Abstract

Background

The relationship between reward sensitivity and pediatric anxiety is poorly understood. Evidence suggests that alterations in reward processing are more characteristic of depressive than anxiety disorders. However, some studies have reported that anxiety disorders are also associated with perturbations in reward processing. Heterogeneity in the forms of anxiety studied may account for the differences between studies. We used the feedback-negativity, an event-related potential sensitive to monetary gains versus losses (ΔFN), to examine whether different forms of youth anxiety symptoms were uniquely associated with reward sensitivity as indexed by neural reactivity to the receipt of positive and negative monetary outcomes.

Method

Participants were 390, eight- to ten-year-old children (175 females) from a large community sample. The ΔFN was measured during a monetary reward task. Self-reports of child anxiety and depression symptoms and temperamental positive emotionality (PE) were obtained.

Results

Multiple regression analysis revealed that social anxiety and generalized anxiety symptoms were unique predictors of reward sensitivity after accounting for concurrent depressive symptoms and PE. While social anxiety was associated with a greater ΔFN, generalized anxiety was associated with a reduced ΔFN.

Conclusions

Different symptom dimensions of child anxiety are differentially related to alterations in reward sensitivity. This may, in part, explain inconsistent findings in the literature regarding reward processing in anxiety.

Keywords: Anxiety, reward processing, children, event-related potentials

Introduction

Recent research on anxiety disorders has focused on the role of threat-processing in the development and maintenance of anxiety disorders (Bar-Haim, Lamy, Pergamin, Bakermans-Kranenburg, & van IJzendoorn, 2007). Less is known about reward processing in anxiety disorders, particularly in youth. A number of prominent theoretical models posit that alterations in reward processing are relatively specific to depressive as compared to anxiety disorders (e.g. Clark & Watson, 1991; Davidson, 1992). Corresponding evidence from both behavioral and neuroimaging studies suggest that children and adults who have, or are at risk for, depression show a blunted sensitivity to reward, but this abnormality is not apparent in their anxious counterparts (Forbes, Shaw, & Dahl, 2007; Shankman et al., 2013). For example, in one recent study, reduced left frontal asymmetry – a psychophysiological indicator believed to index anticipation of reward – during a slot a machine paradigm was uniquely associated with Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) with or without a lifetime history of Panic Disorder (PD), but not PD without a history of MDD (Shankman et al., 2013).

Conflicting with these findings, however, is a small body of research suggesting that alterations in reward processing may also play a role in anxiety disorders. For example, in a community sample, Forbes et al. (2006) found that during a fMRI reward decision-making task, compared to depressed adolescents, anxious adolescents exhibited both similar and distinct patterns of enhanced and reduced activation in a number of reward-related brain areas during anticipation and receipt of monetary reward. For example, anxious adolescents displayed higher OFC activation when anticipating high magnitude monetary outcomes, whereas depressed adolescents exhibited lower activity. In contrast, both depressed and anxious adolescents displayed reduced ACC and enhanced left amygdala activation in response to high magnitude rewards compared to controls. Moreover, anxious and depressive symptoms independently explained variance in reward-related brain activity in these regions.

Behavioral and neuroimaging studies in both adolescents and adults indicate that social anxiety may be associated with enhanced reward anticipation (Guyer et al., 2012; Hardin et al., 2006). In comparison to healthy controls, adolescents with social anxiety and adolescents with a history of behavioral inhibition (BI) – a temperamental construct associated with heightened risk for social anxiety – exhibited greater striatal activity to increasing magnitudes of potential monetary gains and losses during a Monetary Incentive Delay task (Guyer et al., 2006, 2012). Interestingly, when receipt rather than anticipation of reward was examined, BI individuals showed greater striatal activation only to feedback indicating the omission of reward (Helfinstein et al., 2011). One possibility is that this enhanced sensitivity to anticipatory reward extends to the social domain and underlies the approach-avoidance conflicts (Asendorpf, 1990) characterizing socially anxious and BI individuals. That is, these individuals may have a strong desire to perform well and be positively evaluated, but heightened sensitivity to the nonreceipt of positive feedback may be aversive and intensify motivation to withdraw at the expense of these appetitive inclinations.

In addition to social anxiety, a small body of research suggests that Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) is associated with perturbations in reward processing that are relatively specific to loss. Guyer et al. (2012) found that, in contrast to healthy controls, adolescents with GAD showed reduced striatal activity compared to a baseline neutral condition when anticipating the potential for monetary losses versus gains. Behaviorally, reward abnormalities were also observed in adolescents on an antisaccade task (Jazbec, McClure, Hardin, Pine, & Ernst, 2005) and in adults on a differential reward/punishment learning task (Devido et al., 2009). In both of these studies, the positive effect of incentives on performance evident in healthy controls was not only absent in individuals with GAD, but incentives had an impairing effect on task performance – particularly during loss trials. Thus, a failure to effectively modulate behavior in response to contingencies may be one mechanism through which reward-processing abnormalities lead to pathological worry.

Findings suggesting disparate patterns of reward processing between individuals with social and generalized anxiety, in comparison to healthy controls, raise the possibility that anxiety may be heterogeneous with respect to the role of reward. That is, reward-processing abnormalities may relate to different dimensions of anxiety in distinct ways. If so, examining reward in the context of anxiety as a unitary construct, may obscure findings and explain the inconsistences in the literature. Few studies have accounted for heterogeneity in anxiety disorders by examining how reward processing relates to specific forms of adult and adolescent anxiety. Moreover, to our knowledge, no studies have examined this in preadolescent youth. This is particularly important, given that anxiety disorders commonly begin early in life and are highly predictive of later anxiety and mood disorders, as well as other forms of psychopathology (Copeland, Angold, Shanahan, & Costello, 2014). Identifying abnormal reward processes in youth may be crucial to elucidating the mechanisms underlying the varied developmental pathways and outcomes characterizing pediatric anxiety disorders.

