Abstract

Human influenza is a highly contagious acute respiratory illness that is responsible for significant morbidity and excess mortality worldwide. In addition to neutralizing antibodies, there are antibodies that bind to influenza virus–infected cells and mediate lysis of the infected cells by natural killer (NK) cells (antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity [ADCC]) or complement (complement-dependent lysis [CDL]). We analyzed sera obtained from 16 healthy adults (18–63 years of age), 52 children (2–17 years of age), and 10 infants (0.75–1 year of age) in the United States, who were unlikely to have been exposed to the avian H7N9 subtype of influenza A virus, by ADCC and CDL assays. As expected, none of these sera had detectable levels of hemagglutination-inhibiting antibodies against the H7N9 virus, but we unexpectedly found high titers of ADCC antibodies to the H7N9 subtype virus in all sera from adults and children aged ≥8 years.

Keywords: avian influenza viruses; H7N9 subtype; H5N1 subtype; antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity; antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity; ADCC, complement-dependent lysis; hemagglutination-inhibition; non-neutralizing antibody

Human influenza is a highly contagious acute respiratory illness that is responsible for significant morbidity and excess mortality worldwide [1]. Influenza A viruses have 8 negative-sense RNA segments as a genome, which encode >11 proteins, and are further divided into subtypes based on the antigenicity of the surface glycoproteins hemagglutinin (HA) and neuraminidase (NA) [2]. Currently there are 18 HA subtypes (H1–18) and 11 NA subtypes (N1–11) defined [3]. Current vaccine approaches against influenza virus depend primarily on the induction of neutralizing antibodies, which is conventionally measured by the hemagglutination-inhibition (HAI) assay [4]. These HAI-positive neutralizing antibodies bind to the globular head of HA [5]. There are HAI-negative neutralizing antibodies, which bind to the stalk (stem) region of the HA and do not inhibit hemagglutination, some of which are subtype-cross-reactive [6–8].

Neutralizing antibodies can bind extracellular virus and block infection, but there are also antibodies that can bind to influenza virus–infected cells and mediate lysis of the infected cells by natural killer (NK) cells, neutrophils, and monocytes (antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity [ADCC]) [9] or by complement (complement-dependent lysis [CDL]). In addition to HA, infected cells express NA, nucleoprotein (NP), and matrix protein 1 (M1) and M2 on their surface. NP is less abundant than HA, NA, or M2, with M1 barely detectable on the infected cell surface [10–12]. Anti-HA and anti-M2 antibodies are known to mediate ADCC and CDL [13–16]. An anti-NP human monoclonal antibody was not found to have CDL activity in vitro [17], although the monoclonal antibody studied may not be representative of anti-NP antibodies in humans. A protective role of nonneutralizing anti-NP antibodies has been suggested in mice [18, 19].

In humans, ADCC antibodies against seasonal influenza viruses were detected at higher levels (1 to 2 logs) than HAI antibodies in children and adults [9, 20], but we found that CDL antibody titers were in a similar range to HAI antibody titers [21]. Previously, we reported that 3 of 10 young adults who were naive to influenza virus A/USSR/77(H1N1) had preexisting CDL antibodies but no HAI antibodies against this subtype [22], and more recently Jegaskanda et al reported that healthy adults who were unlikely to have been exposed to A(H5N1) or A(H1N1)pdm09 had cross-reactive ADCC antibodies to HAs of A(H5N1) and A(H1N1)pdm09 [23]. This suggests that ADCC and CDL antibodies have greater subtype cross-reactivity than conventional neutralizing antibodies, which may have implications for the development of a universal influenza vaccine [24]. In our recent study of young Thai children, we found that ADCC antibody titers against A(H1N1)pdm09 increased with age, whereas CDL or HAI antibodies titers did not [25], suggesting that sets of antibodies contributing to ADCC and CDL activities overlap but are not exactly the same.

ADCC and/or CDL antibodies are nonneutralizing antibodies and are thought to help control viral infection [26, 27]. In influenza virus infection, these nonneutralizing antibodies may be important against novel influenza viruses arising from reassortment with animal influenza A viruses [28], against which the majority of human population have no or very low levels of neutralizing antibodies. The seropositivity for A(H5N1) is considered to be 1%–2% [29]. One seroprevalence study of new avian influenza A(H7N9) viruses in China reported no detectable levels of neutralizing antibodies in 1544 sera collected in 2012 from poultry workers prior to the outbreaks in the area [30]. Another study conducted during the 2013 A(H7N9) outbreak reported that seropositivity for A(H7N9) was 0.8% in the general population but 13.9% among poultry workers [31].

Recently Jegaskanda et al analyzed sera from 62 healthy adult Australians and found 1 serum specimen with ADCC antibodies to A(H7N9) [32]. In the present study, we first analyzed serum samples obtained from infants and adults in the United States using our CDL and ADCC assays and found that all adults and 2 of 10 infants had detectable ADCC antibodies to A(H7N9). We then analyzed sera collected from children aged 2–17 years and observed that titers of ADCC antibodies to A(H7N9) increased with age, which may have been induced by exposure to seasonal influenza viruses.

METHODS

Samples

Samples tested in this study were prevaccination sera obtained from 16 healthy adults (age, 18–63 years) who were about to receive licensed influenza vaccines under an approved University of Massachusetts Medical School (UMMS) Institutional Review Board protocol and random sera obtained from 10 infants ≤1 year old and 52 children 2–17 years old, purchased from a commercial company (Bioreclamation, Westbury, New York).

