Abstract

Over the past fifteen years, an inter-connected set of regulatory reforms, known as Better Regulation, has been adopted across Europe, marking a significant shift in the way European Union (EU) policies are developed. There has been little exploration of the origins of these reforms, which include mandatory ex-ante impact assessment. Drawing on documentary and interview data, this paper discusses how and why large corporations, notably British American Tobacco (BAT), worked to influence and promote these reforms. Our analysis highlights: (i) how policy entrepreneurs with sufficient resources (such as large corporations) can shape the membership and direction of advocacy coalitions; (ii) the extent to which ‘think tanks’ may be prepared to lobby on behalf of commercial clients; and (iii) why regulated industries (including tobacco) may favour the use of ‘evidence-tools’, such as impact assessments, in policymaking. We argue a key aspect of BAT’s ability to shape regulatory reform involved the deliberate construction of a vaguely defined idea that could be strategically adapted to appeal to diverse constituencies. We discuss the theoretical implications of this finding for the ‘Advocacy Coalition Framework’, as well as the practical implications of the findings for efforts to promote ‘transparency’ and public health in the EU.

Introduction

Since the early 1990s, the concept of ‘Better Regulation’ has been increasingly used to describe a rolling programme of regulatory reform taking place at both European Union (EU) (Allio, 2007; Commission of the European Communities, 2009) and European Member State level (Radaelli, 2005; Radaelli and Meuwese, 2010; Department for Business, Enterprise & Regulatory Reform, 2007; Better Regulation Task Force, 2005; Department of the Taoiseach, 2004). Despite shifting interpretations of the term (Radaelli, 2007a), it is possible to identify three core themes within Better Regulation discourses. First, the term is associated with an imperative to improve the quality of regulatory decision-making, notably through the increased use of evidence (Department for Business, Enterprise & Regulatory Reform, 2007; Department of the Taoiseach, 2004). Second, there is often a particular focus on the impacts of regulation on business competitiveness (Commission of the European Communities, 2005; Department of the Taoiseach, 2004; EU Presidencies, 2004). Regulatory Impact Assessment (a form of Business Impact Assessment) is frequently advocated as a means of addressing these first two strands (Radaelli, 2007b; Carroll, 2010). Third, the principles of Better Regulation are often framed as a means of achieving a ‘simplified’ regulatory environment (Department for Business, Enterprise & Regulatory Reform, 2007; Commission of the European Communities, 2002; Department of the Taoiseach, 2004), in which ‘self-regulation’ and ‘co-regulation’ are promoted as alternatives to traditional legislation (Commission of the European Communities, 2002; Department of the Taoiseach, 2004; EU Presidencies, 2004). Finally, Better Regulation is associated with a commitment to transparency and dialogue (Better Regulation Task Force, 2005; Commission of the European Communities, 2002; Department of the Taoiseach, 2004; EU Presidencies, 2004).

The roots of Better Regulation in the EU date back to the 1980s, when European Community policymakers formally began to link a reduction of regulatory costs to business competitiveness and economic growth (e.g. Commission of the European Communities, 1986a, 1986b). The UK was the first EU Member State to formally adopt the term, using it widely in documents from 1997 onwards (e.g. Cabinet Office, 1997; Department for Business, Enterprise & Regulatory Reform, 2007). However, it was not until 2000 that a comprehensive and politically visible Better Regulation agenda was conceived at the EU level (Allio, 2007). To date, there have been few empirical analyses of the origins of Better Regulation in the EU. Radaelli (2007b) claims it emerged from concerns amongst some Member States (particularly the UK) about the quality and quantity of EU regulations and constituted an attempt by these member states to control the European Commission; Renda (2006, p.43) attributes its development to concerns about ‘regulatory creep’ and ‘disappointing economic performance’; Allio (2007; see Table 2) traces its origins to a growing concern amongst European policymakers that foreign direct investment might shift to jurisdictions with lower regulatory costs; and Löfstedt (2006) points to the influence of US political and economic institutions.

Table 2.

Key Individuals involved in the construction and promotion of ‘Better Regulation’

| Name of individual | In tobacco industry documents? | Interviewed? | Role / description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lorenzo Allio | No (but in related documents) | No – declined request. | In charge of the Better Regulation programme at the EPC (see Table 1) between 2002 and 2006 (Kirkpatrick & Parker, 2007), Allio began working for the European Risk Forum (2012) when it left the EPC to establish itself as an independent think tank. |

| Bruce Ballantine | Yes. | No - deceased. | Worked as an advisor to the EPC from the mid-1990s (Crossick, 1997) until his death in 2005 (EPC Risk Forum, 2005). |

| Stuart Chalfen | Yes. | No – unable to identify contact details. | Joined BAT as a solicitor in 1988 (BIICL, Undated); remained there until his retirement in 2000 (BIICL, undated). According to Crossick, he and Chalfen had been friends since Chalfen ‘was a teenager’ and had previously worked together, which is one reason Chalfen approached Crossick to discuss regulatory reform (interview with Stanley Crossick, September 18th 2008). |

| David Clark MP | Yes. | No - did not respond to request. | Appointed as a ‘Political Advisor’ to BAT Chairman’s Policy Committee in 1992 (BAT, 1992). By the time Labour won the 1997 General Election, Clark was not only aware of BAT’s interest in Business IA but supportive of the company and, in 1995, reportedly offered to lobby MPs on BAT’s behalf (Opukah, 1995). Between 3rd May 1997 and 27th July 1998, Clark was responsible for regulatory reform in the UK. Clark supported BAT and the EPC’s proposal that the UK Presidency of the EU should sanction a conference on risk and regulation in April 1998 ([BAT], 1997a; Anonymous, 1998a; Clark, 1997). Clark apparently invited Bruce Ballantine (of EPC) onto key groups advising on regulatory reforms, including a Task Force on ‘Open Government’ (Anonymous, 1997). |

| Stanley Crossick | Yes. | Yes. | A corporate lawyer from the UK who set up his own law firm in Brussels in 1977 and later went on to found the think tank, EPC (see Table 1) (Anonymous, 1998). Crossick (who died in 2010) was described in the Economist as the ‘grandfather’ of lobbying in Brussels (Anonymous, 1998). |

| Dirk Hudig | Yes. | No but did engage in email exchange. | Joined Imperial Chemicals Industries in 1970, becoming Group Manager of EU Government Relations from 1987–1998. Left to become Secretary General of UNICE (now BusinessEurope) until 2001. Joined one of ‘Europe’s leading communications consultancy specializing in advice on political and regulatory issues’ (FIPRA, 2005). Involved in BAT’s Better Regulation campaign from 1997 onwards (Anonymous, 1997, [BAT], 1997b; Chalfen, 1997) and is currently Chair of the European Risk Forum Table 1). |

| Charles Miller | Yes. | Yes. | A UK based lobbyist who worked for the Public Policy Unit from 1985 onwards and was involved in IMPACT. Coordinated the Fair Regulation Campaign (Miller, 1999; see Table 1). |

| Christopher Proctor | Yes. | Not approached. | A senior research scientist at BAT during the 1980s (Boyse & Proctor, 1990), Proctor worked for Covington & Burling 1991–1994 (Thornton, 1990), before returning to BAT (Proctor, 1994). Asked by a colleague, Chalfen (see above), to produce an overview of Philip Morris’ approach to regulatory issues (Chalfen, 1995; Proctor, 1995). |

References for Table 2:

Anonymous. 1997. Cost Benefit Analysis and Risk Assessment Working Group (Bates number(s): 700513505-700513514). Source: BAT. URL: http://bat.library.ucsf.edu//tid/ggj23a99 (accessed 30 May 2008).

Anonymous. 1998. Managing Risk: A Balancing Act. (Bates number(s): 321574681-321574686). Source: BAT. URL: http://bat.library.ucsf.edu//tid/ang63a99 (accessed 30 May 2008).

[BAT]. 1997a. Conference Evaluation Risk: A Balancing Act (Bates number(s): 321573216-321573217). Source: BAT. URL: http://bat.library.ucsf.edu//tid/ofg63a99 (accessed 19 Jun 2008).

[BAT]. 1997b. Cost Benefit Analysis and Risk Assessment Working Group (Note of Meeting Oct 1997) (Bates number(s): 321573259-321573260). Source: BAT. URL: http://bat.library.ucsf.edu//tid/cgg63a99 (accessed 03 Jun 2008).

BAT 1992. Dr David G Clark, MP: Lunch - 24th April. (Bates number(s): 322049550). Source: BAT. URL: http://bat.library.ucsf.edu//tid/dfw80a99 (accessed 18 Jun 2008).

