Abstract

Objectives

To identify subtypes of adolescent gamblers based on the 10 Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition criteria for pathological gambling and the 9 Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition criteria for gambling disorder and to examine associations between identified subtypes with gambling, other risk behaviors, and health/functioning characteristics.

Methods

Using cross-sectional survey data from 10 high schools in Connecticut (N = 3901), we conducted latent class analysis to classify adolescents who reported past-year gambling into gambling groups on the basis of items from the Massachusetts Gambling Screen. Adolescents also completed questions assessing demographic information, substance use (cigarette, marijuana, alcohol, and other drugs), gambling behaviors (relating to gambling formats, locations, motivations, and urges), and health/functioning characteristics (eg, extracurricular activities, mood, aggression, and body mass index).

Results

The optimal solution consisted of 4 classes that we termed low-risk gambling (86.4%), at-risk chasing gambling (7.6%), at-risk negative consequences gambling (3.7%), and problem gambling (PrG) (2.3%). At-risk and PrG classes were associated with greater negative functioning and more gambling behaviors. Different patterns of associations between at-risk and PrG classes were also identified.

Conclusions

Adolescent gambling classifies into 4 classes, which are differentially associated with demographic, gambling patterns, risk behaviors, and health/functioning characteristics. Early identification and interventions for adolescent gamblers should be sensitive to the heterogeneity of gambling subtypes.

Keywords: adolescents, gambling, latent class analysis

In the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition (DSM-IV) (American Psychiatric Association, 2000), pathological gambling (PG) was classified as an impulse-control disorder determined by endorsement of 5 or more criteria. Recently, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition (DSM-V) (American Psychiatric Association, 2013) renamed PG to gambling disorder (GD), eliminated the inclusionary criterion of “committing illegal acts to finance gambling,” and lowered the diagnostic threshold from 5 to 4 inclusionary criteria.

The lifetime PG rate among adults in North America ranges from 0.4% to 1.9% and the past-year rate from 0.2% to 1.4%, with higher estimates derived from gambling screens (Shaffer and Hall, 2001; Petry et al., 2005). Past-year estimates of problem gambling (PrG), which typically employs a lower threshold than PG, among adults globally range from 0.5% to 7.6%, yielding an average rate of 2.3% (Williams et al., 2012). Both PrG and PG are associated with significant mental health concerns and public health costs (Shaffer and Hall, 2001; Desai and Potenza, 2008).

Youth gambling is of major concern and needs examination. Prevalence estimates of youth PrG and PG are more than double those among adults (Gupta and Derevensky, 1998; Shaffer et al., 1999; Shaffer and Hall, 2001). Lifetime PG among adolescents is 3.4% and PrG is 8.4% (Shaffer and Hall, 2001). In a nationally representative sample of US adolescents (ages 14–21), 68% gambled in the past year and 17% gambled more than once per week (Barnes et al., 2009). Pathological gambling in youth has been associated with multiple negative outcomes, such as poor academic performance, substance use, depression, and aggression (Lynch et al., 2004; Yip et al., 2011a). Even low-risk and at-risk gambling (as compared with nongambling) among youth have been associated with health and functioning impairments (Yip et al., 2011a). Efforts to identify classes of adolescent gamblers may have implications for improving the health of adolescents.

The DSM-IV and the DSM-V (American Psychiatric Association, 2013) use a dichotomous categorization of a gambling diagnosis; however, PG may be better conceptualized as dimensional constructs (Carragher and McWilliams, 2011; Potenza, 2013). Several researchers have sought to distinguish the gambling subtypes to expand the understanding of etiological and clinical significance of PG (see the review by Milosevic and Ledgerwood, 2010). For example, the Pathway model integrates developmental, neurobiological, cognitive, and personality variables to identify 3 subtypes of problem gamblers (Blaszczynski and Nower, 2002; Nower and Blaszczynski, 2004). However, more research that employs data-driven approaches is warranted to best classify gambling behaviors, particularly among youth gamblers who may be qualitatively different from adult gamblers.

Latent class analyses (LCAs) have been used to identify classes of adult gamblers (Xian et al., 2008; Hong et al., 2009; McBride et al., 2010; Carragher and McWilliams, 2011). An LCA of data from the Vietnam Era Twin Registry identified 3 classes (low-risk [88.7%], moderate-risk [9.2%], and high-risk [2.1%] classes) using the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Third Edition Revised PG criteria (Xian et al., 2008). A separate LCA study of gamblers in Britain using the DSM-IV criteria for PG also found 3 comparable classes as follows: “nonproblematic gambler” (88.9%), “preoccupied chaser” (9.7%), and “antisocial impulsivist gambler” (1.4%) (McBride et al., 2010). In the US National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions data, the following 3 classes were identified: classes with no gambling problems (93.3%), moderate gambling problems (6.1%), and pervasive gambling problems (0.6%) (Carragher and McWilliams, 2011). Examination of gambling classes among a sample of older adults using the DSM-IV PG criteria identified the following 2 classes: non-PrG (lifetime: 89.2%, current: 92%) and PrG (lifetime: 10.8%, current: 8.4%) (Hong et al., 2009). Taken together, these studies demonstrate the utility of using LCA to identify classes of gamblers, provide support for qualitative differences among gambling classes, and suggest that PG and PrG should not be conceptualized as a single categorical entity but rather as a dimensional construct.

Studies using LCA to categorize adolescent gamblers are scant. Faregh and Derevensky (2011) used LCA to examine the DSM-IV criteria for PG separately for males and females using adolescent community and treatment samples. The largest 2 classes consisted of “social gamblers” and “probable pathological gamblers” in both samples. However, among higher-severity gambling groups, different numbers of classes (ranging from 2 to 4) emerged depending on the types of sample and sex examined. Recently, an LCA of a sample of adolescents who reported past-year gambling from an inner-city emergency department yielded 2 classes (low- and high-consequence gamblers) (Goldstein et al., 2013). High-consequence gamblers were more likely to use substances, engage in violent and delinquent behaviors, and report negative peer influences than low-consequence gamblers. The extant literature on latent-class patterns among adolescents indicates that gambling pathology risk is multifaceted and ranges from low to high risks, although there is no consensus on adolescent gambling classes; thus, identifying classes of adolescent gamblers is an important clinical and research goal. Furthermore, assessing risk and health/functioning characteristics that uniquely characterize these classes is crucial, given the co-morbidities between PG and PrG and psychiatric and medical disorders (Erickson et al., 2005; Petry et al., 2005; Morasco et al., 2006; Desai and Potenza, 2008).