A whole-blood sample obtained under a UMMS IRB–approved protocol from 1 healthy adult subject was used as a source of NK cells.

Viruses Used

Influenza viruses A/Anhui/1/2013(H7N9), A/Hong Kong/156/97(H5N1), A/Brisbane/59/2007(H1N1), and B/Florida/4/2006 were obtained from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and influenza virus A/Victoria/361/2011(H3N2) was obtained from Biodefense and Emerging Infections Research Resources. All experiments using A/Anhui/1/2013(H7N9) and A/Hong Kong/156/97(H5N1) were performed in the UMMS enhanced biosafety level 3 laboratory.

HAI Assay

HAI assays were performed with 2-fold serial dilutions of serum of 1:5–1:5120, using a standard protocol with some modifications as previously described [33, 34]. For statistical analysis, an undetectable HAI antibody titer was assigned a value of 2.5.

CDL Assay

The CDL assay method was previously described [25]. We used a chromium-release assay to calculate the percentage specific immune lysis (SIL) of infected A549 cells (human lung epithelial cell line; ATCC CCL-185), using 2-fold serial dilutions (1:10–1:1280) of heat-inactivated serum in the presence of Low-Tox Guinea Pig Complement at a final concentration of 1:20 (Cedarlane Laboratories, Burlington, North Carolina). A549 cells were infected at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 5–10 with A/Anhui/1/2013(H7N9) or A/Hong Kong/156/97(H5N1). Experiments were performed in replicates of 3. A549 cells infected with A(H7N9) or A(H5N1) were not lysed by complement alone in our CDL assays. The highest serum dilution showing ≥15% SIL was defined as the CDL antibody end point titer. For statistical analysis, an undetectable CDL antibody titer was assigned a value of 5. Serum from an adult subject with CDL antibodies against seasonal A(H1N1) was included as a positive control in all assays.

ADCC Assay

The ADCC assay method was previously described [25]. We used a chromium-release assay to calculate the percentage SIL of infected A549 cells, using 4-fold serial dilutions (1:20–1:327 680) of heat-inactivated donor serum in the presence of enriched NK cells (RosetteSep Human NK Cell Enrichment Cocktail; Stem Cell Technologies, Canada) isolated from a fresh whole-blood specimen obtained from a healthy subject at an effector:target ratio of 5:1/well. A549 cells were infected at a MOI of 5–10 with A/Anhui/1/2013(H7N9) or A/Hong Kong/156/97(H5N1). Lysis of infected target cells by NK cells alone without sera added was 13.2% and 13.7% against A(H7N9)-infected cells and 11.2% against A(H5N1)-infected cells. When calculating SIL values, data on lysis of NK cells alone were subtracted. The highest serum dilution showing ≥15% SIL was defined as the ADCC antibody end point titer. For statistical analysis, an undetectable ADCC titer was assigned a value of 5, and for end point titers above the range of serum dilutions tested, a titer of 327 680 was assigned. A serum specimen from an adult with ADCC antibodies against seasonal A(H1N1) was included as a positive control in all assays.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using Microsoft Office Excel 2007 and an online utility [35]. All antibody titers were transformed to log10 scale for all computations and comparisons. A P value of <.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

RESULTS

Comparison of Titers of HAI, CDL, and ADCC Antibodies to A/Anhui/1/2013 (H7N9) in US Infants and Adults

