Abstract

This study investigates the possibility of early response assessment based on the FDG-uptake during (chemo-)radiotherapy with respect to overall survival in non-small cell lung cancer.

Methods

FDG-PET/CT imaging was performed prior to radiotherapy and repeated in the second week of radiotherapy treatment for 34 consecutive lung cancer patients treated with (chemo-)radiotherapy. CT volume and SUV parameters of the primary tumor were quantified on both time points. Changes in volume and SUV parameters were correlated to two-year overall survival.

Results

The average decrease of mean SUV in the primary tumor of patients with a 2-year survival was 19±16% and significantly higher (p<0.001) compared to the non-survivors with an increase of 2±12%. A sensitivity and specificity of 63% and 93%, respectively, to separate the two groups was reached for a decrease in mean SUV of 15%. Survival curves were different using this cut-off value (p=0.001). The hazard ratio for a 1% decrease in SUV mean was 1.032 (95% CI: 1.010 – 1.055). Changes in tumor volume defined on CT were not correlated to overall survival.

Conclusion

Early treatment response assessment during radiotherapy with repeated FDG-PET imaging is possible in sequential chemo-radiation as well as concurrent chemo-radiation therapy. A decrease in FDG uptake of the primary tumor correlates with higher long-term overall survival.

Keywords: PET imaging, response assessment, lung cancer, imaging biomarkers

Overall survival (OS) rates in lung cancer have improved, but nevertheless remain low. State of the art treatment of locally advanced stage non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is chemo-radiotherapy. Response assessment in the first weeks of radiotherapy treatment could be useful to tailor the optimal treatment strategy changes for the individual patient. 18F-deoxyglucose (FDG)-PET/CT imaging serves as an imaging technique allowing quantification of tumor response to treatment preceding morphological changes visible on standard CT imaging (1-3).

Several authors have shown the prognostic value of residual FDG uptake in the primary tumor after treatment indicating poor survival (4-7). Early response assessment for chemotherapy treatment has been described by several groups (1, 3, 8-10), but for radiotherapy treatment only few studies have been performed. For high-dose stereotactic body radiotherapy, elevated levels after treatment do not always indicate residual tumor (11). In a smaller study, the added value of FDG-PET/CT imaging during treatment could already distinguish metabolic responders vs. non-responders to therapy based on the maximum SUV during treatment (12). High FDG-uptake values prior to treatment are known to correlate with poor overall survival (13, 14), however the influence of treatment response during (chemo-)radiotherapy is not well described (4, 15-18).

Early treatment response assessment is useful in following patients during the course of treatment. Chemo-radiotherapy is a demanding therapy strategy that has a high burden for the patient, selection of patients up front who will benefit is difficult and an early treatment response assessment could allow adaptation to tailor the treatment for the individual patient.

In the present study, we hypothesized that early changes in the FDG-uptake of the primary tumor are a predictive factor for treatment success. For this purpose, we evaluated all non-small cell lung cancer patients, in a fixed time-period that were treated with curative intent using (chemo-) radiotherapy. We investigated the correlation between metabolic response visualized on a repeated FDG-PET/CT imaging in the second week of radiotherapy and overall survival.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient Characteristics And Dose Prescription

For all non-small cell lung cancer patients from July 2008 to December 2008 that were scheduled for radical radiotherapy we performed a FDG-PET/CT imaging prior to treatment and in the second week of radiotherapy treatment. Patients scheduled for stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) were not included in this study. The study was approved by the appropriate Institutional Review Board. All advanced stages (II-IV) were included in this prospective analysis and treatment was performed according to the clinical protocol. Treatment consisted of radiotherapy only, sequential or concurrent chemo-radiotherapy (RT). The type of chemo for sequential and concurrent chemo-radiotherapy was cisplatin-gemcitabine and cisplatin-vinorelbine, respectively. In both cases, a total of three cycles of chemotherapy were administered. For concurrent chemo-radiotherapy, radiation began at the beginning of the second cycle of chemotherapy. Two cycles of chemotherapy were given during radiotherapy. The treatment consisted of a dose-escalation protocol escalated up to the normal tissue constraints (19). For concurrent chemo-RT, radiotherapy is given in 45 Gy in bi-daily fractions of 1.5 Gy for the first 30 fractions with afterwards a dose-escalation in daily fractions of 2 Gy up to the maximum tolerated normal tissue toxicity until the maximum prescribed dose of 69 Gy was reached. For the sequential chemo-RT patients 3 cycles of chemotherapy were given, and radiotherapy started consisted of fractions of 1.8 Gy given bi-daily up to the normal tissue toxicity and a maximum prescribed dose of 79.2 Gy (19). This radiotherapy scheme was also used for the RT only group.

