Abstract

Introduction

Despite the high prevalence of obesity among African-American women and modest success in behavioral weight loss interventions, the development and testing of weight management interventions using a community-based participatory research (CBPR) approach have been limited. Doing Me!: Sisters Standing Together for Healthy Mind and Body (Doing Me!) is an intervention adapted from an evidence-based behavioral obesity intervention using a CBPR approach. The purpose of Doing Me! is to test the feasibility and acceptability of this adapted intervention and determine its efficacy in achieving improvements in anthropometrics, diet, and physical activity.

Methods

Sixty African-American women, from a low-income, urban community, aged 30–65 years will be randomized to one of two arms: 16-week Doing Me! (n = 30) or waitlist control (n = 30). Doing Me! employs CBPR methodology to involve community stakeholders and members during the planning, development, implementation, and evaluation phases of the intervention. There will be thirty-two 90-minute sessions incorporating 45 min of instruction on diet, physical activity, and/or weight management plus 45 min of physical activity. Data will be collected at baseline and post-intervention (16 weeks).

Discussion

Doing Me! is one of the first CBPR studies to examine the feasibility/acceptability of an adapted evidence-based behavioral weight loss intervention designed for obese African-American women. CBPR may be an effective strategy for implementing a weight management intervention among this high-risk population.

Keywords: African-American women, Obesity, Community-based participatory research (CBPR), weight loss, Behavioral intervention

1. Introduction

In the United States, obesity rates have remained substantially high over the last several decades, making it a significant public health concern [1]. African-American women have the highest prevalence of obesity compared with any other subgroup, with 56.6% classified as obese, defined as a body mass index (BMI) ≥ 30 kg/m2, compared with 32.8% of their white counterparts [1]. In general, behavioral weight loss interventions have been successful in reducing weight among obese adults (e.g., [2–4]). According to the National Institute of Health clinical guidelines, behavioral weight loss interventions featuring diet (decreased energy intake), physical activity (increased energy expenditure), and behavioral therapy (behavior modification) components typically result in approximately 5–10% weight loss after 6 months of intervention [2,5,6]. However, this degree of success is commonly not observed among African-American women [7,8]. For example, in the Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP), a successful intensive behavioral lifestyle intervention with a weight loss goal of 7% body weight, African-American women had the lowest level of weight loss success, with an average weight loss of only 63% of that observed among White women [9,10].

A number of explanations have been put forth for the modest success of weight loss programs among African-American women [8,11–13]. These include lack of access to weight management resources [14–16], cultural preference for a larger body size [17], fewer options for leisure time physical activity [18], lower metabolic rate [19], genetic predisposition [20], lower sleep quality [21,22], higher levels of stress [14,23], and lower socioeconomic status [24,25].

Although evidence suggests that environmental and sociocultural factors influence weight-related behaviors in African-American women [11], most weight loss trials do not address barriers beyond individual-level factors related to diet and physical activity [12,26,27]. Additionally, few interventions have been developed with input specifically from the African-American community [10,12,22]. Increasing attention has been paid to the use of community-based participatory research (CBPR) in the development of behavioral interventions [28]. CBPR employs a partnership approach to research that equitably involves all partners, including community members, throughout the research process to contribute their expertise and share in decision-making [29].

The goal of CBPR is to combine knowledge and increase trust between partners in order to promote community health and work toward reducing health disparities. CBPR has been recommended as an effective approach to promote behavior change in underserved populations [30]. Yet, few studies have used CBPR to address obesity in high-risk groups ([31–36]); and no published studies to our knowledge have employed CBPR within the context of a randomized controlled trial (RCT) to encourage weight loss in low-income African-American women.

Given the limitations of the current literature, we adapted an evidenced-based intervention, “Obesity Reduction Black Intervention Trial” (ORBIT) [37–39], using CBPR to create “Doing Me! Sisters Standing Together for a Healthy Mind and Body” (Doing Me!), a culturally relevant, community-based weight loss intervention targeting low-income African-American women 30–65 years of age. ORBIT was a RCT that focused on weight loss and weight maintenance in 213 obese African-American women. Women were randomized to a 6-month active intervention and followed by a 12-month maintenance intervention or a no treatment control group. The mean weight loss at 6 months was 3.0 kg and a gain of 0.2 in the control group (p < 0.001). Both groups gained weight between 6 and 18 months (mean 1.0 kg in the intervention group and 0.1 kg in the control group), though there was still a significant difference in weight loss between groups at 18 months (−2.3 kg vs. 0.5 kg, p = .003). ORBIT demonstrated modest improvements in the weight management of African-American women, but was delivered in a university setting and included limited community input in the development. Additional details about the study design and results of ORBIT are provided elsewhere [37,38].

Doing Me! builds on a nine year partnership between faculty at the University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC), the Englewood Neighborhood Health Center (ENHC), a community clinic operated by the City of Chicago, and Teamwork Englewood (TE), a local non-profit. Initiated in 2006, academic and university partners came together to assess community factors that contribute to disparities in diet-related health conditions, food insecurity, and lack of healthy food access. The work of the partnership revealed a need for additional community-based weight management, diet, and physical activity resources.

The purpose of Doing Me! is to test the feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary efficacy of adapting an evidence-based intervention (ORBIT) using CBPR. This paper provides the intervention rationale, study design, and methods. Age, comorbidities, and multiple psychosocial variables will be tested as potential moderators, and energy balance (diet and physical activity) and adherence variables will be tested as potential mediators. We hypothesize that Doing Me! will be feasible and acceptable among low-income obese African-American women and that those women randomized to the active intervention will lose more weight than those randomized to a waitlist control condition post-intervention (16 weeks).

2. Study design

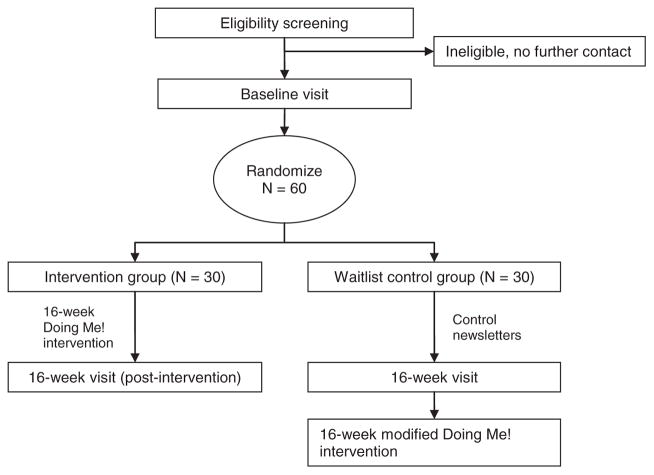

Sixty obese (BMI > 30 kg/m2) African-American women will be randomized to one of two arms: 16-week intervention (n = 30) or waitlist control (n = 30), as shown in Fig. 1. Data will be collected at baseline (0 weeks) and post-intervention (16 weeks) to assess and compare changes in weight and related behaviors (e.g., diet, physical activity, blood pressure) between the two groups. Additionally, process data will be collected throughout the study to better understand the feasibility and acceptability of the intervention (e.g., attendance logs, feedback from participants during sessions, post-intervention questions on acceptability).

Fig. 1.

