Abstract

Background: Differences between natives and migrants in average risk for poor self-rated health (SRH) are well documented, which has lent support to proposals for interventions targeting disadvantaged minority groups. However, such proposals are based on measures of association that neglect individual heterogeneity around group averages and thereby the discriminatory accuracy (DA) of the categories used (i.e. their ability to discriminate the individuals with poor and good SRH, respectively). Therefore, applying DA measures rather than only measures of association our study revisits the value of broad native and migrant categorizations for predicting SRH. Design, setting and participants: We analyzed 27 723 individuals aged 18–80 who responded to a 2008 Swedish public health survey. We performed logistic regressions to estimate odds ratios (ORs), predicted risks and the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AU-ROC) as a measure of epidemiological DA. Results: Being born abroad was associated with higher odds of poor SRH (OR = 1.75), but the AU-ROC of this variable only added 0.02 units to the AU-ROC for age alone (from 0.53 to 0.55). The AU-ROC increased, but remained unsatisfactorily low (0.62), when available social and demographic variables were included. Conclusions: Our results question the use of broad native/migrant categorizations as instruments for forecasting individual SRH. Such simple categorizations have a very low DA and should be abandoned in public health practice. Measures of association and DA should be reported together whenever an intervention is being considered, especially in the area of ethnicity, migration and health.

Introduction

Self-rated health (SRH) is a well-established indicator used in epidemiology and public health research.1–3 Numerous studies in European countries have reported that in regard to SRH, most migrant and ethnic minority groups studied appear, on average, to be disadvantaged compared with the majority population.4–10 These observations, together with reports that country of birth differences in SRH seemed to be a strong predictor for subsequent mortality differences,4 have lent support to the idea of using interventions targeting disadvantaged minority groups with the aim of reducing health inequalities.11

A concern with this line of reasoning, however, is that some or even most members of the group with a low average SRH (the so-called ‘disadvantaged’ group) do not have poor SRH, so they would be unnecessarily targeted for intervention. Conversely, many individuals with poor SRH belonging to groups with a good average SRH risk being neglected if interventions solely target disadvantaged groups. This idea can be operationalized using the statistical concept of discriminatory accuracy (DA) that is routinely used to evaluate diagnostic tests and is increasingly being applied to the study of biomarkers and risk factors in epidemiology. The underpinning notion is that, to be useful for clinical medicine and public health, most exposure categories, whether social or biological, need to be robust in their ability to discriminate between persons with and those without the outcome of interest.12

Although extensively applied in some fields of epidemiology, measures of DA are still unusual in public health.13,14 As far as we know, measures of DA have never been explicitly used to interpret associations between migrant groups and a risk of poor SRH. Yet such an interpretation is crucial because if the native/migrant categories commonly used in public health exhibit a low DA, the categories used may be of limited value for understanding health inequalities. In addition, among other possible consequences (e.g. stigmatization), they may offer an inadequate basis for targeted interventions.

With this background, we investigated how well two common categorizations (i.e. native born vs. foreign born, or groups based on their geopolitical region of birth) help us discriminate between persons with poor and good SRH, respectively. For this purpose, we used data from 27 723 individuals aged 18–80 who responded to the 2008 Public Health Survey in Skåne, South Sweden.

Methods

Subjects

The 2008 Public Health Survey for Scania in Sothern Sweden was a postal questionnaire survey based on a stratified non-proportional random sample of the county population that was 18–80 years of age. This cross-sectional survey has been described elsewhere.15 In total 28 198 respondents returned the questionnaire, for a participation rate of 54%. The participation rate was higher among women (58%; n = 15 472) than men (48%; n = 12 726), and higher among those born in Sweden (57%; n = 24 211) than among those born abroad (37%; n = 3987). In the analysis, 472 individuals (1.7%) were excluded because of missing data on the SRH variable. This frequency was lower among native born (1.4%; n = 336) than foreign born (3.4%; n = 136). The survey was performed by Statistics Sweden, which also provided detailed individual level information on socio-economic variables from the administrative registers. The survey was approved by the data safety committee at Statistics Sweden and by the Ethical Committee at Lund University, Sweden.16

Assessment of variables

Outcome variable

SRH was assessed by asking, ‘How do you feel right now, physically and mentally, if you look to your health and your well-being?’ Responses could range between 1 and 7, where 1 was ‘Very bad, could not feel worse’ and 7 was ‘Very well, could not feel better’. The variable was dichotomized by grouping 1–3 as ‘poor’ and 4–7 as ‘good’.

