Abstract

The class I ribonucleotide reductases (RNRs) are composed of two homodimeric subunits: R1 and R2. R2 houses a diferric-tyrosyl radical (Y•) cofactor. Saccharomyces cerevisiae has two R2s: Y2 (β2) and Y4 (β′2). Y4 is an unusual R2 because three residues required for iron binding have been mutated. While the heterodimer (ββ′) is thought to be the active form, several rnr4Δ strains are viable. To resolve this paradox, N-terminally epitope-tagged β and β′ were expressed in E. coli or integrated into the yeast genome. In vitro exchange studies reveal that when apo-(His6)-β2 (Hisβ2) is mixed with β′2, apo-Hisββ′ forms quantitatively within 2 min. In contrast, holo-ββ′ fails to exchange with apo-Hisβ2 to form holo-Hisββ and β′2. Isolation of genomically encoded tagged β or β′ from yeast extracts gave a 1:1 complex of β and β′, suggesting that ββ′ is the active form. The catalytic activity, protein concentrations, and Y• content of the rnr4Δ and wild type (wt) strains were compared to clarify the role of β′ in vivo. The Y• content of rnr4Δ is 15-fold less than that of wt, consistent with the observed low activity of rnr4Δ extracts (<0.01 nmol min−1 mg−1) versus wt (0.06 ± 0.01 nmol min−1 mg−1). FLAGβ2 isolated from the rnr4Δ strain has a specific activity of 2 nmol min−1 mg−1, similar to that of reconstituted apo-Hisβ2 (10 nmol min−1 mg−1), but significantly less than holo-Hisββ′ (~2000 nmol min−1 mg−1). These studies together demonstrate that β′ plays a crucial role in cluster assembly in vitro and in vivo and that the active form of the yeast R2 is ββ′.

Ribonucleotide reductases (RNRs)1 catalyze the conversion of ribonucleotides to deoxyribonucleotides, providing the monomeric precursors for DNA replication and repair (1). The class I RNRs are composed of a large subunit, R1, and a small subunit, R2. R1 contains the site of nucleotide reduction and the allosteric effector binding sites that control the rate and the specificity of nucleotide reduction. R2 houses the diferric-tyrosyl radical (Y•) cofactor required for RNR activity. The budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae has two R2 genes: RNR2 and RNR4. RNR2 is essential and the corresponding protein, designated Y2 or β2,2 is a homodimer containing the essential residues conserved in all R2s that are required to form the cofactor (2, 3). RNR4, however, is essential for viability only in some genetic backgrounds (4−6). The protein, designated Y4 or β′2, is a homodimer and has substitutions in three of the six conserved amino acids required for iron binding (5, 6).

Recent studies from several labs have suggested that the active form of R2 in S. cerevisiae is a heterodimer (ββ′) composed of one protomer of Y2 and one of Y4 (7−9). Only β can form the essential diferric-Y• cofactor, and thus, there is a maximum of 1 Y•/ββ′ (2, 3). Previously, our laboratory has demonstrated that β′ is required to generate the diferric-Y• cofactor of β in vitro, and Thelander and co-workers have proposed, on the basis of their inability to isolate active R2 unless RNR2 and RNR4 were coexpressed in Escherichia coli, that ββ′ is the active form of yeast R2 (7−9). However, the paradox of the viability of several rnr4Δ strains remains and has led us to further investigate the role of β′ and the active form of yeast R2 in vitro and in vivo.

Two proposals for the role of β′ in vivo have been put forth: that of an iron chaperone for β and that of a stoichiometric folding chaperone for β (8, 9). The proposal that β′ is an iron chaperone was inspired by the discovery of a copper chaperone protein required for copper delivery to the copper–zinc superoxide dismutase (10−12). The observation that the diferric-Y• cofactor of β could not be reconstituted in vitro unless β′ was also present supported this hypothesis (9). However, a 1:1 ratio of β2/β′2 is required to obtain protein with maximal activity for nucleotide reduction, and the ββ′ is stable, indicating that β′2 is not acting catalytically in the activation of β2 in vitro (7). Additionally, experiments to demonstrate Fe2+ or Fe3+ binding to β′2 have not been successful (7).

The proposal that β′ is a stoichiometric folding chaperone (8) is not consistent with our successful expression and isolation of a hexa-histidine-tagged version of β2 (Hisβ2) in the absence of β′2 (7). Furthermore, a crystal structure of the apo-Hisβ2 has been solved, revealing that it is folded and structurally homologous to other R2s (13). These results argue against the folding chaperone hypothesis. Thus, the biochemical evidence is inconsistent with both proposed roles for β′2, and neither proposal explains the viability of the rnr4Δ strains.

Recently, a new model for the role of β′2 was proposed on the basis of the crystal structures of the apo-Hisβ2 and β′2 in comparison with the structure of the partially Zn-loaded Hisββ′ (13, 14). This comparison reveals that helix αB of β, which houses Asp145 that binds to Fe1, converts from a disordered state in β2 to an ordered state in ββ′. These observations suggested that β′ stabilizes a local conformation of β to facilitate cofactor assembly. The caveat with this model, however, is that ββ′ was crystallized at pH 4.9 and does not have an assembled cofactor.

Structural and biochemical experiments have established that the ββ′ is an active R2 in vitro. Two observations made soon after the discovery of RNR4, however, seemed to contradict the hypothesis that ββ′ is the active yeast R2 in vivo. The first was that immunolocalization studies using overexpressed N-terminally epitope-tagged RNR proteins revealed that β was localized predominantly to the cytoplasm, while β′ was localized predominantly to the nucleus (6). Recently, however, the subcellular localization of β and β′ was reinvestigated using polyclonal antibodies (Abs) to β and β′ (15). These new experiments established that β and β′ are co-localized to the nucleus and undergo a nucleus to cytoplasm redistribution in response to a need for biosynthesis of deoxynucleotides during DNA replication or repair. Thus, the subcellular localization patterns of β and β′ no longer contradict the hypothesis that ββ′ is the active form of the yeast R2.

The second observation that contradicts the essential role of ββ′ was the fact that deletion of RNR4 is not lethal in some strain backgrounds (4, 5). While these strains grow slowly, they must still be capable of making deoxynucleotides to support cell division; thus, β2 must be an active form of yeast R2 in these strains.

Here, we present experiments that provide further support for the hypothesis that the ββ′ is the active form of yeast R2 in vitro and to further examine the active form of R2 in vivo. Several experiments utilizing Hisβ2, Hisββ′, HAβ′2, and ββ′ have allowed us to demonstrate that, while the apo forms of these R2s are capable of exchanging their protomers, assembly of the diferric-Y• cofactor prevents exchange. Re-examination of cofactor assembly with Hisβ2, with a focus on the lower limit of detection for Y• and nucleotide reductase activity, revealed that an active homodimer of Hisβ2 can form with a specific activity 200-fold lower than that of Hisββ′. A comparison of S. cerevisiae wt and rnr4Δ strains for catalytic activity, Y• content by whole-cell EPR, and protein concentrations has also been carried out. The very low concentration of Y• and RNR activity measured in the rnr4Δ strain and the ability to generate very low levels of activity and Y• of Hisβ2 in vitro explains the phenotypic consequences of RNR4 deletion. These in vitro and in vivo results support the hypothesis that the ββ′ is the active form of yeast R2 in vivo.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Talon resin was obtained from BD Biosciences. Complete protease inhibitor tablets, calf intestine alkaline phosphatase, and DNaseI from bovine pancreas were obtained from Roche. Biotinylated thrombin and Streptavidin agarose were obtained from Novagen. Spin filter microcentrifuge tubes, with a 0.45 µM cellulose acetate filter, were obtained from Corning. Amicon ultra YM30 centrifugal devices were purchased from Millipore. Bradford reagent, anti-MYC, anti-HA, anti-FLAG agarose, 3×FLAG peptide (consisting of three tandem copies of the FLAG epitope), HA peptide, and all other chemicals were obtained from Sigma–Aldrich.

Protein Purification

Purification of α, Hisβ2, and β′2, in vitro reconstitution of the diferric-Y• cofactor, RNR nucleotide reduction assay, and ferrozine assay to determine iron content were carried out as described (7, 9). The concentration of Hisβ2, β′2, and the Hisββ′ were determined using the known extinction coefficients (ε280–310) 105 600, 94 000, and 99 800 M−1 cm−1, respectively (7). The protein concentration for α, α′, and crude extracts were determined by the Bradford assay, with BSA as the standard.

Vector Construction for Expression of HAβ′2 in E. coli and Its Purification

The plasmid for expression of β′2 fused to an N-terminal HA tag (HAβ′2) in E. coli, pMH784, was constructed as follows. The 2.75-kb Nhe I–Arv II genomic DNA fragment containing RNR4 was subcloned into the Xba I site of pRS413 (16), resulting in pMH131. An Nde I site was created at the first ATG of RNR4 by site-directed mutagenesis of pMH131 to generate pMH164. pMH164 was digested with Nde I and Xho I, and the resulting 1.2-kb fragment containing RNR4 was ligated into the Nde I and Xho I sites of pETxHA (17) to generate pMH784. pMH784 was transformed into BL21(DE3) CodonPlus RIL cells with selection on LB/ampicillin. HAβ′2 was expressed and purified as described previously for β′2 (9). A typical recovery was 75 mg of HAβ′2 from 4.5 g of cell paste.

Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

Stock solutions of Hisβ2 (84 µM) and β′2 (110 µM) were diluted with 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.6), 100 mM NaCl, and 5% glycerol (DSC buffer) to final concentrations of 5.2 µM for Hisβ2 and 1.5 µM for β′2. Apo-Hisββ′ (40 µM) was exchanged into DSC buffer by dialysis overnight at 4 °C (Slide-a-lyzer, 30-kDa MWCO, Pierce). The dialyzed Hisββ′ was then diluted in DSC buffer to a final concentration of 4.2 µM. All buffer and protein solutions were passed through a 0.2 µm filter and degassed for 5 min using a ThermoVac at 10 °C, while stirring with a small magnetic stir bar. The DSC experiments were performed with a VP-DSC microcalorimeter (Microcal) equipped with a matching sample and reference cells (0.52 mL). Experiments were performed at a scan rate of 90 °C/h for β′2 or 60 °C/h for Hisβ2 and Hisββ′. A pre-scan equilibration period of 15 min was applied to allow the temperatures in the sample and reference cells to stabilize. The scans were collected using a passive feedback mode and a filtering period of 16 s for β′2 or 8 s for Hisβ2 and Hisββ′. Data were analyzed using the DSC software package from Microcal.

Rate of Apo-Hisββ′ Formation from Hisβ2 and β′2

Hisβ2 was diluted into 25 mM HEPES (pH 7.4), 10% glycerol, 100 mM NaCl, and 1 mg/mL BSA (buffer A) to a final volume of 900 µL and a concentration of 1.1 µM. This solution was preincubated at 25 °C for 5 min. The exchange reaction was initiated by the addition of 100 µL of β′2 from a 10 µM stock in buffer A that had also been pre-equilibrated at 25 °C. The final concentration of Hisβ2 and β′2 was 1 µM. Aliquots (75 µL) were removed and passed through a 100 µL Talon column. Immediately after the protein solution was soaked into the column (~5 s), the column was washed with 3 mL of buffer A without BSA. The bound protein was eluted with 300 µL of 300 mM imidazole in buffer A without BSA. The eluted protein was analyzed by 12% SDS–PAGE. Coomassie-stained bands were quantified by comparison to a standard curve of Hisβ and β′ using a ChemiDoc XRS and the QuantityOne software (BioRad).

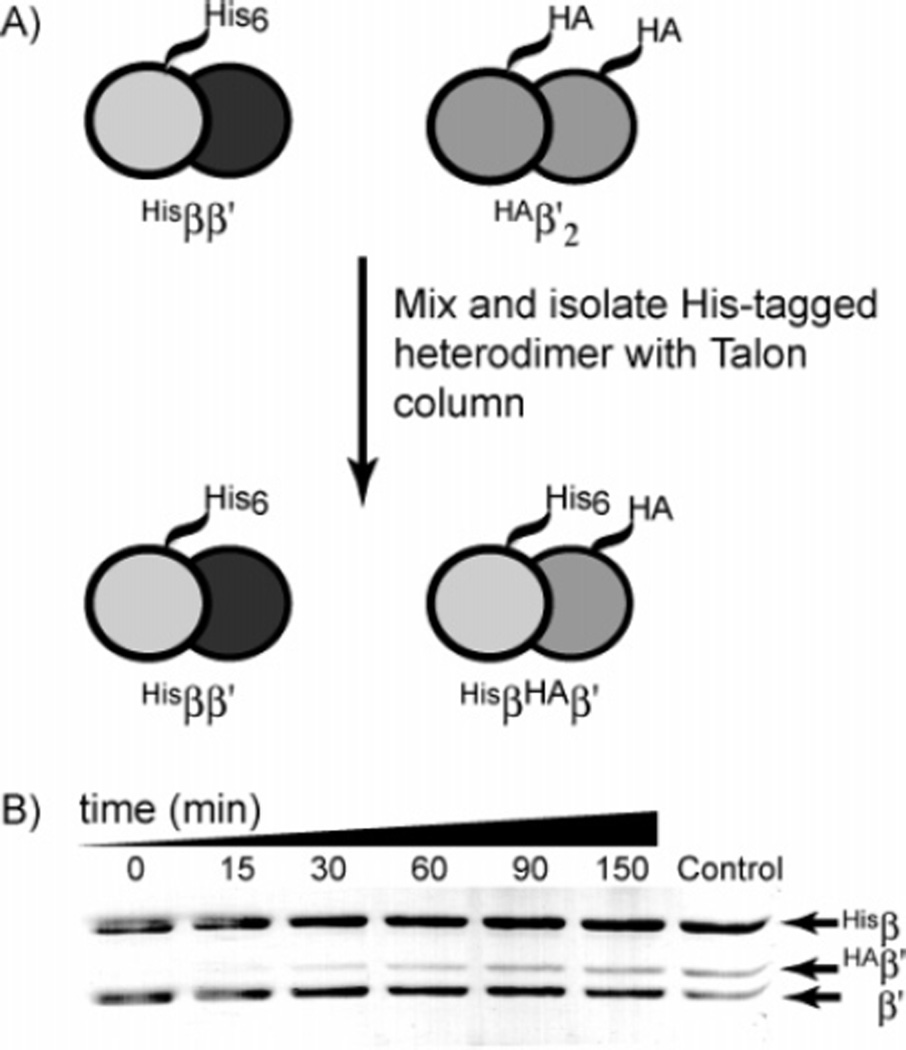

Apo-Hisββ′ Exchange with HAβ′2

Hisβ2 and β′2 were mixed at 25 °C for 15 min to generate the apo-Hisββ′ at a concentration of 1 µM in a final volume of 750 µL of 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.4), 50 mM KCl, 100 mM NaCl, and 10% glycerol (buffer B). The exchange reaction was initiated by the addition of HAβ′2 to a final concentration of 0.5 µM from a concentrated stock solution also preincubated at 25 °C. Aliquots (120 µL) were removed and incubated with 25 µL of Talon resin in a spin filter tube with gentle mixing for 1 min. The unbound protein was removed by centrifugation at room temperature at 700g for 2 min, and the column was washed with 3 mL of buffer B in six 500 µL aliquots. The bound protein was eluted from the resin with 60 µL of 25 mM HEPES (pH 7.4), 25 mM KCl, 50 mM NaCl, 500 mM imidazole, and 5% (v/v) glycerol and analyzed on a 12% SDS–PAGE gel.

Thrombin Cleavage of the His Tag from Holo-Hisββ′

Holo-Hisββ′ (3.4 mg) was mixed with 3 units of biotinylated thrombin for 1 h on ice in 50 mMHEPES (pH 7.4) and 5% glycerol. The holo-Hisββ′ has a specific activity of 2000 nmol min−1 mg−1, 0.3 Y•/Hisββ′ and 1.3 irons/Hisββ′. The thrombin was removed by incubation with Streptavidin agarose (250 µL of agarose slurry in storage buffer as supplied by the manufacturer) for 30 min on ice with periodic gentle mixing. The mixture was transferred to a spin filter microcentrifuge tube, and the resin-bound protease was separated from the ββ′ by centrifugation at 700g. The ββ′ was incubated with 250 µL of Talon resin to remove the cleaved His tag and any remaining Hisββ′. The mixture was transferred to a spin filter tube, and the Talon resin was removed. RNR activity assay of the thrombin-cleaved heterodimer revealed that removal of the His tag did not change its specific activity.

Holo-ββ′ Exchange with Hisβ2

Hisβ2 and holo-ββ′ were mixed in buffer B at a final concentration of 1 µM and a final volume of 14 mL. A control reaction was carried out in parallel, which was treated exactly the same as the exchange experiment except that Hisβ2 was omitted. This control allowed for correction for the loss of iron, radical, and activity associated with protein loss during the extensive washing and concentration steps in the experiment. The exchange reaction was incubated at 25 °C for 2 h, and the entire mixture was passed through a 750 µL Talon column. The flow through (FT) and the first 2 mL of the wash were collected and concentrated to less than 500 µL with an Amicon ultra YM30 centrifugal device. The column was washed with an additional 4 mL of buffer B, and the bound protein was eluted with 4 mL of buffer B with 200 mM imidazole. The eluted protein was concentrated to less than 500 µL with an Amicon ultra YM30 concentrator. The concentration of radical was determined by EPR as outlined below for whole-cell EPR experiments. The RNR activity was determined using the standard yeast RNR activity assay utilizing α with a specific activity of 200 nmol min−1 mg−1 (7).

Yeast Strains and Plasmids

The yeast plasmid pMH176 for expression of the galactose inducible 3× Myc-tagged β′ (Mycβ′) was provided by Prof. S. J. Elledge (Harvard Medical School) (6).

MHY343 (MATx, can1-100, ade2-1, his3-11,14, leu2-3, trp1-1, ura3-1, rnr2::FLAG-RNR2-Kan) contains an N-terminally FLAG-tagged β (Flagβ) integrated into the endogenous RNR2 locus. The Flagβ has the protein sequence MDYKDDDDKH-β. The construction of pMH725, which was used for integration of FLAG-RNR2 into the endogenous RNR2 locus, was complicated, and thus, instead of describing the multiple steps involved in its construction, we will describe the segments in linear order. The backbone of pMH725 is essentially identical to pFA6a-kanMX6 (18), except that both the Nde I and the Nco I sites were removed by digestion with the respective restriction enzyme, treatment with T4 DNA polymerase to fill in the ends, and religation, thus adding six nucleotides to the resulted product, pMH706. Nucleotides 1–1520 in pMH725 are the kanMX6 cassette (18). Nucleotides 1521–2971 are the following sequences on the complementary strand: RNR2 promoter sequence, the start codon, and a FLAG-encoding sequence (CC ATG GAC TAC AAA GAC GAT GAC GAC AAT), followed by a Nde I site and the coding sequence for the N-terminal 199 residues of β. The rest of pMH725 (nucleotide 2972–5378) is identical to that of pFA6a-kanMX6 (1534–3938) except for the filled-in Nde I site.

