Abstract

The skin represents the primary interface between the host and the environment. This organ is also home to trillions of microorganisms that play an important role in tissue homeostasis and local immunity1–4. Skin microbial communities are highly diverse and can be remodelled over time or in response to environmental challenges5–7. How, in the context of this complexity, individual commensal microorganisms may differentially modulate skin immunity and the consequences of these responses for tissue physiology remains unclear. Here we show that defined commensals dominantly affect skin immunity and identify the cellular mediators involved in this specification. In particular, colonization with Staphylococcus epidermidis induces IL-17A+ CD8+ T cells that home to the epidermis, enhance innate barrier immunity and limit pathogen invasion. Commensal-specific T-cell responses result from the coordinated action of skin-resident dendritic cell subsets and are not associated with inflammation, revealing that tissue-resident cells are poised to sense and respond to alterations in microbial communities. This interaction may represent an evolutionary means by which the skin immune system uses fluctuating commensal signals to calibrate barrier immunity and provide heterologous protection against invasive pathogens. These findings reveal that the skin immune landscape is a highly dynamic environment that can be rapidly and specifically remodelled by encounters with defined commensals, findings that have profound implications for our understanding of tissue-specific immunity and pathologies.

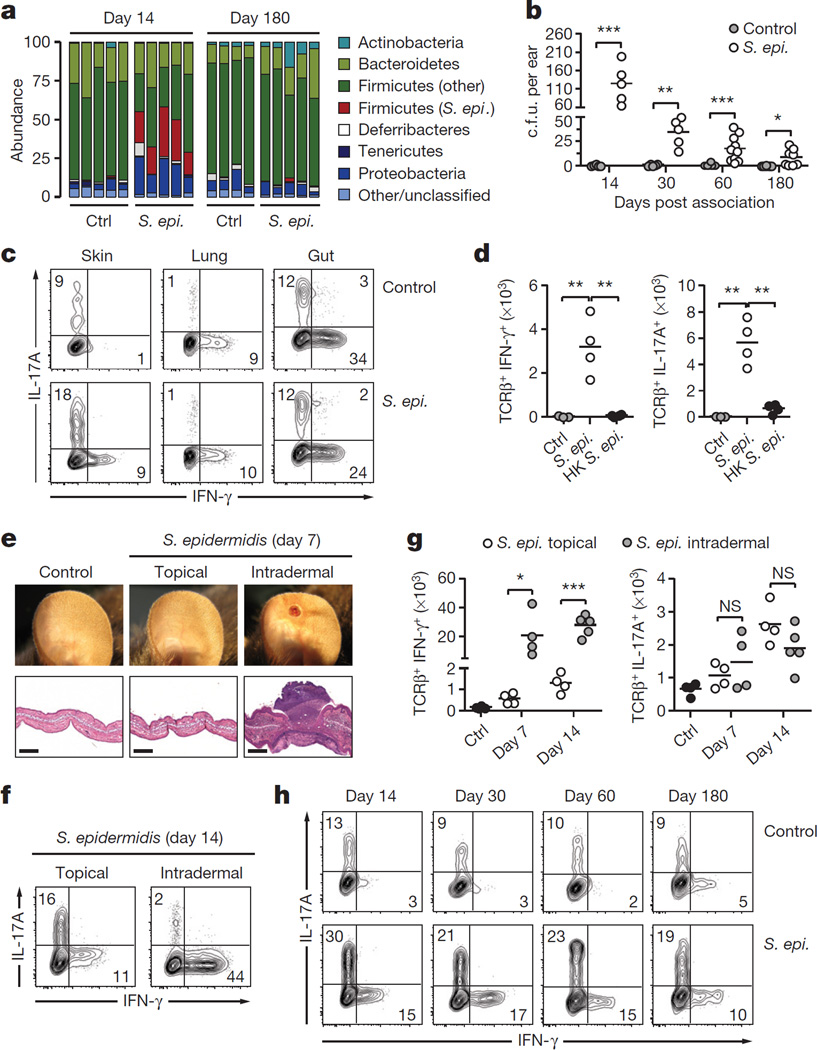

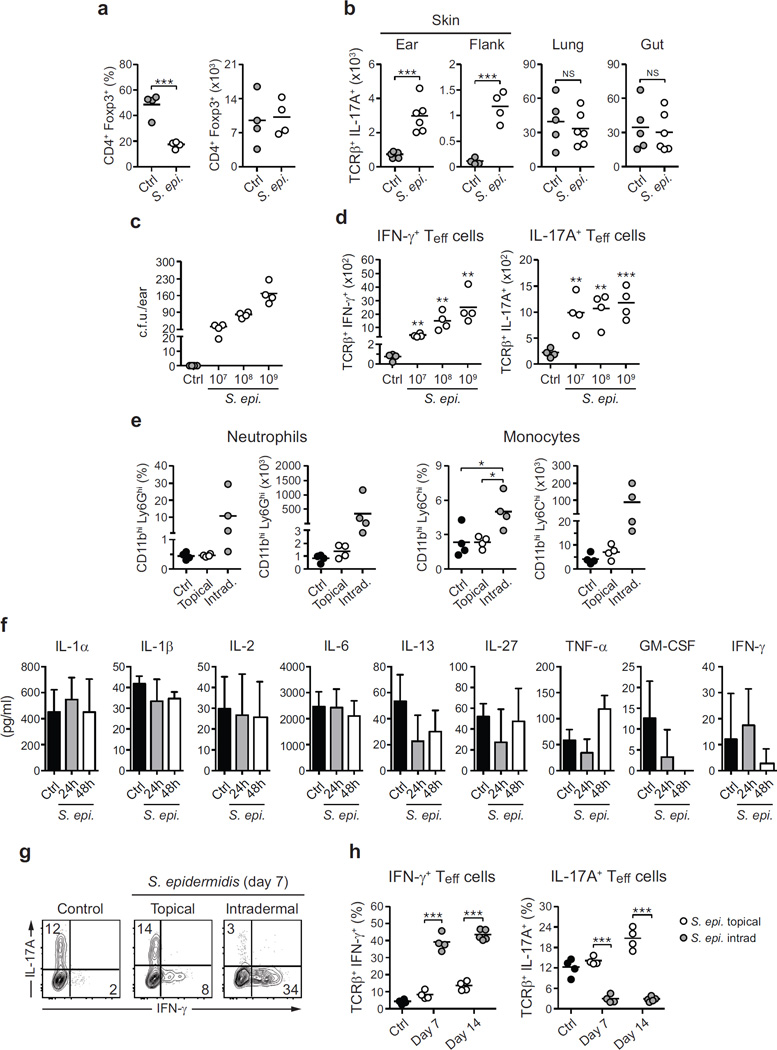

We first assessed whether individual commensal species could modulate immunity in the context of pre-existing microbial communities. Despite the presence of a diverse microbiota, the skin of specific pathogen free (SPF) mice was permissive to long-term colonization with S. epidermidis5 at all skin sites analysed (Fig. 1a, b). At 2 weeks post topical association with as low as 1.3 × 106 colony-forming units (c.f.u.) per cm2, levels of IL-17A- and IFN-γ-expressing T cells but not Foxp3+ regulatory T cells were significantly increased at several skin sites analysed (Fig. 1c, d and Extended Data Fig. 1a–d). Long-term accumulation of IL-17A-expressing T cells was not observed at sites distal to the skin and required colonization with live bacteria (Fig. 1c, d, h and Extended Data Fig. 1b). Furthermore, in contrast to responses to intradermal inoculation of S. epidermidis, commensal responses were not associated with inflammation (Fig. 1e–h and Extended Data Fig. 1e–h). Thus, an encounter with a new commensal can lead to a robust but non-inflammatory accumulation of effector T cells in the skin.

Figure 1. Remodelling of skin immunity by commensal colonization.

a, Relative abundance of bacterial phyla in mouse skin 14 and 180 days after S. epidermidis topical application. Each bar represents the percentage of sequences in operational taxonomic units (OTUs) assigned to each phylum for an individual mouse. Ctrl, control. b, Enumeration of colony-forming units (c.f.u.) from the ears after S. epidermidis application (n = 5–10 per group). c, IFN-γ and IL-17A production by skin, lung or gut effector (CD45+ TCRβ+ Foxp3−) T cells in unassociated (control) and S. epidermidis (S. epi.)-associated mice at day 14. d, Absolute numbers of skin IFN-γ+ or IL-17A+ effector T cells in unassociated mice (control, n = 3) and mice topically associated with live (S. epi., n = 4) or heat-killed (HK S. epi., n = 4) S. epidermidis at day 14. e, Representative images and histopathological comparison of the ear pinnae of unassociated (control), topically associated (topical) or intradermally inoculated (intradermal) mice at day 7. Scale bars, 250 µm. f, g, Frequencies and absolute numbers of skin IFN-γ+ or IL-17A+ effector T cells after topical application (n = 4) or intradermal inoculation (n = 4–5) of S. epidermidis. h, IFN-γ and IL-17A production by skin effector T cells in unassociated and S. epidermidis-associated mice at different time points. Results are representative of 2–3 independent experiments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 as calculated by Student’s t-test.