BIICL (British Institute of International and Comparative Law). Undated. Stuart Chalfen Biography and Achievements. London: http://www.biicl.org/files/2630_stuartchalfen.pdf (accessed 16 Oct 2012).

Boyse, Sharon and Proctor, Christopher. 1990. The Environment Committee: Examination of Witnesses (Bates number(s): 401696968-401696978). Source: BAT. URL: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/bpn02a99 (accessed 23 Jan 2009).

Chalfen, Stuart. 1997. Letter from Stuart Chalfen to DF Hudig regarding CBA and risk management (Bates number(s): 321573148-321573149). Source: BAT. URL: http://bat.library.ucsf.edu//tid/cgf61a99 (accessed 04 Jun 2008).

Chalfen, Stuart. 1995. Note from Stuart Chalfen to Chris Proctor regarding the meeting on risk assessment (Bates number(s): 503098366). Source: BAT. URL: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/wqf00a99 (accessed 23 Jan 2009).

Crossick, Stuart. 1997. CBA. (Bates number(s): 321573181). Source: BAT. URL: http://bat.library.ucsf.edu//tid/efg63a99 (accessed 04 Jun 2008).

EPC Risk Forum. 2005. Enhancing the role of science in the decision-making of the European Union (EPC Working Paper 17). Brussels http://www.epc.eu/TEWN/pdf/668109152_EPC%20Working%20Paper%2017%20Enhancing%20the%20role%20of%20science%20in%20EU%20decision%20making%20(revised).pdf (accessed 25 Aug 2008): The European Policy Centre.

European Risk Forum. 2012. European Risk Forum - Structure. Brussels: http://www.riskforum.eu/executive_committee.php (accessed 16 October 2012).

FIPRA. 2005. Who We Are. http://www.fipra.com/doc.php?subject_id=2 (accessed 22 Jun 09): FIPRA.

Kirkpatrick, Colin and Parker, David. 2007. Regulatory Impact Assessment – Towards Better Regulation? The CRC Series on Competition, Regulation and Development. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Miller, Charles. 1999. Fair Regulation Campaign - Formation of Campaign Group. (Bates number(s): 321332619-321332621). Source: BAT. URL: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/yuy23a99 (accessed 28 Jul 2008).

Opukah, Shabanji. 1995. Panos Communication. (Bates number(s): 502601078). Source: BAT. URL: http://bat.library.ucsf.edu//tid/nqw24a99 (accessed 19 Jun 2008).

Proctor, Christopher. 1994. ETS Consultants Programme (Bates number(s): 500830807). Source: BAT. URL: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/wph10a99 (accessed 20 Jan 2009).

Proctor, Christopher. 1995. Regulatory Affairs at Phillip Morris (Bates number(s): 500820183-500820192). Source: BAT. URL: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/xll04a99 (accessed 23 Jan 2009).

Thornton, Ray E. 1990. Letter from RE Thornton to TD Sterling regarding discussion on budget (Bates number(s): 300549944). Source: BAT. URL: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/gdq28a99 (accessed 13 Jan 2009).

Of the various innovations to emerge from the Better Regulation agenda, the mandatory requirement for EU policymakers to undertake impact assessments (IAs) for virtually all policy decisions is perhaps the most significant and is widely interpreted as constituting an important shift in regulatory policymaking (Allio, 2007; Radaelli & Meuwese, 2008; Radaelli & Meuwese, 2010). In general terms, IA is a means of assessing the impacts of a potential (or existing) policy (Curtis, 2008; Mindell et al, 2004; Radaelli, 2008) but specific definitions vary (e.g. Löfstedt, 2004; Parry and Kemm, 2005; Radaelli, 2005; 2007b) and IA tools differ across policy contexts (Radaelli, 2005). A multitude of IA types now exist, including Business IAs, Health IAs and Environmental IAs. When applied to the regulation of substances which pose threats to human health and/or the environment, such as tobacco, alcohol or toxic chemicals, IA provides a framework for making decisions about whether and how to limit the resulting health and/or environmental damage (Michaelson, 1996). The first stage of IA usually involves some form of risk assessment in order to assess whether the risks posed by a particular hazard are great enough to warrant regulation (Curtis, 2008; Kopp et al, 1997; Majone, 2003). If policy intervention is deemed necessary, the likely impacts of each policy option may then be assessed in a process similar to cost-benefit analysis (CBA), which involves assessing policy options by quantifying the value of positive and negative impacts in quantitative (usually monetary) terms. The theory underlying CBA is that this process helps ‘effective social decision making through efficient allocation of society’s resources when markets fail’ (Boardman et al., 2006, p23).

IA and CBA are widely regarded as useful decision-making aids and their use within policymaking is supported by business organisations (e.g. BusinessEurope, undated) and academics (e.g. Hahn and Litan, 1997; Kopp et al, 1997; Sunstein, 2002). The use of particular forms of IA within policymaking, notably Health IAs and Environmental IAs, has also been promoted by researchers and advocates concerned with public health and environmental debates (e.g. British Medical Association, 1999; McCarthy et al, 2002; Mindell and Joffe, 2003; Wright et al, 2005). There are, however, a number of critiques of IA and CBA, some of which raise questions about their political neutrality (e.g. Chichilnisky, 1997; Driesen, 2006; Kelman, 1981; Michaelson, 1996; Sen, 2000). A key concern is the difficulty in accurately predicting ex-ante impacts and the risk that IA may provide policymakers with a misleading sense of certainty about the consequences of particular decisions (e.g. Tennøy et al., 2006). These risks are perhaps greatest where IAs attempt to quantify relative costs and benefits in monetary terms and where non-market goods, such as health and environmental impacts, are involved (Michaelson, 1996; Sen, 2000). Quantification in these circumstances can obscure and oversimplify what are, in effect, highly complex and contested issues involving moral judgments and decisions about competing political priorities (Kelman, 1981; O’Connell and Hurley, 1997; Miller and Patassini, 2005). Another concern that has been raised is that the time-consuming nature of producing IAs can lead to significant legislative delays (Driesen, 2006; Krieger et al, 2003). Finally, IAs can increase policymakers’ informational dependency on resource-rich stakeholders with commercial interests in socially suboptimal policy outcomes (Smith et al., 2010). Given the opportunities that these complexities open up for different interests, it seems important to explore which actors worked to promote Better Regulation and the use of IA within the EU, how they tried to shape these agendas and what they hoped to achieve as a result.

The following account begins with a brief explanation of the methods employed and the theoretical approach, before explaining the particular interest of British American Tobacco (BAT) in Better Regulation and IA within Europe. After this, the paper presents a largely chronological account of the findings, explaining what kinds of policy change BAT managers hoped to achieve, why they believed these changes would benefit the company, and how they worked with others, notably a Brussels-based think tank called the European Policy Centre (EPC - see Table 1), to try to achieve these changes. Specifically, we explore whether the vaguely defined nature of ‘Better Regulation’ reflects BAT’s strategic approach to promoting regulatory reform in the EU. The concluding discussion considers the appropriateness of IA as a tool for practical decision-making, the limits of current ‘transparency’ initiatives in the EU and the theoretical implications of our findings for Sabatier and Jenkins-Smith’s (1999) widely-employed ‘Advocacy Coalition Framework’.

Table 1.

Key Organisations involved in the construction and promotion of ‘Better Regulation’

| Name of organisation | Type of organisation | Role / description |

|---|---|---|

| Charles Barker | Consultancy | A UK based firm that provided an early analysis for BAT of how the company might pursue a requirement for Risk Assessment guidelines (MacKenzie-Reid, 1995). |

| Covington & Burling | Legal | An international legal firm regularly used by large tobacco companies (Ong & Glantz, 2001), which had been involved in Philip Morris’ campaign to promote risk assessment in the US (Hirschhorn & Bialous, 2001; Ong & Glantz, 2001). |

| European Policy Centre | Think tank | A large Brussels-based think tank, established by Stanley Crossick and others in the early 1990s (Sherrington, 2000). Originally known as Belmont European Policy Centre (Crossick, Undated), it was re-branded ‘European Policy Centre’ in 1997–8 (Crossick, Undated; Sherrington, 2000). Describes itself as ‘progressing a range of business friendly policies’ (Watson, 1998), and described by the Corporate Europe Observatory (1998) as ‘nothing more than [a] corporate front group’. |

