Abstract

Osteochondral allograft implantation is an effective cartilage restoration technique for large defects (>10 cm2), though the demand far exceeds the supply of available quality donor tissue. Large bilayered engineered cartilage tissue constructs with accurate anatomical features (i.e. contours, thickness, architecture) could be beneficial in replacing damaged tissue. When creating these osteochondral constructs, however, it is pertinent to maintain biofidelity to restore functionality. Here, we describe a step-by-step framework for the fabrication of a large osteochondral construct with correct anatomical architecture and topology through a combination of high-resolution imaging, rapid prototyping, impression molding, and injection molding.

Keywords: Osteochondral graft, Anatomical contour, Rapid prototyping, Impression molding, Injection molding

1. Introduction

Articular cartilage, a white, dense connective tissue that lines diarthrodial joints, serves as the load-bearing material of joints, and is characterized by excellent friction, lubrication, and wear properties [1]. When damaged due to injury or osteoarthritis, the tissue undergoes degeneration resulting in pain and dysfunction. Upon becoming symptomatic, this discomfort necessitates surgical intervention. Treatment options, however, are dependent on the joint involved, the location, size and severity of the defect, and patient-related factors.

Endstage, global joint pathology often warrants total joint arthroplasty to replace the articulating surfaces and underlying bone. Total joint arthroplasty is associated with a relatively high need for revision surgery due to implant wear, subsidence, and/or loosening [2–5]. For focal articular cartilage lesions (<2 cm2), minimally invasive reconstructive surgical approaches including microfracture [6], autograft cell/tissue transfer via periosteal grafts [7], autologous osteochondral grafting such as mosaicplasty [8], and autologous chondrocyte implantation [9] are currently utilized. While these surgical treatment options can address symptoms of pain and improve function, they have not shown long-term durability and are associated with a number of limitations and potential complications. Cell-based therapies and osteochondral autograft harvesting are limited by the availability of healthy cartilage from which to harvest tissue or cells. Furthermore, autologous osteochondral grafts are harvested from non load-bearing regions that may provide tissue of sub-optimal material properties for use in load-bearing recipient sites [10]. Additionally, the harvest procedure itself can induce significant donor site morbidity [11,12], leading to further structural and biochemical breakdown in the joint.

For larger lesions, greater than 10 cm2, when articular cartilage loss has distorted the morphology of the condyle, fresh osteochondral allografts may be indicated [13]. The technical demands associated with this procedure and the limited supply of suitable grafts to meet clinical demand have prompted pursuit of cell-based therapies for cartilage repair, including tissue engineered constructs of cultured cells on three-dimensional scaffolds [14–17].

For engineered constructs to functionally bear the loads experienced in vivo, it is necessary to recreate the natural topology of the articular surface to fully recapitulate the normal contact geometry and load distribution across the joint [18–24]. To capture the complete 3D geometry of articular cartilage, the topography of the cartilage surface as well as the underlying subchondral bone must be quantified. A number of models derived directly from the target tissue have been used for the purpose of quantifying the articular joint surface. These include mechanical as well as optical techniques; the geometry of the articular layer of cartilage surfaces has been quantified using cryosectioning [25], stereophotogrammetry [26–28], A-mode ultrasound [29], and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) [30,31]. Many of these same techniques, in addition to computed tomography (CT), can be used to quantify the subchondral bone. Once acquired, these data are used to create negative templates for the desired tissue via computer aided design (CAD) and stereolithography, such as for the temporomandibular joint (TMJ) [32,33], the auricular cartilage of human ear [34], or to recreate iatrogenic defects on the articular surface of the femur [35]. Through the combination of CAD and injection molding, our previous work has created entire articular layers, successfully replicating the human patellar articular layer and trapeziocarpal articular layer of the thumb joint [24]. These large, full surface replications need only to integrate with the underlying subchondral bone and can be exposed to a milieu of chemical and physical stimuli [17,36–43] in vitro to optimize the functional properties of developing constructs.

