Abstract

Drug-associated stimuli are considered important factors in relapse to drug use. In the absence of drug, these cues can trigger drug craving and drive subsequent drug seeking. One structure that has been implicated in this process is the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST), a chief component of the extended amygdala. Previous studies have established a role for the BNST in cue-induced cocaine seeking. However, it is unclear if the BNST underlies cue-induced seeking of other abused drugs such as ethanol. In the present set of experiments, BNST involvement in ethanol-seeking behavior was assessed in male DBA/2J mice using the conditioned place preference procedure (CPP). The BNST was inhibited during CPP expression using electrolytic lesions (Experiment 1), co-infusion of GABAA and GABAB receptor agonists muscimol and baclofen (M+B; Experiment 2), and activation of inhibitory designer receptors exclusively activated by designer drugs (hM4Di-DREADD) with clozapine-N-oxide (CNO; Experiment 3). The magnitude of ethanol CPP was reduced significantly by each of these techniques. Notably, infusion of M+B (Exp. 2) abolished CPP altogether. Follow-up studies to Exp. 3 showed that ethanol cue-induced c-Fos immunoreactivity in the BNST was reduced by hM4Di activation (Experiment 4) and in the absence of hM4Di, CNO did not affect ethanol CPP (Experiment 5). Combined, these findings demonstrate that the BNST is involved in the modulation of cue-induced ethanol-seeking behavior.

1. Introduction

Drug addiction is a chronic disorder characterized by periods of abstinence and relapse, where relapse to use is often preceded by intense desire for the drug (craving) and the subsequent motivation to obtain the drug (seeking). It is known that environmental contexts and discrete cues therein contribute to relapse by triggering craving (Ehrman et al., 1992; Grant et al., 1996; Sinha & Li, 2007) and driving drug seeking even after sustained periods of abstinence or extinction (Ciccocioppo et al., 2001a, 2001b; Crombag & Shaham, 2002; Krank & Wall, 1990; Weiss et al., 2001; Zironi et al., 2006). These cues become associated with the rewarding and aversive properties of drugs through a Pavlovian learning process. It is the result of this learning, in addition to drug exposure, that leads to alterations in neural structures associated with motivation and reward.

Over the past several decades progress has been made in identifying the neurobiological substrates underlying drug craving and seeking. One neural structure routinely implicated in relapse and drug-seeking processes is the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST), a chief component of the extended amygdala (Alheid, 2003). Anatomically, the BNST is a complex cluster of nuclei and there is some disagreement regarding the total number of subdivisions and their boundaries (Ju & Swanson, 1989; Moga et al., 1989). However, it is clear that the dorsal and ventral subdivisions of the BNST (dBNST and vBNST) send dense projections to the ventral tegmental area (VTA; Dong & Swanson, 2004, 2006a, 2006b; Kudo et al., 2012; Mahler & Aston-Jones, 2012), a region critical for reward seeking (Adamantidis et al., 2011; Bechtholt and Cunningham, 2005; Di Ciano and Everitt, 2004). Moreover, these inputs appear to potently innervate VTA dopamine (DA) neurons (Georges & Aston-Jones, 2001, 2002) leading to their phasic excitation, which is a neural process fundamental to motivated behavior (Adamantidis et al., 2011; Schultz, 1986; Wanat et al., 2009).

Presentation of drug-associated stimuli leads to pronounced activation in dBNST and vBNST, as indicated by increased c-Fos immunoreactivity (Hill, et al., 2007; Mahler & Aston-Jones, 2012). In addition, pharmacological inactivation of several BNST subdivisions has been shown to reduce drug-seeking behavior induced by conditioned cue exposure. For example, inactivating the vBNST blocked the expression of cocaine-induced conditioned place preference (CPP; Sartor & Aston-Jones, 2012). Likewise, inactivation across dBNST and vBNST has been shown to block cue-induced reinstatement of cocaine seeking (Buffalari and See, 2011). In other studies, it appears that vBNST inactivation blocks heroin-primed reinstatement while medial posterior BNST inactivation blocks heroin and cue-primed reinstatement (Rogers et al., 2008). These findings support a role for the BNST in cue-induced drug seeking and suggest that the involvement of distinct subdivisions may vary by drug of abuse.

As illustrated by the above studies, a broad range of work has identified the BNST as an important candidate neural structure involved in relapse. However, the majority of this work has examined cue-induced seeking of cocaine and heroin. Therefore, it is not known whether these findings extend to other drugs such as ethanol. Previously, our lab identified the BNST as one of several areas activated by presentation of an ethanol-associated cue (Hill et al., 2007). Beyond this, little evidence exists to indicate that the BNST is involved in cue-induced ethanol-seeking behavior. Hence, our goal was to directly examine this region in the context of cue-induced ethanol seeking using an ethanol-induced CPP procedure that has been well-established by our laboratory (Cunningham et al., 2006).

To evaluate the BNST in ethanol seeking, we used electrolytic lesions, pharmacological inactivation, and chemogenetic inhibition. Given the limitations inherent to each of these intracranial manipulations, we sought to increase the generality of our conclusions by incorporating all three techniques. These manipulations were intended to inhibit BNST activity during ethanol CPP expression. Based on the existing literature, we reasoned that inhibiting the BNST by each of these techniques would disrupt ethanol place preference expression.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

Adult male DBA/2J mice (n = 214) were purchased from Jackson Laboratory (Sacramento, CA) at 6–7 weeks of age. Mice were housed 2–4 per cage in a colony room maintained at 21+/−1°C on a 12:12 light-dark cycle with lights on at 07:00 am. Food and water were available ad libitum in home cages throughout the experiment. Surgeries were performed on mice 6–11 weeks of age. All procedures were carried out in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide For the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH Publications No. 8023, revised 2011) and were approved by the Oregon Health & Science University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

2.2. Drugs

Ethanol (95%) was prepared 20% v/v in a solution of 0.9% saline and administered intraperitoneally (IP) at a dose of 2 g/kg in a 12.5 mL/kg volume.

In exp. 2, the BNST was transiently inactivated using a cocktail of the GABAA and GABAB receptor agonists muscimol and baclofen (M+B; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Muscimol (0.1 mM) and baclofen (1.0 mM) were dissolved in 0.9% saline and administered bilaterally (100 nL/side) into the BNST. Inactivation of the BNST with these concentrations has previously been shown to reduce cue-induced cocaine and heroin seeking (Buffalari and See, 2011; Rogers et al., 2008). Infusions were delivered over 60 s and injectors were left in place for an additional 30 s to allow for complete diffusion of drug from the injectors.

In exps. 3, 4, and 5, clozapine-N-oxide (CNO; Tocris Bioscience, Ellisville, MO) was dissolved in 0.9% saline and administered at 10 or 20 mg/kg (10 mL/kg, IP) 30 min before the CPP test. These doses were selected based on the following considerations. First, compared to Gq-coupled (hM3Dq) DREADDs, which are very effective at eliciting neuronal firing, Gi-coupled (hM4Di) DREADDs are reportedly less effective at inhibiting activity and may therefore require higher CNO doses (Farrell and Roth, 2013). Moreover, these doses were based on previously published studies showing that CNO alone produced no physiological or behavioral response in rodents at doses of 10 mg/kg and above (Li et al., 2013; Mahler et al., 2014; Ray et al., 2011, 2013; Vazey and Aston-Jones, 2014). Finally, a maximum dose of 20 mg/kg was specifically chosen for a control experiment as it was, to our knowledge, the highest reported in the literature (Mahler et al., 2014).

2.3. Stereotaxic surgery

2.3.1. General procedure

In exps. 1–4, mice were anesthetized with isoflurane (1–4% in O2) and placed in a stereotaxic apparatus (Model No. 1900; Kopf Instruments, Tujunga, CA). Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, meloxicam (0.2 mg/kg) or carprofen (0.1 mg/kg) were injected subcutaneously (in 10 mL/kg) immediately before and 24 h after surgery to minimize postoperative discomfort. Coordinates targeting the BNST (from bregma: AP +0.14, L ±0.8, DV −4.25) were used in exps. 1A, 1B and 2 based on a standard mouse brain atlas (Paxinos and Franklin, 2001). In exps. 3 and 4, the lateral ventricles were avoided during virus infusions by approaching the BNST at a 20° angle. Burr holes were drilled laterally ±2.3 mm from bregma (AP +0.26) and injectors were lowered 4.33 mm from the top of the skull. These values were derived from the atlas-based coordinates: AP +0.26, ML ±0.8, DV −4.07.

2.3.2. Electrolytic lesions

In exps. 1A and 1B, electrodes (Rhodes Medical Instruments, Woodland Hills, CA) were lowered bilaterally into the BNST to administer electrolytic (0.5 mA for 10 s) or sham (no current) lesions (Model 3500; Ugo Basile, Varese, Italy). Due to reduced body weights in the BNST lesioned group, mice were given 8–13 days of recovery before the start of conditioning (exp. 1A) or the CPP test (exp. 1B). This recovery period ensured weights between lesioned and sham mice were comparable.

2.3.3. Cannulations

In exp. 2, bilateral cannulae (10 mm, 25 ga) were implanted 2.0 mm above the BNST and held in place with carboxylate cement (Durelon™, 3M, St. Paul, MN) anchored to the skull with stainless steel screws. To maintain patency, stainless-steel obturators (10 mm, 32 ga) were placed inside cannula. Mice were given 3–7 days of recovery before habituation.

