Abstract

The tumor growth inhibition T/C ratio is commonly used to quantify treatment effects in drug screening tumor xenograft experiments. The T/C ratio is converted to an antitumor activity rating using an arbitrary cutoff point and often without any formal statistical inference. Here, we applied a nonparametric bootstrap method and a small sample likelihood ratio statistic to make a statistical inference of the T/C ratio, including both hypothesis testing and a confidence interval estimate. Furthermore, sample size and power are also discussed for statistical design of tumor xenograft experiments. Tumor xenograft data from an actual experiment were analyzed to illustrate the application.

Keywords: Bootstrap, Confidence interval, Hypothesis, Likelihood ratio, Log-normal, Sample size, Tumor growth inhibition, Xenografts

1. INTRODUCTION

In preclinical drug screening tumor xenograft experiments, human cancer cells are engrafted into mice to produce xenograft models. After tumors grow to a certain size, tumor-bearing mice are randomized into control (C) and treatment (T) groups, and the maximum tolerated dose of the drug is administered. The volume of each tumor (per mouse) is measured at the initiation of the study and periodically throughout the study. Mice are euthanized usually when the tumor volume reaches four times its initial volume, thus resulting in incomplete longitudinal tumor volume data. Statistical analysis of tumor xenograft data plays an important role in assessing the antitumor activity of the treatment. However, analysis of such data presents several statistical challenges, such as a limited number of available samples and missing data. To avoid missing data difficulties, one approach is to assess the treatment effect at the last time point with complete observations of both control and treatment groups. The treatment-to-control ratio (T/C) at the last time point with complete observations is then used to quantify the antitumor activity of the drug. The T/C ratio is converted to an antitumor activity rating using an arbitrary cutoff point (i.e., T/C ≤ 0.45) without any formal statistical inference (Corbett et al., 2003; Houghton et al., 2007). The disadvantages of this approach are obvious. It discards useful data and could result in a considerable loss of efficency. Furthermore, the degree of antitumor activity is assessed on the basis of an arbitrary cutoff point, which ignores the noise in the data. Several new statistical methods have recently been developed to use the observed data in a more efficient way. Vardi et al. (2001) proposed two nonparametric two-sample U-tests. The proposed tests, however, assess the treatment effect by the cross-treatment difference instead of ratio and yields only a p-value. Tan et al. (2002) proposed a small-sample t-test. They deal with the missing data via the expectation maximization algorithm. The method, however, was derived on the basis of restrictive model assumption: a multivariate normal distribution for the repeated log tumor volumes with a Toeplitz covariance matrix. Furthermore, the method generates the p-value only and does not quantify the tumor growth inhibition. That is why the T/C ratio is still widely used in drug screening tumor xenograft data analysis (Atadja et al., 2004; Bissery et al., 1991; Corbett et al., 2003; Houghton et al., 2007). Here, we propose a valid statistical inference for the T/C ratio to assess the treatment effect, instead of using an arbitrary cutoff point.

Hothorn (2006) proposed an interval approach for the T/C ratio. Antitumor activity is assessed by the upper limit of the confidence interval of the T/C ratio. Hothorn’s interval estimate of the T/C ratio is obtained on the basis of an assumed normal distribution of the tumor volume. Although Hothorn pointed out that a log-normal distribution could be used for inference of the ratio, there was no further discussion in his report. Control tumors often follow an exponential growth curve. Therefore, a log-normal distribution of tumor volume is a more reasonable assumption (Heitjan et al., 1993; Tan et al., 2002). For small-sample tumor xenograft data, however, the underlying distribution is sometime difficult to assess. Therefore, we propose a nonparametric bootstrap method and a small-sample likelihood ratio method to make a statistical inference of the T/C ratio. If the underlying distribution is difficult to assess, then the nonparametric bootstrap method can be used. If a log-normal distribution can be assumed, then the small-sample likelihood ratio statistic can be used. Furthermore, sample size and power calculation are also discussed for the purpose of statistical design of tumor xenograft experiments. Tumor xenograft data from an actual experiment were analyzed to illustrate the application.