Explanatory variables

We sought to evaluate broad native/migrant categorizations commonly used in public health research and policy.17–19 We classified ‘geopolitical region of birth’ as Sweden, other Nordic countries, other European countries, Africa, Asia, South America, North America or Oceania. As a simpler alternative we dichotomized into ‘native or foreign born’. In both cases, we used native born as the reference in the comparisons.

‘Age’ was divided into five groups (18–34, 35–44, 45–54, 55–64 and 65–80), and we used the group 18–34 years as the reference. ‘Sex’ was either man or woman, and we used men as the reference. We evaluated socio-economic position by assessing the ‘income’ of the participants. This variable was created from registry-based information on equalized disposable family income in 2007 that is weighted for the number of individuals in the household.20 It was also categorized into quintiles based on the income distribution of the participants. We used the first quintile (i.e. the highest income group) as the reference.

Recent public health studies on migration, ethnicity and health, including those studying SRH, have stressed the importance of considering social categories not only distinctly but also in tandem or intersectional (i.e. simultaneously in individuals).21,22 For instance, it is possible that migrant status interacts with sex and/or income so that the risk of poor SRH is much higher in low-income migrant women than in low-income native women. For this reason, we combined the ‘native or foreign born’ and ‘sex’ variables respective the ‘native or foreign born’, ‘sex’ and ‘income’ variables and conducted separate analyses in each case. We used the group of native-born men respective native-born men in the highest income category as the reference. We used ‘native or foreign born’ rather than ‘geopolitical region of birth’ because some of the strata became very small in the latter case.

Statistical analysis

Measures of association

We performed logistic regression to examine the association between native/migrant categories and SRH. To that end, we developed a series of analyses that modelled one variable at the time followed by a set of combined models that adjusted for age and income. We expressed the association by means of odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). From the models, we also obtained the average absolute risk (i.e. predicted probability) of poor SRH for different variable values or combinations of values across age groups.

Analysis of DA

Measures of association are frequently used to gauge the ability of a categorization to predict future outcomes. Yet, it is well known that measures of association alone are inappropriate for such discriminatory purposes.12 The DA of any categorization can be evaluated by calculating the true positive fraction (TPF) (e.g. individuals with poor SRH who are immigrants) and the false positive fraction (FPF) (e.g. individuals with good SRH who are immigrants).

The DA of logistic models that include several variables was evaluated by means of receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis.12 The ROC curve is created by plotting the TPF vs. FPF at various threshold settings of predicted risk obtained from the logistic model. The area under the ROC curve (AU-ROC) or C statistic measures the ability of the model to correctly classify those with and without a certain outcome—in this case, poor SRH. The C statistic assumes a value between 1 and 0.5 where 1 is perfect discrimination and 0.5 would be equally as informative as flipping an unbiased coin. See elsewhere for an extended explanation of these ideas.12,13

In a first series of simple logistic regression models, we calculated the AU-ROCs with 95% CIs of models including age alone or age plus one or more variables. In a second series of logistic regression models, we calculated the AU-ROCs with 95% CIs of models including age and the variable native or foreign born combined either with sex or with sex and income. In both cases, we appraised the incremental value of a model by the difference between AU-ROCs.

We preformed the statistical analysis using SPSS version 21.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL).

Results

Characteristics of the sample and measures of association

As Table 1 shows, 13.9% of the individuals were born outside Sweden, most in other European countries. The overall prevalence of poor SRH was 13.5%, but the prevalence seemed to differ between native or foreign-born groups, as well as between men and women and across income groups.

Table 1.