2.3.4. AAV vector infusions

To silence BNST neurons, we also used a chemogenetic technique involving designer receptors exclusively activated by designer drugs (DREADD; Armbruster et al., 2007). AAV5-hSyn-HA-hM4D(Gi)-IRES-mCitrine (3.9 × 1012 virus molecules per mL) was purchased from the University of North Carolina Vector Core (Chapel Hill, NC). Virus was stereotaxically infused using injectors made of 32-ga stainless steel tubing encased by 26-ga stainless steel. Injectors were attached via polyethylene tubing (PE-20) to 1 μl Hamilton syringes. Infusions of 150 nL/side were delivered by syringe pump (Model PHD 22/2000; Harvard Apparatus, Plymouth Meeting, PA) at a rate of 15 nL/min. To ensure complete diffusion of virus and minimize tracking upon removal, injectors were left in place for 5 min after infusions. Approximately 4–6 weeks were allowed for transgene expression and animal recovery

2.4. Histology

2.4.1. Placement verification – Exps. 1A, 1B and 2

Lesion (exps. 1A and 1B) and injection (exp. 2) sites were determined through histological analysis. Brain tissue was collected within 24 h of the CPP test and immersed in 2% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 24 h then cryoprotected in 20% sucrose in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), followed by 30% sucrose/PBS. Using a cryostat, coronal sections (40 μm) were taken from the rostral to caudal end of the BNST (from +0.62 to −0.46 mm from bregma) then stained with 0.1% thionin.

2.4.2. Immunohistochemistry – Exps. 3 and 4

In exps. 3 and 4, brains were immersed in 4% PFA/PBS overnight following extraction then cryoprotected as described above. Coronal sections (30 μm) were sliced on a cryostat and stored in a solution of 0.1% NaN3/PBS at 4°C until immunohistochemical analysis.

In exp. 3, mice were deeply anesthetized with CO2 and transcardially perfused with ice cold 4% PFA/PBS, 24–48 h after the CPP test. Free-floating sections were processed for immunofluorescence to detect the HA-tagged hM4Di protein. Briefly, sections were washed in PBS and permeabilized with 0.4% Triton X-100/PBS for 1 h, then blocked with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA)/5% normal goat serum (NGS)/0.4% Triton X-100/PBS for 1 h. Sections were incubated overnight with gentle agitation at 4°C in 1% BSA/5% NGS/0.4% Triton X-100/PBS containing a rabbit monoclonal antibody against HA (1:500; Cell Signaling). Next, sections were rinsed in PBS and incubated for 2 h in Alexa Fluor 555 labeled goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:300; Invitrogen). After final washes, sections were rinsed in PBS, mounted on gelatinized slides, and coverslipped using ProLong Gold Antifade mountant with DAPI (Life Technologies). Images were captured with a Leica DM4000 B microscope and cropped and contrast adjusted using Fiji software (NIH).

In exp. 4, mice were sacrificed via CO2 and brains were collected 90 min after CS+ re-exposure. Tissue was later processed for c-Fos immunoreactivity (IR) as an indicator of neuronal activity. Sections were washed in tris-buffered saline (TBS) then immersed in freshly prepared sodium borohydride (NaBH4, 1% w/v in TBS) for 30 min to reduce fixative-induced autofluorescence (Beisker et al., 1987; Kobelt et al., 2004; Tagliaferro et al., 1997). Several washes fully removed NaBH4 before the tissue was blocked with 1% BSA/5% NGS/0.3% Triton X-100/TBS for 45 min. Next, sections were incubated overnight in block containing a rabbit polyclonal primary antibody directed against c-Fos (1:2000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Sections were then rinsed, blocked as above, and incubated for 2 h in a biotinylated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (1:1000; Vector Laboratories) followed by 2 h incubation in Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated streptavidin (0.5 μg/mL; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) for immunofluorescent detection. Tissue was mounted and images captured as in exp. 3. Total c-Fos positive nuclei were manually counted across dorsal and ventral BNST in 2–4 serial sections from mice selected at random from each treatment group (CNO, n = 3; Vehicle, n = 3). Counts were then averaged across subdivisions in each animal and treatment group means were compared using an unpaired two-tailed t-test.

2.5. Apparatus

Twelve identical acrylic and aluminum chambers (30 × 15 × 15 cm) each enclosed in light- and sound-attenuating ventilated boxes (Coulbourn Instruments Model E10–20) were used to record locomotor activity and amount of time spent on each side of the chamber. Activity and grid time were detected by six sets of infrared photodetectors mounted at 5 cm intervals, 2.2 cm above the floor along the front and rear sides of each inner chamber and recorded by computer (detailed fully in Cunningham et al., 2006).

Chamber floors were composed of grid (2.3-mm stainless steel rods mounted 6.4 mm apart in an acrylic frame) or hole (16-ga stainless steel sheets perforated with 6.4 mm diameter holes on 9.5 mm staggered centers) interchangeable halves that are equally preferred by experimentally naïve DBA/2J mice (Cunningham et al., 2003). Although these stimuli are preferred equally prior to conditioning, they may vary in relative salience or conditionability (Cunningham et al., 2003). Thus, experimentally induced changes in preference for these stimuli by conditioning and other manipulations may not always be symmetrical.

In the one-compartment configuration (exps. 1A, 1B and 2), the same floor cue was placed on both sides of the conditioning box (i.e., grid vs. grid, hole vs. hole) during conditioning trials, giving the mouse free access to both sides of the box. In the two-compartment configuration (exps. 3, 4, and 5), grid and hole floors were separated during conditioning by a clear acrylic divider placed in the center of the apparatus. Previous research in our lab shows no difference in the magnitude of ethanol-induced CPP produced by these configurations in DBA/2J mice trained in the dark (Cunningham and Zerizef, 2014). Moreover, given the variation in CPP procedures across laboratories, our inclusion of two common configurations allows for greater generality of our conclusions.

2.6. Experimental Design

2.6.1. General Procedure

In each experiment, mice were randomly assigned to the following treatment groups: lesion or sham (exps. 1A and 1B); M+B or vehicle (exp. 2); CNO or vehicle (exps. 3, 4, and 5). We used an unbiased place preference procedure that involved three distinct phases: habituation/pre-test (one session), conditioning (2–4 sessions) and preference test (1–2 sessions). Illustration of procedures and timelines for each experiment are included in figures 1a–5a.

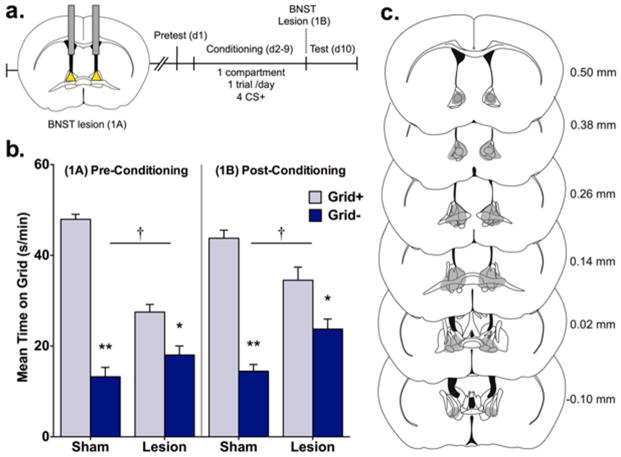

Figure 1.

Electrolytic BNST lesions disrupt ethanol CPP expression. (a) Procedural timeline illustrating electrolytic BNST lesions made before (exp. 1A) or after (exp. 1B) mice underwent a CPP procedure involving a pretest and 1-compartment, 1 trial/day conditioning procedure where ethanol was paired with a distinct tactile cue (grid or hole floor) every other day for a total of 4 CS+ trials. Preference was measured during a test where mice were allowed equal access to both floor cues. (b) Data are mean time on the grid floor (s/min + SEM) for sham and lesion groups. BNST lesions made before (1A, left panel) and after (1B, right panel) conditioning disrupted ethanol CPP expression. Compared to shams, lesions reduced CPP magnitude as indicated by treatment (sham vs. lesion) by conditioning (Grid+ vs. Grid−) interactions and significant differences between Grid+ and Grid− in sham and lesion treatment groups; † p < 0.001 treatment x conditioning; *p = 0.003, **p < 0.001 between Grid+ and Grid− (n = 6–10/subgroup). (c) Maximal extent of pre- and post-conditioning lesions is shown in grey. Numbers indicate distance from bregma (in mm) for each coronal section.

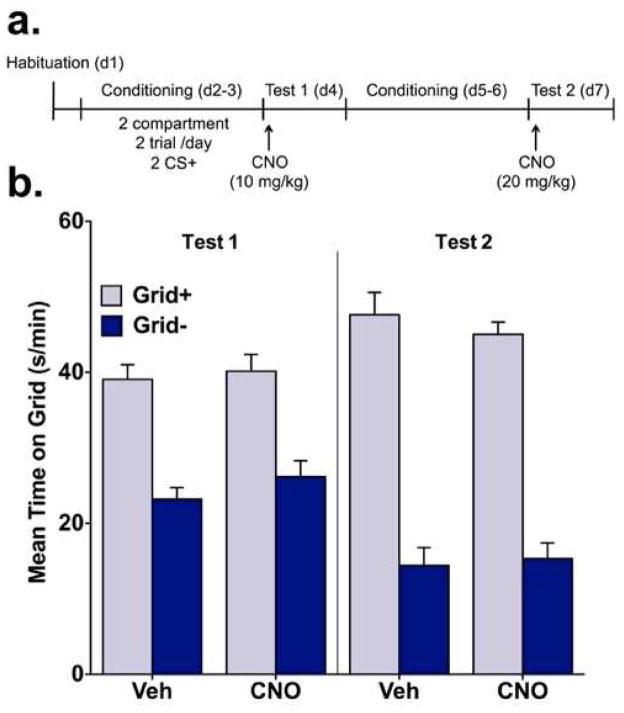

Figure 5.

