Abstract

This paper highlights the collaboration and alignment between topics and recommendations related to behavioral counseling interventions from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) and Community Preventive Services Task Force (CPSTF). Although the scope and mandates of the USPSTF and CPSTF differ, there are many similarities in the methods and approaches used to select topics and make recommendations to their key stakeholders. Behavioral counseling recommendations represent an important domain for both Task Forces, given the importance of behavior change in promoting healthful lifestyles. This paper explores opportunities for greater alignment between the two Task Forces and compares and contrasts the groups and their current approaches to making recommendations that involve behavioral counseling interventions. Opportunities to enhance behavioral counseling preventive services through closer coordination when developing and disseminating recommendations as well as future collaboration between the USPSTF and CPSTF are discussed.

Introduction

Although the scope and mandates of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) and Community Preventive Services Task Force (CPSTF) differ, there are many similarities in the methods and approaches used to select topics and make recommendations to their key stakeholders. Behavioral counseling interventions represent an important domain for both Task Forces, given the importance of behavior change in promoting health.1 This paper explores opportunities for greater alignment between the two Task Forces and compares and contrasts the groups and their current approaches to making recommendations that involve behavioral counseling interventions.

For this paper, we define behavioral counseling interventions broadly, to include interventions designed specifically to modify or reinforce health-promoting behaviors in a person or population. In the clinical setting, this is most often one-on-one counseling in primary care or referable ancillary services outside of the clinical setting (e.g., tobacco quitlines) using specific state-of-the-art techniques such as motivation-based interviewing that assesses readiness to change and focuses on goal setting.2 In the community setting, behavioral interventions are more diverse and can include one-on-one interactions, group-focused interventions, community media campaigns, multicomponent interventions, and economic incentives to change behavior.

Overview of Task Forces

The USPSTF is an independent panel of medical experts in evidence-based medicine and primary care, founded in 1984 to provide recommendations on the provision of clinical preventive services in primary care practice. The panel includes primary care experts in internal medicine, family medicine, pediatrics, obstetrics/gynecology, nursing, and behavioral medicine. Panel members are volunteers with administrative support from the USDHHS Agency for Healthcare for Research and Quality (AHRQ). AHRQ convenes the USPSTF three times each year to develop new and revise existing recommendations for screening tests, preventive medications, and behavioral counseling interventions. The USPSTF recommendations focus on asymptomatic people who may receive these preventive services as part of a well care visit. The USPSTF website (www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org) has the recommendation library, draft work plans, and evidence reviews.

The CPSTF comprises independent volunteer experts in population health from various sectors. It was established in 1996 to complement the work of the USPSTF and provide recommendations about evidence-based preventive services and policies that should be implemented in community-based settings such as workplaces, schools, and faith-based settings. The CPSTF also recommends strategies to ensure and optimize delivery of preventive services in health systems, such as the use of reminders for cancer screening or team-based care for blood pressure control.3 CPSTF recommendations, reviews, and supplementary information are available at www.thecommunityguide.org. Just as AHRQ supports the work of the USPSTF, the CDC provides administrative, technical, and dissemination support for the CPSTF; however, panel recommendations are not necessarily endorsed by the U.S. government. The work of both groups is highly collaborative, engaging stakeholders and subject matter experts in all aspects of the process from topic selection to dissemination. This engagement helps ensure the most relevant questions for practice are addressed in both USPSTF and CPSTF recommendations.

In addition to providing practice recommendations, both the USPSTF and the CPSTF identify evidence gaps that could be closed through further research. Since 2010, both Task Forces are required to prepare annual reports for the U.S. Congress highlighting key evidence gaps. These reports are a rich source of research questions with salient policy impacts.

