Abstract

Objectives

Doctors who graduated in the UK after 2005 have followed a restructured postgraduate training programme (Modernising Medical Careers) and have experienced the introduction of the European Working Time Regulation and e-portfolios. In this paper, we report the views of doctors who graduated in 2008 three years after graduation and compare these views with those expressed in year 1.

Design

Questionnaires about career intentions, destinations and views sent in 2011 to all medical graduates of 2008.

Participants

3228 UK medical graduates.

Main outcome measures

Comments on work, education and training.

Results

Response was 49% (3228/6538); 885 doctors wrote comments. Of these, 21.8% were unhappy with the standard of their training; 8.4% were positive. Doctors made positive comments about levels of supervision, support, morale and job satisfaction. Many doctors commented on poor arrangements for rotas, cover and leave, which had an adverse effect on work-life balance, relationships, morale and health. Some doctors felt pressured into choosing their future specialty too early, with inadequate career advice. Themes raised in year 3 that were seldom raised in year 1 included arrangements for flexible working and maternity leave, obtaining posts in desired locations and having to pay for courses, exams and conferences.

Conclusions

Many doctors felt training was available, but that European Working Time Regulation, rotas and cover arrangements made it difficult to attend. Three years after graduation, doctors raised similar concerns to those they had raised two years earlier, but the pressures of career decision making, family life and job seeking were new issues.

Keywords: Physicians, career choice, workforce, medical education, junior doctors, attitude of health personnel

Introduction

The working conditions, training and specialty application procedure for doctors who graduated from the UK medical schools after 2005 are very different to those experienced by earlier cohorts.1 The European Working Time Regulation (EWTR) was applied progressively to junior doctors working in National Health Service (NHS) trusts between 2004 and 2009: junior doctors should not now work more than 48 h a week on average. As of 2005, UK doctors had to choose and apply for their area of specialism during their second postgraduate year (known in the UK as the F2 year). Prior to 2005, doctors could take several years after graduation to decide upon their specialty. The Modernising Medical Careers (MMC) programme brought about changes to specialty training which took effect nationally in 2007.2,3 E-portfolios were introduced in 2005 allowing doctors to record their professional development electronically. There are new types of medical staff such as Advanced Nurse Practitioners (ANPs), surgical practitioners and physician assistants. Such practitioners can reduce the repetitive tasks junior doctors undertake, but this should not reduce the quality of doctors’ training.4 Financial pressures on the NHS may affect junior doctors’ training (e.g. by compromising supervision and teaching time, and reducing funding for conferences and courses) and may make it harder to maintain adequate staffing levels, accommodation and staffroom facilities.

Foundation year one (F1) doctors who graduated from UK medical schools in 2008 and 2009 expressed concerns about the balance between service provision, administration, training and education.5 We surveyed the 2008 graduates again, three years after graduation, with the aim of investigating their career progression and their views of their training. Here we report on their free text comments to an open-ended question which invited comments on their training and work and we particularly emphasise comments which are substantially different to those made one year after graduation.

Methods

Questionnaires were sent to UK medical graduates of 2008 three years after qualification. The survey was multi-purpose and concerned with career choices and career progression. Up to five reminders were sent to non-respondents. Replies were received until February 2012. Further details of the methodology are available elsewhere.6,7 Doctors were invited to provide free text comments in response to the question: ‘Please give us any comments you wish to make, on any aspect of your training or work.’

We developed a coding scheme based upon the main themes and subthemes contained within the comments. Two researchers devised the coding scheme, independently coded the answers and resolved coding differences through discussion. Seven main themes were identified (including an ‘Other’ theme), and 33 subthemes (Appendix 1, Figure 1). Each doctor’s comments were assigned up to four subthemes. Each subtheme was additionally coded as ‘positive’, ‘neutral/mixed’ or ‘negative’. We present quotes which, in our judgement, best illustrate each subtheme. Occasionally, we present a quote which raised an interesting point but which was not raised frequently. Doctors’ identities have been protected by redaction. Doctors’ grades and specialties are shown next to each quote, where known.

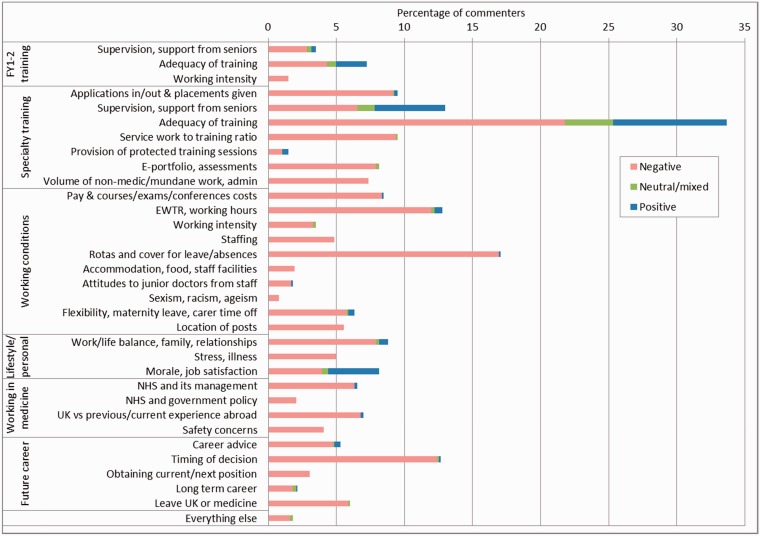

Figure 1.

