Abstract

This paper studies relationships between social networks, health and subjective well-being (SWB) using nationally representative data of the Chinese Population—the Chinese Family Panel Studies (CFPS). Our data contain SWB indicators in two widely used variants—happiness and life-satisfaction. Social network variables used include kinship relationships measured by marital status, family size, and having a genealogy; ties with friends/relatives/neighbors measured by holiday visitation, frequency of contacts, and whether and value gifts given and received; total number and time spent in social activities, and engagement in organizations including the communist party, religious groups, and other types.

We find that giving and receiving gifts has a larger impact on SWB than either just giving or receiving them. Similarly the number of friends is more important than number of relatives, and marriage is associated with higher levels of SWB. Time spent in social activities and varieties of activities both matter for SWB but varieties matter more. Participation in organizations is associated with higher SWB across such diverse groups as being a member of the communist party or a religious organization.

China represents an interesting test since it is simultaneously a traditional society with long-established norms about appropriate social networks and a rapidly changing society due to substantial economic and demographic changes. We find that it is better to both give and receive, to engage in more types of social activities, and that participation in groups all improve well-being of Chinese people.

1. INTRODUCTION

As a measure of people’s quality of life, subjective well-being (SWB) has drawn considerable attention from various fields including psychology (Cummins & Nistico, 2002), economics (Easterlin, 1995; Easterlin, 2005), health and social indicators research (Cummins et al., 2003; Veenhoven, 2008) in both developed and developing countries alike. Despite its increasing popularity, the majority of Chinese research has targeted the relationship between SWB and income (Diener et al., 2010; Wong, Wong, & Mok, 2006; Xing, 2011; Easterlin et al., 2012). The evidence indicates that income only partially explains Chinese people’s SWB and that the other forces influencing SWB are not well understood. Among the other factors that may play significant roles, social networks and health are worthy of consideration.

Social networks reflect the collection of interpersonal contacts that people try to maintain as networks provide them with access to social, emotional, practical everyday support, and social resources that benefit their lives (Gray, 2009; Lin, 1999) Different facets of social networks may be differentially associated with SWB since social networks carry both benefits and costs (Huang and Western, 2013).

Core aspects of social networks most frequently addressed in respect to SWB include features of network structure and measures of interaction within the network. These include relationships with family members such as spouse and children (Johnson & Troll, 1992), ties with friends and relatives (Perry & Johnson, 1994), types of social activities and time spent in them, and engagements with social organizations (Silverstein & Parker, 2002). A frequent use of social networks tends to help create social capital, the set of social relationships accumulated through relationships among people (Durlauf and Fafchamps, 2005, Wu, 2014). Social capital is an important resource which people can then use in time of need.

Social networks may have positive effects on SWB if they provide ways for resolving stress, such as aiding necessary communication and support, loosening budget constraints, and helping share risk when facing difficulties in life (Udry, 1990; Yip et al., 2007). Alternatively, social networks could decrease SWB as maintaining a network takes time and money, which could have been used to improve basic consumption of individuals and families. In a similar vein, Huang & Western (2013) point out that social attachments, non-redundant information, skill knowledge and social support are four positive mechanisms to improve subjective well-being, while relational constraints and costs of maintaining relationships are two negative network effects associated with subjective well-being. The correlation between social network and SWB has been found to be generally positive and significant in the Western and developed world, with magnitudes of association varying across populations (Cornwell & Waite, 2009; Ha, 2010).

In spite of general similarities, notable cross-cultural variations in social networks exist. For example, Litwin (2010) reports that even in Continental Europe social networks are very differentially configured in Mediterranean and Non-Mediterranean countries. Similarly, and in contrast to Western society, Chinese society is heavily imbedded within Confucian cultural traditions which place a special emphasis on family ties, paternalism, and filial piety (Kuan & Lau, 2002; Ng, Phillips, & Lee, 2002). Although under-explored, it is unsurprising that there is increasing interest in this research topic in the Chinese context. To illustrate, Chan and Lee (2006) explored effects of network size and find that older adults in Beijing and Hong Kong with larger network size are more satisfied with their life.

Weng (1998) studied the relationship between SWB of Hong Kong older adults and social network types (family network, interdependent support, and friend network) and reports that the first two types contribute more to SWB. Similarly, Cheng et al. (2009) study the impact of social network types on older Chinese adults’ subjective well-being in Hong Kong. They find that distant family relationships have a much larger effect on SWB than in other cultures. Wang’s (2014) study of the Chinese city of Hefei showed that both size of social network and perceived social support has significant effects on subjective well-being, and that perceived social support acts as a mediator which could partially mediate size of social network to subjective well-being.

Bian et al. (2015) have a multifaceted evaluation on SWB of Chinese people. Relevant to our study is their definition of socially-integrated personal space in which an individual’s connection to society at large enhances his/her SWB. The underlying intuition is that socially integrated individuals feel fulfilled in their lives when they are recognized and valued by significant others surrounding them. China has a strong relational culture in which social connections are fundamental aspects of social life in traditional and contemporary eras. Bian et al. (2015) hypothesized that married persons, those actively participating in public activities, and those connected to wider social networks have higher level of SWB. With data from 12 provinces in the West of China, they found support for these hypotheses.

This paper is the first study that investigates the relationship between social networks and SWB in China using a nationally representative dataset of the full age distribution of the Chinese population. Two of the most frequent measures of SWB are happiness and life satisfaction, and they are the primary concepts used in this research. Happiness is widely viewed as a hedonic measure of well-being, emphasizing the emotional quality of everyday experience giving weight to things that make life pleasant or unpleasant at the moment. Life satisfaction is an evaluative measure tapping into people’s thoughts and feelings about their life as a whole (Kahneman & Deaton, 2010). While the concepts are related, the literature indicates that they often have different correlates, and whether this is true in China deserves investigation.

2. METHODS

2.1 Data

We use data from the 2010 national baseline of the Chinese Family Panel Studies (CFPS), a biennial survey collecting data on communities, households, and individuals across the full age distribution of the Chinese population. CFPS 2010 contains detailed demographic and socioeconomic information on families, including information on their social networks, social organizational relationships, and economic, educational, demographic, and health attributes on all individuals living in the households. This dataset also contains indicators of SWB in two widely used variants—happiness and life-satisfaction—facilitating our analysis of this outcome. Since the questionnaire is designed following the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID) in the US, CFPS is called the Chinese version of PSID.

The national baseline survey of CFPS was conducted in 25 provinces covering 95% of the Chinese population. The sampling strategy is a multi-stage stratification with probability proportional to size. At the first stage, 144 county-level units were randomly selected; in the second and the third stages, 640 villages/communities and 16,000 households were randomly selected. 14,798 households were finally surveyed and the remaining 1,202 households were mainly ineligibles, no contacts or refusals. As these surveyed households include the oversampled five provinces, we use the nationally representative sample, which has 9,661 households and 21,812 adults (Xie, 2012). CFPS contains information on all household members, defined as family members who live together and who are directly related due to genetics, marriage, adoption or fostering, or non-family members living together for more than three months who share economic resources.

We focus on a sample with non-missing happiness and life satisfaction observations. Within this sample, the number of missing values for independent variables is very few (as indicated by the summary statistics in Appendix Table A). Dropping observations with missing explanatory variables gives 19,600 observations from 9,051 households for our regressions.