MHY343 was generated by integration of a linearized pMH725, which was cut by EcoR V in the RNR2 coding sequence (between codons 118 and 119), into the chromosomal RNR2 locus. This integration resulted in a FLAG-RNR2, under the control of the RNR2 promoter, as the only full-length RNR2-encoding sequence at the endogenous RNR2 locus. The integration event in MHY343 was confirmed both by PCR analysis of the RNR2 locus and Western blotting of the expected Flagβ using both anti-β and anti-FLAG Abs.

MHY614 (MATa, his3-11,14, leu2-3, ura3-1, rnr4::LEU2, rnr2::FLAG-RNR2-Kan) contains FLAG-RNR2 integrated into the endogenous RNR2 locus and deletion of RNR4. A rnr4::LEU2 deletion allele was generated in the diploid strain CUY546 (5) by homologous replacement using a 5.4-kb Nhe I–Xho I fragment as described previously (6), resulting in MHY49. A FLAG-RNR2-kanMX6 was then generated in MHY49 by integration using a linearized pMH725. The resulting diploid strain, containing both RNR4/rnr4::LEU2 and RNR2/FLAG-RNR2-kanMX6, was sporulated, and a haploid of rnr4::LEU2, FLAG-RNR2 genotype was isolated by tetrad dissection and confirmation of the LEU2 and kanMX6 markers.

MHY346 (MATa, can1-100, ade2-1, his3-11,14, leu2-3, trp1-1, ura3-1, rnr4::HA-RNR4-Kan) contains HA-RNR4 integrated into the endogenous RNR4 locus. The HAβ′ has the protein sequence: MPYPYDVPDYASLGGH-β′. pMH708, which was used for integration of HA-RNR4 into the endogenous RNR4 locus, was generated by cloning a 2.5-kb EcoR I fragment that contains the RNR4 promoter, the start codon, a HA-encoding sequence, plus a linker sequence (ATG CCT TAC CCA TAC GAT GTT CCA GAT TAC GCT AGC TTG GGT GGT), followed by an Nde I site and the coding sequence for the N-terminal 303 residues of β′. MHY346 was generated by integration of a linearized pMH708, which was cut by Msc I in the RNR4 coding sequence (between codons 211 and 212), into the chromosomal RNR4 locus. This integration resulted in a HA-RNR4, under the control of the RNR4 promoter, as the only full-length RNR4-encoding sequence at the endogenous RNR4 locus. The integration event in MHY346 was confirmed both by PCR analysis of the RNR4 locus and Western blotting of the expected HAβ′ using both anti-HA and anti-β′ Abs.

The wt strain BY4741 (MATa his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0) and rnr4Δ strain (isogenic to BY4741 except for rnr4::KAN) were obtained from Open Biosystems (4).

In Vivo Concentration of Y• by Whole-Cell EPR Spectroscopy

Yeast cultures (1 L) were grown to mid-log phase (2 × 107 cells/mL) in YPD at 30 °C. The doubling times were 90 and 180 min for the wt and rnr4Δ strains, respectively. The cells were collected by centrifugation at 7500g for 15 min. The cell pellet was washed 2 times with 1 L of ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The pellet was then resuspended in PBS with 30% glycerol to a final concentration of 1–3 × 1010 cells/mL. The concentration of cells in the sample was determined by cell counting using a hemacytometer. For each sample, three independent dilutions were made and the average was used as the cell concentration for the data analysis. The standard deviation was typically 15–20%. The cell suspension was transferred to an EPR tube and frozen in liquid nitrogen.

EPR spectra were recorded using a Bruker ESP-300 X-band (9.4 GHz) spectrometer equipped with an internal frequency counter and an Oxford ESR900 liquid helium cryostat to maintain the temperature at 30 K for all samples. Typical instrument parameters were centerfield, 3340 G; sweep width, 100 G; resolution, 2048 points; frequency, 9.38 GHz; modulation amplitude, 2.0 G; conversion time, 81.920 ms; time constant, 40.960 ms; sweep time, 167.772 s; gain, 0.2–5 × 105; scans, 3–30; and power, 200 or 2.5 µW for the yeast and E. coli Y•, respectively. The double-integral values of the derivative spectra were corrected for differences in power, receiver gain, and number of scans and compared to a standard curve. The Y• of E. coli R2 (2.5–115 µM) was used to generate a standard curve. The concentration of Y• in the E. coli standard was determined by the drop-line correction method (19), and the protein concentration was determined using the known ε280 of 131 mM−1 cm−1. For determination of the Y• concentration in vivo, the EPR spectrum of yeast cells treated with hydroxyurea (150 mM, 1 h) was subtracted from that of untreated cells to subtract contributions from species other than the Y• of RNR as described (20). The cell volume used for BY4741 and rnr4Δ strains was 41 and 68 fL, respectively (21).

Expression and Purification of MycY4 from the rnr4Δ Strain

The plasmid pMH176 was transformed into the rnr4Δ strain using a standard protocol (22). The transformants were selected on Synthetic Complete medium without uracil (SC-Ura). The resulting rnr4Δ strain was grown at 30 °C in 2 L of SC-Ura medium with 2% raffinose as the carbon source until the culture reached mid-log phase (~2 × 107 cells/ mL). The production of Mycβ′2 was induced with the addition of galactose to a final concentration of 2%, and the cells were grown for an additional 5 h at 30 °C. Cells were collected by centrifugation (7500g, 15 min), washed with 50 mL of PBS containing 30% glycerol, and stored at −80 °C.

Cells (6.5 g) were resuspended in 20 mL of 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.4), 1 mM EDTA, 100 mM NaCl, and 10% glycerol (buffer C) supplemented with 25 µg/mL aprotinin, 10 µM (2S,3S)-3-(N-{(S)-1-[N-(4-guanidinobutyl)carbamoyl]3-methylbutyl}carbamoyl)oxirane-2-carboxylic acid (E-64), 0.4 mM 4-(2-aminoethyl)benzenesulfonyl fluoride (AEB-SF), 100 µg/mL of pepstatin, 100 µg/mL leupeptin, 100 µg/ mL chymostatin, 1 mM benzamidine, and 50 units of DNaseI. All purification steps were carried out at 4 °C. Cells were lysed by two passes through the French press at 14 000 psi, and cell debris was removed by centrifugation (30000g, 30 min). The supernatant was passed through a column (1.5 mL) of anti-Myc agarose 2 times at a flow rate of 0.1–0.2 mL/min. The column was washed with 15 mL of buffer C supplemented with the Complete protease inhibitor tablet. The protein was eluted from the column by the addition of 5 mL of 100 mM ammonium hydroxide. The eluted protein was collected in 1 mL aliquots, and a part of each aliquot was analyzed on a gradient gel (5–15%, BioRad) and stained with the Silver Stain Plus kit, according to instructions of the manufacturer (BioRad). The identity β and Mycβ′ was confirmed by Western blotting utilizing β- or β′-specific polyclonal Abs.

Purification of Flagβ and HAβ′

The yeast strains MHY343 and MHY346, harboring Flagβ and HAβ′, respectively, were grown to mid-log phase in YPD (2 L) at 30 °C. These strains grew with a doubling time similar to that for wt cells. Cells were collected by centrifugation (7500g, 15 min), washed with 50–100 mL of PBS with 30% glycerol, and stored at −80 °C.

The protein purification was performed at 4 °C. The cell pellets (1–2 g) were resuspended in buffer C supplemented with protease inhibitors as described for the purification of Mycβ′2. For every gram of cell paste, 10 mL of buffer C was used and 5 units of DNaseI was added for every milliliter of cell suspension. Cells were lysed by two passes through the French press at 14 000 psi. Cell debris was removed by centrifugation (30000g, 45 min). The crude supernatant was passed through 500 µL of either anti-HA or anti-FLAG agarose. Each column was washed with 75 mL of buffer C supplemented with a Complete protease inhibitor tablet. The protein was eluted with the 3×FLAG peptide (100 µg/mL in buffer C) or the HA peptide (250 µg/mL in buffer C). Eluted protein was concentrated with an Amicon ultra YM30 centrifugation device. Protein was analyzed on a 12% SDSPAGE gel and stained with Coomassie. Protein identity was confirmed by Western blotting with β or β′ Abs (9).

For purification of Flagβ2 from the rnr4Δ strain, MYH614 was grown in 10 L YPD at 25 °C and had a doubling time of 8–9 h. Flagβ2 was isolated as described above with a yield of 1 mg from 10 g of cell paste. This protein contained a significant amount of DNA contamination with a λmax of 269, and therefore, the protein concentration was determined by a Bradford assay using Hisββ′ as a standard.

Yeast Extract Activity Assays

A yeast culture (2 L) was grown at 30 °C to mid-log phase (1–3 ×107 cells/mL) in YPD. The cells were collected by centrifugation at 7500g for 15 min. If the activity assay was not performed on the same day as the cell growth, the cell pellet was washed with 50–100 mL of ice-cold PBS with 30% glycerol and stored at –80 °C.