Percentages of respondents who commented negatively, neutrally or positively on each issue: UK medical graduates of 2008 commenting in 2011–2012 (includes all comments, whether negative, neutral or positive).

The data were analysed by univariate crosstabulation. To test statistical significance, we used χ2 statistics (reporting Yates’s continuity correction where appropriate).

Results

Response

Questionnaires were sent to all 6795 contactable doctors who qualified in 2008 in the UK. The response was 49.4% (3228/6538), excluding from the denominator 211 who were untraceable, 44 who declined to participate and 2 who had died. For men the response rate was 46.0% (1182/2567), and for women 51.5% (2046/3970). Some respondents (78/3228) completed a shorter questionnaire which did not ask for written comments; 3150 respondents completed the full questionnaire. Comments were provided by 28.1% (885/3150) of these respondents (13% of the cohort).

Comparison of responses from commenters and non-commenters

Respondents who commented were compared with those who did not (Table 1), identifying four groups: those who did not comment, commented only negatively, commented only positively and commented both negatively and positively. The mean scores in the four groups on two questions about job satisfaction and satisfaction with leisure time were compared.

Table 1.

Comparison of responses for commenters and non-commenters, UK medical graduates of 2008 three years after graduation.

| Nature of comments |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Respondent, but no comments (N = 2265) |

Only neutral, or positive and negative (N = 177) | Only negative comments (N = 668) | Only positive comments (N = 40) | |

| Mean | Mean | Mean | Mean | |

| How much are you enjoying your current position? | 7.2 | 7.2 | 6.7 | 7.8 |

| How satisfied are you with the amount of time your work currently leaves you for family, social and recreational activities? | 6.2 | 6.1 | 5.6 | 6.9 |

Responses to the questions were on a scale from 1 (not at all satisfied/not at all enjoying it) to 10 (extremely satisfied/enjoying it greatly). Results shown are mean scores.

Respondents were asked ‘How much are you enjoying your current position?’ with answers on a scale from 1 to 10. Significant differences were observed between the four groups (F = 13.3, p < 0.001). Those who only provided positive comments had a mean score of 7.8, compared with 7.2 for those who provided no comments and for those whose comments were both negative and positive, and 6.7 for those who only provided negative comments. Respondents were also asked ‘How satisfied are you with the amount of time your work currently leaves you for family, social and recreational activities?’ (using the same scale as before). Significant differences were observed between the four groups (Table 1; F = 10.9, p < 0.001), following a similar pattern.

Frequency of themes

The comments of the 885 commenting doctors were coded against the coding scheme (see Methods section) and 2039 matches were identified (Figure 1, Appendix 1). The comments were classified under six main themes: ‘specialty training’ (516 doctors commented on this subtheme), ‘working conditions’ (516), ‘future career’ (227), ‘lifestyle and personal issues’ (181), ‘working in medicine’ (163) and ‘Foundation Years training’ (93). Overall, 86.1% of comments were coded as negative, 3.6% were neutral or mixed and 10.3% were positive.

Areas which received the most negative comments were as follows: ‘adequacy of specialty training’ (21.8% of commenters commented negatively; Figure 1, Appendix 1), ‘rotas and cover for leave or absences’ (16.9%), ‘timing of decision about future career’ (12.4%) and ‘EWTR and working hours’ (12.0%). Areas which received the most positive comments were: ‘adequacy of specialty training’ (8.4% commented positively), ‘supervision and support from seniors during specialty training’ (5.2%) and ‘morale and job satisfaction’ (3.7%).

Negative comments raised more by men than women included ‘e-portfolio, assessments’ (12.1% of men, 5.6% of women; χ21 = 11.0, p < 0.001), ‘adequacy of specialty training’ (28.1% of men, 18.4% of women; χ21 = 10.7, p < 0.001), ‘service work to training ratio’ (12.7% of men, 7.5% of women; χ21 = 6.0, p < 0.05) and ‘Pay & courses/exams/conferences costs’ (11.1% of men, 6.8% of women; χ21 = 4.5, p < 0.05; Appendix 2). Negative comments raised more by women than men included ‘work/life balance, family, relationships’ (10.5% of women, 3.2% of men; χ21 = 13.8, p < 0.001), ‘flexibility, maternity leave, carer time off’ (7.7% of women, 2.2% of men; χ21 = 10.1, p < 0.001) and ‘rotas and cover for leave/absences’ (19.4% of women, 12.4% of men; χ21 = 6.4, p < 0.05). Positive comments were also examined and no significant differences by gender were found.

