitable or relevant; 19 were scrutinized in full text, and 7 of these studies met the inclusion criteria (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Literature review article selection consort diagram.

Waite et al6

This is a study consisting of 8 people with T1DM (4 adults, 4 aged 8-16 years) examined the usability and perceptions of 4 iPhone apps by questionnaire and semistructured interviews. All 4 apps provided support for cognitive decision making. The apps covered glucose tracking, carbohydrate estimation, recipes, and education. The study found young people might be unaware that apps can be used to help manage their diabetes.6

Pulman et al7

Semistructured, in-depth, qualitative interviews of 7 men and 2 women, aged 18-21 years, identified possible ideas for apps and feelings toward them. Pulman et al highlighted that smartphones are not universally accessible due to cost. Four prototype apps were evaluated: diabetes and illness guide; diabetes and hypoglycemia guide; diabetes and alcohol guide; diabetes center Twitter newsfeed. There was particular demand for the diabetes and alcohol guide.7

Chomutare et al8

The study identified and assessed the features and functionality of the 137 diabetes apps (101 from online markets and 36 from related literature). The most prevalent features were insulin and medication recording (62% of apps) and data export and communication (60%). Of diabetes apps, 15% had social media functions. Only 7 of the 27 educational apps provided personalized feedback. The authors concluded it was impossible to know how many apps on the market were founded on evidence-based medicine.8

Breland et al9

This study examined the extent to which 227 diabetes self-management apps addressed the American Association of Diabetes Educators self-management behaviors (AADE7). These are healthy eating, being active, monitoring, taking medications, problem solving, reducing risks, and healthy coping. There was a median of 2 ADDE7 behaviors per app. A random 10% of the apps were downloaded and reviewed in full by the authors. No app addressed all 7 AADE7 criteria. Healthy eating and self-monitoring were found in 44.9% and 48% of apps, respectively. Of the apps, 11.9% covered “reducing risks,” and the skill “healthy coping” was found in 5.7%. The study found diabetes apps would benefit from theory based designs as currently only a small percentage of apps are evidence-based.9

Eng and Lee10

This study identified the categories of 100 apps relevant to diabetes and other endocrine diseases. Of apps, 33% were found to help with diabetes tracking; this included logging of insulin dosages, blood glucose, and carbohydrate counting. Teaching/training apps accounted for 22%, and food databases 8%. Apps for health care professionals (HCPs) accounted for a further 8%, and blogs/forums 5%. The authors highlighted safety and privacy concerns and the need for formal assessment.10 They also noted a lack of integration with health care delivery or evidence of clinical effectiveness of apps.

Rao et al11

This study featured a survey and review of the 12 highest rated diabetes self-management apps on iTunes. A total of 22 participants (12 men and 10 women) aged 18 to 66 years old with both T1DM (11) and T2DM (11) tested the apps. Those aged 18-44 were able to complete tasks quicker than those aged 44-66. Gender, level of education, and previous exposure to apps did not significantly affect the users’ ability to complete tasks.11

Jones et al12

This qualitative study explored the apps people use in relation to diabetes, what they think of them, and what HCPs should know about them. Peer communication and support was found to be very important. Comments in favor of the apps included that you can “update your knowledge constantly and instantly,” they provide “priceless feedback and you make friends,” and “apps make for a more interactive and controlled feel for care.”12

Critical Appraisal of Available Apps

A search of Google Play for “diabetes” returned 242 Android apps, of which 9 met the inclusion criteria. Apple’s App Store yielded a further 300 apps, of which 7 were relevant. Ten apps in total were included as the 6 apps available on both platforms were duplicates.

There were a variety of diabetes apps; the majority contained dietary advice (carbohydrate counting). Only 1 app, T1D Friend: Alcohol Guide, was specifically designed to increase alcohol health literacy and support safe consumption of alcohol in T1DM.13 It provides information on how to recognize and manage a hypo. Nine of 10 apps were not T1DM-specific and did not provide information specific to the risks of alcohol for people with T1DM.

