Abstract

The construction of mAb-producing cell lines has been instrumental in dissecting the fine specificities and genetic makeup of murine antibodies to exogenous and self Ag. The analysis of the genetic composition of human antibody responses has been hampered by the difficulty in generating human mAb of predetermined class and specificity. Using B lymphocytes from three healthy subjects vaccinated with inactivated rabies virus vaccine, we generated nine human mAb binding to rabies virus and analyzed the genes encoding their VH regions. Six mAb (five IgG1 and one IgA1) were monoreactive and displayed high affinities for rabies virus Ag. The remaining three mAb (IgM) were polyreactive and displayed lower affinities for rabies virus Ag. Seven mAb (3 IgG1, the IgA1, and the three IgM) utilized VH gene segments of the VHIII family. The remaining two IgG1 mAb utilized gene segments of the VHI and VHIV families. Of the seven expressed VHIII family genes, three were similar to the germline VH26c gene, two to the germline 22-2B gene, one to the germline H11 gene, and one to the germline 8-1B gene. The expressed VHI and VHIV genes displayed sequences similar to those of the germline hv1263 and V71-4 genes, respectively. The VH genes of all but one mAb (mAb55) resembled those that are predominantly expressed by Cμ+ clones in human fetal liver libraries. When compared with known germline sequences, the VH genes of the rabies virus-binding mAb displayed variable numbers of nucleotide differences. That such differences resulted from a process of somatic hypermutation was formally demonstrated (by analyzing DNA from polymorphonuclear neutrophil of the same subject whose B lymphocytes were used for the mAb generation) in the case of the VH gene of the high affinity (anti-rabies virus glycoprotein) IgG1 mAb57 that has been shown to efficiently neutralize the virus in vitro and in vivo. The distribution, mainly within the complementarity determining regions, and the high replacement-to-silent ratio of the mutations, were consistent with the hypothesis that the mAb57-producing cell clone underwent a process of Ag-driven affinity maturation through clonal selection. The D gene segments of the rabies virus-selected mAb were heterogeneous and, in most cases, flanked by significant N segment additions. The JH segment utilization was unbalanced and reminiscent of those of the adult and fetus. Four mAb utilized JH4, two JH6, two JH3, and one JH5; no mAb utilized JH1 or JH2 genes. The present data suggest that the adult human Ig V gene assortment expressed as the result of selection by a proteinic mosaic Ag is more restricted than previously assumed and resembles that of the putatively unselected adult B cell repertoire and the unselected Cμ+ cell repertoire of the fetus. They also document somatic Ig V gene hypermutation in human B cells producing high affinity antibodies.

Thorough knowledge of the clonal composition of specific murine antibody responses has been gained through the immunochemical and genetic analyses of mAb generated from animals injected with conjugated haptens, including 2-phenyl oxazolone (1, 2), phosphorylcholine (3–5), arsonate (6, 7), and NP6 (8–10), or infected with viruses, such as influenza virus (11–14). These studies have been made possible by the systematic application of the somatic cell hybridization technology introduced by Kohler and Milstein (15). Analysis of mAb-producing cell lines generated at different stages of the antibody responses established that: 1) dependent on the nature of the Ag, the dominant B cell clonotypes recruited in the primary response can “mature” throughout the secondary response or can be substituted with newly recruited and different clonotypes (1, 3, 7, 9); and 2) somatic hypermutation of V genes, particularly within the CDR, constitutes a powerful mechanism to finely tune antibody specificity by increasing affinity of the Ag-binding site (1–5, 7–14, 16, 17).

Because of the lack of similar human B cell technology, the cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying the antibody response in mice are merely inferred to be operative in humans. Recent progress, however, in the generation of human mAb-producing cell lines (18, 19) has allowed some insight into the clonal bases of the human antibody responses to self and exogenous Ag (20–29). For instance, we quantitated the circulating B cells committed to the production of antibodies to rabies virus and analyzed their phenotypes in healthy humans before and after vaccination with inactivated virus vaccine (25). Using EBV-transformed human B cells in concert with somatic cell hybridization techniques, we established cell lines secreting IgM, IgG, or IgA mAb to rabies virus, including mAb57, which efficiently neutralizes the virus in vitro and in vivo (25, 30).

In the present studies, we analyzed the VH genes utilized by these IgM, IgG, and IgA mAb to rabies virus. In addition, we analyzed the configuration with respect to somatic mutations of the gene encoding the VH segment of the virus-neutralizing IgG1 mAb57 by cloning and sequencing the corresponding germline VH gene from PMN DNA of the subject used as a source of B cells for the generation of this mAb. The selection of the VH genes by the low and high affinity mAb to rabies virus reflected that of the early and adult B cell repertoires. The nature and distribution of the somatic mutations in the virus-neutralizing mAb57 suggests that an Ag-driven affinity maturation process underlies the human high affinity response to exogenous Ag.

Materials and Methods

Generation of mAb-secreting cell lines

PBMC from subjects immunized with inactivated rabies virus vaccine were isolated, depleted of T cells, and infected with EBV (18–21). EBV-transformed B cells were selected for production of IgM, IgA, or IgG to rabies virus Ag by sequential subculturing. Selected EBV-transformed B cell blasts were stabilized by fusion with F3B6 cells, an Ig nonsecretor human-mouse heterohybridoma (18–21).

Cloning and sequencing of expressed Ig VH genes

mRNA was isolated from the established hybrid cell lines using the Fast Track mRNA isolation kit (Invitrogen, La Jolla, CA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. cDNA was synthesized from 5 μg of mRNA by a modified Gubler-Hoffman method (31). cDNA was complemented with NotI-EcoRI adaptors (Pharmacia LKB Biotechnology, Uppsala, Sweden) and ligated into the EcoRI site of λgt11 phage vector using T4 ligase. A cDNA library was constructed for each mAb-producing cell line (26). Each cDNA library was screened by filter hybridization using 32P-labeled DNA probes to the Ig VH and C regions (one probe for each VH gene family and one for each Ig class) of each mAb (26). In each case, after the second or third plating and screening, multiple plaques hybridizing with both the VH and C region probes were isolated. Each was suspended in 50 μl of distilled water and boiled for 15 min. The boiled phage suspension (10 μl) was subjected to PCR amplification using the forward and the reverse λgt11 primers (New England Biolab, Beverly, MA) and Taq polymerase (Perkin-Elmer Cetus, Norwalk, CT). Twenty-five cycles of amplification were performed. Each cycle consisted of a denaturing, an annealing, and an extension step at 94°C for 1 min, 55°C for 2 min, and 72°C for 3 min, respectively. The PCR-amplified material was fractionated on a 1% agarose gel containing 1 μg/ml ethidium bromide, and the DNA band of appropriate size was excised. The DNA fragment was purified, digested with EcoRI, and ligated into pUC18 vector, which was used to transform competent DH5α cells. Single colonies were amplified in culture, and the plasmid DNA was purified using Qiagen-Pack columns (Qiagen, Inc., Studio City, CA). Dideoxy sequencing was performed using double stranded plasmid DNA and the Taq sequencing kit (Promega, Madison, WI). Each mAb VH gene sequence was generated from the analysis of multiple independent clones, originally derived from at least three viral plaques. Differences in nucleotide sequences among the recombinant clones generated from the same mAb-producing cell line were observed in few cases (frequency, approximately 0.002/base). Such variants were excluded from the sequence analysis.

