Abstract

Conformational dynamics of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) spike glycoprotein (S) mediate exposure of the binding site for the cellular receptor, angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2). The N-terminal domain (NTD) of S binds terminal sialic acid (SA) moieties on the cell surface, but the functional role of this interaction in virus entry is unknown. Here, we report that NTD-SA interaction enhances both S-mediated virus attachment and ACE2 binding. Through single-molecule Förster resonance energy transfer imaging of individual S trimers, we demonstrate that SA binding to the NTD allosterically shifts the S conformational equilibrium, favoring enhanced exposure of the ACE2-binding site. Antibodies that target the NTD block SA binding, which contributes to their mechanism of neutralization. These findings inform on mechanisms of S activation at the cell surface.

Host sialic acids promote the open conformation of SARS-CoV-2 S receptor binding domain to facilitate ACE2 binding.

INTRODUCTION

The etiologic agent of the COVID-19 pandemic is the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) (1). SARS-CoV-2 binds the cellular receptor, angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), through its envelope glycoprotein spike (S), which subsequently enables entry into the host cell by promoting fusion of viral and cellular membranes (2–10). The viral spike is a trimer of heterodimers with each protomer consisting of S1 and S2 subunits. The S1 subunit contains the receptor binding domain (RBD), which includes the ACE2 receptor binding motif (RBM). The S2 subunit forms the stalk of the spike, which undergoes a large-scale refolding during membrane fusion (11–14). The importance of other spike domains during virus entry into cells, such as the N-terminal domain (NTD) of S1, is less well established. Neutralizing monoclonal antibodies (mAb) that target the NTD, such as mAb 4A8, suggest a biological relevance for the NTD in infection (15–17). Moreover, the NTD may play a critical role in allosterically regulating proteolysis of S during entry into cells (18–20).

Structures of soluble trimeric S ectodomains identified two prefusion conformations in which the RBD adopts either a “down” or an “up” position (6, 8, 21–25). The RBM is occluded in the RBD-down conformation, suggesting that transition to the RBD-up position is required for binding ACE2. Structures of S bound to ACE2 showing the RBD in the up conformation support this hypothesis (10). Furthermore, real-time analysis of the conformational dynamics of S through single-molecule Förster resonance energy transfer (smFRET) imaging corroborated the structural data (26–28). Analysis of the kinetics of conformational transitions indicated that ACE2 does not induce movement of the RBD but, rather, captures the RBD-up conformation (28). This observation suggests that promoting the RBD-up conformation might increase ACE2 binding.

In addition to interaction with ACE2, some reports have demonstrated that the RBD binds heparan sulfate oligosaccharides, ABH blood group antigens, and monosialylated gangliosides (29–35). In contrast, other studies have shown low or undetectable binding between the RBD and carbohydrates (36–38). Therefore, the existence of RBD-carbohydrate interactions remains controversial. Computational approaches also suggested the existence of sialoside-binding motifs in the NTD that can bind to 5-acetylneuraminic acid (Neu5Ac) present in compounds like ganglioside GM1 and α2,3- and α2,6-linked sialyl N-acetyllactosamines (39–42). Experimental studies have since provided direct evidence in support of a sialoside-binding site in the NTD (36, 43–45). These studies presented the possibility that SARS-CoV-2 may exploit glycans on the cell surface to aid in attachment. Support for this hypothesis came from a study in which depletion of sialic acid (SA) levels on ACE2-expressing cells through genetic, pharmacological, or enzymatic approaches decreased RBD binding and entry of SARS-CoV-2 virions (35). Similarly, atomic force microscopy demonstrated that synthetic multimeric SA glycoclusters could decrease S-pseudotyped virus binding to model cell lines (46). Moreover, inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 infection in a nonhuman cell line by α2,6- sialoside compounds, but not by the α2,3- analog, was reported. Consistently, binding of SARS-CoV-2 spike S1 subunit to the same cells was competitively inhibited by α2,6-linked sialosides (47). Despite these findings, which in general support a role for S interaction with sialylated glycans during SARS-CoV-2 attachment to host cells, the interplay and relative contributions of SA and ACE2 binding has not been elucidated.

In this study, we explore the role of the NTD during early interactions with the host cell. Our data further support a role for the NTD in mediating SARS-CoV-2 attachment to cells through engagement with SA on the cell surface, which is blocked by NTD-targeting mAb 4A8. In addition, we demonstrate that SA binding to the NTD stimulates subsequent interaction of S with ACE2. The mechanistic basis for this phenomenon is provided by smFRET imaging of trimeric S ectodomains, which indicates that the SA-NTD interaction shifts the equilibrium of RBD toward the up position, thus promoting exposure of the ACE2-binding site (28). Overall, our findings support a critical role for the NTD in enabling initial attachment of SARS-CoV-2 to the cell surface and promoting subsequent engagement with ACE2.

RESULTS

Soluble SA compounds enhance S-mediated SARS-CoV-2 entry

We first sought to verify the role of SA during infection of cells with SARS-CoV-2 S–pseudotyped virus. We formed pseudotyped virions with SARS-CoV-2 S and the HIV-1 core containing a luciferase reporter gene. The pseudovirions were then used to infect 293T cells that stably express both human ACE2 and TMPRSS2 (293T-ACE2.TMPRSS2; fig. S1A) (48, 49). We incubated the pseudovirions with different concentrations (0 to 1.5 mM) of either dextrose [a non-carboxylated monosaccharide with inert binding properties to SARS-CoV-2 S (35)], Neu5Ac, or α2,3- or α2,6-linked sialylated oligosaccharides [sialosides; LS-tetrasaccharides a (LSTa) or LSTc, respectively] (Fig. 1A). Preincubation with dextrose had no effect on pseudovirus infectivity. Preincubation with the SA-containing compounds resulted in statistically significant increases in infectivity at concentrations up to 150 μM (Fig. 1A and fig. S1B). Concentrations greater than 150 μM inhibited infection, with complete inhibition seen at 1.5 mM LSTa and LSTc (Fig. 1A). We also evaluated the infectivity of pseudovirions incubated with different concentrations (0.14 to 1.4 μM) of a monomeric, soluble human ACE2 (shACE2, fig. S1C). As expected, incubation of pseudovirions with 1.4 μM shACE2 resulted in more than twofold reduction in infectivity (fig. S1C), irrespective of the absence or presence of 150 μM SA (fig. S1D) (50, 51). To distinguish the relative importance of SA on the cell surface from exogeneous SA-containing compounds during SARS-CoV-2 S–mediated entry, we repeated the infectivity experiments with 293T-ACE2.TMPRSS2 cells pretreated with neuraminidase (NA) to remove cell-surface SA. Treatment of cells with NA resulted in 18 ± 5% decrease in pseudovirus infectivity compared with untreated cells (fig. S1, E and B). Preincubation of pseudovirions with 150 μM Neu5Ac, LSTa, or LSTc increased infectivity nearly to the level seen in cells not treated with NA, whereas dextrose again had no effect (Fig. 1B). Here again, preincubation with shACE2 reduced infectivity of NA-treated cells (fig. S1F). These data demonstrate that the interaction of cellular SA with SARS-CoV-2 S enhances infectivity, in agreement with previous reports (46, 47). Furthermore, the dependence on ACE2 is maintained irrespective of the presence of SA.

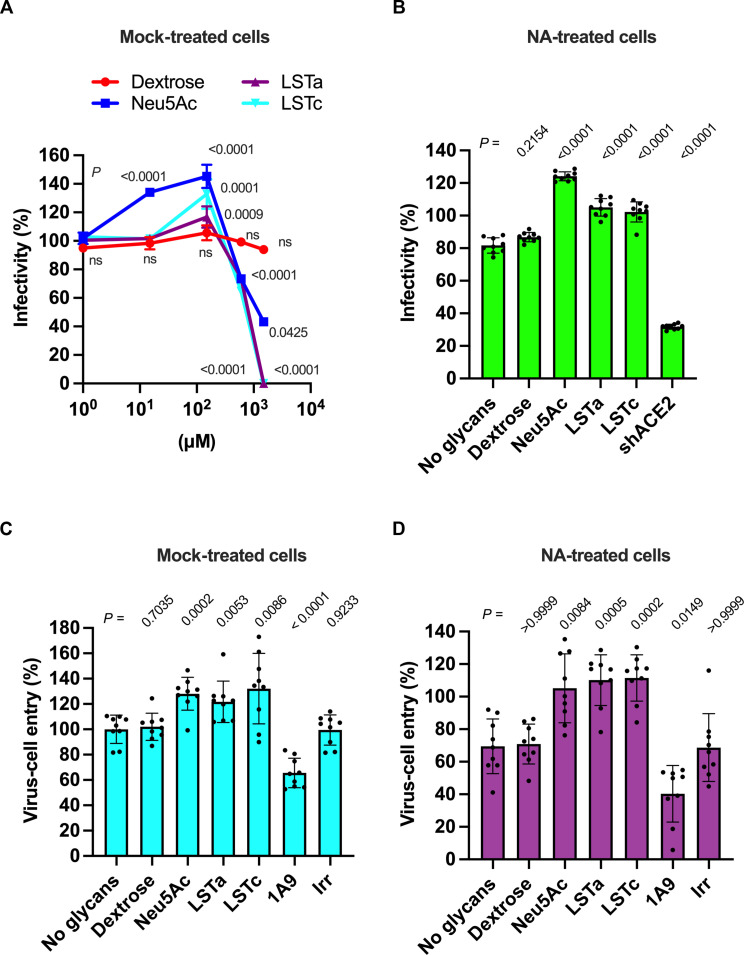

Fig. 1. SA enhances SARS-CoV-2 S–mediated infectivity and virus entry.