2. INFERENCE FOR T/C RATIO

Calculating a T/C ratio from raw tumor volumes could result in a biased estimate of the drug effect because of heterogeneous initial tumor volumes. Therefore, the raw tumor volume is first divided by its initial tumor volume to yield the relative tumor volume. For notation convenience, let Vd be the relative tumor volume of group d at a given time with mean θd and variance , where d = T or C to represent the treatment or control group, respectively. The ratio of means

represents the T/C ratio. Suppose {VTi, i = 1,…, n} and {VCj, j = 1, …, m} are the observed relative tumor volumes at a given time for the treatment and control groups, respectively. Then the T/C ratio of γ can be estimated by the ratio of sample means,

which quantifies the treatment effect (0 < γ̂ ≤ 1). In general, a small value of γ̂ indicates a strong treatment effect. The standard error of γ̂ can be estimated by the Delta method,

where V̅d and are the sample mean and variance of the relative tumor volumes of group d.

A significant treatment effect can be assessed by testing the following hypothesis:

| (1) |

However, confidence intervals are often preferred over hypothesis-testing procedures because they provide information regarding the size of the effect and its uncertainty. Both hypothesis testing and interval estimate of the T/C ratio are discussed in this section under two scenarios: nonparametric inference and parametric inference.

2.1. Scenario 1: Nonparametric Inference—Bootstrap Method

To make the nonparametric bootstrap inference (Efron and Tibshirani, 1993) of T/C ratio γ, we take a log transformation of γ as

An estimate of the standard error of θ̂ = log(γ̂) is given by

| (2) |

Because the only change of interest is the tumor volume reduction after treatment, a one-sided confidence interval will be constructed.

A bootstrap p-value and 100(1 − α)% one-sided confidence upper limit of the bootstrap interval can be estimated by following bootstrap procedures.

Generate B independent bootstrap samples of relative tumor volume from each group, and , b = 1, …, B.

Compute the bootstrap replication γ̂*b, where for b = 1, …, B.

- A 100(1 − α)% bootstrap t-interval upper limit is obtained directly from the bootstrap sample,

where θ̂*b = log(γ̂*b) and are calculated using Eq. (2) for the bootstrap Sample and θ̂ = log(γ̂). Let the αth percentile of {t*b, b = 1, …, B} be estimated by the value of t̂α such that #{t*b < t̂α}/B = α. Then an one-sided upper limit of the bootstrap t-interval is given by - A bootstrap p-value for hypothesis (1) is obtained by

Where .

2.2. Scenario 2: Parametric Inference—Small-Sample Likelihood Method

In this scenario, we assume with unequal variances between two groups; that is, . The relationship between the mean μd and variance of log-transformed variable Xd and mean θd and variance of original variable Vd is given by and , also given in Table 1. The T/C ratio γ = θT/θC is given by . Then hypothesis (1) is equivalent to the following hypothesis:

where . The corresponding log-likelihood function ℓ(ψ, λ) is given by

where is a minimum sufficient statistic and λ = (μC, σT, σC) is a vector nuisance parameter. The hypothesis can be tested by the signed log-likelihood ratio statistic r (Cox and Hinkley, 1974), which is simplified as

where , and (ψ̂, λ̂) = (ψ̂, μ̂C, σ̂T, σ̂C) and (ψ, λ̂ψ) = (ψ̂, μ̂Cψ, σ̂Tψ, σ̂Cψ) are the maximum likelihood estimate and constrained maximum likelihood estimate for a given ψ, respectively. It is well known that under the null hypothesis of , r, is approximately distributed as a standard normal, but this is not accurate for small-samples. Therefore, a small-sample likelihood ratio statistic (Barndorff-Nielsen and Cox, 1994) is constructed as follows to make the statistical inference for ψ:

where r(ψ) is the signed log-likelihood ratio and u(ψ) is given by Fraser et al. (1999) as follows:

where the sample-space derivatives ℓ;t(ψ, λ) and mixed derivatives ℓλ;t(ψ, λ) are given by

and

respectively. The observed nuisance information matrix is a symmetric matrix with upper right submatrix as follows:

The determinants of the observed information matrix and mixed derivative matrix are given by and . Detailed derivations of these quantities were given by Wu et al. (2002). The small-sample likelihood ratio statistic r* is also approximately normally distributed but it is highly accurate even for small-samples (Barndorff-Nielsen, 1991). Therefore, a one-sided p-value for testing hypothesis (1) is given by

where is the observed value of r* under the null hypothesis. The one-sided upper limit of the 100(1 −α)% confidence interval of ψ is obtained by solving r*(ψ̂U) = z1−α; therefore, the upper limit of γ is given by

Table 1.