PET/CT Imaging

FDG-PET/CT imaging (Biograph 40, Siemens Medical Solutions, Knoxville, TN, USA) was performed after one (concurrent chemo-radiotherapy) or typically three cycles (sequential chemo-radiotherapy) of chemotherapy but prior to radiotherapy. Patients were required to fast for at least 6 hours prior to acquisition. Blood glucose levels were determined for all patients and were lower than 10 mmol/l and no correction was applied for the blood glucose level. The scan was made in radiotherapy position and the images were used for accurate tumor delineation and treatment planning. 4D respiratory correlated CT imaging was acquired to visualize possible tumor movement due to respiration that is necessary for radiotherapy treatment planning purposes. A separate contrast-enhanced CT scan was also made during this imaging session. During the second week of radiotherapy the imaging session was repeated using the same immobilization devices and set-up as the pre-treatment FDG-PET/CT imaging procedure. For each patient the injected amount of FDG [MBq] was equivalent to 4*body weight [kg] + 20 [MBq] and patients needed to rest for 60 minutes before image acquisition could start. The PET raw data were corrected for scatter, decay, rebinned and subsequently reconstructed using Ordered Subset Expectation Maximization in 2D (OSEM 2D) using 4 iterations and 8 subsets.

Quantitative Analysis

Quantitative analysis of the FDG-uptake was performed using the standardized uptake value (SUV). The maximum SUV and mean SUV inside the primary tumor were calculated, changes in uptake between time points were analyzed. For the mean SUV inside the primary tumor, the volume is defined by the voxels having an uptake larger than 50% of the maximum SUV inside the primary tumor, we defined this volume as the “PET volume”. The survival of the patients was grouped according to the EORTC criteria of response. A 15% or 25% decrease, depending on the number of chemotherapy cycles in FDG uptake is associated with partial metabolic response using the EORTC criteria for response (20), the PERCIST criteria suggest a 30% decrease for response (21). These cut-off percentages were used in the analysis to separate both groups.

Automatic segmentation methods based on the FDG-PET images could be used to define the tumor volume (22). Additionally, we used the volume defined as the gross tumor volume (GTV) of the primary tumor and for the involved lymph nodes separately based on the PET/CT scan as delineated by the radiation oncologist. These volumes were subsequently used to design the radiotherapy treatment plan. The GTV of the primary tumor as well as the total tumor volume including possible involved lymph nodes were also investigated for correlation with survival.

End-point And Statistical Analysis

The end-point evaluated in this study was the 2-year overall survival rate. All paired analyses were performed using a Wilcoxon-Signed Rank test with p<0.05 indicating statistical significance. Differences between groups were evaluated using a Mann-Whitney U test. Changes in SUV parameters of the mid-treatment scan are calculated relative to the pre-treatment scan. For this threshold, a Cox-regression and survival analysis was performed. Survival curves were displayed by Kaplan Meier curves, survival between groups was compared by log-rank test.

RESULTS

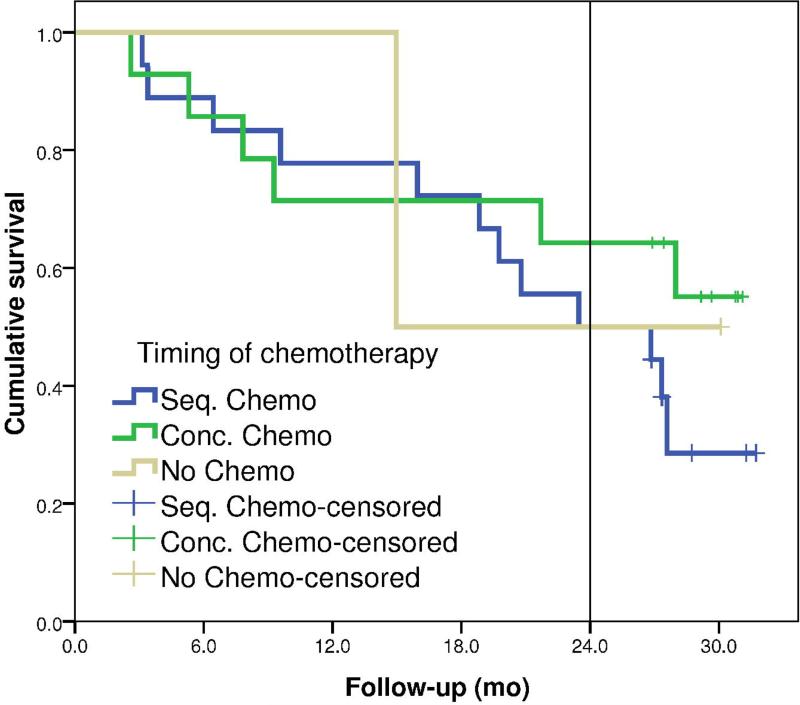

For 35 NSCLC patients, FDG-PET/CT imaging was performed prior to radiotherapy and in the second week of radiotherapy. Imaging time-points and patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1. One patient was excluded from further analysis because this patient had a complete response after 3 cycles of chemotherapy prior to radiotherapy and did not show any tumor mass on the repeated scan. Another patient had 2 primary tumors in the lung, for this patient the lesion with the largest volume was analyzed. Minimum follow-up was 2 years and 2 months with an overall 2-year survival rate for all patients of 56%. Figure 1 shows the survival curves for the different chemotherapy in this study.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics.

