Abstract

Purpose

We conducted a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial to evaluate the effect of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) and peptide vaccination (PV) on relapse-free survival (RFS) and overall survival (OS) in patients with resected high-risk melanoma.

Patients and Methods

Patients with completely resected stage IV or high-risk stage III melanoma were grouped by human leukocyte antigen (HLA) -A2 status. HLA-A2–positive patients were randomly assigned to receive GM-CSF, PV, both, or placebo; HLA-A2–negative patients, GM-CSF or placebo. Treatment lasted for 1 year or until recurrence. Efficacy analyses were conducted in the intent-to-treat population.

Results

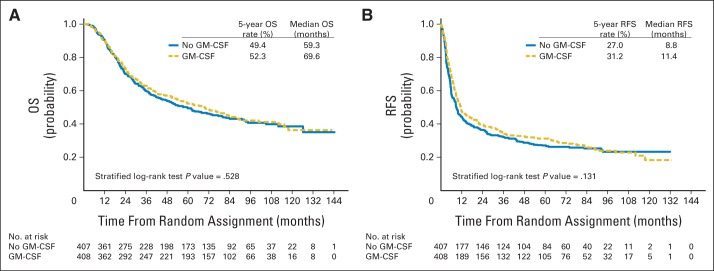

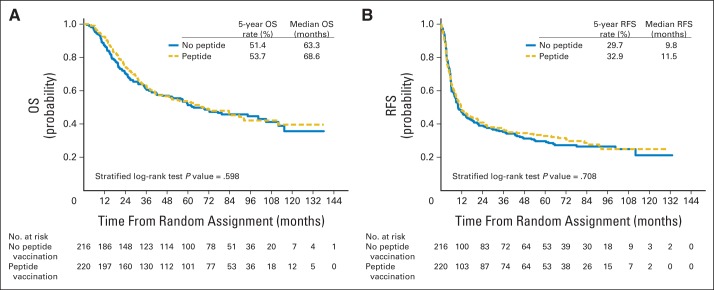

A total of 815 patients were enrolled. There were no significant improvements in OS (stratified log-rank P = .528; hazard ratio, 0.94; 95% repeated CI, 0.77 to 1.15) or RFS (P = .131; hazard ratio, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.74 to 1.04) in the patients assigned to GM-CSF (n = 408) versus those assigned to placebo (n = 407). The median OS times with GM-CSF versus placebo treatments were 69.6 months (95% CI, 53.4 to 83.5 months) versus 59.3 months (95% CI, 44.4 to 77.3 months); the 5-year OS probability rates were 52.3% (95% CI, 47.3% to 57.1%) versus 49.4% (95% CI, 44.3% to 54.3%), respectively. The median RFS times with GM-CSF versus placebo were 11.4 months (95% CI, 9.4 to 14.8 months) versus 8.8 months (95% CI, 7.5 to 11.2 months); the 5-year RFS probability rates were 31.2% (95% CI, 26.7% to 35.9%) versus 27.0% (95% CI, 22.7% to 31.5%), respectively. Exploratory analyses showed a trend toward improved OS in GM-CSF–treated patients with resected visceral metastases. When survival in HLA-A2–positive patients who received PV versus placebo was compared, RFS and OS were not significantly different. Treatment-related grade 3 or greater adverse events were similar between GM-CSF and placebo groups.

Conclusion

Neither adjuvant GM-CSF nor PV significantly improved RFS or OS in patients with high-risk resected melanoma. Exploratory analyses suggest that GM-CSF may be beneficial in patients with resected visceral metastases; this observation requires prospective validation.

INTRODUCTION

Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) is a well-tolerated cytokine with activities that suggest a possible role in cancer immunotherapy.1 It increases the number of monocytes/macrophages in patients with cancer 2 and, in vitro, enhances their ability to lyse tumor cells.3 GM-CSF has a clear role in the growth and maturation of dendritic cells.4 It may also have antiangiogenic activity.5

Early clinical trials support the possible benefit of GM-CSF as adjuvant therapy for melanoma. Spitler et al6 reported longer overall survival (OS) of 48 patients with stage III to IV melanoma treated for 1 year with adjuvant GM-CSF compared with historical controls (median OS, 37.5 v 12.2 months; 2-year survival, 64% v 15%). A subsequent single-arm trial in 98 patients with stage II, III, or IV melanoma evaluated GM-CSF for 3 years and demonstrated 5-year melanoma-specific survival rates of 67% and 40% among patients with resected stage III and IV disease, respectively.7 A retrospective study of 317 patients with resected stage III melanoma reported a median melanoma-specific survival of 102 months for patients treated with GM-CSF versus 99 months for patients under observation only and respective 10-year survival rates of 49% versus 39% (P = .08).8 Subset analysis showed that OS was statistically significantly improved in patients with stage IIIC disease. Forty-two patients with stage IIIB to IIIC or IV disease who were enrolled on a biomarker study and treated with GM-CSF had a median OS of 65 months.9

Administration of cytokines, including GM-CSF, with melanoma vaccines has shown augmented immunologic responses and clinically significant antitumor responses in some studies.10–12 A multicenter, randomized, phase II study (E1696) evaluated the effect of systemically administered GM-CSF or interferon-alfa-2b (IFN-α-2b) on responses to a multiepitope peptide vaccine, composed of the same peptides used in this trial, in patients with active metastatic melanoma. The ability to mount an immune response to at least one vaccinating peptide was predictive of improved survival.13 There were positive but nonsignificant trends toward enhancement of the immune response with both GM-CSF and IFN-α-2b.

We conducted a multicenter, intergroup, randomized, placebo-controlled, phase III trial to evaluate the ability of GM-CSF and/or multiepitope peptide vaccination (PV) to improve relapse-free survival (RFS) and OS in patients with completely resected high-risk stage III to IV melanoma.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patient Eligibility

Patients gave informed consent after approval by the human investigations committee. Patients were randomly assigned within 16 weeks of complete resection of high-risk melanoma, defined as locoregional recurrence after prior adjuvant IFN-α-2b or relapse from the biochemotherapy arm of study S000814; local recurrence after adequate resection of the primary tumor; clinically evident satellite or in-transit disease; stage III disease with gross extracapsular extension; recurrence in a previously resected nodal basin; four or greater involved lymph nodes or matted lymph nodes if ineligible for study S0008; ulcerated primary melanoma and any involved lymph nodes; or completely resected stage IV disease. Patients with cutaneous, uveal, or mucosal primaries were eligible. Other eligibility criteria are in the Data Supplement.