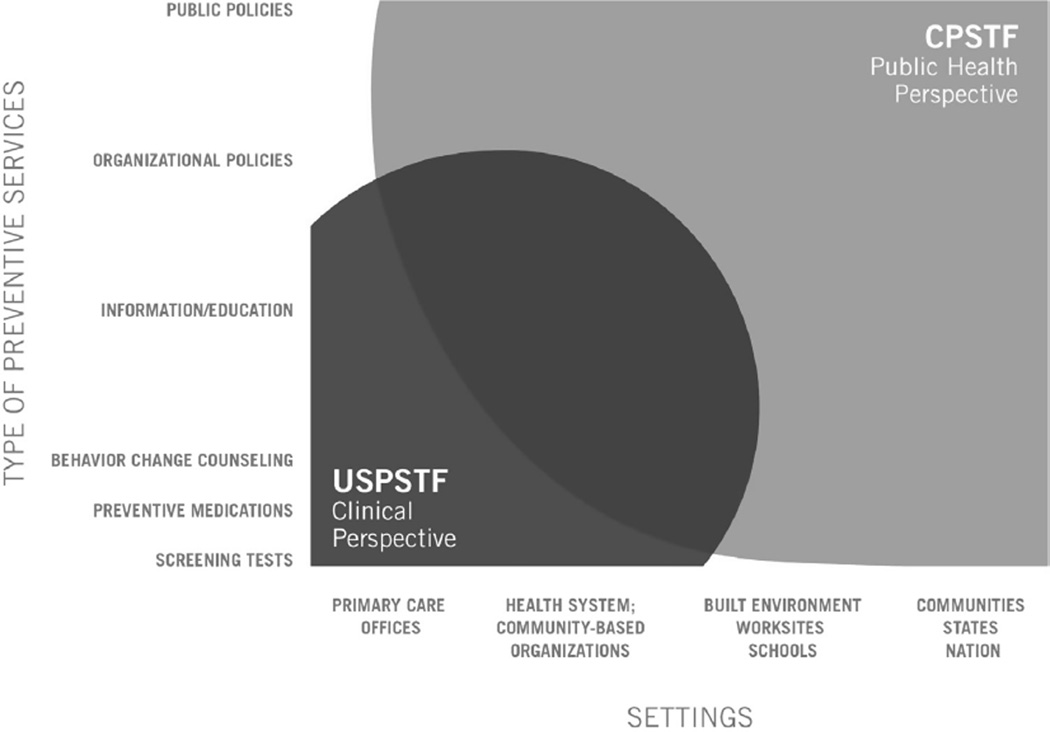

The recommendation libraries of the two Task Forces are largely complementary. They are designed on the concept that health improvement occurs when health delivery systems, public health, community-based organizations, and public policy work in harmony to achieve optimal health outcomes.4 These interdependencies, as exemplified in Figure 1, are often explicitly discussed in recommendations from the Task Forces.

Figure 1.

Overlap between the Community Preventive Services Task Force (CPSTF) and the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) in scope of settings and services.

Recommendation Library Content

Many community-based behavioral counseling interventions serve a dual role, supporting clinical preventive care while also serving people who access them through channels other than their healthcare provider. For example, many tobacco quitline users access them as a result of community information campaigns promoting their use, but patients receiving clinic-based cessation counseling and therapy are also often referred to quitlines. Although USPSTF recommendations are generally limited to interventions that can be delivered in primary care, their scope extends to interventions, such as quitlines, that are accessible to patients through direct referral. As a result, similar community-based behavioral counseling interventions may be relevant to the work of both Task Forces. This overlapping scope, demonstrated in Figure 1, poses both challenges and opportunities for synergies between the work of the two Task Forces, and relevant linkages are often explicitly discussed in recommendations from each Task Force.

Table 1 illustrates the breadth of recommendation topics that have behavioral content integrated into the USPSTF and CPSTF libraries; topic areas may have more than one relevant recommendation, and some are integrated recommendations that combine multiple interventions, including screening. The USPSTF has 9 areas with recommendations regarding behavioral counseling interventions that can be delivered in primary care or referred to external services. In comparison, the CPSTF has recommendations with behavioral content in 15 topical areas. Both Task Forces have active recommendations in ten shared areas: alcohol misuse, adolescent risk behaviors, promotion of healthful diet and physical activity, child maltreatment prevention, obesity prevention, prevention of sexually transmitted infection, skin cancer primary prevention, and prevention of tobacco use.

Table 1.

Active Behavioral Counseling and Intervention Topics in USPSTF and CPSTF Libraries

| Behavioral recommendations | USPSTF | CPSTF |

|---|---|---|

| Alcohol | x | x |

| Adolescent risk behaviorsa | x | |

| Healthful lifestyle (physical activity and nutrition) | x | x |

| Breastfeedinga | x | |

| Cancer (breast, cervical, colorectal)a | x | |

| Child maltreatment | x | x |

| Depression managementa | x | |

| Diabetes managementa | x | |

| Illicit drug usea | x | |

| Motor vehicle injury prevention | x (inactive) | x |

| Obesity in adults and children | x | x |

| Sexually transmitted infections | x | x |

| Skin cancer | x | x |

| Tobacco use in adults, pregnant women, and children | x | x |

| Vaccinationsa | x | |

| Youth violence | x (inactive) | x |

| Worksite health promotiona | x |

Topics addressed by only one task force.

CPSTF, Community Preventive Services Task Force; USPSTF, U.S. Preventive Services Task Force.

Methodologic Approaches of the Task Forces

The general approach used by both the USPSTF and CPSTF to identify and synthesize evidence, and draw conclusions on the effectiveness of prioritized interventions, is presented in Table 2. Owing to its focus on interventions for individual patients within the clinical setting, the intervention studies available in USPSTF reviews as a whole tend to be randomized trials that provide information on the ultimate health outcomes of interest to decision makers (e.g., mortality, cardiovascular events, quality of life). By contrast, the CPSTF focus on population-level intervention tends to result in bodies of evidence in which non-randomized studies commonly have behavioral outcomes as endpoints. As Table 2 indicates, the methods of each Task Force share many general characteristics, with specific features that are appropriate to the nature of the research that they most typically encounter.5–7

Table 2.