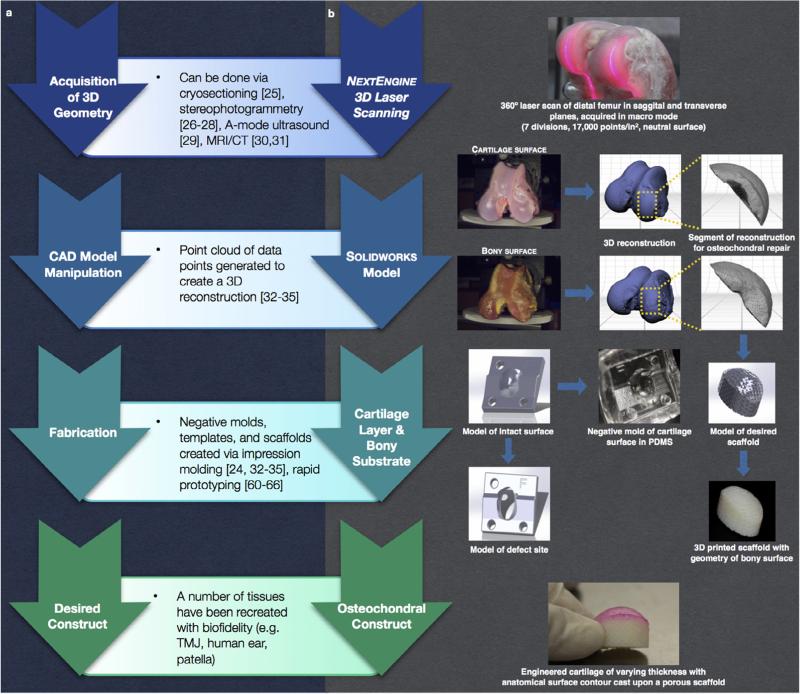

While the replication of full articular surfaces highlights one potential application of this technology, for clinical management of cartilage injuries, it may be more relevant to fabricate osteochondral constructs for large defects that exhibit anatomically defined surfaces matching the native architecture of both the cartilage surface and subchondral bone. As such, in this paper, we follow a general protocol for generating tissues with biofidelic shape (Fig. 1a), and detail how this principle may be applied to a specific embodiment, the fabrication of an osteochondral graft (Fig. 1b). As a bilayer of specialized soft-hydrated connective tissue (articular cartilage) and bony substrate, the osteochondral construct provides an ideal vehicle to showcase the capabilities of cutting-edge advances in imaging and rapid prototyping for complex and multi-phased entities. Specifically, here we take advantage of the high resolution of a 3-dimensional optical laser scanning (resolution = ±127 μm) to accurately capture the changing thickness of articular cartilage across the distal femur of an ex vivo knee joint, as defined by the articular surface and subchondral bone. This 3D information, coupled with rapid prototyping (3D printing), impression molding, and injection molding allows for the creation of a custom large surface area osteochondral defect replacement that restores congruency to the articular surface and subchondral bone.

Fig. 1.

Schematic of (a) general design protocol and (b) detailed implementation of steps for fabrication of an anatomical osteochondral graft.

2. Methods

For proof of concept, we performed this technique to generate a graft suitable for restoring a large femoral condyle defect in the dog. The use of adult canine tissue represents a large preclinical animal model with clinically relevant similarities to humans, notably in anatomy of the knee joint, pathology, and treatment. Surgical interventions such as arthroplasty, autologous chondrocyte transplantation, and osteochondral grafting, as well as postoperative care including bandages, braces, and physical rehabilitation, can be readily performed. Here, we created a large osteochondral implant for the medial femoral condyle. An intact canine stifle joint from a 2–5 year-old mongrel canine was dissected via removal of integument, fascia, muscle, and excision of capsular ligaments to expose the joint surface of the distal femur for 3D data acquisition.

