Abstract

The regulation of ATP-sensitive potassium (KATP) channel activity is complex and a multitude of factors determine their open probability. Physiologically and pathophysiologically, the most important of these are intracellular nucleotides, with a long-recognized role for glycolytically derived ATP in regulating channel activity. To identify novel regulatory subunits of the KATP channel complex, we performed a two-hybrid protein-protein interaction screen, using as bait the mouse Kir6.2 C terminus. Screening a rat heart cDNA library, we identified two potential interacting proteins to be the glycolytic enzymes, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) and triose-phosphate isomerase. The veracity of interaction was verified by co-immunoprecipitation techniques in transfected mammalian cells. We additionally demonstrated that pyruvate kinase also interacts with Kir6.2 subunits. The physiological relevance of these interactions is illustrated by the demonstration that native Kir6.2 protein similarly interact with GAPDH and pyruvate kinase in rat heart membrane fractions and that Kir6.2 protein co-localize with these glycolytic enzymes in rat ventricular myocytes. The functional relevance of our findings is demonstrated by the ability of GAPDH or pyruvate kinase substrates to directly block the KATP channel under patch clamp recording conditions. Taken together, our data provide direct evidence for the concept that key enzymes involved in glycolytic ATP production are part of a multi-subunit KATP channel protein complex. Our data are consistent with the concept that the activity of these enzymes (possibly by ATP formation in the immediate intracellular microenvironment of this macromolecular KATP channel complex) causes channel closure.

KATP channels act as metabolic sensors of a large diversity of cell types by directly coupling their energy metabolism to cellular excitability. This function serves as a crucial regulatory mechanism in the responses of various cell types to their metabolic demand. For example, KATP channels mediate insulin release from pancreatic β cells, control the firing rate of glucose-responsive neurons in the ventromedial hypothalamus, and protect neurons during hypoxia. KATP channels also have unique roles in the cardiovascular system. In the coronary vasculature, they participate in the maintenance of the coronary vascular tone, whereas in cardiac myocytes, KATP channel modulation causes alterations in action potential duration and induction of arrhythmias during cardiac ischemia (1).

The minimum requirement for the formation of a heterologously expressed KATP channel appears to be the presence of two types of subunits, namely a pore-forming subunit (Kir6.x) belonging to the family of inward rectifying K+ channel subunits and a sulfonylurea receptor regulatory subunit, which is a member of the family of ABC-cassette proteins (2). However, ion channels are increasingly realized to be multisubunit macromolecular complexes (3–5). Recent evidence suggest that the KATP channel protein complex may include other metabolically active protein subunits, including adenylate kinase, creatine kinase, and lactate dehydrogenase (6–8). The aim of this study was to further refine the molecular nature of the KATP channel macromolecular protein complex to gain better understanding of the composition and regulation of the KATP channel. In these studies, we identified three glycolytic enzymes, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH),2 triose-phosphate isomerase (TPI), and pyruvate kinase (PK), as functionally relevant accessory subunits of the KATP channel protein complex. We provide evidence that the activity of these enzymes regulate channel activity, presumably by altering the ATP levels in the microenvironment of the KATP channel protein complex.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Generation of Constructs Used for the Two-hybrid Screening

A DNA fragment encoding the truncated COOH terminus of Kir6.2 (Kir6.2CΔ36; amino acids 169–354 of mouse Kir6.2; NP_034732) was generated by PCR using as template the mouse Kir6.2 cDNA (kindly provided by Dr. Susumu Seino, Graduate School of Medicine, Chiba University, Chiba, Japan). The PCR primers were 5′-GGTTCGAATTCAATGAAAACGGCCCAGGCCCATCGG-3′ (sense) and 5′-GAGGGTCAGGGCCTCGAGTCAACTGCGGTCCTCATC-3′ (antisense). The primers contained restriction sites (EcoRI at the 5′ and XhoI at the 3′ end) for in-frame cloning with λC1 into the pBT bait vector (Stratagene) and a stop codon was engineered at the 3′ position. The sub-cloned DNA fragment was verified by sequencing.

Bacterial Two-hybrid Assay

A bacterial two-hybrid assay (Bacteriomatch, Stratagene) was used to identify proteins that interact with Kir6.2CΔ36 (9). Identification of positive clones, recovery of library plasmids, and identification of prey sequences were performed according to the manufacturer’s guidelines. In brief, the pBT-Kir6.2CΔ36 bait plasmid was co-transformed with a rat cDNA library cloned in the target vector, pTRG (Stratagene) into a reporter strain Escherichia coli (Stratagene) that harbors the genetic elements needed to initiate and indicate interaction between partner proteins (λ-operator, ampicillin, and β-galactosidase resistance genes). Protein-protein interaction was detected by growth of carbenicillin-resistant colonies. Positives were further verified using the second marker, β-galactosidase. The nucleotide sequence of positives was determined by sequencing, and the identity of the encoded putative interacting protein was determined by data base searches (Blastx).

Cell Culture, Molecular Biology, and Transfection

COS7L cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum and antibiotics. Cells were transfected at 60–70% confluency using FuGENE 6 (Roche) with the following cDNAs: mouse Kir6.2-HA (10), mouse SUR2A (from Dr. Susumo Seino Graduate School of Medicine, Chiba University, Japan), and/or TPI-GFP. Full-length rat TPI, amino acids 1–249 of NM_022922, was cloned in-frame into pEGFPN1 to generate TPI-GFP.