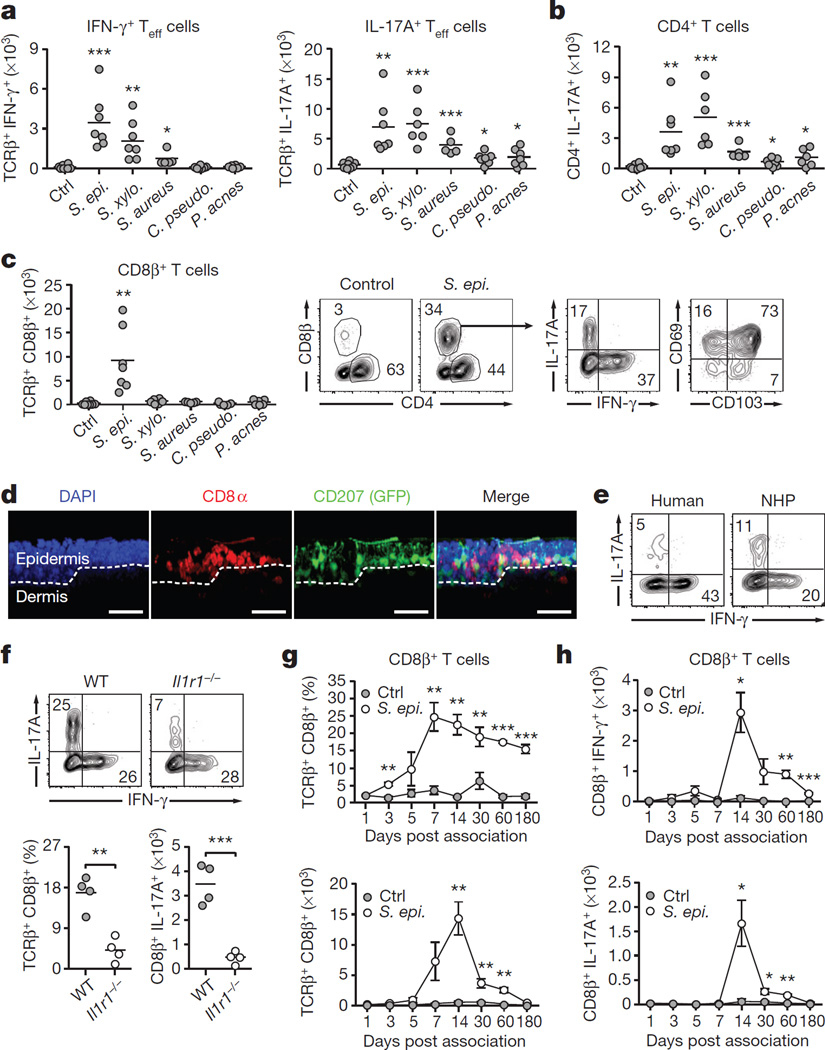

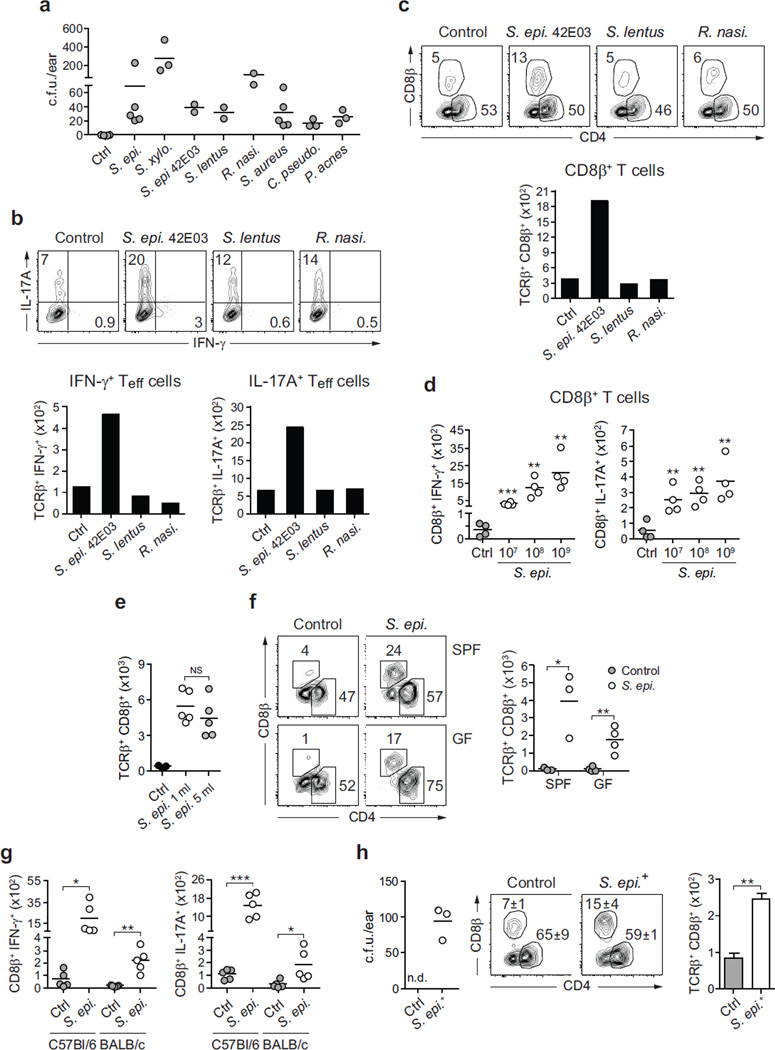

We next assessed the capacity of other constituents of the human (Corynebacterium pseudodiphtheriticum, Propionibacterium acnes and Staphylococcus aureus) and murine (Staphylococcus xylosus, Staphylococcus lentus, Rothia nasimurium and S. epidermidis 42E03) skin microbiota to influence T-cell responses (Extended Data Fig. 2a). Six out of eight bacteria tested increased the number of skin IL-17A+ T cells and half of the commensals also increased the number of IFN-γ-expressing T cells (Fig. 2a and Extended Data Fig. 2a, b). Thus, the induction of cytokines, and in particular IL-17A, is a relatively conserved response of the skin to an encounter with a new commensal.

Figure 2. Distinct commensal species impose specific immune signatures in the skin.

a, Mice were left unassociated (Ctrl, n = 8) or topically associated with S. epidermidis (n = 7), S. xylosus (n = 7), S. aureus (n = 5), C. pseudodiphtheriticum (n = 7) or P. acnes (n = 6). Absolute numbers of skin IFN-γ+ or IL-17A+ effector T cells are shown 2 weeks after first association. b, Absolute numbers of skin IL-17A+ CD4+ effector T cells from mice in a. c, Absolute numbers of skin CD8β+ effector T cells from mice in a. Flow plots show the frequencies of CD4+ and CD8β+ effector T cells in unassociated and S. epidermidis-associated mice, the IFN-γ and IL-17A production, and the expression of CD69 and CD103 by CD8β+ T cells in associated mice. d, Representative imaging volume projected along the x axis of ears from Langerin–GFP (green fluorescent protein) reporter mice 14 days post S. epidermidis application. Scale bars, 30 µm; DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole. e, CD3+ CD8+ IFN-γ+ and CD3+ CD8+ IL-17A+ T cells in normal human (n = 1) and non-human primate (NHP) skin (n = 8). f, Frequencies and absolute numbers of total CD8β+ or IL-17A+ CD8β+ effector T cells in the skin of wild-type (WT, n = 4) and Il1r1−/− (n = 4) mice after S. epidermidis application. g, h, Frequencies and absolute numbers (mean ± s.e.m.) of total CD8β+, IFN-γ+ CD8β+ and IL-17A+ CD8β+ effector T cells in the skin over time following S. epidermidis application (n = 3–5 per time point). Results in a–c are a compilation of 2–3 experiments. Results in d–h are representative of two independent experiments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 as calculated by Student’s t-test.

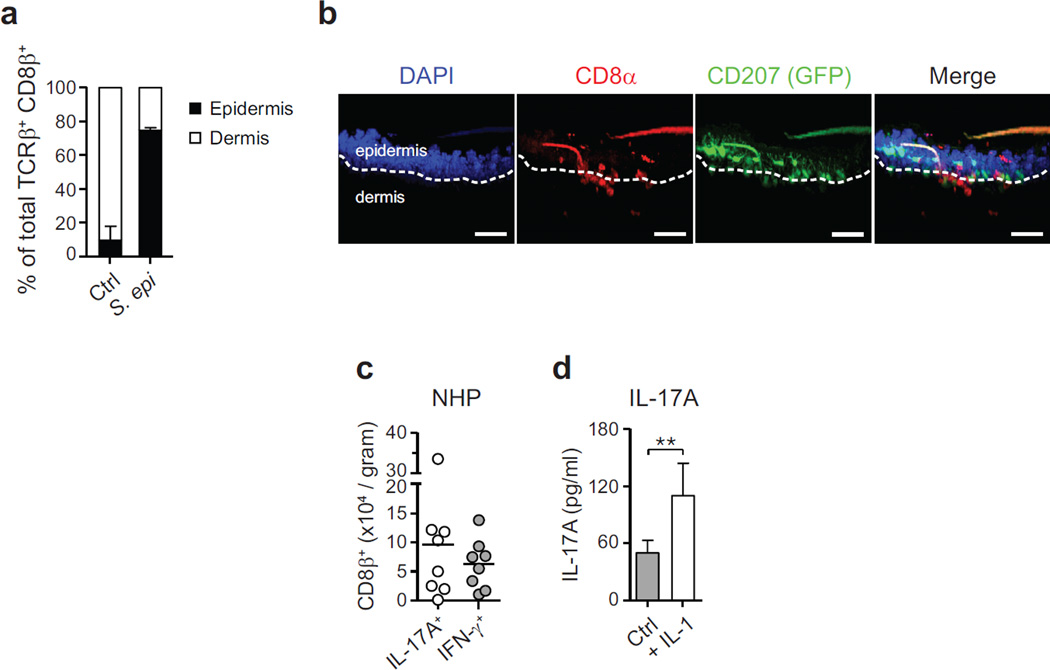

The majority of αβ T cells found in murine skin are CD4+ T cells with few resident CD8+ T cells8 (Fig. 2b, c). Notably, S. epidermidis isolates were uniquely able to increase the number and frequencies of CD8+ T cells in the skin in both SPF and germ-free conditions and in response to an application dose as low as 1.3 × 106 c.f.u. per cm2 (Fig. 2c and Extended Data Fig. 2c–h). Similarly to tissue-resident memory (TREM) cells induced by viral challenges9, clusters of CD8+ T cells preferentially localized to the basal epidermis or in close proximity to the epithelial layer and expressed CD103 and CD69 (Fig. 2c, d and Extended Data Fig. 3a, b). On the other hand, commensal-evoked CD8+ T cells have a distinct cytokine profile characterized by the production of either IL-17A or IFN-γ and in contrast to virally induced TREM cells that localize to the site of injury, commensal-induced CD8+ T cells accumulated at all skin sites analysed (Fig. 2c and Extended Data Fig. 1b). Although rarely seen at other body sites, Tc17 cells (a subset of CD8+ T cells) can be found in healthy non-human primate and human skin (Fig. 2e and Extended Data Fig. 3c). This discrete response provided us with the opportunity to explore the factors controlling a commensal-driven immune specification.