Parameters of normal and log-normal distribution

| Variable | Distribution | Mean | Variance | T/C ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Xd = log(Vd) | Normal | μd | ||

| Vd | Log-normal | γ = θT/θC |

3. REAL TUMOR XENOGRAFT EXPERIMENTAL DATA

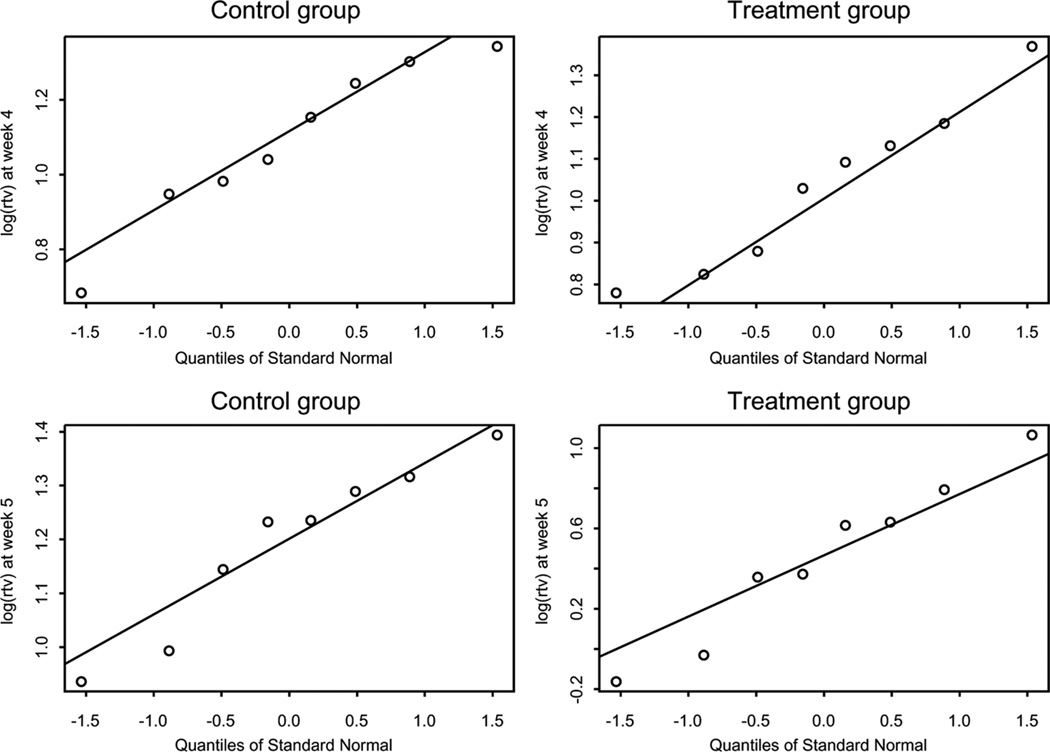

For an example, data from a real tumor xenograft experiment conducted by the Pediatric Preclinical Testing Program (PPTP) (Kolb et al., 2008) were used to illustrate the methods proposed in previous section. In this study, human antibody SCH 717454 at a dose of 0.5mg per mouse was administered twice per week for 4 weeks by intraperitoneal injection with a 2-week follow-up. Table 2 shows the relative tumor volumes of 16 mice (8 each in the control and treatment groups) from week 1 to week 5 with complete observations for tumor line BT-50. To check the normality assumption of the log tumor volume, the Shapiro–Wilk tests gave p-values of 0.646 and 0.794 for the control and treatment groups, respectively, at week 4 and 0.500 and 0.845 at week 5. Q–Q plots are shown in Figure 1. Both Shapiro–Wilk tests and Q–Q plots suggested that the normal distribution assumption of the log tumor volume was satisfied. Furthermore, F-tests were conducted to check the equal variance assumptions. Because of the nonrobustness of the F-test against normality assumption, permutation tests were also conducted to assess the equal variance of two groups. The F-tests and permutation tests respectively gave p-values of 0.814 and 0.801 for week 4 and 0.023 and 0.008 for week 5. Therefore, equal variance assumptions were satisfied for log tumor volumes between control and treatment at week 4 but not at week 5. For week 4 data, the estimate (standard error) of the T/C ratio was 0.948 (0.097), the two-sample t-test gave a p-value of 0.682, and the 95% confidence interval upper limit was 1.991. Neither the p-value nor the upper limit showed a significant treatment effect at week 4. For week 5 data, the estimate (standard error) of the T/C ratio was 0.508 (0.076), the small-sample likelihood ratio test gave a p-value of 0.007 (Bonferroni adjusted p-value = 0.014), and