3. MEASURES

The CFPS household questionnaire collects demographic and socioeconomic information on households, including their social network. Adult questionnaires collect demographic, social relationships, economic, education and health information on individuals in the household. Most information about social networks is from the household survey, such as family size, genealogy, holiday visitation, value of gifts given/received, number of gifts given, and frequency of contact with neighbors/relatives. Some network measures come from the adult questionnaire such as marital status and participation in organizations. Information on each individual’s SWB is obtained from the adult survey.

3.1 Subjective Well-being

SWB is defined with two concepts—happiness and life-satisfaction. Happiness records the degree of happiness, where she/he is asked to choose using a five-point value going between 1 (very unhappy) and 5 (very happy) as an answer to the question (“How happy do you feel about yourself?”). The life-satisfaction variable records degree of life satisfaction, where she/he is asked to choose on a five-point scale where 1 is very unsatisfied and 5 is very satisfied for the question (“How satisfied are you with your life?”).

3.2 Social Networks

Social network variables include three conceptual categories: kinship relationships, ties with friends/relatives/neighbors, and social engagement in organizations.

3.2.1. Kinship relationships

Marital status and family size measure availability and extent of spousal and familial support that may be helpful in life. The favorable SWB of married people is usually explained by the value of a partner for fulfillment of basic human needs and provision of economic resources (Chappell & Badger, 1989). We include a dummy variable indicating whether the respondent is currently married or cohabitating and a variable for the current number of family members living in the home in our analysis. As many Chinese adults live in extended families and small children, adult children, and parents can play different roles in a person’s well-being, we also measure the impact of kinship relationships on SWB by differentiating living arrangements. We include the following dummies: whether the respondent is currently living with his/her spouse, with at least one parent, with adult children 16 and older, and with younger children. For younger children, we further consider three age groups: 0–3, 4–11, and 12–15.

“Genealogy book” is a biographic record of migration and development of the family history.1 A genealogy book could serve as an important tool to record and maintain close relationships in a family which may benefit family members in various ways including labor market outcomes and SWB. For example, Guo and Yao (2013) find that rural Chinese residents with a genealogy book or an ancestor hall are more likely to exchange gifts with their relatives and more able to go out for work with larger social networks. The percent of individuals who have genealogy is 24% in CFPS 2010.

3.2.2. Ties with friends/relatives/neighbors

Chinese people treat relatives and friends as a main source of their social network. The number of friends and relatives visiting one’s family during holidays, the frequency of contacts, and the value and number of gifts given or received may reflect the size of their network and the closeness or quality of their relationships.

3.2.2.1. Holiday visitation

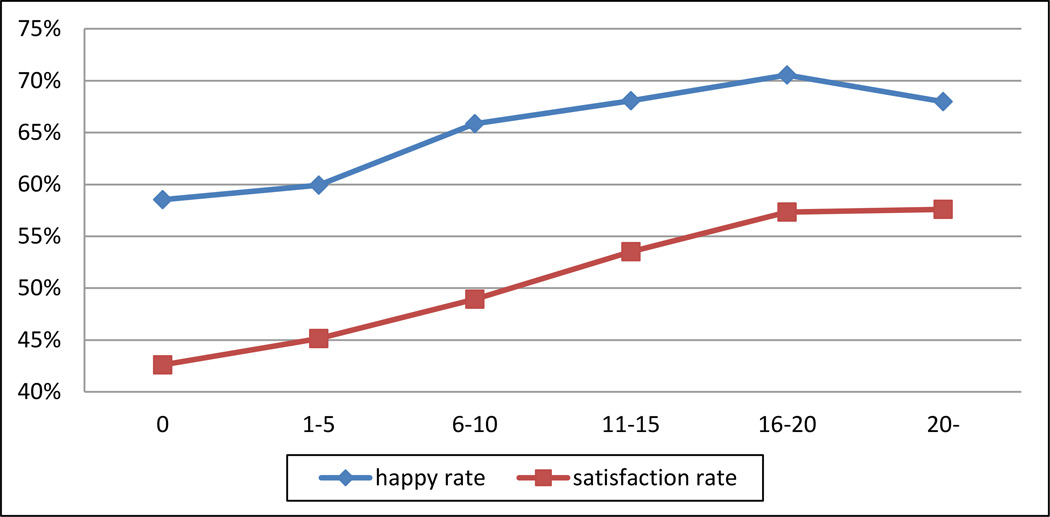

It is customary to visit with friends and relatives during important festivals, with Spring Festival the most important in China. Figure 1 presents the relationship between SWB and numbers of friends and relatives visiting one’s family during last Spring Festival. In Figure 1, the horizontal axis indicates the numbers of Spring Festival visiting friends and the vertical axis the percent of people who feel happy or satisfied, with happy and satisfied equal to 1 if the response on the original scale was either 4 or 5. Having more friends and relatives visiting during Spring Festival appears to be strongly associated with greater SWB, but such a relationship plateaus after the numbers exceed 20.

Fig. 1. The relation between number of friends and relatives and SWB.

Vertical axis is the percent of people who are happy or satisfied (either a 4 or 5 on the scale) while horizontal axis is the numbers of friends or relatives visiting during Spring Festival.

3.2.2.2. Frequency of contact with neighbors/relatives

Frequent contacts generally mean better relationship and a network with frequent contacts may be more effective in improving SWB. We have information on how frequently the respondent’s family contacted their neighbors and separately their relatives in the last year. We incorporate both variables into our analysis.2

3.2.2.3. Gifts

Chinese people maintain social networks by giving and receiving in-kind gifts or cash gifts to each other during important festivals, wedding/funeral ceremonies, and other occasions. In Chinese ancient literature, it is written that “courtesy honors reciprocity” so that giving without receiving and receiving without giving are not characteristics of healthy relationships. According to a 2009 survey in Taiyuan city, gifts expenditure accounts for 11.4% of consumption, the third largest part of expenditure besides food and education expenditure.

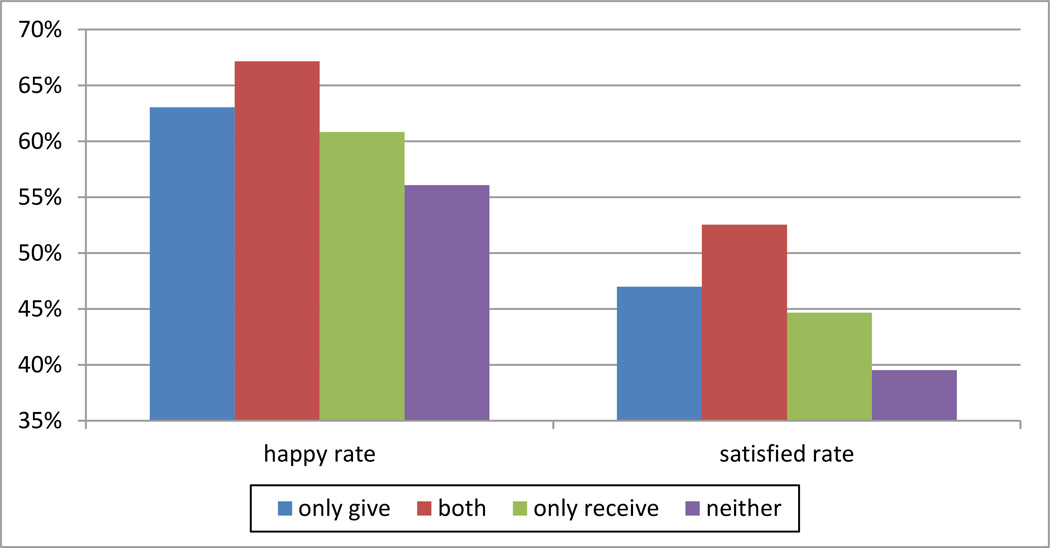

We use gift giving and receiving to index ties with friends and relatives from three perspectives. The first is to divide individuals into four types by gift giving/receiving behaviors: only giver, both giver and receiver, only receiver and neither giver nor receiver. Figure 2 compares happy/life satisfaction rates of these four gift giving/receiving types. The both giver and receiver group has the highest rates of happiness and life satisfaction, followed by only givers, only receivers, and finally the neither group.