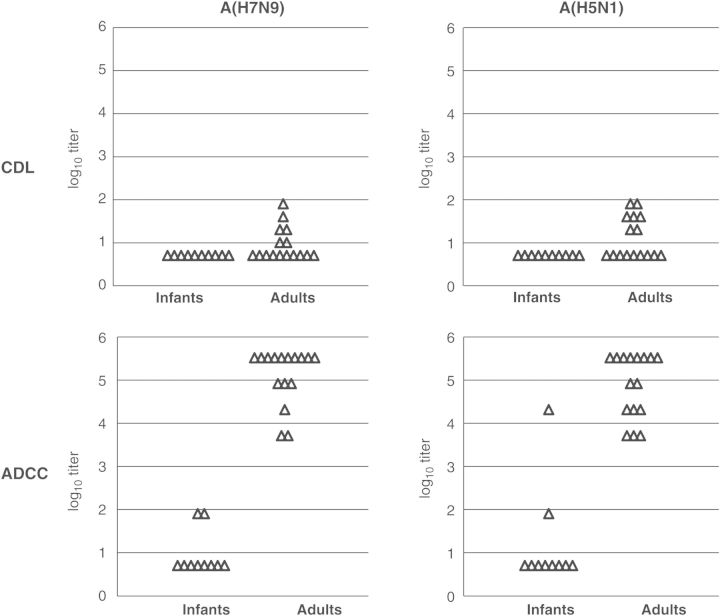

We analyzed HAI, CDL, and ADCC antibodies against A/Anhui/1/2013(H7N9) in serum samples obtained from 10 infants (age, ≤1 year) and 16 adults (age, 18–63 years). We intended to use infant sera as negative controls containing no or few residual maternal antibodies. As expected, there were no subjects with detectable HAI antibodies to the A/Anhui/1/2013(H7N9) (Supplementary Table 1). Sera from 6 of 16 adults had detectable CDL antibodies to this virus. None of the infants had sera with detectable CDL antibodies (Supplementary Table 1 and Figure 1). In contrast, sera from 2 of 10 infants and all adults had detectable ADCC antibodies to the virus (Supplementary Table 1 and Figure 1). Immunoglobulin G (IgG) depletion of an adult serum specimen used as a positive control eliminated ADCC activity against A(H7N9)-infected target cells, and purified IgG from the same serum specimen retained ADCC activity (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Complement-dependent lysis (CDL) and antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) antibody titers to A./Anhui/1/2013(H7N9) and A/Hong Kong/156/97(H5N1) in US infants and adults. The top panels show CDL log10 antibody titers, and the bottom panels show log10 ADCC antibody titers. The left panels show titers against A(H7N9), and the right panels show titers against A(H5N1). The lowest dilution tested was 1:10 in CDL assays (2-fold serial dilutions were used) and 1:20 in ADCC assays (4-fold serial dilutions were used). Samples under the detection limit were plotted at 0.70 in the log10 scale (equivalent to 1:5 dilution) for both assays. The experiment was performed in triplicate. All infant and adult samples were assayed in the same experiment against the same virus.

Comparison of Titers of CDL, ADCC, and HAI Antibodies to A/Hong Kong/156/97(H5N1)

We were interested in whether these findings would be observed for another avian influenza virus, A/Hong Kong/156/97(H5N1). No detectable HAI antibodies to A/Hong Kong/156/97(H5N1) were observed in either adult or infant sera (Supplementary Table 1). Similar to A(H7N9), CDL antibodies to A(H5N1) were not detected in sera from any infants; however, in 7 of 16 adult sera, CDL antibodies were detected (Supplementary Table 1 and Figure 1). Detectable ADCC antibody titers were seen in sera from 2 of 10 infants and all adults (Supplementary Table 1 and Figure 1).

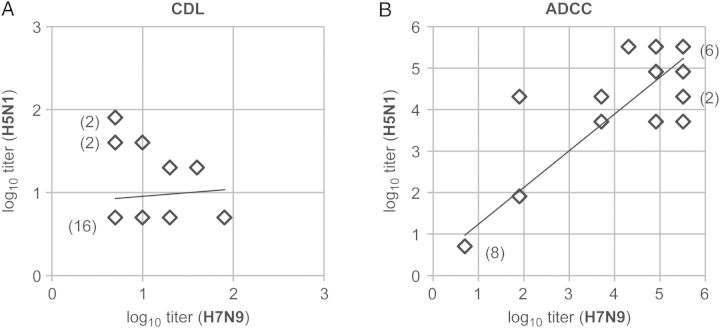

Correlation of Titers of ADCC and CDL Antibodies to A/Anhui/1/2013(H7N9) and A/Hong Kong/156/97(H5N1)

We observed a highly positive (r = 0.93) and significant correlation between A/Anhui/1/2013(H7N9) and A/Hong Kong/156/97(H5N1) ADCC antibody titers in all subjects (P = .0000000000078; Figure 2). Of note, the only 2 infant sera (BRH688264 and BRH688272) that had detectable ADCC antibodies to A/Hong Kong /156/97(H5N1) were the same 2 that had detectable ADCC antibodies to A/Anhui/1/2013(H7N9) (Supplementary Table 1). All adult sera had high titers of ADCC antibodies to both avian influenza viruses.

Figure 2.

Correlation between complement-dependent lysis (CDL) and antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) antibody titers to A/Anhui/1/2013(H7N9) and A/Hong Kong/156/97(H5N1) in US infants and adults. Samples under the detection limit were plotted at 0.70 in the log10 scale (equivalent to a 1:5 dilution) for both assays. Parentheses denote the number of subjects (≥2) with the same titer combination.

Six of the 16 adult serum samples tested had detectable CDL antibodies against A/Anhui/1/2013(H7N9), 7 had detectable CDL antibodies against A/Hong Kong/156/97(H5N1), but only 3 had CDL antibodies to both viruses (Supplementary Table 1 and Figure 2). No infant serum specimen had CDL antibodies against these viruses. Using the χ2 test, we found no correlation between detection of CDL antibodies to A/Anhui/1/2013(H7N9) and detection of those to A/Hong Kong/156/97(H5N1) (data not shown).

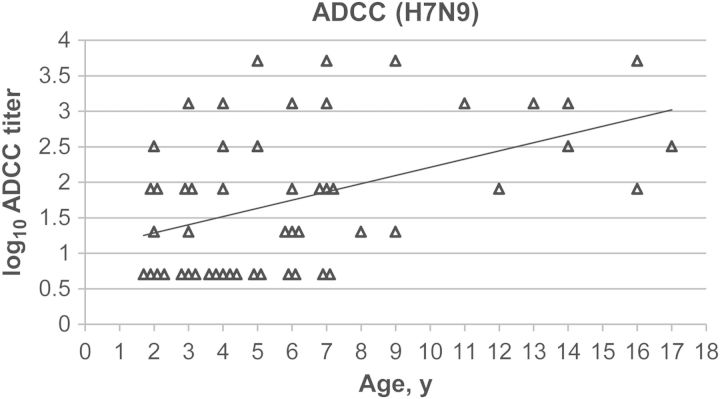

Age Distribution of Titers of ADCC Antibodies to A/Anhui/1/2013(H7N9) in US Children

We analyzed 52 sera from US children aged 2–17 years to determine titers of HAI and ADCC antibodies against A/Anhui/1/2013(H7N9). As expected, no subjects had detectable HAI antibodies to A/Anhui/1/2013(H7N9) (Supplementary Table 2). Thirty-four children had detectable ADCC antibodies against the virus. All samples obtained from children ≥8 years old had detectable ADCC antibodies, and the ADCC antibody titers increased with age (r = 0.49; P = .00069; Supplementary Table 2 and Figure 3). Analysis of samples obtained from children ≤7 years old, however, revealed no significant correlation between ADCC antibody titer and age (r = 0.21; P = .19).