Among adults, strong comorbidities between lifetime PG and major depression, generalized anxiety and substance-use disorders exist (Petry et al., 2005). Among adolescents, PG and PrG are associated with substance use, depression, aggressive behaviors, poor school performance (Ellenbogen et al., 2007; Yip et al., 2011a), and demographic characteristics (eg, male sex and living in a single-parent family home) (Gupta and Derevensky, 1998; Fisher, 1999; Desai et al., 2005). Pathological gambling and problem gambling in these studies were classified on the basis of clinical experiences or expert consensus, and to our knowledge studies have not examined empirically derived latent classes of adolescent gambling classes with various health functioning and risk behaviors. Thus, we used a data-derived approach by conducting LCA using the 10 DSM-IV PG and the 9 DSM-V GD inclusionary criteria among high school–aged adolescents who reported past-year gambling. We then used logistic regression analyses to examine the relationships between gambling classes and various gambling behaviors and health/functioning characteristics.

On the basis of prior studies of adolescent and adult gamblers (Xian et al., 2008; Hong et al., 2009; McBride et al., 2010; Carragher and McWilliams, 2011; Faregh and Derevensky, 2011; Goldstein et al., 2013), we hypothesized that heterogeneous gambling classes would be identified. We also hypothesized that higher-risk/PrG classes would be associated with male sex, poorer academic performances, less engagement in extracurricular activities, and greater likelihoods of substance use, aggressive behaviors, depressed mood, being overweight, and more severe gambling behaviors.

METHODS

Procedures

All public 4-year and nonvocational or special education high schools in Connecticut were invited to participate in the study. Ten high schools participated in this survey study in 2006 to 2007, for a total sample size of 4523. Although this is not a random sample of high school students in Connecticut, the inclusion of the schools in each of the 3 tiers of the state’s district reference groups ensures adequate socioeconomic representation within the study sample. District reference groups are groupings of schools on the basis of the socioeconomic status of the families in the school district.

Recruitment and study procedure have been described previously (Schepis et al., 2008; Potenza et al., 2011; Yip et al., 2011b). In brief, the research staff explained the voluntary, anonymous, and confidential nature of the study before survey administration in an assembly setting in each school.

Passive consent procedures were used to obtain consent from parents—letters were sent to parents informing them about the study and outlining the procedure by which they could deny permission for their child to participate. If no message was received from a parent, parental permission was assumed. All participating school boards and/or school superintendents and the institutional review board of the Yale University approved the study procedures.

Measures

Demographic variables included sex, grade, age, race, and family structure (eg, living with 2 parents or with a single parent).

Twelve questions from the Massachusetts Gambling Screen (MAGS) (Shaffer et al., 1994) assessed the 10 DSM-IV and 9 DSM-V criteria for PG and GD, respectively. This scale has a Cronbach α of 0.87 and successfully classified 96% of the adolescent gamblers as either PG, in transition, or non-PG (Shaffer et al., 1994). Two MAGS items assessed gambling tolerance (gambling larger amounts of money to get the same level of excitement and finding that the same amount of gambling had less effect than before) and 2 items assessed gambling to escape (gambling to reduce uncomfortable feelings as a result of reducing gambling and gambling to reduce negative feelings). Endorsement of either item was scored as meeting the respective criterion as was done previously (Potenza et al., 2011; Yip et al., 2011a).

Assessments of gambling and health and functioning were coded as described previously (Yip et al., 2011a) and are detailed in the supplementary materials (Supplemental Digital Content 1, available at http://links.lww.com/JAM/A19).

DATA ANALYSIS

We used Mplus version 7.0 (Muthén and Muthén, 1998–2012) to conduct LCA of PG/GD criteria on adolescents who reported past-year gambling (N = 3901). Missing data were assumed to be missing at random, and Mplus uses all data available to estimate the model using full information maximum likelihood. The 10 MAGS items that correspond to the DSM-IV PG criteria and the 9 MAGS items (without the item assessing committing illegal acts to finance gambling) that correspond to the DSM-V GD criteria were entered into separate LCAs. To determine the optimal model, 1- to 9-class unconditional LCAs were conducted and their relative fits were compared. The best-fitting models were assessed on the basis of smaller Bayesian Information Criteria (BICs), sample size–adjusted BICs, Akaike Information Criterion values, higher entropy values, and Lo-Mendell-Rubin (LMR) and bootstrapped likelihood ratio (LR) tests. We also considered theory, parsimony, interpretability, and average latent class probabilities of the solutions in determining the final models (Muthen, 2004; Nylund et al., 2007). The LCA modeling uses criterion-endorsement probabilities to determine the likelihood that each criterion is endorsed for each class, and each participant was assigned to the class having the greatest posterior probability. Once the optimal class solution was identified, we used logistic regression using SPSS version 19 to calculate odds ratios with latent classes as an independent variable, with the lowest-risk gambling class as the reference group and gambling, risk, and health functioning behavior variables as separate dependent variables.

RESULTS

Latent Class Analyses

The LCAs of the 10 and 9 inclusionary criteria for PG and GD, respectively, indicated that the 4-class solution was determined to be best (Table 1). The 4-class solution of the 10-criteria model had the lowest BIC value, one of the most reliable information criteria (Nylund et al., 2007), and the largest class solution to have significant LMR and bootstrapped LR tests (P < 0.001). For the 9-criteria model, the 4-class solution was also determined to be optimal, having the most parsimonious solution. It had the lowest BIC value, a relatively high entropy value, and a significant bootstrapped LR test. Although the LMR test was not significant for the 4-class solution as it was for the 3-class solution, the 3-class solution did not provide a useful class differentiation beyond symptom severity (ie, simple high, medium, and low probability classes).