| Gender | Male / Female | 24 / 10 |

| Age | Average (SD) [range] | 64.2 (9.4) years [45-81] |

| Stage (TNM 6.0) | IIb | 2 |

| IIIa | 14 | |

| IIIb | 16 | |

| IV* | 2 | |

| Timing chemotherapy | No chemotherapy | 2 |

| Sequential chemo-radiotherapy | 18 | |

| Concurrent chemo-radiotherapy | 14 | |

| Average dose delivered at repeated imaging time-point | Mean ± SD [Range] | 20.7 ± 4.8 Gy [12.0 – 34.2 Gy] |

| Average time between start of radiotherapy and imaging time-point | Mean ± SD [Range] | 8.5 ± 1.9 days [6 – 13 days] |

All stage IV patients were due to a tumor in the ipsilateral lung, but in another lobe.

Figure 1.

Survival curves for the different patients grouped according to the timing of the chemotherapy, either no chemotherapy (N=2), sequential (N=18) or concurrent chemo-radiotherapy (N=14).

The volume of the primary tumor was on average 61.4±56.7 cm3 and decreased to 56.4±49.2 cm3 in the second week of treatment, a fractional decrease of 5.8±19.3% in volume. The total tumor volume (primary tumor and nodes) for all patients including those with nodal involvement (N=24) was 81.9±63.3 cm3 and 77.8±59.3 cm3 for the pre-treatment and mid-treatment time-points. The average relative decrease in total tumor volume was 4.1±15.3%. The PET volume prior to treatment was on average 17.5±20.3 cm3, for the mid-treatment time-point this volume was 16.5±18.0 cm3, a fractional change of 7.5±44.2%.

The maximum SUV and mean SUV inside the PET volume for the entire population was 10.0±4.9 and 6.6±3.2 for the pre-treatment scan compared to 8.8±4.2 and 5.9±2.9 for the mid-treatment scan, respectively. Maximum and mean SUV parameters did not reach significance in a Cox-regression analysis. The fractional change between both time-points was −10.8±22.3% and −10.4±23.6% for maximum and mean SUV, respectively.

The average change in the CT volume of the primary tumor or the total tumor volume including the involved lymph nodes was not significantly different for the patient surviving 2 years or not (p=0.215 and p=0.918, respectively), also see Table 2. Also the change in PET volume was not significant (p=0.215).

Table 2.

Volume and SUV characteristics for all patients.

| Survival > 2 years (N=19) | Survival < 2 years (N=15) | Significance | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline scan Mean ± SD [range] | Repeated scan Mean ± SD [range] | Change [%] | Baseline scan Mean ± SD [range] | Repeated scan Mean ± SD [range] | Change [%] | p-value of change between survivors vs. non-survivors | |

| Volume primary tumor [cm3] | 56.1 ± 61.1 [3.1 – 189] | 51.1 ± 54.2 [1.3 – 185.2] | −10.0 ± 18.7 [−65.9 – 24.0] | 68.1 ± 51.8 [1.1 – 182] | 63.1 ± 43.0 [1.6 – 150] | −0.5 ± 19.3 [−25.8 – 47.2] | 0.215 |

| Total tumor volume [cm3] | 71.8 ± 64.3 [19 – 216] | 67.1 ± 55.6 [18 – 185] | −2.7 ± 12.0 [−23.5 – 28.3] | 94.6 ± 61.9 [11 – 218] | 91.3 ± 62.9 [11 – 255] | −2.4 ± 14.0 [−25.8 – 31.0] | 0.918 |

| PET volume [cm3] | 17.9 ± 24.9 [2 – 94] | 15.4 ± 22.2 [2 – 95] | −4.5 ± 26.0 [−44.9 – 56.6] | 16.9 ± 13.1 [2 – 55] | 18.0 ± 11.3 [3 – 41] | 22.6 ± 57.5 [−34.2 – 153] | 0.215 |

| Maximum SUV primary tumor [-] | 11.4 ± 5.6 [4.5 – 26.8] | 9.2 ± 4.6 [2.1 – 17.3] | −19.3 ± 21.6 [−54.2 – 24.9] | 8.2 ± 3.2 [2.6 – 14.1] | 8.3 ± 3.8 [2.5 – 15.3] | +0.1 ± 18.9 [−47.2 – 26.2] | 0.015 |

| Mean SUV inside PET volume | 7.7 ± 3.7 [3.0 – 17.3] | 6.1 ± 3.0 [1.4 – 11.5] | −20.2 ± 20.5 [−54.3 – 14.6] | 5.4 ± 2.1 [1.6 – 9.1] | 5.6 ± 2.7 [1.6 – 9.8] | +2.1 ± 21.9 [−51.9 – 44.2] | 0.007 |

| SUV peak [-] | 9.4 ± 4.7 [3.1 – 20.7] | 7.5 ± 3.9 [1.3 – 14.3] | −21.3 ± 18.4 [−57.2 – 6.7] | 6.8 ± 2.7 [1.9 – 11.6] | 7.2 ± 3.7 [2.0 – 14.2] | +5.4 ± 29.3 [−49.5 – 87.3] | 0.003 |