Figure 3.

Age distribution of antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) antibody titers to A/Anhui/1/2013(H7N9) in US children. Samples under detection limit were assigned as a dilution of 1:5 (0.70 on the log10 scale). The experiment was performed in triplicate. All samples were assayed in the same experiment. y = 0.12x + 1.1, r = 0.46, P = .00069.

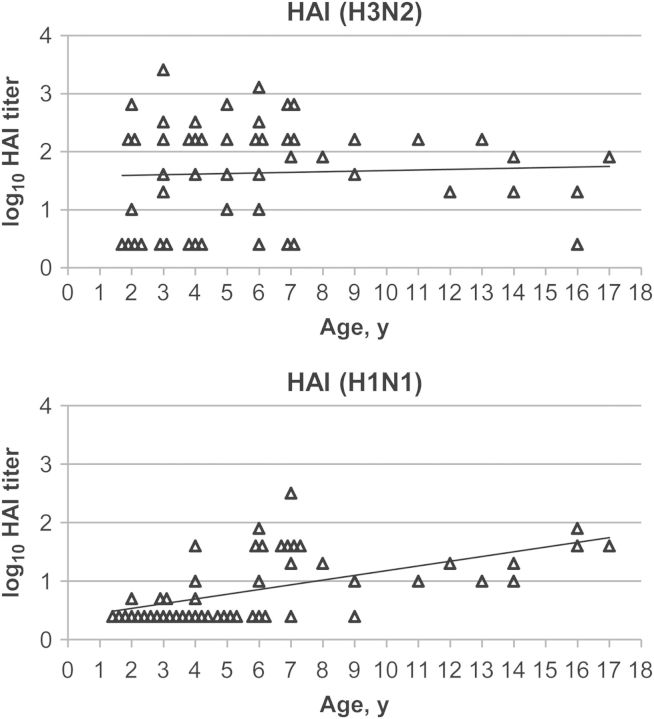

Exposure to Seasonal Influenza Viruses and Generation of ADCC Antibodies Against A/Anhui/1/2013(H7N9)

We hypothesized that children may generate subtype–cross-reactive ADCC antibodies through exposure to seasonal influenza viruses. We analyzed the same 52 serum samples to determine HAI titers against seasonal influenza A(H3N2), A(H1N1), and influenza B, although influenza B is unlikely to induce high-titer, subtype–cross-reactive antibodies to influenza A [36]. Thirty-nine children had detectable HAI antibodies against A/Victoria/361/2011(H3N2). Similar to findings for ADCC antibodies against A(H7N9), all but 1 child aged ≥8 years had detectable HAI antibodies against A(H3N2) (Supplementary Table 2 and Figure 4). HAI antibody titers against A(H3N2), however, did not correlate with age (ages 2–17 years, r = 0.046 and P = .75; ages 2–7 years, r = 0.21 and P = .19). Half of the children had detectable HAI antibodies against A/Brisbane/59/2007(H1N1). All but 1 child aged ≥8 years had detectable HAI antibodies against A(H1N1) (Supplementary Table 2 and Figure 4). HAI antibody titers against A(H1N1) increased with age (ages 2–17 years, r = 0.57 and P = .0000098; ages 2–7 years, r = 0.62 and P = .000015). The smaller number of children who had HAI antibodies against A/Brisbane/59/2007(H1N1), compared with the number who had HAI antibodies against A/Victoria/361/2011(H3N2), may be explained partly by the replacement of seasonal A(H1N1) strains with the A(H1N1)pdm09 strain in recent years. Thirty-two children had detectable HAI antibodies against B/Florida/4/2006. All children aged ≥8 years had detectable HAI antibodies against influenza B (Supplementary Table 2). HAI antibody titers against influenza B also increased with age (ages 2–17 years, r = 0.53 and P = .000062; ages 2–7 years, r = 0.43 and P = .0050; Supplementary Figure 1).

Figure 4.

Age distribution of hemagglutination inhibition (HAI) antibody titers to seasonal influenza A in US children. The top panel shows HAI antibody titers against A/Victoria/361/2011(H3N2). y = 0.010x + 1.6, r = 0.046, P = .75. The bottom panel shows HAI antibody titers against A/Brisbane/59/2007(H1N1). y = 0.081x + 0.37, r = 0.57, P = .0000098. Samples under the detection limit were assigned as a dilution of 1:2.5 (0.40 on the log10 scale). All samples were assayed in the same experiment against the same virus.