TABLE 1.

Fit Indices of Latent Class Analyses of the Inclusionary Criteria for Pathological Gambling (10 Items) or Gambling Disorder (9 Items)

| No. Classes | Log-Likelihood | G2 | AIC | BIC | Adjusted BIC | Entropy | LMR Test | Bootstrapped LR Test |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 items | ||||||||

| 1 | −6,341.49 | 1,573.95 | 12,702.98 | 12,765.67 | 12,733.90 | 1.00 | NA | NA |

| 2 | −4,806.32 | 2,547.13 | 9,654.64 | 9,786.29 | 9,719.56 | 0.92 | P < 0.001 | P < 0.001 |

| 3 | −4,632.40 | 2,480.41 | 9,328.81 | 9,529.41 | 9,427.73 | 0.80 | P = 0.008 | P < 0.001 |

| 4 | −4,573.58 | 2,296.69 | 9,233.17 | 9,502.73 | 9,366.10 | 0.83 | P = 0.006 | P < 0.001 |

| 5 | −4,542.85 | 1,879.97 | 9,193.69 | 9,532.22 | 9,360.63 | 0.83 | P = 0.022 | P < 0.001 |

| 6 | −4,523.65 | 1,904.63 | 9,177.30 | 9,584.78 | 9,378.24 | 0.83 | P = 0.307 | P < 0.001 |

| 7 | −4,506.86 | 1,766.75 | 9,165.72 | 9,642.16 | 9,400.67 | 0.86 | P = 0.080 | P < 0.001 |

| 8 | −4,494.29 | 1,712.22 | 9,162.58 | 9,707.99 | 9,431.54 | 0.82 | P = 0.208 | P = 0.146 |

| 9 | −4,479.84 | 1,581.26 | 9,155.68 | 9,770.04 | 9,458.65 | 0.82 | P = 0.040 | P = 0.040 |

| 9 items (without the item assessing committing illegal acts to finance gambling) | ||||||||

| 1 | −5,755.08 | 1,670.77 | 1,1528.17 | 1,1584.59 | 1,1555.99 | 1.00 | NA | NA |

| 2 | −4,388.56 | 1,617.91 | 8,815.11 | 8,934.22 | 8,873.85 | 0.93 | P < 0.001 | P < 0.001 |

| 3 | −4,248.80 | 1,670.85 | 8,555.59 | 8,737.39 | 8,645.25 | 0.79 | P < 0.001 | P < 0.001 |

| 4 | −4,196.71 | 1,050.92 | 8,471.42 | 8,715.91 | 8,591.99 | 0.84 | P = 0.207 | P < 0.001 |

| 5 | −4,165.50 | 1,068.39 | 8,429.00 | 8,736.18 | 8,580.48 | 0.83 | P = 0.071 | P < 0.001 |

| 6 | −4,147.30 | 932.71 | 8,412.59 | 8,782.46 | 8,594.99 | 0.84 | P = 0.072 | P < 0.001 |

| 7 | −4,131.32 | 967.67 | 8,400.63 | 8,833.19 | 8,613.94 | 0.87 | P = 0.008 | P < 0.001 |

| 8 | −4,119.23 | 846.45 | 8,396.45 | 8,891.70 | 8,640.68 | 0.88 | P = 0.503 | P = 0.077 |

| 9 | −4,107.68 | 803.47 | 8,393.36 | 8,951.30 | 8,668.50 | 0.81 | P = 0.110 | P = 0.200 |

Text in bold indicates the optimal class solution; G2, goodness of fit statistics; AIC, Akaike Information Criterion; BIC, Bayesian Information Criterion; LMR, Lo-Mendell-Rubin; LR, likelihood ratio; NA, not available.

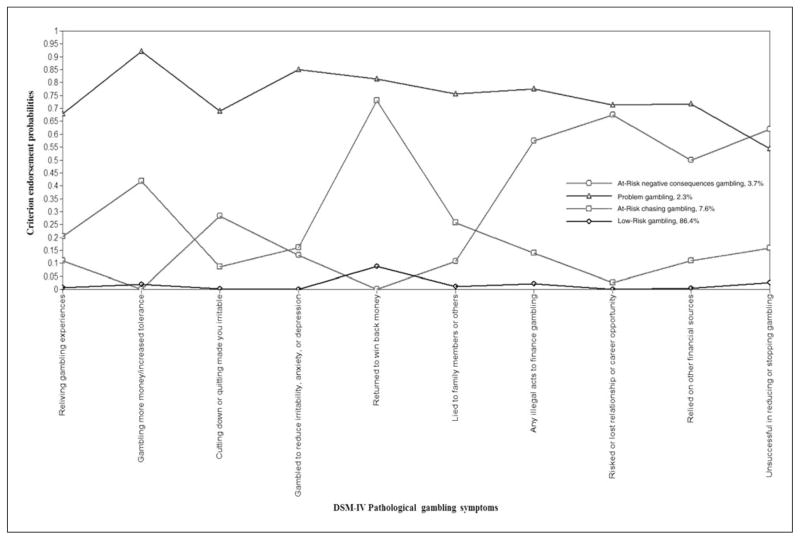

Because the 2 models only differed on 1 criterion and produced a comparable number of classes, we used the 4-class solution derived from the 10-item model (DSM-IV) to assess associations with gambling and health/functioning characteristics. The 4 classes were labeled as follows: low-risk gambling (LG), at-risk chasing gambling (ACG), at-risk negative consequences gambling (ANCG), and PrG.

The DSM-IV model showed that the LG class was most prevalent (86.4%), characterized by low probability for all 10 criteria; the ACG class was second most prevalent (7.6%), characterized by relatively elevated probabilities of gambling to win back lost money and gambling more money over time; the ANCG class was third most prevalent (3.7%), characterized by relatively elevated probabilities of losing/jeopardizing relationship or career opportunities, committing illegal acts to support gambling, turning to other financial sources to support gambling, and unsuccessful attempts to reduce or quit gambling; and the PrG class (2.3%) had high probability for all 10 criteria (Fig. 1).

FIGURE 1.