CNO alone does not affect ethanol CPP expression. (a) In experiment 5, mice were habituated to the CPP apparatus before conditioning using a 2-compartment, 2 trial/day procedure where ethanol was paired with a distinct tactile cue (grid or hole floor). After 2 CS+ trials, mice were administered vehicle or CNO (10 mg/kg) before a preference test (Test 1). Mice then received an additional 2 CS+ (4 total) trials before a second preference test (Test 2), prior to which vehicle or CNO (20 mg/kg) were administered. (b) In the absence of hM4Di, CNO did not disrupt preference expression. Place preference magnitude did not differ between vehicle and CNO groups on either Test 1 or Test 2.

2.6.2. Habituation

In exps. 2–4, animals underwent a 5-min habituation session where they were given an injection of saline and placed in the apparatus on a white paper floor. This phase was intended to reduce the novelty and potential stress associated with the CPP procedure.

2.6.3. Pretest

A 30-min pretest was included in exp. 1A to examine whether BNST lesions or surgical procedures affected initial bias for the tactile cues. We also included a pretest in exp. 1B to equate mice in both lesion studies for overall cue exposure. The pretest was procedurally identical to the place preference test (described below). In neither experiment were there significant group differences in initial preference, floor bias, or activity (data not shown). The overall mean percentages (± SEM) of the pretest session spent on the grid floor were 52.8 ± 2.0 and 50.2 ± 2.0 in exps. 1A and 1B, respectively.

2.6.4. Conditioning

Within each treatment group, mice were randomly assigned to one of two conditioning subgroups (Grid+ or Grid−). Mice in the Grid+ subgroup received ethanol paired with the grid floor (CS+) and saline paired with the hole floor (CS−), whereas mice in the Grid− subgroup received ethanol paired with the hole floor (CS+) and saline paired with the grid floor (CS−). Each mouse received two or four 5-min conditioning trials before the preference test.

2.6.5. Place preference test

A choice preference test was performed after the last conditioning session. Mice in all experiments were simultaneously exposed to the grid and hole floors for 30 min immediately after a saline injection. The position of each floor type was counterbalanced (i.e., left vs. right) within conditioning subgroups.

2.6.6. Exps. 1A and 1B – Effect of electrolytic lesions of the BNST on ethanol CPP

Exps. 1A (n = 32) and 1B (n = 35) used electrolytic lesions to determine involvement of the BNST in ethanol CPP expression (fig. 1a). In exp. 1A, lesions were made prior to the start of conditioning procedures. Since lesions made before conditioning cannot indicate whether disruptions in CPP occurred during the acquisition or expression phase, we conducted a follow up experiment to test effects of BNST lesions induced after conditioning (exp. 1B). Thus, exp. 1A tested whether the BNST was involved in either CPP acquisition or expression, whereas exp. 1B tested only whether the BNST was involved in ethanol CPP expression. Animals received one conditioning trial per day (CS+ or CS−) over 8 days and the order of exposure was counterbalanced between animals within each conditioning subgroup (Grid+ vs. Grid−).

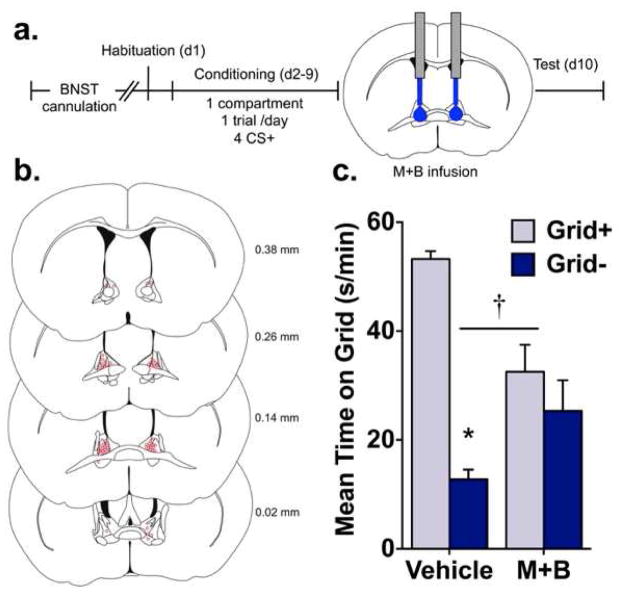

2.6.7. Exp. 2 – Effect of pharmacological inactivation of the BNST on ethanol CPP

Experiment 2 (n = 30) examined the effect of temporary inactivation of the BNST on ethanol-induced CPP using focal infusions of M+B. As in exps. 1A and 1B, a one-trial per day procedure was used (fig. 2a).

Figure 2.

Pharmacological inactivation of the BNST blocks ethanol CPP expression. (a) In experiment 2, guide cannulae were implanted before the start of the CPP procedure. Mice were habituated to the CPP apparatus then conditioned using a 1-compartment, 1 trial/day procedure where ethanol was paired with a distinct tactile cue (grid or hole floor) every other day for a total of 4 CS+ trials. Immediately before the CPP test, mice received intra-BNST infusions of vehicle or muscimol + baclofen (M+B). (b) Reconstruction of injector placements for all mice included in Experiment 2. Numbers indicate distance from bregma (in mm) for each coronal section. (c) Data are mean time on the grid floor (s/min + SEM) for vehicle and M+B groups. Infusion of M+B blocked the expression of ethanol CPP. This was supported by a treatment (vehicle vs. M+B) by conditioning (Grid+ vs. Grid−) interaction and a significant difference between Grid+ and Grid− in the vehicle group only; † p < 0.001 treatment x conditioning; *p < 0.001 between Grid+ and Grid− (n = 7–8/subgroup).

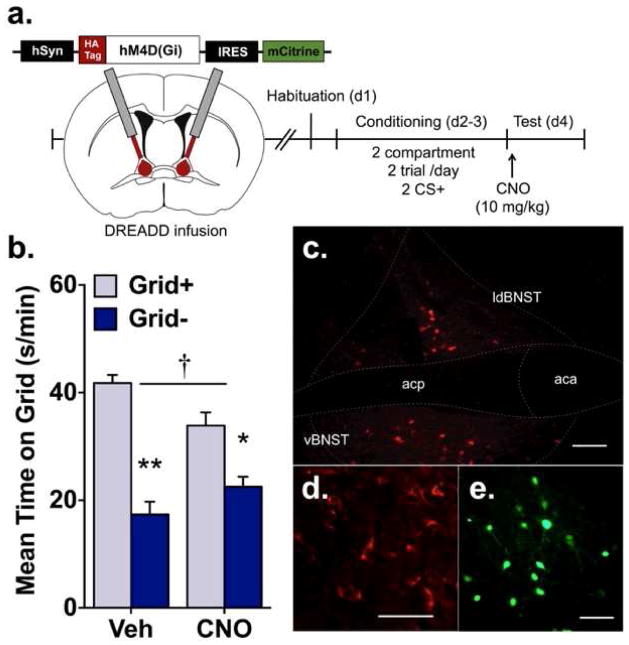

2.6.8. Exp. 3 – Effect of chemogenetic inactivation of the BNST on ethanol CPP

In experiment 3 (n = 45), the effect of chemogenetic inhibition of the BNST on ethanol CPP expression was evaluated (fig. 3a). During conditioning, mice received two trials per day, with CS− (saline) trials in the morning (10 am – 12 pm) and CS+ (ethanol) trials in the afternoon (2 – 4 pm). Unpublished research in our lab has shown development of similar ethanol-induced CPP using either one- or two-trial per day procedures. Conditioning occurred over a 2-day period for a total of 2 CS− and 2 CS+ trials. Mice expressing hM4Di were injected with CNO (10 mg/kg) or vehicle 30 min before place preference testing. Several studies have shown that vehicle-treated rodents expressing DREADDs do not differ from CNO-treated controls expressing only a GFP transgene (Ferguson et al., 2011; Ferguson et al., 2013). Therefore, in exp. 3 vehicle-treated mice expressing the hM4Di construct served as our control.

Figure 3.

Chemogenetic inhibition of the BNST disrupts ethanol CPP expression. (a) In experiment 3, the hSyn-HA-hM4D(Gi)-IRES-mCitrine adeno-associated virus (AAV; serotype 5) was used to express hM4Di under a neuronal-specific human synapsin promoter (hSyn). Using an angled approach, virus was delivered into the BNST before habituation. The CPP procedure consisted of a 2-compartment, 2 trial/day procedure where ethanol was paired with a distinct tactile cue (grid or hole floor) each day for a total of 2 CS+ trials before CPP testing. To stimulate hM4Di, CNO (10 mg/kg) was administered before the CPP test. HA, influenza hemagglutinin epitope tag; IRES, internal ribosome entry site. (b) Mean time on the grid floor (s/min + SEM) after 2 trials for vehicle and CNO groups. The magnitude of CPP was reduced in the CNO group as indicated by a treatment (vehicle vs. CNO) by conditioning subgroup (Grid+ vs. Grid−) interaction and significant differences between Grid+ and Grid− in both treatment groups. † p = 0.003 treatment x conditioning; *p < 0.01, **p < 0.001 between Grid+ and Grid− (n = 12/subgroup). (c-e) Localized hM4Di expression in BNST. (c) Representative staining for HA-tagged hM4Di within dorsal and ventral BNST at 10X magnification. (d) Expression of HA-tagged hM4Di on neuronal membranes and processes (20X). (e) Native mCitrine fluorescence showing neurons transduced by AAV vector (20X). Scale bars, 100 μm; aca, anterior commissure, anterior; acp, anterior commissure, posterior; ldBNST, lateral-dorsal BNST; vBNST, ventral BNST.

