Abstract

Radiotherapy has long played a role in the management of melanoma. Recent advances have also demonstrated the efficacy of immunotherapy in the treatment of melanoma. Preclinical data suggest a biologic interaction between radiotherapy and immunotherapy. Several clinical studies corroborate these findings. This review will summarize the outcomes of studies reporting on patients with melanoma treated with a combination of radiotherapy and immunotherapy. Vaccine therapies often use irradiated melanoma cells, and may be enhanced by radiotherapy. The cytokines interferon-alpha and interleukin-2 have been combined with radiotherapy in several small studies, with some evidence suggesting increased toxicity and/or efficacy. Ipilimumab, a monoclonal antibody which blocks cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen-4, has been combined with radiotherapy in several notable case studies and series. Finally, pilot studies of adoptive cell transfer have suggested radiotherapy may improve the efficacy of treatment. The review will demonstrate that the combination of radiotherapy and immunotherapy has been reported in several notable case studies, series and clinical trials. These clinical results suggest interaction and the need for further study.

Keywords: melanoma, immunotherapy, radiation therapy, radiotherapy, interaction, radioimmunotherapy, combination, combined

Introduction

Radiotherapy and immunotherapy are both commonly used in the treatment of melanoma. Many preclinical studies have been conducted that suggest interactions between radiation and immunotherapy (1). However, clinical reports detailing the interaction of these two treatments are limited. Because radiotherapy and immunotherapy are both independently effective in patients with melanoma, studying the combination of these treatments in patients is logical. In this review, we focus on the results of studies reporting on the treatment of patients with melanoma using a combination of radiotherapy and immunotherapy.

Treatment Outcomes in Locally Advanced and Metastatic Melanoma and the Role of Radiotherapy

Melanoma can be a recalcitrant disease, often requiring multiple modalities of anticancer treatment. A recent medical claims database analysis demonstrated that 66.8%, 44.7% and 38.7% of patients with metastatic melanoma underwent surgery, radiotherapy and systemic therapy, respectively (2). Despite advances in each of the therapeutic modalities rendered, patients with advanced melanoma generally have poor outcomes. Five year survival rates for stage III and IV cutaneous melanoma range from 39-70% and 7-19%, respectively (3). Less common forms of melanoma, such as uveal and mucosal melanoma, also have poor outcomes. Even though most patients with uveal melanoma present with localized disease, recurrence with distant metastasis is common; 5 year survival rates of medium and large primary tumors in the pivotal Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Studies were 81% and 59%, respectively (4, 5). Mucosal melanomas are similarly associated with high relapse rates and poor prognosis, with 5 year survival rates of approximately 25% (6).

Radiotherapy has long played a role in the management of all types and stages of melanoma. In early or locally advanced cutaneous melanoma, radiotherapy has been shown to be valuable, either as an alternative or adjuvant to surgery (7). In uveal melanoma, brachytherapy and external beam radiotherapy have both been used and provide high rates of local tumor control with preservation of vision (8), (9). In the rare case of mucosal melanoma, radiotherapy is likely to improve locoregional disease control; however data to support this approach are limited (6). Once any form of melanoma has metastasized, radiotherapy can provide valuable palliation (10). Given these outcomes, exploring novel treatments and combining therapeutically active agents such as radiotherapy and immunotherapy in locally advanced and metastatic melanoma are warranted.

Immunologic Effects of Radiotherapy in Preclinical Melanoma Models

Radiotherapy exerts effects through numerous biologic mechanisms. In the context of melanoma, preclinical radiobiological studies have suggested that some effects may be immune-mediated. For example, investigators at Indiana University used a murine melanoma model to study the effect of radiation dose fractionation on the development of lung metastases. Mice with melanomas treated with hypofractionated radiotherapy (32 Gy in 4 once weekly fractions) had superior survival, irradiated tumor control and fewer lung metastases than mice treated with conventionally fractionated radiotherapy (60 Gy in daily 30 fractions). Natural killer cell activity was greater in animals treated with hypofractionated radiotherapy and the authors suggested that this immunologic effect was responsible for improved outcomes (11). More recently, investigators at Vanderbilt University found that mice that underwent irradiation of a melanoma tumor to 25 Gy in 1 fraction prior to surgical excision had fewer lung metastases than mice that underwent excision but no radiation treatment. Greater tumor infiltration by CD8+ T cells in mice that had previously received an ex vivo irradiated melanoma vaccine were noted, and the authors suggested that dendritic cell (DC)-mediated phagocytosis was responsible for the decrease in metastasis frequency in mice with irradiated tumors (12). Similarly, investigators at the University of Chicago reported that the efficacy of high dose ablative radiotherapy in a mouse model of melanoma was mediated by CD8+ T cells (13). The vast body of preclinical data detailing the immunologic effect of radiotherapy in models of melanoma is beyond the scope of this review, but has implicated the immune system is an important part of the anti-melanoma response to radiotherapy.

Immunologic Effects of Radiotherapy in Patients with Melanoma

Several reports of patients with melanoma who have received radiotherapy support the concept that radiation modulates the immune system. Kingsley reported on a 28 year-old man with extensive radiographic evidence of inguinal, pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenopathy from melanoma. He experienced regression of all lymphadenopathy after irradiation of only the inguinal lymphatics with 14.4 Gy of fast neutrons in 12 fractions over 35 days, without subsequent recurrence of disease (14). Dosimetric analyses suggested that the para-aortic lymphadenopathy received <2% of the prescription dose, and therefore the regression of disease at a distance from the irradiated melanoma was characterized an “abscopal effect” (15), which some have suggested is an immune-mediated phenomenon (16).

Three more recent case reports of patients treated with radiotherapy suggest modulation of the immune system after radiotherapy, with associated durable disease regression. In one case, a 67 year-old man experienced depigmentation within the target volume several weeks after completing axillary irradiation (60 Gy in 30 fractions). Several months later, the patient developed brain metastases, and 2 weeks after completing a course of whole brain radiotherapy to 20 Gy in 5 fractions he developed depigmentation within and outside of the target volume, at sites not previously irradiated. At last follow-up, 3 years after the development of brain metastases, he was without evidence of melanoma. Immunologic analyses of the patient's peripheral blood, depigmented skin and metastases demonstrated the presence of specific CD8+ T-cell and B-cell responses against melanocyte differentiation antigens (MART-1, gp100) (17). A similar report described depigmentation in a 69 year-old man that received radiotherapy to the cervical lymphatics with 50 Gy in 25 fractions and subsequently developed vitiligo of the irradiated neck as well as the non-irradiated legs (18). A third patient with progressing melanoma after initial systemic therapy with the RAF inhibitor, vemurafenib, had disease regression at distant sites after receiving stereotactic radiosurgery for a brain metastasis. He ultimately developed vitiligo and whitening of the hair (19). Figures 1 and 2 present examples of halo depigmentation surrounding irradiated dermal metastases from cutaneous melanoma in two patients undergoing immunotherapy, suggesting a local immunologic effect. Some have speculated that depigmentation or vitiligo is a sign of effective immunotherapy for melanoma (20), although only a few studies have validated this observation after radiotherapy (17).

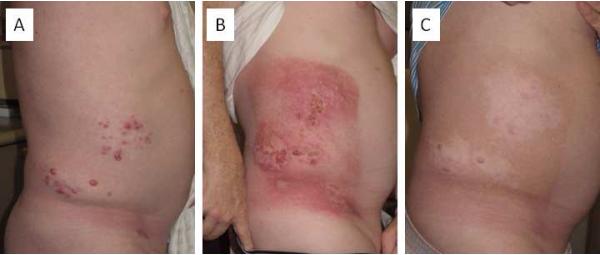

Figure 1.