| Fair Regulation Campaign | Consultancy-led campaign | A campaign group promoting Business IA (effectively a coalition of companies, including BAT – see Figure 1) formed in 1999 and led by the CBI, Institute of Directors and Federation of Small Business, for which Charles Miller, of the Public Policy Unit (see below), was Secretary/Director. The Fair Regulation Campaign was subsequently merged into the European Policy Forum, where this work continued as part of a Better Government Initiative (since moved to the Regulatory Policy Institute in Oxford according to Charles Miller in our interview with him on 27th August 2008). |

| IMPACT | Consultancy | An arm of the Public Policy Unit (see below), IMPACT specifically promoted Business IA as a means by which businesses could influence and challenge legislation, offering to undertake and advise companies accordingly (IMPACT, 1995). |

| Public Policy Unit | Consultancy | A UK based consulting firm that BAT employed the services of in its attempts to influence Business IA and risk assessment in the UK (Binning, 1996; Miller, 1995). |

| Risk Forum | Think tank | An invitation-only group that BAT and Stanley Crossick (Table 2) established within EPC. While a number of NGOs were members of the EPC, they were specifically excluded from this Forum (personal communication with Hans Martens, Chief Executive of the EPC from 2002 until present), resulting in the Forum being asked to leave the EPC in 2007. It subsequently established itself as an independent think tank, known as the European Risk Forum (European Risk Forum, 2009). Dirk Hudig (Table 2) is its current Chairman and Lorenzo Allio (Table 2) works as a ‘Senior Policy Analyst’ (European Risk Forum, 2012). |

| Weinberg Group | Consultancy | A multinational ‘scientific and regulatory consulting firm’ which helps ‘companies resolve complex issues surrounding science, management, law and regulation’, the Weinberg Group has an office in Brussels (as well as in the US and UK) (Weinberg Group, 2009). |

References for Table 1:

Binning, Kenneth. (1996). Risk Assessment and all that. (Bates number(s): 800102512). Source: BAT. URL: http://bat.library.ucsf.edu//tid/ghf14a99 (accessed 08 Jul 2008).

Corporate Europe Observatory (2001). “Better Regulation” - For Who? EC Prepares to Dismantle Business Regulation and Expand Corporate Control. URL: http://archive.corporateeurope.org/observer9/regulation.html#14 (accessed 19 May 2010).

Crossick, Stanley. (Undated). Stanley Crossick - CV. URL: http://www.ceibs.edu/forum/2002/1202_crossick_cv.html (accessed 15th April 2009).

European Risk Forum. (2009). European Risk Forum. Brussels: http://www.euportal2.be (accessed 15 Apr 2009).

European Risk Forum. (2012). European Risk Forum - Structure. Brussels: http://www.riskforum.eu/executive_committee.php (accessed 16 October 2012).

Hirschhorn, Norbert and Bialous, Stella A. (2001). Second hand smoke and risk assessment: what was in it for the tobacco industry? Tobacco Control 10 375–382.

IMPACT. (1995). Impact Assessments: Changing the Way Business Deals with Government. (Bates number(s): 800103160-800103167). Source: BAT. URL: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/fjf14a99 (accessed 24 Jul 2008).

MacKenzie-Reid, Duncan. (1995). Memo from Duncan MacKenzie-Reid to Keith Gretton enclosing paper on risk assessment. (Bates number(s): 800147230-800147236). Source: BAT. URL: http://bat.library.ucsf.edu//tid/ctt72a99 (accessed 12 Jul 2008).

Miller, Charles. (1995). Letter from Charles Miller to Heather Honour regarding risk assessment bibliography. (Bates number(s): 800152702-800152704). Source: BAT. URL: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/mjj23a99 (accessed 30 Jul 2008).

Ong, Elisa K., & Glantz, Stanton A. (2001). Constructing ‘sound science’: tobacco lawyers, and public relations firms. American Journal of Public Health 91(11), 1749–1757.

Sherrington, Philippa. (2000). Shaping the Policy Agenda: Think Tank Activity in the European Union. Global Society, 14(2), 173 – 189.

Watson, Rory. (1998). Crossing the Business and Political Divide. European Voice (9–15 July 1998).

Weinberg Group. (2009). Science Minds Over Business Matters. http://www.weinberggroup.com/index.shtml (accessed 22 Jun 2009)

Methods

This paper uses tobacco industry documents, released through litigation, other publicly available documents and interviews with EU officials and lobbyists, to explore why large corporations were interested in these reforms, how they attempted to shape the Better Regulation agenda and, in particular, to embed CBA and risk assessment into the EU’s approach to IA (i.e. what the chosen strategies and tactics involved). The tobacco industry documents are available following litigation in the US which required tobacco companies to make many of their internal documents public. There are currently over 80 million documents and they can be searched using optical character recognition via the online Legacy library (http://www.legacy-library.ucsf.edu).

We undertook iterative searches of these documents between mid-April and September 2008. In total, approximately 6,800 documents were reviewed. Of these, 714 were identified as relevant to the story of BR in Europe on the basis that they included references to European regulation processes, BAT’s specific regulatory objectives (e.g. IA, CBA and risk assessment) or key organisations or individuals. The remaining 6,086 documents either appeared to have no relevance to BR, IA, risk assessment or they were duplicates of documents we did include. The 714 relevant documents were imported to an EndNote library, from where they were re-read (in date order), interpreted and thematically coded by an experienced, qualitative researcher. The coding process involved highlighting specific components of BAT’s interest in EU regulatory reform (i.e. what BAT hoped to achieve with regard to IA, CBA, risk assessment, stakeholder consultation, transparency, etc), key individuals and organisations that were involved in the process, mechanisms and strategies employed to shape the agenda and indicators and assessments of progress. Documents were also coded in terms of document type (e.g. whether the document was a letter, an email, an internal report, etc) and authorship (where this was discernable). This article draws on a section of these documents to present the key findings from this research. The interpretation of all documents was checked by at least one other researcher.

Although the tobacco industry documents provide valuable insights into the internal strategies of some of the world’s largest tobacco companies, it is important to recognise that this resource does not represent the entire backlog of internal company documents (MacKenzie and Collin and Lee, 2003). Rather, the documents were released as a result of a process of discovery during litigation. Consequently, these documents are often fragmentary and provide only a partial picture of an organisation’s activities (MacKenzie and Collin and Lee, 2003). In addition, far fewer documents are available from 2000 onwards, which limits the relevance of the documents for understanding more recent developments. For all these reasons, we contextualised our analysis of the internal tobacco company documents using a range of other sources, including interviews with relevant individuals and electronic searches of other databases and online sources (e.g. of the organisations that had been mentioned in the internal tobacco documents and interviews).

In total, we approached 16 individuals for an interview on the basis that they had been involved in policy decisions and debates relating to BR and IA in the EU since 1997 or that they were specifically mentioned within BAT’s documents relating to BR (see Table 2). The exceptions to this were Bruce Ballantine (Table 2), who died before we commenced this research and individuals who still worked for BAT (see below). All but three of the individuals we approached agreed to be interviewed. Of these 13, the following three interviewees agreed to be named: Charles Miller (who led the Fair Regulation Campaign), Stanley Crossick (who co-founded the EPC and worked directly with BAT on the Better Regulation agenda) and David Byrne (Commissioner for Health and Consumer Protection 1999–2004). The other ten interviewees included three members of European Commission staff who were involved in the development and implementation of Better Regulation and/or IA, one member of European Commission staff based in DG SANCO (the Directorate General responsible for health and consumer protection), three heads of voluntary organisations working to promote public health and environmental issues in the EU, one head of an EU based think tank (other than EPC), one senior member of a major Brussels based consultancy firm and one UK civil servant who held responsibility for Better Regulation/IA issues in the UK government. Tables 1 and 2 provide an overview of the key individuals and organisations mentioned in this article.

The interviews were transcribed and analysed alongside the documentary data and although, between them, the interviewees held contrasting views about BR, IA and the tobacco industry, the information interviewees provided was largely consistent with the information garnered through our analysis of the internal tobacco documents, supporting our interpretation. Several of our interviewees were surprised to learn that BAT had been involved in efforts to promote and shape Better Regulation and two (policy-based) interviewees said they believed BAT had not been involved but they provided no evidence to substantiate this belief or to counter the findings presented here. This article draws on a selection of our various data sources to present the key findings; the lead author (KS) led the analysis but the interpretation of all sources employed in this article was checked by at least one other author. Minor revisions to the wording of some sections was made as a result.