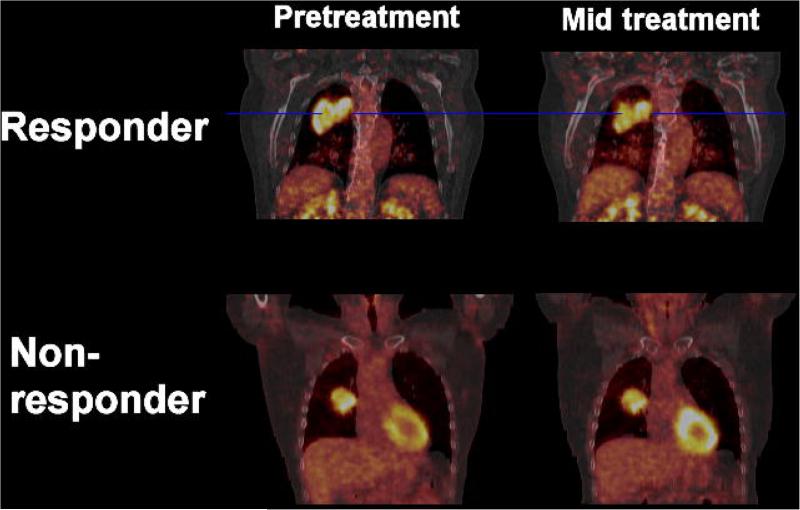

The average change in mean SUV inside the PET volume was −20.2±20.5% for the survivors, compared to +2.1±21.9% for patients being dead at 2 years (p=0.007). For the maximum SUV inside the GTV these numbers were −12.9±23.1% vs. −4.2±18.5% (p=0.015), respectively. A detailed overview of all parameters is given in Table 2. Figure 2 shows an example of the FDG-uptake in the primary tumor prior and during treatment for both a metabolic responder and a non-responder.

Figure 2.

Patient example of metabolic responder (top) vs. non-responder (bottom) for both the pre-treatment (left) and the mid-treatment (right) FDG-PET/CT scan. SUV window levels are scaled equal per patient.