All steps were carried out at 4 °C. The cell pellet (1 g) was resuspended with 10 mL of 50 mM TRIS (pH 7.9), 5% glycerol, 10 mM MgCl2, 300 mM (NH4)2SO4, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 25 µg/mL aprotinin, 10 µM E-64, 0.4 mM AEBSF, 100 µg/mL of pepstatin, 100 µg/mL leupeptin, 100 µg/mL chymostatin, 1 mM benzamidine, 10 mM NaF, and 100 mM β-glycerophosphate (buffer D). Cells were lysed by three passes through the French press (14 000 psi), and cell debris was removed by centrifugation (30000g, 30 min). DNA was removed by the dropwise addition of polyethylenimine (2% stock solution adjusted to neutral pH) to a final concentration of 0.2%. The precipitate was removed by centrifugation (30000g, 30 min). The supernatant was treated with solid ammonium sulfate to 65% saturation (430 mg/mL). The precipitated proteins were collected by centrifugation (30000g, 30 min). The protein pellet was dissolved in a minimal volume of buffer D, and 3 mL of the protein was desalted with a Sephadex G-50 column (0.7 × 16 cm) equilibrated in 25 mM HEPES (pH 7.2), 25 mM MgSO4, and 50 mM (NH4)2SO4 supplemented with the Complete protease inhibitor tablet. The protein concentration was determined by the Bradford assay and immediately used in an activity assay without freezing. Freezing and storage at −80 °C was found to decrease the activity.

All assays were carried out on extracts partially purified as described above. The assays contained 2–5 mg/mL extract, 30 mM DTT, 3 mM ATP, 1 mM [14C]-CDP (5000 cpm/nmol), 100 mM HEPES (pH 7.2), 10 mM MgSO4, and 10 mM NaF. All components except extract were mixed and preincubated at 30 °C for 5 min. The assay was initiated by the addition of extract that was also equilibrated to 30 °C. Aliquots (30 µL) were removed over 30 min and quenched in a boiling water bath for 2 min. After the pH was adjusted to 8.5 by the addition of 50 µL of 1 M TRIS (pH 8.5), alkaline phosphatase (60 units) and deoxycytidine (0.5 µmol) were added and the mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 3 h. The products were analyzed by the method of Steeper and Steuart (23).

Western Blotting

Typically an aliquot of crude extract (100–500 µL, before the precipitation of DNA) was removed from the sample generated for activity assays as described above. A portion of this aliquot was utilized to determine the protein concentration by a Bradford assay. The crude extract was diluted into 4× Laemmli (1 part Laemmli/3 parts crude extract), frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C. Western blots used RNR subunits (Hisα, Hisβ2, α′, or β′2) purified from E. coli as standards (7, 9). The standards (2–100 ng) and crude extract (1–10 µg) were analyzed on a 10% SDS–PAGE gel (BioRad Criterion Gel). The proteins were transferred to PVDF (Sequiblot PVDF, BioRad) using a tank transfer unit in transfer buffer (25 mM TRIS, 192 mM glycine, 10% methanol, and 0.1% SDS at 4 °C) at 56 V for 90 min. Western blots were carried out as described previously, except that the blots were developed with the DuraWest Chemiluminescent Reagent (Pierce) (7). The chemiluminescent signal was detected with a CCD camera (ChemiDoc XRS, BioRad). Bands were quantified using BioRad’s QuantityOne software. The results of the quantitative Westerns are presented as the concentration of polypeptide in vivo and thus are based on monomer molecular weights.

Co-immunoprecipitation of β from rnr4Δ Extracts with HAβ′2

The wt and rnr4Δ strains were grown in YPD at 30 °C to 2 × 107 cells/mL. All steps were performed at 4 °C. The cell pellet (1 g) was resuspended with buffer C supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors as described above, and cells were lysed by 3 passages through the French press at 14 000 psi. Cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 30000g for 30 min. The concentration of protein in the extract was determined by the Bradford assay, with BSA as the standard.

Crude extract (0.17–5.4 mg) was mixed with 8 µg (200 pmol) of HAβ′2 in buffer B, and the mixture was incubated on ice for 30 min. Anti-HA agarose (20 µL of agarose beads in a total volume of 40 µL) was added, and the mixture was incubated for an additional 45 min on ice with periodic mixing. The resin was collected by centrifugation at 700g for 5 min and 4 °C. The resin was washed 2 times with 500 µL of buffer B. The resin was transferred to a spin filter tube, where it was washed with an additional three aliquots (500 µL) of buffer B. The protein was eluted with 60 µL of a low-pH IgG elution buffer (Pierce), diluted with 4× Laemmli, and analyzed by SDS–PAGE (12%).

Assembly of the Diferric-Y• Cofactor from Hisβ2, Fe2+, and O2

The reconstitution procedure was followed as described previously with minor changes (7, 9). A stock solution of Hisβ2 (4 mg/mL, 42 µM) in 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.4) and 25% (w/v) glycerol was deoxygenated by repeated cycles of vacuum pumping and argon flushing on a Schlenk line and brought into the anaerobic wet box. A total of 5 equiv of FeII/Hisβ2 were added from a 1 mM deoxygenated FeSO4 solution to the Hisβ2 along with sufficient buffer to dilute the protein 2-fold from its initial concentration and incubated at room temperature for 30 min. The protein was removed from the box, and ~⅓ volume of O2-saturated 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.4), 5% (v/v) glycerol, and 15 mM MgCl2 buffer (buffer D) was added dropwise. Excess iron was removed by applying the mixture to a 10 mL Talon column and washing with 50 mL of buffer D. The protein was then eluted from the column with 20 mL of buffer D plus 200 mM imidazole. Fractions were collected, and those containing protein were pooled and concentrated using an Amicon Centricon fit with a YM30 membrane. The imidazole was removed by passage of the protein over a Sephadex G-25 column previously equilibrated in buffer D. Protein quantification, EPR analysis, and activity assays were carried out as described above.

RESULTS

Stability of Hisβ2

Our circular dichroism (CD) and crystallographic studies revealed that Hisβ2 (with N-terminal sequence MGSSHHHHHHSSGLVPRGSHM-β) expressed in and isolated from E. coli is a soluble and folded protein (9, 13). Thelander and co-workers have reported that their Hisβ2 construct (with N-terminal sequence MHHHHHHM-β) was unable to fold correctly in E. coli as evidenced by inclusion body formation and low recoveries in attempted purifications (8). We believe the differences in Hisβ2 behavior may be associated with the differences in the His-tag constructs.

The stability of our Hisβ2 construct was further examined by a variety of methods, given its difference in behavior relative to the similar construct reported by Chabes et al. Previously, we have shown that the CD spectrum of Hisβ2 is similar to that of β′2 and that it is a predominantly helical protein (7). Removal of the His tag from Hisβ2 using thrombin, however, resulted in a large decrease in helical content, indicated by a 30% change in the Θ at 208 nm (data not shown). Efforts to assemble the diferric-Y• cofactor from the resulting β2 and β′2, generated ββ′ with only 30–40% of the activity routinely obtained with a similar experiment using Hisβ2. Finally, we have also observed that when chromatographed on either DEAE- or Q-Sepharose both tagged and untagged β2 elute in broad peaks and with low recoveries. These observations together indicate that, while our Hisβ2 is soluble and folded, it is unstable.

These findings are perhaps not surprising because, in general, apo-R2s, even E. coli R2, are considerably less stable than their cofactor-assembled counterparts. In an effort to quantify the relative stability of the Hisβ2 and β′2 and the apo-Hisββ′, each protein was examined using DSC. The results of a typical set of experiments for Hisβ2 and β′2 are shown in Figure 1. In each case, the unfolding of the protein was followed by irreversible aggregation as indicated by a rapid decline in heat capacity at temperatures ≥55 °C for Hisβ2 and apo-Hisββ′ and ≥75 °C for β′2. This irreversible aggregation prevents extraction of meaningful quantitative data from these melting curves. However, qualitatively, the Tm values (the temperature at the peak of the unfolding curve) measured under similar conditions reflect the relative stabilities of Hisβ2, β′2, and apo-Hisββ′. Apo-Hisβ2 has a Tm of ~30 °C as compared to 50 °C for β′2. The unfolding of apo-Hisββ′ was immediately followed by a large decrease in the heat capacity associated with precipitation, preventing a reliable determination of the Tm (data not shown). These observations suggest that β2 might belong to a growing class of proteins that are partially unfolded in vivo (24). Alternately, β2 could be stabilized in vivo through binding to β′2 or folding chaperones.

Figure 1.

DSC experiments with Hisβ2 and β′2. (A) Thermal denaturation curves of 5.2 µM Hisβ2. Three scans were acquired under identical conditions as described in the Materials and Methods. (B) Thermal denaturation curves of 1.5 µM β′2. Three scans were acquired under identical conditions as described in the Materials and Methods.