PCR amplification of genomic VH segments from PMN DNA and hybridoma DNA

Genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral blood PMN isolated from the subject used as the source of B cells for the generation of the mAb57-producing cell line. Genomic DNA was also extracted from the hybridoma cell line producing mAb57. DNA (100 ng) was supplemented with the appropriate 5′ and 3′ primers (10 pmol each). PCR was performed in a 50-μl reaction volume using Taq DNA polymerase under denaturing, annealing, and extension conditions similar to those described above, but for 30 cycles. The oligonucleotide primers used were as follows: 1) HI-6 encompassing a leader sequence (5′ CTGGAGGTTCCTCTTTGTGGT 3′) (residues −47 to −27 of cDNA) shared by the expressed mAb57 VH gene and its closest published germline VH gene, hv1263 (see Results); 2) HI-7 consisting of a sequence [5′ GCCGTGTCATCAGATCTCAGG 3′] complementary to the FR3 (residues 255 to 275) of the expressed mAb57 VH gene differing by a single base (A instead of C at position 9 of HI-7) from the hv1263 complementary sequence; and 3) 57CR1 consisting of a sequence [5′ CAACAGGTATACTGTCAACTG 3′] encompassing the 3′ end of FR1, the whole CDR1, and the 5′ region of FR2 (residues 87 to 107) of the expressed mAb57 VH gene. This sequence differs in five bases from that of hv1263. No sequence identical or highly homologous to 57CR1 was found in a database search. Precautions against cross-contamination of amplified material were taken according to the recommendations by Kwok et al. (32). To analyze the amplified VH DNA, the PCR products were fractionated on a 1.2% agarose gel containing 1 μg/ml of ethidium bromide. DNA was transferred to a filter membrane (Gene Screen, New England Nuclear Research Products, Boston, MA) and hybridized at 48°C, under the conditions recommended by manufacturer, with the 57CR1 oligonucleotide probe previously 32P-labeled using polynucleotide kinase (Promega, Madison, WI). After hybridization, the filter was washed twice with 2× SSC/0.5% SDS at room temperature for 30 min and twice with 1× SSC/0.5% SDS at 52°C for 30 min. The membrane was then exposed on Kodak XAR film (Eastman Kodak, Rochester, NY).

Cloning and sequencing of the germline VH segment that gave rise to the expressed mAb57 VH gene

The PCR-amplified material from PMN DNA using the HI-6 and HI-7 primers was used for cloning of the germline VH gene segment that putatively gave rise to the expressed mAb57 VH gene. The PCR-amplified DNA fragment was ligated into the pCR1000 plasmid vector (Invitrogen), and the recombinant vector used to transform competent INVαF′ cells (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Transformed cells were plated on Luria-Bertani agar containing 50 μg/ml kanamycin. The recombinant clones were selected according to the length of insert and sequenced as described above.

Analysis of DNA sequence data

DNA sequencing data were analyzed using the software package of the Genetics Computer Group of the University of Wisconsin, Release 6, and a model 6000-410 VAX computer (Digital Equipment Corp., Marlboro, MA). Homology searches of the expressed VH genes were performed using the GenBank database and the sequences published by Berman et al. (33).

Statistical analysis of VH gene utilization

The frequencies of VH family gene utilization were analyzed using the exact binomial distribution test. The complexity of each germline gene family was defined as reported in Table II.

Table II.

Complexity of the six human VH gene families and VH gene expression in the fetal and the adult B cell repertoires, in B cell leukemias, and in the responses to Haemophilus influenzae type b polysaccharide and rabies virus

| Origin | VH Gene Families and Numbers of Members (%)

|

Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VHI | VHII | VHIII | VHIV | VHV | VHVI | ||

| Genomica | |||||||

| Germline genes | 25 | 5 | 28 | 14 | 3 | 1 | 77 |

| Functional and pseudogenes | (32.5) | (6.5) | (36.3) | (18.2) | (3.9) | (1.3) | (100) |

| Germline genes | 13 | 5 | 15 | 14 | 2 | 1 | 50 |

| Functional genes only | (26.0) | (10.0) | (30.0) | (28.0) | (4.0) | (2.0) | (100) |

| Fetal liverb | 3* | 2 | 14* | 2* | 1 | 2 | 24 |

| [C μ+ clones] | (12.5) | (8.3) | (58.3) | (8.3) | (4.2) | (8.3) | (100) |

| Adult peripheral bloodc | 13*** | 1** | 57*** | 19 | 5 | 2 | 97 |

| [in vitro Ag nonselected B cells] | (13.4) | (1.0) | (58.8) | (19.6) | (5.1) | (2.1) | (100) |

| B cell leukemiasd | 16*** | 7 | 61* | 23 | 13** | 12** | 132 |

| (12.1) | (5.3) | (46.2) | (17.4) | (9.9) | (9.1) | (100) | |

| mAb to Haemophilus influenzae | 0 | 0 | 5** | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| Type b polysaccharidee | (0) | (0) | (100) | (0) | (0) | (0) | (100) |

| mAb to rabies virusf | 1 | 0 | 7** | 1 | 0 | 0 | 9 |

| (11.1) | (0) | (77.8) | (11.1) | (0) | (0) | (100) | |

The complexity of each VH family is based on the data by Walter et al. (62) and those reviewed by Pascual and Capra (70). Two different terms of comparison (expected frequencies of expression) are given: (1) total genes (functional and pseudogenes) (n = 77); and (2) functional genes only (n = 50). The proportion of pseudogenes is tentative and based on the data by Berman et al. (33), and those reviewed by Pascual and Capra (70). Total functional and pseudogenes include those (n = 76) reported by Walter et al. (62) plus the functional VHV gene VH32 (70). To test whether the frequency of expression of the different VH genes was stochastic in each sample (e.g., fetal liver C μ+ clones), statistical analysis (exact binomial distribution test) was performed. In each sample, the distribution of the expressed VH genes was compared with that expected on the basis of the total numbers (functional and pseudo, n = 77) (and family complexities) of genomic germline VH genes;

P < 0.05;

P < 0.01;

P < 0.001. Comparable p values were calculated when the statistical analysis was performed using the numbers of functional (n = 50) genes only as expected frequencies of expression.

Frequency of VH gene expression in fetal liver is based on analysis of C μ+ cDNA from days 104 and 130 fetuses (35, 46).

Frequency of VH gene expression of adult peripheral blood is based on the VH gene utilization by EBV-transformed B cell lines generated from adult PBMC, in the absence of any in vitro selection (59).

Number of B cell leukemia clones is a cumulative value of the data on acute lymphoblastic leukemia and chronic lymphocytic leukemia (59, 64).

Based on the study by Adderson et al. (63).

Present findings.

Results

Generation of rabies virus-binding mAb

Table I shows the nine mAb-producing cell lines, three IgM, five IgG1, and an IgA1 we generated from three unrelated healthy subjects immunized with inactivated rabies vaccine. The source, H chain isotypes, L chain types, and Ag-binding properties of the five mAb from subjects B and the three mAb from subject C have been reported previously (25). The IgG1 mAb107-producing cell line was generated for the purpose of these investigations using B cells from subject D and purified rabies virus glycoprotein as a selecting Ag. All five IgG1 (mAb53, mAb56, mAb57, mAb58, and mAb107) and the IgA1 (mAb105) mAb were monoreactive and displayed high affinities for rabies virus components (dissociation constant, 5.0 × 10−9 to 1.1 × 10−10 g/μl). The three IgM mAb (mAb52, mAb59, and mAb55) were polyreactive and displayed lower affinities for rabies virus Ag (dissociation constant, 1.0 to 1.2 × 10−6g/μl).

Table I.

VH, D, and JH gene composition of human mAb to rabies virus

| Clone | Sub- ject |

H, L Chains |

Reac- tivitya |

Dissociation Constant (g/μl) |

VH Gene Family |

Closest VH Member |

% Nucleotide Identity (Amino Acid)d |

No. of Nucleotide Differences (No. of Amino Acid Differences) |

Closest Segment |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Germline genomicb |