Shared and Specific Features of USPSTF and CPSTF Processes

| Elements of review and recommendation process |

Shared features | USPSTF features | CPSTF features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Define intervention and hypothesized mechanism | Develop analytic framework (AF) to guide review process | Interventions either universal or targeted to selected group, based on risk factors Focus on clearly specifying key questions | Interventions often targeted to entire target population Focus on clearly identifying hypothesized causal mechanisms |

| Identify inclusion/exclusion criteria for systematic review of studies | Clearly defined, objective criteria | Evidence base for effectiveness questions often limited to RCTs | Generally includes both RCTs and quasi-experimental study designs |

| Synthesize results of multiple studies | Dual abstraction to improve reliability | Pooling via meta-analysis when appropriate and possible | Pooling often done via descriptive summary statistics |

| Address applicability of findings to stakeholders | Critical applicability questions carefully considered | Focus on U.S. primary care populations and clinically relevant intervention contexts | Addresses broad range of intervention contexts |

| Summarize benefits and harms | Identify all outcomes that may be important for assessment of net benefit | USPSTF and CPSTF features are similar | USPSTF and CPSTF features are similar |

| Identify and summarize evidence gaps | Identification of evidence gaps is important for both task forces | USPSTF and CPSTF features are similar | USPSTF and CPSTF features are similar |

| Develop recommendation | Consensus process based on transparent criteria | Letter grades (A, B, C, D, I) reflect combination of (1) magnitude of net benefit and (2) certainty of estimated net benefit | Findings reflect level of confidence that intervention has a meaningful net benefit |

CPSTF, Community Preventive Services Task Force; USPSTF, U.S. Preventive Services Task Force.