Random Assignment and Treatment

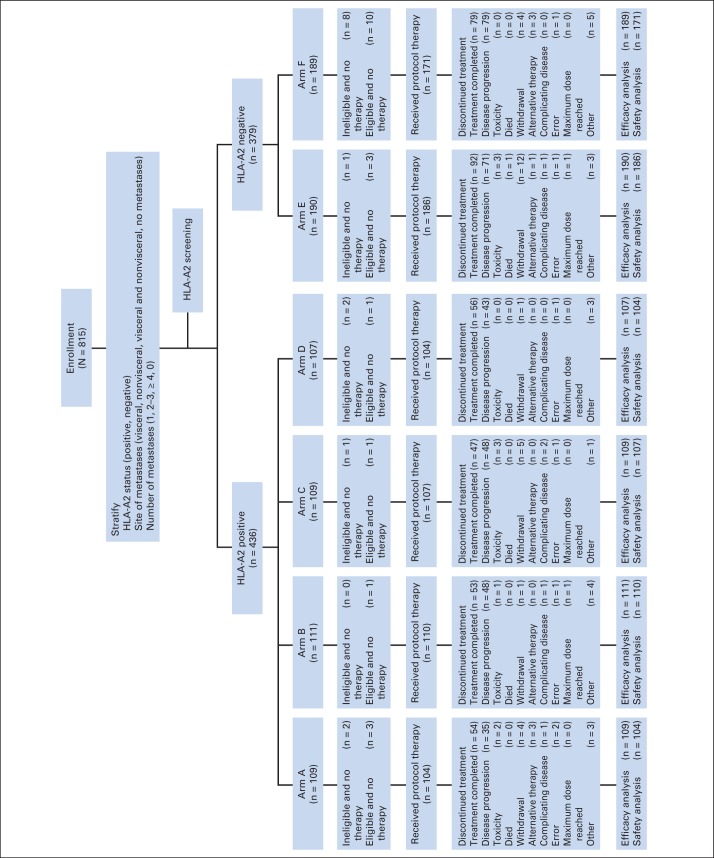

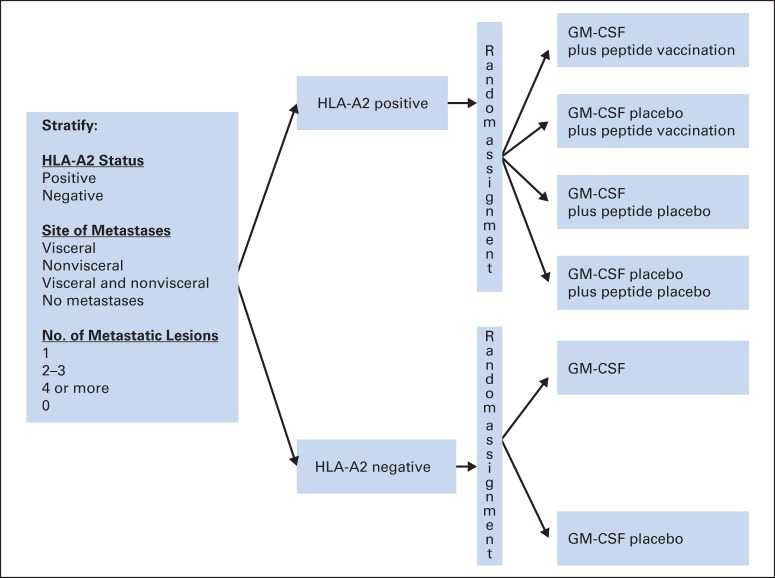

Because the PVs used in this trial are only immunologically recognized in the context of human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-A2, patients were separated into HLA-A2–positive (serologically defined) and HLA-A2–negative groups (Fig 1, CONSORT diagram; Fig 2). HLA-A2–positive patients were randomly assigned to receive GM-CSF plus PV, GM-CSF placebo plus PV, GM-CSF plus peptide placebo, or GM-CSF placebo plus peptide placebo. HLA-A2–negative patients were randomly assigned to receive GM-CSF or placebo. Random assignment was conducted centrally by using permuted blocks within strata, defined by the following: HLA-A2 status (positive or negative), site of metastases (nonvisceral v visceral v both sites v none), and number of metastatic lesions (0, 1, 2 to 3, ≥ 4).

Fig 1.

CONSORT diagram. HLA, human leukocyte antigen.

Fig 2.

Study schema. GM-CSF, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor; HLA, human leukocyte antigen.

GM-CSF (sargramostim) 250 μg/d and GM-CSF placebo were administered subcutaneously on day 1 through 14 of each 28-day cycle. The multiepitope vaccine was composed of tyrosinase 368-376(370D), gp100 209-217(210M), and MART-1(27-35) peptides. Peptides and respective peptide placebos were emulsified in Montanide ISA-51 (Seppic, Puteaux, France) and administered separately via two subcutaneous injections into three different sites on days 1 and 15 of cycle 1 and day 1 of subsequent cycles. During the study, the Montanide preparation was changed to one with no animal products. Patients received 13 cycles of treatment unless they experienced disease progression or unacceptable toxicity. Patients with resectable recurrences before completion of 12 months of treatment were encouraged to resume treatment for an additional 6 months or until a total of 12 months of treatment, whichever was longest. All patients were observed for RFS and OS for 15 years from the date of registration.

End Points

The primary objective was to compare RFS and OS between GM-CSF and placebo in the entire population. The main secondary objective was to compare RFS of peptide vaccine (PV-positive) and placebo (PV-negative) groups in HLA-A2–positive patients. OS was defined as time from random assignment to death as a result of any cause. RFS was defined as time from random assignment to first disease recurrence or death. Adverse events (AEs) were coded and graded according to National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, version 2.

Statistical Analysis

A total of 800 patients and 400 deaths were required for 80% power to detect a 33% increase in the median OS of patients treated with GM-CSF versus placebo (projected survival, 53.2 v 40 months, respectively), by stratified log-rank test with a two-sided type I error of .05. Interim analyses of OS, detailed in the Data Supplement, were performed semi-annually; they began when approximately 25% of the planned full information became available and continued until criteria for early stopping were met or full information was reached. The September 2009 interim analysis showed an improvement in RFS (hazard ratio [HR], 0.82; 95% CI, 0.69 to 0.98; P = .03) but not OS (HR, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.75 to 1.16; P = .55). These data were submitted as an abstract to the 46th Annual Meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology in 2010. By the time of presentation, a repeat analysis showed that the difference in RFS was no longer significant.15 At the time of OS monitoring, interim analysis was also conducted for RFS to compare PV versus placebo groups in HLA-A2–positive patients.

All OS and RFS analyses were based on the intent-to-treat population regardless of eligibility status. OS and RFS distributions were estimated by using the Kaplan-Meier method, with 95% CIs calculated with Greenwood's formula. Stratified log-rank tests were used to compare distributions of OS and RFS between groups. Stratified Cox proportional hazard models were conducted to estimate HRs for the treatment effect for OS and RFS. The Jennison-Turnbull repeated CI was calculated for the OS comparison between GM-CSF and placebo and the RFS comparison between PV and placebo. Proportional hazards assumption was examined by the Schoenfeld residuals method.

As an exploratory analysis, effects of GM-CSF and PV on OS and RFS were evaluated in subgroups of patients on the basis of prespecified factors: HLA-A2 status, visceral or nonvisceral metastases, and number of metastases. Because the staging system was undergoing revision at the time the study was written, stage was not a prespecified stratification factor. When the seventh edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer Staging Manual was published in 2010, patients were centrally staged. Because the analysis of prespecified stratification factors suggested that the effects might differ on the basis of whether resected disease was visceral or nonvisceral, the effects of GM-CSF and PV were examined separately on patients with stage III-M1a and stage M1b or M1c disease. The significance of the predictive value of these factors was tested by including a treatment-by-factor interaction term in the Cox proportional hazards models. No adjustment was made for multiple comparisons for subgroup analysis because of the exploratory nature of these analyses. Analyses of AEs were conducted in the 782 patients who received at least one dose of protocol therapy (n = 777 patients reported treatment data). The incidence of grade 3 or higher AEs was summarized and compared between arms by using Fisher's exact tests.

All reported P values were for two-sided tests. The nominal two-sided significance levels were less than .001 (corresponding upper boundary value, 2.05) for the OS comparison between GM-CSF and placebo and less than .001 (corresponding upper boundary value, 2.02) for the RFS comparison between PV and placebo. For all other analyses, the two-sided significance level was .05.

Blood samples for correlative studies were collected and shipped to the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Central Immunology Laboratory, University of Pittsburgh (Pittsburgh, PA); these results will be reported separately.

RESULTS

Baseline and Treatment Characteristics

This study accrued 815 patients between December 29, 1999, and October 31, 2006; 436 (53.5%) were HLA-A2 positive and 379 (46.5%) were HLA-A2 negative. Table 1 displays on-study patient demographics and disease characteristics. Thirty patients had primary mucosal melanoma and 11 had primary uveal melanoma. Treatment arms were well balanced regarding known prognostic factors. At study entry, 38.6% of patients had stage IV disease; 26.5% had two or more metastatic sites resected; 33.7% had prior adjuvant immunotherapy, and 11.9% had prior radiotherapy.