Event-related potentials (ERPs) from electroencephalography (EEG) are particularly suited to reliably and cost-effectively assess brain processes related to reward sensitivity across development (Nelson & McCleery, 2008). The feedback-negativity (FN), also referred to as the feedback-related negativity, is an ERP component peaking approximately 300 ms after feedback and observable over frontocentral recording sites, which is elicited by monetary gain compared to loss. The FN is typically conceptualized as negativity elicited by negative feedback like monetary losses, that is absent or diminished in response to positive feedback like monetary gains. Recent evidence reconceptualizes the FN as a positivity in response to rewards, reduced or absent in response to losses (e.g. Foti, Weinberg, Dien, & Hajcak, 2011). The FN is typically analyzed as the difference between mean amplitudes of losses and gains to isolate neural activity elicited by incentive valence (Foti & Hajcak, 2009). More negative ΔFNs are associated with enhanced self-report and behavioral measures of reward sensitivity (Bress & Hajcak, 2013) and increased activation in the ventral striatum and medial prefrontal cortex, key reward-related brain regions (Carlson, Foti, Mujica-Parodi, Harmon-Jones, & Hajcak, 2011). Furthermore, the FN has been used to reliably measure reward sensitivity in children (Bress, Smith, Foti, Klein, & Hajcak, 2012) and adults (Foti & Hajcak, 2009).

Several studies identify associations between the FN and depression (e.g. Bress et al., 2012). Less negative ΔFNs reflecting reduced sensitivity to reward have been linked to symptoms of depression in adolescence and have also prospectively predicted increases in depression symptoms over a 2-year period in adolescent girls (Bress, Foti, Kotov, Klein, & Hajcak, 2013). Fewer studies, however, examine relations between the FN and anxiety. Bress, Meyer, and Hajcak (2013) found in a sample of 10–13-year olds that blunted reward sensitivity (less negative ΔFNs) was unique to symptoms of depression compared to anxiety. However, this study examined only an aggregate of multiple types of anxiety symptoms – it remains unclear how specific symptom dimensions of anxiety are related to reward sensitivity.

We examined whether unique associations exist between neural measures of reward sensitivity, assessed with the FN, and specific forms of anxiety in a large community sample of 8–10-year-old children. We hypothesized that a different pattern of results would emerge when examining the relationship between the FN and broadband versus specific forms of anxiety. Considering prior findings demonstrating that social anxiety is associated with increased striatal activation, whereas generalized anxiety is associated with reduced striatal activation during reward anticipation, we hypothesized that social anxiety symptoms are associated with an enhanced ΔFN, and generalized anxiety, a reduced or blunted ΔFN. Given the possibility that responses to only gains or losses influence associations between anxiety symptoms and the ΔFN, we also examined the FN on gain and loss trials separately. In addition, we explored associations between other common forms of pediatric anxiety and the FN. We used dimensional measures of social anxiety, generalized anxiety, separation anxiety, and panic/somatic symptoms; continuous symptom scores are more sensitive and better-suited to capture the various shades of pediatric anxiety in the community (Markon, Chmielewski, & Miller, 2011).

To rule out the possibility that third variables account for spurious associations between the FN and anxiety, we controlled for potential confounding factors. Given that depression is highly comorbid with anxiety (Angold & Costello, 1993) and characterized by reward-processing abnormalities, we controlled for concurrent depressive symptoms. Similarly, temperamental positive emotionality (PE; closely related to trait extraversion) is related to reward sensitivity (Smillie, 2013) and some forms of anxiety in youth (Gilbert, 2012) and adults (Kotov, Gamez, Schmidt, & Watson, 2010); we also controlled for PE.1 We used self-reports of anxiety, depression, and PE in light of evidence that children are the best informants regarding internalizing/emotional symptoms and traits (Lagattuta, Sayfan, & Bamford, 2012).

Method

Participants

Participants were assessed during middle childhood as part of a larger longitudinal study of the role of temperament in risk for psychopathology. As part of that study, we reported associations between the FN and parental psychopathology (Kujawa, Proudfit, & Klein, 2014), but have not previously examined the FN in relation to child anxiety symptoms. In the original sample (N = 559), families with 3-year-old children were recruited through a commercial mailing list. Children with no significant medical condition or developmental disabilities living with at least one biological parent were eligible. An additional 50 six-year-old children were recruited during the 3-year follow-up to increase the ethnic and racial diversity of the sample. At age 9, 470 children participated in the ERP assessment. Thirty-eight children whose parents reported a significant learning disability were excluded from the final analyses due to concerns about the validity of their self-reports of anxiety; 41 participants were excluded due to poor EEG quality; and data from one participant were lost due to a technical error. This report’s final sample of 390 children (175 females) was 89.3% Caucasian, 7.9% Black or African American, and 2.8% Asian; 11.5% were of Hispanic or Latino origin. In 35.5% of families, one parent, and in 32.0% of families, two parents, had a college degree. The Institutional Review Board approved all study procedures. Families were compensated for their time. After written informed consent from parents and verbal assent from children were obtained, children completed computerized self-report questionnaires. Next, children began the EEG portion of the visit, including a 10-min monetary reward task, in addition to other tasks not discussed in this study.