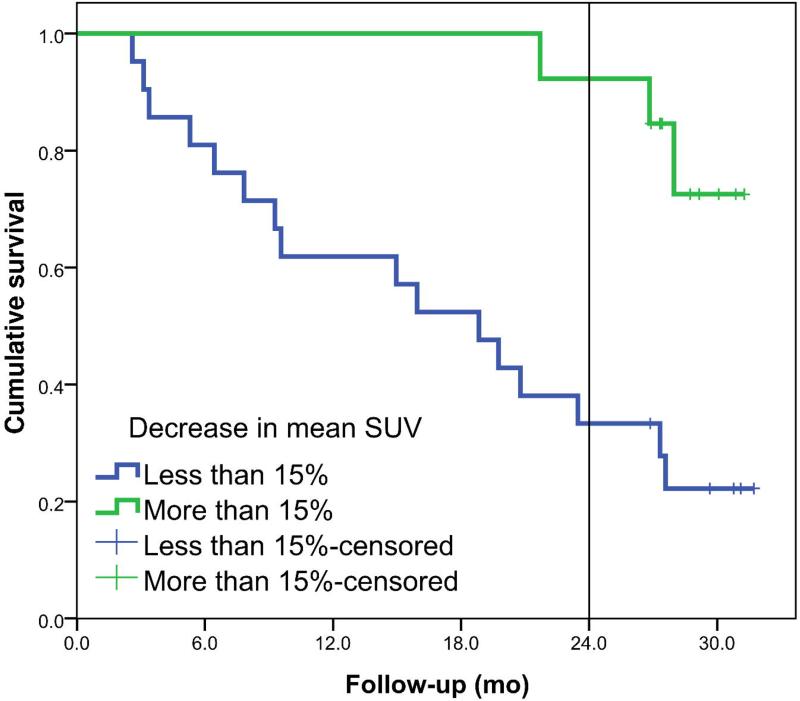

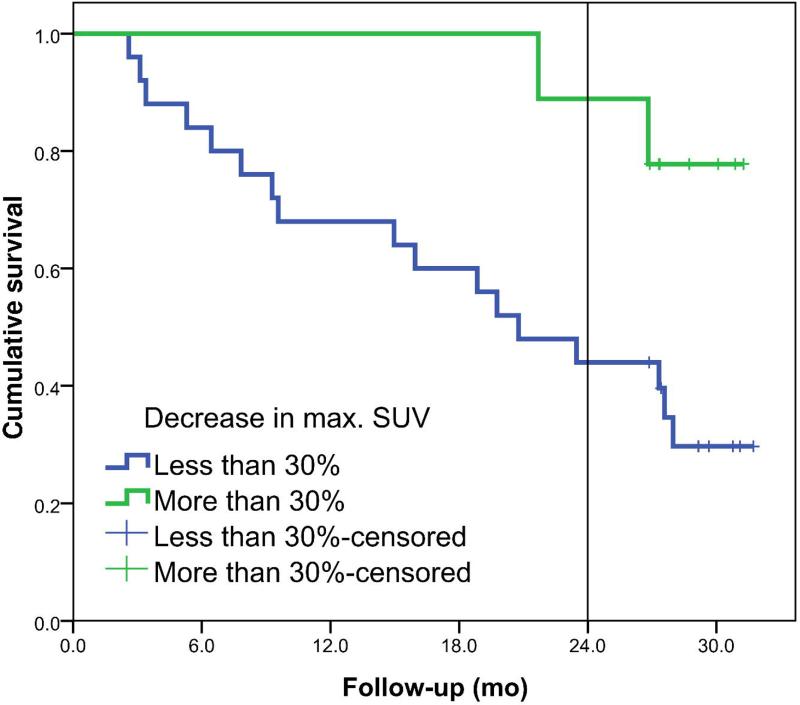

The EORTC criteria for partial metabolic response of 15% are used to divide the dataset in two groups. For the patients with a decrease of more than 15% in SUV, median OS was not yet reached and 2-year overall survival was 92% compared to a median OS of 19 months and a 33% 2-year OS, respectively, for the patients with a decrease in mean SUV smaller than 15%.