Study design, Doing Me!

A major focus of Doing Me! is to identify community and culturally-relevant intervention approaches to promote weight loss in low-income African-American women. Accordingly, at the end of the 16-week intervention, prior to administering the program to the waitlist control group, community and academic partners will review process evaluation and post-intervention data to determine if aspects of the program format and delivery need to be modified to make the intervention more user-friendly (e.g., change times the intervention is offered, location, etc.). However, the main components of the intervention will not change. Post-intervention assessments will also be administered to the waitlist control group after the completion of the intervention. Survey measures and anthropometric assessments will be identical at each time point for both groups.

3. Theoretical framework and methods

3.1. Theoretical framework

The Doing Me! intervention was guided by Social Cognitive Theory (SCT) [40] and included principles of cultural sensitivity. SCT is an interpersonal theory that suggests behavior can be explained by the dynamic interaction between behavior, personal factors, and the environment. Consistent with SCT, intervention sessions will be designed to increase participants’ self-efficacy (confidence or belief in the ability to perform a given behavior), self-regulation (self-control through self-monitoring, goal-setting, feedback, self-reward, self-instruction, and enlistment of social support), and behavioral capability (providing tools, enhancing skills, and raising awareness about resources to make the behavior easier) [41]. Additionally, highlighting aspects of observational learning (modeling), Doing Me! sessions will be delivered by African-American staff and instructors who will provide examples of how to successfully change weight-related behaviors within the context of the local community. Principles of cultural sensitivity have also been incorporated into the design and delivery, and evaluation of the intervention including aspects of surface (e.g., R&B music, traditional recipes, and food options) and deep structure culture (e.g., spirituality, family roles, and discrimination) [42–44].

3.2. Community engagement and intervention development

The setting for Doing Me! is the Greater Englewood community. Greater Englewood is composed of Englewood and West Englewood, two of the 77 officially designated community areas in the City of Chicago [39]. Located seven miles south of Chicago’s downtown, Greater Englewood is a community with a rich history and active community organizations. In 2011, Englewood and West Englewood had a combined population of approximately 60,000, with nearly 97% of residents being African-American. About 40% of individuals had family incomes below the federal poverty line [45]. Both communities experience a high burden of poverty, unemployment, and chronic diet-related diseases [45].

An advisory board within the broader academic/community partnership will be developed specifically to guide the development and evaluation of Doing Me! The goal for the Doing Me! Advisory Board is to enhance the community relevance of the project by reviewing recruitment strategies, intervention components, and cultural relevance. A diverse group of local leaders, health care providers, community members, advocates, and local researchers who are experienced in CBPR will be invited to serve on the board.

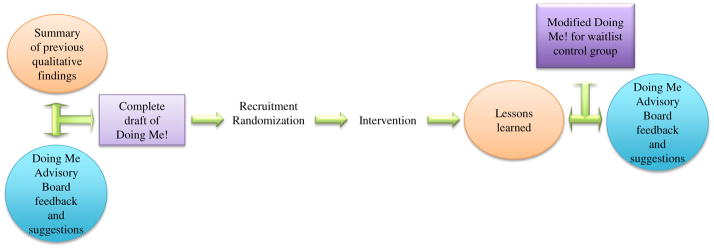

To assess the needs of the target community and to inform adaptation of the ORBIT intervention, the board will review the data collected from previous studies in the Greater Englewood community [46–49]. These data include numerous individual ethnographic interviews, observations, photos, and food access diaries describing contributors to dietary and physical activity behaviors in the local community. Data from our food access audits (e.g., corner/grocery store assessments and block by block resource audits) will also be used to inform the adaptation of the ORBIT intervention. For example, results from the food access audits identified an urban farm and a farmer’s market that could be used by community participants to access healthier food options. In addition, data from the ethnographic interviews revealed that many African-American women view hair maintenance as a barrier to being physically active. As a result, the original intervention was modified to include an opportunity for participants to consult with an African-American hairdresser on hair care, styles, and maintenance that support a physically active lifestyle. Additionally, African-American women reported that stress associated with multiple social and family roles and racism/discrimination in the workplace could potentially serve as a barrier to weight loss. Consequently, intervention sessions were added that focus on management of life stressors. The original ORBIT sessions and the suggested modifications will be presented to the Doing Me! Advisory Board for additional feedback and suggestions regarding the development of Doing Me!. After the treatment group receives the intervention, the Doing Me! Advisory Board will convene to discuss lessons learned with the purpose of adjusting the delivery format if needed prior to implementing the intervention with the waitlist control group (see Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Doing Me! intervention development with Doing Me! Advisory Board feedback.

3.3. Intervention implementation

3.3.1. Eligibility criteria

Eligible participants include English-speaking females, who self-identify as African-American or Black, aged 30–65 years, with BMI 30–55 kg/m2, reporting no contraindications for physical activity (e.g., 30 min of uninterrupted walking each day), are able to provide approval for participation by a physician, and are able to attend intervention classes at the scheduled times.

Exclusion criteria include plans to move out of the Chicago land area during the course of the study, pregnancy, nursing, or planning a pregnancy within the course of the study period, consuming more than two alcoholic drinks per day on a daily basis, and current use of illegal drugs. Participants unable to exercise due to emphysema or chronic bronchitis, current serious physical illness (e.g., cancer), and those who use a cane, walker, wheelchair, or other device for mobility will be excluded. To minimize potential confounders, only one member per household is eligible to enroll. Individuals cannot be concurrently enrolled in any other weight loss programs, including taking weight loss medications prescribed by a doctor or planning to have weight loss surgery.

3.3.2. Recruitment of study participants

Doing Me! will target residents from the Greater Englewood and surrounding communities. Participants will be recruited in multiple ways. Recruitment information will be distributed through the two primary community partners ENHC and TE, as well as community events (e.g., community meetings, block parties, and local park activities). ENHC is one of five comprehensive health clinics operated by the City of Chicago and provides primary health care, as well as Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children, STD, behavioral health, and dental services to low-income families residing in the Englewood area. ENHC sees approximately 23,000 patients annually, with the majority being African-American women. Formed in 2003 through support from the Local Initiatives Support Corporation (LISC) and the MacArthur Foundation, TE includes a consortium of over 100 community partners and provides services to residents community-wide. The goal of TE is to unite the many organizations serving Englewood residents and work toward the common goal of building a stronger community.

We will use a combination of proactive and reactive recruitment strategies, including communicating the value of participation for the subject’s larger community, offering financial compensation for participating in data collection, conducting data collection and intervention sessions in the evenings or on weekends, and seeking feedback from the Doing Me! Advisory Board on recruitment and study methodology [50]. Presentations and brochures will be provided to ENHC and TE for them to share study information with community residents and other individuals served by the clinic and community programs. We expect to recruit an equal number of participants from each of the various recruitments sites. Participants enrolled in the ORBIT trial reported that they preferred evening sessions to daytime sessions. We will work with the community advisory board for Doing Me! to determine the best time of day to offer sessions (day, night, and weekend session to accommodate a variety of schedules).