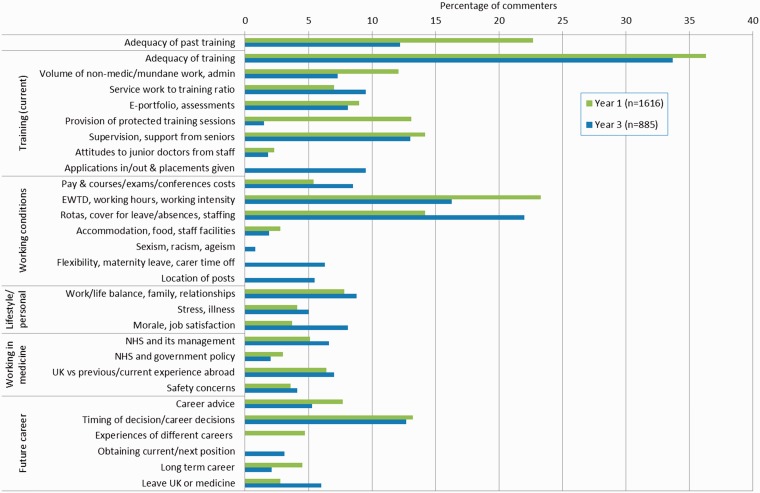

Figure 2 compares the frequency of topics raised by doctors in year 3 and year 1. While in both years, adequacy of training was the most frequently mentioned topic, and there were other similarities between the two years (Figure 2); in year 3, a number of new subthemes emerged which are also discussed below.

Figure 2.

Comparison between percentages of comments on each issue made one and three years after graduation: 2008–2009 graduates in year 1, 2008 graduates in year 3 (includes all comments, whether negative, neutral or positive).

Table 2 shows, verbatim, comments which have been selected to illustrate each of the points made in the following paragraphs of results. In the table the first column indicates the topic to which the comment refers. The comments appear in Table 2 in the same sequence as the points are made in the following text.

Table 2.

Typical comments illustrating points made by 2008 graduates about their year 3 training.

| Topic | Quotation | Respondent details |

|---|---|---|

| Quality of teaching | ‘scanty and of poor quality’ | male senior house officer, anaesthetics |

| Treatment compared to F1 doctors | ‘I am currently meant to be a Core Surgical Trainee … no distinction between my grade & FY1/FY2, we are all on same rota with same responsibilities, yet this is still counted as training for surgery!’ | female year 1 core trainee, ophthalmology |

| Treatment compared to F1 doctors | ‘I feel to a large degree that I am repeating foundation training all over again, yet I am still expected to achieve the competencies of an ST by covering all the more senior jobs – difficult when I am busy taking blood or clerking a patient, it's too late for me to assist with the forceps deliveries or go to theatre with the seniors’ | female year 1 specialist trainee, obstetrics and gynaecology |

| Teaching time interruptions | ‘regularly called away from protected teaching time due to department being busy’ | female year 2 core trainee, anaesthetics |

| Exposure/responsibility | ‘I feel that as junior doctors we have little opportunity to try new things, i.e. research/teaching – training is extremely pressurised with a fast track attitude and no opportunities to broaden our medical experience and knowledge’. | female year 1 specialist trainee, rheumatology/rehabilitation |

| Exposure/responsibility | [complained that there was very little bedside teaching and added that his current post was] ‘excessively consultant driven, more responsibility needs to be given back to juniors or the consultants of tomorrow will be indecisive, inexperienced and under-trained’. | male year 2 trainee, general medicine |

| Inadequate training time | ‘I do not need to work more hours to get better training – I need some training during the hours I already do!’. | female year 1 specialist trainee, emergency medicine |

| Inadequate opportunities to practise | ‘training opportunities such as suturing at the end of an operation are not available to trainee surgeons. The surgical practitioners I have come across are often highly possessive of their role, and unwelcoming if you try to get involved in theatre’. | female year 2 core trainee, chest medicine |

| Inadequate time to consider job offers | [either had to accept the first offer she got in order to guarantee the specialty she wanted] ‘or reject that offer and take a chance on getting the same job at a different deanery that would have been slightly more preferable in terms of location, but as a result potentially end up with no job at all’. | female year 1 core trainee, anaesthetics |

| Inadequate training posts | [felt that his deanery] ‘filled service jobs first rather than the positions with the best training’. | male year 1 core trainee, anaesthetics |