(A) Quantification of pseudovirion infectivity in 293T-ACE2.TMPRSS2 cells using a luciferase reporter. Particles were incubated with the indicated glycan concentrations before inoculation of cells. (B) Pseudovirion infectivity in 293T-ACE2.TMPRSS2 cells pretreated with NA to remove cell-surface terminal SAs. Viral particles were preincubated with 150 μM of the indicated glycan or 1.4 μM shACE2 before inoculation of cells. (C) Quantification of pseudovirion entry into 293T-ACE2.TMPRSS2 cells using a BlaM reporter (52). Particles were incubated with 150 μM of the indicated glycan or with 125 nM of the indicated mAb. As a negative control for mAb-mediated inhibition of virus entry, irrelevant (Irr) mAb was included. (D) Pseudovirion entry in 293T-ACE2.TMPRSS2 cells pretreated with NA. Pseudovirions were preincubated as in (C). In all cases, infectivity or virus entry are presented as a percentage of that seen in the case of mock preincubation without glycan, shACE2, or mAb. Individual values, the arithmetic means, and SDs of three independent experiments performed in triplicate are shown. Statistical significance was evaluated through one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. P values are shown, and those <0.05 were considered statistically significant. ns, not significant.

We next focused on the importance of SA during virus entry. We used a virus entry assay using pseudovirions containing β-lactamase (BlaM) fused to the HIV-1 Vpr protein (fig. S1G) (52). Consistent with the infectivity measurements, pseudovirions preincubated with 150 μM Neu5Ac, LSTa, or LSTc resulted in 28 ± 4%, 22 ± 5%, and 32 ± 9% increase in virus entry into 293T-ACE2.TMPRSS2 cells, respectively, while dextrose had no effect (Fig. 1C). Preincubation of pseudovirions with 125 nM of mAb 1A9, which inhibits membrane fusion driven by SARS-CoV S (53), decreased virus entry by 34 ± 4% (Fig. 1C), confirming that the observed virus entry was mediated by S. Treatment of cells with NA resulted in approximately 30% reduction of virus entry (fig. S1H), which was recovered through incubation of pseudovirions with Neu5Ac, LSTa, or LSTc (Fig. 1D). Together, these data indicate that SA can increase infectivity by enhancing S-mediated virus entry into 293T-ACE2.TMPRSS2 cells.

SARS-CoV-2 S mediates virus-cell attachment through interaction with SA

The apparent role of SA in promoting S-mediated entry into cells led us to hypothesize that SA might be facilitating attachment of virions to the cell surface. We produced pseudovirions with SARS-CoV-2 S and the HIV-1 core containing green fluorescent protein (GFP) (fig. S2A). To determine whether S can mediate attachment to cells lacking ACE2, we incubated GFP-containing pseudovirions with 293T cells on ice. We removed unbound virus and quantified GFP fluorescence, which indicated viral attachment to cells (fig. S2B). To test the role of SA in the observed virus attachment, we preincubated the pseudovirus with different concentrations (0 to 1.5 mM) of dextrose, Neu5Ac, LSTa, or LSTc before incubation with the 293T cells (Fig. 2A). Treatment with SA-containing compounds resulted in concentration-dependent inhibition of virus-cell binding, with approximately 50% reduction at 150 μM to nearly complete inhibition at higher concentrations (up to 1.5 mM, Fig. 2A). Specifically, the treatment with 150 μM Neu5Ac reduced virus attachment by 53 ± 5%, while the same concentration of LSTa and LSTc reduced virus attachment by 56 ± 15% and 62 ± 11%, respectively (Fig. 2A and fig. S2C). In contrast, neither preincubation with dextrose nor shACE2 had any effect on virus attachment to 293T cells (fig. S2, C and D). Last, pretreatment of cells with NA reduced virus attachment by 60% (Fig. 2B and fig. S2, E and F). These data indicate that SA can enable S-mediated virus attachment to the cell surface in the absence of ACE2. Furthermore, the similarity in the results involving LSTa and LSTc indicate that the glycosidic linkage of the SA is not a determinant of the interaction.

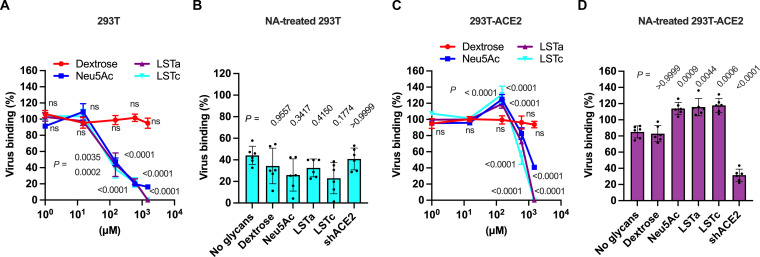

Fig. 2. SA modulates S-mediated attachment of virions to cells.

(A) Quantification of GFP fluorescence resulting from pseudovirion attachment to 293T cells lacking ACE2 expression. Particles were incubated with the indicated glycan concentrations before adsorption on cells. (B) 293T cells treated with NA to remove cell-surface terminal SAs were inoculated with viral particles preincubated with 150 μM of the indicated glycan or 1.4 μM shACE2. (C) Quantification of pseudovirion attachment to 293T-ACE2 cells following incubation with the indicated glycan concentrations. (D) The same data acquired following treatment of 293T-ACE2 cells with NA. Data are expressed as the percentage of virus attachment with respect to the binding observed with mock-treated virus. Individual values, the arithmetic means, and SDs of three independent experiments performed in duplicate are shown. Statistical significance was evaluated through one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. P values are shown, and those <0.05 were considered statistically significant. ns, not significant.

We next sought to determine the role of SA during virus attachment to cells expressing ACE2. Approximately five-times more virus attached to 293T cells stably expressing ACE2 (293T-ACE2) as compared to 293T cells lacking ACE2 (fig. S2, B and G). As before, we preincubated fluorescent pseudovirions with different concentrations of dextrose, Neu5Ac, LSTa, or LSTc before incubation with 293T-ACE2 cells (Fig. 2C). Incubation with dextrose had no effect on pseudovirion binding. Preincubation of pseudovirions with 150 μM Neu5Ac, LSTa, or LSTc, resulted in 25 ± 6%, 19 ± 5%, and 31 ± 10% increase in virus attachment to 293T-ACE2 cells, respectively, while lower concentrations had no effect (Fig. 2C and fig. S2H). Incubation with higher concentrations resulted in reductions of cell binding, with complete abrogation seen at 1.5 mM LSTa or LSTc (Fig. 2C). When cells were pretreated with NA to remove SA from the cell surface, virus attachment to 293T-ACE2 cells decreased by 15 ± 7% (fig. S2I). This result is consistent with the reduction of infectivity in 293T-ACE2.TMPRSS2 cells pretreated with NA (fig. S1E). Other reports using different cell lines have indicated variable impact of NA treatment, ranging from no effect to similar reductions in virus binding and infectivity (47, 54, 55). Preincubation of pseudovirions with Neu5Ac, LSTa, or LSTc restored attachment to levels seen in the absence of NA treatment (Fig. 2D). Incubation of pseudovirions with any glycan tested in addition to shACE2 resulted in an ~60 to 70% decrease in binding to 293T-ACE2, whether or not cells were treated with NA (fig. S2, J and K). These results emphasize that S binding to ACE2 is the primary mediator of virus attachment. These results also show that the presence of SA-containing compounds can enhance attachment to ACE2-expressing cells.

Soluble SA compounds enhance shACE2 binding by SARS-CoV-2 spikes

The results above are consistent with SA and ACE2 promoting attachment of SARS-CoV-2 to the cell surface through distinct mechanisms. Alternatively, interaction of S with SA and ACE2 might work in concert to facilitate efficient attachment. To differentiate between these two possibilities, we next asked whether interaction of S with SA affects subsequent binding of S to ACE2. We used a previously validated fluorescence correlation spectroscopy (FCS) assay to evaluate shACE2 binding to SARS-CoV-2 S ectodomain trimers (SΔTM) in solution (28). FCS provides a means of quantifying molecular interactions by measuring the timescale of diffusion of a fluorescent species before and after interaction with a binding partner. We first incubated SΔTM with varying concentrations of SA-containing glycans or dextrose, followed by introduction of a fixed concentration of shACE2, which had been fluorescently labeled with Cy5 (Fig. 3A). We then quantified the SΔTM-ACE2 interaction using FCS as described in Materials and Methods. Incubation of SΔTM trimers with Neu5Ac, LSTa, or LSTc resulted in increased shACE2 binding (Fig. 3, B to D). The extent of shACE2 binding increased with the concentration of SA-containing glycans and reached an approximately twofold increase at the highest concentration of 300 μM. Treatment of SΔTM spikes with dextrose did not affect shACE2 binding. No significant difference in the extent of enhancement of shACE2 binding was seen across the three SA-containing glycans considered here. These results suggest that interaction of the SARS-CoV-2 S with SA enhances subsequent binding of S to ACE2, with no dependence on the nature of the glycosidic linkage of SA.

Fig. 3. SA enhances shACE2 binding to SARS-CoV-2.

(A) Scheme of the FCS assay used to evaluate Cy5-labeled shACE2 (tan) binding to SΔTM (cyan) (28). (B to E) Cy5-labeled shACE2 was incubated in the absence or presence of SΔTM spikes preincubated with the indicated concentration of dextrose (B), Neu5Ac (C), LSTa (D), or LSTc (E). FCS data were acquired and fit as described in Materials and Methods. Data are expressed as fold change of shACE2 binding to glycan-treated SΔTM with respect to the binding observed with untreated SΔTM. Violin plots show the distribution of individual binding values (blue dots), the median (gray circles), and the mean shACE2 binding (horizontal lines) from at least two independent experiments, each consisting of at least 20 10-s acquisitions. Vertical lines extend to the 25th and 75th quantiles. Statistical significance was evaluated through one-way ANOVA. P values are shown, and those <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

SARS-CoV-2 S binds to SA on the cell surface through the NTD

Evidence from in silico, biochemical, and structural approaches suggests that the NTD domain of SARS-CoV-2 S binds SA-containing compounds like gangliosides (36, 39–41, 43, 44). We therefore investigated whether the NTD could be involved in the attachment of virions to the cell surface. We evaluated the binding to either 293T or 293T-ACE2 cells of GFP-labeled pseudovirions incubated with the neutralizing mAb 4A8, which targets the NTD of S without interfering with its binding to ACE2 (15). Targeting S with 4A8 decreased attachment of pseudovirions to 293T cells by 61 ± 5% (Fig. 4A, orange bars). Incubation of pseudovirions with both 4A8 and shACE2 together resulted in a similar observation, indicating that the RBD does not have a substantial role in binding to 293T cells lacking ACE2 expression (Fig. 4A, cyan bars). In contrast, incubation of pseudovirions with 4A8 had no significant effect on binding to 293T-ACE2 cells (Fig. 4B, green bars), consistent with previous observations (15). As expected, coincubation of pseudovirions with 4A8 and shACE2 decreased attachment to 293T-ACE2 cells by approximately 70% (Fig. 4B, purple bars). These results suggest that S can attach to the surface of cells lacking ACE2 by way of the NTD and that 4A8 blocks the interaction between the NTD and the cell surface. When viewed together with previously published work (36, 39–41, 43, 44), these data support the hypothesis that the NTD facilitates attachment to the cell surface through SA binding.