Halo depigmentation surrounding irradiated dermal metastases from cutaneous melanoma. A 53 year-old man receiving ipilimumab for recurrent unresectable dermal metastases of melanoma on the right flank (A). Three weeks after receiving 36 Gy in 6 fractions to the right flank (B). Three months after completing radiotherapy hyperpigmentation of the irradiated skin and halo depigmentation surrounding the irradiated metastases were noted (C).

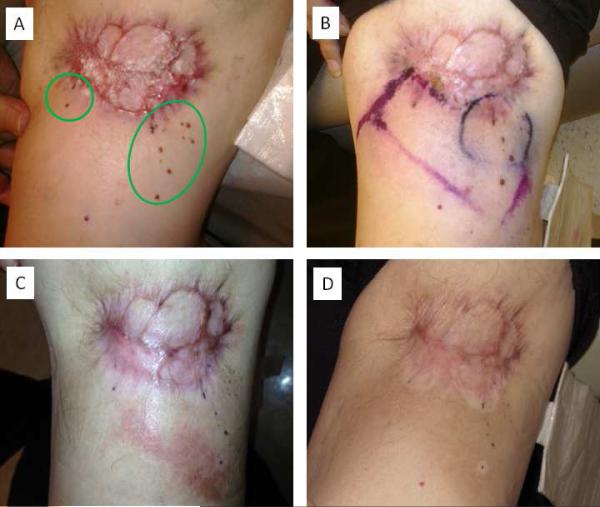

Figure 2.

Halo depigmentation surrounding irradiated dermal metastases from cutaneous melanoma. A 69 year-old man receiving 5% imiquimod cream for recurrent unresectable dermal metastasis (circled in green) of melanoma on the left upper leg (A). Electron beam radiotherapy fields were demarcated on the skin surface (B). Eight weeks after completing 45 Gy in 15 fractions (C). Six months after completing radiotherapy hyperpigmentation of the irradiated skin and halo depigmentation surrounding the irradiated metastases were noted (D).

Several studies have suggested changes in various components of the immune system after brachytherapy for uveal melanoma. For example, Federman and Shields noted a significant increase in tumor associated antibodies in patients treated with brachytherapy but not enucleation (21). Others have noted differences in the pattern of macrophage and T-lymphocyte tumor infiltration when comparing eyes enucleated primarily and those enucleated after brachytherapy; however, differences in these patient populations limit the interpretation of the findings (22), (23). A recent study demonstrated that after brachytherapy, IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-8 increase in the aqueous humor; levels of IL-6 and IL-8 were positively associated with scleral surface radiation dose (24). Similar to reports of depigmentation after external beam radiotherapy for cutaneous melanoma described above, investigators recently described a 28 year-old woman who developed halo depigmentation around cutaneous nevi 2 months after plaque brachytherapy for choroidal melanoma (25).

Therapeutic Vaccines Combined with Radiotherapy for Melanoma

Melanoma was the first tumor found to induce cytotoxic antitumor antibodies (26), and since then many investigations have evaluated various vaccines administered with the goal of increasing recognition of melanoma by the immune system. A phase III study of patients who received peptide vaccine gp100 in combination with the immunostimulatory cytokine interleukin-2 (IL-2) had an improved response rate and progression free survival compared to patients who received IL-2 alone (27). In another study, vaccination with the cancer-testis antigen MAGE-A3 and an adjuvant resulted in several durable responses and suggested the type of adjuvant used may be relevant to maximize immunogenicity (28). Other results have been less encouraging, such as the cellular vaccine, Canvaxin™ (CancerVax Corporation, Carlsbad, CA). Despite promising phase II data (29), ultimately Canvaxin™ was found to be inferior to observation in a randomized controlled trial (30).

Many of the initial and current attempts at melanoma vaccine development utilized irradiated tumors (31). The type of radiation may affect vaccine development as gamma-radiation (at 200 Gy) was shown to yield different immunologic effects on melanoma cells than other forms of non-ionizing radiation (32). A randomized phase II study of patients with metastatic melanoma demonstrated improvements in overall survival with autologous DCs loaded with antigens from irradiated autologous patient-specific proliferating melanoma cells, compared to irradiated autologous patient-specific proliferating tumor cells (33). Interestingly, a multivariable analysis of patients treated with the aforementioned DC therapy revealed that prior radiotherapy for melanoma was associated with improved survival (34). While vaccine therapy alone has yielded limited results in the treatment of advanced melanoma, refinements in antigen processing and the use of vaccine adjuvants could render this a viable option for melanoma, particularly in combination with other immunotherapeutic strategies.

Interferon Combined with Radiotherapy for Melanoma

Interferon alpha-2b was approved by the United States Federal Drug Administration (US FDA) for use in stage IIB and III melanoma in 1995 and is currently the only approved adjuvant systemic therapy for patients with high risk locally advanced melanoma. Several trials have demonstrated relapse free survival benefit with this agent (35, 36). However, because of the significant side effects associated with treatment (flu-like symptoms, anorexia, fatigue, depression) and questionable overall survival benefit, use of this agent in the adjuvant setting remains controversial (37).

Interferon was shown to increase cellular radiosensitivity many years ago (38). In one study, cancer cell lines treated with interferon (but not similarly treated fibroblasts) demonstrated an increase in radiosensitivity suggesting the potential for interferon to enhance the effects of radiotherapy (39). Notably, no melanoma cell lines were tested in this experiment. Other in vitro studies suggest that different interferons may have differential capacity for radiosensitization, with the type I interferons (alpha and beta) acting as less potent radiosensitizers as type II interferon (gamma) (40). In vivo studies have suggested that interferon may exhibit both sensitizing and protective qualities when combined with radiotherapy, depending on the timing and dose of radiation (41).

Consistent with these preclinical observations, retrospective clinical studies initially suggested the possibility of increased normal tissue toxicity with concurrent interferon and radiotherapy. In 2002, investigators at the University of Utah reported 10 patients with melanoma who underwent fractionated radiotherapy (45-52.5 Gy in conventional fractionation in 9 patients, or 36 Gy hypofractionated in 1 patient) and received varying doses of interferon alpha-2b concurrently, or within one month of radiotherapy. Severe complications were reported in 50%, with adverse events including: peripheral neuropathy (n=2), brain radionecrosis (n=1), and subcutaneous necrosis (n=2). Notably, brain necrosis occurred in the patient receiving the highest dose of radiation, and subcutaneous necrosis occurred in a patient receiving hypofractionated radiotherapy (42). In 2003, investigators at the University of Texas Southwestern reported on three patients with melanoma (2 mucosal) treated with concurrent interferon alpha and radiotherapy. In all three cases, grade 3 or 4 mucositis developed and radiotherapy was discontinued before planned total dose was delivered (43). In 2007, investigators from Barcelona reported on 18 patients with melanoma who received fractionated radiotherapy (30-36 Gy hypofractionated in 16 patients, 50 Gy in conventional fractionation in 2 patients) and varying doses of interferon alpha-2b concurrently (n=10), or within 30 days of radiotherapy (n=3), or more than 30 days after radiotherapy (n=5). One case of grade 3 telangiectasia and two cases of grade 4 myelopathy were observed; these adverse events were all in patients that received hypofractionated radiotherapy to the cervical lymphatics with the greatest doses reported in the study (36 Gy in 6 fractions) (44). Investigators from Australia reported on 18 patients with melanoma who underwent conventionally fractionated radiotherapy (40-50 Gy in 15-25 fractions) during maintenance phase of intermediate dose interferon alpha-2b. Grade 3 radiation dermatitis was observed in 39% of patients; 1 case of grade 3 pneumonitis and mucositis was observed. Regional relapse occurred in 1 patient, and distant recurrence occurred in 61% of patients (45). Limitations of these studies include the retrospective design and heterogeneity of treatments rendered. Nonetheless, improvement upon efficacy of each individual therapy was difficult to discern and the possibility for increased toxicity when combining interferon-alpha with radiotherapy was raised.

