Abstract

Purpose

Isolated limb infusion (ILI) with melphalan (M-ILI) dosing corrected for ideal body weight (IBW) is a well-tolerated treatment for patients with in-transit melanoma with a 29% complete response rate. ADH-1 is a cyclic pentapeptide that disrupts N-cadherin adhesion complexes. In a preclinical animal model, systemic ADH-1 given with regional melphalan demonstrated synergistic antitumor activity, and in a phase I trial with M-ILI it had minimal toxicity.

Patients and Methods

Patients with American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) stage IIIB or IIIC extremity melanoma were treated with 4,000 mg of ADH-1, administered systemically on days 1 and 8, and with M-ILI corrected for IBW on day 1. Drug pharmacokinetics and N-cadherin immunohistochemical staining were performed on pretreatment tumor. The primary end point was response at 12 weeks determined by Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) criteria.

Results

In all, 45 patients were enrolled over 15 months at four institutions. In-field responses included 17 patients with complete responses (CRs; 38%), 10 with partial responses (22%), six with stable disease (13%), eight with progressive disease (18%), and four (9%) who were not evaluable. Median duration of in-field response among the 17 CRs was 5 months, and median time to in-field progression among 41 evaluable patients was 4.6 months (95% CI, 4.0 to 7.1 months). N-cadherin was detected in 20 (69%) of 29 tumor samples. Grade 4 toxicities included creatinine phosphokinase increase (four patients), arterial injury (one), neutropenia (one), and pneumonitis (one).

Conclusion

To the best of our knowledge, this phase II trial is the first prospective multicenter ILI trial and the first to incorporate a targeted agent in an attempt to augment antitumor responses to regional chemotherapy. Although targeting N-cadherin may improve melanoma sensitivity to chemotherapy, no difference in response to treatment was seen in this study.

INTRODUCTION

Despite appropriate initial therapy, approximately 2% to 10% of extremity melanomas recur as in-transit (IT) metastases representing melanoma tumor deposits in the dermal or subcutaneous lymphatic vessels.1,2 The presence of IT metastases is associated with poor prognosis with 5-year survival rates ranging from 12% to 37%.3–5 Systemic chemotherapy generally has poor, short-lived objective response rates.6,7 The techniques of hyperthermic isolated limb perfusion8–12 and ILI13–16 with melphalan (M-ILI), with or without dactinomycin, allow delivery of regional chemotherapy several orders of magnitude higher than can be attained with systemic administration. In a recent multicenter retrospective study17 of standard of care M-ILI plus dactinomycin, the complete response (CR) rate was found to be 29% in patients (n = 66) who had their melphalan dose corrected for ideal body weight (IBW). New strategies to improve response rates for melanoma have focused on targeted agents that can increase drug delivery to tumors, improve sensitivity to chemotherapy by modulating known resistance proteins, or target signaling proteins in survival or apoptotic pathways.18–20

ADH-1 is a novel, pentapeptide drug that targets and disrupts N-cadherin adhesion complexes. ADH-1 was well tolerated in phase I and II single-agent studies and showed evidence of antitumor activity restricted to patients with N-cadherin–positive tumors.21–23 N-cadherin is theoretically an ideal protein to target in melanoma because it is expressed on the majority of melanoma tumors as they progress from a predominantly E-cadherin phenotype as melanocytes to a predominantly N-cadherin phenotype during the transition into melanoma and the acquisition of a vertical growth phase.24–26 We have demonstrated that ADH-1–induced disruption of N-cadherin adhesion complexes leads to downstream alterations in intracellular signaling pathways that sensitize tumor cells to melphalan and induce alterations in vascular permeability leading to increased melphalan drug delivery to tumors.27,28 In preclinical studies that use a rat xenograft model of extremity melanoma, tumors treated with systemic ADH-1 in combination with M-ILI demonstrated decreased growth and increased apoptosis when compared with tumors treated with M-ILI alone.27,28 We have completed a multicenter phase I study of systemic ADH-1 in combination with M-ILI.29 Encouraging response rates were seen with a CR rate of 50% with no dose-limiting toxicities (n = 16). Here, we report the results from what is, to the best of our knowledge, the first prospective multicenter phase II study of systemic ADH-1 in combination with M-ILI for patients with advanced extremity melanoma.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patient Eligibility

Patients were eligible for study if they were ≥ 18 years of age, had histologically confirmed recurrent American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) stage IIIB or IIIC extremity melanoma,30 tissue available for N-cadherin staining by immunohistochemistry (IHC), directly measurable cutaneous disease distal to planned tourniquet placement, and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of 0 or 1. Patients who had previously received ADH-1 were excluded, although previous treatment with M-ILI was allowed. All patients were required to give informed consent, and the institutional review boards of the participating institutions approved the study.

Study Design

This trial was an open-label, single-arm, multicenter phase II study. Treatment consisted of 4,000 mg of intravenous ADH-1 administered on days 1 and 8 in combination with melphalan at 10 mg/L delivered regionally via ILI a minimum of 4 hours after ADH-1 on day 1 for the upper extremity and at 7.5 mg/L for the lower extremity corrected for IBW.16 The 4,000-mg dose of ADH-1 was previously demonstrated to be safe in patients and was the highest dose for which there were already extensive safety data.29,31 Administration of ILI was performed as described previously16 by using a rapid infusion of melphalan (2 to 5 minutes) in the arterial catheter after the extremity had been warmed to at least 37.0°C.

Assessment of Tumor Response and Toxicity

Tumor response was evaluated according to Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) criteria modified for cutaneous lesions at one time point 3 months post-ILI.16 Patients were classified as having a CR, partial response (PR), stable disease (SD), or progressive disease (PD). Toxicity was assessed by using the National Cancer Institute's Common Toxicity Criteria for Adverse Events version 3.0 (CTCAEv3).