Fetal expressedc |

FR1 | CDR1 | FR2 | CDR2 | FR3 | Total in:

|

De | JH | ||||||||

| CDR | FR | ||||||||||||||||

| mAb59 | B | μ, λ | Poly [RNP] | 1.0 × 10−6 | VHIIIf | VH26c | 30p1 | 95.2 (90.8) | 3 (3) | 3 (2) | 1 (1) | 5 (2) | 2 (1) | 8 (4) | 6 (5) | D21/9 | JH4 |

| mAb53 | B | γ1, κ | Mono [M] | 1.2 × 10−9 | VHIII | VH26c | 30p1 | 98.0 (93.9) | 3 (3) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 2 (2) | 0 (0) | 3 (3) | 3 (3) | DLR2 | JH4 |

| mAb107 | D | γ1, λ | Mono [G] | 1.0 × 10−9 | VHIII | VH26c | 30p1 | 94.2 (90.8) | 1 (0) | 2 (2) | 1 (0) | 7 (4) | 6 (3) | 9 (6) | 8 (3) | DLR4 | JH3 |

| mAb52 | B | μ, κ | Poly [RNP] | 1.7 × 10−6 | VHIIIf | 22–2B | FL13–45 | 93.2 (91.8) | 7 (4) | 7 (3) | 3 (1) | 0 (0) | 3 (0) | 7 (3) | 13 (5) | DLR4 | JH6 |

| mAb105 | C | α1, κ | Mono [RNP] | 5.8 × 10−9 | VHIIIg | 22–2B | FL13–45 | 95.2 (92.9) | 2 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (0) | 5 (3) | 6 (3) | 5 (3) | 9 (4) | D21/10 | JH4 |

| mAb55 | C | μ, κ | Poly [RNP] | 1.0 × 10−6 | VHIIIi | H11 | ND | 96.9 (96.9) | 1 (1) | 2 (2) | 0 (0) | 4 (1) | 4 (1) | 6 (3) | 5 (2) | DXP’1 | JH6 |

| mAb56 | C | γ1h, λ | Mono [RNP] | 6.5 × 10−9 | VHIII | 8–1B | 60p2 | 94.5 (95.9) | 7 (2) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 3 (1) | 5 (0) | 4 (2) | 12 (2) | D21/10 | JH4 |

| mAb58 | B | γ1h, κ | Mono [G] | 5.0 × 10−9 | VHIV | V71–4 | 58p2 | 91.8 (83.5) | 6 (4) | 4 (2) | 0 (0) | 2 (2) | 12 (8) | 6 (4) | 18 (12) | DXP4 (inverted)i | JH3 |

| mAb57 | B | γ1h, λ | Mono [G] | 1.1 × 10−10 | VHI | hv1263 | 51p1 | 94.6 (86.7) | 2 (1) | 4 (4) | 0 (0) | 5 (4) | 5 (4) | 9 (8) | 7 (5) | DXP’1 | JH5 |

Reactivity: poly, polyreactive; mono, monoreactive; RNP, ribonucleoprotein; M, M protein; G, glycoprotein of rabies virus (25).

The complete sequences of the genomic germlines VH genes have been reported as follows: VH26c (34), 22–2B, (33), H11 (36), 8–1B (33), V71–4 (37), and hv1263 (38).

For complete sequences of the expressed fetal 30pl, 60p2, 58p2, and 51 pl VH genes, see Schroeder et al. (35). The expressed fetal FL 13–45 gene has been claimed by Raaphorst et al. (58) to be identical with the genomic 22–2B gene.

Compared with the germline genomic sequences.

D21/9 and D21/10 genes have been described by Buluwela et al. (41), and all other D genes have been reported in Refs. 39, 40, 42, and 43.

Previously reported as VHIIIb (25). The VHIIIb denomination has been since abandoned.

Previously reported as VHVI by Northern blot analysis (25).

mAb 56, 57, and 58 have been previously reported as γ2 by immunochemical analysis (25). The present isotypic attributions are based upon new immunochemical analysis using monoclonal reagents and the nucleotide sequence of the first 5′ portion of Cγ.

Part of the mAb58 D segment consists of the inverted sequence of DXP4.

VH segments of the rabies virus-binding mAb

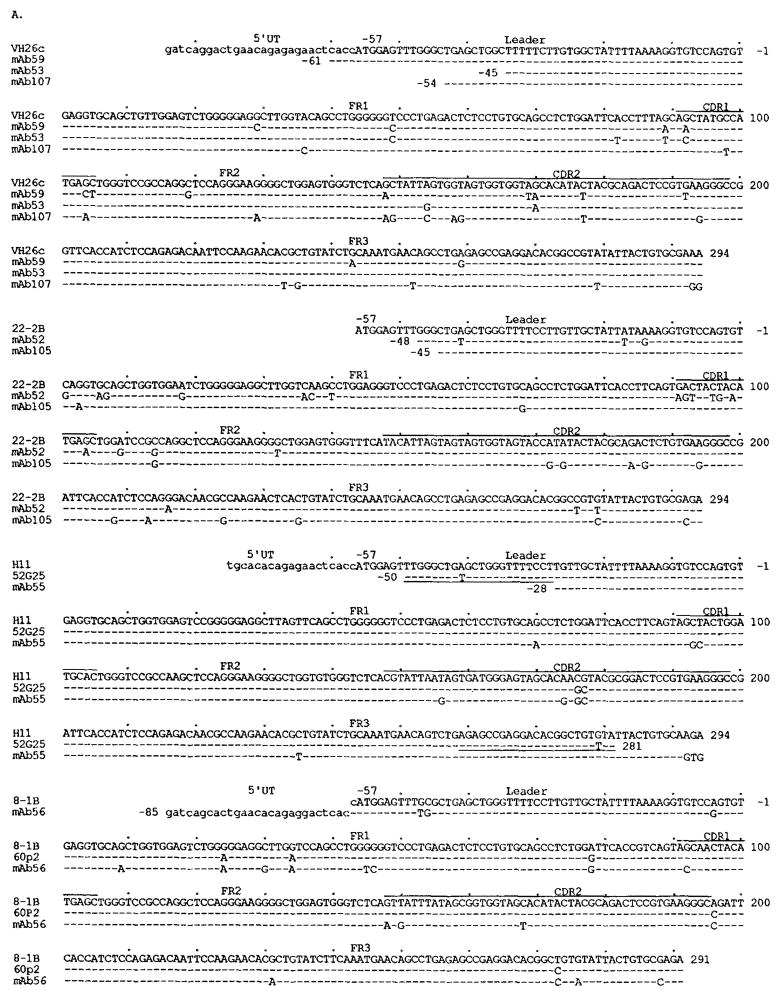

Figure 1 shows the nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequences of the VH segments of the nine mAb to rabies virus. The differences in nucleotide and predicted amino acid sequences when compared with the closest known germline VH genes are summarized in Table I. The mAb59 (IgM), mAb53 (IgG1), and mAb107 (IgG1) VH gene sequences displayed the highest degree of similarity (94.2 to 98%) to the germline VH26c gene (34), which is identical to the 30pl VH gene expressed in fetal liver (35). The nucleotide differences were mainly in the CDR, and many of them resulted in amino acid differences. The mAb52 (IgM) and mAb105 (IgA1) VH gene sequences displayed the highest degree of identity with the germline 22-2B gene (33). Nucleotide differences between mAb52 VH and 22-2B genes were mostly in the leader, the FR1, the CDR1, and the first part of FR2 (19 of 23). No amino acid differences were detected in the second half of FR2, the CDR2, or the FR3 (Fig. 1). In contrast, the nucleotide differences between the mAb105 VH and 22-2B genes were concentrated within the CDR2 and the FR3 (11 of 14). The three nucleotide differences in the FR1 and FR2 resulted in only one amino acid difference. Thus, the VH nucleotide and amino acid sequences of mAb52 and mAb105 were virtually identical to the 22-2B gene in their second and first halves, respectively. The mAb55 (IgM) VH gene sequence was 96.9 and 98.4% identical to the germline H11 (36) and 52G25 (H. Ikematsu, et al., manuscript in preparation) genes, respectively. The deduced amino acid sequence of the mAb55 VH region showed only two differences compared with that of the 52G25 gene. The mAb56 (IgG1) VH gene sequence displayed the highest degree of similarity to the germline 8-1B gene (33), the sequence of which is 98% identical with the 60p2 VH segment, a gene expressed in fetal liver (35). A variation in the deduced amino acid sequence of 60p2 from that of 8-1B was shared by the mAb56 VH deduced amino acid sequence, and only three differences were found between the mAb56 and 60p2 deduced amino acid sequences. The mAb58 (IgG1) VH gene sequence displayed the highest degree of identity when compared with the germline gene V71-4, a member of the VHIV family (37). The germline gene V71-4 is virtually identical (only two base differences) with the expressed 58p2 segment found in fetal liver (35). The degree of similarity between the mAb58 VH gene sequence and that of V71-4 was relatively low (92.1%). The nucleotide and amino acid differences were distributed throughout the VH segment. mAb57 is an IgG1 with a high affinity for rabies virus glycoprotein and virus-neutralizing activity in vivo and in vitro (25, 30). The mAb57 VH gene sequence was 94.6% identical with the germline hv1263 gene (38). The hv1263 gene is more than 94% identical with the “fetal” 51p1 (35). Comparison of the deduced amino acid sequences of hv1263 and mAb57 VH genes revealed that the vast majority of the differences were concentrated within the CDR.