Fig. 4. SARS-CoV-2 S NTD mediates virus binding to cells.

(A) Quantification of the binding of fluorescent SARS-CoV-2 S pseudovirions preincubated with 625 nM of either 4A8 or an irrelevant (Irr) antibody, 1.4 μM of shACE2, or with the indicated combination, to 293T cells. (B) Quantification of binding of fluorescent pseudovirions pretreated as in (A) to 293T-ACE2 cells. Data are expressed as the percentage of virus bound to cells compared to the binding of untreated virus. Individual values, the arithmetic means, and SDs of three independent experiments performed in duplicate are shown. Statistical significance was evaluated through nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis test, and P values were obtained from comparisons against the mock-incubated virus. P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

To test this hypothesis, we evaluated the role of the S NTD in binding SA using surface plasmon resonance (SPR). We covalently attached the α2,6-linked sialoside glysyl-6′-sialyllactose (GSL) to sensor chips as indicated in Materials and Methods. First, we validated the GSL-sensor chips by evaluating the binding of the lectin Sambucus nigra agglutinin (SNA, fig. S3A), which specifically binds α2,6-linked sialosides (56). The equilibrium dissociation constant (Kd) calculated from binding SNA to our GSL-sensor chip was 544.7 ± 6.79 nM, in agreement with a previously reported value obtained using similar methodology (56). We next determined the binding properties of SΔTM trimers to the GSL-sensor chip. This resulted in calculation of an average Kd of 1.36 ± 0.399 nM (Fig. 5A and fig. S3B). This value is similar to reported Kds for SΔTM trimer binding to heparin sulfate, mAb 2G12, which targets an epitope consisting of glycans in the S2 domain, as well as other lectins binding to SA (29, 31, 33, 56, 57). We then evaluated the impact of mAb 4A8 on SΔTM binding to the GSL-sensor chips (Fig. 5B and fig. S3C). Preincubation of SΔTM with mAb 4A8 resulted in a 68 ± 6% reduction of SΔTM binding to the GSL-sensor chip (Fig. 5C). This result indicates that SARS-CoV-2 S NTD binds sialosides through a mechanism that is inhibited by mAb 4A8.

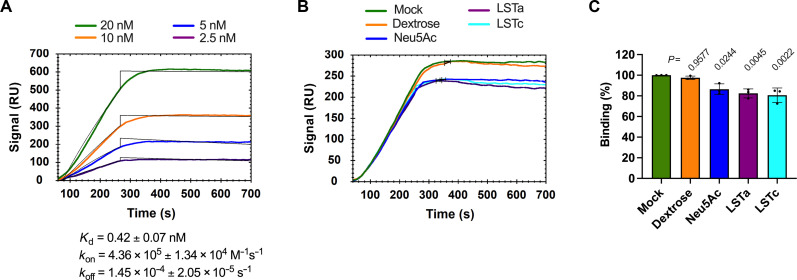

Fig. 5. The NTD-directed mAb 4A8 blocks binding of SΔTM trimers to GSL.

(A) Representative sensorgram indicating binding of SΔTM trimers to the surface of sensor chips coated with the sialoside GSL. The arithmetic mean of the kinetic parameters of the SΔTM binding to GSL-sensor chips was calculated from two independent experiments as described in Materials and Methods. (B) Representative SPR sensorgram showing the binding of SΔTM trimers previously incubated with 600 nM of either mAb 4A8 or an irrelevant (Irr) antibody to the surface of sensor chips coated with GSL. Mock incubation was performed in the absence of mAb. (C) Quantification of the maximum binding of SΔTM to the GSL-sensor chips like those shown in (B). Data are expressed as the percentage of bound SΔTM with respect to the binding observed with mock-incubated SΔTM. Individual values, the arithmetic means, and SDs from four independent experiments are shown. Statistical significance was evaluated through one-way ANOVA test, and P values from comparisons against the binding of mock-treated SΔTM to GSL-sensor chips are shown.

To further confirm this observation, we sought to determine whether SA interaction with the NTD could interfere with 4A8 binding. To this end, we developed an alternative SPR assay in which SΔTM was preincubated with sialoside compounds followed by evaluation of SΔTM binding to 4A8 immobilized on the sensor chip. In the absence of sialoside, SΔTM bound the 4A8-sensor chip with an average Kd = 0.42 ± 0.07 nM (Fig. 6A and fig. S3D), in approximate agreement with the previously reported value (15). Incubation of SΔTM trimers with 300 μM Neu5Ac, LSTa, or LSTc resulted in reduction of 14 ± 5%, 18 ± 4%, and 20 ± 7% in the binding to 4A8, respectively (Fig. 6, B and C, and fig. S3E). These results were consistent with competitive enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) assays, which yielded a comparable Kd in the absence of sialosides (fig. S3F), and similar reductions in 4A8 binding after incubation with the same sialosides (fig. S3G).

Fig. 6. NTD mediates SARS-CoV-2 S binding to host cell SAs.

(A) Representative sensorgram indicating binding of SΔTM trimers to the surface of sensor chips coated with the NTD-directed 4A8 antibody. The arithmetic mean of kinetic parameters of the SΔTM binding to 4A8-sensor chips was calculated from two independent experiments as described in Materials and Methods. (B) Representative SPR sensorgram showing the binding to mAb 4A8–coated sensor chips of SΔTM trimers previously incubated with 300 μM of the indicated glycans. (C) Quantification of the maximum binding of mock- or glycans-treated SΔTM to the surface of 4A8-sensor chips was determined from sensorgrams like that shown in (B), and data from three independent experiments are expressed as the percentage of bound SΔTM with respect to the binding observed with mock-incubated SΔTM. Statistical significance was evaluated through parametric one-way ANOVA test, and P values from comparisons against the binding of mock-treated SΔTM to 4A8-sensor chips are shown.

These data provide additional support for the proposed SA-binding role of NTD. To further test this hypothesis, we took a mutagenesis approach. Structural data have shown that the sialoside-binding site in the NTD comprises the amino acids H69, Y145, W152, Q183, and S247. Y145 notably engages the C7-C9 glycerol side chain of sialosides, while S247 engages the NHAc-5 (43). We therefore sought to eliminate these stabilizing NTD-SA interactions through expression of SΔTM bearing the amino acid changes Y145F and S247A in the NTD (NTDmut). We first validated the antigenicity of NTDmut through ELISA assays using mAb 4A8 (15) and the RBD-directed mAbs Mab362IgA1, REGN10933, and REGN10987 (58, 59). We detected no loss of antibody binding to NTDmut compared to wild-type SΔTM, except for REGN10987, which showed a slight, but statistically significant increase in binding to NTDmut (fig. S4A). We then evaluated the shACE2-binding properties of the NTDmut trimer through both an ELISA assay (fig. S4A), and the FCS approach described above (fig. S4B). The NTDmut trimer showed decreased shACE2 binding by ~40% compared to wild-type SΔTM in both approaches (fig. S4, A and B). Together, these findings indicate that NTDmut trimers maintain near-native antigenic properties but also allosterically reduced shACE2 binding. We then evaluated the binding of NTDmut to GSL-prepared sensor chips through SPR in the same way as described above for wild-type SΔTM (fig. S4C). The binding of the NTDmut trimer to GSL-sensor chips was reduced by 43 ± 6% compared to the binding observed for wild-type SΔTM (fig. S4D). These data support the existence of an SA-binding site in the NTD, which involves residues Y145 and S247.

SA allosterically modulates the RBD conformation

Our observations indicate that SARS-CoV-2 S NTD binds SA, which promotes attachment of virions to the cell surface and enhancement of ACE2 binding. We therefore investigated the mechanism governing this phenotype. We used a well-characterized smFRET imaging assay (28, 60) to probe the conformational dynamics of the RBD of SΔTM in the presence of SA-containing compounds (Fig. 7A). Application of this assay required site-specific attachment of fluorophores at positions 161 and 345 in the NTD and RBD domains, respectively. As previously described, the application of hidden Markov modeling (HMM) for analysis of the smFRET trajectories enabled identification of two FRET states (Fig. 7B). The low-FRET state is associated with RBD in an open conformation (RBD-up), which can bind ACE2. The high-FRET state is associated with RBD in a closed conformation (RBD-down) (28, 60). As expected, unbound SΔTM displayed 38 ± 2% occupancy in the RBD-up conformation. Incubation with 0.6 μM shACE2 increased the RBD-up conformation occupancy to 69 ± 2% (Fig. 7C, fig. S5, and Table 1). Incubation of spikes with 300 μM Neu5Ac, LSTa, or LSTc, resulted in significant increases in the RBD-up conformation to 56 ± 2%, 54 ± 2%, and 65 ± 1%, respectively (Fig. 7C, fig. S5, and Table 1). Incubation with dextrose had no effect. These results suggest that SA compounds stabilize the RBD-up conformation.

Fig. 7. smFRET imaging reveals that SA compounds modulate SARS-CoV-2 S RBD conformation.