Recently, the Florida Melanoma Trial I clarified the toxicity and efficacy of combined therapy with systemic interferon and radiotherapy (46). This prospective, multicenter phase II study enrolled patients with high risk stage III cutaneous melanoma with ≥4 pathologically involved nodes, ≥4 cm nodes, or extracapsular extension between 1997 and 2000 who had undergone wide excision of the primary melanoma and regional lymphadenectomy. Treatment consisted of high dose induction interferon alpha-2b followed by concurrent intermediate dose interferon alpha-2b and hypofractionated nodal radiotherapy to 30 Gy in 5 fractions over 2.5 weeks. Of the 23 patients reported, 9% had grade 3 radiation dermatitis, but no patients had acute grade 3 mucositis. Among 11 patients with long-term follow-up, 1 case of grade 4 skin atrophy and 1 case of grade 4 neuritis were reported, with no grade 3 events described. At 5 and 10 years, regional disease control was 78%. However, overall and disease free survival were 48% and 43% at 3 years. The authors concluded that adjuvant hypofractionated radiotherapy could be combined with interferon alpha-2b without excessive acute or late toxicity. No clear improvement in either regional or distant disease control was apparent based on these results.

Interferon alpha-2b has also been studied in patients with uveal melanoma. In 2006, German investigators reported on a pilot study of 39 patients treated with 1 year of adjuvant low dose interferon alpha-2b after definitive radiotherapy (brachytherapy or radiosurgery) or enucleation for uveal melanoma. The authors did not report on radiation related complications. However, compared to historical controls, no improvements in any outcomes were observed (47). Similarly, investigators at the Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary conducted a prospective trial of 2 years of adjuvant low dose interferon alpha-2b after definitive radiotherapy (proton therapy) or enucleation for uveal melanoma. All patients enrolled were at high risk of metastasis (advanced age or primary tumor), but they were otherwise in good health. The authors of this study also did not report on ophthalmic complications, but systemic adverse events were frequent, consistent with systemic interferon alpha-2b treatment. Like the German study, no improvements in any outcomes were observed compared to historical controls (48).

In another study from Germany, 20 patients with palpable, unresectable cutaneous melanoma underwent intratumoral injections of 3-5 million units of interferon beta thrice weekly 30 minutes before radiotherapy, which was delivered 5 days a week to a total dose of 40-60 Gy in 1.8 Gy fractions. The authors report that treatment was well tolerated, but in some patients caused extreme pain, weakness, general malaise, nausea, or fever. Among 17 patients evaluated for response, clinical complete remission was noted in 12 (70%), with partial remission noted in the other 5. Among patients experiencing a complete response, median survival was approximately 18 months (range 4-93 months) while in patients experiencing a partial response, median survival was approximately 10 months (range 4-15 months). Based on these results, the authors concluded that combined intralesional interferon beta and radiotherapy are a viable option for the management of superficial, unresectable melanoma (49).

Interleukin-2 Combined with Radiotherapy for Melanoma

Interleukin-2 (IL-2) was approved by the US FDA for use in adults with metastatic melanoma in 1998 based upon its ability to result in long-term durable responses. IL-2 primarily functions as a T-cell growth factor and central regulator of immune function. An updated analysis of 8 clinical trials of high dose IL-2 conducted between 1985 and 1993 revealed a 16% objective response rate (10% partial response, 6% complete response), which was durable in 4% (50). IL-2 is associated with the possibility of significant side effects, including hemodynamic instability and autoimmune complications, and for this reason, its use as a single agent therapy is not widespread. Given the durability of some responses to IL-2, many studies are actively investigating whether combining IL-2 with other anti-melanoma agents may improve the proportion of patients who benefit.

Preclinical studies in mice suggested that low dose total body irradiation (TBI) might increase the low response rates seen with IL-2 for melanoma. In these studies, mice inoculated intravenously with B16F1 melanoma cells were treated with TBI to 0.75 Gy in 1 fraction, and then received 5 days of IL-2. Two days after the completion of treatment, mice treated with TBI and IL-2 had significantly fewer lung tumors than mice treated with either TBI or IL-2 alone. In mice treated with TBI and IL-2, significantly more natural killer cells and macrophages were noted in the tumors, peripheral blood, and spleen compared to mice treated with either treatment alone; no differences in CD4+ or CD8+ cells were noted in mice treated with TBI and IL-2 compared to those treated with IL-2 (51). A follow-up study demonstrated that delaying the start of treatment by 3 days allowed for melanoma disease burden to double. With the increase in disease burden, the efficacy of low dose TBI and IL-2 was abrogated unless the dose of IL-2 was doubled (52). In a later publication, the authors noted that CD4+ CD25+ suppressor cells also increased with tumor melanoma disease burden (53). Importantly, the authors noted that decreasing the TBI dose from 0.75 Gy to 0.075 Gy had no effect on tumor growth, although fewer tumor infiltrating macrophages were noted at the lower dose. In addition, among mice treated with high dose IL-2, more tumor infiltrating macrophages and fewer tumor infiltrating CD4+ cells were noted with the higher TBI dose. Interestingly, mice receiving TBI alone appeared to have greater tumor burden than those not receiving any treatment.

Based on these results, a phase II clinical trial in 45 patients with metastatic melanoma was conducted. Patients received treatment in 5 week cycles consisting of TBI to 0.1 Gy in 1 fraction on days 1, 8, 22 and 30, and high dose subcutaneous IL-2 twice daily on days 2-5, 9-12, 16-19, 31-34. Grade 3 or 4 fatigue was noted in 36% of patients. Less than 5% of patients experienced other grade 3 or 4 toxicity. No patients had a complete response, 2 patients (4.4%) had a partial response, and 13 patients (11.5%) had stable disease by RECIST criteria. Median overall survival was 6.2 months. Correlative immunologic analyses in 17 patients demonstrated compared to pretreatment, significant decreases in B-cells and monocytes and a significant increase in natural killer cells and IL-2b receptor bearing cells were noted 8 days into concurrent treatment. The authors compared the results of this study to the outcome of a matched group of patients and did not identify any improvement in outcome (53).

Other preclinical studies suggested that when combining IL-2 and radiotherapy, the target volume and dose may be important. Investigators at the National Cancer Institute used a murine adenocarcinoma model of liver metastases and found that prior to IL-2 therapy, focal liver radiation to 7.5 Gy in 1 fraction yielded greater survival compared to no radiation, TBI to 7.5 Gy in 1 fraction or TBI with liver shielding to 7.5 Gy in 1 fraction. Additional experiments found that prior to IL-2, the highest radiation dose (10 Gy in 1 fraction) produced longer survival than lower doses. The reduction in total liver metastases with local liver irradiation persisted when only half of the liver was irradiated, suggesting that the antitumor effects occurred outside of the irradiated volume (54).

Based on the results above, a phase I study was carried out at the National Cancer Institute. Fourteen patients with metastatic melanoma and at least 2 sites of measurable disease participated in this study. All patients underwent local radiotherapy of a metastatic site with 10-20 Gy in 5 Gy fractions given twice daily. Two to 24 hours after completion of radiotherapy, 10 melanoma patients received high dose IL-2 and 4 patients received high dose IL-2 and tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs, discussed further below). Of the melanoma patients treated with IL-2 only, 1 patient experienced a complete response in the irradiated tumor after 20 Gy, with partial response of a non-irradiated tumor; 5 patients demonstrated stable irradiated tumors. One of the patients with stable disease in an irradiated tumor also had stable disease in non-irradiated sites; all other patients experienced progression. The authors concluded that radiotherapy to 10-20 Gy before IL-2 was tolerable but did not significantly increase antitumor effects (55).