The information varied from brief passing references to dedicated pages. Usability varied across the apps. The critical appraisal showed that apps have potential to be useful in general management of T1DM; but no app currently provides a definitive intervention for minimizing alcohol-associated risk (Table 1).

Table 1.

Core Features of Mobile Apps Critically Appraised to Determine Use in Improving Alcohol Health Literacy in Young Adults With T1DM.

| App | Android | iPad | iPhone | Free cost | Forum | Search function | Regular updates | Tips | FAQ | Disclaimer | Interactive | Explain hypos | Ad-free | Linked to social media | Food (carb) content | Type 1 specific | News feed | Evidence-based content | Alcohol-specific |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diabetes tips | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| Diabetes self-management | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Diabetes Info | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||

| T1D Friend: Alcohol Guide | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Dining out with diabetes | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||

| Diabetes FAQ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||

| DCUK forum | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Diabetes support forum | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Diabetes forums | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| Shot in the arm | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

eSurvey

A total of 27 women and 8 men, aged 19 to 31 years old, completed the survey (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

App usage among participants (n = 35).

In all, 6 participants had been recommended apps by their friends: Carbs & Cals (n = 3), Diabetes UK (n = 3), On Track (n = 1), mySugr (n = 1). And 13 participants had discussed apps with their health care team, mostly Carbs & Cals (n = 9). Of the participants, 84.6% (n = 11) still felt there was not enough guidance on apps.

Of the participants, 97% (n = 34) reported that they would find resources to support safe drinking useful (Table 2).

Table 2.

Methods Participants (n = 35) Use Currently to Calculate How Much They Are Drinking.

| Method | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Looking at the bottle label | 22 (63.0) |

| Best guess | 16 (46.0) |

| Look up online | 4 (11.4) |

| Alcohol formula | 1 (3.0) |

Resources required included information from health care team (n = 22), apps (n = 19), leaflets (n = 17), social media (n = 16), magazines (n = 14), books (n = 8), other (n = 6). “Other” included websites (n = 3), better nutritional labeling on drinks (n = 1), professional advice at diagnosis (n = 1), and professional advice during clinics (n = 1). A total of 60% (n = 21) thought an alcohol-specific diabetes app would be useful. Limited access to technology was an argument from those opposed to all diabetes apps. Some participants used other diabetes apps but did not want an alcohol-specific one.

A number of themes were identified in the answers to the survey. The numbers with each quotation correspond to the participant number followed by the question number.

Theme 1: A Desire for More Information to Support Safer Drinking

24.10: Own experience—no information is given to teenagers. Youth culture in the UK involves alcohol consumption before the age of 18, I was drinking regularly at 14. Had it not been for a pronounced Dawn Phenomenon I would have likely caused myself to have some extremely severe hypos. . . . There ought to be advice given on the effects of alcohol to all over 18 at diagnosis and to teens as young as 13. It’s a safety issue that is ignored and wholly inappropriately so.

10.15: I think making people aware of the real risks . . . specifically would be beneficial.

17.18: It is frustrating that alcoholic drinks don’t have to list their carb content. . . . I think young diabetics need to know the dangers of alcohol etc . . . ie, it can drop your blood sugar later and you hypo.

24.18: Drinking culture in the UK has been sidelined in diabetes care for far too long. As an ex-A&E nurse I have witnessed far too many youngsters fall foul of alcohol consumption in terms of staying well with diabetes. High time it was addressed in a sensible, honest, and upfront manner.

Theme 2: Support When Consuming Unfamiliar Drinks

25.11: I would like to know the effect the sugars would have.

32.11: Reference for times when I have forgotten or for looking at something I don’t usually drink.

21.13: It would be good to find specific information about an alcoholic drink I don’t normally drink.

Theme 3: Using Social Media

Of participants, 46% (n = 16) felt social media could be useful, mainly because they are easily accessible.

15.11: I am often on social media websites making it easier for me to access information regarding alcohol and diabetes.

22.11: I would be able to access information instantly when I needed it, especially if it was online or in an app.

