Abstract

Background

Wnt signaling pathways are highly conserved signal transduction pathways important for axis formation, cell fate specification, and organogenesis throughout metazoan development. Within the various Wnt pathways, the frizzled transmembrane receptors (Fzs) and secreted frizzled-related proteins (sFRPs) play central roles in receiving and antagonizing Wnt signals, respectively. Despite their importance, very little is known about the frizzled-related gene family (fzs & sfrps) in lophotrochozoans, especially during early stages of spiralian development. Here we ascertain the frizzled-related gene complement in six lophotrochozoan species, and determine their spatial and temporal expression pattern during early embryogenesis and larval stages of the marine annelid Platynereis dumerilii.

Results

Phylogenetic analyses confirm conserved homologs for four frizzled receptors (Fz1/2/7, Fz4, Fz5/8, Fz9/10) and sFRP1/2/5 in five of six lophotrochozoan species. The sfrp3/4 gene is conserved in one, divergent in two, and evidently lost in three lophotrochozoan species. Three novel fz-related genes (fzCRD1-3) are unique to Platynereis. Transcriptional profiling and in situ hybridization identified high maternal expression of fz1/2/7, expression of fz9/10 and fz1/2/7 within animal and dorsal cell lineages after the 32-cell stage, localization of fz5/8, sfrp1/2/5, and fzCRD-1 to animal-pole cell lineages after the 80-cell stage, and no expression for fz4, sfrp3/4, and fzCRD-2, and -3 in early Platynereis embryos. In later larval stages, all frizzled-related genes are expressed in distinct patterns preferentially in the anterior hemisphere and less in the developing trunk.

Conclusions

Lophotrochozoans have retained a generally conserved ancestral bilaterian frizzled-related gene complement (four Fzs and two sFRPs). Maternal expression of fz1/2/7, and animal lineage-specific expression of fz5/8 and sfrp1/2/5 in early embryos of Platynereis suggest evolutionary conserved roles of these genes to perform Wnt pathway functions during early cleavage stages, and the early establishment of a Wnt inhibitory center at the animal pole, respectively. Numerous frizzled receptor-expressing cells and embryonic territories were identified that might indicate competence to receive Wnt signals during annelid development. An anterior bias for frizzled-related gene expression in embryos and larvae might point to a polarity of Wnt patterning systems along the anterior–posterior axis of this annelid.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s13227-015-0032-4) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Frizzled, sFRP, wnt, Beta-catenin, Spiral cleaving, Signaling center, Cell lineage, Lophotrochozoan, Annelid, Polychaete, Asymmetric cell division, Evolution, Phylogeny

Background

Wnt signaling pathways are highly conserved signal transduction pathways that have widespread functions during development in all metazoans including essential roles in cell fate specification, cell proliferation, and embryonic axis formation [1–3]. Three main Wnt pathways have been identified. The Wnt/Ca2+ pathway regulates intracellular Ca2+ levels [4, 5], the Planar Cell Polarity (PCP) pathway polarizes cells within an epithelial sheet [6], and the canonical Wnt or Wnt/beta-catenin pathway elicits the transcription of target genes. Canonical Wnt/beta-catenin signaling is the most studied of the three Wnt pathways. Central to this pathway is the regulation of beta-catenin stability. Upon pathway activation, degradation of beta-catenin is inhibited and cytoplasmic and nuclear levels of beta-catenin protein rise. High levels of nuclear beta-catenin promote the formation of transcriptional activators, elicit new gene expression, and lead to subsequent specification of cell fates [1, 7–9].

Central to each of the three Wnt pathways are members of the frizzled family of transmembrane receptors and secreted proteins [10–12]. Frizzled receptors, first identified in Drosophila melanogaster as factors involved in planar cell polarity [13], are 7-pass transmembrane receptors with an extracellular cysteine-rich domain (CRD) that binds secreted Wnt ligands. This Wnt ligand-frizzled receptor interaction activates the Wnt pathway by transmitting the signal via structural changes to the receptor’s cytoplasmic domain. In the canonical Wnt pathway, this structural change facilitates the association with and inhibition of a beta-catenin destruction complex, and subsequently leads to nuclear accumulation of beta-catenin [1]. In addition to frizzled receptors, a second class of frizzled family genes, the secreted frizzled-related proteins (sFRP), have been identified as modifiers of Wnt signaling. These sFRPs consist of an N-terminal CRD that is evolutionarily related to the CRD of frizzled receptors, and a C-terminal Netrin domain [14, 15]. sFRPs are thought to inhibit Wnt signaling by competitively binding Wnt ligands [16].

Previous phylogenomic analyses have suggested that the last common ancestor of eumetazoans, a clade that includes cnidarians and bilaterians, had a frizzled-related gene complement consisting of four frizzled receptors and two sFRPs [2, 17, 18]. This ancestral frizzled-related gene set of six expanded and retracted during vertebrate evolution due to two rounds of whole genome duplication followed by gene loss early in the vertebrate lineage [10, 19, 20]. Today, most vertebrates outside the teleost fish possess ten frizzled receptors and four sFRPs (five in mammals) [10, 21, 22]. These receptors have been numbered Fz1–Fz10, and the sFRPs have been numbered sFRP1–sFRP5. The origin of each can be traced back to one of the ancestral frizzled genes, which have been named fz1/2/7, fz4, fz5/8, fz9/10, sfrp1/2/5, and sfrp3/4. The two closely related fz3 and fz6 genes are restricted to vertebrates and are of uncertain evolutionary origin, although some phylogenetic analyses position them close to or within the fz1/2/7 gene family [17, 18]. Previous studies have determined that sfrp1/2/5 and sfrp3/4 are not closely related, and did not originate from one ancestral sfrp 1/2/3/4/5 gene. Despite having a similar domain structure, a CRD domain linked to a Netrin (NTR) domain, there is strong evidence that both genes likely originated by two independent but similar gene duplication events that generated a fusion of a frizzled-related CRD domain with a NTR domain [17].

While frizzled-related genes are well studied in vertebrates including mammals, several investigations over the last decade began to examine frizzled-related genes in a wider range of invertebrate species during early development [23–28]. These studies have mainly focused on fz1/2/7,fz5/8, and sfrp1/2/5, and revealed similar embryonic expression domains for orthologous genes suggesting evolutionary conserved roles [29–34]. Although functional evidence in invertebrate embryos is scarce, the observation of anterior expression domains of the Wnt antagonist sfrp1/2/5 in many invertebrate embryos supports an evolutionary conserved role of sfrp1/2/5 in the establishment of an anterior Wnt inhibitory center in metazoan embryos [3, 35].

To further investigate the presence and expression of the frizzled-related gene complement in invertebrate species, we focused on lophotrochozoan species, especially the annelid Platynereis dumerilii. Lophotrochozoans constitute one of the three major branches of bilaterians and include invertebrate groups like annelids, mollusks, nemerteans, flatworms, and numerous enigmatic smaller invertebrate phyla like brachiopods and bryozoans [36–40]. Several of these phyla exhibit a common mode of early embryogenesis called spiral cleavage, a series of invariant and stereotypic asymmetric cell divisions that generate a spiral arrangement of embryonic cells of distinct size and position along the animal-vegetal axis of the embryo. These phyla have also been traditionally grouped as ‘Spiralia.’ Intriguingly, some recent metazoan phylogenetic studies imply that ‘spiral cleavage’ might even be an ancestral condition making the clade ‘Spiralia’ synonymous with ‘Lophotrochozoa’ [41], while a more recent analysis by Laumer and colleagues suggests that the lophotrochozoans are a subgroup of the spiralians [38].

Our lophotrochozoan of choice, the annelid Platynereis dumerilii, exhibits a typical mode of unequal spiral cleavage during early embryogenesis (Fig. 1) [42–44]. The first two cell divisions are highly unequal giving rise to four large embryonic cells of different sizes, the two smaller A and B cells, one larger C cell, and the largest D cell (Fig. 1B, 4-cell stage). These founder cells or quadrants are ordered alphabetically in a clockwise direction when viewed from the animal pole marked by a pair of polar bodies. The next cell division of each founder cell is oriented along the animal-vegetal axis giving rise to smaller animal-pole daughter cells, the first micromeres 1a, 1b, 1c, and 1d and the larger vegetal-pole daughter cells, the macromeres 1A, 1B, 1C, and 1D forming the 8-cell stage. Each micromere is shifted clockwise with respect to its sister macromere. During the next cell division, the four first micromeres in each quadrant 1a, 1b, 1c, and 1d (1q) divide along the animal-vegetal axis tilted counterclockwise giving rise to a larger animal-pole daughter cell named 1q1 and a smaller vegetal-pole daughter cell 1q2, with the 1q1 cells shifted counterclockwise with respect to the more vegetally localized 1q2 sister cells (Fig. 1B, 16-cell stage). The four macromeres 1A, 1B, 1C, and 1D (1M) divide similarly along the animal-vegetal axis forming the animal-pole daughter cells 2a, 2b, 2c, and 2d (2q) shifted counterclockwise in relation to their vegetal-pole daughter cells 2A, 2B, 2C, and 2D (2M). This pattern of cleavage continues with alternating clockwise and counterclockwise shifts leading to a spiral arrangement of cells when viewed from the animal pole.

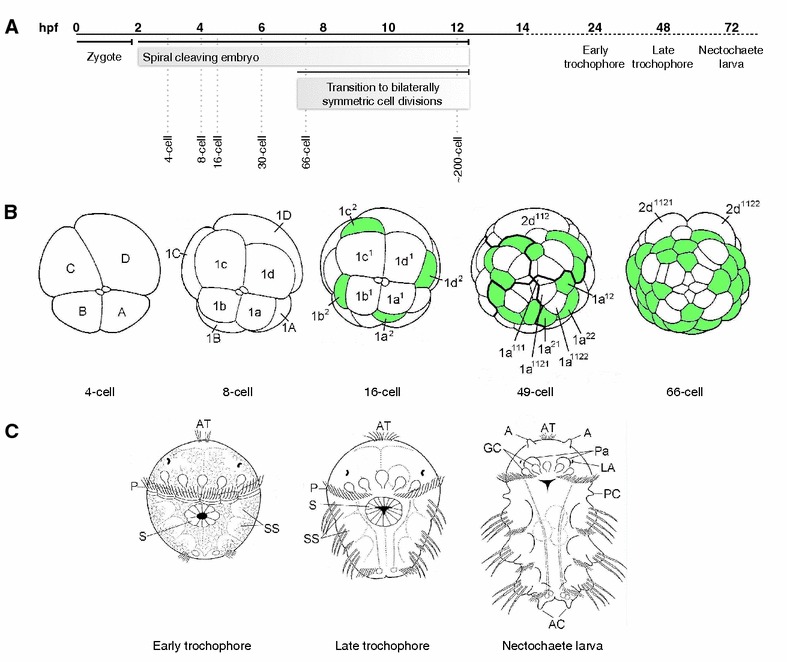

Fig. 1.