Table 1.

Patient Demographics and Disease Characteristics in All Patients

| Variable | Arm |

Total |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A |

B |

C |

D |

E |

F |

|||||||||

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| No. of patients (N = 815) | 109 | 110 | 109 | 107 | 190 | 189 | 815 | |||||||

| Age, years | ||||||||||||||

| Mean (SD) | 60.1 (13.3) | 56.4 (14.2) | 58.2 (13.0) | 58.8 (13.6) | 59.2 (13.7) | 57.6 (12.9) | 58.4 (13.4) | |||||||

| Median (range) | 60 (27-83) | 56 (22-82) | 57 (23-87) | 58 (23-82) | 60 (19-88) | 57 (19-87) | 58 (19-88) | |||||||

| Sex (n = 814) | ||||||||||||||

| Male | 61 | 56.0 | 66 | 59.0 | 64 | 59.0 | 68 | 64.0 | 112 | 59.3 | 112 | 59.0 | 483 | 59.3 |

| Female | 48 | 44.0 | 45 | 40.5 | 45 | 41.3 | 39 | 36.5 | 77 | 40.7 | 77 | 40.7 | 331 | 40.7 |

| Ethnicity | ||||||||||||||

| White | 102 | 93.6 | 103 | 92.8 | 105 | 96.3 | 97 | 90.7 | 172 | 90.5 | 167 | 88.4 | 746 | 91.5 |

| Other | 3 | 2.8 | 2 | 1.8 | 1 | 0.9 | 3 | 2.8 | 3 | 1.6 | 7 | 3.7 | 19 | 2.3 |

| Pre-NCI* | 4 | 3.7 | 6 | 5.4 | 3 | 2.8 | 7 | 6.5 | 15 | 7.9 | 15 | 7.9 | 50 | 6.1 |

| ECOG performance status (n = 811) | ||||||||||||||

| 0 | 91 | 85.1 | 95 | 86.4 | 89 | 81.7 | 80 | 74.8 | 149 | 78.8 | 154 | 81.5 | 658 | 81.1 |

| 1 | 16 | 15.0 | 15 | 13.6 | 20 | 18.3 | 27 | 25.2 | 40 | 21.2 | 35 | 18.5 | 153 | 18.9 |

| T of primary tumor: Breslow, mm (n = 616) | ||||||||||||||

| ≤ 0.75 | 6 | 7.1 | 11 | 13.3 | 5 | 6.0 | 4 | 4.9 | 14 | 9.8 | 8 | 5.8 | 48 | 7.8 |

| 0.76-1.50 | 22 | 25.9 | 11 | 13.3 | 17 | 20.2 | 25 | 30.5 | 26 | 18.2 | 31 | 22.5 | 132 | 21.4 |

| 1.51-4.0 | 38 | 44.7 | 34 | 41.0 | 45 | 53.6 | 37 | 45.1 | 72 | 50.4 | 72 | 52.2 | 298 | 48.4 |

| ≥ 4.1 | 19 | 22.4 | 27 | 32.5 | 17 | 20.2 | 16 | 19.5 | 31 | 21.7 | 27 | 19.6 | 137 | 22.2 |

| N: nodal involvement of primary tumor (n = 670) | ||||||||||||||

| No regional node | 64 | 70.3 | 61 | 70.1 | 61 | 68.5 | 53 | 62.4 | 107 | 66.9 | 103 | 65.2 | 449 | 67.0 |

| 1 Regional node with diameter ≤ 3 cm | 16 | 17.6 | 18 | 20.7 | 18 | 20.2 | 25 | 29.4 | 36 | 22.5 | 44 | 27.9 | 157 | 23.4 |

| 1 Node with diameter > 3 cm | 6 | 6.6 | 4 | 4.6 | 6 | 6.7 | 4 | 4.7 | 10 | 6.3 | 8 | 5.1 | 38 | 5.7 |

| Multiple nodes | 5 | 5.5 | 4 | 4.6 | 4 | 4.5 | 3 | 3.5 | 7 | 4.4 | 3 | 1.9 | 26 | 3.9 |

| M: metastatic involvement of primary tumor (n = 703) | ||||||||||||||

| No distant mets | 87 | 93.6 | 84 | 90.3 | 83 | 89.3 | 79 | 88.8 | 151 | 89.4 | 155 | 93.4 | 639 | 90.9 |

| Skin or subcutaneous | 2 | 2.2 | 8 | 8.6 | 6 | 6.5 | 6 | 6.7 | 13 | 7.7 | 6 | 3.6 | 41 | 5.8 |

| Visceral | 4 | 4.3 | 1 | 1.1 | 4 | 4.3 | 4 | 4.5 | 5 | 3.0 | 5 | 3.0 | 23 | 3.3 |

| Depth of invasion (Clark) of primary tumor (n = 591) | ||||||||||||||

| Above basal lamina | 2 | 2.4 | 1 | 1.3 | 3 | 3.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 2.2 | 2 | 1.5 | 11 | 1.9 |

| Extension into papillary dermis | 3 | 3.7 | 7 | 8.8 | 7 | 8.4 | 8 | 10.0 | 4 | 3.0 | 7 | 5.3 | 36 | 6.1 |

| Interface papillary-reticular dermis | 19 | 23.2 | 18 | 22.5 | 11 | 13.3 | 18 | 23.1 | 28 | 20.7 | 21 | 15.8 | 115 | 19.5 |

| Reticular dermis | 44 | 53.7 | 43 | 53.8 | 50 | 60.2 | 42 | 53.9 | 77 | 57.0 | 88 | 66.2 | 344 | 58.2 |

| Subcutaneous fat | 14 | 17.1 | 11 | 13.8 | 12 | 14.5 | 10 | 12.8 | 23 | 17.0 | 15 | 11.3 | 85 | 14.4 |

| Disease stage at study entry (n = 766) | ||||||||||||||

| IIIA | 2 | 1.94 | 1 | 0.93 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.97 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.56 | 5 | 0.7 |

| IIIB | 29 | 28.2 | 31 | 29.0 | 32 | 33.0 | 32 | 31.1 | 48 | 27.1 | 44 | 24.6 | 216 | 28.2 |

| IIIC | 32 | 31.1 | 37 | 34.6 | 30 | 30.9 | 31 | 30.1 | 57 | 32.2 | 62 | 34.6 | 249 | 32.5 |

| M1a | 17 | 16.5 | 9 | 8.4 | 9 | 9.3 | 14 | 13.6 | 35 | 19.8 | 24 | 13.4 | 108 | 14.1 |

| M1b | 14 | 13.6 | 17 | 15.9 | 15 | 15.5 | 12 | 11.7 | 23 | 13.0 | 29 | 16.2 | 110 | 14.4 |

| M1c | 9 | 8.7 | 12 | 11.2 | 11 | 11.3 | 13 | 12.6 | 14 | 7.9 | 19 | 10.6 | 78 | 10.2 |

| III | 63 | 61.2 | 69 | 64.5 | 62 | 63.9 | 64 | 62.1 | 105 | 59.3 | 107 | 59.8 | 470 | 61.4 |

| IV | 40 | 38.8 | 38 | 35.5 | 35 | 36.1 | 39 | 37.9 | 72 | 40.7 | 72 | 40.2 | 296 | 38.6 |

| Primary tumor site (n = 717) | ||||||||||||||

| Head and neck | 16 | 17.2 | 15 | 15.5 | 23 | 23.5 | 17 | 18.1 | 33 | 19.9 | 27 | 16.0 | 131 | 18.3 |