Conceptual Basis for Evidence Collection and Synthesis

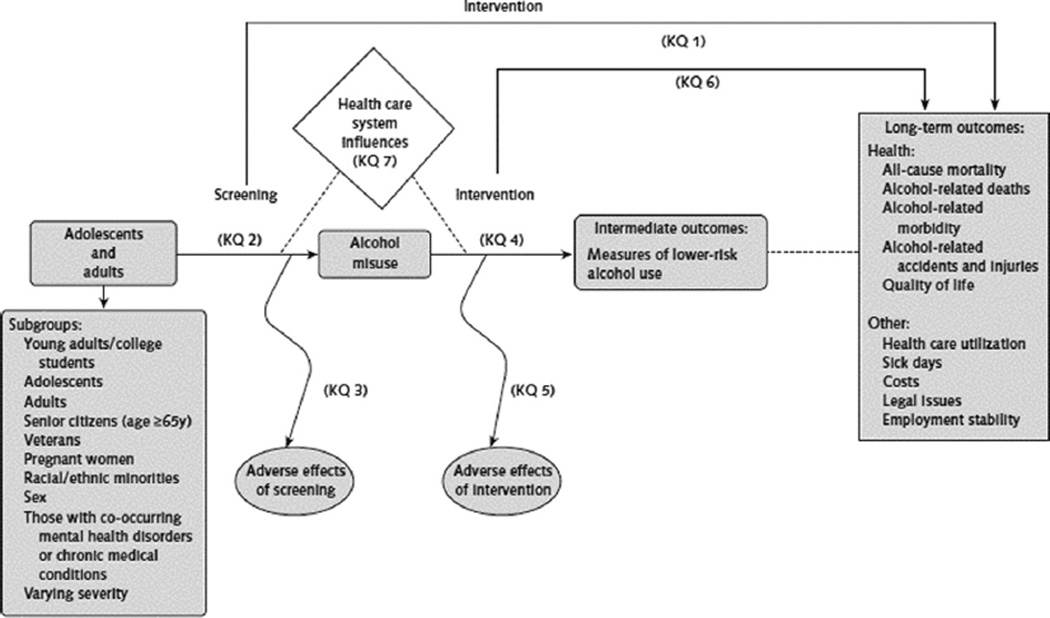

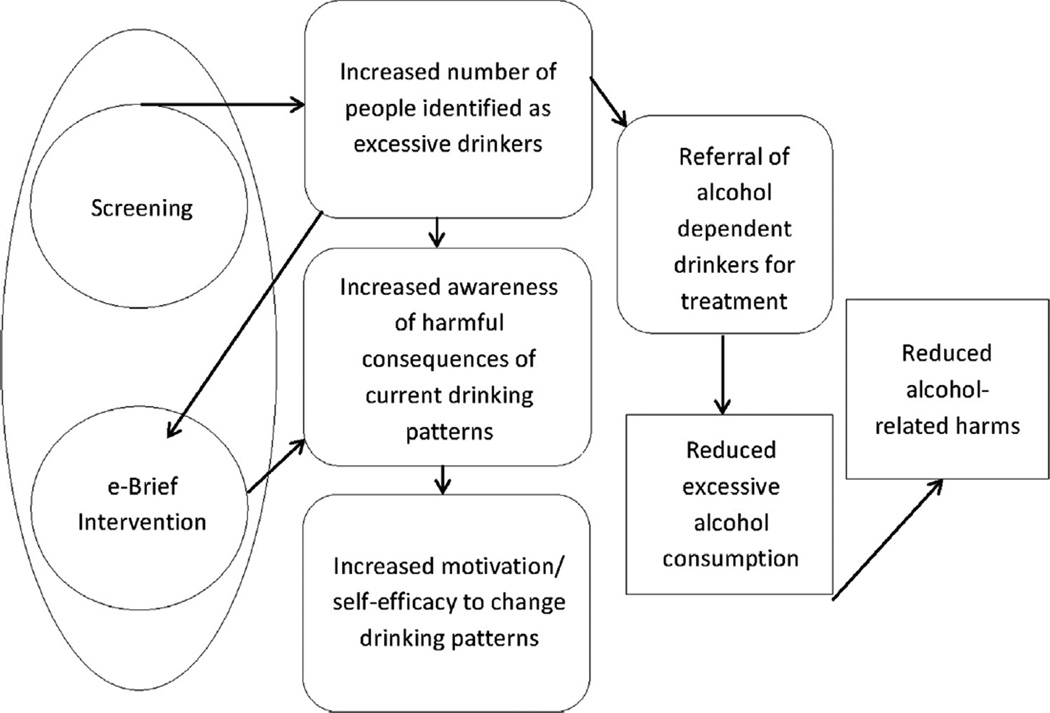

As an example of how the focus and methods of the Task Forces differ when applied to similar behavioral counseling interventions, consider the work of the two Task Forces on interventions that involve screening people for high-risk alcohol use and providing them with brief risk reduction counseling, often referred to as screening and brief intervention (SBI). The foundation of all recommendations by both the USPSTF and the CPSTF is the analytic framework for the recommendation. The framework sets the scope of the systematic review and helps to define the key questions for developing a recommendation statement. The USPSTF framework explicitly identifies all key questions to be addressed in the review, as well as any subgroup analyses that the Task Force is interested in exploring. By contrast, the CPSTF framework for a related intervention, electronic SBI (e-SBI), has a greater focus on explicating the causal pathway from the intervention to the downstream outcomes of interest, and explicit research questions and subgroup analyses are presented separately. One noteworthy difference between Figures 2 and 3 is that unlike the USPSTF framework, in the CPSTF conceptual model, increasing the number of people screened and identified is an important intermediate variable to consider when assessing the overall effect of the intervention. Whereas the USPSTF is primarily focused on assessing the likely net benefit of individual patient–provider interactions, the CPSTF takes a population-level perspective for which the reach and scale of an intervention is an important element. In fact, one of the primary rationales for the CPSTF evaluation of e-SBI was the possibility that low uptake of traditional SBI8 could be improved by making it easier to deliver within and outside of the clinical context.

Figure 2.

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force analytic framework for screening, behavioral counseling, and referral in primary care to reduce alcohol misuse.

Source: Jonas DE, Garbutt JC, Brown JM, et al. Screening, Behavioral Counseling, and Referral in Primary Care to Reduce Alcohol Misuse. Comparative Effectiveness Review No. 64. AHRQ Publication No. 12-EHC055-EF. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2012.

Note: KQ 1–6 refer to key questions addressed by this framework.

Figure 3.

Community Preventive Services Task Force (CPSTF) analytic framework for electronic screening and brief intervention.

Note: Oval, intervention; Circles, distinct intervention components; Rounded boxes, intermediate outcomes; Rectangles, recommendation outcomes (outcomes used to inform CPSTF finding).

The analytic frameworks of both Task Forces specify key intermediate results and health outcomes of interest, and then define which outcomes are considered appropriate as the basis for a recommendation. Health outcomes are disease states or health events such as myocardial infarction, quality of life, or mortality. Health outcomes are distinct from intermediate results that potentially lead to a health outcome. Examples of intermediates include biometric outcomes such as blood pressure, or behavioral outcomes such as changes in physical activity, dietary patterns, or cigarette consumption. Although the USPSTF can make recommendations based on such intermediate results if epidemiologic data support a strong causal association with the health outcome(s) of interest, this option is used uncommonly. By contrast, the CPSTF regularly makes recommendations based on intermediate outcomes, which are often the only available study outcomes for their interventions and populations of interest. An example of an intermediate outcome that meets the evidentiary standards as an acceptable outcome for both Task Forces is cigarette consumption, which has a strong and well-understood causal association with death from lung cancer or heart disease. Given this clear linkage, both the USPSTF and CPSTF confidently conclude the effectiveness of tobacco behavioral counseling interventions for improving health, even though most available studies use tobacco cessation rather than health outcomes as their endpoint.

For the purposes of the CPSTF, overall evidence of causal association with health outcomes supports the use of physical activity as a recommendation outcome, even though there may be a lack of clarity about the specific magnitude of expected health benefits from a given incremental change in physical activity. This is compounded by frequent heterogeneity in outcomes and measures in behavioral counseling intervention studies that may be different from those used to establish the causal link between intermediate results and health outcomes.9 These factors lead to practical challenges in translating changes in intermediate outcomes into health outcomes. An example is the expected change in a health outcome from a statistically significant increase of 15 minutes of physical activity per day. Because the epidemiologic literature usually cannot answer specific “dosage” questions, the USPSTF often refrains from drawing conclusions based on intermediate outcomes.