3.3.3. Eligibility screening and data collection

Women will be recruited in person, and those who express interest in the study will be further assessed for eligibility over the telephone. Eligible women will be scheduled for a baseline appointment where they will provide written informed consent and complete a baseline interview. Based on our recruitment numbers from the ORBIT study, we estimate that we will need to screen about 200 women to reach our target goal of 60 women (about 30% of 200) (Fitzgibbon et al. 2008). Retention rates in previous weight loss studies with African-American women ranged from 75% to 95% [12,31,51]. In ORBIT, 93% of participants were retained at 6 months [37]. We anticipate similar retention rates in the Doing Me! study and estimate about 10% loss to follow-up at 16 weeks.

Trained research assistants, research staff, and study investigators will conduct all interviews. Each assessment will take approximately 90 min and will be collected at baseline and 16 weeks (Table 2). Whenever possible, we selected measures that have been used with African-American populations in previous studies. Participants will be compensated $25.00 for completing the baseline assessment, and will be compensated an additional $25.00 for completing any post-intervention assessment.

Table 2.

Summary of measures used in Doing Me!

| Variable | Name and description of measure |

|---|---|

| Primary outcomes | |

| Body mass index (BMI). | Measure height (baseline only) using a portable stadiometer and measure weight using a digital scale with participants wearing light clothes and no shoes. BMI is calculated as weight (kg)/height (m)2. Two measurements for height and weight are taken. If there is a discrepancy of more than 0.5 cm for height or 0.2 kg for weight between the first and second measurements, a third measurement is taken. The mean of the two most closely aligned measurements is used for analyses |

| Waist circumference | Measures with participant standing without outer garments and with empty pockets. Waist is measured at the level midway between the lower rib margin and the iliac crest, with the participant breathing out gently. Two measurements are taken. If there is a discrepancy of more than 1 cm, a third measurement is taken. The mean of the two measurements most closely aligned are used for analyses. |

| Blood pressure | Staff members measure diastolic and systolic blood pressure 3 times using a standard protocol to calculate average blood pressure (4-items) [59]. |

| Secondary outcomes | |

| Diet | 24-hour diet recall. Dietary assessment intended to document the type and amount of the foods and beverages consumed over a 24-hour period. Gold standard for recording energy consumption. |

| Diet | Global diet. Self-reported servings of fruits and vegetables usually eaten per day in addition to times fast food is eaten per week (3-items) [46]. |

| Physical activity | Godin Leisure-Time Exercise Questionnaire. Self-reported frequency per week of strenuous (heart beats rapidly), moderate (not exhausting) and mild (minimal effort) exercise for more than 15 min in addition to frequency of leisure and sedentary activity per week (11-items) [49]. |

| Physical activity (accelerometer) | Objective. The limitations of self-reported physical activity are well established. Therefore, we will use the ActiGraph GT3X activity monitor to obtain an objective measure of physical activity (ActiGraph, LLC, Pensacola, FL). The ActiGraph is a small, lightweight (3.8 × 3.7 × 1.8 cm, 27 g) triaxial accelerometer designed to detect normal body motion and filter out motion from other sources [48]. |

| Demographics and health history | |

| Demographic interview | The demographic interview includes date of birth, the number of people in the household, educational attainment, employment status, marital status, income level, and public aid (13-items) [60]. |

| Health history | Self-report of any health problems diagnosed by physician or perceived by participant. Sixteen specific illnesses were asked such as diabetes, hypertension, and asthma as well as an open response. Additionally 6 questions were asked to assess overall health perception e.g., Do you think your current weight is a health problem? (24-items). |

| Exploratory | |

| We selected a number of measures to conduct exploratory analyses of mediators and moderators of weight loss specifically for African-American women residing in the Greater Englewood Community. | |

| Self-efficacy | Physical Activity and Nutrition Self-efficacy Scale (PANSE). Uses 1–9 scale to rate participant’s level of confidence in completing particular activities that promote weight-loss [61]. |

| Social support | Social support and eating habits (family/friends). This questionnaire asks respondents to rate on a five point scale (1 = none, 5 = very often) the frequency that friends and family have done or said certain things related to the respondents’ efforts to change dietary or exercise habits. The social support for eating survey includes 10 items and two subscales (i.e., encouragement and discouragement) each for friends and family internal consistency coefficients ranging from 0.73 to 0.87 (40-items) [62]. |

| Quality of life | PROMIS. Global assesses 5 domains: physical function, pain, fatigue, emotional distress, and social health. Two dimensions representing physical and mental health underlie the global health items in PROMIS. These global health scales can be used to efficiently summarize physical and mental health in patient-oriented studies [63]. |

| Stress (contextual or indirect) | Crisis in Family Systems (CRISYS). Asks 64 yes/no questions about life events that could lead to stress or difficulty. Psychometric properties have been established in Blacks and lower literacy populations (64-items) [64]. |

| Body image | Body image. Nine-item questionnaire where patients rate satisfaction or dissatisfaction with their body (face; hair; lower torso; mid torso; upper torso; muscle tone, weight, height, overall appearance) [65]. |

| Perceived stress | Perceived stress. Uses 0–4 scales to rate frequency of stressful experiences within the last month (4-items) [51]. |

| Sleep | Sleeping Questionnaire. Four self-reported items documenting what time participants go to sleep on weekdays and weekends. |

| Stress | Superwoman Schema. Assesses emotional suppression as it relates to stress, strength, and health by listing 35 statements about lifestyle and social factors that may relate to weight management. If participants indicate that the statement is true they are asked how often it is true and how much it bothers them (35-items) [66]. |

| Unfair treatment | Acute unfair treatment. The scale was designed to assess acute occurrences of perceived unfair treatment by asking whether participants have experienced 9 life events and what they perceive to be the main reason for these experiences (e.g., race, gender, and age) (10-items) [67]. Everyday unfair treatment. Asked participant the frequency at which they have experienced maltreatment, without reference to racism, discrimination, or prejudice using a 0–4 scale e.g., You have been called names of insult 0 = never…4 = very often (10-items) [68]. |

| Spirituality | Spirituality Scale. Respondents rate the frequency (1 = many times a day …6 = never or almost never) with which they enjoy a variety of spiritual experiences. For example, “I feel God’s presence.” [69]. |

| Active coping | John Henyrism Scale of Active Coping. Designed to capture the tendency to engage in “prolonged, high-effort coping with difficult psycho-social environmental stressors depending on how true or false the statement is for the participant (12-items)” [70]. |

| Adverse childhood experiences | Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Score. 10 yes/no questions about life events that happened in the first 18 years of life used to evaluate traumatic home environments e.g., Did a household member go to prison (10-items) [71]. |

| Mindfulness | Mindfulness Scale. Lists 15 statements describing everyday experiences related to self-awareness, using a 1–6 scale to rate how frequently or infrequently statements occur in participants’ lives e.g., I snack without being aware that I’m eating 1 = almost always; 6 = almost never (15-items) [72]. |

| Motivation | Treatment Self-regulation Questionnaire (TSRQ) for diet and exercise. This measure asks about two types of motivation: autonomous/intrinsic motivation and controlled/extrinsic motivation. Respondents rate their level of agreement to 30 statements (15 diet, 15 exercise) related to the adoption and maintenance of healthy eating and exercise patterns on a 1 (not at all true) to 7 (very true) scale [73]. |