FIGURE 1.

Nucleotide (A) and deduced amino acid (B) sequences of the VH genes utilized by the mAb binding to rabies virus. In each cluster, the top sequence is given for comparison and represents the published germline VH gene displaying the highest degree of identity to the expressed VH genes. The VH26c, 22-2B, H11, and 8-1B VH genes belong to the VHIII family. V71-4 and hv1263 are members of the VHIV and VHI gene families, respectively. Dashes indicate identities. Solid lines on the top of each cluster depict CDR. Small letters denote 5′ untranslated sequences (UT) and, in the case of hv1263 and 57GTA8, introns. 52G25 is an unpublished germline sequence (see text). 57GTA8 is the germline sequence we amplified from PMN DNA of the subject whose B cells were used for the generation of mAb57. The sequences or complementary sequences of the primers adopted for genomic VH gene amplification are underlined. 30p1, 60p2, 58p2, and 51p1 are VH genes expressed in fetal liver (35). Their nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequences are used for comparison. The present sequences are available from EMBL/GenBank/DDBJ under accession numbers L-08082, L-08083, L-08084, L-08085, L-08086, L-08087, L-08088, L-08089 and L-08090.

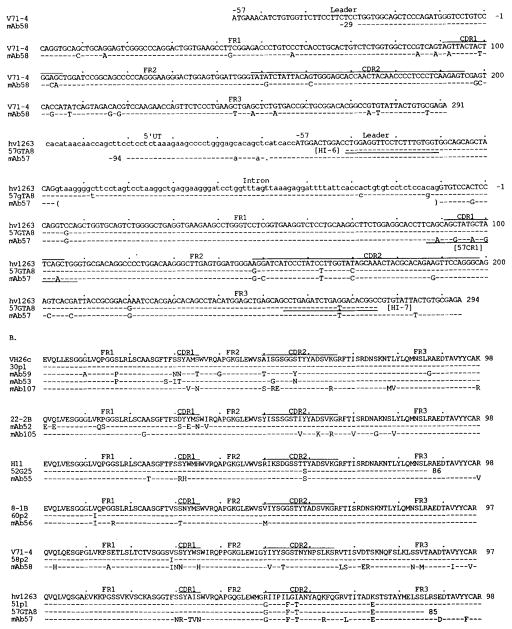

D segments of the rabies virus-binding mAb

The sequences of the expressed D segments were compared with those of the published germline D and DIR segments (39–43) using the “FASTA” program (44). Some sequence similarities between the expressed and germline D genes were found in most mAb (Table I). The structure of the D segments of mAb52, mAb53, mAb57, mAb105, and, perhaps, mAb56 and mAb107 may be explained by the conventional VH-D-JH rearrangement mechanisms complemented by N segment additions (Fig. 2A). The D segments of mAb59 and mAb55 were relatively long (55 and 66 nucleotides, respectively), although the stretches of identity to D21-9 and DXP’1 accounted for only 33 and 11% of their length, respectively (Fig. 2A). The remaining portions of these expressed D genes could not be accounted for by any known germline D segment sequences. The mAb58 D segment displayed a stretch of similarity to the complementary sequence of DXP4 and may have, therefore, resulted from an inverted D joining (45).

FIGURE 2.

Nucleotide (A) and deduced amino acid (B) sequences of the D and JH segments of the mAb binding to rabies virus. Germline D genes are given for comparison. Dashes indicate identities. Inverted DXP4 sequence is the reverse strand of the germline DXP4 sequence. The present sequences are available from EMBL/GenBank/DDBJ under accession numbers L-08082 through L-08090.

JH segments of the rabies virus-binding mAb

The expressed JH gene sequences were compared with those of the available human germline JH segments (Fig. 2, A and B). All four expressed JH4 segment sequences displayed an identical nucleotide variation from the germline JH4 gene sequence originally reported by Ravetch et al. (39). This variation has been previously reported in other expressed Ig genes (26, 35, 46) and is consistent with the prototypic JH4 sequence proposed by Yamada et al. (47). Two mAb, mAb52 and mAb55, utilized JH6 genes containing an identical variation from germline JH6 gene originally reported by Ravetch et al. (39). As in the case of the JH4 gene sequence, these two sequences agreed with the prototypic JH6 sequences reported by Yamada et al. (47). Finally, two antibodies, mAb58 and mAb107, utilized JH3 genes and mAb57 a JH5 gene.

Configuration of the mAb CDR3 regions

The predicted amino acid sequences of the D-JH segments of the nine mAb are depicted in Figure 2B. Each sequence is divided into CDR3 and FR4 stretches according to the method of Kabat et al. (48). The expressed CDR3 sequences were highly divergent and of highly variable lengths, ranging from 8 to 30 amino acids. The expressed FR4 sequences were invariable in length and displayed little diversity.

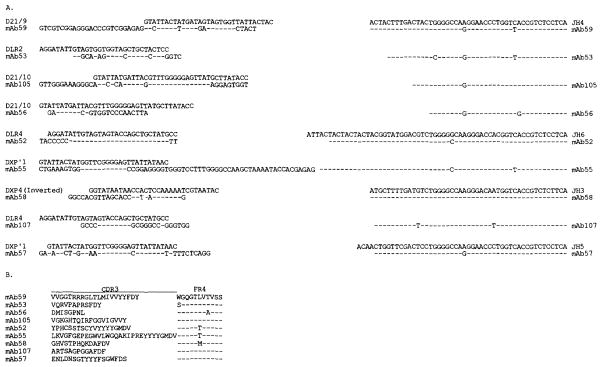

Somatic mutations in the expressed mAb57 VH gene

Because of the high Ag-binding affinity of mAb57 and of the distribution of nucleotide differences when compared with the hv1263 gene, we hypothesized that this expressed VH gene consisted of a somatically mutated form of the hv1263 or a hv1263-like gene. PCR amplifications were performed using selected oligonucleotide primers and the genomic DNA from autologous PMN or DNA from the mAb57-producing hybridoma cells. The sense primer, corresponding to the CDR1 of the mAb57 (57CR1), and differing in five nucleotides from the hv1263 gene, was used in conjunction with the antisense HI-7 primer, encompassing a stretch of FR3 sequence identical in the expressed mAb57 and the genomic hv1263 VH gene. The two combined primers amplified DNA from the hybridoma, but not from autologous PMN. The molecular size of the amplified product was consistent with that of the sequence spanning residues 87 to 275 (CDR1-FR3 portion) of the VH gene (Fig. 3A). This suggested that the expressed VH gene was somatically mutated. Utilization of the same antisense primer (HI-7) and the sense HI-6 primer encompassing a stretch of leader sequence, which was identical in the expressed mAb57 VH gene and in the hv1263 and related germline genes, resulted in VH gene amplification using DNA from both PMN and hybridoma cells. The amplified products were ~400 bp in size and consistent with the number of residues intervening between the HI-6 and HI-7 sequences in the mAb57 VH gene (Fig. 3B). This demonstrated that the failure to amplify any DNA from autologous PMN DNA in the first experiment was not due to flaws inherent to the DNA preparation. Southern blot analysis showed that the ~400-bp amplification product from the hybridoma, but not PMN, DNA hybridized with the 32P-labeled 57CR1 oligonucleotide probe (Fig. 3C). Thus, these experiments suggested that the expressed mAb57 VH gene constitutes a somatically mutated form of a germline hv1263-like gene.

FIGURE 3.

PCR analysis of somatic mutations in the expressed mAb57 VH gene. A, Ethidium bromide staining of amplified DNA fractionated in agarose gel electrophoresis (10 μl of reaction mixture were applied to each lane). Using the CDR1 (57CR1) and FR3 sequence (HI-7) oligonucleotide primers (see Materials and Methods), an amplification product of appropriate size (last 3′ portion of the VH segment, about 200 bp) was obtained by priming DNA from mAb57 B cells (hybridoma DNA) but not the DNA from autologous PMN (PMN DNA). B, Ethidium bromide staining of amplified DNA-fractionated in agarose gel electrophoresis (10 μl of reaction mixture were applied to each lane). Using the leader (HI-6) and FR3 (HI-7) sequence oligonucleotide primers (see Materials and Methods), amplification products of identical and appropriate size (about 400 bp) were obtained by priming DNA from both mAb57 B cells (hybridoma DNA) and autologous PMN (PMN DNA). C, Southern blot hybridization of the PCR products shown in B with the 32P-labeled oligonucleotide probe encompassing the CDR1 sequence of the expressed mAb57 VH gene (see Materials and Methods).