Development stages of Platynereis dumerilii. A Temporal development of Platynereis beginning with fertilization (0 hpf), spiral cleavage stages (2 to 12 hpf), early and late trochophore (24 and 48 hpf), and nectochaete (72 hpf) larval stages. The first cell division begins shortly after 2 hpf, followed by a period of spiral cleavages, and then a transition to a bilaterally symmetrical pattern of cell divisions after 7 hpf. B Unequal spiral cleavage pattern of Platynereis embryos. Schematics depict animal-pole views of spiral cleavage stages. The two small circles in the center of the 4- to 16-cell stages represent the two polar bodies. The 4-cell stage shows the unequal size and nomenclature of the four quadrants/founder cells (A–D). The 8-cell stage shows the animal-pole 1st micromeres (1a, 1b, 1c, and 1d; or 1q) and their vegetal-pole daughter cells (1A, 1B, 1C, and 1D; or 1M). The 16-cell stage depicts the daughter cell pairs of the first micromeres (1q 1 and 1q 2). The 49-cell stage indicates the cell progeny contributed from each quadrant (dark lines) and highlights the cleavage pattern of the progeny of the first micromeres indicating the nomenclature for the 1a progeny, the first micromere of the A quadrant. Each of the four quadrants generates one small rosette cell (1q 111) and a larger daughter cell (1q 112) whose progeny will form the anterior head region. These cells form the ‘annelid cross’ (white) and are surrounded by cells (green) that will form the ciliated ring/prototroch of the larvae. The 66-cell stage highlights the first bilaterally symmetrical cleavage in the 2d cell lineage giving rise to 2d1121 and 2d1122 cells whose progeny will form the trunk ectoderm. C Schematics of three larval stages, the early (24 hpf) and late (48 hpf) trochophore, and the mid nectochaete (72 hpf), ventral views with anterior to the top. The prototroch is a ciliated ring of cells located between the anterior head region/episphere and the posterior trunk region/hyposphere. The episphere harbors the apical organ, eyes, and brain. The trunk region contains the three larval segments including the chaetal sacs. The pygidium includes the posterior growth zone where new segments are added. The stomodeum is located on the ventral side adjacent to the prototroch. Chaetal sacs are three segmental pairs of primordia that give rise to appendages, the parapodia. By the nectochaete stage, parapodia are well established and the head region becomes distinct. Abbreviations: A antenna, AC anal cirri, AT apical tuft, GC larval gland cells, LA larval eyes, P prototroch, Pa palps, PC peristomial cirrus, S stomodeum, SS setal (chaetal) sacs. Schematics are modified from Fischer and Dorresteijn 2004 [43] and Pruitt et al. 2014 [54]

By the ~49-cell stage (Fig. 1B), the progeny of the four 1q11 cells in each of the four quadrants has generated four small characteristic animal-pole daughter cells, the rosette cells (1q111), at the animal pole, and four larger vegetal-pole sister cells (1q112), the dorsal and ventral cephaloblasts. The cephaloblasts have divided once more to generate 1q1121 and 1q1122 sister cell pairs (white cells) in each quadrant that form the ‘annelid cross’ surrounded by cells (green) that will form a ciliated ring, the prototroch. The rosette cells will later contribute to the apical organ, and the cephaloblasts will form most of the head region including eyes and brain of the annelid trochophore larvae [42, 44].

Of special significance is the larger D quadrant in Platynereis embryos that will generate two extremely large founder cells, the 2d112, a progeny of the 2nd ‘micromere’ 2d, and the 4th ‘micromere’ 4d, the mesentoblast, that will give rise to the trunk ectoderm and mesoderm, respectively. These large founders cells are the first to switch from spiral cleavage to a mode of cleavage that generates a bilateral symmetrical arrangement of progeny [42, 44–46].

By 24-h post fertilization (hpf), Platynereis has developed into an early trochophore larvae (Fig. 1C), with the prototroch fully formed separating the anterior head or episphere from the posterior trunk region or hyposphere [43, 44, 47]. The prototroch is used for locomotion and comprises a ring of multiciliated cells circumnavigating the embryo. It persists throughout the trochophore stages but begins to disappear by the nectochaete stage (~3-day-old larvae). In the head region of the trochophore larva, the ciliated apical organ, brain, and other anterior structures have formed from the progeny of the rosette cells (1q111) and their sister cells, the 1q112 cells. The stomodeum anlage, the future mouth, becomes visible on the ventral side of the early trochophore larva adjacent to the prototroch. Posterior to the anus in the hyposphere, the pygidium has formed. By late trochophore stage (~48 hpf), the three trunk segments are visible, each containing a pair of primordia, the chaetal sacs, which will give rise to the bristle (chaetae) bearing parapodia, the appendages of the annelid. On either side of the ventral midline, bilaterally symmetric ciliated structures called paratrochs begin to form posterior to each segment. After 3 days of development, a distinctive head region begins to emerge and becomes increasingly separate from the trunk. At this nectochaete larval stage, the segmental appendages/parapodia including elongated chaetae are fully formed and take over functions in locomotion [43, 47].

Previous work indicated that canonical Wnt/beta-catenin signaling is essential in early Platynereis development [48]. During the transition from the 4-cell to the 8-cell stage, strong nuclear localization of beta-catenin protein can be observed in the four vegetal-pole macromeres (1 M), while the four animal-pole micromeres (1q) are lacking any nuclear beta-Catenin. This suggests that the Wnt/beta-catenin pathway is activated in the macromeres. During most subsequent cell divisions through the ~220-cell stage, the asymmetric localization pattern of beta-catenin is repeated, suggesting that every vegetal-pole daughter cell exhibits activated canonical Wnt signaling, whereas the animal-pole daughter cells do not. Indeed, this asymmetric beta-catenin activation acts as a binary cell fate switch. Inhibition of the beta-catenin degradation complex with the drug 1-Azakenpaullone leads to global beta-catenin nuclear localization, and to animal-pole daughter cells adopting the cell fate of their vegetal-pole daughter cells [48]. Similar beta-catenin-mediated binary switches have now been found in all three major branches of bilateral symmetrical animals, although restricted to nematode, ascidian, and annelid embryos with fixed stereotypic, invariant cell lineages [49–52]. However, the molecular mechanism causing this asymmetric pattern in early Platynereis embryos remains unknown. While the full complement of Wnt ligands has been surveyed comprehensively in both early and late Platynereis development [53, 54], it is not yet known whether and which frizzled receptors might be involved. As expression and function of the larger frizzled-related gene family are largely unexplored in any lophotrochozoan species, especially during early spiral embryogenesis, we decided to investigate the frizzled-related gene family in embryos and larvae of Platynereis.

Here we present the first comprehensive look at the frizzled-related gene family in lophotrochozoans, and determine the frizzled-related gene complement in six lophotrochozoan species. Using an RNA-seq time course spanning the first 14 h of Platynereis development, we have identified nine frizzled-related genes in this annelid species and have quantified their stage-specific expression. Analyses of structural features and phylogeny identified well-conserved orthologous genes for four Frizzled receptors, fz1/2/7, fz5/8, fz9/10, and fz4 and one conserved sFRP, sfrp1/2/5, two derived sfrp3/4-like genes, and two novel frizzled-related genes with similarities to sFRPs. Using whole-mount in situ hybridization, we have determined the spatial expression patterns of seven frizzled-related genes in early embryos and larval stages. This comprehensive study of frizzled expression in Platynereis embryos and larvae suggests numerous Wnt signaling inputs into annelid development, and indicates evolutionary conserved functions for fz1/2/7, fz5/8, and sfrp1/2/5 in patterning early embryos. Furthermore, the presented work provides the critical information necessary for a functional dissection of Wnt signaling in this species.

Methods

Platynereis dumerilii culture

Platynereis embryos and larvae were obtained from a breeding culture at Iowa State University maintained according to protocols available at http://www.platynereis.de [43, 54]. Newly fertilized eggs were placed in an 18 °C incubator to ensure constant temperature throughout early development.

Transcriptome assembly

After incubation at 18 °C, embryos were collected at 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, and 14 hpf with biological replicates, homogenized in Trizol (Ambion), and stored at −80 °C before RNA was extracted according to manufacturer’s protocol. RNA was treated with RNase-free DNase Set (QIAGEN) prior to purification with RNeasy Mini Kit (QIAGEN). Deep sequencing with 75 bp-100 bp paired-end reads was performed at Duke Institute for Genome Sciences and Policy using an Illumina HiSeq sequencing system. Reads were filtered with Trimmomatic [55] and assembled de novo using the Trinity method [56]. Expression levels were calculated in FPKM (fragments per kilobase per million mapped reads) using the RSEM software package [57]. To compare the expression level across samples, we used a scaling normalization method called TMM (trimmed mean of M values) [58] to get the TMM-normalized FPKM.

Alignment and phylogenetic analysis

P. dumerilii sequences were derived from RNA-seq data and verified by cloning and Sanger sequencing. Sequences from other species were obtained from NCBI and JGI databases (see Additional file 1: Table S1; Additional file 2: Table S2). Representative species were chosen from each of the major phylogenetic groups including chordates (H. sapiens, X. laevis, D. rerio, B. floridae), echinoderms (S. purpuratus), hemichordates (S. kowalevskii), ecdysozoans (D. melanogaster, C. elegans, T. castaneum, D. pulex), lophotrochozoans (P. dumerilii, C. gigas, C. teleta, A. californica, H. robusta, L. gigantea), and a nonbilaterian (N. vectensis). Frizzled family genes were identified by reciprocal BLAST using well-annotated queries from H. sapiens. Conserved domains were identified using NCBI Batch Web-CD Search Tool. Sequences of conserved domains were aligned with Mafft [59] using the Mafft iterative approach (L-INS-i) for maximum speed and accuracy [60]. Multiple alignments were visualized and manually edited in Aliview [61]. Positions that consisted of 70 % or more gaps were removed. Phylogenetic analysis was performed using Mr. Bayes [62] with the InvGamma model of substitution rates. Analysis ran for 2,000,000 generations with a 500,000 generation burn in. Smoothened sequences were used as an outgroup for CRD tree, and TIMP sequences were used as an outgroup for the NTR tree. Trees were visualized in FigTree (http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree/) and modified for publication in Adobe Illustrator. Highly divergent species and sequences were removed before final CRD analysis (see Additional file 1: Table S1).

Cloning of Frizzled family genes

Sequences for Frizzled receptors and sFRPs were obtained from the assembled transcriptome, and primers were designed using Primer3 [63]. Primers used were as follows: fz1/2/7 full ORF clone, forward: GCATGTCTTGATTGGAGTCG, reverse: TTGATGAGTGATGATTTGTCAAC; fz4 full ORF clone, forward: CTTTGCACCTCAGTGACACA, reverse: AACGAGGGCCATAAATCTTG: fz5/8 full ORF clone, forward: CTCCAGCCCCTATTTCAACA, reverse: GTCTTCCCTGACCAGATCCA; fz5/8 partial clone, forward: CTCCAGCCCCTATTTCAACA, reverse: GTCTTCCCTGACCAGATCCA; fz9/10 partial clone, forward: TGTCCTCAGCTGTGACAACC, reverse: GTTTCTCGAACTTGCGAAGG: sfrp1/2/5 full ORF clone, forward: TTGTGAAAGGTGACTGTTAAACG, reverse: CATTAGTCCATTGAGATTACTTTTCG; sfrp1/2/5 partial clone, forward: TACCAACCGAAGTGTGTGGA, reverse: TTGTCTCCCTTCCTGTTTCG; sfrp3/4 full ORF clone, forward: TTGCTGCTGCTATGTGAAGG, reverse: GCTGATGGAGCTTCTTTCCA; and fzCRD-1 full ORF clone, forward: TCCAAAATGAAGAGCCTTGTG, reverse: GCAGCCTCCAAAGGTAAGG. Target sequences were PCR amplified using Standard Taq Polymerase (New England Biolabs) and ligated into pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega), except for fz4 and sfrp3/4 which were amplified using OneTaq (New England Biolabs) and ligated into PCR II Dual Promoter vector (Invitrogen). Plasmid DNA was isolated using Plasmid Mini Kit (Qiagen), and sequences were verified by Sanger sequencing with T7 and Sp6 primers. Sequences for P. dumerilii frizzled1/2/7, frizzled4, frizzled5/8, frizzled9/10, sfrp1/2/5, sfrp3/4, and fzCRD-1 were deposited in GenBank with accession numbers KT989648-KT989654.