| Upper limb | 14 | 15.1 | 15 | 15.5 | 18 | 18.4 | 15 | 16.0 | 29 | 17.5 | 31 | 18.3 | 122 | 17.0 |

| Lower limb | 27 | 29.0 | 17 | 17.5 | 20 | 20.4 | 22 | 23.4 | 27 | 16.3 | 33 | 19.5 | 146 | 20.4 |

| Subungual | 1 | 1.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 1.0 | 2 | 2.1 | 1 | 0.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 5 | 0.7 |

| Trunk | 31 | 33.3 | 41 | 42.3 | 24 | 24.5 | 30 | 31.9 | 55 | 33.1 | 55 | 32.5 | 236 | 32.9 |

| Anogenital | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.6 | 1 | 0.1 |

| Eye | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 1.0 | 1 | 1.0 | 1 | 1.1 | 3 | 1.8 | 5 | 3.0 | 11 | 1.5 |

| Mucosal | 2 | 2.2 | 4 | 4.1 | 8 | 8.2 | 3 | 3.2 | 9 | 5.4 | 3 | 1.8 | 29 | 4.1 |

| Other | 2 | 2.2 | 4 | 4.1 | 3 | 3.1 | 4 | 4.3 | 9 | 5.4 | 14 | 8.3 | 36 | 5.0 |

| No. of positive nodes at primary presentation (n = 693) | ||||||||||||||

| 0 | 65 | 69.2 | 57 | 64.0 | 65 | 69.9 | 55 | 63.2 | 111 | 67.3 | 108 | 65.5 | 461 | 66.5 |

| 1-3 | 23 | 24.5 | 26 | 29.2 | 25 | 26.9 | 26 | 29.9 | 43 | 26.1 | 46 | 27.9 | 189 | 27.3 |

| ≥ 4 | 6 | 6.4 | 6 | 6.7 | 3 | 3.2 | 6 | 6.9 | 11 | 6.7 | 11 | 6.7 | 43 | 6.2 |

| Pigmentation histology of primary tumor (n = 508) | ||||||||||||||

| Amelanotic | 7 | 10.0 | 6 | 8.2 | 6 | 9.5 | 10 | 14.9 | 17 | 14.9 | 19 | 15.7 | 65 | 12.8 |

| Melanotic | 63 | 90.0 | 67 | 91.8 | 57 | 90.5 | 57 | 85.1 | 97 | 85.1 | 102 | 84.3 | 443 | 87.2 |

| Ulceration histology of primary tumor (n = 578) | ||||||||||||||

| No | 42 | 55.3 | 56 | 70.0 | 40 | 52.0 | 49 | 63.6 | 69 | 51.5 | 84 | 62.7 | 340 | 58.8 |

| Yes | 34 | 44.7 | 24 | 30.0 | 37 | 48.1 | 28 | 36.4 | 65 | 48.5 | 50 | 37.3 | 238 | 41.2 |

| Lymphoid infiltration of primary tumor (n = 474) | ||||||||||||||

| Absent | 47 | 70.2 | 37 | 57.8 | 40 | 63.5 | 42 | 58.3 | 63 | 63.0 | 75 | 69.4 | 304 | 64.1 |

| Sparse focal infiltrate | 18 | 26.9 | 20 | 31.3 | 19 | 30.2 | 23 | 31.9 | 22 | 22.0 | 26 | 24.1 | 128 | 27.0 |

| Dense or prominent | 2 | 3.0 | 7 | 10.9 | 4 | 6.4 | 7 | 9.7 | 15 | 15.0 | 7 | 6.5 | 42 | 8.9 |

| Current evidence of disease (n = 704) | ||||||||||||||

| No | 90 | 98.9 | 93 | 97.9 | 90 | 98.9 | 88 | 98.9 | 164 | 98.2 | 169 | 99.4 | 694 | 98.6 |

| Yes | 1 | 1.1 | 2 | 2.1 | 1 | 1.1 | 1 | 1.1 | 3 | 1.8 | 1 | 0.6 | 9 | 1.3 |

| Matted lymph nodes (n = 630) | ||||||||||||||

| No | 75 | 96.2 | 75 | 89.3 | 83 | 97.7 | 77 | 97.5 | 148 | 95.5 | 144 | 96.6 | 602 | 95.6 |

| Yes | 3 | 3.9 | 9 | 10.7 | 2 | 2.4 | 2 | 2.5 | 7 | 4.5 | 5 | 3.4 | 28 | 4.4 |

| Previous therapy | ||||||||||||||

| Immunotherapy (n = 697) | 35 | 38.5 | 42 | 43.8 | 39 | 42.9 | 36 | 40.9 | 56 | 33.7 | 67 | 40.6 | 275 | 39.5 |

| Chemotherapy (n = 696) | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 2.1 | 5 | 5.5 | 2 | 2.3 | 3 | 1.8 | 11 | 6.7 | 23 | 3.3 |

| Radiation therapy (n = 698) | 6 | 6.6 | 17 | 17.7 | 13 | 14.3 | 10 | 11.2 | 27 | 16.3 | 24 | 14.6 | 97 | 13.9 |

| Surgical treatment for melanoma | ||||||||||||||

| Initial biopsy (n = 668) | 80 | 91.0 | 77 | 84.6 | 79 | 91.0 | 75 | 87.0 | 140 | 89.7 | 132 | 83.0 | 583 | 87.3 |

| Resection of primary (n = 674) | 79 | 88.8 | 80 | 86.0 | 77 | 88.5 | 74 | 86.1 | 144 | 90.6 | 135 | 84.4 | 589 | 87.4 |

| Lymphatic mapping (n = 650) | 22 | 27.5 | 31 | 34.1 | 22 | 25.9 | 25 | 30.5 | 48 | 30.8 | 56 | 35.9 | 204 | 31.4 |

| Sentinel lymph node biopsy (n = 671) | 45 | 53.6 | 40 | 43.5 | 39 | 43.3 | 43 | 50.6 | 80 | 50.0 | 87 | 54.4 | 334 | 49.8 |

| Resection of local skin recurrence (n = 676) | 24 | 27.3 | 28 | 30.1 | 21 | 24.7 | 24 | 27.6 | 31 | 19.1 | 35 | 21.7 | 163 | 24.1 |

| Resection of regional recurrence (n = 672) | 25 | 28.4 | 26 | 28.3 | 19 | 22.1 | 21 | 24.4 | 30 | 18.4 | 38 | 24.2 | 159 | 23.7 |

| Sentinel lymph node dissection (n = 672) | 20 | 22.7 | 23 | 25.0 | 17 | 19.3 | 24 | 27.6 | 46 | 28.9 | 44 | 27.9 | 174 | 25.9 |

| Regional lymph node dissection (n = 687) | 52 | 57.8 | 58 | 61.7 | 56 | 62.2 | 46 | 53.5 | 105 | 63.6 | 99 | 61.1 | 416 | 60.6 |

| Resection of nonvisceral distant recurrence (n = 673) | 18 | 20.5 | 23 | 25.0 | 16 | 18.6 | 23 | 27.1 | 39 | 24.1 | 31 | 19.4 | 150 | 22.3 |

| Resection of visceral distant recurrence (n = 683) | 16 | 17.8 | 17 | 18.1 | 18 | 20.7 | 11 | 12.8 | 21 | 12.9 | 34 | 20.9 | 117 | 17.1 |

| Other current/prior malignancy (n = 697) | ||||||||||||||

| No | 80 | 87.9 | 75 | 79.0 | 80 | 87.9 | 80 | 88.9 | 139 | 83.7 | 144 | 87.8 | 598 | 85.8 |

| Yes | 11 | 12.1 | 20 | 21.1 | 11 | 12.1 | 10 | 11.0 | 27 | 16.3 | 20 | 12.2 | 99 | 14.2 |

