Abstract

Objectives

Regulatory focus theory proposes 2 self-regulatory orientations: promotion focus – related to achieving aspirations and positive outcomes – and prevention focus – related to fulfilling responsibilities and preventing negative outcomes. The investigation examined whether regulatory focus and proximity to goal weight moderated the effectiveness of a weight-loss maintenance intervention.

Methods

Participants who lost ≥10% of their weight were assigned to guided or self-directed treatments and completed regulatory focus and weight goal measures.

Results

Across treatment groups, people who were more promotion-focused had better 2-year maintenance rates (defined as regain <25%) than people who were less promotion-focused, especially if far from their goal weight (.59 versus .44). In the guided group, people who were more prevention-focused had better maintenance rates than people who were less prevention-focused if closer to their goal weight (.69 versus .42), but poorer maintenance rates if farther from their goal (.36 versus .72). In the self-directed group, prevention focus was unrelated to maintenance.

Conclusions

Regulatory focus and proximity to goal weight moderated intervention effectiveness. Maintenance may be enhanced by tailoring treatments to regulatory focus and goal weight (eg, prevention-focused people far from their goals may need extra weight-loss support before focusing on maintenance).

Keywords: weight loss maintenance, regulatory focus

People who successfully initiate new behavioral routines to lose weight, such as a new exercise routine or structured meal plan, are generally unsuccessful in maintaining changes over time; therefore, identifying determinants of long-term weight loss maintenance is a critical need.1,2 Efforts to improve the sustained effect of weight loss treatment have included evaluating different diet and exercise prescriptions,3,4 self-control training,5,6 and reducing stresses induced by the weight-loss process.7–9 Although these approaches have shown promise, they have not proven effective enough to resolve the problem. A potential approach to provide insight into long-term weight maintenance and suggest strategies for future intervention is to examine the role of individual differences in self-regulation and personality.

Despite evidence that individual differences in self-regulation and personality influence health behaviors and outcomes,10–16 interventions to promote the maintenance of behavior change have paid relatively little attention to whether specific treatments might be more effective for certain groups of individuals. Furthermore, theory and research suggest that because people’s psychological dispositions influence how they process information and pursue goals, they alter the efficacy of behavior change interventions.17,18 Specific to weight loss, the 2 self-regulatory orientations specified by regulatory focus theory,19 promotion focus (related to achieving aspirations and maximizing positive outcomes) and prevention focus (related to fulfilling obligations and preventing negative outcomes), have been shown to be uniquely associated with people’s ability to initiate and maintain changes.12 The current investigation builds on these findings by examining the effects of regulatory focus in a study designed to encourage long-term weight loss maintenance (Project Keep It Off20,21). Although the intervention was effective in enhancing maintenance, results from the present investigation may lead to improved treatment by systematically identifying the intervention strategies and/or behavioral challenges that facilitate or hinder performance for certain types of people. By identifying who performed well and who struggled, insight can be gained into the behavior change process and intervention procedures can be enhanced by: (1) providing extra support and/or training to certain individuals; and (2) tailoring messages and procedures to capitalize on people’s natural inclinations and strengths.

The Roles of Regulatory Focus and Regulatory Fit in Weight Loss and Maintenance

Regulatory focus theory19 proposes that goal-directed behavior is regulated through 2 motivational systems – promotion and prevention. Promotion focus involves concerns for aspiration, growth, and accomplishment. Promotion-focused individuals eagerly pursue desired outcomes, performing well on tasks that involve seeking benefits.19,22 In the context of weight change, promotion focus can be characterized as eagerly pursuing weight goals in the service of attaining benefits such as an improved appearance, increased physical ability, or optimal health and well-being. Complementing promotion focus, prevention focus involves concerns for security, duty, and meeting obligations. Prevention-focused individuals are vigilant in avoiding undesired outcomes, performing well on tasks that involve monitoring for costs to preserve desired outcomes.19,22 In the context of weight change, prevention focus can be characterized as vigilantly pursuing weight goals in the service of avoiding negative outcomes such as disease, limited physical ability, or failing to fulfill one’s obligations to loved ones.

Regulatory fit theory23,24 emphasizes that beyond the value of a particular outcome (eg, weight loss), the manner by which a goal is pursued can influence one’s motivation to pursue a particular outcome. People feel a sense of “fit” when the strategies by which an outcome is pursued match their psychological dispositions, which in turn, increases their motivation for and satisfaction with the behaviors they are performing. Regulatory fit also may occur when one’s regulatory focus fits with a specific behavioral challenge. Rothman et al18,25 suggest that: (1) behavioral initiation is an approach-based process in that one strives to reduce the discrepancy between one’s current undesired state (eg, an unhealthy weight) and a new desired state (eg, a healthy weight); and (2) behavioral maintenance is an avoidance-based process in that success is marked by maintaining a discrepancy between one’s new desired state (eg, a healthy weight) and one’s old undesired state (eg, an unhealthy weight). Thus, promotion-focused people should be well suited to initiating changes that are focused on benefits, whereas prevention-focused people should be well suited to maintaining change as a means to preserve desired outcomes. Research in both the laboratory22 and field12,26 has supported these premises. Important to the present investigation, of successful losers (≥ 5% of initial weight), Fuglestad et al12 found that promotion-focused people performed well if they were far from their goal weights (ie, still striving to attain desired outcomes), whereas prevention-focused people performed well if they were close to their goal weights (ie, vigilantly preserving desired outcomes).