General characteristic of sample

| Total |

SRH |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Good |

Poor |

|||||

| n | % | n | n | % | ||

| All—by variable | 27 723 | 100 | 23 992 | 86.5 | 3 731 | 13.5 |

| Native or foreign born | ||||||

| Native | 23 870 | 86.1 | 20 905 | 87.6 | 2 965 | 12.4 |

| Foreign | 3 853 | 13.9 | 3 087 | 80.1 | 766 | 19.9 |

| Geopolitical area of birth | ||||||

| Sweden | 23 870 | 86.1 | 20 905 | 87.6 | 2 965 | 12.4 |

| Other Nordic | 843 | 3.0 | 716 | 84.9 | 127 | 15.1 |

| Other European | 1 898 | 6.8 | 1 477 | 77.8 | 421 | 22.2 |

| North America | 78 | 0.3 | 67 | 85.9 | 11 | 14.1 |

| South America | 97 | 0.3 | 78 | 80.4 | 19 | 19.6 |

| Asia | 792 | 2.9 | 626 | 79.0 | 166 | 21.0 |

| Africa | 119 | 0.4 | 102 | 85.7 | 17 | 14.3 |

| Oceania | 9 | 0.03 | 8 | 88.9 | 1 | 11.1 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Men | 12 510 | 45.1 | 10 976 | 87.7 | 1 534 | 12.3 |

