Abstract

Question

Can ethnic differences in spirometry be attributed to differences in physique and socio-economic factors?

Methods

Assessments were undertaken in 2171 London primary school-children on two occasions a year apart whenever possible, as part of the Size and Lung function In Children study.

Measurements

included spirometry, detailed anthropometry, 3-D photonic scanning for regional body shape, body composition, information on ethnic ancestry, birth and respiratory history, socio-economic circumstances and tobacco smoke exposure.

Results

Technically acceptable spirometry was obtained from 1901 children (mean age: 8.3yrs (range: 5.2-11.8yrs), 46% boys, 35% White; 29% Black-African origin; 24% South-Asian; 12% Other/mixed) on 2767 test occasions. After adjusting for sex, age and height, FEV1 was 1.32, 0.89 and 0.51 z-score units lower in Black, South-Asian and Other ethnicity children respectively, when compared with White children, with similar decrements for FVC (p<0.001 for all). Although further adjustment for sitting height and chest width reduced differences attributable to ethnicity by up to 16%, significant differences persisted after adjusting for all potential determinants including socio-economic circumstances.

Answer

Ethnic differences in spirometric lung function persist despite adjusting for a wide range of potential determinants, including body physique and socio-economic circumstances, emphasising the need to use ethnic-specific equations when interpreting results.

Keywords: Ethnicity, Spirometry, children, anthropometry, reference equations

Introduction

Ethnic differences in lung function (LF) are well documented and the importance of adjusting for ethnicity has been emphasised[1-6]. However, the paucity of spirometry references taking ethnicity into account, especially in children, impedes diagnosis and clinical management of lung disease, and complicates interpretation of clinical trials where LF is a primary outcome[6]. The recently published GLI-2012 multi-ethnic spirometry equations[7] provide a good fit for contemporary Black-African origin and White London primary school-children[8], and although the published equations did not cover all ethnic groups, a preliminary coefficient for South-Asian children based on GLI-2012 has been developed[9,10]. Nevertheless, ascribing ethnicity is complicated in an increasingly multi-ethnic society.

Standing height is a major determinant of LF, but differences in body proportions and composition may explain much of the remaining ethnic variation. Despite long-standing attempts to identify factors underlying ethnic differences in LF[1,3,4] the contribution of body physique is poorly understood. Identification of the best linear measurements to explain variability in LF is complicated by the large number of such measurements and the impracticality of obtaining them, especially in children. Whole body 3-D photonic scanning, a new technology that provides rapid, detailed data on regional body shape from digital anthropometry, could address such issues[11].

The extent to which ethnic differences in LF are associated with genetic ancestry as opposed to environmental exposures, nutritional or socio-economic circumstances also remains controversial[1,3,12,13], with interpretation compromised by the paucity of appropriate high quality data. While some groups have suggested that the same ventilatory function predicts the same level of mortality in different ethnic groups, thus discouraging the use of ethnic-specific equations[14], others have reported that African genes are associated with lower LF[5], and that differences in socioeconomic circumstances (SEC) explain only a small proportion of ethnic differences[3,15-17].

The primary aim of this study was to ascertain the extent to which ethnic differences in LF can be attributed to differences in physique and socio-economic factors. Secondary aims were to identify simple measures of physique (in addition to standing height) that could be used in a clinical setting to improve prediction of LF and to confirm that the GLI-2012 equations are appropriate for a multi-ethnic population of London school-children.

We hypothesised that after adjusting for sex, age and standing height, inclusion of additional measures of body physique and socio-economic factors would significantly reduce ethnic differences in LF by at least 50%. Prior to undertaking analyses for this study, methodology relating to selection of the reference population[18], categorising birth[19] and pubertal[20] status, 3-D assessments[21], and body composition[22] were explored, and new GLI-coefficients for interpreting spirometry from South-Asians were derived[9].

Materials and Methods

The Size and Lung function In Children (SLIC) study was a prospective study designed to assess spirometry and body size, shape and composition in a population of multi-ethnic children (5-11 years) in London schools. Following a pilot study (see online supplement (OLS) section1.1), children were recruited between October 2011-July 2013 by taking home recruitment packs for parental consent to participate (OLS: section1.2). All children with parental consent were eligible, although data from those with current and chronic lung disease (e.g. sickle cell disease; cystic fibrosis; current asthma/wheeze) or significant congenital abnormalities were excluded from analysis[18]. Children were sampled in alternate year groups, with spirometry and full assessments of body physique obtained during the first year of data collection in 5, 7 and 9 year-old children, and spirometry plus routine measures of body shape and composition obtained when possible the following year in 6, 8 and 10 year-olds. The study was guided by a Steering Committee, and approved by the London-Hampstead research ethics committee (REC:10/H0720/53). Parental written consent and child verbal assent were obtained prior to assessments.

The study protocol has been published previously[23]. To summarise, during the first year anthropometry included a 3-D photonic scan (based on light technology; OLS: section1.3), standing height and weight, and manual anthropometry including chest and waist dimensions, mid-arm circumference, knee girth, calf circumference and foot length (OLS:TableE1)[23]. At the end of year 1, interim analysis of the 3-D data identified the best linear measures for predicting LF, and manual anthropometry in year 2 was restricted to these measures (see “Data management and statistical analysis” and OLS:section2.1).