| History of disease | ||||||||||||||

| Cardiovascular/pulmonary (n = 808) | 57 | 53.3 | 62 | 56.4 | 51 | 46.8 | 54 | 50.5 | 97 | 51.6 | 108 | 57.8 | 429 | 53.1 |

| Immunologic dysfunction (n = 795) | 1 | 1.0 | 6 | 5.5 | 4 | 3.7 | 2 | 1.9 | 4 | 2.1 | 6 | 3.3 | 23 | 2.9 |

| Neurologic/psychiatric (n = 801) | 30 | 28.6 | 32 | 29.1 | 29 | 26.9 | 30 | 28.6 | 50 | 26.6 | 50 | 27.0 | 221 | 27.6 |

| Cancer other than melanoma (n = 801) | 14 | 13.1 | 19 | 17.3 | 9 | 8.5 | 11 | 10.5 | 23 | 12.2 | 16 | 8.7 | 92 | 11.5 |

| Renal: history of dysfunction (n = 800) | 12 | 11.4 | 2 | 1.8 | 7 | 6.5 | 6 | 5.7 | 13 | 6.9 | 11 | 6.0 | 51 | 6.4 |

| Hepatic: history of dysfunction (n = 799) | 6 | 5.7 | 4 | 3.7 | 4 | 3.7 | 4 | 3.9 | 4 | 2.1 | 7 | 3.8 | 29 | 3.6 |

| Gastrointestinal (n = 804) | 30 | 28.3 | 28 | 25.5 | 34 | 31.2 | 29 | 27.6 | 51 | 27.0 | 49 | 26.5 | 221 | 27.5 |

| Endocrinologic (n = 797) | 81 | 77.1 | 91 | 83.5 | 88 | 82.2 | 87 | 82.9 | 144 | 77.0 | 162 | 88.0 | 144 | 18.1 |

| Genitourinary (n = 800) | 29 | 27.6 | 20 | 18.2 | 14 | 13.1 | 20 | 19.1 | 38 | 20.2 | 35 | 18.9 | 156 | 19.5 |

| Dermatologic (n = 800) | 30 | 28.6 | 21 | 19.1 | 23 | 21.5 | 23 | 21.9 | 42 | 22.3 | 22 | 11.9 | 161 | 20.1 |

| Musculoskeletal (n = 800) | 30 | 28.6 | 39 | 35.5 | 32 | 29.9 | 23 | 21.9 | 52 | 27.7 | 55 | 29.7 | 231 | 28.9 |

| Stratification factors used for random assignment | ||||||||||||||

| HLA-A2 | ||||||||||||||

| Positive | 109 | 100.0 | 111 | 100.0 | 109 | 100.0 | 107 | 100.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 436 | 53.5 |

| Negative | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 190 | 100.0 | 189 | 100.0 | 379 | 46.5 |

| Site of metastases | ||||||||||||||

| Visceral | 18 | 16.5 | 17 | 15.3 | 19 | 17.4 | 19 | 17.8 | 31 | 16.3 | 37 | 19.6 | 141 | 17.3 |

| Nonvisceral | 75 | 68.8 | 79 | 71.2 | 73 | 67.0 | 75 | 70.1 | 136 | 71.6 | 131 | 69.3 | 569 | 69.8 |

| Visceral and nonvisceral | 2 | 1.8 | 4 | 3.6 | 2 | 1.8 | 3 | 2.8 | 2 | 1.1 | 2 | 1.1 | 15 | 1.8 |

| No | 14 | 12.8 | 11 | 9.9 | 15 | 13.8 | 10 | 9.4 | 21 | 11.1 | 19 | 10.1 | 90 | 11.0 |

| No. of metastatic lesions | ||||||||||||||

| 1 | 67 | 61.5 | 71 | 64.0 | 70 | 64.2 | 69 | 64.5 | 121 | 63.7 | 124 | 65.6 | 522 | 64.1 |

| 2-3 | 20 | 18.4 | 18 | 16.2 | 18 | 16.5 | 20 | 18.7 | 30 | 15.8 | 34 | 18.0 | 140 | 17.2 |

| ≥ 4 | 7 | 6.4 | 7 | 6.3 | 6 | 5.5 | 7 | 6.5 | 14 | 7.4 | 11 | 5.8 | 52 | 6.4 |

| 0 | 15 | 13.8 | 15 | 13.5 | 15 | 13.8 | 11 | 10.3 | 25 | 13.2 | 20 | 10.6 | 101 | 12.4 |

NOTE. P = .02 for history of dermatologic disease by Fisher's exact test; P > .05 for all other binary or categoric variables by Fisher's exact test; P > .05 for age by analysis of variance test. Arms: A, GM-CSF plus PV; B, GM-CSF placebo plus PV; C, GM-CSF plus PV placebo; D, GM-CSF placebo and PV placebo; E, GM-CSF; F, GM-CSF placebo.

Abbreviations: ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; GM-CSF, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor; HLA, human leukocyte antigen; NCI, National Cancer Institute; PV, peptide vaccination; SD, standard deviation.

Prior to the requirement for reporting the ethnicity of participants.

Of 815 patients, 75 were ineligible and 33 did not start protocol therapy (detailed in Data Supplement). Most of the reasons for ineligibility involved interpretation of the complex eligibility requirements. One was a pathologic misdiagnosis, which is not a rare occurrence in melanoma. Treatment data were reported for 777 of 782 treated patients (for treatment characteristics, see the Data Supplement). The median number of treatment cycles completed was 12 (range, 1 to 19 cycles). Approximately half of the patients (381 of 777; similar across arms) completed all 13 cycles of protocol therapy. Administration of protocol therapy was similar in all arms. Treatment beyond 13 cycles was allowed for patients with resected recurrences; 47 patients received more than 13 cycles; two completed 19 cycles.

Relapse was the main reason in all arms for treatment discontinuation before completion. Nine patients stopped protocol treatment because of toxicity. Other reasons, including deaths (unrelated to treatment or disease) and patient withdrawal, were similar in all arms. Figure 1 displays the CONSORT diagram for the study as of October 8, 2012.

OS and RFS by GM-CSF in Intent-to-Treat Population

As of October 8, 2012, 443 of 815 patients had died. A total of 327 (73.8%) died as a result of melanoma; 33 (7.5%), as a result of other causes; and 83 (18.7%), as a result of unspecified causes (Data Supplement). The median follow-up time was 82.1 months (range, 0 to 144.2 months) for the 372 surviving patients.

The median OS was 10.3 months longer in patients who received GM-CSF than in those who received GM-CSF placebo (69.6 v 59.3 months; 17.4% improvement). This was less than the projected absolute increase of 13.3 months and the relative improvement of 33% required for significance (HR, 0.94; 95% repeated CI, 0.77 to 1.15; stratified log-rank P = .528; Table 2; Fig 3A; Data Supplement). The 5-year OS probability was 52.3% (95% CI, 47.3% to 57.1%) in GM-CSF–treated patients and 49.4% (95% CI, 44.3% to 54.3%) in GM-CSF placebo–treated patients.

Table 2.