2.1. 3D laser scanning

Surface morphology was acquired with a NextEngine™ HD Desktop 3D Scanner (NextEngine, Inc., California, USA), a portable device equipped with twin 3.0 megapixel CMOS image sensors. First, a transverse cut was made through the thickness of the femur ~4 cm proximal to the patellofemoral joint to allow for mounting of the joint to a 6 cm × 6 cm × 1 cm block supplemented with an alignment cube for proper positioning of the joint in three axes (Fig. 2a). A matrix of fiduciary markers on the mount was created using a white paint pen. Both joint and mounting block were placed within the field of view for image acquisition to allow for digitization of the joint surface over 360° with simultaneous fiduciary marker capture. Utilizing the NextEngine™ 3D ScanStudio™ HD software package, 3D scans were acquired in macro mode with optimized settings (360°, 7 divisions, 17,000 points/in.2, neutral surface). To obtain the full curvature of the surface, 2 panels of images were acquired from varying angles in both the sagittal (Fig. 2b) and transverse plane (Fig. 2c). During imaging, phosphate buffered saline was administered to the cartilage as necessary to maintain tissue hydration. Following capture of the articular cartilage surface, while still secured to the mounting jig, the distal femur was submerged in bleach (5–10% sodium hypochlorite) for 45 min to expose the subchondral bone. The same 2 panels of images were then acquired in a similar manner as the articular cartilage surface (Fig. 2d and e).

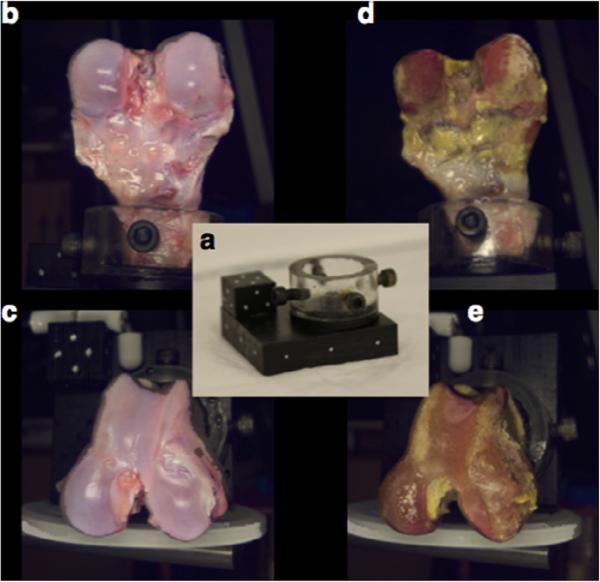

Fig. 2.

(a) A mounting setup was used for 360° imaging of the intact articular surface and subchondral bone in the saggital (b and d) and transverse (c and e) planes. A matrix of fiduciary markers, including an alignment cube positioned on the surface of the mounting block, was used to globally align scans of the two surfaces during image processing.

The ScanStudio™ HD software package was then used to process the acquired point clouds, aligning and trimming the reconstruction. Articular cartilage surface and subchondral bone layers were aligned relative to their global markers to ensure that any model manipulations were confidently consistent. For this proof of concept, we focused on creating a large osteochondral construct on the medial condyle, the most common site of unicompartmental osteoarthritis in the joint; accordingly, the models (Fig. 3a) were trimmed to expose only this region (Fig. 3b). Once the desired surface was isolated, a water-tight model was fused, simplifying the point cloud where advantageous without losing accuracy (63.5 μm tolerance), resulting in a 38,980 point model. Before the models could be manipulated via computer-aided design (CAD), surfaces were created from the fused models using ScanStudio™ HD CAD Tools (Fig. 3c), and when superimposed upon one another, resulted in the identification of the articular cartilage layer alone (Fig. 3d). Each model was approximated by 2001 surfaces. Once complete, these surfaces were exported as SolidWorks (Dassault Systemes, France) compatible IGES files.