| Short rotations | ‘although well supported by seniors it is difficult to build a close bond with them, due to the frequency of rotation change’. | female doctor, unemployed |

| LTFT training availability | ‘I would like to have the option to train less than full time, without having to have children to do so’. | female year 1 specialist trainee, pathology |

| LTFT training availability | ‘valid reasons … are either for family reasons, or physical health reasons. As a single male with no children who wishes to develop lifelong serious interest in music along with my medical career, I almost feel embarrassed to admit this to seniors/supervisors when discussing career plans’. | male trainee, intensive care/anaesthesia |

| Compatibility of family and hospital medicine | ‘as a woman who would like to have a family it is difficult to see how I would do this with a career in hospital medicine and I think many promising hospital doctors end up training as General Practitioners’. | female year 2 core trainee, anaesthetics |

| Stigma of training LTFT | ‘I work 30 hours a week, have a great home life and plenty of time to study for exams and attend courses I am interested in … the downside is that I could do this for three years and then have difficulty in getting professional recognition despite doing the same job as (other) trainees’. | male hospital clinical fellow, emergency medicine |

| Maternity leave problems | ‘I was … refused maternity pay (to which I was entitled) and had to seek advice from the BMA. This led to a Trust hearing and eventually the decision was overturned … I am considering other career options. | female year 1 trainee, General Practice |

| Maternity leave problems | ‘I went on maternity leave not knowing what I would be paid and worrying about whether I would be able to pay the mortgage. On starting back I arranged everything myself. I am still waiting to hear if I will pass F2 … despite calling and e-mailing repeatedly only found out in the last 2 weeks where I am allocated for my first placement and we have bought a house 1 hour away’. | female trainee, General Practice |

| Mobility issues | ‘Having to move house every year (or alternatively commute great distance and live in same place) impacts stress for moving, but also credit rating for when wanting to buy a house… it impacts on decisions of where to live and whether to rent or buy and for some, whether to start long term relationship or not’. | female foundation year 2 trainee |

| Mobility issues | ‘My training deanery is too large. It's difficult to imagine where I will choose to live as there is nowhere that would be convenient for the whole stretch of (it). Deanery is unclear about how much choice you get in your applications for regions. Too many re-applications for what is supposed to be run-through’. | female year 1 specialist trainee, paediatrics |

| Mobility issues | [wrote that she could potentially be sent anywhere in Britain – as could her partner who is at the same stage] ‘it makes it almost impossible to plan a life together and settle down/start a family unless one person leaves medicine or starts again in a less competitive specialty. This is obviously a massive cause of stress and concern for both of us and from speaking to colleagues is a common problem across surgical training and I am sure other specialities as well’. | female year 1 core trainee, tropical medicine |

| Availability of training posts | ‘I am currently applying for ST3 posts. It is a great concern as there appears to be a bottleneck and very few training posts available’. | female, year 2 specialist trainee, neurosurgery |

| Pay | ‘The pay that GPs receive in the UK is absurd for practitioners who are less highly trained and generally less busy than their hospital counterparts. This will weaken the NHS as better candidates are put off their preferred speciality to pursue a better lifestyle with superior financial reward’. | male year 1 specialist trainee, radiology |

| Control over work | Another: ‘I am sad to be leaving paediatrics. The main reason I'm (switching) is to do with control – I have next to no control over what I do and when I do it at present’. | male ST1 trainee, paediatrics [about to switch to GP training, despite enjoying paediatric work] |

| Control over work | ‘I am currently training in Radiology. I entered after F2 – I feel I made this decision very early on in my medical career … and am considering applying to general practice. I am not sure this is what I want to do long term & my current job satisfaction is linked principality (sic) to the low-level responsibility of being a junior radiologist (no on-calls currently & minimal independent reporting)’. | female year 1 specialist trainee, radiology |

| Courses | ‘Very little funding for courses – feels as though you buy your CV … Unsustainable on current wage’. | female year 1 core trainee, nephrology |

| Courses | [felt that there was a shortage of consultants keen to deliver teaching and added that] ‘as a result, in an effort to pass exams, junior doctors are having to pay £600+ for courses designed to help pass clinical exams’. | female trainee, General Practice |

‘Run-through’ denotes specialty training in a specific specialty starting in year 3 and continuing to certification. LTFT: less-than-full-time; ST: Specialist Trainee training grade; F1, F2: Foundation trainee years 1 and 2 (the first two years post-graduation); BMA: British Medical Association.

Adequacy of specialty training

Doctors described a lack of consultants willing to teach, or said that consultants were unable to teach due to time constraints or a lack of teaching rooms. The quality of teaching on ward rounds was criticised by some. Some doctors felt that they were not being treated differently from foundation year doctors and that they were often called away from protected teaching time due to service demands.