Body composition was assessed using bioelectrical impedance analysis, with paired measurements of total body water by deterium dilution in a sub-sample of 607 children, in order to derive ethnic-specific calibration equations to predict fat-free mass[22]. Spirometry was performed to standard protocols using ERS/ATS acceptability and repeatability criteria, adapted for children where appropriate[24]. A parental questionnaire provided details regarding ethnicity (including birth country for child, parents and grandparents), birth status, health, pubertal status and SEC, assessed at individual level with the Family Affluence Score (FAS)[25] and receipt of free school meals, and at area level with the English Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) score based on home postcode[26]. Saliva samples were collected for cotinine analysis to validate parentally reported tobacco smoke exposure (ABS Laboratory Ltd, UK) (OLS:Section1.4). Additional consent was sought to contact the child’s General Practitioner(GP) to supplement information on respiratory health and birth data (OLS:Section2.2: TableE3)[19]. However, due to the low retrieval of data from GPs compared to parents (22% vs. 95%), analysis using birth data were based on parental questionnaires.[19]

Based on parental report, children were broadly categorised as: White(European ancestry), Black-African origin(African or Caribbean descent); South-Asian(Indian, Pakistani, Bangladeshi or Sri Lankan descent) and children of Other/mixed ethnicities(OLS:section3).

Data management and statistical analysis

See OLS:section2 for details.

Interim analysis

Height, age and sex, the major determinants of LF[7], were used in the interim base model. Since height cannot be measured from 3-D scans[21], models were initially developed using manual anthropometry, and subsequently confirmed using 3-D data. On univariable analysis, after adjustment for sex, age and height, most anthropometric measures were significantly associated with FEV1 and FVC (OLS: TableE2). However, on multivariable analysis only sitting height and chest dimensions (width, depth and circumference) remained associated with FEV1 and FVC (OLS:Fig.E2). Results were similar with 3-D data. Consequently, manual assessments in year 2 were limited to chest dimensions, sitting height, standing height and weight (OLS:TableE1).

To emphasise clinical application and express the magnitude of ethnic differences in relation to White children, final analysis was based on LF z-scores for White children[7], together with height and weight z-scores using the British 1990 growth reference[27]. With LF z-scores as the outcomes, the base model included age, sex and log height to balance the GLI-2012 adjustments. Sitting height, followed by the three chest dimensions (all log-transformed to allow for allometric scaling), were then added to the model (OLS:TableE6). Models were compared using the Bayesian information criterion (BIC)[28], a smaller BIC indicating a better fit. The additional contributions of lean mass and SEC (quintiles of IMD or categories of FAS) to the best model were also tested, as were interactions between ethnicity and anthropometry or SEC. The two-tailed significance level was set at 0.05. The “nlme” package in R (v3.1.0) was used to account for individual clustering[29].

To ascertain the appropriateness of the GLI-equations for multi-ethnic school-children, LF results were also expressed as ethnic-specific z-scores[7], those for South-Asian children being based on a preliminary GLI-coefficient derived for this group[9,10]. One-way ANOVA was used to assess differences in LF and growth between ethnic groups and FAS categories.

Results

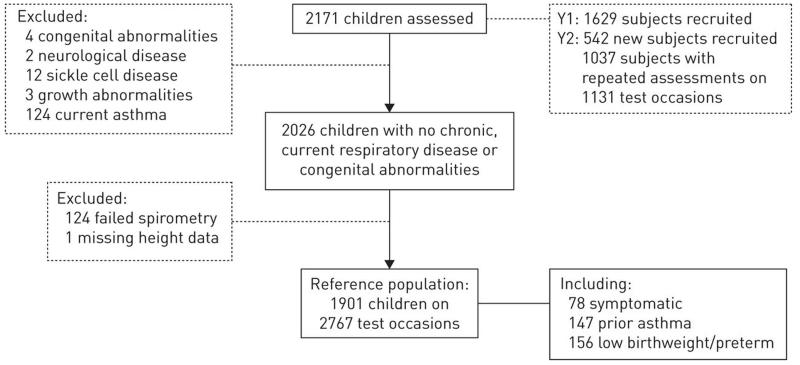

2171 children (mean (range) age: 8.2 (5.2-11.8) years, 47% boys; 34% White; 29% Black-African origin; 25% South-Asian; 12% Other/mixed ethnicity) participated. After exclusions, data from 1901 children (mean (SD) 8.3 (1.6) years, 46% boys) on 2767 test occasions were included (hereafter referred to as the reference population; Figure 1)[18].

Figure 1. Children participating in the SLIC study.

Data from 82 children recruited from the pilot study were also included in the analysis. Not all children recruited in Year 1 participated in the follow-up due to having moved schools or no parental consent received, whereas some children who had not been assessed in year 1 participated in the follow up.

Sex and age were distributed similarly across the ethnic groups (Table 1; OLS,Table E5). On average, 6% of children were born preterm (<37wks gestation) and 7% were low birthweight (<2.5kg), the latter disproportionately South-Asian. Prior wheeze and current symptoms were relatively uncommon (9% and 7% respectively), although 13% of Other/mixed ethnicity children reported previous asthma. According to parental report, 18% of children >8years of age had started puberty[20].