The Present Analysis

Project Keep It Off20,21 is a unique study in that participants all had lost weight – at least 10% of their weight in the past year – on their own initiative and were recruited for a 2-year study of weight loss maintenance. Participants were assigned randomly to a guided condition (regular phone coaching over the duration of the study) or a self-directed (ie, control) condition (2 phone coaching sessions in the first month). In Fuglestad et al,12 participants were recruited for a study of weight loss in which treatment conditions were similar in content and contact (ie, there was no control condition). Although the study did allow for analysis of maintenance, overall weight loss was modest and follow-up of successful losers was brief. The Keep It Off study provides opportunities to examine an extended follow-up of people who were able to lose a substantial amount of weight and to compare performance under varied treatment conditions. In this way, new and important questions can be answered. Does the effectiveness of weight maintenance treatment vary by regulatory focus? What is the role of regulatory focus in weight maintenance under relatively naturalistic conditions (ie, the self-directed condition)?

Based on prior findings,12 it was hypothesized that greater promotion focus would be related to more favorable weight outcomes, but that prevention focus would not be related to weight outcomes as a main effect (prior effects of prevention focus were limited to specific situations). Interactions with weight loss goals were expected such that promotion focus would be most beneficial for participants who were far from their weight goals at the start of the intervention and prevention focus would be beneficial for participants who were close to their weight goals at the start of the intervention. Schokker et al27 and Fuglestad et al26 suggest that successful behavior change is predicated upon possessing both the self-regulatory skills and regulatory focus that fit with a particular behavioral challenge. For example, in a study of smoking cessation,26 people who were prevention-focused and high in self-efficacy (skills) were particularly likely to avoid lapses after initial success (a vigilance task that fits with prevention focus). In the present study, the guided condition should engender the requisite self-regulatory skills needed for successful weight control. Therefore, it was expected that the hypothesized effects of regulatory focus and weight goals (ie, promotion focus would be most beneficial for people far from their goals; prevention focus would benefit those close to their goals) would be more apparent in the guided condition relative to the self-directed condition.

METHODS

Participants and Procedures

Adults from the St. Paul/Minneapolis metropolitan area who had intentionally lost at least 10% of their body weight in the past year were recruited to participate in an intervention to promote weight loss maintenance. During screening calls, staff described the study and asked questions to assess eligibility (875 people were assessed). Informed consent was obtained during baseline visits. Overall, 419 participants (82% women; 87% Whites; age M=47 years; BMI M= 28; percent weight loss M=16%) were assigned randomly to guided or self-directed treatment conditions. The self-directed condition included a 2-session phone course with trained study staff in the first month after randomization to teach participants about strategies to keep off weight. Participants in this group received a course book (covering topics such as menu planning, physical activity, and relapse prevention) and a self-monitoring logbook to track their eating, physical activity, and weight. In the first phase of the guided condition, participants completed 10 biweekly phone sessions with trained study staff focused on developing key behaviors and skills for weight loss maintenance. Each session focused on a different topic such as menu planning, overcoming barriers to physical activity and healthy eating, and relapse prevention. In the second phase, guided participants completed 8 monthly phone coaching sessions and then 6 bimonthly sessions. During the second phase, guided participants also received tailored written feedback based on whether they were maintaining, losing, or gaining weight. Data at 24 months were available for most participants (85% in the guided group; 89% in the self-directed group). Sherwood et al20,21 provide additional details concerning intervention details and results.

Measures

Weights

Participants were weighed in light clothing without shoes at baseline (M=175.9 lbs, SD=35.5), and at 12 months (M=179.4 lbs, SD= 38.1) and 24 months (M= 184.6 lbs, SD=39.9). Participants provided self-reported weights at months 6 (M=176.4 lbs, SD=36.8) and 18 (M=182.4 lbs, SD=39.3), which were corrected for underreporting to the magnitudes observed in study participants of matched weight and sex.28 Missing weights were addressed in the following manner. If participants had observed weights before and after the unobserved value, missing weights were imputed by linear interpolation. Following Wing et al,6 missing weights of participants not observed again were imputed using a 3.96-lb. weight gain every 6 months. To assess rates of maintenance, an a priori dichotomous criterion was assessed at the end of the study: gaining < 25% of previously lost weight (45% maintainers at 24 months).

Goal weight discrepancy

Participants indicated their dream weights at baseline and a discrepancy was computed between baseline and dream weights (M=31.2 lbs, SD=24.3). Higher scores indicate greater discrepancy (ie, farther from one’s goal). This variable also was dichotomized to classify people as at/close to their goals (within 15 lbs; N = 117) or far from their goals (> 15 lbs away; N = 297). Other classification schemes were considered (eg, 10 or 20 lb. cut-points) and results were similar. A cut-point of 15 was chosen to obtain a close group that also was as close to their goals as possible with a relatively large number of people (eg, a 10-lb cut-point yielded a close group of just 67).