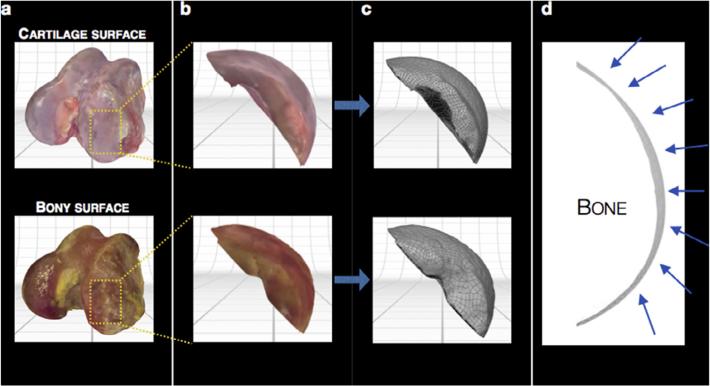

Fig. 3.

Manipulation of reconstructed models to isolate desired region. (a) Both cartilage and bony reconstructed surfaces were rendered in color, (b) trimmed to expose only the medial femoral condyle, and (c) modeled by 2001 surfaces for CAD manipulation. (d) A representative silhouette of the articular cartilage thickness following subtraction of the subchondral bone from the intact articular cartilage model (changing thickness marked by arrows).

2.2. CAD modeling

The solid surface models for the intact articular cartilage layer and underlying subchondral bone were then manipulated to produce three pieces: (1) an intact articular cartilage model for a negative mold, suitable for biological contact; (2) a defect template that allows for scaffold delivery, and (3) a scaffold model with the contour of the subchondral bone (Fig. 4a). To create an artificial defect on the medial condyle, a large ellipsoid covering ~70% of the cartilage surface was imposed on the intact articular cartilage model to produce the defect template. This large defect size on the canine condyle was chosen to reflect a critical size defect when scaled up for the size of the human medial condyle [44]. Following completion of the defect template, the same defect geometry was mirrored on the subchondral bone model, creating an implant geometry identical to the defect site and with the surface topology of the underlying bone. This scaffold model was then modified with a multi-axis series of channels (Fig. 4a; 500 μm diameter, 1250 μm center-to-center) to mimic the networked trabecular structure of the subchondral bone. Following CAD modeling of these three pieces, the models were converted to rapid-prototyping ready stereolithography (.stl) files and imported into Objet Studio™ for transformation into 3D modeling slices.

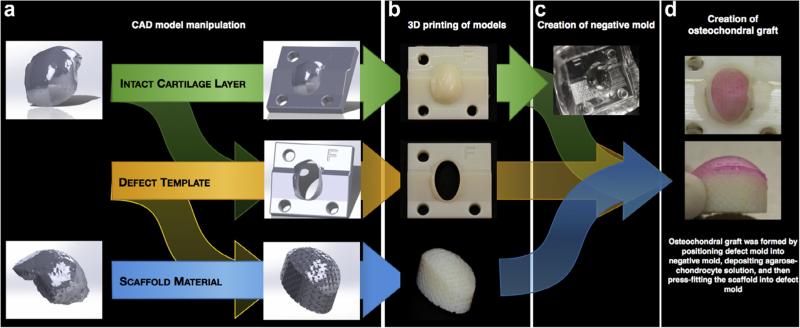

Fig. 4.

Fabrication process for creating a large anatomical osteochondral construct. (a) Solid surface models were manipulated to create three pieces (intact articular layer, defect mold, subchondral bone) that were (b) rapid prototyped via 3D printing. (c) A PDMS negative mold was formed from the intact cartilage mold and (d) all components were positioned together to create an osteochondral graft with anatomical topology and architecture.

2.3. Rapid prototyping

An Objet24 (Stratasys, Ltd., USA) desktop 3D printing system was used for rapid prototyping (Fig. 4b). In particular, the 28 μm print layers allowed for modeling and implementation of precision design features, including the accurate modeling of articular cartilage thickness. Following 3D fabrication, support material was removed from the models with a high-pressure water pick, which was further facilitated by submerging the pieces in an ultrasonic 1% alkali detergent bath for 1 h.

