Abstract

Introduction:

Tobacco chewing, smoking, and alcohol consumption are major contributing factors in the development of oral carcinoma. India has world's highest number of oral cancers (almost 20%) and approximately 1% of the Indian population has oral premalignant lesions.

Aim:

The purpose of the study was to evaluate the epidemiological factors and clinical profile of oral cancer cases in our hospital.

Settings:

Department of Surgical Oncology, King George's Medical University, Lucknow, India.

Materials and Methods:

A retrospective study was conducted from January 2010 to December 2012 on 479 cases with histopathologically confirmed oral carcinoma. Subjects’ details of age, sex, occupation, tobacco consumption, site of carcinoma, and stage at presentation were recorded.

Results:

Mean age in this study was 47.84 years with male to female ratio of 3.1:1.0. Buccal mucosa and alveolus were the most affected sites. The majority of cases were from socially and economically weaker section, with 93.72% cases being tobacco users. The majority of cases were advance stage (Stage III and IV) with Stage IV being the predominant stage at presentation followed by Stage III.

Conclusion:

The findings of the study reveal that tobacco consumption is one of the major contributors in the development of cancer of oral cavity with the majority of cases presenting in advance stages posing a big therapeutic challenge.

Keywords: Buccal mucosa, oral cancer, oral cancer epidemiology

INTRODUCTION

Tobacco consumption is socially and culturally well-accepted in almost every level of society in India. Traditional smokeless forms like betel quid, tobacco with lime are commonly used and areca nut blended products such as gutkha and pan masala are ever-increasing not only among men but also among women, as well in teenagers and children especially in lower socioeconomic strata. Tobacco chewing, smoking, and alcohol consumption are major contributing factors for oral carcinoma. A small percentage of oral cancer cases are seen in the persons who do not use tobacco. Several studies from all over the world demonstrate smoking and smokeless tobacco products as etiological factors for oral cancer.[1] Alcohol consumption further increases this risk.[2] India has the dubious distinction of harboring world's highest number (nearly 20%) of oral cancers. It aptly labeled the oral cancer capital of the world with an estimated 1% of the population having oral premalignant lesions.[3] Human papilloma virus,[4,5] dietary deficiencies,[6] and poor oral hygiene[7,8] have also been associated with increased risk of oral carcinoma.

The purpose of this retrospective study was to analyze the epidemiological factors and clinical profile of oral cancer cases in a North Indian hospital setting.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Clinical details of 479 histopathologically proven oral cancer patients presenting to Department of Surgical Oncology between January 2010 and December 2012 were analyzed. Details of age, sex, occupation, tobacco habit, and clinical stage at presentation were recorded. Cases were classified according to the tumor-node-metastasis classification of the Union for International Cancer Control (7th edition) staging of carcinoma of oral cavity.[9]

RESULTS

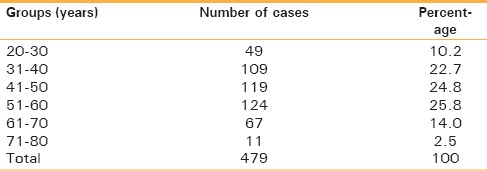

Mean age of presentation of oral carcinoma was 47.84 years in the present study. Of a total of 479 patients, 364 were males (76.0%) and 115 were females (24.0%) [Table 1]. The age distribution of oral cancer cases is shown in Table 2. The largest number of cases in the study (n = 124; [25.8%]) were recorded in age group 51–60 years followed by age group 41–50 (n = 119; [24.8%]). The youngest patient was 20 years old, and the oldest was 80 years of age. Male to female ratio was 3.1:1.0.

Table 1.

Gender information of cases

Table 2.

Age group of cases

The occupational data revealed that majority of the cases (n = 351; [73.2%]) were manual workers, and industrial laborers, followed by the unemployed (n = 67; [14.0%]). The least number of cases were professionals who comprised of only five patients (1.1%). The occupation distribution is shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Occupation of patients

The majority of patients were tobacco users who comprised of 93.7% (449/479) of our patients in this study. The majority of cases (n = 254 [53.0%]) were tobacco chewers only, followed by the group of those who were both smokers and tobacco chewers who represented 156 (32.6%) cases. Thirty-nine (8.2%) cases were only smokers. Thirty (6.2%) patients never consumed tobacco in any form [Table 4].

Table 4.

Tobacco habit

The duration of tobacco habit is listed in Table 5. One hundred and nine patients (22.7%) had the habit of tobacco consumption for 5–14 years while 122 patients (25.5%) had a history of tobacco consumption for 15–24 years. Ten patients (2.1%) had a habit of tobacco consumption for more than 45 years.