Regulatory focus

Dispositional promotion (α=.81, M=4.29, SD=0.71) and prevention focus (α=.76, M=3.99, SD=1.02) were measured at 24 months using the Regulatory Focus Questionnaire.29 The measure consisted of 11 items (5 prevention, 6 promotion) asking participants to indicate using a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (never or seldom) to 7 (very often) how often they have experienced specific events. Higher scores indicate greater previous success in promotion and prevention self-regulation. Promotion and prevention scores were positively correlated (r=.14, p=.006). Scores on the RFQ have been shown to be stable over 2 months29 and unaffected by situational manipulations.13 Furthermore, in a weight loss intervention (Fuglestad et al, unpublished data) mean promotion and prevention scores did not change over 6 months, and scores at baseline were highly correlated with scores at 6 months (promotion: r=.70, p < .001; prevention: r=.82, p < .001); moreover, and important to the present analysis, changes in promotion and prevention were not correlated with changes in weight.

Because the RFQ was measured at the end of the study, some participants (N = 49) did not complete it. Across a set of indicators measured at baseline, participants who did and did not complete the RFQ were not different in terms of sex, age, education, marital status, BMI, previously lost weight, treatment group assignment, social support, binge eating, and depression. Participants who completed the RFQ, relative to those who did not, were more likely to be white versus non-white (r=.12, p = .01) and had higher body image (r=.14, p = .003). Across follow-up, those who completed the RFQ were more likely to adhere to treatment calls (r=.22, p < .001), and gained less weight (r=−.15, p = .002).

Analysis Plan

For each regulatory focus (promotion and prevention) and weight outcome (weight change and 24-month maintenance), we performed 3 analyses. First, the main effect of regulatory focus was examined. Second, interactions of regulatory focus with goal discrepancy (ie, how far participants’ baseline weights were from their goals) were tested. Finally, analyses examined whether intervention condition moderated these effects. Longitudinal analysis of weight was conducted with SAS Proc Mixed using restricted maximum likelihood estimation. Logistic regression analysis of 24-month weight maintenance was conducted using SPSS. Analyses controlled for treatment group, age, sex, and education.

RESULTS

The Effect of Promotion Focus on Weight Change

Main effect

The main effect of promotion focus on weight was examined across the study via interactions with intercept and linear slope terms. As expected, the promotion focus by linear slope term was significant (Table 1). People who were more promotion-focused (evaluated at +1 SD) gained less weight over 2 years (estimated weight gain of 6.5 lbs) than people who were less promotion-focused (evaluated at −1 SD; estimated weight gain of 10.4 lbs).

Table 1.

Linear Mixed Models of Weight Change over 2 Years

| Model | Effect | Estimate | SE | Den. df | t-value | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Main Effects | Promotion Focus | |||||

| Intercept | −4.90 | 2.63 | 384 | −1.86 | .06 | |

| Slope | −0.69 | 0.22 | 1473 | −3.12 | .002 | |

| Prevention Focus | ||||||

| Intercept | 0.30 | 1.77 | 384 | 0.17 | .87 | |

| Slope | 0.63 | 0.15 | 1473 | 4.24 | .0001 | |

|

| ||||||

| Interactions with Goal Discrepancy | Promotion*Goal | |||||

| Intercept | −0.01 | 0.06 | 414 | −0.20 | .83 | |

| Slope | −0.01 | 0.008 | 1454 | −1.29 | .19 | |

| Prevention*Goal | ||||||

| Intercept | 0.04 | 0.04 | 414 | 0.94 | .35 | |

| Slope | 0.009 | 0.006 | 1454 | 1.48 | .14 | |

|

| ||||||

| Interactions with Goal Discrepancy and Treatment Group | Promotion* Goal*Tx | |||||

| Intercept | −0.04 | 0.14 | 408 | −0.30 | .77 | |

| Slope | −0.002 | 0.02 | 1449 | −0.12 | .91 | |

| Prevention* Goal* Tx | ||||||

| Intercept | −0.02 | 0.09 | 408 | −0.21 | .83 | |

| Slope | 0.04 | 0.01 | 1449 | 3.12 | .002 | |

Note.

Only effects of interest are shown, but all lower order terms were included in each model. Additionally, models controlled for treatment group, age, sex, and education. SE = standard error; Den. df = denominator degrees of freedom (all numerator df = 1).

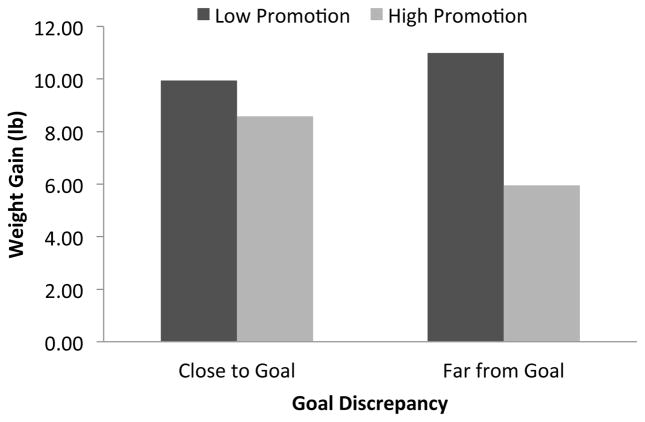

Moderating influence of goal discrepancy

It was hypothesized that promotion focus would be most beneficial for participants who were far from their weight loss goals. As data in Table 1 show, promotion focus did not significantly interact with goal discrepancy (analyzed continuously). To examine possible non-linear effects of goal discrepancy, stratified analyses were conducted with people close to (within 15 lbs) or far from their goals (> 15 lbs) as shown in Table 2. For people close to their goals, promotion focus was unrelated to weight change. However, of those far from their weight goals, people who were more promotion-focused gained less weight than people who were less promotion-focused. Figure 1 shows estimated 24-month weight gain by promotion focus for those close to and far from their goals. Of those far from their goal weights, people who were more promotion-focused gained less weight (6.0 lbs vs 11.0 lbs). The effect of promotion focus was attenuated for those close to their goals (more promotion-focused: 8.6 lbs; less promotion-focused: 9.9 lbs).