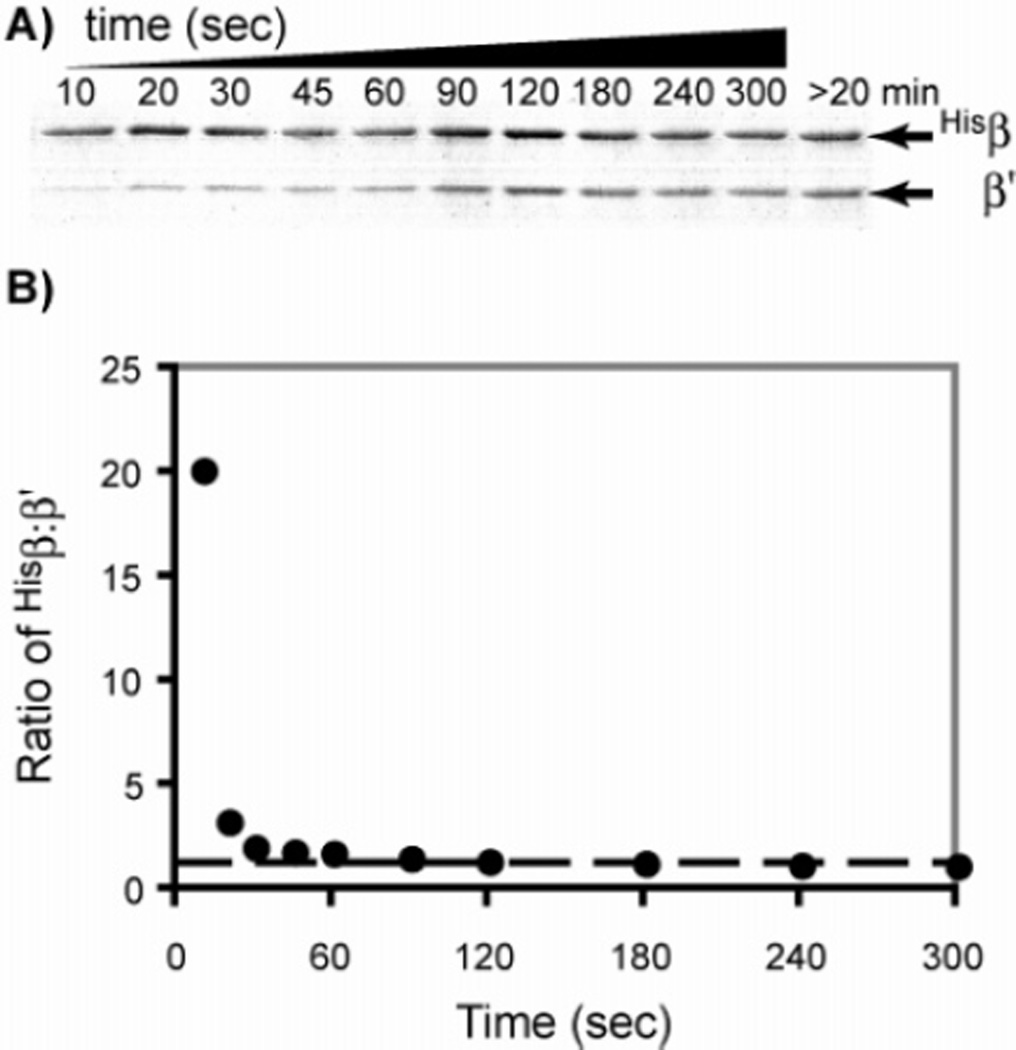

Rate of Exchange of Hisβ2 with β′2 To Form Apo-Hisββ′ Is Fast

We have shown that apo-Hisββ′ can be reconstituted from Hisβ2 and β′2 expressed and purified independently (7). However, it is important to measure the kinetics of this reorganization as an indicator of whether this process could occur under physiological conditions. Furthermore, Chabes et al. reported that, when Hisβ2 and β′2 were mixed for 10 min at 30 °C in the presence of Fe2+, DTT, and O2, this mixture had only 2% of the activity observed with their Hisββ′ isolated from coexpression of HIS–RNR2 and RNR4. They concluded from these observations that β and β′ must to be cotranslated to efficiently form ββ′ or that other cellular components are required (8). To measure the rate of ββ′ formation, Hisβ2 and β′2 were mixed at concentrations found in vivo (1 µM) (7). Aliquots were removed from this mixture over 5 min and quickly passed through columns containing the Talon resin, which efficiently binds the His tag in either Hisβ2 or Hisββ′. Control experiments were carried out to ensure that the binding capacity of the resin was sufficient to quantitatively bind the Hisβ. After the column was washed to remove any β′2 that had not exchanged to generate Hisββ′, the bound protein was eluted with imidazole and the products of exchange were analyzed by SDS–PAGE (Hisβ, 48 kDa; β′, 40 kDa; Figure 2). To quantify the extent of exchange, the ratio of Hisβ/β′ at each time point was analyzed by densitometry. Apo-Hisββ′ forms rapidly because a band for β′ can be seen within 10 s of mixing Hisβ2 and β′2. Apo-Hisββ′ formation is complete within 2 min, demonstrating that its rate of formation is sufficiently fast to be physiologically relevant. However, one should remember that the β2 used in these experiments is modified by a His tag.

Figure 2.

SDS–PAGE and densitometry analysis of the rate of ββ′ formation. (A) SDS–PAGE (12%) analysis of the metal-affinity column-bound fraction. Hisβ2 and β′2 were mixed at a final concentration of 1 µM and incubated at 25 °C. At the times indicated above each lane, an aliquot was removed and subjected to metal-affinity chromatography. The bound protein consisting of Hisβ2 and/or Hisββ′ was eluted with imidazole and analyzed by SDS–PAGE. (B) Densitometry analysis of the SDS–PAGE gel shown in A. The intensity of each protein band was quantified by a comparison to a standard curve generated using known amounts of Hisβ or β′. The ratio of Hisβ/β′ for each lane is plotted as a function of incubation time before separation of the products by metal-affinity chromatography. The dotted line represents the 1:1 ratio of Hisβ/β′.

Exchange of Apo-Hisββ′ with HAβ′2 To Form Apo-HisβHAβ′

An exchange reaction was carried out to test the ability of apo-Hisββ′ to undergo further exchange (Figure 3). Hisβ2 and β′2 were mixed at a final concentration of 1 µM and allowed to equilibrate to form apo-Hisββ′. An aliquot was removed from this mixture, passed through a metal-affinity resin and eluted to demonstrate that apo-Hisββ′ had quantitatively formed (Figure 3B, t = 0). HAβ′2 (1 µM) was then added to the apo-Hisββ′, and the mixture was incubated for 2.5 h. Aliquots were removed over this period and subjected to metal-affinity chromatography. After washing and elution of the bound protein, the products of the exchange reaction were analyzed by SDS–PAGE (Figure 3B). A band for HAβ′ can be seen slowly increasing over time, indicating that the apo-Hisββ′ is capable of undergoing exchange. Interestingly, the rate at which this species exchanges its protomers is much slower than the rate of apo-Hisββ′ formation. After several hours of incubation, the ratio of HAβ′/β′ was only about 1:3. To ensure that the HA tag on β′ does not affect that stability of the apo-HisβHAβ′, a control experiment was completed in which HAβ′2 and β′2 were mixed together at equimolar concentrations before the addition of an equimolar amount of Hisβ2. If the HA tag does not have an effect on the relative stability of the heterodimer, then the Hisββ′ and HisβHAβ′ should be formed in equal amounts. This mixture was passed through a Talon column to isolate any heterodimer that had formed during this control exchange reaction. As seen in the last lane in Figure 3B, the ratio of HAβ′/β′ in this isolated heterodimer mixture is 1:1, suggesting that the presence of the HA tag does not affect heterodimer formation. These results demonstrate that protomer exchange is possible from apo-Hisββ′. However, the slow rate of exchange at physiological concentrations indicates that it is probably not physiologically important.

Figure 3.

Exchange of apo-Hisββ′ with HAβ′2. Apo-Hisββ′ was mixed with the HAβ′2 and at the times indicated above each lane; an aliquot was removed and subjected to metal-affinity chromatography. The bound protein, containing a mixture of Hisββ′ that has not undergone any protomer exchange and HisβHAβ′, was eluted, and the products were analyzed by SDS–PAGE (12%). For the lane marked control, the HAβ′2 and β′2 were mixed before the addition of Hisβ2 to generate the heterodimer mixture containing an equal concentration of Hisββ′ and HisβHAβ′.

Holo-ββ′ Does Not Exchange with Hisβ2 To Form Holo-β2

We wanted to determine if a cofactor-loaded β2 could be generated from apo-Hisβ2 and holo-ββ′. To differentiate between β originating from Hisβ2 and the holo-heterodimer (holo-ββ′), the His tag was removed from the latter using thrombin. Several problems complicated data analysis from this experiment. The first is that the holo-ββ′ used in our experiments contains only 1.3 irons and 0.3 Y• because of our inability to stoichiometrically assemble the cofactor in vitro. Therefore, only 30% of the holo-ββ′ has a fully assembled diferric-Y• cofactor, and the remaining 70% includes apo-ββ′ and partially iron-loaded heterodimer. Thus, some exchange is possible between the apo forms of these proteins. The second problem is associated with the instability of Hisβ2 discussed above and the low concentrations used in the exchange reaction (1 µM) to mimic physiological conditions. Because of these problems, typical protein recoveries are only ~80%. To control in part for the protein loss in this experiment, the holo-ββ′ was subjected to the same conditions in the absence of Hisβ2.

Three different outcomes are possible in this experiment and are illustrated in Figure 4A, 1–3. Figure 4A1 describes the products expected if the holo-ββ′ exchanges only with itself to form holo-β2 and β′2 but not with Hisβ2. All of the iron, radical, and enzymatic activity would be found in the FT of the Talon column. During the purification of holo-Hisββ′, we previously demonstrated that the ratio of Hisβ/β′ remains 1:1 after metal-affinity and anion-exchange chromatography (7). Thus, this possibility is ruled out.

Figure 4.