Study Inclusion Criteria

One important aspect of the methods used by USPSTF and CPSTF are the study inclusion criteria for the studies in the evidence base that forms the basis for a Task Force finding. An important element is the study designs that are eligible for inclusion in the systematic review. To maximize the internal validity of included studies, the USPSTF rarely accepts evidence from designs other than RCTs for key questions about the benefits of screening or behavioral counseling interventions. For other key questions, such as the harm of screening tests or interventions, there is greater latitude in study design.

By contrast, the CPSTF is broadly inclusive of study designs with varying degrees of internal validity. Generally, only study designs considered by subject matter experts to have pervasive threats to validity related to the specific intervention being reviewed are excluded. This approach allows the CPSTF to assess the effectiveness of interventions that are often difficult or impossible to study using RCTs, as well as improve external validity by considering evidence from evaluations of population-level interventions implemented in more-pragmatic conditions than well-controlled trials. However, this approach poses challenges to the synthesis and grading of evidence.

Challenges in Synthesizing Evidence for Behavioral Counseling Recommendations

Both the USPSTF and CPSTF apply a checklist of criteria to critically appraise the body of evidence.5 However, synthesis of evidence on behavioral topics is especially challenging given the heterogeneity of interventions, outcomes, and settings that are used to build the evidence base.10

Although meta-analytic techniques are appealing for synthesizing evidence, meta-analysis is most useful when criteria regarding homogeneity are met. Focused areas such as cancer screening, in which trials use similar screening tests and address similar outcomes, are more likely to be sufficiently homogeneous for pooling than behavioral counseling studies, for which the specific characteristics of interventions can vary widely. Meta-analysis is often particularly difficult for behavioral counseling intervention reviews because of additional variability in outcomes and outcome measures. In addition, the CPSTF reviews often carry the added complexity of including non-RCT evidence.11 Therefore, CPSTF reviews often transform evidence into uniform metrics as much as possible and synthesize them using descriptive statistics (i.e., medians and interquartile intervals). This method provides a summary statistic that estimates the overall effect while conveying a sense of variability in effect estimates across studies. As part of a long-term strategy to overcome challenges in synthesizing evidence from behavioral counseling intervention studies, Curry et al.9 proposed design approaches to reduce heterogeneity to facilitate evidence synthesis.

Assessing applicability is important for informing dissemination and implementation decisions and is another area where evidence synthesis is particularly challenging for behavioral counseling interventions. Key intervention variables are important in applicability. Considerations such as the credentials and training of the interventionist; the setting or modality in which interventions are conducted (in-person versus telephonic, individual versus group); and intervention “dosage” are important considerations when synthesizing evidence and formulating recommendations. The USPSTF primarily focuses on the applicability of behavioral counseling interventions in primary care settings. The CPSTF reviews interventions in a broader array of settings (e.g., school, workplace, community center, church). Population subgroups are another important dimension for applicability. Both Task Forces extract information about the demographics of study participants to understand the potential applicability across diverse populations and maximize the utility of reviews and recommendations for decision makers.

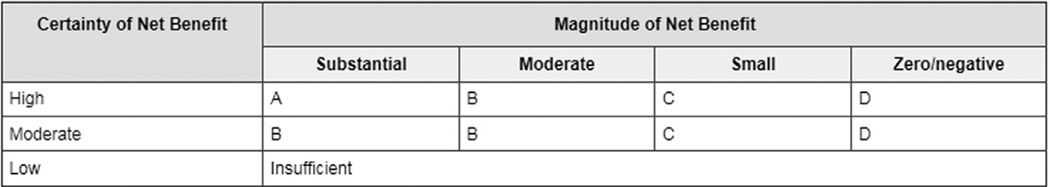

Comparative Approaches to Grading Behavioral Counseling Recommendations

Recommendation grading and language influence implementation decisions by users. The USPSTF and CPSTF recommendations and grading processes are largely similar and rely on similar criteria. Both groups categorize services as recommended, non-recommended, or having insufficient evidence. However, the USPSTF and CSPSTF use different grading processes. The USPSTF uses two main composite variables to arrive at graded recommendations for certainty and magnitude of benefit. Using a grid (Figure 4), the USPSTF assigns independent judgments for both variables. High, moderate, or low certainty is an overall appraisal of the adequacy of evidence identified in the systematic evidence review.12 The other variable used to formulate grades is magnitude of net benefit, defined as the magnitude of benefits minus the magnitude of harms. Estimating net benefit is a particularly important challenge in behavioral counseling recommendation grading, as many studies use a behavioral outcome, rather than health outcome measure. If linkage to health outcomes cannot be solidly established in a way that allows a reasonably confident estimate of health impact magnitude, a rating of low certainty might be assigned.

Figure 4.

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation grid: letter grade of recommendation or statement of insufficient evidence assessing certainty and magnitude of net benefit.