Measures

Screen for child anxiety-related emotional disorders

The Screen for child anxiety-related emotional disorders (SCARED-SR) (Birmaher, Chiappetta, Bridge, Monga, & Baugher, 1999) is a 41-item self-report questionnaire that assesses severity of anxiety symptoms in youth ages 8–18. Items are rated on a 3-point scale. In addition to yielding a total broadband score (α = .88), the SCARED measures five dimensions: generalized anxiety (α = .71), social anxiety (α = .73), separation anxiety (α = .69), somatic/panic (α = .77), and school phobia (α = .42). Given the poor alpha for school phobia, we excluded the subscale from analyses.

Children’s depression inventory

The Children’s depression inventory (CDI) (Kovacs, 1985) is a self-report measure that gauges depression symptoms in 7–18-year olds. The CDI consists of 27 items (α = .72), each including three response choices ranging in severity and scored on a 0–2 scale.

Affect and Arousal Scale

Child PE was measured via self-report using the nine-item positive affect scale of the Affect and Arousal Scale (AFARS) (Chorpita, Daleiden, Moffitt, Yim, & Umemoto, 2000). Developed for youth aged 7–18, items are rated on a 4-point scale (α = .69). Higher scores reflect greater energy, enthusiasm, and excitement.2

Reward task

The task was administered using Presentation software (Neurobehavioral Systems) similar to a version used in previous studies (Foti & Hajcak, 2009). Participants were instructed to click either the left or right mouse button when presented with images of two doors, to guess which had a monetary prize. They were told they could win $0.50 or lose $0.25 on each trial and win up to $5 total, which would be given to them upon task completion. Given that losses are weighted more heavily than gains (Tversky & Kahneman, 1992), these values were selected to equalize the subjective value of outcomes. At the beginning of each trial, participants were presented with images of two doors, which remained on the screen until the participant responded. Next, a fixation mark (+) appeared for 1000 ms, and feedback was presented for 2000 ms. A win was indicated by a green “↑,” and a loss, by a red “↓.” A fixation mark appeared for 1500 ms, followed by the message “Click for the next round” which remained on the screen until the participant responded and the next trial began. Across the task, 30 win and 30 loss trials were presented in a random order.

EEG data acquisition and processing

Electroencephalography was recorded using a 34-channel Biosemi system based on the 10/20 system (32-channel cap with Iz and FCz added). Electrooculogram and mastoid activity were also recorded. During acquisition, the Common Mode Sense and the Driven Right Leg electrodes formed the ground electrode. The data were digitized at 24-bit resolution with a Least Significant Bit value of 31.25nV and a sampling rate of 1024 Hz, using a low-pass fifth order sinc filter with −3 dB cutoff points at 208 Hz. Off-line analysis was performed using Brain Vision Analyzer (Version 2.0.4; GmbH; Munich, DE; Brain Products). Data were converted to an average mastoid reference, band-pass filtered with cutoffs of 0.1 and 30 Hz, segmented for each trial 200 ms before feedback onset and continuing for 1000 ms after onset. The EEG was corrected for eye blinks (Gratton, Coles, & Donchin, 1983). Artifact rejection was completed using semiautomated procedures and the following criteria: a voltage step greater than 50 μV between sample points, a voltage difference of 300 μV within a trial, and a voltage difference of less than .50 μV within 100 ms intervals. Visual inspection was used to remove residual artifacts due to eye movement, muscle activity, linear drift, stray electrodes, and artifacts related to electronics. After artifact rejection, participants, on average, were left with 29 trials for each condition. Participants with fewer than 20 valid trials in either condition were excluded from analyses. Data were baseline corrected using the average activity in the 200 ms interval prior to feedback.

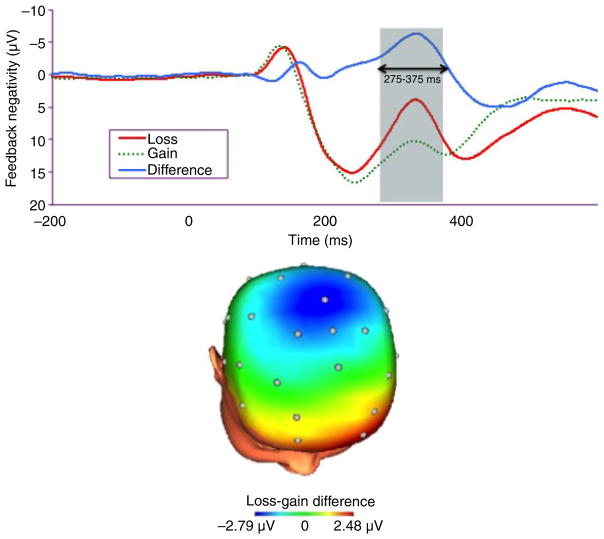

ERPs were separately averaged across win and loss trials. The FN was scored as the mean amplitude 275–375 ms following feedback, when the loss minus gain difference wave was maximal. To reduce noise associated with recording at a single electrode, the FN was scored at a pooling of FCz and Cz, which is consistent with previous research (Bress et al., 2012) and the scalp distribution of the difference wave (see Figure 1). We examined both the difference between the mean amplitude on loss relative to gain trials (ΔFN), and on gain and loss trials separately.

Figure 1.