Table 2.

Linear Mixed Models of Weight Change Stratified by Proximity to Goal Weight

| Model | Effect | Estimate | SE | Den. df | t-value | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Close to Goal: Main Effects | Promotion Focus | |||||

| Intercept | 1.96 | 2.75 | 110 | 0.71 | .48 | |

| Slope | −0.24 | 0.32 | 417 | −.0.75 | .46 | |

| Prevention Focus | ||||||

| Intercept | 0.28 | 1.68 | 110 | 0.17 | .87 | |

| Slope | 0.44 | 0.19 | 417 | 2.29 | .02 | |

|

| ||||||

| Close to Goal: Interactions with Treatment Group | Promotion*Goal | |||||

| Intercept | −0.96 | 5.68 | 108 | −0.17 | .86 | |

| Slope | 0.10 | 0.64 | 415 | 0.15 | .88 | |

| Prevention*Goal | ||||||

| Intercept | 1.66 | 3.61 | 108 | 0.46 | .65 | |

| Slope | −0.92 | 0.41 | 415 | −2.26 | .02 | |

|

| ||||||

| Far from Goal: Main Effects | Promotion Focus | |||||

| Intercept | −4.72 | 2.99 | 272 | −1.58 | .12 | |

| Slope | −0.89 | 0.28 | 1033 | −3.12 | .002 | |

| Prevention Focus | ||||||

| Intercept | −1.55 | 2.09 | 272 | −0.74 | .46 | |

| Slope | 0.63 | 0.20 | 1033 | 3.16 | .002 | |

|

| ||||||

| Far from Goal: Interactions with Treatment Group | Promotion*Goal | |||||

| Intercept | 6.22 | 5.91 | 270 | 1.05 | .29 | |

| Slope | 0.26 | 0.56 | 1031 | 0.46 | .65 | |

| Prevention*Goal | ||||||

| Intercept | −0.70 | 4.19 | 270 | −0.17 | .87 | |

| Slope | 0.52 | 0.40 | 1031 | 1.31 | .19 | |

Note.

Only effects of interest are shown, but all lower order terms were included in each model. Additionally, models controlled for treatment group, age, sex, and education. SE = standard error; Den. df = denominator degrees of freedom (all numerator df = 1).

Figure 1.

Twenty-four Month Weight Gain by Promotion Focus (Evaluated at ±1 SD) for People Close to (within 15 lb) and Far from (> 15 lb away) Their Goal Weights

Moderating influence of treatment group

It was expected that the interaction of promotion focus and goal discrepancy would be more apparent in the guided versus self-directed condition. However, in examining weight over time, treatment group did not interact with promotion focus and goal discrepancy (Table 1). Furthermore, in stratified analyses, promotion did not interact with treatment group for those close to, or far from, their goals (Table 2).

The Effect of Promotion Focus on Maintaining Weight Loss

Main effect

Weight maintenance was examined using a dichotomous measure defined as weight gain < 25% of previously lost weight. Although the effect was marginal (Table 3), as expected, people who were more promotion-focused had a higher estimated probability of maintenance (.54) compared to those who were less promotion-focused (.44).

Table 3.

Logistic Regression Models of Maintaining Weight Loss at 2 Years

| Model | Effect | b | SE | Den. df | Wald | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Main Effects | Promotion Focus | 0.30 | 0.16 | 359 | 3.42 | .06 |

| Prevention Focus | −0.08 | 0.11 | 359 | 0.61 | .43 | |

|

| ||||||

| Interactions with Goal Discrepancy | Promotion*Goal | 0.004 | 0.007 | 356 | 0.37 | .54 |

| Prevention*Goal | −0.009 | 0.005 | 356 | 3.95 | .047 | |

|

| ||||||

| Interactions with Goal Discrepancy and Treatment Group | Promotion* Goal*Tx | 0.019 | 0.016 | 351 | 1.42 | .23 |

| Prevention* Goal* Tx | −0.025 | 0.011 | 351 | 5.36 | .02 | |

Note.

Only effects of interest are shown, but all lower order terms were included in each model. Additionally, models controlled for treatment group, age, sex, and education. SE = standard error; Den. df = denominator degrees of freedom (all numerator df = 1).

Moderating influence of goal discrepancy

The interaction of promotion focus and goal discrepancy (analyzed continuously) was unrelated to maintenance (Table 3). However, stratified analyses of goal discrepancy revealed that greater promotion focus was related to greater maintenance for people far from their goals (Table 4). Of those close to their goals, promotion focus was unrelated to maintenance (Table 4). Figure 2 shows estimated 24-month maintenance rates by promotion focus for those close to and far from their goal weights. Of those far from their goals, people who were more promotion-focused were more likely to maintain weight loss (estimated probability of .59) compared to people who were less promotion-focused (estimated probability of .44). Promotion focus was unrelated to maintenance for those close to their goals (more promotion-focused: .42; less promotion-focused: .46).