Our analysis is undertaken from a public health perspective and it should be acknowledged that, by employing internal tobacco industry documents as one of our main sources, our findings inevitably say more about British American Tobacco’s interests in regulatory reform than they do about the interests of other organisations (e.g. the other companies involved). In addition, while our selection of interviewees was based on a thorough documentary analysis, the sample might have excluded some important informants who were not identified in the documents we identified. Finally, although we interviewed individuals who had undertaken work on behalf of BAT, we chose not to approach current BAT employees for interview because we considered the internal documents likely to provide a more accurate representation of BAT thinking at the time of the reforms and not subject to social desirability or recall bias (as contemporaneous interviews with BAT staff may have been).

Theoretical approach: Employing the ‘Advocacy Coalition Framework’

The case study builds on a wealth of existing research concerning corporate lobbying and policy influence in the EU (e.g. Bouwen, 2002; Coen and Richardson, 2009; Woll, 2007) which charts the ‘growing political sophistication of public and private interests in a complex multi-level venue policy environment’ (Coen, 2007: p333). It provides a basis for assessing the utility of one of the most popular theories of policy change, Sabatier and Jenkins-Smith’s (1999) Advocacy Coalition Framework (ACF). The ACF suggests that diverse groups of actors form relatively stable coalitions around core ideas (relating to values and beliefs about causation) within particular ‘policy sub-systems’. The Framework posits that, once a particular coalition comes to dominate a policy subsystem, policy change is likely to be limited but that significant policy change can occur when a particular coalition’s ideas are perceived to be so successful that some actors switch between competing coalitions, shifting the balance of power in relation to the ‘core ideas’ driving policy.

The policy sub-system with which this paper is concerned is the regulation of business interests in order to protect social (particularly health) or environmental interests, a sub-system in which two distinct coalitions were identifiable in the 1980s and early 1990s (Farquharson, 2003; Smith, 2013a). One consisted of actors concerned with the health and environmental harms caused by some economic activity (largely made up of some civil society and non-governmental organisations, academics, politicians and professional medical groups). To use the terminology of ACF, a policy core belief held by this group was that regulatory intervention provides a crucial means of preventing harms to the environment and public health. The second, competing coalition consisted of actors concerned with the ability of businesses to operate freely and competitively (this group largely consisted of businesses, business organisations and think tanks, as well as some academics and politicians). A policy core belief held by this group was that businesses should be able to operate as freely as possible in the EU (which was conceived of as a largely economic project) and that EU regulations should only be implemented to address market failures (and only where regulations at the Member State level were demonstrably insufficient). It seems likely that policymakers, both at EU and Member State level, were (and remain) split between these two coalitions, with many viewing themselves as arbitrators between the two (this was indeed the way many of our interviewees characterised the situation). Our data indicate that, by the mid-1990s, BAT managers were becoming increasingly concerned that policymakers in the EU were becoming sympathetic to the first group’s views. Regulatory reform appears to have been conceived of by BAT managers as a means of shifting the balance of power back in favour of business and economic priorities. Combined with the wide range of actors involved and the time period of more than a decade, all this suggests that the ACF may offer a valuable hermeneutic device for making sense of recent regulatory change in the EU. However, as the concluding section outlines, our findings also challenge the ACF by drawing attention to the importance of studying the characteristics of the particular ideas that are developed and promoted by coalitions actors, alongside the networks of actors involved.

The particular focus of this paper on the tobacco industry and its involvement in regulatory change is important in light of the fact tobacco remains the leading cause of avoidable premature mortality in Europe (Mackenbach et al, 2013). It is estimated, based on Eurostat data, that in 2009 about 9.9 million years of life were lost due to smoking-attributable premature mortality and that the total cost to the 27 EU member states was about €544 billion (Jarvis, 2012). The tobacco industry has been framed as a ‘vector’ of this epidemic of tobacco-related morbidity and mortality (LeGresley, 1999) and has, largely as a consequence of this, become increasingly excluded from formal health policy discussions (WHO, 2003). Despite this, tobacco-related policy developments in the EU remain highly controversial and deeply politicised, as the recent resignation of EU Health Commissioner, John Dalli, in the context of claims he knew of efforts to bribe a tobacco company, illustrates1 (Watson, 2012). The findings of this paper, which demonstrate the sophisticated and complex nature of tobacco industry efforts to influence policy, are therefore also of interest from a public health perspective.

We note, at the outset, that the tobacco industry documents drawn upon often use the terms ‘IA’ and ‘CBA’ interchangeably, reflecting the fact that the version of IA being promoted by tobacco interests involved an economic framework resembling CBA. For the most part, this paper focuses on IA. However, the term CBA is employed where appropriate when we are quoting directly from tobacco industry documents. By outlining what corporations involved in regulatory reform hoped to achieve, the paper provides an important addition to recent accounts of the European emergence of Better Regulation and IA which focus on the role of the Commission and particular Member States (e.g. Radaelli & Meuwese, 2010; Radaelli, 2007b; Allio, 2007).

British American Tobacco (BAT) and Better Regulation

(i) Contextualising BAT’s interest in Better Regulation and IA

The emergence of neo-liberalism as a governing political philosophy in many EU member states in the 1980s and 1990s (van Apeldoorn, 2003) coincided with a renewed emphasis on deregulation as a means of improving business competitiveness and market efficiency (Department of Trade and Industry, 1985, 1988; Commission of the European Communities, 1993). However, in contrast to other industries, which are typically thought to have enjoyed a renaissance in their policy influence during this period (Farnsworth, 2004; Farnsworth & Holden, 2006), the tobacco industry had begun to experience a significant decline in its credibility and political authority (Sanders, 1997), with many of its traditional techniques of policy influence coming under increasing scrutiny from both public health advocates and public officials (Fooks et al., 2013).

At the same time, the tobacco industry was becoming increasingly concerned about the extent of tobacco control legislation emanating from the EU (Gilmore and McKee, 2004) and broader corporate concern was growing around the use (and potential use) of the ‘Precautionary Principle’ in the EU (BAT, 2000a; EPC, 1998). This principle applies to circumstances in which there are reasonable grounds to believe that a given hazard would, if it occurred, result in severe or irreversible damage to public health or the environment, and it calls on policymakers to intervene to prevent such hazards, even when there is no clear scientific consensus about the likelihood of the hazard occurring (Commission of the European Communities, 2000). Some commentators argue that the Precautionary Principle is inconsistent with scientific approaches to policymaking and does not sufficiently take account of economic efficiency (Allio et al., 2005; EPC Risk Forum; 2005). Indeed, as Löfstedt (2002) notes, many business interests came to perceive the Precautionary Principle ‘as a tool for the more radical environment and health advocates’.

It is in this context that BAT began to consider ways of increasing its influence over EU policy by promoting the need for a form of structured risk assessment to be embedded within the European legislative process (BAT, 1995; Chalfen, 1996a, 1996b, 1996c). It might appear paradoxical that risk assessment could be promoted by a company whose products were well known to pose serious risks to human health (Royal College of Physicians, 1962; National Cancer Institute, 1993). Indeed, BAT was warned by one of its political consultants, Charles Barker (see Table 1), that such an approach might work against the company’s interests (MacKenzie-Reid, 1995). However, having closely monitored Philip Morris’s use of risk assessment to undermine proposed restrictions on environmental tobacco smoke in the US (Hirschhorn & Bialous, 2001; Ong & Glantz, 2001; Muggli et al., 2004), senior BAT managers took the view that a policy requirement for a particular form of risk assessment could help the company defeat efforts to introduce policies restricting smoking (BAT, 1995, undated-a). This would be achieved through promoting a set of rules for assessing epidemiological data, within risk assessment, that would place the bar for what constitutes ‘unacceptable risk’ above that posed by environmental tobacco smoke (see Bero, 2012).