Pharmacokinetic Evaluations

High-performance liquid chromatography was used to measure melphalan infusion circuit concentrations and to measure the concentration of ADH-1 just before the administration of melphalan.16,32

Immunohistochemistry

N-cadherin IHC staining and scoring were conducted by Biotechnics (Hillsborough, NC). Sections for IHC staining were processed from tumor samples that had been embedded in paraffin wax blocks. Slides were incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibody (Invitrogen 18-0224, Carlsbad, CA; 1:200 dilution) or mouse isotype negative control (Invitrogen 08-6599; Invitrogen), followed by incubation with secondary antibody (biotinylated goat antimouse; Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories 115-066-071, West Grove, PA; 1:500 dilution) for 30 minutes at room temperature. ABC reagent (Vectastain Elite ABC Kit, Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA) was applied to sections and incubated for 30 minutes at 37°C. Sections were developed in diaminobenzidine for 7 minutes at room temperature and counterstained with hematoxylin.

Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction

Tumor biopsies were homogenized by using Lysing Matrix A (MP Biomedicals, Solon, OH) and a mini bead-beater (Biospec Products, Bartlesville, OK). RNA was isolated, cDNA was synthesized, and quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) was performed as described previously.33 N-cadherin expression values were normalized to β-actin and expressed as fold difference from a human reference RNA sample (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). The reference RNA was assigned a value of 1; patient sample values < 1 were considered to be negative while patient sample values ≥ 1 were considered to be N-cadherin–positive.

Microarray Gene Expression Analysis

RNA was reverse transcribed, labeled, and hybridized to the Affymetrix Human Genome U133plus2 (HU133+2) GeneChip (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA) at the Duke University Microarray Core Facility. Gene expression data of tumor samples are available at Gene Expression Omnibus (accession number GSE22968). Gene expression data were normalized by the MAS5.0 algorithm by using the Affymetrix Expression Console software (v1.0; Affymetrix), log2 transformed by using the MATLAB log2 function (Mathworks, Natick, MA), and normalized against 69 Affymetrix housekeeping gene probes using Bayesian factor regression modeling.34 Pearson correlation analysis was performed across Bayesian factor regression modeling–normalized matched patient data (pre–ADH-1 and post–ADH-1; 20 samples, 10 patients) yielding a Pearson coefficient of correlation r. The genes were ranked on the basis of r, and genes with an absolute correlation coefficient < 0.6 were filtered out yielding a list of 100 genes. The data were mean centered across genes and arrays and clustered by using unsupervised hierarchical clustering (Cluster v3.0,34a uncentered correlation similarity metric and average linkage clustering); a heat map diagram was generated (Java TreeView; Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA).35

Statistics

With response at 3 months as the primary end point of this trial, the target accrual was 50 patients, which would ensure that the maximum width of the exact 90% binomial CI and the response rate was no larger than 0.25. The response would be considered improved if the lower bound of the CI did not include the historical control rate of 0.29. Accrual was stopped at 45 for lack of funding, and the maximum width of the CI increased by 0.01. All other end points were considered secondary. Time to in-field progression (TTP-I) was defined as the number of months between surgery and in-field progression; out-of-field progressions were ignored. Time to out-of-field progression was defined analogously. Duration of response was defined in patients with CR as the number of months between the 3-month response assessment and in-field progression; out-of-field progressions were ignored. Kaplan-Meier analysis was used to estimate all three time-to-event distributions by censoring patients on the date last seen alive and with no progression.

RESULTS

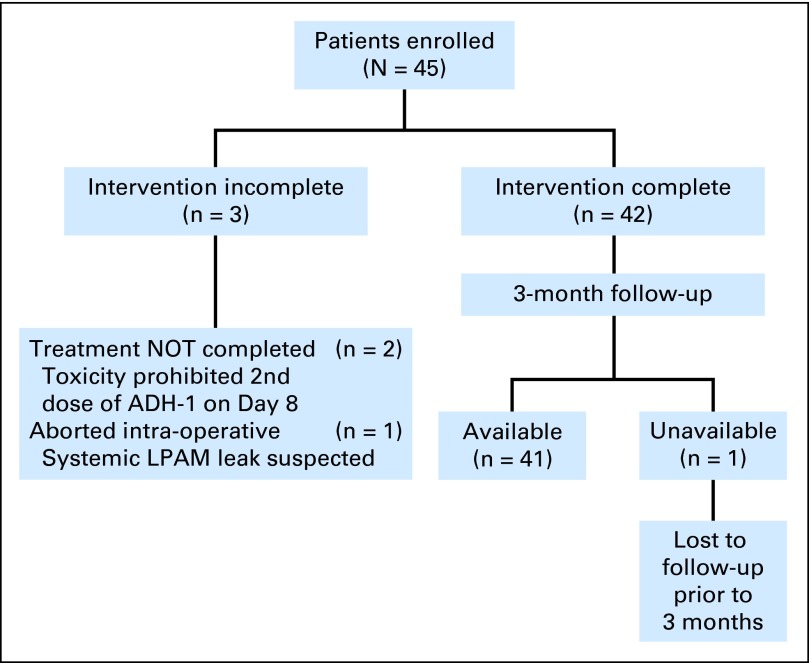

A total of 45 patients were enrolled onto the trial over a 15-month period: 24 patients were treated at Duke University, 14 at MD Anderson Cancer Center, six at Moffitt Cancer Center, and one at the University of Florida. Three of the 45 patients did not complete the entire treatment, and one other patient did not have response data (Fig 1). Patient characteristics are listed in Table 1. ILI procedural variables were similar to what we have previously reported16,17 with a median peak temperature of 38.7°C (range, 37 to 40.1°C) in this study.

Fig 1.

Flow diagram of patients enrolled in the trial. Forty-two patients completed the intervention, and 41 patients were available for 3-month follow-up. LPAM, L-phenylalanine mustard.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics

| Characteristic | No. | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | ||

| Median | 61 | |

| Range | 29-89 | |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 19 | 42 |

| Female | 26 | 58 |

| AJCC stage | ||

| IIIB | 17 | 38 |

| IIIC | 28 | 62 |

| Disease burden | ||

| High | 12 | 27 |

| Low | 33 | 73 |

| Previous ILI/HILP | 11 | 25 |

| N-cadherin positive | 20 | 69* |

Abbreviations: AJCC, American Joint Committee on Cancer; ILI, isolated limb infusion; HILP, hyperthermic isolated limb perfusion.

20 of 29 patients tested.