Somewhat different results were recently reported in a phase I study of stereotactic ablative body radiotherapy and high dose IL-2, which included 7 patients with metastatic melanoma. These investigators conducted a retrospective analysis of patients treated at their institution with single dose or hypofractionated radiotherapy during the week prior to high dose IL-2. Eight patients with melanoma were identified, and among these patients, 3 experienced a complete response of non-irradiated metastases, and 2 experienced partial response of non-irradiated metastases, for an overall response rate of 62.5%. In the phase I study, patients with metastatic melanoma and at least 2 metastases, with 1 lesion in the lung, mediastinum or liver amenable to radiotherapy were enrolled. Patients underwent radiotherapy to 1-3 metastases, finishing treatment 3 days prior to the first dose of high dose IL-2. IL-2 was given every 8 hours for up to 14 doses; up to 6 cycles of IL-2 was given to patients with regressing disease with 2 week rests in between cycles. The study enrolled 3 radiation dose cohorts, and escalated the number of fractions delivered from 1 to 3, all at 20 Gy per fraction (unless in the central thorax, when 16 Gy was used) for a total of 20-60 Gy. No dose limiting toxicities of radiotherapy were observed, and a maximum tolerated dose was not reached. IL-2 toxicities were no different than those observed in patients receiving IL-2 monotherapy. All irradiated metastases regressed after radiotherapy, without recurrence or evidence of FDG uptake on PET. By RECIST criteria, there was 1 complete response and 4 partial responses, for an overall response rate of 71% (95% CI 29-96%). Median response duration of response among melanoma patients was 553.5 days, with 4 of 7 patients still responding at the time of the report. Higher radiation doses were not clearly associated with response; PET complete responses occurred in all 4 patients treated with 1 or 2 fractions of radiotherapy, while 2 of 3 patients treated at the highest dose level experienced progressive disease. Correlative immunologic analyses demonstrated that patients with a higher proportion of proliferating early activated effector memory CD4+ and CD45A expressing CD8+ T-cells before and during the first 15 days of treatment were more likely to respond to treatment. This specific treatment regimen appeared particularly promising with a response rate of 71%, compared to the 16% response rates with IL-2 alone (56). Additional support of this approach is provided by the report of a 65 year-old woman with recurrent, metastatic cutaneous melanoma with prolonged survival (at least 3 years) after stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) for 2 brain metastases followed by IL-2 (57).

Cytotoxic T-Lymphocyte Antigen-4 Blockade (Ipilimumab) Combined with Radiotherapy for Melanoma and Other Immunomodulatory Antibody Approaches

Ipilimumab was approved by the US FDA in 2011 for the treatment of unresectable and metastatic melanoma after the completion of two trials showing an overall survival improvement (58, 59). Ipilimumab is a monoclonal antibody against cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA-4). CTLA-4 is an important negative regulator of T cell mediated antitumor immune responses. By blocking CTLA-4, ipilimumab enhances antitumor immunity.

Preclinical studies with non-melanoma cancer models have demonstrated that CTLA-4 blockade promotes the abscopal effect of radiotherapy. Investigators at New York University used a bilateral flank tumor model of a poorly immunogenic mammary carcinoma with the 4T1 cell line. In these studies, CTLA-4 blockade alone did not delay tumor growth or affect survival. However, when one of the flank tumors was irradiated with 12 Gy in 1 fraction, followed by CTLA-4 blockade, mice were noted to have improved survival. Fewer lung metastases were noted in animals treated with radiation and CTLA-4 blockade, and that this effect appeared dependent on CD8+ cells. When the radiation dose was increased to 24 Gy in 2 fractions 48 hours apart, the survival of mice increased (60). A follow-up study indicated that invariant natural killer cells may be a key mediator of response to the combination of radiotherapy and CTLA-4 blockade (61). In another series of experiments, a radiation dose of 24 Gy in 3 fractions seemed to be more effective than 30 Gy in 5 fractions or 20 Gy in 1 fraction at inducing antitumor immunity. Moreover, delaying the initiation of CTLA-4 blockade until after the completion of radiotherapy appeared to diminish the effect of the combination treatment (62).

Given the frequency of brain metastasis in patients with melanoma, some of the first clinical reports on the outcome of radiotherapy and ipilimumab described the treatment of brain metastasis. All have been retrospective and conclusions are limited by small patient numbers and heterogeneous treatment regimens. Investigators at Yale University reported on 77 patients with brain metastases from melanoma that underwent SRS. They reported that patients that received ipilimumab had a median survival of 21.3 months, and those that did not who survived a median of 4.9 months, despite a very similar diagnosis-specific graded prognostic assessment. Among the patients that received ipilimumab and SRS, survival was not significantly different if the drug was given before or after SRS (63). In a similar study, investigators from New York University reported on 58 patients treated with brain SRS. No difference in local tumor control, survival, or the frequency of intracranial hemorrhage in patients that did or did not receive ipilimumab was reported (64). Investigators at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) recently reported on 45 patients treated with ipilimumab and brain SRS. On multivariable analysis, prolonged survival was associated with the delivery of SRS during ipilimumab. Because of the retrospective nature of the analysis, it is unclear if selection of patients with favorable disease or treatment response characteristics biased the results. Radiographically, it was noted that brain metastasis size increase >150% occurred in 40% of the tumors treated with SRS before or during ipilimumab; this occurred in 10% of metastases treated with SRS after ipilimumab. Hemorrhage was also noted after SRS during ipilimumab in 42% of treated brain metastases (65). The potential complications of brain SRS and ipilimumab was studied by Belgian investigators in a small series of 3 patients. In patients receiving brain SRS to 20 Gy in 1 fraction, followed several months later by ipilimumab, radiation necrosis was observed histologically in 1 case and radiographically in 2 (66).

A few reports have described successful outcomes of patients treated with ipilimumab and whole brain radiotherapy. One study reported on a 49 year-old patient with recurrent melanoma and brain metastases. Four weeks after receiving 30 Gy of whole brain radiotherapy, the patient received ipilimumab. Significant regression of brain metastases was noted 12 weeks after initiating ipilimumab (67). Another study described a 63 year-old female patient with leptomeningeal disease who received whole brain radiotherapy to a dose of 20 Gy in 5 fractions, followed by ipilimumab. Two to 3 months after completing treatment she was noted to have a complete radiographic response with no symptoms of leptomeningeal disease (68). Given the poor outcomes of multifocal brain metastases not amenable to SRS and leptomeningeal melanoma, these cases are promising, but further study will be necessary.