2.4. Negative mold fabrication

In order to recapitulate the morphology of the articular surface in a tissue-engineered osteochondral implant, a mold was created from the intact articular cartilage model. To allow for contact with biological tissues, a biocompatible silicone elastomer (Sylgard 184, Corning, USA) was selected for the mold material. 80 mL of polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) mixture was produced according to the manufacturers instructions in 2–50 mL conical tubes and centrifuged to remove air pockets. A polyoxymethylene cylinder (1″ OD; 3/4″ ID), used to stabilize the intact articular cartilage model once submerged in PDMS, was placed in the bottom of a hollow plastic rectangular container (with one face removed). Cylinder- and container-size was dependent on the size of the model. PDMS was added to the cylinder until cresting. The intact articular cartilage model was then inserted, allowing the base to rest on the polyoxymethylene cylinder. The remainder of the PDMS was added, ensuring the model was completely submerged. This container was then placed in a vacuum chamber for 20 min to remove any remaining air pockets. Once a homogenous mixture was achieved, the container was transferred to a 60 °C oven overnight (~16 h) to ensure complete curing. Once cured, the plastic container was removed with a band saw, taking care not to damage the PDMS. The mold was then trimmed as necessary to expose the base of the intact articular cartilage model, which was removed from the PDMS mold (Fig. 4c), leaving behind a negative mold of the medial condyle.

2.5. Osteochondral implant fabrication

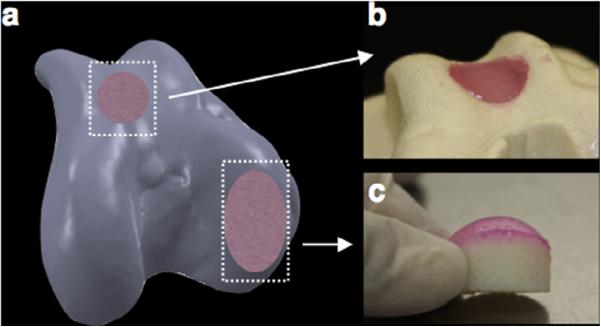

As described previously [45], chondrocytes were isolated from the femoral condyles of canine stifles, passaged twice, and suspended in chondrogenic medium at a concentration of 60 million cells/mL for implant fabrication. Concurrently, agarose (4%, Type VII, Sigma, USA), a natural polymer derived from seaweed, was prepared and maintained in molten state at ~40 °C until use. The negative mold, defect template, and scaffold model were sterilized with 70% ethanol and ultraviolet light. With all components prepared, the defect template was press fit into the negative mold, utilizing the posts and directional aids to ensure proper alignment. Equal parts cell solution and agarose were then mixed in a separate conical tube and 500 μL of this mixture (30 million cells/mL; 2% agarose) was deposited into the defect. Using the directional aids, the scaffold was then placed into the defect and pressed until flush with the base of the defect template, ensuring proper cartilage thickness. After allowing 10 min for gelation, both the defect template and osteochondral implant were removed from the negative mold. Using the easy access ports in the rear of the defect template, the osteochondral implant was carefully removed to reveal an anatomically shaped construct with accurate cartilage thickness (Fig. 4d) and placed into chondrogenic medium (CM) at a ratio of 10 mL CM per OC implant. This well-established agarose-based system has been shown to encourage favorable cell morphology and foster tissue growth over time [46–53].

3. Conclusion

The process described here represents the integration of several established techniques in an innovative manner to produce a large clinically relevant osteochondral graft with appropriate surface topologies and cartilage thickness.