Several doctors believed that their training was not broad enough or that they were not being given enough exposure or responsibility. These doctors were concerned that they would reach consultant stage with poor experience of their specialty. Some felt that their limited opportunities were exacerbated by EWTR, but others felt that extra hours were not the answer. Some doctors felt that their experience of procedures was limited by the introduction of certain staff roles (e.g. surgical practitioner, or advanced nurse practitioner).

Applications in/out and placements given

The application process for Specialty Training (ST1) and Core Training year 1 (CT1) posts was perceived to be inflexible by some doctors. Doctors also experienced administrative errors, and many complained about being given too little time to accept or decline offers while waiting to attend interviews elsewhere.

Some doctors were given placements/rotations they didn’t want, and which were not, they felt, going to give them the experience they needed for their next post. The length of each rotation was also viewed as being too short to form strong relationships with seniors.

Less-than-full-time training, families and maternity leave

While flexibility and the ability to work less-than-full-time (LTFT) were important to doctors who wanted to have (or had) children, or had health issues, other doctors felt that eligibility to LTFT training should also include them.

Some doctors felt constrained by the level of structure within their training programme and could not see how they could work flexibly in hospital medicine.

Some had taken the decision to work fewer hours than their colleagues so that they could enjoy a better work-life balance but they worried about the stigma attached to such decisions.

Maternity leave was not easy to negotiate for some doctors. Other women doctors found it difficult to arrange maternity leave and to arrange their return placement.

Location of posts

By their third year after qualification, some doctors were tired of having to move home to be nearer to a post, or having to travel long distances to work (or stay in doctors’ accommodation). This problem was amplified for those doctors who worked in large deaneries. Those in dual-doctor relationships found it difficult to get posts in the same area.

Obtaining the current or next position

There was concern about the lack of Specialty Training year 3 (ST3) training posts, which appeared to be a bottleneck in the system at the time of the survey.

When thinking about their long-term careers, many doctors made comparisons between hospital work and GP work and found GP work to be very attractive, particularly when they considered their anticipated pay, workload and control over their work.

Doctors who had felt under pressure to decide upon their specialty too early, reflected upon whether or not they had made the right decision.

Courses, exams and conferences costs

Several doctors had found it hard to obtain funding for courses or conferences, and some felt that they had to pay for courses in order to pass (often self-financed) exams. Courses were expensive but doctors took recourse to them to supplement inadequate training.

Discussion

Main findings

Over a fifth of commenting doctors reported they had received, in their view, inadequate training in their first year of specialty training, three years after graduation. This is similar to the percentage who reported that their foundation year 1 training two years previously had not been of a high standard. Some doctors reported that they had not received enough exposure or responsibility. Perceived reasons for this included a lack of consultants willing or able to teach, the impact of the EWTR and being given the same, lower level, responsibilities as foundation doctors one or two years their junior. Just under a fifth of commenters were frustrated by arrangements for rotas, cover and leave. Doctors were given rotas too late, and arranging suitable leave or cover was difficult.

These doctors raised several new themes compared with those they raised one year after graduation. The new themes covered career issues (the location of posts, obtaining the current or next position, the process of making applications and getting placements, and paying for courses, exams and conferences) and family life issues (flexibility, maternity leave, time off for those with caring responsibilities).

The application process for specialty training was viewed negatively by some doctors. Doctors were given inadequate time to decide on an offer and were offered rotations in specialties and locations that they did not want. The impact was felt especially by those in dual-doctor relationships where co-location was important.

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

The study was large scale and national, and over a quarter of respondents provided comments. However, non-response bias may have been present: those who provided comments and those who replied to the questionnaire but did not provide comments may have been different to non-responders. Among respondents, we found that non-commenting doctors were similar to doctors who provided neutral or mixed comments and were dissimilar to doctors who provided exclusively positive or exclusively negative comments. It is possible that open-ended questions garner mostly negative comments;8 in our study, 86% of comments were negative.

We present the content analysis both quantitatively and in narrative style. A purely numeric approach can be criticised because we do not know how representative the sample is of the general population, and because a topic raised by one doctor may have been important to other doctors who, for whatever reason, did not mention that topic.9

Comparison with existing literature

The General Medical Council (GMC) National Training Survey (NTS) of 2011 found that 68% of UK trainee doctors felt that the quality of teaching was good or excellent.10 Over a fifth of our commenters were not satisfied with their specialty training. The samples surveyed are not directly similar: the GMC sample covered doctors at all stages in training and included overseas graduates, but our sample is confined to UK graduates three years after graduation. However, the results are broadly similar.