24.11: Many young people are uncomfortable asking adults and HCPs questions face to face, asking questions via social media can remove that discomfort. The same reason would apply to an app.

33.11: Social media is always accessible.

Theme 4: Communication With Health Care Teams

11.11: Reliable info if it comes from health care team.

14.11: Your doctor or DSN is always useful as the information is from medical professionals.

19.11: I would prefer the information from the health team if it was going to affect my health and my ability to control my diabetes.

18.12: . . . being able to consult with MDT team my experience.

Theme 5: Barriers to App Use

2.18: I do not have a tablet or smart phone. . . . I don’t like using touch screen devices.

25.18: I am sight impaired so need light to read and in large print.

27.18: I would expect apps to be useful for people who use them more frequently than I do. . . . It would need to be endorsed by diabetes UK etc in my opinion.

32.18: I have no need or desire for a touch screen mobile or hardware in general so do not think I will be using apps for some time.

Theme 6: Access to Nutritional Information

17.15: A generic nutritional info app would not be much use as there is variation in the amount of carbs in beer, for example.

22.15: Units of alcohol, plus carbs (grams) contained in the alcoholic drink- this would also need to be relevant for the size of the drink.

Theme 7: Information for Friends/Family

7.15: It would be useful to include information on how to treat a hypo for the people who go out with you.

12.15: Information on how the different drinks affect blood sugars. Suggestions for ways to inform your friends of the effect of alcohol and how they can help if things go wrong.

15.15: Information on carbohydrate content of different drinks . . . information section for friends or medical professionals to access if necessary.

Theme 8: Resources Available When Out Drinking

3.13: Before and after a night out drinking.

7.13: When out drinking—particularly cocktail bars.

9.13: When I go out drinking, it would be useful to have a device to track my alcohol intake.

14.13: If I had an app on my mobile I would use it at bars etc to keep track of information.

Discussion

The aims of the study were to review the existing literature and to appraise critically apps for their ability to support safe drinking behaviors in T1DM. There was a limited literature focusing on the specific research question with mixed results. Articles focused on features and content of apps, and used qualitative and semistructured interviews to explore usability and user experience. A lack of integration with health care delivery or evidence of clinical effectiveness was apparent. While there are a plethora of apps available, features varied considerably with most focusing on insulin and medication recording, followed by dietary advice, and very few provided personal feedback or support. This was in line with findings from our critical appraisal.

Survey participants felt they did not have access to adequate resources to support their knowledge of the risks of alcohol and T1DM. Participants were using different methods to calculate how much they were drinking, depending on the situation. This included using their best guess. It is necessary to know the level of alcohol as well as the carbohydrate content, which varies widely, to be able to accurately react and either administer the appropriate dose of insulin or consume an appropriate amount of carbohydrates to maintain safe blood glucose levels.3 None of the appraised apps featured both the carbohydrate and alcohol contents of popular drinks. There have been calls for the government to require all alcoholic drinks to display their nutritional information on the bottle label.14

Among those that had access to smartphones or tablets app usage was not universal and for those that did use apps experiences were mixed. This may be indicative of the huge variability in quality, as well as the subjective nature of apps. Previous studies have shown that people with T1DM have different experiences of the disease as well as different personal preferences for technology.7,12 Most diabetes apps available were aimed at recording of blood glucose and calculating insulin.8,10 There are relatively few educational apps on the market and only some of those feature personalized feedback and advice.8

The critical appraisal found that many of the apps had usability/compatibility issues or did not function as intended. A number of apps were text heavy so more suited to tablet devices. Some were UK specific but others were aimed at a predominantly American audience. Nuances in language and culture make these apps less user friendly for a UK audience.

A number of participants in the survey stated they would like to use both magazines and apps to support safe drinking. One magazine app (Diabetes Self-Management) was identified during the critical appraisal. Alcohol articles were infrequent among the featured issues of Diabetes Self-Management. To improve alcohol health literacy, a permanent column would be necessary.