To analyze the autologous germline VH gene that putatively gave rise to the expressed mAb57 VH gene, the ~400-bp DNA amplified from PMN DNA (using the HI-6 and the HI-7 primers) was cloned. Twelve independent clones were sequenced: 1) Two clones contained an identical VH gene, termed 57GTA8. Throughout the overlapping area, the sequence of the 57GTA8 gene displayed 96.5%, about 99%, and absolute identity with those of the mAb57 VH gene, the germline hv1263 gene (Fig. 1A), and the 51p1 VH gene expressed in fetal liver, respectively. 2) Three clones contained VH genes whose sequences (data not shown) differed in only 1 or 2 bases from that of the 57GTA8 gene and displayed less than 96% identity with that of the mAb57 VH gene. 3) The remaining seven clones contained VH genes whose sequences (data not shown) differed from one other and the first five and displayed less than 93% identity with that of the mAb57 VH gene. Throughout the overlapping area, the 57GTA8 gene sequence shared 5 of the 14 the nucleotide differences found between the sequences of the mAb57 VH and hv1263 genes, supporting the hypothesis that 57GTA8 is the germline gene that gave rise to the mutated mAb57 VH gene. Of the 9 base differences displayed by this gene when compared with the germline 57GTA8 gene, six were in the CDR1 and CDR2 and one was immediately adjacent to the CDR1 (Fig. 1A). These seven nucleotide differences resulted in six amino acid replacements (Fig. 1B), yielding a R:S ratio of 6:1. The two nucleotide changes in the FR3 resulted in one amino acid replacement, yielding a R:S ratio of 1:1. The new polarity and charge conferred to the mutated VH region compared with those of the deduced amino acid sequence of the corresponding germline VH gene are summarized in Table III.

Table III.

Somatic changes in the mAb57 VH deduced amino acid sequence when compared with the germline 57CTA8 gene

| Region | Nucleotide Mutations

|

Amino Acid Mutations

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | R | R:S | Residue no. | Germline (57GTA8) | Expressed VH (mAb57) | ||||

| FR1 | 1a | 1 | 1:0 | 30 | S | [U][polar, OH]b | > | N | [U][polar, NH2] |

| CDR1 | 4 | 4 | 4:0 | 31 | S | [U][polar, OH] | > | R | [Very basic, NH2+] |

| 33 | A | [U][nonpolar] | > | T | [U][polar, OH] | ||||

| 34 | I | [U][nonpolar] | > | V | [U][nonpolar] | ||||

| 35 | S | [U][polar, OH] | > | N | [U][polar, NH2] | ||||

| CDR2 | 2 | 1 | 1:1 | 50 | G | > | G | No mutation | |

| 63 | K | [Basic, NH3+] | > | R | [Very basic, NH2+] | ||||

| Total CDR + FR1 | 7 | 6 | 6:1 | ||||||

| FR3 | 2 | 1 | 1:1 | 68 | V | [U][nonpolar] | > | L | [U][nonpolar] |

| 69 | T | > | T | No mutation | |||||

FR1 mutation immediately adjacent to CDR1 (see Results).

Amino acid features; U, uncharged; OH or NH2, polar groups.

Discussion

We analyzed the genes encoding the VH regions of nine human mAb we generated, by selection for binding to rabies virus Ag, using B cells from three healthy subjects who had been immunized with inactivated rabies virus vaccine. We found the following: 1) Seven mAb utilized genes of the VHIII family. In particular genes similar or identical to two members of this family, VH26c and 22-2B, were used five times. 2) Most of the VH genes utilized by both the low and high affinity mAb were similar to those found to be predominantly expressed in fetal liver and in the putatively unselected adult human B cell repertoire. 3) By isolating and sequencing of the autologous germline segment that gave rise to the expressed gene, we formally proved that the gene encoding the VH region of the high affinity virus-neutralizing mAb57 displayed a number of somatic point mutations distributed in a fashion and with features characteristic of those resulting from a process of Ag-driven affinity maturation through somatic hypermutation and selection.

In the mouse, the VH genes of families proximal to D and JH loci are preferentially rearranged at early stages of life (49–53). The simplest interpretation of this phenomenon is that the recombinatorial machinery “tracks” upstream from the D-JH complex to recruit VH segments (49). Later in the life of the animal, VH gene expression is thought to normalize, that is, VH genes of all different families are expressed at frequencies proportional to the complexity of each family and its representation in the haploid genome (stochastic expression) (54–56). Hypothesized mechanisms for the normalization of VH gene usage in adult animals include programmed changes in the generation of the primary repertoire and selection forces that operate subsequent to the generation of B cells in the primary lymphoid organs.

In humans, preferential expression of VHV and VHVI genes, located most proximal to the D and JH loci on chromosome 14, have been reported at a very early stage of fetal life (day 50) (57). However, later in gestation (days 104 and 130), the VHVI gene is expressed by only 8% of the total human liver Cμ+ cDNA clones (35, 46), and instead, genes of the VHIII family are predominantly expressed (58% of all Cμ+ cDNA clones) (Table II), in particular, only three to six of a total of about 30 members (35, 46, 58). These include 30pl, 60p2, and FL13-45, the equivalents of the germline VH26c, 8-1B, and 22-2B genes, respectively. A very limited number of VH genes belonging to families other than VHIII are also expressed recurrently in the fetal liver, including 51pl and 58p2, the equivalents of the germline hv 1263 and V71-4 genes, respectively (35, 46). Although without knowledge of the complete repertoire of VH genes the identification of the germline origin VH cDNA sequences is still tentative, it is intriguing that among the nine rabies virus-selected mAb, 30pl-like genes were used three times (mAb53, mAb59, and mAb107), FL13-45-like genes were used twice (mAb52 and mAb105), and 60p2-, 58p2-, and 51pl-like genes were each used once (mAb56, mAb58, and mAb57, respectively) (Table I). Thus, a high frequency of expression of VHIII family genes at large and/or selected VHIII genes may be a general feature of not only the fetal but also the adult B cell repertoire. This speculation would be further supported by the significant overutilization of these VH genes by: 1) the putatively unselected B PBL (59–61) (Table II); 2) the antibodies produced in response to Haemophilus influenzae type b of polysaccharide, an Ag different in nature from those on rabies virus (63) (Table II); 3) a large sample of leukemic B cells (59, 64) (Table II); and 4) autoantibodies to various self Ag generated in healthy subjects and autoimmune patients (65–71) (Kasaian et al. and Ikematsu et al., manuscripts in preparation).

High frequency of expression of VHIII genes throughout ontogeny may reflect a pivotal role of this VH family in phylogeny, at least in vertebrates (72). Both birds and rabbits have multiple VH genes, but all are VHIII-like. VHIII-like elements might have been positively selected during phylogeny in response to Ag shared by common pathogens. The present experiments corroborate this view and suggest that the “functional” human VH gene repertoire is smaller than assumed previously. As hypothesized by Chen (73), it is plausible that at least some of the most frequently expressed VH genes display recognition signal-like sequences that make them inherently more recruitable for rearrangement. The mechanisms of such putatively inherent high susceptibility to rearrangement are now under investigation in our laboratory.