Holo-ββ′ does not undergo any protomer re-organization. (A) Outline of the exchange experiment and possible outcomes. (1) Holo-ββ′ exchanges with itself to generate a holo-β2 that would be isolated in the FT fraction; (2) Holo-ββ′ exchanges with Hisβ2 to generate a holo-Hisββ, which would be found in the column-bound fraction; and (3) no exchange resulting in isolation of holo-ββ′ in the FT fraction and Hisβ2 in the bound fraction. (B) SDS–PAGE analysis of the observed products present in the FT and bound (B) fractions.

Two additional exchange processes are possible (Figure 4A2 and 3) that would result in different partitioning of the Y• containing Hisβ into either the metal-affinity column-bound or FT fractions. If the holo-ββ′ exchanges with Hisβ2 (Figure 4A2), then the column-bound fraction should contain Y• as a result of the generation of holo-Hisββ. Alternately, if no exchange occurs between Hisβ2 and holo-ββ′ (Figure 4A3), then all of Y•, iron, and activity should be recovered in the column FT. As shown in Figure 4B and summarized in Table 1, the FT fraction contains 75–85% of the total activity, iron, and Y•, supporting scenario 4A3in which the diferric-Y• cofactor in β prevents subunit exchange.

Table 1.

Holo Exchange Experimenta

| flow-through fraction [experiment (control)]b |

bound fraction [experiment (control)] |

|

|---|---|---|

| activity | 84% (79%) | 1% (ND)c |

| iron | 76% (93%) | 24% (19%) |

| radical | 86% (83%) | 1% (ND)c |

The percent recovery of the activity, iron, and radical present in the initial 14 nmol of ββ′ heterodimer added to the exchange experiment.

The control consisted of only the holo-ββ′ in the absence of Hisβ2 to control for the loss of activity, iron, and radical because of the loss of protein and not an exchange process.

ND = none detected.

Analysis revealed that the Talon-bound fraction had a small amount of iron, Y•, and activity above the amounts observed in the control (Table 1). SDS–PAGE analysis revealed that the bound fraction also contained small amounts of β′ (Figure 4B), suggesting the presence of cofactor holo-Hisββ′. As noted above, a likely explanation of these observations is our inability to stoichiometrically generate holo-Hisββ′. The apo-ββ′ could slowly exchange with Hisβ2 to form apo-Hisββ′, which could subsequently pick up adventitious iron during the experiment and assemble the small amount of the diferric-Y• cofactor observed in the bound fraction.

It is also possible that this small amount of cofactor associated with the column-bound fraction arose from the exchange process outlined in Figure 4A2. However, less than 1% exchange occurred over 2 h, suggesting that this process is not physiologically important. Thus, cofactor-loaded β2 cannot be formed from the heterodimer, suggesting that the active form of the yeast R2 in vitro is ββ′.

Isolation of ββ′ from Yeast Crude Cell Extracts

The experiments presented thus far have been designed to probe the relative stabilities of Hisβ2, β′2, and Hisββ′ in vitro and have shown that, once iron is loaded into the heterodimer, no further re-organization is observed. The in vitro data do not, however, rule out the possibility that this re-organization could occur in vivo with the assistance of accessory proteins that have not yet been identified. In fact, the viability of the rnr4Δ strain suggests that there must be a mechanism for activation of β2 in vivo. Thus, a number of experiments utilizing epitope-tagged R2s and gene-deletion strains have been carried out to explore the relative stabilities of the homodimers and heterodimer in vivo.

To investigate the active form(s) of yeast R2 in vivo, Mycβ′ was overexpressed from a plasmid transformed into the rnr4Δ strain. Anti-Myc agarose was used to purify Mycβ′, and a 1:1 complex of β/Mycβ′ was isolated (Figure 5A). To ensure that the isolation of the heterodimeric complex was not an artifact because of overexpression of Mycβ′, similar experiments were carried out with two additional yeast strains chosen because the epitope-tagged β or β′ are under control of their native promoters integrated in their respective chromosomal loci and therefore are not overexpressed. The yeast strain MHY346 contains a gene replacement of wt RNR4 by HA-RNR4, which encodes an N-terminally HA-tagged β′ that has been integrated into the endogenous RNR4 locus. The HAβ′ was isolated with anti-HA agarose from crude extract generated from MHY346. As shown in Figure 5B, a 1:1 complex of β/HAβ′ was isolated. To further confirm these results, the heterodimer was isolated from the yeast strain MHY343, which contains an exact insertion of a FLAG epitope encoding sequence at the 5′ end of the RNR2 open-reading frame in its chromosomal locus. Flagβ was purified using an anti-FLAG agarose resin, and again, a 1:1 Flagβ/β′ complex was isolated (Figure 5C). These results strongly support our in vitro observations that under these growth conditions holo-ββ′ does not undergo re-organization to form holo-β2 and β′2. Our data also strongly support the hypothesis that ββ′ is the active form of yeast R2 in vivo.

Figure 5.

Isolation of S. cerevisiae R2 using a variety of tagged β and β′ constructs. SDS–PAGE analysis of products purified using antibody-based affinity resin. (A) Anti-Myc agarose was utilized to isolate Mycβ′ overexpressed in the rnr4Δ strain. (B) Anti-HA agarose was utilized to isolate HAβ′ from MHY346 crude extracts. (C) Anti-FLAG agarose was utilized to isolate Flagβ from MHY343 crude extracts.

β′ Plays a Role in Cluster Assembly in Vivo

Having confirmed the predominant presence of ββ′ in vivo, we wanted to probe the role of β′ in generating active yeast R2. Previous studies have shown that RNR4 is essential for mitotic viability in the W303 strain background (6). However, two RNR4 deletion strains have been constructed with phenotypes of slow growth and cold sensitivity, demonstrating that β2 must be active in nucleotide reduction in the absence of β′2 (4, 5). Examination of these strains might give us insight about the mechanism of cell survival and specifically the ability of β2 to substitute for ββ′. Isogenic strains of wt and rnr4Δ were examined using quantitative Western blotting, whole-cell EPR spectroscopy, and activity assays to gain a better understanding of the phenotypic consequences of RNR4 deletion.

RNR subunit concentrations in wt and rnr4Δ strains were determined using quantitative Western blotting and are reported herein as the concentrations of protein monomer (α, β, α′, and β′). As shown in Figure 6 and Table 2, the RNR subunits, α, β, and α′, are all overexpressed in the rnr4Δ strain. β is expressed at a concentration of 0.8 ± 0.3 µM in this wt strain background. In the otherwise isogenic rnr4Δ strain, β is present at 14 ± 4 µM. Therefore, the β concentration increases roughly 15-fold upon deletion of RNR4. The expression levels of α and α′ are also increased in the rnr4Δ strain. The amount of α/cell increases ~2.5-fold, but because the cell volume of the rnr4Δ strain is larger than the wt strain, the concentration of α is 0.9 ± 0.3 µM, similar to that in the wt strain (0.8 ± 0.3 µM). α′ cannot be detected in wt extracts but is induced to a concentration of 1.8 ± 0.5 µM in the rnr4Δ strain.

Figure 6.

Quantitative Western blots to determine the concentration of β (A), α (B), and α′ (C) in wt and rnr4Δ strains. The nanogram of standard or microgram of crude extract loaded is indicated above each lane.

Table 2.

Summary of the Concentrations of the RNR Subunits in the wt and rnr4Δ Strains Determined by Quantitative Western Blotting and Y • Concentration Determined by Whole-Cell EPR

| strain | cell volume (fL) | [Y•] (µM) | [β] (µM) | [β′] (µM) | [α] (µM) | [α′] (µM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| wt (BY4741) | 41 | 0.8 ± 0.2 | 0.8 ± 0.3 | 0.5 ± 0.2 | 0.8 ± 0.3 | <0.03a |

| rnr4Δ | 68 | <0.05 | 14 ± 4 | 0.9 ± 0.3 | 1.8 ± 0.5 |

On the basis of the lower limit of detection at 1 ng in 10 µg of crude extract.

The effect of RNR4 deletion on the RNR activity was measured in cell extracts that have undergone polyethyleneimine and ammonium sulfate fractionation (25). Western blotting confirmed that this procedure did not remove α, β, and β′. This partial purification is essential for the detection of activity. Cell extracts prepared in this way typically have a specific activity of 0.06 ± 0.01 nmol min−1 mg−1 (inset of Figure 7). The addition of α (4 µM) to the extract results in a 60-fold increase in CDP reduction activity to 3.7 nmol min−1 mg−1, presumably because the endogenous ββ′ in the extract is saturated with α under these conditions. On the other hand, no activity was measurable in the rnr4Δ extracts, even after α was added to a final concentration of 6 µM (inset of Figure 7). Thus, the activity in the rnr4Δ strain extracts must be less than 0.01 nmol min−1 mg−1. Even though β is overexpressed in the rnr4Δ strain relative to the wt strain, the rnr4Δ extract has a specific activity that is at least 100-fold less that the activity of the wt extract.

Figure 7.

Assays of RNR activity in yeast extracts. The total nanomoles of dCDP produced as a function of time are plotted for the wt extract (□), wt extract supplemented with 4 µM α (■), rnr4Δ extract (○), and rnr4Δ extract supplemented with 6 µM α (●). The inset has the same data but on a different scale.