Fig. 2.

SWB of four giving/receiving types (only giver, both giver and receiver, only receiver and neither giver nor receiver)

The second perspective considers the values of the gifts given and received last year. As the value of gifts may be more related to financial status of family, we control for the economic resources available to the family (with log Per Capita Consumption). Finally we include the number of gifts given out by the family last year as a third perspective to measures the extent of social connectedness.

3.2.3. Social activity participation and social organization engagement

Participation in social activities and social organizations may affect SWB, since it reflects how people are socially integrated with the society. In the CFPS time use module, the questionnaire records the types of social activities including reading, watching TV, internet usage, sports, recreational activities, socials, volunteering, and worshipping. It also asks how much time that the respondent spent in each activity. We construct two variables for total types of activities and total time spent in these activities.

In the adult questionnaire, we also know whether respondents take part in registered organizations, which include communist party, other political parties, a religious organization, Chinese People’s Congress (CPC), or Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC), youth league, and others. In our data, 72% of organization members feel happy and 54% of them feel satisfied, compared to 61% and 47% respectively for the non-member group.

3.3. Statistical Methods

As happiness and life satisfaction are ordered categorical outcomes with higher values indicate higher SWB, we employ the Ordered Probit model as the basic empirical method. In the data, residents reporting 1 are few (for happiness, the percent reporting 1 is 2.8%; for life satisfaction, the percent reporting 1 is 4.7%), we therefore reorganize the SWB scale into three categories—0 as unhappy/unsatisfied (originally 1 and 2), 1 as happy/satisfied (originally 3), 2 as very happy/very satisfied (originally 4 and 5). 3

We employ a short and a long set of the social network variables in two regressions. The short set includes: marital status, family size, genealogy, number of visits from friends and relatives during Spring Festival, gift giving/receiving types, natural log of net value of gifts given and received, number of gifts given, contact with neighbors, contact with relatives, total types of social activities and total time engaged in them, and whether the respondent is a member of any organization.

The short set of social network variables does not distinguish amongst several potentially relevant sub-components. Friends and relatives could affect one’s social life differently, and alternative types of social organizations may play different roles in affecting SWB. To illustrate, being a communist party member may influence SWB mainly through expanded career path opportunities, while joining a religious group may affect SWB mainly through a shared spiritual experience when traditional religious beliefs are discouraged.

Similarly, family size may represent different living arrangements that can affect one’s SWB. The long set of variables further explores variation within three central social network constructs: family size, number of friends and relatives, participation in social organizations. More specifically, we separate number of friends and number of relatives; replace family size by dummies for living arrangement (whether the respondent is living with his/her spouse, with parents, with children aged 0–3, 4–11, 12–15, and 16+); and specify organization types (Communist Party member, religious group member, Youth League member, delegate of CPC or CPPCC). Finally, we allow in Table 2 the effects of living with a spouse and living with a parent to differ depending on whether the respondent was age 45 or more or not.

Table 2.

Ordered Probit Estimates of Marginal Impacts of Happiness and Life Satisfaction Separating Friends and Relatives, Living Arrangements and Social Organizations

| Happiness | Satisfaction | |

|---|---|---|

| Married | 0.086*** | 0.042* |

| (4.13) | (1.82) | |

| Genealogy | −0.017 | −0.003 |

| (−1.54) | (−0.27) | |

| Number of friends | 0.002*** | 0.005*** |

| (2.60) | (5.54) | |

| Number of relatives | 0.001 | 0.001* |

| (1.25) | (1.84) | |

| Contact with neighbors | 0.000 | −0.000 |

| (0.89) | (−0.15) | |

| Contact with friends & | 0.001 | 0.002*** |

| relatives | (1.52) | (3.47) |

| Both give and receive | 0.035* | 0.069*** |

| (1.78) | (3.20) | |

| Only give | 0.025 | 0.037* |

| (1.24) | (1.71) | |

| Only receive | −0.015 | 0.002 |

| (−0.43) | (0.06) | |

| ln value of net gift given | 0.004* | 0.004* |

| (1.89) | (1.72) | |

| ln value of net gift received | 0.006** | 0.006** |

| (2.30) | (2.23) | |

| Number of gifts given | −0.000 | −0.000 |

| (−1.03) | (−1.15) | |

| Total # of activities | 0.011*** | 0.009*** |

| (4.03) | (3.78) | |

| Total time in activities | 0.002 | −0.001 |

| (1.56) | (−0.97) | |

| Communist party | 0.062*** | 0.085*** |

| (4.93) | (6.54) | |

| Religion member | 0.061** | 0.097*** |

| (2.22) | (2.97) | |

| Youth league | 0.017 | −0.006 |

| (1.61) | (−0.58) | |

| CPPCC | 0.091 | 0.114* |

| (1.47) | (1.76) | |

| All other groups | −0.007 | 0.003 |

| (−0.44) | (0.19) | |

| ln PCE | 0.022*** | 0.022*** |

| (4.40) | (4.21) | |

| Have job | 0.013 | 0.030*** |

| (1.31) | (2.82) | |

| In school | −0.052 | −0.072 |

| −0.012*** | −0.007*** | |

| Age | (−9.61) | (−5.37) |

| 0.000*** | 0.000*** | |

| Age squared | 0.000*** | 0.000*** |

| (10.94) | (9.05) | |

| Male | −0.045*** | −0.051*** |

| (−6.44) | (−7.65) | |

| High school | 0.051*** | −0.007 |

| (6.24) | (−0.76) | |

| Health status good | 0.132*** | 0.153*** |

| (21.42) | (21.58) | |

| Living with spouse | 0.133*** | 0.088*** |

| (5.40) | (3.41) | |

| Living with parents | 0.008 | −0.008 |

| (0.68) | (−0.73) | |

| Age 45+ living with spouse | −0.084*** | −0.032 |

| (−3.96) | (−1.53) | |

| Age 45+ living with parent | −0.046** | −0.041* |

| (−2.03) | (−1.76) | |

| Living with kid 0–3 | −0.046*** | −0.032** |

| (−3.13) | (−2.39) | |

| Living with kid 4–11 | −0.021* | −0.002 |

| (−1.84) | (−0.14) | |

| Living with kid- 12–15 | −0.033*** | −0.029** |

| (−2.85) | (−2.37) | |

| Living with kid 16+ | −0.010 | 0.004 |

| (−1.09) | (0.42) | |

| Urban | 0.011 | −0.047*** |

| (0.75) | (−3.44) | |

| East region | 0.026 | 0.011 |

| (1.53) | (0.63) | |

| Middle region | 0.034** | 0.015 |

| (2.09) | (0.90) | |

| Observations | 18,882 | 18,882 |

Absolute value of robust z-statistics in parentheses.

p<0.01

p<0.05

p<0.1.