In germ-free mice, commensals promote T-cell responses through IL-1 (ref. 2). Consistently, mice deficient in IL-1R1 contained significantly fewer skin IL-17A+ CD8+ T cells post S. epidermidis association, and in vitro stimulation of purified S. epidermidis-evoked CD8+ T cells with IL-1 boosted IL-17A release (Fig. 2f and Extended Data Fig. 3d). CD8+ T-cell response peaked at 2 weeks post association, at which point the number of cells slowly contracted, although increased frequencies were maintained up to 6months post application (Fig. 2g, h).

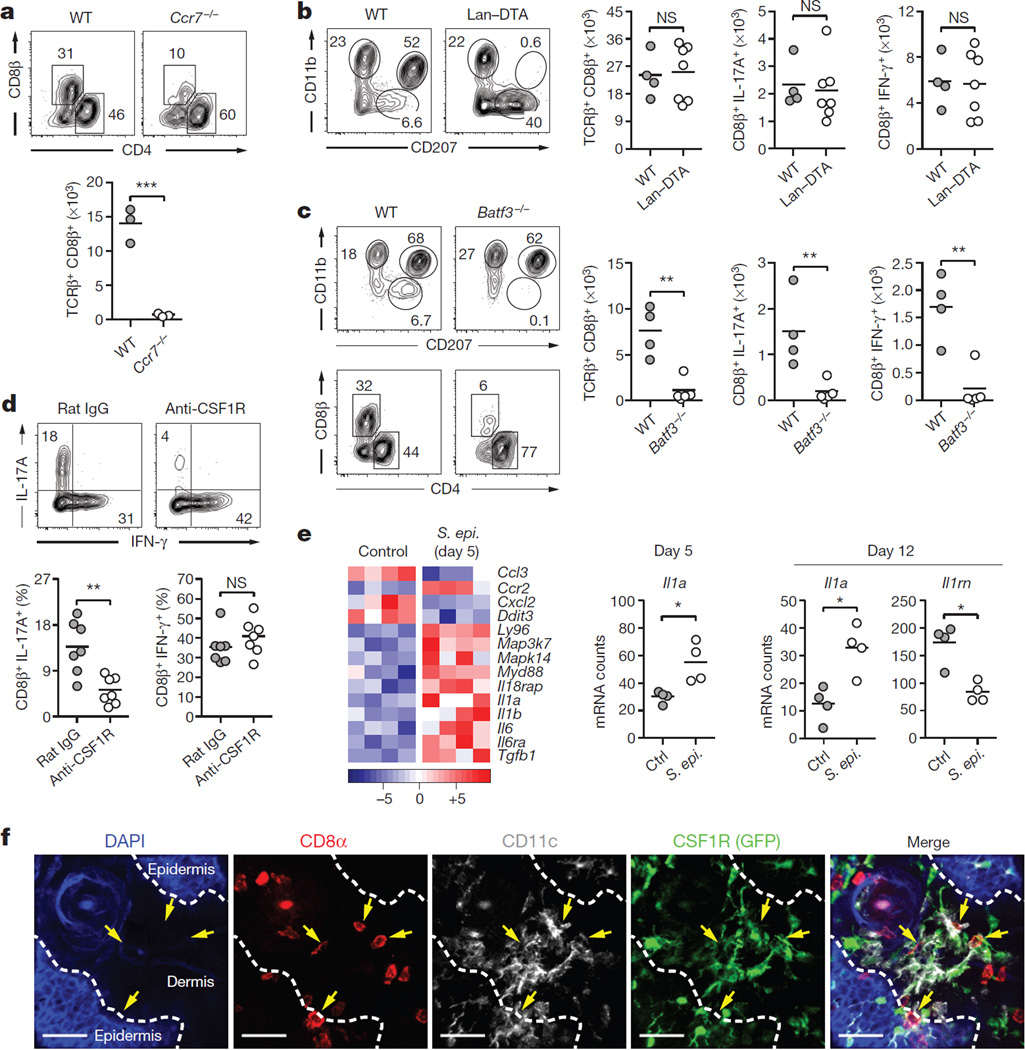

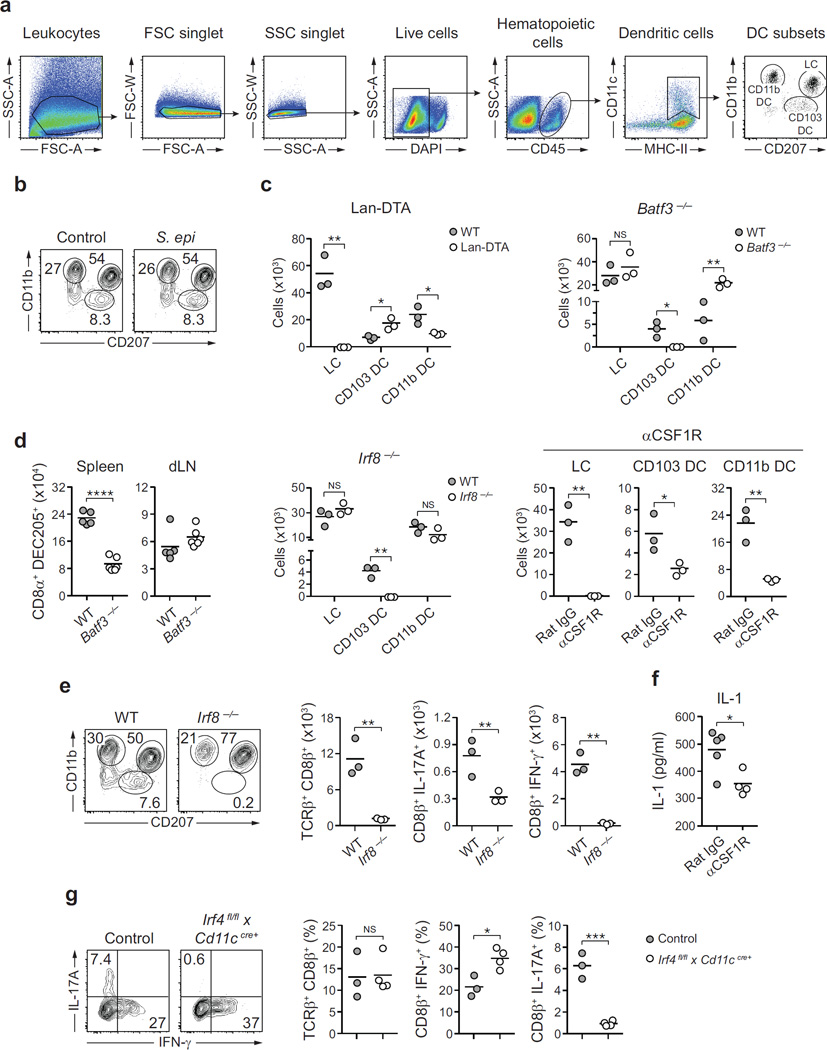

Dendritic cells are exquisite sensors of their environment and previous studies uncovered a functional specialization of defined dendritic cell subsets in their capacity to drive unique immune modules10. What remains unexplored is how this specialization could account for the capacity of the host to regulate defined aspects of its relationship with the microbiota. In the skin, dendritic cells could potentially be exposed to the microbiota via emission of dendrites through epithelial cells and/ or to commensal products passively diffusing at invaginations such as hair follicles, which have more permissive cell adhesions11. Supporting the idea that CD8+ T-cell accumulation post association depends on migratory dendritic cells12, the response was largely abolished in Ccr7−/− mice (Fig. 3a). Frequencies of skin dendritic cell subsets13 were not affected by S. epidermidis application, indicating that the induction of Tc17 cells did not result from altered dendritic cell frequencies (Extended Data Fig. 4a, b).

Figure 3. Distinct dendritic cell subsets cooperate to mediate host– commensal interaction in the skin.

a, Frequencies and absolute numbers of skin CD8β+ effector T cells in wild-type (WT, n = 3) and Ccr7−/− (n = 3) mice 2 weeks post first S. epidermidis topical application. b, Phenotypic analysis of skin MHCII+ CD11c+ cells and absolute numbers of skin total CD8β+, IFN-γ+ CD8β+ and IL-17A+ CD8β+ effector T cells in wild-type (n = 4) and Langerin–diphtheria toxin subunit A (Lan–DTA, n = 7) mice after S. epidermidis application. NS, not significant. c, Phenotypic analysis of MHCII+ CD11c+ cells and effector T cells in the skin of wild-type (n = 4) and Batf3−/− (n = 5) mice after S. epidermidis application. Graphs illustrate the absolute numbers of skin total CD8β+, IFN-γ+ CD8β+ and IL-17A+ CD8β+ effector T cells. Results shown in a–c are representative of 2–3 experiments. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 as calculated by Student’s t-test. d, Frequencies of IFN-γ+ CD8β+ and IL-17A+ CD8β+ effector T cells in S. epidermidis-associated mice treated with anti-CSF1R (n = 7) or rat IgG isotype control (n = 7). Graphs are a compilation of the results of two independent experiments. **P < 0.01 by Student’s t-test. e, Heat map of genes statistically differentially expressed in skin CD11b+ CD103− dendritic cells from topically associated versus unassociated mice. Graphs summarize Il1a and Il1rn mRNA counts at day 5 and/or day 12 in CD11b+ CD103− dendritic cells. Each column of the heat map and each dot of the graph represent gene expression from a biological replicate comprised of skin cells pooled and purified from 5 mice (n = 4 biological replicates, *P < 0.05). f, Representative imaging volume projected along the z axis of ears from CSF1R GFP reporter mice 14 days post application, showing contact (arrows) between CD8α+ and CD11c+ CSF1R+ cells. Scale bars, 40 µm.