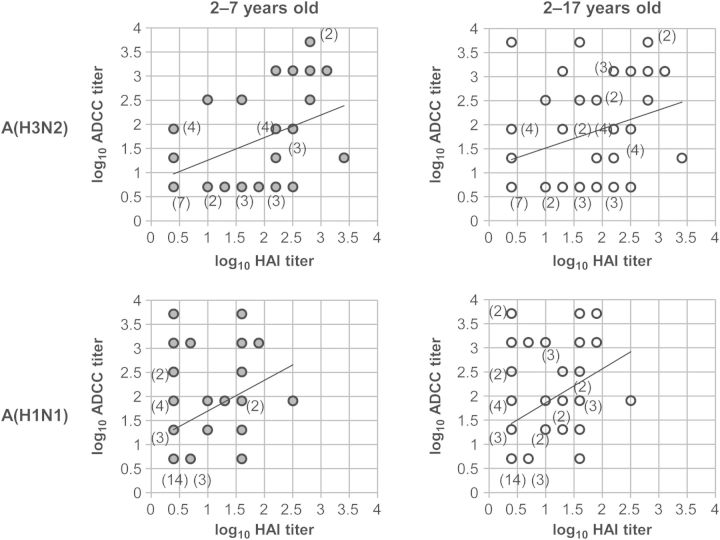

Titers of HAI antibodies against A(H3N2) and A(H1N1) correlated with titers of ADCC antibodies against A(H7N9) in the group aged 2–17 years (A(H3N2), r = 0.34 and P = .013; A(H1N1), r = 0.39 and P = .0039) and the group aged 2–7 years (A(H3N2), r = 0.47 and P = .0019; A(H1N1), r = 0.38 and P = .014; Figure 5). As expected, titers of HAI antibodies against influenza B did not correlate with titers of ADCC antibodies against A(H7N9) (Supplementary Figure 2). We performed a χ2 test to see whether there were correlations between detection of HAI antibodies against seasonal influenza viruses and the detection of ADCC antibodies against A(H7N9) (Table 1 and Supplementary Table 3). Detection of HAI antibodies against A(H1N1) correlated with detection of ADCC antibodies against A(H7N9) (ages 2–17 years, P = .0036; ages 2–7 years, P = .051; Figure 5). The correlation between detection of HAI antibodies against A(H3N2) and the detection of the ADCC antibodies against A(H7N9) did not reach statistical significance (ages 2–17 years, P = .092; ages 2–7 years, P = .23; Figure 5). As expected, there was no correlation between the detection of HAI antibodies against influenza B and detection of ADCC antibodies against A(H7N9).

Figure 5.

Correlation between hemagglutination inhibition (HAI) antibody titers against seasonal influenza A and antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) antibody titers against A(H7N9) in children aged 2–7 years and those aged 2–17 years. The top panels show correlation between titers of HAI antibodies against A/Victoria/361/2011(H3N2) and ADCC antibodies against A/Anhui/1/2013(H7N9) in children aged 2–7 years (y = 0.47x + 0.78, r = 0.47, P = .0019; left graph) and children aged 2–17 years (y = 0.39x + 1.1, r = 0.34, P = .013; right graph). The bottom panels show correlations between titer of HAI antibodies against A/Brisbane/59/2007(H1N1) and ADCC antibodies to A/Anhui/1/2013(H7N9) in children aged 2–7 years (y = 0.64x + 1.1, r = 0.38, P = .014; left graph) and children aged 2–17 years (y = 0.70x + 1.2, r = 0.39, P = .0039; right graph). Parentheses denote the number of subjects (≥2) with the same titer combination. Samples under the detection limit were assigned a dilution of 1:5 for ADCC antibody titers (0.70 on the log10 scale) and 1:2.5 for HAI antibody titers (0.40 on the log10 scale).

Table 1.

Correlation Between the Presence of Detectable Hemagglutination Inhibition (HAI) Antibodies Against Seasonal Influenza A Viruses and of Antibody-Dependent Cellular Cytotoxicity (ADCC) Antibodies Against A(H7N9) in Children Aged 2–7 Years and Those Aged 2–17 Years

| 2–7 y |

2–17 y old |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HAI A(H3N2) |

HAI A(H3N2) |

||||||||

| (+)a | (−)b | Overall | (+)a | (−)b | |||||

| ADCC | (+)c | 18 | 5 | 23 | ADCC | (+)c | 28 | 6 | 34 |

| A(H7N9) | (−)d | 11 | 7 | 18 | A(H7N9) | (−)d | 11 | 7 | 18 |

| 29 | 12 | 41 | 39 | 13 | 52 | ||||

| χ2 statistic = 1.4 | χ2 statistic = 2.8 | ||||||||

| P = .23 | P = .092 | ||||||||

| HAI A(H1N1) |

HAI A(H1N1) |

||||||||

| (+)a | (−)b | (+)a | (+)a | ||||||

| ADCC | (+)c | 12 | 11 | 23 | ADCC | (+)c | 22 | 12 | 34 |

| A(H7N9) | (−)d | 4 | 14 | 18 | A(H7N9) | (−)d | 4 | 14 | 18 |

| 16 | 25 | 41 | 26 | 26 | 52 | ||||

| χ2 statistic = 3.8 | χ2 statistic = 8.5 | ||||||||

| P = .051 | P = .0036 | ||||||||

a Antibodies were detected (≥1:5).

b Antibodies were under detection limit (<1:5).

c Antibodies were detected (≥1:20).

d Antibodies were under detection limit (<1:20).

Twenty-three children had HAI antibodies against both A(H3N2) and A(H1N1) (Table 2 and Supplementary Table 2). Among these children, 87% had ADCC antibodies against A(H7N9). In contrast, 53% of the children who had HAI antibodies against either A(H3N2) or A(H1N1) and 40% of those who had no HAI antibodies against influenza A had ADCC antibodies against A(H7N9) (Supplementary Table 2). When HAI antibody titers and the detection of the ADCC antibodies were compared, the higher the A(H3N2) or A(H1N1) HAI antibody titer a subject had, the greater the likelihood that the subject had A(H7N9) ADCC antibodies (Supplementary Table 4).

Table 2.