(ii) Building a coalition of support around a malleable concept

BAT was aware that a proposal for risk assessment guidelines promoted solely by a large tobacco company was unlikely to be received favourably (Mackenzie-Reid, 1995). Consequently, the strategies BAT employed to promote this issue were collaborative and indirect, obscuring specific, tobacco-related objectives. Hence, BAT was advised by the consultancy company, Charles Barker to construct a supportive coalition of interests, initially focusing on recruiting other businesses with potentially overlapping interests in risk assessment:

‘As a first step, BATCo should seek to identify industries that would benefit from risk assessment guidelines […]. The pharmaceutical industry would be a clear contender since research on the veracity of drugs prior to medicinal approval may well be linked to assessments which overstate the degree of danger. Similar considerations apply to the oil and chemical industries, especially in relation to the assessment of environmental dangers. All industry would however benefit from clearer assessment guidelines if that resulted in a reduction in compliance costs associated with health & safety legislation. There would be clear benefits in persuading the CBI [Confederation of British Industry] to launch an initiative on risk assessment, especially since they have two appointees on the Health & Safety Commission.’ (MacKenzie-Reid, 1995)

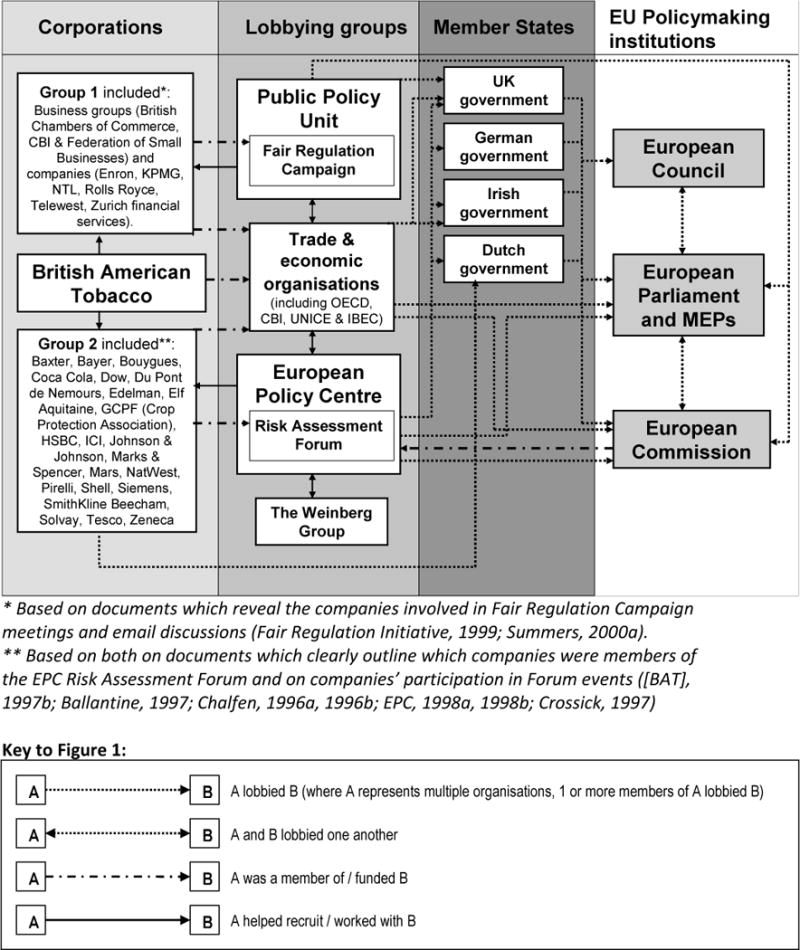

Reflecting this advice, BAT solicitor, Stuart Chalfen, subsequently wrote to other companies involved in manufacturing and marketing regulated products (Chalfen, 1996b, 1996d, 1996c, 1997) although not (as far as it is possible to tell) to other tobacco companies. A meeting involving BAT staff and representatives from some of the companies Chalfen approached (including Elf Aquitaine, Imperial Chemical Industries (ICI) and Zeneca) was subsequently held in Brussels in January 1997. The minutes of this meeting note that a key part of the proposed strategy for achieving regulatory reform would involve generating ‘a large reservoir of informed and favourable opinion towards the project across the EU which [could] be activated at short notice at the appropriate time’ (Anonymous, 1997a). In other words, the aim was to create the sense amongst policymakers that there was a widely-held consensus in support of these regulatory reforms within the business community. As we describe later on, the business interests involved were subsequently expanded, including via a separate, UK-based group known as the Fair Regulation Campaign (see Figure 1; Table 1 and p 19, below).

Figure 1. The multifaceted approach lobbying effort to shape and promote Better Regulation.

References for Figure 1:

Ballantine, Bruce. 1997. Conference: Evaluating Risk - A Balancing Act. (Bates number(s): 321573176-321573178). Source: BAT. URL: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/cfg63a99.

[BAT]. 1997. Cost Benefit Analysis and Risk Assessment Working Group - Note of Meeting Oct 1997. (Bates number(s): 321573259-321573260). Source: BAT. URL: http://bat.library.ucsf.edu//tid/cgg63a99 (accessed 03 Jun 2008).

Chalfen, Stuart. 1996a. Note from regarding meeting at Brussels offices. (Bates number(s): 800102517-800102522). Source: BAT. URL:http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/hhf14a99 (accessed 01 Aug 2008).

Chalfen, Stuart. 1996b. Note from Stuart P Chalfen to Philippe Bocken regarding risk assessment and cost benefit analysis. (Bates number(s): 700513775-700513779). Source: BAT. URL: http://bat.library.ucsf.edu//tid/vgj23a99 (accessed 02 Jun 2008).

Crossick, Stanley. 1997. Risk Assessment. (Bates number(s): 321573196). Source: BAT. URL: http://bat.library.ucsf.edu//tid/igf61a99 (accessed 04 Jun 2008).

EPC. 1998a. Approval of Mission Statement and Prospectus. (Bates number(s): 321574237-321574238). Source: BAT. URL: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/ujg63a99.

EPC. 1998. Forum on Risk: Brussels 12 March 1998. (Bates number(s): 321574226-321574232). Source: BAT. URL: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/qhf61a99 (accessed 02 Aug 2008).

Fair Regulation Initiative. 1999. Campaign Group Presentation: 27 January 1999. (Bates number(s): 321332622-321332638). Source: British American Tobacco. URL: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/zuy23a99 (accessed 29 Jul 2008).

Summers, Martin. 2000. Fair Regulation Campaign - Useful for EU Regulation and Regulatory Best Practice Discussions (Bates number(s): 322239554-322239555). Source: BAT. URL: http://bat.library.ucsf.edu//tid/ari23a99 (accessed 09 Jul 2008).

The consultancy firm Charles Barker also advised BAT to use a ‘front group’ to expedite the campaign to promote regulatory reform (MacKenzie-Reid, 1995), noting that public knowledge of tobacco industry involvement could seriously undermine the campaign’s credibility (Honour, 1996). After briefly considering the idea of conscripting a centre left institute or think tank to ‘confound the critics’, (Fitzsimons, 1995), BAT managers turned to the EPC, a leading Brussels-based think tank (Sherrington, 2000; Table 1) with ‘a broad political profile across a number of issue domains’ (Coen, 1998, p.78). The EPC received funding from the European Commission (EPC, 2009), which bestowed it with something of an ‘insider’ status (Broscheid & Coen, 2003). These features made the EPC an excellent platform from which to present the regulatory reforms as credible and non-partisan to policymakers and journalists.

BAT was initially advised by both UK-based consultancy firm the Public Policy Unit (Table 1) and Brussels-based lobbyist Stanley Crossick (Table 2) that the European Commission was not interested in developing risk assessment in the way BAT envisioned2 (Gretton, 1996b; Crossick, 1996b). In February 1996, the legal firm Covington & Burling (see Table 1) suggested that an alternative way forward might be to situate any discussion of risk assessment within the context of the European Commission’s existing commitment to undertaking Business IAs (Covington & Burling, 1996). Known as fiches d’impact, these basic Business IAs had been mandated in the EU since 1986 (Commission of the European Communities, 1986a) and focused on assessing the potential impacts of EU legislative proposals on small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) (Commission of the European Communities, 1986b). In practice, their use was erratic and, when conducted, seemed to involve only limited information (Froud et al. 1998). However, Covington & Burling advised BAT that the Commission’s priorities for 1996 included the implementation of revised guidelines for fiches d’impact and suggested that an opportunity therefore existed to press for: ‘More detailed guidance on the preparation of business impact assessments, perhaps including elements of structured risk assessment’ (Covington & Burling, 1996). Covington & Burling identified the UK government (which had already gone some way to incorporating risk assessment and Business IA into public policymaking) and the German government (which was perceived to be committed to reducing business-related regulations) as obvious policy allies in such a campaign. They also suggested that Nordic member states and ‘some non-business interest groups’ might be persuaded to support the proposals if they believed that they would help achieve more transparent policymaking, whilst Commission support could be optimised by linking the measure to the growth of SMEs (Covington & Burling, 1996).

The documents suggest BAT managers were persuaded by the idea of using IA as a means of promoting risk assessment (e.g. Anonymous, 1997a; Gretton, 1998), a decision which appears to have marked the start of a broader strategy to deliberately construct a vaguely defined idea that could be strategically adapted to appeal to diverse constituencies. Yet, rather than trying to embed risk assessment within fiches d’impact, as Covington & Burling had suggested, BAT committed itself to the more ambitious aim of using the Commission’s interest in revising its fiches d’impact guidelines as a foothold for a campaign which was intended to achieve nothing less than a paradigm shift in the way European regulation functioned (Chalfen, 1996d). BAT’s strategy hinged on replacing fiches d’impact with a far more thorough and economically orientated form of Business IA, based on cost-benefit analysis (CBA), whilst working to promote the notion that risk assessment was a necessary part of this approach (e.g. Anonymous, 1997a; Chalfen, 1996d). This was in no way an obvious strategy; not only were fiches d’impact silent on the issues of assessing risk and risk management (Commission of the European Communities, 1986b) but the process itself was relatively marginal to European policymaking (Froud et al., 1998).