Four-class solution using the 10 inclusionary criteria for PG (N = 3901).

Logistic Regression Analyses

Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics and Table 3 presents odds ratios and confidence intervals for the associations among latent classes and demographic, gambling, and health/functioning variables.

TABLE 2.

Sample Characteristics Overall and by Latent Classes

| Total Sample (N = 3,901) | Class 1: Low-Risk Gambling (LG: 81.4%) | Class 2: At-Risk Gambling Chasing (ACG: 6.0%) | Class 3: At-Risk Negative Consequences Gambling (ANCG: 63.0%) | Class 4: Problem Gambling (PrG: 0.9%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic variables (%) | |||||

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 48.5 | 45.3 | 78.5 | 77.7 | 64.9 |

| Race | |||||

| White | 68.3 | 70.1 | 59.8 | 40.5 | 37.8 |

| Multirace | 9.4 | 8.5 | 9.6 | 31.0 | 24.3 |

| African American | 6.8 | 6.6 | 8.8 | 8.6 | 8.1 |

| Hispanic | 7.3 | 7.1 | 10.0 | 6.9 | 10.8 |

| Other | 2.8 | 2.7 | 4.4 | 2.8 | 0.0 |

| Asian | 2.2 | 2.1 | 2.0 | 4.6 | 2.7 |

| Grade | |||||

| 9th | 31.4 | 31.1 | 34.7 | 28.4 | 45.9 |

| 10th | 26.9 | 27.1 | 23.9 | 26.7 | 27.0 |

| 11th | 25.2 | 25.7 | 20.3 | 21.6 | 18.9 |

| 12th | 16.3 | 15.9 | 20.8 | 21.6 | 8.1 |

| Age, y | |||||

| <14 | 13.9 | 14.2 | 9.6 | 14.7 | 21.6 |

| 15–17 | 54.2 | 54.4 | 53.0 | 47.4 | 64.9 |

| 18+ | 10.0 | 9.6 | 14.3 | 18.1 | 2.7 |

| Grade average | |||||

| A+B | 55.0 | 59.6 | 43.0 | 37.9 | 35.1 |

| C | 29.9 | 29.5 | 35.1 | 29.3 | 35.1 |

| D+F | 12.1 | 11.1 | 17.5 | 28.4 | 27.0 |

| Family structure | |||||

| Others | 5.5 | 4.5 | 9.2 | 21.6 | 18.9 |

| 1 parent | 23.4 | 23.4 | 23.5 | 20.7 | 35.1 |

| 2 parents | 69.6 | 70.7 | 64.9 | 52.6 | 45.9 |

| Gambling variables (%) | |||||

| Form of gambling | |||||

| Strategic | 93.0 | 92.4 | 98.8 | 96.6 | 100.0 |

| Non-strategic | 68.1 | 66.7 | 76.9 | 90.5 | 70.3 |

| Machine | 38.2 | 33.6 | 74.5 | 86.2 | 73.0 |

| Location of gambling | |||||

| Online | 12.7 | 9.0 | 37.1 | 66.4 | 32.4 |

| School grounds | 24.9 | 19.9 | 65.7 | 78.4 | 48.6 |

| Casino | 6.6 | 3.9 | 14.7 | 62.9 | 27.0 |

| Gambling motivations | |||||

| Excitement | 63.2 | 31.8 | 84.9 | 78.4 | 54.1 |

| Finance | 29.4 | 24.0 | 78.1 | 77.6 | 54.1 |

| Escape | 16.5 | 12.5 | 53.0 | 65.6 | 37.8 |

| Social | 20.4 | 16.8 | 53.4 | 53.4 | 27.0 |

| Gambling urges | |||||

| Pressure to gamble | 5.5 | 21.6 | 43.1 | 16.3 | 3.3 |

| Anxiety relieved by gambling | 3.2 | 18.9 | 56.0 | 10.8 | 0.8 |

| Gambling partners | |||||

| Adults | 7.2 | 5.0 | 23.5 | 33.6 | 21.6 |

| Family | 18.4 | 16.6 | 39.0 | 30.2 | 18.9 |

| Friends | 38.4 | 34.3 | 85.7 | 60.3 | 43.2 |

| Strangers | 4.7 | 2.2 | 17.9 | 50.9 | 8.1 |

| Alone | 4.6 | 2.5 | 15.1 | 42.2 | 16.2 |

| Time spent gambling | |||||

| >1 h/wk | 2.8 | 1.1 | 7.6 | 43.1 | 10.8 |

| Age of onset of gambling | |||||

| ≤8 | 6.8 | 4.9 | 11.2 | 49.1 | 18.9 |

| 9–11 | 7.0 | 5.9 | 17.9 | 16.4 | 8.1 |

| 12–14 | 16.2 | 14.7 | 36.7 | 14.7 | 29.7 |

| 15+ | 13.6 | 12.0 | 28.7 | 10.3 | 10.8 |

| Health/functioning variables (%) | |||||

| Extracurricular activities | 75.9 | 75.8 | 78.9 | 78.4 | 56.8 |

| Substance use | |||||

| Smoking ever | |||||

| Marijuana ever | 38.0 | 36.1 | 48.6 | 74.1 | 35.1 |

| Alcohol ever | 82.0 | 82.1 | 80.9 | 83.6 | 75.7 |

| Alcohol-past 30 d | 47.6 | 45.9 | 56.2 | 75.9 | 62.2 |

| Other drug use ever | 8.5 | 6.9 | 12.4 | 48.3 | 16.2 |

| Caffeine use | |||||

| None | 17.9 | 17.7 | 19.9 | 19.0 | 21.6 |

| 1–2 | 50.5 | 52.2 | 40.6 | 21.6 | 45.9 |

| 3 or more | 24.9 | 23.6 | 33.1 | 50.0 | 18.9 |

| Aggression | |||||

| Serious fights | 19.8 | 16.8 | 37.1 | 62.1 | 45.9 |

| Carry weapon | 7.1 | 5.0 | 16.7 | 44.8 | 27.0 |

| Mood | |||||

| Depressed | 20.4 | 19.4 | 23.1 | 38.8 | 40.5 |

| Body mass index | |||||

| Normal | 61.0 | 62.1 | 56.6 | 43.1 | 43.2 |

| Underweight | 19.8 | 19.0 | 20.3 | 38.8 | 35.1 |

| Overweight | 13.4 | 13.2 | 15.1 | 12.9 | 13.5 |

| Obese | 5.8 | 5.6 | 8.0 | 5.2 | 8.1 |

ACG, at-risk chasing gambling; ANCG, at-risk negative consequences gambling; LG, low-risk gambling; PrG, problem gambling.

