Abstract

Background

The 2014 European Union (EU) Tobacco Products Directive (TPD) was negotiated in a changed policy context, following adoption of the EU's ‘Smart Regulation’ agenda, which transnational tobacco companies (TTCs) anticipated would increase their influence on health policy, and the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC), which sought to reduce it. This study aims to explore the scale and nature of the TTCs' lobby against the EU TPD and evaluate how these developments have affected their ability to exert influence.

Methods

Analysis of 581 documents obtained through freedom of information requests, 28 leaked Philip Morris International (PMI) documents, 17 TTC documents from the Legacy Library, web content via Google alerts and searches of the EU institutions' websites, plus four stakeholder interviews.

Results

The lobby was massive. PMI alone employed over 160 lobbyists. Strategies mainly used third parties. Efforts to 'Push' (amend) or 'Delay' the proposal and block 'extreme policy options' were partially successful, with plain packaging and point of sales display ban removed during the 3-year delay in the Commission. The Smart Regulation mechanism contributed to changes and delays, facilitating meetings between TTC representatives (including ex-Commission employees) and senior Commission staff. Contrary to Article 5.3, these meetings were not disclosed.

Conclusions

During the legislative process, Article 5.3 was not consistently applied by non-health Directorates of the European Commission, while the tools of the Smart Regulation appear to have facilitated TTC access to, and influence on, the 2014 TPD. The use of third parties undermines Article 5.3.

Keywords: Public policy, Tobacco industry, Tobacco industry documents

Introduction

Tobacco is Europe's largest preventable cause of death, claiming nearly 700 000 lives in the European Union (EU) annually.1 Although the EU's public health legislative powers are limited,2 the launch of the 1985 ‘Europe Against Cancer’ programme3 prompted a range of tobacco control measures,4 including the 2001 Tobacco Products Directive (TPD) (2001/37/EC) which regulates the manufacture, sale and presentation of tobacco products. In 2009, the European Commission (‘the Commission’) began revising this Directive in light of new market and scientific developments and the WHO's Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC).5 The process took over 5 years, with the new Directive finally adopted in April 2014. The Directive, which includes an increase in the size of graphic health warnings, a ban on characterising flavours, restrictions on the size and shape of cigarette packs, and the regulation of Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems (ENDS) (table 1), must be transposed into national law by 2016.6

Table 1.

Textual changes to the 2014 TPD

| Key provisions | Commission proposal 19/12/2012 |

Council common approach 21/06/2013 |

Parliamentary health committee approved text 10/07/2013 |

Parliamentary plenary approved text 8/10/2013 |

Trilogue agreement (between commission, council and parliament) 18/12/2013 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Size and position of health warnings | 75% front, back and top MS discretion |

65% front, back and top MS discretion |

75% front, back and top MS discretion |

65% front, back and top MS discretion |

65% front, back and top MS discretion |

| Ban on ‘characterising flavours’ | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes, menthol 5 years derogation | Yes, menthol 4 years derogation |

| Slim cigarette ban | Yes | No | Yes | No | No |

| Ban on 10 cigarette pack | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Cross border distance sales | Notification, mandatory age verification | Prohibit or notification MS discretion |

Prohibit | Prohibit | Notification MS discretion |

| Traceability and security features | Track and trace to extend to the whole supply chain | Track and trace to extend to the whole supply chain | Track and trace to extend to the whole supply chain. No tobacco industry solutions | Track and trace to extend to the whole supply chain. No tobacco industry solutions | Track and trace system for the legal supply chain |

| Snus sales ban | Maintained | Maintained | Maintained | Maintained | Maintained |

| ENDS regulation | Medicines licence, depending on nicotine concentration | Medicines licence, depending on nicotine concentration | Medicines licence all | No, only if they make health claims | No, only if they make health claims |

MS, Member States.

While these changes represent significant public health advances, the final Directive is weaker than initial drafts7 (table 1). The review process involved controversy, notably the forced resignation of Health Commissioner John Dalli and claims of tobacco industry interference,8–12 with the TPD described as ‘the most lobbied dossier in the history of the EU institutions’.13 Although previous research reveals transnational tobacco companies’ (TTCs) efforts to derail earlier EU tobacco regulation,2 14–16 the policy context has since changed in ways that may mitigate or exacerbate TTCs’ ability to influence EU legislation. On the one hand, FCTC Article 5.3 entered into force in 2005, requiring that ‘in setting and implementing their public health policies with respect to tobacco control, parties shall act to protect these policies from commercial and other vested interests of the tobacco industry’.17 Conversely, regulatory reforms known in the EU as Better or Smart Regulation, and shown to facilitate tobacco industry influence,18 19 were implemented in the mid-2000s.20 Smart Regulation seeks to reduce regulatory burdens and enhance business competitiveness via impact assessment (IA), which attempt to estimate the costs and benefits of policies in monetary terms, and stakeholder consultation in which those affected by the policy are formally consulted early in the policy process. Worryingly, British American Tobacco (BAT), working with a large number of other corporations whose products are potentially damaging to health, was instrumental in promoting Smart Regulation, anticipating it would make it harder to enact public health legislation.21 In line with BAT's predictions, growing evidence suggests that Smart Regulation can19 21 22 and has23 24 favoured corporate interests and might undermine efforts to implement public health policies.19 21 22

We previously demonstrated, using quantitative content analysis, that successive drafts of the TPD shifted towards the tobacco industry's preferred position.7 We explore how the tobacco industry engineered some of these policy changes. We examine the nature and scale of TTCs’ efforts to influence the TPD revision, identifying key entry points used to access and shape the policy process. We also examine whether Smart Regulation enabled corporate influence on the TPD, as those promoting it intended,21 and whether the application of Article 5.3 is adequate to prevent TTC influence on EU tobacco control policymaking.

Methods

We analysed a wide variety of materials. First, we obtained 2007–2014 reports, meeting minutes, and press releases from the Commission (http://ec.europa.eu/health/tobacco/policy/index_en.htm), Council of Ministers (http://www.consilium.europa.eu/homepage) and European Parliament (http://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/news-room/) websites. Second, relevant web content (including press coverage, media releases and, blogs) was identified prospectively through Google alerts established in 2011 on BAT, ‘Philip Morris International’ (PMI), ‘Japan Tobacco International’, ‘Imperial Tobacco’, ‘Swedish Match’, and ‘Tobacco Products Directive’. Third, internal TTC documents were taken from two sources: 28 PMI documents detailing its strategy to influence the TPD, dated 2011–2013 and leaked to health groups in 2013 (‘PMI's documents’), and 17 (of 323 retrieved) documents obtained from the Legacy Tobacco Documents Library (http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/) (‘Legacy documents’) using search terms ‘tobacco products directive’, ‘TPD’, ‘tobacco directive’ and ‘impact assessment’, and document dates 2007–2013.

Finally, to triangulate the industry documents, identify whether actions detailed were carried out and further examine the TTCs’ political activity, we analysed documents, all dated 2010–2013, released under EU Freedom of Information (FOI) legislation (n=581) or given to the authors (n=2) (‘FOI documents’) and undertook four stakeholder interviews. The majority of the FOI documents were released directly to the authors (n=425) or their contacts (n=109) and are previously unpublished, while others (n=47) were available online at http://www.asktheeu.org (see online supplementary appendix 1).

Documents were analysed using a deductive hermeneutic approach,25–27 that is, understanding documents’ content in a wider policy context, while identifying conceptual themes and subthemes (eg, corporate political strategies and tactics) which were repeatedly tested as data collection progressed. Events and meetings, identified from the documents and occurring from 2007 to 2014, were recorded in a timeline to map key developments, identify stakeholders and points of access to EU institutions, and time the Directive's progress through the legislative process. We compared the time the 2014 TPD revision took in each legislative stage, that is, in the Commission, then Parliament and Council, with the original 2001 TPD.