Median Time and 5-Year Rate of OS and RFS

| Group | OS |

RFS |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Events/No. of Patients | Median (range) Time, Months | 5-Year Rate, % (95% CI) | P* | No. of Events/No. of Patients | Median (range) Time, Months | 5-Year Rate, % (95% CI) | P* | |

| GM-CSF | .53 | .13 | ||||||

| No | 222/407 | 59.3 (44.4-77.3) | 49.4 (44.3 to 54.3) | 296/407 | 8.8 (7.5-11.2) | 27.0 (22.7 to 31.5) | ||

| Yes | 221/408 | 69.6 (53.4-83.5) | 52.3 (47.3 to 57.1) | 295/408 | 11.4 (9.4-14.8) | 31.2 (26.7 to 35.9) | ||

| PV | .60 | .71 | ||||||

| No | 115/216 | 63.3 (49.2-105.0) | 51.4 (44.4 to 58.0) | 156/216 | 9.8 (7.7-15.5) | 29.7 (23.4 to 36.0) | ||

| Yes | 114/220 | 68.6 (47.0-92.3) | 53.7 (46.7 to 60.2) | 151/220 | 11.5 (8.7-20.4) | 32.9 (26.6 to 39.3) | ||

| Treatment arm | ||||||||

| HLA-A2 positive | .88 | .91 | ||||||

| A | 55/109 | 72.1 (41.3-NR) | 55.5 (45.4 to 64.5) | 76/109 | 12.8 (9.0-22.0) | 32.4 (23.6 to 41.5) | ||

| B | 59/111 | 63.7 (36.3-NR) | 51.9 (42.0 to 61.0) | .44† | 75/111 | 10.0 (5.8-25.4) | 33.2 (24.4 to 42.2) | .59† |

| C | 59/109 | 69.3 (34.8-115.4) | 51.1 (41.2 to 60.1) | .43† | 79/109 | 10.0 (7.4-20.9) | 31.3 (22.8 to 40.2) | .78† |

| D | 56/107 | 62.2 (39.1-105.0) | 51.6 (41.4 to 60.9) | .77† | 77/107 | 9.8 (5.9-19.0) | 28.0 (19.7 to 36.9) | .43† |

| HLA-A2 negative | .69 | .13 | ||||||

| E | 107/190 | 69.9 (45.2-82.7) | 51.2 (43.8 to 58.2) | 140/190 | 11.0 (8.6-18.2) | 30.6 (24.1 to 37.3) | ||

| F | 107/189 | 51.4 (37.3-79.9) | 46.7 (39.3 to 53.8) | 144/189 | 8.4 (6.2-9.7) | 22.9 (17.1 to 29.2) | ||

| No PV | .84 | .47 | ||||||

| Arms E + F | 214/379 | 57.9 (44.4-76.4) | 49.0 (43.8 to 54.0) | 284/379 | 9.2 (8.4-11.4) | 26.7 (22.3 to 31.3) | ||

| Arms C + D | 115/216 | 63.3 (49.2-105.0) | 51.4 (44.4 to 58.0) | 156/216 | 9.8 (7.7-15.5) | 29.7 (23.7 to 36.0) | ||

| Arm C v E | .97 | .90 | ||||||

| Arm D v F | .68 | .36 | ||||||

NOTE. Arms: A, GM-CSF plus PV; B, GM-CSF placebo plus PV; C, GM-CSF plus PV placebo; D, GM-CSF placebo and PV placebo; E, GM-CSF; F, GM-CSF placebo.

Abbreviations: GM-CSF, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor; HLA, human leukocyte antigen; NR, not reached; OS, overall survival; PV, peptide vaccination; RFS, relapse-free survival.

P values were from a stratified log-rank test. The stratification factors for the GM-CSF comparison were HLA-A2 status, site of metastases, and number of metastatic lesions. For the peptide vaccine comparison, the stratification factors were GM-CSF, site of metastases, and number of metastatic lesions. For all other comparisons, the stratification factors were site of metastases and number of metastatic lesions.

P values were for pairwise comparisons between arms B, C, D, and A (reference group) in HLA-A2–positive patients.

Fig 3.

Kaplan-Meier plot of (A) overall survival (OS) and (B) relapse-free survival (RFS) by granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF).

Five hundred sixty-seven patients experienced disease recurrence, and 24 died without recurrence (Data Supplement), for a total of 591 RFS events among the 815 patients. The median RFS was 11.4 months (95% CI, 9.4 to 14.8 months) in GM-CSF–treated patients and 8.8 months (95% CI, 7.5 to 11.2 months) in GM-CSF placebo–treated patients: an increase of 2.6 months, or 30% (HR, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.74 to 1.04; stratified log-rank P = .131; Table 2; Fig 3B; Data Supplement). The 5-year RFS probability was 31.2% (95% CI, 26.7% to 35.9%) in GM-CSF–treated patients and was 27.0% (95% CI, 22.7% to 31.5%) in GM-CSF placebo–treated patients.

OS and RFS With PV in HLA-A2–Positive Patients

Of 436 HLA-A2–positive patients, 220 were randomly assigned to receive PV (n = 109, with GM-CSF; n = 111, without), and 216 received PV placebo (n = 109, with GM-CSF; n = 107, without).

There were a total of 229 deaths (Data Supplement). The median OS time was 68.6 months (95% CI, 47.0 to 92.3 months) in patients who received PV and 63.3 months (95% CI, 49.2 to 105.0 months) in PV placebo–treated patients (HR, 0.93; 95% CI 0.71 to 1.21; P = .598; Table 2; Fig 4A; Data Supplement).

Fig 4.

Kaplan-Meier plot of (A) overall survival (OS) and (B) relapse-free survival (RFS) by peptide vaccination in human leukocyte antigen A2–positive patients.

There were 307 RFS events (n = 316 events with full information) in the 436 HLA-A2–positive patients (Data Supplement). The median RFS time was 11.5 months (95% CI, 8.7 to 20.4 months) for PV-treated patients and 9.8 months (95% CI, 7.7 to 15.5 months) for PV placebo–treated patients (HR, 0.96; 95% repeated CI, 0.74 to 1.23; P = .708; Table 2; Fig 4B; Data Supplement.

Effect of HLA Status on OS and RFS in All Patients

Neither OS nor RFS was significantly different between HLA-A2–positive and –negative patients, regardless of treatment (median OS, 68.6 v 57.9 months, respectively [P = .519; Data Supplement]; median RFS, 11.3 v 9.2 months, respectively [P = .285; Data Supplement]).

Effect of Systemic GM-CSF on Clinical Response to PV

The median OS for HLA-A2–positive patients who received GM-CSF plus PV was 72.1 months compared with 63.7, 69.3, and 62.2 months for peptide alone, GM-CSF alone, and placebo, respectively (Data Supplement). This difference was not statistically significant (P = .881).

Exploratory Subgroup Analyses of OS and RFS

The analysis of treatment effects by the three stratification factors (HLA-A2 status, site of metastases, and number of metastatic lesions) suggested a possible interaction between treatment with GM-CSF and whether the resected metastases were visceral or nonvisceral.

After publication of the seventh edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer Staging Manual in 2010, 766 patients were centrally staged according to that system. In an exploratory manner not prespecified in the protocol, the effect of GM-CSF was evaluated by stage of disease at study entry. No effect of GM-CSF on RFS or OS was observed in patients with stage IIIA, IIIB, or IIIC/M1a disease (data not shown). For patients with resected, stage M1b or M1c tumors (with visceral metastases), the median RFS time was 10.2 months for those treated with GM-CSF versus 5.8 months for those treated with GM-CSF placebo (P = .261); the median OS was 72.4 months versus 37.3 months, respectively (P < .001; Data Supplement).

For the comparison between PV and placebo in HLA-A2–positive patients, the effect observed in this unplanned analysis showed a different trend: there was no difference in RFS or OS for patients with stage IIIA or IIIB disease (data not shown), but patients with stage IIIC/M1a disease who received PV versus placebo had better RFS (median, 15.2 v 9.7 months; P = .040) and OS (median, 91.1 v 39.1 months; P = .128). Among patients with stage M1b or M1c disease, however, PV versus placebo was associated with worse RFS (median, 5.5 v 20.9 months; P = .018) and OS (median, 32.8 v 72.4 months; P = .288; Data Supplement).