Unlike USPSTF, the CPSTF uses categorical grades that reflect confidence in the conclusion. Interventions can be recommended (or recommended against), based on either strong or sufficient evidence.5 The Task Force may also state that there is insufficient evidence to draw conclusions regarding effectiveness.13 The grid (Table 3) used to arrive at recommendations integrates some of the variables used by the USPSTF to judge certainty and magnitude. However, the CPSTF grading process is more complex because of the inclusion of non-randomized studies of varying quality; the process also involves a single categorical judgment about whether the expected intervention effect will represent a meaningful health impact if applied to an appropriate population. The grid applied (Figure 4) incorporates evidence of effectiveness (strong, sufficient, expert opinion); study execution (good, fair); study design suitability (greatest, moderate, least); number of studies; consistency among studies; effect size; and whether expert opinion was involved.5 The CPSTF does not have the equivalent of a C grade recommendation because the recommendations apply to entire populations and are provided as menus of options for decision makers. Community-level needs assessments and political, social, and technologic readiness must also be considered before implementing Community Guide recommendations. If the CPSTF is concerned that the intervention effect may not produce meaningful public health benefits, it usually issues a finding of insufficient evidence, unless the certainty of a small effect is sufficiently high, in which case the Task Force may recommend against implementation based on strong or sufficient evidence. Because several behavioral counseling interventions assessed by the CPSTF focus on upstream determinants of a wide spectrum of possible health and other outcomes, an intervention might be recommended based on evidence of improvements in some, but not all, potential outcomes. For example, a broad lifestyle change intervention might be effective at changing physical activity but not diet.

Table 3.

CPSTF Grading Grid

| Evidence of effectivenessa |

Execution- good or fairb |

Design suitability: greatest, moderate, or least |

Number of studies |

Consistentc | Effect sized |

Expert opinione |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strong | Good | Greatest | At least 2 | Yes | Sufficient | Not used |

| Good | Greatest or moderate | At least 5 | Yes | Sufficient | Not used | |

| Good or Fair | Greatest | At least 5 | Yes | Sufficient | Not used | |

| Meet design, execution, number, and consistency criterion for sufficient but not strong evidence | Large | Not used | ||||

| Sufficient | Good | Greatest | 1 | Not applicable | Sufficient | Not used |

| Good or Fair | Greatest or Moderate | At least 3 | Yes | Sufficient | Not used | |

| Good or Fair | Greatest, Moderate, or Least | At least 5 | Yes | Sufficient | Not used | |

| Expert opinion | Varies | Varies | Various | Varies | Sufficient | Supports a recommendation |

| Insufficientf | A. Insufficient designs or execution | B. Too few studies | C. Inconsistent | D. Small | E. Not used | |

Reproduced with permission from Briss et al.5

The categories are not mutually exclusive; a body of evidence meeting criterion for more than one of these should be categorized in the highest possible category.

Studies with limited execution are not used to assess effectiveness.

Generally consistent in direction and size.

Sufficient and large effect sizes are defined on a case-by-case basis and are based on Task Force opinion

Expert opinion will not be routinely used in the Guide but can affect the classification of a body of evidence as shown.

CPSTF, Community Preventive Services Task Force.

Reasons for determination that evidence is insufficient will be described as follows. A.=Insufficient designs or executions, B.=too few studies, C.=inconsistent, D.=effect size too small, E.=expert opinion not used. These categories are not mutually exclusive and one or more of these will occur when a body of evidence fails to meet a criteria for strong or sufficient evidence.

Serendipitous Alignment of Reviews

Although the USPSTF and CPSTF have distinct missions and different core audiences, the Clinical Guides from the USPSTF and the Community Guides from the CPSTF were designed to be complementary and synergistic. As the U.S. healthcare system evolves, linkages between healthcare delivery systems and community-based prevention and wellness programs are increasingly important for providing opportunities for synergies between the two guides.14

A major focus of the Community Guide has always been exploring opportunities for increasing delivery of interventions in the Clinical Guide that are effective for improving health. An intervention in the Clinical Guide that is effective at reducing mortality and morbidity has two consequences that the Community Guide can capitalize on. First, the intervention can serve as an endpoint in a Community Guide review, because its causal connection with an ultimate health improvement is demonstrated. Second, the USPSTF recommendation suggests a variety of potential effective behavioral and health system strategies to increase intervention uptake that can be prioritized for assessment by the CPSTF and inclusion in the Community Guide. For example, the CPSTF assessed the effectiveness of 11 interventions to increase delivery of USPSTF-recommended screenings for breast, cervical, and colorectal cancers. The CPSTF-recommended interventions can attempt to increase client demand for screening (e.g., through group education sessions) or access to screening (e.g., using patient navigators to reduce structural barriers).15 Interventions might also attempt to increase the number of appropriate screening tests offered or ordered by clinicians, for example, using provider reminders. This combination of USPSTF and CPSTF findings can be important for guiding practice to improve delivery of clinical preventive services.16

The Clinical and Community Guides can also align so that implementation of a USPSTF recommendation leads to actions that are further informed by a CPSTF finding. For example, the USPSTF recommends screening for adults17 and adolescents18 for depression in outpatient primary care settings when systems are adequate for efficient diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up. However, this finding offers limited guidance on implementation. A subsequent 2010 CPSTF review provided such guidance. It evaluated the effectiveness of collaborative care for depressive disorder management—a multicomponent, healthcare system–level intervention that uses case managers to link primary care providers, patients, and mental health specialists.19 As the CPSTF review was in progress, members of both Task Forces recognized the synergy and linked the two reviews to explicitly note that establishment of collaborative care systems was a way to meet the conditional statement in the USPSTF finding.