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the reference population (n = 1901) on their first test occasion.

| White | Black | South-Asian | Other | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 664 | 543 | 462 | 232 |

| % boys | 48% | 42% | 48% | 45% |

| Age (years)* | 8.2 (1.6) | 8.3 (1.6) | 8.3 (1.7) | 8.3 (1.7) |

| Born in UK | 87% (566/654) | 86% (430/502) | 79% (357/452) | 90% (203/226) |

| English dominant language | 77% (370/482) | 76% (183/242) | 46% (164/353) | 84% (134/159) |

| Neonatal characteristics | ||||

| Low birth weight (<2.5 kg) | 4.4% | 6.6% | 11% | 9.5% |

| Preterm (GA< 37 weeks) | 5.0% | 7.0% | 5.8% | 5.6% |

| Respiratory history | ||||

| Prior wheeze | 5.8% (35/602) | 8.7% (37/424) | 7.7% (31/401) | 8.1% (16/197) |

| Prior asthma | 7.8% | 9.6% | 5.2% | 12.9% |

| Symptomatic on test day | 6.3% | 5.9% | 6.3% | 3.4% |

| Socio-economic circumstances | ||||

| Receiving free school meals | 19% (115/608) | 53% (198/373) | 12% (52/430) | 32% (63/198) |

| High FAS (5-6): Least deprived | 30% (190/625) | 11% (49/444) | 21% (95/449) | 27% (57/215) |

| Low FAS (0-1): Most deprived | 7.2% (45/625) | 15% (67/444) | 8.0% (36/449) | 7.4% (16/215) |

| IMD: Least deprived (1st quintile) | 11% (73/657) | 0.8% (4/524) | 0% (80/458) | 6.3% (14/224) |

| IMD: Most deprived (5th quintile) | 28% (186/657) | 65% (343/524) | 22% (99/458) | 43% (97/224) |

| Smoking exposure | ||||

| Maternal smoking in pregnancy | 7.5% (49/650) | 1.6% (8/494) | 1.8% (8/451) | 7.2% (16/221) |

| Household smoking | 31% (175/573) | 13% (49/365) | 19% (68/366) | 34% (67/196) |

| Child’s salivary cotinine (ng/mL)† | 0 (0-0.2) | 0 (0-0) | 0 (0-0) | 0 (0-0.03) |

Data are presented as % unless otherwise specified. For variables with missing information the exact numbers on which the percentages were calculated are shown in parentheses.

mean (SD);

Ethnic differences in body physique

Adjusted for age and sex, Black-African origin children were significantly heavier and taller with longer legs than children from other ethnic groups (Table 2, Table E5). Adjusted for sex, age and height, chest circumference was significantly larger and ratio of chest depth/width significantly higher in Black-African origin than White children, but chest area did not differ. Compared with White children, after adjusting for sex, age and height, fat-free mass was on average higher in Black-African origin children (difference [95%CI]:0.7 kg[0.5;0.9)], lower in South-Asians (−1.4 kg[−1.7;-1.2]) and similar in those of Other/mixed ethnicity.

Table 2.

Anthropometry and lung function according to ethnicity (n=2767).

| White | Black | South Asian | Other | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subjects, N | 664 | 543 | 462 | 232 |

| Test occasions, N | 1000 | 805 | 623 | 339 |

| Age (years) | 8.5 (1.6) | 8.6 (1.6) | 8.5 (1.7) | 8.5 (1.7) |

| Z-scores based on British 1990 reference[27] | ||||

| Weight | 0.37 (1.0) | 1.04 (1.1) | 0.05 (1.3) | 0.48 (1.2) |

| Height | 0.30 (1.0) | 0.93 (1.0) | 0.14 (1.1) | 0.36 (1.1) |

| Sit/Stand height | 0.54 (0.01) | 0.52 (0.02) | 0.53 (0.01) | 0.53 (0.02) |

| Z-scores based on GLI-2012 reference (White)[7] | ||||

| FEV1 | −0.01 (0.9) | −1.29 (0.9) | −0.88 (0.8) | −0.49 (0.9) |

| FVC | 0.15 (0.8) | −1.08 (0.9) | −0.80 (0.8) | −0.32 (0.9) |

| FEV1/FVC | −0.33 (0.8) | −0.43 (1) | −0.17 (0.9) | −0.34 (0.9) |

| Z-scores based on GLI-2012 reference (Ethnic-specific)[7,9] | ||||

| FEV1 | −0.01 (0.9) | −0.12 (0.9) | 0.06 (1.0) | 0.10 (0.9) |

| FVC | 0.15 (0.8) | 0.16 (1.0) | 0.05 (1.0) | 0.41 (1.0) |

| FEV1/FVC | −0.33 (0.8) | −0.54 (1.0) | 0.12 (1.0) | −0.56 (1.0) |

Results are presented as mean (SD), derived directly from published equations

Ethnic differences in SEC and tobacco smoke exposure

Overall, 27% of children were receiving free school meals, with Black-African origin children representing the highest proportion (Table 1). Similarly, relatively more Black-African origin children scored low on FAS and IMD (Tables 1 and E4). White and Other ethnicity children experienced most smoke exposure (Table 1). Salivary cotinine levels were <2.5ng/mL in 99.7% of children with no reported household smoking, whereas for cotinine levels >2.5ng/ml (range 2.6-10.9ng/mL indicative of passive smoke exposure) 89% reported household smoking. Cotinine levels (21.1ng/mL) indicative of active smoking[30] were only observed in one 8.7year-old from a reportedly non-smoking household.