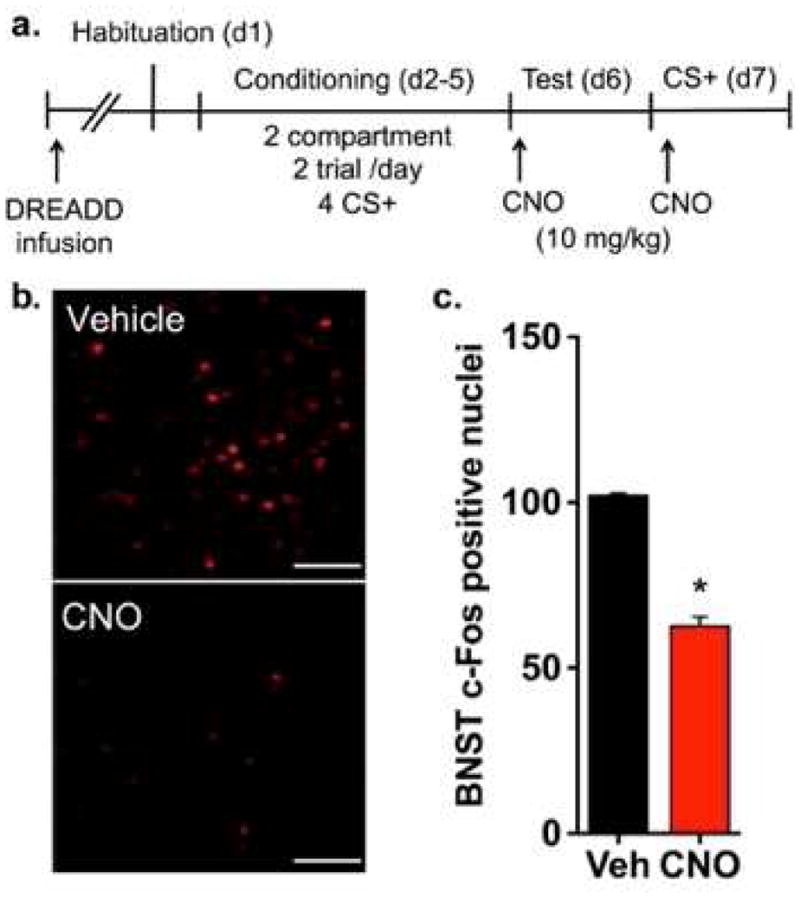

2.6.9. Exp. 4 – Effect of hM4Di activation on c-Fos IR in the BNST

In exp. 4 (n = 24), we determined whether CNO would attenuate BNST activity in mice expressing the hM4Di construct (fig. 4a) as indexed by c-Fos IR after brief exposure to the CS+. Procedures were identical to those described in exp. 3, except that mice received: 1) a total of 4 CS− and 4 CS+ trials, 2) an abbreviated 15 min CPP test, and 3) a 5-min re-exposure to the ethanol-associated floor cue (CS+) 24 h after the CPP test. A shorter CPP test duration was used to reduce any potential impact on CS−US associative strength since each CS+ presentation without the US serves as an extinction trial (Bouton and Moody, 2004). Additional conditioning trials were given in this experiment to offset any extinction effects and to elicit more robust activity and c-Fos IR in the BNST upon CS+ re-exposure. As in exp. 3, CNO was administered 30 min before the CPP test and CS+ re-exposure.

Figure 4.

Activation of hM4Di reduces cue-induced activity in BNST. (a) In experiment 4, angled bilateral infusions of virus carrying hM4Di were delivered into the BNST before habituation. The CPP procedure consisted of a 2-compartment, 2 trial/day procedure where ethanol was paired with a distinct tactile cue (grid or hole floor) each day for a total of 4 CS+ trials before CPP testing. To stimulate hM4Di, CNO (10 mg/kg) was administered before an abbreviated CPP test. The following day, mice were briefly re-exposed to the ethanol-associated cue (CS+) before tissue was harvested for analysis of c-Fos immunoreactivity. (b) Representative c-Fos immunofluorescence in ventral BNST in hM4Di-expressing mice administered vehicle or CNO before CS+ re-exposure. Scale bars, 100 μm. (c) CNO-mediated stimulation of hM4Di significantly reduced the number of c-Fos positive nuclei in BNST compared to vehicle. n = 3/treatment group; *p < 0.001

2.6.10. Exp. 5 – Effect of CNO alone on ethanol CPP

Experiment 5 (n = 48) was performed to determine whether CNO itself would affect ethanol CPP expression in the absence of hM4Di (fig. 5a). In exp. 3, we controlled for possible nonspecific effects of transgene expression (i.e., hM4Di) on behavior by including vehicle-treated hM4Di mice. Here we tested CNO using wild-type mice as controls, since we did not expect them to differ in behavior from mice expressing a control reporter (e.g., GFP). Hence, procedures were identical to those described in exp. 3, with the following exceptions: 1) mice were not infused with virus and therefore did not express hM4Di, 2) after the first test, mice received 2 additional conditioning sessions for a total of 4 CS− and 4 CS+ trials, and 3) mice were given a final test after injection of a higher CNO dose (20 mg/kg).

2.7. Statistical analysis

2.7.1. Preference tests

Preference was defined as a significant difference in time spent on the grid floor between Grid+ and Grid− conditioning subgroups (Cunningham et al., 2003b; Cunningham et al., 2006). Preference data were analyzed by 2-way ANOVA (treatment x conditioning), where treatment refers to the main treatment groups (e.g., sham vs. lesion in exps. 1A and 1B) and conditioning refers to the assigned conditioning subgroup (Grid+ vs. Grid−). Additional analyses were used to assess the impact of experimental manipulations on CPP expression across test time. To simplify presentation and interpretation of the time course data, preference was expressed as percent time spent on the ethanol-paired floor (CS+) by collapsing across conditioning subgroups (Grid+ and Grid−). Preference data were then averaged across 5-min intervals and analyzed by two-way mixed-factorial ANOVA (treatment x interval). Activity during the preference test was analyzed by one-way ANOVA (treatment).

2.7.2. Conditioning activity

Activity data from conditioning sessions were collapsed across trials of each type (CS+ and CS−) and analyzed by two-way mixed-factorial ANOVA (treatment x trial type), where trial type refers to CS+ vs. CS− trials.

3. Results

3.1. Place preference tests

3.1.1. Exps. 1A and 1B – Effect of electrolytic lesions of the BNST on ethanol CPP

Figure 1c shows the maximum extent of lesion damage to the BNST in exps. 1A and 1B. In exp. 1A, four mice were excluded from analyses because lesions were made outside the BNST inclusion area. One mouse was excluded from analysis in exp. 1B due to a procedural error.

As shown in figure 1b, BNST lesions interfered with ethanol-induced CPP. This effect was observed whether lesions occurred before (exp. 1A) or after conditioning (exp. 1B) and was supported by significant treatment (lesion vs. sham) x conditioning (Grid+ vs. Grid−) interactions (Exp. 1A, [F(1,28) = 50.8, p < 0.001]); Exp. 1B, [F(1,31) = 18.0, p < 0.001]. ANOVA also revealed significant main effects of conditioning in both studies (Exp. 1A, [F(1,28) = 50.8, p < 0.001]; Exp. 1B, [F(1,31) = 18.0, p < 0.001]) and a significant main effect of treatment in exp. 1A [F(1,28) = 19.5, p < 0.001], but not in exp. 1B. Pairwise comparisons between conditioning subgroups within each treatment condition showed that all groups expressed a significant CPP (Bonferroni corrected p’s ≤ 0.003) in both experiments. These findings indicate that BNST lesions before or after conditioning reduced, but did not completely block expression of ethanol CPP.

Analysis of preference across time during the test showed that CPP was immediately reduced in lesioned mice compared to shams in both experiments (fig. S1). In exp. 1A, a significant treatment x time interaction [F(5,145) = 3.2, p = 0.009] and main effect of treatment [F(1,29) = 23.3, p < 0.001] were found. Follow-up pairwise comparisons revealed significant differences between groups at all 5-min test intervals (p’s ≤ 0.044). In exp. 1B, analyses yielded significant main effects of treatment [F(1,33) = 19.0, p < 0.001] and time [F(5,165) = 3.4, p < 0.001], but no treatment x time interaction. These results indicate that pre- and post-conditioning lesions disrupt preference expression in a relatively consistent manner across the CPP test.

3.1.2. Exp. 2 – Effect of pharmacological inactivation of the BNST on ethanol CPP

Figure 2b illustrates microinfusion injector placements within the BNST. In exp. 2, mice were excluded from analyses for receiving microinfusions outside of the BNST (n = 2), procedural error (n = 1), lost headmount (n = 1), and histological error (n = 1).

Temporary pharmacological inactivation of the BNST (via microinjection of M+B) blocked expression of ethanol CPP (fig. 2c). This was confirmed by a significant treatment (M+B vs. vehicle) x conditioning (Grid+ vs. Grid−) interaction [F(1,26) = 16.0, p < 0.001]. A main effect of conditioning [F(1,26) = 32.8, p < 0.001], but not treatment, was found. Post hoc analysis of the interaction showed that only mice infused with vehicle expressed significant CPP (Bonferroni-corrected p < 0.001), suggesting that activation of the BNST was required for expression of CPP. In addition, mice infused with M+B spent consistently less time than vehicle on the ethanol-paired floor across test intervals (fig. S2). This was supported by a main effect of treatment [F(1,28) = 16.5, p < 0.001] but not time and the absence of a treatment x time interaction.

3.1.3. Exp. 3 – Effect of chemogenetic inactivation of the BNST on ethanol CPP

Localized expression of hM4Di in BNST was observed 4–6 weeks after infusion of the viral construct, as determined by expression of the hM4Di-fused HA tag (fig. 3c-d) and mCitrine tag (fig. 3e). As shown in figure 3b, activation of hM4Di in the BNST reduced ethanol CPP expression in the CNO-treatment group compared to the vehicle treatment group. When collapsed across conditioning subgroups (Grid+ and Grid−) and analyzed over time (fig. S3), preference for the ethanol-paired floor was significantly lower in CNO-treated compared to vehicle-treated animals as indicated by a significant treatment x time interaction [F(5,220) = 3.0, p = 0.012] and main effect of treatment [F(1,44) = 7529.4, p = 0.004]. Follow-up analyses revealed significant differences between treatment groups at minutes 11–15, 16–20 and 21–25 (p’s ≤ 0.024). Overall, these results indicate that hM4Di-induced inactivation of BNST neurons reduced the magnitude of ethanol CPP compared to the control. This effect was delayed, as disruptions in preference expression were not significant before 10 min into the CPP test.