| Women | 15 213 | 54.9 | 13 016 | 85.6 | 2 197 | 14.4 |

| Age | ||||||

| 18–34 | 6 115 | 22.1 | 5 301 | 86.7 | 814 | 13.3 |

| 35–44 | 4 700 | 17.0 | 4 037 | 85.9 | 663 | 14.1 |

| 45–54 | 5 042 | 18.2 | 4 277 | 84.8 | 765 | 15.2 |

| 55–64 | 5 582 | 20.1 | 4 784 | 85.7 | 798 | 14.3 |

| 65–80 | 6 284 | 22.7 | 5 593 | 89.0 | 691 | 11.0 |

| Income | ||||||

| Highest quintile | 5 031 | 91.0 | 498 | 9.0 | ||

| 4 957 | 89.7 | 572 | 10.3 | |||

| Middle quintile | 4 726 | 85.5 | 804 | 14.5 | ||

| 4 748 | 85.9 | 781 | 14.1 | |||

| Lowest quintile | 4 462 | 80.7 | 1 067 | 19.3 | ||

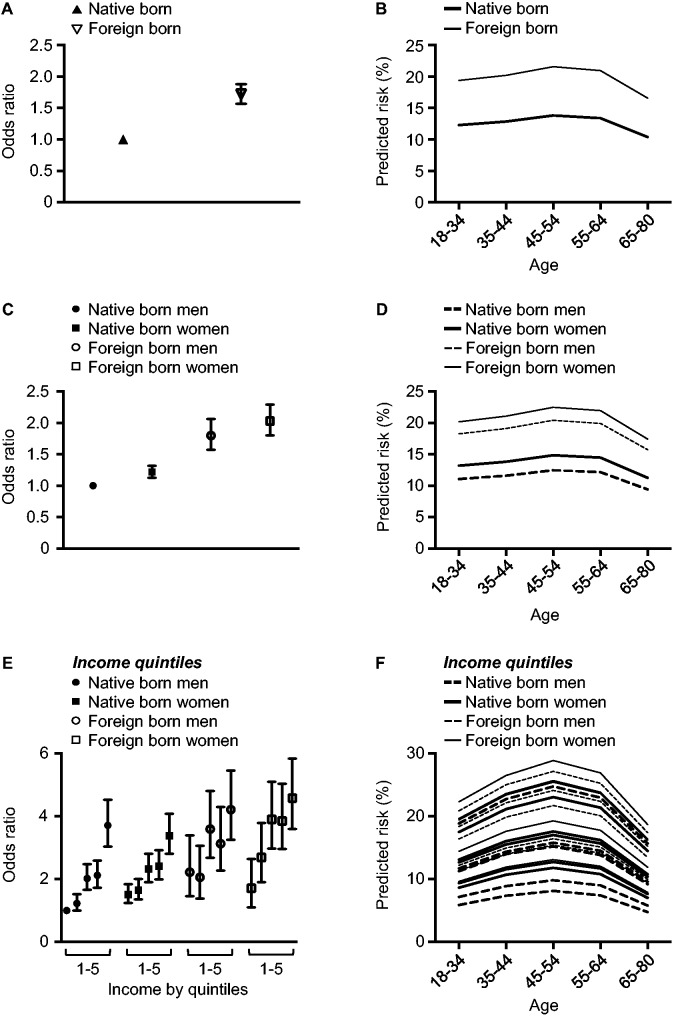

Indeed, being born abroad was associated with higher odds of poor SRH (OR = 1.75, CI 95% 1.60–1.91) (Table 2). The associations remained conclusive after adjustment for age and income (figure 1A and Table 2). This association is also reflected in the difference in predicted probabilities of poor SRH between native or foreign-born individuals (figure 1B). An analysis by geopolitical region of birth suggested that the difference could be due to higher odds of poor SRH in individuals born in non-Nordic European countries and in Asia (Table 2). Moreover, as expected, women had higher odds than men of having poor SRH, and there were conclusive differences across income groups (Table 2).

Table 2.

Measures of association between social and demographic categories and poor SRH

| Un-adjusted model |

Age-adjusted model |

Age- and income- adjusted model |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ORa | CIb 95% | OR | CI 95% | OR | CI 95% | |

| —by variable | ||||||

| Native or foreign born | ||||||

| Native | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Foreign | 1.75 | 1.60–1.91 | 1.72 | 1.57–1.88 | 1.49 | 1.36–1.63 |

| Geopolitical area of birth | ||||||

| Sweden | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Other Nordic | 1.25 | 1.03–1.52 | 1.25 | 1.03–1.52 | 1.07 | 0.88–1.3 |

| Other European | 2.01 | 1.79–2.25 | 1.97 | 1.76–2.22 | 1.76 | 1.57–1.98 |

| North America | 1.16 | 0.61–2.19 | 1.13 | 0.60–2.14 | 1.0 | 0.53–1.91 |

| South America | 1.72 | 1.04–2.84 | 1.67 | 1.01–2.77 | 1.50 | 0.90–2.49 |

| Asia | 1.87 | 1.57–2.23 | 1.80 | 1.51–2.15 | 1.48 | 1.23–1.77 |

| Africa | 1.18 | 0.70–1.97 | 1.14 | 0.68–1.9 | 0.98 | 0.58–1.64 |

| Oceania | 0.88 | 0.11–7.05 | 0.85 | 0.11–6.83 | 0.86 | 0.10–6.73 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Men | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Women | 1.21 | 1.12–1.3 | 1.20 | 1.12–1.29 | 1.15 | 1.07–1.23 |

| Age | ||||||

| 18–34 | 1 | |||||

| 35–44 | 1.07 | 0.96–1.19 | ||||

| 45–54 | 1.17 | 1.05–1.30 | ||||

| 55–64 | 1.09 | 0.98–1.21 | ||||

| 65–80 | 0.81 | 0.72–0.90 | ||||

| Income | ||||||

| Highest quintile | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 1.17 | 1.03–1.32 | 1.18 | 1.04–1.34 | |||

| Middle quintile | 1.72 | 1.53–1.94 | 1.86 | 1.65–2.09 | ||

| 1.66 | 1.48–1.87 | 1.91 | 1.69–2.15 | |||

| Lowest quintile | 2.42 | 2.16–2.71 | 2.87 | 2.55–3.22 | ||

a: odds ratio.

b: confidence interval.

Figure 1.

Age-adjusted ORs and the predicted risk of poor SRH for individuals born in Sweden and abroad, respectively. Panels (A) and (B) show the age-adjusted OR and predicted risk, respectively, for native respective foreign-born individuals. Panels (C) and (D) show the age-adjusted OR and predicted risk, respectively, for native and foreign-born individuals stratified by sex. Panels (E) and (F) show the age-adjusted OR and predicted risk, respectively, for native respective foreign-born individuals stratified by sex and income. Panel (F) is available in colour (Supplementary figure S1)

Combination of the variables native or foreign born and sex showed that in comparison to native-born men, all other groups had higher odds of having poor SRH (figure 1C and D). Combining native or foreign born with sex and income to create 20 different groups resulted in a more complex picture: we observed a socio-economic gradient in both native and foreign-born individuals of either sex, which resulted in major overlap in both ORs and predicted probabilities across these groups (figure 1E and F).