| Food availability | Household food availability. We used a modified version of the home food availability scales developed by Cullen [50] from the Girls’ Health Enrichment Multi-site Studies (GEMS), a multi-site obesity prevention trial targeting African-American girls. Our measure contains 72-items that ask about the availability of a variety of fruits, fruit juices, vegetables, whole grains and dairy in their home in the past week [50]. |

| Walkability | Neighborhood Environment Walkability Scale (NEWS). 98-questions about neighborhood perception, designed to assess features related to physical activity, including residential density, land use mix (including both indices of proximity and accessibility), street connectivity, infrastructure for walking/cycling, neighborhood esthetics, traffic and crime safety, and neighborhood satisfaction (98-items) [74]. |

| Availability of exercise equipment | Home environment. Participants report the availability of various fitness items that they have access to in their home, yard, or apartment complex. These items were drawn from the Neighborhood Quality of Life Study (NQLS, modified version) Home environment section. (20 items) (84). [75]. |

| Home environment | Confusion, Hubbub, and Order Scale (CHAOS). Lists 15 statements about the home environment, participants rate on a 4-point scale how closely the statement describes their home environment e.g., Our home is a good place to relax 1 = strongly disagree… 4 = strongly agree (15-items) [76]. |

| Shopping behaviors | Shopping behaviors. This measure asks participants to name the two most common stores where they shop for food and to rate (1 = strongly agree to 5 = strongly disagree) the availability, quality and cost of fruits vegetables, and low-fat items [77]. |

| Food security | US Food Security Survey. This 18-item measure queries about level of food insecurity ranging from high food security (no indication of food access problems or limitation) to very low food security (multiple indications of disrupted eating patterns and reduced food intake) [78]. |

3.4. Intervention components and delivery

3.4.1. Overview

Sessions will be held at community sites near ENHC and TE that provide ample space for physical activity and are open during evenings to accommodate participants’ work hours. Although intervention concepts and activities will be modified to meet the needs of the target population, the core structure of ORBIT will be retained in the Doing Me! intervention. The intervention group will meet twice weekly for 16 weeks. The 90-min meeting will incorporate 45 min of instruction on diet, physical activity, and/or weight loss plus 45 min of physical activity. Evidence from previous randomized weight loss programs has demonstrated that African-American women will attend weekly sessions [37,52–54]. We have anticipated some of the common barriers to attendance, thus we plan to provide additional support for the participants such as childcare, transportation vouchers, and a social worker to identify and inform participants of community resources.

The interactive format of these meetings will include a weekly weigh-in, sharing of successes and challenges in the previous week, and an introduction to a new topic related to the importance of self-monitoring, contingency management, stimulus control, perception of barriers, and cognitive restructuring. Participants will be asked to log their physical activity and dietary intake daily for review at each session. Participants will also be asked to provide feedback on each session (e.g., topics, speakers, format) and at each data collection time point.

3.4.2. Physical activity component

One of the main objectives of the Doing Me! intervention is to promote physical activity among the participants, to change the culture around physical activity, and to increase exposure to physical activity options in their community. Physical activity will be strategically discussed during the educational part of the intervention session, demonstrated with an in-class physical activity, and then reinforced with outside activities that can be embedded into their personal schedules. The goal is to find a sustainable way to work toward achieving physical activity targets and the overall weight loss goal of losing 5–10% of initial body weight.

An African-American master’s level exercise physiologist will work with the participants in the initial sessions to set goals and meet daily physical activity targets. This will include teaching participants to find their pulses and identify their target heart rate to distinguish exercise intensity (Table 1). Thus the instructor can discuss specific intensity/MET values of activities that are moderate versus vigorous, and these intensities can potentially be used to achieve weight loss goals. The hands-on physical activity component will include a 5-minute warm-up, 30 min of aerobic activity such as dancing or walking, and a 5-minute cool down. In addition to the hour per week that the participants will engage in physical activity as a group, they will also be encouraged to be physically active between sessions. We will discuss ways to increase daily lifestyle activity by using stairs, walking, and doing household activities at higher intensities. Participants will be given a pedometer to measure their steps and encouraged to reach 10,000 steps daily.

Table 1.

Doing Me! Intervention topics, core elements, and behavior strategy objectives.

| Session | Topic | Core elements | Objectives |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Introduction | Recognize how to choose proper shoes and attire that should be worn while exercising. | |

| 2 | Tools for effective weight loss and fad diets | Self-monitoring | Demonstrate effective self-monitoring tools. Identify foods that are calorie dense. Identify foods that are filling but lower in calories. Monitor satiety levels. Explain calorie consumption and expenditure for weight loss. Explain why a pedometer is a useful tool for monitoring physical activity. |

| 3 | Physical activity: what’s enough? | Motivation, culture | Describe physical activity’s role in weight loss and management. Distinguish between lifestyle activities and exercise. Distinguish between exercise frequency and duration. Practice finding their pulse and identify their target heart rate. |

| 4 | Goal setting/check-in/rate your diet and exercise patterns | Motivation, culture | Compose realistic weight-loss and nutrition goals. |

| 5 | MyPlate | Self-monitoring, labeling, food preparation, MyPlate, food groups | Compare the portion sizes of each food group on the plate to what they typically eat. Describe how MyPlate can help make healthy food choices. Compose a meal using an appropriate portion size for each food group. |

| 6 | Food labels and portion size | Shopping, labeling | Learn how to read a food label for macronutrients. Learn what an appropriate portion size is and why portion size matters. |

| 7 | Portion control/satiety | Self-monitoring, labeling, food preparation, My Plate, food groups | Identify methods/tools for measuring/estimating portions. |

| 8 | Meal planning using MyPlate | Food preparation, calorie intake, labeling, MyPlate, culture | Planning a well-balanced meal for self, family, and holidays. |

| 9 | Grocery store tour | Shopping, labeling | Find healthy and affordable foods in each of the food groups. Use the MyPlate, food groups & portions and nutrition facts labels, ingredient list, and unit pricing to compare items at the supermarket. |

| 10 | Setting priorities/readiness to change/sleepa | Motivation, culture | Identify effective stress management techniques. Describe the relationship between sleep and weight loss/gain. |

| 11 | Extreme meal make over (Lab)a Healthy substitutes | Shopping, cooking, calorie intake, culture | Learn how to make a favorite meal healthier |

| 12 | Haira | Motivation, culture | Identify ways to facilitate physical activity while considering hair maintenance. |

| 13 | Cancer | Self-monitoring | Identify cancer screenings and screening frequency. Review screening resources for underinsured and low-income women. |

| 14 | Coping with adverse childhood trauma/coping in crisis/dealing with discriminationa stress management | Self-monitoring, motivation, culture | Use different stress management activities to assist with weight loss. Stress management using meditation and/or spirituality. Deal with emotional issues which trigger old behavior problems. |

| 15 | Eating away from home or fast food | Self-monitoring, shopping, calorie intake, labeling | Develop strategies to choose healthier options when given examples of food from fast food restaurants. Identify four key words to help choose which food item is healthier to consume based off of how it was prepared. Recognize and recall situations where extras added to a meal will increase calories, fat, and sodium. |

| 16 | Graduation | Shopping, cooking, calorie intake, culture | Observe cooking demonstration. |

Sessions that were added after reviewing data collected from previous qualitative studies conducted in Englewood, Chicago.