Clinical Response

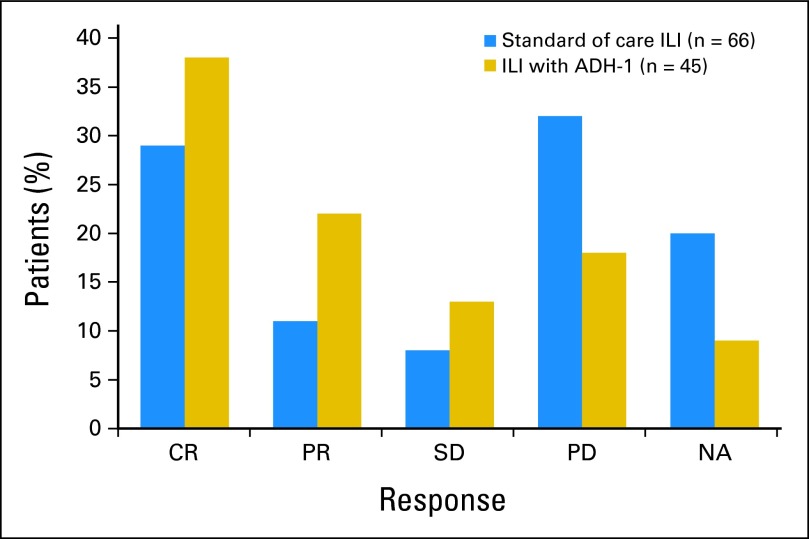

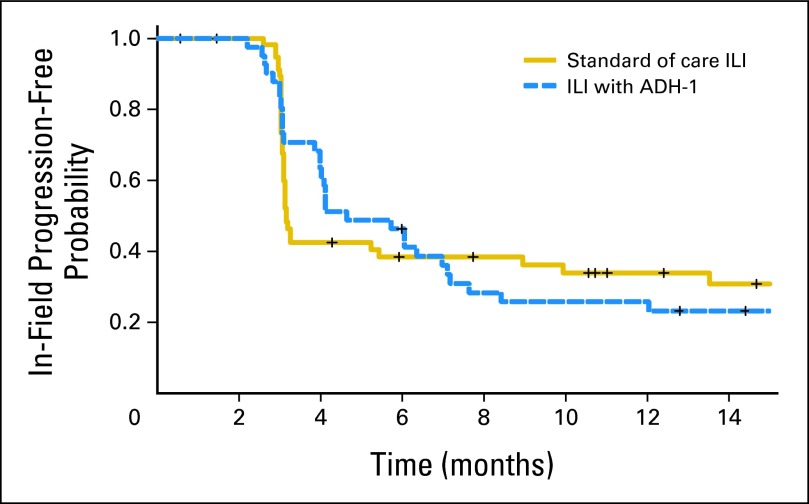

Among the 45 patients in this study, 9% (n = 4) were not evaluable for response, 38% (n = 17) had a CR, 22% (n = 10) had a PR, 13% (n = 6) had SD, and 18% (n = 8) had PD. The 90% CI of the CR rate (38%) was 0.26 to 0.51. The estimated median duration of response among the 17 CRs was 5 months (95% CI, 3.0 to not estimable). Twelve of these patients had progressed in-field by the time of this analysis; median follow-up among the five patients who had not progressed was 22 months. Median TTP-I among all 41 evaluable patients was 4.6 months (95% CI, 4.0 to 7.1 months). Thirty-one of these patients had progressed in-field by the time of this analysis; median follow-up among the 10 patients who had not progressed was almost 20 months. Median time to out-of-field progression in all 45 patients was 10.2 months (95% CI, 6.2 to 19.0 months). Twenty-eight of the 45 patients had progressed out-of-field by the time of this analysis; median follow-up among the 17 who had not progressed was 19.4 months. Seventy-five percent (21 of 28) of field progressions were to regional lymph nodes. Figure 2 compares the response rates of this trial to those of a multicenter retrospective study of M-ILI (n = 66). Figure 3 compares the TTP-I of this trial (median 4.6 months) to that of 59 patients at Duke University undergoing only M-ILI (median 3.2 months).16 These comparisons were exploratory and not specified by the protocol.

Fig 2.

Response in patients in this trial (blue) compared with responses seen in a retrospective multicenter study of isolated limb infusion (ILI; gold). CR, complete response; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease; PD, progressive disease; NA, not applicable.

Fig 3.

Time to progression curves for patients in this study (dashed blue line) compared with those treated at Duke University with isolated limb infusion with melphalan (M-ILI) alone (solid gold line). In the present study, the median time to progression was 4.6 months (95% CI, 4.0 to 7.1 months) compared with a median time to progression of 3.2 months (95% CI, 3.1 to 9.9 months) in the previously studied group receiving M-ILI alone.

Toxicity

The treatment was generally well tolerated, and the addition of ADH-1 did not appear to increase the toxicity of M-ILI alone. Common grade 1 toxicities mostly related to ILI were rash/erythema in 15 patients (33%) and extremity pain in 12 patients (27%). There were nine grade 4 toxicities: five patients had serologic grade 4 toxicities (four patients had increases in creatine kinase [CK] and one patient had neutropenia that resolved), and four patients had clinical grade 4 toxicities. CK values are routinely measured after regional chemotherapy treatments as markers of muscle toxicity.16,17 The four patients in this study with grade 4 CK increases were treated with dexamethasone and the CKs subsequently normalized. As expected from previous studies, patients who experienced grade 3 to 4 toxicities had higher peak CKs and were more likely to be female than patients with grade 1 to 2 toxicities.16

The four grade 4 clinical toxicities were arterial injury, acute respiratory distress syndrome, pneumonitis, and pulmonary infiltrate. The arterial injury occurred 24 hours after ILI and was a superficial femoral artery dissection with a distal embolism possibly caused by placement of the arterial catheter. The patient underwent Fogarty thrombectomy and end arterectomy of the distal superficial femoral artery. Approximately 1 year after ILI, this patient had an extremity amputation due to progression of vascular disease. Whether this was exacerbated by the ILI and complication is unclear. The three grade 4 pulmonary toxicities all occurred in the same patient. On the second postoperative day, the patient developed acute respiratory distress requiring reintubation for 24 hours. Bronchoscopy demonstrated inflamed proximal bronchial mucosa with areas of petechial hemorrhage. The etiology of this event was never clearly established although aspiration, pulmonary embolus, cardiac failure, and bacterial pneumonia were excluded. The patient recovered after being given steroids and antibiotics and was discharged on postoperative day 10.