In both regressions, we include the same set of non-social network control variables: the natural log of per capita consumption expenditure, a dummy variable for whether employed and another dummy variable for whether in school, a quadratic in age (defined as age 20 to normalize the constant term in the model to represent the youngest age in the sample), male dummy, education dummy for junior high school and above, health status defined as good and above, urban residence dummy, and regional dummies for East and Middle regions with the least prosperous West region the reference group. Household expenditures (ln PCE) are controlled since the literature has shown that a comprehensive expenditure measure is a better measure of economic resources than income in developing countries (Strauss & Thomas, 1995). The control of other demographic variables and regional dummies not only help prevent the model from suffering from omitted-variable bias, but allow us to evaluate the impacts of age and education on the SWB of Chinese residents.

In our analysis, we cluster the standard error at the community level to allow for correlated error terms. We also clustered standard errors at the family level and our results are robust to that specification.

4. RESULTS

Table 1 provides estimated regression coefficients and estimated average marginal impacts for happiness and life satisfaction from ordered probit models in which the three category variables for happiness and life satisfaction are dependent variables. Columns 1 and 3 report estimated coefficients and columns 2 and 4 average marginal impacts on the probability of being very happy/very satisfied with the short set of variables.

Table 1.

Ordered Probit Regression of Happiness and Life Satisfaction by Three Categories

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Happiness Coefficients |

Marginal Impacts Happiness |

Satisfaction Coefficients |

Marginal Impacts Satisfaction |

|

| Married | 0.435*** | 0.138*** | 0.273*** | 0.103*** |

| (13.41) | (16.50) | (9.49) | (10.22) | |

| Family Size | 0.018** | 0.006** | 0.011 | 0.004 |

| (2.31) | (2.44) | (1.55) | (1.63) | |

| Genealogy | −0.048 | −0.017 | −0.005 | −0.002 |

| (−1.47) | (−1.54) | (−0.15) | (−0.16) | |

| Number of friends relatives |

0.004*** | 0.001*** | 0.008*** | 0.003*** |

| (2.79) | (2.94) | (5.54) | (5.86) | |

| Contact with neighbors | 0.001 | 0.000 | −0.000 | −0.000 |

| (0.72) | (0.75) | (−0.31) | (−0.33) | |

| Contact with friends & | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.004*** | 0.001*** |

| relatives | (1.30) | (1.37) | (3.09) | (3.26) |

| Both give and receive | 0.097 | 0.034* | 0.187*** | 0.071*** |

| (1.58) | (1.69) | (3.13) | (3.30) | |

| Only give | 0.066 | 0.023 | 0.101* | 0.038* |

| (1.07) | (1.14) | (1.68) | (1.76) | |

| Only receive | −0.026 | −0.009 | 0.016 | 0.006 |

| (−0.26) | (−0.27) | (0.18) | (0.18) | |

| ln value of gift given | 0.012* | 0.004* | 0.011 | 0.004* |

| (1.70) | (1.79) | (1.63) | (1.72) | |

| ln value of gift received | 0.016** | 0.006** | 0.014* | 0.005** |

| (1.98) | (2.09) | (1.94) | (2.04) | |

| Number of gifts given | −0.000 | −0.000 | −0.000 | −0.000 |

| (−1.10) | (−1.16) | (−1.19) | (−1.25) | |

| Total activities | 0.030*** | 0.011*** | 0.026*** | 0.010*** |

| (3.79) | (3.99) | (3.70) | (3.90) | |

| Total time in activities | 0.005* | 0.002* | −0.002 | −0.001 |

| (1.68) | (1.77) | (−0.76) | (−0.80) | |

| Organization member | 0.091*** | 0.032*** | 0.063** | 0.024*** |

| (3.54) | (3.76) | (2.56) | (2.69) | |

| ln PCE | 0.079*** | 0.028*** | 0.069*** | 0.026*** |

| (5.10) | (5.35) | (4.65) | (4.91) | |

| Have job | 0.041 | 0.014 | 0.084*** | 0.032*** |

| (1.34) | (1.42) | (2.83) | (2.98) | |

| In school | −0.152 | −0.054 | −0.191 | −0.072 |

| (−1.20) | (−1.24) | (−1.47) | (−1.57) | |

| Age | −0.028*** | −0.010*** | −0.011*** | −0.004*** |

| (−9.83) | (−10.44) | (−4.64) | (−4.89) | |

| Age squared | 0.001*** | 0.000*** | 0.000*** | 0.000*** |

| (10.97) | (11.71) | (8.94) | (9.48) | |

| Male | −0.131*** | −0.046*** | −0.135*** | −0.051*** |

| (−6.69) | (−6.90) | (−8.01) | (−8.50) | |

| High school | 0.155*** | 0.053*** | −0.013 | −0.005 |

| (5.94) | (6.42) | (−0.53) | (−0.56) | |

| Health status good | 0.414*** | 0.132*** | 0.413*** | 0.154*** |

| (16.91) | (21.51) | (18.87) | (21.62) | |

| Urban | 0.027 | 0.010 | −0.128*** | −0.048*** |

| (0.62) | (0.66) | (−3.34) | (−3.52) | |

| East region | 0.075 | 0.026 | 0.026 | 0.010 |

| (1.40) | (1.50) | (0.54) | (0.57) | |

| Middle region | 0.103** | 0.036** | 0.043 | 0.016 |

| (2.04) | (2.18) | (0.94) | (0.99) | |

| cut1 constant | 0.139 | 0.375*** | ||

| (0.97) | (2.74) | |||

| cut2 constant | 1.190*** | 1.485*** | ||

| (8.30) | (10.73) | |||

| Observations | 18,882 | 18,882 | 18,882 | 18,882 |

Absolute value of Robust z-statistics in parentheses.

p<0.01

p<0.05

p<0.1

With regard to kinship relationship, the probability of being very happy is 13.8 percentage points higher for married people, while the probability of being very satisfied with life is 10.3 percentage points higher. This result is consistent with the literature that records a large positive impact of marriage on happiness and life satisfaction (Acock & Hurlbert, 1990). A larger family size at home increases happiness, but does not significantly contribute to life satisfaction. Having a genealogy book has no statistically significant impact on either happiness or life satisfaction, indicating that holding onto a history of the family line passed over by ancestors is less important in contemporary China than the size and quality of current social networks. Those in families with more friends and relatives visiting them during Spring Festival are happier and more satisfied with their lives. More frequent contacts with friends and relatives lead to higher satisfaction with life but no such effects for frequent contacts with neighbors. Contact with neighbors can be unpleasant if they involve attempts to settle disputes.

With regard to gift giving/receiving behavior, Table 1 shows that one’s life satisfaction will be greatly increased if one is both a giver and a receiver compared with the default group, neither giver nor receiver. Higher net values of gift giving and receiving are both positively contributed to happiness and life satisfaction, but number of gifts given does not have significant impacts on SWB. For given value of gifts, an increase in number of gifts given implies a smaller value per gift so the monetary size of the gift matters in Chinese culture.