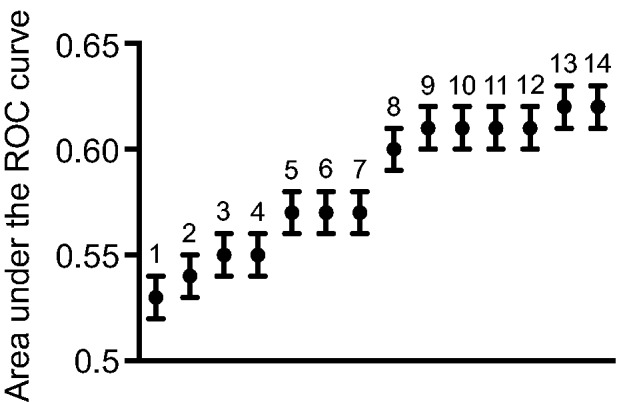

Measures of DA

Despite these statistically significant associations, the DA of the categories studied was very low. In the simplest analysis, where we used ‘foreign born’ to try identifying those with poor SRH, the TPF was only 20.5%. Figure 2 shows the AU-ROCs of models that included age alone or age together with one or more of the explanatory variables. The AU-ROC for age alone was 0.53, which increased only slightly (to 0.55) when information on country or geopolitical area of birth was included. Overall, the performance of both the simple distinction between native and foreign-born and the more refined distinction based on geopolitical area of birth was very poor. Similarly, information on sex did little to improve DA above the model that included age (+0.01) or above the model for age and country or geopolitical area of birth (+0.02). Income was the most informative variable; but the model including age and information on income still reached only an AU-ROC = 0.60. Combination of the variables native or foreign born and sex, or native or foreign born, sex and income did little to further improve the DA. We observed the highest DA (i.e. AU-ROC = 0.62) for the model that included age, sex, income and geopolitical area of birth, and the age-adjusted model in which the variable native or foreign-born was combined with sex and income to create 20 groups. However, this higher DA was mainly due to the income variable.

Figure 2.

AU-ROC curve to assert the DA of different models for SRH. The labels indicate the inclusion of the following variables in models: (1) age; (2) age and sex; (3) age and native or foreign born; (4) age and geopolitical area of birth; (5) age, sex and native or foreign born; (6) age, sex and geopolitical area of birth; (7) age and native or foreign born stratified by sex; (8) age and income; (9) age, income and native or foreign born; (10) age, income and geopolitical area of birth; (11) age, income and sex; (12) age, income, sex and native or foreign born; (13) age, income, sex and geopolitical area of birth and (14) age and native or foreign born stratified by sex and income

Discussion

Average differences in the risk of poor SRH between migrants or ethnic minorities and the majority populations are well documented.4–9,11,23,24 Our study provides additional evidence for the existence such differences. From a public health perspective, uncovering differences between groups may serve as a first step in a series of studies and policy discussions regarding reduction of health inequalities. However, the low DA of the broad categories used in this study renders the observed average differences of little public health value as a solid basis for planning public health interventions in this area. Importantly, the analytical discriminatory approach we applied is identical to the standard for evaluating biomarkers and diagnostic tests. In both cases, justification for use of biomarkers or diagnostic tests in clinical medicine and public health is based not on differences in average outcomes, but on their ability to discriminate cases from non-cases. Here, we extended this approach to the evaluation of broad native/migrant categories in public health. This approach is equally relevant for evaluating ethnic, socio-economic, demographic and geographical categories.13,14

In the past, on the basis of average differences, many authors have suggested that information on ethnicity or country of birth offers a solid basis for selective public health intervention (e.g. selective health education, free doctor consultations).5,8,24 Such proposals seem to be motivated by a genuine concern with the poor SRH of deprived groups. However, a limitation with this interventionist approach is that many individuals will be incorrectly considered at risk of poor health, and perhaps be targeted for intervention. Consistent with this concern, we found that information on individuals’ country or region of birth was of very limited value for forecasting SRH, in our sample (figure 2). This low DA is explained by the high degree of intra-individual heterogeneity and overlap in ‘ethnic’ composition between groups of poor and good SRH, respectively. As argued elsewhere,13 failure to consider the DA of an association may result in a probabilistic interpretation of risk that misleadingly attributes the average value of a group to all individuals of that group.25,26 The key concept is that common measures of association correspond to abstractions that do not represent the heterogeneity of individual effects.