TABLE 3.

Associations Between Latent Classes and Demographic, Gambling, and Health/Functioning Measures*

| Class 2 (ACG) OR (CI 95%)† |

Class 3 (ANCG) OR (CI 95%)† |

Class 4 (PrG) OR (CI 95%)† |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic variables | |||

| Sex | |||

| Male | 4.58 (3.34–6.28) | 4.13 (2.63–6.47) | 2.59 (1.26–5.30) |

| Race | |||

| White (reference) | |||

| Multirace | 1.33 (0.85–2.07) | 6.35 (4.05–9.96) | 5.33 (2.29–12.42) |

| African American | 1.55 (0.97–2.47) | 2.25 (1.12–4.51) | 2.27 (0.65–7.94) |

| Hispanic | 1.66 (1.06–2.58) | 1.69 (0.79–3.62) | 2.84 (0.93–8.69) |

| Other | 1.89 (0.99–3.61) | 1.65 (0.50–5.39) | — |

| Asian | 1.09 (0.43–2.74) | 3.48 (1.35–9.00) | 2.34 (0.30–18.00) |

| Grade | |||

| 9th (reference) | |||

| 10th | 0.79 (0.56–1.11) | 1.08 (0.66–1.77) | 0.68 (0.31–1.48) |

| 11th | 0.71 (0.50–1.01) | 0.92 (0.54–1.55) | 0.50 (0.21–1.21) |

| 12th | 1.17 (0.81–1.67) | 1.48 (0.87–2.51) | 0.34 (0.10–1.18) |

| Age | |||

| <14 (reference) | |||

| 15–17 | 1.44 (0.92–2.25) | 0.84 (0.48–1.46) | 0.78 (0.35–1.75) |

| 18+ | 2.22 (1.30–3.80) | 1.83 (0.95–3.52) | 0.19 (0.02–1.49) |

| Grade average | |||

| A+B (reference) | |||

| C | 1.56 (1.17–2.09) | 1.48 (0.94–2.33) | 1.92 (0.89–4.15) |

| D+F | 2.08 (1.44–3.00) | 3.60 (2.24–5.77) | 3.93 (1.71–9.02) |

| Family structure | |||

| 2 parents (reference) | |||

| 1 parent | 1.09 (0.80–1.49) | 1.19 (0.74–1.92) | 2.31 (1.12–4.78) |

| Others | 2.21 (1.39–3.52) | 6.42 (3.92–10.50) | 6.45 (2.63–15.77) |

| Gambling variables | |||

| Form of gambling | |||

| Strategic | 6.81 (2.17–21.39) | 2.31 (0.84–6.30) | — |

| Nonstrategic | 1.66 (1.23–2.25) | 4.76 (2.55–8.90) | 1.18 (0.58–2.40) |

| Machine | 5.77 (4.31–7.73) | 12.34 (7.24–21.01) | 5.33 (2.57–11.05) |

| Location of gambling | |||

| Online | 6.03 (4.55–8.00) | 20.24 (13.50–30.37) | 5.00 (2.47–10.09) |

| School grounds | 7.75 (5.89–10.20) | 14.53 (9.26–22.79) | 3.78 (1.97–7.24) |

| Casinos | 4.22 (2.86–6.23) | 42.23 (27.85–64.04) | 9.35 (4.42–19.77) |

| Gambling motivations | |||

| Excitement | 12.04 (8.46–17.12) | 7.82 (4.99–12.24) | 2.53 (1.32–4.84) |

| Finance | 11.27 (7.27–15.35) | 10.95 (7.03–17.06) | 3.72 (1.94–7.14) |

| Escape | 6.23 (4.77–8.14) | 13.34 (8.98–19.82) | 4.27 (2.18–8.37) |

| Social | 5.67 (4.35–7.37) | 5.68 (3.90–8.27) | 1.83 (0.88–3.81) |

| Gambling urges | |||

| Pressure to gamble | 5.68 (3.87–8.33) | 22.76 (15.03–34.47) | 8.20 (3.66–18.37) |

| Anxiety relieved by gambling | 9.00 (5.18–15.62) | 103.85 (60.57–178.05) | 24.60 (9.60–63.04) |

| Gambling partners | |||

| Adults | 5.79 (4.17–8.04) | 9.54 (6.31–14.43) | 5.20 (2.34–11.53) |

| Family | 3.22 (2.46–4.22) | 2.17 (1.45–3.26) | 1.17 (0.51–2.69) |

| Friends | 11.43 (7.98–16.38) | 2.91 (2.00–4.25) | 1.46 (0.76–2.81) |

| Strangers | 9.82 (6.62–14.57) | 46.51 (30.28–71.44) | 3.97 (1.19–13.19) |

| Alone | 6.98 (4.65–10.47) | 28.62 (18.70–43.79) | 7.57 (3.08–18.62) |

| Time spent gambling | |||

| >1 h/wk | 7.66 (4.34–13.53) | 70.84 (43.41–115.62) | 11.34 (3.82–33.61) |

| Age of onset of gambling | |||

| ≤8 | 1.00 (0.62–1.60) | 12.19 (6.38–23.28) | 4.49 (1.30–15.54) |

| 9–11 | 1.33 (0.89–2.01) | 3.38 (1.61–7.09) | 1.60 (0.36–7.22) |

| 12–14 | 1.11 (0.79–1.54) | 1.23 (0.58–2.60 | 2.38 (0.75–7.53) |

| 15+ (reference) | |||

| Health/functioning variables | |||

| Extracurricular activities | 1.19 (0.87–1.63) | 1.16 (0.74–1.82) | 0.42 (0.22–0.81) |