the 95% confidence interval upper limit was 0.927. Both the p-value and upper limit showed a significant treatment effect at week 5. The Shapiro–Wilk test may lack power to assess the log-normal distribution assumption with small samples. Therefore, the nonparametric bootstrap inference is attractive if the log-normal distribution assumption is not guaranteed. The bootstrap t-tests gave p-values of 0.327 and 0.002 (Bonferroni adjusted p-value = 0.004) for week 4 and week 5 data, respectively. The upper limits of bootstrap t-intervals were 1.157 and 0.684 for week 4 and week 5 data, respectively. Therefore, both parametric small-sample likelihood inference and nonparametric bootstrap inference gave the same conclusions. The results are summarized in Table 3.

Table 2.

Relative tumor volumes of BT-50 SCH 717454 tumor xenograft model

| Mouse | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Week | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| Control | 1 | 1.02 | 1.08 | 1.15 | 1.03 | 1.92 | 1.47 | 1.77 | 1.20 |

| 2 | 1.77 | 1.64 | 2.68 | 1.89 | 1.95 | 1.71 | 2.45 | 1.53 | |

| 3 | 3.13 | 3.23 | 2.68 | 2.36 | 2.45 | 2.06 | 2.69 | 1.89 | |

| 4 | 3.47 | 3.68 | 2.58 | 2.67 | 3.17 | 2.83 | 3.83 | 1.98 | |

| 5 | 3.63 | 4.03 | 3.44 | 2.70 | 3.43 | 3.14 | 3.73 | 2.55 | |

| Drug | 1 | 1.38 | 1.63 | 1.21 | 1.70 | 1.07 | 1.18 | 1.58 | 1.65 |

| 2 | 2.56 | 1.81 | 1.73 | 2.10 | 1.56 | 1.45 | 2.69 | 2.13 | |

| 3 | 2.69 | 2.13 | 1.8 | 2.00 | 2.06 | 2.09 | 2.54 | 2.96 | |

| 4 | 2.80 | 3.27 | 2.41 | 3.10 | 2.18 | 2.28 | 2.98 | 3.93 | |

| 5 | 1.88 | 2.21 | 0.85 | 1.45 | 1.43 | 0.97 | 2.90 | 1.85 | |

Figure 1.

Q–Q plot of log relative tumor volume for week 4 data and week 5 data.

Table 3.

Data analysis summary of BT-50 SCH 717454 tumor xenograft data

| Likelihood method | Bootstrap method | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Week | F -test (P-testa) | T/C ratio (se) | γ̂U | p-Value | γ̂U | p-Value |

| 4 | 0.814 (0.801) | 0.948 (0.097) | 1.991 | 0.682 | 1.157 | 0.327 |

| 5 | 0.023 (0.008) | 0.508 (0.076) | 0.927 | 0.007 | 0.684 | 0.002 |

Permutation test based on 2,000 random permutation samples.