There is substantial heterogeneity in health among immigrants,8,9,11,24,27 and the same is undoubtedly true for natives, although this is much less frequently emphasized. Faced with evidence of heterogeneity among immigrants, some researchers resort to dissociating this category and carry out separate analyses for different minority groups. Unfortunately, this does not solve the problem of poor DA. Thus, the OR reported in such analyses, typically between 1 and 3,11 but occasionally as high as 10 for some sub-groups,8 indicate substantial heterogeneity within groups and overlap with the reference group.12 What we normally consider a strong association between an exposure and an outcome (e.g. OR for a disease of 10) is related to a rather low capacity of the exposure to discriminate cases and non-cases.12 In order to obtain a suitable DA of, for example, TPF = 90% and a FPF =5%, we would need an OR = 176,12 that is, of a magnitude rarely seen in public health research.

Despite the high degree of intra-individual heterogeneity and overlap between groups, the current thrust in public health is to stress diversity between ethnic groups or groups based on country of birth.28,29 Such approaches have sought to stratify the general population into ‘ethnic’ units, but failed to offer any justification for the value of these ‘ethnic’ units other than the presence of average group differences. Likely, most students of ethnic or country of birth differences in health would reject the biological concept of human races because of the large genetic diversity within groups and continuous overlap between groups despite average differences in allele frequencies.30,31 However, they apparently fail to apply such ideas to their own research. A conceptual recalibration is needed that focuses not primarily on average group differences but on the structure of inter-individual heterogeneity in the entire population. Methodologically, conceptual recalibration would require complementing measures of average association with appropriate statistical approaches that are focused on the interpretation of inter-individual diversity (i.e. variance).14 Such approaches are already being applied in other areas, for example, in multilevel studies in social epidemiology to investigate contextual effects.13,32,33 They are also being applied within population genetics to investigate the structure of genetic variation within and among populations.34 In the latter case, such global measures of variation underpin the refutation of the biological concept of human races.35

Finally, it is pertinent to remember that DA is not the only information to consider when assessing the possibilities for intervention. Under certain circumstances, DA can be low but a targeted intervention may be still recommended. For example, the DA of an infection on disease may be low because of the many false positives (i.e. many are exposed but few contract the disease). But immunization could still be recommended for certain groups (e.g. children or elderly) because the medical and social adverse effects of vaccination are expected to be mild compared with the major gains. However, intervening solely on the basis of a person’s ethnicity or country of birth is, for social and political reasons, likely to be much more problematic. Categories based on ethnicity or country of birth are socially and politically charged and targeting individuals of specific ethnic or migrant groups might be experienced as coercive and stigmatizing despite the opposite intention.36,37 Caution is particularly required when there are many ‘false positives’ and/or the intervention is not particularly effective (i.e. unlike vaccination), because the positive medical effects are then unlikely to outweigh the adverse social effects. However, some interventions may nonetheless be acceptable under such circumstances, such as offering medical information in various languages, preventing discrimination through legislation and policies, and educating health professionals about migration processes and discrimination. These interventions do not target individual immigrants or members of specific ethnic groups, and hence the risk of coercion and stigma is lower. The low DA of social categories for SRH suggests the need for more policies that target the general population, for example, by increasing access to good health care indiscriminately throughout society.

Limitations

Being a cross-sectional postal questionnaire survey with self-reported information, our study has several weaknesses. Among these it should be stressed that, overall, the response rate was relatively low (54%), especially among the foreign born (37%). In addition, the frequency of missing values was higher among the foreign born (3.4% vs. 1.4%). However, the foreign born group was underrepresented by merely 4% units compared with the official register statistics.16 Furthermore, the distribution of demographic and social variables in our study was similar to that of the Public Health Survey conducted in Skåne in 2000. This is in turn was similar to those in the official population registers.16 Therefore, the risk of selection bias does not seem to be a major limitation. It should also be noted that the survey was based on stratified non-proportional random sample. However, we performed a weighted analysis and the results were very similar. A further limitation is the loss of information caused by the dichotomization of the SRH variable. However, varying the cut-off for ‘poor’ and ‘good’ SRH or modelling the original seven categories of SRH by ordinal logistic regression did not change the interpretation of results (not shown).