Several case studies have described the results of combining ipilimumab and non-brain radiotherapy in patients with metastatic cutaneous melanoma. Investigators at MSKCC recently reported on a patient with recurrent, metastatic cutaneous melanoma who demonstrated a remarkable response to radiotherapy while receiving ipilimumab. A 39 year-old woman with recurrent, metastatic cutaneous melanoma undergoing ipilimumab on research protocol was noted to have slowly progressing disease in multiple locations. She underwent palliative radiotherapy to a painful paraspinal metastasis to a dose of 28.5 Gy in 3 fractions. Approximately 4 months later, imaging demonstrated regression of the irradiated tumor, as well as non-irradiated metastases in the pulmonary hilum and spleen. Correlative immunologic analyses demonstrated a decrease in myeloid derived suppressor cells after radiotherapy and a diversification of antibody responses after radiotherapy as assessed by seromic analysis (69). In a separate report, investigators at MSKCC observed regression of dermal in-transit metastasis surrounding an unresectable cutaneous melanoma irradiated with a dose of 24 Gy in 3 fractions. This 67 year-old man later developed brain metastases, which were treated with brain SRS and ipilimumab. He subsequently survived for 4 years. Correlative immunologic analysis revealed detectable antibody titers against MAGE-A3 after irradiation (70). A patient treated at our center demonstrating the abscopal effect of radiotherapy during immunotherapy is presented in Figure 3. Investigators from Stanford University reported on a 57 year-old man with recurrent, metastatic cutaneous melanoma treated with ipilimumab. After the second dose, he was noted to have enlargement of 2 liver metastases, and development of 5 new liver metastases. He underwent stereotactic ablative liver irradiation of 2 metastases to 54 Gy in 3 fractions. Six months after completing radiotherapy and ipilimumab, he was noted to have a complete response by PET (71). Though it is intriguing to believe these cases reflect true abscopal responses, since ipilimumab alone can result in complete and delayed responses, it is possible some of these remarkable responses may have been due to ipilimumab alone.

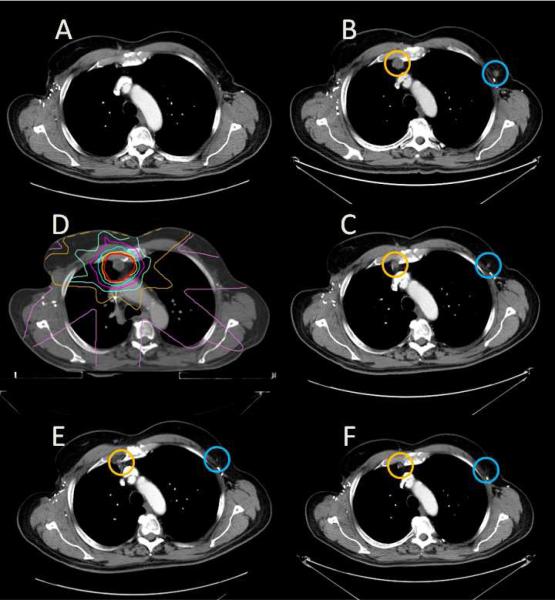

Figure 3.

Abscopal effect of radiotherapy in a melanoma receiving systemic immunotherapy. A 66 year-old man receiving ipilimumab on clinical trial for recurrent, metastatic melanoma with no evidence of disease 24 months after starting treatment (A). Three months later a right internal mammary lymph node (circled in orange) increased in size to 1.5 × 1.6 cm and a left axillary lymph node (circled in blue) increased in size to 1.1 × 1.0 cm (B). He received external beam radiotherapy to 27 Gy in 3 fractions to the internal mammary lymph node (C, yellow represents 100% isodose line, pink represents 10% isodose line). Three months after radiotherapy, the right internal mammary lymph node decreased in size to 1.2 × 0.7 cm, and the non-irradiated left axillary lymph node decreased to 0.6 × 0.5 cm (D). Six months after radiotherapy, complete resolution of the enlarged lymph nodes was noted (E). Nineteen months after radiotherapy, he continues to receive ipilimumab (F).

To obtain a better understanding of the potential toxicities of combining radiotherapy and ipilimumab, investigators at MSKCC performed a retrospective analysis of 29 patients that received extracranial radiotherapy during ipilimumab. Compared to historical data, in this study population as a whole, the investigators noted no significant increase in adverse effects related to immunotherapy. However, at the highest doses of administered radiotherapy, we noted an increase in radiotherapy related adverse events. Radiotherapy did not appear to compromise the efficacy of ipilimumab (72).

The success of ipilimumab in improving overall survival in two prior phase III studies (58, 59), has given rise to subsequent immunomodulatory antibody approaches for patients with melanoma that target a number of different T cell co-stimulatory or co-inhibitory elements. While there are a number of these agents in clinical development, those involving the programmed death-1 (PD-1) axis have been the most extensively evaluated. None of the agents targeting the PD-1 axis has yet been approved for clinical use, but phase I investigations of nivolumab and lambrolizumab have demonstrated remarkably high response rates with durability and a tolerable safety profile (73, 74), and phase III studies are ongoing. Preclinical evidence suggests that PD-1 blockade may interact with radiation to improve local tumor control (75), survival (76), in a variety of radiation dose and fractionation schema (77). No clinical cases have yet been reported. In the near future, we expect further clinical evaluation of radiotherapy and antibody therapy against the PD-1 axis in patients with melanoma and other malignancies.

Adoptive Cell Transfer (ACT) Combined with Radiotherapy for Melanoma

While radiotherapy described in the sections above is given to localized targets, TBI is an immunomodulatory strategy used commonly as part of hematopoietic transplant and involves irradiation of the entire body. Adoptive T-cell transfer refers to acquisition of tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) from resected tumor specimens or tumor antigen specific T cells from peripheral blood and ex vivo expansion. Prior to reinfusion of these expanded cells, patients receive chemotherapy with or without TBI. The technique of adoptive cell transfer was initially developed at the National Cancer Institute, but techniques to generalize this form of immunotherapy have been developed at other institutions. These treatments have demonstrated remarkable efficacy in melanoma (78) but are limited by the specialized techniques required to develop effective T cells for transfer, the long lead time required for generation of T cells, and the general medical fitness required of patients to undergo this procedure.

In preclinical models, it has been reported that more intensive conditioning regimens prior to ACT are associated with higher likelihood of tumor response (79). In a comparison of the results of several pilot studies, investigators at the National Cancer Institute found that TBI regimens using the highest doses of radiotherapy (12 Gy in 6 fractions) resulted in the highest response rates (80). More recently efforts using CD8+ enriched young TILs in combination with TBI to 6 Gy in 3 fractions are being investigated (81).

Future Directions

Immunotherapy is currently demonstrating remarkable success in the treatment of advanced melanoma. Recently reported response rates of new immunotherapeutic approaches targeting PD-1 have dramatically exceeded historical outcomes (74, 82). Nonetheless, not all patients benefit and, given the immunologic effects of radiotherapy, we anticipate ongoing great interest in investigations of radiotherapy and immunotherapy in the treatment of patients with melanoma and a variety of other cancers. With the availability of novel reagents for studying the immunologic responses to radiotherapy, it is anticipated that a better appreciation of the mechanisms of interaction between these modalities will be gained.

However, it is anticipated that some patients may not benefit from radiotherapy and immunotherapy combinations, and for this reason biomarkers predictive of response will be needed. Extensive correlative investigations of intratumoral and peripheral blood immunologic changes, guided by prior and emerging preclinical data, will be essential to better understand mechanistic interactions between these two treatment modalities. Several prospective clinical studies combining radiotherapy and immunotherapy for melanoma are in progress, with others planned, and results are eagerly anticipated. Table 1 presents some of these studies as described by the National Cancer Institute (www.cancer.gov).

Table 1.