Whole-mount in situ hybridization

Templates for probe synthesis were generated from plasmid DNA linearized with an appropriate restriction enzyme to result in a probe of ~1000 nucleotides. Antisense RNA probes were synthesized using Sp6 (Roche) or T7 (New England Biolabs) RNA polymerase kits and DIG RNA labeling mix (Roche). Embryos >18 hpf were fixed in a solution of 4 % paraformaldehyde 0.1 M MOPS free acid, 2 mM EGTA, 1 mM MgSO4, and 0.1 %Tween-20 for at least 4 h on a nutator at 4 °C. Embryos <18 hpf were treated in a solution of 50 mM Tris, 495 mM NaCl, 9.6 mM KCl, 27.6 mM Na2SO4, 2.3 mM NaHCO3, and 6.4 mM EDTA at pH 8.0 two times for 3 min prior to fixation to remove the vitelline membrane [48]. Embryos were then fixed overnight on a nutator at 4 °C. Whole-mount in situ hybridization was performed according to previously published protocols [64] with previously described modifications [54]. Embryos were stored at 4 °C in PBT for up to 2 weeks to reduce background before staining with DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; Sigma). Embryos were mounted in 87 % glycerol and stored at 4 °C. Embryos <16 hpf were imaged on a LSM700 Microscope with an AxioCam MRc5. Older embryos and larvae were imaged with a Zeiss Axioskop 2 microscope with a Canon EOS Rebel T3 camera. Images were adjusted in Adobe Photoshop for brightness and contrast. False color images were generated by first modifying DIC images in Adobe Photoshop and then merging with DAPI images.

Results

Identification and phylogenetic analysis of Frizzled family genes in Platynereis and other lophotrochozoans

In order to identify and elucidate the frizzled-related gene family during Platynereis development, RNA-seq was performed from RNA collected at early embryonic stages. De novo transcriptome assembly using Trinity software [56] and subsequent annotation by various BLAST-based bioinformatics pipelines identified nine gene models encoding Fz-related cysteine-rich domains (CRDs). These gene models corresponded to four frizzled transmembrane receptors, two sfrps, and three novel frizzled-related genes coding for proteins consisting of a frizzled-like CRD domain only, named Frizzled-related CRD 1, 2, and 3 (FzCRD-1, -2, -3). Sequences for all frizzled family gene models were further confirmed using preliminary genomic sequencing data for Platynereis (Platynereis sequencing consortium and the Arendt laboratory at EMBL, data not shown). Additionally, full-length cDNA clones were established by gene-specific PCR from stage-specific cDNA for six of the seven gene models, while for the seventh, fz9/10, a partial fragment (~1000 bp) of the open reading frame was cloned.

The bilaterian frizzled-related gene complement

Previous phylogenetic analyses have suggested that the pre-bilaterian ancestor likely had four Frizzled receptors (Fz1/2/7, Fz4, Fz5/8, and Fz9/10) and two sFRPs (sFRP1/2/5 and sFRP3/4) [17, 18]. This conclusion was reached with limited searches within lophotrochozoan/spiralian taxa [17] and excluded sequences for sFRPs [18]. To refine the analysis, frizzled-related sequences from Platynereis, other lophotrochozoan/spiralian species with sequenced genomes (the annelids Capitella telata and Helobdella robusta; the mollusks Lottia gigantea,Crassostrea gigas, and Aplysia californica) [65–68], and from other phylogenetically informative metazoan taxa were collected and subjected to various phylogenetic analyses (see Additional file 1: Table S1 for complete list; see “Methods” for details).

In agreement with previous studies [17, 18], our phylogenetic analysis based on alignments of the CRD domains strongly supports an ancestral frizzled-related gene complement consisting of four frizzled receptors, fz1/2/7, fz4, Fz5/8, and fz9/10, and two sFRPs, sfrp1/2/5 and sfrp3/4 (Fig. 2). Consistent with previous evidence [17], our analysis suggests independent evolutionary origins of the two ancestral sfrp genes. Under this scenario, the sfrp1/2/5 gene originated from a domain fusion after duplication of a Frizzled CRD domain and a NTR domain prior to the diversification of the Frizzled receptors. sFRP3/4, which clusters strongly within the frizzled receptors, was proposed to arise from a similar but separate and later domain fusion event. Phylogenetic analysis of NTR domain-containing proteins including the sFRP NTR domains supports this scenario of independent origins (Additional file 1: Table S1; Additional file 3: Figure S1). The sFRP3/4 cluster is far apart from the sFRP1/2/5 cluster within the NTR tree. Contrary to previous studies [17, 18], our analysis did not find support for a close relationship between the chordate specific fz3/6 and fz1/2/7 genes. Instead we found a cluster consisting of Fz3/6 and sFRP3/4 that forms a sister group to Fz1/2/7 and Fz5/8. It should be noted that the two previous studies that found a close relationship between Fz1/2/7 and Fz3/6 either had low support for this particular node [17], or did not include sFRP sequences in their analysis [18]. One cannot say with any confidence whether the differing relationships supported in our and previous studies are an artifact of the limited phylogenetic signal within the CRD domain or if our analysis indeed indicates a more complicated evolutionary relationship between Fz3/6 and the other frizzled receptors.

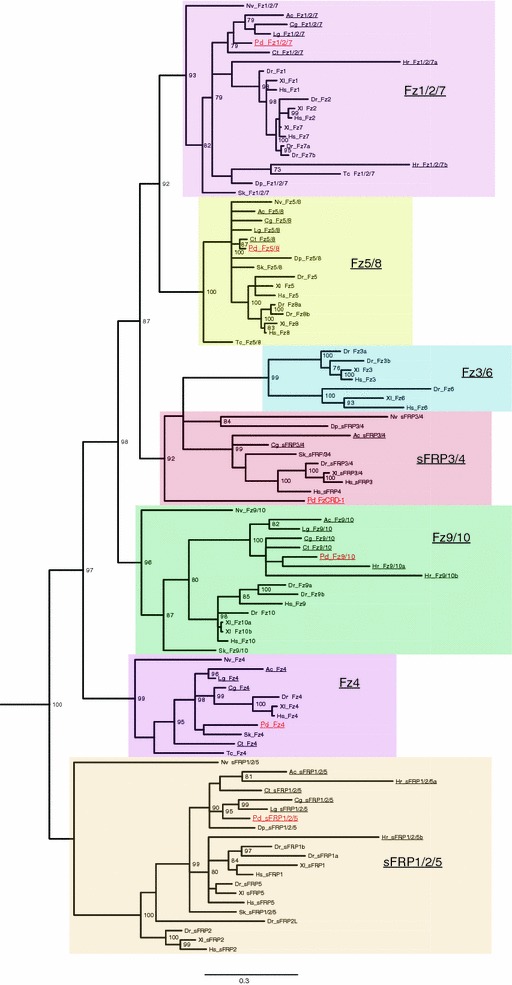

Fig. 2.

Phylogenetic analysis of Frizzled-related Cysteine-rich domains identifies a conserved lophotrochozoan gene complement. Cysteine-rich domains (CRDs) of frizzled transmembrane receptors and secreted frizzled-related proteins were aligned with MAFFT and analyzed with Mr Bayes. Posterior probabilities greater than 70 % are shown. The CRD of smoothened was used as an outgroup (not shown). Groupings of frizzled and sFRP subfamilies are highlighted with colored boxes. Platynereis dumerilii proteins are highlighted in red font, and cluster within frizzled subgroups with high posterior probability. Lophotrochozoan/Spiralian frizzled-related proteins are underlined. The novel Platynereis dumerilii protein FzCRD-1 clusters with the sFRP3/4 and vertebrate specific Fz3/6 subgroups with high posterior probability. The scale bar indicates the estimated number of substitution per site. The highly derived CRDs of Platynereis dumerilii sFRP3/4, FzCRD-2, and -3 were removed from this analysis. Species abbreviations: Ac, Aplysia californica; Cg, Crassostrea gigas; Ct, Capitella teleta; Dp, Daphnia pulex; Dr, Danio rerio; Hr, Helobdella robusta; Hs, Homo sapiens; Lg, Lottia gigantea; Nv, Nematostella vectensis; Pd, Platynereis dumerilii; Sk, Saccoglossus kowalevskii; Tc, Tribolium castaneum; Xl, Xenopus laevis

The lophotrochozoan frizzled-related gene complement

Of the six lophotrochozoan species included in our study (Fig. 2; Table 1; Additional file 1: Table S1), five (Aplysia californica, Capitella teleta, Crassostrea gigas, Lottia gigantea, and Platynereis dumerilii) possess well-conserved orthologous genes for five of the six ancestral frizzled-related genes (fz1/2/7, fz4, fz5/8, fz9/10, and sfrp1/2/5). The notable exception is Helobdella robusta, whose modified gene set suggests the loss of fz4 and fz5/8 and duplication of fz1/2/7, fz9/10, and sfrp1/2/5. Orthologs for the remaining frizzled-related gene, sfrp3/4, are either absent or strongly divergent in 5 of the 6 lophotrochozoans (Fig. 2; Table 1; Additional file 1: Table S1; Additional file 2: Table S2; Additional file 3: Figure S1). Indeed, a previous study indicated that annelids and mollusks might have lost an orthologous sfrp3/4 gene based on its absence in the Capitellateleta and Lottia gigantea genomes [17]. However, in our analysis, we were able to confirm that the mollusk Crassostrea gigas possesses an sfrp3/4 gene with well-conserved CRD and NTR domains (Fig. 2; Additional file 3: Figure S1). Platynereis dumerilii also has a bona fide sfrp3/4 that can be identified by its well-conserved NTR domain despite its highly divergent CRD domain. In addition, we have identified genes consisting of only a CRD domain that cluster strongly with other sfrp3/4 genes in both Platynereis dumerilii (fzCRD-1) and Aplysia californica, although the lack of a NTR domain in the latter may be due to an incomplete gene model.

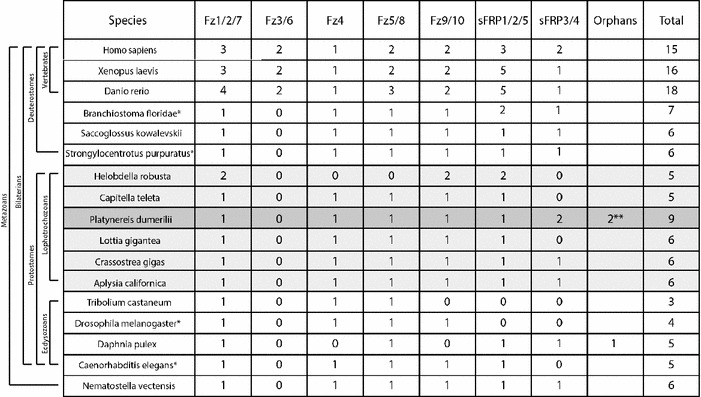

Table 1.

The frizzled-related gene complement in metazoans

Frizzled-related subfamilies are named on the top. Animal clades/subgroups are indicated with brackets to the left of the ‘species’ column. Each column lists the number of identified frizzled-related genes in each subgroup within each species

Orphans are additional highly divergent frizzled-related genes that cannot be placed within one of the six subfamilies

Number of all frizzled-related genes for each species is listed in the column on the left. Lophotrochozoans are highlighted in light gray. Platynereis is highlighted in dark gray

Annotations for fz9/10 in D. melanogaster and C. elegans are from Schenkelaars et al. [18]

* See explanation in Additional File 1

** refers to FzCRD-2 and FzCRD-3

The Platynereis frizzled-related gene complement

Our phylogenetic analysis confirms that Platynereis retained single, well-conserved orthologs of the four ancestral Frizzled receptors and sfrp1/2/5, with each one clustering strongly with their respective class of frizzled-related genes. The exception to this is the divergent sfrp3/4 gene, which contains a highly derived CRD domain linked to a conserved NTR domain (Additional file 3: Figure S1), and was therefore removed from our CRD analysis. Of the three fzCRD-1, -2, and -3 genes unique to Platynereis, one, fzCRD-1, clusters with the sfrp3/4 gene family (Fig. 2) suggesting a more recent evolutionary origin by a duplication of a CRD domain of a sfrp3/4 gene. This hypothetical event may have also contributed to the divergence of the CRD domain of Platynereissfrp3/4. The CRD domains of fzCRD-2 and -3 are highly derived, and while they do cluster with frizzled-related genes, they do not cluster reliably within any of the six ancestral frizzled-related gene families (data not shown). Thus, we speculate that these genes arose from one of the six ancestral frizzled-related genes by duplication of the CRD only. Confirmed by transcriptome and genomic data, fzCRD-2 and -3 are expressed at later larval stages, and only at very low levels in early stages (Additional file 4: Table S3; data not shown). Thus, fzCRD-2 and -3 were not further included in our study.