Mice constitutively deficient in Langerhans cells14 mounted T-cell responses to S. epidermidis in a manner comparable to their littermate controls (Fig. 3b and Extended Data Fig. 4c, and data not shown). Cross-presenting CD103+ dendritic cells15 depend on the expression of IRF8 and BATF3 for their development10,16 while CD11b+ dendritic cells require CSF1 for their development and maintenance17,18 and IRF4 for the formation of peptide–MHC (major histocompatibility complex) class II complexes19. Making use of this differential requirement for transcription or survival factors, we assessed the relative contribution of these two dendritic cell subsets to CD8+ T-cell responses. The selective defect in skin-resident CD103+ dendritic cells (but not lymph-node-resident CD8α+ dendritic cells; Extended Data Fig. 4d) in our Batf3−/− colony allowed us to evaluate the direct contribution of these cells. Batf3−/− and Irf8−/− mice failed to develop CD8+ T-cell responses following colonization compared to control mice, highlighting a non-redundant role for CD103+ dendritic cells in the induction of CD8+ T-cell responses to S. epidermidis (Fig. 3c and Extended Data Fig. 4c, e).

Treatment of mice with ananti-CSF1R antibody led to a marked reduction in Langerhans cells and skin CD11b+ dendritic cells, as well as in skin IL-17A+ CD8+ T cells (Fig. 3d and Extended Data Fig. 4c). As the specific deletion of Langerhans cells had no consequence on T-cell responses to commensals (Fig. 3b), these results suggest that the immune effect observed was due to CD11b+ dendritic cells. A large fraction of S. epidermidis-evoked CD8+ T cells were in close contact with CSF1R+ CD11c+ cells in the skin and these cells were the most transcriptionally altered (including increases in Il1a and Il1b transcripts and a decrease in Il1rn transcripts) following S. epidermidis application (Fig. 3e, f and data not shown). Furthermore, anti-CSF1R antibody treatment significantly reduced skin IL-1 levels post association (Extended Data Fig. 4f). In mice conditionally depleted of IRF4 in their dendritic cell compartment19, CD8+ T cells accumulated in the skin but failed to produce IL-17A (Extended Data Fig. 4g). Together, these results support the idea that through their capacity to produce IL-1, CD11b+ dendritic cells could promote the induction and/or maintenance of IL-17A expression by CD8+ T cells. Thus, cooperation between skin-resident dendritic cells promotes and tunes responses to a defined commensal (Fig. 4g).

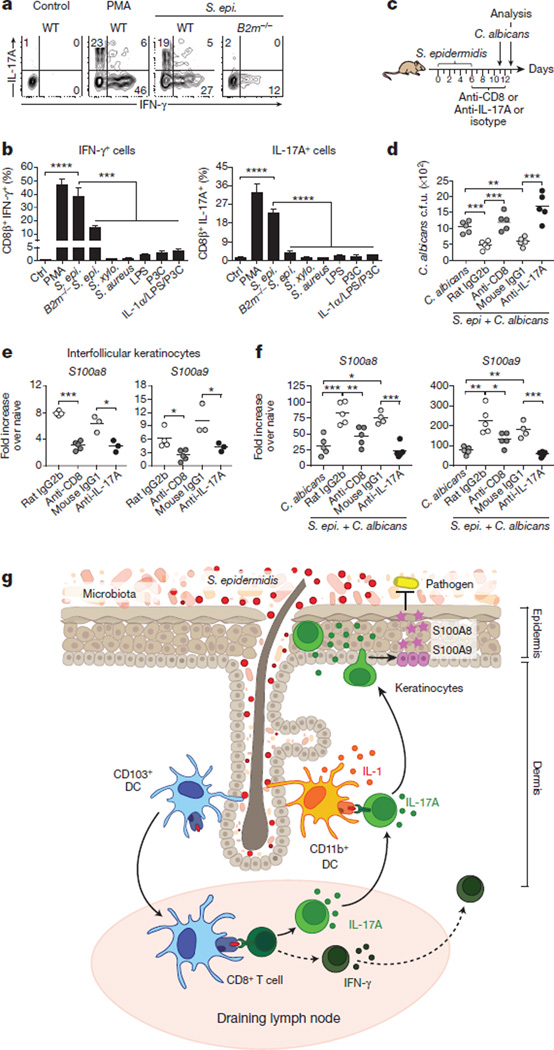

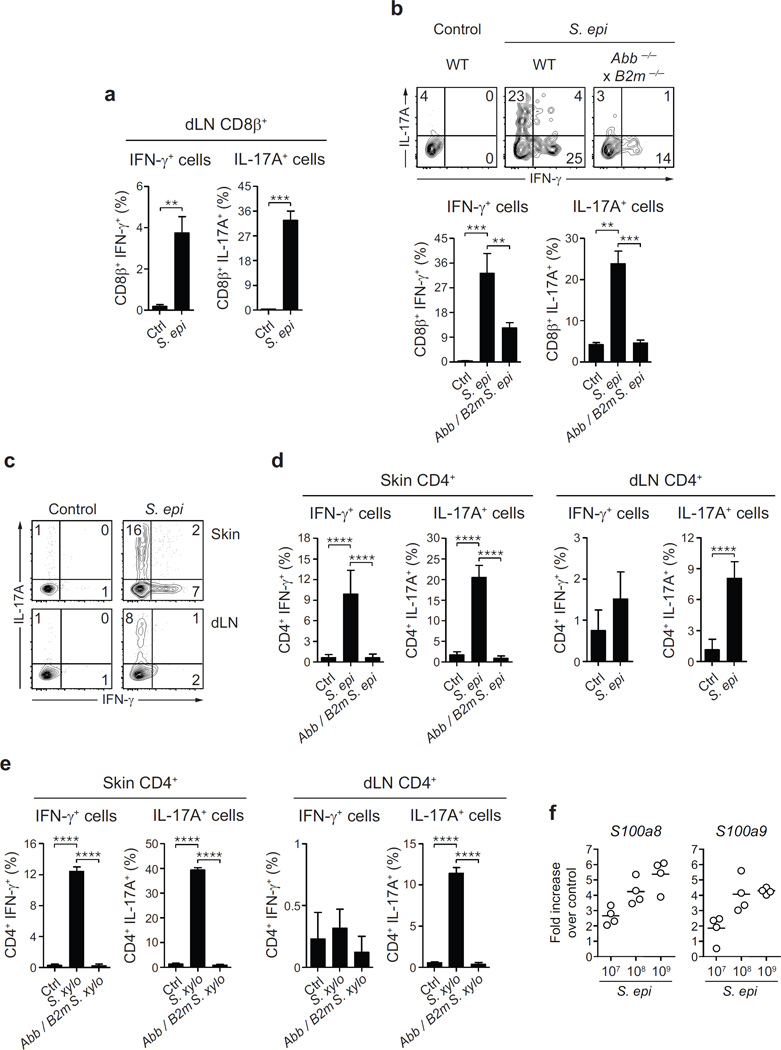

Figure 4. Commensal-driven CD8+ T cell response is specific for S. epidermidis antigen.

a, CD8β+ effector T cells from the skin of S. epidermidis associated mice were co-cultured with wild-type (WT) or B2m−/− splenic dendritic cells (SpDC) untreated (Ctrl) or pre-incubated with heat-killed S. epidermidis, S. xylosus or S. aureus; LPS, Pam3Cys (P3C) or IL-1α. Flow plots illustrate the frequencies of IFN-γ+ CD8β+ and IL-17A+ CD8β+ T cells in overnight co-cultures. PMA, naive SpDC + PMA/ionomycin. b, Frequencies of IFN-γ+ CD8β+ and IL-17A+ CD8β+ T cells in overnight co-cultures as described in a (mean ± standard deviation of triplicate cultures). Data are representative of 2–3 independent experiments. ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 as calculated by Student’s t-test. c, Unassociated or S. epidermidis-topically associated mice were infected with C. albicans and treated with anti-CD8, anti-IL-17A or corresponding isotype control antibodies. d, Enumeration of C. albicans colony-forming units from dorsal skin biopsies from mice in c 2 days post C. albicans infection. e, S100a8 and S100a9 gene expression (fold increase over naive unassociated) by interfollicular keratinocytes purified from the ears of mice 2 weeks after S. epidermidis application. f, S100a8 and S100a9 gene expression (fold increase over naive unassociated and uninfected) in dorsal skin biopsies from mice in c 2 days post C. albicans infection. Results in d–f are representative of two independent experiments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 as calculated by Student’s t-test. g, Model of the response of the skin immune system to colonization with a new commensal. Skin-resident CD103+ dendritic cells (DC) may acquire commensals or commensal-derived antigens by reaching into skin appendages or via capture of soluble factors. CD8+ T cells primed by CD103+ dendritic cells in the lymph node, migrate to the skin and are locally tuned by IL-1 produced by CD11b+ dendritic cells. Commensal-specific CD8+ T cells can enhance antimicrobial defence of keratinocytes in an IL-17 dependent manner. Dotted lines indicate points that are not addressed in this work.

Of note, healthy human skin contains approximately 20 billion effector lymphocytes of unknown specificity20. To address the possibility that T cells accumulating in murine skin in response to S. epidermidis were commensal specific, CD8+ T cells were purified from the skin or regional lymph nodes and exposed to dendritic cells loaded with S. epidermidis antigens. Exposure of S. epidermidis-loaded dendritic cells to CD8+ T cells promoted potent IL-17A and IFN-γ production (Fig. 4a, b and Extended Data Fig. 5a). In contrast, stimulation with IL-1α or other bacterial antigens or ligands failed to induce cytokine production, and S. epidermidis-loaded dendritic cells did not promote cytokine release by activated T cells of irrelevant specificity (Fig. 4b and data not shown). A fraction of IFN-γ production by CD8+ T cells was still detectable in the absence of β2-microglobulin-dependent MHC class I presentation (Fig. 4a, b and Extended Data Fig. 5b), suggesting that some of the IFN-γ-producing CD8+ T cells may be responding in a bystander manner or in a β2-microglobulin-independent manner21. However, IL-17A was not observed following exposure to B2m−/− dendritic cells loaded with S. epidermidis, demonstrating that Tc17 cells are commensal specific (Fig. 4a, b). Commensal-specific IL-17A+ cells were also found in the CD4+ T-cell compartment in both the skin and regional lymph nodes following S. epidermidis or S. xylosus application (Extended Data Fig. 5c–e). Our present results support the idea that, as in the gut22–24, the majority of IL-17A-producingT cells in the skin may be commensal specific.