N-Cadherin

Twenty-nine study patients were tested for N-cadherin by IHC and/or qPCR; 20 of these patients (69%) tested positive for N-cadherin. Twenty-six of the 29 patients were also evaluated for response. Among these 26 patients, the 18 who tested positive for N-cadherin had a CR rate of 39%; the eight who tested negative had a CR rate of 63%. Eleven patients had tumor tissue analyzed by qPCR for N-cadherin expression. In 10 patients, the results of qPCR agreed with IHC; in one patient, tumor tissue was negative for N-cadherin by IHC but positive by qPCR.

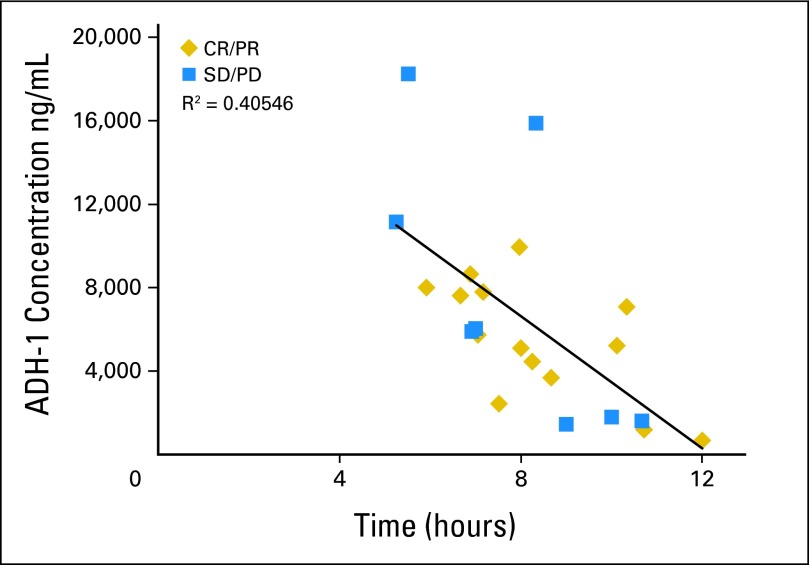

Pharmacokinetics

ADH-1 pharmacokinetics were examined in patients undergoing treatment at Duke University (n = 24). The goal was to administer melphalan approximately 3 to 4 half-lives (6 to 8 hours) after the initial dose of ADH-1 to mimic initial dosing that was used in our preclinical animal model in which ADH-1 pretreatment markedly improved the efficacy of M-ILI.27,36 The median time between the dose of ADH-1 and the administration of melphalan was 7.7 hours (range, 5 to 12 hours). The plasma concentration of ADH-1 measured just before melphalan administration was, in general, predictably lower as the length of time after ADH-1 administration was longer (Fig 4). Median plasma concentration of ADH-1 was 5,818 ng/mL; when calculated according to response status (CR/PR v SD/PD), the median plasma concentrations were similar.

Fig 4.

Plots of the time between the dose of ADH-1 and melphalan delivery via isolated limb infusion (ILI; in hours) versus the measured plasma concentration of ADH-1 (μg/mL) at the beginning of ILI. As expected, the concentration of ADH-1 decreased as more time elapsed in all patients (r = 0.40). Blue squares represent patients experiencing a complete response (CR) or partial response (PR); gold diamonds represent patients who had progressive disease (PD) or stable disease (SD).

Melphalan pharmacokinetics were analyzed in 28 patients. Median melphalan dose was 50.1 mg; median peak plasma concentration of melphalan during ILI was 25.8 μg/mL. Patients with and without response (CR + PR v SD/PD) had similar medians of both melphalan dose and peak plasma concentration. Likewise, patients with and without grade 3 to 4 toxicities had similar medians. As expected, the peak plasma concentration of melphalan during ILI correlated with the dose of melphalan administered (Pearson correlation 0.58).