Co-immunoprecipitation

Co-immunoprecipitation assays were used to analyze the putative protein-protein interactions (11) in both transfected COS7L cells and with native proteins in membrane fractions obtained from rat heart (12). Forty eight h post-transfection, COS7L cells were washed in PBS and lysed in ice-cold buffer (containing in mM), 25 Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 NaCl, 5 EDTA containing 1% (v/v) Triton X-100 and protease inhibitor mixture (1 mM; Sigma), and phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride (1:100). Cardiac membrane fractions were solubilized with 1% Triton X-100 for 2 h at 4 °C prior to incubation with Kir6.2 antibody (W62 antibody). Protein samples (~600–1000 μg) were precleared with 30 μl of protein G-Sepharose beads (Amersham Biosciences) for 2 h at 4 °C. After removing the beads by centrifugation at 20,000 ×g for 30 s, the samples were incubated overnight at 4 °C with appropriate antibodies, ~10 μg of anti-Kir6.2 (W62), NAF-1 (anti-Kir6.1) (13), anti-GAPDH (Chemicon), monoclonal anti-GFP (Clone IL-8, Clontech), or anti-PK (Biogenesis). The W62 antibody has been well characterized and used both in Western blotting and immunoprecipitation as described previously (13). The antibody-protein complexes were captured by incubation with protein G-Sepharose beads for 2–3 h at 4 °C. The immunoprecipitates were pelleted by centrifugation at 20,000 × g for 30 s and washed three times with ice-cold wash buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 0.1% Triton X-100). Lysates and washed immunoprecipitates were then diluted in SDS-gel loading buffer and separated on 12% SDS-PAGE. Proteins were transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Bio-Rad), which were immunoblotted with anti-GAPDH (1:500), monoclonal anti-GFP (1:5000), anti-PK (1:500), polyclonal anti-HA (Covance, 1:300), or monoclonal anti-HA (Covance, 1:300) antibodies. The secondary antibodies were horseradish peroxidase-conjugated donkey anti-mouse IgG (Amersham Biosciences), donkey anti-goat IgG (Sigma), and donkey anti-rabbit IgG (Amersham Biosciences). Detection was performed using chemiluminescence (Pierce). Untransfected COS7L cells and co-immunoprecipitation assays performed with IgG antibodies were used as negative controls.

Enzymatic Isolation of Ventricular Myocytes

The care and use of animals were according to institutional guidelines. Ventricular myocytes were isolated from adult Sprague-Dawley rats following a previously published protocol (14) using collagenase (type I, Sigma) and pro-tease (Sigma, type XXIV). The procedure resulted in an 80–90% yield of rod-shaped myocytes. Myocytes exhibiting a brick-like shape and clear cross-striations were used for electrophysiology and immunocytochemistry experiments.

Immunofluorescence Microscopy

Isolated cardiomyocytes were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (Sigma; 15 min at room temperature), followed by permeabilization with methanol incubation (100% methanol for 5 min at −20 °C). The cells were washed twice with PBS and incubated with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS for 15 min at room temperature. After two washes with PBS the cells were blocked in 5% donkey PBS/serum and incubated with primary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature. After the coverslips were washed three times in PBS/serum, they were incubated with secondary antibodies for 45 min. Following wash steps (4 ×10 min in PBS) coverslips were mounted and analyzed by laser confocal microscopy (Leica Microsystems). The primary antibodies used were mouse anti-GAPDH (1:300), goat anti-PK (1:500), and rabbit anti-Kir6.2 (76A; 1:100; a kind gift from Dr. A. Tinker, The Rayne Institute, University College, London) (15). The secondary antibodies used were Cy2-conjugated donkey anti-mouse IgG, Cy3-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG, Cy3-conjugated donkey anti-goat IgG, or Cy5-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch). Control groups included incubation with the peptide against which the antibody was raised (when possible) and staining with secondary antibody alone (data not shown).

Electrophysiology

KATP channel currents were recorded from either excised inside-out patches or cell-attached patches (16–18). In the latter configuration, cells were permeabilized locally at one end using 0.1% saponin to obtain the open-cell configuration (19). Pipettes (2–4 MΩ) were filled with (in mM) gluconic acid, 110; KCl, 30; CaCl2, 2; MgCl2, 1; HEPES, 10; ouabain, 0.02; pH 7.4, with KOH. The bath solution contained (in mM): gluconic acid, 110; KCl, 30; EGTA, 1; MgCl2, 1.2; HEPES, 10; pH 7.2, with KOH. Mixtures of glycolytic substrates were prepared in bath solution that additionally contained (in mM): Mg-ATP, 0.09 or 0.1; K-ADP, 0.5; KH2PO4, 0.5. Mixture 1 additionally contained (in mM): glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate (5 mM) and NADP (1 mM), whereas mixture 2 also contained phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP, 5 mM). The Mg2+ activity was calculated by allowing for the stability constants of the various ligands and it was kept constant at 1 mM by addition of MgCl2 as needed. Experiments were also carried with each component of the mixtures individually to test the effect of each substrate on KATP channel activity.