Event-related potentials (negative up) at FCz/Cz following feedback and the scalp distribution depicting the loss–gain difference 275–375 ms after feedback

Data analysis

To evaluate the relationship between pediatric anxiety and reward sensitivity, multiple regression analysis was performed in which the dependent variable was ΔFN and the independent variables included demographics (child gender, ethnicity/race, and age); child-reported depressive symptoms and PE; and the SCARED-SR Broadband Anxiety score. To determine associations between specific dimensions of anxiety and reward sensitivity, we repeated the multiple regression replacing the Broadband Anxiety score with the Generalized Anxiety, Social Anxiety, Separation Anxiety, and Panic/Somatization subscales. As follow-up analyses, we conducted additional regressions to examine the FN to gains and losses separately. All variables were screened for univariate normality. Kurtosis was high for panic/somatic (3.01), so we performed a square-root transformation, which brought the panic/somatic variable within acceptable parameters (skew = 0.12, kurtosis = 0.27).3 All other study variables were relatively normal with skewness and kurtosis indices less than ±2.

Results

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations of the study variables. As expected, the anxiety subscales were moderately intercorrelated, and depression symptoms exhibited low-moderate correlations with each of the anxiety scales. Consistent with the literature (Gilbert, 2012), low PE was associated with both depression and social anxiety symptoms, such that lower PE was related to a greater number of both depression and social anxiety symptoms. The ΔFN did not correlate with measures of depression, anxiety, or PE. The FN to loss, however, was correlated with both generalized and social anxiety; both associations suggested reduced reactivity to loss with increasing symptoms. The FN to gain was correlated with social anxiety, such that increasing social anxiety was related to a larger positivity to gains.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics and bivariate associations between variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender | – | .00 | .12* | −.17* | −.06 | .00 | −.01 | −.10* | −.11* | −.18** | .13* | −.01 |

| 2. Age | – | .02 | .00 | −.03 | −.01 | −.01 | −.02 | −.05 | .04 | .06 | .09 | |

| 3. Depressive Symptoms | – | −.24** | .39** | .32** | .37** | .24** | .18** | −.02 | .03 | .02 | ||

| 4. PE | – | −.04 | .01 | −.05 | .01 | −.14** | −.08 | .02 | −.05 | |||

| 5. Broadband Anxiety | – | .82** | .80** | .77** | .71** | .01 | .06 | .08 | ||||

| 6. Panic/Somatic | – | .60** | .55** | .43** | .01 | .02 | .03 | |||||

| 7. Generalized Anxiety | – | .49** | .44** | .07 | .06 | .12* | ||||||

| 8. Separation Anxiety | – | .45** | −.01 | .05 | .04 | |||||||

| 9. Social Anxiety | – | −.04 | .12* | .10* | ||||||||

| 10. ΔFN | – | −.44** | .35** | |||||||||

| 11. FN-Gain | – | .68** | ||||||||||

| 12. FN-Loss | – | |||||||||||

| M | 110.00 | 4.60 | 24.86 | 19.32 | 4.18 | 3.68 | 5.16 | 5.05 | −5.21 | 14.10 | 8.89 | |

| SD | 4.72 | 3.93 | 3.92 | 10.88 | 3.83 | 2.99 | 3.11 | 3.13 | 7.81 | 10.00 | 9.67 | |

| Range | 100.00–131.00 | 0.00–22.00 | 0.05–30.00 | 1.00–61.00 | 0.00–21.00 | 0.00–15.00 | 0.00–14.00 | 0.00–14.00 | −32.11–19.82 | −9.59–46.21 | −21.75–40.53 |

PE, positive emotionality.

p ≤ .05;

p < .01.

The multiple regression analysis computed with demographics, depressive symptoms, PE, and broadband anxiety symptoms revealed that both gender and PE were significantly associated with the ΔFN such that higher PE and male gender were associated with a larger (more negative) ΔFN. Broadband anxiety symptoms were not significantly associated with the ΔFN (Table 2).

Table 2.

Multiple regression analyses regressing broadband and dimensional symptoms of anxiety on the ΔFN

| ΔFN

|

||

|---|---|---|

| b (SE) | β | |

| Model 1–Broadband anxiety | ||

| Gender | −3.01 (0.80) | −.19*** |

| Ethnicity/Race | 0.59 (0.99) | .03 |

| Age (Months) | 0.07 (0.08) | .04 |

| Depressive symptoms | −0.07 (0.11) | −.03 |

| PE | −0.24 (0.10) | −.12* |

| Broadband anxiety symptoms | 0.00 (0.04) | .00 |

| F(6,383) = 3.08 **, R2 = 0.05 | ||

| Model 2–Dimensions of anxiety | ||

| Gender | −3.27 (0.80) | −.21*** |

| Ethnicity/Race | 0.26 (0.99) | .01 |

| Age (Months) | 0.06 (0.08) | .04 |

| Depressive symptoms | −0.12 (0.11) | −.06 |

| PE | −0.27 (0.11) | −.14** |

| Social anxiety | −0.31 (0.15) | −.13* |

| Generalized anxiety | 0.40 (0.18) | .15* |

| Separation anxiety | −0.11 (0.16) | −.04 |

| Panic/Somatic anxiety | −0.10 (0.54) | −.01 |

| F(9,380) = 3.06**, R2 = .07 | ||

p ≤ .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

Next, we reran the model substituting the four SCARED anxiety subscales for the total anxiety score. This allowed us to examine the unique effects of each form of anxiety, controlling for the correlations between the subscales. Gender, PE, social anxiety, and generalized anxiety were all significant predictors of the ΔFN (Table 2). While both increasing PE and social anxiety were associated with greater differentiation, increasing generalized anxiety was associated with reduced differentiation between losses and gains.4 Depressive symptoms did not predict ΔFN.