In developing the intervention, we addressed support for diet and physical activity changes [55], individual/community barriers, and strategies to enhance motivation [56] and regular physical activity [55,56]. As appropriate, group sessions will focus on acknowledging recent success and anticipating potential barriers. Interventionists will be trained to guide participants in setting appropriate and realistic goals level.

3.4.3. Diet activity component

We plan to take a stepped approach to encourage participants to decrease their caloric intake. Participants will be informed of the caloric value of a pound and the Goldberg equation. They will also be instructed on how to make dietary changes to create a caloric deficit of 500 to 1000 per day with the goal of losing 1–2 lb per week. These concepts will be the focus of sessions 2, 4, and 8 in Table 1. In addition to calorie restriction, the intervention will promote participants adopting an overall healthy diet by limiting dietary fat consumption to 20% of total calories, increasing fruit and vegetable consumption to 7 daily serving, and increasing fiber intake to 25 g per day. In addition to nutritional facts, we will discuss strategies for healthy and low-calorie grocery shopping, meal preparation, and eating away from home (See Table 2). The main objective will be for the participants to adopt healthier dietary behaviors that can be sustained in a variety of social contexts.

3.4.4. Behavior change strategies

The behavioral component of Doing Me! is designed to promote successful weight loss and management for African-American women by focusing on social and contextual factors that impact weight management. The curriculum will focus on addressing themes previously identified as important weight management factors in African-American woman, such as body image, appearance, self-esteem, cost, generational food preferences, spiritual beliefs, coping, trauma, and stress. Table 1 includes a description of intervention topics, behavior change strategies, and core elements.

3.4.5. Data-collection and intervention staff and training

Previous studies stress the importance of having a culturally competent staff in weight loss interventions with African-American women [8]. In addition to the PI (Odoms-Young), efforts will be made to ensure that the Doing Me! research team includes African-American intervention staff with diverse backgrounds, including a master’s level coordinator, social workers, graduate students, and trained peers from the community. Interventionists will be required to have a Master’s Degree in Nutrition/Dietetics, Kinesiology, Public Health, or Psychology. Intervention training will take place over two weeks and will cover the following components: 1) reading materials related to successful weight loss and specifically weight loss interventions in African-American women; 2) an overview of the intervention objectives; 3) a review of the curriculum; 4) mock classes; and 5) cultural competence training. Interventionists will receive weekly supervision by the PI.

3.4.6. Quality control

The most important quality control measure for the intervention will be high quality training of the intervention staff. Prior to starting the intervention, staff will be required to attend training and to demonstrate the ability to facilitate intervention sessions. Once the intervention has begun, quality will be monitored via weekly meetings and random observations by study investigators.

3.5. Outcomes, measures and randomization

3.5.1. BMI, waist circumference, and blood pressure

Weight will be measured using a digital scale, with participants wearing light clothes and no shoes, and height will be measured using a stadiometer. These two measures will be used to compute BMI as weight (kg)/height (m)2. Two measurements for height and weight will be taken. If there is a discrepancy of more than 0.5 cm for height or 0.2 kg for weight between the first and second measurements, a third measurement is taken. The mean of the two most closely aligned measurements is used for analyses.

Waist circumference will also be measured, given its value in predicting chronic health disease risk [57]. Participants will stand without outer garments and with empty pockets. The waist will be measured at the level midway between the lower rib margin and the iliac crest, with the participant breathing out gently. Two measurements will be taken. If there is a discrepancy of more than 1 cm, a third measurement will be taken. The mean of the two measurements most closely aligned will be used for analyses. To explore the effects of weight loss on blood pressure, staff will measure diastolic and systolic blood pressure using a standard protocol.

3.5.2. Secondary outcomes

3.5.2.1. Energy balance variables

Dietary intake will be assessed using 24-hour recalls, which are viewed as the gold standard [58]. Three (2 weekdays and 1 weekend day) 24-hour dietary recalls will be conducted at each data collection period. The aggregated 24-hour recall data will provide information regarding baseline nutrient intake, changes in intake at follow-up and the contribution of selected foods to specific nutrient intake. Dietary recalls will be collected using the five-pass method and entered into the Nutrition Data System for Research (NDSR). In addition, participants will be asked to estimate how often they eat fruits, vegetables, and fast food.

3.5.2.2. Physical activity assessment

We will use accelerometers to assess energy expenditure. The limitations of self-reported physical activity are well established [59]. Therefore, we will use the ActiGraph GT3X activity monitor to obtain an objective measure of physical activity (ActiGraph, LLC, Pensacola, FL). We will request that the participants to wear the pedometers for a period of seven days at each assessment time point. The ActiGraph is a small, lightweight (3.8 × 3.7 × 1.8 cm, 27 g) triaxial accelerometer designed to detect normal body motion and filter out motion from other sources [49]. To capture patterns, physical activity will be assessed using the Godin Leisure-time Questionnaire [60]. The Godin Leisure-time Questionnaire participants will be asked to report their frequency and duration of strenuous, moderate and mild (minimal effort) exercise over time.

3.6. Exploratory variables

We selected a number of measures to conduct exploratory analyses of mediators and moderators of weight loss in African-American women. Because little is known about the impact of interpersonal and community-level factors on weight loss efforts, particularly in low-income areas, findings from the literature were integrated with community input to help us identify potential barriers to successful weight loss. Many measures were selected based on previous research examining potential factors that could support or impede the weight loss efforts in African-American woman (e.g., food availability [16,61], body image [17,62], unfair treatment [23,63]). Other measures were added after reviewing data collected from our previous studies exploring weight-related behaviors in African-American communities, such as the Neighborhood Environment Walkability Scale to understand community barriers to physical activity [46–49,64,65]. A complete list of measures with descriptions can be found in Table 2.

3.7. Randomization

Approximately one week before the start of the intervention, all participants who have completed baseline interviews will be called to confirm that they are still able to participate in the study. All participants will then be randomized using allocation assignments generated in SAS v 9.4 by the data analyst, who will have no contact with participants. Enrollment will continue until the target sample is recruited, then the participants will be randomized and the intervention will start at once for all participants. Each Doing Me! intervention class will accommodate approximately 30 participants. We will enroll 60 women who will be randomly assigned to intervention or to the waitlist control.

3.8. Data management and analytic plan

3.8.1. Data management

All questionnaires and anthropometric measures will be collected on scannable paper forms created with the Autonomy TeleForm program. After scanning and verification in TeleForm, data will be exported to a Microsoft Access database and finally to a SAS dataset for analysis. The data analyst will conduct standard checks for missing and out-of-range responses.

3.8.2. Data analysis

Prior to comparing outcomes between Doing Me! and the waitlist control, we will compute descriptive statistics by group for all variables collected at baseline, including demographics, BMI, weight, diet, physical activity, self-efficacy, social support, motivation, and barriers. We will compute means and standard deviations for continuous variables, medians and interquartile ranges for ordinal variables, and percentages by category for categorical variables. Women in the two groups will be compared based on two-sample t-tests for continuous variables and chi-square tests for dichotomous or polychotomous variables. We will also examine the distributions of variables in each group and use rank tests or transform variables to improve normality if appropriate.