3.1.4. Exp. 4 –Effect of hM4Di activation on c-Fos IR in the BNST

Representative images in figure 4b demonstrate the extent of c-Fos IR in the vBNST of hM4Di expressing animals treated with CNO or vehicle. Within the BNST, CS+-induced neural activity was significantly lower in CNO-treated compared to vehicle-treated mice (fig. 4c). Mean (± SEM) c-Fos positive nuclei were 62.6 ± 2.9 for CNO and 102.1 ± 0.7 for vehicle. Analysis of these data yielded a significant effect of treatment on total c-Fos cells in the BNST [t(4) = 13.5, p < 0.001], indicating that CNO reduced c-Fos IR.

Given the abbreviated length (15 min) of the CPP test in this experiment, we were not able to detect a significant effect of CNO on preference expression (fig. S4). This finding is similar to that of exp. 3, as hM4Di activation had only a marginal effect on preference during the first 15 min the CPP test (fig. S3). These findings were supported by analyses of grid time that showed a main effect of conditioning [F(1,20) = 145.4, p <0.001] but not treatment or a treatment x conditioning interaction (p = 0.08). When percent time spent on the ethanol-paired floor was analyzed over 5-min intervals, neither a treatment x time interaction nor main effect of time was found. Findings also revealed a trend toward a main effect of group (p = 0.070) similar to that found in first 15 min of exp. 3 (p = 0.065). However, comparisons between these experiments must be made conservatively, as mice received a greater number of CS+ trials in exp. 4.

3.1.5. Exp. 5 – Effect of CNO alone on ethanol CPP

In the absence of hM4Di expression, CNO at 10- and 20-mg/kg doses did not affect ethanol CPP expression (fig. 5b). This was indicated on tests 1 and 2 by a main effect of conditioning [p’s < 0.001], lack of a significant treatment (CNO vs. vehicle) x conditioning subgroup (Grid+ vs. Grid−) interaction and no main effect of treatment. When analyzed across test intervals (fig. S5), percent time spent on the ethanol-paired floor was consistent between treatment groups as indicated by the absence of significant treatment x time interactions and main effects of treatment on tests 1 and 2 (p’s > 0.3). A main effect of time was found on test 2 [F(5,230) = 2.859, p = 0.016] after mice received total of 4 CS+ trials but not on test 1 after 2 CS+ trials.

3.2. Locomotor activity

3.2.1. Preference tests

In exps. 1A, 1B, 3, 4, and 5 there was no significant difference in test activity between treatment groups (Table 1). This was confirmed by the absence of a main effect of treatment in each experiment [F’s < 1]. In exp. 2, test session activity was reduced by infusion of M+B as compared to vehicle [F(1,28) = 10.7, p = 0.003]. However, this reduction in test activity is unlikely to have interfered with preference, as lower test activity is generally associated with enhanced CPP expression (Gremel and Cunningham, 2007).

Table 1.

Mean Activity Counts per Minute (± SEM) during conditioning and preference test

| Group | CS+ Trials | CS− Trials | Preference Test | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experiment 1A | ||||

| Electrolytic Lesion | Sham | 176.1 ± 8.8 | 57.9 ± 3.1 | 35.5 ± 2.3 |

| Pre-Conditioning | Lesion | 128.5 ± 12.0a | 67.8 ± 2.7b | 40.1 ± 1.9 |

| Experiment 1B | ||||

| Electrolytic Lesion | Sham | 203.5 ± 7.9 | 62.0 ± 3.3 | 39.5 ± 1.8 |

| Post-Conditioning | Lesion | 206.5 ± 6.8 | 61.4 ± 3.0 | 44.5 ± 2.3 |

| Experiment 2 | ||||

| Pharmacological Inactivation | Vehicle | 223.8 ± 12.6 | 73.7 ± 3.6 | 36.7 ± 3.8 |

| M+B | 220.7 ± 8.4 | 73.1 ± 3.0 | 22.5 ± 2.3a | |

| Experiment 3 | ||||

| hM4Di | Vehicle | 120.8 ± 4.8 | 44.2 ± 1.4 | 40.2 ± 1.3 |

| CNO | 124.1 ± 5.3 | 46.5 ± 2.0 | 40.3 ± 1.4 | |

| Experiment 4 | ||||

| c-Fos Control | Vehicle | 134.5 ± 4.3 | 40.1 ± 2.4 | 45.4 ± 2.4 |

| CNO | 136.1 ± 4.8 | 40.3 ± 2.0 | 42.1 ± 2.8 | |

| Experiment 5 | Trials 1–2 | Test 1 | ||

| CNO Control | Vehicle | 120.4 ± 3.5 | 43.4 ± 1.8 | 38.7 ± 1.1 |

| CNO | 117.5 ± 4.4 | 42.4 ± 1.6 | 38.5 ± 1.3 | |

| Trials 3–4 | Test 2 | |||

| Vehicle | 120.6 ± 4.3 | 37.2 ± 2.2 | 31.9 ± 1.5 | |

| CNO | 123.2 ± 6.3 | 35.2 ± 1.7 | 31.6 ± 1.1 | |

differs from sham or vehicle, p = 0.003

differs from sham, p < 0.03

3.2.2. Conditioning Activity

With the exception of exp. 1A, CS+ trial activity was influenced only by the presence of ethanol as no treatment manipulation occurred until the test day. As expected with DBA/2J mice (Cunningham et al., 1992), activity during CS+ trials was higher than on CS− trials (Table 1). Analyses confirmed that activity was significantly higher on CS+ trials compared to CS− trials in all experiments, as indicated by a significant main effect of trial type [p’s < 0.001] and no treatment x trial type interaction. In exp. 1A, BNST lesions reduced locomotor activity during CS+ trials and increased activity during CS− trials. This effect was confirmed by a treatment x trial type interaction [F(1,30) = 16.3, p < 0.001] and main effects of treatment on CS+ [F(1,30) = 10.6, p = 0.003] and CS− trials [F(1,30) = 5.3, p = 0.029].

In exps. 3–5, locomotor activity was generally lower on conditioning trials than in the other experiments (Table 1). This reflects our use of a 2-compartment configuration in exps. 3–5, which confines mice to one side of the apparatus during conditioning and therefore provides less space for movement (Hitchcock et al., 2014). Treatment groups in exps. 3–5 however, showed similar levels of ethanol-induced activation, as confirmed by a lack of a main effect of treatment and a significant main effect of trial type [p’s < 0.001].

4. Discussion

The present studies used several techniques to directly test the involvement of the BNST in ethanol-seeking behavior. In experiment 1, electrolytic ablation of the BNST before (exp. 1A) and after (exp. 1B) conditioning reduced the magnitude of ethanol seeking. In experiment 2, CPP expression was blocked and activity reduced by focal infusion of the GABA receptor agonists muscimol and baclofen. In experiments 3 and 4, activation of hM4Di by CNO reduced CPP magnitude and c-Fos IR, respectively. A control study (exp. 5) revealed that the reduction in CPP expression was not due to administration of CNO alone, as equal and higher doses of CNO did not impact CPP in the absence of hM4Di.

The time course and extent of CPP disruption observed in these experiments varied across the techniques and procedures used. Preference expression was lower from the beginning of each test after lesions or temporary inactivation (M+B), but this effect was delayed after hM4Di activation. On the basis of our data, we cannot determine why a delayed effect was found in the DREADD experiments. One possible explanation relates to the pharmacokinetic properties of CNO. Given its systemic route of delivery, CNO would not be expected to act as rapidly to inhibit neuronal activity as locally administered drugs like M+B or lesions. In vivo experiments in mice have shown that plasma levels of CNO after IP injection peak within 15 min and clear after 2 h (Wess et al., 2013). However, CNO can produce protracted physiological effects in DREADD-expressing mice, sometimes persisting as long as 8–10 h (Alexander et al., 2009; Guettier et al., 2009). Notably, Alexander and colleagues (2009) demonstrated that neural activity in hM3Dq mice peaked around 45–50 min after CNO injection, an effect that was independent of dose. Assuming a similarly timed peak in suppression of neural activity in hM4Di mice, our findings are in agreement, showing reductions in preference expression 45 min after CNO was administered. Thus, administration of CNO 45–50 min before testing in future studies might show a more immediate reduction in preference, similar to that seen in the lesion and inactivation studies.

Whereas place preference was attenuated by BNST lesions and hM4Di activation (exps. 1A, 1B, and 3), it was altogether abolished by M+B infusion (exp. 2). There are several potential explanations for this finding. First, it is possible that the M+B infusion diffused over a broader portion of the BNST, providing greater overall inhibition of this structure. It is also possible that some volume spread to sites adjacent to the BNST and/or throughout the brain as injectors were lowered through the lateral ventricles. Though not a concern for electrolytic lesions, the potential spread into ventricles given the location of the BNST, prompted our use of an angled approach when administering viral infusions in exps. 3 and 4. This use of differing approaches to target the BNST further expands the breadth of our conclusions. However, it is possible that intraventricular diffusion of M+B may have produced more widespread central inhibition. These explanations are supported by the reduction in locomotor activity that was observed after M+B administration. In addition, this demonstrates a major disadvantage to microinfusion, namely the extent of drug diffusion. In addition, administering focal microinfusions to awake behaving mice is challenging given the additional handling required. It is plausible that exposure to this handling, which involved light restraint, may have served as a stressor and interfered with preference expression. However, results from our vehicle control group would argue against this explanation. Finally, it is also possible that activating GABAA and GABAB receptors using M+B was simply a more effective strategy to inhibit neuronal firing in the BNST.