Future Collaboration Between the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force and Community Preventive Services Task Force

The topics addressed by both the USPSTF and CPSTF have substantial overlap that can enhance the utility of recommendations. The USPSTF advises clinicians that a specific behavioral counseling intervention is effective and recommended, and the CPSTF provides information on how clinicians and health systems can implement the recommendation and improve uptake. Interventions that can be referred from primary care to the community are linked to CPSTF guidance on optimal approaches toward community implementation. Similarly, public health and community-based health workers can use the Community Guide to implement evidence-based interventions to promote health, with assurance that linkages to clinical preventive services are endorsed by the USPSTF.

Recent increased interest by healthcare systems in population health management stems from increased demand from purchasers for accountable health organizations that track outcomes and population health.20 Evidence-based guidelines provide practical tools to achieve these aims, and an aligned set of recommendations from the USPSTF and CPSTF could optimize the delivery of key preventive services that are part of population health. In communities where public and community health entities join with accountable care organizations, optimal application of the Task Force guides will provide a complete approach to closing gaps in care and implementation.

The linkage and dependency of the Clinical and Community guides is especially notable in behavioral medicine. Few clinicians are trained or skilled in behavioral counseling techniques, instead relying on community resources. Unless clinics hire behavioral interventionists, providers might elect to conduct brief interventions and refer patients to community-based intervention programs; this is common for tobacco cessation and obesity interventions. Ideally, referrals would be to interventions that follow key service and implementation recommendations of both Task Forces.

Active Task Force collaboration is needed to ensure synergy for interventions that apply to both healthcare and community health. Although the Task Forces have a longstanding collaborative relationship, some additional careful planning and coordination could increase their synergy. Opportunities for additional collaboration exist in several major dimensions of Task Force work, including

aligning support of common definitions and metrics for behavioral outcomes;

aligning in the definitions of what interventions can be referred from primary care;

aligning the timing of recommendations in overlapping topical areas;

increasing convergence and cross-referencing of recommendation libraries; and

aligning dissemination and implementation efforts.

The lack of common definitions and metrics for behavioral outcomes poses challenges for systematic reviewers and guideline developers that can decrease the utility of systematic reviews and recommendations for behavioral counseling interventions. Both Task Forces could align and influence future research by pushing for standardization of behavioral outcome definitions and metrics. Two good examples include measurement of physical activity and dietary behaviors; both suffer from tremendous heterogeneity in approaches toward measurement. Ideally, both Task Forces would engage with funders and other interested groups to support consistent reporting of a few measures of greatest relevance for key health outcomes.

The USPSTF would benefit from collaboration with the CPSTF regarding the classification of interventions for referral by primary care. As stated earlier, the USPSTF will make recommendations that can be either conducted in the office or referred to another provider, including community-based services. For behavioral topics, screening is generally feasible (e.g., smoking, obesity, physical activity), but many interventions are often not feasible or practical for office settings. The USPSTF has to judge the applicability of its evidence base to understand the potential for referral and whether this is feasible. The CPSTF can play a helpful role in defining which community-based interventions are likely to be feasible for primary care referral and link to those specific USPSTF recommendations.

Close monitoring and management of the timing of topic development and release would help ensure that the sequence of work of the Task Forces in related areas is aligned and that the scope of reviews and key questions are as complementary as possible. To facilitate such alignment, topic prioritization could incorporate specific rules and criteria to elevate the priority of topics that are simultaneously addressed by both the USPSTF and CPSTF.

Efforts to increase the convergence and cross-referencing of the Task Forces’ recommendation libraries would better enable users to get a complete picture of the clinical and community interventions that are relevant to their needs. In eight behavioral domains, only one Task Force has issued recommendations (Table 1). Some areas, such as immunizations, are out of scope for the USPSTF (CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices provides these recommendations), but others (e.g., fall prevention) could be developed by the CPSTF to enhance USPSTF recommendations. Another domain is promoting cancer screening; the CPSTF has recommendations in this area that could be balanced with USPSTF recommendations on behavioral interventions in primary care that promote uptake.

Finally, both Task Forces have invested considerable resources in improving the reach and accessibility of their products.21 Enhanced website design, toolkits, dissemination case studies, and other resources help communities and providers use Task Force recommendations more effectively. Future collaboration to interweave these resources and tailor recommendations for specific audiences will optimize synergy between the two recommendation libraries.

Summary

The USPSTF and CPSTF serve complementary purposes, and the work of each is enhanced by the other. As healthcare and public health systems become increasingly aligned, the recommendations of the two Task Forces must become increasingly synergistic. This paper lays out the major similarities and differences in evidence and methods used by the Task Forces to assess the effectiveness of behavioral counseling interventions. We hope this helps users of the Clinical and Community Guides from the USPSTF and CPSTF understand how the Task Forces achieve their missions. Users should consider that the goal of the Task Forces is to provide actionable guidance to clinical and public health practitioners and community decision makers (e.g., employers, school administrators, policymakers) that addresses their most critical clinical and public health questions using the best available evidence.

Acknowledgments

Publication of this article was supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ).