T1D Friend: Alcohol Guide was the only specific alcohol and diabetes app identified in the search. It was also the only app to have been reviewed by the NHS Health Apps Library. The Alcohol Guide gave sound advice on how to act following a hypo, but it did not explain in detail the different carbohydrate contents of various drinks. The podcast is an interesting feature of the app; it contains an audio recording of a diabetes consultant talking about alcohol. People want easy access to their health care team and being able to listen to professional advice remotely could help satisfy this need. The app could be improved by uploading new podcasts regularly and in response to user’s questions. This interactive approach would have the potential to really engage young adults with their diabetes management.

Around 15% of diabetes apps feature social media.8 Social media enable people with diabetes to share resources and remove barriers by making information easily accessible to a wide audience.4 Diabetes social media can be accessed without having to make contributions. For those wanting to contribute, forum apps allow people with diabetes to post questions and seek advice from other members. Peer-peer communication and support networks have proven very important to people with diabetes.12

Despite an active online community, only 6 participants had been recommended apps by their friends. Eng and Lee stated that a growing number of clinicians are being approached about the role of apps in diabetes management.10 Yet few in this study had discussed apps with their health care team. They are currently poorly integrated with health care delivery.10 This is despite the calls for medical professionals to be up to date with the latest technology and to recommend apps to their patients.6,15,16 The 2 most recommended apps were Carbs & Cals and Diabetes UK. One of the participants was testing a prototype app for research. In this study, user involvement was documented only in T1D Friend: Alcohol Guide.

A number of apps featured content that was not at the appropriate level for their users and was more suited to professionals. For example there were videos and diagrams in Diabetes FAQ that were very scientific in nature and unlikely to engage the user. Diabetes Info featured a graph showing correlation between diabetes and obesity that is wholly off-putting for potential users.

The clear consensus of a lack of guidance on apps shows that our health care teams could do more to inform and advise patients on the latest advancements in mHealth. Previous research has raised concerns that there is no requirement for formal assessment of apps.8,10 There are worries about inaccuracies and the quality of medical advice. The same may be said for social media. Health care professionals should therefore be involved in formulating and vetting content to ensure safety.4 The NHS Health Apps Library will help in this regard.17

There was no consensus among the participants as to what resources they would like to support self-management. Many of the participants selected multiple resources suggesting that the answer to minimizing alcohol-associated risk lies in a holistic approach using different methods to satisfy individual preferences. Receiving more information from your health care team was preferred followed by apps and leaflets.

Resources should supplement information from health care professionals. Having access to the appropriate information helps people gain a greater understanding and make informed choices. Donnelly et al have shown that while people feel “empowered by increased knowledge” they are reluctant to lose consultations with their health team.18 For example, contact with the diabetes MDT enables a person to utilize the team’s professional knowledge and receive tailored advice. This may be preferable to a generic app.

Results for whether an alcohol-specific app would be useful were mixed. People felt that apps could improve alcohol health literacy, but did not need a stand-alone app to do this, instead preferring 1 comprehensive app for all their needs. There was a common request for carbohydrate and alcohol content information. However, having numerous apps for various aspects of management, for example, separate apps for blood glucose logging, insulin calculator, as well as alcohol, would be inconvenient for some users. Conversely, a comprehensive app with several functions could make it difficult to find specific alcohol related information.

The ever-increasing number of apps available and the increasing interest in using such apps to support health behaviors such as diabetes self-management has shown considerable promise over recent years. There are numerous diabetes apps available to download and they cover a variety of specific niches;8-10,12 however, the critical appraisal has shown alcohol education content among diabetes apps is poor. Only 3 of 35 participants had actually used an app for this purpose, and some were unaware any existed. This reflects the overall lack of educational apps in the marketplace to support diabetes self-management.8,9 The lack of reference to evidence-based medicine or research requires attention as it is currently impossible to know how many apps are designed robustly based on evidence-based medicine or research.8

In the United Kingdom it is not uncommon for people to start drinking before the age of 18. This may be associated with risky drinking behaviors such as bingeing. However, alcohol is rarely discussed, and clinicians may find particular difficulty communicating with teenagers.3 It is therefore necessary to develop resources for teenagers, as well as young adults. Gender, education level, and previous exposure to mobile applications did not affect people’s ability to use diabetes apps.11

The study is limited in that people with T1DM taking part in the study did not appraise the apps themselves. There is also disparity between what participants desire and what is actually available. While every effort was made to identify all relevant apps, it is recognized that this search may not have been exhaustive.