(A) smFRET imaging assay used to monitor RBD conformational changes (28, 60). SΔTM trimers containing a single fluorescently labeled protomer were immobilized on a streptavidin-coated quartz microscope slide by way of a C-terminal polyhistidine tag and biotin–Ni-NTA. Individual SΔTM spikes were visualized with prism-based total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy. The two known RBD conformations, RBD-down (left) and RBD-up (right), as well as covalently attached LD550 and LD650 fluorophores, are indicated. (B) Example fluorescence (top; LD550, green; LD650, red) and FRET (bottom, blue) traces acquired from an individual SΔTM trimer. Idealization (red) that results from HMM analysis is overlaid. FRET states reflective of the RBD-down and RBD-up conformations are indicated. (C) Violin plots showing the distribution of the occupancy in the RBD-up (low FRET) conformation seen in the presence of the indicated ligands. The median occupancies are indicated by the gray circle with vertical lines extending to the 25th and 75th quantiles. The mean occupancies are indicated by the horizontal lines. P values were determined by comparison of ligand-bound and unbound SΔTM through one-way ANOVA. (D) Violin plots indicating the RBD-up occupancies following incubation with NTD-directed mAb 4A8, an irrelevant antibody (Irr mAb), or through the sequential incubation with the indicated mAb and LSTc, displayed as in (C). P values were derived as in (C) from comparisons between the 4A8-incubated SΔTM and the other conditions. P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. (E) RBD-up occupancies from NTDmut trimers in the presence or absence of the indicated ligands, shown as in (C) and (D). P values were derived as in (C) from comparisons unbound NTDmut and those incubated with the indicated ligands. The corresponding histograms of FRET values are shown in fig. S5, and the numeric data are reported in Table 1.

Table 1. FRET-state occupancies and rate constants for SARS-CoV-2 SΔTM.

| SARS-CoV-2 S | Number of traces | FRET-state occupancies (%) | Rate constants (s−1) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low-FRET (0.35) RBD-up | High-FRET (0.65) RBD-down | k1 (RBD-down toRBD-up) | k−1 (RBD-uptoRBD-down) | ||

| wt unbound | 184 | 38 ± 2 | 63 ± 2 | 2.2 ± 0.1 | 3.6 ± 0.3 |

| wt + shACE2 | 116 | 69 ± 2 | 31 ± 2 | 2.5 ± 0.2 | 1.12 ± 0.08 |

| wt + Dextrose | 134 | 42 ± 2 | 58 ± 2 | 2.4 ± 0.1 | 3.5 ± 0.2 |

| wt + Neu5Ac | 137 | 56 ± 2 | 44 ± 2 | 2.3 ± 0.2 | 2.0 ± 0.2 |

| wt + LSTa | 115 | 54 ± 2 | 46 ± 2 | 2.9 ± 0.3 | 2.5 ± 0.2 |

| wt + LSTc | 316 | 65 ± 1 | 35 ± 1 | 2.8 ± 0.2 | 1.52 ± 0.09 |

| wt + 4A8 | 191 | 42 ± 2 | 58 ± 2 | 2.2 ± 0.1 | 3.0 ± 0.2 |

| wt + 4A8 + LSTc | 144 | 44 ± 2 | 56 ± 2 | 2.3 ± 0.2 | 3.3 ± 0.2 |

| wt + Irr mAb | 157 | 40 ± 2 | 60 ± 2 | 2.3 ± 0.2 | 3.5 ± 0.2 |

| wt + Irr mAb + LSTc | 174 | 64 ± 2 | 36 ± 2 | 3.0 ± 0.3 | 1.5 ± 0.1 |

| NTDmut unbound | 124 | 41 ± 1 | 59 ± 1 | 3.4 ± 0.3 | 5.0 ± 0.4 |

| NTDmut + shACE2 | 143 | 60 ± 2 | 40 ± 2 | 3.9 ± 0.3 | 2.8 ± 0.2 |

| NTDmut + LSTc | 213 | 41 ± 2 | 59 ± 2 | 1.9 ± 0.1 | 2.7 ± 0.2 |

Further insights came from analysis of the kinetics of SΔTM conformational transitions. Consistent with our previous report (28), the predominant effect of shACE2 binding was to decrease the rate of transition from the RBD-up conformation to the RBD-down conformation (k−1; Table 1), suggesting that shACE2 captures the RBD-up conformation after it is spontaneously achieved. Similarly, the SA-containing compounds had only a minor effect on the rate of transition from RBD-down to RBD-up (k1). The more notable impact was on k−1, which decreased from 3.6 ± 0.3 s−1 in the absence of glycan, to 2.0 ± 0.2 s−1 in the presence of Neu5Ac (Table 1). LSTc had the most dramatic effect on k−1, reducing it to 1.52 ± 0.09 s−1, whereas LSTa reduced k−1 to 2.5 ± 0.2 s−1. This kinetic analysis specifies that SA compounds primarily stabilize the RBD-up conformation and reduce transitions to the RBD-down conformation, thereby increasing exposure of the ACE2-binding site.

As previously reported, incubation of SΔTM with 4A8 modestly increased the RBD-up conformation to 42 ± 2% (28), whereas an irrelevant antibody had no effect (Fig. 7D, fig. S5, and Table 1). Subsequent incubation with LSTc failed to increase the RBD-up occupancy to the extent seen in the absence of 4A8. Therefore, consistent with our SPR data indicating that 4A8 prevents NTD binding to SA, 4A8 inhibits SA-induced conformational changes in SΔTM.

mAb 4A8 inhibits SA-mediated RBD activation

Having observed that 4A8 inhibited LSTc-induced RBD activation (Fig. 7D), we next asked whether this has a functional impact in ACE2 binding. Whereas we observed a twofold increase in shACE2 binding to SΔTM bound to LSTc as compared to unbound SΔTM, preincubation of SΔTM with 4A8 before introduction of LSTc failed to increase shACE2 binding. Instead, we observed a decrease in shACE2 binding of 46 ± 1% compared to untreated SΔTM (fig. S4E). Preincubation with the RBD-directed antibody REGN10987, used as a control for blocking shACE2 binding, resulted in a decrease shACE2 binding by 65 ± 1%, as expected. Preincubation of the NTDmut trimer with LSTc or REGN10987 resulted in slight decreases in shACE2 binding of 17 ± 2% or 46 ± 2%, respectively, as compared to untreated NTDmut trimers (fig. S4F). Together, these data demonstrate that interruption of the SA-NTD interaction, either through treatment with 4A8 or mutagenesis, decreases SΔTM binding to ACE2. This observation suggests that SA may interact with SΔTM through mechanisms not involving the NTD, which inhibit ACE2 binding.

In agreement with these findings, conformational analysis of NTDmut performed through smFRET imaging showed that shACE2 binding activated the RBD-up conformation on the NTDmut trimer and that LSTc failed to trigger RBD conformational changes (Fig. 7E, figs. S4G and S5, and Table 1). Together, these data indicate the relevance of NTD in allosterically activating the RBD-up conformation through interaction with SA, which facilitates engagement with ACE2 during SARS-CoV-2 entry.

DISCUSSION

Several virus families including Coronaviridae exploit host glycans present on cellular membranes during early events of viral infection (61, 62). Virus attachment to glycans on the cell surface may enable the virus to “surf” to membrane microdomains enriched in their cognate receptors (63). In the case of SARS-CoV-2, host glycans on the plasma membrane are a determinant of virion attachment to the cell surface (35). Here, we investigated the relationship between sialoside glycans and ACE2 binding to SARS-CoV-2 S during virion attachment to the cell surface. Overall, our findings demonstrate that S binding to SA can mediate attachment to the cell surface in the absence of ACE2. In the presence of ACE2, interaction of S with cell-surface SA moieties resulted in biphasic binding of pseudovirions to cells with peak binding occurring at 150 μM SA (Fig. 2C). The increase in ACE2 binding results from sialoside glycans binding to the NTD and allosterically stabilizing the S conformation in which the RBD is up and the ACE2-binding site is exposed. Similar biphasic binding of influenza A virions to the GD1a ganglioside in the presence of orthogonal SA compounds has also been reported (64).

A previous report indicated that interaction of SARS-CoV-2 S RBD with the proteoglycan heparin, which has subunits of glycosaminoglycans formed by d-glucuronic acid β1–4 linked to N-acetyl-d-glucosamine (65), increased ACE2 binding (31). Structural analysis suggested that heparin directly promotes the open conformation of RBD, thus facilitating the binding to ACE2 (31). The present results elucidate an additional complementary role for host glycans in promoting virus attachment to the cell surface—here through an allosteric mechanism—and increasing subsequent binding to ACE2. Notably, a recent structural study of the HKU1 coronavirus spike demonstrated that binding of a sialoglycan to the S1A domain, homologous to NTD, promoted a conformation in which the S1B domain, homologous to the RBD, had transitioned to an up conformation (66). This study reported the observation of an RBD-up conformation in the HKU1 spike and suggests a similar allosteric mechanism to that supported by our data for the SARS-CoV-2 spike. Further studies are needed to elucidate the generality of this mechanism in other coronaviruses. Allosteric activation of influenza virus hemagglutinin (HA) by SA has also been reported. Treatment of HA with liposomes containing the GD1a ganglioside or soluble LSTa induced conformational changes in the fusion peptide, which resides more than 100 Å from the SA-binding site (67). These observations indicated that SA binding to HA allosterically stimulates conformational changes that promote membrane fusion and virus entry. Whether SA binding to S promotes analogous conformational changes in the S2 domain will require future investigations. While the present observations only report on RBD motions that result from NTD-SA interaction, the subsequent enhancement of ACE2 binding to the RBD may in turn increase exposure of the TMPRSS2 cleavage site (68, 69). In this way, SA binding to the NTD may indirectly contribute to the activation of the fusogenic activity of S (19). These studies collectively support a model in which viral envelope glycoproteins sense cues at the cell surface that promote downstream events in virus entry.