As to the engagement in social activities and social organizations, Table 1 indicates that participating in more types of social activities associates with higher happiness and life satisfaction, and more time spent in these activities is linked with higher happiness. Also belonging to at least one social organization increases the probabilities of being very happy and being very satisfied.

For non-social network variables, our regression results are in general consistent with the findings in the literature. For example, consistent with Stone et al. (2010), we find a U-shaped relationship between SWB and age4 exists in China, with lowest levels of SWB implied by the age quadratic at age 46 for happiness and age 37 for life satisfaction. Men in China are less happy and less satisfied with their lives than Chinese women, a common finding in the SWB literature. Chinese individuals with more education, greater economic resources (ln PCE), and better health have higher SWB. Health effects are of similar size for both happiness and life satisfaction but the positive effects of ln PCE and especially education are larger for the happiness dimension of SWB. We find no statistically significant effect of being in school in any of the models. We do find that being currently employed is associated with more positive levels of life satisfaction but is not associated with current levels of happiness. While not the focus of our research, Chinese individuals in urban places are less satisfied with their lives, while those in the Middle region report higher values of happiness.

Table 2 reports estimation results for a probit model with the long set of social network variables. In Table 2, we list the estimated marginal effects of variables but our conclusions would be the same with the estimated coefficients. When number of friends and number of relatives visiting during the Spring Festivals are separated, positive impacts on SWB are mainly from friends rather than from relatives.5

When living arrangements are further categorized, we find that living with spouse significantly increases one’s SWB while living with parents decreases it. As living with spouse or parents may affect SWB differently for the young and the old, we add interactions of the age dummy of 45 and older with these two living arrangement variables. We find that the positive effect of living with spouse is more on the young while the negative effect of living with parents is only on the old. In a similar vein, Litwin and Stoeckel (2012) also report for continental Europeans that living with a spouse had a negative effect on subjective wellbeing for respondents who were at least eighty years old. Being married at very old age especially in China may bring with it significant responsibilities for caring for sick partners.

Similarly, the decrease in SWB for those who are 45 and older reflects living with their parents are more of an obligation to them as they need more time and economic resources to take care of their parents. For the living arrangements with children, as expected, we see significantly negative effects for the young children aged 0–3 and for the teenagers 12–15. There is no significant effect on SWB for having an adult child at home.

After subcategorizing the organization dummy variable, being a communist party member raises both happiness and life satisfaction significantly. Similarly, being a delegate in CPC or CPPCC is a strong signal of the elite status of the individual, and the models indicate that this status has a stronger impact on life satisfaction. While youth league membership is also a signal of privilege, the positive impact is smaller as this membership is only valid for the youth. Members of religious groups are both happier and more satisfied with lives than those not belonging to any religious group.

5. DISCUSSION

In this paper, we use the 2010 wave of CFPS to explore the relationship between social networks and SWB in the context of China. Our study contributes to the literature of social networks and SWB in China by providing richer measurements of kinship relationships, contacts with friends and relatives, as well as diversity and time spent in social activities for the full age span of the adult Chinese population. There are some limitations to our study to keep in mind.

One issue that limits this research, as it does for much of the social network literature, is that social networks themselves are choice variables and are therefore endogenous (Durlauf and Fafchamps, 2005). People can choose which networks they associate with and which ones they avoid and presumably do so based in part on their effect on their SWB. However, our data are cross-sectional and the central issue of reverse causality whereby those with better SWB find it easier to establish networks cannot conclusively be addressed with our data. This caveat is high priority for future research.

Secondly, despite the richness of our Chinese data, there are several concepts related to SWB that it does not contain. For example, measures of quality of social networks like quality of marriage and personal attributes and positive and negative behaviors of those in the network. Education and smoking behavior of relatives and friends are just two examples. Finally, measures of costs of forming and maintaining social networks such as distance would be quite valuable.

Overall, our analysis indicates that maintaining good social networks in China is associated with better SWB with the following main findings: First, people with larger social network measured by stronger kinship relationships, more friends, and more frequent contact with friends and relatives especially during special occasions in China such as the “Spring Festival” have higher SWB. These enhancements in SWB are larger when friends visit compared to relatives. As Spring Festival is the most important holiday in China, it is conventional for relatives to visit each other so that not visiting important relatives could be very inappropriate. Thus, visits of relatives may in part be motivated by obligation rather than from their own will. Since friends are established based on mutual respect, visits of friends tend to bring more happiness and life satisfaction.

Second, the type of family relationships when living together matters a great deal. Many Chinese couples live separately due to working in different cities, or taking care of children/grandchildren. Being married is better compared with remaining single or widowhood at least when young, but living together with one’s spouse is even more important to SWB especially for younger respondents than merely an identity of a husband/wife. Similarly, respondents older than age 45 who co-reside with a parent have lower levels of SWB most likely due to the financial and emotional stress of caring for a sick parent.

We also found different effects for living with children of different ages with the largest negative effects on SWB occurring for very young children (ages 0–3) and adolescents (ages 12–15). While welcoming a new baby is a joyful event, such enjoyment may be immediately taken over by the challenges in modern day China. Often a new child in China indicates necessary changes in living arrangements (may need a nanny, or the in-laws to live together) or in working status (the mother may have to stay at home), tighter relationships especially with in-laws, as well as bigger economic challenges (new baby creates more spending, mom at home decreasing income). All these changes can exert emotional pressure and decrease SWB. The age of 4–11 is relatively peaceful to the Chinese couple, as the child goes to preschool and primary school. The age of 12–15, however, may involve more conflicts between parents and teenagers during the adolescent years.

Third, individuals that both give and receive gifts have higher SWB as they are more socially integrated. This finding provides empirical support for the Chinese belief that “courtesy honors reciprocity.” If one is only a giver or receiver of gifts, it enhances SWB more if one is a giver reflecting the Chinese proverb that is better to give than receive.

Fourth, people who participate more actively in social activities tend to have higher SWB, and, at least in contemporary Chinese, culture diversity in the number of activities is more important than the total time spent in these activities. Engagements in social organizations also improve SWB, and in particular the role of Communist Party member and religious group improve both happiness and life satisfaction with similar magnitudes. Communist party membership in China is often a necessary condition to be a public servant or a key figure in state-owned enterprises and state-owned banks. Thus, communist party members often have more access to political and economic resources. Religious membership may assist individuals in dealing with the challenges of life especially in a rapidly developing and changing society such as China.