Ethnic differences in lung function

Based on White GLI-2012 equations, mean(SD) FVC and FEV1 z-scores approximated 0(1) in White children indicating that these equations are appropriate for contemporary White London schoolchildren(Table 2). Mean z-FEV1 was significantly (p<0.0001) lower in all other ethnic groups: −1.32 in Black-African origin, −0.89 in South-Asian and −0.51 in Other/mixed ethnicity children(Table 3). The pattern was similar for FVC. By contrast there were no significant ethnic differences in FEV1/FVC. When z-scores were based on the GLI-2012 ethnic-specific equations, mean(SD) for FVC and FEV1 approximated 0(1), indicating a good fit, for all but the Other/mixed group, although FEV1/FVC was somewhat lower than predicted among Black-African origin children(Table 2).

Table 3.

Differences in FEV1 and FVC z-scores (GLI-White) by ethnicity relative to White subjects, partially and fully adjusted for sex, age and anthropometry (N = 2751)*.

| Adjusted for | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| sex, age, Ht | sex, age, Ht, SHt | sex, age, Ht, SHt, ChW | |

| z-FEV1 | |||

| Black | −1.32 (−1.4; −1.2) | −1.17 (−1.3; −1.1) | −1.18 (−1.3; −1.1) |

| South Asian | −0.89 (−1.0; −0.8) | −0.77 (−0.9; −0.7) | −0.76 (−0.9; −0.7) |

| Other/ mixed | −0.51 (−0.6; −0.4) | −0.46 (−0.6; −0.3) | −0.47 (−0.6; −0.3) |

| BIC; df | 6277; 9 | 6218; 10 | 6183; 11 |

| z-FVC | |||

| Black | −1.27 (−1.4; −1.2) | −1.09 (−1.2; −1) | −1.11 (−1.2; −1) |

| South Asian | −0.95 (−1.0; −0.9) | −0.80 (−0.9; −0.7) | −0.80 (−0.9; −0.7) |

| Other/ mixed | −0.47 (−0.6; −0.3) | −0.42 (−0.5; −0.3) | −0.43 (−0.5; −0.3) |

| BIC; df | 6188; 9 | 6101; 10 | 5993; 11 |

Data presented as β-coefficient (95% Confidence Interval), derived from modelling;

Analyses based on data from 2751 occasions with full anthropometric data. Abbreviations: Ht: height, SHt: sitting height, ChW: chest width, BIC: Bayesian information criterion, df: degrees of freedom. After further adjusting for sitting height, ethnic differences in zFEV1 and zFVC were further reduced by 11% and 14% respectively in Black-African origin children, by 13% and 16% respectively in South-Asian children and by 10% and 11% respectively in “Other/Mixed” ethnicity children.

Contribution of body physique to ethnic differences in lung function

The best models for both FEV1 and FVC included sitting height and chest width (in addition to age, sex, height and ethnicity) (see OLS:Table E6 for variables included in the modelling). Adjustment for sitting height reduced the differences attributable to ethnicity by 12% in children of Black-African origin (i.e. from −1.32 to −1.17 z-scores), 13% in South-Asian children and 8% in children of Other/mixed ethnicity(Table 3). Further adjustment for chest width significantly improved the fit (p<0.0001) but did not affect the magnitude of ethnic differences(Table 3). Results were similar for FVC(Table 3). Although fat-free mass contributed significantly to FVC, the coefficients for ethnicity changed negligibly (<0.05 z-score). Interactions of lean mass with ethnicity were non-significant.

