Clinical vignette

A 47-year-old gentleman presented with an incidental discovery of a 2.5-cm anterior mediastinal mass. Following radiological review, the diagnosis of likely thymoma is made and the patient is referred for surgical resection. The patient is currently self-employed and working as a carpenter. He is very concerned about the possibility of having a sternotomy as it would impact on his recovery and return to work. A single port, muscle sparing technique seems the best option for this gentleman. He undergoes surgery and is discharged 2 days later. He is back at work in 2 weeks.

Over the past 10 years, video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS) has replaced median sternotomy for the resection of anterior mediastinal masses, including thymoma. In 1993, the thoracoscopic approach to thymectomy was first reported by Sugarbaker from Boston, as well as a Belgian group (1,2). To date, the VATS approach has become the preferred and standard operation for the treatment of thymic disease. Numerous studies confirmed that, compared to standard sternotomy, VATS thymectomy results in less post-operative pain, better preserved pulmonary function, improved cosmesis (which can be particularly important to many young female myasthenia gravis patients) and is oncologically feasible for non-invasive thymomas as long as en bloc resection of the tumor is achieved (3-5). Most published reports regarding this procedure have focused on the right-sided approach, which has been adopted by most surgeons as the space in the right chest cavity is relatively large, with little interference from the heart, and the superior vena cava acts as an anatomical landmark. The current trend is to reduce the number of ports and minimize the length of incisions to further decrease postoperative pain, chest wall paresthesia, and length of hospitalization. Single-port thoracoscopy for mediastinal mass resection is not new. In our early experience with uniportal VATS thymectomy, we adopted the use of a singular access device (SILS port, Covidien) that permits the insertion of three or four instruments, together with CO2 insufflation, through a right-sided single 3-cm incision, without rib spreading.

Surgical technique

Patient selection

Non-thymomatous myasthenia gravis;

Small (<2 cm) intrathymic thymoma;

Large well-encapsulated thymoma (preferably <4 cm);

Minimally invasive thymoma.

Preparation

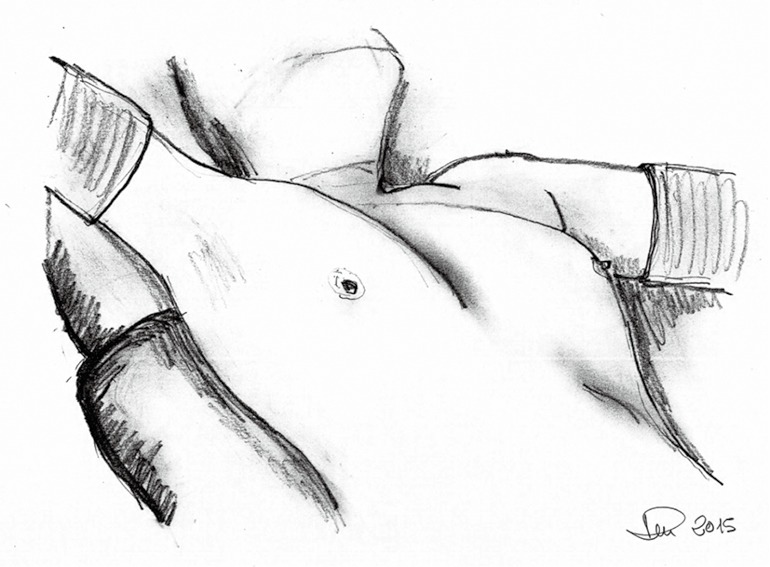

The patient is positioned in a 30-degree semi-supine position with a roll placed under the right shoulder, and the ipsilateral arm is held abducted over a padded L-shaped bar to expose the axilla (Figure 1). The pulse oximeter is placed on the right hand fingers to check for signs of potential ischemia due to the bandages being too tight. The left arm is held extended on a padded board. This approach allows access to the left side if required.

Figure 1.

Patient position.

The right side is the preferred approach for non-thymomatous myasthenia gravis, especially in small females, as there is more room for manipulation with the heart out of the way, and the anatomical landmarks (phrenic nerve, superior vena cava and innominate vein) are easily identifiable. The left-sided approach is used whenever a thymoma is located exclusively on that side. The surgeon and the assistant stand on the same side while the scrub nurse stands on the opposite side.

Operative steps

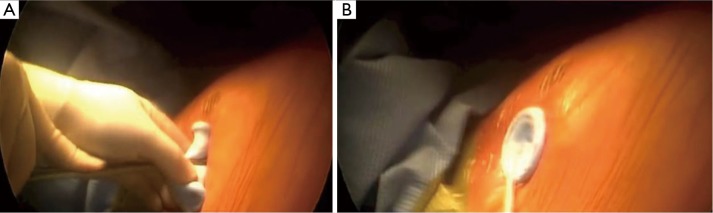

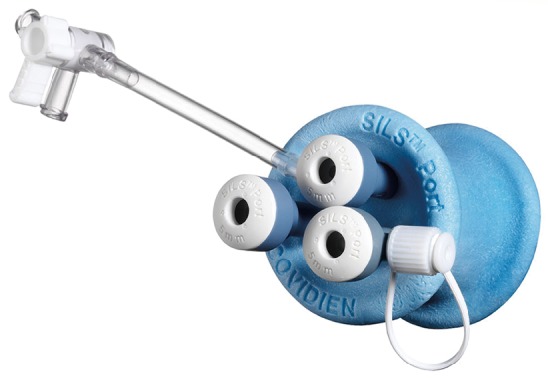

A right-sided 3 cm lateral muscle-sparing incision is made at the fifth intercostal space. The Single Incision Laparoscopic Surgery (SILS) Port device (Covidien) (Figure 2) is then gently inserted trough the intercostal space without rib spreading (Figure 3). The SILS port is a flexible laparoscopic port that can accommodate up to three instruments through a single port.