Analyses to assess acceptability/feasibility of the intervention will be based primarily on counts and proportions (e.g., the proportion of women in Doing Me! who attend sessions, the average number of sessions attended, and the proportion of women in each group completing data collection at 16 weeks). Descriptive statistics will be completed on survey measures administered at each data collection period to assess intervention satisfaction/acceptability. Semi-structured interviews will also be conducted at the end of the intervention with participants to better understand acceptability. We will examine the preliminary efficacy of the intervention by examining differences between groups in weight and BMI change at 16 weeks. However, this is a pilot study, and it is not designed to rigorously test the efficacy of the intervention.

The explanatory factor in the statistical model is intervention group (Doing Me! vs. control). For analyzing BMI, linear mixed models (e.g., SAS PROC MIXED) will test for a difference between groups in change in BMI (i.e., group × time interaction). To inspect for differential dropout we will compare baseline characteristics between those who complete the intervention and those who do not both overall and by treatment group. We will also examine whether conclusions are altered by inclusion of baseline covariates that differed between groups.

In addition to the primary analyses, we will conduct exploratory analyses to investigate whether relationships between intervention condition and BMI outcomes are moderated by variables such as age, comorbidities, and the various psychosocial measures. Moderator (interaction) effects on the relationship between group and mediating variables will be examined by including moderator terms (e.g., group × age, group × comorbidity, group × stress, group × social support) in linear regression models for the mediating variables.

4. Discussion

Novel weight loss interventions for African-American women are needed to help reduce racial disparities in obesity and related health outcomes. African-American women lose less weight in traditional behavioral weight loss programs compared with white women [9,10]. It has been hypothesized that African-American women lose less weight because most interventions focus primarily on lifestyle factors and do not address the social and cultural contexts that may impede successful weight loss in this high-risk group [12,26,27]. Several researchers have emphasized the importance of using community-engaged approaches to ensure that behavioral weight loss interventions are responsive to the needs of African-American women (particularly low-income African-American women), yet very few weight loss programs have been developed in collaboration with community residents and representatives [10,12,22]. Findings from a review by Kong et al. in 2014 suggests that involving community collaborators in the development of weight loss interventions with African-American women may be particularly important because it may lead to more relevant content, help address aspects that are meaningful to the target audience, and contribute to a greater understanding of the heterogeneity that exists within racial/ethnic groups [8]. While incorporation of socio-cultural strategies have been reported to improve weight outcome in African-Americans (e.g. such as the consideration of traditional foods, faith based programs, social support networks, food insecurity, and food access) [8,12,31] the addition of the CBPR methodology and involvement of community stakeholders in the development of the intervention may further improve weight loss outcomes [12,66].

Despite its innovative design, Doing Me! has some limitations. Doing Me! is a pilot study with a relatively small sample (n = 60), which will limit power to test for mediation, and moderation effects of our exploratory variables on weight change. Still, we will be able to evaluate the feasibility and acceptability of Doing Me! with the goal of subsequently testing its efficacy in a larger trial. Additionally, given that our sample will be comprised of urban low-income African-American women, Doing Me! may have limited generalizability to African-American women overall. Nevertheless, approximately 28% of African-Americans live in poverty (three times that of the rate for white populations) and poverty may be particularly concentrated in urban areas. Consequently if effective, Doing Me! could potentially be implemented in populations of African-American women with similar social and demographic characteristics. Finally, the wait-list control design of Doing Me! may overestimate the treatment effect of the intervention. Although participants randomized to our wait list control group will receive weekly newsletters, evidence suggests that these participants are more likely to “wait” to engage in behavior change until they receive the intervention compared with participants in a traditional randomized control trial who never receive the intervention. The benefit of this type of design, however, is that it allows all randomized participants to receive the most intensive intervention by the end of the trial. Given our focus on community-level health, we felt it was best to ensure that all participants received treatment. Despite these limitations, it is our hope that Doing Me! will result in greater weight losses than traditional programs to help inform larger randomized controlled trials to reduce health disparities and to improve the health of low-income African-American women.

Acknowledgments

Doing Me! was funded by the American Cancer Society (ACS) Illinois (grant no. 217030, PI: Odoms-Young). Additional support for this project was provided by National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R25CA057699.