Table 4.

Logistic Regression Models of Maintaining Weight Loss Stratified by Proximity to Goal Weight

| Model | Effect | b | SE | Den. df | Wald | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Close to Goal: Main Effects | Promotion Focus | −0.12 | 0.34 | 99 | 0.12 | .73 |

| Prevention Focus | 0.17 | 0.21 | 99 | 0.67 | .42 | |

|

| ||||||

| Close to Goal: Interactions with Treatment Group | Promotion*Tx | −0.49 | 0.79 | 97 | 0.39 | .54 |

| Prevention*Tx | 1.41 | 0.54 | 97 | 6.89 | .009 | |

|

| ||||||

| Far from Goal: Main Effects | Promotion Focus | 0.41 | 0.19 | 253 | 4.59 | .03 |

| Prevention Focus | −0.21 | 0.13 | 253 | 2.42 | .12 | |

|

| ||||||

| Far from Goal: Interactions with Treatment Group | Promotion*Tx | 0.05 | 0.38 | 251 | 0.02 | .89 |

| Prevention*Tx | −0.28 | 0.27 | 251 | 1.13 | .29 | |

Note.

Only effects of interest are shown, but all lower order terms were included in each model. Additionally, models controlled for treatment group, age, sex, and education. SE = standard error; Den. df = denominator degrees of freedom (all numerator df = 1).

Figure 2.

Twenty-four Month Maintenance Rates by Promotion Focus (Evaluated at ±1 SD) for People Close to (within 15 lb) and Far from (> 15lb away) Their Goal Weights

Moderating influence of treatment group

It was expected that the interaction of promotion focus and goal discrepancy would be more apparent in the guided versus self-directed group. However, the interaction of treatment group with promotion focus and goal discrepancy was unrelated to maintenance (Table 3). Furthermore, in stratified analyses, promotion focus did not interact with treatment group for those close to, or far from, their goal weights (Table 4).

The Effect of Prevention Focus on Weight Change

Main effect

Although it was expected that prevention focus would be unrelated to weight as a main effect, the prevention focus by linear slope term was significant (Table 1). People who were more prevention-focused (evaluated at +1 SD) gained more weight over 2 years (estimated weight gain of 11.0 lbs) than people who were less prevention-focused (evaluated at −1 SD; estimated weight gain of 5.9 lbs).

Moderating influence of goal discrepancy

It was expected that prevention focus would be beneficial for participants who were close to their goals. However, prevention focus did not interact with goal discrepancy (analyzed continuously; Table 1). Furthermore, in stratified analyses, greater prevention focus was related to greater weight gain for both those close to their goal weights and those far from their goal weights (Table 2).

Moderating influence of treatment group

As expected, the interaction of treatment group with prevention focus and goal discrepancy (analyzed continuously) was related to weight gain (Table 1). Stratified results were similar (Table 2). Figure 3 shows estimated 24-month weight gain by prevention focus (evaluated at ±1 SD), goal discrepancy (evaluated at ±1 SD), and treatment group. People who were more prevention-focused gained less weight in the guided (5.9 lbs) versus self-directed group (13.1 lbs) when they were close to their goal weights. Conversely, people who were less prevention-focused gained less weight in the guided (2.8 lbs) versus self-directed group (9.5 lbs) when they were far from their goal weights. Looking at the entire pattern of results in Figure 3, in the self-directed group, people who were more prevention-focused gained more weight than those who were less prevention-focused regardless of goal discrepancy (12.0 lbs vs 8.5 lbs). Of people who were close to their goals in the guided group, those who were more prevention-focused gained less weight than those who were less prevention-focused (5.9 lbs vs 6.7 lbs). Of people who were far from their goals in the guided group, those who were more prevention-focused gained more weight than those who were less prevention-focused (13.8 lbs vs 2.8 lbs).

Figure 3.

Twenty-four Month Weight Gain by Prevention Focus (Evaluated at ±1 SD), Goal Discrepancy (Evaluated at ±1 SD), and Treatment Group

The Effect of Prevention Focus on Maintaining Weight Loss

Main effect

Prevention focus was unrelated to 24-month maintenance rates (Table 3).

Moderating influence of goal discrepancy

As expected, the interaction of prevention focus with goal discrepancy (analyzed continuously) was related to maintenance (Table 3). Of people close to their goals, those who were more prevention-focused had higher estimated maintenance rates (.50) than those who were less prevention-focused (.43). Conversely, of people far from their goals, those who were more prevention-focused had lower estimated maintenance rates (.44) than those who were less prevention-focused (.59). In stratified analyses, prevention focus was unrelated to maintenance for those close to, or far from, their goals (Table 4).