Data were analyzed using the pClamp suite of software (Axon Instruments) and Microcal Origin (Northampton, MA). Data are presented as mean ± S.E. Statistical analysis (SigmaStat, SyStat Inc., Point Richmond, CA) was performed using the one-way analysis of variance for repeated measures followed by Dunnet’s t test. Groups were compared with 100 μM ATP and values of p < 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

Identification of Glycolytic Enzymes as Kir6.2 Interacting Proteins

In a search for novel regulatory subunits of the KATP channel macromolecular protein complex, we conducted a two-hybrid protein-protein interaction screen against a rat cardiac cDNA library, using the Kir6.2 subunit as bait. We used only the cytosolic Kir6.2 C-terminal portion (169–354 amino acids) because many protein-protein interactions occur at intracellular regions. Furthermore, we omitted the last 36 amino acids of the C-terminal to exclude known endoplasmic reticulum retention sequences (20), because the inclusion of these residues would have increased the likelihood of identifying endoplasmic reticulum-resident proteins. Screening of 5 million clones revealed two putative inter-acting proteins to be the glycolytic enzymes GAPDH and TPI, which catalyze two consecutive steps of the glycolytic pathway.

Association of GAPDH, TPI with Kir6.2 in Cultured Cells

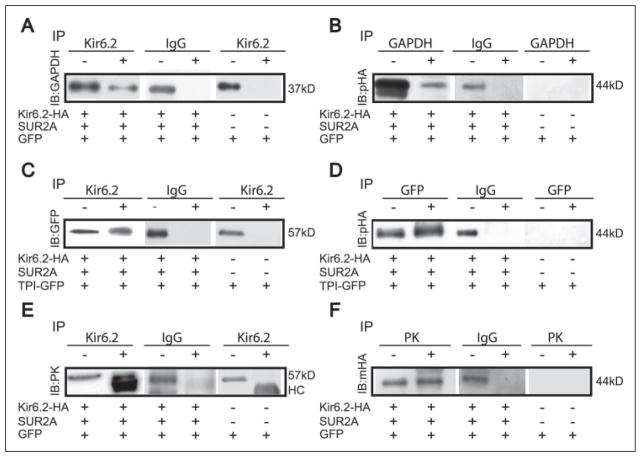

Co-immunoprecipitation assays were performed to verify that the interactions between Kir6.2 and these glycolytic enzymes occur in mammalian cells. COS7L cells were transfected with full-length Kir6.2-HA, SUR2A, and GFP cDNAs. GAPDH is endogenously expressed in COS7L cells, and is detected at an apparent molecular size of ~37 kDa (Fig. 1A). Cells were solubilized, and immunoprecipitation was performed with the anti-Kir6.2 (W62) antibody. Immunoprecipitates were resolved by SDS-PAGE, and immunoblotting was performed using anti-GAPDH antibodies. The band observed at ~37 kDa (Fig. 1A) demonstrates that GAPDH co-immunoprecipitated with Kir6.2 subunits. The reciprocal interaction was also demonstrated. When immunoprecipitation was performed using anti-GAPDH antibodies, we could detect Kir6.2-HA subunits using polyclonal anti-HA antibodies (Fig. 1B).

FIGURE 1. Kir6.2 subunits interact with GAPDH, TPI, and PK in transfected cells.

Lysates of COS7L cells were transfected with Kir6.2-HA and SUR2A, as indicated at the bottom of each blot (GFP was used as a marker of transfection efficiency). Some cells were additionally co-transfected with TPI-GFP cDNA. Kir6.2 subunits were immunoprecipitated (IP) with anti-Kir6.2 (W62) antibody. Other precipitating antibodies used were anti-GAPDH, anti-PK, and anti-GFP antibodies. Immunoprecipitates were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting was performed using anti-GAPDH, monoclonal anti-HA, polyclonal anti-HA, monoclonal anti-GFP, or anti-PK antibodies. As a negative control, IP reactions were performed with untransfected COS7L cells or IgG antibodies. The first lane of each immunoblot (−) is a sample of the cell lysate without an immunoprecipitation reaction to demonstrate that the relevant protein is expressed in the cells. The second lane (+) is obtained from the immunoprecipitate, using the antibodies as indicated. The approximate molecular sizes are indicated (HC, IgG heavy chain).

We constructed a TPI-GFP fusion protein and used anti-GFP antibodies to detect its interaction with Kir6.2 (Fig. 1, C and D). We followed this approach because of lack of suitable anti-TPI antibodies. COS7L cells were transfected as indicated and the TPI-GFP protein was detected as a band migrating with an apparent molecular size of ~57 kDa using a monoclonal GFP antibody. This was observed both in the lysate lane as well as in the immunoprecipitate obtained with an anti-Kir6.2 antibody (Fig. 1C). Reciprocally, immunoprecipitation of TPI-GFP with an anti-GFP antibody enabled the detection of Kir6.2-HA by immunoblotting with a polyclonal anti-HA antibody (Fig. 1D). Co-immunoprecipitation assays when performed in untransfected COS7L cells as a negative control failed to immunoprecipitate GAPDH, or TPI. Co-immunoprecipitation assays carried out with IgG antibodies also did not immunoprecipitate either GAPDH or TPI-GFP. Thus, these data demonstrate that GAPDH and TPI both interact with the Kir6.2 subunit.