Semistructured interviews were undertaken with staff of the most active Brussels-based tobacco control NGO, the Smoke Free Partnership (SFP) and three Members of European Parliament (MEPs) (Twelve MEPs identified in the European Parliament's TPD ‘procedural file’ as key players28 were invited for interview, but only three accepted). Staff of DG-SANCO, the Commission's department responsible for tobacco control, were also approached but declined. Interviews were professionally transcribed and coded using a thematic approach based on the literature while also allowing for new themes to emerge.29

Results

Tobacco industry strategy

PMI's approach to the 2014 Directive was to either ‘Push’ (ie, amend) or ‘Delay’ the proposal, or block any ‘extreme policy options’ which it identified as standardised packaging, a point of sales display ban and an ingredients ban.30 31 Its strategy detailed actions to be taken at each stage of the legislative process. In the Commission, PMI aimed to “Block DG SANCO's extreme policy options”,30 in Parliament to “Break ENVIs (Health Committee) full control on the dossier”,30 and in the Council to “Create [a] blocking minority to any extreme measures”.30

David versus Goliath

PMI alone employed more than 160 lobbyists and spent €1.25 million on lobbying to subvert the TPD.32 At least seven tobacco industry lobbyists were former EU politicians or civil servants.33 34 By contrast, Brussels-based health advocates had five fulltime equivalent positions working on the TPD, with a slight increase when the proposal was published in December 2012 (personal correspondence, SFP 12 May 2014). Comparing the health to the tobacco lobby, one MEP likened it to a biblical battle: ‘if you see who is fighting on the left hand side and who is fighting on the right hand side…then you get a shock. It is David and Goliath. It's unbelievable’ (interview MEP, January 2014).

Third party mobilisation

PMI's first ‘principle’ for achieving its objective was ‘indirect engagement over direct engagement’,31 describing third party involvement as ‘key to success’.35 PMI sought to use a ‘3rd party coalition’ to garner political support from non-health Commissioners using four frames or ‘platforms’: intellectual property, ingredients, retailers and smokeless tobacco.30 36 PMI named 15 associations and 2 companies as coalition members, including the European Tobacco Growers Association (Unitab), European Federation of Food, Agriculture and Tourism Trade Unions (EFFAT), and the European Federation of Tobacco Processors (FETRATAB) leading on the ingredients’ platform, and the European Association of Tobacco Retailers (CEDT) on the retailers' platform.36

FOI documents and Parliamentary and Commission meeting minutes and reports confirm that 12 of PMI's third party coalition partners (11 associations and 1 private company), were actively involved in lobbying the Commission and Parliament, and mobilising opposition.37–45 For example, CEDT established a European retailers’ TPD Working Party which mobilised member state retail organisations.46 47 In addition, we identified 126 associations and 33 non-TTC companies (17 public relations and law firms) that voiced opposition to the TPD, through industry stakeholder meetings with the Commission,37 48 approaching Commission officials and MEPs with their concerns,49–52 participating in working groups to develop counterstrategies or policy statements,46 53 54 making critical statements in the media,55–58 and signing anti-TPD petitions59 (see online supplementary appendix 2).

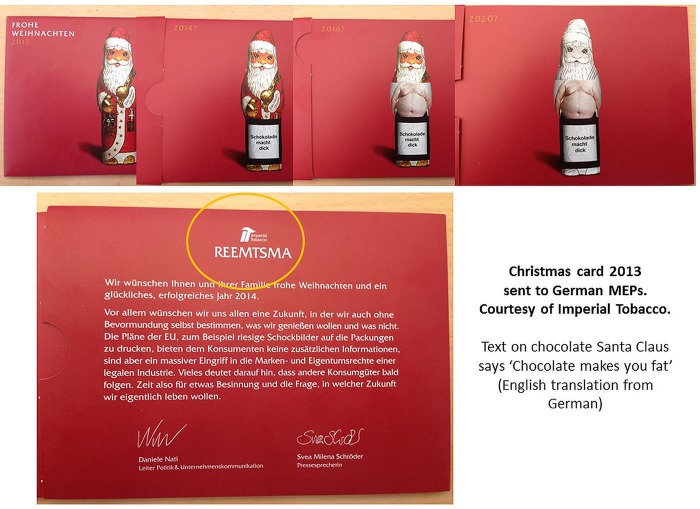

In ongoing work, we have identified 51 of 137 third party associations as having financial links with the tobacco industry. Their interests and actions are consistent with PMI's strategy.36 For example, many (44) were general business associations and FOI documents reveal that PMI and BAT attended meetings organised by Business Europe and the Dutch business association, VNO-NCW, intending to build a Europe-wide business lobbying presence to stress the TPD's ‘spill-over’ effects on other sectors.53 54 This spill-over effect (eg, on food and alcohol industries) was emphasised in TTC lobbying of MEPs (figure 1). Importantly, meeting minutes specify that the business groups would not attend a formal tobacco industry stakeholder meeting hosted by DG-SANCO, to create the perception of autonomy from the tobacco sector.53

Figure 1.

Gifts sent to Members of European Parliament (MEPs) in 2013 to stress the danger of possible ‘spill-over’ effects of Tobacco Products Directive (TPD) measures into the alcohol and food industries.

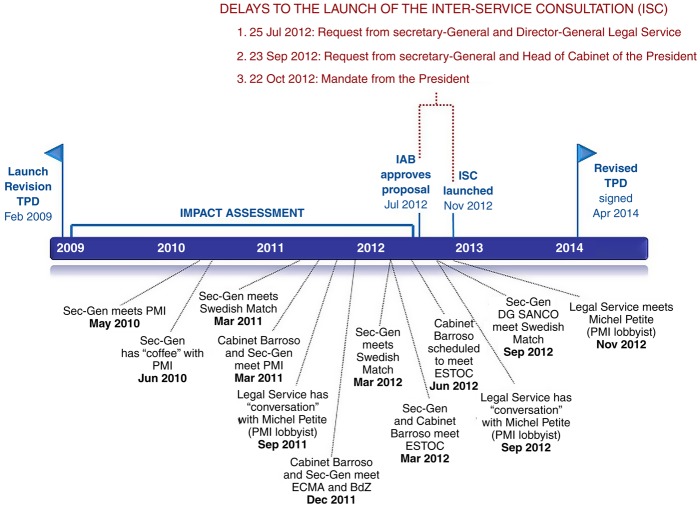

Delays in the commission policy process

The 2014 TPD followed the usual legislative procedure (figure 2). However, a comparison with the 2001 TPD shows that, while each Directive spent an equal amount of time in the codecision stage, the 2014 Directive spent 3 years longer with the Commission.

Figure 2.

Legislative process undertaken to review the Tobacco Products Directive (TPD). Source: summary of data collected from the websites of the European Commission, Parliament and Council, accessed regularly between May 2012 and April 2014.

AGRI, Committee on Agriculture and Rural Development; CoR, Committee of the Regions; EESC, European Economic and Social Committee; ENVI, Committee on the Environment, Public Health and Food Safety; IAB, Impact Assessment Board; IASG, Impact Assessment Steering Group; INTA, Committee on International Trade; IMCO, Committee on Internal Market and Consumer Protection; ITRE, Committee on Industry, Research and Energy; JURI, Committee on Legal Affairs; SCENIHR, Scientific Committee on Emerging and Newly Identified Health Risks.

1Special Eurobarometer 332 (May 2010), Special Eurobarometer 385 (May 2012). 2GHK Consulting, A Study on Liability and the Health Costs of Smoking, Final Report (December 2009), Rand Europe, Assessing the impacts of Revising the Tobacco Products Directive. Study to support a DG SANCO Impact Assessment, Final Report (September 2010), RAND Europe, Availability, accessibility, usage and regulatory environment for novel and emerging tobacco, nicotine or related products (December 2012), Matrix Insight, Economic analysis of the EU market of tobacco, nicotine and related products (September 2013). 3Smokeless tobacco (February 2008), Additives in Tobacco Products (November 2010).

As the proposal needed to be adopted before the Parliamentary elections in May 2014, this slow progress is significant. We identify several potential reasons for it.