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) and Community Services Task Force (CPSTF) are independent, voluntary bodies. The U.S. Congress mandates that AHRQ support the operations of the USPSTF, and that CDC support the operations of CPSTF.

The findings and conclusions in this document are those of the authors, who are responsible for its content, and do not necessarily represent the views of AHRQ or CDC. No statement in this report should be construed as an official position of AHRQ, CDC, or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Administrative and logistical support for this paper was provided by AHRQ through contract HHSA290-2010-00004i, TO 4.

David Grossman is a member of both of the USPSTF and the CPSTF.

References

- 1.Mokdad AH, Marks JS, Stroup DF, Gerberding JL. Actual causes of death in the United States, 2000. JAMA. 2004;291(10):1238–1245. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.10.1238. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.291.10.1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Whitlock EP, Orleans CT, Pender N, Allan J. Evaluating primary care behavioral counseling interventions: an evidence-based approach. Am J Prev Med. 2002;22(4):267–284. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00415-4. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0749-3797(02)00415-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zaza S, Lawrence RS, Mahan CS, et al. Scope and organization of the Guide to Community Preventive Services. The Task Force on Community Preventive Services. Am J Prev Med. 2000;18(1 suppl):27–34. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(99)00123-3. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0749-3797(99)00123-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ockene JK, Edgerton EA, Teutsch SM, et al. Integrating evidence-based clinical and community strategies to improve health. Am J Prev Med. 2007;32(3):244–252. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.11.007. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2006.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Briss PA, Zaza S, Pappaioanou M, et al. Developing an evidence-based Guide to Community Preventive Services—methods. The Task Force on Community Preventive Services. Am J Prev Med. 2000;18(1 suppl):35–43. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(99)00119-1. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0749-3797(99)00119-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zaza S, Wright-De Aguero LK, Briss PA, et al. Data collection instrument and procedure for systematic reviews in the Guide to Community Preventive Services. Task Force on Community Preventive Services. Am J Prev Med. 2000;18(1 suppl):44–74. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(99)00122-1. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0749-3797(99)00122-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guirguis-Blake J, Calonge N, Miller T, et al. Current processes of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force: refining evidence-based recommendation development. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(2):117–122. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-2-200707170-00170. http://dx.doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-147-2-200707170-00170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McKnight-Eily LR, Liu Y, Brewer RD, et al. Vital signs: communication between health professionals and their patients about alcohol use—44 states and the District of Columbia, 2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63(1):16–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Curry SJ, Grossman DC, Whitlock EP, Cantu A. Behavioral counseling research and evidence-based practice recommendations: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force perspectives. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160(6):407–413. doi: 10.7326/M13-2128. http://dx.doi.org/10.7326/M13-2128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Petticrew M, Anderson L, Elder R, et al. Complex interventions and their implications for systematic reviews: a pragmatic approach. J Clin Epidemiol. 2013;66(11):1209–1214. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.06.004. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shrier I, Boivin JF, Steele RJ, et al. Should meta-analyses of interventions include observational studies in addition to randomized controlled trials? A critical examination of underlying principles. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;166(10):1203–1209. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm189. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwm189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sawaya GF, Guirguis-Blake J, LeFevre M, Harris R, Petitti D. Update on the methods of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force: estimating certainty and magnitude of net benefit. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(12):871–875. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-12-200712180-00007. http://dx.doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-147-12-200712180-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zaza S, Briss P, Harris K, editors. The Guide to Community Preventive Services: What Works to Promote Health? New York: Oxford University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fielding JE, Teutsch SM. Integrating clinical care and community health: delivering health. JAMA. 2009;302(3):317–319. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1025. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.2009.1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sabatino SA, Lawrence B, Elder R, et al. Effectiveness of interventions to increase screening for breast, cervical, and colorectal cancers: nine updated systematic reviews for the guide to community preventive services. Am J Prev Med. 2012;43(1):97–118. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.04.009. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2012.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.The Guide to Community Preventive Services. Black Corals: a gem of a cancer screening program in South Carolina. [Accessed November 3, 2014]; www.thecommunityguide.org/CG-in-Action/CancerScreening-SC.pdf. Published 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 17.U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Recommendation summary: depression in adults: screening. [Accessed November 3, 2014]; www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Topic/recommendation-summary/depression-in-adults-screening. Published 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 18.U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Update summary: depression in children and adolescents: screening. [Accessed November 3, 2014]; www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryDraft/depression-in-children-and-adolescents-screening1. Published 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thota AB, Sipe TA, Byard GJ, et al. Collaborative care to improve the management of depressive disorders: a community guide systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Prev Med. 2012;42(5):525–538. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.01.019. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2012.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shaw FE, Asomugha CN, Conway PH, Rein AS. The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act: opportunities for prevention and public health. Lancet. 2014;384(9937):75–82. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60259-2. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60259-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spencer LM, Schooley MW, Anderson LA, et al. Seeking best practices: a conceptual framework for planning and improving evidence-based practices. Prev Chronic Dis. 2013;10:E207. doi: 10.5888/pcd10.130186. http://dx.doi.org/10.5888/pcd10.130186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]