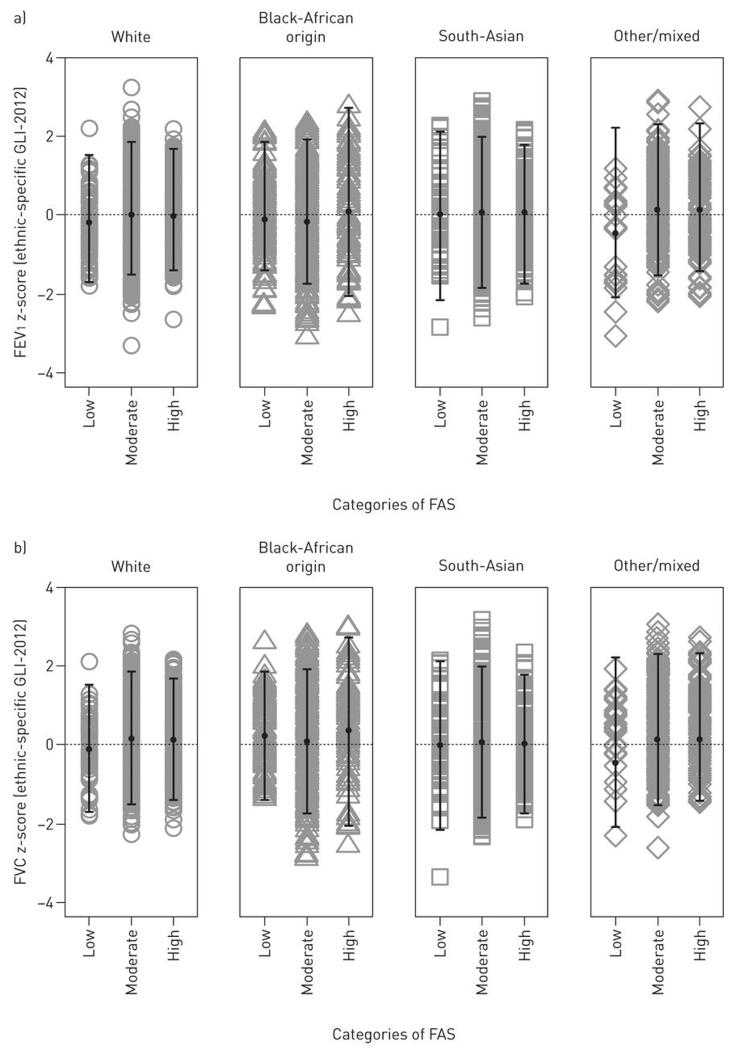

Contribution of SEC to ethnic differences in lung function and somatic growth

The FAS was used to illustrate associations between SEC, LF and growth. Although Black-African origin children were taller and heavier than other groups (Table 2), no differences between distribution of LF or growth (adjusted for age and sex) and categories of FAS in any ethnic group were observed (p>0.05, Figures 2 and E4,OLS). SEC did not contribute significantly, and ethnic differences in FEV1 and FVC changed by <0.01 z-scores (<0.01%) when SEC was included(Table 4). Interactions of SEC by ethnic group were also non-significant. Neither maternal smoking during pregnancy nor current exposure to household smoking contributed significantly or had any effect on the ethnicity coefficients.

Figure 2. Associations between socio-economic circumstances with lung function outcomes according to ethnicity.

No differences in lung function between categories of FAS were evident in each ethnic group. Dots represent mean values, error bars represent ±2SDs from the mean.

Table 4.

FEV1 and FVC z-score (GLI-White) by ethnicity relative to White subjects, adjusted for socio-economic indices (N = 2547)*.

| Adjusted for age, sex, Ht, SHt, ChW | Further adjusted for Family affluence scale | |

|---|---|---|

| z-FEV1 | ||

| Black | −1.17 (−1.3; −1.1) | −1.16 (−1.3; −1.0) |

| South Asian | −0.74 (−0.8; −0.6) | −0.73 (−0.8; −0.6) |

| Other/ mixed | −0.45 (−0.6; −0.3) | −0.45 (−0.6; −0.3) |

| BIC; df | 5668; 11 | 5680; 13 |

| z-FVC | ||

| Black | −1.11 (−1.2; −1.0) | −1.09(−1.2; −1.0) |

| South Asian | −0.77 (−0.9; −0.7) | −0.77 (−0.9; −0.7) |

| Other/ mixed | −0.43 (−0.6; −0.3) | −0.43 (−0.6; −0.3) |

| BIC; df | 5495; 11 | 5508; 13 |

Data presented as β-coefficient (95% Confidence Interval);

Analyses based on data from 2751 occasions with full anthropometric data and family affluence scale. Abbreviations: Ht: height, SHt: sitting height, ChW: chest width, BIC: Bayesian information criterion, df: degrees of freedom.

Discussion

Based on a large multi-ethnic population of London school children, we have demonstrated that after adjusting for sex, age and standing height, when compared with White children, spirometric LF is lower by ~1.3 z-scores (16% predicted) in children of Black-African origin, ~0.9 z-scores (10% predicted) in South-Asian and ~0.5 z-scores (6% predicted) in children of Other/mixed ethnicity. Further adjustment for sitting height reduced these ethnic differences by 10-16%(Table 3). Chest dimensions and lean mass also significantly predict FEV1 and FVC within each ethnic group, but did not affect differences between groups. The persistence of ethnic differences after adjustment for sitting height, chest dimensions, body composition and socio-economic factors emphasises the importance of taking ethnicity into account when interpreting LF data. The GLI ethnic-specific equations for FEV1 and FVC provided a good fit for children of Black-African and South-Asian origin, but less so for those categorised as ‘other/mixed’. Offsets for mean FEV1 and FVC z-scores among Black-African origin children, although small, were in opposite directions, such that mean FEV1/FVC was 0.54 z scores lower than predicted for this group.

Strengths and limitations

Ours is the largest study to date of LF, anthropometry and background characteristics in a multi-ethnic population of school children aged 5-11y, demonstrating the feasibility of undertaking a wide range of complex physiological assessments in young children under field conditions. As the association between BMI and body fatness is affected by ethnicity, we maximised prediction of body composition in these children using a calibration study[22] to ensure ethnic bias were adjusted adequately. A major strength of the study was that observers were highly trained and equipment, techniques and quality control were standardised, minimising potential bias. We have previously shown that in a large epidemiological study such as this inclusion criteria can be relatively inclusive without biasing the results[18]. Since the proportions of children with low birthweight, preterm birth or history of wheeze or asthma were similar across the ethnic groups to that currently reported across England[31] and to other populations of multi-ethnic inner city school children[32], findings from this study should be generalisable.

A potential limitation of this study was that FAS is an asset measure at one time point which may not capture SEC adequately. We attempted to collect information on parental occupation and education from questionnaires but these were incomplete. Attempts were also made to collect birth data via health records from GPs in primary care clinics. However, given the low retrieval of data from GPs compared to parents, and the assumption that parents would generally recall details had their child been born preterm or with low birthweight, in this study children with missing birth information were assumed to have been “full term” with appropriate birthweight. While reliance on parental recall regarding birthweight and gestational age may[33] or may not generate bias[34], we found good agreement between parental reports and health records regarding birth status[19]. Categorisation of ethnicity based on grandparental origins and criteria used in the UK national census addressed genetic, environmental and cultural sources of variability. However, their respective contributions to phenotype cannot be investigated until funding becomes available to analyse DNA samples collected as part of this study to investigate associations between genotype and LF.