To assess the consequence of adaptive immune responses to commensals for skin immunity we employed a model of epicutaneous infection with the fungal pathogen Candida albicans. Prior association with S. epidermidis significantly improved innate protection against C. albicans, an effect that was abolished by depletion of CD8+ T cells or neutralization of IL-17A (Fig. 4c, d). Microarray analysis of gene expression following S. epidermidis association revealed a significant upregulation of the alarmins S100A8 and S100A9 (data not shown), known to elicit microbicidal effects and as potent chemoattractants for neutrophils25. Upregulation of these molecules was still detectable at an application dose as low as 1.3 × 106 c.f.u. per cm2, and 2 weeks past the peak of CD8+ T-cell response in the skin (Extended Data Fig. 5f and data not shown). In keratinocytes, induction of these molecules can be mediated by IL-17A26. Analysis of gene expression by interfollicular keratinocytes27 from S. epidermidis-associated mice revealed a CD8+ T-cell- and IL-17A-dependent upregulation of S100A8 and S100A9 expression (Fig. 4e, f). Thus, S. epidermidis induces CD8+ T-cell responses able to promote skin innate responses in such a way that promotes heterologous protection against invasive microbes (Fig. 4g).

The skin immune system has evolved in the context of its constitutive exposure to a diverse microbiota that can be remodelled over time or in response to environmental challenges5–7,28. Here we show that the skin is a highly dynamic immune environment that can be finely calibrated by defined commensals. In light of our present findings, it is intriguing to speculate that microbial diversity may also be required as a means to trigger and educate distinct aspects of the immune system. For instance, the capacity of defined commensals to promote CD8+ T-cell responses that can home to the epidermis may have evolved as a means to specifically reinforce the barrier function of this compartment. Here, we uncovered that tissue-resident dendritic cells are primary sensors of fluctuations in the commensal community and that these cells act in a highly coordinated manner to orchestrate the formation of commensal-specific T-cell responses. The result of this evolving interaction may represent a powerful protective mechanism of host defence by providing heterologous immunity against invasive microbes. In the context of highly perturbed communities, the cumulative cost of these responses may have severe consequences on tissue homeostasis. Indeed, commensal-specific responses are characterized by the production of IL-17A, a cytokine known to contribute to the aetiology and pathology of various skin inflammatory disorders, including psoriasis29. Our work also presents a possible explanation for how variation in microbial communities at different skin sites5,6 may contribute to the site-specificity of dermatological disorders.

METHODS

Mice

C57BL/6 and BALB/c specific pathogen free (SPF) mice were purchased from Taconic Farms. Germ-free C57BL/6 mice were bred at Taconic Farms and maintained in the NIAID gnotobiotic facility. B6.SJL, C57BL/6-[KO]IL1r1 (Il1r1−/−) and C57BL/6J-[KO]B2m-[KO]Abb (Abb−/−B2m−/−) mice were obtained through the NIAID-Taconic exchange program. C57BL/6-Tg(Csf1r-EGFP-NGFR/FKBP1A/TNFRSF6)2Bck/J (CSF1R GFP reporter)30, B6.129P2(C)-Ccr7tm1Rfor/J (Ccr7−/−), B6.129P2(C)-Batf3tm1Kmm/J (Batf3−/−) mice and their C57BL/6 wild-type controls were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. B6(Cg)-Irf8tm1.2Hm/J (Irf8−/−), B6.FVB-Tg(CD207-Dta)312Dhka/J (Lan-DTA), B6.129S2-Cd207tm3(DTR/GFP)Mal/J (Lan-GFP) mice were obtained from H. C. Morse (National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, NIH), D. Kaplan (University of Minnesota) and B. Malissen (Centre d’immunologie de Marseille Luminy, France), respectively. CongenicB2m−/− (B6.129-B2mtm1Jae N12 × B6-LY5.2/Cr) mice were provided by R. Bosselut (National Cancer Institute, NIH). Irf4fl/fl × Cd11cre+ mice were obtained by breeding B6.129S1-Irf4tm1Rdf/J (Irf4fl/fl) mice with B6.Cg-Tg(Itgax–Cre)1-1Reiz/J (Itgax–Cre) mice (both strains from The Jackson Laboratory). All mice were bred and maintained under pathogen-free conditions at an American Association for the Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AAALAC)-accredited animal facility at the NIAID and housed in accordance with the procedures outlined in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. All experiments were performed at the NIAID under an animal study proposal approved by the NIAID Animal Care and Use Committee. Gender- and age-matched mice between 6 and 12 weeks of age were used for each experiment. When possible, preliminary experiments were performed to determine requirements for sample size, taking into account resources available and ethical, reductionist animal use. In general, each mouse of the different experimental groups is reported. Exclusion criteria such as inadequate staining or low cell yield due to technical problems were pre-determined. Animals were assigned randomly to experimental groups.

Human and non-human primate skin tissue

Healthy human skin samples from anonymous patients were obtained as discarded material after cosmetic surgery according to a protocol approved by the Institutional Review Board of NIAID, NIH. All subjects gave informed consent. Non-human primate skin tissue was obtained from the glabella of eight healthy rhesus (Macaca mulatta) or pigtail (Macaca nemestrina) macaques immediately post euthanasia. All monkeys were housed and cared in accordance with AAALAC standards in AAALAC-accredited facilities, and all animal procedures performed according to protocols approved by the NIAID Animal Care and Use Committee.

Topical association and intradermal infection

S. epidermidis strain 42E0331 and R. nasimurium were isolated from mouse colonies. S. epidermidis strain NIHLM08732, S. epidermidis strain 42E03, S. lentus, S. xylosus (isolated from mice as previously described33), S. aureus strain NCTC8325, C. pseudodiphtheriticum strain NIHLM0865 and R. nasimurium were cultured for 18 h in tryptic soy broth at 37 °C. P. acnes ATCC 11827 was cultured for up to 72 h in tryptic soy broth in an anaerobic chamber. Bacteria were enumerated before topical application by assessing colony-forming units using traditional bacteriology techniques and by measuring optical density (OD) at 600 nm using a spectrophotometer.

For topical association of bacteria, each mouse was associated with bacteria by applying bacterial suspension (approximately 109 ml−1, 5 ml or for Extended Data Figs 1c, d, 2d and 5f, 108 or 107 c.f.u. per ml as indicated) across the entire skin surface (approximately 36 cm2) using a sterile cotton swab. Application of bacterial suspension was repeated every other day a total of four times. In experiments involving topical application of various bacterial species or strains, 18-h cultures were normalized using OD600 to achieve similar bacterial density (approximately 109 c.f.u. per ml). In some experiments, mice were infected intradermally in the ear pinnae with 107 c.f.u. of S. epidermidis strain LM087. Mice were euthanized at different time points after the first topical association or intradermal inoculation with bacteria.

Tissue processing

Murine tissues

Cells from the lung, the small intestine lamina propria, the skin draining lymph nodes, the ear pinnae or flank tissue were isolated as previously described2,34. Isolation of cells from epidermal and dermal compartments of the ear skin tissue were performed as previously reported35.

Human and non-human primate skin

Subcutaneous fat tissue was scrapped off with a number 10 scalpel. Skin tissue was then weighted and perfused with 100–500 µl of digestion media (RPMI 1640 media supplemented with 2 mM l-glutamine, 1 mM sodium pyruvate and nonessential amino acids, 20 mM HEPES, 100 U ml−1 penicillin, 100 µg ml−1 streptomycin and 0.25 mg ml−1 Liberase Cl purified enzyme blend (Roche)). Perfused skin tissue was placed in 5ml of digestion media dermal side down and incubated for 1 h at 4 °C. Tissue was then minced with scissors in 5ml of fresh digestion media and incubated at 37 °C with shaking. After 1 h, digestion was stopped by adding 100 µl of 0.5 MEDTA and 1 ml of fetal bovine serum. Digested tissue was then smashed on a 70 µm cell strainer to obtain a single-cell suspension.

Immunofluorescence/confocal microscopy

Ear pinnae were split, fixed in 1% paraformaldehyde solution (Electron Microscopy Sciences) overnight at 4 °C and blocked in 1% BSA 0.25% Triton X blocking buffer for 2 h at room temperature. Tissues were first stained with anti-CD8α (clone 53-6.7, eBioscience), anti-CD11c (clone N418, eBioscience) and/or rabbit anti-GFP (Life Technologies) antibodies overnight at 4 °C, washed three time with PBS and then stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, Sigma-Aldrich) for 5 min at room temperature and before being mounted with ProLong Gold (Life Technologies) anti-fade reagent. Images were captured on a Leica TCS SP8 confocal microscope with a 40× oil objective (HC PL APO 40×/1.3 oil). Images were analysed using Imaris Bitplane software.

In vivo antibody administration

Mice were treated intraperitoneally (i.p.) with anti-CSF1R antibody (clone AFS98, BioXCell) or Rat IgG2a isotype control antibody (clone 2A3, BioXCell). Treatment schedule was as follows: 2mg of either antibody was injected i.p. in each mouse 5 and 3 days before the first S. epidermidis topical application (days −5 and −3); each mouse then received 0.5 mg of either antibodies on days −2, −1 and days 0, 2, 4, 6, 9, 11 and 13 post topical application18. Mice were analysed two weeks after the first S. epidermidis topical application (or 19 days after the first antibody injection).

For CD8+ T-cell depletion, mice were treated i.p. with 0.5 mg of anti-CD8 antibody (clone 2.43) or rat IgG2b isotype control antibody (clone LTF-2, BioXCell) every 2–3 days starting at day 6 after the first topical application of S. epidermidis. For IL-17A neutralization, mice were treated i.p. with 0.5 mg of anti-IL-17A antibody (clone 17F3, BioXCell) ormouse IgG1 isotype control antibody (clone MOPC-21, BioXCell) every 2 days starting at day 6 after the first topical application of S. epidermidis.