4. SAMPLE SIZE

Preclinical tumor xenograft experiments are often conducted without adequate consideration of the study power and sample size. The number of mice used in tumor xenograft studies tends to be quite arbitrary. For example, 5 and 7 (Thompson et al., 1999), 10 (Houghton et al., 2007), and 21 (Hothorn, 2006) mice per group were used in respected studies. There is little literature available regarding the sample size and power calculations for tumor xenograft experiments. To provide some guidelines for statistical design for such experiments, sample size and power calculations are discussed based on the hypothesis of T/C ratio for tumor growth inhibition studies.

To formulate the sample size calculation, assume equal numbers of mice (n) to be tested in each group, and the log tumor volume Xd = log(Vd) follows a normal distribution with mean μd and common variance σ2 between the two groups. Then it is easy to see that the following relationships hold (van Belle and Martin, 1993):

where CV is the common coefficient of variation of Vd.

Define

where X̅d and S2 are the sample mean and pooled sample variance, respectively. Under the alternative Ha for the hypothesis (1), T follows a noncentral t-distribution with a noncentral parameter δ and degree freedom of 2n − 2,

where the noncentral parameter δ is given by

Therefore, the power or sample size can be calculated from the following equation:

where tα,2n−2 is the αth percentile of t-distribution with degree freedom of 2n − 2. The power or sample size calculation has been implemented in SAS/PROC POWER. The sample sizes per group calculated for various CV and T/C values are listed in Table 4. From this calculation, we can conclude that for a moderate CV (0.6) value, groups of 9 mice each have at least 80% power to detect a 50% reduction of mean relative tumor volume. Investigators can select the sample size for their experiments based on the hypothesis of effect size and historical information of the coefficient of variation of the tumor volume.

Table 4.

Number of animals per group to attain a power of 80% for a one-sided test with α = 0.05

| T/C | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CV | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.8 |

| 0.1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 0.2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 11 |

| 0.3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 10 | 23 |

| 0.4 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 8 | 16 | 38 |

| 0.5 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 12 | 23 | 57 |

| 0.6 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 9 | 16 | 31 | 78 |

| 0.7 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 12 | 20 | 40 | 100 |

| 0.8 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 9 | 14 | 25 | 49 | 124 |

| 0.9 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 10 | 16 | 29 | 59 | 149 |

| 1.0 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 11 | 19 | 34 | 69 | 173 |

Note. CV, common coefficient of variation of the relative tumor volume of two groups.

5. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

Two methods have been proposed to make a statistical inference for the tumor growth inhibition T/C ratio. If a log-normal distribution of tumor volume can be assumed, then the small-sample likelihood inference is suitable. If the underlying distribution of tumor volume is difficult to assess, then the nonparametric bootstrap method can be used. Furthermore, sample sizes were derived for the purpose of statistical design of drug screening tumor xenograft experiments. The proposed methods are easy to implement. An S-plus code for the analysis is available from the author. However, antitumor activity assessment based on the T/C ratio could result in substantial efficiency loss if at least one observation missing occurs early in the experiment. The methods proposed by Vardi et al. (2001) and Tan et al. (2002) are more efficient for handling the missing data. However, neither method quantifies the treatment effect, yielding only a p-value with no confidence interval. Longitudinal modeling of tumor xenograft data is attractive (Heitjan et al., 1993). It incorporates the correlation structure of the repeated observation and is valid under the assumption of data missing at random. However, longitudinal modeling requires more restrictive assumptions, such as normality (log-normality), autoregressive correlation, and growth curve. Finally, a reviewer pointed out that in practice it is more important to investigate the homogeneity of the T/C ratio across several tumor models. Johnson et al. (2001, p. 1430) pointed out that “activity in multiple xenograft models is a useful predictor of clinical activity.” The work of Voskoglou-Nimikos et al. (2003) appears to support this conclusion.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The author is thankful to the associate editor and anonymous referees whose careful reading and constructive comments improved this article. This work was supported in part by National Cancer Institute (NCI) support grant CA21765, NO1-CM-42216, and the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities (ALSAC).