Conclusion

Use of mobile apps is commonplace; however, use of mHealth technology to support safe drinking in this population was rare. Currently, apps do little to increase alcohol-associated risk awareness among young adults with T1DM. Most participants expressed a preference for direct communication with their health care teams. Further research is needed to determine the preferences of health care professionals in this regard, and how they can best support young adults with T1DM in safe drinking.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: AADE, American Association of Diabetes Educators; apps, applications; FDA, Food and Drug Administration; HCP, health care professional; MDT, multidisciplinary team; mHealth, mobile health; NHS, National Health Service; T1DM, type 1 diabetes mellitus.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1. Kamerow D. Regulating medical apps: which ones and how much? BMJ. 2013;347:f6009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Barnard K, Sinclair JM, Lawton J, Young AJ, Holt RI. Alcohol associated risks for young adults with type 1 diabetes: A narrative review. Diabet Med. 2012;29(4):434-440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Barnard KD, Dyson P, Sinclair JM, et al. Alcohol health literacy in young adults with type 1 diabetes and impact on diabetes management. Diabet Med. 2014;31(12):1625-1630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Jones E, Sinclair JM, Holt RI, Barnard KD. Social networking and understanding alcohol associated risk for people with type 2 diabetes: friend or foe? Diabetes Technol Ther. 2013;15(4):308-314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Verkerk M, Bargiela D. How to appraise medical apps: guideline based framework. BMJ Careers. October 22, 2013. http://careers.bmj.com/careers/advice/view-article.html?id=20015143. Accessed November 1, 2013.

- 6. Waite M, Martin C, Curtis S. Mobile phone applications and type 1 diabetes: an approach to explore usability issues and for potential for enhanced self management. Diabetes Primary Care. 2013;15(1):38-39. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pulman A, Taylor J, Galvin K, Masding M. Ideas and enhancements related to mobile applications to support type 1 diabetes. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2013;1(2):e(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chomutare T, Fernandez-Luque L, Årsand E, Hartvigsen G. Features of mobile diabetes applications: review of the literature and analysis of current applications compared against evidence based guidelines. J Med Internet Res. 2011;13(3):e65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Breland JY, Yeh VM, Yu J. Adherence to evidence based guidelines among diabetes self-management apps. Transl Behav Med. 2013;3(3):277-286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Eng DS, Lee JM. The promise and peril of mobile health applications for diabetes and endocrinology. Paediatr Diabetes. 2013;14(4):231-238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rao A, Hou P, Golnik T, Flaherty J, Vu S. Evolution of data management tools for managing self monitoring of blood glucose results: a survey of iPhone applications. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2010;4(4):949-957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jones R, Cleverly L, Hammersley S, Ashurst E, Pinkney J. Apps and online resources for young people with diabetes: the facts. J Diabetes Nurs. 2013;17:20-26. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pulman A, Hill J, Taylor J, Galvin K, Masding M. Innovative mobile technology alcohol education for young people with type 1 diabetes. Practical Diabetes. 2013;30(8):376-379a. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Eurocare European Alcohol Policy Alliance. Labelling. http://www.eurocare.org/resources/policy_issues/labelling. Accessed April 20, 2014.

- 15. Wardrop M. Doctors told to prescribe smartphone apps to patients. Telegraph, April 1, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Williamson S. The best model of care for children and young people with diabetes. J Coll Physicians Edinb. 2010;40(suppl 17):25-32. [Google Scholar]

- 17. NHS Choices. Health apps library. www.apps.nhs.uk. Accessed October 15, 2013.

- 18. Donnelly LS, Shaw RL, van der Akker OBA. eHealth as a challenge to “expert” power: a focus group study of Internet use for health information and management. J R Soc Med. 2008;101(10):501-506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]