Figure 2.

The Single Incision Laparoscopic Surgery (SILS) Port device.

Figure 3.

(A) The SILS Port device (Covidien) is gently inserted through a right-sided 3-cm lateral muscle-sparing incision; (B) when the device is perfectly adherent to the skin, CO2 insufflation starts. SILS, Single Incision Laparoscopic Surgery.

When the device is perfectly adherent to the skin, we start insufflating carbon dioxide (CO2) with a 6 L/min flow and 8mmHg pressure. CO2 insufflation is used to help collapse the lung and to aid in dissection of the fat plane, effectively creating a pneumomediastinum. Carbon dioxide insufflation is continued throughout the procedure as an aid to dissection. We then introduce through the port a 5-mm camera, 30° lens, for mediastinal inspection and to confirm that the lesion is resectable.

There is usually no need for any lung retraction. The right phrenic nerve is seen coursing superior and lateral on the superior cava vein. The internal mammary artery vein and artery are the superior extent of dissection. In all cases the dissection starts from the pericardial fat plane and then carried out superiorly to identify the anonymous vein. We always use the LigaSure device (5-mm blunt 37 length, Covidien) for tissue dissection and small vessel division.

Dissection starts from the inferior border at the pericardial reflection, proceeding lateral to medial across the midline. When the left pleura and left phrenic nerve are reached, the dissection is directed cranially, parallel to the nerve. Once the pleural dissection has been completed in the thymus is mobilized and retracted laterally and dissected off of the underlying pericardium. The bilateral upper gland is then stripped down from the neck in order to reveal the thymic vein. The removed thymus and fat tissue is finally placed in a specimen bag and taken out.

At the end of the procedure, we introduce a 28 French chest tube through the same incision (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Uniportal video-assisted thoracic surgery thymectomy (6). Available online: http://www.asvide.com/articles/726

Comment

Clinical results

From June 2013 to May 2015, 11 uniportal VATS thymectomies were performed. All patients were approached from the right side. Mean age was 67 years (range, 38-78 years), mean duration of surgery was 54 minutes, and mean duration of hospital stay was 2.1 days. There was no hospital mortality and operative morbidity was represented by hoarse voice in a patient with a mediastinal schawannoma in the station 5 position.

Tips and considerations

Though most surgeons use three ports, the results of our initial experience showed that the uniportal approach is a safe procedure and oncologically feasible for non-invasive thymomas.

Uniportal VATS thymectomy for thymoma should be generally confined to small intrathymic and encapsulated tumors, due to oncological concerns of possible breach of the tumor capsule with the risk of tumour seeding.

From our experience with uniportal VATS, we encountered several strategies that we felt enhanced the conduct of the operation and helped minimize the risk of capsular breakage and tumour seeding:

Well-encapsulated tumours screened on thoracic computed tomography scan are ideal for the uniportal approach. We always perform a magnetic resonance image of the chest to identify the content of the lesion (cystic versus solid) and potential involvement of surrounding structures;

Tumors >4-mm in diameter and radiological suspicion of brachiocephalic vein invasion should be excluded from the uniportal approach;

The tumor should be approached from the ipsilateral side (right/left approach) so that dissection is performed under direct vision. However, for midline masses, we always recommend the right-sided approach;

The tumor should be dissected last, using a no-touch technique. The non-tumourous part of the gland is always dissected first and used for grasping and traction when dissecting the tumor, thus avoiding touching or grasping the tumour capsule.

The use of the SILS port device is “effective” and safe and facilitates mediastinal mass resection without the need for extra incisions. Dedicated instruments such as the Kymerax Precision-Drive Articulating Surgical System (robotic instrument enabled precise instrument articulation and control) can be used to increase ergonomy and reach within the chest. This robotic aid should be considered for more complex procedures, but we do not consider it necessary for localized lesions.

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Sugarbaker DJ. Thoracoscopy in the management of anterior mediastinal masses. Ann Thorac Surg 1993;56:653-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coosemans W, Lerut TE, Van Raemdonck DE. Thoracoscopic surgery: the Belgian experience. Ann Thorac Surg 1993;56:721-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ng CS, Wan IY, Yim AP. Video-assisted thoracic surgery thymectomy: the better approach. Ann Thorac Surg 2010;89:S2135-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rückert JC, Walter M, Müller JM. Pulmonary function after thoracoscopic thymectomy versus median sternotomy for myasthenia gravis. Ann Thorac Surg 2000;70:1656-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheng YJ, Kao EL, Chou SH. Videothoracoscopic resection of stage II thymoma: prospective comparison of the results between thoracoscopy and open methods. Chest 2005;128:3010-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scarci M, Pardolesi A, Solli P. Uniportal video-assisted thoracic surgery thymectomy. Asvide 2015;2:149. Available online: http://www.asvide.com/articles/726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]