In interpreting these findings, it is also important to consider the advantages and disadvantages associated with lesions and DREADDs. For example, one major advantage to electrolytic lesions is that they are technically less challenging and can be rapidly administered. Lesions also do not require any additional maintenance or manipulation once they have been administered. This is advantageous from a behavioral perspective, as it removes the possibility of pre-task handling interfering with performance. However, unlike DREADDs and M+B infusion, this also means that the effect of lesions is permanent and not temporally restricted to a discrete experimental time-point. For example, when the BNST was lesioned before conditioning (exp. 1A), we could not determine if this manipulation impacted associative learning or preference expression. Moreover, this chronic damage may result in compensation by other neural systems, which can be difficult to predict or identify. Given this drawback, we must consider that the full effect of our BNST lesions on CPP expression may have been masked by neural compensation. Another concern is that electrolytic lesions also produce inadvertent damage to nerve fibers passing through the targeted region. For this reason, when electrolytic lesions alone are employed, there will remain some uncertainty that the effects found are solely due to destruction of cells within the target region. Hence, using additional manipulations may facilitate interpretation of study results. This highlights a major benefit to our combined use of multiple techniques in these studies, which is a strengthened support for our conclusions.

As with focal drug infusions, DREADDs provide a reversible and temporally defined method to manipulate neural activity. A major advantage of DREADDs is that their activation requires only a minimally invasive peripheral injection of an otherwise inert drug (CNO) and therefore necessitates less handling, which may interfere with behavior. Like lesions, viral expression of DREADDs is long lasting and requires only a single intracranial entry, which reduces the risk of infection and damage associated with repeated microinjections. Moreover, DREADD expression is confined to neurons and does not impact fibers of passage within the region being targeted, giving this technique greater selectivity over lesions. Of note, only those neurons expressing the hM4Di receptor will be silenced when activated by CNO administration. As a result of this, the efficacy of this technique depends greatly on the extent of viral expression, which relies on many factors like titer, serotype, and volume administered. Indeed, a noted disadvantage to DREADDs is the degree of difficulty involved in regulating their expression. In our experiments, we achieved highly localized expression in the BNST with AAV serotype 5. This level of expression resulted in viral transduction and hM4Di expression in a subset of BNST neurons. Therefore, we did not find hM4Di expression throughout all cells contained within this region. Thus it is possible that by using a different AAV serotype or larger vector volume we would have obtained more widespread expression of hM4Di receptors throughout BNST cells. This would likely have resulted in increased CNO-driven inhibition of this region and a greater disruption in CPP expression. Another concern with DREADDs is the potential for perturbation of endogenous receptor activity. Indeed, it is possible that heterologous expression of DREADDs may alter the stoichiometric balance of GPCRs and G proteins in the native system thereby disrupting normal function (Nichols and Roth, 2009). However, the consequences of this possibility on our behavioral outcomes would be difficult to determine. A final concern with DREADDs is the possibility that their activating ligand CNO may have off-target activity or produce effects on its own. This is unlikely given the inability of CNO to back-metabolize to its parent compound clozapine in mice and its subsequent inert nature (Alexander et al., 2009; Armbruster et al., 2007; Guettier et al., 2009). Importantly, our control data illustrate the inert nature of this compound, as doses up to 20 mg/kg had no impact on place preference or locomotor activity. Given the caveats attached to each technique, in combination they provide compelling evidence for tissue-specific regulation of behavior. Here, our finding of BNST involvement in ethanol CPP was consistent across all experimental manipulations and procedural variations. Combined, results from these three techniques provide strong evidence that the BNST modulates ethanol-seeking behavior in mice.

In these experiments, we did not distinguish between BNST subdivisions in our manipulations or behavioral analyses because these areas are quite small in the mouse (some extending under 75 μm mediolaterally) and difficult to individually target without overlap using the techniques we employed. Notably, we compared c-Fos IR between dorsal and lateral BNST within each treatment group (CNO and vehicle) and found no significant differences, indicating similar levels of CS+-induced activation and CNO-induced reduction in these subdivisions (fig. S6). However, there is some evidence to indicate that there exists not only anatomical specificity but also a distinct topology to this region in terms of its regulation of emotion and motivated states. Of note, studies using optogenetics have helped elucidate the specific roles played by intermixed yet distinct neuronal subpopulations within BNST subdivisions. Within the dorsal BNST itself, Kim and colleagues (2013) found that two subregions, the oval nucleus and the anterodorsal BNST, exerted opposite effects on anxiety state. In another study, VTA-projecting glutamate and GABA neurons of the vBNST were shown to differentially regulate anxiety and motivated behavior (Jennings & Sparta et al., 2013). Therefore, it is possible that our results may have varied had we been able to more precisely target discrete subdivisions and/or genetically defined populations of cells within the BNST.

In general, the findings we present here are in agreement with the broader literature indicating that the BNST is involved in reward seeking and appetitive behaviors. Much of this literature has focused on the role of the BNST in stress-induced reinstatement of cocaine seeking (e.g., Erb & Stewart, 1999; Leri et al., 2002; McFarland, 2004; McReynolds et al., 2014) and to a lesser extent morphine (Wang et al. 2001; Wang et al., 2006) and ethanol (Funk, et al., 2006; Lê et al., 2000). However, a growing body of evidence strongly indicates that the BNST is involved in cue-induced cocaine and heroin seeking (Buffalari and See, 2011; Rogers et al., 2008; Sartor and Aston-Jones, 2012). Our findings add to this literature and provide, to our knowledge, the first evidence of BNST involvement in cue-induced ethanol seeking behavior. It is important to note that while studies have supported a role for the BNST in stress-induced drug seeking, cue- and stress-induced seeking are interconnected and likely overlap in their neural circuitry. In fact, in abstinent drug-dependent human subjects, exposure to drug-associated cues can result in concurrent feelings of craving and negative affect (Fox et al., 2007). This raises the possibility that the BNST regulates aspects of both stress- and cue-induced relapse. Indeed, it has been suggested that drug-associated cues may themselves serve as psychological stressors by activating the same neural circuits involved in stress (Silberman and Winder, 2013).

Our data further illustrate the broad role of the BNST in ethanol-mediated behavior and support the idea that the BNST mediates several aspects of alcohol abuse from reward to relapse. As previously shown, acute administration of ethanol activates BNST neurons (Chang et al., 1995; Crankshaw et al., 2003; Demarest et al., 1998; Knapp et al., 2001; Leriche et al., Méndez et al., 2008) and results in an increase of extracellular dopamine within the BNST (Carboni et al., 2000). Moreover, ethanol self-administration is reduced with BNST inactivation (Hyytiä and Koob, 1995) and D1 dopamine receptor antagonism (Eiler et al., 2003), further demonstrating this structure’s role in acute ethanol reward. Withdrawal from chronic ethanol exposure also activates the BNST (Kozell et al., 2005) as does exposure to an ethanol-associated cue (Hill et al., 2007). The present data now directly show that this BNST activity is important for conditioned preference for an ethanol-associated cue. Collectively, these studies suggest the BNST’s role in drug and alcohol addiction is quite broad.

In summary, by inhibiting the BNST through electrolytic lesions (exps. 1A and 1B), pharmacological agents (exp. 2), and chemogenetics (exp. 3), we were able to disrupt expression of ethanol-induced CPP. Taken with a larger literature, our results strongly suggest that the BNST modulates cue-induced ethanol-seeking behavior and indicate that this structure may contribute in multiple ways (i.e., stress and drug-cue sensitivity) to the persistent vulnerability to relapse. Overall, the BNST and its connected circuitry appear to be increasingly promising neural targets for therapies aimed at reducing craving and preventing relapse. Future studies are needed to determine the anatomical and neurochemical nature of the BNST’s role in cue-induced ethanol seeking.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 1. Place preference expression in 5-min intervals across the CPP test in experiment 1. Mean (±SEM) percent time spent on the ethanol-paired floor was significantly reduced in mice that received preconditioning (Exp. 1A; left panel) and post-conditioning (Exp. 1B; right panel) electrolytic lesions of the BNST compared to shams (p’s < 0.001).

Supplementary Figure 2. Place preference expression in 5-min intervals across the CPP test in experiment 2. Data are expressed as Mean (±SEM) percent time spent on the ethanol-paired floor. Mice that received intra-BNST infusion of muscimol + baclofen (M+B) spent significantly less time on the ethanol-paired floor compared to those that received vehicle infusion (p < 0.001).

Supplementary Figure 3. Place preference expression in 5-min intervals across the CPP test in experiment 3. Data are expressed as mean (±SEM) percent time spent on the ethanol-paired floor. CNO-mediated activation of hM4Di significantly reduced time on the ethanol-paired floor compared to vehicle (p < 0.004). This effect was delayed, as no significant difference between CNO and vehicle was found until interval 11–15 m (p = 0.027).

Supplementary Figure 4. Place preference expression during the CPP test in experiment 4. (a) Data are mean (+SEM) time spent on the grid floor in s/min. Compared to vehicle, CNO-mediated activation of hM4Di did not significantly reduce time on the grid floor between conditioning subgroups (Grid+ and Grid−) during an abbreviated (15 m) CPP test. (b) Data are expressed as mean (±SEM) percent time spent on the ethanol-paired floor. When collapsed across conditioning subgroups and analyzed over 5-min intervals, the difference in time spent on the ethanol-paired floor did not significantly differ between CNO and vehicle (p = 0.70).