The neutralizing mAb 4A8, which targets the NTD, allosterically modulates S1/S2 cleavage and blocks S-mediated membrane fusion (19). Similarly, the NTD-directed mAb 7G7 inhibited access of furin-like proteases to the S1/S2 cleavage site, preventing cleavage and reducing infectivity (20). Our data suggest that this class of antibodies also prevents NTD-SA interactions. Analysis of S structures in complex with 4A8 or SA indicate that the 4A8- and SA-binding sites do not overlap (Fig. 8). Instead, binding of 4A8 to the NTD leads to localized conformational changes that reorient NTD residues Y145, Q183, and S247. In the SA-bound structure, these residues form stabilizing electrostatic interactions with SA. Blocking NTD-SA interactions then has the combined effect of inhibiting SA-mediated virus attachment to the cell surface, as well as reducing SA-promoted exposure of the ACE2-binding site. In this way, the data presented here contribute understanding to the mechanism of neutralization by NTD-targeting mAbs (15, 70, 71).

Fig. 8. Binding of 4A8 mAb to SARS-CoV-2 S NTD indirectly prevents SA binding.

(A) Aligned structures of the trimeric S ectodomain determined in complex with the antigen-binding fragment of 4A8 [cyan cartoon rendering; PDB 7C2L (15)] or sialyllactose (only the SA moiety is shown in yellow) [gray, PDB 7QUR (43)]. Two protomers in the trimer are displayed in gray surface rendering. RBD and NTD domains are indicated, with the NTD highlighted in a box. (B) Expanded view of the NTD bound to 4A8 (cyan) or SA (gray, with SA in yellow). (C) Further expanded view of the 4A8 and SA binding interfaces, which do not overlap. NTD residues Y145, Q183, and S247, which form the SA-binding site are indicated. These residues are rearranged in the presence of 4A8, leading to loss of the SA-binding site.

The relationship between S sequence variation and glycan binding requires further investigation. Structural analysis of the NTD suggested four sugar-binding sites (72), including the sialoside-binding pocket previously proposed (39). Mutations in the NTD of the Omicron variant increased the predicted SA-binding energy compared to the original Wuhan-1 strain, which may contribute to the increased transmission of the Omicron lineage (72). However, nuclear magnetic resonance experiments demonstrated that spikes from the Alpha (B.1.1.7), Beta (B.1.351), Delta (B.1.617.2), and Omicron (B.1.1.529) strains have depleted binding to α2,3-linked sialosides as compared to that observed for the Wuhan-1 strain (43). It remains to be explored whether the putative glycan-binding pockets in the NTD from SARS-CoV-2 variants can bind other glycans and whether they modulate conformational changes in S. Nevertheless, it is interesting that variant spikes have both deletions and multiple point mutations in the NTD, which may affect glycan binding (73, 74). In the present study, S containing mutations Y145F and S247A in the NTD had decreased occupancy in the RBD-up conformation (figs. S4F and S5 and Table 1) and reduced shACE2 binding (fig. S4, A and B) compared to wild type. This observation suggests a relevant and functional role for the NTD in regulating the binding to ACE2. In addition, the RBD equilibrium evolved to predominantly adopt the up conformation (21–25, 75). This may be evidence that the variant spikes rely less on activation of the RBD by the NTD binding to SA. Consequently, this could provide the variants with the ability to directly bind ACE2 while at the same time evading neutralizing antibodies targeting the NTD (16, 76–82). Similarly, the evolution of additional positive charge in the RBD may increase binding to cell-surface heparan-sulfate proteoglycans, further reducing the dependence on NTD-SA interactions (83).

Overall, the results presented here, together with previous observations of other viral fusion proteins (31, 66, 67), support a model for early interactions between virions and cells where host glycans play a fundamental role in the allosteric activation of viral spike proteins. This allosteric control results in conformational changes that promote receptor binding and membrane fusion. Future studies will explore the generality of this concept in other virus families.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture

ExpiCHO-S cells (Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) were cultured in ExpiCHO expression media (Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) at 37°C, 8% CO2 with orbital shaking according to the manufacturer instructions. HEK-293T cells were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA). HEK-293T cells expressing human ACE2 [293T-ACE2, BEI Resources, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), National Institutes of Health (NIH), catalog no. NR-52511] (84) were provided by T. Morrison (UMass Chan Medical School). HEK-293T cells expressing both ACE2 and TMPRSS2 [293T-ACE2.TMPRSS2 (mCherry), catalog no. NR-55293] (48), were obtained from BEI Resources (NIAID, NIH). All the HEK-293T cell lines used were cultured at 37°C and 5% CO2 in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM, Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Whaltham, MA, USA), supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (BenchMark, GeminiBio, Sacramento, CA, USA), penicillin (100 U/ml), streptomycin (100 μg/ml), and 1 mM glutamine (Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

Plasmids and site-directed mutagenesis

Molecular clones of the heavy and light chains of the anti–HIV-1 Env mAb 17b (85), used in this study as an irrelevant antibody, were provided by P. Kwong (NIAID, NIH). The pNL4-3.Luc.R-E- plasmid was obtained from the NIH AIDS reagent program (catalog ARP-3418) (86). An ochre stop codon was introduced into the tat gene as described (87). The plasmid encoding the HIV-1 GagPol under the control of the cytomegalovirus promotor has been described previously (88), while the replication-deficient molecular clone HIV-1 NL4-3 Gag-iGFP ΔEnv (89) was provided by B. K. Chen (Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, NY). The plasmid pMM310-Myc (catalog no. 80053) encoding a Myc-tagged version of the BlaM-HIV-1 Vpr fusion protein (Myc-BlaM-Vpr) (90) was obtained from Addgene (Watertown, MA, USA). The full-length SARS-CoV-2 S expression plasmid used to produce S-pseudotyped viruses has been previously described (21). Both expression vectors bearing human immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1) heavy-chain (hIgG1) and kappa light-chain Fc fragments (hIgKappa) (91) for cloning of recombinant antibodies were provided by M. C. Nussenzweig (The Rockefeller University, New York, NY, USA). To generate a molecular clone of mAb 4A8, heavy and light variable (VL) region sequences (15) were synthesized (GeneScript USA Inc., Piscataway, NJ, USA) and cloned in-frame with hIgG1 heavy or hIgKappa light chain in the above expression vectors (91) through AgeI/SalI or AgeI/BsiWI restriction sites, respectively. The synonymous nucleotide change C174T was included in the synthetic VL sequence to remove an AgeI restriction site and to facilitate its subcloning into the hIgKappa vector. SARS-CoV-2 S and SΔTM expressors have been described before (21, 28). Mutations Y145F and S247A were introduced into SΔTM expressors (28) using the primers Y145F-R (aggaaggggtcattgcaaaattggaattc), Y145F-F (gggcgtgtacttccataagaacaacaagtcttgg), S247A-R (ccagcagggtctggaaccgg), and S247A-F (ccctgcacagagcctatctgacccccggcgattc) in mutagenic polymerase chain reactions using the Q5 Site-Directed Mutagensis Kit (NEB, Ipswich, MA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Site-directed mutagenesis was confirmed through Sanger sequencing (GENEWIZ, Walthman, MA, USA).

Antibodies, recombinant proteins, and soluble glycans

mAbs 4A8 and 17b were expressed in ExpiCHO-S cells by cotransfection of recombinant constructs bearing their respective heavy and light chains at 1:2 ratio using the ExpiFectamine CHO transfection kit (Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Both antibodies were purified from the cell culture supernatant 12 days after transfection through protein G affinity resin (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and prepared as previously described (28). Human mAbs Mab362IgA1, REGN10933, and REGN10987 were previously prepared (28). Mouse mAbs anti–HIV-1-p24 (anti-p24, catalog no. GTX41618) and 1A9 anti–SARS-CoV-2 S2 (catalog no. GTX632604) were purchased from Genetex (Irvine, CA, USA). Anti–Myc-tag mouse mAb (catalog no. A00704-100) was purchased from GenScript (Piscataway, NJ, USA). Both horseradish peroxidase (HRP)–conjugated anti-human IgG Fc and anti-mouse IgG Fc were purchased from Invitrogen (Waltham, MA, USA). HRP-conjugated anti-human kappa antibody (catalog no. 2060-05) was purchased from SouthernBiotech (Birmingham, AL, USA), while both rabbit anti-ACE2 antibody (catalog no. ab108252) and goat anti-rabbit IgG antibody conjugated to HRP (catalog no. ab205718) were gotten from Abcam (Cambridge, UK). Expression, purification, and preparation of SARS-CoV-2 S ectodomain SΔTM trimers, shACE2, and their fluorescent versions for biochemical, FCS, and smFRET assays have been previously described (28). The lectin SNA and the recombinant nonglycosylated HIV-1 gp120 polypeptide chain were purchased from Vector Laboratories (Newark, CA, USA) and Abcam (Cambridge, UK), respectively. N-acetylneuraminic acid (Neu5Ac) and dextrose (d-glucose) were purchased from MP Biomedicals LLC (Irvine, CA, USA) and J. T. Baker Avantor (Radnor, PA, USA) respectively. GSL, the LSTa, and LSTc were purchased from Dextra Laboratories (Reading, UK).

Virus production

HIV-1–pseudotyped viruses based on three different nonreplicative NL4-3 provirus molecular clones were produced as follows. SARS-CoV-2 S pseudoviruses for infectivity assays based on the luciferase activity reporter were produced by cotransfecting HEK-293T cells with a 3:1 mass ratio of plasmid pNL4-3.Luc.R-E- tat_ochre to Wuhan-Hu-1 SARS-CoV-2 S expressor plasmid (21) using polyethylenimine (PEI “MAX,” Polysciences, Warrington, PA) at a PEI:DNA mass ratio of 5:1. Fluorescent and nonreplicative S pseudoviruses for cell-binding assays were produced by cotransfecting cells with the plasmid pNL4-3 Gag-iGFP ΔEnv (89) and the above SARS-CoV-2 S expressor using the above-described PEI:DNA ratio. Nonreplicative SARS-CoV-2 S pseudoviruses used to evaluate viral fusion and cell entry assays were produced by cotransfection of the above SARS-CoV-2 S expressor together with plasmids encoding the HIV-1 GagPol (88) and Myc-BlaM-Vpr (90) in a ratio of 1:1:1. For all three varieties of pseudovirions, bald particles lacking SARS-CoV-2 S were produced and used as negative controls in their respective approaches. In all cases, cells were washed 6 hours after transfection and incubated with fresh complete DMEM for an additional 64 hours. Viral supernatants were harvested and centrifuged at 4000g at room temperature, followed by passage through a 0.45-μm low protein–binding filter. Viruses for infectivity assays (luciferase activity reporter) were concentrated by ultracentrifugation at the maximum g-force of 107,100g for 2 hours at 4°C, while virus preparations for cell binding and cell entry (BlaM-based) assays were similarly utracentrifuged through a 10% sucrose cushion. Viral pellets for infectivity and for cell entry assays were resuspended in regular or phenol red-free DMEM (Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) respectively, while those for cell-binding assays were resuspended in Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS; Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The HIV-1 p24 protein content of all the virus preparations was determined by using the Lenti-X p24 Rapid Titer Kit (Takara Bio USA Inc., San Jose, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s indications. Virus preparations were aliquoted and stored at −80°C until use.