Table 5.

Duration of tobacco consumption

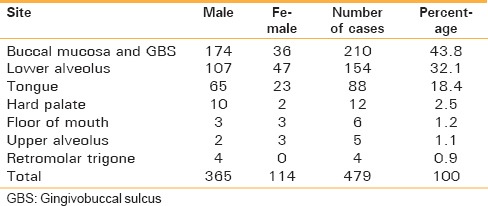

Buccal mucosa and gingivo buccal sulcus were the most common subsites in our study, with 210 (43.8%) patients affected at these sites followed by alveolus, which was the site involved in 154 (32.1%) patients. Tongue cancer was the third major site of carcinoma with 88 patients (18.4%) affected. Few cases of the floor of the mouth and retromolar trigone were also reported [Table 6].

Table 6.

Site of carcinoma

The stage distribution of patients is shown in Table 7. Of 479 patients, 307 (64.1%) patients presented with Stage IV disease, followed by 135 patients (28.2%) with Stage III disease. Two hundred and sixty-five cases (55.3%) had Stage IV-A disease and 39 (8.1%) patients presented with Stage IV-B disease. Three patients presented with Stage IV-C (0.7%) disease. Twenty-four (5.0%) patients presented with Stage II and 13 (2.7%) patients with Stage I disease [Table 7].

Table 7.

Staging#

DISCUSSION

The present study showed that the majority of oral cancer cases (93.7%) were tobacco consumers before being diagnosed with oral carcinoma. Such association of tobacco and development of oral cancer are reported in several studies.[1] Male to female ratio was 3.1:1.0 in this study while some other studies conducted in other parts of India also found a higher male to female ratio.[10,11,12] Males have easy access to tobacco products than females because of social and cultural factors; however, this is slowly losing ground. In this study, the youngest patient was 20-year-old, and the oldest was 80-year-old. The most affected age group was 51–60 years followed by 41–50 years which is consistent with other studies of India.[10,11,12]

Tobacco use occurs in all strata of society, such as illiterate to professional, adolescent to adults, poor to rich etc.; however, gender, occupation, and education influence tobacco use.[13] The majority of patients were from socially and economically weaker section (laborers and farmers) that comprised of 351 (73.2%) patients, who are more prone to consume tobacco because of lower educational level and lack of awareness about consequences of tobacco consumption.

Most of the patients had a duration of tobacco consumption between 15 and 24 years, followed by 5–14 years duration. Smokeless tobacco[14] and tobacco smoke[15] contain multiple carcinogens, and increased exposure enhances the risk for the development of carcinoma of oral cavity.

The cancer of tongue and floor of mouth is more common in Western countries while in Indian subcontinent, the buccal mucosa and gingivo buccal sulcus are more commonly affected due to placement of tobacco quid like khaini, gutkha, betel quid etc.; in oral cavity.[16] Buccal mucosa and gingivo buccal sulcus were the most affected site in the present study. Other Indian epidemiological studies also found similar outcomes.[10,12]

Tobacco consumption in various forms is culturally and socially accepted in our society. Tobacco is more easily available to males because of social factors. Tobacco consumption by females is however increasing gradually.[17] Worldwide initiation age of tobacco consumption is around 12 years.[18,19,20] In India, initiation age of tobacco consumption varies from 8 years to 15 years.[21,22] There is a time lag after the initiation of tobacco consumption and development of oral carcinoma which is well-exemplified in the current study. Many patients of oral cancer were diagnosed in the 20–30 age group or subsequent decades in this study.

Late diagnosis of carcinoma is a major problem of developing countries especially in India, which adversely affects the treatment outcome.[16] We observed the same in the present study as most of the cases were Stage IV (64.1%) followed by Stage III disease (27%).

CONCLUSION

Tobacco consumption is the main etiological factor for the development of carcinoma of the oral cavity in the present study. The majority of cases reported at an advanced stage of the disease which increases the burden of disease and worsens the prognosis. This is the most worrisome observation made in this study. Smokeless tobacco consumed in India is one of the most common forms of tobacco abuse and is the leading cause of cancer in India especially of the buccal mucosa and alveolus. There is need to spread awareness about this tobacco-related cancer and immediate consultation on suspicion of cancer.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Mahendra Pratap Singh is grateful to CSIR, New Delhi for providing fellowship to pursue PhD.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Mahendra Pratap Singh is working as Senior Research Fellow (SRF-NET) of CSIR, New Delhi.