Focusing on IA offered a number of benefits to the company. By making economic assessments central to risk/benefit calculations (Bero, 2012), it was hoped that it might counter what BAT and its allies perceived to be an increasing use of the Precautionary Principle in EU policymaking (BAT, 2000a; EPC, 1998; see above). By enabling public officials to regulate in the absence of a clear scientific consensus over the risks of economic activity to public health and the environment (Martuzzi & Bertollini, 2005; Commission of the European Communities, 2000), the Precautionary Principle was widely regarded by EU businesses as subordinating economic growth and competitiveness to harm prevention (BAT, 2000a; EPC, 1998; Löfstedt, 2002). BAT managers conceived that incorporating risk assessment into CBA would provide a means of achieving precisely the opposite (Bero, 2012). As one BAT document explains, the strategy aimed to ensure: ‘that new measures are not adopted unless they will achieve significant risk reductions at a reasonable cost, and to require that new regulations and legislation are based on quantitative risk assessment’ (BAT, 1996a). The immediate commercial aim of the approach was to prevent the introduction of tobacco control measures, such as restrictions on tobacco advertising and legislation designed to limit second-hand smoke exposure, by creating minimum requirements for risks to health linked to the economic impact of proposed regulation (BAT, Undated-b). In addition, the accountancy firm Ernst and Young advised BAT that the requirement for quantitative data in CBA might conceivably help establish a more resource-dependent relationship between BAT and EU officials:

‘The lack of official statistics will mean that greater attention and credibility will be [given] to the industry developed statistical series. This can be used to advantage in discussions and negotiations with government agencies as it means that the industry has access to information (potentially including economic assessment studies) that are unavailable to government officials. Officials will often be more willing to talk to industry in these circumstances.’ (Ernst & Young, 1997)

This is likely to have been particularly attractive to BAT in the context of the declining political authority and public credibility of tobacco industry interests (Fooks et al, 2013) as it seemed to allow the company to re-establish itself as a legitimate stakeholder in policy debates. Similarly, the calls for greater ‘transparency’ and ‘consultation’ within policymaking, associated with Better Regulation, were likely to have been helpful to BAT in securing their inclusion in policymaking discussions ([BAT], 1997a; Anonymous, 1997a; Gretton, 1996b). Hence, an emphasis on consultation and transparency served the dual purpose of attracting policy actors committed to transparency, such as the Nordic Member States (see above), and providing a rationale for challenging tobacco industry exclusion from EU policymaking discussions.

Although these various ideas (risk assessment, a form of IA modelled on CBA, and commitments to transparency and consultation) were not immediately labelled ‘Better Regulation’ by BAT or the EPC, the documents indicate that, from the start, they were considered part of the same project, and were presented as mutually reinforcing ([BAT], 1997a; Ballantine & Crossick, 1996; Gretton, 1996b). Promotional material therefore focused on collectively promoting risk assessment and CBA (as a form of Business IA), transparency and stakeholder consultation (Ballantine & Crossick, 1996). The ‘chameleonic’ qualities (Smith, 2013b) of the overall concept, originally mooted as ‘better legislation’3, allowed the reforms to be packaged differently according to the audience being targeted.

First, concepts such as risk assessment and Business IA were simultaneously marketed as advantageous to the narrow interests of regulated industries and as a valuable component of socially efficient policymaking. Thus, in letters to large corporations in other regulated sectors, Stuart Chalfen (a solicitor at BAT - see Table 2) described the campaign as ‘a unique opportunity’ to ‘protect in a fundamental manner the interests of European industry vis-à-vis the European regulators’ (Chalfen, 1996b). Chalfen’s letter concluded that the proposed reforms represented ‘a remarkable step forward’ for regulated companies in the EU (Chalfen, 1996b). In contrast, an EPC occasional paper making the case for regulatory reform to a broader policy audience, produced following a suggestion that such a paper could usefully serve as a campaign ‘hook/crib sheet’ (Anonymous, 1996e), focused explicitly on CBA and only briefly mentioned risk. The key point here is that, in marked contrast to Chalfen’s promise to other large corporations of fundamental regulatory reform, the EPC occasional paper simply presented CBA as a technical ‘management tool’ that could be used to improve transparency, accountability and ‘the quality of legislative and regulatory decision-making’ (Ballantine & Crossick, 1996). The suggestion here was that such a tool would merely help policymakers to better understand ‘the full costs and benefits of government actions’ (Ballantine & Crossick, 1996), rather than significantly change the relationship between industry and regulators or shape officials’ approach to assessing and managing risk. In other words, the way in which the regulatory reforms were pitched to policy audiences was markedly different from the manner in which Chalfen framed the reforms in correspondence with other regulated industries.

Second, in-line with Covington & Burling’s advice, the reforms were initially pitched by the EPC as primarily benefiting SMEs, which fitted with the Commission’s aim of enhancing the competitiveness of smaller enterprises in the EU (EPC, 2001, 2004). This was despite the fact that the campaign was primarily orchestrated by, and designed to promote the interests of, large corporations in regulated sectors (see above and Figure 1), such as BAT4. At a later stage, Charles Miller (of the Fair Regulation Campaign) then emphasised the need for the officials implementing Better Regulation reforms to focus on the needs of big business (Miller quoted in Gribben, 2000)5.

Third, the reforms were presented in subtly different ways to appeal to different political audiences. In 1996, for example, faxed documents from Covington & Burling suggest that, in the run up to the UK’s 1997 General Election, the coalition adapted the way in which the concepts were described to appeal to the perceived preferences of the two main, opposing parties, Labour and the Conservatives ([Covington & Burling], 1996a, 1996b).

Finally, the chameleonic quality of the reforms enabled the campaign to respond to changing political circumstances. In 1999, the European Commission was rocked by a scandal concerning nepotism and cronyism and 20 Commissioners were forced to resign (CNN, 1999). The EPC subsequently focused on emphasising the aspects of the proposed reforms relating to ‘transparency’ and ‘accountability’, presenting Regulatory IA (a form of Business IA) as a means of addressing the perceived ‘democratic deficit’ in Europe (EPC, 2001).

In focusing on the promotion of such a multifaceted and malleable concept (which became known as Better Regulation), as opposed to the very narrow, specific form of risk assessment that BAT managers eventually hoped to achieve, it was possible for the campaign to be adapted to appeal to different audiences. The strategies of developing a malleable concept and building a large coalition of support were therefore closely intertwined, with the chameleon-like qualities of Better Regulation helping to attract the diverse constituencies required for success, and the divergent support further contributing to the concept’s varying interpretations. The EPC helped both to establish the broad-based corporate constituency in favour of the regulatory reforms and, over time, to attract policy officials and politicians to the coalition, facilitating the political traction of the coalition’s proposals.

The major disadvantage of ‘chameleonic ideas’ is that their flexibility raises the risk that key sponsors may lose control of the agenda. Reflecting this, BAT had, from the start, been warned that risk assessment guidelines ‘might be hijacked by other lobbies’, such as ‘the environmental lobby [which] might insist that sustainable development issues comprise one of the criteria in the assessment guidelines’ (MacKenzie-Reid, 1995). This concern was not unwarranted. In 1997, for example, Crossick reported that the EU Directorate General responsible for health policy was establishing a separate risk assessment unit, reporting directly to the Director-General, which had plans to develop approaches to risk assessment that Crossick considered ‘political’ and ‘dangerous’ (Crossick, 1997).

With a view to maintaining control over the campaign, BAT and EPC worked to construct a closed group within the EPC, helping ensure that expansion of the coalition did not necessarily dilute their ability to manage the direction of the campaign. In 1996, the EPC created the Risk Forum (EPC Risk Forum, 2006), the membership of which was dominated by BAT and the other large companies that had agreed to support the campaign. Significantly, according to our interview data, even though a number of non-governmental and civil society organisations were members of the EPC at this time, they were specifically excluded from the Risk Forum throughout its existence within the EPC (indeed, two interviewees involved in the campaign reported that it was as a result of pressure to allow other members of the EPC to join the Risk Forum that the Forum left the EPC in 2007 and established itself as the independent European Risk Forum – see Table 1). This suggests that a ‘closed’ (invitation only) inner group was established within the broader coalition and that this approach was deemed crucial, probably because it allowed BAT and other major corporations to maintain some control over the direction of the campaign, even as support for ‘Better Regulation’ was evolving into a more institutionalised ‘advocacy coalition’, involving politicians and officials at EU and member state level. The potential for the campaign’s ideas to be interpreted in multiple ways also explains why BAT took a closely managed approach to mobilising a coalition for regulatory reform, as outlined below.