The IA stage

In line with the EU's Smart Regulation agenda, and unlike the 2001 Directive which included only a brief IA,15 the 2014 TPD revision was subjected to a comprehensive IA. This was not finalised until mid-2012, long beyond the anticipated completion in late 2010.60 Two developments likely contributed to this delay. First, after strong industry opposition to a RAND Europe study that provided the baseline for the Commission's IA,61 DG-SANCO commissioned two further studies,62 63 which had not been anticipated in the official roadmap.60 Second, DG-SANCO's public consultation on the Directive attracted over 85 000 submissions, more than any other EU consultation. The Commission attributed this unprecedented response, 57% of which were duplicates, to tobacco industry-led mobilisation campaigns in Italy and Poland,64 while PMI's documents also indicate the industry's role by revealing that the majority of the 85 000+ submissions were ‘known’ to PMI.65

Delays to the Inter-Service Consultation

FOI documents identify three specific delays to the Inter-Service Consultation (ISC), the Commission's internal consultation with Directorates-General (DGs) affected by the proposal, linked to events at the highest level of the Commission (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Delays to the Inter-Service Consultation and linked Undisclosed ‘Meetings’* with the Tobacco Industry. Source: Letters and emails released under Freedom of information requests146–148 and Parliamentary Inquiry.75 BdZ, German Cigar Manufacturers Association; ECMA, European Cigar Manufacturers Association; ESTOC, European Smokeless Tobacco Council; IAB, Impact Assessment Board; ISC, Inter-Service Consultation; PMI, Philip Morris International; Sec-Gen, Secretariat-General; TPD, Tobacco Products Directive. *It is not known whether all meetings occurred in person.

First, Secretary-General Catherine Day (the most senior EU civil servant) and Legal Service's Director-General Luis Romero Requena requested that DG-SANCO postpone the ISC launch scheduled for 22 August 201268–70 because there were “A number of substantial issues needing further attention”.66 They claimed that, despite the draft IA having been approved by the Commission's Impact Assessment Board (IAB) on 12 July 2012, not all issues raised by the IAB had been addressed.66 They also alleged concerns with the proposal's legal basis, an argument identified in a 17 August 2012 PMI document as appealing to the ‘sensitivities’ of the Secretariat-General and the Legal Service (see below).30 Emails between DG-SANCO and Day on 7 September suggest that, as a result, DG-SANCO removed plain packaging and the point of sale display ban from the proposal.71 Second, the ISC launch was further delayed on 23 September following concerns by Day and the Chief of Barroso's Cabinet, Johannes Laitenberger, that “it would be best not to launch the ISC until after the October European Council—this is a text that might well leak even from ISC and we are keen to avoid too much controversy before [then]”.72 Third, on 16 October, days before the rescheduled ISC launch on 22 October, Commissioner John Dalli was forced to resign by President Barroso in an opaque cash-for-access scandal, with Barroso mandating that the ISC should wait until a new Health Commissioner was in place.73 74 Ultimately new Commissioner Tonio Borg launched the ISC 2 days after taking office, on 30 November 2012, 3 months later than originally intended.

Despite FCTC Article 5.3, FOI documents show that the Secretariat-General, the Legal Service, and Barroso's Cabinet held at least 12 TPD-related ‘meetings’ with the tobacco industry between 2010 and 2012 (figure 3). Unlike DG-SANCO's practice, in line with Article 5.3, of publishing minutes of stakeholder meetings on the Commission's website, none of these meetings were publicly disclosed. This includes contact from September 2011 to November 2012 between the Legal Service and Michel Petite who, until 2008, was Director-General of the Commission's Legal Service but, when the meetings occurred, was a consultant to PMI in his role at law firm, Clifford Chance. Despite Legal Service being aware of Petite's new role,75 Petite was twice able to “set out his views on some legal issues of tobacco legislation” and meet with the Legal Service Director-General.75 This is notable because John Dalli claims that Barroso asked him to shelve the TPD in November 2011 because “his [Barroso's] legal services were raising many legal issues”, and that DG-SANCO officials advised him that the Legal Service only started raising concerns following Petite's involvement.70

Cash-for-access controversy: ‘Dalligate’ or ‘Barrosogate’

A further delay within the Commission occurred following the ‘Dalligate’ controversy,76 which some MEPs relabelled ‘Barrosogate’.77 For details see TobaccoTactics.org.78 Petite, acting as proxy for snus manufacturer Swedish Match (which has a joint venture with PMI79), approached Day in March 2012 alleging that Dalli's business associate, Silvio Zammit, tried to solicit €60 million from Swedish Match in return for Dalli lifting the snus sales ban that was included in the 2001 TPD but was being reconsidered in the revision.80 After a written complaint by Swedish Match in May 2012, Day referred the matter for investigation to Giovanni Kessler, Director-General of the EU Anti-Fraud Office (OLAF), and shared the complaint with Romero Requena, Barroso and Laitenberger.75

On 15 October 2012, OLAF finalised its investigation and forwarded its conclusions to Day.75 The following day and, crucially, days before the launch of the Commission's ISC, Barroso forced Dalli to resign, with the Commission's press statement stating that OLAF found that Zammit had approached Swedish Match using his contacts with Dalli and sought to gain financial advantages in exchange for influence over a possible future legislative proposal on snus.81 The Commission's press statement also noted there was “no conclusive evidence” of Dalli's direct participation, and “no transaction was concluded between the company and the entrepreneur [Zammit] and no payment was made”.81 It also emphasised that Dalli maintained his innocence69 82 and in June 2013 the Maltese police stated that there was insufficient evidence to prosecute him.83 84 At the time of writing, Zammit's trial is still ongoing.

Many questioned whether Dalli's alleged misconduct justified his punishment, given that Dalli had not benefited personally, and the text of the proposal had not changed as a consequence.85 86 The Commission's decision came under further scrutiny when the secret OLAF report87 was leaked, presenting only circumstantial evidence against Dalli, retrieved using seriously flawed methods.8 88 89 OLAF concluded, inter alia, that Dalli's unofficial contacts with snus lobbyists (two meetings in total, both in Malta and occurring at the request of Swedish Match and the European Smokeless Tobacco Council (ESTOC)) had not been publicly disclosed and were a breach of the Commissioner's Code of Conduct and the FCTC's Article 5.3.87 Yet senior staff from the Secretariat-General, Legal Service and Barroso's Cabinet met at least 12 times with the tobacco industry (figure 3), without sanction.

Commission delays consistent with PMI's strategy

To block ‘extreme policy options’ at the drafting stage, PMI sought to trigger negative opinions from DGs other than DG-SANCO,30 with ‘Barroso's Circle’ (ie, Secretariat-General and Barroso's Cabinet) identified as having unequivocal power to intervene.30 TTC and third party political activity was targeted at DGs Enterprise, Trade, Agriculture and Rural Development and Internal Market. Perhaps in an attempt to weaken DG-SANCO's position, or to involve the Secretariat-General, TTCs and third parties criticised DG-SANCO's IA and stakeholder consultation,90 arguing that it had failed to account for the proposal's ‘unintended consequences’ (ie, illicit trade).39 91–93

PMI developed five messages to undermine the TPD proposal that would appeal to other DGs: lack of evidence, lack of logic, lack of acknowledgement of the public consultation response, failure of the IA to adequately assess impacts on the tobacco market, notably illicit trade, and lack of a legal basis.30 All except the ‘lack of logic’ message feature repeatedly in FOI documents.93–98 FOI documents also show that the Commission received various industry-commissioned technical reports,99–102 three of which are identified in PMI's documents as ‘tools’ for strengthening pro-tobacco arguments.30 103–105 Two of these reports stressed and costed what the tobacco industry considered ‘negative’ or ‘unintended’ socioeconomic consequences.103 104 FOI documents also show that Commissioners and senior officials were invited to tobacco industry events,47 98 106–109 including a BAT stakeholder event on harm reduction and illicit trade,33 BAT's annual lunch with policy elites,110 111 and PMI's launch of KMPG's (heavily criticised112) study on illicit trade.113

Progress through the parliament and council in codecision

‘Break ENVI's full control on the dossier’

In January 2013, after 4 years in the Commission, the proposed legislation moved to the Parliament and Council (figure 2). To increase the prominence of market versus public health arguments, PMI encouraged the appointment of the Internal Market Committee (IMCO) as co-lead parliamentary committee, alongside the Health Committee (ENVI) which would normally preside over this file. Interview data, however, suggests that Dalli's departure had resulted in rare, all-party support to move the TPD forward, and that to assign IMCO co-chair status would have led to another scandal (interviews, MEP and health advocate, January 2014). As one MEP recalled, “we guessed that the next tactic would be that they shouldn't give [the proposal] to the environment committee [ENVI]…, but it was really a nonstarter…it would have been another scandal…they shot themselves in the foot with that” (interview MEP, January 2014).