Moderating influence of treatment group

As expected, the interaction of treatment group with goal discrepancy (analyzed continuously) and prevention focus was related to maintenance (Table 3). Stratified results were similar (Table 4). Figure 4 shows estimated 24-month maintenance rates by prevention focus (evaluated at ±1 SD), goal discrepancy (evaluated at ±1 SD), and treatment group. People who were more prevention-focused had higher maintenance rates in the guided (.68) versus self-directed group (.38) when they were close to their goal weights. Conversely, people who were less prevention-focused had higher maintenance rates in the guided (.71) versus self-directed group (.50) when they were far from their goal weights. Looking at the entire pattern of results in Figure 4, of people close to their goals in the guided group, people who were more prevention-focused had higher maintenance rates than those who were less prevention-focused (.68 versus .43). Of those far from their goals in the guided group, people who were more prevention-focused had lower maintenance rates than those who were less prevention-focused (.36 versus .71). In the self-directed group, prevention focus appeared to be unrelated to maintenance regardless of goal discrepancy.

Figure 4.

Twenty-four Month Maintenance Rates by Prevention Focus (Evaluated at ±1 SD), Goal Discrepancy (Evaluated at ±1 SD), and Treatment Group

DISCUSSION

Extending research on regulatory focus and behavior change, the role of regulatory focus was examined in a 2-year study of weight loss maintenance with people who had lost at least 10% of their weight on their own initiative (Project Keep It Off).20, 21 Results supported the premise that promotion and prevention focus would have unique effects on weight loss maintenance. Consistent with predictions, of people who were far from reaching their goal weights at baseline, those who were more promotion-focused gained less weight and were more likely to maintain weight loss compared those who were less promotion-focused. That is, having a promotion focus was beneficial for people who were still striving to lose additional weight. Contrary to expectation, this pattern of results did not vary by intervention group. Unexpectedly, greater prevention focus was related to greater weight gain over the course of the study (prevention focus was unrelated to rates of maintenance). However, this finding was qualified by treatment group and how far or close people were to their weight loss goals at baseline. In the self-directed group, greater prevention focus was related to greater weight gain (maintenance rates did not vary by prevention focus). As hypothesized, in the guided group, of people close to their weight loss goals, those who were more prevention-focused were more likely to maintain weight loss compared to those who were less prevention-focused. Unexpectedly, of people far from their weight loss goals and in the guided group, those who were more prevention-focused gained more weight and were less likely to maintain weight loss compared to those who were less prevention-focused.

Implications for Regulatory Focus and Behavior Change

Overall, the current findings are consistent with Fuglestad et al12 in that promotion focus was particularly beneficial for people who were far from their goals and prevention focus was beneficial for people who were close to their goals. However, important differences were observed. In Fuglestad et al,12 prevention focus was unrelated to maintenance for people who had lost weight, but were far from their goals. In the present study, for people who were far from their weight loss goals, prevention focus was actually detrimental to weight maintenance. Why might these prevention-focused people have difficulty in maintaining weight loss? Findings by Ståhl et al30 suggest that prevention-focused people become fatigued after sustained self-regulation. In the present study, all participants had lost at least 10% of their body weight before entering the study, suggesting that they had been engaging in considerable self-regulation. Furthermore, conditions of non-fit (ie, when strategy by which an outcome is pursued does not match one’s psychological/motivational disposition) can result in poorer functioning.26,31,32 It may be that the incongruence between the intervention strategy provided (a maintenance focus) and people’s readiness for maintenance (still far from weight loss goals) did not work well for people who were prevention-focused. Perhaps these people became overwhelmed by the onset of weight gain after having worked to achieve significant weight loss. On the other hand, people who were prevention-focused benefitted from the intervention when they were presumably ready for maintenance (close to their weight goals).

Consistent with prior research,12 the findings also suggest that the behavioral domain of weight control is predominantly promotion-focused. Promotion focus was beneficial for maintaining weight loss over 2 years, especially for people who were far from their goals. Because it is generally difficult to reach a goal weight and successful weight control entails mastering a number of difficult self-monitoring, dietary, activity, and lifestyle behaviors, the initiation phase of weight control would seem to be rather protracted. Promotion focus appears to be particularly beneficial for gaining mastery over newly enacted behaviors in the face of obstacles and unpleasant experiences. Further suggesting that weight control is compatible with a promotion focus, promotion-focused people performed well regardless of treatment condition.

Implications for Intervention

Although strategies to improve weight loss maintenance by improving self-control skills,6 prescribing specific diets3 or alleviating stresses of the weight control process8 have shown promise, they have not proven effective enough to resolve the problem of maintaining weight loss. Another potential approach to improving maintenance is to consider individual differences in regulatory focus and to identify for whom an intervention approach is and is not beneficial. People who were prevention-focused did not benefit from the present intervention when they were far from their weight loss goals. Tailored intervention efforts may be warranted for prevention-focused people who have lost weight, but are still far from their goals. One approach would be to tailor procedures to match a prevention focus (eg, emphasizing safety, duty, vigilance, and the costs of not performing target behaviors). A number of studies have shown success in tailoring procedures to people’s stable psychological dispositions to promote changes in diet14,32 and physical activity.13,33 Specific to regulatory focus, Latimer et al13,14 demonstrated that promotion-focused messages (emphasizing accomplishment and benefits) were more effective in increasing physical activity and fruit and vegetable intake for promotion-focused people relative to prevention-focused people, whereas prevention-focused messages (emphasizing safety and avoiding costs) were more effective for prevention-focused people relative to promotion-focused people. Although these studies are encouraging, the effects only have been demonstrated for relatively short-term behavioral outcomes, and not for weight loss or maintenance. It remains to be seen whether emphasizing duty and security and monitoring for costs and pitfalls would lead to better outcomes for prevention-focused people who are far from their weight loss goals. Taking another approach, these people may just need extra attention and support at this point of the behavior change process.