When we examined the FN to gains and losses separately, broadband symptoms of anxiety were not related to the FN to either gains or losses (Table 3). Both increasing social anxiety and male gender predicted a greater positivity to gains. Increasing generalized anxiety and younger age were significantly associated with a less negative FN to loss. Taken together, these results suggest that the more negative ΔFN score associated with heightened social anxiety may be more strongly associated with an enhanced sensitivity to gain, while the less negative ΔFN score associated with heightened generalized anxiety may be more strongly associated with a blunted sensitivity to loss.

Table 3.

Multiple regression analyses regressing broadband and dimensional symptoms of anxiety on the FN-Gain and FN-Loss

| FN-Gain

|

FN-Loss

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| b (SE) | β | b (SE) | β | |

| Model 1–Broadband anxiety | ||||

| Gender | 2.79 (1.04) | .14** | −0.22 (1.01) | −.01 |

| Ethnicity/Race | −0.06 (1.28) | −.01 | 0.53 (1.24) | .02 |

| Age (Months) | 0.13 (0.11) | .06 | 0.20 (0.10) | .10 |

| Depressive symptoms | −0.02 (0.15) | −.01 | −0.08 (0.14) | −.03 |

| PE | 0.12 (0.14) | .04 | −0.13 (0.13) | −.05 |

| Broadband anxiety | 0.07 (0.05) | .08 | 0.08 (0.05) | .09 |

| F(6,383) = 1.73, R2 = 0.03 | F(6,383) = 1.17, R2 = 0.03 | |||

| Model 2–Dimensions of anxiety | ||||

| Gender | 3.18 (1.04) | .16** | −0.09 (1.01) | −.01 |

| Ethnicity/Race | 0.24 (1.28) | .01 | 0.50 (1.24) | .02 |

| Age (Months) | 0.14 (0.11) | .07 | 0.20 (0.10) | .10* |

| Depressive symptoms | 0.02 (0.14) | .01 | −0.10 (0.14) | −.04 |

| PE | 0.18 (0.14) | .07 | −0.10 (0.13) | −.04 |

| Social anxiety | 0.53 (0.19) | .17** | 0.22 (0.19) | .07 |

| Generalized anxiety | 0.07 (0.23) | .02 | 0.47 (0.22) | .15* |

| Separation anxiety | 0.07 (0.21) | .02 | −0.04 (0.20) | −.01 |

| Panic/Somatic | −0.77 (0.70) | 3.08 | −0.67 (0.67) | −.07 |

| F(9,380) = 2.05*, R2 = .05 | F(9,380) = 1.44, R2 = .03 | |||

p ≤ .05;

p < .01.

Discussion

We examined whether specific dimensions of pediatric anxiety are differentially related to alterations in electrocortical responses to monetary gains and losses. We found no association between broadband anxiety and reward sensitivity. However, a different pattern emerged when we simultaneously examined the relationship between reward processing and specific symptom dimensions. After accounting for demographics, concurrent symptoms of depression, and temperamental PE, symptoms of social and generalized anxiety were uniquely associated with the ΔFN; social anxiety was associated with an enhanced ΔFN, whereas generalized anxiety was associated with a blunted ΔFN. Separation anxiety and panic/somatic symptoms were not related to ΔFN.

Anxiety disorders have previously been linked to abnormalities in reward processing on neuroimaging (Forbes et al., 2006) and behavioral (Devido et al., 2009; Jazbec et al., 2005) measures. However, to our knowledge, this is the first study to examine multiple dimensions of anxiety and take into account their covariation in evaluating the neural correlates of anxiety-related perturbations in reward processing in youth. Our findings are also the first to suggest that, like depression, specific forms of pediatric anxiety are associated with a disrupted ΔFN response.

In the current study, social anxiety was associated with heightened reward sensitivity (i.e. a more negative ΔFN). As symptoms of social anxiety increased, so did neural differentiation between monetary gains compared to losses. Symptoms of generalized anxiety showed the opposite pattern: higher generalized anxiety was characterized by reduced differentiation between gains and losses. Taken together, these findings suggest that symptoms of social and generalized anxiety are associated with dissociable neurocognitive profiles following the receipt of feedback indicating reward versus loss. A fear of evaluation in social and performance-based situations may be linked to hypersensitivity to external environmental contingencies, whereas excessive worry may be characterized by hyposensitivity to the environment.

Additional distinctions between social and generalized anxiety were found when loss and gain trials were examined separately. Symptoms of social anxiety elicited an enhanced FN following the receipt of positive feedback, suggesting that the reward hypersensitivity in social anxiety may be specifically driven by reactivity to gains. Our finding, however, is inconsistent with evidence from Helfinstein et al. (2011) who found that, in an adolescent sample of 14- to 18-year olds, a history of BI is associated with a hypersensitivity to the absence, as opposed to the receipt, of reward stimuli. It is possible that discrepant findings are a result of developmental changes in the reward system. In adolescence, inhibited, socially anxious youth are likely to have an increasing number of experiences in which they fail to obtain social rewards which may alter the reward system in a fashion that biases it away from appetitive outcomes (Silk, Davis, McMakin, Dahl, & Forbes, 2012). Prospective studies are needed to examine this possibility. Although BI and symptoms of social anxiety show some degree of overlap, they are not identical (Pérez-Edgar & Fox, 2005), which may also account for the discrepant findings.