The literature on ethnic or country of birth differences in SRH displays a mix of ethnic and migrant categorizations, underscoring that no consensus exists on what categories to use. In some countries such as Sweden, Denmark and the Netherlands, country of birth is most commonly used as an indicator of immigrant category or ethnicity. In the UK, in contrast, self-identification is most commonly used.11 Because the purpose of this study was to evaluate regularly used categories,17–19 such as native and foreign born, we used a simple distinction based on country or geopolitical region of birth. Admittedly, native and foreign born are heterogeneous categories, but so are many of the other ethnic or migrant categories currently used.11 Rather than seeing this issue as a methodological weakness in our study, we consider it as an asset; indeed, the main conclusion of this study is that broad native and migrant categorizations have a very low DA for SRH and, therefore, are inappropriate as a basis for planning public health interventions in this area. This does not preclude the possibility of other ethnic or migrant categorizations having a higher DA, or that such categorizations are more relevant for predicting other outcomes, but to our knowledge such a case awaits empirical confirmation.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at EURPUB online.

Key points

We applied measures of DA rather than only measures of association to revisit the value of using broad native and migrant categories for predicting SRH.

The DA of broad native and migrant categories was very low despite average differences in the risk of poor SRH between migrants and the majority population.

The very low DA of broad native and migrant categories shows that these categories are of no value as instruments for forecasting individuals’ SRH in the present context. They also provide an inadequate basis for targeted interventions.

We suggest that measures of DA should become standard for evaluating social categories as basis for social and medical intervention in public health.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Swedish Research Council (VR) [2013-2484 to J.M.] and [2013-1695 to S.M. and A.B.], and the Public Health Unit at Scania County Council (Region Skåne). We express our gratitude to Philippe Wagner for statistical revision of the final version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Kaplan GA, Goldberg DE, Everson SA, et al. Perceived health status and morbidity and mortality: evidence from the Kuopio Ischaemic heart disease risk factor study. Int J Epidemiol 1996;25:259–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.DeSalvo K, Bloser N, Reynolds K, et al. Mortality prediction with a single general self-rated health question. J Gen Intern Med 2006;21:267–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Idler EL, Benyamini Y. Self-rated health and mortality: a review of twenty-seven community studies. J Health Soc Behav 1997;38:21–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lindström M, Sundquist J, Östergren PO. Ethnic differences in self reported health in Malmö in southern Sweden. J Epidemiol Community Health 2001;55:97–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wiking E, Johansson S-E, Sundquist J. Ethnicity, acculturation, and self reported health. A population based study among immigrants from Poland, Turkey, and Iran in Sweden. J Epidemiol Community Health 2004;58:574–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sungurova Y, Johansson S-E, Sundquist J. East—west health divide and east—west migration: self-reported health of immigrants from Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union in Sweden. Scand J Public Health 2006;34:217–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kulla GE, Ekman S-L, Heikkilä AK, Sarvimäki AM. Differences in self-rated health among older immigrants—a comparison between older Finland-Swedes and Finns in Sweden. Scand J Public Health 2010;38:25–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dinesen C, Nielsen S, Mortensen L, Krasnik A. Inequality in self-rated health among immigrants, their descendants and ethnic Danes: examining the role of socioeconomic position. Int J Public Health 2011;56:503–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Villarroel N, Artazcoz L. Heterogeneous patterns of health status among immigrants in Spain. Health Place 2012;18:1282–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moullan Y, Jusot F. Why is the ‘healthy immigrant effect’ different between European countries? Eur J Public Health 2014;24:80–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nielsen S, Krasnik A. Poorer self-perceived health among migrants and ethnic minorities versus the majority population in Europe: a systematic review. Int J Public Health 2010;55:357–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pepe MS, Janes H, Longton G, et al. Limitations of the odds ratio in gauging the performance of a diagnostic, prognostic, or screening marker. Am J Epidemiol 2004;159:882–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Merlo J. Invited commentary: multilevel analysis of individual heterogeneity—a fundamental critique of the current probabilistic risk factor epidemiology. Am J Epidemiol 2014;180:208–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Merlo J, Wagner P. The tyranny of the averages and the indiscriminate use of risk factors in public health: a call for revolution. Eur J Epidemiol 2013;28(Suppl. 1):148. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosvall M, Grahn M, Modén B, Merlo J. Hälsoförhållanden i Skåne: Folkhälsoenkät Skåne 2008 [Health Conditions in Scania: Scania Public Health Survey 2008]. Malmö, Region Skåne, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lindstrom M, Hansen K, Rosvall M. Economic stress in childhood and adulthood, and self-rated health: a population based study concerning risk accumulation, critical period and social mobility. BMC Public Health 2012;12:761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Joshi S, Jatrana S, Paradies Y, Priest N. Differences in health behaviours between immigrant and non-immigrant groups: a protocol for a systematic review. Syst Rev 2014; 3:61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Malmusi D. Immigrants’ Health and Health Inequality by Type of Integration Policies in European Countries. Eur J Public Health 2015;25:293–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare. Social Report, 2010. Available at: http://www.socialstyrelsen.se/lists/artikelkatalog/attachments/17957/2010-3-11.pdf. (20 January 2015 last accessed date).