Pyruvate Kinase Associates with Kir6.2

Whereas GAPDH and TPI catalyze glycolytic reactions immediately preceding the first ATP-generating step, PK catalyzes the second ATP-generating step of glycolysis. We postulated that PK may also associate with KATP channel subunits because phosphoenolpyruvate, the substrate of PK, inhibits KATP channel activity (18). To test this hypothesis, co-immunoprecipitation assays were performed in cells transfected with Kir6.2-HA and SUR2A (we relied on endogenous expression of PK in COS7L cells, which is observed as a ~57-kDa protein in cell lysates; Fig. 1E). Interaction of PK and Kir6.2 is demonstrated by the finding that PK was detected in the Kir6.2-HA immunoprecipitates. Reciprocally, Kir6.2-HA was detected in the PK immunoprecipitate (Fig. 1F). No interaction was detected in untransfected COS7L cells and in co-immunoprecipitation assays with IgG antibodies.

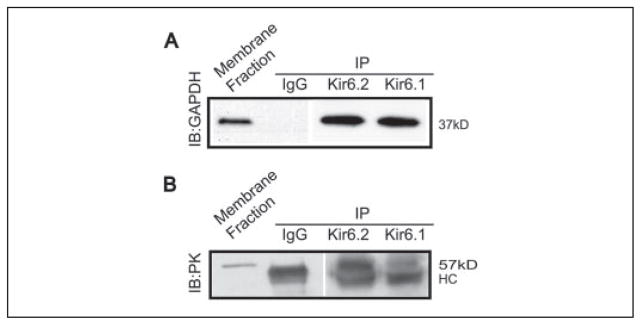

Native Kir6.2 Subunits Interact with GAPDH and PK

We next set out to determine whether interaction of Kir6.2 and these glycolytic enzymes also occurs natively in membrane proteins extracted from rat heart (Fig. 2). Indeed, we were able to detect both GAPDH and PK in an immunoprecipitate obtained using an anti-Kir6.2 antibody (their respective sizes were 37 and 57 kDa). We were not able to demonstrate the reciprocal interaction, presumably because of the relative abundance of GAPDH or PK proteins in cells and the possibility that not all of these glycolytic enzymes interact with KATP channels. Nevertheless, these data support the concept that key glycolytic enzymes (including GAPDH, PK, and presumably TPI) form part of the native multisubunit KATP channel macromolecular protein complex. Interaction does not appear to be limited to the KATP channels containing Kir6.2 subunits, because we also observed robust interaction between native Kir6.1 subunits and both GAPDH and PK.

FIGURE 2. Native Kir6.2 and Kir6.1 subunits associate with GAPDH and PK in rat heart membranes.

Rat heart membrane fractions were used in immunoprecipitating (IP) reactions with anti-Kir6.2 antibodies (W62) or Kir6.1 antibodies (NAF1). The immuno-precipitates were separated on 12% SDS-PAGE and the resulting immunoblots (IB) were probed using anti-GAPDH antibody (A) or anti-PK antibody (B). The positive control for immunoblotting was the cardiac membrane fraction labeled membrane fraction (lane 1 in each case). GAPDH (37 kDa) and PK (57 kDa) were both detected in the Kir6.2 and Kir6.1 immunoprecipitates. Co-immunoprecipitation with IgG antibodies as a negative control failed to detect either GAPDH or PK. Because of cross-reactivity between the polyclonal antibodies used in panel B, IgG heavy chain IgG is observed at ~50 kDa (denoted HC). TPI could not be detected in native tissue because of lack of commercial antibodies.

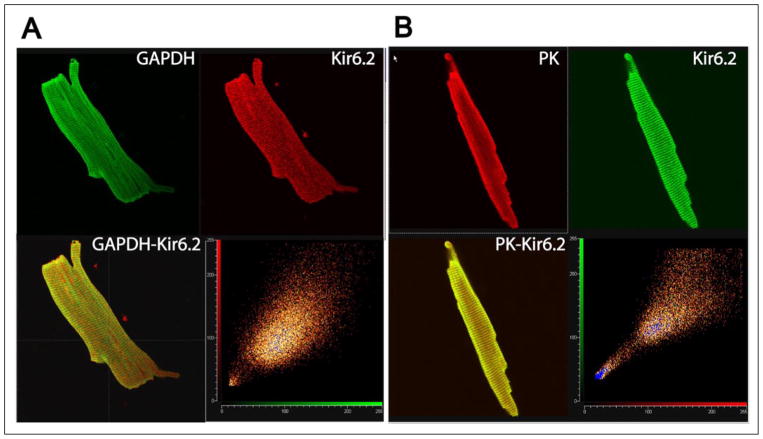

Kir6.2 Subunits Colocalize with GAPDH and PK in Rat Ventricular Myocytes

We performed dual labeling immunocytochemistry experiments to determine whether Kir6.2 and glycolytic enzymes (GAPDH or PK) colocalize in rat ventricular myocytes, as would be predicted if the interactions reported here are of physiological significance. There was extensive overlap in subcellular localization of these proteins (Fig. 3, A and B), demonstrating that glycolytic enzymes largely have a similar subcellular distribution as the Kir6.2 channel subunit. No staining was observed in negative control experiments (peptide incubation or with secondary antibody alone), indicating that the staining was antibody specific (Data not shown). As a further control, we observed identical staining with two separate secondary antibodies.

FIGURE 3. Kir6.2 subunits colocalize with GAPDH and PK in rat ventricular cardiomyocytes.