Maintaining biofidelity of anatomical surfaces has long been a goal of tissue engineering, with impression molds of cadaveric tissues used as models to produce negative molds of curved tissues. To date, extensive work has been done to replicate complex geometries such as a human ear [34], mandibular joint [33], and avulsed phalanx [54]. Stereophotogrammetry, in combination with CNC milling and injection molding, has been used to quantify, model, and replicate the articular surface of the human patella [24,26–28]. CAD-based injection molds have been used for a variety of applications including cardiovascular [55,56] and musculoskeletal tissues [24,57]. With a focus on clinical feasibility, the field has recently shifted to the utilization of medical imaging modalities to inform the creation of anatomically shaped engineered tissues. These imaging modalities, such as fluoroscopy, MRI, CT, and ultrasound enable the replication of patient specific architectures and have greatly facilitated the use of additive manufacturing in the biomedical sciences. In the time since, medical imagining modalities have been used to partially or fully recreate the specific geometries of the tissue of interest. MRI and μCT of bovine knees have been used to inform CAD models of meniscal architecture [57,58]. Rapid prototyping (solid free form fabrication, 3D printing, etc.) has allowed the widespread realization of digital models. First introduced in the early 2000s as researchers looked for a way to create 3D organs with shape fidelity [59], new advances in 3D printing have been applied to osteochondral composites, allowing for spatial control of material and chemical properties through the depth of a tissue [60–62], as well as TMJ reconstruction [63,64], humeral head regeneration [65], and tissue-engineered epiglottis [66]. Recent advances include hybrid printing, allowing the simultaneous deposition of electrospun fibers with cell-seeded hydrogels to provide optimal mechanical and biological properties layer by layer [67].

The protocol outlined herein exploits several of these established technologies to provide a blueprint for tissue reconstruction and replacement as it pertains to the knee joint (Fig. 1). While we have shown utility of this protocol through 3D data acquisition from an ex vivo knee joint, similar patient-specific information acquired through clinically used medical imaging (e.g. MRI, CT [30,31,68]) can be incorporated via commercially available and open-sourced software platforms (via Mimics®, TurtleSeg, Geomagic, etc.). Further, the framework of this process can be tailored to the equipment available, however, the ability to capture the anatomical geometry of the articular cartilage layer and underlying subchondral bone [57] is critical, as the success of osteochondral graft replacement is heavily dependent on the surgeon's ability to restore native joint congruency [18–24], which inherently includes cartilage thickness. Additionally, once the articular geometry is obtained for the entire diarthrodial joint (Fig. 5a), any sub-region of interest (e.g., distal femoral condyle, trochlear groove, etc.) can be generated. For comparison, we have illustrated this by producing engineered constructs in the form of a cylindrical osteochondral plug suitable for repair of focal defects (Fig. 5b) and, as described here, as a larger construct able to replace an entire condyle (Fig. 5c).

Fig. 5.

Example of how (a) 3D reconstruction of the articular surface can be used to generate osteochondral constructs for a range of defect sites: (b) focal defects and (c) large surface defects.

The choice of method of acquisition of 3D data, from laser scanning technologies in the laboratory to clinical MRI or CT scans, is dictated by the goal at hand (modeling purposes vs. creation of tissue engineered constructs) and perhaps by the desired resolution. For the current application of replacing damaged cartilage, anatomically shaped osteochondral constructs could be personalized for an individual by acquiring pertinent 3D geometry data to create a custom mold, or obtained from a plurality of a population for a given set of characteristics (e.g. height, weight, gender). For the former, the accuracy of currently available clinical imaging modalities may pose a limitation in the near future. Accuracy of the cartilage thickness derived from a cartilage model from 1.5 Tesla MR images (B-spline snake method for segmentation) has been shown to be to be affected by the actual thickness of the tissue; thin cartilage is overestimated while thick cartilage is underestimated [69]. The use of 3.0 Tesla magnets capable of higher in-plane resolution (0.31 mm or less [70]) along with additional segmentation techniques may provide for more accurate cartilage thicknesses. With this in mind, it may be more useful to produce a variety of available sizes and shapes based on a plurality of the population, providing the possibility for an off-the-shelf graft.