| Substance use | |||

| Smoking ever | 1.61 (1.24–2.09) | 4.07 (2.65–6.25) | 1.95 (0.96–3.97) |

| Marijuana ever | 1.78 (1.36–2.34) | 7.40 (4.43–12.37) | 1.36 (0.60–2.63) |

| Alcohol ever | 0.99 (0.65–1.49) | 1.06 (0.58–1.95) | 0.61 (0.25–1.49) |

| Alcohol-past 30 d | 1.21 (0.89–1.64) | 3.65 (2.03–6.56) | 2.07 (0.84–5.10) |

| Other drug use ever | 2.12 (1.41–3.19) | 15.33 (9.98–23.56) | 2.91 (1.17–7.25) |

| Caffeine use | |||

| None (reference) | |||

| 1–2 | 0.69 (0.49–0.98) | 0.39 (0.22–0.69) | 0.72 (0.31–1.68) |

| 3 or more | 1.25 (0.86–1.80) | 1.98 (1.20–3.27) | 0.66 (0.24–1.82) |

| Aggression | |||

| Serious fights | 2.91 (2.22–3.81) | 8.08 (5.50–11.88) | 4.20 (2.19–8.06) |

| Carry weapon | 3.84 (2.67–5.53) | 15.52 (10.44–23.07) | 7.07 (3.37–14.85) |

| Mood | |||

| Depressed | 1.31 (0.96–1.79) | 3.41 (2.25–5.15) | 4.28 (2.03–9.03) |

| Weight | |||

| Normal (reference) | |||

| Underweight | 1.17 (0.84–1.64) | 2.94 (1.95–4.40) | 2.66 (1.27–5.55) |

| Overweight | 1.26 (0.87–1.82) | 1.41 (0.78–2.53) | 1.47 (0.54–4.02) |

| Obese | 1.56 (0.96–2.55) | 1.33 (0.56–3.14) | 2.08 (0.60–7.20) |

Reference group is the low-risk gambling (LG) class.

OR and CI in bold are statistically significant at P < 0.05.

CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

Demographic Variables

Compared with the LG class, other gambling classes were more likely to be associated with male sex (P ≤ 0.009), lower school grades (P ≤ 0.001), and living with adults other than their parents (P ≤ 0.001). The PrG class was associated with higher likelihood of living with 1 parent than the LG class (P = 0.024).

Compared with the LG class, the ACG class was more likely to be associated with Hispanic ethnicity (P = 0.026), the ANCG class with multiple (P ≤ 0.001), African American (P = 0.022), and Asian (P = 0.045) races, and the PrG class with multiple races (P ≤ 0.001). The ACG class was more likely to include those aged 18 years or older than the LG class (P = 0.003).

Gambling Variables

Form of gambling

Compared with the LG class, the ACG class demonstrated stronger associations with strategic gambling, the ACG and ANCG classes demonstrated stronger associations with nonstrategic gambling, and the ACG, ANCG, and PrG classes showed stronger associations with machine gambling (P ≤ 0.001).

Gambling locations

Compared with the LG class, other gambling classes showed stronger associations with gambling online, on school grounds, and at casinos (P ≤ 0.005).

Gambling motivations

Compared with the LG class, other gambling classes were more likely to gamble for excitement, for financial reasons, and to escape/relieve dysphoria (P ≤ 0.001). Compared with the LG class, the ACG and ANCG classes were more strongly associated with motivations to gamble for social reasons (P ≤ 0.001).

Gambling urge

Compared with the LG class, other gambling classes showed stronger associations with feeling pressure to gamble and relief of anxiety only by gambling (P ≤ 0.001).

Gambling partners/time spent on gambling

Compared with the LG class, other gambling classes showed stronger associations with gambling with adults and strangers, gambling alone, and spending more than 1 hour per week gambling (P ≤ 0.025). The ACG and ANCG classes showed stronger associations with gambling with friends and family than the LG class (P ≤ 0.001).

Gambling age of onset

Compared with the LG class, the ANCG and PrG classes were more strongly associated with younger gambling age of onset, with the ANCG and PrG classes more strongly associated with initiating gambling at 8 years old or younger (P ≤ 0.018) and the ANCG at 9 to 11 years old (P = 0.002).

Health/Functioning Variables

Extracurricular activities

The PrG class was less strongly associated with extracurricular activity participation than the LG class (P = 0.009).

Substance use

Compared with the LG class, other gambling classes were more strongly associated with ever trying other drugs (P ≤ 0.022), the ACG and ANCG classes were more strongly associated with lifetime cigarette and marijuana use (P ≤ 0.001), and only the ANCG class showed stronger association with drinking alcohol in the past 30 days (P ≤ 0.001). Compared with the LG class, the ACG and ANCG (P = 0.001) classes were less likely to consume 1 to 2 caffeinated drinks per day (P ≤ 0.039), and the ANCG class showed stronger associations with 3 or more caffeinated drinks (P = 0.008).

Aggression

Compared with the LG class, other gambling classes were more likely to get into serious fights and carry weapons (P ≤ 0.001).

Mood, body mass index

The ANCG and PrG classes showed stronger association than the LG class with depressed mood (P ≤ 0.001) and being underweight (P ≤ 0.009).

DISCUSSION

Using a sample of past-year adolescent gamblers, LCA identified the following 4 gambling classes: LG, ACG, ANCG, and PrG. These classes were determined to be best fitting using both the DSM-IV and DSM-V criteria for PG and GD, respectively. These classes show similarities to those identified in previous examination of adolescent gamblers (Faregh and Derevensky, 2011) and also differences from adult gamblers (Xian et al., 2008; Hong et al., 2009; McBride et al., 2010; Carragher and McWilliams, 2011). The inclusion or exclusion of the “illegal acts” criterion from LCA models had little effect on the classification of gambling groups, a finding that corroborates the decision to omit this criterion from the DSM-V (Zimmerman et al., 2006). In this study, we reported the results from the 4 latent classes using the 10 inclusionary criteria model.