Supplementary Figure 5. Place preference expression in 5-min intervals across CPP tests 1 and 2 in experiment 5. No difference in time spent on the ethanol-paired floor was found between vehicle and CNO at 10 mg/kg (Test 1; left panel) and 20 mg/kg (Test 2; right panel).

Supplementary Figure 6. Mean (±SEM) c-Fos positive nuclei in dorsal and ventral BNST (dBNST and vBNST) in mice administered vehicle or CNO. No differences were found in c-Fos expression immunoreactivity between dorsal and ventral subdivisions within each treatment group (vehicle and CNO). Compared to vehicle, CNO-mediated activation of hM4Di significantly reduced c-Fos immunoreactivity in dBNST and vBNST (*p’s < 0.001).

Highlights.

We inhibited the BNST using either lesions, microinfusion, or hM4Di activation.

All BNST manipulations disrupted ethanol conditioned place preference.

Ethanol cue exposure induced c-Fos in BNST, which was reduced by hM4Di activation.

Our findings show that the BNST plays an important role in ethanol-seeking behavior.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health under award numbers R01AA007702, UO1AA016647, P60AA010760 and T32AA007468. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. We thank Dr. Sunila Nair for helpful advice regarding viral techniques. A Scholar Award from the ARCS Foundation Portland Chapter, Graduate Scholarship from the OHSU-Vertex Partnership, Neurobiology of Disease Fellowship from the OHSU Brain Institute, Dissertation Research Award from the American Psychological Association, Graduate Research Grant from Psi Chi, and N.L Tartar Trust Fellowship from the OHSU Foundation provided additional support (MMP). Experiments reported here comply with the current laws of the United States.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adamantidis AR, Tsai HC, Boutrel B, Zhang F, Stuber GD, Budygin EA, Touriño C, Bonci A, Deisseroth K, de Lecea L. Optogenetic interrogation of dopaminergic modulation of the multiple phases of reward-seeking behavior. J Neurosci. 2011;31:10829–35. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2246-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander GM, Rogan SC, Abbas AI, Armbruster BN, Pei Y, Allen JA, Nonneman RJ, Hartmann J, Moy SS, Nicolelis MA, McNamara JO, Roth BL. Remote control of neuronal activity in transgenic mice expressing evolved G protein-coupled receptors. Neuron. 2009;63:27–39. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alheid GF. Extended Amygdala and Basal Forebrain. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003;985:185–205. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb07082.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Animals, N.R.C. (US) C. for the U. of the G. for the C. and U. of L., 2011. Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