- 20.Statistics Sweden. Disponibel inkomst per konsumtionsenhet för hushåll 20–64 år efter hushållstyp 2012 [Disposable income per unit of consumption for households, age 20–64 by household in 2012]. Available at: http://www.scb.se/sv_/Hitta-statistik/Temaomraden/Jamstalldhet/Indikatorer/Ekonomisk-jamstalldhet/Inkomster-och-loner/Disponibel-inkomst-per-konsumtionsenhet-for-hushall-20-64-ar-efter-hushallstyp-2011/. (1 September 2014, date last accessed).

- 21.Veenstra G. Race, gender, class, and sexual orientation: intersecting axes of inequality and self-rated health in Canada. Int J Equity Health 2011;10:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hankivsky O. Women’s health, men’s health, and gender and health: implications of intersectionality. Soc Sci Med 2012;74:1712–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cooper H. Investigating socio-economic explanations for gender and ethnic inequalities in health. Soc Sci Med 2002;54:693–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vaillant N, Wolff FC. Origin differences in self-reported health among older migrants living in France. Public Health 2010;124:90–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tabery J. Commentary: Hogben vs the Tyranny of averages. Int J Epidemiol 2011;40:1454–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Downs GW, Rocke DM. Interpreting heteroscedasticity. Am J Pol Sci 1979;23:816–28. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Argeseanu Cunningham S, Ruben JD, Venkat Narayan KM. Health of foreign-born people in the United States: a review. Health Place 2008;14:623–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stronks K, Wieringa N, Hardon A. Confronting diversity in the production of clinical evidence goes beyond merely including under-represented groups in clinical trials. Trials 2013;14:177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stronks K, Snijder M, Peters R, et al. Unravelling the impact of ethnicity on health in Europe: the HELIUS study. BMC Public Health 2013;13:402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roux AVD. Conceptual approaches to the study of health disparities. Annu Rev Public Health 2012;33:41–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barbujani G, Ghirotto S, Tassi F. Nine things to remember about human genome diversity. Tissue Antigens 2013;82:155–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Merlo J, Asplund K, Lynch J, et al. Population effects on individual systolic blood pressure: a multilevel analysis of the World Health Organization MONICA project. Am J Epidemiol 2004;159:1168–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Merlo J, Ohlsson H, Lynch KF, et al. Individual and collective bodies: using measures of variance and association in contextual epidemiology. J Epidemiol Community Health 2009;63:1043–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Holsinger KE, Weir BS. Genetics in geographically structured populations: defining, estimating and interpreting FST. Nat Rev Genet 2009;10:639–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lewontin RC. The apportionment of human diversity. Evol Biol 1972;6:381–98. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bredström A. Sweden: HIV/AIDS policy and the ‘crisis’ of multiculturalism. Race Class 2009;50:57–74. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sheldon TA, Parker H. Race and ethnicity in health research. J Public Health Med 1992;14:104–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]