6. EXPLAINING THE AGE PROFILE IN SWB

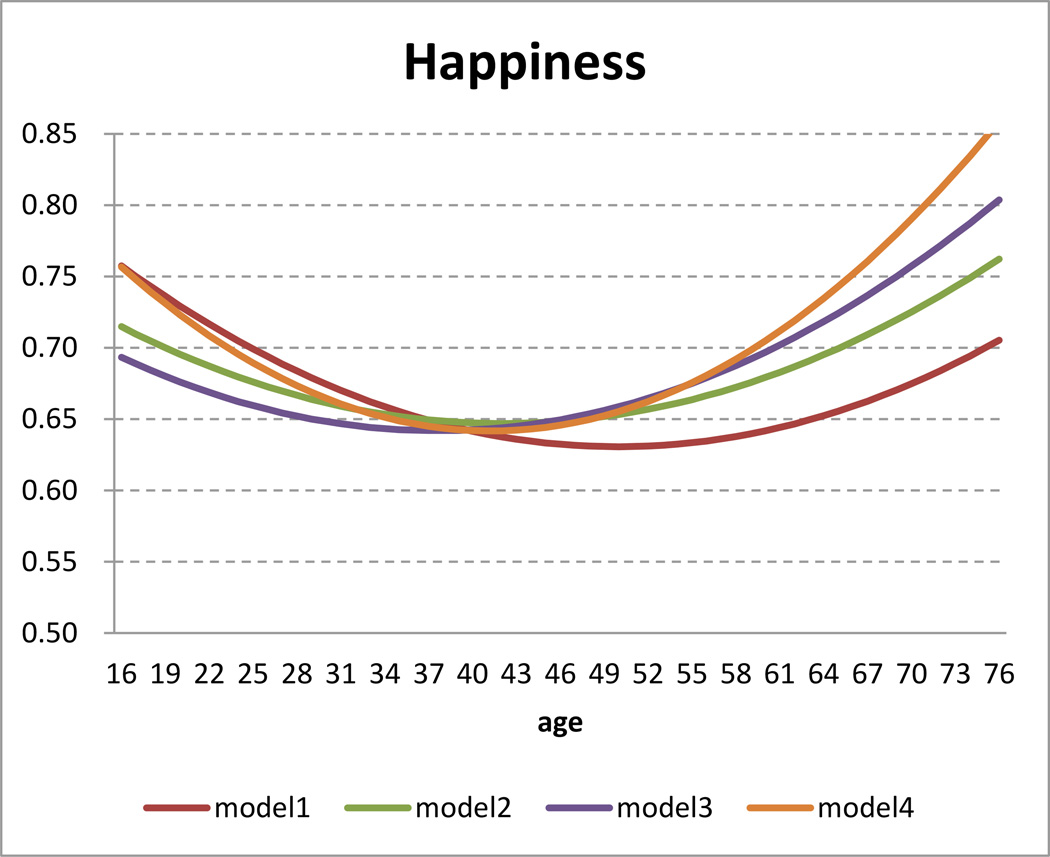

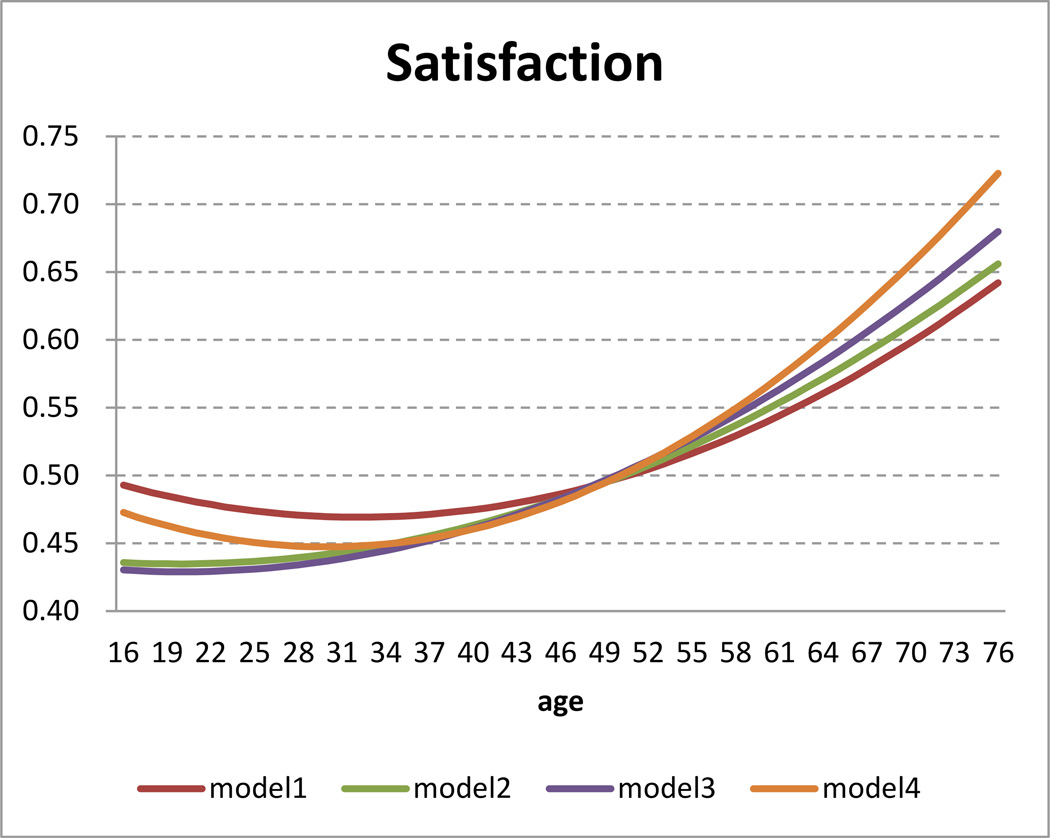

In this section we focus on what factors contribute to the U shape age relation to SWB in China. We do so for both the happiness measure (Figure 3.a) and the life satisfaction measure (Figure 3.b). Figure 3 addresses the age shape of SWB by performing simulations from four estimated models. Model 1 uses as explanatory variables only an age quadratic, gender, region and urbanism of residence so it essentially traces out the unadjusted age shape to SWB which as documented in Figure 3.a and 3.b indicates declining SWB before middle age and an even sharper rise in SWB in older ages in China. The U shape is far more pronounced for the hedonic happiness measure than for life satisfaction measure.

Figure 3. Simulated age patterns in happinesss sequentially adjusting for health, economic status, and social networks.

In Figures 3.A and 3.B, we show the U shape relationship between SWB and age. The vertical axis means the probability of feeling very happy/satisfied—the highest category in the 3-category measures of SWB, while the horizontal axis means the range of age while holding the other independent variables at the mean value.

From model 1 to model 4, the regression methods are all 3-category ordered probit models, but the independent variables are different. In all models, dummy variables for male, urban and East/Middle are controlled. In model 1, we only use age, age square and the constant term as independent variables. In model 2, we add healthstatus as additional independent variables based on model 1. In model 3, we add lnexp and highschool as additional independent variables based on model 2. In model 4, we add marriage and all the other social network variables as independent variables based on model 3.

Model 2 then traces out the implied age shape derived from a model that adds in our measure of health status. Since health status declines after middle age, removing this decline in health from the age shape results in an even sharper increase in SWB (and especially happiness) after middle age. The difference between the model 1 and model 2 graphs in Figure 3 is a useful visual measure of the contribution of good health status to SWB. The decline in health with age is one limiting factor limiting on what would have been an even sharper improvement in SWB in age especially for the health measure. To illustrate, compared to the early age forties, declining health reduces happiness by about 5 percentage points by age 65. Declining health produces a smaller reduction in the longer term life satisfaction measure by age 65.