Conflicts of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Misra S, Chaturvedi A, Misra NC. Oral carcinoma. In: Johnson CD, Taylor I, editors. Recent Advances in Surgery. London: Royal Society of Medicine Press; 2002. pp. 71–86. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ogden GR, Wight AJ. Aetiology of oral cancer: Alcohol. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1998;36:247–51. doi: 10.1016/s0266-4356(98)90707-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chaturvedi P. Effective strategies for oral cancer control in India. J Cancer Res Ther. 2012;8(Suppl 1):S55–6. doi: 10.4103/0973-1482.92216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.D’Souza G, Kreimer AR, Viscidi R, Pawlita M, Fakhry C, Koch WM, et al. Case-control study of human papillomavirus and oropharyngeal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(10):1944–56. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa065497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Furniss CS, McClean MD, Smith JF, Bryan J, Applebaum KM, Nelson HH, et al. Human papillomavirus 6 seropositivity is associated with risk of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, independent of tobacco and alcohol use. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:534–41. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sánchez MJ, Martínez C, Nieto A, Castellsagué X, Quintana MJ, Bosch FX, et al. Oral and oropharyngeal cancer in Spain: Influence of dietary patterns. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2003;12:49–56. doi: 10.1097/00008469-200302000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garrote LF, Herrero R, Reyes RM, Vaccarella S, Anta JL, Ferbeye L, et al. Risk factors for cancer of the oral cavity and oro-pharynx in Cuba. Br J Cancer. 2001;85:46–54. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2000.1825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Talamini R, Vaccarella S, Barbone F, Tavani A, La Vecchia C, Herrero R, et al. Oral hygiene, dentition, sexual habits and risk of oral cancer. Br J Cancer. 2000;83:1238–42. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2000.1398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.7th ed. Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley Blackwell; 2010. The Union for International Cancer Control (UICC). TNM Classification of Malignant Tumours. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sharma P, Saxena S, Aggarwal P. Trends in the epidemiology of oral squamous cell carcinoma in Western UP: An institutional study. Indian J Dent Res. 2010;21:316–9. doi: 10.4103/0970-9290.70782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Addala L, Pentapati CK, Reddy Thavanati PK, Anjaneyulu V, Sadhnani MD. Risk factor profiles of head and neck cancer patients of Andhra Pradesh, India. Indian J Cancer. 2012;49:215–9. doi: 10.4103/0019-509X.102865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shenoi R, Devrukhkar V, Chaudhuri, Sharma BK, Sapre SB, Chikhale A. Demographic and clinical profile of oral squamous cell carcinoma patients: A retrospective study. Indian J Cancer. 2012;49:21–6. doi: 10.4103/0019-509X.98910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sorensen G, Gupta PC, Pednekar MS. Social disparities in tobacco use in Mumbai, India: The roles of occupation, education, and gender. Am J Public Health. 2005;95:1003–8. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.045039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoffmann D, Djordjevic MV. Chemical composition and carcinogenicity of smokeless tobacco. Adv Dent Res. 1997;11:322–9. doi: 10.1177/08959374970110030301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hecht SS. Tobacco smoke carcinogens and lung cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91:1194–210. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.14.1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Misra S, Chaturvedi A, Misra NC. Management of gingivobuccal complex cancer. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2008;90:546–53. doi: 10.1308/003588408X301136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Narain R, Sardana S, Gupta S, Sehgal A. Age at initiation and prevalence of tobacco use among school children in Noida, India: A cross-sectional questionnaire based survey. Indian J Med Res. 2011;133:300–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Caraballo RS, Yee SL, Gfroerer JC, Pechacek TF, Henson R. Tobacco use among racial and ethnic population subgroups of adolescents in the United States. Prev Chronic Dis. 2006;3:A39. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kowalewska A. The age of tobacco initiation and tobacco smoking frequency among 15 year-old adolescents in Poland. Przegl Lek. 2008;65:546–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Farrand P, Rowe RM, Johnston A, Murdoch H. Prevalence, age of onset and demographic relationships of different areca nut habits amongst children in Tower Hamlets, London. Br Dent J. 2001;190:150–4. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4800909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kapil U, Goindi G, Singh V, Kaur S, Singh P. Consumption of tobacco, alcohol and betel leaf amongst school children in Delhi. Indian J Pediatr. 2005;72:993. doi: 10.1007/BF02731681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bhojani UM, Chander SJ, Devadasan N. Tobacco use and related factors among pre-university students in a college in Bangalore, India. Natl Med J India. 2009;22:294–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]