Impact of body physique on ethnic differences in lung function

Compared with White children, ethnic differences in LF z-scores between Black-African origin and Other/mixed ethnicity children were similar in magnitude to those in the GLI-2012 reference, while data from South-Asian children were similar to those for South-East Asians[7] and middle class Bangalore children[10]. Of the numerous additional anthropometric measurements undertaken to quantify body physique, only sitting height and chest width significantly predicted spirometric LF. Relatively longer legs (i.e. shorter trunk) naturally predict a smaller chest and lung volume for given standing height. Although these findings match those of the DASH study of multi-ethnic London adolescents[4], others report minimal impact of chest dimensions among South-Asian children[3]. Our weak association of chest shape with LF was surprising, but may reflect the fact that growth in young children occurs primarily in the long bones (i.e. legs), with the trunkal growth spurt occurring later in puberty[35,36]. Growth rate differs by sex before and during puberty[27] with varying timing of pubertal maturation between ethnicities. Furthermore, some factors affecting chest size such as diaphragmatic position or muscle strength cannot be assessed by anthropometry. Although there is preliminary evidence of ethnic differences in residual volume/total lung capacity in children[37], it was not feasible to undertake plethysmographic assessments within our large, school-based study.

Impact of socio-economic circumstances and tobacco exposure

Although SEC and LF are associated[4,12], adjusting for body size (specifically sitting height) reduces the contribution of SEC to ethnic variability[1,4]. While we cannot exclude the potential contribution of unmeasured social and environmental factors, across a wide range of SEC, its association with LF in this study was minimal and statistically insignificant (as also found in a longitudinal study of urban adults[38]). This is in marked contrast to our recent study in India using identical equipment and techniques[10] where, after adjusting for known confounders, average FEV1 and FVC in urban Indian children were similar to UK-Indian children, but significantly higher than in semi-urban and rural Indian children (by ~6% and ~11% respectively). These findings probably reflect marked differences in degree of social deprivation between UK and India[10,12] and suggest that there may be a threshold effect of poverty.

White and Other/mixed ethnicity children were most exposed to passive smoking, but in contrast to previous reports[39] we found no association of LF with maternal smoking either in pregnancy or currently. Exposure may have been under-reported due to recall bias or social stigma, but overall the children’s salivary cotinine levels were very low.

Relevance in Clinical practice

As reported previously[8], results from this study verify the validity of the GLI ethnic-specific equations, which proved to be generally appropriate for London schoolchildren. The slightly poorer fit to the other/mixed group was not unexpected, given the relatively small numbers and heterogeneous nature of this group. Although there were only very small offsets for mean FEV1 and FVC z-scores among Black-African origin children, these were in opposite directions, such that mean FEV1/FVC was 0.54 z scores lower than predicted for this group. However, by setting the lower limit of normal at −1.96 z-scores (2.5th centile), rather than −1.64 (5th centile), as recommended for epidemiological studies such as this[7], the risk of over-diagnosis of airway obstruction in this group can be minimised.

Future directions

Results from this study and others indicate that further adjustment for sitting height improves LF prediction. The GLI-2012 multi-ethnic equations fit many populations well[8,40] and are currently the best option for use in multi-ethnic populations, but are based on standing height. When used in developed countries where LF has been stable for >40 years[7] such an approach probably suffices. Given the generally excellent fit of our data to the GLI all-age reference ranges, the limited age range of the SLIC population and the fact that accurate measurements of sitting height and chest width are unlikely to be recorded during routine clinical assessments, we have not presented any new equations based on the SLIC data, but instead recommend continued usage of the current GLI equations in both research and clinical practice. Despite their contribution to model fit and a relative narrowing of confidence intervals, inclusion of sitting height and/or chest width made minimal impact to predicted median values based on data from London schoolchildren (see OLS Figure E5 for details). However, to take account of secular changes in body proportions in developing countries sitting height could usefully be included in future assessments. Inclusion of chest measurements within a clinical scenario may be less practical.

Conclusion

After adjustment for sex, age and height, ethnic differences in spirometry are reduced by further adjustment for sitting height. However, ethnic differences persist despite adjusting for a wide range of potential determinants, including body physique and socio-economic circumstances. Use of the GLI-2012 multi-ethnic equations largely overcomes such differences in London schoolchildren, demonstrating their validity and relevance in current clinical practice.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would particularly like to thank the Headteachers and staff of participating schools for facilitating the recruitment and school assessments and in particular the children and families who participated in this study.

Funding support: This work was supported by the Wellcome Trust [WT094129MA], Asthma UK [10/013] and the Child Growth Foundation. TJC is funded by MRC research grant MR/J004839/1. The SLIC study team acknowledges the support of the National Institute for Health Research, through the Comprehensive Clinical Research Network.