In models 3 graphed in Figure 3, we add our economic variables—ln PCE and education—as dependent variables to the SWB simulation models. In addition to normal life-cycle reasons, ln PCE, our preferred measure of economic resources, falls rapidly with age due to the rapid economic growth that has taken place in China. Similarly, the rapid expansion in education across birth cohorts also implies a strong negative correlation of education with age… Since both factors—economic resources, education—improve SWB and decline with age the model 3 adjusted age profile in Figure 3 shows an even sharper increase in SWB at older ages. Thus, the positive cohort effects in terms of more education and economic resources have been operating to reduce the increase in SWB at older ages in China. Without those positive cohort effects, SWB would increase at an even more rapid rate at older ages in China. We find similar results when we add social network variables such as marriage to the model in Model 4. Since marriage rates are falling at older ages due to widowhood, holding constant marriage we would observe an even larger increase in SWB with age at older ages.

As explained here, most of the secular changes in recent decades in China improving health, education, and economic resources—actually served to diminish the sharp rise in SWB in China which would have been even steeper without those changes. Reasons for this are a worthy topic for future research but they are consistent with the view that older people have an increasing ability to self-regulate emotions, such as anger, and view their situations positively (Carstensen et al., 2003).

7. CONCLUSIONS

In this paper, we estimate strong associations of SWB, both happiness and life satisfaction, with social networks and health. There are other topics besides social networks and health with SWB in China that merit attention from the research community. Even though there are significant improvements in material living standards accompanying over 30 years of fast economic growth in China, Chinese people may not necessarily feel happy or satisfied if the society is experiencing increasing inequality, worsening natural environment, and expanding corruption. These challenges not only have a direct effect, but can also indirectly affect one’s subjective wellbeing through narrowing his/her social networks. Our study has found a strong association between subjective wellbeing and various measures of social networks for Chinese adults. How their subjective wellbeing is affected by the interactions of social network with these changing social forces in China can be investigated in the future.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by grants from the National Institute on Aging and Natural Science Foundation of China.

Appendix

APPENDIX TABLE 1.

Data Description

| Variable | Obs | Mean | Std. Dev. | Definition |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| happy3 | 19867 | 1.55 | 0.65 | score for happiness (1–3) |

| lifesat3 | 19867 | 1.33 | 0.73 | score for life satisfaction (1–3) |

| Married | 19866 | 0.84 | 0.37 | 1 = married and 0 otherwise |

| Family size | 19867 | 4.21 | 1.82 | total number of family members |

| Genealogy | 19789 | 0.24 | 0.43 | 1 = the family has a genealogy book and 0 otherwise |

| Number of friends relatives | 19712 | 9.45 | 11.35 | number of friends/relatives family during Spring Festival |

| Number of friends | 19786 | 5.76 | 6.54 | number of friends visiting family during Spring Festival |

| Number of relatives | 19742 | 3.71 | 6.93 | number of relatives visiting family during Spring Festival |

| ln value of gift given | 19867 | 5.40 | 3.22 | log net value of gifts family gave out last year |

| ln value of gift received | 19867 | 0.88 | 2.45 | log net value of gifts family received last year |

| Number of gifts given | 19867 | 30.57 | 179.95 | total number of gifts family gave out last year |

| Both give and receive | 19867 | 0.39 | 0.49 | 1 = both give and receive gifts and 0 otherwise |

| Give only | 19867 | 0.51 | 0.50 | 1 = only give gifts and 0 otherwise |

| Receive only | 19867 | 0.02 | 0.13 | 1 = only receive gifts and 0 otherwise |

| Contact with neighbors | 19867 | 5.96 | 11.84 | frequency of contact with neighbors |

| Contact friends & relatives | 19867 | 4.56 | 9.75 | frequency of contact with friends & relatives |

| Totact | 19841 | 4.49 | 2.56 | total types of social activities last month |

| Tottime | 19841 | 8.20 | 5.37 | total hours of activities/day last month |

| Organization | 19867 | 0.24 | 0.43 | whether you take part in one of registered organizations |

| Communist | 19867 | 0.08 | 0.27 | 1 = communist party member and 0 otherwise |

| Religion | 19867 | 0.01 | 0.10 | 1 = religious group member and 0 otherwise |

| Youth league | 19867 | 0.13 | 0.34 | 1 = China Youth League member and 0 otherwise |

| CPPCC | 19867 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 1 = County or higher level People’s Congress or Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference member |

| All other groups | 19867 | 0.04 | 0.20 | 1 = all other registered organizations and 0 otherwise |

| Have Job | 19133 | 0.52 | 0.50 | 1= have a job |

| In school | 19867 | 0.01 | 0.07 | 1= in achool |

| ln PCE | 19867 | 8.41 | 1.02 | log expenditure per capita |

| Age | 19867 | 46.41 | 15.40 | age |

| Male | 19867 | 0.49 | 0.50 | 1 = male and 0 = female |

| High school | 19861 | 0.48 | 0.50 | 1 = junior high school and above and 0 otherwise |

| Health status good | 19866 | 0.47 | 0.50 | 1 = health status good and above and 0 otherwise |

| Urban | 19867 | 0.48 | 0.50 | 1 = urban residence and 0 =rural residence |

| East region | 19867 | 0.38 | 0.48 | 1 = east region and 0 otherwise |

| Middle region | 19867 | 0.37 | 0.48 | 1 = middle region and 0 otherwise |

| Living with spouse | 19867 | 0.83 | 0.38 | 1 = living with spouse and 0 otherwise |

| Living with parents | 19867 | 0.19 | 0.39 | 1 = living with parents and 0 otherwise |

| Living with kid 0–3 | 19867 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 1 = living with children aged 0–3 and 0 otherwise |

| Living with kid 4–11 | 19867 | 0.19 | 0.19 | 1 = living with children aged 4–11 and 0 otherwise |

| Living with kid- 12–15 | 19867 | 0.14 | 0.14 | 1 = living with children aged 12–15 and 0 otherwise |

| Living with kid 16+ | 19867 | 0.45 | 0.50 | 1 = living with children aged 16+ and 0 otherwise |

Footnotes

A complete genealogy book consists of the genealogy name, explanatory notes, origin of surname, genealogy chart, biography, ancestral temple, tomb, rules and standards, the bestowal from the emperor or the royal court, pictures of ancestors, literature of family members, and name of the editor.

These two variables were constructed based on answers from two questions: 1. Last month, did your family interact with neighbors/friends in the following ways: (1) having dinner together, (2) gave food or other gifts, (3) providing help, (4) visits, (5) chatting (5) others. 2. Last month, how frequently did you interact with your neighbors/friends? (1) almost every day, (2) two to three times per week, (3) two to three times per month, (4) once every month. We transform these frequencies to approximate days in last month, that is, (1)=30, (2)=10, (3)=2.5, (4)=1. Then we add transformed frequencies for each interaction type to get an aggregate measurement of interaction frequency with friends/neighbors.

This grouping had no substantive effect on the main conclusions of the paper. We have also tried the specification that groups 1 and 2 only, and kept 3, 4, and 5 as separate groups. This four-group regression provides similar results to the three-group specifications.

To normalize the intercept, we define age in our analysis as age minus 20.