To understand the basis for the dramatic drop in RNR activity, a whole-cell EPR technique was used to measure the concentration of Y• in vivo. Harder and Follmann first reported the doublet signal associated with the Y• of S. cerevisiae R2 in extracts subjected to an ammonium sulfate fractionation (26). They noted that the signal could also be observed in whole cells. Figure 8 shows a comparison of purified Hisββ′ (A) and the EPR spectrum acquired from wt yeast cells (B). Double integration of this signal and a comparison to a standard curve of E. coli R2 Y•, as well as the assumption of a cell volume of 41 fL, allowed determination of the Y• concentration to be 0.8 ± 0.2 µM (20). The EPR spectrum acquired from the rnr4Δ cells is very different from that of the wt cells. No Y• could be detected above the background signal, and the line shape was reminiscent of the spectra acquired from wt yeast cells treated with hydroxyurea, a chemical that leads to the reduction of the Y• (data not shown). On the basis of our estimation of the lower limit of detection, the Y• concentration in the rnr4Δ strain must be at least 20-fold lower than in wt cells even though the β concentration is elevated approximately 15-fold. This observation explains why the strain lacking β′ has a dramatic decrease in RNR activity. These results demonstrate that β′ plays a crucial role in diferric-Y• assembly in β in vivo. Furthermore, they demonstrate that the measurement of the RNR protein concentration does not necessarily correlate with RNR activity in vivo.

Figure 8.

EPR spectra of pure Hisββ′ and whole yeast cells. (A) EPR spectrum of Hisββ′ (20 µM, 0.2 Y•/heterodimer) was acquired with 10 scans at a receiver gain of 1 × 105. All other EPR settings are as described in the Materials and Methods. (B) EPR spectrum of whole yeast cells (BY4741; 1.12 × 1010 cells/mL) was acquired with 32 scans at a gain of 1.78 × 105.

Re-examination of Diferric-Y• Assembly with Hisβ2 and Flagβ2

The above results indicate that β2 must be able to assemble a minimal amount of diferric-Y• cofactor and that this assembled protein must be able to interact with α to effect nucleotide reduction. On the basis of the doubling time of the rnr4Δ strain, the concentration of the β and the size of the yeast genome, β2, must have a minimal specific activity of 5 nmol min−1 mg−1 to support DNA replication. Thus, we re-examined the Y• content and specific activity of Hisβ2, which we previously reported was inactive in nucleotide reduction (9), under conditions that would allow for detection of low amounts of Y• and activity. The reconstitution was completed on a larger scale than in previous experiments to give a sufficiently high concentration of Hisβ2 for Y• content determination, and the CDP utilized in the nucleotide reduction assay had a high specific activity (~7000 cpm/nmol) relative to that routinely used for Hisββ′ assays (~2000 cpm/nmol). After reconstitution by our standard procedures, Hisβ2 was assayed for activity and monitored for Y• and was found to have a specific activity of 10 nmol min−1 mg−1, 250-fold less than the specific activity of Hisββ′, and 0.004 Y•/β2.

To further confirm the activity of β2, a yeast strain was constructed, which contained FLAG-RNR2 at the RNR2 locus and an rnr4Δ deletion. The Flagβ2 could be isolated from this strain in sufficient quantities to be assayed with α. This protein had a specific activity of 2 nmol min−1 mg−1. Thus, β2 with either an N-terminal FLAG or His tag has low but measurable activity. These results together explain how the rnr4Δ strain can be viable. In this strain, a small fraction of the β2 present has an assembled diferric-Y• cofactor. Thus, this small amount of holo-β2 must be sufficient to support the replication of DNA in the rnr4Δ strain. Furthermore, the low specific activity of β2 in vitro and in vivo supports our hypothesis that the heterodimer is the predominant form of yeast R2.

Cotranslation of β and β′ Is Not Required To Obtain Soluble β in Vivo

The proposal of Thelander and co-workers that β′ is a folding chaperone for β led to the suggestion that β and β′ need to be cotranslated to generate soluble folded ββ′ (8). This hypothesis makes a prediction that β2 expressed in the rnr4Δ strain has a defect in cluster assembly because of improper folding. We tested the ability of β2 in the rnr4Δ strain to form a heterodimer using HAβ′2 as a probe of its folding state. Increasing amounts of crude extracts from the rnr4Δ strain were mixed with HAβ′2 (8 µg or 200 pmol of HAβ′). The mixture was subsequently immunoprecipitated with anti-HA agarose, and the products were analyzed by SDS–PAGE. As revealed in Figure 9, β co-immunoprecipitated with HAβ′. Furthermore, as increasing amounts of rnr4Δ extract were added, the band corresponding to β increased in intensity until the band for β was roughly equal in intensity to that of HAβ′. Because the amount of β present per microgram of rnr4Δ extract has been determined previously using quantitative Western blotting, the amount of β present in each immunoprecipitation experiment can be estimated. The results are listed above each lane in Figure 9. These calculations reveal that the immunoprecipitation experiment shown in Lane 4 contains sufficient quantities of β in the rnr4Δ extract to quantitatively form βHAβ′, and thus, a stoichiometric amount of β co-immunoprecipitates with HAβ′. Because the majority of β in the rnr4Δ extract is capable of generating βHAβ′, we conclude that β2 can fold in the absence of β′2 and is capable of forming an apo-ββ′ if β′2 is present. Furthermore, consistent with our in vitro observations, when the wt crude extract was used instead of the rnr4Δ extract, no β was found to co-immunoprecipitate with HAβ′, thus demonstrating that the holo-ββ′ does not exchange its protomers (data not shown).

Figure 9.

SDS–PAGE analysis of co-immunoprecipitation of HAβ′ and β from the rnr4Δ crude extracts. Crude extract was generated from the rnr4Δ strain, and increasing amounts of the extract was mixed with 200 pmol of HAβ′, which was subsequently immunoprecipitated using anti-HA agarose. The total amount of β in each immunoprecipitation experiment, estimated from quantitative Western blotting, is indicated above each lane.

DISCUSSION

Several lines of genetic and biochemical evidence have led to the proposal that the active form of the yeast R2 is ββ′. Deletion of RNR4 leads to the loss of viability or slow growth and cold sensitivity, suggesting an important role of β′ (4−6). Previous biochemical studies revealed that ββ′ containing 0.3–0.4 equiv of diferric-Y• cofactor could be isolated and is active in nucleotide reduction with α (7, 8). In contrast, while β2 and β′2 could be isolated, they had no detectable di-iron cofactor and consequently no detectable activity in the nucleotide reduction assay. While our previous studies demonstrated an interaction between β and β′ by their co-immunoprecipitation from crude extracts, the stoichiometry between β and β′ was not reported (6, 9). All of these observations are consistent with the heterodimer model. However, they also could support a model in which β′ is needed in the assembly of diferric-Y• in β and that reorganization of holo-ββ′ to active β2 requires other factors not present in the in vitro reconstitution experiments.

Our in vitro and in vivo results reported here further establish the relevance of the heterodimer observed in vitro to the active form of yeast R2 in vivo. Using several epitope-tagged R2s expressed in yeast under control of their endogenous promoters, we demonstrate that β and β′ can be purified from crude cell extracts in a 1:1 molar ratio. A comparison of wt and rnr4Δ strains by a number of methods suggests that β′ is critical to the assembly of di-iron Y• cofactor in β. The viability of the rnr4Δ strains is explained by the dramatic upregulation of the concentration of β and the ability of β2 to self-assemble the cluster at levels that are 250-fold lower than that of the wt but sufficient for cell survival. Finally, our in vitro exchange reactions suggest that holo-ββ′ is unlikely to reorganize to form active β2.

While these results establish that ββ′ is the active form of R2 in vivo, they do not define the role of β′. Thelander and co-workers have proposed that the function of β′ is to correctly fold and stabilize β and that these two proteins must be cotranslated for efficient heterodimer formation to occur (8). Our results do not support this hypothesis. We observed rapid formation of the heterodimer when Hisβ2 and β′2 are mixed at physiological concentrations, which would not occur if Hisβ2 was misfolded. We have also shown that apo-Hisβ2 is unstable, a characteristic associated with all apo-R2s, and prone to aggregation and proteolysis. Thus, the exchange studies with Hisβ2 may be disputed as the tag apparently stabilizes the protein in some fashion. However, we have also demonstrated that nontagged β2 present in crude extracts generated from a rnr4Δ strain is capable of participating in the same exchange reaction to form the heterodimer, further supporting the relevance of our exchange reaction studies in vitro. Moreover, we have established that most of β2 present in the crude extract is capable of forming a heterodimer with β′2, arguing against a model that only a small fraction of β2 is properly folded. The cells have some mechanism to stabilize apo-β2 in the absence of β′ in the rnr4Δ. These data together suggest that cotranslation of β and β′ is not essential.

Previously, we have proposed that β′2 is a catalytic iron chaperone, required transiently in the cofactor assembly of β2, similar to the role proposed for Ccs1, the copper chaperone for copper zinc superoxide dismutase (10−12). However, our previous findings that β′2 was needed in stoichiometric amounts to activate β2 and that no iron could be detected bound to β′2 are inconsistent with this proposal (7). Furthermore, the results presented here demonstrate that ββ′ is the predominant species in vivo, which does not support the proposal that β′2 is needed catalytically in the activation of β.

Our recent structures of Hisβ2, β′2, and Hisββ′ have suggested an alternative role for β′ to stabilize a local conformation of β2 that would promote cofactor assembly (13, 14). Specifically, helix αB of β2, harboring the di-iron cluster ligand Asp145, becomes ordered upon heterodimer formation. The observation that the rnr4Δ strain overexpresses β2 by 15-fold yet has significantly less Y• and RNR activity than the wt strain supports the hypothesis that β′ is required for the cofactor assembly in ββ′ in vivo. Furthermore, our observations that tagged-β2 can assemble small amounts of the cofactor in the absence of β′ supports our hypothesis that a majority of β2 in solution is in a conformation that cannot efficiently assemble the cofactor.