PMI hoped to generate opposition from the five appointed Committees for Opinion (International Trade, Internal Market, Legal Services, Agriculture and Rural Development and Industry Research and Energy).30 31 To this end, PMI's documents reveal a lobbying offensive targeting MEPs as early as 2010, when the proposal was still being drafted.114 PMI meticulously assessed each MEP's position on TPD policy options and sensitivity to pro-tobacco arguments,115–117 identifying ‘heavy weights’ within each political group, particularly the largest centre-right European People's Party (EPP),118 and the Committees for Opinion.119 PMI's national offices approached MEPs in their constituencies,114 where MEPs are more ‘off-guard’ without staff reminding them of protocol (interview MEP, January 2014). By August 2012, when the Commission had finalised the proposal's IA, PMI lobbyists had already met with one-third of MEPs (257 of 754).30

PMI's documents note that the Dalli controversy negatively impacted their ability to access policymakers.31 FOI documents and interview data confirm that, at least temporarily, it changed the political landscape against the tobacco industry (interviews MEPs and NGO, January 2014). For example, previously amenable DGs120–124 became less inclined to engage with the tobacco industry.125–128 In Parliament, the EPP, on which PMI heavily relied for support,118 decided not to nominate a candidate for TPD rapporteur (the MEP who reports on the proposal and oversees its progress). Instead, in January 2013, Linda McAvan from the Social-Democrats was appointed rapporteur, a choice PMI described as ‘hostile’.31 Interview data suggest that lobbying intensified thereafter, with one MEP describing the tobacco lobby as ‘unbelievably powerful’ (interview MEP, January 2014). Whereas PMI's documents reveal that third parties were ‘activated’ to approach health-friendly MEPs, often hiding their tobacco industry links,35 interview data suggest that former MEPs were purposively recruited to approach MEPs on the basis of being ‘an old friend’ (interview MEP, January 2014). Tobacco-friendly MEPs also attempted to isolate influential MEPs within their own parties who failed to support industry positions (interview MEP, January 2014).

Various amendments tabled by MEPs appeared to have originated from the tobacco industry,129 130 including amendments on ‘delegated acts’ outlined in PMI's documents.31 One MEP commented that ‘…amendments that came on most of the articles were clearly not written by the MEPs, and they weren't things they would normally have been aware of’ (interview MEP, January 2014). One MEP observed that it was TTCs’ innovative packaging, including lipstick-style packs targeting young women, which swayed Parliamentary opinion, and led to McAvan being given the mandate to move the TPD forward.

‘National level is key’: working through National Parliaments and the Council

PMI believed the ‘National level is key’.31 Thus it tried to influence the Commission's initial proposal via national Health Ministers and their officials on the Commission's TPD Regulatory Committee. For example, PMI Netherlands, which had cultivated a relationship with the Dutch Department of Health,131–134 attempted to get the Department to delay the proposal in the Commission, arguing that DG-SANCO's consultation on the RAND report was inadequate and inconsistent with the Commission's IA Guidelines.132

PMI also sought to mobilise national parliaments to cause delay through the ‘yellow card’ system, triggered when a sufficient number of national parliaments issue a ‘reasoned opinion’ that the proposal does not comply with the EU's subsidiarity principle.135 This failed when only seven reasoned opinions were submitted.136 PMI also sought to mobilise a blocking minority in the Council through ‘third party mobilisation’, attempting to frame the debate around employment and small to medium enterprise issues.30 However, the Council reached a consensus on 21 June 2013, with only Poland, Bulgaria, Romania and the Czech Republic opposing it.137

Discussion

Our findings demonstrate that the tobacco industry considered the revised TPD a serious threat and mounted a massive lobbying campaign against it. PMI alone employed more than 160 lobbyists and met individually with a third of MEPs before the proposal reached Parliament. Overall the campaign attempted to shift the debate away from health towards alleged negative economic impacts of the proposal and to isolate or weaken those with an interest in health—DG-SANCO and the Health Commissioner within the Commission, and members of the Parliament's ENVI committee. Former EU officials now working or consulting for the tobacco industry played key roles. Lobbying was directed at all three EU institutions, with TTC access and influence in the European Commission secured via its highest echelons, the Secretariat-General, the Legal Service and Barroso's Cabinet. Intervention by the Secretariat-General led both to the removal of the two provisions that industry was most concerned about—plain packaging and a point of sales display ban—and to repeated delays. We also show that these interventions followed repeated, undisclosed contact between senior Commission officials and the tobacco industry in contravention of Article 5.3. As such, PMI's strategy to ‘delay’ or ‘push’ (ie, amend) the proposal appears to have been successful.

The evidence presented cannot provide an exhaustive summary of all lobbying activity aimed at shaping the TPD. Although we benefited from the availability of PMI's documents, we did not have access to similar data sets from other TTCs. Nonetheless, it is clear from FOI documents and interviews that other TTCs were similarly politically active, and at times collaborated. Data were also biased towards TTCs’ political activity in the Commission (through FOI documents), and to a lesser degree Parliament (through interviews), while less is known about TTCs’ political activity in the Council stage and at national level. The small interview sample reflects the reluctance of EU officials to discuss the TPD while it was still being legislated. Further, the study does not examine the influence of public health groups although it is clear that some, particularly the SFP, played a key role in securing the TPD's success.

Our study has several implications for EU policy. First, the EU's Smart Regulation agenda, specifically its requirements for stakeholder consultation and IA, in which the impacts of policies must be assessed and costed and ‘burdens of legislation’ minimised for ‘economic operators’,19 allowed the industry to frame arguments, engage Commission staff, and delay the Directive's progress. These findings reflect BAT's aims in promoting Smart Regulation tools in the 1990s.19 21 Specifically, the requirement that affected stakeholders be consulted early in the legislative process enabled TTCs to input at the outset and overwhelm the process by mobilising the largest ever response to an EU consultation. The Commission's intention to democratise policymaking through stakeholder consultation138 clearly fails to account for the ability of powerful corporate actors to dominate this process. The requirement for a comprehensive IA led to significant delays so that the TPD proposal took 3 years longer in the Commission than the original 2001 Directive.

Second, an important difference in TTCs’ activities in the current versus the 2001 directive15 was their extensive use of third-party actors. We identified 137 associations and 34 non-TTC companies that voiced support for policy outcomes favoured by the tobacco industry; 12 were identified by PMI as part of its ‘3rd party coalition’. This increased emphasis on third parties likely reflects an unintended consequence of the adoption of the FCTC's Article 5.3. While DG-SANCO clearly complies with 5.3,139 140 other parts of the Commission and some MEPs do not. The fact that senior Commission staff held undisclosed meetings with the tobacco industry, yet cite Article 5.3 as a key reason for Dalli's dismissal shows a misinterpretation and mis-implementation of the Article.

Despite the tobacco industry's success in delaying and amending the 2014 TPD, it was still enacted in April 2014 and significantly advances EU tobacco control. Although plain packaging was removed, pictorial warning labels covering 65% of the pack were implemented and represent an increase of 25–30% from current coverage. Interview data and press coverage9 12 76 141 suggest that the industry's aggressive lobbying and its initial receptive response within parts of the Commission, culminating in the forced resignation of Commissioner Dalli, ultimately backfired. Serious questions began to be raised by NGOs about the transparency of EU policymaking and the influence of the tobacco industry in the Commission. Furthermore, the widely publicised leaked documents alerted MEPs to the tobacco industry's tactics, and the possibility that any contact with industry might ultimately be made public.