Ongoing clinical trials combining radiotherapy and immunotherapy for patients with melanoma.

| Study Phase | Title | Eligible patients (planned number of patients) | Sponsor | Treatment Regimen | Registry Number |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Pilot Study) | A Pilot Study of Ipilimumab in Subjects With Stage IV Melanoma Receiving Palliative Radiation Therapy | Unresectable metastatic melanoma, failed one prior systemic therapy (20) | Stanford University | Ipilimumab (3 mg/kg) every 3 weeks for 4 doses; radiotherapy starting 2 days after first dose | NCT01449279 |

| Phase 0 | Pilot Study of Sequential Hepatic Radioembolization and Systemic Ipilimumab in Patients With Uveal Melanoma Metastatic to Liver | Metastatic uveal melanoma with liver metastases (12) | Case Comprehensive Cancer Center | Ipilimumab; radioembolization with yttrium-90 microspheres 4 weeks prior to ipilimumab | NCT01730157 |

| Phase I | A Dose Escalation Phase I Study of Radiotherapy Administered in Combination with Anti-CTLA4 Monoclonal Antibody (Ipilimumab) in Patients with Unresectable Stage III or Stage IV Advanced Malignant Melanoma (Mel-Ipi-Rx) | Unresectable locally advanced or metastatic melanoma with at least one melanoma metastasis accessible to radiation therapy (30) | Institut Gustave Roussy | Ipilimumab (10 mg/kg) every 3 weeks for 4 doses, and then every 12 weeks; radiotherapy (escalating dose from 9 to 24 Gy in 3 fractions) delivered between 2nd and 4th dose of ipilimumab | NCT01557114 |

| Phase I | Phase I Study of Ipilimumab Combined With Whole Brain Radiation Therapy or Radiosurgery for Melanoma Patients With Brain Metastases | Metastatic melanoma with brain metastasis (24) | Thomas Jefferson University | Ipilimumab (escalating doses) every 3 weeks for 4 doses; whole brain radiotherapy during first 2 weeks of ipilimumab (Arm A) or stereotactic radiosurgery on same day as first dose (Arm B) | NCT01703507 |

| Phase I/II | RADVAX: A Stratified Phase I/II Dose Escalation Trial of Stereotactic Body RT Followed by Ipilimumab in Metastatic Melanoma | Metastatic melanoma, with index lesion between 1 cm and 5 cm (40) | University of Pennsylvania | Ipilimumab; stereotactic body radiotherapy (escalating fractions) prior to ipilimumab | NCT01497808 |

| Phase I/II | Peritumoral Injection of Immature Dendritic Cells to Irradiated Skin Metastases of Solid Tumors | Metastatic melanoma (or other solid tumors), with at least one subcutaneous or intradermal tumor that is amenable to peritumoral DC injection (20) | Hadassah Medical Organization | Local tumor radiotherapy, followed by injection of immature dendritic cells, followed by the injection of interferon alpha | NCT00278018 |

| Phase I/II | A Phase I/II Study of Intratumoral Injection of Ipilimumab in Combination with Local Radiation in Melanoma, Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma and Colorectal Carcinoma | Recurrent melanoma, has failed one prior systemic therapy (69) | Stanford University | Intratumoral ipilimumab (escalating doses); radiotherapy (3 fractions) beginning within 48 hours of ipilimumab | NCT01769222 |

| Phase II | Phase II Evaluation of Concurrent Ipilimumab Therapy and Stereotactic Ablative Radiation Therapy (SART) for Oligometastatic But Unresectable Malignant Melanoma | Stage III and IV melanoma with 5 or fewer metastatic sites (50) | Comprehensive Cancer Centers of Nevada | Ipilimumab (10 mg/kg) every 3 weeks for 4 doses, and then every 12 weeks; stereotactic ablative radiotherapy between 1st and 3rd dose of ipilimumab | NCT01565837 |

| Phase II, randomized | Phase II Randomized Trial of Ipilimumab Versus Ipilimumab and Radiotherapy in Metastatic Melanoma | Metastatic melanoma with at least 2 distinct measureable metastatic sites (100) | New York University | Ipilimumab (3 mg/kg) every 3 weeks for 4 doses, with (Arm B) or without (Arm A) radiotherapy (30 Gy in 5 fractions in 1 week), starting 3 days before ipilimumab | NCT01689974 |

| Phase II, randomized | Phase II Randomized Study of High Dose Interleukin-2 Versus Stereotactic Body Radiation (SBRT) and High Dose Interleukin-2 (IL-2) in Patients With Metastatic Melanoma | Metastatic melanoma with tumors amenable to radiotherapy in lungs, mediastinum, chest wall, non-long bones (44) | Providence Health and Services | Interleukin-2 (600,000 IU/kg) every 8 hours for up to 14 doses per cycle, for a maximum of 6 cycles; no radiotherapy or stereotactic body radiotherapy (20 Gy in 1 fraction or 40 Gy in 2 fractions) 3-5 days prior to interleukin-2 | NCT01416831 |

| Phase II, randomized | Prospective Randomized Study of Cell Transfer Therapy for Metastatic Melanoma Using Tumor Infiltrating Lymphocytes Plus IL-2 Following Non-Myeloablative Lymphocyte Depleting Chemo Regimen Alone or in Conjunction With 12 Gy Total Body Irradiation (TBI) | Metastatic melanoma with at least one lesion that is resectable for tumor infiltrating lymphocyte generation (118) | National Cancer Institute | Non-myeloablative chemotherapy with or without total body irradiation to 12 Gy in 6 fractions, followed by adoptive cell transfer with young tumor infiltrating lymphocytes and interleukin-2 | NCT01319565 |

Conclusions

In conclusion, several small clinical studies have reported on the combination of immunotherapy and radiotherapy for melanoma. The data suggest that these treatments may interact and lead increased therapeutic and/or adverse effects. Several ongoing studies will further evaluate these combinations in the necessary prospective fashion. Through correlative immunologic analyses, it may be possible to further understand how these treatments interact in order to refine approaches that may ultimately improve the outcomes of patients with melanoma.

Acknowledgement

The authors acknowledge Dr. Jedd D. Wolchok for his mentorship and critical review of this manuscript.

Support:

M. A. Postow is supported by the Conquer Cancer Foundation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Presented in part at the American Radium Society, Scottsdale, Arizona, May 1, 2013.

Conflict of Interest: M. A. Postow has a commercial research grant and is an unpaid consultant/advisory board member for Bristol Meyers-Squibb. No other actual or potential conflicts of interest exist.