(iii) Working to achieve policy change

The process of embedding the Forum’s broad interests into European policymaking was undertaken in stages and initially focused on inserting a Protocol into the Treaty of Amsterdam (a revision to the Treaty on European Union) which would make CBA a mandatory component of EU policymaking (BAT, Undated-a; Crossick, 1996b; interview with Crossick, 18th September 2008). To achieve this, the Forum’s members were encouraged to focus on mobilising support from public and elected officials in strategically important member states in advance of the inter-governmental conference that culminated in the Treaty of Amsterdam ([BAT], Undated; [Risk Forum], Undated; Anonymous, 1997b; Chalfen, 1996d; Veljanovski, 1996; interview with Crossick, 18th September 2008). In practice, the strategy relied heavily on the EPC and supportive business organisations, notably UNICE (the Union of Industrial and Employers’ Confederations of Europe, subsequently renamed BusinessEurope – see Table 1), the CBI (Chalfen, 1998a, 1998b, 2000; Etherington, 1994), the Bundesverband der Deutschen Industrie (the German employers’ federation), and the Irish Business and Employers Confederation (Agar, 1997; Crossick, 1996c, 1996b, 1996a; Geoghegan, 1997; Kretschmer, 1996; UNICE, 1996b; Woods, 1995).

Lobbying efforts focused particularly on Member States where the ruling political parties were already predisposed to Business IA or CBA, such as the UK and Germany, although some other Member States were also targeted, notably the Irish and Dutch Governments which consecutively held the EU Presidency during the Inter-Governmental Conference (Anonymous, 1997a, 1997b; BAT, Undated-a, Undated-b; Covington & Burling, 1996; Gretton, 1997). In Ireland, the UK and Germany, supportive trade associations appealed directly to government ministers (Geoghegan, 1997; Crossick, 1998b; Turner, 1998, Chalfen, 1996a; Kretschmer, 1996; Marcq, 1996; UNICE, 1996a). In Germany and the Netherlands, lobbying was directed via key industrialists with close personal links to senior policymakers (Anonymous, 1997a; Chalfen, 1997; Curtis, 1997; Hudig, 1997). Both the EPC (EPC Risk Forum, 2006) and UNICE (UNICE, 1996b) made direct submissions to the Inter-Governmental Conference, calling for CBA to be made legally binding.

Persuading the UK Government to act as an advocate on behalf of the Forum was considered particularly important. BAT managers and the EPC considered the UK to be further along than other Member States in embedding Business IA into policymaking (Covington & Burling, 1996; BAT, 1995). Documentary evidence (Gretton, 1996b, 1996a; Binning, 1996a, 1996b, 1996c) and existing literature (Farnsworth, 2004; Farnsworth & Holden, 2006) suggest that this is likely to have been partly due to the influence that businesses, like BAT, had already exercised over regulatory policy in the UK. The focus on the UK and other Member States deemed likely to be supportive allowed the campaign to make use of the EU’s decentralised policy system, with its multiple points of influence (Coen, 2007). This included enabling the coalition to target the Council of Ministers and thus representatives of EU Member States (see Figure 1).

This first stage of the strategy, securing a change in the wording of the official Treaty on European Union was successful (BAT, Undated-b; EPC, 1997). The documents do not make clear the extent to which BAT/EPC was formally involved in drafting the Protocol (which was tabled by the UK delegation) but BAT have several versions of the Protocol on their files (Anonymous, 1996a, 1996b, 1996c, 1996d, Undated). The eventual wording of the sections of Treaty that BAT managers focused on was as follows:

‘Without prejudice to its right of initiative, the Commission should:

- -

Except in cases of particular urgency or confidentiality, consult widely before proposing legislation and wherever appropriate, publish consultation documents:

- -

justify the relevance of its proposals with regard to the principle of subsidiarity; whenever necessary, the explanatory memorandum accompanying a proposal will give details in this respect. The financing of Community action in the whole or in part from the Community budget shall require an explanation;

- -

take duly into account the need for any burden, whether financial or administrative, falling upon the Community, national governments, local authorities, economic operators and citizens, to be minimised and proportionate to the objective to be achieved.’ (BAT, Undated-b)

Although it did not refer specifically to a requirement for CBA or IA, this section of text was interpreted by BAT to mean ‘the Commission must now take into account the financial and administrative burden (cost), which has to be minimised and proportionate to the objective (benefit)’ (BAT, Undated-b). It is impossible to know whether the UK government already intended to include wording to the above effect in its submission; when interviewed, Crossick said that the EPC had suggested the inclusion of a requirement for CBA to various Member State representatives and that this suggestion was generally welcomed. Whatever their level of involvement in the specific Treaty change, BAT managers considered it to be a major coup (BAT, Undated-b). However, the chameleonic nature of the ideas used in the campaign, and the relatively imprecise wording of the protocol, inevitably widened the range of ways in which regulatory reform might subsequently evolve. This necessitated sustained political activity aimed at narrowing the received meaning and legal interpretation of the Treaty change ([BAT], 1997b; [EPC], 1998; EPC, 1997; interview with Crossick, 18th September 2008).

The next stage of the campaign had at least three overlapping strands. The UK’s leadership of the six-monthly rotating EU Presidency was seen as an important ‘window of opportunity’ (BAT, Undated-a). Hence, at EPC’s suggestion, one strand involved UNICE and the CBI directly lobbying the UK Prime Minister, Tony Blair, over the implementation of the Protocol ([EPC], 1998; Crossick, 1997, 1998b, 1998c) and according to a note from Crossick (1998b), these efforts were received favourably. The second strand centred on the organisation of a conference to promote the Forum’s favoured interpretation of the Protocol, which was that CBA was now a legal requirement in the EU and that ‘CBA must include risk assessment’ (Gretton, 1998). The EPC and the Weinberg Group (an international consultancy firm which had been involved in a tobacco industry campaign to reform risk assessment in the USA – Ong & Glantz, 2001) approached David Clark MP (see Table 2) with a proposal for the UK to sponsor a conference on risk whilst it held the EU Presidency ([BAT], 1997a, 1997b; Huggard, 1997). Clark, who was the Minister responsible for regulatory reform in the UK at that time, and who had previously served as a political advisor to BAT (BAT, 1992), agreed to support the initiative6. The conference, entitled ‘Managing Risk: A Balancing Act’, went ahead and was paid for by BAT, which also played a key role in selecting speakers and delegates and organising the associated promotional material ([BAT], 1997b; Curtis, 1998a, 1998b, 1998c; Crossick, 1998a). Yet it was officially sanctioned by the UK Presidency of the EU and formal materials made little, if any, mention of BAT (Anonymous, 1998a; [BAT], 1997b, 1997a). A third strand involved the CBI and BAT working with a number of other business interests to establish a second corporate group in January 1999, called the Fair Regulation Campaign (see Table 1). This campaign specifically aimed to influence UK and European officials’ interpretations of the new Treaty Protocol (Miller, 1999; Anonymous, 1999). Coordinated by Charles Miller of the Public Policy Unit (Tables 1 and 2), the Fair Regulation Campaign quickly won the support of a number of European Commissioners, including Erkki Liikanen, then Commissioner for Enterprise and Information (Summers, 2000a, 2000b; Fair Regulation Campaign, 2000; Business Europe, 2000; interview with Charles Miller on 27th August 2008).

With the increasing support and involvement of officials and politicians, BAT’s original group of corporations steadily broadened into a rather more classic advocacy coalition, involving key politicians and policymakers as well as the large businesses, think tank and consultancy organisations initially involved. This allowed the coalition to exert influence across the EU Commission, Parliament and Council (see Figure 1). Although the range of actors involved reflected the considerable breadth of support for regulatory reform, support for the core ideas of Better Regulation was more sectoral than it might have appeared. In other words, the diversity of entities now working to move the issue forward is likely to have created a misleading impression amongst EU officials and other Member States concerning the depth of consensus in favour of the Better Regulation agenda (an interpretation supported by our interview data). Obscuring the specific interests of the companies involved is likely to have helped attract policymakers and others (such as SMEs and civil society organisations), ensuring they were unaware of the extent to which a small group of large corporations were aiming to shape Better Regulation’s core concepts in their favour. This is not to say, however, that those who supported the campaign did not agree with the need for regulatory reform or the potential benefits of IA, including that it might delay and prevent some EU legislation (see Radaelli and Meuwese, 2010).