- Armbruster BN, Li X, Pausch MH, Herlitze S, Roth BL. Evolving the lock to fit the key to create a family of G protein-coupled receptors potently activated by an inert ligand. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:5163–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700293104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aston-Jones G, Georges F, Aston-Jones G. Potent regulation of midbrain dopamine neurons by the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis. J Neurosci. 2001;21:RC160. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-16-j0003.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bechtholt AJ, Cunningham CL. Ethanol-induced conditioned place preference is expressed through a ventral tegmental area dependent mechanism. Behav Neurosci. 2005;119:213–23. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.119.1.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beisker W, Dolbeare F, Gray JW. An improved immunocytochemical procedure for high-sensitivity detection of incorporated bromodeoxyuridine. Cytometry. 1987;8:235–239. doi: 10.1002/cyto.990080218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouton ME, Moody EW. Memory processes in classical conditioning. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2004;28:663–74. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2004.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buffalari DM, See RE. Inactivation of the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis in an animal model of relapse: effects on conditioned cue-induced reinstatement and its enhancement by yohimbine. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2011;213:19–27. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-2008-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carboni E, Silvagni A, Rolando MT, Di Chiara G. Stimulation of in vivo dopamine transmission in the bed nucleus of stria terminalis by reinforcing drugs. J Neurosci. 2000;20:RC102. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-20-j0002.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang SL, Patel NA, Romero AA. Activation and desensitization of Fos immunoreactivity in the rat brain following ethanol administration. Brain Res. 1995;679:89–98. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)00210-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciccocioppo R, Angeletti S, Weiss F. Long-lasting resistance to extinction of response reinstatement induced by ethanol-related stimuli: role of genetic ethanol preference. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2001a;25:1414–9. doi: 10.1097/00000374-200110000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciccocioppo R, Sanna PP, Weiss F. Cocaine-predictive stimulus induces drug-seeking behavior and neural activation in limbic brain regions after multiple months of abstinence: reversal by D(1) antagonists. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001b;98:1976–81. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.4.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crankshaw DL, Briggs JE, Olszewski PK, Shi Q, Grace MK, Billington CJ, Levine AS. Effects of intracerebroventricular ethanol on ingestive behavior and induction of c-Fos immunoreactivity in selected brain regions. Physiol Behav. 2003;79:113–120. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9384(03)00111-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crombag HS, Shaham Y. Renewal of drug seeking by contextual cues after prolonged extinction in rats. Behav Neurosci. 2002;116:169–73. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.116.1.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham CL, Ferree NK, Howard MA. Apparatus bias and place conditioning with ethanol in mice. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2003;170:409–22. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1559-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham CL, Gremel CM, Groblewski PA. Drug-induced conditioned place preference and aversion in mice. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:1662–70. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham CL, Zerizef CL. Effects of combining tactile with visual and spatial cues in conditioned place preference. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2014;124:443–450. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2014.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham CL, Niehus DR, Malott DH, Prather LK. Genetic differences in the rewarding and activating effects of morphine and ethanol. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1992;107:385–393. doi: 10.1007/BF02245166. http://dx.doi.org.liboff.ohsu.edu/10.1007/BF02245166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demarest K, Hitzemann B, Mahjubi E, McCaughran J, Hitzemann R. Further Evidence That the Central Nucleus of the Amygdala Is Associated with the Ethanol-Induced Locomotor Response. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1998;22:1531–1537. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1998.tb03946.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Ciano P, Everitt BJ. Contribution of the ventral tegmental area to cocaine-seeking maintained by a drug-paired conditioned stimulus in rats. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;19:1661–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03232.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong HW, Swanson LW. Projections from bed nuclei of the stria terminalis, anteromedial area: cerebral hemisphere integration of neuroendocrine, autonomic, and behavioral aspects of energy balance. J Comp Neurol. 2006a;494:142–78. doi: 10.1002/cne.20788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong HW, Swanson LW. Projections from bed nuclei of the stria terminalis, dorsomedial nucleus: implications for cerebral hemisphere integration of neuroendocrine, autonomic, and drinking responses. J Comp Neurol. 2006b;494:75–107. doi: 10.1002/cne.20790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong HW, Swanson LW. Projections from bed nuclei of the stria terminalis, posterior division: implications for cerebral hemisphere regulation of defensive and reproductive behaviors. J Comp Neurol. 2004;471:396–433. doi: 10.1002/cne.20002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrman RN, Robbins SJ, Childress AR, O’Brien CP. Conditioned responses to cocaine-related stimuli in cocaine abuse patients. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1992;107:523–529. doi: 10.1007/BF02245266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eiler WJA, Seyoum R, Foster KL, Mailey C, June HL. D1 dopamine receptor regulates alcohol-motivated behaviors in the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis in alcohol-preferring (P) rats. Synapse. 2003;48:45–56. doi: 10.1002/syn.10181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erb S, Stewart J. A role for the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis, but not the amygdala, in the effects of corticotropin-releasing factor on stress-induced reinstatement of cocaine seeking. J Neurosci. 1999;19:RC35. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-20-j0006.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrell MS, Roth BL. Pharmacosynthetics: Reimagining the pharmacogenetic approach. Brain Res. 2013;1511:6–20. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2012.09.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson SM, Eskenazi D, Ishikawa M, Wanat MJ, Phillips PEM, Dong Y, Roth BL, Neumaier JF. Transient neuronal inhibition reveals opposing roles of indirect and direct pathways in sensitization. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14:22–4. doi: 10.1038/nn.2703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson SM, Phillips PEM, Roth BL, Wess J, Neumaier JF. Direct-pathway striatal neurons regulate the retention of decision-making strategies. J Neurosci. 2013;33:11668–76. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4783-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox HC, Bergquist KL, Hong KI, Sinha R. Stress-induced and alcohol cue-induced craving in recently abstinent alcohol-dependent individuals. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007;31:395–403. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00320.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funk D, Li Z, Lê AD. Effects of environmental and pharmacological stressors on c-fos and corticotropin-releasing factor mRNA in rat brain: Relationship to the reinstatement of alcohol seeking. Neuroscience. 2006;138:235–43. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.10.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georges F, Aston-Jones G. Activation of ventral tegmental area cells by the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis: a novel excitatory amino acid input to midbrain dopamine neurons. J Neurosci. 2002;22:5173–87. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-12-05173.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant S, London ED, Newlin DB, Villemagne VL, Liu X, Contoreggi C, Phillips RL, Kimes AS, Margolin A. Activation of memory circuits during cue-elicited cocaine craving. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:12040–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.21.12040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gremel CM, Cunningham CL. Role of test activity in ethanol-induced disruption of place preference expression in mice. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2007;191:195–202. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0651-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guettier JM, Gautam D, Scarselli M, Ruiz de Azua I, Li JH, Rosemond E, Ma X, Gonzalez FJ, Armbruster BN, Lu H, Roth BL, Wess J. A chemical-genetic approach to study G protein regulation of beta cell function in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:19197–202. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906593106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill KG, Ryabinin AE, Cunningham CL. FOS expression induced by an ethanol-paired conditioned stimulus. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2007;87:208–21. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2007.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hitchcock LN, Cunningham CL, Lattal KM. Cue configuration effects in acquisition and extinction of a cocaine-induced place preference. Behav Neurosci. 2014;128:217–27. doi: 10.1037/a0036287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyytiä P, Koob GF. GABAA receptor antagonism in the extended amygdala decreases ethanol self-administration in rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 1995;283:151–9. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(95)00314-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jennings JH, Sparta DR, Stamatakis AM, Ung RL, Pleil KE, Kash TL, Stuber GD. Distinct extended amygdala circuits for divergent motivational states. Nature. 2013;496:224–8. doi: 10.1038/nature12041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ju G, Swanson LW. Studies on the cellular architecture of the bed nuclei of the stria terminalis in the rat: I. Cytoarchitecture. J Comp Neurol. 1989;280:587–602. doi: 10.1002/cne.902800409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SY, Adhikari A, Lee SY, Marshel JH, Kim CK, Mallory CS, Lo M, Pak S, Mattis J, Lim BK, Malenka RC, Warden MR, Neve R, Tye KM, Deisseroth K. Diverging neural pathways assemble a behavioural state from separable features in anxiety. Nature. 2013;496:219–23. doi: 10.1038/nature12018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knapp DJ, Braun CJ, Duncan GE, Qian Y, Fernandes A, Crews FT, Breese GR. Regional Specificity Of Ethanol and NMDA Action in Brain Revealed With FOS-Like Immunohistochemistry and Differential Routes of Drug Administration. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2001;25:1662–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2001.tb02173.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobelt P, Tebbe JJ, Tjandra I, Bae HG, Rüter J, Klapp BF, Wiedenmann B, Mönnikes H. Two immunocytochemical protocols for immunofluorescent detection of c-Fos positive neurons in the rat brain. Brain Res Brain Res Protoc. 2004;13:45–52. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresprot.2004.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozell LB, Hitzemann R, Buck KJ. Acute Alcohol Withdrawal is Associated with c-Fos Expression in the Basal Ganglia and Associated Circuitry: C57BL/6J and DBA/2J Inbred Mouse Strain Analyses. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2005;29:1939–1948. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000187592.57853.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krank MD, Wall AM. Cue exposure during a period of abstinence reduces the resumption of operant behavior for oral ethanol reinforcement. Behav Neurosci. 1990;104:725–33. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.104.5.725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudo T, Uchigashima M, Miyazaki T, Konno K, Yamasaki M, Yanagawa Y, Minami M, Watanabe M. Three types of neurochemical projection from the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis to the ventral tegmental area in adult mice. J Neurosci. 2012;32:18035–46. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4057-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lê AD, Harding S, Juzytsch W, Watchus J, Shalev U, Shaham Y. The role of corticotrophin-releasing factor in stress-induced relapse to alcohol-seeking behavior in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2000;150:317–24. doi: 10.1007/s002130000411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leri F, Flores J, Rodaros D, Stewart J. Blockade of stress-induced but not cocaine-induced reinstatement by infusion of noradrenergic antagonists into the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis or the central nucleus of the amygdala. J Neurosci. 2002;22:5713–8. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-13-05713.2002. 20026536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leriche M, Méndez M, Zimmer L, Bérod A. Acute ethanol induces Fos in GABAergic and non-GABAergic forebrain neurons: a double-labeling study in the medial prefrontal cortex and extended amygdala. Neuroscience. 2008;153:259–67. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.01.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Penzo MA, Taniguchi H, Kopec CD, Huang ZJ, Li B. Experience-dependent modification of a central amygdala fear circuit. Nat Neurosci. 2013;16:332–9. doi: 10.1038/nn.3322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahler SV, Aston-Jones GS. Fos activation of selective afferents to ventral tegmental area during cue-induced reinstatement of cocaine seeking in rats. J Neurosci. 2012;32:13309–26. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2277-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahler SV, Vazey, ElenMahler SV, Vazey EM, Beckley JT, Keistler CR, McGlinchey EM, Kaufling J, Aston-Jones G. Designer receptors show role for ventral pallidum input to ventral tegmental area in cocaine seeking. Nature Neuroscience. 2014;1:577–585. doi: 10.1038/nn.3664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarland K. Limbic and Motor Circuitry Underlying Footshock-Induced Reinstatement of Cocaine-Seeking Behavior. J Neurosci. 2004;24:1551–1560. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4177-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McReynolds JR, Vranjkovic O, Thao M, Baker DA, Makky K, Lim Y, Mantsch JR. Beta-2 adrenergic receptors mediate stress-evoked reinstatement of cocaine-induced conditioned place preference and increases in CRF mRNA in the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis in mice. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2014;231:3953–3963. doi: 10.1007/s00213-014-3535-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moga MM, Saper CB, Gray TS. Bed nucleus of the stria terminalis: cytoarchitecture, immunohistochemistry, and projection to the parabrachial nucleus in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1989;283:315–32. doi: 10.1002/cne.902830302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols CD, Roth BL. Engineered G-protein Coupled Receptors are Powerful Tools to Investigate Biological Processes and Behaviors. Front Mol Neurosci. 2009;2:16. doi: 10.3389/neuro.02.016.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Franklin KBJ. The mouse brain in stereotaxic coordinates. Acad. Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Ray RS, Corcoran AE, Brust RD, Kim JC, Richerson GB, Nattie E, Dymecki SM. Impaired respiratory and body temperature control upon acute serotonergic neuron inhibition. Science. 2011;333:637–42. doi: 10.1126/science.1205295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray RS, Corcoran AE, Brust RD, Soriano LP, Nattie EE, Dymecki SM. Egr2-neurons control the adult respiratory response to hypercapnia. Brain Res. 2013;1511:115–25. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2012.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers JL, Ghee S, See RE. The neural circuitry underlying reinstatement of heroin-seeking behavior in an animal model of relapse. Neuroscience. 2008;151:579–88. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sartor GC, Aston-Jones G. Regulation of the ventral tegmental area by the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis is required for expression of cocaine preference. Eur J Neurosci. 2012;36:3549–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2012.08277.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz W. Responses of midbrain dopamine neurons to behavioral trigger stimuli in the monkey. J Neurophysiol. 1986;56:1439–1461. doi: 10.1152/jn.1986.56.5.1439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silberman Y, Winder DG. Emerging role for corticotropin releasing factor signaling in the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis at the intersection of stress and reward. Front psychiatry. 2013;4:42. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2013.00042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha R, Li CSR. Imaging stress- and cue-induced drug and alcohol craving: association with relapse and clinical implications. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2007;26:25–31. doi: 10.1080/09595230601036960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tagliaferro P, Tandler CJ, Ramos AJ, Pecci Saavedra J, Brusco A. Immunofluorescence and glutaraldehyde fixation. A new procedure based on the Schiff-quenching method. J Neurosci Methods. 1997;77:191–7. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(97)00126-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vazey EM, Aston-Jones G. Designer receptor manipulations reveal a role of the locus coeruleus noradrenergic system in isoflurane general anesthesia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:3859–64. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1310025111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wanat MJ, Willuhn I, Clark JJ, Phillips PEM. Phasic dopamine release in appetitive behaviors and drug addiction. Curr Drug Abuse Rev. 2009;2:195–213. doi: 10.2174/1874473710902020195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Fang Q, Liu Z, Lu L. Region-specific effects of brain corticotropin-releasing factor receptor type 1 blockade on footshock-stress- or drug-priming-induced reinstatement of morphine conditioned place preference in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2006;185:19–28. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-0262-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Cen X, Lu L. Noradrenaline in the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis is critical for stress-induced reactivation of morphine-conditioned place preference in rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 2001;432:153–61. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(01)01487-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss F, Martin-Fardon R, Ciccocioppo R, Kerr TM, Smith DL, Ben-Shahar O. Enduring resistance to extinction of cocaine-seeking behavior induced by drug-related cues. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2001;25:361–72. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(01)00238-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wess J, Nakajima K, Jain S. Novel designer receptors to probe GPCR signaling and physiology. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2013;34:385–392. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2013.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zironi I, Burattini C, Aicardi G, Janak PH. Context is a trigger for relapse to alcohol. Behav Brain Res. 2006;167:150–155. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2005.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1. Place preference expression in 5-min intervals across the CPP test in experiment 1. Mean (±SEM) percent time spent on the ethanol-paired floor was significantly reduced in mice that received preconditioning (Exp. 1A; left panel) and post-conditioning (Exp. 1B; right panel) electrolytic lesions of the BNST compared to shams (p’s < 0.001).

Supplementary Figure 2. Place preference expression in 5-min intervals across the CPP test in experiment 2. Data are expressed as Mean (±SEM) percent time spent on the ethanol-paired floor. Mice that received intra-BNST infusion of muscimol + baclofen (M+B) spent significantly less time on the ethanol-paired floor compared to those that received vehicle infusion (p < 0.001).

Supplementary Figure 3. Place preference expression in 5-min intervals across the CPP test in experiment 3. Data are expressed as mean (±SEM) percent time spent on the ethanol-paired floor. CNO-mediated activation of hM4Di significantly reduced time on the ethanol-paired floor compared to vehicle (p < 0.004). This effect was delayed, as no significant difference between CNO and vehicle was found until interval 11–15 m (p = 0.027).

Supplementary Figure 4. Place preference expression during the CPP test in experiment 4. (a) Data are mean (+SEM) time spent on the grid floor in s/min. Compared to vehicle, CNO-mediated activation of hM4Di did not significantly reduce time on the grid floor between conditioning subgroups (Grid+ and Grid−) during an abbreviated (15 m) CPP test. (b) Data are expressed as mean (±SEM) percent time spent on the ethanol-paired floor. When collapsed across conditioning subgroups and analyzed over 5-min intervals, the difference in time spent on the ethanol-paired floor did not significantly differ between CNO and vehicle (p = 0.70).

Supplementary Figure 5. Place preference expression in 5-min intervals across CPP tests 1 and 2 in experiment 5. No difference in time spent on the ethanol-paired floor was found between vehicle and CNO at 10 mg/kg (Test 1; left panel) and 20 mg/kg (Test 2; right panel).