A, myocytes were double stained with anti-Kir6.2 and anti-GAPDH antibodies (top panel, secondary antibodies, respectively, were Cy-3 conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG, red; and Cy-2 conjugated donkey anti-mouse IgG, green). The confocal image was acquired halfway through the height of the myocyte in the Z-direction. B, cardiomyocytes were double stained with anti-Kir6.2 and anti-PK antibodies. The secondary antibodies used were Cy5-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG (pseudo colored green) and Cy3-conjugated donkey anti-goat IgG (pseudo-colored red). Yellow depicts co-localization. The bottom right panel is a scatter plot of corresponding pixel intensities of the green and red channel.

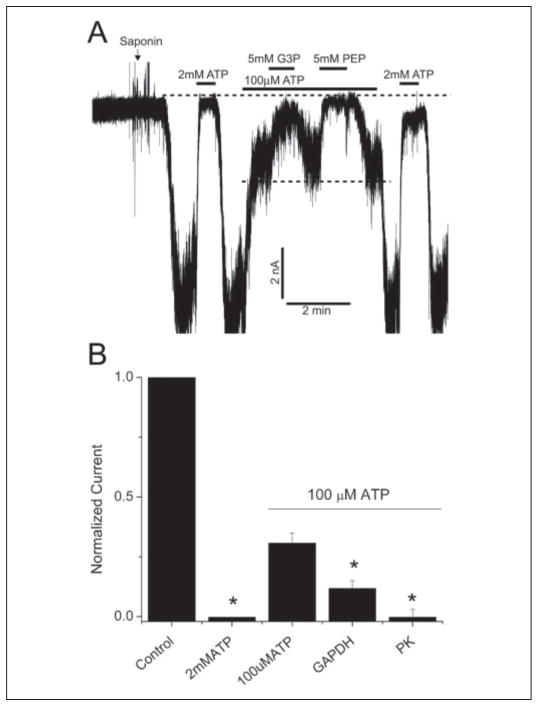

Functional Consequences of the Interaction between Glycolytic Enzymes and Kir6.2 Subunits

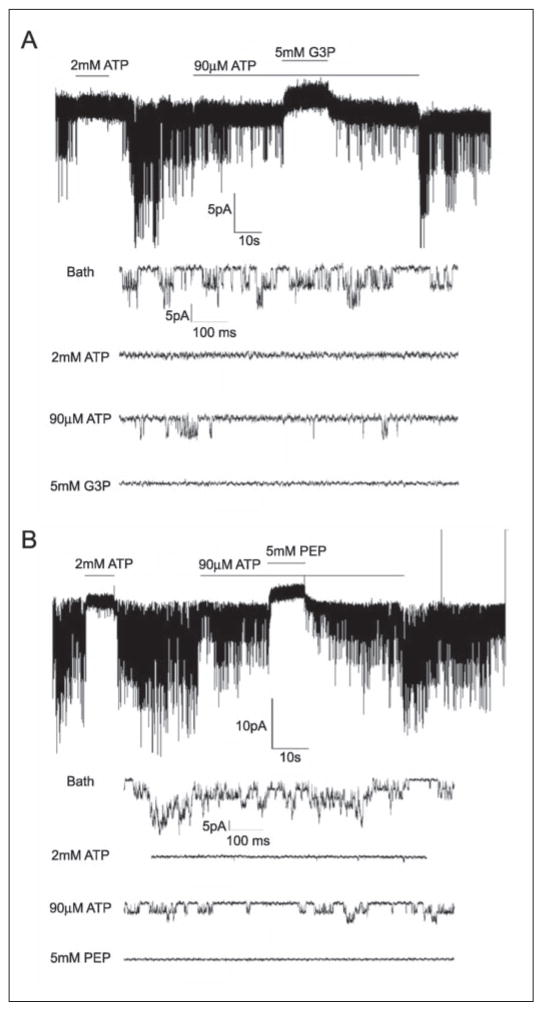

We used the patch clamp technique to investigate the physiological relevance of the interaction between Kir6.2 subunits with glycolytic enzymes. Initially, KATP channel activity was recorded using the open-cell configuration, which allowed the interior of the rat ventricular myocyte to be dialyzed with different solutions, while keeping the intracellular microenvironment of the channel relatively intact (17, 18). Permeabilizing one end of the cell with saponin led to activation of the channels, which was measured in cell-attached patches after a short delay. These channels were identified as KATP channels as they were reversibly blocked when perfusing the cell interior with 2 mM ATP (Fig. 4A). Switching to a solution containing (in mM) 0.1 ATP, 0.5 ADP, and 0.5 KH2PO4 led to partial channel block. Further addition of GAPDH substrates (glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate and the cofactor, NADP) led to prompt and significant inhibition of KATP channels. Similarly, addition of the PK substrate (PEP) also caused a prompt and reversible inhibition of KATP channel activity, consistent with previous reports of KATP channel regulation by PK substrates (18, 21, 22). The degree of channel inhibition by the various interventions, normalized to current in the presence of 100 μM ATP, is shown in Fig. 4B.

FIGURE 4. GAPDH and PK substrates inhibit rat ventricular KATP channels in the open cell-configuration.

A, a representative trace showing the effects of GAPDH and PK substrates on KATP channel activity in rat ventricular myocytes. The intracellular bath solution contained 100 μM ATP to prevent rigor contracture of the myocytes. Substances were added as indicated by the horizontal bars. The dotted lines, respectively, depict the closed state of the channel and the partially blocked state in the presence of 100 μM ATP, 0.5 mM ADP, and 0.5 mM KH2PO4 (depicted as 100 μM ATP for simplicity). The patch potential was −60 mV (pipette potential of +60 mV). The current was filtered at 1 kHz. B, averages of mean patch KATP channel current (mean ± S.E.), normalized to mean patch current in the absence of ATP, under the various conditions, as indicated. n = 6, *, p < 0.05 compared with the 100 μM ATP group. G3P, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate.