The concerns our survey reports about the impact of EWTR were reflected in other studies. In one study, 61% of registrars said that training had worsened since its implementation,11 another found that EWTR requirements created difficulties filling service rotas, which in turn resulted in fewer training opportunities.4 A more recent study also reported understaffed rotas and more educational activity having to take place in the doctor’s own time.12

Our commenters questioned the validity and usefulness of e-portfolios. Other researchers found large variation in the level of engagement with e-portfolios;13 in another study, only 5% of Core Medical trainees thought that e-portfolios were good value for money;14 surgical trainees reported dissatisfaction with the workplace based assessment component of their online portfolio15 and F2 doctors in Northern Ireland reported infrequent consultant input into their workplace based assessments.16

More positively, the 2011 NTS found that 42% of registrars reported that their work-life balance had improved as a result of the EWTR.11 However, many doctors in our sample, especially women doctors or doctors in dual-doctor relationships, found it difficult to maintain a good work-life balance. Other research has found that dual-doctor relationships experience particular challenges17 and that women doctors’ career progression slows when they have children but men’s does not.18 Women in our sample were more likely than men to comment negatively on work-life balance and flexibility. Gender differences in career orientation, responsibility for family life and desire to pursue flexible training have been found in other studies.19–21

Conclusions

These doctors were commenting in late 2011 and early 2012. Since then, initiatives to address some of the concerns expressed may be producing improvements. For example, the introduction in 2014 of the new online Oriel system for NHS specialist training applications (see www.oriel.nhs.uk) should ease the process of finding and applying for suitable training posts. However, recent studies continue to report that problems remain with restriction of training opportunities due to high service demand and organisational issues. Challenges to work-life balance and the balancing of training provision, personal needs and the demands of the health service, described here by these doctors, are issues which remain worthy of consideration as we move into 2015 and a decade is marked since the introduction of EWTR and MMC.

Declarations

Competing interests

None declared

Funding

This is an independent report commissioned and funded by the Policy Research Programme in the Department of Health (project number 016/0118). Michael Goldacre is partly funded by Public Health England. The views expressed are not necessarily those of the funding bodies.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the National Research Ethics Service, following referral to the Brighton and Mid-Sussex Research Ethics Committee in its role as a multi-centre research ethics committee (ref 04/Q1907/48).

Guarantor

All authors are guarantors.

Contributorship

TL and MJG designed and conducted the survey. FS performed the analysis and wrote the first draft of the paper. All authors contributed to further drafts and all approved the final version.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Emma Ayres for administering the surveys and Janet Justice and Alison Stockford for data entry. We are very grateful to all the doctors who participated in the surveys.

Appendix 1. Frequency distribution of coded additional comments* made by the 2008 cohort three years after graduation (N = 885†)

| Theme/Subtheme | Negative | Neutral/mixed | Positive | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FY1-2 training | ||||