Consistent with previous research,19 21 22 142 we show that the EU's approach to IA and Smart Regulation favours corporate interests over public concerns and economic over health considerations,142 143 and can be used to delay and ultimately prevent public health legislation. In contrast, FCTC Article 5.3, which aims to prevent industry influence on policymaking, is poorly understood and inadequately implemented. The Smart Regulation tools must be reviewed to ensure they serve the public and not just corporate interests, uphold Article 5.3, particularly in parts of the Commission not responsible for health and in the European Parliament, and fulfil the EU's broader commitment to transparent policymaking. Evidence that the tobacco industry relied on high-profile former EU officials to secure influence reveals a need to revisit rules on the employment of former Commission staff.144 145 With a new Parliament and Commission recently appointed, including the addition of a new Commissioner for Smart Regulation clearly signalling a prioritisation of this agenda, these reviews are urgently needed.

What this paper adds.

This paper demonstrates that third party actors have become an increasingly important element of tobacco industry lobbying and play a central role in attempts to subvert European Union (EU) tobacco control policies.

During the Tobacco Products Directive (TPD) review, tobacco industry access and influence was secured via the highest echelons of the European Commission, the Secretariat General, the Legal Service and Barroso's Cabinet.

Intervention by these elements of the Commission led both to the removal of the two provisions from the TPD text that industry was most concerned about—plain packaging and a point of sales display ban—and to repeated delays to its progress through the Commission.

These interventions followed repeated, undisclosed contact between senior Commission officials and the tobacco industry, signalling that Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) Article 5.3 is poorly understood and implemented in the Commission, despite it being a signatory to the Treaty since 2005.

This first assessment of how the Smart Regulation agenda affects EU tobacco control policymaking since the system was fully implemented confirms previous concerns that Smart Regulation enables corporate influence, and may thereby undermine EU public health policy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all who generously donated their time to be interviewed. The authors would also like to thank those that shared Commission documents released under freedom of information requests other than our own: Fiona Godfrey (Independent Consultant in European Public Health Policy), Smoke Free Partnership, Corporate Europe Observatory, and colleagues at the Tobacco Control Research Group, University of Bath.

Footnotes

Twitter: Follow Tobacco Research at Bath at @BathTR, David Stuckler at @davidstuckler, and Martin McKee at @martinmckee

Contributors: The study was conceived and designed by ABG and SP. HC and SP collated the tobacco industry documents, SP submitted the freedom of information requests and collated the web content, and ABG and SP conducted the interviews. SP, with input from ABG and HC analysed the data. ABG and SP wrote the first draft of the manuscript. HC, DS and MM contributed to the interpretation of the data, and revising the manuscript. ABG, DS, HC, MM and SP agree with manuscript results and conclusions.

Funding: This work was supported by the US National Cancer Institute Grant Number RO1CA160695. In addition, DS is supported by a Wellcome Trust investigator award. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Cancer Institute or the National Institutes of Health. SP and ABG are members of the UK Centre for Tobacco and Alcohol Studies (UKCTAS), a UK Centre for Public Health Excellence. Funding to UKCTAS from the British Heart Foundation, Cancer Research UK, the Economic and Social Research Council, the Medical Research Council and the National Institute of Health Research, under the auspices of the UK Clinical Research Collaboration, is gratefully acknowledged.

Competing interests: MM is a member of the European Commission Expert Panel on Investing Health.

Ethics approval: This study was approved by the ethics committee of the University of Bath Department for Health in the UK.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: All freedom of information documents, internal tobacco industry documents, and web content analysed for this paper are available on request.

References

- 1.European Commission. Commission Staff Working Document Impact Assessment. Brussels, 2012. http://ec.europa.eu/health/tobacco/products/revision/index_en.htm (accessed 7 Jan 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gilmore A, McKee M. Tobacco-Control Policy in the European Union. In: Feldman EA, Bayer R. Unfiltered. Conflicts over Tobacco Policy and Public Health. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 2004;219–54. [Google Scholar]

- 3.The ASPECT Consortium. Tobacco or Health in the European Union. Past, present and future. Brussels, 2004. http://ec.europa.eu/health/ph_determinants/life_style/Tobacco/Documents/tobacco_fr_en.pdf (accessed 9 Apr 2014). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cairney P, Studlar DT, Mamudu HM. European Countries and the EU. In: Global Tobacco Control. Power, Policy, Governance and Transfer. Basingstoke: Palgrave McMillan, 2012;72–98. [Google Scholar]

- 5.European Commission. Proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council on the approximation of the laws, regulations and administrative provisions of the Member States concerning the manufacture, presentation and sale of tobacco and related products. Brussels, 2012. http://ec.europa.eu/health/tobacco/products/revision/index_en.htm (accessed 7 Jan 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Directive 2014/40/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 3 April 2014 on the approximation of the laws, regulations and administrative provisions of the Member States concerning the manufacture, presentation and sale of tobacco and related products and repealing Directive 2001/37/EC. http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?qid=1399478051133&uri=OJ:JOL_2014_127_R_0001 (accessed 11 Nov 2014).

- 7.Costa H, Gilmore AB, Peeters S, et al. Quantifying the influence of tobacco industry on EU governance: automated content analysis of the EU Tobacco products directive. Tob Control 2014;23:473–8. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vella M. OLAF carried our illegal wiretaping, MEP calls for Giovanni Kessler's resignation. Malta Today 2013. http://www.maltatoday.com.mt/en/newsdetails/news/world/OLAF-carried-out-illegal-wiretapping-MEP-calls-for-Giovanni-Kessler-s-resignation-20130321 (accessed 25 Mar 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hall M. Tobacco debate ‘hotting up’ as Council details leaked to industry. Eur Activ 2013. http://www.euractiv.com/health/tobacco-debate-hotting-council-m-news-519732 (accessed 7 June 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Norman L. John Dalli: “You Become a Pariah”. Wall Street J 2013. http://blogs.wsj.com/brussels/2013/06/11/john-dalli-you-become-a-pariah/ (accessed 12 Jun 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Norman L. Email correspondence offers murky picture on Dalli's resignation. Wall Street J 2012. http://www.onlinewsj.com/article/SB10001424052970203937 004578079333672961470.html (accessed 20 Jun 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Doward J. Tobacco giant Philip Morris’ spent millions in bid to delay EU legislation. Guardian 2013. http://www.theguardian.com/business/2013/sep/07/tobacco-philip-morris-millions-delay-eu-legislation/print (accessed 9 Sep 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Corlett N. ALDE Priorities for the week of 23 Sept 2013. Parliament Agenda, 2013. 23 September. http://www.vieuws.eu/previeuws/parliament-agenda-alde-priorities-for-the-week-of-23-sept-2013/ (accessed 25 Sep 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peeters S, Gilmore AB. How online sales and promotion of snus contravenes current European Union legislation. Tob Control 2013;22:266–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mandal S, Gilmore AB, Collin J, et al. . Block, amend, delay. Report on tobacco industry's efforts to influence the European Union's Tobacco Products Directive (2001/37/EC). Smoke Free Partnership, 2009. http://www.smokefreepartnership.eu/news/block-amend-delay-tobacco-industry-efforts-influence-european-union%E2%80%99s-tobacco-products (accessed 2 Sep 2013).

- 16.Neuman M, Bitton A, Glantz S. Tobacco industry strategies for influencing European Community tobacco advertising legislation. Lancet 2002;359: 1323–30. 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)08275-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.World Health Organization. Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. 2003. http://www.who.int/fctc/text_download/en/ (accessed 19 Mar 2013).