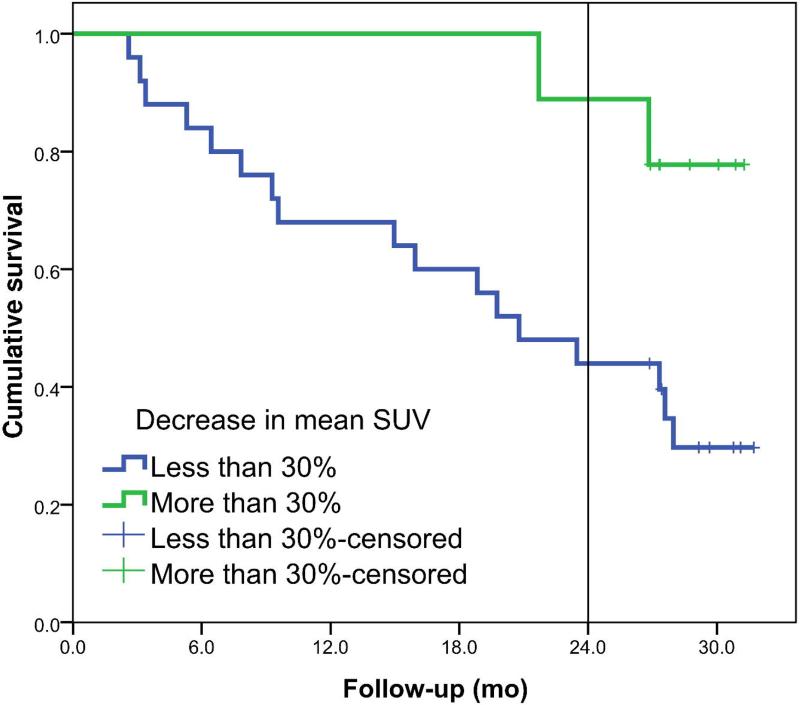

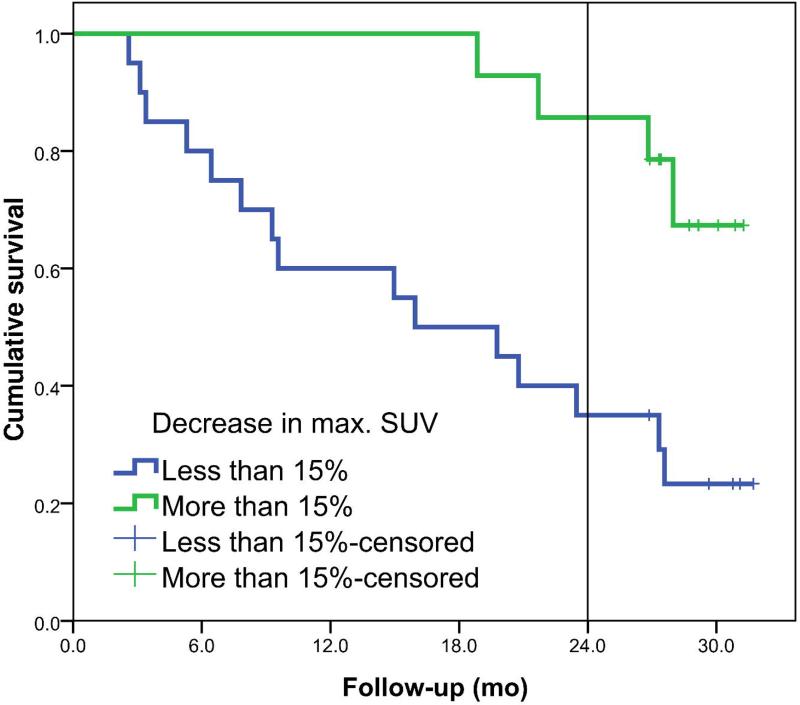

The Kaplan-Meier curves are shown in Figure 3 for the decrease in mean SUV of the primary tumor. Survival between the two groups was statistically different with a HR of 1.032 (95% CI: 1.010 - 1.055) per percent decrease in mean SUV. At the cut-off point of 15%, 25% and 30% decrease, a sensitivity of 63%, 47% and 42%, respectively and a specificity of 93%, 93% and 93%, respectively, were reached. Figure 4 shows the survival plots for the change in maximum SUV of the primary tumor. The HR for percentage decrease in SUVmax was 1.027 (95% CI: 1.005 - 1.049) per percent change in maximum SUV.

Figure 3.

Left panel shows the overall survival plots for metabolic responders (N=13) and non-responders (N=21) defined for a decrease of at least 15% in mean SUV of the primary tumor (p=0.001). Right panel shows survival plots if a cut-off value of 30% decrease in mean SUV is used, 5 metabolic responders vs. 29 non-responders (p=0.026).

Figure 4.

Left panel shows the overall survival plots for metabolic responders (N=14) and non-responders (N=20) defined for a decrease of at least 15% in maximum SUV of the primary tumor (p=0.004). Right panel shows survival plots if a cut-off value of 30% decrease in maximum SUV is used, 9 metabolic responders vs. 25 non-responders (p=0.026).

DISCUSSION

This is one of the first studies showing the added value of repeated FDG-PET imaging early during chemo-radiotherapy treatment as a predictive factor for survival that is preceding CT changes (23, 24). A decrease in metabolic activity of the primary tumor already in the second week of treatment is shown to be predictive for survival. The simplicity of calculating the average FDG-uptake inside the primary tumor is one of the factors that could be exploited in clinical practice for individualizing treatment.

The EORTC criteria (20) indicate a partial metabolic response after one cycle of chemotherapy if the FDG uptake decreases more than 15%. This number is confirmed in our study to correlate with a more long-term end-point: 2 year overall survival. The PERCIST criteria (21) suggest a 30% decrease to classify a partial response, however these criteria are also based on the large variability caused by technical issues, different scanners used, reconstruction protocols all decreasing reproducibility of the repeated imaging. We have minimized these factors by using the same PET/CT scanner, acquisition protocols and procedure for both imaging time points. Reproducibility (e.g. test-retest) studies however showed already a 10-15% variability using the same equipment and repeated imaging for the same patient on different days (21).

The number of patients (N=34) in this study was however too limited for an in depth subgroup analysis. A future larger study is necessary for this that might be able to provide even better prognostic and predictive factors that could incorporate stage or histology dependent factors.

Van Baardwijk et al (12) showed that non-responders had an increase in maximum SUV early into treatment. We did not observe this trend in our population. There could be several reasons for this. Our imaging time point is in the second week of treatment, whereas the maximum in their publication was found in the first week. Another likely cause is that in our study almost all patients were treated with sequential or concurrent chemotherapy prior or during treatment. Chemotherapy is known to suppress the FDG-uptake signal inside tumors (25, 26). Kong et al quantified changes in FDG uptake after 45 Gy of radiotherapy dose (18). They found a correlation between early metabolic response that correlated with 3-4 month response based on CT imaging, but they did not perform a survival analysis. Recently, Huang et al investigated also a group of NSCLC patients with repeated imaging after approximately 40 Gy and short-term outcome using the RECIST criteria at 4 weeks after the end of treatment was used (16).

Changes in maximum or mean SUV allowed prediction of the treatment outcome. However these studies have imaging time-points in the second half of the radiotherapy course making treatment adaptation less effective because there is not much room left to adapt or improve the treatment. Our study shows that changes in metabolic activity already appear and can be detected in the second week of treatment allowing more than half of the treatment schedule for treatment improvement and individualization.

To make a full characterization of the changes in SUV uptake, one needs to have a look at the individual voxels inside the tumor and have a response assessment per voxel (27). For this a detailed voxel-tracking method is necessary, which was outside the scope of this study. Another option for a more comprehensive tumor quantification is the use of multiple tracers for example FLT and F-MISO in addition to FDG as described by Vera et al (28). Also interesting is an approach described by Van Velden et al who looked at cumulative histograms of the SUV distribution, heterogeneity and response that might be characterized from these histograms (29). This might be an alternative approach to full voxel-based response analysis. Also the definition of the PET volume using a cut-off of 50% of the maximum SUV is highly sensitive to the maximum SUV and might also underestimate the true tumor volume. For the repeat PET scan, therapy induced reduced activity might again enlarge this volume because of reduced maximum uptake. Newly developed methods, e.g. gradient-based, might give a more robust volume definition (30, 31).