ADH-1–Induced Changes in Gene Expression

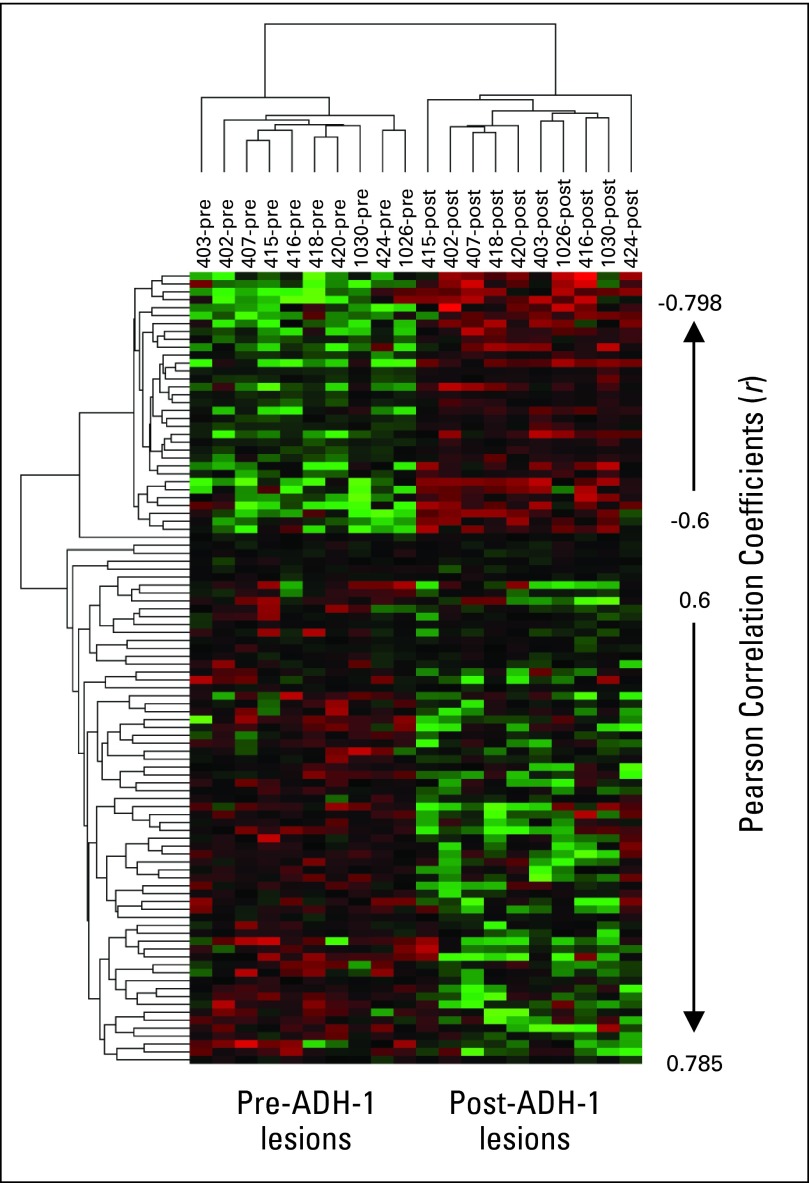

In the absence of a specific ADH-1–induced target protein alteration that could be monitored, we examined ADH-1–induced alterations in gene expression to determine whether doses of ADH-1 were functionally active. For 10 patients, two matched biopsies were available for analysis: one obtained just before ADH-1 infusion on day 1 (pre) and the second just before ILI, approximately 8 hours after day 1 ADH-1 infusion (post). Pearson correlation analysis identified 100 genes that showed a significant correlation with drug treatment (P ranging from < .001 to .005). Thirty-three genes showed higher expression following treatment with one dose of ADH-1 and 67 genes showed reduced expression (Fig 5 and Appendix Tables A1 and A2, online only). Gene Ontology36a biologic function analysis revealed three genes related to cell adhesion with altered expression. Plakophilin 2 (PKP2), which is thought to be important in linking cadherins to cytoskeletal filaments and may regulate β-catenin activity, showed decreased expression following ADH-1 treatment. Protocadherin-γ-C4 (PCDHGC4), a cadherin family protein, and claudin 3 (CLDN3), a component of tight junctions, both showed increased expression following ADH-1 treatment.

Fig 5.

Gene expression microarray in 10 patients who had two matched biopsies: one obtained just before infusion with ADH-1 on day 1 (pre) and the second just before isolated limb infusion (ILI), approximately 8 hours after day 1 ADH-1 infusion (post). Rows represent patient samples; columns represent genes. Red represents relatively higher expression; green represents relatively lower expression.

DISCUSSION

In this multicenter prospective study of ILI in 45 patients, we report a CR rate of 38%, PR rate of 23%, SD in 13%, PD in 18%, and 9% not evaluable. In the U.S. multicenter retrospective study of M-ILI, patients who had their dose corrected for IBW (n = 66) had a CR rate of 29% and a PR rate of 11%. The overall response rate (CR + PR) of 60%, as reported in this ADH-1 plus M-ILI trial, is encouraging compared with the overall response rate of 40% in the multicenter study and compared with other single-center studies reported by other U.S. centers.16,17,37 However, the 90% CI around the ADH-1 response rate of 0.38 included 0.29, which is the response rate of the historical control group treated with melphalan alone. We also compared the TTP-I between patients from this study who received systemic ADH-1 in addition to M-ILI to that of a previous cohort of patients from Duke who were treated with M-ILI.16 Although there was an early trend to an improved TTP-I for patients in this trial (4.6 v 3.2 months), there was no difference when comparing the two curves out to 15 months. Optimization of response to systemic ADH-1 in combination with M-ILI will depend on a better understanding of the mechanism of action of ADH-1 as well as a better understanding of what patient-related factors contribute to response. Although this trial was exploratory and was limited by sample size, gene expression data supported ADH-1–induced changes in the expression of genes that may ultimately contribute to an understanding of the mechanism of action of ADH-1.

In the multicenter study of M-ILI, patients receiving melphalan doses corrected for IBW had significantly lower grade ≥ 3 toxicity (21% v 47%; P < .001).17 The rate of grade ≥ 3 toxicity in this study, in which all patients had a melphalan dose corrected for IBW, was 20% (n = 9). We have previously reported that standard melphalan dosing results in a wide range of plasma melphalan concentrations.38 In this study, correction of the melphalan dose for IBW resulted in a more predictable pharmacokinetic profile of melphalan. Additionally, ADH-1 did not appear to increase toxicity, the combination therapy was well tolerated, and nearly all patients (42 of 45) were able to receive the planned treatment.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first prospective multicenter study of ILI and the first to use combination therapy with a systemic targeted agent. IT melanoma provides an ideal clinical setting in which to explore new therapies by allowing for both analysis of drug pharmacokinetics and evaluation of tumor properties on concurrently obtained sequential tumor specimens. In this study, we measured drug pharmacokinetics and analyzed tumor tissue to determine their correlation with response and toxicity. We did not observe a correlation between tumor N- cadherin expression and response. However, recent studies suggest that vascular N-cadherin expression may be important in the mechanism of action of ADH-1 and suggest that increased tumor responses may be related to ADH-1–induced increases in vascular permeability.28 For this reason, and in contrast to many other targeted therapy trials, we did not limit the study population to patients with high tumor N-cadherin. Studies are currently underway to explore the relationship between tumor and vascular N-cadherin and how disrupting this interaction can make tumors more sensitive to chemotherapy.

In conclusion, in this prospective multicenter study of ILI, systemic ADH-1 in combination with M-ILI was found to be a well-tolerated treatment for patients with advanced extremity melanoma. Although the response rate with the addition of ADH-1 compared with melphalan alone was additively larger by 0.16, there was no difference in the overall TTP-I of regional disease. Future directions for study include defining more clearly the mechanism of action of ADH-1 seen in preclinical models to determine whether more optimal dosing or identification of a group of patients with appropriate N-cadherin expression on target tissue can improve response rates of regionally administered chemotherapy.

Appendix

Table A1.