AEs

AEs were reported for 782 patients who received at least one dose of protocol therapy. Overall, the incidence of treatment-related grade 3 or higher AEs was similar in patients who received GM-CSF (12.3%) and those who did not (9.9%; P = .306) and in those who received PV (13.6%) and those who did not (11.4%; Table 3). Overall, the most common grade 3 or higher AEs were injection-site reactions (17 [ 2.2%] of 782) and headache (16 [2.0%] of 782; Data Supplement). A total of four grade 5 AEs (ie, deaths) occurred during treatment on the study, none of which was considered related to protocol treatment (Data Supplement).

Table 3.

Comparison of Incidence of Grade 3 or Higher Adverse Events in Treated Patients

| Group | Treatment-Related AEs |

All AEs |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Patients | No. of Grade ≥ 3 AEs | Incidence, % (95% CI) | P* | No. of Grade ≥ 3 AEs | Incidence, % (95% CI) | P* | |

| GM-CSF | .306 | .064 | |||||

| No | 385 | 38 | 9.9 (7.1 to 13.3) | 79 | 20.5 (16.6 to 24.9) | ||

| Yes | 397 | 49 | 12.3 (9.3 to 16.0) | 104 | 26.2 (21.9 to 30.8) | ||

| PV | .558 | .827 | |||||

| No | 211 | 24 | 11.4 (7.4 to 16.4) | 55 | 26.1 (20.3 to 32.5) | ||

| Yes | 214 | 29 | 13.6 (9.3 to 18.9) | 58 | 27.1 (21.3 to 33.6) | ||

| Treatment arm | .452 | .633 | |||||

| HLA-A2 positive | |||||||

| A | 104 | 12 | 11.5 (6.1 to 19.3) | 30 | 28.8 (20.4 to 38.6) | ||

| B | 110 | 17 | 15.4 (9.3 to 23.6) | 25 | 22.7 (15.3 to 31.7) | ||

| C | 107 | 15 | 14.0 (8.1 to 22.1) | 23 | 21.5 (14.1 to 30.5) | ||

| D | 104 | 9 | 8.6 (4.0 to 15.8) | 25 | 24.0 (16.2 to 33.4) | ||

| HLA-A2 negative | .149 | .022 | |||||

| E | 186 | 22 | 11.8 (7.6 to 17.4) | 51 | 27.4 (21.1 to 34.4) | ||

| F | 171 | 12 | 7.0 (3.7 to 11.9) | 29 | 17.0 (11.7 to 23.4) | ||

NOTE. Arms: A, GM-CSF plus PV; B, GM-CSF placebo plus PV; C, GM-CSF plus PV placebo; D, GM-CSF placebo and PV placebo; E, GM-CSF; F, GM-CSF placebo.

Abbreviations: AE, adverse event; GM-CSF, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor; HLA, human leukocyte antigen; PV, peptide vaccination.

Fisher's exact test was used for all comparisons. P > .05 for pairwise comparisons between arms A, B, C, and arm D (reference group) in HLA-A2–positive patients.

Second Malignancies

Seventy-three patients developed a second primary cancer during the study period. Fifty-five patients had one second primary cancer, and 18 had multiple new cancers, which resulted in a total of 118 new cancer events. Most second primary cancers were melanoma (n = 12) and nonmelanoma (n = 58) skin cancers (Data Supplement). There were no instances of myeloid leukemia, but one patient developed acute lymphocytic leukemia.

DISCUSSION

This is the first randomized trial of adjuvant GM-CSF in patients with resected, stage III and IV melanoma. The median OS was 10.3 months longer (69.6 v 59.3 months, representing a 17.4% improvement) in patients who received GM-CSF than in patients who received GM-CSF placebo; this result was less than the hypothesized increase in OS (absolute increase, 13.3 months; relative improvement, 33%) sought in the trial. The RFS times were 11.4 months for GM-CSF versus 8.8 months for placebo. These results are not statistically significant but leave open the question of whether GM-CSF may have smaller benefits. Other possible contributors to this lack of significant benefit include lack of efficacy, pre-existing immune status of patients, immunologic response to GM-CSF, development of neutralizing antibodies to GM-CSF, effects of GM-CSF on suppressor elements (such as myeloid-derived suppressor cells), and possible suboptimal dose and/or duration of treatment.6,7,9 The greater effect on OS than on RFS seen in other studies6–8 was not seen in this study.

In HLA-A2–positive patients, the median RFS was 1.7 months longer in patients who received PV versus PV placebo (11.5 v 9.8 months; 17.3% improvement), which was less than the expected improvement (3 months; 33% improvement) and not statistically significant. Possible reasons for this include baseline immune status of the patients, limited response of patients to PV, lack of relevance of any immune response to PV, adjuvant selection, and vaccine administration issues.

Among HLA-A2–positive patients, the median OS and RFS were longer in patients receiving both GM-CSF and PV than in patients in the other three arms, but the differences were not significant. The study does not support the hypothesis that systemically administered GM-CSF enhances the efficacy of PV, as administered in this trial. This is consistent with the findings from trial E1696 conducted in patients with active disease.13

Analysis of results by prespecified stratification factors suggested differential effects of both GM-CSF and PV according to the sites of metastases (visceral v nonvisceral). These results are hypothesis generating and may be explained by differences in immune status of patients with visceral metastases that persist past resection, effect of resection itself, and possible differential effects of immunomodulatory agents on visceral-versus-nonvisceral tumor microenvironments that contribute to the prevention of additional growth of unrecognized micrometastases.

There was no difference in the natural history of HLA-A2–positive and –negative patients, nor in treatment effect of GM-CSF between the two HLA types. Others, however, found that patients with the HLA-Cw*06 allele had better RFS and OS after IFN treatment than those with other alleles,16 and data suggest an effect of HLA-A2 status on the benefit of adjuvant IFN.17 Thus, there may be interactions between HLA type and response to other immunotherapeutic agents, or interactions with other HLA types and GM-CSF.

Safety data analysis confirms that GM-CSF and PV are well tolerated and safe. The most common AEs were injection-site reactions and headache.

Although, overall, this study did not support the hypothesis that adjuvant GM-CSF could make a significant impact on RFS or OS of the study population, trials that test GM-CSF in patients with resected visceral melanoma metastases are worthy of consideration. Such studies may target a patient population unable, unlikely, or unwilling to tolerate current immunotherapeutic adjuvant agents (eg, IFN, cytotoxic T-cell lymphocyte-4 blockade) on the basis of a borderline performance status or other comorbid conditions, such as symptomatic lung disease, inflammatory bowel disease, or significant autoimmune diseases.

GM-CSF may find its greatest use in melanoma in combination with other agents. Recent data strongly suggest that the addition of GM-CSF at the dose used in our study to ipilimumab 10 mg/kg, with maintenance dosing (higher dose and longer treatment than that approved for metastatic melanoma), may improve both efficacy and safety in patients with metastatic disease. This suggestion led to an ongoing trial (EA6141) that will definitively test this hypothesis.18 If successful, this regimen may be tested in the adjuvant setting.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We thank the participants in this clinical trial, the study nurses and research coordinators, and the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) clinical trial personnel. We especially thank Carol Hill, RN, BSN, the protocol nurse for this trial, and Anthea Hammond, PhD, for her excellent writing skills.

Support information appears at the end of this article.

Content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Cancer Institute.

Authors' disclosures of potential conflicts of interest are found in the article online at www.jco.org. Author contributions are found at the end of this article.

Clinical trial information: NCT01989572.

Support

Supported in part by Public Health Service Grants No. CA180802, CA180794, CA180864, CA180844, CA180854, CA18082, CA32102, CA180888, CA20319, CA31946, and CA04326 (for coordination by the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group–American College of Radiology Imaging Network Cancer Research Group, Robert L. Comis, MD, and Mitchell D. Schnall, MD, PhD, group co-chairs); by National Institutes of Health Grant No. P30CA047904 (through use of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Central Immunology Laboratory [Frontier Science and Technology Research Foundation] at the University of Pittsburgh Cancer Institute Immunological Monitoring and Cellular Products Laboratory for this and correlative studies); and by the National Cancer Institute, the National Institutes of Health, and the Department of Health and Human Services.