To use the information of early response in clinical practice one could investigate the added value of an adaptive protocol based on the results of a FDG-PET scan during treatment. For the responders, treatment could be continued as planned. In the future, we might envisage designing trials that lower the radiotherapy dose in very favorable responders with the aim to decrease toxicity. For the non-responders, treatment could be intensified, either by using a new treatment plan making use of the possible volume reductions already observed compared to the planning scan. This might allow dose-escalation of this smaller volume with the same level of normal (lung) toxicity. Volume changes in the second week of treatment are however small, but may trigger additional imaging later during the course of radiotherapy where larger volume changes are reported (18, 32-36). However, one has to be careful with this type of dose-escalation and shrinking field approaches because microscopic disease might not be treated effectively. Therefore such an approach should be investigated in a clinical trial. The data presented in this study could serve as an estimation of which cut-off value for FDG-decrease should be used. The imaging biomarker (e.g. difference in mean SUV of the primary tumor) might then become a predictive marker that could be used in a patient individualized treatment setting.

CONCLUSION

Early treatment response assessment with repeated FDG-PET imaging in the second week of radiotherapy is possible by assessing the decrease in the average FDG-uptake in the primary tumor. A large decrease in FDG-uptake already early during treatment correlates with improved overall survival.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This study was performed within the framework of CTMM, the Center for Translational Molecular Medicine (www.ctmm.nl), project AIRFORCE number 03O-103. This research was supported by EU FP7 funding (project ARTFORCE). One of the authors (W.v.E.) would like to acknowledge funding (KWF fellowship) from the Dutch Cancer Society.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: none