Increased Expression Post–ADH-1

| Gene ID | Name | Gene Description |

|---|---|---|

| 215724_at | PLD1 | Phospholipase D1, phosphatidylcholine-specific |

| 240597_at | — | — |

| 242566_at | VASH1 | Vasohibin 1 |

| 213651_at | PIB5PA | Phosphatidylinositol (4,5) bisphosphate 5-phosphatase, A |

| 213072_at | CYHR1 | Cysteine/histidine-rich 1 |

| 235050_at | SLC2A12 | Solute carrier family 2 (facilitated glucose transporter), member 12 |

| 1557727_at | — | — |

| 231754_at | PCDHGC4 | Protocadherin gamma subfamily C, 4 |

| 203953_s_at | CLDN3 | Claudin 3 |

| 216425_at | — | CDNA: FLJ22812 fis, clone KAIA2955 |

| 221167_s_at | CCDC70 | Coiled-coil domain containing 70 |

| 1564905_at | — | EST from clone DKFZp434P1912, 3′ end |

| 218759_at | DVL2 | Dishevelled, dsh homolog 2 (Drosophila) |

| 1557056_at | LOC133491 | Hypothetical protein LOC133491 |

| 200676_s_at | UBE2L3 | Ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2L 3 |

| 216208_s_at | CREBL1 | cAMP responsive element binding protein-like 1 |

| 217910_x_at | MLX | MAX-like protein X |

| 222769_at | MTHFSD | Methenyltetrahydrofolate synthetase domain containing |

| 1559559_at | C9orf79 | Chromosome 9 open reading frame 79 |

| 230397_at | — | Transcribed locus |

| 239078_at | C1orf58 | Chromosome 1 open reading frame 58 |

| 208105_at | GIPR | Gastric inhibitory polypeptide receptor |

| 207348_s_at | LIG3 | Ligase III, DNA, ATP-dependent |

| 1555339_at | RAP1A | RAP1A, member of RAS oncogene family |

| 211968_s_at | HSP90AA1 | Heat shock protein 90 kDa alpha (cytosolic), class A member 1 |

| 217002_s_at | HTR3A | 5-Hydroxytryptamine (serotonin) receptor 3A |

| 1552929_at | GRK7 | G protein-coupled receptor kinase 7 |

| 225309_at | PHF5A | PHD finger protein 5A |

| 238923_at | SPOP | Speckle-type POZ protein |

| 234236_at | FLJ20294 | Hypothetical protein FLJ20294 |

| 1565677_at | — | Transcribed locus |

| 203954_x_at | CLDN3 | Claudin 3 |

| 215723_s_at | PLD1 | Phospholipase D1, phosphatidylcholine-specific |

Abbreviation: ADH-1, a cyclic pentapeptide that disrupts N-cadherin adhesion complexes; ID, identification.

Table A2.

Decreased Expression Post–ADH-1

| Gene ID | Name | Gene Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1556469_s_at | — | CDNA FLJ34611 fis, clone KIDNE2014112 |

| 1563116_at | — | Homo sapiens, clone IMAGE:5166470, mRNA |

| 223025_s_at | AP1M1 | Adaptor-related protein complex 1, mu 1 subunit |

| 213591_at | ALDH7A1 | Aldehyde dehydrogenase 7 family, member A1 |

| 234789_at | — | CDNA FLJ13017 fis, clone NT2RP3000628 |

| 1564584_at | — | CDNA FLJ25771 fis, clone TST06415 |

| 214559_at | DRD3 | Dopamine receptor D3 |

| 1567361_at | BDNFOS | Brain-derived neurotrophic factor opposite strand |

| 240439_at | — | — |

| 204512_at | HIVEP1 | Human immunodeficiency virus type I enhancer binding protein 1 |

| 1566577_at | — | MRNA; cDNA DKFZp547I1410 (from clone DKFZp547I1410) |

| 1561027_at | LOC646241 | Hypothetical protein LOC646241 |

| 1556012_at | KLHDC7A | Kelch domain containing 7A |

| 1558658_at | ZNF391 | Zinc finger protein 391 |

| 226096_at | FNDC5 | Fibronectin type III domain containing 5 |

| 1560169_at | — | CDNA FLJ32626 fis, clone SYNOV1000045 |

| 220697_at | — | CDNA clone IMAGE:40003562 |

| 239618_at | SEC16B | SEC16 homolog B (S. cerevisiae) |

| 221093_at | BRD7P3 | Bromodomain containing 7 pseudogene 3 |

| 233466_at | — | MRNA; cDNA DKFZp434G0523 (from clone DKFZp434G0523) |

| 216745_x_at | — | CDNA: FLJ20953 fis, clone ADSE01979 |

| 1562974_at | — | CDNA clone IMAGE:5302821 |

| 244120_at | LOC340178 | Hypothetical protein LOC340178 |

| 215852_x_at | C20orf117 | Chromosome 20 open reading frame 117 |

| 237979_at | — | — |

| 1561327_at | C6orf122 | Chromosome 6 open reading frame 122 |

| 1560453_at | — | MRNA; cDNA DKFZp564G203 (from clone DKFZp564G203) |

| 241512_at | SPATC1 | Spermatogenesis and centriole associated 1 |

| 241663_at | — | — |

| 243674_at | — | — |

| 230605_at | — | Transcribed locus, strongly similar to XP_001149935.1 potassium voltage-gated channel, shaker-related subfamily, beta member 1 isoform 4 [Pan troglodytes] |

| 240743_at | — | — |

| 1555509_a_at | SLC25A41 | Solute carrier family 25, member 41 |

| 243136_at | — | Transcribed locus |

| 238251_at | — | Transcribed locus |

| 1561962_at | — | CDNA clone IMAGE:4794289 |

| 208337_s_at | NR5A2 | Nuclear receptor subfamily 5, group A, member 2 |

| 234044_at | — | CDNA: FLJ22608 fis, clone HSI04854 |

| 236230_at | — | MRNA; cDNA DKFZp434A202 (from clone DKFZp434A202) |

| 233209_at | LOC200609 | Hypothetical protein LOC200609 |

| 216156_at | RECK | Reversion-inducing-cysteine-rich protein with kazal motifs |