Most (86.4%) past-year adolescent gamblers were classified as LG, and this class exhibited a low probability of endorsing any inclusionary criteria for PG. The PrG was the smallest class (2.3%); this class exhibited high endorsement probabilities for all criteria. Between the 2 classes were 2 at-risk/ PrG classes—ACG (7.6%) and ANCG (3.7%). Among the ACG class, there was a high probability of chasing and increased tolerance. Chasing refers to continuing to gamble to recover gambling-related losses. Among adult gamblers, chasing characterizes the lowest level of PrG severity and mainly seems to differentiate between no-symptom and few-symptom gamblers (Toce-Gerstein et al., 2003; Xian et al., 2008). The ANCG class had elevated probabilities of endorsing multiple PG criteria that indicated various difficulties due to gambling. Different symptom profiles among at-risk/PrG classes suggest that adolescents who may not meet PG criteria may still experience impairments relating to their gambling (Carragher and McWilliams, 2011).

Consistent with previous findings (Yip et al., 2011a), at-risk/PrG classes engaged in risky gambling behaviors and experienced poor health/functioning characteristics. Compared with the LG class, at-risk/PrG classes showed greater associations with various gambling behaviors. These classes also displayed more aggressive (getting into serious fights, carrying weapons, and so on) and substance-use (trying other drugs) behaviors.

Unlike most LCA findings that showed that the class with high probability on all 10 criteria experienced poorer outcomes than classes with endorsement of fewer criteria, we found that the ANCG class that had higher probability on 4 criteria shared similar risk factors as the PrG class that had high probability on all 10 criteria. Both classes had greater likelihoods of having younger ages of gambling onset, being underweight, and experiencing negative mood than the LG class. There were also notable differences between 2 classes—the PrG class seemed to lack social protective factors. For instance, the PrG class was less likely to be involved in extracurricular activities than the LG class, whereas the ANCG class did not differ. Problem gambling was also the only class that did not differ from LG in ever having tried caffeine, tobacco, or marijuana. Experimenting with commonly used substances such as caffeine, alcohol, and tobacco could arguably be normative social behaviors that occur in adolescence, given that 90% of adult smokers initiate during this age (US Department of Health and Human Services, 2012) and 78% of adolescents have consumed alcohol (Swendsen et al., 2011). However, the PRG class was more likely to have tried other drugs, suggesting that they are at risk for problematic, high-risk behaviors. Interestingly, even though the PrG class engaged in similar gambling behaviors as the ACG and ANCG classes, they differed in social aspects of gambling. Compared with the LG class, the PrG class was more likely to report gambling alone and with strangers and adults but did not differ in their reports of gambling with friends and family. Consistent with the resilience framework that suggests that protective factors such as social bonding and feeling connected to school, family, and community correlated with lower PrG severity (Lussier et al., 2007), members in the PrG class may experience greater problems associated with gambling because they lack these social protective factors. These findings suggest that clinicians working with adolescent gamblers should incorporate individualized screening to assess social risk factors, and interventions should focus on teaching social skills to mitigate PrG behaviors.

There are several limitations to this study. The cross-sectional nature of the data prevents us from assessing the temporal precedence of psychiatric/health impairments and gambling problems. Future studies should examine gambling and psychiatric/health trajectories using longitudinal designs. As adolescents reach the legal gambling age, their gambling behaviors may change because they have legal access to age-restricted venues and the classification of gambling classes and patterns of associations with gambling-related and health variables may also change over time. Other study limitations include recall bias and the absence of clinician-validated PG criteria.

The strength of this study is using LCA to identify classes rather than using the number of PG criteria endorsed. The LCA methodology accounts for a number of criteria and the overall pattern of criterion endorsement without a priori assumptions about precise number of classes (Xian et al., 2008). This method allows for a complementary and arguably more detailed understanding of PrG and extends categorical conceptualizations of PG on the basis of expert consensus to subtypes based on data-driven analyses.

CONCLUSIONS

This study underscores the importance of considering different characteristics of adolescent gambling classes and their characteristics. The increased likelihood of risk behaviors endorsed by the ANCG class highlights that subclinical gamblers may be an important group to target with respect to intervention efforts. Furthermore, findings suggest that interventions for the PrG class should focus on enhancing social protective factors to reduce gambling problems.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Dr Potenza has received financial support or compensation for the following: Dr Potenza has consulted for and advised Somaxon, Boehringer Ingelheim, Lundbeck, and Ironwood; has received research support from the National Institutes of Health, Veteran’s Administration, Mohegan Sun Casino, the National Center for Responsible Gaming, Forest Laboratories, Ortho-McNeil, Oy-Control/Biotie, Glaxo-SmithKline, and Psyadon pharmaceuticals; has participated in surveys, mailings, or telephone consultations related to drug addiction, impulse control disorders, or other health topics; has consulted for law offices and the federal public defender’s office in issues related to impulse control disorders; provides clinical care in the Connecticut Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services Problem Gambling Services Program and The Connection; has performed grant reviews for the National Institutes of Health and other agencies; has guest-edited journal sections or journals; has given academic lectures in grand rounds, CME events, and other clinical or scientific venues; and has generated books or book chapters for publishers of mental health texts.

This research was supported in part by grants RL1 AA017539 and R01 DA018647 from the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD; the Connecticut State Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services, Hartford, CT; the Connecticut Mental Health Center, New Haven, CT; and a Center of Excellence in Gambling Research Award from the National Center for Responsible Gaming. The funding agencies did not provide input or comment on the content of the manuscript, and the content of the manuscript reflects the contributions and thoughts of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the funding agencies.

Footnotes

The authors report no conflicts of interest with respect to the content of this manuscript.

The other authors report no disclosures. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this manuscript.

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citation appears in the printed text and is provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal’s Web site (http://www.journaladdictionmedicine.com).