Correlation Between the Presence of Detectable Hemagglutination Inhibition (HAI) Antibodies Against Influenza A(H3N2) and A(H1N1) and of Antibody-Dependent Cellular Cytotoxicity (ADCC) Antibodies Against A(H7N9) in Children

| HAI A(H3N2) | (+)a | (+) | (−) | (−)b | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HAI A(H1N1) | (+)a | (−) | (+) | (−)b | ||

| ADCC | (+)c | 20 | 8 | 2 | 4 | 34 |

| A(H7N9) | (−)d | 3 | 8 | 1 | 6 | 18 |

| 23 | 16 | 3 | 10 | 52 | ||

| χ2 statistic = 9.3 | ||||||

| P = .026 | ||||||

a Antibodies were detected (≥1:5).

b Antibodies were under detection limit (<1:5).

c Antibodies were detected (≥1:20).

d Antibodies were under detection limit (<1:20).

DISCUSSION

Here, we report the presence of high titers of ADCC antibodies to the avian H7N9 subtype of influenza A virus in sera from healthy US adults and older children who are unlikely to have been exposed to avian influenza viruses, and the absence of these antibodies in sera from the majority of infants. Since the adult sera had similarly high titers of ADCC antibodies to avian A(H5N1), to which they are also unlikely to have been exposed, the observed subtype cross-reactivity is not a phenomenon unique to a peculiar virus strain but a more general characteristic of human ADCC antibody responses to avian influenza A viruses. All children aged ≥8 years also had ADCC antibodies to avian A(H7N9).

These results are in contrast with those from the study by Jegaskanda et al, who found that serum specimen from only 1 of 62 healthy adult Australians had ADCC antibodies to A(H7N9) [32]. The readouts of our ADCC assay and their ADCC assay are different. They quantitated activation of NK cells (interferon-γ or CD107a expression detected by fluorescence-activated cell sorting) in the presence of serum and purified recombinant H7 HA protein. ADCC antibodies detected by their assay are, therefore, specific to HA. We quantitated lysis of A(H7N9)-infected cells by NK cells in the presence of serum. ADCC antibodies measured in this assay can include antibodies to all influenza A proteins expressed on infected cell surface. Different results produced by these 2 assays suggest that antibodies binding to conserved epitopes on NA, NP, and M2 contribute to the ADCC activity against A(H7N9)-infected cells detected by our ADCC assay. In addition, the different results could be related to the location of the subjects whose sera were analyzed.

Although 2 ADCC antibody epitopes have been identified on the globular head of the H1 HA [13], they are not subtype cross-reactive and are unlikely to be involved in subtype–cross-reactive ADCC antibody responses to A(H7N9) or A(H5N1). Jegaskanda et al detected anti-NA (N1) ADCC antibodies in some of the intravenous immunoglobulin preparations tested [32]. Subtype–cross-reactive antigenic sites have been identified on NA [37]. Anti-NP ADCC antibodies were detected in macaques either infected with A(H1N1)pdm09 or vaccinated with trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine [38]. It is important to determine whether anti-NP antibodies are also involved in subtype–cross-reactive ADCC antibody response in humans. Although levels of anti-M2 antibodies were found to be low to nonexistent in humans [39, 40], a recent study that used transfected cell lines expressing M2 on their surface reported that anti-M2 antibodies were detected in a higher percentage of individuals than previously thought, especially in adults aged ≥40 years (38%–50%) [41].

We measured HAI antibodies to seasonal influenza A(H3N2), A(H1N1), and influenza B to determine whether influenza virus exposure induced subtype–cross-reactive ADCC antibodies to A(H7N9), and we found some correlations between HAI antibody responses to seasonal influenza A, but not influenza B, and ADCC antibodies to A(H7N9). Four children had HAI antibodies to seasonal influenza A that were under the detection limit but ADCC antibodies to A(H7N9). It is possible that this ADCC assay is more sensitive than the HAI assay, which is supported by the relatively higher titers of ADCC antibodies than HAI antibodies to influenza A in human sera [9, 20]. Alternatively, their HAI titers may have waned to below the detectable limit.

Concerning the contribution of ADCC and other nonneutralizing antibodies to protection, a reanalysis of the archival records from the Cleveland Family Study suggested the presence of heterosubtypic immunity in adults, not in children. That study was conducted before and during the 1957 A(H2N2) pandemic and found that A(H1N1) infection in previous years had a protective effect against A(H2N2) infection in 1957 only in adults [42]. Both antibodies and T cells may also be involved in this heterosubtypic immunity. Recently, we observed in Thai children in a 2010–2011 study that titers of ADCC antibodies against A(H1N1)pdm09 increased with age, while titers of CDL and HAI antibodies did not [25]. This age distribution of ADCC antibodies parallels that of heterosubtypic immunity. Of note, in the Thai study we measured ADCC antibodies against circulating A(H1N1)pdm09, not subtype–cross-reactive ADCC antibodies.

We also observed moderate titers of subtype–cross-reactive CDL antibodies against A(H7N9) and A(H5N1) in sera from 38%–44% of adults. But, contrary to ADCC antibody titers, there was no correlation between titers of CDL antibodies against A(H7N9) and those against A(H5N1), suggesting that a different set of antibodies may be involved in the subtype–cross-reactive ADCC and CDL antibody responses.