Structure of the frizzled-related proteins in Platynereis

For six of the seven frizzled-related genes in Platynereis, cDNA clones covering the full coding region were generated. The exception is fz9/10, of which a 944 bp fragment coding for the C-terminal end of the CRD and most of the transmembrane domain was cloned. However, the full protein sequence model is confirmed by preliminary genomic data, obtained from the Platynereis sequencing consortium and the Arendt laboratory at EMBL (data not shown) and a partial Platynereis Fz9/10 protein sequence in GenBank covering the CRD and the N-terminal end of the transmembrane domain [GenBank:AHI16256]. Thus, we have confidence in each of our frizzled family gene models, enabling a structural analysis of the encoded predicted frizzled-related proteins.

The four conserved frizzled receptor genes fz1/2/7, fz4, fz5/8, and fz9/10 encode proteins of 568aa, 603aa, 571aa, and 594aa length, respectively (Figs. 3, 4a). Each frizzled receptor protein possesses a N-terminal membrane localizing signal peptide rich in hydrophobic residues followed by an extracellular CRD that contains 10 highly conserved signature cysteine residues [69]. In addition, each Frizzled receptor contains a conserved NXT/S potential glycosylation site exactly six residues after the second cysteine residue. This motif is common to all Frizzled transmembrane receptors and may play a role in Wnt ligand binding [21]. The conserved CRD domains are connected via poorly conserved linker regions to moderately conserved seven-pass transmembrane domains. Each Platynereis frizzled receptor retains signature amino acid residues in the linker region and transmembrane domains that are unique to each of the four Frizzled receptor classes that were identified in a recent study [18]. Each Frizzled receptor protein also contains an intracellular conserved KTXXXW motif two residues after the seventh transmembrane domain. This motif has been shown to facilitate Wnt signaling by binding to the PDZ domain of Dishevelled [70]. PdFz1/2/7 and PdFz4 have a conserved ES/TXV motif at the C-terminal end. This motif is found only in Fz1/2/7 and Fz4 orthologs in other species, and has been shown in vertebrates to interact with APC and Discs Large [71].

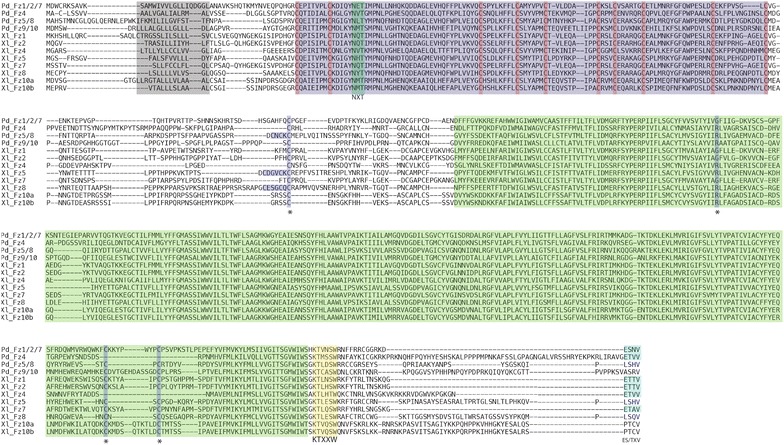

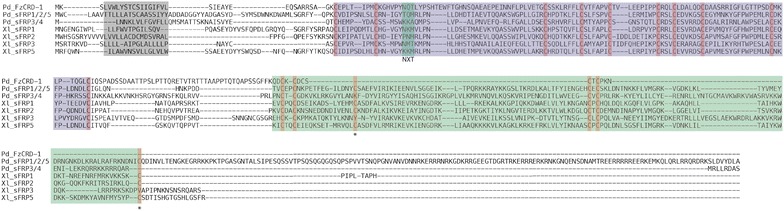

Fig. 3.

Conserved structural features of Platynereis Frizzled transmembrane receptors. Multiple alignments of full-length protein sequences for frizzled transmembrane receptors from Platynereis dumerilii (Pd) and Xenopus laevis (Xl) using MAFFT are shown. Gray box N-terminal hydrophobic localization signal. Purple box CRD domain showing conserved Cysteine residues in orange, and NXS/T motif in green. Green box Frizzled transmembrane domain. Purple boxes with asterisks: conserved ‘signature’ residues unique to each frizzled receptor class identified by Schenkelaars et al. (2012) [18], (Fz1/2/7: 1C–G–2C, Fz4: 1C–R–0C, Fz5/8: 3C–R–2C, Fz9/10: 1C–R–2C). Yellow box KTXXXW, PDZ binding motif. Blue box C-terminal ES/TXV motif of Fz1/2/7 and Fz4 homologs

Fig. 4.

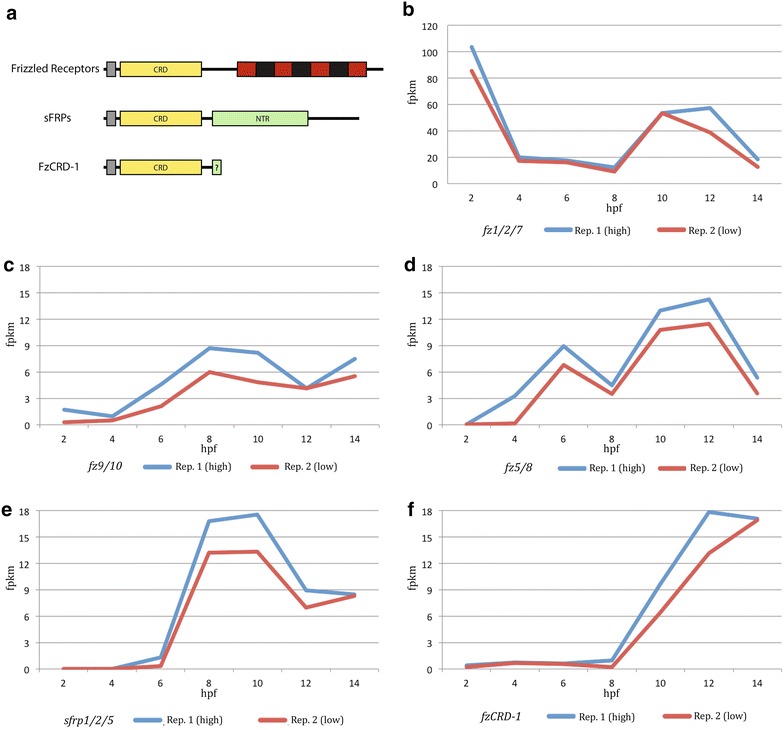

Structure and early temporal expression of frizzled-related genes in Platynereis. a Structural domains of the Platynereis frizzled receptors, sFRPs, and FzCRD-1. N-terminal gray boxes denote membrane localizing signal peptides. Yellow boxes are CRDs and green boxes are NTR domains. Black and red box is the seven-pass frizzled transmembrane domain. Small green box on FzCRD-1 indicates possible N-terminal remnant of a NTR domain. Black lines indicate poorly conserved regions. b–f Temporal expression of frizzled-related genes during early Platynereis development. b fz1/2/7, (C) fz9/10, d fz5/8, e sfrp1/2/5, and f fzCRD-1. The plots illustrate the relative expression levels in FPKM (fragment per kilobase per million mapped reads) based on RNA-seq (Additional file 4: Methods and Results). X axis: developmental time in hours post fertilization (hpf). Y axis: FPKM. Two biological replicates are shown for each graph with the replicate with the higher FPKM value at each time point (Rep. 1) denoted by blue lines and the replicate with lower values at each time point (Rep. 2) denoted by red lines

The two sfrp genes in Platynereis,sfrp1/2/5 and sfrp3/4, encode proteins of 458aa and 313aa length, respectively (Figs. 4a, 5). Both proteins have an N-terminal hydrophobic membrane localizing signal peptide followed by a CRD domain. While the sFRP1/2/5 CRD is conserved, the sFRP3/4 CRD is highly divergent and is not recognized as sFRP3/4, although it contains all of the 10 ‘signature’ cysteine residues [69]. As is the case with other sFRP1/2/5 orthologs [21], Platynereis sFRP1/2/5 does not have an NXT/S glycosylation site after the second cysteine residue. Unlike other sFRP3/4 orthologs, the highly derived CRD domain of Platynereis sFRP3/4 also lacks this motif. Both sFRP1/2/5 and sFRP3/4 contain conserved C-terminal NTR domains.

Fig. 5.

Conserved structural features of Platynereis sFRPs. Multiple alignments of full-length protein sequences for sFRPs from Platynereis dumerilii (Pd) and Xenopus laevis (Xl) using MAFFT are shown. Gray box N-terminal hydrophobic localization signal. Purple box CRD domain showing conserved Cysteine residues in orange, and NXS/T motif in green. Green box NTR domain with conserved Cysteine residues in orange. Asterisks indicate sFRP1/2/5 specific Cysteine residues

The novel fzCRD-1 gene in Platynereis encodes for a protein of 208aa in length, and consists of a CRD domain only (Figs. 4a, 5). It retains an N-terminal signal peptide rich in hydrophobic residues, indicating it is likely secreted like the sFRPs. The CRD domain in FzCRD-1 is highly conserved and all 10 ‘signature’ cysteine residues are present. Unlike Platynereis sFRP3/4, FzCRD-1 possesses an NXT/S glycosylation site after the second cysteine residue that is also found in other species’ sFRP3/4 and all Frizzled receptors [21]. C-terminal to the CRD domain is a variable region linked to a motif that might be a N-terminal fragment of a NTR domain. This short sequence retains a CXC motif that is conserved at the N-terminal end of NTR domains of sFRP3/4 proteins, in contrast to the CXXC motif found in the NTR of sFRP1/2/5 proteins. Thus, both the structural features of FzCRD-1 and the phylogenetic analysis of its CRD domain support the scenario that this gene originated by duplication of the N-terminal domain of an sfrp3/4 gene. Due to the presence of a membrane localization signal peptide and a highly conserved CRD domain, it is tempting to speculate that FzCRD-1 may also be involved in Wnt ligand binding either to sequester and antagonize Wnt signals extracellularly or perhaps modify the signal in other ways. In fact, a protein of similar structure is produced as a splice variant of fz4 in vertebrates. This splice variant introduces a stop codon immediately after the region coding for the CRD domain, producing a variant protein that has been shown to both positively and negatively regulate Wnt signaling depending on the cellular context [72].

Frizzled-related genes during early Platynereis embryogenesis

As Frizzleds play a central role in receiving and modulating Wnt signaling, and Wnt/beta-catenin signaling has been shown to be essential for a global and reiterative binary specification module acting throughout early Platynereis development [48], we wanted to know which frizzled-related transcripts are present in early stages. To do so we determined the temporal expression of frizzled-related genes by stage-specific transcriptional profiling (RNA-seq). RNA-seq was performed from whole RNA collected at 2-h intervals from the one-cell zygote to a stereogastrula stage: 2 hpf (one-cell zygote), 4 hpf (~8 cells), 6 hpf (~30 cells), 8 hpf (~80 cells), 10 hpf (~140 cells), 12 hpf (~220 cells), and 14 hpf (~330 cells). Subsequent stage-specific quantification of expression levels resulted in transcriptional profiles for each transcript throughout early development (see “Methods”).