Experiments were also performed with excised patches using the inside-out patch clamp configuration (16). KATP channels opened spontaneously following patch excision and their activity was reversibly inhibited by 2 mM ATP (Fig. 5). Application of a “cytosolic” solution containing (in mM) 0.09 ATP, 0.5 ADP, and 0.5 KH2PO4 caused partial inhibition of channel activity. Under these conditions, substrates of GAPDH effectively and reversibly decreased channel activity (in 5 of 8 patches studied). The mean reduction in mean patch current was 99.2 ± 0.8% as compared with the 58.4 ± 14.4% reduction observed in the presence of 90 μM ATP alone. PK substrates also inhibited the channel (in 3 of 4 patches; Fig. 5B). In the presence of PK substrates, KATP channel activity was inhibited by 91.4 ± 8.6% compared with 49.6 ± 12.1% inhibition with 90 μM ATP alone. Application of glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate or PEP in the absence of ADP and KH2PO4 had no effect on KATP channel activity. KATP channels were not blocked by individual application of 5 mM glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate, 5 mM PEP, 1 mM NADP, 0.5 mM MgCl2, or the combination of these components in the absence of ADP and inorganic phosphate (data not shown). Furthermore, iodoacetic acid (1 mM), which is often used to inhibit glycolysis (21), prevented the KATP channel inhibition by glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate (data not shown). Collectively, these patch clamp data demonstrate that the activity of the glycolytic enzymes GAPDH and PK effectively inhibit KATP channels.

FIGURE 5. Substrates of GAPDH and PK suppress KATP channel in excised, inside-out membrane patches.

The bath and pipette solutions were essentially the same as in the previous figure. A, a representative trace showing the effect of GAPDH substrates. Channel activity was blocked by 2 mM ATP and partially inhibited by 90 μM ATP (with 0.5 mM ADP and 0.5 mM KH2PO4). Further addition of glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate (G3P) (5 mM; also containing 1 mM NADP) reversibly inhibited channel activity. Expanded traces below show channel activity under selected conditions at a faster time scale. B, PK substrates (5 mM PEP) also inhibited KATP current. The format is the same as in the previous panel.

DISCUSSION

Our data demonstrate key glycolytic enzymes to be functionally relevant subunits of the KATP channel multisubunit protein complex. Evidence supporting this concept include (i) data from the two-hybrid screen that identified GAPDH and TPI as proteins interacting with the truncated Kir6.2 C terminus; (ii) co-immunoprecipitation of GAPDH, TPI, or PK with Kir6.2 subunits both in heterologous systems and in native tissue; (iii) immunolocalization of Kir6.2 protein with GAPDH and PK in rat ventricular myocytes; and (iv) inhibition of KATP channel activity by substrates of GAPDH or PK in the open-cell configuration and in excised membrane patches.

The KATP Channel as a Macromolecular Protein Complex

Ion channels are increasingly thought to be composed of multisubunit macro-molecular complexes that, in addition to their pore-forming subunits, also include structural and functional accessory subunits (23). Some KATP channel complexes, for example, have been shown to include metabolically active enzymes that regulate their function, including, adenylate kinase, creatine kinase, and lactate dehydrogenase (6–8). Interestingly, KATP channels involved in secretory events directly associate with other subunits that regulate various steps in exocytosis. For example, KATP channels involved in insulin release from the pancreatic β-cell associate with Rim, Piccolo, Epacs, and Ca2+ channel subunits (24), which confers a trimodal regulation of insulin release by cytosolic ATP, Ca2+, and cAMP. There are also reports of their interaction with the vesicle docking protein, syntaxin-1 (25), which may coordinate the sequence of ionic and exocytosis events leading to secretion. Our new data demonstrate that key glycolytic enzymes (GAPDH, TPI, and PK) can associate with Kir6.2 subunits. Given the well described interaction between GAPDH and phosphoglycerate kinase (26–29), it is conceivable that the enzymes involved in each of the two glycolytic ATP generating steps are components of the KATP channel protein complex and that their activity regulates KATP channel opening.

Glycolytically Derived ATP Regulates Membrane Ion Transporters

Although the predominant source of ATP derived from glucose is via oxidative phosphorylation, glycolytically derived ATP may be functionally compartmentalized to preferentially fuel membrane-related processes. This membrane-delimited role of glycolytic enzymes is consistent with their known subcellular localization. There are several reports describing glycolytic enzymes, including GAPDH, PK, and phosphoglycerate kinase to be membrane bound in cell types ranging from glioma cells, intact Ehrlich tumor cells, and red blood cells (30–32). This is also true for cardiac myocytes, where GAPDH and phosphoglycerate kinase bind to sarcolemmal and sarcoplasmic reticular membranes (33, 34). These data are fully consistent with our finding of a membrane-bound localization of GAPDH and PK in rat cardiac ventricular myocytes where they co-localize and physically associate with a KATP channel subunit, Kir6.2 as, respectively, shown by our immunocytochemistry and co-immunoprecipitation data.