- 18.Smoke Free Partnership. The origin of EU better regulation—the disturbing truth. Brussels, 2010. http://smokefreepartnership.eu/IMG/pdf/Report_version_27012010_-2.pdf (accessed 14 May 2014). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smith KE, Fooks G, Collin J, et al. . Is the increasing policy use of Impact Assessment in Europe likely to undermine efforts to achieve healthy public policy? J Epidemiol Community Health 2010;64:478–87. 10.1136/jech.2009.094300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.European Commission. Better regulation- simply explained. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities, 2006. http://ec.europa.eu/smart-regulation/better_regulation/documents/brochure/brochure_en.pdf (accessed 13 May 2014). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith K, Fooks G, Collin J, et al. “Working the System”—British American Tobacco's influence on the European Union Treaty and its implications for policy: an analysis of internal tobacco industry documents. PLoS Med 2010;7: e1000202 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith K, Gilmore A, Fooks G, et al. . Tobacco industry attempts to undermine Article 5.3 and the “good governance” trap. Tob Control 2009;18:509–11. 10.1136/tc.2009.032300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ulucanlar S, Fooks GJ, Hatchard JL, et al. . Representation and misrepresentation of scientific evidence in contemporary tobacco regulation: a review of tobacco industry submissions to the UK government consultation on standardised packaging. PLoS Med 2014;11:e1001629 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hatchard JL, Fooks GJ, Evans-Reeves KA, et al. . A critical evaluation of the volume, relevance and quality of evidence submitted by the tobacco industry to oppose standardised packaging of tobacco products. BMJ Open 2014;4:e003757 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Forster N. The analysis of company documentation. In: Cassell C, Symon G, eds. Qualitative methods in organizational research: a practical guide. London: Sage Publications, 1997;147–66. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hill MR. Archival Strategies and Techniques. In: Qualitative Research Methods Volume 31 Sage Publications, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gilmore A. Tobacco and transition: understanding the impact of transition on tobacco use and control in the former Soviet Union. London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 28.European Parliament. Procedural file: 2012/0366 (COD) Tobacco and related products: manufacture, presentation and sale 2014. http://www.europarl.europa.eu/oeil/popups/ficheprocedure.do?lang=en&reference=2012/0366%28COD%29 (accessed 12 Nov 2014).

- 29.Ritchie J, Spencer L. Qualitative data analysis in applied policy research. In: Huberman A, Miles M, eds. The Qualitative Researcher's Companion. London: Sage Publications, 2002;305–30. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Philip Morris International. EU Tobacco Products Directive Review 17 August 2012 2012.

- 31.Philip Morris International. TPD Stage II Master Plan. Lausanne, 11 January 2013 2013.

- 32.Philip Morris International. Copy of new Transparency Register. Lists of consultants and their expenses 2013.

- 33.Bowles J. Letter from Jack Bowles (British American Tobacco) to Ms Draghia Aklia, Director of DG RTD. 7 January [Letter] Brussels, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Corporate Europe Observatory. Tobacco lobbyist to become European Commissioner? Exposing the power of corporate lobbying in the EU [Blog] 2014; 12 May. http://corporateeurope.org/blog/tobacco-lobbyist-become-european-commissioner (accessed 21 May 2014).

- 35.Philip Morris International. Stats file. Predicted committee voting outcomes and committee coverage information.

- 36.Philip Morris International. TPD Core Team meeting. 14 September 2011 Brussels, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 37.European Commission Health and Consumers Directorate-General. Meeting with stakeholders on the study “Assessing the Impacts of Revising the Tobacco Products Directive” prepared by RAND Europe. Summary Record. Meeting date: 20 October 2010, 14:30. Brussels, 2010. http://ec.europa.eu/health/tobacco/events/ev_20101019_en.htm (accessed 11 Nov 2014). [Google Scholar]

- 38.European Parliament Committee of Environment Public Health and Food Safety. Participant list of Meeting with Representatives of Stakeholders in the Tobacco Products Supply Chain, 19 March 2013, 12.30–14.30. Brussels, 2013. http://www.europarl.europa.eu/committees/en/envi/events.html?id=other#menuzone (accessed 2 Feb 2014). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wiedenhofer H, Wojciech L, Vedel F. Ref: Social and employment concerns related to the forthcoming review of the Tobacco Products Directive 2001/37/EC and to the Common Agriculture Policy reform. 12 October [Letter]. Brussels, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Global Acetate Manufacturers’ Association. RE: Meeting with [deleted as privacy information]- Follow-up. 8 May [Email], 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mouvement des Entreprises de France. Révision sur la Directive des produits du tabac—Position MEDEF- Comité de la Propriété intellectuelle-. 2012; 7 december [Email].

- 42.Vedel F, Sacchetto C, Pellegrini P. Objet: Representants du secteur tabacole europeen-Demande de rendez-vous. 2010; 4 March [Letter].

- 43.McAvan L. Report on the proposal for a directive of the European Parliament and of the Council on the approximation of the laws, regulations and administrative provisions of the Member States concerning the manufacture, presentation and sale of tobacco and related product (COM(2012)0788—C7-0420/2012–2012/0366(COD)). 2013. http://www.europarl.europa.eu/sides/getDoc.do?pubRef=-%2f%2fEP%2f%2fTEXT%2bREPORT%2bA7-2013-0276%2b0%2bDOC%2bXML%2bV0%2f%2fEN&language=EN (accessed 2 Sep 2013).

- 44.Gagneur V. EFFAT—UNITAB—FETRATAB/meeting on the post 2013 CAP reform. 2011. 12 September [Email]. [Google Scholar]

- 45.EFFAT, FETRATAB, UNITAB. Letter to DG AGRI dated 29 October 2013 2013. 29 October [Letter].

- 46.Risso G. Tobacco retailers Position paper on TPD possible revision 2011. 22 April [Email and position paper].

- 47.Risso G. Letter from CEDT to Commissioner Ciolos dated 28 September 2011 2011. 28 September [Letter].

- 48.European Commission Health and Consumers Directorate-General. Minutes of the meeting between Commissioner Dalli and representatives of the economic stakeholders active in tobacco products on 7 March 2012. Brussels, 2012. http://ec.europa.eu/health/tobacco/events/index_en.htm#anchor2 (accessed 10 Nov 2014). [Google Scholar]

- 49.European Commission Directorate General for Agriculture and Rural Development. Cabinet's meeting with representatives of the European tobacco business, Bruxelles, 20th September 2011, 11h. Brussels, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vedel F. Letter from Unitab to Commissioner Lewandowski dated 23 November 2010. 23 November [Letter] Brussels, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mueller M. Subject: our conversation yesterday. 5 December [Email] Brussels, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Polish Chamber of Trade. Official statement of Trade Committee concerning Tobacco Product Directive (2001/37/WE) 2011. 16 February [Position Paper].

- 53.Bremen van H. Notes from meeting January 10, 2012 on EU TPD (Tobacco Product Directive). 2012. 10 January 2012 [Minutes]. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bremen van H. Notes from meeting December 14, on EU TPD (Tobacco Product Directive). 2011. 14 December 2011 [Minutes]. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Paisley warns of severe job losses at JTI if tobacco directive gets green light. Ballymena Times 2013. 19 November. http://www.ballymenatimes.com/news/business/paisley-warns-of-severe-job-losses-at-jti-if-tobacco-directives-get-green-light-1-5692174 (accessed 20 Nov 2013).

- 56.Fleming J. Lobbyists link EU tobacco curbs to rising crime, Roma. Eur Activ 2011. http://www.euractiv.com/health/lobbyists-claim-tobacco-rules-threaten-roma-news-506560 (accessed 17 Jul 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mapother J. Smoking kills- quit now. Tob J Int 2013. http://www.tobaccojournal.com/Smoking_Kills___Quit_Now.51930.0.html (accessed 20 Nov 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 58.Briggs F. Forest urges retailers to lobby MPs and MEPs on EU Tobacco Products Directive. Retail Times 2013. http://retailtimes.co.uk/forest-urges-retailers-lobby-mps-meps-eu-tobacco-products-directive/# (accessed 29 Aug 2013).

- 59.Confederation Europeenne des Detaillants en Tabac. Declaration of intentions for a sustainable future of the tobacco sector 2012. Undated [Position paper].

- 60.DG SANCO. Roadmap: revision of the tobacco products directive. Brussels, 2010. http://ec.europa.eu/governance/impact/planned_ia/docs/46_sanco_tobacco_products_directive_en.pdf (accessed 11 Nov 2014). [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rand Europe. Assesssing the Impacts of Revising the Tobacco Products Directive. Study to support a DG SANCO Impact Assessment. Final Report 2010. http://ec.europa.eu/health/tobacco/products/revision/index_en.htm (accessed 11 Apr 2014). [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 62.Matrix Insight. Economic analysis of the EU market of tobacco, nicotine & related products, Revised Final Report. 2013. http://ec.europa.eu/health/tobacco/docs/tobacco_matrix_report_eu_market_en.pdf (accessed 20 May 2014).