REFERENCES

- 1.Hoekstra CJ, Stroobants SG, Smit EF, et al. Prognostic relevance of response evaluation using [18F]-2-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose positron emission tomography in patients with locally advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:8362–8370. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Ruysscher D, Kirsch CM. PET scans in radiotherapy planning of lung cancer. Radiother Oncol. 2010;96:335–338. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2010.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weber WA, Petersen V, Schmidt B, et al. Positron emission tomography in non-small-cell lung cancer: prediction of response to chemotherapy by quantitative assessment of glucose use. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:2651–2657. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aerts HJ, Bosmans G, van Baardwijk AA, et al. Stability of 18F-deoxyglucose uptake locations within tumor during radiotherapy for NSCLC: a prospective study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;71:1402–1407. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.11.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abramyuk A, Tokalov S, Zophel K, et al. Is pre-therapeutical FDG-PET/CT capable to detect high risk tumor subvolumes responsible for local failure in non-small cell lung cancer? Radiother Oncol. 2009;91:399–404. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mac Manus MP, Hicks RJ, Matthews JP, et al. Positron emission tomography is superior to computed tomography scanning for response-assessment after radical radiotherapy or chemoradiotherapy in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:1285–1292. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.07.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aerts HJ, van Baardwijk AA, Petit SF, et al. Identification of residual metabolic-active areas within individual NSCLC tumours using a pre-radiotherapy (18)Fluorodeoxyglucose-PET-CT scan. Radiother Oncol. 2009;91:386–392. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2009.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Geus-Oei LF, van der Heijden HF, Visser EP, et al. Chemotherapy response evaluation with 18F-FDG PET in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. J Nucl Med. 2007;48:1592–1598. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.043414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee DH, Kim SK, Lee HY, et al. Early prediction of response to first-line therapy using integrated 18F-FDG PET/CT for patients with advanced/metastatic non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2009;4:816–821. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181a99fde. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nahmias C, Hanna WT, Wahl LM, Long MJ, Hubner KF, Townsend DW. Time course of early response to chemotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer patients with 18F-FDG PET/CT. J Nucl Med. 2007;48:744–751. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.106.038513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matsuo Y, Nakamoto Y, Nagata Y, et al. Characterization of FDG-PET images after stereotactic body radiation therapy for lung cancer. Radiother Oncol. 2010;97:200–204. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2010.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Baardwijk A, Bosmans G, Dekker A, et al. Time trends in the maximal uptake of FDG on PET scan during thoracic radiotherapy. A prospective study in locally advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients. Radiother Oncol. 2007;82:145–152. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2007.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berghmans T, Dusart M, Paesmans M, et al. Primary tumor standardized uptake value (SUVmax) measured on fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) is of prognostic value for survival in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): a systematic review and meta-analysis (MA) by the European Lung Cancer Working Party for the IASLC Lung Cancer Staging Project. J Thorac Oncol. 2008;3:6–12. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31815e6d6b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim SJ, Kim YK, Kim IJ, Kim YD, Lee MK. Limited prognostic value of dual time point F-18 FDG PET/CT in patients with early stage (stage I & II) non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Radiother Oncol. 2011;98:105–108. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2010.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang H-q, Yu J-m, Meng X, Yue J-b, Feng R, Ma L. Prognostic value of serial [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose PET-CT uptake in stage III patients with non-small cell lung cancer treated by concurrent chemoradiotherapy. Eur J Radiol. 2011;77:92–96. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2009.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang W, Zhou T, Ma L, et al. Standard uptake value and metabolic tumor volume of (18)F-FDG PET/CT predict short-term outcome early in the course of chemoradiotherapy in advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s00259-011-1838-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van Loon J, Offermann C, Ollers M, et al. Early CT and FDG-metabolic tumour volume changes show a significant correlation with survival in stage I-III small cell lung cancer: A hypothesis generating study. Radiother Oncol. 2011;99:172–175. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2011.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kong FM, Frey KA, Quint LE, et al. A pilot study of [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography scans during and after radiation-based therapy in patients with non small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:3116–3123. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.3747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Baardwijk A, Wanders S, Boersma L, et al. Mature results of an individualized radiation dose prescription study based on normal tissue constraints in stages I to III non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1380–1386. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.7221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Young H, Baum R, Cremerius U, et al. Measurement of clinical and subclinical tumour response using [18F]-fluorodeoxyglucose and positron emission tomography: review and 1999 EORTC recommendations. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) PET Study Group. Eur J Cancer. 1999;35:1773–1782. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(99)00229-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wahl RL, Jacene H, Kasamon Y, Lodge MA. From RECIST to PERCIST: Evolving Considerations for PET response criteria in solid tumors. J Nucl Med. 2009;50(Suppl 1):122S–150S. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.057307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wanet M, Lee JA, Weynand B, et al. Gradient-based delineation of the primary GTV on FDG-PET in non-small cell lung cancer: a comparison with threshold-based approaches, CT and surgical specimens. Radiother Oncol. 2011;98:117–125. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2010.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de Geus-Oei LF, van der Heijden HF, Corstens FH, Oyen WJ. Predictive and prognostic value of FDG-PET in nonsmall-cell lung cancer: a systematic review. Cancer. 2007;110:1654–1664. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lin P, Koh ES, Lin M, et al. Diagnostic and staging impact of radiotherapy planning FDG-PET-CT in non-small-cell lung cancer. Radiother Oncol. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2011.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yamamoto Y, Nishiyama Y, Monden T, et al. Correlation of FDG-PET findings with histopathology in the assessment of response to induction chemoradiotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2006;33:140–147. doi: 10.1007/s00259-005-1878-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eschmann SM, Friedel G, Paulsen F, et al. Repeat 18F-FDG PET for monitoring neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with stage III non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2007;55:165–171. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2006.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lambin P, Petit SF, Aerts HJ, et al. The ESTRO Breur Lecture 2009. From population to voxel-based radiotherapy: exploiting intra-tumour and intra-organ heterogeneity for advanced treatment of non-small cell lung cancer. Radiother Oncol. 2010;96:145–152. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2010.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vera P, Bohn P, Edet-Sanson A, et al. Simultaneous positron emission tomography (PET) assessment of metabolism with (1)F-fluoro-2-deoxy-d-glucose (FDG), proliferation with (1)F-fluorothymidine (FLT), and hypoxia with (1)fluoro-misonidazole (F-miso) before and during radiotherapy in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC): a pilot study. Radiother Oncol. 2011;98:109–116. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2010.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van Velden FH, Cheebsumon P, Yaqub M, et al. Evaluation of a cumulative SUV-volume histogram method for parameterizing heterogeneous intratumoural FDG uptake in non-small cell lung cancer PET studies. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2011;38:1636–1647. doi: 10.1007/s00259-011-1845-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee JA. Segmentation of positron emission tomography images: some recommendations for target delineation in radiation oncology. Radiother Oncol. 2010;96:302–307. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2010.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hatt M, Cheze le Rest C, Turzo A, Roux C, Visvikis D. A fuzzy locally adaptive Bayesian segmentation approach for volume determination in PET. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2009;28:881–893. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2008.2012036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Feng M, Kong FM, Gross M, Fernando S, Hayman JA, Ten Haken RK. Using fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography to assess tumor volume during radiotherapy for non-small-cell lung cancer and its potential impact on adaptive dose escalation and normal tissue sparing. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;73:1228–1234. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.10.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van Elmpt W, Ollers M, van Herwijnen H, et al. Volume or position changes of primary lung tumor during (chemo-)radiotherapy cannot be used as a surrogate for mediastinal lymph node changes: the case for optimal mediastinal lymph node imaging during radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;79:89–95. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.10.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kupelian PA, Ramsey C, Meeks SL, et al. Serial megavoltage CT imaging during external beam radiotherapy for non-small-cell lung cancer: observations on tumor regression during treatment. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;63:1024–1028. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.04.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Spoelstra FO, Pantarotto JR, van Sornsen de Koste JR, Slotman BJ, Senan S. Role of adaptive radiotherapy during concomitant chemoradiotherapy for lung cancer: analysis of data from a prospective clinical trial. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;75:1092–1097. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fox J, Ford E, Redmond K, Zhou J, Wong J, Song DY. Quantification of tumor volume changes during radiotherapy for non-small-cell lung cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;74:341–348. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.07.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]