The present study examined the effects of promotion and prevention focus independently, but the tailoring studies discussed above examined regulatory focus in terms of the relative dominance of promotion or prevention (using a difference score between promotion and prevention). In this way, people were classified as relatively more promotion-focused or prevention-focused. It should be noted that a difference score is problematic in that someone who is high on both promotion and prevention will look similar to someone who is low on both dimensions. In the present study, and consistent with results reported above, the interaction of regulatory focus (analyzed as a difference score) with goal discrepancy and treatment group was related to weight gain and maintenance rates. For example, of prevention-focused people, those in the guided group who were close to their weight loss goals had higher estimated maintenance rates (.68) relative to those close to their goals in the self-directed group (.37) and those who were far from their goals (guided=.32; self-directed=.40). Conversely, of promotion-focused people, those in the guided group who were far from their goals had higher estimated maintenance rates (.75) relative to those far from their goals in the self-directed group (.54) and those who were close to their goals (guided=.44; self-directed=.43). This analysis suggests that the intervention was most beneficial for prevention-focused people who were close to their goals and promotion-focused people who were far from their goals. Therefore, one strategy might be to provide extra intervention support to prevention-focused people who are far from their goals and promotion-focused people who are close to their goals.

Strengths, Limitations, and Future Directions

A clear strength of this investigation was that the role of regulatory focus in weight loss maintenance was examined over 2 years. Furthermore, the study allowed for examination of these effects under conditions of minimal intervention and more extensive intervention. Through this examination it was revealed that promotion-focused people performed well, especially if far from their goals, regardless of treatment condition. On the other hand, prevention-focused people who were close to their goals benefitted from more extensive intervention, but prevention-focused people who were far from their goals struggled regardless of condition. A limitation of the study was that regulatory focus was measured at the end of follow-up. Although this is a concern, the measure of regulatory focus used in the study was designed to measure stable individual differences and has been shown to be stable over context and time, including over a 6-month weight loss intervention.13,29 Furthermore, the complex pattern of results is consistent with prior investigations that measured regulatory focus at the beginning of the intervention.12 Another limitation of the study was that the sample was largely female and white, making generalizations to other populations difficult.

Although we were able to identify under which conditions promotion and prevention focus were beneficial and detrimental, the underlying mechanisms are not known. In future investigations it will be important establish the psychological (eg, perceptions of difficulty, emotional reactions to lapses, satisfaction with outcomes) and behavioral mediators (eg, intentional weight control strategies, mindless eating, physical activity) through which regulatory dispositions influence weight control. In this way, tailored interventions could strategically address relevant psychological and behavioral mediators. Building on studies that have used tailoring to promote change in diet and physical activity,13,14 a clear next step is to use these principles to promote weight loss/maintenance. The present findings suggest that taking into account self-regulatory dispositions and proximity to goal weights has the potential to help people deal with particularly difficult challenges by appealing to dispositional strengths that could encourage satisfaction with the behavior change process and lead to successful maintenance.

Human Subjects Statement

The study was reviewed and approved by the Health Partners Institutional Review Board.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Cancer Institute Grant R01CA128211 and by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Award T32DK083250.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement

Authors declare no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Paul T. Fuglestad, Department of Psychology, University of North Florida, Jacksonville, FL.

Alexander J. Rothman, Department of Psychology, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN.

Robert W. Jeffery, Division of Epidemiology and Community Health, School of Public Health, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN.

Nancy E. Sherwood, Health Partners Institute for Education and Research, Bloomington, MN.