Consistent with previous behavioral (Devido et al., 2009; Jazbec et al., 2005) and neuroimaging (Guyer et al., 2012) studies, we found that disruptions in reward processing associated with generalized anxiety may be driven by abnormalities in processing negative feedback, specifically a blunted FN in response to monetary loss. This is also consistent with evidence suggesting that deactivating the mesolimbic dopamine system causes impairment in contingency awareness to aversive events, resulting in a generalized anxiety-like phenotype in mice (Zweifel et al., 2011). Inability to effectively process and learn from negative outcomes may lead to generalized fear in nonthreatening situations, and ultimately, to chronic worry.

Importantly, there were no bivariate associations between ΔFN and any form of pediatric anxiety, highlighting the need to examine symptom dimensions simultaneously. Zero-order correlations and multiple regressions revealed that social anxiety symptoms are associated with an enhanced positivity to gain, and generalized anxiety symptoms are associated with a reduced negativity to loss. This suggests that symptoms of social and generalized anxiety may have opposing influences on reward sensitivity that obscure bivariate associations with ΔFN. Thus, symptoms of each should be accounted for in future studies examining reward-anxiety associations. In addition, despite the moderate correlation between symptoms of generalized and social anxiety, our findings suggest that each may be etiologically distinct. Clinically, determining whether anxious youth are hyper-versus hyporeactive to reward may facilitate more tailored treatment approaches.

Although PE and social anxiety were inversely related, intriguingly, both were significantly associated with increased reward sensitivity. The negative association between social anxiety and PE may be largely due to the interpersonal, rather than reward, facets of PE/extraversion (Watson & Naragon-Gainey, 2010). Given that social anxiety and PE both accounted for unique variance in the ΔFN, it is likely that each taps different aspects of reward sensitivity. Indeed, they may even have opposing influences that obscure associations with ΔFN when not considered simultaneously.

Although previous research has found that a reduced ΔFN is associated with concurrent depressive symptoms in older children and adolescents (Bress et al., 2012), we did not find an effect of depressive symptoms on the ΔFN. This is likely a result of the limited range of symptoms in our sample, as the prevalence of depression is low during middle childhood. The relationship between the ΔFN and depressive symptoms may increase over the course of development. Bress, Foti, et al. (2013) found that a reduced ΔFN in early adolescence predicted the onset of a depressive episode 2 year later. This suggests that, during middle childhood, a blunted ΔFN may be a marker of risk for, rather than a correlate of, depression. Given the high comorbidity and genetic overlap between GAD and MDD in adolescence and adulthood (Waszczuk, Zavos, Gregory, & Eley, 2014), a blunted ΔFN linked to generalized anxiety during childhood may be an earlier manifestation of, or precursor to, some forms of depression (Copeland et al., 2014). Additional prospective research is necessary to evaluate this possibility.

In addition, we found younger age to be associated with enhanced FN on loss trials, consistent with evidence suggesting the relationship between age and FN magnitude to loss decreases over development. Eppinger, Kray, Mecklinger, and John (2007) found that in comparison to young adults, 10–12-year olds showed an enhanced FN in response to negative feedback. Thus, younger children may be more reliant on external feedback to appropriately modulate behavior in response to negative outcomes. Males, compared to females, demonstrated an enhanced ΔFN, characterized by greater reactivity to monetary gains. These results are consistent with other findings discussed in detail elsewhere (Kujawa et al., 2014).

This study has several limitations. First, our monetary reward task included only one class of reward and we did not collect ratings of the degree to which children found the monetary incentives to be rewarding. It remains to be seen whether our findings generalize to nonmonetary stimuli such as social feedback or are indicative of neural processes associated with the subjective experience of reward receipt. Second, the cross-sectional design does not allow us to determine whether reward-processing abnormalities as indexed by the FN are a vulnerability, correlate, or result of pediatric anxiety. Future longitudinal studies should examine the relationship between the FN and anxiety over the course of development. Third, it is possible that the difference in magnitude of gains ($0.50) and losses ($0.25) influenced results. However, the FN has been shown to be relatively insensitive to magnitude and instead reflects a binary evaluation of outcomes as good or bad (Hajcak, Moser, Holroyd, & Simons, 2006). Fourth, the percentage of explained variance of the regression models is relatively small. However, this may be attributed to the substantial difference in methods, as small associations are commonly found between neurophysiological and self-report measures (Patrick et al., 2013). Finally, as we used a community-based sample, it is unclear whether these findings extend to clinical populations.

Conclusion

The present study is the first to use a neural measure of reward sensitivity to examine specific dimensions of anxiety in preadolescent youth. Results suggest that perturbations in reward processing are differentially associated with symptoms of social and generalized anxiety. Social anxiety may be characterized by reward hypersensitivity that is relatively specific to gain, whereas generalized anxiety may be characterized by reward hyposensitivity that is relatively specific to loss. These findings underscore the importance of considering the heterogeneity of the symptom presentation of pediatric anxiety when examining reward–anxiety associations. They also point to the utility of using the FN to identify reward-processing abnormalities in youth emotional disorders.

Key points.

Blunted reward sensitivity may be characteristic of depression. Little is known about the role of reward-processing abnormalities in anxiety, particularly in youth.

We used the FN, an ERP associated with reward sensitivity to simultaneously examine dimensions of specific, compared to broadband, symptoms of pediatric anxiety.