There is always a question of whether antiviral immune responses other than virus neutralization, such as the ADCC and CDL antibodies, may be immunopathological. A study in mice suggests that NK cells may contribute to pathology [43]. Another study reported that, with a lower infectious dose, this was not seen [44], suggesting a fine balance between protection and immunopathology. Recently, DiLillo et al demonstrated that Fc-Fc receptor γ interactions are required for stalk-specific, but not globular head-specific, monoclonal antibody–mediated protection against influenza virus challenge in mice at lower antibody concentrations but are not needed at higher concentrations [14]. Another earlier report, however, demonstrated that NK cells were not necessary for antibody-mediated influenza virus clearance [45]. As for roles of complement, although A(H5N1) infection of mice suggested that increased complement activation was associated with enhanced disease, studies using knockout mice demonstrated that C3 was required for protection [46]. We should point out that results from mouse models of influenza virus infection should be interpreted cautiously because the immunological history of humans is very different from that of laboratory mice.

Recently, some perspectives have been offered concerning the relative contributions of the immune system to pathology and protection. La Gruta et al concluded that the same immunological factors mediating tissue damage during the anti–influenza virus immune response are also critical for efficient elimination of influenza virus [47]. More generally, a new framework was proposed to understand microbial pathogenesis. It has been suggested that both too weak and too strong host responses to microorganisms lead to host damage [48]. The contribution of ADCC and CDL antibodies to protection and/or to immunopathology may also be relative and context dependent and deserves to be investigated in prospective controlled clinical studies.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at The Journal of Infectious Diseases online (http://jid.oxfordjournals.org). Supplementary materials consist of data provided by the author that are published to benefit the reader. The posted materials are not copyedited. The contents of all supplementary data are the sole responsibility of the authors. Questions or messages regarding errors should be addressed to the author.

Notes

Acknowledgments. We thank Dr Daniel Libraty, for his input on the interpretation of the antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity and complement-dependent lysis data; and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Biodefense and Emerging Infections Research Resources, for influenza viruses used in this study.

Financial support. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (contracts HHSN272201400005C and HHSN272201200005C).

Potential conflicts of interest. The authors received research funding from GlaxoSmithKline for an influenza virus vaccine study, which is not related to the study described in this article.

All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1.Hayden FG, Palese P. Influenza virus. In: Richman DD, Whitley RJ, Hayden FG, eds. Clinical virology. 2nd ed Washington, DC: ASM Press, 2002:891–920. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Palese P, Shaw ML. Orthomyxoviridae: the viruses and their replication. In: Knipe DM, Howley PM, eds. Fields virology. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, 2007:1648–89. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wu Y, Wu Y, Tefsen B, Shi Y, Gao GF. Bat-derived influenza-like viruses H17N10 and H18N11. Trends Microbiol 2014; 22:183–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Atmar RL. Influenza viruses. In: Murray PR, Baron EJ, Jorgensen JH, Landry ML, Pfaller MA, eds. Manual of clinical microbiology. 9th ed Vol. 2 Washington, DC: ASM Press, 2007:1340–51. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Knossow M, Skehel JJ. Variation and infectivity neutralization in influenza. Immunology 2006; 119:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Okuno Y, Isegawa Y, Sasao F, Ueda S. A common neutralizing epitope conserved between the hemagglutinins of influenza A virus H1 and H2 strains. J Virol 1993; 67:2552–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Han T, Marasco WA. Structural basis of influenza virus neutralization. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2011; 1217:178–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Laursen NS, Wilson IA. Broadly neutralizing antibodies against influenza viruses. Antiviral Res 2013; 98:476–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hashimoto G, Wright PF, Karzon DT. Antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity against influenza virus-infected cells. J Infect Dis 1983; 148:785–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yewdell JW, Frank E, Gerhard W. Expression of influenza A virus internal antigens on the surface of infected P815 cells. J Immunol 1981; 126:1814–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lamb RA, Zebedee SL, Richardson CD. Influenza virus M2 protein is an integral membrane protein expressed on the infected-cell surface. Cell 1985; 40:627–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hughey PG, Compans RW, Zebedee SL, Lamb RA. Expression of the influenza A virus M2 protein is restricted to apical surfaces of polarized epithelial cells. J Virol 1992; 66:5542–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Srivastava V, Yang Z, Hung IF, Xu J, Zheng B, Zhang MY. Identification of dominant antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity epitopes on the hemagglutinin antigen of pandemic H1N1 influenza virus. J Virol 2013; 87:5831–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.DiLillo DJ, Tan GS, Palese P, Ravetch JV. Broadly neutralizing hemagglutinin stalk-specific antibodies require FcgammaR interactions for protection against influenza virus in vivo. Nat Med 2014; 20:143–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Terajima M, Cruz J, Co MD, et al. Complement-dependent lysis of influenza a virus-infected cells by broadly cross-reactive human monoclonal antibodies. J Virol 2011; 85:13463–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grandea AG, III, Olsen OA, Cox TC, et al. Human antibodies reveal a protective epitope that is highly conserved among human and nonhuman influenza A viruses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010; 107:12658–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bodewes R, Geelhoed-Mieras MM, Wrammert J, et al. In vitro assessment of the immunological significance of a human monoclonal antibody directed to the influenza a virus nucleoprotein. Clin Vaccine Immunol 2013; 20:1333–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carragher DM, Kaminski DA, Moquin A, Hartson L, Randall TD. A novel role for non-neutralizing antibodies against nucleoprotein in facilitating resistance to influenza virus. J Immunol 2008; 181:4168–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.LaMere MW, Lam HT, Moquin A, et al. Contributions of antinucleoprotein IgG to heterosubtypic immunity against influenza virus. J Immunol 2011; 186:4331–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vella S, Rocchi G, Resta S, Marcelli M, De Felici A. Antibody reactive in antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity following influenza virus vaccination. J Med Virol 1980; 6:203–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Co MD, Cruz J, Takeda A, Ennis FA, Terajima M. Comparison of complement dependent lytic, hemagglutination inhibition and microneutralization antibody responses in influenza vaccinated individuals. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2012; 8:1218–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Quinnan GV, Ennis FA, Tuazon CU, et al. Cytotoxic lymphocytes and antibody-dependent complement-mediated cytotoxicity induced by administration of influenza vaccine. Infect Immun 1980; 30:362–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jegaskanda S, Job ER, Kramski M, et al. Cross-reactive influenza-specific antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity antibodies in the absence of neutralizing antibodies. J Immunol 2013; 190:1837–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jegaskanda S, Reading PC, Kent SJ. Influenza-specific antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity: toward a universal influenza vaccine. J Immunol 2014; 193:469–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Co MD, Terajima M, Thomas SJ, et al. Relationship of preexisting influenza hemagglutination inhibition, complement-dependent lytic, and antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity antibodies to the development of clinical illness in a prospective study of A(H1N1)pdm09 influenza in children. Viral Immunol 2014; 27:375–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schmaljohn AL. Protective antiviral antibodies that lack neutralizing activity: precedents and evolution of concepts. Curr HIV Res 2013; 11:345–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Excler JL, Ake J, Robb ML, Kim JH, Plotkin SA. Nonneutralizing functional antibodies: a new “old” paradigm for HIV vaccines. Clin Vaccine Immunol 2014; 21:1023–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kilbourne ED. Influenza immunity: new insights from old studies. J Infect Dis 2006; 193:7–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang TT, Parides MK, Palese P. Seroevidence for H5N1 influenza infections in humans: meta-analysis. Science 2012; 335:1463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bai T, Zhou J, Shu Y. Serologic study for influenza A (H7N9) among high-risk groups in China. N Engl J Med 2013; 368:2339–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang S, Chen Y, Cui D, et al. Avian-origin influenza A(H7N9) infection in influenza A(H7N9)-affected areas of China: a serological study. J Infect Dis 2014; 209:265–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jegaskanda S, Vandenberg K, Laurie KL, et al. Cross-reactive influenza-specific antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity in intravenous immunoglobulin as a potential therapeutic against emerging influenza viruses. J Infect Dis 2014; 210:1811–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Szretter KJ, Balish AL, Katz JM. Influenza: propagation, quantification, and storage. In: Coico R, Kowalik T, Quarles JM, Stevenson B, Taylor RK, eds. Current protocols in microbiology. Supplement 3 New York: John Wiley and Sons, 2006:15G.1.1-G.1.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Canetta SE, Bao Y, Co MD, et al. Serological documentation of maternal influenza exposure and bipolar disorder in adult offspring. Am J Psychiatry 2014; 171:557–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Preacher KJ. Calculation for the chi-square test: An interactive calculation tool for chi-square tests of goodness of fit and independence [software]. http://quantpsy.org. Accessed 29 December 2014.