Our transcriptional profiling found five of the nine frizzled-related genes, fz1/2/7, fz5/8, fz9/10, sfrp1/2/5, and fzCRD-1 are expressed at significant levels (Fig. 4b–f), and fz4, sfrp3/4, and fzCRD-2 and-3 not present at detectable levels within the first 14 h of development (Additional file 4: Table S3). The highest expression levels, measured in fragments per kilobase per million mapped reads (FPKM), were observed for fz1/2/7 (maternal: ~90; zygotic: ~60), followed by sfrp1/2/5 and fzCRD-1 (both with zygotic: ~20), fz5/8 (zygotic: ~15), and fz9/10 (zygotic: ~10). It should be noted that ‘maternal’ refers to expression levels in the one-cell zygote at 2 hpf. Measurements of the two biological replicates (blue, replicate 1: higher measured level; red, replicate 2: lower measured level) were in good agreement (Fig. 4b–f; Additional file 4: Table S3). Significant maternal expression was only observed for fz1/2/7 (~ 90) and fz9/10 (< 2), followed by a dramatic drop in transcript levels for fz1/2/7 from zygote to 8-cell stage (from 90 to 20), indicating a rapid degradation of this mRNA. The earliest zygotic onset of transcription was observed for fz5/8 and fz9/10 between the 8-cell and 30-cell stage (4 to 6 hpf), followed by sfrp1/2/5 between the 30-cell and 80-cell stage (6 to 8 hpf), and fzCRD-1 after the 80-cell stage (8 to 10 hpf). A strong increase in zygotic expression of fz1/2/7 and fz5/8 was also observed after the 80-cell stage (8 to 10 hpf). To confirm the results from transcriptional profiling and to determine the spatial localization of fz-related transcripts, we determined expression domains by whole-mount in situ hybridization for fz1/2/7, fz5/8, fz9/10, sfrp1/2/5, and fzCRD-1 throughout early development.

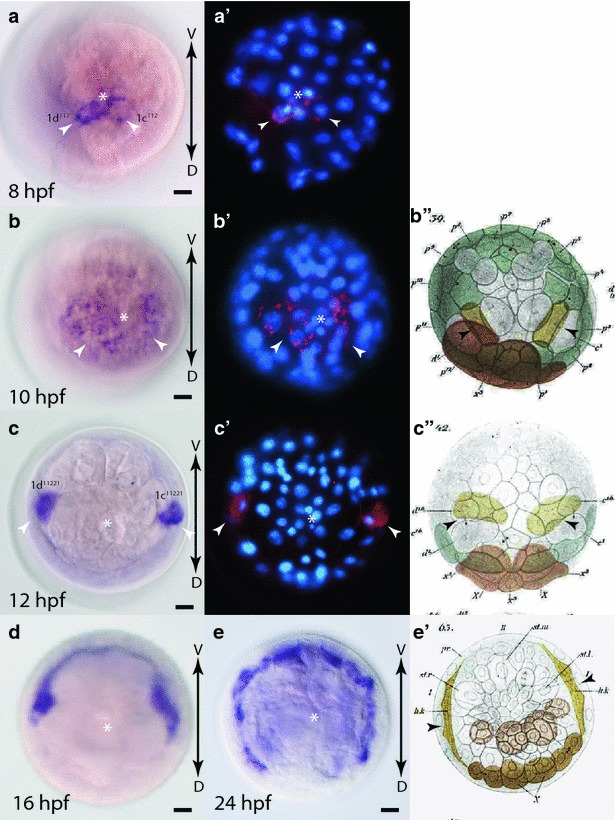

Early expression of Platynereis fz1/2/7

In situ hybridization of one-cell stages confirms a high maternal contribution of fz1/2/7 revealing that transcripts are concentrated within the clear, yolk-free cytoplasm segregated towards the animal pole of the zygote (Figs. 4b, 6a, a′, b, b′). Transcripts are inherited by each daughter cell after early cleavage divisions forming 4- and 8-cell stage embryos (Fig. 6c, c′, d, d′). At the 30-cell stage (6 hpf), transcripts are enriched in the 2d cell lineage and in the four 1q11 cells at the animal pole (Fig. 6e, e’). As the clear cytoplasm of the zygote is preferentially segregated towards these cells [42], this expression may represent the remaining maternal transcripts. By 8 hpf, fz1/2/7 expression is no longer detectable in the animal-pole cell lineages (1q11); however, remaining maternal transcripts or new zygotic expression can be observed within the 2d cell progeny (Fig. 6f, f′). In addition, zygotic expression can be observed in the C quadrant (Fig. 6g, g′) most likely within the 2c lineage. By 10 hpf, areas of expression can be seen within all four quadrants (Fig. 6h–i″). Within the D quadrant (Fig. 6g, g′, h, h′), expression is strongest in the 2d1121 and 2d1122 cell lineages, in the C quadrant (Fig. 6i, i′, i″) in the 2c cell lineage, and in the A and B quadrant most likely in the 2a and 2b cell lineages, respectively. It should be noted that these are the domains of strongest expression with some weaker ubiquitous expression throughout the whole embryo.

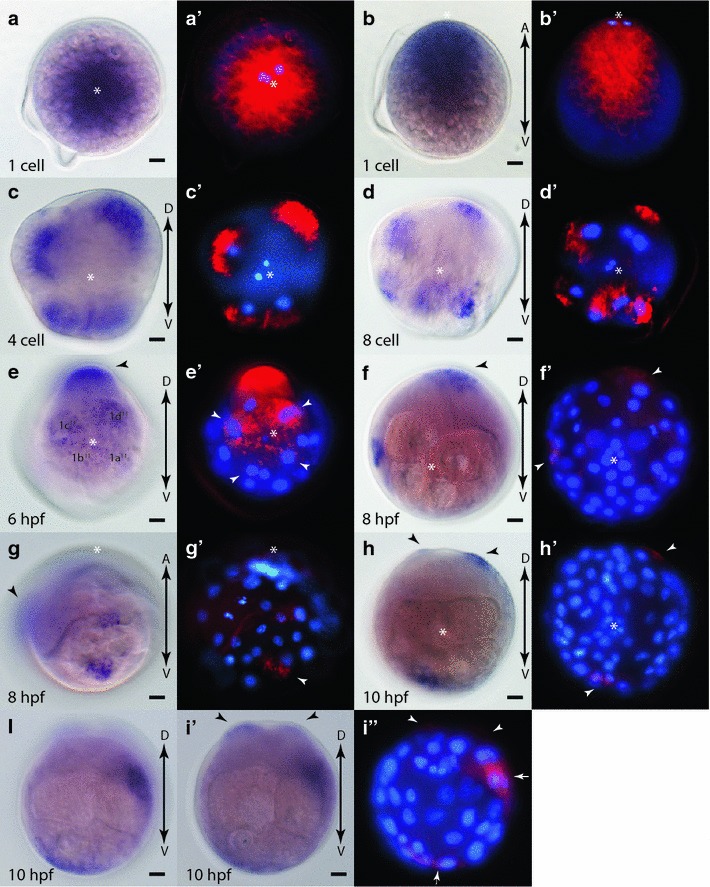

Fig. 6.

Expression of fz1/2/7 during early development in Platynereis. a–i′ WMISH of fz1/2/7, and a′-i″ false color images of the WMISH (red) overlaid with DAPI-stained nuclear images (blue). Animal-pole view (a, a′) and side view with animal pole up (b, b′) of 1 cell embryos. 4-cell (c, c′), 8-cell (d, d′) embryos, animal-pole view. e, e′ 6 hpf embryo, animal-pole view. White arrowheads point to 1q11 cells. 8 hpf embryo animal pole (f, f′) and side (g, g′) views. White arrowheads in f′ point to expression domains in c and d quadrants. White arrowheads in g′ point to expression in c quadrant. 10 hpf embryo animal pole (h, h′) and vegetal pole (i, i′, i″) views. White arrowheads in h′ point to expression in d and a/b quadrants. White arrowheads in i″ point to expression in 2d1121 and 2d1122 progeny. White arrows in i″ point to expression in c, a and b quadrants. Asterisks mark the animal pole. Black arrows indicate the orientation of the dorsal–ventral (D-V) and animal-vegetal (A-V) axis. Black arrowheads in e, f, g, h, and i′ indicate 2d cell lineage. White asterisk in a–h′ indicates location of animal pole

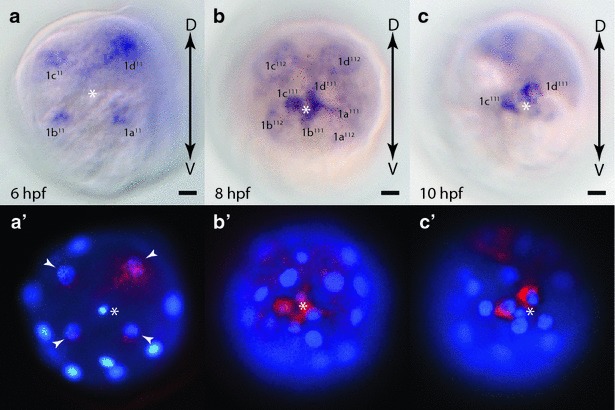

Early expression of Platynereis fz9/10

While having a minimal maternal contribution (Fig. 4c), the first detectable zygotic expression of fz9/10 is observed at 6 hpf with enrichments in the 2d cell lineage, and the four animal-pole micromeres 1q11 (Fig. 7a, a′) similar to the expression pattern observed for fz1/2/7 at 6 hpf. At 8 hpf (Fig. 7b, b′) and 10 hpf (Fig. 7c, c′, d, d′), expression is likely confined to the C quadrant, specifically to 2c and its progeny. No stronger expression was observed in the A and B quadrants at these stages.

Fig. 7.

Expression of fz9/10 during early development in Platynereis. a–d WMISH of fz9/10, and a′–d′ false color images of WMISH (red) overlaid with DAPI-stained nuclear images (blue). a, a′ 6 hpf embryo, animal-pole view. White arrowheads point to 1q11 cells. Arrow points to 2d expression. b, b′ 8 hpf embryo, animal-pole view. White arrowhead points to expression in c quadrant. 10 hpf embryo, animal pole (c, c′) and side (d, d′) views. White arrowheads point to c quadrant expression. White asterisks mark animal pole. Black arrows indicate the orientation of the dorsal–ventral (D-V) and the animal-vegetal (A-V) axis

Early expression of Platynereis fz5/8

fz5/8 is first expressed at 6 hpf (Fig. 4d) and is confined to the four animal-pole micromeres, 1q11 (Fig. 8a, a′). Between 6 and 8 hpf, the 1q11 micromeres divide, each forming one smaller animal-pole daughter cell (1q111, the rosette cells) and a larger vegetal-pole daughter cell (1q112). At 8 hpf, fz5/8 expression is observed in all of the progeny of 1q11, with the strongest expression in the four rosette cells, and weaker expression in the progeny of 1q112 cells, the dorsal and ventral cephaloblasts (Fig. 8b, b′). By 10 hpf, expression is strongest in the two rosette cells of the C and D quadrant, 1c111 and 1d111, while weaker expression remains in 1a111 and 1b111, and in progeny of the dorsal cephaloblasts, 1c112 and 1d112 (Fig. 8c, c′).

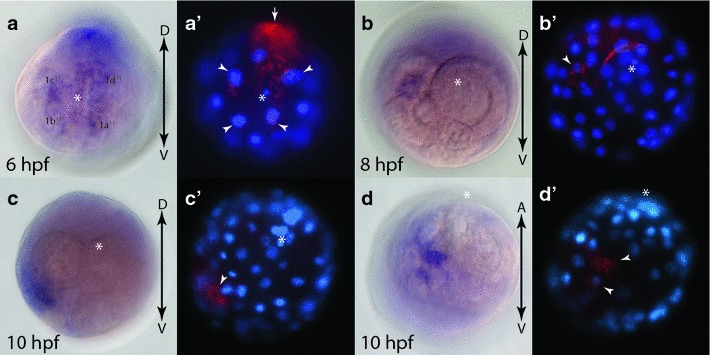

Fig. 8.