| 215962_at | — | EST clone 22,453 mariner transposon Hsmar1 sequence |

| 243078_at | — | — |

| 241349_at | — | Transcribed locus |

| 207589_at | ADRA1B | Adrenergic, alpha-1B-, receptor |

| 231382_at | FGF18 | Fibroblast growth factor 18 |

| 230478_at | OIT3 | Oncoprotein induced transcript 3 |

| 238488_at | IPO11 | Importin 11 |

| 228609_at | LOC728439/// LOC729043 | Hypothetical protein LOC728439///hypothetical protein LOC729043 |

| 238111_at | SDCCAG3 | Serologically defined colon cancer antigen 3 |

| 1565924_a_at | — | CD77 protein |

| 1556491_at | — | Full length insert cDNA clone YB29A02 |

| 236747_at | — | — |

| 233096_at | KIAA1109 | KIAA1109 |

| 1563250_at | — | Homo sapiens, clone IMAGE:3451264, mRNA |

| 230858_at | — | CDNA FLJ20470 fis, clone KAT06815 |

| 1569136_at | MGAT4A | Mannosyl (alpha-1,3-)-glycoprotein beta-1,4-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase, isozyme A |

| 231338_at | NUT | Nuclear protein in testis |

| 232276_at | HS6ST3 | Heparan sulfate 6-O-sulfotransferase 3 |

| 214154_s_at | PKP2 | Plakophilin 2 |

| 223499_at | C1QTNF5 | C1q and tumor necrosis factor–related protein 5 |

| 211627_x_at | ESR1 | Estrogen receptor 1 |

| 215865_at | SYT12 | Synaptotagmin XII |

| 241070_at | — | Transcribed locus |

| 1558052_at | TMED4 | Transmembrane emp24 protein transport domain containing 4 |

| 228936_at | — | Transcribed locus |

| 234506_at | — | MRNA; cDNA DKFZp564M163 (from clone DKFZp564M163) |

Abbreviation: ADH-1, a cyclic pentapeptide that disrupts N-cadherin adhesion complexes; ID, identification.

Footnotes

Supported by Grant No. AHX2007-075 D100-C from Adherex Technologies and the Duke University Melanoma Research Fund.

Presented in part at the 45th Annual Meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, May 31-June 2, 2009, Orlando, FL, and the 63rd Annual Meeting of the Society of Surgical Oncology, March 3-7, 2010, St Louis, MO.

Authors' disclosures of potential conflicts of interest and author contributions are found at the end of this article.

Clinical trial information can be found for the following: NCT00421811.

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Although all authors completed the disclosure declaration, the following author(s) indicated a financial or other interest that is relevant to the subject matter under consideration in this article. Certain relationships marked with a “U” are those for which no compensation was received; those relationships marked with a “C” were compensated. For a detailed description of the disclosure categories, or for more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to the Author Disclosure Declaration and the Disclosures of Potential Conflicts of Interest section in Information for Contributors.

Employment or Leadership Position: None Consultant or Advisory Role: Merrick I. Ross, Genentech (C), GlaxoSmithKline (C); Douglas S. Tyler, Genentech (C) Stock Ownership: None Honoraria: Jonathan S. Zager, Adherex Technologies; Douglas S. Tyler, Adherex Technologies Research Funding: Douglas S. Tyler, Adherex Technologies Expert Testimony: None Other Remuneration: None

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Georgia M. Beasley, Jonathan C. Riboh, Christina K. Augustine, Jonathan S. Zager, Stephen R. Grobmyer, Richard Royal, Douglas S. Tyler

Financial support: Douglas S. Tyler

Administrative support: Georgia M. Beasley, Christina K. Augustine, Douglas S. Tyler

Provision of study materials or patients: Jonathan S. Zager, Steven N. Hochwald, Stephen R. Grobmyer, Merrick I. Ross,Douglas S. Tyler

Collection and assembly of data: Georgia M. Beasley, Christina K. Augustine, Jonathan S. Zager, Steven N. Hochwald, Stephen R. Grobmyer, Richard Royal, Merrick I. Ross, Douglas S. Tyler

Data analysis and interpretation: Georgia M. Beasley, Jonathan C. Riboh, Christina K. Augustine, Jonathan S. Zager, Steven N. Hochwald, Stephen R. Grobmyer, Bercedis Peterson, Richard Royal, Merrick I. Ross, Douglas S. Tyler