- 63.RAND Europe. Availability, accessibility, usage & regulatory environment for novel & emerging tobacco, nicotine or related products 2012. http://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR211.html (accessed 20 May 2014).

- 64.European Commission Health and Consumers Directorate-General. Report on the public consultation on the possible revision of the Tobacco Products Directive (2001/37/EC). Brussels, 2011. http://ec.europa.eu/health/tobacco/consultations/tobacco_cons_01_en.htm (accessed 11 Nov 2014). [Google Scholar]

- 65.Philip Morris International. EU in Practice. April 11th, 2012 Croatia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Day C, Romero Requena L. Forthcoming legislative proposal on the revision of the tobacco product directive. 25 July 2012 [Letter] Brussels, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Day C. Letter from Catherine Day to Swedish Match's General Counsel in response to official complaint made by Swedish Match on 14 May 2012 2012. 30 May [Letter].

- 68.New Europe. New Europe interview with John Dalli. [Video] 2012. 17 October. http://www.neurope.eu/article/exclusive-john-dalli-interview-olaf-resignation-tobacco-directive-video (accessed 18 Oct 2012). [Google Scholar]

- 69.Vella M. [WATCH] ‘I expected Barroso to support me’—Dalli. Malta Today 2012. http://www.maltatoday.com.mt/en/newsdetails/news/national/WATCH-I-expected-Barroso-to-support-me-Dalli-20121020 (accessed 11 Nov 2014).

- 70.Mangion C. Dalli: ‘Barroso was against the tobacco products directive’. Malta Today 2014. http://www.maltatoday.com.mt/news/dalligate/36855/dalli_barroso_was_against_the_tobacco_products_directive (accessed 17 Mar 2014).

- 71.Testori Coggi P. Email from Paola Testori Coggi to Catherine Day and Luis Romero Requena dated 7 September 2012 2012. 7 September [Email].

- 72.Day C. Email from Catherine Day to Paola Testori Coggi dated 23 September 2012. [Email] Brussels, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Vella M. Barroso to MEPs, no work on tobacco review until Borg is commissioner. Malta Today 2012. http://www.maltatoday.com.mt/news/world/22071/barroso-to-meps-no-work-on-tobacco-review-until-borg-is-commissioner-20121023#.U0kxd0ZOUaI (accessed 12 Apr 2014).

- 74.‘We need to wait’- Barroso on Tobacco Products Directive. New Europe 2012. 23 October. http://www.neurope.eu/article/we-need-wait-barroso-tobacco-products-directive (accessed 12 Apr 2014).

- 75.European Commission and OLAF. Replies to the Questionnaire from the Committee on Budgetary Control of the European Parliament concerning the resignation of the former Commissioner John Dalli. Brussels, 2012. http://www.europarl.europa.eu/committees/en/cont/subject-files.html?id=20121211CDT57804 (accessed 9 Apr 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 76.European Commission: “Dalligate” spreads like wildfire in Brussels. Presseurop 2012; 25 October. http://www.presseurop.eu/en/content/news-brief/2942321-dalligate-spreads-wildfire-brussels (accessed 21 Aug 2013).

- 77.Update: No longer Dalligate but Barrosogate- Green MEP. Malta Star 2013; 7 May. http://www.maltastar.com/dart/20130507-dalligate-green-meps-meet-maltese-officials (accessed 2 Sep 2013).

- 78.Tobacco Control Research Group. TPD: Dalligate. TobaccoTactics, 2013. http://tobaccotactics.org/index.php/TPD:_DalliGate (accessed 6 Nov 2014). [Google Scholar]

- 79.Swedish Match. Press Release 3 Feb 2009: Swedish Match and Philip Morris International announce global joint venture to commercialize smokefree tobacco products 2009. http://www.swedishmatch.com/en/Media/Pressreleases/ (accessed: 5 Sep 2011).

- 80.European Anti-Fraud Office. Written Record of Interview with Witness: Mr Fredrik Peyron, 2 June 2012. OLAF Final Report no. OF/2012/0617 2012.

- 81.European Commission. Press statement on behalf of the European Commission. Brussels, 2012. http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_MEMO-12-788_en.htm (accessed 16 Oct 2012). [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lindsay D. Dalli claims his ‘entrapment orchestrated from the very beginning’. Malta Independent 2013. http://www.independent.com.mt/articles/2013-06-16/news/dalli-claims-his-entrapment-orchestrated-from-the-very-beginning-1834713088/ (accessed 2 Sep 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 83. No criminal case against John Dalli- Police Commissioner. Times of Malta. 8 June 2013. Available from: http://www.timesofmalta.com/articles/view/20130608/local/no-criminal-case-against-john-dalli-police-commissioner.473049 (accessed 19 Feb 2015).

- 84.Malta rules out legal action against former EU Commissioner. Reuters 2013; 10 June. http://www.reuters.com/article/2013/06/10/malta-eu-commissioner-idUSL6N0EM00020130610 (accessed 11 Nov 2014).

- 85.McKee M, Belcher P, Kosinska M. Comment: the tobacco products directive must not be derailed. Lancet 2012;380:1447–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Dalligate: Transparency group says Barroso's people met tobacco lobbyists. Times of Malta 2012; 15 December. http://www.timesofmalta.com/articles/view/20121215/local/transparency-group-says-barroso-s-people-met-tobacco-group.449676 (accessed 15 Apr 2014).

- 87.Giovanni Kessler. Transmission of information following a closure of investigation. Brussels, 2012. http://www.maltatoday.com.mt/en/newsdetails/news/dalligate/Olaf-report-00720130427 (accessed 11 Nov 2014). [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ingeborg Grassle. Working document: analysis of the failings of the OLAF investigation. Brussels, 2013. http://www.europarl.europa.eu/sides/getDoc.do?type=COMPARL&reference=PE-510.771&format=PDF&language=EN& secondRef=01 (accessed 10 Nov 2014). [Google Scholar]

- 89.OLAF Supervisory Committee. Activity Report of the OLAF Supervisory Committee January 2012–January 2013. 2013. http://www.scribd.com/doc/137703980/OLAF-Supervisory-Committee-Annual-Report-2012 (accessed 10 Nov 2014).

- 90.Bota P. Open letter—meeting request from tobacco growers from Romania and Bulgaria. 2012; 5 December [Email].

- 91.Confederation of European Community Cigarette Manufacturers. CECCM mail on TPD revision. 2012; 11 December [Email].

- 92.Confederation Generale des Petites et Moyenne Entreprises. Letter from CGPME to Commissioner Tajani dated 21 September 2012. 2012; 21 September [Letter].

- 93.European Federation of Food Agriculture and Tourism Trade Unions. EFFAT submission to DG SANCO on the public consultation on the RAND report and on the revision of the Tobacco Products Directive 2001/37/EC. 2010; 1 December [Position paper].

- 94.Institute of Practitioners in Advertising. Re: Institute of Practitioners in Advertising (IPA) states concerns about trademark issues in context with the plain packaging proposals in the Tobacco Products Directive. 15 December [Letter]. London, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Nowakowski W. Letter from the Polish Chamber of Commerce to President Barroso dated 5 October 2011. [Letter] Przewodniczący Komitetu Handiu, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Panucci M. Letter from Confindustria to European Commission President Barroso dated 28 September 2012. 28 September [Letter] Rome, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Vanheukelen M. Letter from Head of de Gucht's Cabinet Marc Vanheukelen to Karla Jones representing ALEC. 2011; 11 June 2011 [Letter].

- 98.Risso G. Letter from CEDT to Karel de Gucht titled European Parliament Round Table 24.05.11. 2011; [Email].

- 99.Oxera. Proposed revisions to the Tobacco Products Directive. A review of the European Commission's regulatory impact assessment. Japan Tobacco International, 2013. http://www.jti.com/how-we-do-business/key-regulatory-submissions/ (accessed 17 Oct 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 100.Roland Berger Strategy Consultants. The New Tobacco Products Directive. Potential Economic Impact. 2013. http://www.rolandberger.com/media/publications/2013-04-24-rbsc-pub-The_New_Tobacco_Products_Directive.html (accessed 11 Nov 2014).