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Disclosures provided by the authors are available with this article at www.jco.org.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: David H. Lawson, Sandra Lee, Michael B. Atkins, Gary I. Cohen, John M. Kirkwood

Provision of study materials or patients: Ahmad A. Tarhini, Kim A. Margolin, Gary I. Cohen

Collection and assembly of data: David H. Lawson, Ahmad A. Tarhini, Kim A. Margolin, Marc S. Ernstoff, Lisa H. Butterfield

Data analysis and interpretation: David H. Lawson, Sandra Lee, Fengmin Zhao, Ahmad A. Tarhini, Kim A. Margolin, Marc S. Ernstoff, Michael B. Atkins, Theresa L. Whiteside, Lisa H. Butterfield, John M. Kirkwood

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Randomized, Placebo-Controlled, Phase III Trial of Yeast-Derived Granulocyte-Macrophage Colony-Stimulating Factor (GM-CSF) Versus Peptide Vaccination Versus GM-CSF Plus Peptide Vaccination Versus Placebo in Patients With No Evidence of Disease After Complete Surgical Resection of Locally Advanced and/or Stage IV Melanoma: A Trial of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group–American College of Radiology Imaging Network Cancer Research Group (E4697)

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or jco.ascopubs.org/site/ifc.

David H. Lawson

Honoraria: Bristol-Myers Squibb, Genentech

Research Funding: Bristol-Myers Squibb, GlaxoSmithKline, Amgen, Prometheus Laboratories, Merck

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Genentech

Sandra Lee

Employment: Conkwest (I)

Leadership: Conkwest, Osiris Therapeutics (I)

Stock or Other Ownership: Conkwest (I)

Consulting or Advisory Role: Roche

Speakers' Bureau: Dava Oncology (I)

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Dava Oncology (I)

Fengmin Zhao

No relationship to disclose

Ahmad A. Tarhini

Consulting or Advisory Role: Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Genentech, Amgen, Castle Biosciences

Research Funding: Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Amgen, Novartis, Pfizer

Kim A. Margolin

Consulting or Advisory Role: OncoSec Medical, Amgen

Marc S. Ernstoff

Stock or Other Ownership: Bristol-Myers Squibb, Abbott Laboratories

Honoraria: Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck, Alkermes

Consulting or Advisory Role: Veterans Administration, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck, Alkermes

Research Funding: Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck, Alkermes, Altor Bioscience, Polynoma (Inst)

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck

Michael B. Atkins

Honoraria: Bristol-Myers Squibb

Consulting or Advisory Role: Merck, Genentech, Pfizer, Novartis, GlaxoSmithKline, cCam Biotherapeutics, X4 Pharma, Neostem, Amgen, Eli Lilly, Alkermes, Infinity Pharmaceuticals

Gary I. Cohen

Stock or Other Ownership: Nymox, Pharmacyclics, Celgene, Foundation Medicine

Consulting or Advisory Role: Eviti

Research Funding: Amgen (Inst), Genentech (Inst), Celgene (Inst), Infinity Pharmaceuticals (Inst)

Theresa L. Whiteside

No relationship to disclose

Lisa H. Butterfield

Stock or Other Ownership: Kite Pharma

Honoraria: Astellas Pharma

Consulting or Advisory Role: Neostem, DIAN, Pron Somitomo

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: US Patent 7,098,306

John M. Kirkwood

Consulting or Advisory Role: Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck, GlaxoSmithKline, GreenPeptide

Research Funding: Prometheus Laboratories (Inst)

REFERENCES

- 1.Lawson D, Kirkwood JM. Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor: Another cytokine with adjuvant therapeutic benefit in melanoma? J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:1603–1605. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.8.1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wing EJ, Magee DM, Whiteside TL, et al. Recombinant human granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor enhances monocyte cytotoxicity and secretion of tumor necrosis factor alpha and interferon in cancer patients. Blood. 1989;73:643–646. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grabstein KH, Urdal DL, Tushinski RJ, et al. Induction of macrophage tumoricidal activity by granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor. Science. 1986;232:506–508. doi: 10.1126/science.3083507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bell D, Young JW, Banchereau J. Advances in immunology. Adv Immunology. 1999;72:255–324. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60023-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dong Z, Kumar R, Yang X, et al. Macrophage-derived metalloelastase is responsible for the generation of angiostatin in Lewis lung carcinoma. Cell. 1997;88:801–810. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81926-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spitler LE, Grossbard ML, Ernstoff MS, et al. Adjuvant therapy of stage III and IV malignant melanoma using granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:1614–1621. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.8.1614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spitler LE, Weber RW, Allen RE, et al. Recombinant human granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF, sargramostim) administered for 3 years as adjuvant therapy of stages II(T4), III, and IV melanoma. J Immunother. 2009;32:632–637. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e3181a7d60d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grotz TE, Kottschade L, Pavey ES, et al. Adjuvant GM-CSF improves survival in high-risk stage IIIC melanoma: A single-center study. Am J Clin Oncol. 2014;37:467–472. doi: 10.1097/COC.0b013e31827def82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Daud AI, Mirza N, Lenox B, et al. Phenotypic and functional analysis of dendritic cells and clinical outcome in patients with high-risk melanoma treated with adjuvant granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3235–3241. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.9048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Astsaturov I, Petrella T, Bagriacik EU, et al. Amplification of virus-induced antimelanoma T-cell reactivity by high-dose interferon-alpha2b: Implications for cancer vaccines. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:4347–4355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chianese-Bullock KA, Pressley J, Garbee C, et al. MAGE-A1-, MAGE-A10-, and gp100-derived peptides are immunogenic when combined with granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor and Montanide ISA-51 adjuvant and administered as part of a multipeptide vaccine for melanoma. J Immunol. 2005;174:3080–3086. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.5.3080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rosenberg SA, Yang JC, Schwartzentruber DJ, et al. Immunologic and therapeutic evaluation of a synthetic peptide vaccine for the treatment of patients with metastatic melanoma. Nat Med. 1998;4:321–327. doi: 10.1038/nm0398-321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kirkwood JM, Lee S, Moschos SJ, et al. Immunogenicity and antitumor effects of vaccination with peptide vaccine+/-granulocyte-monocyte colony-stimulating factor and/or IFN-alpha2b in advanced metastatic melanoma: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group phase II trial E1696. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:1443–1451. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Flaherty LE, Othus M, Atkins MB, et al. Southwest Oncology Group S0008: A phase III trial of high-dose interferon alfa-2b versus cisplatin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine, plus interleukin-2 and interferon in patients with high-risk melanoma-an intergroup study of Cancer and Leukemia Group B, Children's Oncology Group, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group, and Southwest Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:3771–3778. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.53.1590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lawson DH, Lee SJ, Tarhini AA, et al. E4697: Phase III cooperative group study of yeast-derived granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) versus placebo as adjuvant treatment of patients with completely resected stage III-IV melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:612s. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.62.0500. (abstr 8504) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gogas H, Kirkwood JM, Falk CS, et al. Correlation of molecular human leukocyte antigen typing and outcome in high-risk melanoma patients receiving adjuvant interferon. Cancer. 2010;116:4326–4333. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kirkwood JM, Richards T, Zarour HM, et al. Immunomodulatory effects of high-dose and low-dose interferon alpha-2b in patients with high-risk resected melanoma: The E2690 laboratory corollary of intergroup adjuvant trial E1690. Cancer. 2002;95:1101–1112. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hodi FS, Lee S, McDermott DF, et al. Ipilimumab plus sargramostim vs ipilimumab alone for treatment of metastatic melanoma: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;312:1744–1753. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.13943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.