References

- 1.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of childhood and adult obesity in the United States, 2011–2012. JAMA. 2014 Feb 26;311(8):806–814. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jakicic JM, Marcus BH, Lang W, Janney C. Effect of exercise on 24-month weight loss maintenance in overweight women. Arch Intern Med. 2008 Jul 28;168(14):1550, 9. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.14.1550. discussion 1559–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Unick JL, Jakicic JM, Marcus BH. Contribution of behavior intervention components to 24-month weight loss. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2010 Apr;42(4):745–753. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181bd1a57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Franz MJ, VanWormer JJ, Crain AL, Boucher JL, Histon T, Caplan W, et al. Weight-loss outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of weight-loss clinical trials with a minimum 1-year follow-up. J Am Diet Assoc. 2007 Oct;107(10):1755–1767. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2007.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Panel, NHLBI Obesity Education Initiative Expert. Clinical Guidelines on the Identification, Evaluation, and Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Adults. 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Managing Overweight and Obesity in Adults: Systematic Evidence Review from The Obesity Expert Panel, 2013. US Department of Health and Human Services: National Institutes of Health; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wingo BC, Carson TL, Ard J. Differences in weight loss and health outcomes among African Americans and whites in multicentre trials. Obes Rev. 2014 Oct;15(Suppl 4):46–61. doi: 10.1111/obr.12212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kong A, Tussing-Humphreys LM, Odoms-Young AM, Stolley MR, Fitzgibbon ML. Systematic review of behavioural interventions with culturally adapted strategies to improve diet and weight outcomes in African American women. Obes Rev. 2014 Oct;15(Suppl 4):62–92. doi: 10.1111/obr.12203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.West DS, Elaine Prewitt T, Bursac Z, Felix HC. Weight loss of black, white, and Hispanic men and women in the Diabetes Prevention Program. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008 Jun;16(6):1413–1420. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Samuel-Hodge CD, Johnson CM, Braxton DF, Lackey M. Effectiveness of Diabetes Prevention Program translations among African Americans. Obes Rev. 2014 Oct;15(Suppl 4):107–124. doi: 10.1111/obr.12211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kumanyika S, Taylor WC, Grier SA, Lassiter V, Lancaster KJ, Morssink CB, et al. Community energy balance: a framework for contextualizing cultural influences on high risk of obesity in ethnic minority populations. Prev Med. 2012 Nov;55(5):371–381. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2012.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fitzgibbon ML, Tussing-Humphreys LM, Porter JS, Martin IK, Odoms-Young A, Sharp LK. Weight loss and African-American women: a systematic review of the behavioural weight loss intervention literature. Obes Rev. 2012 Mar;13(3):193–213. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2011.00945.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Agyemang P, Powell-Wiley TM. Obesity and Black women: special considerations related to genesis and therapeutic approaches. Curr Cardiovasc Risk Rep. 2013 Oct 1;7(5):378–386. doi: 10.1007/s12170-013-0328-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cozier YC, Yu J, Coogan PF, Bethea TN, Rosenberg L, Palmer JR. Racism, segregation, and risk of obesity in the Black women’s health study. Am J Epidemiol. 2014 Feb 27; doi: 10.1093/aje/kwu004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baruth M, Sharpe PA, Parra-Medina D, Wilcox S. Perceived barriers to exercise and healthy eating among women from disadvantaged neighborhoods: results from a focus groups assessment. Women Health. 2014 Mar;11 doi: 10.1080/03630242.2014.896443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gustafson AA, Sharkey J, Samuel-Hodge CD, Jones-Smith JC, Cai J, Ammerman AS. Food store environment modifies intervention effect on fruit and vegetable intake among low-income women in North Carolina. J Nutr Metab. 2012;2012:932653. doi: 10.1155/2012/932653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Robinson SA, Webb JB, Butler-Ajibade PT. Body image and modifiable weight control behaviors among black females: a review of the literature. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2012 Feb;20(2):241–252. doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hillier A, Tappe K, Cannuscio C, Karpyn A, Glanz K. In an urban neighborhood, who is physically active and where? Women Health. 2014;54(3):194–211. doi: 10.1080/03630242.2014.883659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.DeLany JP, Jakicic JM, Lowery JB, Hames KC, Kelley DE, Goodpaster BH. African American women exhibit similar adherence to intervention but lose less weight due to lower energy requirements. Int J Obes (Lond) 2014 Sep;38(9):1147–1152. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2013.240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bidulescu A, Choudhry S, Musani SK, Buxbaum SG, Liu J, Rotimi CN, et al. Associations of adiponectin with individual European ancestry in African Americans: the Jackson Heart Study. Front Genet. 2014 Feb 10;5:22. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2014.00022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mezick EJ, Matthews KA, Hall M, Strollo PJ, Jr, Buysse DJ, Kamarck TW, et al. Influence of race and socioeconomic status on sleep: Pittsburgh Sleep SCORE project. Psychosom Med. 2008 May;70(4):410–416. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31816fdf21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Walker RE, Gordon M. The use of lifestyle and behavioral modification approaches in obesity interventions for Black women: a literature review. Health Educ Behav. 2013 Jul;2 doi: 10.1177/1090198113492768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cox TL, Krukowski R, Love SJ, Eddings K, DiCarlo M, Chang JY, et al. Stress management-augmented behavioral weight loss intervention for African American women: a pilot, randomized controlled trial. Health Educ Behav. 2013 Feb;40(1):78–87. doi: 10.1177/1090198112439411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Coogan PE, Wise LA, Cozier YC, Palmer JR, Rosenberg L. Lifecourse educational status in relation to weight gain in African American women. Ethn Dis. 2012 Spring;22(2):198–206. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ludwig J, Sanbonmatsu L, Gennetian L, Adam E, Duncan GJ, Katz LF, et al. Neighborhoods, obesity, and diabetes—a randomized social experiment. N Engl J Med. 2011 Oct 20;365(16):1509–1519. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1103216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Casagrande SS, Whitt-Glover MC, Lancaster KJ, Odoms-Young AM, Gary TL. Built environment and health behaviors among African Americans: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2009;36(2):174–181. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.09.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hollis JF, Gullion CM, Stevens VJ, Brantley PJ, Appel LJ, Ard JD, et al. Weight loss during the intensive intervention phase of the weight-loss maintenance trial. Am J Prev Med. 2008;35(2):118–126. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kelsey KS, DeVellis BM, Gizlice Z, Ries A, Barnes K, Campbell MK. Obesity, hope, and health: findings from the HOPE Works community survey. J Community Health. 2011 Dec;36(6):919–924. doi: 10.1007/s10900-011-9390-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Israel BA, Eng E, Schulz A, Parker EA. Introduction to methods for CBPR for health, Methods in community-based Participatory. Research for Health. 2005:3–26. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Viswanathan M, Ammerman A, Eng E, Garlehner G, Lohr KN, Griffith D, et al. Community-based Participatory Research: Assessing the Evidence: Summary. 2004 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zoellner J, Connell C, Madson MB, Thomson JL, Landry AS, Fontenot Molaison E, et al. HUB city steps: a 6-month lifestyle intervention improves blood pressure among a primarily African-American community. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2014 Apr;114(4):603–612. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2013.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zoellner J, Hill JL, Grier K, Chau C, Kopec D, Price B, et al. Randomized controlled trial targeting obesity-related behaviors: better together healthy Caswell County. Prev Chronic Dis. 2013 Jun 13;10:E96. doi: 10.5888/pcd10.120296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zoellner JM, Connell CC, Madson MB, Wang B, Reed VB, Molaison EF, et al. H.U.B. city steps: methods and early findings from a community-based participatory research trial to reduce blood pressure among African Americans. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2011 Jun 10;8:59. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-8-59. 5868-8-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fitzgibbon ML, Stolley MR, Schiffer L, Sharp LK, Singh V, Dyer A. Obesity reduction black intervention trial (ORBIT): 18-month results. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2010 Dec;18(12):2317–2325. doi: 10.1038/oby.2010.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stolley MR, Fitzgibbon ML, Schiffer L, Sharp LK, Singh V, Van Horn L, et al. Obesity reduction black intervention trial (ORBIT): six-month results. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2009 Jan;17(1):100–106. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fitzgibbon ML, Stolley M, Schiffer L, Sharp L, Singh V, Van Horn L, et al. Obesity Reduction Black Intervention Trial (ORBIT): design and baseline characteristics. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2008 Sep;17(7):1099–1110. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2007.0614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zenk SN, Odoms-Young AM, Dallas C, Hardy E, Watkins A, Hoskins-Wroten J, et al. “You have to hunt for the fruits, the vegetables”: environmental barriers and adaptive strategies to acquire food in a low-income African American neighborhood. Health Educ Behav. 