Abstract

Background

The genetic basis involved in multiple sclerosis (MS) susceptibility was not completely revealed by genome-wide association studies. Part of it could lie in repetitive sequences, as those corresponding to human Endogenous Retroviruses (HERVs). Retrovirus-like particles were isolated from MS patients and the genome of the MS-associated retrovirus (MSRV) was the founder of the HERV-W family. We aimed to ascertain which chromosomal origin encodes the pathogenic ENV protein by genomic analysis of the HERV-W insertions.

Methods/results

In silico analyses allowed to uncover putative open reading frames containing the specific sequence previously reported for MSRV-like envelope (env) detection. Out of the 261 genomic insertions of HERV-W env, only 9 copies harbor the specific primers and probe featuring MSRV-like env. The copy from chromosome 20 was further studied considering its size, a truncated homologue of the functional HERV-W env sequence encoding syncytin. High Resolution Melting analysis of this sequence identified two single nucleotide polymorphisms, subsequently genotyped by Taqman chemistry in 668 MS patients and 678 healthy controls. No significant association of these polymorphisms with MS risk was evidenced. Transcriptional activity of this MSRV-like env copy was detected in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from patients and controls. RNA expression levels of chromosome 20-specific MSRV-like env did not show significant differences between MS patients and controls, neither were related to genotypes of the two mentioned polymorphisms.

Conclusions

The lack of association with MS risk of the identified polymorphisms together with the transcription results discard chromosome 20 as genomic origin of MSRV-like env.

Keywords: Human endogenous retrovirus HERV-W, MSRV, Multiple sclerosis, Genetic susceptibility

Highlights

-

•

The chr.20 HERV-W env copy encodes a truncated homologue of the functional syncytin.

-

•

Two single nucleotide polymorphisms were identified in this sequence by High Resolution Melting.

-

•

No association of these polymorphisms with MS susceptibility was evidenced.

-

•

RNA expression of the chr. 20 HERV-W env copy did not show association with MS risk.

-

•

The chr. 20 HERV-W env copy does not seem to be an origin of MSRV ENV protein.

1. Background

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic inflammatory and neurodegenerative disease of the central nervous system affecting young adults [1]. Its precise etiology is not currently ascertained, but the prevailing hypothesis accepts the trigger of poorly-defined environmental factors acting in genetically susceptible individuals. The genetic background of these patients has been thoroughly studied and genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have increased significantly the number of loci identified in MS predisposition [2], [3]. Nonetheless, the overall genetic load revealed by this robust approach does not seem to fully explain previous estimations based on epidemiologic studies [4]. Neither the analysis of rare coding-region variants in known risk genes for autoimmune diseases clarified where the missing heritability lies [5]. In parallel, research on environmental factors has often pointed to different virus putatively related with this condition [6].

Retrovirus-like particles were observed in cell cultures of MS patients [7] and the genome of the MS-associated retrovirus, MSRV, was the founder member of a human Endogenous Retrovirus family, HERV-W [8]. Some time ago the repetitive sequences within the human genome were considered “junk DNA”, but this issue has been widely debated [9], [10] and recently, the ENCODE project has also questioned this gene-centric view of the genome [11]. Only about 1–3% of the genome corresponds to protein-coding sequences, while over 40% of the human DNA sequence holds repeated elements, and the endogenous retroviruses qualify for 8% of the total [12]. Most HERVs are defective for replication by the acquisition of stop codons, frameshift mutations and deletions [13]. Even so, MSRV virions have been reported in plasma and cerebrospinal fluid from MS patients and were associated with MS pathogenesis [8], [14], [15], [16]. Moreover, potent immunopathogenic properties mediated by T cells have been described in vivo for MSRV retroviral particles from MS cultures [17] and the MSRV envelope (ENV) protein was claimed to be responsible for the observed damage [18], [19]. Additionally, a recent study demonstrated that the protein MSRV ENV can be used instead of a mycobacterial lysate to induce Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis (EAE) [20].

The HERV-W retrovirus family is inserted into hundreds of genomic positions [21]; approximately half of them have been reduced to solitary LTRs through evolution and most of the remaining copies have rendered defective. The complete MSRV genome is around 7700-nucleotide long, with RU5, gag, pol, env, and U3R regions [22]. One functional HERV-W env copy from chromosome 7 codes the physiological syncytin [23]. Mameli and collaborators discovered a 12-nucleotide insertion in the transmembrane moiety of the MSRV env gene, which was absent from the syncytin genetic copy and might enable its discrimination [24]. Based on this insertion, the authors confirmed the link between MS and MSRV and concluded that syncytin expression does not differ in PBMCs from MS patients and controls [24]. Since the integration site of the true MSRV is still unknown, the unique sequence that can be defined as MSRV env is the one detected in extracellular virus particles. Therefore, all the HERV-W env DNA sequences with the features of the virionic MSRV env (i.e. the 12 bp insertion) must be defined as “MSRV-like” envs.