In vitro re-stimulation

For detection of basal cytokine potential, single-cell suspensions from various tissues were cultured directly ex vivo in a 96-well U-bottom plate in complete medium (RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10%fetal bovine serum (FBS), 2 mM l-glutamine, 1 mM sodium pyruvate and nonessential amino acids, 20 mM HEPES, 100 U ml−1 penicillin, 100 µg ml−1 streptomycin, 50 mM β-mercaptoethanol) and stimulated with 50 ng ml−1 phorbol myristate acetate (PMA) (Sigma-Aldrich) and 5 µg ml−1 (mouse) or 1 µg ml−1 (human and monkey) ionomycin (Sigma-Aldrich) in the presence of brefeldin A (GolgiPlug, BD Biosciences) for 2.5 h at 37 °C in 5%CO2. After stimulation, cells were assessed for intracellular cytokine production as described below.

Phenotypic analysis

Murine single-cell suspensions were incubated with fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies against surface markers CD3 (145-2C11), CD4 (clone RM4–5), CD8α (53-6.7), CD8β (eBioH35-17.2), CD11b (M1/70), CD11c (N418 or HL3), CD19 (6D5), CD45.2 (104), CD45R (RA3-6B2), CD49b (DX5), CD69 (H1.2F3), CD103 (2E7), DEC205 (NLDC-145), KLRG1 (2F1), MHCII (M5/114.15.2) and/ or TCRβ (H57-597) in Hank’s buffered salt solution (HBSS) for 20 min at 4 °C and then washed. LIVE/DEAD Fixable Blue Dead Cell Stain Kit (Invitrogen Life Technologies) was used to exclude dead cells. Cells were then fixed for 15 min at 4 °C using 2% paraformaldehyde solution (Electron Microscopy Sciences) and washed twice. For simultaneous Foxp3 and intracellular cytokine staining, cells were stained with fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies against Foxp3 (FJK-16 s), IFN-γ (XMG-1.2) and IL-17A (eBio17B7) in HBSS containing 0.5%saponin (Sigma-Aldrich) for 45 min at 4 °C. For detection of Langerin, cells were incubated with a fluorochrome-conjugated antibody against CD207 (929F3.01) in permeabilization buffer supplied with the BD Cytofix/Cytoperm kit (BD Biosciences) for 1 h at 4 °C. Each staining was performed in the presence of purified anti-mouse CD16/32 (93), 0.2 mg ml−1 purified rat IgG and 1 mg ml−1 of normalmouse serum (Jackson Immunoresearch). Staining of cells from human or non-human primate skin tissue was performed using a similar protocol and the following antibodies against human proteins: anti-CD3 (SP34-2), anti-CD4 (L200), anti-CD8α (RPA-T8), anti-IFN-γ (4S.B3) and anti-IL-17A (eBio64DEC17). All antibodies were purchased from eBioscience, BD Biosciences, Miltenyi Biotec or Dendritics. Cell acquisition was performed on an LSRII flow cytometer using FACSDiVa software (BD Biosciences) and data were analysed using FlowJo software (TreeStar).

Analysis of skin microbiota after topical association

DNA extraction from skin and 454 pyrosequencing

Mouse ear skin samples were sterilely obtained and processed using a protocol adapted from ref. 31. For 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing, the DNA from each sample was amplified using Accuprime High Fidelity Taq polymerase (Invitrogen Life Technologies) with universal primers flanking variable regions V1 (primer 27 F; 5′-AGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG-3′) and V3 (primer 534 R; 5′-ATTACCGCGGCTGCTGG-3′). For each sample, the universal primers were tagged with unique sequences (‘barcodes’) to allow for multiplexing/demultiplexing36. PCR products were then purified using the Agencourt Ampure XP kit (Beckman Counter Genomics) and quantitated using the QuantIT dsDNA High-Sensitivity Assay kit (Invitrogen Life Technologies). Approximately equivalent amounts of each PCR product were then pooled and purified on a column from the MinElute PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen) into 30 µl TE buffer before sequencing at the NIH Intramural Sequencing Center on a 454 GS FLX (Roche) instrument using titanium chemistry. Sequencing data were analysed as previously described2.

Bacteria quantitation

The ear skin of topically associated or unassociated control mice was swabbed with a sterile cotton swab previously soaked in tryptic soy broth. Swabs were streaked on either tryptic soy agar or blood agar plates. Plates were then placed at 37 °C under aerobic or anaerobic conditions for 18 h. Colony-forming units on each plate were enumerated and the identity of the isolates was confirmed by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time of flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry.

Purification of skin dendritic cell subsets

Dendritic cell subsets were purified from the epidermis and dermis compartment of the ear skin tissue of unassociated mice and S. epidermidis-associated mice at days 5 and 12 post topical application. In brief, cell suspensions obtained from the dermis compartment were incubated with a mixture of antibodies containing anti-CD16/32 (93), anti-CD11b (M1/70), anti-CD11c (N418), anti-CD45.2 (104), anti-CD103 (2E7), anti-MHCII (M5/114.15.2) in the presence of DAPI (Sigma-Aldrich). Cells from the epidermis compartment were incubated with anti-CD16/32, anti-CD45.2, anti-MHCII and DAPI. The following two subsets of dendritic cells were sorted from the dermis by flow cytometry on a FACSAria (BD Biosciences): CD45.2+ CD11c+ MHCII+ CD11b− CD103+ cells (CD103+ dendritic cells) and CD45.2+ CD11c+ MHCII+ CD11b+ CD103− cells (CD11b+ dendritic cells). Langerhans cells were sorted from the epidermis as CD45.2+ MHCII+ cells.

Gene expression analysis by NanoString

The nCounter analysis system (Nano-String Technologies) was used to screen for the expression of signature genes associated with inflammation pathway in the different dendritic cell subsets37. Two specific probes (capture and reporter) for each gene of interest were employed. In brief, RNA from each dendritic cell subset was obtained by lysing the sorted cells (103 cells per µl) in RLT buffer (Qiagen) and then hybridized with the customized Reporter CodeSet and Capture ProbeSet of the Mouse Inflammation Panel including 150 selected genes (NanoString Technologies), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Messenger RNA molecules were counted on a NanoString nCounter, as previously described2. Data analysis was performed according to NanoString Technologies recommendations. mRNA counts were processed to account for hybridization efficiency, background noise and sample content using the R package NanoString Norm with arguments: CodeCount = ‘geo.mean’, Background = ‘mean.2sd’, SampleContent = ‘housekeeping.geo.mean’. Each sample profile was normalized to geometric mean of two housekeeping genes, Cltc and Pgk1. Post normalization, genes with mean counts less than 20 were disregarded and differential expression of remaining genes was determined using a nonparametric Welch t-test with correction for multiple testing using the Benjamini–Hochberg false discovery rate (FDR) controlling procedure in the multtest package in R. Based on genes with a FDR < 0.05, a heat map was rendered using the R package gplots.

Dendritic cell and T-cell co-culture assay

CD45+ CD90.2+ CD8β+ or CD45+ CD90.2+ CD4+ effector T cells (>95%purity) were sorted by flow cytometry from the ear skin tissue of C57BL/6 mice 2 weeks after topical association with S. epidermidis strain LM087 or S. xylosus using a FACSAria cell sorter. For CD8β+ and CD4+ T-cell purification from the skin draining lymph nodes, single-cell suspension from the ear skin tissue of mice topically associated with S. epidermidis strain LM087 or S. xylosus were first magnetically enriched for CCR6+ cells by positive selection using PE-conjugated CCR6 antibody (clone 29-2L17), anti-PE MicroBeads and MACS separation columns (Miltenyi Biotec). The enriched fraction was further labelled with fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies against CD45, CD90.2, CD4 and/or CD8β and CD45+ CD90.2+ CD8β+ or CD45+ CD90.2+ CD4+ were sorted (>95% purity) by flow cytometry on a FACSAria cell sorter. For splenic dendritic cell (SpDC) purification, single-cell suspensions from the spleen of congenic wild-type, B2m−/− or Abb−/− B2m−/− mice were magnetically enriched for CD11c+ cells by positive selection using CD11c MicroBeads and MACS separation columns (Miltenyi Biotec). Purified SpDCs and CD8β+ or CD4+ T cells were co-cultured at a 15:1 ratio (5 × 103 CD8β+ T cells) in a 96-well U-bottom plate in complete medium for 16 h at 37 °C in 5% CO2. Brefeldin A (GolgiPlug) was added for the final 4 h of culture. SpDC were previously incubated for 3 h with or without heat-killed S. epidermis, heat-killed S. xylosus or heat-killed S. aureus (bacteria:SpDC ratio, 500:1) and washed before co-culture with CD8β+ T cells. In some experiments, co-cultures of CD8β+ T cells and naive SpDC were supplemented with 5 µg ml−1 ultra-pure lipopoly-saccharide (LPS, InvivoGen), 100nM N-α-palmitoyl-S-[2,3-bis(palmitoyloxy-(2RS)-propyl]-l-cysteine (Pam3Cys, InvivoGen) and/or 10 ng ml−1 murine IL-1α (Peprotech). CD8β+ T cell cytokine production following co-culture was assessed by flow cytometry after intracellular cytokine staining using the following antibodies: anti-CD4, anti-CD8β, anti-CD45.1 (clone A20), anti-CD45.2, anti-TCRβ, anti-IFN-γ and anti-IL-17A.

Cytokine measurement

Leukocytes isolated from the skin of S. epidermidis associated mice were cultured in 100 µl of complete medium for 3 h at 37 °C in 5% CO2. FACS-purified CD8β+ T cells from the skin of S. epidermidis-associated mice were cultured overnight at 37 °C in 5% CO2 in 30 µl of complete culture medium in a 96-well U-bottom plate coated with anti-CD3ε (1 µg ml−1, clone 145-2C11, BD Biosciences) in the presence or absence of IL-1α and IL-1β (10 ng ml−1 each, Peprotech). Supernatants were collected and levels of inflammatory cytokines were assessed using a bead-based cytokine detection assay (FlowCytomix, eBioscience). Cytokine concentrations were adjusted to the plated density of 2 × 104 cells in 100 or 30 µl culture volume.

Purification of keratinocytes

Interfollicular keratinocytes were purified by cell sorting from the ear skin tissue of unassociated mice and S. epidermidis-associated mice at 14 days post topical application. In brief, cell suspensions obtained from ear skin tissue were incubated with the following antibodies: anti-CD16/32 (93), anti-CD45 (30-F11), anti-CD49f (eBioGoH3), anti-CD117 (2B8), anti-CD140a (APA5) and anti-Sca-1 (D7) in the presence of DAPI. Interfollicular keratinocytes were sorted by flow cytometry on a FACSAria (BD Biosciences) as CD45− CD117− CD140a− CD49f+ Sca-1+ cells.