As we learn more about the insertion of metals into enzyme active sites in vivo, it is becoming clear that in the case of copper, nickel, zinc, and iron (for iron–sulfur clusters), metallochaperones are required to deliver the metal and perhaps required reducing equivalents in a regulated fashion to assemble holo-metalloproteins (10, 27, 28). Perhaps the role of β′ in vivo is to stabilize β to allow for cofactor assembly as proposed above or to facilitate interactions with the cellular machinery required for cofactor insertion. We have shown with the rnr4Δ strain studies that the cell must sense this defect in RNR activity, likely through activation of the DNA damage checkpoint by replicational stress resulting from low concentrations of deoxynucleotides (29, 30), and responds to it through upregulation of α and α′ concentrations in addition to a dramatic upregulation of the β concentration. Perhaps, the cell also upregulates the machinery required for cofactor insertion, thus setting the stage for us to use this strain to search for the RNR iron chaperone protein(s).

Footnotes

D.L.P. and A.D.O. were supported in part by the NIH training grant 5T32 CA 09112-28. J.S. acknowledges support of the NIH (GM29595). M.H. acknowledges support of the NIH (CA095207) and the ACS (0305001GMC).

Abbreviations: Abs, antibodies; AEBSF, 4-(2-aminoethyl)benzenesulphonyl fluoride; α, polypeptide encoded by RNR1; α′, polypeptide encoded by RNR3; β, polypeptide encoded by RNR2; β′, polypeptide encoded by RNR4; CD, circular dichroism; DSC, differential scanning calorimetry; E-64, (2S,3S)-3-(N-{(S)-1-[N-(4-guanidinobutyl)carbamoyl] 3-methylbutyl}carbamoyl)oxirane-2-carboxylic acid; FT, flow through; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; R1, ribonucleotide reductase large subunit; R2, ribonucleotide reductase small subunit; RNR1 and RNR3, yeast RNR large subunit genes; RNR2 and RNR4, yeast RNR small subunit genes; RNR, ribonucleotide reductase; SC-Ura, synthetic complete media without uracil; wt, wild type; Y•, tyrosyl radical; Y1, α; Y2, β2; Y3, α′; Y4, β′2.

The nomenclature for naming the yeast RNR proteins differs from that in our previous publications in an effort to clarify the quaternary structures of these subunits.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jordan A, Reichard P. Ribonucleotide reductases. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1998;67:71–98. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Elledge SJ, Davis RW. Identification and isolation of the gene encoding the small subunit of ribonucleotide reductase from Saccharomyces cerevisiae—DNA damage-inducible gene required for mitotic viability. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1987;7:2783–2793. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.8.2783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hurd HK, Roberts CW, Roberts JW. Identification of the gene for the yeast ribonucleotide reductase small subunit and its inducibility by methyl methanesulfonate. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1987;7:3673–3677. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.10.3673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Winzeler EA, Shoemaker DD, Astromoff A, Liang H, Anderson K, Andre B, Bangham R, Benito R, Boeke JD, Bussey H, Chu AM, Connelly C, Davis K, Dietrich F, Dow SW, El Bakkoury M, Foury F, Friend SH, Gentalen E, Giaever G, Hegemann JH, Jones T, Laub M, Liao H, Liebundguth N, Lockhart DJ, Lucau-Danila A, Lussier M, M’Rabet N, Menard P, Mittmann M, Pai C, Rebischung C, Revuelta JL, Riles L, Roberts CJ, Ross-MacDonald P, Scherens B, Snyder M, Sookhai-Mahadeo S, Storms RK, Veronneau S, Voet M, Volckaert G, Ward TR, Wysocki R, Yen GS, Yu KX, Zimmermann K, Philippsen P, Johnston M, Davis RW. Functional characterization of the S. cerevisiae genome by gene deletion and parallel analysis. Science. 1999;285:901–906. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5429.901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang PJ, Chabes A, Casagrande R, Tian XC, Thelander L, Huffaker TC. Rnr4p, a novel ribonucleotide reductase small-subunit protein. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1997;17:6114–6121. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.10.6114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huang MX, Elledge SJ. Identification of RNR4, encoding a second essential small subunit of ribonucleotide reductase in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1997;17:6105–6113. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.10.6105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ge J, Perlstein DL, Nguyen HH, Bar G, Griffin RG, Stubbe J. Why multiple small subunits (Y2 and Y4) for yeast ribonucleotide reductase? Toward understanding the role of Y4. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2001;98:10067–10072. doi: 10.1073/pnas.181336498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chabes A, Domkin V, Larsson G, Liu AM, Graslund A, Wijmenga S, Thelander L. Yeast ribonucleotide reductase has a heterodimeric iron-radical-containing subunit. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2000;97:2474–2479. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.6.2474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nguyen HHT, Ge J, Perlstein DL, Stubbe J. Purification of ribonucleotide reductase subunits Y1, Y2, Y3, and Y4 from yeast: Y4 plays a key role in diiron cluster assembly. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1999;96:12339–12344. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.22.12339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Finney LA, O’Halloran TV. Transition metal speciation in the cell: Insights from the chemistry of metal ion receptors. Science. 2003;300:931–936. doi: 10.1126/science.1085049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huffman DL, O’Halloran TV. Function, structure, and mechanism of intracellular copper trafficking proteins. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2001;70:677–701. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.70.1.677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rae TD, Schmidt PJ, Pufahl RA, Culotta VC, O’Halloran TV. Undetectable intracellular free copper: The requirement of a copper chaperone for superoxide dismutase. Science. 1999;284:805–808. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5415.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sommerhalter M, Voegtli WC, Perlstein DL, Ge J, Stubbe J, Rosenzweig AC. Structures of the yeast ribonucleotide reductase Rnr2 and Rnr4 homodimers. Biochemistry. 2004;43:7736–7742. doi: 10.1021/bi049510m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Voegtli WC, Ge J, Perlstein DL, Stubbe J, Rosenzweig AC. Structure of the yeast ribonucleotide reductase Y2Y4 heterodimer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2001;98:10073–10078. doi: 10.1073/pnas.181336398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yao RJ, Zhang Z, An XX, Bucci B, Perlstein DL, Stubbe J, Huang MX. Subcellular localization of yeast ribonucleotide reductase regulated by the DNA replication and damage checkpoint pathways. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2003;100:6628–6633. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1131932100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sikorski RS, Hieter P. A system of shuttle vectors and yeast host strains designed for efficient manipulation of DNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1989;122:19–27. doi: 10.1093/genetics/122.1.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elledge SJ, Richman R, Hall FL, Williams RT, Lodgson N, Harper JW. Cdk2 encodes a 33-kDa cyclin-A-associated protein kinase and is expressed before Cdc2 in the cell cycle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1992;89:2907–2911. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.7.2907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Longtine MS, McKenzie A, Demarini DJ, Shah NG, Wach A, Brachat A, Philippsen P, Pringle JR. Additional modules for versatile and economical PCR-based gene deletion and modification in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 1998;14:953–961. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(199807)14:10<953::AID-YEA293>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bollinger JM, Tong WH, Ravi N, Huynh BH, Edmondson DE, Stubbe J. Use of Rapid Kinetics Methods to Study the Assembly of the Diferric-Tyrosyl Radical Cofactor of Escherichia coli Ribonucleotide Reductase. Redox-Active Amino Acids in Biology. 1995:278–303. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(95)58052-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Perlstein DL, Robblee J, Huang MX, Stubbe J. Quantitation of metallocofactor stoichiometry in vivo—Isolation of yeast’s endogenous ribonucleotide reductase small subunit. Biochemistry. 2005 in preparation. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jorgensen P, Nishikawa JL, Breitkreutz BJ, Tyers M. Systematic identification of pathways that couple cell growth and division in yeast. Science. 2002;297:395–400. doi: 10.1126/science.1070850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gietz RD, Schiestl RH. Transforming yeast with DNA. Method Mol. Cell. Biol. 1995;5:255–269. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Steeper JR, Steuart CD. A rapid assay for CDP reductase activity in mammalian cell extracts. Anal. Biochem. 1970;34:123–130. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(70)90092-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dyson HJ, Wright PE. Intrinsically unstructured proteins and their functions. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2005;6:197–208. doi: 10.1038/nrm1589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lammers M, Follmann H. Deoxyribonucleotide biosynthesis in yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) a ribonucleotide reductase system of sufficient activity for DNA synthesis. Eur. J. Biochem. 1984;140:281–287. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1984.tb08099.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harder J, Follmann H. Identification of a free-radical and oxygen dependence of ribonucleotide reductase in yeast. Free Radical Res. Commun. 1990;10:281–286. doi: 10.3109/10715769009149896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kuchar J, Hausinger RP. Biosynthesis of metal sites. Chem. Rev. 2004;104:509–525. doi: 10.1021/cr020613p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rosenzweig AC, O’Halloran TV. Structure and chemistry of the copper chaperone proteins. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2000;4:140–147. doi: 10.1016/s1367-5931(99)00066-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Elledge SJ, Zhou Z, Allen JB, Navas TA. DNA damage and cell cycle regulation of ribonucleotide reductase. BioEssays. 1993;15:333–339. doi: 10.1002/bies.950150507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhou BBS, Elledge SJ. The DNA damage response: Putting checkpoints in perspective. Nature. 2000;408:433–439. doi: 10.1038/35044005. BI051616+ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]