| Supervision, support from seniors | 25 | 3 | 3 | 31 |

| Adequacy of training | 38 | 6 | 20 | 64 |

| Working intensity | 13 | 0 | 0 | 13 |

| Any of the above | 93 | |||

| Specialty training | ||||

| Applications in/out & placements given | 81 | 1 | 2 | 84 |

| Supervision, support from seniors | 58 | 11 | 46 | 115 |

| Adequacy of training | 193 | 31 | 74 | 298 |

| Service work to training ratio | 83 | 1 | 0 | 84 |

| Provision of protected training sessions | 9 | 0 | 4 | 13 |

| E-portfolio, assessments | 70 | 2 | 0 | 72 |

| Volume of non-medic/mundane work, admin | 65 | 0 | 0 | 65 |

| Any of the above | 516 | |||

| Working conditions | ||||

| Pay & courses/exams/conferences costs | 74 | 0 | 1 | 75 |

| EWTD, working hours | 106 | 2 | 5 | 113 |

| Working intensity | 29 | 2 | 0 | 31 |

| Staffing | 43 | 0 | 0 | 43 |

| Rotas and cover for leave/absences | 150 | 0 | 1 | 151 |

| Accommodation, food, staff facilities | 17 | 0 | 0 | 17 |

| Attitudes to junior doctors from staff | 15 | 0 | 1 | 16 |

| Sexism, racism, ageism | 7 | 0 | 0 | 7 |

| Flexibility, maternity leave, carer time off | 51 | 1 | 4 | 56 |

| Location of posts | 49 | 0 | 0 | 49 |

| Any of the above | 464 | |||

| Lifestyle/personal | ||||

| Work/life balance, family, relationships | 70 | 2 | 6 | 78 |

| Stress, illness | 44 | 0 | 0 | 44 |

| Morale, job satisfaction | 35 | 4 | 33 | 72 |

| Any of the above | 181 | |||

| Working in medicine | ||||

| NHS and its management | 56 | 0 | 2 | 58 |

| NHS and government policy | 18 | 0 | 0 | 18 |

| UK vs. previous/current experience abroad | 60 | 0 | 2 | 62 |

| Safety, negligence, patient expectations | 36 | 0 | 0 | 36 |

| Any of the above | 163 | |||

| Future career | ||||

| Career advice | 42 | 1 | 4 | 47 |

| Timing of decision | 110 | 1 | 1 | 112 |

| Obtaining current/next position | 27 | 0 | 0 | 27 |

| Long term career | 16 | 2 | 1 | 19 |

| Leave UK or medicine | 52 | 1 | 0 | 53 |

| Any of the above | 227 | |||

| Other | 14 | 2 | 0 | 16 |

| Total | 1756 | 73 | 210 | 2039 |

| Percentage of comments | 86.1 | 3.6 | 10.3 | 100.0 |

Some doctors gave more than one reason and we counted each reason.

Number of doctors who wrote free text comments.

Appendix 2. Frequency and percentage distribution of themes, by gender: 2008 cohort three years after graduation

| Count |

Percentage |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male (n = 313) |

Female (n = 572) |

Male (n = 313) |

Female (n = 572) |

|||||||||

| Negative | Neutral/ mixed | Positive | Negative | Neutral/ mixed | Positive | Negative | Neutral/ mixed | Positive | Negative | Neutral/ mixed | Positive | |

| FY1-2 training | ||||||||||||

| Supervision, support from seniors | 5 | 0 | 1 | 20 | 3 | 2 | 1.6 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 3.5 | 0.5 | 0.4 |

| Adequacy of training | 18 | 3 | 5 | 20 | 3 | 15 | 5.7 | 1.0 | 1.6 | 3.5 | 0.5 | 2.6 |

| Working intensity | 2 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Specialty training | ||||||||||||

| Applications in/out & placements given | 31 | 0 | 1 | 50 | 1 | 1 | 9.9 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 8.7 | 0.2 | 0.2 |

| Supervision, support from seniors | 19 | 2 | 14 | 39 | 9 | 32 | 6.1 | 0.6 | 4.5 | 6.8 | 1.6 | 5.6 |

| Adequacy of training | 88^^^ | 7 | 22 | 105 | 24 | 52 | 28.0 | 2.2 | 7.0 | 18.4 | 4.2 | 9.1 |

| Service work to training ratio | 40^ | 0 | 0 | 43 | 1 | 0 | 12.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 7.5 | 0.2 | 0.0 |

| Provision of protected training sessions | 2 | 0 | 2 | 7 | 0 | 2 | 0.6 | 0.0 | 0.6 | 1.2 | 0.0 | 0.4 |

| E-portfolio, assessments | 38^^^ | 0 | 0 | 32 | 2 | 0 | 12.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 5.6 | 0.4 | 0.0 |

| Volume of non-medic/mundane work, admin | 24 | 0 | 0 | 41 | 0 | 0 | 7.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 7.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Working conditions | ||||||||||||

| Pay & courses/exams/ conferences costs | 35^ | 0 | 1 | 39 | 0 | 0 | 11.1 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 6.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| EWTR, working hours | 33 | 0 | 3 | 73 | 2 | 2 | 10.5 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 12.8 | 0.4 | 0.4 |

| Working intensity | 6 | 0 | 0 | 23 | 2 | 0 | 1.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 4.0 | 0.4 | 0.0 |

| Staffing | 12 | 0 | 0 | 31 | 0 | 0 | 3.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 5.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Rotas and cover for leave/absences | 39* | 0 | 1 | 111 | 0 | 0 | 12.4 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 19.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Accommodation, food, staff facilities | 5 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 1.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Attitudes to junior doctors from staff | 8 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 1 | 2.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.2 | 0.0 | 0.2 |

| Sexism, racism, ageism | 2 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Flexibility, maternity leave, carer time off | 7*** | 0 | 0 | 44 | 1 | 4 | 2.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 7.7 | 0.2 | 0.7 |

| Location of posts | 11 | 0 | 0 | 38 | 0 | 0 | 3.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 6.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Lifestyle/personal | ||||||||||||

| Work/life balance, family, relationships | 10*** | 0 | 3 | 60 | 2 | 3 | 3.2 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 10.5 | 0.4 | 0.5 |

| Stress, illness | 9 | 0 | 0 | 35 | 0 | 0 | 2.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 6.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Morale, job satisfaction | 14 | 1 | 13 | 21 | 3 | 20 | 4.5 | 0.3 | 4.1 | 3.7 | 0.5 | 3.5 |

| Working in medicine | ||||||||||||

| NHS and its management | 23 | 0 | 1 | 33 | 0 | 1 | 7.3 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 5.8 | 0.0 | 0.2 |

| NHS and government policy | 9 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 2.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| UK vs. previous/current experience abroad | 28 | 0 | 0 | 32 | 0 | 2 | 8.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 5.6 | 0.0 | 0.4 |