- 101.De Molli V. Letter from The European House Ambrosetti to European Commission President Mr Jose Manual Barroso dated 5 September 2012. 5 September [Letter] Milan: The European House Ambrosetti, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 102.KPMG. Project Star 2011 Results. 2012. http://www.pmi.com/eng/tobacco_regulation/illicit_trade/documents/project%20star%202011%20results.pdf (accessed 23 Jun 2014).

- 103.Nomisma. The cultivation of tobacco in the European Union and the impact deriving from the Changes in Directive 2001/37/EC. Analysis of socio-economic impact, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 104.Calderoni F, Savona EU, Solmi S. Crime proofing the policy options for the revision of the Tobacco Products Directive. Proofing the policy options under consideration for the revision of EU Directive 2001/37/EC against the risks of unintended criminal opportunities. 2012.

- 105.Minhoff C, Mrohs A. Revision of the Tobacco Products Directive 2001/37/EC. 6 December [Letter] Berlin, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 106.Benyei I. Letter from Magyar Dohanytermelok Orszagos Szovetsege to Commissioner Ciolos dated 29 July 2011. 29 July [Letter] Pocspetri, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 107.Unitab. Invitation to the Cabinet of the Commissioner for Agriculture and Rural Development, for dinner-debate in the presence Mr Marek Sawicki on the theme ‘The future of small farms with intensive workforce requirements in th epost-2013 cap: the case of tobacco-growing’. 20 April [Letter] Paris, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 108.Karapyta M, Ptaszynski M. Letter from East Poland House in Brussels to Commissioner Ciolos dated 29 June 2012. 29 June [Letter] Brussels, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 109.Ujupan A-S. RE: Invitation au 33ème congrès de l'UNITAB -18-20 octobre 2012, Budapest -ARES/784077. 9 July [Email] Brussels, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 110.Trevilly Y. Letter from British American Tobacco to Commissioner Michel Barnier dated 1 June 2011; 1 June 2011 [Letter] Boulogne-Billlancourt, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 111.Trevilly Y. Objet: invitation au prochain dejeuner du CPAH. 5 June [Letter] Boulogne-Billancourt, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 112.Gilmore AB, Rowell A, Gallus S, et al. Towards a greater understanding of the illicit tobacco trade in Europe: a review of the PMI funded ‘Project Star’ report. Tob Control 2014;23:e51–61. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Doms K. Philip Morris International invite to presentation of the KPMG study on illicit tobacco trade 2011; 14 June 2011 [Letter].

- 114.Philip Morris International. AA Master File. Background information and meeting details of most MEPs by country 2012.

- 115.Philip Morris International. “EU Tobacco Products Directive Review”—strategy meeting presentation II, 17 August 2012 2012.

- 116.Philip Morris International. ENVI MEP Stimulator 2.08.2012. Positions of MEPs in ENVI 2012.

- 117.Philip Morris International. IMCO MEPs. List of MEPs in IMCO 2012.

- 118.Philip Morris International. “ENVI analysis” 2013.

- 119.Philip Morris International. “EU Tobacco Products Directive Review”—strategy presentation for meeting 17 August 2012 2012.

- 120.European Commission Directorate General Enterprise and Industry. Réunion CECCM 12/07 9h30—10h30. 12 July [Minutes] Brussels, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 121.European Commission Directorate General Enterprise and Industry. Meeting with GAMA—2012-05-16. 16 May [Minutes] Brussels, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 122.European Commission Directorate General Enterprise and Industry. Meeting with cigars producers. 15 September [Minutes] Brussels: European Commission, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 123.British American Tobacco Representation Brussels. Meeting 8 March 2012. 2012; 14 March [Email]. [Google Scholar]

- 124.European Commission Directorate General Enterprise and Industry. RE: Meeting with ESTA—02/08/2012. 3 August [Minutes] Brussels, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 125.European Commission Directorate-General for Enterprise and Industry. Re;Reunion. 18 October [Email] Brussels, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 126.European Commission Directorate General Enterprise and Industry. Re: Reunion. 1 December [Email] Brussels, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 127.European Smoking Tobacco Association. RE: Reunion 2012; 30 November [Email].

- 128.European Commission Directorate General Enterprise and Industry. FW: CECCM mail on TPD revision. 12 December [Email] Brussels, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 129.Corporate Europe Observatory. Tobacco lobbyists all fired up ahead of key vote. Brussels, 2013. http://corporateeurope.org/sites/default/files/attachments/tobacco_lobbyists_all_fired_up_ahead_of_key_vote.pdf (accessed 29 May 2014). [Google Scholar]

- 130.Smoke Free Partnership. Comparison of PMI objectives and plenary amendments. Smoke Free Partnership, Brussels, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 131.RE: fabrieksbezoek Philip Morris Holland 2010. Collection. Bates No: JB0642. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/hro18j00 (accessed 12 Sep 2013).

- 132.Philip Morris Holland BV. Impact Assessment herziening Tabaksproductenrichtlijn 2009. Collection. Bates No: JB0680. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/tso18j00 (accessed 3 May 2014).

- 133.Philip Morris Benelux BVBA. RE: Afspraak over ingrediënten van tabaksproducten 2009. Collection. Bates No: JB0616. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/hqo18j00 (accessed 12 Sep 2013).

- 134.Philip Morris Benelux BVBA. RE: Impact assessment herziening Tabaksproductenrichtlijn 2010. Collection. Bates No: JB0626. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/rqo18j00 (accessed 12 Sep 2013).

- 135.Protocol on the application of the principles of subsidiarity and proportionality, Treaty of Lisbon, in 2007/C 306/01 Official Journal of the European Union, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 136.Petitjean S. Tobacco directive passes subsidiarity test. Clear The Air News Tobacco Blog [Blog], 2013. http://tobacco.cleartheair.org.hk/?p=7112 (accessed 29 May 2014).

- 137.Joossens L. Update on the Tobacco Products Directive (as of June 2013) 2013; 18 December 20132. http://www.europeancancerleagues.org/tobacco-control/62-tobacco-control-products-directive-in-the-eu/311-new-directive-2013.html (accessed 29 May 2014).

- 138.Kluver H. Lobbying in the European Union. Interest groups, lobbying coalitions, and policy change. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 139.Weishaar HB. Stakeholder engagement in European health policy. A network analysis of the development of the European Council Recommendation on smoke-free environments. University of Edinburgh, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 140.Weishaar H, Amos A, Collin J. Capturing complexity: mixing methods in the analysis of a European tobacco control policy network. Int J Soc Res Methodol 2014:1–18. 10.1080/13645579.2014.897851 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Martin A. Philip Morris Leads Plain Packs Battle in Global Trade Arena. Bloomberg 2013; 22 August. http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2013-08-22/ philip-morris-leads-plain-packs-battle-in-global-trade-arena.html (accessed 2 Sep 2013).

- 142.Tarkowski S, Ricciardi W. Health impact assessment in Europe—current dilemmas and challenges. Eur J Public Health 2012;22:612 10.1093/eurpub/cks120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Salay R, Lincoln P. The European Union and Health Impact Assessments. Are they an unrecognised statutory obligation? 2008. http://www.safestroke.eu/files/8613/8642/0470/HIA_Report.pdf (accessed 25 Jun 2014). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 144.ALTER-EU. ALTER-EU Briefing: review of revolving door rules in Staff Regulations 2013. http://www.alter-eu.org/sites/default/files/documents/ALTER-EU_Revolving%20door%20rules%20in%20Staff%20Regulations.pdf (accessed 25 Jun 2014).

- 145.Darbishire H, Bank M, de Clerck P, et al. . FINAL Letter to Barroso on Revolving Doors Commissioners 21 January 2014 Brussels, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 146.Watson J. Meeting on revision of tobacco products directive. 3 May 2010 [Email], 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 147.Jonet N, Klaus H, Morel G. Meeting request. Email correspondence between Nuno Jonet and Cabinet Barroso 7–14 June 2011 [Email], 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 148.Pappas SA. Re: request for a meeting. 13 June 2012 [Email]. Brussels, 2012. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.