The work presented herein provides a framework for fabrication of a complex, multi-layered construct through a combination of high-resolution imaging, rapid prototyping, impression molding, and injection molding. Our approach has accurately recreated, for the first time, a large, anatomically shaped osteochondral graft to meet the rapidly increasing demand of allografts for large area cartilage repair.

Acknowledgements

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01 AR60361 and T32 AR059038. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. Funding support from the Coulter Foundation and a NSF Graduate Fellowship (BLR) is also acknowledged.

References

- 1.Mow VC, Lai M. Biorheology. 1990;27(1):110–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ayers DC. Instr. Course Lect. 1997;46:205–213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bradley GW, et al. Clin. Mater. 1993;14(2):127–132. doi: 10.1016/0267-6605(93)90034-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mowery C, Botte M, Bradley G. Orthopedics. 1987;10(2):309–313. doi: 10.3928/0147-7447-19870201-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Whiteside LA. Orthop. Clin. North Am. 1989;20(1):113–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Steadman JR, Rodkey WG, Rodrigo JJ. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2001;(391 Suppl.):S362–S369. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200110001-00033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O'Driscoll SW, et al. J. Orthop. Res. 2001;19(1):95–103. doi: 10.1016/S0736-0266(00)00014-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hangody L, et al. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 1997;5(4):262–267. doi: 10.1007/s001670050061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brittberg M, Lindahl A, Nilsson A, Ohlsson C, Isaksson O, Peterson L. Treatment of deep cartilage defects in the knee with autologous chondrocyte transplantation. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1994;331(14):889–895. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199410063311401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ahmad CS, et al. Am. J. Sports Med. 2001;29(2):201–206. doi: 10.1177/03635465010290021401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee CR, et al. J. Orthop. Res. 2000;18(5):790–799. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100180517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee DA, et al. Biorheology. 2000;37(1–2):149–161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bugbee WD. J. Knee Surg. 2002;15(3):191–195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lima EG, et al. Biorheology. 2004;41(3–4):577–590. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mauck RL, et al. J. Biomech. Eng. 2000;122(3):252–260. doi: 10.1115/1.429656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pazzano D, et al. Biotechnol. Prog. 2000;16(5):893–896. doi: 10.1021/bp000082v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vunjak-Novakovic G, et al. J. Orthop. Res. 1999;17(1):130–138. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100170119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cooney WP, III, Chao EY. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 1977;59(1):27–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chao GA, et al. Adv. Bioeng. 1992;22:191–194. ASME BED. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ateshian GA, Rosenwasser MP, Mow VC. J. Biomech. 1992;25(6):591–607. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(92)90102-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ateshian GA, et al. J. Orthop. Res. 1995;13(3):450–458. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100130320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eberhardt AW, et al. J. Biomech. Eng. 1990;112(4):407–413. doi: 10.1115/1.2891204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huberti HH, Hayes WC. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 1984;66(5):715–724. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hung CT, et al. J. Biomech. 2003;36(12):1853–1864. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(03)00213-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Staubli HU, et al. J. Bone Joint Surg. Br. 1999;81(3):452–458. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.81b3.8758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ateshian GA, Soslowsky LJ, Mow VC. J. Biomech. 1991;24(8):761–776. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(91)90340-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ghosh SK. J. Biomech. 1983;16(8):667–674. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(83)90118-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huiskes R, et al. J. Biomech. 1985;18(8):559–570. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(85)90011-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Adam C, et al. Clin. Biomech. (Bristol, Avon) 1998;13(1):1–10. doi: 10.1016/s0268-0033(97)85881-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cohen ZA, et al. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 1999;7(1):95–109. doi: 10.1053/joca.1998.0165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eckstein F, et al. Surg. Radiol. Anat. 1994;16(4):429–438. doi: 10.1007/BF01627667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Undt G, et al. J. Craniomaxillofac. Surg. 2000;28(5):258–263. doi: 10.1054/jcms.2000.0159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weng Y, et al. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2001;59(2):185–190. doi: 10.1053/joms.2001.20491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cao Y, et al. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1997;100:297–302. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199708000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Koo S, et al. Int. J. Artif. Organs. 2010;33(10):731–737. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gooch KJ, et al. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2001;286(5):909–915. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kaysen JH, et al. J. Membr. Biol. 1999;168(1):77–89. doi: 10.1007/s002329900499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Freed LE, et al. Proc. Natl. Sci. U.S.A. 1997;94(25):13885–13890. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.25.13885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ateshian GA, Hung CT. Functional properties of native articular cartilage. In: Guilak F, et al., editors. Functional Tissue Engineering. Springer-Verlag; New York: 2003. pp. 46–68. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mauck RL, et al. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2002;30(8):1046–1056. doi: 10.1114/1.1512676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Byers BA, et al. Trans Orthop Res Soc. 2006;31:43. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mauck RL, et al. Adv. Bioeng. 2003 0283.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bian L, et al. Am. J. Sports Med. 2010;38(1):78–85. doi: 10.1177/0363546509354197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Parma H, Gilmore RS, Palfrey AJ. J. Anat. 1988;157:233–234. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ng KW, et al. Tissue Eng. Part A. 2010;16(3):1041–1051. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2009.0581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Knight MM, Lee DA, Bader DL. Biochem. Biophys. Acta. 1998;1405:67–77. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4889(98)00102-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Knight MM, et al. Trans. Orthop. Res. Soc. 2000;25:105. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lee DA, et al. J. Biomech. 2000;33:81–95. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(99)00160-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lee DA, et al. J. Orthop. Res. 1998;16(6):726–733. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100160615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bian L, et al. Trans. Orthop. Res. Soc. 2007;32:1477. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bian L, et al. Osteoarthritis cartilage. 2009;17(5):677–685. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2008.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kelly TN, et al. Summer Bioengineering Conference. Vail CO.; 2005. Tension-compression nonlinearity in chondrocyte-seeded agarose hydrogels. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mauck R, et al. J. Biomech. Eng. 2000 Jun;122:9. doi: 10.1115/1.429661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vacanti CA, et al. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001;344(20):1511–1514. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200105173442004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Baudis S, et al. Biomed. Mater. 2011;6(5):055003. doi: 10.1088/1748-6041/6/5/055003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Neidert MRT. Tissue Eng. 2006;12(4):13. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ballyns JJ, et al. Tissue Eng. Part A. 2008;14(7):1195–1202. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2007.0186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ballyns JJ, et al. J. Biomech. 2011;44(3):509–516. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2010.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mironov V, et al. Trends Biotechnol. 2003;21(4):157–161. doi: 10.1016/S0167-7799(03)00033-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sherwood JK, et al. Biomaterials. 2002;23(24):4739–4751. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(02)00223-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhang W, et al. Biomed. Res. Int. 2014;2014:746138. doi: 10.1155/2014/746138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Schek RM, Taboas JM, Seqvich SJ, Hollister SJ, Krebsbach PH. Tissue Eng. 2004;10(9/10):10. doi: 10.1089/ten.2004.10.1376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Feinberg SE, Hollister SJ, Halloran JW, Chu TM, Krebsbach PH. Cells Tissue Organs. 2001;169:13. doi: 10.1159/000047896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Grayson WL, et al. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2010;107(8):3299–3304. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905439106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lee CH, et al. Lancet. 2010;376(9739):440–448. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60668-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Brown BN, et al. Tissue Eng. Part C Methods. 2014;20(6):506–513. doi: 10.1089/ten.tec.2013.0216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Xu T, et al. Biofabrication. 2013;5(1):015001. doi: 10.1088/1758-5082/5/1/015001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ateshian GA, Hung CT. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2005;436:81–90. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000171542.53342.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Koo S, et al. J. Biomech. Eng. 2009;131(12):121004. doi: 10.1115/1.4000087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Eckstein F, et al. Magn. Reson. Med. 2007;58(2):402–406. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]