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

REFERENCES

- 1.Balch CM, Houghton AN, Peters LJ. Cutaneous melanoma. In: DeVita VT, Hellman S, Rosenberg SA, editors. Cancer: Principles and Practice of Oncology. ed 4. Philadelphia, PA: JB Lippincott; 1993. pp. 1612–1661. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pawlik TM, Ross MI, Johnson MM, et al. Predictors and natural history of in-transit melanoma after sentinel lymphadenectomy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2005;12:587–596. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2005.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cascinelli N, Bufalino R, Marolda R, et al. Regional non-nodal metastases of cutaneous melanoma. Eur J Surg Oncol. 1986;12:175–180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Calabro A, Singletary SE, Balch CM. Patterns of relapse in 1001 consecutive patients with melanoma nodal metastases. Arch Surg. 1989;124:1051–1055. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1989.01410090061014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zogakis TG, Bartlett DL, Libutti SK, et al. Factors affecting survival after complete response to isolated limb perfusion in patients with in-transit melanoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2001;8:771–778. doi: 10.1007/s10434-001-0771-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sun W, Schuchter LM. Metastatic melanoma. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2001;2:193–202. doi: 10.1007/s11864-001-0033-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hochster H, Strawderman MH, Harris JE, et al. Conventional dose melphalan is inactive in metastatic melanoma: Results of an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Study (E1687) Anticancer Drugs. 1999;10:245–248. doi: 10.1097/00001813-199902000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Skene AI, Bulman AS, Williams TR, et al. Hyperthermic isolated limb perfusion with melphalan in the treatment of advanced malignant melanoma of the lower limb. Br J Surg. 1990;77:765–767. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800770716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grünhagen DJ, de Wilt JH, van Geel AN, et al. Isolated limb perfusion for melanoma patients: A review of its indications and the role of tumour necrosis factor-alpha. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2006;32:371–380. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2006.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vrouenraets BC, Nieweg OE, Kroon BB. Thirty-five years of isolated limb perfusion for melanoma: Indications and results. Br J Surg. 1996;83:1319–1328. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800831004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cornett WR, McCall LM, Petersen RP, et al. Randomized multicenter trial of hyperthermic isolated limb perfusion with melphalan alone compared with melphalan plus tumor necrosis factor: American College of Surgeons Oncology Group Trial Z0020. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4196–4201. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.5152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Taber SW, Polk HC., Jr Mortality, major amputation rates, and leukopenia after isolated limb perfusion with phenylalanine mustard for the treatment of melanoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 1997;4:440–445. doi: 10.1007/BF02305559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thompson JF, Kam PC, Waugh RC, et al. Isolated limb infusion with cytotoxic agents: A simple alternative to isolated limb perfusion. Semin Surg Oncol. 1998;14:238–247. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-2388(199804/05)14:3<238::aid-ssu8>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thompson JF, Waugh RC, Saw RP, et al. Isolated limb infusion with melphalan for recurrent limb melanoma: A simple alternative to isolated limb perfusion. Reg Cancer Treat. 1994;7:188–192. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lindnér P, Doubrovsky A, Kam PC, et al. Prognostic factors after isolated limb infusion with cytotoxic agents for melanoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2002;9:127–136. doi: 10.1007/BF02557363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beasley GM, Petersen RP, Yoo J, et al. Isolated limb infusion for in-transit malignant melanoma of the extremity: A well-tolerated but less effective alternative to hyperthermic isolated limb perfusion. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:2195–2205. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-9988-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beasley GM, Caudle A, Petersen RP, et al. A multi-institutional experience of isolated limb infusion: Defining response and toxicity in the US. J Am Coll Surg. 2009;208:706–715. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2008.12.019. discussion 715-717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Flaherty KT. Chemotherapy and targeted therapy combinations in advanced melanoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12(suppl 7):2366s–2370s. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McDermott DF, Sosman JA, Hodi FS, et al. Randomized phase II study of dacarbazine with or without sorafenib in patients with advanced melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(suppl; abstr 8511):474s. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beasley GM, Tyler DS. Optimizing regional therapy for melanoma. Ann Surg Onc. 2009;16:1095–1097. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0329-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jonker DJ, Stewart R, Goel L, et al. A phase I study of the novel molecularly targeted vascular targeting agent, ExherinTM (ADH-1), shows activity in some patients with refractory solid tumors stratified according to N-cadherin expression. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(suppl; abstr 3038):204s. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sessa C, Perotti A, Maur M, et al. An enriched phase I, pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic study of the N-cadherin (NCAD) cyclic competitive binder exherin (ADH-1) in patients with solid tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(suppl; abstract 3042):131s. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stewart DJ, Jonker DJ, Goel R, et al. Final clinical and pharmacokinetic (PK) results from a phase 1 study of the novel N-cadherin (N-cad) antagonist, Exherin (ADH-1), in patients with refractory solid tumors stratified according to N-cad expression. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(suppl; abstract 3016):124s. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matsuyoshi N, Tanaka T, Toda K, et al. Identification of novel cadherins expressed in human melanoma cells. J Invest Dermatol. 1997;108:908–913. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12292703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hsu MY, Meier FE, Nesbit M, et al. E-cadherin expression in melanoma cells restores keratinocyte-mediated growth control and down-regulates expression of invasion-related adhesion receptors. Am J Pathol. 2000;156:1515–1525. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65023-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Qi J, Chen N, Wang J, et al. Transendothelial migration of melanoma cells involves N-cadherin-mediated adhesion and activation of the beta-catenin signaling pathway. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:4386–4397. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-03-0186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Augustine CK, Yoshimoto Y, Gupta M, et al. Targeting N-cadherin enhances antitumor activity of cytotoxic therapies in melanoma treatment. Cancer Res. 2008;68:3777–3784. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Toshimitsu H, Padussis JC, Turley R, et al. Targeting N-cadherin to augment the efficacy of regional chemotherapy: A potential double- edged sword? Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:S1. abstr 28. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Beasley GM, McMahon N, Sanders G, et al. A phase 1 study of systemic ADH-1 in combination with melphalan via isolated limb infusion in patients with locally advanced in-transit malignant melanoma. Cancer. 2009;115:4766–4774. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Balch CM, Buzaid AC, Soong SJ, et al. Final version of the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging system for cutaneous melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:3635–3648. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.16.3635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sessa C, Perotti A, Maur M, et al. An enriched phase I, pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic study of the N-cadherin (NCAD) cyclic competitive binder exherin (ADH-1) in patients with solid tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(suppl; abstract 3042):131s. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ehrsson H, Eksborg S, Lindfors A. Quantitative determination of melphalan in plasma by liquid chromatography after derivatization with N-acetylcysteine. Chromatogr. 1986;380:222–228. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(00)83648-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yoshimoto Y, Augustine CK, Yoo JS, et al. Defining regional infusion treatment strategies for extremity melanoma: Comparative analysis of melphalan and temozolomide as regional chemotherapeutic agents. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;6:1492–1500. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bayesian Factor Regression Modeling (BFRM 2.0) http://www.stat.duke.edu/research/software/west/bfrm.

- 34a.Eisen MB, Spellman PT, Brown PO, et al. Cluster analysis and display of genome-wide expression patterns. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:14863–14868. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.25.14863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Augustine CK, Jung SH, Sohn I, et al. Gene expression signatures as a guide to treatment strategies for in-transit metastatic melanoma. Mol Cancer Ther. 2010;9:779–790. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-0764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Adherex Technologies: ADH-1 Investigators Brochure, version 7.0. January 18 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 36a.The Gene Ontology Consortium: Gene Ontology: Tool for the unification of biology. Nat Genet. 2000;25:25–29. doi: 10.1038/75556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brady MS, Brown K, Patel A, et al. Isolated limb infusion with melphalan and dactinomycin for regional melanoma and soft-tissue sarcoma of the extremity: Final report of a phase II clinical trial. Melanoma Res. 2009;19:106–111. doi: 10.1097/CMR.0b013e32832985e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McMahon N, Cheng TY, Beasley GM, et al. Optimizing melphalan pharmacokinetics in regional melanoma therapy: Does correcting for ideal body weight alter regional response or toxicity? Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:953–961. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-0288-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]