| Safety concerns | 14 | 0 | 0 | 22 | 0 | 0 | 4.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Future career | ||||||||||||

| Career advice | 11 | 1 | 0 | 31 | 0 | 4 | 3.5 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 5.4 | 0.0 | 0.7 |

| Timing of decision | 42 | 0 | 0 | 68 | 1 | 1 | 13.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 11.9 | 0.2 | 0.2 |

| Obtaining current/next position | 12 | 0 | 0 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 3.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Long term career | 3 | 2 | 0 | 13 | 0 | 1 | 1.0 | 0.6 | 0.0 | 2.3 | 0.0 | 0.2 |

| May/will work abroad/travel/ leave medicine | 17 | 0 | 0 | 35 | 1 | 0 | 5.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 6.1 | 0.2 | 0.0 |

| Other | 6 | 2 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 1.9 | 0.6 | 0.0 | 1.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

Notes. Significantly more negative comments from men than women: ^^^ p < 0.001, ^ p < 0.05; and significantly more negative comments from women than men: ***p < 0.001, *p < 0.05.

Provenance

Not commissioned; peer-reviewed by Jacky Hayden.

References

- 1.Department of Health. The foundation programme curriculum, London: Department of Health, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Department of Health. Modernising medical careers. The next steps: the future shape of foundation, specialist and general practice training programmes, London: Department of Health, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 3.British Medical Association. Fourth report August 2010: cohort study 2006 medical graduates, London: British Medical Association, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Temple J. Time for training: a review of the impact of the European Working Time Directive on the quality of training, London: Medical Education England, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maisonneuve JJ, Lambert TW, Goldacre MJ. Doctors' views about training and future careers expressed one year after graduation by UK-trained doctors: questionnaire surveys undertaken in 2009 and 2010. BMC Med Educ 2014; 14: 270–270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goldacre MJ, Davidson JM, Lambert TW. Career choices at the end of the pre-registration year of doctors who qualified in the United Kingdom in 1996. Med Educ 1999; 33: 882–889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lambert TW, Goldacre MJ, Edwards C, Parkhouse J. Career preferences of doctors who qualified in the United Kingdom in 1993 compared with those of doctors qualifying in 1974, 1977, 1980, and 1983. Br Med J 1996; 313: 19–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garcia J, Evans J, Reshaw M. “Is there anything else you would like to tell us” – methodological issues in the use of free-text comments from postal surveys. Qual Quan 2004; 38: 113–125. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Evans J, Goldacre MJ, Lambert TW. Views of junior doctors on the specialist registrar (SpR) training scheme: qualitative study of UK medical graduates. Med Educ 2002; 36: 1122–1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.General Medical Council. National Training Survey 2011: key findings, London: General Medical Council, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Royal College of Physicians. Census of consultant physicians and medical registrars in the UK, 2010: data and commentary, London: Royal Colleges of Physicians, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morrow G, Burford B, Carter M, Illing J. The impact of the working time regulations on medical education and training: final report on primary research. A report for the general medical council, Durham: Centre for Medical Education Research, Durham University, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 13.McNeill H, Brown JM, Shaw NJ. First year specialist trainees' engagement with reflective practice in the e-portfolio. Adv Health Sci Educ 2010; 15: 547–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnson S, Cai A, Riley P, Millar LM, McConkey H, Bannister C. A survey of core medical trainees' opinions on the eportfolio record of educational activities: beneficial and cost-effective? J R Coll Phys Edinburgh 2012; 42: 15–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pereira EAC, Dean BJF. British surgeons' experiences of a mandatory online workplace based assessment portfolio resurveyed three years on. J Surg Educ 2013; 70: 59–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McKavanagh P, Smyth A, Carragher A. Hospital consultants and workplace based assessments: How foundation doctors view these educational interactions? Postgrad Med J 2012; 88: 119–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Satele D, Freischlag J. Physicians married or partnered to physicians: a comparative study in the American College of Surgeons. J Am Coll Surg 2010; 211: 663–671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stamm M, Buddeberg-Fischer B. How do physicians and their partners coordinate their careers and private lives? Swiss Med Wly 2011; 141: w13179–w13179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meghen K, Sweeney C, Linehan C, O'Flynn S, Boylan G. Women in hospital medicine: facts, figures and personal experiences. Ir Med J 2013; 106: 39–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schueller-Weidekamm C, Kautzky-Willer A. Challenges of work-life balance for women physicians/mothers working in leadership positions. Gend Med 2012; 9: 244–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Buddeberg-Fischer B, Stamm M, Buddeberg C, et al. The impact of gender and parenthood on physicians' careers – professional and personal situation seven years after graduation. BMC Health Serv Res 2010; 10: 40–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]