Candida albicans infection

Eleven days after the first topical application of S. epidermidis, mice were infected with C. albicans along the dorsal midline as previously described38. In brief, C. albicans was grown in YPAD medium at 30 °C for 18 h and re-suspended at 107 C. albicans yeast per 1 ml of sterile PBS. One hundred microlitres of this suspension was applied to sandpaper (100 grit)-treated dorsal skin to achieve an infectious dose of 106 C. albicans. At 2 days post infection a 6 mm punch biopsy of skin was homogenized in sterile PBS containing penicillin and streptomycin before plating on YPAD plates. Colony-forming units were counted after culture at 30 °C for 48 h.

RNA purification and quantitative PCR

Total RNA was isolated from purified keratinocytes or skin tissue biopsies using the RNeasy Mini Kit (QIAGEN). Complementary DNA was prepared using the Omniscript Reverse Transcription Kit (QIAGEN) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Quantitative real-time PCR was performed on a Bio-Rad iCycler using the iQ SYBR Green Supermix (BioRad) and predesigned Quantitect primers (QIAGEN) specific for the following genes: Hprt, S100a8 and S100a9.

Histology

Mice were euthanized 7 days after topical application or intraperitoneal injection of S. epidermidis LM087 in the ear. Unassociated mice were used as controls. The ears from each mouse were removed and fixed in PBS containing 10% formalin. Paraffin-embedded sections were cut at 0.5 mm, stained with haematoxylin and eosin and examined histologically.

Statistics

Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean or mean ± standard deviation. Group sizes were determined based on the results of preliminary experiments. No statistical method was used to predetermine sample size. Mice were assigned at random to groups. Mouse studies were not performed in a blinded fashion. Generally, each mouse of the different experimental groups is reported. Statistical significance was determined with the two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test, under the untested assumption of normality. Within each group there was an estimate of variation, and the variance between groups was similar. All statistical analysis was calculated using Prism software (GraphPad). Differences were considered to be statistically significant when P < 0.05.

Extended Data

Extended Data Figure 1. Assessment of Foxp3+ regulatory T cells and cytokine production by effector T cells after S. epidermidis topical application and/or intradermal inoculation.

a, Frequencies and absolute numbers of skin regulatory (CD45+ TCRβ+ CD4+ Foxp3+) T cells in unassociated mice (Ctrl, n = 4) and mice associated with S. epidermidis (n = 4) at day 14 post first topical application. b, Absolute numbers of effector T cells producing IL-17A after PMA/ionomycin stimulation in the skin (ear pinnae and flank), the lung or the small intestine lamina propria (gut) at day 14 post topical association (Ctrl, n = 4–5; S. epi., n = 4–5). c, d, Enumeration of colony-forming units and absolute numbers of effector T cells producing IFN-γ or IL-17A (PMA/ionomycin) from the skin 2 weeks post application with different doses (107, 108 or 109 c.f.u. per ml) of S. epidermidis (n = 4 per group). e, Frequencies and absolute numbers of neutrophils and monocytes in the skin of mice 14 days after the first topical application or intradermal inoculation with S. epidermidis (n = 4 per group). f, Assessment of cytokine production (mean ± s.e.m., n = 3 per time point) by leukocytes from the ear skin tissue 24 and 48 h after topical association with S. epidermidis. Unassociated mice were used as controls. No significant amounts of IL-4, IL-5, IL-17A, IL-18, IL-21 or IL-22 could be detected at the time of analysis. g, IFN-γ and IL-17A production by skin effector T cells in mice 7 days after S. epidermidis topical application or intradermal inoculation. h, Frequencies of IFN-γ and IL-17A-producing effector T cells in the skin of mice 7 and 14 days after the first topical application or intradermal inoculation of S. epidermidis (n = 4–5 mice per group). All results shown are representative of 2–3 experiments with similar results. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; NS, not statistically significant as calculated by Student’s t-test.

Extended Data Figure 2. Assessment of CD8+ T-cell responses in the skin of specific pathogen-free and germ-free mice after topical application with skin commensals.

a, Mice were left unassociated (Ctrl, n = 5) or topically associated with S. epidermidis human isolate (n = 5), S. xylosus (n = 3), S. epidermidis murine isolate (S.epi 42E03, n = 2), S. lentus (n = 2), R. nasimurium (n = 2), S. aureus (n = 5), C. pseudodiphtheriticum (n = 3) or P. acnes (n = 3). Quantification of colony-forming units from the ears after topical application is shown 2 weeks after first association. b, Frequencies and numbers of effector (CD45+ TCRβ+ CD4+ Foxp3−) T cells producing IFN-γ or IL-17A after PMA/ionomycin stimulation in the skin of mice from a at day 14 post first topical application. Bar graphs represent the mean value from two mice. c, Frequencies of skin CD4+ and CD8β+ effector T cells in mice from a at day 14 post first topical application. d, Absolute numbers of IFN-γ- and IL-17A-producing CD8β+ effector T cells in the skin of unassociated (Ctrl) mice or mice associated with different doses (107, 108 or 109 c.f.u. per ml) of S. epidermidis (n = 4 per group). e, Absolute numbers of skin CD8β+ effector T cells in unassociated (Ctrl, n = 3) mice or mice associated with 1 ml (n = 5) or 5ml (n = 5) of a suspension (109 c.f.u. per ml) of S. epidermidis. f, Flow cytometric assessment of the frequencies of CD4+ and CD8β+ effector T cells and absolute numbers of CD8β+ effector T cells in SPF (n = 3 per group) and germ-free (GF, n = 4 per group) mice 2 weeks after S. epidermidis topical application. g, Absolute numbers of IFN-γ- and IL-17A-producing CD8β+ effector T cells in the skin of unassociated (Ctrl) or S. epidermidis- associated C57BL/6 and BALB/c mice at 14 days post first topical application (n = 5 per group). For d–g, all results shown are representative of 2–3 independent experiments with similar results. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; NS, not statistically significant as calculated with Student’s t-test. h, Quantification of colony-forming units from the ears of adult mice born from S. epidermidis associated (S. epi+, n = 3) or unassociated (Ctrl, n = 3) breeder pairs. Flow plots and bar graphs (mean ± s.e.m.) illustrate the frequencies of CD4+ and CD8β+ effector T cells and absolute numbers of CD8β+ effector T cells, respectively. n.d., not detected; **P < 0.01 as calculated with Student’s t-test.

Extended Data Figure 3. CD8+ T cells accumulate preferentially in the epidermidis after topical application of S. epidermidis.

a, Proportion of effector (CD45+ TCRβ+ Foxp3−) CD8β+ T cells in the epidermal and dermal compartments of the ear skin tissue 2 weeks after the first S. epidermidis topical application. b, Representative imaging volume projected along the x axis of ears from Langerin–GFP reporter mice at 14 days post first topical application with S. epidermidis. Scale bars, 30 µm. c, Numbers of CD3+ CD8β+ cells producing IFN-γ or IL-17A (after PMA/ionomycin stimulation) from normal nonhuman primate (NHP) skin (n = 8). d, Assessment of IL-17A production in the supernatant of CD8β+ T cells purified from the skin of mice topically associated with S. epidermidis and cultured overnight in presence of anti-CD3ε alone (Ctrl) or with IL-1α and IL-1β (+ IL-1). Bars represent the mean value ± s.e.m. (n = 3, **P < 0.01 as calculated with Student’s t-test). Results shown in a, c and d are representative of 2–3 experiments with similar results.

Extended Data Figure 4. Depletion strategies for the different subsets of skin dendritic cells.

a, Gating strategy for various dendritic cell subsets in the skin. Cells are first gated on live CD45+ CD11c+ MHCII+. Subsets of dendritic cells are then defined as follows: Langerhans cells (LC) are gated on CD11b+ CD207(Langerin)+ cells, CD103+ dendritic cells (CD103 DC) on CD11b− CD207+ cells and CD11b+ dermal dendritic cells (CD11b DC) on CD11b+ CD207− cells. b, Comparative assessment by flow cytometry of Langerhans cell, CD103 DC and CD11b DC in the ear skin of unassociated mice (control) and mice first topically associated with S. epidermidis 2weeks earlier. c, Absolute numbers of Langerhans cell, CD103 DC and CD11b DC 2weeks after the first topical application of S. epidermidis in wild-type (WT, n = 3), Langerin–DTA (Lan–DTA, n = 3), Batf3−/− (n = 3) or Irf8−/− (n = 3) mice and in mice treated with anti-CSF1R (n = 3) or isotype control (rat IgG, n = 3) antibodies. d, Absolute numbers of CD11chi MHCII+ CD8+ DEC205+ dendritic cells in the spleen and the skin draining lymph node (dLN) of wild-type (n = 5) and Batf3−/− (n = 6) mice. e, Phenotypic analysis of CD45+ MHCII+ CD11c+ cells by flow cytometry and absolute numbers of effector (CD45+ TCRβ+ Foxp3−) CD8β+ T cells and IL-17A- or IFN-γ-producing CD8β+ T cells in wild-type (n = 3) and Irf8−/− (n = 3) mice 2 weeks after the first topical application of S. epidermidis. f, Assessment of IL-1 production by leukocytes from the ear skin tissue of S. epidermidis-associated mice treated with anti-CSF1R (n = 4) or isotype control (rat IgG, n = 5) antibodies. g, Frequencies of total and IFN-γ- or IL-17A-producing CD8β+ effector T cells in S. epidermidis-associated Irf4fl/fl×CD11ccre+ (n = 3) and littermate control (n = 3) mice. All data shown in this figure are representative of 2–3 experiments with similar results. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; NS, not statistically significant as calculated with Student’s t- test.

Extended Data Figure 5.