References

- 1.Jeffery RW, Epstein LH, Wilson GT, et al. Long-term maintenance of weight loss: current status. Health Psychol. 2000;19(1 Suppl):5–16. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.19.suppl1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sarwer DB, von Sydow Green A, Vetter ML, et al. Behavior therapy for obesity: where are we now? Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2009;16(5):347–352. doi: 10.1097/MED.0b013e32832f5a79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Larsen TM, Dalskov S-M, van Baak M, et al. Diets with high or low protein content and glycemic index for weight-loss maintenance. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(22):2102–2113. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1007137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wadden TA, Foster GD, Letizia KA. One-year behavioral treatment of obesity: comparison of moderate and severe caloric restriction and the effects of weight maintenance therapy. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1994;62(1):165–171. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.62.1.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Svetkey LP, Stevens VJ, Brantley PJ, et al. Comparison of strategies for sustaining weight loss: the weight loss maintenance randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008;299(10):1139–1148. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.10.1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wing RR, Tate DF, Gorin AA, et al. A self-regulation program for maintenance of weight loss. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(15):1563–1571. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cooper Z, Doll HA, Hawker DM, et al. Testing a new cognitive behavioural treatment for obesity: a randomized controlled trial with three-year follow-up. Behav Res Ther. 2010;48(8):706–713. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2010.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lillis J, Hayes SC, Bunting K, et al. Teaching acceptance and mindfulness to improve the lives of the obese: a preliminary test of a theoretical model. Ann Behav Med. 2009;37(1):58–69. doi: 10.1007/s12160-009-9083-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Linde J, Simon G, Ludman E, et al. A randomized controlled trial of behavioral weight loss treatment versus combined weight loss/depression treatment among women with comorbid obesity and depression. Ann Behav Med. 2011;41(1):119–130. doi: 10.1007/s12160-010-9232-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bogg T, Roberts BW. Conscientiousness and health-related behaviors: a meta-analysis of the leading behavioral contributors to mortality. Psychol Bull. 2004;130(6):887–919. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.130.6.887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bogg T, Roberts BW. The case for conscientiousness: evidence and implications for a personality trait marker of health and longevity. Ann Behav Med. 2013;45(3):278–288. doi: 10.1007/s12160-012-9454-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fuglestad PT, Rothman AJ, Jeffery RW. Getting there and hanging on: the effect of regulatory focus on performance in smoking and weight loss interventions. Health Psychol. 2008;27(3 Suppl):S260–S270. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.3(suppl.).s260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Latimer AE, Rivers SE, Rench TA, et al. A field experiment testing the utility of regulatory fit messages for promoting physical activity. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2008;44(3):826–832. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2007.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Latimer AE, Williams-Piehota P, Katulak NA, et al. Promoting fruit and vegetable intake through messages tailored to individual differences in regulatory focus. Ann Behav Med. 2008;35(3):363–369. doi: 10.1007/s12160-008-9039-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sutin AR, Ferrucci L, Zonderman AB, et al. Personality and obesity across the adult life span. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2011;101(3):579–592. doi: 10.1037/a0024286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Williams P, Thayer J. Executive functioning and health: introduction to the special series. Ann Behav Med. 2009;37(2):101–105. doi: 10.1007/s12160-009-9091-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Latimer AE, Katulak NA, Mowad L, et al. Motivating cancer prevention and early detection behaviors using psychologically tailored messages. J Health Commun. 2005;10(Suppl 1):137–155. doi: 10.1080/10810730500263364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rothman AJ, Baldwin AS, Hertel AW, et al. Self-regulation and behavior change: disentangling behavioral initiation and behavioral maintenance. In: Vohs KD, Baumeister RF, editors. Handbook of Self-regulation: Research, Theory, and Applications. 2. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2011. pp. 106–122. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Higgins ET. Beyond pleasure and pain. Am Psychol. 1997;52(12):1280–1300. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.52.12.1280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sherwood NE, Crain AL, Martinson BC, et al. Keep It Off: a phone-based intervention for long-term weight-loss maintenance. Contem Clin Trials. 2011;32(4):551–560. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2011.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sherwood NE, Crain AL, Martinson BC, et al. Enhancing long-term weight loss maintenance: 2-year results from the Keep It Off randomized controlled trial. Prev Med. 2013;56(3–4):171–177. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2012.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brodscholl JC, Kober H, Higgins ET. Strategies of self-regulation in goal attainment versus goal maintenance. Eur J Soc Psychol. 2007;37(4):628–648. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Higgins ET. Making a good decision: value from fit. Am Psychol. 2000;55(11):1217–1230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Higgins ET. Value from regulatory fit. [Accessed June 21, 2015];Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2005 14(4):209–213. Available at: http://www.columbia.edu/cu/psychology/higgins/papers/higgins2005currentdirections.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rothman AJ. Toward a theory-based analysis of behavioral maintenance. Health Psychol. 2000;19(1 Suppl):64–69. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.19.suppl1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fuglestad PT, Rothman AJ, Jeffery RW. The effects of regulatory focus on responding to and avoiding slips in a longitudinal study of smoking cessation. Basic Appl Soc Psych. 2013;35(5):426–435. doi: 10.1080/01973533.2013.823619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schokker MC, Keers JC, Bouma J, et al. The impact of social comparison information on motivation in patients with diabetes as a function of regulatory focus and self-efficacy. Health Psychol. 2010;29(4):438–445. doi: 10.1037/a0019878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Spencer EA, Appleby PN, Davey GK, et al. Validity of self-reported height and weight in 4808 EPIC–Oxford participants. Public Health Nutr. 2002;5(04):561–565. doi: 10.1079/PHN2001322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Higgins ET, Friedman RS, Harlow RE, et al. Achievement orientations from subjective histories of success: promotion pride versus prevention pride. Eur J Soc Psychol. 2001;31(1):3–23. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ståhl T, Van Laar C, Ellemers N. The role of prevention focus under stereotype threat: Initial cognitive mobilization is followed by depletion. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2012;102(6):1239–1251. doi: 10.1037/a0027678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spiegel S, Grant-Pillow H, Higgins ET. How regulatory fit enhances motivational strength during goal pursuit. Eur J Soc Psychol. 2004;34(1):39–54. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tam L, Bagozzi RP, Spanjol J. When planning is not enough: the self-regulatory effect of implementation intentions on changing snacking habits. Health Psychol. 2010;29(3):284–292. doi: 10.1037/a0019071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gallagher KM, Updegraff JA. When ‘fit’ leads to fit, and when ‘fit’ leads to fat: how message framing and intrinsic vs. extrinsic exercise outcomes interact in promoting physical activity. Psychol Health. 2011;26(7):819–834. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2010.505983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]