REFERENCES

- Atadja P, Gao L, Kwon P, Trogani N, Walker H, Hsu M, Yeleswarapu L, Chandramouli N, Perez L, Versace R, Wu A, Sambucetti L, Lassota P, Cohen D, Bair K, Wood A, Remiszewski S. Selective growth inhibition of tumor cells by a novel histone deacetylase inhibitor, NVP-LAQ824. Cancer Res. 2004;64:689–695. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-2043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barndorff-Nielsen OE. Modified signed log likelihood ratio. Biometrika. 1991;78:557–563. [Google Scholar]

- Barndorff-Nielsen OE, Cox DR. Inference and Asymptotics. London: Chapman and Hall; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Bissery MC, Guenard D, Gueritte-Voegelein F, Lavelle F. Experimental antitumor activity of taxotere (RP 56976, NSC 629503), a taxol analogue. Cancer Res. 1991;51:4845–4852. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbett TH, White K, Polin L, Kushner J, Paluch J, Shih C, Grossman CS. Discovery and preclinical antitumor efficacy evaluations of LY32262 and LY33169. Investig. New Drugs. 2003;21:33–45. doi: 10.1023/a:1022912208877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox DR, Hinkley DV. Theoretical Statistics. London: Chapman and Hall; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Efron B, Tibshirani RJ. An Introduction to the Bootstrap. New York: Chapman and Hall; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Fraser DAS, Reid N, Wu J. A simple general formula for tail probabilities for frequentist and Bayesian inference. Biometrika. 1999;86:249–264. [Google Scholar]

- Heitjan DF, Manni A, Santen RJ. Statistical analysis of in vivo tumor growth experiments. Cancer Res. 1993;53:6042–6050. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houghton PJ, Morton CL, Tucker C, Payne D, Favours E, Cole C, Gorlick R, Kolb EA, Zhang W, Lock R, Carol H, Tajbakhsh M, Reynolds CP, Maris JM, Courtright J, Keir ST, Friedman HS, Stopford C, Zeidner J, Wu J, Liu T, Billups CA, Khan J, Ansher S, Zhang J, Smith MA. The pediatric preclinical testing program: Description of models and early testing results. Pediatr. Blood Cancer. 2007;49:928–940. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hothorn L. Statistical analysis of in vivo anticancer experiments: Tumor growth inhibition. Drug Inform. J. 2006;40:229–238. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JI, Decker S, Zaharevitz D, Rubinstein LV, Venditti JM, Schepartz S, Kalyandrug S, Christian M, Arbuck S, Hollingshead M, Sausville EA. Relationships between drug activity in NCI preclinical in vitro and in vivo models and early clinical trials. Br. J. Cancer. 2001;84:1424–1431. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2001.1796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolb EA, Gorlick R, Houghton PJ, Morton CL, Lock R, Carol H, Reynolds CP, Maris JM, Keir ST, Billups CA, Smith MA. Initial testing (stage 1) of a monoclonal antibody (SCH 717454) against the IGF-1 receptor by the pediatric preclinical testing program. Pediatr. Blood Cancer. 2008;50:1190–1197. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan M, Fang HB, Tian GL, Houghton PJ. Small-sample inference for incomplete longitudinal data with truncation and censoring in tumor xenograft models. Biometrics. 2002;58:612–620. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2002.00612.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson J, George EO, Poquette CA, Cheshire PJ, Richmond LB, de Graaf SS, Ma M, Stewart CF, Houghton PJ. Synergy of topotecan in combination with vincristine for treatment of pediatric solid tumor xenografts. Clin. Cancer Res. 1999;5:3617–3631. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Belle G, Martin DC. Sample size as a function of coefficient of variation and ratio of means. Biometrics. 1993;58:612–620. [Google Scholar]

- Vardi Y, Ying ZL, Zhang CH. Two-sample tests for growth curves under dependent right censoring. Biometrika. 2001;88:949–960. [Google Scholar]

- Voskoglou-Nimikos T, Pater JL, Seymour L. Clinical predictive value of the in vitro cell line, human xenograft and mouse allograft preclinical cancer models. Clin. Cancer Res. 2003;9:4227–4239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wn J, Jiang G, Wong ACM, Sun X. Likelihood analysis for the ratio of means of two independent log-normal distributions. Biometrics. 2002;58:463–469. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2002.00463.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]