Footnotes

Competing interests

None

This article has supplementary material available from erj.ersjournals.com

Publisher's Disclaimer: “This is an author-submitted, peer-reviewed version of a manuscript that has been accepted for publication in the European Respiratory Journal, prior to copy-editing, formatting and typesetting. This version of the manuscript may not be duplicated or reproduced without prior permission from the copyright owner, the European Respiratory Society. The publisher is not responsible or liable for any errors or omissions in this version of the manuscript or in any version derived from it by any other parties. The final, copy-edited, published article, which is the version of record, is available without a subscription 18 months after the date of issue publication.”

References

- 1.Harik-Khan RI, Muller DC, Wise RA. Racial difference in lung function in African-American and White children: effect of anthropometric, socioeconomic, nutritional, and environmental factors. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;160(9):893–900. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pellegrino R, Viegi G, Brusasco V, Crapo RO, Burgos F, Casaburi R, Coates A, van der Grinten CP, Gustafsson P, Hankinson J, Jensen R, Johnson DC, MacIntyre N, McKay R, Miller MR, Navajas D, Pedersen OF, Wanger J. Interpretative strategies for lung function tests. Eur Respir J. 2005;26(5):948–68. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00035205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Whittaker AL, Sutton AJ, Beardsmore CS. Are ethnic differences in lung function explained by chest size? Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2005;90(5):F423–8. doi: 10.1136/adc.2004.062497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Whitrow MJ, Harding S. Ethnic differences in adolescent lung function: anthropometric, socioeconomic, and psychosocial factors. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177(11):1262–7. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200706-867OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kumar R, Seibold MA, Aldrich MC, Williams LK, Reiner AP, Colangelo L, Galanter J, Gignoux C, Hu D, Sen S, Choudhry S, Peterson EL, Rodriguez-Santana J, Rodriguez-Cintron W, Nalls MA, Leak TS, O'Meara E, Meibohm B, Kritchevsky SB, Li R, Harris TB, Nickerson DA, Fornage M, Enright P, Ziv E, Smith LJ, Liu K, Burchard EG. Genetic ancestry in lung-function predictions. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(4):321–30. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0907897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stanojevic S, Wade A, Stocks J. Reference values for lung function: past, present and future. Eur Respir J. 2010;36(1):12–9. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00143209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Quanjer PH, Stanojevic S, Cole TJ, Baur X, Hall GL, Culver BH, Enright PL, Hankinson JL, Ip MS, Zheng J, Stocks J. Multi-ethnic reference values for spirometry for the 3-95-yr age range: the global lung function 2012 equations. Eur Respir J. 2012;40(6):1324–43. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00080312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bonner R, Lum S, Stocks J, Kirkby J, Wade A, Sonnappa S. Applicability of the global lung function spirometry equations in contemporary multiethnic children. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188(4):515–6. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201212-2208LE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kirkby J, Lum S, Stocks J, Bonner R, Sonnappa S. Adaptation of the GLI-2012 spirometry reference equations for use in Indian children. Eur Respir J. 2014;44(Suppl 58):191. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sonnappa S, Lum S, Kirkby J, Bonner R, Wade A, Subramanya V, Lakshman PT, Rajan B, Nooyi SC, Stocks J. Disparities in Pulmonary Function in Healthy Children across the Indian Urban-Rural Continuum. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;191(1):79–86. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201406-1049OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wells JC, Ruto A, Treleaven P. Whole-body three-dimensional photonic scanning: a new technique for obesity research and clinical practice. Int J Obes (Lond) 2008;32(2):232–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Raju PS, Prasad KV, Ramana YV, Balakrishna N, Murthy KJ. Influence of socioeconomic status on lung function and prediction equations in Indian children. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2005;39(6):528–36. doi: 10.1002/ppul.20206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duong M, Islam S, Rangarajan S, Teo K, O'Byrne PM, Schunemann HJ, Igumbor E, Chifamba J, Liu L, Li W, Ismail T, Shankar K, Shahid M, Vijayakumar K, Yusuf R, Zatonska K, Oguz A, Rosengren A, Heidari H, Almahmeed W, Diaz R, Oliveira G, Lopez-Jaramillo P, Seron P, Killian K, Yusuf S. Global differences in lung function by region (PURE): an international, community-based prospective study. The lancet Respiratory medicine. 2013;1(8):599–609. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(13)70164-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burney P, Hooper R. The use of ethnically specific norms for ventilatory function in African-American and white populations. Int J Epidemiol. 2012;41(3):782–90. doi: 10.1093/ije/dys011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harik-Khan RI, Fleg JL, Muller DC, Wise RA. The effect of anthropometric and socioeconomic factors on the racial difference in lung function. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164(9):1647–54. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.9.2106075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brehm JM, Acosta-Perez E, Klei L, Roeder K, Barmada MM, Boutaoui N, Forno E, Cloutier MM, Datta S, Kelly R, Paul K, Sylvia J, Calvert D, Thornton-Thompson S, Wakefield D, Litonjua AA, Alvarez M, Colon-Semidey A, Canino G, Celedon JC. African ancestry and lung function in Puerto Rican children. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129(6):1484–90.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.03.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Strippoli MP, Kuehni CE, Dogaru CM, Spycher BD, McNally T, Silverman M, Beardsmore CS. Etiology of ethnic differences in childhood spirometry. Pediatrics. 2013;131(6):e1842–9. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-3003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lum S, Bountziouka V, Sonnappa S, Cole TJ, Bonner R, Stocks J. How “healthy” should children be when selecting reference samples for spirometry? Eur Respir J. 2015;45(6):1576–81. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00223814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bonner R, Bountziouka V, Stocks J, Harding S, Wade A, Griffiths C, Sears D, Fothergill H, Slevin H, Lum S. Birth data accessibility via primary care health records to classify health status in a multi-ethnic population of children: an observational study. NPJ primary care respiratory medicine. 2015;25:14112. doi: 10.1038/npjpcrm.2014.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lum S, Bountziouka V, Harding S, Wade A, Lee S, Stocks J. Assessing pubertal status in multi-ethnic primary schoolchildren. Acta paediatrica. 2015;104(1):e45–8. doi: 10.1111/apa.12850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wells JC, Stocks J, Bonner R, Raywood E, Legg S, Lee S, Treleaven P, Lum S. Acceptability, Precision and Accuracy of 3D Photonic Scanning for Measurement of Body Shape in a Multi-Ethnic Sample of Children Aged 5-11 Years: The SLIC Study. PLoS One. 2015;10(4):e0124193. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0124193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee S, Bountziouka V, Lum S, Stocks J, Bonner R, Naik M, Fothergill H, Wells JC. Ethnic variability in body size, proportions and composition in children aged 5 to 11 years: is ethnic-specific calibration of bioelectrical impedance required? PLoS One. 2014;9(12):1–17. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0113883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lum S, Sonnappa S, Wade A, Harding S, Wells J, Treleaven P, Cole TJ, Griffiths CJ, Kelly F, Bonner R, Bountziouka V, Kirkby J, Lee S, Raywood E, Legg S, Sears D, Stocks J. Exploring ethnic differences in lung function: the Size and Lung function In Children (SLIC) study protocol and feasibility. UCL Institute of Child Health; London, UK: 2014. http://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/1417500/ [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kirkby J, Welsh L, Lum S, Fawke J, Rowell V, Thomas S, Marlow N, Stocks J, Group EPS The EPICure study: comparison of pediatric spirometry in community and laboratory settings. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2008;43(12):1233–41. doi: 10.1002/ppul.20950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Andersen A, Krolner R, Currie C, Dallago L, Due P, Richter M, Orkenyi A, Holstein BE. High agreement on family affluence between children's and parents' reports: international study of 11-year-old children. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2008;62(12):1092–4. doi: 10.1136/jech.2007.065169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Government DfCaL . English indices of deprivation 2010 [Report] England; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cole TJ, Freeman JV, Preece MA. British 1990 growth reference centiles for weight, height, body mass index and head circumference fitted by maximum penalized likelihood. Statistics in medicine. 1998;17(4):407–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schwarz GE. Estimating the dimension of a model. Ann Statist. 1978;6(2):461–4. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pinheiro J, Bates D, DebRoy S, Sarkar D, R_Core_Team nlme: Linear and nonlinear mixed effects models. R package version 31-1182014.