Expression of fz5/8 during early development in Platynereis. a–c WMISH of fz5/8, and a′, c′ false color images of WMISH (red) overlaid with DAPI-stained nuclear images (blue). a, a′ 6 hpf embryo, animal-pole view. White arrowheads indicate 1q11 cells. 8hpf (b, b′) and 10 hpf (c, c′) embryos, animal-pole view. White asterisks indicate animal pole. Black arrows indicate the orientation of the dorsal–ventral axis (D-V)

Early expression of Platynereis sfrp1/2/5

The Wnt antagonist sfrp1/2/5 is first expressed around 6 hpf (Fig. 4e) in the four animal-pole micromeres 1q11 cells (Fig. 9a, a′). Similar to fz5/8 expression, sfrp1/2/5 is expressed strongly in the rosette cells 1q111 and less in their sister cells 1q112 at 8 hpf (Fig. 9b, b″). In addition to this animal-pole domain, sfrp1/2/5 is also weakly expressed in one single cell in each quadrant closer to the vegetal pole, the third micromeres 3a, 3b, 3c, and 3d (Fig. 9b′, b″). At 10 hpf, expression remains strong within the animal-pole cell lineages, but unlike fz5/8, sfrp1/2/5 expression is not primarily confined to the rosette cells. Instead similar strong expression is seen throughout the progeny of the dorsal and ventral cephaloblasts (Fig. 9c, c″). At this time, the four expression domains located more vegetally in each quadrant are stronger and more distinct (Fig. 9c′, c″). Lateral views show that each domain entails 2 to 3 individual cells likely the progeny of the 3q lineage (Fig. 9d–d″; Additional file 5: Figure S2). Although not well studied, the 3q lineages are thought to primarily contribute to the formation of ectomesodermal muscles and the stomodeum envelope [45].

Fig. 9.

Expression of sfrp1/2/5 during early development in Platynereis. a–d, b′–d′ WMISH of sfrp1/2/5, and a′, b″–d″ false color images of WMISH (red) overlaid with DAPI-stained nuclear images (blue). a, a′ 6 hpf embryo, animal-pole view. White arrowheads indicate 1q11 cells. b, b′, b″ 8 hpf embryo focusing on animal pole (b) and mid-section (b′) of embryo. Expression in rosette cells can be seen at the animal pole in b and b″. White arrowheads indicate more vegetal expression domains in a, b and d quadrants, likely in the 3q lineage. c Quadrant expression is not yet distinct. c, c′, c″ 10 hpf embryo with an animal-pole view focusing on animal pole in c, and mid-section view in c′. Expression throughout 1q11 progeny can be seen at animal pole in c and c″. White arrowheads indicate expression in 3q lineage in all four quadrants. d, d′, d″ 10 hpf embryo side view from c quadrant showing shallow focus (d) and deeper focus (d′). d Quadrant is to the left, and b quadrant is to the right. White asterisks indicate animal pole. Black arrows indicate direction of dorsal–ventral (D-V) and animal-vegetal (A-V) axis

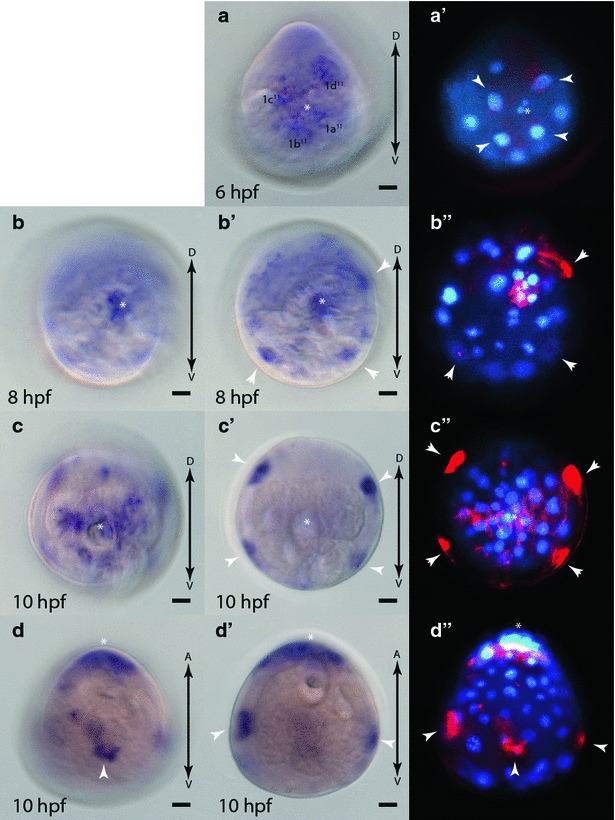

Early expression of Platynereis fzCRD-1

The unique fzCRD-1 gene, encoding a CRD domain related to sFRP3/4, has expression beginning at 8 hpf (Fig. 4f). At this stage, fzCRD-1 expression is confined to two cells near the animal pole, likely the dorsal cephaloblasts 1c112 and 1d112 (Fig. 10a, a′). Between 8 and 10 hpf, the dorsal cephaloblasts give rise to three progeny each, and fzCRD-1 is expressed in each of them (Fig. 10b, b′). Two of these cells, 1c11221 and 1d11221, cease dividing, migrate to the interior, assume a bilaterally symmetric lateral position, and give rise to a circular structure adjacent to the ciliated cells of the prototroch called the ring canal (or ‘head kidney’) first described by Wilson in 1892 [44] (Fig. 10b″, c″, e′). By 12 hpf, fzCRD-1 expression is restricted to these two cells and the expression increases as they ingress and migrate laterally (Fig. 10c, c′). By 16 hpf, these two cells have elongated and are beginning to encircle the inside of the embryo continuing to express fzCRD-1 (Fig. 10d). By 24 hpf, they have almost completely encircled the embryo to form the ring canal (Fig. 10e) [46]. Expression of fzCRD-1 is still visible in the ring canal, although beginning to wane, at 48h-old larval stages (Additional file 6: Figure S3).

Fig. 10.

Expression of fzCRD-1 during early development in Platynereis. a–e WMISH of fzCRD-1, and a′–c′ false color images of WMISH (red) overlaid with DAPI-stained nuclear images (blue). a, a′ 8 hpf embryo, animal-pole view. White arrowheads indicate 1c112 and 1d112 cells. b, b′ 10 hpf embryo animal-pole view. White arrowheads indicate expression in 1c112 and 1d112 progeny. c, c′ 12 hpf embryo animal-pole view. White arrowheads indicate expression in 1c11221 and 1d11221 which have migrated laterally by this point in development. d 16 hpf and e 24 hpf embryos, animal-pole views showing continued expression in elongating ring canal. b″, c″, e′ Modified images from Wilson (1892) [44] showing migration and elongation of ring canal cells (yellow cells indicated by black arrowheads). WMISH images are shown with ventral at the top to align with Wilson’s original sketches. White asterisks indicate animal pole. Black arrows show the orientation of the dorsal–ventral axis (D-V)

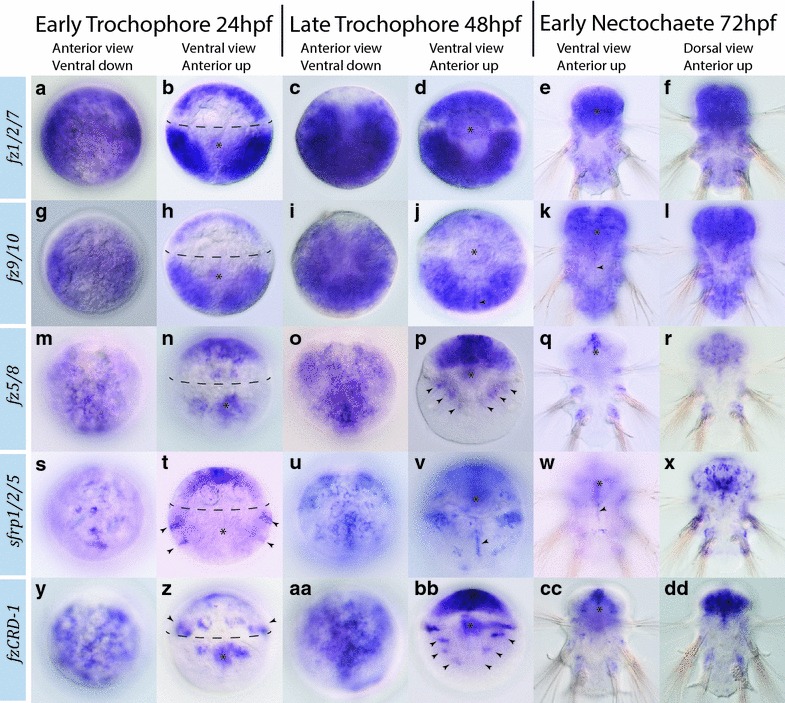

Frizzled expression in later Platynereis development

Each of the early expressed frizzled family genes, fz1/2/7, fz9/10, fz5/8, sfrp1/2/5, and fzCRD-1, continues to be expressed throughout trochophore and nectochaete larval stages (Fig. 11). fz1/2/7 and fz9/10 show similar expression patterns during this period of development. Both are highly expressed throughout ectodermal and mesodermal domains in the epi- and hypospheres at 24 hpf (Fig. 11a, b, g, h), and absent from the ciliated prototroch, presumptive stomodeum and ventral midline. By 48 hpf, expression of both fz1/2/7 and fz9/10 can be seen in the stomodeal rosette (Fig. 11d, j), and fz9/10 also begins to be more prominently expressed at the ventral midline (Fig. 11j). In 3-day-old larvae, both genes remain highly expressed throughout head and trunk ectoderm and fz9/10 additionally shows expression in ventral and dorsal midline cells (Fig. 11e, f, k, l).

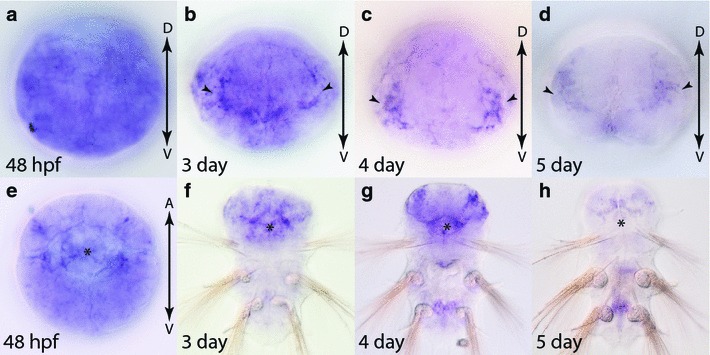

Fig. 11.