Immunoblots

Proteins of interest were detected in the indicated virus preparations through immunoblot assays as follows. Viral samples were mixed with 4× Laemmli sample buffer (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) supplemented with 2-mercaptoethanol (Fisher Chemical, Hampton, NH, USA), heated for 5 min at 98°C, and proteins were resolved by denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis using 4 to 20% acrylamide gels (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Protein gels were then transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After blocking for 1 hour at room temperature with 5% (w/v) skim milk in PBS-T buffer [PBS and 0.1% (v/v) Tween-20, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Hampton, NH, USA], membranes were incubated by shaking overnight at 4°C with the indicated primary antibodies diluted in blocking buffer. Specific detection of SARS-CoV-2 S, its S2 subunit, and HIV-1 p24 protein was achieved by using dilutions of 1/2000 of murine mAbs (GeneTex, Irvine, CA, USA) 1A9 (28) and anti-p24, respectively, while a mouse monoclonal anti-Myc tag antibody (GenScript, Piscataway, NJ, USA) diluted 1/5000 was used to detect the Myc-tagged BlaM-HIV-1 Vpr fusion protein. After incubation with primary antibodies, membranes were washed three times with PBS-T and then incubated with HRP-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA) diluted in 0.5% (w/v) skim milk/PBS-T for 1 hour at room temperature. After three washes with PBS-T, membranes were developed using SuperSignal West Pico PLUS Chemiluminescent Substrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Virus cell entry and infectivity assays

The effect of SA treatment on viral cell entry and infectivity was evaluated through two different approaches. First, infectivity assays were performed using 293T-ACE2.TMPRSS2 cells because cell expression of TMPRSS2 makes more efficient virus cell entry (48, 92, 93) and pseudovirions bearing a luciferase gene reporter based on a described method (84) with minor modifications. In brief, 2.0 × 105 293T-ACE2.TMPRSS2 cells per well were seeded 16 hours before the assay in 24-well plates previously treated with poly-l-lysine solution (0.1 mg/ml; MilliporeSigma, Burlington, MA, USA) to improve cell adherence and prevent cell disruption (84). Before infectivity assays, cells were washed twice with MEM, and treated or not with Arthrobacter ureafaciens NA (40 mU/ml; MilliporeSigma, Burlington, MA, USA) for 2 hours at 37°C to remove terminal SAs from the cell surface (35, 47, 54, 94, 95). Cells were then washed twice before 50 ng p24 per well of S pseudoviruses or bald particles (negative control) were diluted in the MEM and were adsorbed on cells for 3 hours at 37°C. When indicated, viruses were incubated with different concentrations of shACE (0 to 1.4 μM) or with 0 to 1.5 mM of dextrose, Neu5Ac, LSTa, LSTc, or the indicated combinations, for 1 hour at 37°C before viral adsorption. Viral inoculums were then removed, cells were washed twice, and fresh complete DMEM was added. Infected cells were washed with DPBS 72 hours after infection and lysed with Glo lysis buffer (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Luciferase activity in cell lysates was detected by mixing equal volumes of lysate and Steady-Glo luciferase assay system reagent (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) and measuring luminescence on a Synergy H1 microplate reader (Biotek, Winooski, VT). Luminescence signal from mock-infected cells lysates was subtracted from the signal obtained from infected cells. Infectivity was expressed as the percentage of that seen in cells inoculated with untreated virus.

In the second approach, the viral membrane fusion and cell entry of pseudovirions was assayed using a BlaM-based enzymatic assay (52) with minor modifications. Briefly, 2.5 × 105 293T-ACE2.TMPRSS2 cells per well were grown in 96-well plates with phenol red–free DMEM for 24 hours. Before virus inoculation, cells were treated or not with NA as indicated above. Viruses were treated with the indicated glycans as described above or with 125 nM of either the mAb 1A9 or 17b [used as irrelevant (Irr) antibody]. Cells treated with NA were put on ice for 3 min. Medium was removed, and pseudovirus equivalent to 75 ng p24 was adsorbed on cells by spinoculation at 2095g, 4°C, for 30 min (52). Cells were washed with cold DMEM to remove unbound virus. Fusion and viral entry were allowed to proceed by shifting the cells to 37°C. After 90 min, cells were chilled briefly by placing 96-w plates on ice, loaded with CCF4-AM fluorophore (LiveBLAzer FRET—B/G Loading Kit, Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA) in the presence of 2.5 mM probenecid (Alfa Aesar, Haverhill, MA, USA), and incubated for 16 hours at 12°C. Detection of the CCF4-AM cleavage by Myc-BlaM-Vpr, as a result of cell entry (52), was determined using a Synergy H1 microplate reader (Biotek, Winooski, VT, USA) according to the manufacturer of the LiveBLAzer FRET—B/G Loading kit (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA). Virus entry was expressed as the percentage of that seen for untreated pseudovirus in mock NA–treated cells.

Virus cell–binding assays

The binding of fluorescent SARS-CoV-2 S–pseudoviruses was evaluated in HEK293T (293T) cells lacking ACE2 expression, or to the HEK-293T-hACE2 cell line that stably expresses human ACE2 but not TMPRSS2, to discard any potential implications of this protease in virus binding (96). For this, 2.5 × 105 cells per well were seeded 24 hours before the assay in flat bottom clear, white polystyrene 96-well plates (Corning, Kennebunk, ME, USA) previously treated with poly-l-lysine solution (MilliporeSigma, Burlington, MA, USA) as above indicated. When indicated, fluorescent S pseudoviruses were incubated or not with the above-indicated concentrations of shACE, the indicated glycans (dextrose, Neu5Ac, LSTa, or LSTc), 625 nM of either the NTD-directed mAb 4A8 or the 17b (Irr) mAb, or the indicated combination of them, for 1 hour at 37°C before viral adsorption. Both fluorescent S pseudoviruses (50 ng p24 per well) or bald viral particles used as negative control, were absorbed for 3 hours on cells previously treated or not with NA as above indicated and set on an ice bath to prevent virus-cell internalization. Viral mixes were then removed, and cells were quickly washed twice with cold DPBS and fixed with cold 2% (v/v) formaldehyde (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) in DPBS for 20 min while kept on the ice bath. Fixed cell monolayers were then washed twice with cold DPBS, and their fluorescence (emission at 530 nm) was determined using a Synergy H1 microplate reader (Biotek, Winooski, VT) through excitation at 485 nm. Fluorescence signal from bald virus absorbed on cells was subtracted from those gotten with S pseudovirus, and the virus binding was expressed as the percent of virus-cell binding gotten with untreated S pseudovirus, which represents 100% of binding in the indicated cell lines.

FCS-based ACE2-binding assay

ACE2 binding to untagged SΔTM spikes was evaluated by FCS as described (28) with minor modifications. Briefly, 50 nM SΔTM was preincubated or not with 150 nM of the indicated antibody for 1 hour before being incubated with the indicated glycan concentration in PBS (pH 7.5) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) for 30 min, followed by additional incubation with 100 nM Cy5-labeled shACE2 for 1 hour at room temperature. Samples were then placed on no. 1.5 coverslips (ThorLabs, Newton, NJ, USA) and mounted on a CorTector SX100 (LightEdge Technologies, Beijing, China) equipped with a 638-nm laser. Twenty to twenty-five autocorrelation measurements per independent experiment were made for 10 s each at room temperature. Fractions of unbound and bound (f) shACE2 after incubation with SΔTM were obtained from normalized autocorrelation curves fitted to a model of the diffusion of two species in a three-dimensional Gaussian confocal volume (97, 98)

where

and τi is the diffusion time for bound or unbound shACE2 and s is the structure factor that parameterizes the dimensions of the confocal volume. shACE2 binding was expressed as the average fraction (f) bound to SΔTM in the presence of the indicated concentrations of glycans with respect to the fraction bound in the absence of glycans (Fig. 3). All fitting was performed with a nonlinear least-squares algorithm (28) in MATLAB (The MathWorks, Waltham, MA, USA) (28).

ELISA assays

Competitive binding to the NTD of SARS-CoV-2 S of mAb 4A8 and the indicated glycans was evaluated with ELISA assays as previously described (28). Briefly, 96-well polystyrene plates (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) were coated either with 200 ng of SARS-CoV-2 SΔTM protein or bovine serum albumin (BSA, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) overnight at 4°C. Plates were washed three times with PBS and blocked for 1 hour at room temperature with 5% (w/v) skim milk in PBS-T. After three washes with PBS, plates were incubated for 2 hours at room temperature with 625 nM of 4A8 mAb together with the indicated concentrations of dextrose, Neu5Ac, LSTa, or LSTc (fig. S3). Incubation with 10 nM of shACE2, or antibodies 4A8, MAb362IgA1, REGN10933, and REGN10987, were used to evaluate binding of NTDmut spike to the soluble monomeric receptor through a sandwich ELISA assay, or its antigenicity through direct ELISA assays, respectively. Rabbit-monoclonal anti-ACE2 antibody (ab108252, abcam, Cambridge, UK) diluted 1:1000 in PBS was used to detect shACE2 bound to spikes. After three washes, the secondary antibody HRP-conjugated anti-human IgG Fc (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA) diluted 1:10,000 in PBS was used in wells treated with 4A8, REG10933, and REG10987 antibodies for 1 hour at 37°C, while HRP-conjugated anti-human kappa antibody (SouthernBiotech, Birmingham, AL, USA) diluted 1:4000 or HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (Abcam, Cambridge, UK) diluted 1:50,000 in PBS were used to detect Mab362IgA1 or anti-ACE2 antibodies, respectively, and developed with 1-Step Ultra TBM-ELISA (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) reagent according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The absorbances at 450 nm were measured using a Synergy H1 microplate reader (BioTek, Winooski, VT). Absorbance values from nonspecific binding to BSA-coated wells were subtracted from the values obtained for SΔTM-coated wells, and results were expressed as the percent of 4A8 bound to SΔTM seen without glycan coincubation.