Positive selection of cell clones displaying somatic point mutations that yield a net increase in binding strength of the surface receptor for Ag has been shown to be the primary mechanism underlying the affinity maturation process in the course of a specific antibody response. Somatic point mutations appear in antibody VH and VL segments during the late stages of the primary response and accumulate at higher frequency throughout the secondary response (1–5, 7–17). They distribute preferentially within the CDR of the VH and/or VL chains, inasmuch as these segments play a primary role in Ag capture. For example, the antibodies predominant in the secondary response to the hapten NP shared identical somatic mutations in the VH CDR1, namely a W instead of an L in position 33. As shown by site-directed mutagenesis experiments, such W is crucial in NP binding (74). Information concerning the somatically mutated status of Ig V genes in mice of a given inbred strain can be readily derived from comparison of the expressed V gene sequences with the corresponding germline V gene sequences characteristic of the strain. Because of the outbreeding of the human population and the high degree of V gene polymorphism, the formal assessment of the somatically mutated status of an expressed VH segment requires the identification of the germline gene that gave rise to it. We used this approach to determine that the rabies virus-neutralizing mAb57 VH gene is significantly point-mutated. Consistent with their Ag-dependent selection (1, 4, 9, 10, 11, 16, 17, 75, 76), the somatic point mutations within coding regions: 1) were highly concentrated in the CDR or immediately adjacent residues (seven of nine) (Fig. 1, A and B); and 2) displayed a characteristically high R:S mutation ratio. This resulted in the acquisition of a more positive charge by the mAb57 VH segment when compared with the deduced amino acid sequence of the corresponding germline VH gene (Table III). A thorough evaluation, however, of the contribution of these changes to the overall properties of the mAb57 Ag-binding site must take into account also the configuration of the VL segment. The mAb57 VH CDR and FR R:S mutation ratio values (6:1 and 1:1, respectively) are comparable to those of the V genes of high affinity murine antibodies and autoantibodies (1, 4, 16, 71, 75, 76), and are significantly higher and lower, respectively, than the theoretical R:S value, ~2.9, calculated for somatic mutations occurring randomly in a gene encoding a protein that need not be preserved in structure (77). Whereas high CDR R:S mutation ratios reflect the positive selective pressures applied by Ag on the gene products that come in close contact with Ag, low FR R:S mutation ratios reflect the negative pressure for mutant selection applied to structural components that need to be conserved.

It seems likely that, similar to the mAb57 VH gene, the genes encoding the VH regions of the monoreactive high affinity mAb53 and mAb107 constitute somatically mutated forms of VH26c or VH26c-like genes, although the possibility that they represent the expression of yet-to-be-characterized germline genes cannot be ruled out. A similar consideration applies to the VH segment of the monoreactive high affinity mAb56 to rabies virus ribonucleoprotein. This segment likely represents a somatically mutated form of the 60p2 gene, the “fetal” expressed homologue to the germline 8-1B gene, as suggested by the distribution within the CDR of two of the three differences displayed by the mAb56 VH gene when compared with 60p2. Finally, considering the very limited polymorphism of the VHIV family members (70), the extensive differences between the mAb58 VH gene and the germline V71-4 segment suggest that the mAb58 VH segment resulted from the expression of a still-uncharacterized VHIV gene.

As for the VH segments of two of the rabies virus-binding polyreactive IgM, mAb59 and mAb55, they may be encoded in (still unidentified) germline VH26c- and H11-like genes, respectively, or in somatically mutated VH genes, as a result of selection by Ag, possibly other than those borne on rabies virus. The latter hypothesis would imply that, in an originally polyreactive antibody, positive selection of somatic mutations by a given Ag is not necessarily associated with loss of the antibody ability to bind different and multiple Ag. It would also support the speculation that, in a polyreactive antibody, different Fab structures can mediate the binding to different Ag. As recently suggested by Foote and Milstein (78), a precise evaluation of the contribution of different structures and/or superimposed somatic mutations to the overall Fab site binding strength for a given Ag cannot be based only on the measurement of antibody affinity, which is relevant only at equilibrium, but must include the analysis of the on-rate constant.

The exclusive concentration of the nucleotide differences within the first half of the sequence (nucleotides 1 through 132) of the VH gene of the third IgM (mAb52) when compared with the 22-2B germline gene, can be consistent with the hypothesis that this expressed gene arose from a recombinatorial event by which the first half of a 22-2B or 22-2B-like gene was substituted with a sequence from a donor germline VH gene or pseudogene segment. Our preliminary findings suggest that such recombinatorial events (possibly gene conversion) may be frequent during phylogeny and/or ontogeny (H. Ikematsu et al., manuscript in preparation). The clustered nucleotide differences in the second half of the mAb105 VH gene compared with the germline 22-2B VH gene sequence suggest that this expressed segment may also represent an example of such a recombinatorial event.

The sequences of the D segments expressed by our panel of mAb were heterogeneous. Their compositions, however, were similar to those of the D gene segments of other human mAb of different classes and specificities, and to those of the D segments expressed by “unselected” adult B PBL (47, 60, 79). The predominant JH4 and, to a lesser extent, JH6 gene utilization by the mAb to rabies virus was similar to that of human natural and Ag-induced mAb selected in vitro for binding to a variety of self and exogenous Ag (26, 70, 80, 81), as well as to the JH utilization of the “unselected” adult and fetal B cell repertoires (47, 35, 46, 60, 79). In no case, however, did the rabies virus-selected mAb utilize the JH-proximal DHQ52 D gene, which is frequently expressed by Cμ+ cells in fetal life (35, 46). Also, in contrast with the relatively short VH-D-JH junction sequences (CDR3) of the fetal B cell repertoire (46), most mAb to rabies virus VH-D-JH junction sequences displayed significant N segment additions. This suggests that a developmentally regulated shift in the clonal composition of the human B cell repertoire occurs at some point during ontogeny. Such a shift may be due to the presence of different mechanisms operating in VH-D-JH joining and/or terminal segment additions at sequential stages of ontogeny and, perhaps, in different B cell types. Analysis of these mechanisms and underlying enzymatic activities should further our understanding of the developmental dynamics of the human B cell repertoire and, perhaps, lay the basis for targeted immune intervention.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. J. Donald Capra for advice and encouragement. We thank Dr. Anne L. Jaquotte for her help with statistical analysis, Dr. Harry W. Schroeder for stimulating discussions, and Dr. Bernard Dietzschold and Dr. Hilary Koprowski for the preparation of purified rabies virus and virus gp originally used for the generation of the mAb-producing cell lines (25).

Footnotes

This work was supported by United States Public Health Service Grants AR-40908 and CA-16087. The contribution of The Lila Motley Cancer Fund is gratefully acknowledged. This is publication 12 from The Jeanette Greenspan Laboratory for Cancer Research. Some of the data contained in this paper have been presented at the New York Academy of Sciences conference on CD5 B Cells in Development and Disease held in Palm Beach, FL, June 3 to 6, 1991.

Abbreviations used in this paper: NP, 4-hydroxyl-3-nitrophenyl acetyl; CDR, complementarity determining region; FR, framework region; R:S, replacement to silent mutation ratio; PMN, polymorphonuclear neutrophil; PCR, polymerase chain reaction

References

- 1.Berek C, Milstein C. Mutation drift and repertoire shift in the maturation of the immune response. Immunol Rev. 1987;96:23. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1987.tb00507.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Apel M, Berek C. Somatic mutations in antibodies expressed by germinal centre B cells early after primary immunization. Int Immunol. 1990;2:813. doi: 10.1093/intimm/2.9.813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Malipiero UV, Levy NS, Gearhart PJ. Somatic mutation in anti-phosphorylcholine antibodies. Immunol Rev. 1987;96:59. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1987.tb00509.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Levy NS, Malipiero UV, Lebecque SG, Gearhart PJ. Early onset of somatic mutation in immunoglobulin VH genes during the primary immune response. J Exp Med. 1989;169:2007. doi: 10.1084/jem.169.6.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Claflin JL, Berry J, Flaherty D, Dunnick W. Somatic evolution of diversity among anti-phosphocholine antibodies induced with Proteus morganii. J Immunol. 1987;138:3060. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Slaughter CA, Capra DJ. Amino acid sequence diversity within the family of antibodies bearing the major antiarsonate cross-reactive idiotype of the A strain mouse. J Exp Med. 1983;158:1615. doi: 10.1084/jem.158.5.1615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wysocki L, Manser T, Gefter ML. Somatic evolution of variable region structures during an immune response. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:1847. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.6.1847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Siekevitz M, Kocks C, Rajewsky K, Dildrop R. Analysis of somatic mutation and class switching in naive and memory B cells. Cell. 1987;48:757. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90073-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rajewsky K, Forster I, Cumano A. Evolutionary and somatic selection of antibody repertoire in the mouse. Science. 1987;238:1088. doi: 10.1126/science.3317826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weiss U, Rajewsky K. The repertoire of somatic antibody mutants accumulating in the memory compartment after primary immunization is restricted through affinity maturation and mirrors that expressed in the secondary response. J Exp Med. 1990;172:1681. doi: 10.1084/jem.172.6.1681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McKean D, Huppi K, Bell M, Staudt L, Gerhard W, Weigert MG. Generation of antibody diversity in the immune response of Balb/c mice to influenza virus hemagglutinin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:3180. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.10.3180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clarke HS, Huppi K, Ruezinsky D, Staudt L, Gerhard W, Weigert MG. Inter- and intraclonal diversity in the antibody response to influenza hemagglutinin. J Exp Med. 1985;161:687. doi: 10.1084/jem.161.4.687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clarke SH, Staudt LM, Kavaler J, Schwartz D, Gerhard W, Weigert MG. V region gene usage and somatic mutation in the primary and secondary responses to influenza virus hemagglutinin. J Immunol. 1990;144:2795. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Caton AJ, Stark SE, Kavaler J, Staudt LM, Schwartz D, Gerhard W. Many variable region genes are utilized in the antibody response of BALB/c mice to the influenza virus A/PR/8/34 hemagglutinin. J Immunol. 1991;147:1675. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kohler G, Milstein C. Continuous cultures of fused cells secreting antibody of predefined specificity. Nature. 1975;256:495. doi: 10.1038/256495a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weigert MG. The influence of somatic mutation on the immune response. In: Cinader B, Miller RG, editors. Progress in Immunology VI. Academic Press, Inc; New York: 1986. pp. 138–144. [Google Scholar]