- 30.Jarvis MJ, Fidler J, Mindell J, Feyerabend C, West R. Assessing smoking status in children, adolescents and adults: cotinine cut-points revisited. Addiction. 2008;103(9):1553–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02297.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Simpson CR, Sheikh A. Trends in the epidemiology of asthma in England: a national study of 333,294 patients. J R Soc Med. 2010;103(3):98–106. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.2009.090348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Whitrow MJ, Harding S. Asthma in Black African, Black Caribbean and South Asian adolescents in the MRC DASH study: a cross sectional analysis. BMC Pediatr. 2010;10:18. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-10-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jaspers M, de Meer G, Verhulst FC, Ormel J, Reijneveld SA. Limited validity of parental recall on pregnancy, birth, and early childhood at child age 10 years. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63(2):185–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Catov JM, Newman AB, Kelsey SF, Roberts JM, Sutton-Tyrrell KC, Garcia M, Ayonayon HN, Tylavsky F, Ness RB. Accuracy and reliability of maternal recall of infant birth weight among older women. Ann Epidemiol. 2006;16(6):429–31. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2005.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tanner JM. Growth at adolescence. 2nd edition Blackwell Scientific Publications; Oxford: 1962. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cole TJ. Secular trends in growth. Proc Nutr Soc. 2000;59(2):317–24. doi: 10.1017/s0029665100000355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kirkby J, Bonner R, Lum S, Bates P, Morgan V, Strunk RC, Kirkham F, Sonnappa S, Stocks J. Interpretation of pediatric lung function: impact of ethnicity. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2013;48(1):20–6. doi: 10.1002/ppul.22538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Menezes AM, Wehrmeister FC, Hartwig FP, Perez-Padilla R, Gigante DP, Barros FC, Oliveira IO, Ferreira GD, Horta BL. African ancestry, lung function and the effect of genetics. Eur Respir J. 2015;45(6):1582–9. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00112114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Carlsen KH, Carlsen KC. Respiratory effects of tobacco smoking on infants and young children. Paediatric respiratory reviews. 2008;9(1):11–9. doi: 10.1016/j.prrv.2007.11.007. quiz 9-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hall GL, Thompson BR, Stanojevic S, Abramson MJ, Beasley R, Coates A, Dent A, Eckert B, James A, Filsell S, Musk AW, Nolan G, Dixon B, O'Dea C, Savage J, Stocks J, Swanney MP. The Global Lung Initiative 2012 reference values reflect contemporary Australasian spirometry. Respirology. 2012;17(7):1150–1. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2012.02232.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.