Both symptoms of social and generalized anxiety were uniquely associated with a disrupted FN response to monetary reward, but in opposite directions.

While symptoms of social anxiety were associated with greater neural differentiation between monetary gains and losses, symptoms of general anxiety were associated with reduced differentiation.

The FN may be a useful measure of reward sensitivity to identify neural disruptions associated with youth emotional disorders.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIMH Grants: RO1MH069942 to DNK; RO3MH094518 to GHP; and F31MH09530701 to AK.

Footnotes

The reward system changes significantly during the transition from childhood to adolescence, which may result in developmental differences in the link between anxiety and reward functioning (Ernst, Pine & Hardin, 2009). Although most children in the present study were prepubertal, we conducted additional analyses controlling for pubertal status using the Pubertal Developmental Scale (Petersen, Crockett, Richards, & Boxer, 1988). We also controlled for externalizing symptoms measured via the Child Behavior Checklist (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001) given that previous empirical studies have identified associations between the ΔFN and externalizing disorders (Matthys, Vanderschuren & Schutter, 2013). Results were similar to those reported below.

Mean scores on the CDI, SCARED, and AFARS-PE scale were consistent with other community studies.

Analyses using the nontransformed panic/somatic score yielded virtually identical results.

To test whether gender moderates the generalized anxiety–ΔFN associations and social anxiety–ΔFN associations, we repeated the analyses adding generalized anxiety X sex and social anxiety X sex interaction terms in Step 2. Neither interaction was significant.

To test whether gender moderates the social anxiety– FN association to gain and age moderates the generalized anxiety–FN association to loss, we repeated the analyses adding generalized anxiety X age and social anxiety X gender interactions in Step 2, respectively. Neither interaction was significant.

The authors have declared that they have no competing or potential conflicts of interest.

Conflict of interest statement: No conflicts declared.

References

- Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Manual for the ASESBA school-age forms and profiles. Burlington: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, and Families; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Angold A, Costello EJ. Depressive comorbidity in children and adolescents: empirical, theoretical, and methodological issues. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1993;150:1779–1791. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.12.1779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asendorpf J. Beyond social withdrawal: shyness, unsociability, and peer avoidance. Human Development. 1990;33:250–259. [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Haim Y, Lamy D, Pergamin L, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, van IJzendoorn MH. Threat-related attentional bias in anxious and nonanxious individuals: a meta-analytic study. Psychological Bulletin. 2007;133:1–24. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birmaher B, Chiappetta L, Bridge J, Monga S, Baugher M. Psychometric properties of the Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders (SCARED): A replication study. Journal of American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1999;38:1230–1236. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199910000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bress JN, Foti D, Kotov R, Klein DN, Hajcak G. Blunted neural response to rewards prospectively predicts depression in adolescent girls. Psychophysiology. 2013;50:74–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2012.01485.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bress JN, Hajcak G. Self-report and behavioral measures of reward sensitivity predict the feedback negativity. Psychophysiology. 2013;50:610–616. doi: 10.1111/psyp.12053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bress JN, Meyer A, Hajcak G. Differentiating anxiety and depression in children and adolescents: evidence from event-related brain potentials. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2013;53:37–41. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2013.814544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bress JN, Smith E, Foti D, Klein DN, Hajcak G. Biological Psychology. Vol. 89. Elsevier B.V; 2012. Neural response to reward and depressive symptoms in late childhood to early adolescence; pp. 156–162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson JM, Foti D, Mujica-Parodi LR, Harmon-Jones E, Hajcak G. Ventral striatal and medial prefrontal BOLD activation is correlated with reward-related electrocortical activity: A combined ERP and fMRI study. NeuroImage. 2011;57:1608–1616. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.05.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chorpita BF, Daleiden EL, Moffitt C, Yim L, Umemoto LA. Assessment of tripartite factors of emotion in children and adolescents I: Structural validity and normative data of an affect and arousal scale. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2000;22:141–160. [Google Scholar]