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. text revision. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes GM, Welte JW, Hoffman JH, et al. Gambling, alcohol, and other substance use among youth in the United States. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2009;70:134–142. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaszczynski A, Nower L. A pathways model of problem and pathological gambling. Addiction. 2002;97:487–499. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00015.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carragher N, McWilliams LA. A latent class analysis of DSM-IV criteria for pathological gambling: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Psychiatry Res. 2011;187:185–192. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2010.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai RA, Maciejewski PK, Pantalon MV, et al. Gender differences in adolescent gambling. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2005;17:249–258. doi: 10.1080/10401230500295636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai RA, Potenza MN. Gender differences in the associations between past-year gambling problems and psychiatric disorders. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2008;43:173–183. doi: 10.1007/s00127-007-0283-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellenbogen S, Derevensky J, Gupta R. Gender differences among adolescents with gambling-related problems. J Gambl Stud. 2007;23:122–143. doi: 10.1007/s10899-006-9048-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson L, Molina CA, Ladd GT, et al. Problem and pathological gambling are associated with poorer mental and physical health in older adults. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;20:754–759. doi: 10.1002/gps.1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faregh N, Derevensky J. A comparative latent class analysis of endorsement profiles of DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for problem gambling among adolescents from a community and a treatment sample. Addict Res Theory. 2011;19:323–333. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher S. A prevalence study of gambling and problem gambling in British adolescents. Addict Res Theory. 1999;7:509–538. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein AL, Faulkner B, Cunningham RM, et al. A latent class analysis of adolescent gambling: application of resilience theory. Int J Mental Health Addict. 2013;11:13–30. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta R, Derevensky JL. Adolescent gambling behavior: a prevalence study and examination of the correlates associated with problem gambling. J Gambl Stud. 1998;14:319–345. doi: 10.1023/a:1023068925328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong S, Sacco P, Cunningham-Williams RM. An empirical typology of lifetime and current gambling behaviors: association with health status of older adults. Aging Ment Health. 2009;13:265–273. doi: 10.1080/13607860802459849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lussier I, Derevensky J, Gupta R, et al. Youth gambling behaviors: an examination of the role of resilience. Psychol Addict Behav. 2007;21:165–173. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.21.2.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch WJ, Maciejewski PK, Potenza MN. Psychiatric correlates of gambling in adolescents and young adults grouped by age at gambling onset. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:1116–1122. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.11.1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBride O, Adamson G, Shevlin M. A latent class analysis of DSM-IV pathological gambling criteria in a nationally representative British sample. Psychiatry Res. 2010;178:401–407. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2009.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milosevic A, Ledgerwood DM. The subtyping of pathological gambling: a comprehensive review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2010;30:988–998. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morasco BJ, Pietrzak RH, Blanco C, et al. Health problems and medical utilization associated with gambling disorders: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Psychosom Med. 2006;68:976–984. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000238466.76172.cd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthen B. Latent variable analysis: growth mixture modeling and related techniques for longitudinal data. In: Kaplan D, editor. Handbook of Quantitative Methodology for the Social Sciences. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2004. pp. 345–368. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User’s Guide. 7. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén and Muthén; 1998–2012. [Google Scholar]

- Nower L, Blaszczynski A. The Pathways model as harm minimization for youth gamblers in educational settings. Child Adolesc Soc Work J. 2004;21:25–47. [Google Scholar]

- Nylund KL, Asparouhov T, Muthen B. Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: a Monte Carlo simulation study. Struct Equation Model. 2007;14:535–569. [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM, Stinson FS, Grant BF. Comorbidity of DSM-IV pathological gambling and other psychiatric disorders: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66:564–574. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n0504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potenza MN. Neurobiology of gambling behaviors. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2013;23:660–667. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2013.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potenza MN, Wareham JD, Steinberg MA, et al. Correlates of at-risk/problem internet gambling in adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;50:150–159. e153. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schepis TS, Desai RA, Smith AE, et al. Impulsive sensation seeking, parental history of alcohol problems, and current alcohol and tobacco use in adolescents. J Addict Med. 2008;2:185–193. doi: 10.1097/adm.0b013e31818d8916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer HJ, Hall MN. Updating and refining prevalence estimates of disordered gambling behaviour in the United States and Canada. Can J Public Health. 2001;92:168–172. doi: 10.1007/BF03404298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer HJ, Hall MN, Vander Bilt J. Estimating the prevalence of disordered gambling behavior in the United States and Canada: a research synthesis. Am J Public Health. 1999;89:1369–1376. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.9.1369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer HJ, LaBrie R, Scanlan KM, et al. Pathological gambling among adolescents: Massachusetts Gambling Screen (MAGS) J Gambl Stud. 1994;10:339–362. doi: 10.1007/BF02104901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swendsen J, Burstein M, Case B, et al. Use and abuse of alcohol and illicit drugs in US adolescents: results of the National Comorbidity Survey—Adolescent Supplement. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;69:390–398. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.1503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toce-Gerstein M, Gerstein DR, Volberg RA. A hierarchy of gambling disorders in the community. Addiction. 2003;98:1661–1672. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2003.00545.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Preventing Tobacco use Among Youth and Young Adults: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers of Disease Control and Prevention, Office on Smoking and Health; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Williams RJ, Volberg RA, Stevens RMG. Ontario Problem Gambling Research Centre and the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long Term Care. Guelph, Ontario, Canada: Ontario Problem Gambling Research Centre; 2012. The population prevalence of problem gambling: methodological influences, standardized rates, jurisdictional differences, and worldwide trends. [Google Scholar]

- Xian H, Shah KR, Potenza MN, et al. A latent class analysis of DSM-III-R pathological gambling criteria in middle-aged men: association with psychiatric disorders. J Addict Med. 2008;2:85–95. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0b013e31816d699f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yip SW, Desai RA, Steinberg MA, et al. Health/functioning characteristics, gambling behaviors, and gambling-related motivations in adolescents stratified by gambling problem severity: findings from a high school survey. Am J Addict. 2011a;20:495–508. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2011.00180.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yip SW, White M, Grilo C, et al. An exploratory study of clinical measures associated with subsyndromal pathological gambling in patients with binge eating disorder. J Gambl Stud. 2011b;27:257–270. doi: 10.1007/s10899-010-9207-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman M, Chelminski I, Young D. A psychometric evaluation of the DSM-IV pathological gambling diagnostic criteria. J Gambl Stud. 2006;22:329–337. doi: 10.1007/s10899-006-9020-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.