References

- 1.Formenti SC, Demaria S. Combining radiotherapy and cancer immunotherapy: a paradigm shift. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105:256–265. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang S, Zhao Z, Barber B, et al. Surgery, radiation, and systemic therapies in patients with metastatic melanoma. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2012;30:A232–A233. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Balch CM, Gershenwald JE, Soong SJ, et al. Final version of 2009 AJCC melanoma staging and classification. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:6199–6206. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.4799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study G The COMS randomized trial of iodine 125 brachytherapy for choroidal melanoma: V. Twelve-year mortality rates and prognostic factors: COMS report No. 28. Arch Ophthalmol. 2006;124:1684–1693. doi: 10.1001/archopht.124.12.1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hawkins BS, Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study G The Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study (COMS) randomized trial of pre-enucleation radiation of large choroidal melanoma: IV. Ten-year mortality findings and prognostic factors. COMS report number 24. Am J Ophthalmol. 2004;138:936–951. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2004.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mihajlovic M, Vlajkovic S, Jovanovic P, et al. Primary mucosal melanomas: a comprehensive review. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2012;5:739–753. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barker CA, Lee NY. Radiation therapy for cutaneous melanoma. Dermatol Clin. 2012;30:525–533. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2012.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jampol LM, Moy CS, Murray TG, et al. The COMS randomized trial of iodine 125 brachytherapy for choroidal melanoma: IV. Local treatment failure and enucleation in the first 5 years after brachytherapy. COMS report no. 19. Ophthalmology. 2002;109:2197–2206. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(02)01277-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Char DH, Quivey JM, Castro JR, et al. Helium ions versus iodine 125 brachytherapy in the management of uveal melanoma. A prospective, randomized, dynamically balanced trial. Ophthalmology. 1993;100:1547–1554. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(93)31446-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huguenin PU, Kieser S, Glanzmann C, et al. Radiotherapy for metastatic carcinomas of the kidney or melanomas: an analysis using palliative end points. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1998;41:401–405. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(98)00021-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shen RN, Hornback NB, Shidnia H, et al. A comparison of lung metastases and natural killer cell activity in daily fractions and weekly fractions of radiation therapy on murine B16a melanoma. Radiat Res. 1988;114:354–360. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Perez CA, Fu A, Onishko H, et al. Radiation induces an antitumour immune response to mouse melanoma. Int J Radiat Biol. 2009;85:1126–1136. doi: 10.3109/09553000903242099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee Y, Auh SL, Wang Y, et al. Therapeutic effects of ablative radiation on local tumor require CD8+ T cells: changing strategies for cancer treatment. Blood. 2009;114:589–595. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-02-206870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kingsley DP. An interesting case of possible abscopal effect in malignant melanoma. Br J Radiol. 1975;48:863–866. doi: 10.1259/0007-1285-48-574-863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mole RH. Whole body irradiation; radiobiology or medicine? Br J Radiol. 1953;26:234–241. doi: 10.1259/0007-1285-26-305-234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Demaria S, Ng B, Devitt ML, et al. Ionizing radiation inhibition of distant untreated tumors (abscopal effect) is immune mediated. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004;58:862–870. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2003.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Teulings HE, Tjin EP, Willemsen KJ, et al. Radiation-induced melanoma-associated leucoderma, systemic antimelanoma immunity and disease-free survival in a patient with advanced-stage melanoma: a case report and immunological analysis. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:733–738. doi: 10.1111/bjd.12136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abood A, Saleh DB, Watt DA. Malignant melanoma and vitiligo: can radiotherapy shed light on the subject? J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2009;62:e119–120. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2008.06.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sullivan RJ, Lawrence DP, Wargo JA, et al. Case 21-2013. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:173–183. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcpc1302332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yee C, Thompson JA, Roche P, et al. Melanocyte destruction after antigen-specific immunotherapy of melanoma: direct evidence of t cell-mediated vitiligo. J Exp Med. 2000;192:1637–1644. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.11.1637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Federman JL, Felberg NT, Shields JA. Effect of local treatment on antibody levels in malignant melanoma of the choroid. Trans Ophthalmol Soc U K. 1977;97:436–439. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Toivonen P, Kivela T. Infiltrating macrophages in extratumoural tissues after brachytherapy of uveal melanoma. Acta Ophthalmol. 2012;90:341–349. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.2010.01985.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vu TH, Bronkhorst IH, Versluis M, et al. Analysis of inflammatory cells in uveal melanoma after prior irradiation. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;54:360–369. doi: 10.1167/iovs.12-9424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee CS, Jun IH, Kim TI, et al. Expression of 12 cytokines in aqueous humour of uveal melanoma before and after combined Ruthenium-106 brachytherapy and transpupillary thermotherapy. Acta Ophthalmol. 2012;90:e314–320. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.2012.02392.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sarici AM, Shah SU, Shields CL, et al. Cutaneous halo nevi following plaque radiotherapy for uveal melanoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 2011;129:1499–1501. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2011.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morton DL, Malmgren RA, Holmes EC, et al. Demonstration of antibodies against human malignant melanoma by immunofluorescence. Surgery. 1968;64:233–240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schwartzentruber DJ, Lawson DH, Richards JM, et al. gp100 peptide vaccine and interleukin-2 in patients with advanced melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2119–2127. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1012863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kruit WH, Suciu S, Dreno B, et al. Selection of Immunostimulant AS15 for Active Immunization With MAGE-A3 Protein: Results of a Randomized Phase II Study of the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Melanoma Group in Metastatic Melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:2413–2420. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.43.7111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hsueh EC, Essner R, Foshag LJ, et al. Active immunotherapy by reinduction with a polyvalent allogeneic cell vaccine correlates with improved survival in recurrent metastatic melanoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2002;9:486–492. doi: 10.1007/BF02557273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morton DL, Mozzillo N, Thompson JF, et al. An international, randomized, phase III trial of bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG) plus allogeneic melanoma vaccine (MCV) or placebo after complete resection of melanoma metastatic to regional or distant sites. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2008;25:8508. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ikonopisov RL, Lewis MG, Hunter-Craig ID, et al. Autoimmunization with irradiated tumour cells in human malignant melanoma. Br Med J. 1970;2:752–754. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.5712.752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Deacon DH, Hogan KT, Swanson EM, et al. The use of gamma-irradiation and ultraviolet-irradiation in the preparation of human melanoma cells for use in autologous whole-cell vaccines. BMC Cancer. 2008;8:360. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-8-360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dillman RO, Cornforth AN, Depriest C, et al. Tumor stem cell antigens as consolidative active specific immunotherapy: a randomized phase II trial of dendritic cells versus tumor cells in patients with metastatic melanoma. J Immunother. 2012;35:641–649. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e31826f79c8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dillman RO, Fogel GB, Cornforth AN, et al. Features associated with survival in metastatic melanoma patients treated with patient-specific dendritic cell vaccines. Cancer Biother Radiopharm. 2011;26:407–415. doi: 10.1089/cbr.2011.0973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kirkwood JM, Strawderman MH, Ernstoff MS, et al. Interferon alfa-2b adjuvant therapy of high-risk resected cutaneous melanoma: the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Trial EST 1684. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:7–17. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.1.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kirkwood JM, Ibrahim JG, Sosman JA, et al. High-dose interferon alfa-2b significantly prolongs relapse-free and overall survival compared with the GM2-KLH/QS-21 vaccine in patients with resected stage IIB-III melanoma: results of intergroup trial E1694/S9512/C509801. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:2370–2380. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.9.2370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chapman PB. Counterpoint: The case against adjuvant high-dose interferon-alpha for melanoma patients. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2004;2:69–72. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2004.0005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dritschilo A, Mossman K, Gray M, et al. Potentiation of radiation injury by interferon. Am J Clin Oncol. 1982;5:79–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schmidberger H, Rave-Frank M, Lehmann J, et al. The combined effect of interferon beta and radiation on five human tumor cell lines and embryonal lung fibroblasts. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1999;43:405–412. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(98)00411-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chang AY, Keng PC. Potentiation of radiation cytotoxicity by recombinant interferons, a phenomenon associated with increased blockage at the G2-M phase of the cell cycle. Cancer Res. 1987;47:4338–4341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McDonald S, Rubin P, Chang AY, et al. Pulmonary changes induced by combined mouse beta-interferon (rMuIFN-beta) and irradiation in normal mice--toxic versus protective effects. Radiother Oncol. 