2011 Jun;38(3):282–292. doi: 10.1177/1090198110372877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zenk SN, Schulz AJ, Odoms-Young AM. How neighborhood environments contribute to obesity. Am J Nurs. 2009 Jul;109(7):61–64. doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000357175.86507.c8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.DiSantis KI, Grier SA, Odoms-Young A, Baskin ML, Carter-Edwards L, Young DR, et al. What “price” means when buying food: insights from a multisite qualitative study with black Americans. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(3):516–522. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Odoms-Young A, Zenk S, Holland L, Watkins A, Hoskins-Wroten J, Oji-Njideka N, et al. Family Food Access Report: “When We Have Better, We Can Do Better”. University of Illinois at Chicago and Chicago Department of Public Health-Englewood Neighborhood Health Center; Chicago: Dec, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 41.City of Chicago Data Portal. Public Health Statistics — Selected Public Health Indicators. Chicago Community Area; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Harris KJ, Ahluwalia JS, Catley D, Okuyemi KS, Mayo MS, Resnicow K. Successful recruitment of minorities into clinical trials: the Kick It at Swope project. Nicotine Tob Res. 2003 Aug;5(4):575–584. doi: 10.1080/1462220031000118540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stolley MR, Fitzgibbon ML, Dyer A, Horn LV, KauferChristoffel K, Schiffer L. Hip-Hop to Health Jr., an obesity prevention program for minority preschool children: baseline characteristics of participants. Prev Med. 2003;36(3):320–329. doi: 10.1016/s0091-7435(02)00068-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Whitehorse LE, Manzano R, Baezconde-Garbanati LA, Hahn G. Culturally tailoring a physical activity program for Hispanic women: recruitment successes of La Vida Buena’s salsa aerobics. J Health Educ. 1999;30(Suppl 2):S18–S24. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Janssen I, Katzmarzyk PT, Ross R. Waist circumference and not body mass index explains obesity-related health risk. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004 Mar;79(3):379–384. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/79.3.379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thompson FE, Byers T. Dietary assessment resource manual. J Nutr. 1994 Nov;124(11 Suppl):2245S–2317S. doi: 10.1093/jn/124.suppl_11.2245s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sallis JF, Pinski RB, Grossman RM, Patterson TL, Nader PR. The development of self-efficacy scales for health related diet and exercise behaviors. Health Educ Res. 1988;3(3):283–292. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sasaki JE, John D, Freedson PS. Validation and comparison of ActiGraph activity monitors. J Sci Med Sport. 2011;14(5):411–416. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2011.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Godin G, Shephard R. Godin leisure-time exercise questionnaire. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1997;29(6 s):S36. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cullen KW, Baranowski T, Klesges LM, Watson K, Sherwood NE, Story M, et al. Anthropometric, parental, and psychosocial correlates of dietary intake of African-American girls. Obes Res. 2004;12(S9):20S–31S. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983:385–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Williams DR. Racial/ethnic variations in women’s health: the social embeddedness of health. Am J Public Health. 2002 Apr;92(4):588–597. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.4.588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Boynton-Jarrett R, Rosenberg L, Palmer JR, Boggs DA, Wise LA. Child and adolescent abuse in relation to obesity in adulthood: the Black Women’s Health Study. Pediatrics. 2012 Aug;130(2):245–253. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-1554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kumanyika SK, Whitt-Glover MC, Gary TL, Prewitt TE, Odoms-Young AM, Banks-Wallace J, et al. Expanding the obesity research paradigm to reach African American communities. Prev Chronic Dis. 2007 Oct;4(4):A112. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Israel BA, Eng E, Schulz AJ, Parker EA. Introduction to methods in community-based participatory research for health, Methods in Community-based Participatory Research for Health. 2005:3–26. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cunningham JA, Kypri K, McCambridge J. Exploratory randomized controlled trial evaluating the impact of a waiting list control design. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2013 Dec 6;13:150. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-13-150. 2288-13-150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chin MH, Walters AE, Cook SC, Huang ES. Interventions to reduce racial and ethnic disparities in health care. Med Care Res Rev. 2007 Oct;64(5 Suppl):7S–28S. doi: 10.1177/1077558707305413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gehlert S, Coleman R. Using community-based participatory research to ameliorate cancer disparities. Health Soc Work. 2010 Nov;35(4):302–309. doi: 10.1093/hsw/35.4.302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pickering TG, Hall JE, Appel LJ, Falkner BE, Graves J, Hill MN, et al. Recommendations for blood pressure measurement in humans and experimental animals: part 1: blood pressure measurement in humans: a statement for professionals from the Subcommittee of Professional and Public Education of the American Heart Association Council on High Blood Pressure Research. Hypertension. 2005 Jan;45(1):142–161. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000150859.47929.8e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Murphy PW, Davis TC, Long SW, Jackson RH, Decker BC. Rapid estimate of adult literacy in medicine (REALM): a quick reading test for patients. J Read. 1993:124–130. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Latimer L, Walker LO, Kim S, Pasch KE, Sterling BS. Self-efficacy scale for weight loss among multi-ethnic women of lower income: a psychometric evaluation. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2011;43(4):279–283. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2010.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sallis JF, Grossman RM, Pinski RB, Patterson TL, Nader PR. The development of scales to measure social support for diet and exercise behaviors. Prev Med. 1987;16(6):825–836. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(87)90022-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cella D, Riley W, Stone A, Rothrock N, Reeve B, Yount S, et al. The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) developed and tested its first wave of adult self-reported health outcome item banks: 2005–2008. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63(11):1179–1194. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shalowitz MU, Berry CA, Rasinski KA, Dannhausen-Brun CA. A new measure of contemporary life stress: development, validation, and reliability of the CRISYS. Health Serv Res. 1998 Dec;33(5 Pt 1):1381–1402. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Thompson MA, Gray JJ. Development and validation of a new body-image assessment scale. J Pers Assess. 1995;64(2):258–269. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6402_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Woods-Giscombe CL. Superwoman schema: African American women’s views on stress, strength, and health. Qual Health Res. 2010 May;20(5):668–683. doi: 10.1177/1049732310361892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kessler RC, Mickelson KD, Williams DR. The prevalence, distribution, and mental health correlates of perceived discrimination in the United States. J Health Soc Behav. 1999:208–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Williams DR, Yan Y, Jackson JS, Anderson NB. Racial differences in physical and mental health: socio-economic status, stress and discrimination. J Health Psychol. 1997 Jul;2(3):335–351. doi: 10.1177/135910539700200305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Taylor RJ, Chatters LM. Church-based informal support among elderly blacks. Gerontologist. 1986 Dec;26(6):637–642. doi: 10.1093/geront/26.6.637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.James SA, Strogatz DS, Wing SB, Ramsey DL. Socioeconomic status, John Henryism, and hypertension in blacks and whites. Am J Epidemiol. 1987 Oct;126(4):664–673. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Dube SR, Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Chapman DP, Williamson DF, Giles WH. Childhood abuse, household dysfunction, and the risk of attempted suicide throughout the life span: findings from the Adverse Childhood Experiences Study. JAMA. 2001;286(24):3089–3096. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.24.3089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Brown KW, Ryan RM. The benefits of being present: mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2003;84(4):822. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.84.4.822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Levesque CS, Williams GC, Elliot D, Pickering MA, Bodenhamer B, Finley PJ. Validating the theoretical structure of the Treatment Self-Regulation Questionnaire (TSRQ) across three different health behaviors. Health Educ Res. 2007 Oct;22(5):691–702. doi: 10.1093/her/cyl148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Saelens BE, Sallis JF, Black JB, Chen D. Neighborhood-based differences in physical activity: an environment scale evaluation. Am J Public Health. 2003 Sep;93(9):1552–1558. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.9.1552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Frank LD, Sallis JF, Saelens BE, Leary L, Cain K, Conway TL, et al. The development of a walkability index: application to the Neighborhood Quality of Life Study. Br J Sports Med. 2010 Oct;44(13):924–933. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2009.058701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Matheny AP, Jr, Wachs TD, Ludwig JL, Phillips K. Bringing order out of chaos: psychometric characteristics of the confusion, hubbub, and order scale. J Appl Dev Psychol. 1995;16(3):429–444. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ayala GX, Mueller K, Lopez-Madurga E, Campbell NR, Elder JP. Restaurant and food shopping selections among Latino women in Southern California. J Am Diet Assoc. 2005;105(1):38–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2004.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bickel G, Nord M, Price C, Hamilton W, Cook J. Guide to Measuring Household Food Security. Department of Agriculture Food and Nutrition Service; Alexandria: 2000. [Google Scholar]