Commensal-driven CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell responses in the skin tissue and the skin draining lymph nodes are specific for commensal antigens. a, Frequencies of IFN-γ- or IL-17A-producing CD8β+ T cells in overnight co-cultures of splenic dendritic cells (SpDC) and CD8β+ T cells purified from the skin draining lymph node (dLN) of mice first topically associated with S. epidermidis 2 weeks earlier. b, Frequencies of IFN-γ- and IL-17A-producing CD8β+ T cells in overnight co-cultures of SpDC and CD8β+ T cells purified from the skin of mice 14 days after the first S. epidermidis application. Dendritic cells were purified from either wild-type (WT) or Abb−/− B2m−/− mice. c, d, Frequencies of IFN-γ- and IL-17A producing CD4+ T cells in overnight co-cultures of SpDC and CD8β+ T cells purified from the skin ear tissue or the skin dLN of mice 14 days after the first S. epidermidis application. For a, b and d, Ctrl, naive SpDC; S. epi, SpDC + heat-killed S. epidermidis; Abb/B2m S. epi, Abb−/− B2m−/− SpDC + heat-killed S. epidermidis. e, Frequencies of IFN-γ- and IL-17A producing CD4+ T cells in overnight co-cultures of SpDC and CD8β+ T cells purified from the skin ear tissue or the skin dLN of mice 14 days after the first S. xylosus application. Ctrl, naive SpDC; S. xylo, SpDC + heat-killed S. xylosus; Abb/B2m S. xylo, Abb−/− B2m−/− SpDC + heat-killed S. xylosus. All data shown in a–d are representative of three independent experiments. Graph bars represent the mean ± standard deviation of triplicate cultures. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.0001, ****P < 0.0001 as calculated with Student’s t-test. f, S100a8 and S100a9 gene expression in dorsal skin biopsies of mice associated with different doses (107, 108 or 109 c.f.u. per ml) of S. epidermidis 2weeks after the first topical application (n = 4 per group). Data are expressed as fold increase over gene expression in unassociated control mice.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Division of Intramural Research of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) and by the Human Frontier Science Program (C.W.). We thank the NIAID animal facility staff, in particular A. Gozalo (isolation of S. xylosus); D. Trageser-Cesler and C. Acevedo (NIAID gnotobiotic facility); K. Holmes, C. Eigsti and E. Stregevsky (NIAID sorting facility); K. Frank and F. Stock (MALDI-TOF analysis); B.Malissen (Langerin–GFP reportermice); H. C. Morse (Irf8−/− mice); D. Kaplan (Langerin-DTA mice); R. Bosselut (B2m−/− mice); S. B. Hopping (collection of human skin tissue samples); J. Oh, K. Loré, and the Brenchley laboratory (technical advice and reagents); and K. Beacht and L. Martins dos Santos for technical assistance. We also thank the Belkaid laboratory for critical reading of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Online Content Methods, along with any additional Extended Data display items and Source Data, are available in the online version of the paper; references unique to these sections appear only in the online paper.

Author Contributions S.N., N.B., and Y.B. designed the studies. S.N. and N.B. performed the experiments and analysed the data. J.L.L. assisted with in vitro co-culture studies and S.-J.H. with innate cell analysis and imaging. O.J.H. and C.W. provided technical assistance. S.C. and C.D. provided technical advice and performed 454 pyrosequencing. S.C. and M.Q. analysed 454 pyrosequencing data. S.H. assisted in processing of human and non-human primate skin tissue samples. A.L.B. performed NanoString data analysis. J.M.B. and H.H.K. provided technical advice and skin tissue samples from non-human primates and human patients, respectively. R.T., K.M.M. and M.M. assisted with design of dendritic cell depletion strategies. J.A.S. helped to design sequencing studies and provided guidance on bacterial isolates. S.N., N.B. and Y.B. wrote the manuscript.

454 sequencing data are deposited in the Sequence Read Archive under accession number SRP039428.

The authors declare no competing financial interests

References

- 1.Grice EA, Segre JA. The skin microbiome. Nature Rev. Microbiol. 2011;9:244–253. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Naik S, et al. Compartmentalized control of skin immunity by resident commensals. Science. 2012;337:1115–1119. doi: 10.1126/science.1225152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chehoud C, et al. Complement modulates the cutaneous microbiome and inflammatory milieu. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:15061–15066. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1307855110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sanford JA, Gallo RL. Functions of the skin microbiota in health and disease. Semin. Immunol. 2013;25:370–377. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2013.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grice EA, et al. Topographical and temporal diversity of the human skin microbiome. Science. 2009;324:1190–1192. doi: 10.1126/science.1171700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Costello EK, et al. Bacterial community variation in human body habitats across space and time. Science. 2009;326:1694–1697. doi: 10.1126/science.1177486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kong HH, et al. Temporal shifts in the skin microbiome associated with disease flares and treatment in children with atopic dermatitis. Genome Res. 2012;22:850–859. doi: 10.1101/gr.131029.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Belkaid Y, et al. CD8+ T cells are required for primary immunity in C57BL/6 mice following low-dose, intradermal challenge with Leishmania major. J. Immunol. 2002;168:3992–4000. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.8.3992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mueller SN, Gebhardt T, Carbone FR, Heath WR. Memory T cell subsets, migration patterns, and tissue residence. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2013;31:137–161. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032712-095954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murphy KM. Transcriptional control of dendritic cell development. Adv. Immunol. 2013;120:239–267. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-417028-5.00009-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mittal A, et al. Non-invasive delivery of nanoparticles to hair follicles: a perspective for transcutaneous immunization. Vaccine. 2013;31:3442–3451. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.12.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Caux C, et al. Regulation of dendritic cell recruitment by chemokines. Transplantation. 2002;73:S7–S11. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200201151-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tamoutounour S, et al. Origins and functional specialization of macrophages and of conventional andmonocyte-derived dendritic cells inmouse skin. Immunity. 2013;39:925–938. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Igyártó BZ, et al. Skin-residentmurine dendritic cell subsets promote distinct and opposing antigen-specific T helper cell responses. Immunity. 2011;35:260–272. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bedoui S, et al. Cross-presentation of viral and self antigens by skin-derived CD103+ dendritic cells. Nature Immunol. 2009;10:488–495. doi: 10.1038/ni.1724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hildner K, et al. Batf3 deficiency reveals a critical role for CD8α1 dendritic cells in cytotoxic T cell immunity. Science. 2008;322:1097–1100. doi: 10.1126/science.1164206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Merad M, Sathe P, Helft J, Miller J, Mortha A. The dendritic cell lineage: ontogeny and function of dendritic cells and their subsets in the steady state and the inflamed setting. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2013;31:563–604. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-020711-074950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hashimoto D, et al. Pretransplant CSF-1 therapy expands recipient macrophages and ameliorates GVHD after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. J. Exp. Med. 2011;208:1069–1082. doi: 10.1084/jem.20101709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vander Lugt B, et al. Transcriptional programming of dendritic cells for enhanced MHC class II antigen presentation. Nature Immunol. 2014;15:161–167. doi: 10.1038/ni.2795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clark RA, et al. The vast majority of CLA+ T cells are resident in normal skin. J. Immunol. 2006;176:4431–4439. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.7.4431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lehmann-Grube F, Dralle H, Utermohlen O, Lohler J. MHC class I molecule-restricted presentation of viral antigen in beta 2-microglobulin-deficient mice. J. Immunol. 1994;153:595–603. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang Y, et al. Focused specificity of intestinal TH17 cells towards commensal bacterial antigens. Nature. 2014;510:152–156. doi: 10.1038/nature13279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goto Y, et al. Segmented filamentous bacteria antigens presented by intestinal dendritic cells drive mucosal Th17 cell differentiation. Immunity. 2014;40:594–607. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lécuyer E, et al. Segmented filamentous bacterium uses secondary and tertiary lymphoid tissues to induce gut IgA and specific T helper 17 cell responses. Immunity. 2014;40:608–620. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gebhardt C, Nemeth J, Angel P, Hess J. S100A8 and S100A9 in inflammation and cancer. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2006;72:1622–1631. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2006.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mose M, Kang Z, Raaby L, Iversen L, Johansen C. TNFα- and IL-17A-mediated S100A8 expression is regulated by p38 MAPK. Exp. Dermatol. 2013;22:476–481. doi: 10.1111/exd.12187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nowak JA, Fuchs E. Isolation and culture of epithelial stemcells. Methods Mol. Biol. 2009;482:215–232. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-060-7_14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oh J, Conlan S, Polley EC, Segre JA, Kong HH. Shifts in human skin and nares microbiota of healthy children and adults. Genome med. 2012;4:77. doi: 10.1186/gm378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martin DA, et al. The emerging role of IL-17 in the pathogenesis of psoriasis: preclinical and clinical findings. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2013;133:17–26. doi: 10.1038/jid.2012.194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References

- 30.Burnett SH, et al. Conditional macrophage ablation in transgenic mice expressing a Fas-based suicide gene. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2004;75:612–623. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0903442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grice EA, et al. Longitudinal shift in diabetic wound microbiota correlates with prolonged skin defense response. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:14799–14804. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1004204107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Conlan S, et al. Staphylococcus epidermidis pan-genome sequence analysis reveals diversity of skin commensal and hospital infection-associated isolates. Genome Biol. 2012;13:R64. doi: 10.1186/gb-2012-13-7-r64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gozalo AS, et al. Spontaneous Staphylococcus xylosus infection in mice deficient in NADPH oxidase and comparison with other laboratory mouse strains. J. Am. Assoc. Lab. Anim. Sci. 2010;49:480–486. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Spencer SP, et al. Adaptation of innate lymphoid cells to a micronutrient deficiency promotes type 2 barrier immunity. Science. 2014;343:432–437. doi: 10.1126/science.1247606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Helft J, Merad M. Isolation of cutaneous dendritic cells. Methods Mol. Biol. 2010;595:231–233. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-421-0_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lennon NJ, et al. A scalable, fully automated process for construction of sequence-ready barcoded libraries for 454. Genome Biol. 2010;11:R15. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-2-r15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Geiss GK, et al. Direct multiplexed measurement of gene expression with color-coded probe pairs. Nature Biotechnol. 2008;26:317–325. doi: 10.1038/nbt1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rittig MG, et al. Coiling phagocytosis of trypanosomatids and fungal cells. Infect. Immun. 1998;66:4331–4339. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.9.4331-4339.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]