- 36.Terajima M, Babon JA, Co MD, Ennis FA. Cross-reactive human B cell and T cell epitopes between influenza A and B viruses. Virol J 2013; 10:244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gravel C, Li C, Wang J, et al. Qualitative and quantitative analyses of virtually all subtypes of influenza A and B viral neuraminidases using antibodies targeting the universally conserved sequences. Vaccine 2010; 28:5774–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jegaskanda S, Amarasena TH, Laurie KL, et al. Standard trivalent influenza virus protein vaccination does not prime antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity in macaques. J Virol 2013; 87:13706–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Feng J, Zhang M, Mozdzanowska K, et al. Influenza A virus infection engenders a poor antibody response against the ectodomain of matrix protein 2. Virol J 2006; 3:102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schotsaert M, De Filette M, Fiers W, Saelens X. Universal M2 ectodomain-based influenza A vaccines: preclinical and clinical developments. Expert Rev Vaccines 2009; 8:499–508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhong W, Reed C, Blair PJ, Katz JM, Hancock K. Serum antibody response to matrix protein 2 following natural infection with 2009 pandemic influenza A(H1N1) virus in humans. J Infect Dis 2014; 209:986–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Epstein SL. Prior H1N1 influenza infection and susceptibility of Cleveland Family Study participants during the H2N2 pandemic of 1957: an experiment of nature. J Infect Dis 2006; 193:49–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Abdul-Careem MF, Mian MF, Yue G, et al. Critical role of natural killer cells in lung immunopathology during influenza infection in mice. J Infect Dis 2012; 206:167–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhou G, Juang SW, Kane KP. NK cells exacerbate the pathology of influenza virus infection in mice. Eur J Immunol 2013; 43:929–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Huber VC, Lynch JM, Bucher DJ, Le J, Metzger DW. Fc receptor-mediated phagocytosis makes a significant contribution to clearance of influenza virus infections. J Immunol 2001; 166:7381–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.O'Brien KB, Morrison TE, Dundore DY, Heise MT, Schultz-Cherry S. A protective role for complement C3 protein during pandemic 2009 H1N1 and H5N1 influenza A virus infection. PLoS One 2011; 6:e17377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.La Gruta NL, Kedzierska K, Stambas J, Doherty PC. A question of self-preservation: immunopathology in influenza virus infection. Immunol Cell Biol 2007; 85:85–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Casadevall A, Pirofski LA. The damage-response framework of microbial pathogenesis. Nat Rev Microbiol 2003; 1:17–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.