As suggested by a referee, we have considered depression as a related measure to SWB and evaluated the impacts of SN on depression. We find that marriage, number of friends, and the net-received amount have positive impact on relieving depression symptom, no matter whether depression is measured by the total score of all answers to the 6 CESD depression questions, or is treated as a dummy variable indicating whether the total score is higher than the median or not. These findings are consistent with the role of SN on happiness and life satisfaction, but the magnitudes and significance of variables are somewhat weaker perhaps because depression is more related to the health domain. Similarly Cao et al. (2015) examined social capital’s effect on depression of the older adults (aged over 60 years old) from urban China. They found that trust, reciprocity, and social network were significantly associated with depression, while social participation is not correlated with depression. The mediating effect of social support on the influence of social capital on depression is significant.

REFERENCES

- Acock AC, Hurlbert JS. Social networks, marital status, and well-being. Soc Networks. 1990;15:309–334. [Google Scholar]

- Bian Y, Zhang L, Yang J, Guo X, Lei M. Subjective well-being of Chinese people: A multifaceted view. Social Indic Res. 2015;121:75–92. [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen LL, Fung HH, Charles ST. Socioemotional selectivity theory and the regulation of emotion in the second half of life. Motiv Emotion. 2003;27(2):103–123. [Google Scholar]

- Cao W, Li L, Zhou X, Zhou C. Social capital and depression: evidence from urban elderly in China. Aging Ment Health. 2015;19(5):418–429. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2014.948805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan YK, Lee R. Network size, social support and happiness in later life: A comparative study of Beijing and Hong Kong. J Happiness Stud. 2006;7(1):87–112. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng ST, Lee CK, Chan AC, Leung EM, Lee JJ. Social network types and subjective well-being in Chinese older adults. J Gerontol B-Psychol. 2009;64(6):713–722. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbp075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chappell N, Badger M. Social isolation and well-being. J Gerontol B-Psychol. 1989;44(5):169–176. doi: 10.1093/geronj/44.5.s169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornwell EY, Waite LJ. Social disconnectedness, perceived isolation, and health among older adults. J Health Soc Behav. 2009;50(1):31–48. doi: 10.1177/002214650905000103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummins RA, Nistico H. Maintaining life satisfaction: The role of positive cognitive bias. J Happiness Stud. 2002;3(1):37–69. [Google Scholar]

- Cummins RA, Eckersley R, Pallant J, Van Vugt J, Misajon R. Developing a national index of subjective wellbeing: The Australian Unity Wellbeing Index. Soc Indic Res. 2003;64(2):159–190. [Google Scholar]

- Diener E, Ng W, Harter J, Arora R. Wealth and happiness across the world: Material prosperity predicts life evaluation, whereas psychosocial prosperity predicts positive feeling. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2010;99(1):52–61. doi: 10.1037/a0018066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durlauf SN, Fafchamps M. Social Capital. In: Phillipe A, Steven ND, editors. Handbook of Economic Growth. Elsevier; 2005. pp. 1639–1699. [Google Scholar]

- Easterlin RA. Will raising the incomes of all increase the happiness of all? J Economic Behav Organ. 1995;27(1):35–47. [Google Scholar]

- Easterlin RA. Feeding the illusion of growth and happiness: A reply to Hagerty and Veenhoven. Social Indic Res. 2005;74(3):429–443. [Google Scholar]

- Easterlin RA, Morgan R, Switek M, Wang F. China’s life satisfaction, 1990–2010. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(25):9775–9780. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1205672109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray A. The social capital of older people. Ageing Soc. 2009;29(1):5–31. [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y, Yao Y. The lineage networks and the migration of the labor forces. Manage World. 2013;3:69–81. [Google Scholar]

- Ha JH. The effects of positive and negative support from children on widowed older adults’ psychological adjustment: a longitudinal analysis. Gerontologist. 2010;50(4):471–481. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnp163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X, Western M. Social networks and subjective well-being: From theory to research design. TASA 2013 Conference Proceedings: Reflections, Intersections and Aspirations; Monash University, Melbourne. Annual Conference of The Australian Sociological Association; 2013. Nov 25–28, [Google Scholar]

- Johnson CL, Troll L. Family functioning in late late life. J Gerontol B-Psychol. 1992;47(2):66–72. doi: 10.1093/geronj/47.2.s66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman D, Deaton A. High income improves evaluation of life but not emotional well-being. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(38):16489–16493. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1011492107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuan HC, Lau SK. Traditional orientations and political participation in three Chinese societies. J Contemp China. 2002;11(31):297–318. [Google Scholar]

- Lin N. Social networks and status attainment. Ann Rev Sociol. 1999;25:467–487. [Google Scholar]

- Litwin H. Social networks and well-being: A comparison of older people in Mediterranean and non-Mediterranean countries. J Gerontol B-Psychol. 2010;65(5):599–608. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbp104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litwin H, Stoeckel KJ. Social networks and subjective wellbeing among older Europeans: does age make a difference? Ageing Soc. 2012;33:1263–1281. [Google Scholar]

- Ng ACY, Phillips DR, Lee WKM. Persistence and challenges to filial piety and informal support of older persons in a modern Chinese society: A case study in Tuen Mun, Hong Kong. J Aging Stud. 2002;16(2):135–153. [Google Scholar]

- Perry CM, Johnson CL. Families and support networks among African American oldest-old. Int J Aging Hum Dev. 1994;38(1):41–50. doi: 10.2190/UQKB-EL57-TN8R-3W1A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverstein M, Parker MG. Leisure activities and quality of life among the oldest old in Sweden. Res Aging. 2002;24(5):528–547. [Google Scholar]

- Stone A, Schwartz J, Broderick J, Deaton A. A snapshot of the age distribution of psychological well-being in the United States. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(22):9985–9990. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1003744107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss J, Thomas D. Human resources: empirical modeling of household and family decisions. In: Behrman JR, Srinivasan TN, editors. Handbook of Development Economics. 3A. Amsterdam: North Holland Press; 1995. Chapter 34. [Google Scholar]

- Udry C. Credit markets in Northern Nigeria: Credit as insurance in a rural economy. World Bank Econ Rev. 1990;4(3):251–269. [Google Scholar]

- Veenhoven R. Healthy happiness: Effects of happiness on physical health and the consequences for preventive health care. J Happiness Stud. 2008;9(3):449–469. [Google Scholar]

- Wang X. Subjective well-being associated with size of social network and social support of elderly. J Health Psychol, published on-line before print. 2014 Aug 7;:1–6. doi: 10.1177/1359105314544136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weng BK. Social network and subjective well-being of the elderly in Hong Kong. Asia Pac J Soc Work. 1998;8(2):5–15. [Google Scholar]

- Wong CK, Wong KY, Mok BH. Subjective well-being, societal condition and social policy-the case study of a rich Chinese society. Soc Indic Res. 2006;78(3):405–428. [Google Scholar]

- Wu J. How we chat, the most popular social network in China, cultivates wellbeing. Philadelphia, PA: Master’s Thesis, University of Pennsylvania; 2014. Available at http://repository.upenn.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1066&context=mapp_capstone. [Google Scholar]

- Xie Y. China Family Panel Studies 2010: User’s Manual. 2012 Available at http://www.isss.edu.cn/cfps/EN/Documentation/js/229.html.

- Xing Z. A study of the relationship between income and subjective well-being in China. Sociological Studies. 2011;1:196–221. [Google Scholar]

- Yip W, Subramanian SV, Mitchell AD, Lee DT, Wang J, Kawachi I. Does social capital enhance health and well-being? Evidence from rural China. Soc Sci Med. 2007;64(1):35–49. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]