1993;26:212–218. doi: 10.1016/0167-8140(93)90262-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hazard LJ, Sause WT, Noyes RD. Combined adjuvant radiation and interferon-alpha 2B therapy in high-risk melanoma patients: the potential for increased radiation toxicity. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2002;52:796–800. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(01)02700-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nguyen NP, Levinson B, Dutta S, et al. Concurrent interferon-alpha and radiation for head and neck melanoma. Melanoma Res. 2003;13:67–71. doi: 10.1097/00008390-200302000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Conill C, Jorcano S, Domingo-Domenech J, et al. Toxicity of combined treatment of adjuvant irradiation and interferon alpha2b in high-risk melanoma patients. Melanoma Res. 2007;17:304–309. doi: 10.1097/CMR.0b013e3282c3a6ed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gyorki DE, Ainslie J, Joon ML, et al. Concurrent adjuvant radiotherapy and interferon-alpha2b for resected high risk stage III melanoma -- a retrospective single centre study. Melanoma Res. 2004;14:223–230. doi: 10.1097/01.cmr.0000129375.14518.ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Finkelstein SE, Trotti A, Rao N, et al. The Florida Melanoma Trial I: A Prospective Multicenter Phase I/II Trial of Postoperative Hypofractionated Adjuvant Radiotherapy with Concurrent Interferon-Alfa-2b in the Treatment of Advanced Stage III Melanoma with Long-Term Toxicity Follow-Up. ISRN Immunology. 2012;2012:10. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Richtig E, Langmann G, Schlemmer G, et al. [Safety and efficacy of interferon alfa-2b in the adjuvant treatment of uveal melanoma]. Ophthalmologe. 2006;103:506–511. doi: 10.1007/s00347-006-1350-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lane AM, Egan KM, Harmon D, et al. Adjuvant interferon therapy for patients with uveal melanoma at high risk of metastasis. Ophthalmology. 2009;116:2206–2212. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.04.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Paul E, Muller I, Renner H, et al. Treatment of locoregional metastases of malignant melanomas with radiotherapy and intralesional beta-interferon injection. Melanoma Res. 2003;13:611–617. doi: 10.1097/01.cmr.0000056285.15046.ff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Atkins MB, Lotze MT, Dutcher JP, et al. High-dose recombinant interleukin 2 therapy for patients with metastatic melanoma: analysis of 270 patients treated between 1985 and 1993. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:2105–2116. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.7.2105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Safwat A, Aggerholm N, Roitt I, et al. Low-dose total body irradiation augments the therapeutic effect of interleukin-2 in a mouse model for metastatic malignant melanoma. J Exp Ther Oncol. 2003;3:161–168. doi: 10.1046/j.1359-4117.2003.01093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Safwat A, Aggerholm N, Roitt I, et al. Tumour burden and interleukin-2 dose affect the interaction between low-dose total body irradiation and interleukin 2. Eur J Cancer. 2004;40:1412–1417. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2004.01.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Safwat A, Schmidt H, Bastholt L, et al. A phase II trial of low-dose total body irradiation and subcutaneous interleukin-2 in metastatic melanoma. Radiother Oncol. 2005;77:143–147. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2005.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cameron RB, Spiess PJ, Rosenberg SA. Synergistic antitumor activity of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes, interleukin 2, and local tumor irradiation. Studies on the mechanism of action. J Exp Med. 1990;171:249–263. doi: 10.1084/jem.171.1.249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lange JR, Raubitschek AA, Pockaj BA, et al. A pilot study of the combination of interleukin-2-based immunotherapy and radiation therapy. J Immunother (1991) 1992;12:265–271. doi: 10.1097/00002371-199211000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Seung SK, Curti BD, Crittenden M, et al. Phase 1 study of stereotactic body radiotherapy and interleukin-2--tumor and immunological responses. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4:137ra174. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Okwan-Duodu D, Pollack BP, Lawson D, et al. Role of Radiation Therapy as Immune Activator in the Era of Modern Immunotherapy for Metastatic Malignant Melanoma. Am J Clin Oncol. 2013 doi: 10.1097/COC.0b013e3182940dc3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hodi FS, O'Day SJ, McDermott DF, et al. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:711–723. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1003466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Robert C, Thomas L, Bondarenko I, et al. Ipilimumab plus dacarbazine for previously untreated metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2517–2526. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1104621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Demaria S, Kawashima N, Yang AM, et al. Immune-mediated inhibition of metastases after treatment with local radiation and CTLA-4 blockade in a mouse model of breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:728–734. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pilones KA, Kawashima N, Yang AM, et al. Invariant natural killer T cells regulate breast cancer response to radiation and CTLA-4 blockade. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:597–606. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dewan MZ, Galloway AE, Kawashima N, et al. Fractionated but not single-dose radiotherapy induces an immune-mediated abscopal effect when combined with anti-CTLA-4 antibody. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:5379–5388. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Knisely JP, Yu JB, Flanigan J, et al. Radiosurgery for melanoma brain metastases in the ipilimumab era and the possibility of longer survival. J Neurosurg. 2012;117:227–233. doi: 10.3171/2012.5.JNS111929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mathew M, Tam M, Ott PA, et al. Ipilimumab in melanoma with limited brain metastases treated with stereotactic radiosurgery. Melanoma Res. 2013;23:191–195. doi: 10.1097/CMR.0b013e32835f3d90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kiess AP, Wolchok JD, Barker CA, et al. Ipilimumab and Stereotactic Radiosurgery for Melanoma Brain Metastases. International Journal of Radiation Oncology Biology Physics. 2012;84:S115–S116. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2015.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Du Four S, Wilgenhof S, Duerinck J, et al. Radiation necrosis of the brain in melanoma patients successfully treated with ipilimumab, three case studies. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48:3045–3051. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Muller-Brenne T, Rudolph B, Schmidberger H, et al. Successful Therapy of a cerebral metastasized malign Melanoma by Whole-Brain-Radiation and Therapy with Ipilimumab. Journal Der Deutschen Dermatologischen Gesellschaft. 2011;9:787–788. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bot I, Blank CU, Brandsma D. Clinical and radiological response of leptomeningeal melanoma after whole brain radiotherapy and ipilimumab. J Neurol. 2012;259:1976–1978. doi: 10.1007/s00415-012-6488-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Postow MA, Callahan MK, Barker CA, et al. Immunologic correlates of the abscopal effect in a patient with melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:925–931. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1112824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Stamell EF, Wolchok JD, Gnjatic S, et al. The abscopal effect associated with a systemic anti-melanoma immune response. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2013;85:293–295. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2012.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hiniker SM, Chen DS, Reddy S, et al. A systemic complete response of metastatic melanoma to local radiation and immunotherapy. Transl Oncol. 2012;5:404–407. doi: 10.1593/tlo.12280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Barker CA, Postow MA, Khan SA, et al. Concurrent radiotherapy and ipilimumab immunotherapy for patients with melanoma. Cancer Immunol Res. 2013 doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-13-0082. (e-pub ahead of print) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Topalian SL, Hodi FS, Brahmer JR, et al. Safety, activity, and immune correlates of anti-PD-1 antibody in cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2443–2454. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hamid O, Robert C, Daud A, et al. Safety and Tumor Responses with Lambrolizumab (Anti-PD-1) in Melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2013 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1305133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Liang H, Deng L, Chmura S, et al. Radiation-induced equilibrium is a balance between tumor cell proliferation and T cell-mediated killing. J Immunol. 2013;190:5874–5881. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1202612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zeng J, See AP, Phallen J, et al. Anti-PD-1 blockade and stereotactic radiation produce long-term survival in mice with intracranial gliomas. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2013;86:343–349. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2012.12.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Verbrugge I, Hagekyriakou J, Sharp LL, et al. Radiotherapy increases the permissiveness of established mammary tumors to rejection by immunomodulatory antibodies. Cancer Res. 2012;72:3163–3174. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-0210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Rosenberg SA, Yang JC, Sherry RM, et al. Durable complete responses in heavily pretreated patients with metastatic melanoma using T-cell transfer immunotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:4550–4557. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-0116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wrzesinski C, Paulos CM, Kaiser A, et al. Increased intensity lymphodepletion enhances tumor treatment efficacy of adoptively transferred tumor-specific T cells. J Immunother. 2010;33:1–7. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e3181b88ffc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Dudley ME, Yang JC, Sherry R, et al. Adoptive cell therapy for patients with metastatic melanoma: evaluation of intensive myeloablative chemoradiation preparative regimens. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:5233–5239. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.5449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Dudley ME, Gross CA, Langhan MM, et al. CD8+ enriched “young” tumor infiltrating lymphocytes can mediate regression of metastatic melanoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:6122–6131. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wolchok JD, Kluger H, Callahan MK, et al. Nivolumab plus Ipilimumab in Advanced Melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2013 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1302369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]