There are many examples of membrane-bound ion transporters that are preferentially regulated by glycolytically derived ATP. These include the Na+/K+pump (35–37), the plasma membrane Ca2+pump (38), and the H+-ATPase (39). There is also evidence of a preferential role for glycolysis in some Ca2+ homeostatic pathways by regulating Ca2+ channel activity (40, 41) and sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ transport (21). KATP channels have also been described to be preferentially regulated by glycolytically derived ATP (18, 22). We do not have direct evidence that glycolytically derived ATP directly block KATP channel activity. However, none of the glycolytic intermediates by themselves or application of the co-factors led to KATP channel block. Furthermore, when combined in the absence of ADP and inorganic phosphate, they also did not cause KATP channel block. Thus, the presence of ADP and Pi are required for channel block. Because ADP and inorganic phosphate, at the concentrations used, do not directly block KATP channels (17, 42), the reasonable conclusions are that glycolytic enzyme activity is necessary for channel block. This activity could somehow transmit a conformational signal to KATP channels causing them to close or it could be that the KATP channel is directly blocked by glycolytically produced ATP. We are leaning toward the latter explanation given the nature of this channel to be powerfully blocked by ATP and prior suggestions in the literature for glycolytic ATP to preferentially regulate KATP channel activity (18). If so, our data would provide a molecular basis for this mode of regulation by demonstrating that some of the enzymes involved in the ATP-generating steps of glycolysis physically interact with KATP channel complex.

Physiological and Pathophysiological Relevance of Regulation of KATP Channels by Glycolytically Derived ATP

We found glycolytic enzyme activity to inhibit KATP channels. This may provide a partial explanation for the oscillatory behavior of insulin secretion from glucose-stimulated pancreatic β-cells (43). In other tissues such as the heart, the physiological relevance of this finding is not entirely clear. There is evidence to suggest that functional compartmentalization of ATP may be involved in receptor signaling, for example, the angiotensin II-mediated closure of cardiac KATP channels (44). There is also a curious functional interaction between KATP channels and the Na+/K+ pump, whereby the activity of one determines the activity of the other, most likely by competition for the same glycolytically derived ATP (45–49). KATP channels in vascular smooth muscle and glial cells have Kir6.1 as the pore forming subunit (1), which also interacts with GAPDH and PK. Thus, the possibility is raised that these KATP/NDP channels may also be under the control of glycolytic derived ATP.

Under energy-delimited pathophysiological conditions, such as hypoxia and ischemia, KATP channels open and the action potential duration shortens (50, 51). The protective effects of extracellular glucose and the sensitivity to glycolytic flux of these processes (52, 53) can be reconciled with our finding that enhanced glycolytic flux may block KATP channels and blunt action potential shortening. Regulation of KATP channel activity by glycolytically derived ATP may very well also be important during other pathophysiological states, such as hypertrophy, which decreases the responsiveness of the cardiac KATP channel to glycolytic ATP (54).

Footnotes

This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health Grant R01-HL064838 and the Seventh Masonic District Association, Inc.

The abbreviations used are: GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; TPI, triose-phosphate isomerase; PK, pyruvate kinase; KATP channel, ATP-sensitive potassium channel; COS7L cells, Cercopithecus aethiops (monkey, African green) kidney cells; GFP, green fluorescent protein; HA, hemagglutinin; PEP, phosphoenolpyruvate.

Note Added in Proof—The association of GAPDH with KATP channel sub-units was also described by another group while this manuscript was under review (55).