Expression of fz1/2/7, fz9/10, fz5/8, sfrp1/2/5, and fzCRD-1 in early (24 hpf) and late (48 hpf) trochopore and nectochaete (3-day old) Platynereis larvae. Gene expression analysis was performed with WMISH. Probes are listed on the left of each row. Stages and orientations are listed at the top of each column. Refer to the “Results” for details on the expression patterns. Dotted line in B, H, N, T, and Z indicate the location of the ciliated prototroch. Asterisk in ventral views indicates the stomodeum. Black arrowheads indicate the following: ventral midline expression (J, K, V and W), fz5/8 expression in chaetal sacs (P), sfrp1/2/5 expression in early forming segments (T), fzCRD-1 expression in the ring canal (Z), and bilaterally symmetric domains in the trunk (BB)

fz5/8 and sfrp1/2/5, both expressed earlier in the 1q11 cells and/or their progeny that form the episphere, continue to be expressed in the developing head and brain at 24, 48, and 72 hpf (Fig. 11m–dd). Compared to the even expression of fz1/2/7 and fz9/10 throughout the head region, both fz5/8 and sfrp1/2/5 transcripts are elevated in distinct subdomains, especially within the most anterior territories that harbor the apical organ. Our results agree with a previous study that reported anterior expression of fz5/8 and sfrp1/2/5 in the developing brain and apical organ in early trochophore larvae [35]. In addition, fzCRD-1, which is confined to the cells of the ring canal in early stages of development, shows anterior expression resembling the expression of fz5/8 within the episphere at 24 hpf (Fig. 11m, y), and throughout the developing hind- and forebrains at 48 and 72 hpf (Fig. 11o, q, r, aa, cc, dd). There is coexpression of fzCRD-1 and fz5/8 in the stomodeum at 24 and 48 hpf (Fig. 11n, p, z, bb). sfrp1/2/5 transcripts are also expressed in the stomodeum at 48 hpf, but not at the earlier larval stage. Unlike fz5/8 and fzCRD-1, sfrp1/2/5 shows a segmental expression pattern in the trunk ectoderm at 24 hpf (Fig. 11t), resembling the expression of wnt5 at this stage [54]. At 48 hpf, all three genes, fz5/8, fzCRD-1, and sfrp1/2/5, are expressed in distinct, non-overlapping domains in the trunk; fz5/8 is confined to the base of chaetal sacs (Fig. 11p), sfrp1/2/5 maintains segmental expression in the ectoderm and exhibits additional expression along the ventral midline which is also observed at 72 hpf (Fig. 11v, w), and fzCRD-1 is expressed in three pairs of bilaterally symmetrical domains in the trunk ectoderm at 48 hpf (Fig. 11bb). The bilaterally symmetric expression domains of fzCRD-1 may be the locations of the developing segmental ciliary structures, the paratrochs. fzCRD-1 is also expressed in three bilaterally symmetrical lateral domains on the dorsal side that are likely the site where growing chaetae penetrate the surface ectoderm (Additional file 6: Figure S3).

Two Frizzled family genes, fz4 and sfrp3/4, are not expressed in early embryos and 24 h larvae, but are expressed in older larvae (Figs. 12, 13). fz4 is initially expressed throughout the trochophore at 48 hpf (Fig. 12a, e), and becomes more restricted to the head region and stomodeum by 72 hpf (Fig. 12b, f). At 4 and 5 days of development, expression of fz4 becomes distinctly restricted to the stomodeum and ventral regions of the developing brain. In addition to anterior expression, fz4 is also expressed within the second and third segments of the developing trunk (Fig. 12c, d, g, h).

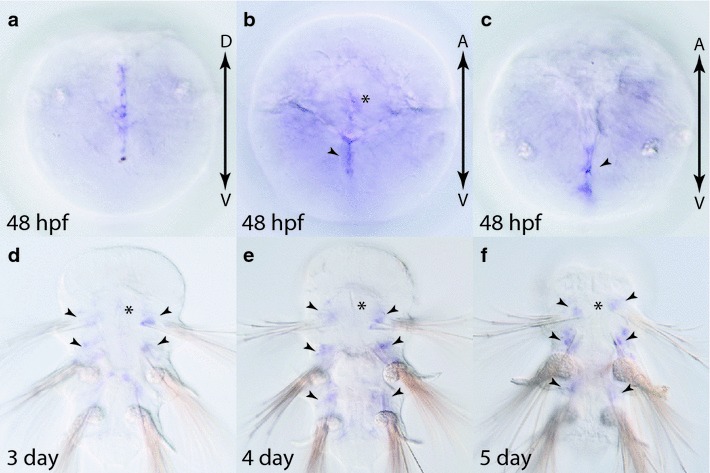

Fig. 12.

Expression of fz4 in larval stages (48 hpf to 5-day old) in Platynereis. a–d Anterior views of the head region with ventral side down. e–h Ventral views with anterior side up. Asterisks indicate the stomodeum. Black arrowheads indicate specific staining in brain. Gene expression analysis was performed with WMISH. Refer to the “Results” for details on the expression patterns

Fig. 13.

Expression of sfrp3/4 in larval stages (48 hpf to 5-day old) in Platynereis. 48 hpf embryo from posterior (a), ventral (b) and dorsal (c) view. Black arrowheads indicate ventral and dorsal midlines. d–f 3 day, 4-day and 5-day larvae ventral view, anterior up. Gene expression analysis was performed with WMISH. Refer to the “Results” for details on the expression patterns. Black arrowheads indicate expression domains anterior to parapodia. Black asterisks indicate the stomodeum

sfrp3/4 is the only frizzled family gene that was not detected in the head region or brain at any time during early and late development. Expression is first detectable at 48 hpf within the most posterior region and both the dorsal and ventral midlines (Fig. 13a–c). In addition to the midline expression, there appears to be weak expression in the stomodeum and trunk mesoderm (Fig. 13b). From 3 to 5 days of development, sfrp3/4 is restricted to small bilaterally symmetric expression domains anterior to each of the parapodia (Fig. 13d–f).

Discussion

The ancestral lophotrochozoan frizzled-related gene complement

Our phylogenetic and structural analysis of the frizzled-related genes enabled the inference of the ancestral lophotrochozoan frizzled-related gene complement: four Frizzled receptors, fz1/2/7, fz5/8, fz9/10, and fz4, and two sFRPs, sfrp1/2/5 and sfrp3/4. In agreement with previous studies [2, 17, 18], this ancestral complement was maintained from a eumetazoan, bilaterian, and protostome ancestor, and has been maintained in several extant invertebrate species within the deuterostome lineage (sea urchin and hemichordate), and three of the six lophotrochozoans (Table 1). A previous study showed that the ancestral eumetazoan wnt gene complement of 13 Wnt ligands was mostly retained within some extant deuterostomes (sea urchin S.purpuratus with 12 Wnts [24]) and some extant lophotrochozoans (Platynereis and Capitella with 12 Wnts; Lottia with 11 Wnts) [53, 54, 67]. This is significant, as it indicates that the morphological diversifications leading to most crown groups of the major bilaterian phyla happened without changes to the frizzled-related and wnt gene complements. In contrast, the morphological diversification of vertebrates was preceded by an increase from four to ten Frizzled receptors, from two to five sFRPs, and 12–19 Wnt ligands as a result of two whole genome duplications and subsequent gene loss at the base of the vertebrate lineage [2, 10, 19, 20]. However, during the major morphological diversification of vertebrate taxa since then, these gene complements were largely maintained.

Modification to the frizzled gene complement within lophotrochozoans

Comparison of the six ancestral lophotrochozoan frizzled-related genes to six extant lophotrochozoans identifies species with conserved and derived frizzled genes. Of the three analyzed mollusks, Crassostrea gigas and Aplysia californica have retained all six frizzled-related genes, and Lottia gigantea has five genes and has lost sfrp3/4. However, most frizzled-related genes in Aplysia show stronger sequence divergence than any of the Lottia genes (Fig. 2). Of the three annelid species Platynereis dumerilii has retained all six, but has three additional genes that we interpret as gene duplicates of any of the six frizzled-related CRD domains. Capitella has retained five moderately conserved frizzled-related genes and lost the sfrp3/4 gene. By far, the most derived gene set of the six lophotrochozoans was observed for the leech Helobdella robusta (loss of fz4, fz5/8, sfrp3/4, and duplications of fz1/2/7, fz9/10, and sfrp1/2/5). Again, morphological diversification within lophotrochozoan taxa is mostly not accompanied by changes to the frizzled-related gene complement. One exception is the leech Helobdella, which is regarded as a morphologically derived clitellate annelid [73], and which also exhibits a highly divergent frizzled-related gene set. It will be interesting to see whether a similar divergence can be observed in all clitellate species, or only in distinct sub-lineages.

Divergence and loss of the sfrp3/4 gene in lophotrochozoans

The sfrp3/4 gene was the one of the six ancestral frizzled-related genes that experienced the most significant evolutionary changes within the lophotrochozoan lineages from loss in three species (Lottia, Capitella, and Helobdella) [17], high sequence derivation in two species (Platynereis, Aplysia), potential gene duplication in Platynereis, and strong conservation in Crassostrea. It will be interesting to see whether other lophotrochozoan species show a similar bias to evolutionary change for the sfrp3/4 gene. Our phylogenetic and structural analysis identified fzCRD-1 and a bona fide sfrp3/4 gene as potential duplicates of an ancestral lophotrochozoan sfrp3/4 gene in Platynereis. Interestingly, the CRD domain of sfrp3/4 is highly derived, compared to the moderately conserved CRD domain of fzCRD-1 that may indicate divergence in function of the two. Furthermore, we found strong expression of fzCRD-1 in early embryonic lineages and strong expression in the head region of later stages, whereas the sfrp3/4 gene was not expressed in embryonic stages and the head region but only in some trunk lineages. It is possible that both of these expression domains may represent functions of an ancestral sfrp3/4 gene that were split in two after gene duplication as observed for other duplicated genes [74, 75].

Novel frizzled-related genes in lophotrochozoans

Our study found several novel frizzled-related genes in lophotrochozoans that encode Fz-related CRD domains only (3 in Platynereis, 1 in Aplysia) that we interpret as more recent lineage-specific duplications from one of the six ancestral frizzled- related genes. These novel frizzled-related CRD genes resemble sFRPs in structure with an N-terminally located secretion signal and a potential Wnt ligand binding CRD domain, but lacking a C-terminal NTR domain. Especially the domains of FzCRD-1 in Platynereis are reminiscent structurally of a fz4 splice variant in vertebrates that codes for a secreted protein consisting of only the N-terminal CRD of Fz4 and which can regulate Wnt signaling [72]. Therefore, these novel CRD genes might also function as modulators (antagonists or agonists) of Wnt signaling pathways. It is tempting to speculate that duplicates of frizzled-related CRD domains represent a frequently used toolbox during evolution to make cell populations inert to otherwise instructional Wnt signals and prevent certain cell fate changes.

Fz1/2/7 is a candidate for involvement in early beta-catenin-mediated binary cell fate decisions

One of the purposes of this study was to identify candidates among the frizzled- related genes that might be part of the molecular mechanism to orchestrate beta-catenin-mediated binary cell fate specification [48]. Based on the developmental RNA-seq time course and in situ hybridization, fz1/2/7 emerged as the most likely candidate as its mRNA is maternally provided at high levels, and is inherited by all daughter cells during the first few rounds of cell division. High maternal contributions of fz1/2/7 transcript have also been found in the cnidarian C. hemispherica and the echinoderm P. lividus [31, 32] suggesting that a function of fz1/2/7 gene during the earliest stages of embryogenesis might be an evolutionarily conserved feature. In P. lividus, maternal fz1/2/7 was also shown to be required for nuclear localization of beta-catenin protein [31]. Thus, fz1/2/7 is an excellent candidate for future functional studies in Platynereis. However, even if fz1/2/7 is directly involved in beta-catenin localization, it is not known through what molecular mechanism this could occur. A previous study of early wnt ligand expression in Platynereis revealed no obvious candidates or maternal contributions of any of the known wnt ligands, suggesting a Wnt ligand-independent mechanism for beta-catenin-mediated binary specification [54]. There is precedence for a mechanism like this in the nematode C. elegans where a similar global but highly derived beta-catenin-mediated binary specification mechanism has been described [51, 52]. Although every binary cell fate switch in C. elegans is dependent on a functional Frizzled receptor, many instances appear to be Wnt ligand independent [76]. The molecular mechanism underlying the Wnt ligand-independent beta-catenin-mediated binary cell fate specification in C. elegans remains largely unknown.