Commissioner Liikanen’s support proved crucial to formalising the EPC Risk Forum’s preferred interpretation of the Protocol into EU decision-making as Liikanen oversaw a pilot study of Business IA in the Commission (Enterprise Directorate-General, 2002), which reportedly involved the provision of a Fair Regulation Campaign check-list to all Directorate-Generals (Corporate Europe Observatory, 2001). Additionally, the EPC Risk Forum (which was at that time chaired by BAT scientist, Christopher Proctor) was commissioned to produce an occasional paper entitled Regulatory Impact Analysis: Improving the quality of EU regulatory activity (EPC, 2001), which also contributed to the official pilot study.

Tracking how the campaign progressed from 2001 onwards is complicated by the availability of substantially fewer internal tobacco company documents. Alternative sources of data, including interviews with EU policymakers and lobbyistsv, suggest that many of the key elements of the campaign continued7, although in line with BAT’s original ambitions, there appears to have been more of a shift in emphasis towards trying to shape policy assessments of, and responses to, risks8. Also, as described above, the Risk Forum now exists as an independent think tank (EPC, 2006; European Risk Forum, 2009) which is made up almost solely of tobacco and chemical industry interests9.

An assessment of the current situation suggests that the Better Regulation agenda has been successfully adopted at EU level. For example, units and Directorates of the Commission have been renamed to include Better Regulation (see Radaelli and Meuwese, 2010), the European Commission created an official website dedicated to Better Regulation (recently renamed Smart Regulation - http://ec.europa.eu/smart-regulation/index_en.htm) and, as Radaelli and Meuwese (2010) note, Better Regulation became a priority for the Lisbon agenda. IA has been formally adopted (albeit it on a ‘soft law’ basis – see Alemanno, 2009), with Commission guidelines now requiring integrated IAs, which incorporate assessments (preferably quantitative) of key business, environmental and social impacts, to be produced for virtually all proposals (European Commission, 2002, 2005, 2009)10. There is also a consensus that Better Regulation in the EU represents a qualitatively different approach to governance and that IAs are taken seriously, often more seriously than is the case in Member States (again, see Radaelli and Meuwese, 2010). However, it is too early to assess whether the large, European-based corporations involved in the coalition described in this paper have been able to benefit from the regulatory reforms as they hoped.

Concluding discussion

This paper addresses an important gap in the current academic literature concerning the origins and evolution of Better Regulation in the EU by providing an account of large business efforts to shape and promote these regulatory reforms. Although the paper focuses on tobacco interests in particular, the similarities between the tobacco industry and other regulated sectors (Freudenberg. & Galea, 2008; and Brownell & Warner, 2009), including those industries working to limit regulation relating to climate change (see Oreskes and Conway, 2012), mean many of the paper’s policy implications stretch well beyond tobacco.

From a policy perspective, our findings point to the way in which policy entrepreneurs can amplify their influence over regulatory policy by skilfully exploiting multiple access points at a distance, obscuring the interests involved in promoting particular policy ideas. The ease with which the EPC Forum and the Fair Regulation Campaign both appear to have been able to involve political élites in corporate-led campaigns is consistent with the argument, made elsewhere, that commercial consultancy organisations have become increasingly institutionalised within the EU policymaking system (Lahusen, 2002). Our findings therefore reinforce calls for the Commission to maintain a mandatory register of interests (ALTER-EU, 2006), and confirm the importance of ensuring that mechanisms aimed at making EU lobbying more transparent are co-ordinated across its institutions (Coen, 2007) and extended to think tanks.

Of course, the promotion of an idea by a particular company/industry does not make it a ‘bad idea’ per se. Nor is it necessarily the case that the apparent success of BAT’s campaign ‘is an indication of ‘power’, in the sense of victory in a business-government conflict’ (Woll, 2007; p58): it may simply represent the ‘convergence of business and government objectives’ that Woll (2007: p59) identifies as common to many European policy debates. Indeed, the economic orientation of the EU’s Lisbon agenda may eventually have led to an economically dominated form of IA being developed and incorporated into the EU policymaking process, even without the involvement of BAT and its allies. Despite this, two interviewees who worked at the Commission (interviewed in 2008) attributed the origins of the ‘Better Regulation’, and the Commission’s policy interest in IA, directly to the EPC; whilst Stanley Crossick (Table 2) stated that the EPC’s interest in ‘Better Regulation’ and IA had, in turn, originated from Stuart Chalfen of BAT (interview with Stanley Crossick on 18th September 2008). Whilst policy decisions rarely originate from one clear source, these interviews support our broader data in suggesting that BAT was highly influential in promoting this agenda in the EU. This does not lead us to conclude that Better Regulation is necessarily a negative development from a public health perspective, but rather that policymakers and those interested in promoting and protecting public health (which the EU has a legal requirement to do – see Hervey et al, 2010) should at least be aware of why BAT has been working to influence Better Regulation and what its managers hoped to achieve. When considering the policy interests and ambitions of a major tobacco corporation, it is important to stress (as outlined earlier) the considerable extent to which premature morbidity and mortality are caused by tobacco products in Europe (WHO Europe, 2007). This means that efforts by a tobacco company to avoid legislation likely to reduce tobacco consumption must necessarily be understood as efforts which, if successful, are likely to result in higher than necessary levels of morbidity and mortality (Mackenbach et al, 2013).

Indeed, four aspects of the way IA has been implemented in the EU suggest it may be offering at least some of the benefits to large companies that BAT hoped. First, Löfstedt (2004) claims that the ‘regulatory pendulum’ swung away from the Precautionary Principle when integrated IA guidelines were officially introduced in the EU, shifting the burden of proof onto policymakers (i.e. policymakers were required to use IA to demonstrate that a regulated product causes enough harm to warrant intervention, as opposed to the onus being on business interests to prove their safety). Second, the way in which IA is functioning in the EU is inevitably shaped by the context in which it is being implemented and, currently, that context is the Lisbon Agenda, which is clearly economic in orientation with a particular focus on business competitiveness (see Radaelli and Meuwese, 2010). Third, the Commission’s internal control body for IAs, the Impact Assessment Board, does not include any representative from the DG responsible for health. This is notable, given that Radaelli and Meuwese (2010) claim the Board was chosen to reflect the main categories of impacts perceived to be important by the Commission. Finally, independent reviews of IAs produced by the Commission have consistently found that economic impacts have received the most attention (Franz & Kirkpatrick, 2007; Wilkinson et al, 2004), with environmental and social (particularly health) impacts receiving far less consideration (Franz & Kirkpatrick, 2007; Salay & Lincoln, 2008; Ståhl, 2010). Elsewhere, we explain how tobacco and chemical companies have tried to use IA specifically, and Better Regulation generally, to prevent and/or weaken policy proposals impacting on their respective interests (Smith et al, 2010).

From a theoretical perspective, the story presented in this paper can be understood in terms of a struggle between competing civil society and corporate led coalitions. The former believed in the need for greater EU regulations to guard against social and environmental harms (including to health), whilst the latter believed that regulation of economic operators at EU level should be as limited as possible in order to promote competitiveness and free market ideals. BAT’s concern with a perceived increase in EU regulatory activity, linked to the Precautionary Principle, seems to have been interpreted as an indication that the competing coalition was becoming powerful enough to threaten the commercial interests of regulated industries operating in the EU. This is not to say that the health-environmental coalition was necessarily achieving a level of policy influence significant enough to threaten the business-orientated coalition’s interests for, as Sabatier and Jenkins-Smith (1999) point out, coalition actors tend to view their opponents as more threatening and powerful than they often are. Whatever the reality, BAT managers worked to build a political constituency around regulatory reform that they hoped would shift the balance of power back towards business and economic interests. These regulatory reforms included mandatory requirements for EU policymakers to undertake ex-ante IA and risk assessment and to consult with stakeholders at an early stage, all of which appear to have been perceived as ways of ensuring that the production of EU regulation would be slowed and that the business-orientated coalition would have greater opportunities to influence policy proposals likely to affect their interests. The requirement to ‘consult widely’ also appears to have been a means of enhancing the ‘significant resource dependency’ between officials and commercial interests that Coen (2007: p334) has identified as common within EU lobbying but which has been increasingly limited in tobacco-related contexts (WHO, 2003).