References

- 1.Seino S, Miki T. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2003;81:133–176. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6107(02)00053-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Inagaki N, Seino S. Jpn J Physiol. 1998;48:397–412. doi: 10.2170/jjphysiol.48.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leonoudakis D, Conti LR, Anderson S, Radeke CM, McGuire LM, Adams ME, Froehner SC, Yates JR, III, Vandenberg CA. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:22331–22346. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400285200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leonoudakis D, Conti LR, Radeke CM, McGuire LM, Vandenberg CA. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:19051–19063. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400284200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bers DM. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2004;37:417–429. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2004.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carrasco AJ, Dzeja PP, Alekseev AE, Pucar D, Zingman LV, Abraham MR, Hodgson D, Bienengraeber M, Puceat M, Janssen E, Wieringa B, Terzic A. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:7623–7628. doi: 10.1073/pnas.121038198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crawford RM, Ranki HJ, Botting CH, Budas GR, Jovanovic A. FASEB J. 2002;16:102–104. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0466fje. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crawford RM, Budas GR, Jovanovic S, Ranki HJ, Wilson TJ, Davies AM, Jovanovic A. EMBO J. 2002;21:3936–3948. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tottey S, Rondet SA, Borrelly GP, Robinson PJ, Rich PR, Robinson NJ. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:5490–5497. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105857200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pountney DJ, Sun ZQ, Porter LM, Nitabach MN, Nakamura TY, Holmes D, Rosner E, Kaneko M, Manaris T, Holmes TC, Coetzee WA. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2001;33:1541–1546. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2001.1407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nakamura TY, Pountney DJ, Ozaita A, Nandi S, Ueda S, Rudy B, Coetzee WA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:12808–12813. doi: 10.1073/pnas.221168498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pond AL, Scheve BK, Benedict AT, Petrecca K, Van Wagoner DR, Shrier A, Nerbonne JM. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:5997–6006. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.8.5997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yoshida H, Feig JE, Morrissey A, Ghiu IA, Artman M, Coetzee WA. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2004;37:857–869. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2004.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nakamura TY, Coetzee WA, Vega-Saenz DM, Artman M, Rudy B. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:H1775–H1786. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.273.4.H1775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cui Y, Giblin JP, Clapp LH, Tinker A. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:729–734. doi: 10.1073/pnas.011370498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hamill OP, Marty A, Neher E, Sakmann B, Sigworth FJ. Pflugers Arch. 1981;391:85–100. doi: 10.1007/BF00656997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kakei M, Noma A, Shibasaki T. J Physiol. 1985;363:441–462. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1985.sp015721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weiss JN, Lamp ST. J Gen Physiol. 1989;94:911–935. doi: 10.1085/jgp.94.5.911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Horie M, Irisawa H, Noma A. J Physiol. 1987;387:251–272. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1987.sp016572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zerangue N, Schwappach B, Jan YN, Jan LY. Neuron. 1999;22:537–548. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80708-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xu KY, Zweier JL, Becker LC. Circ Res. 1995;77:88–97. doi: 10.1161/01.res.77.1.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dubinsky WP, Mayorga-Wark O, Schultz SG. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:C1653–C1659. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.275.6.C1653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Coetzee WA, Amarillo Y, Chiu J, Chow A, Lau D, McCormack T, Moreno H, Nadal MS, Ozaita A, Pountney D, Saganich M, Vega-Saenz DM, Rudy B. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999;868:233–285. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb11293.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shibasaki T, Sunaga Y, Fujimoto K, Kashima Y, Seino S. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:7956–7961. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309068200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pasyk EA, Kang Y, Huang X, Cui N, Sheu L, Gaisano HY. J Biol Chem. 2003 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309667200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ashmarina LI, Muronetz VI, Nagradova NK. Biochem Int. 1984;9:511–521. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sukhodolets MV, Muronetz VI, Tsuprun VL, Kaftanova AS, Nagradova NK. FEBS Lett. 1988;238:161–166. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(88)80248-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sukhodolets MV, Muronetz VI, Nagradova NK. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1989;161:187–196. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(89)91579-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Khoroshilova NA, Muronetz VI, Nagradova NK. FEBS Lett. 1992;297:247–249. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(92)80548-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Daum G, Keller K, Lange K. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1988;939:277–281. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(88)90071-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wernstedt CO, Agren GK, Ronquist G. Cancer Res. 1975;35:1536–1541. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Campanella ME, Chu H, Low PS. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:2402–2407. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409741102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xu KY, Becker LC. J Histochem Cytochem. 1998;46:419–427. doi: 10.1177/002215549804600401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pierce GN, Philipson KD. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:6862–6870. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Glitsch HG, Tappe A. Pflugers Arch. 1993;422:380–385. doi: 10.1007/BF00374294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mercer RW, Dunham PB. J Gen Physiol. 1981;78:547–568. doi: 10.1085/jgp.78.5.547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dizon J, Burkhoff D, Tauskela J, Whang J, Cannon P, Katz J. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:H1082–H1089. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1998.274.4.H1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Paul RJ, Hardin CD, Raeymaekers L, Wuytack F, Casteels R. FASEB J. 1989;3:2298–2301. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.3.11.2528493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lu M, Sautin YY, Holliday LS, Gluck SL. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:8732–8739. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303871200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lorenz JN, Paul RJ. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:H987–H994. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.272.2.H987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Losito VA, Tsushima RG, Diaz RJ, Wilson GJ, Backx PH. J Physiol. 1998;511:67–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.067bi.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lederer WJ, Nichols CG. J Physiol. 1989;419:193–211. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1989.sp017869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Deeney JT, Kohler M, Kubik K, Brown G, Schultz V, Tornheim K, Corkey BE, Berggren PO. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:36946–36950. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105056200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tsuchiya K, Horie M, Watanuki M, Albrecht CA, Obayashi K, Fujiwara H, Sasayama S. Circulation. 1997;96:3129–3135. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.9.3129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hurst AM, Beck JS, Laprade R, Lapointe JY. Am J Physiol. 1993;264:F760–F764. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1993.264.4.F760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kabakov AY. Biophys J. 1998;75:2858–2867. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)77728-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tsuchiya K, Horie M, Haruna T, Ai T, Nishimoto T, Fujiwara H, Sasayama S. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 1998;9:415–422. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.1998.tb00929.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Priebe L, Friedrich M, Benndorf K. J Physiol. 1996;492:405–417. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Urbach V, Van Kerkhove E, Maguire D, Harvey BJ. J Physiol. 1996;491:99–109. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vleugels A, Vereecke J, Carmeliet E. Circ Res. 1980;47:501–508. doi: 10.1161/01.res.47.4.501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kantor PF, Coetzee WA, Carmeliet EE, Dennis SC, Opie LH. Circ Res. 1990;66:478–485. doi: 10.1161/01.res.66.2.478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shigematsu S, Arita M. Cardiovasc Res. 1997;35:273–282. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(97)00092-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nakamura S, Kiyosue T, Arita M. Cardiovasc Res. 1989;23:286–294. doi: 10.1093/cvr/23.4.286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yuan F, Brandt NR, Pinto JM, Wasserlauf BJ, Myerburg RJ, Bassett AL. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1997;29:2837–2848. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1997.0518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jovanović S, Du Q, Russel MC, Budas GR, Streljar I, Jovanović A. EMBO Rep. 2005:848–852. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]