- Clark LA, Watson D. Tripartite model of anxiety and depression: Psychometric evidence and taxonomic implications. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1991;100:316–336. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.100.3.316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copeland WE, Angold A, Shanahan L, Costello EJ. Longitudinal patterns of anxiety from childhood to adulthood: The great smoky mountains study. Journal of the American Academy of Childand Adolescent Psychiatry. 2014;53:21–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2013.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson RJ. Anterior cerebral asymmetry and the nature of emotion. Brain and Cognition. 1992;20:125–151. doi: 10.1016/0278-2626(92)90065-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devido J, Jones M, Geraci M, Hollon N, Blair RJR, Pine DS, Blair K. Stimulus-reinforcement based decision-making and anxiety: Impairment in generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), but not in generalized social phobia (GSP) Psychological Medicine. 2009;39:1153–1161. doi: 10.1017/S003329170800487X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eppinger B, Kray J, Mecklinger A, John O. Age differences in task switching and response monitoring: Evidence from ERPs. Biological Psychology. 2007;75:52–67. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2006.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst M, Pine DS, Hardin M. Triadic model of the neurobiology of motivated behavior in adolescence. Psychological Medicine. 2006;36:299–312. doi: 10.1017/S0033291705005891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forbes EE, May JC, Siegle GJ, Ladouceur CD, Ryan N, Carter CS, Dahl RE. Reward-related decision making in pediatric major depressive disorder: an fmri study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2006;47:1031–1040. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01673.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forbes EE, Shaw DS, Dahl RE. Alterations in reward-related decision making in boys with recent and future depression. Biological Psychiatry. 2007;61:633–639. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foti D, Hajcak G. Depression and reduced sensitivity to non-rewards versus rewards: Evidence from event-related potentials. Biological Psychology. 2009;81:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2008.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foti D, Weinberg A, Dien J, Hajcak G. Even-trelated potential activity in the basal ganglia differentiates rewards from nonrewards. Human Brain Mapping. 2011;32:2207–2216. doi: 10.1002/hbm.21182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert K. The neglected role of positive emotion in adolescent psychopathology. Clinical Psychology Review. 2012;32:467–481. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2012.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratton G, Coles MG, Donchin E. A new method for off-line removal of ocular artifact. Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology. 1983;55:468–484. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(83)90135-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyer A, Choate V, Detloff A, Benson B, Nelson E, Pérez-Edgar K, Ernst M. Striatal functional alteration during incentive anticipation in pediatric anxiety disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2012;169:205–212. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.11010006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyer AE, Nelson EE, Perez-Edgar K, Hardin MG, Roberson-Nay R, Monk CS, Ernst M. Striatal functional alteration in adolescents characterized by early childhood behavioral inhibition. Journal of Neuroscience. 2006;26:6399–6405. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0666-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajcak G, Moser JS, Holroyd CB, Simons RF. The feedback-related negativity reflects the binary evaluation of good versus bad outcomes. Biological Psychology. 2006;71:148–154. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2005.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardin MG, Perez-Edgar K, Guyer AE, Pine DS, Fox NA, Ernst M. Reward and punishment sensitivity in shy and non-shy adults: Relations between social and motivated behavior. Personality and Individual Differences. 2006;40:699–711. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2005.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helfinstein SM, Benson B, Perez-Edgar K, Bar-Haim Y, Detloff A, Pine DS, Ernst M. Striatal responses to negative monetary outcomes differ between temperamentally inhibited and non-inhibited adolescents. Neuropsychologia. 2011;49:479–485. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2010.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jazbec S, McClure E, Hardin M, Pine DS, Ernst M. Cognitive control under contingencies in anxious and depressed adolescents: An antisaccade task. Biological Psychiatry. 2005;58:632–639. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotov R, Gamez W, Schmidt F, Watson D. Linking “big” personality traits to anxiety, depressive, and substance use disorders: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 2010;136:768–821. doi: 10.1037/a0020327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M. The children’s depression inventory. Psychopharmacology Bulletin. 1985;21:995–998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kujawa AJ, Proudfit GH, Klein DN. Neural reactivity to reward in offspring of mothers and fathers with histories of depressive and anxiety disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2014;123:287–297. doi: 10.1037/a0036285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagattuta KH, Sayfan L, Bamford C. Do you know how I feel? Parents underestimate worry and overestimate optimism compared to child self-report. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 2012;113:211–232. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2012.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markon KE, Chmielewski M, Miller CJ. The reliability and validity of discrete and continuous measures of psychopathology: A quantitative review. Psychological Bulletin. 2011;137:856–879. doi: 10.1037/a0023678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthys W, Vanderschuren LJ, Schutter DG. The neurobiology of oppositional defiant disorder and conduct disorder: Altered functioning in three mental domains. Development and Psychopathology. 2013;25:193–207. doi: 10.1017/S0954579412000272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson CA, McCleery JP. Use of event-related potentials in the study of typical and atypical development. Journal of American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2008;47:1252–1261. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e318185a6d8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick CJ, Venables NC, Yancey JR, Hicks BM, Nelson LD, Kramer MD. A construct-network approach to bridging diagnostic and physiological domains: Application to assessment of externalizing psychopathology. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2013;122:902. doi: 10.1037/a0032807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Edgar K, Fox NA. Temperament and anxiety disorders. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2005;14:681–706. viii. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2005.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen A, Crockett L, Richards M, Boxer A. A self-report measure of pubertal status: Reliability, validity, and initial norms. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1988;17:117rnal. doi: 10.1007/BF01537962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shankman SA, Nelson BD, Sarapas C, Robison-Andrew EJ, Campbell ML, Altman SE, Gorka SM. A psychophysiological investigation of threat and reward sensitivity in individuals with panic disorder and/or major depressive disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2013;122:322–338. doi: 10.1037/a0030747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silk JS, Davis S, McMakin DL, Dahl RE, Forbes EE. Why do anxious children become depressed teenagers? The role of social evaluative threat and reward processing. Psychological Medicine. 2012;42:2095–2107. doi: 10.1017/S0033291712000207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smillie LD. Extraversion and reward processing. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2013;22:167–172. doi: 10.1177/0963721412474460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tversky A, Kahneman D. Advances in prospect-theory —Cumulative representation of uncertainty. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty. 1992;5:297–323. [Google Scholar]

- Waszczuk M, Zavos H, Gregory A, Eley T. The phenotypic and genetic structure of depression and anxiety disorder symptoms in childhood, adolescencs and young adulthood. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71:905–916. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Naragon-Gainey K. On the specificity of positive emotional dysfunction in psychopathology: evidence from the mood and anxiety disorders and schizophrenia/schizotypy. Clinical Psychology Review. 2010;30:839–848. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zweifel LS, Fadok JP, Argilli E, Garelick MG, Jones G, Dickerson TMK, Palmiter RD. Activation of dopamine neurons is critical for aversive conditioning and prevention of generalized anxiety. Nature Neuroscience. 2011;14:620–626. doi: 10.1038/nn.2808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]