SPR assays

Binding kinetics and affinities of the lectin SNA for GSL and of SΔTM for GSL and mAb 4A8 (fig. S3) were assessed through SPR using a Nicoya OpenSPR-XT instrument (Nicoya, Kitchener, ON, Canada). Capture surfaces were prepared by covalent immobilization of GSL or mAb 4A8 on carboxyl sensor chips (Nicoya, Kitchener, ON, Canada) using an Amine Coupling Kit (Nicoya, Kitchener, ON, Canada) according to the instructions of the manufacturer. After the mAb 4A8 or GSL immobilization procedure, the average resonance unit (RU) signals of 1.5 ± 0.2 × 103 and 3.6 ± 0.5 × 101 RU were achieved respectively. The indicated dilutions of SNA or SΔTM (fig. S3) were prepared in PBS-T and injected for 5 min at a flow rate of 20 to 50 μl/min with a dissociation phase of 4.5 to 10 min in PBS-T at 20°C. Injections of 10 mM glycine (pH 2.5) at a flow rate of 150 μl/min, resulting in 40 s of contact time, were used to regenerate 4A8-coated surfaces between the injections of analyte. Injections of 100 mM glycine (pH 1.7) were similarly used to regenerate respectively GSL-coated sensor surfaces (56). In both cases, 4.5 min of flow at 150 μl/min of PBS-T was used to reequilibrate sensor surfaces. We assessed the nonspecific binding of SΔTM and SNA to the GSL-coated sensor surfaces by comparison to an irrelevant recombinant nonglycosylated protein covalently immobilized on carboxyl sensors using the same SPR running parameters. When indicated, 10 nM SΔTM was incubated with 600 nM of mAb 4A8 or the irrelevant mAb 17b for 1 hour at room temperature before injection into the SPR instrument to evaluate the maximum SΔTM binding to GSL-coated sensor surfaces (Fig. 5A). Similarly, to evaluate the maximum binding to 4A8-prepared sensor chips, 5 nM SΔTM was incubated with 300 μM (Fig. 5C) dextrose, Neu5Ac, LSTa, or LSTc before injection into the SPR instrument. Two independent experiments were performed with SNA and SΔTM under each indicated condition. Kinetic parameters were obtained by fitting the corrected data to a 1:1 binding model using TraceDrawer software v1.9.1 (Ridgeview Instruments AB, Uppsala, Sweden). The association rate constant (kon) was determined by fitting the binding of the analyte (SNA or SΔTM) at each concentration. The dissociation rate constant (koff) was determined by fitting the change in the binding response during both the association and the dissociation phases. The equilibrium Kd was calculated from the ratio of kon to koff. When indicated, maximum SΔTM binding values were obtained using the above software and the corresponding data (Figs. 5B and 6B and figs. S3, C and E, and S4C). Results were plotted (Figs. 5C and 6C and fig. S4D) using GraphPad Prism version 9.2.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Data are expressed as the percent of SΔTM bound to the indicated sensor compared to the level of binding observed in the control condition.

smFRET imaging and data analysis

Labeled SΔTM spikes were immobilized on streptavidin-coated quartz microscope slides by way of Ni-NTA–biotin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and imaged using wide-field prism-based total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy as described (28, 60, 99, 100). Imaging was performed in PBS containing 1 mM trolox (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), 1 mM cyclooctatetraene (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), 1 mM 4-nitrobenzyl alcohol (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), 2 mM protocatechuic acid (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), and 8 nM protocatechuate 3,4-deoxygenase (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) to stabilize fluorescence and remove molecular oxygen. When indicated, labeled SΔTM spikes were incubated with shACE2 as described (28), 300 μM of the indicated glycans for 30 min or 0.6 μM of the indicated mAb for 60 min before imaging. Concentrations of shACE2, the indicated glycans, and mAbs were maintained during imaging. smFRET data were collected using Micromanager v2.0 (101) at 25 frames/s. All smFRET data were processed and analyzed using the SPARTAN software package (https://scottcblanchardlab.com/software) in MATLAB (The Mathworks, Natick, MA) (102). smFRET traces were identified according to criteria previously described (28, 60). Traces meeting those criteria were then verified manually. Traces from each of three technical replicates were then compiled into FRET histograms, and the mean probability per histogram bin ± SE was calculated. Traces were idealized to a three-state HMM (two nonzero-FRET states and a zero-FRET state) using the maximum point likelihood algorithm (103) implemented in SPARTAN. The three-state model was previously selected by comparing the Akaike information criterion across multiple different models with a range of state numbers and topologies (28). The idealizations were used to determine the occupancies (fraction of time until photobleaching) in each FRET state and construct Gaussian distributions, which were overlaid on the FRET histograms to visualize the results of the HMM analysis. The distributions in occupancies were used to construct violin plots in MATLAB as well as calculate mean occupancy and SEs, as displayed in Fig. 7. Statistical significance measures were determined as indicated below.

Structural analysis

Protein structures (Protein Data Bank accession codes 7C2L and 7QUR) were visualized and analyzed using PyMOL software version 2.0.7 (Schrödinger Inc., New York, NY). The S ectodomain structures were aligned to residues 719 to 1035 in S2 with RMSD of 0.903 Å.

Statistical analysis

Datasets subjected to statistical analysis were first tested for normality using GraphPad Prism version 10.0.1 (GraphPad Software, Boston, MA, USA). This information was used to apply the appropriate indicated parametric one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) or nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis statistical test. Statistical significance measures (P values) of FRET state occupancies were determined by one-way ANOVA in MATLAB (The MathWorks, Waltham, MA, USA). This analysis displays the full breadth of dynamic behavior across the total population of traces analyzed. The total number of traces analyzed was sufficient to ensure minimally 85% statistical power during comparison of occupancy data from unbound to ligand-bound SΔTM (28). P values <0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance.

Acknowledgments

We thank T. Morrison (UMass Chan Medical School) for providing the HEK-293T-hACE2 cell line; B. K. Chen (Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai) for providing the plasmid encoding the HIV-1 molecular clone HIV-1 NL4-3 Gag-iGFP ΔEnv; P. Kwong (NIAID, NIH) for providing the molecular clones of mAb 17b heavy and light chains; and M. Nussenzweig (The Rockefeller University) for providing molecular clones of both hIgG1 and hIgKappa expression vectors. We also thank Y. Wang (MassBiologics, UMass Chan Medical School) for providing the antibodies MAb362IgA1, REGN10987, and REGN10933.

Funding: This work was supported by the UMass Chan Medical School COVID-19 Pandemic Relief Fund (J.B.M.) and the National Institutes of Health grants R01GM143773 and R01AI174645 (J.B.M.).

Author contributions: Conceptualization: M.A.D.-S. and J.B.M. Methodology: M.A.D.-S. and J.B.M. Investigation: M.A.D.-S. and A.J. Formal analysis: M.A.D.-S., A.J., and J.B.M. Software: J.B.M. Data curation: M.A.D.-S., A.J., and J.B.M. Visualization: M.A.D.-S., A.J., and J.B.M. Validation: M.A.D.-S., A.J., and J.B.M. Supervision: M.A.D.-S., N.D.D., and J.B.M. Resources: N.D.D. and J.B.M. Project administration: M.A.D.-S. and J.B.M. Funding acquisition: J.B.M. Writing—original draft: M.A.D.-S. and J.B.M. Writing—review and editing: All authors.

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials.

Supplementary Materials

This PDF file includes:

Figs. S1 to S5

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Zhou P., Yang X.-L., Wang X.-G., Hu B., Zhang L., Zhang W., Si H.-R., Zhu Y., Li B., Huang C.-L., Chen H.-D., Chen J., Luo Y., Guo H., Jiang R.-D., Liu M.-Q., Chen Y., Shen X.-R., Wang X., Zheng X.-S., Zhao K., Chen Q.-J., Deng F., Liu L.-L., Yan B., Zhan F.-X., Wang Y.-Y., Xiao G.-F., Shi Z.-L., A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature 579, 270–273 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoffmann M., Kleine-Weber H., Schroeder S., Krüger N., Herrler T., Erichsen S., Schiergens T. S., Herrler G., Wu N.-H., Nitsche A., Müller M. A., Drosten C., Pöhlmann S., SARS-CoV-2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell 181, 271–280.e8 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lan J., Ge J., Yu J., Shan S., Zhou H., Fan S., Zhang Q., Shi X., Wang Q., Zhang L., Wang X., Structure of the SARS-CoV-2 spike receptor-binding domain bound to the ACE2 receptor. Nature 581, 215–220 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Letko M., Marzi A., Munster V., Functional assessment of cell entry and receptor usage for SARS-CoV-2 and other lineage B betacoronaviruses. Nat. Microbiol. 5, 562–569 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shang J., Ye G., Shi K., Wan Y., Luo C., Aihara H., Geng Q., Auerbach A., Li F., Structural basis of receptor recognition by SARS-CoV-2. Nature 581, 221–224 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Walls A. C., Park Y.-J., Tortorici M. A., Wall A., McGuire A. T., Veesler D., Structure, function, and antigenicity of the SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein. Cell 181, 281–292.e6 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang Q., Zhang Y., Wu L., Niu S., Song C., Zhang Z., Lu G., Qiao C., Hu Y., Yuen K.-Y., Wang Q., Zhou H., Yan J., Qi J., Structural and functional basis of SARS-CoV-2 entry by using human ACE2. Cell 181, 894–904.e9 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wrapp D., Wang N., Corbett K. S., Goldsmith J. A., Hsieh C.-L., Abiona O., Graham B. S., McLellan J. S., Cryo-EM structure of the 2019-nCoV spike in the prefusion conformation. Science 367, 1260–1263 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yan R., Zhang Y., Li Y., Xia L., Guo Y., Zhou Q., Structural basis for the recognition of SARS-CoV-2 by full-length human ACE2. Science 367, 1444–1448 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhou T., Tsybovsky Y., Gorman J., Rapp M., Cerutti G., Chuang G.-Y., Katsamba P. S., Sampson J. M., Schön A., Bimela J., Boyington J. C., Nazzari A., Olia A. S., Shi W., Sastry M., Stephens T., Stuckey J., Teng I.-T., Wang P., Wang S., Zhang B., Friesner R. A., Ho D. D., Mascola J. R., Shapiro L., Kwong P. D., Cryo-EM structures of SARS-CoV-2 Spike without and with ACE2 reveal a pH-dependent switch to mediate endosomal positioning of receptor-binding domains. Cell Host Microbe 28, 867–879.e5 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cai Y., Zhang J., Xiao T., Peng H., Sterling S. M., WalshJr R. M., Rawson S., Rits-Volloch S., Chen B., Distinct conformational states of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. Science 369, 1586–1592 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tortorici M. A., Veesler D., Structural insights into coronavirus entry. Adv. Virus Res. 105, 93–116 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Walls A. C., Tortorici M. A., Snijder J., Xiong X., Bosch B.-J., Rey F. A., Veesler D., Tectonic conformational changes of a coronavirus spike glycoprotein promote membrane fusion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114, 11157–11162 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang J., Xiao T., Cai Y., Chen B., Structure of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. Curr. Opin. Virol. 50, 173–182 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chi X., Yan R., Zhang J., Zhang G., Zhang Y., Hao M., Zhang Z., Fan P., Dong Y., Yang Y., Chen Z., Guo Y., Zhang J., Li Y., Song X., Chen Y., Xia L., Fu L., Hou L., Xu J., Yu C., Li J., Zhou Q., Chen W., A neutralizing human antibody binds to the N-terminal domain of the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2. Science 369, 650–655 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McCallum M., Marco A. D., Lempp F. A., Tortorici M. A., Pinto D., Walls A. C., Beltramello M., Chen A., Liu Z., Zatta F., Zepeda S., di Iulio J., Bowen J. E., Montiel-Ruiz M., Zhou J., Rosen L. E., Bianchi S., Guarino B., Fregni C. S., Abdelnabi R., Foo S.-Y. C., Rothlauf P. W., Bloyet L.-M., Benigni F., Cameroni E., Neyts J., Riva A., Snell G., Telenti A., Whelan S. P. J., Virgin H. W., Corti D., Pizzuto M. S., Veesler D., N-terminal domain antigenic mapping reveals a site of vulnerability for SARS-CoV-2. Cell 184, 2332–2347.e16 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cerutti G., Guo Y., Zhou T., Gorman J., Lee M., Rapp M., Reddem E. R., Yu J., Bahna F., Bimela J., Huang Y., Katsamba P. S., Liu L., Nair M. S., Rawi R., Olia A. S., Wang P., Zhang B., Chuang G.-Y., Ho D. D., Sheng Z., Kwong P. D., Shapiro L., Potent SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibodies directed against spike N-terminal domain target a single supersite. Cell Host Microbe 29, 819–833.e7 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meng B., Datir R., Choi J., Bradley J. R., Smith K. G. C., Lee J. H., Gupta R. K., Baker S., Dougan G., Hess C., Kingston N., Lehner P. J., Lyons P. A., Matheson N. J., Owehand W. H., Saunders C., Summers C., Thaventhiran J. E. D., Toshner M., Weekes M. P., Maxwell P., Shaw A., Bucke A., Calder J., Canna L., Domingo J., Elmer A., Fuller S., Harris J., Hewitt S., Kennet J., Jose S., Kourampa J., Meadows A., O’Brien C., Price J., Publico C., Rastall R., Ribeiro C., Rowlands J., Ruffolo V., Tordesillas H., Bullman B., Dunmore B. J., Fawke S., Gräf S., Hodgson J., Huang C., Hunter K., Jones E., Legchenko E., Matara C., Martin J., Mescia F., O’Donnell C., Pointon L., Shih J., Sutcliffe R., Tilly T., Treacy C., Tong Z., Wood J., Wylot M., Betancourt A., Bower G., Cossetti C., Sa A. D., Epping M., Fawke S., Gleadall N., Grenfell R., Hinch A., Jackson S., Jarvis I., Krishna B., Nice F., Omarjee O., Perera M., Potts M., Richoz N., Romashova V., Stefanucci L., Strezlecki M., Turner L., Bie E. M. D. D. D., Bunclark K., Josipovic M., Mackay M., Allison J., Butcher H., Caputo D., Clapham-Riley D., Dewhurst E., Furlong A., Graves B., Gray J., Ivers T., Gresley E. L., Linger R., Meloy S., Muldoon F., Ovington N., Papadia S., Phelan I., Stark H., Stirrups K. E., Townsend P., Walker N., Webster J., Scholtes I., Hein S., King R., SARS-CoV-2 spike N-terminal domain modulates TMPRSS2-dependent viral entry and fusogenicity. Cell Rep. 40, 111220 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Qing E., Li P., Cooper L., Schulz S., Jäck H.-M., Rong L., Perlman S., Gallagher T., Inter-domain communication in SARS-CoV-2 spike proteins controls protease-triggered cell entry. Cell Rep. 39, 110786 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Otsubo R., Minamitani T., Kobiyama K., Fujita J., Ito T., Ueno S., Anzai I., Tanino H., Aoyama H., Matsuura Y., Namba K., Imadome K.-I., Ishii K. J., Tsumoto K., Kamitani W., Yasui T., Human antibody recognition and neutralization mode on the NTD and RBD domains of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. Sci. Rep. 12, 20120 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yurkovetskiy L., Wang X., Pascal K. E., Tomkins-Tinch C., Nyalile T. P., Wang Y., Baum A., Diehl W. E., Dauphin A., Carbone C., Veinotte K., Egri S. B., Schaffner S. F., Lemieux J. E., Munro J. B., Rafique A., Barve A., Sabeti P. C., Kyratsous C. A., Dudkina N. V., Shen K., Luban J., Structural and functional analysis of the D614G SARS-CoV-2 spike protein variant. Cell 183, 739–751.e8 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang Y., Xu C., Wang Y., Hong Q., Zhang C., Li Z., Xu S., Zuo Q., Liu C., Huang Z., Cong Y., Conformational dynamics of the Beta and Kappa SARS-CoV-2 spike proteins and their complexes with ACE2 receptor revealed by cryo-EM. Nat. Commun. 12, 7345 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang J., Cai Y., Xiao T., Lu J., Peng H., Sterling S. M., WalshJr R. M., Rits-Volloch S., Zhu H., Woosley A. N., Yang W., Sliz P., Chen B., Structural impact on SARS-CoV-2 spike protein by D614G substitution. Science 372, 525–530 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang Y., Liu C., Zhang C., Wang Y., Hong Q., Xu S., Li Z., Yang Y., Huang Z., Cong Y., Structural basis for SARS-CoV-2 Delta variant recognition of ACE2 receptor and broadly neutralizing antibodies. Nat. Commun. 13, 871 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ye G., Liu B., Li F., Cryo-EM structure of a SARS-CoV-2 omicron spike protein ectodomain. Nat. Commun. 13, 1214 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lu M., Uchil P. D., Li W., Zheng D., Terry D. S., Gorman J., Shi W., Zhang B., Zhou T., Ding S., Gasser R., Prévost J., Beaudoin-Bussières G., Anand S. P., Laumaea A., Grover J. R., Liu L., Ho D. D., Mascola J. R., Finzi A., Kwong P. D., Blanchard S. C., Mothes W., Real-time conformational dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 spikes on virus particles. Cell Host Microbe 28, 880–891.e8 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang Z., Han Y., Ding S., Shi W., Zhou T., Finzi A., Kwong P. D., Mothes W., Lu M., SARS-CoV-2 variants increase kinetic stability of open spike conformations as an evolutionary strategy. MBio 13, e03227–e03221 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Díaz-Salinas M. A., Li Q., Ejemel M., Yurkovetskiy L., Luban J., Shen K., Wang Y., Munro J. B., Conformational dynamics and allosteric modulation of the SARS-CoV-2 spike. eLife 11, e75433 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim S. Y., Jin W., Sood A., Montgomery D. W., Grant O. C., Fuster M. M., Fu L., Dordick J. S., Woods R. J., Zhang F., Linhardt R. J., Characterization of heparin and severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) spike glycoprotein binding interactions. Antiviral Res. 181, 104873 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang J., Petitjean S. J. L., Koehler M., Zhang Q., Dumitru A. C., Chen W., Derclaye S., Vincent S. P., Soumillion P., Alsteens D., Molecular interaction and inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 binding to the ACE2 receptor. Nat. Commun. 11, 4541 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Clausen T. M., Sandoval D. R., Spliid C. B., Pihl J., Perrett H. R., Painter C. D., Narayanan A., Majowicz S. A., Kwong E. M., McVicar R. N., Thacker B. E., Glass C. A., Yang Z., Torres J. L., Golden G. J., Bartels P. L., Porell R. N., Garretson A. F., Laubach L., Feldman J., Yin X., Pu Y., Hauser B. M., Caradonna T. M., Kellman B. P., Martino C., Gordts P. L. S. M., Chanda S. K., Schmidt A. G., Godula K., Leibel S. L., Jose J., Corbett K. D., Ward A. B., Carlin A. F., Esko J. D., SARS-CoV-2 infection depends on cellular heparan sulfate and ACE2. Cell 183, 1043–1057.e15 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hao W., Ma B., Li Z., Wang X., Gao X., Li Y., Qin B., Shang S., Cui S., Tan Z., Binding of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein to glycans. Sci. Bull. 66, 1205–1214 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]