An anterior Wnt antagonizing center in Platynereis embryos

During early embryogenesis in Platynereis, we found a dynamic expression of the sfrp1/2/5 and fz5/8 genes in the animal-pole cell lineages that will form the apical organ and the head region. Expression in the head region is also observed for both genes in early and late larval stages of Platynereis, consistent with a previous study [35]. These anterior expression domains are reminiscent of similar anterior territories expressing orthologous genes found in several other metazoans including cnidarian, cephalochordate, echinoderm, and hemichordate embryos and larvae [25–29, 77], and have been proposed to be part of an evolutionarily conserved anterior Wnt antagonizing signaling center in metazoans [3], to pattern anterior neuroectoderm in deuterostomes [33, 34, 78], and to constitute a developmental program to establish the apical territory and apical organ in invertebrates [35]. The restricted expression of these two genes in the most animal cell lineages early on may suggests that a similar Wnt antagonizing signaling center is being established during cleavage stages in Platynereis embryos.

Early cell lineage expression of frizzled-related genes predicts expression domains in later larvae

The five frizzled-related genes transcribed during early embryogenesis in Platynereis, fz1/2/7, fz9/10, fz5/8, sfrp1/2/5, and fzCRD-1, are all expressed in the four most animal cells (1q11) and their progeny. 1q11 cells are born at the ~32-cell stage and will divide to generate hundreds of cells that will form the entire head region including the eyes, brain structures and apical organ of later larval stages [44, 45]. Intriguingly, all five of these genes continue to be expressed prominently in the anterior head region of early and late larval stages. Two, fz1/2/7 and fz9/10, exhibit an additional and prominent early expression domain in the 2d cell lineage that will give rise to the trunk ectoderm of the larvae [45]. Remarkably, these are the only two frizzled genes that are prominently expressed throughout the trunk region in later larval stages. Thus, frizzled-related genes appear to maintain cell lineage restricted expression domains from embryo to larval stages. Similar lineage restrictions have been observed for embryonic and larval expression of wnt ligands in Platynereis embryos [54]. Whether these lineage restrictions indicate that potential embryonic polarities and signal receiving territories established by frizzled-related genes are maintained through larval stages or whether they support separate embryonic and larval functions remains to be determined.

Frizzled-related gene expression is biased towards anterior expression

Overall we observed a preference for anterior expression of frizzled-related genes in embryonic lineages that extends through larval stages with prominent expression domains of fz1/2/7, fz9/10, fz5/8, fz4, sfrp1/2/5, and the possibly derived sfrp3/4-related gene fzCRD-1 in the head region of larval stages (Figs. 11, 12). This is in contrast to our previous study of the 12 wnt ligands in Platynereis that are predominantly expressed in various posterior domains in the trunk region of larvae (9 of 12 wnts), and only sparsely in the head region (4 of 12 wnts) [54]. Thus, the majority of Wnt secreting cells are localized in posterior domains, while the majority of cells expressing frizzled-related genes and capable to receive, modulate, or inhibit Wnt signals are located in anterior territories of embryo and larvae. Wnt signaling is intimately tied to the early establishment of embryonic polarity and axis formation in many metazoan embryos [3, 79] with posterior expression of selected wnt ligands, and anterior expression of selected frizzleds and sfrps observed in several taxa. The use of posterior Wnt signaling and anterior Wnt inhibition has been proposed as a ‘unifying principle of body plan development in animals’ [3]. Thus, the observed bias in expression of frizzled-related genes anteriorly and of wnt ligands posteriorly in Platynereis might be the evolutionary remnants and products of an ancient mechanism to pattern metazoan embryos along the anterior–posterior axis.

Conclusions

We present the first analysis of frizzled-related genes in lophotrochozoans, and the first comprehensive report of frizzled gene expression during spiral development and larval stages of a member of the lophotrochozoans, the annelid Platynereis dumerilii. We have determined that Platynereis and other lophotrochozoans retained an overall well-conserved set of frizzled and sfrp genes. High maternal expression identifies fz1/2/7 as the only frizzled gene to be in the right place at the right time for Wnt signaling functions during early cleavage stages. sfrp1/2/5 and fz5/8 are expressed in the most anterior cell lineages suggesting evolutionarily conserved roles in the formation of an anterior Wnt antagonizing center in this annelid. In general, frizzled-related genes show a bias towards anterior expression in early embryos and larval stages. This study provides new insights into the role of Frizzleds in Wnt signaling in a spiral-cleaving embryo and annelid larval stages, has identified numerous regions with competence to receive and/or modulate Wnt signals, and suggests the existence of an evolutionary conserved patterning system along the anterior–posterior axis of this annelid. Therefore, this study uncovered many potential Wnt signaling activities during Platynereis development, and sets the stage for a functional dissection of specific roles of this pathway in cell fate specification and patterning in this lophotrochozoan species.

Authors’ contributions

BRB and SQS conceived of the study. BRB identified and cloned frizzled-related genes, and carried out in situ hybridization experiments and phylogenetic analysis. HCH assembled the gene models and performed the RNA-seq analyses. MMP carried out and established in situ hybridizations in early stages. BRB and SQS wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Edward Letcher, Roy Holmes, Ben Wu, and Kali Levsen for handling the polychaete culture. We would also like to thank the two anonymous reviewers for comments on the manuscript. Funding for this work was provided by the Roy J. Carver Charitable Trust to SQS.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Abbreviations

- BLAST

Basic Local Alignment Search Tool

- CRD

Cysteine-Rich Domain

- DAPI

4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole

- FPKM

Fragments Per Kilobase per Million mapped reads

- Fz

Frizzled

- hpf

Hours post fertilization

- sFRP

Secreted frizzled-related protein

- nt

Nucleotide

- NTR

Netrin

- WMISH

Whole-mount in situ hybridization

Additional files

10.1186/s13227-015-0032-4 Identifiers for Frizzed-related proteins of species used for Fig. 2 and Table 1. Identifiers and accession numbers are shown for each Frizzled-related sequence that was used in various phylogenetic analyses in this study. For the analysis presented in Fig. 2 all Frizzled-related sequences were included from species (1) that represent each of the major animal branches, and (2) that in general retained an ancestral gene complement. Sequences with an asterisk were removed from the phylogenetic analysis (1) to restrict the total number of sequences shown, or (2) to remove sequences that were very divergent and had an adverse effect on the analysis e.g. long branch attraction. However, the annotations shown here are well supported by additional phylogenetic analyses (data not shown). Lophotrochozoan sequences are highlighted in red. The majority of protein sequences were obtained from NCBI, Bf_Fz5/8 and Ct_sFRP1/2/5 from the Joint Genome Institute, and Sk_Fz9/10 and Dr_sFRP2L were translated from mRNA sequences obtained from NCBI. Gene names for D. melanogaster and C. elegans are given in parentheses. Species abbreviations: Ac, Aplysia californica; Bf, Branchiostoma floridae; Ce, Caenorhabditis elegans; Cg, Crassostrea gigas; Ct, Capitella teleta; Dm, Drosophila melanogaster; Dp, Daphnia pulex; Dr, Danio rerio; Hr, Helobdella robusta; Hs, Homo sapiens; Lg, Lottia gigantea; Nv, Nematostella vectensis; Sk, Saccoglossus kowalevskii; Sp, Strongylocentrotus purpuratus; Tc, Tribolium castaneum; Xl, Xenopus laevis.

10.1186/s13227-015-0032-4 Phylogenetic Analysis of Netrin domain containing proteins identifies PdsFRP3/4 and PdsFRP1/2/5, and indicates independent origins for the two sFRP gene families. Netrin domains of sFRPs and other NTR domain containing proteins were aligned in MAFFT and analyzed with Mr. Bayes. Nematostella vectensis TIMP was used as an outgroup. Posterior probabilities greater than 70 % are shown. P. dumerilii proteins are highlighted in red. P. dumerilii sFRP3/4 clusters with other sFRP3/4 s with high posterior probability confirming its identification as an sFRP3/4 homolog despite its highly derived CRD. The sFRP1/2/5 and sFRP3/4 subfamilies are highlighted with green and blue boxes, respectively. Species abbreviations: Bf, Brachiostoma floridae; Cg, Crassostrea gigas; Ct, Capitella teleta; Dr, Danio rerio; Gg, Gallus gallus; Hs, Homo sapiens; Nv, Nematostella vectensis; Pd, Platynereis dumerilii; Sk, Saccoglossus kowalevskii; Sp, Strongylocentrotus purpuratus; Xl, Xenopus laevis.

10.1186/s13227-015-0032-4 Netrin domain containing proteins used for NTR phylogeny. Identifiers and accession numbers are given for each NTR domain containing protein. All sequences are protein sequences obtained from NCBI except Dr_sFRP2L that was translated from an mRNA sequence from NCBI. Species abbreviations: Bf, Brachiostoma floridae; Cg, Crassostrea gigas; Ct, Capitella teleta; Dr, Danio rerio; Gg, Gallus gallus; Hs, Homo sapiens; Nv, Nematostella vectensis; Pd, Platynereis dumerilii; Sk, Saccoglossus kowalevskii; Sp, Strongylocentrotus purpuratus; Xl, Xenopus laevis.

10.1186/s13227-015-0032-4 RNA-seq data for each of the nine frizzled related genes during early development of Platynereis. Quantitative expression levels are shown as FPKM for each gene at two-hour time points from 2 to 14 hpf (related to Fig. 4B–F). Independent measurements for two biological replicates are shown with higher values in the gray rows and lower values in white rows.

10.1186/s13227-015-0032-4 Expression of sfrp1/2/5 during early development of Platynereis. Additional side views of (A-D) WMISH of sfrp1/2/5, and (A’-D’) false color images of WMISH (red) overlain with DAPI stained nuclear images (blue) in 10 hpf embryos (related to Fig. 9D-D''). (A, A’) view of the A quadrant, (B, B’) view of the B quadrant. (C, C’) view of the C quadrant, and (D, D’) view of the D quadrant. All images are oriented with the animal pole up. Asterisks indicate animal pole. Double arrows indicate the orientation of the animal-vegetal axis (A-V).

10.1186/s13227-015-0032-4 Expression of fzCRD-1 in late trochophore larvae (48hpf) of Platynereis. (A) Anterior view with dorsal side up; waning expression of fzCRD-1 in the ring canal (black arrowheads). (B) Dorsal view with anterior side up. Black arrowheads indicate bilaterally symmetric domains that may indicate the site where the developing chaetae erupt from the embryo. Double arrows indicate the orientation of the dorsal–ventral (D-V) and animal-vegetal (A-V) axes. Gene expression analysis was performed with WMISH (see also Fig. 10).

Contributor Information

Benjamin R. Bastin, Email: brbastin@iastate.edu

Hsien-Chao Chou, Email: hsien-chao.chou@nih.gov.

Margaret M. Pruitt, Email: mpruitt@peds.bsd.uchicago.edu

Stephan Q. Schneider, Phone: 515-294-4956, Email: sqs@iastate.edu

References

- 1.Clevers H, Nusse R. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling and disease. Cell. 2012;149(6):1192–1205. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Croce JC, Holstein TW. The Wnt’s tale: on the evolution of a signaling pathway. Wnt signaling in developmental and disease. Mol Mech Biol Funct. 2014:16.

- 3.Petersen CP, Reddien PW. Wnt signaling and the polarity of the primary body axis. Cell. 2009;139(6):1056–1068. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.11.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kuhl M, Sheldahl LC, Park M, Miller JR, Moon RT. The Wnt/Ca2+ pathway a new vertebrate Wnt signaling pathway takes shape. Trends Genet. 2000;16(7):5. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9525(00)02028-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.James RG, Conrad WH, Moon RT. Beta-catenin-independent Wnt pathways: signals, core proteins, and effectors. Methods Mol Biol. 2008;468:14. doi:10.1007/978-1-59745-249-6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Gao B. Wnt regulation of planar cell polarity (PCP) Curr Top Dev Biol. 2012;101:263–295. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-394592-1.00008-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]