- 17.French DL, Laskov R, Scharff MD. The role of somatic hypermutation in the generation of antibody diversity. Science. 1989;244:1152. doi: 10.1126/science.2658060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Larrick JW, Chiang YL, Sheng-Dong R, Senyk G, Casali P. Generation of specific monoclonal antibodies by in vitro expansion of human B cells. A novel recombinant DNA approach. In: Borrebaek CAK, editor. In Vitro Immunization in Hybridoma Technology. Elsevier Science Publishing B. V; Amsterdam: 1988. pp. 231–246. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ikematsu H, I, Goldfarb S, Harindranath N, Kasaian MT, Casali P. Generation of human monoclonal antibody-producing cell lines by Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) transformation of B lymphocytes and somatic cell hybridization techniques. J Tissue Cult Methods. 1992;14:9. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nakamura M, Burastero SE, Notkins AL, Casali P. Human monoclonal rheumatoid factor-like antibodies from CD5 (Leu-1)+ B cells are polyreactive. J Immunol. 1988;140:4180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nakamura M, Burastero SE, Ueki Y, Larrick JW, Notkins AL, Casali P. Probing the normal and autoimmune B cell repertoire with Epstein-Barr virus. Frequency of B cells producing monoreactive high affinity autoantibodies in patients with Hashimoto’s disease and systemic lupus erythematosus. J Immunol. 1988;141:4165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Casali P, Notkins AL. Probing the human B-cell repertoire with EBV: polyreactive antibodies and CD5+ B lymphocytes. Ann Rev Immunol. 1989;7:513. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.07.040189.002501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Casali P, Burastero SE, Balow JE, Notkins AL. High affinity antibodies to ssDNA are produced by CD5− B cells in systemic lupus erythematosus patients. J Immunol. 1989;143:3476. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Casali P, Nakamura M, Ginsberg-Fellner F, Notkins AL. Frequency of B cells committed to the production of antibodies to insulin in newly diagnosed patients with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus and generation of high affinity human monoclonal IgG to insulin. J Immunol. 1990;144:3741. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ueki Y, I, Goldfarb S, Harindranath N, Gore M, Koprowski H, Notkins AL, Casali P. Clonal analysis of a human antibody response: quantitation of precursors of antibody-producing cells and generation and characterization of monoclonal IgM, IgG, and IgA to rabies virus. J Exp Med. 1990;171:19. doi: 10.1084/jem.171.1.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harindranath N, I, Goldfarb S, Ikematsu H, Burastero SE, Wilder RL, Notkins AL, Casali P. Complete sequence of the genes encoding the VH and VL regions of low and high affinity monoclonal IgM and IgA1 rheumatoid factors produced by CD5+ B cells from a rheumatoid arthritis patient. Int Immunol. 1991;3:865. doi: 10.1093/intimm/3.9.865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kasaian MT, Ikematsu H, Casali P. Identification and analysis of a novel CD5− B lymphocyte subset producing natural antibodies. J Immunol. 1992;148:2690. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Williams RC, Jr, Malone CC, Casali P. Heteroclitic polyclonal and monoclonal anti-Gm(a) and anti-Gm(g) rheumatoid factors react with epitopes induced in Gm(a-), Gm(g-) IgG by interaction with antigen or by nonspecific aggregation. A possible mechanism for the in vivo generation of rheumatoid factors. J Immunol. 1992;149:1817. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Casali P, Kasaian MT, Haughton G. B-1 (CD5 B) cells. In: Coutinho A, Kazatchkine MD, editors. Autoimmunity. John Wiley-Liss; New York: 1993. In press. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dietzschold B, Gore M, Casali P, Ueki Y, Rupprecht CE, Notkins AL, Koprowski H. Biological characterization of human monoclonal antibodies to rabies virus. J Virol. 1990;64:3087. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.6.3087-3090.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gubler U, Hoffman BJ. A simple and very efficient method for generating cDNA libraries. Gene. 1983;25:263. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(83)90230-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kwok S, Mack DH, Kellogg DN, McKinney N, Faloona F, Sninsky JJ. Application of the polymerase chain reaction to detection of human retroviruses. In: Erlich HA, Gibbs R, Kazazian HH Jr, editors. Polymerase chain reaction. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; Cold Spring Harbor, NY: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Berman JE, Mellis SJ, Pollock R, Smith CL, Suh H, Heinke B, Kowal C, Surti U, Chess L, Cantor CR, Alt FW. Content and organization of the human Ig VH locus: definition of three new VH families and linkage to the Ig CH locus. EMBO J. 1988;7:727. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb02869.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen PP, Liu MF, Sinha S, Carson DA. A 16/6 idiotype-positive anti-DNA antibody is encoded by a conserved VH gene with no somatic mutation. Arthritis Rheum. 1988;31:1429. doi: 10.1002/art.1780311113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schroeder HW, Jr, Hillson JL, Perlmutter RM. Early restriction of the human antibody repertoire. Science. 1987;238:791. doi: 10.1126/science.3118465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rechavi G, Bienz B, Ram D, Ben-Neriah Y, Cohen JB, Zakut R, Givol D. Organization and evolution of immunoglobulin VH gene subgroups. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1982;79:4405. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.14.4405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee KH, Matsuda F, Kinashi T, Kodaira M, Honjo T. A novel family of variable region genes of the human immunoglobulin heavy chain. J Mol Biol. 1987;195:761. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(87)90482-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen PP, Liu MF, Glass CA, Sinha S, Kipps TJ, Carson DA. Characterization of two immunoglobulin VH genes that are homologous to human rheumatoid factors. Arthritis Rheum. 1989;32:72. doi: 10.1002/anr.1780320112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ravetch JV, Siebenlist U, Korsmeyer S, Waldmann T, Leder P. Structure of the human immunoglobulin μ locus: characterization of embryonic and rearranged J and D genes. Cell. 1981;27:583. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90400-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Siebenlist U, Ravetch JV, Korsmeyer S, Waldmann T, Leder P. Human immunoglobulin D segments encoded in tandem multigenic families. Nature. 1981;294:631. doi: 10.1038/294631a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Buluwela L, Albertson DG, Sherrington P, Rabbitts PH, Spurr N, Rabbitts TH. The use of chromosomal translocations to study human immunoglobulin gene organization: mapping DH segments within 35 kb of the Cμ gene and identification of a new DH locus. EMBO J. 1988;7:2003. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb03039.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Matsuda F, Lee KH, Nakai S, Sato T, Kodaira M, Zong SQ, Ohno H, Fukahara S, Honjo T. Dispersed localization of D segments in the human immunoglobulin heavy-chain locus. EMBO J. 1988;7:1047. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb02912.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ichihara Y, Matsuoka H, Kurosawa Y. Organization of human immunoglobulin heavy chain diversity gene loci. EMBO J. 1988;7:4141. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb03309.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pearson WR. Rapid and sensitive sequence comparison with FASTP and FASTA. Methods Enzymol. 1990;183:63. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)83007-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Meek KD, Hasemann CA, Capra JD. Novel rearrangements at the immunoglobulin D locus. Inversion and fusion add to IgH somatic diversity. J Exp Med. 1989;170:39. doi: 10.1084/jem.170.1.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schroeder HW, Jr, Wang JY. Preferential utilization of conserved immunoglobulin heavy chain variable gene segments during human fetal life. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:6146. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.16.6146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yamada M, Wasserman R, Reichard BA, Shane S, Caton AJ, Rovera G. Preferential utilization of specific immunoglobulin heavy chain diversity and joining segments in adult human peripheral blood B lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 1991;173:395. doi: 10.1084/jem.173.2.395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kabat EA, Wu TT, Perry HM, Gottesman KS, Foeller C. Sequences of Proteins of Immunological Interest. 4. United States Department of Health and Human Services; Washington, DC: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yancopoulos GD, Desiderio SV, Paskind M, Kearney JF, Baltimore D, Alt FW. Preferential utilization of the most JH proximal VH gene segment in pre-B-cell lines. Nature. 1984;311:727. doi: 10.1038/311727a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Perlmutter RM, Kearney JF, Chang SP, Hood LE. Developmentally controlled expression of immunoglobulin VH gene. Science. 1985;227:1597. doi: 10.1126/science.3975629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Reth MG, Jackson J, Alt FW. VH-D-JH replacement during pre-B differentiation: non-random usage of gene segments. EMBO J. 1986;5:2131. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04476.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yancopoulos GD, Malynn BA, Alt FW. Developmentally regulated and strain-specific expression of murine VH gene family. J Exp Med. 1988;168:417. doi: 10.1084/jem.168.1.417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Malynn BA, Yancopoulos GD, Barth JE, Bona C, Alt FW. Biased expression of JH proximal VH genes occurs in the newly generated repertoire of neonatal and adult mice. J Exp Med. 1990;171:843. doi: 10.1084/jem.171.3.843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schulze DH, Kelsoe G. Genotypic analysis of B cell colonies by in situ hybridization. Stoichiometric expression of three VH families in adult C57BL/6 and B ALB/c mice. J Exp Med. 1987;166:163. doi: 10.1084/jem.166.1.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jeong HD, Teale JM. Comparison of the fetal and adult functional B cell repertoires by analysis of VH gene family expression. J Exp Med. 1988;168:589. doi: 10.1084/jem.168.2.589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jeong HD, Teale JM. VH gene family repertoire of resting B cells. J Immunol. 1989;143:2752. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cuisinier A-M, Guigou V, Boubli L, Fourgereau M, Tonnelle C. Preferential expression of VH5 and VH6 immunoglobulin genes in early human B-cell ontogeny. Scand J Immunol. 1989;30:493. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.1989.tb02455.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Raaphorst FM, Timmers E, Kenter MJH, Van Tol MJD, Vossen JM, Schuurman RKB. Restricted utilization of germ-line VH3 genes and short diverse third complementarity-determining region in human fetal B lymphocyte immunoglobulin heavy chain rearrangements. Eur J Immunol. 1992;22:247. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830220136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mayer R, Logtenberg T, Strauchen J, Dimitriu-Bona A, Mayer L, Mechanic S, Chiorazzi N, Borche L, Dighiero G, Mannheimer-Lory A, Diamond B, Alt F, Bona CA. CD5 and immunoglobulin V gene expression in B-cell lymphomas and chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 1990;75:1518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Huang C, Styewart AK, Schwartz RS, Stollar BD. Immunoglobulin heavy chain expression in peripheral blood B lymphocytes. J Clin Invest. 1992;89:1331. doi: 10.1172/JCI115719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Braun J, Berberian L, King L, Sanz I, Gowan HL. Restricted use of fetal VH3 immunoglobulin genes by unselected B cells in the adult. Predominance of 56pl-like VH genes in common variable immunodeficiency. J Clin Invest. 1992;89:1395. doi: 10.1172/JCI115728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Walter MA, Surti U, Hofker MH, Cox DW. The physical organization of the human imunoglobulin heavy chain gene complex. EMBO J. 1990;9:3303. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb07530.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Adderson EE, Shackelford PG, Quinn A, Caroll WL. Restricted Ig H chain V gene usage in the human antibody response to Haemophilus influenzae type b capsular polysaccharide. J Immunol. 1991;147:1667. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Deane M, Norton JD. Immunoglobulin heavy chain variable region family usage is independent of tumor cell phenotype in human B lineage leukemias. Eur J Immunol. 1990;20:2209. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830201009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dersimonian H, Schwartz RS, Barrett KJ, Stollar BD. Relationship of human variable region heavy chain germ-line genes to genes encoding anti-DNA autoantibodies. J Immunol. 1987;139:2496. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dersimonian H, McAdam KPWJ, Mackworth-Young C, Stollar BD. The recurrent expression of variable region segments in human IgM anti-DNA autoantibodies. J Immunol. 1989;142:4027. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Barrett KJ. Anti-DNA antibodies, autoimmunity, and the immunoglobulin repertoire. Int Rev Immunol. 1989;5:43. doi: 10.3109/08830188909086989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Guillaume T, Rubinstein DB, Young F, Tucker L, Lotenberg T, Schwartz RS, Barrett KJ. Individual VH genes detected with oligonucleotide probes from the complementary-determining regions. J Immunol. 1990;145:1934. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pascual V, Randen I, Thompson K, Sioud M, Forre O, Natvig J, Capra JD. The complete nucleotide sequences of the heavy chain variable regions of six mono-specific rheumatoid factors derived from Epstein-Barr virus-transformed B cells isolated from the synovial tissue of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Clin Invest. 1990;86:1320. doi: 10.1172/JCI114841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pascual V, Capra JD. Human immunoglobulin heavy-chain variable region genes: organization, polymorphism, and expression. Adv Immunol. 1991;49:1. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60774-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Manheimer-Lory A, Katz JB, Pillinger M, Ghossein C, Smith A, Diamond B. Molecular characteristics of antibodies bearing an anti-DNA-associated idiotype. J Exp Med. 1991;174:1639. doi: 10.1084/jem.174.6.1639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Schroeder HW, Jr, Hillson JL, Perlmutter RM. Structure and evolution of mammalian VH families. Int Immunol. 1989;2:41. doi: 10.1093/intimm/2.1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chen PP. Structural analyses of human developmentally regulated Vh3 genes. Scand J Immunol. 1990;31:257. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.1990.tb02767.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Allen D, Simon T, Sablitzky F, Rajewsky K, Cumano A. Antibody engineering for the analysis of affinity maturation of an anti-hapten response. EMBO J. 1988;7:1995. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb03038.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kocks C, Rajewsky K. Stable expression and somatic hypermutation of antibody V regions in B-cell developmental pathways. Ann Rev Immunol. 1989;7:537. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.07.040189.002541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Shlomchik MJ, Marshank-Rothstein A, Wolfowicz CB, Rothstein TL, Weigert MG. The role of clonal selection and somatic mutation in autoimmunity. Nature. 1987;328:805. doi: 10.1038/328805a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Jukes TH, King JL. Evolutionary nucleotide replacements in DNA. Nature. 1979;281:605. doi: 10.1038/281605a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Foote J, Milstein C. Kinetic maturation of an immune response. Nature. 1991;352:530. doi: 10.1038/352530a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sanz I. Multiple mechanisms participate in the generation of diversity of human H chain CDR3 regions. J Immunol. 1991;147:1720. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sanz I, Casali P, Thomas JW, Notkins AL, Capra JD. Nucleotide sequences of eight human natural autoantibodies VH regions reveal apparent restricted use of VH families. J Immunol. 1989;142:4054. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Riboldi P, Kasaian MT, Mantovani L, Ikematsu H, Casali P. Natural antibodies. In: Bona CA, Siminovitch K, Zanetti M, Theofilopoulos AN, editors. The Molecular Pathology of Autoimmune Diseases. Gordon & Breach Science Publishers; Philadelphia: 1993. In press. [Google Scholar]