A yet unresolved issue is the genomic origin of the MSRV ENV protein. The insertion in chromosome X which contains a shortened version of the env gene has been regarded as a good candidate, given that this env sequence would encode a truncated syncytin-like protein of 475 amino acids [25]. In fact, a polymorphism described in that chromosome X copy was found associated with MS predisposition and with differential expression of MSRV [26]. In the present work, we aimed to further explore the chromosomal origin of the HERV-W ENV involved in MS pathogenesis, as the origin found in chromosome X is not necessarily the only one. GWAS do not analyze repetitive sequences from the genome in their search for susceptibility factors, therefore we hypothesized that part of the yet-undiscovered heritability could reside in these repetitive sequences.

2. Methods

2.1. Patients and controls

The Spanish case–control study included a total of 668 MS patients (64% females) and 678 healthy controls (57% females), with mean ages of 40 ± 9y and 41 ± 17y, respectively. All Caucasian participants were recruited from a single center, Hospital Clínico San Carlos, Madrid. MS diagnosis was established according to McDonald's criteria [27]. MS patients [age at onset (mean ± SD): 26 ± 9y] were classified in relapsing remitting (81%), primary progressive (9%) and secondary progressive (10%). None of the control subjects reported first or second degree relatives with any immune-mediated disease. All subjects were recruited after written informed consent and the Ethics Committee from Hospital Clínico San Carlos approved this study. All research was conducted according to the principles expressed in the Declaration of Helsinki.

2.2. In silico analysis

The MSRV-env sequence (AF331500) was aligned with the human genome assembly GRCh37.p5 using BLAST (http://www.ensembl.org). The query results were analyzed by pDRAW32 (developed by AcaClone, http://www.acaclone.com) to identify putative open reading frames (ORFs) containing the specific primers and probe reported for MSRV env RNA detection [24]. Then, sequences were compared using a multiple sequence alignment tool (www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalw2/) in order to find differential sequences for each insertion.

2.3. Expression analysis

RNA was extracted from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from fresh blood by centrifugation in CPT tubes (Becton Dickinson), using the Qiamp RNA Blood Mini kit (Qiagen). After DNAse treatment, RNA sample volumes adjusted to 10 ng/μl were retrotranscribed using First Strand cDNA Synthesis kit (Roche Diagnostics, S.L. Barcelona, Spain) with OligodT primers. Relative expression of MSRV env was measured by the 2e− ΔΔCt method. In short, quantitative real time PCR of the cDNA used a probe (CGCTCTAACTGCTTCCTGCT) and primers (forward: TATTGGGGAGGTGGCTGAT; reverse: GCTACAAATCATTCTTCAAATGGA) designed using PRIMER3 v4.0 software (http://frodo.wi.mit.edu/) for MSRV-like env derived from chromosome 20, and Glucuronidase-beta as housekeeping gene (HKG, GUS-B assay from Applied Biosystems). Each amplification included samples with their no-RT controls to detect possible genomic DNA contamination. Assays for the detection of GUS-B and chromosome 20 HERV-W env were considered acceptable when: 1) the Ct for the HKG was lower than the Mean + 2 ∗ S.D. of all samples; 2) no amplification was detected in the no-RT control; and 3) duplicates of each sample presented less than 2% of variability on Ct basis.

2.4. High Resolution Melting (HRM) analysis of MSRV-like env locus in chromosome 20 and genotyping

A PCR preparatory step was conducted for this chromosomal region (for primers and PCR amplification conditions see Supplementary Table 1). The PCR product containing the MSRV-env region of chromosome 20 was diluted 1/80 on sterile water, and then used as template to perform HRM analysis with a set of 12 pairs of primers that were designed using PRIMER3 v4.0 software [28]. Melting curves were discriminated in a 7900HT Fast Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA), according to the manufacturer's recommendations. When a different pattern of melting curve was suggestive of the existence of a potential mutation or single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP), the sample was diluted 1/20 on sterile water and sequenced using BigDye Cycle sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems). Any variant confirmed by sequencing was then genotyped by TaqMan technology in a 7900HT Fast Real-Time PCR system, under conditions recommended by the manufacturer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA).

2.5. Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 15.0. Linkage disequilibrium values (D′) and Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium were tested with Haploview 4.0 software. Chi-Square test was used to compare allele and genotype frequencies. Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare MSRV-like env relative expression between two groups. Statistically significant differences were considered when the p-value was lower than 0.05.

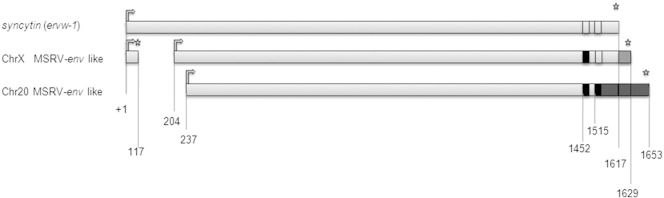

3. Results

In order to explore the genomic insertions of HERV-W env that match with the published MSRV env sequence (AF331500), homologies were searched in the human genome assembly GRCh37.p5 using BLAST (see Methods). The overall 261 sequences resulting from this query were analyzed by pDRAW32 to identify putative ORFs harboring the specific probe and primers reported for MSRV-like env RNA detection [24]. Only 9 out of the 261 sequences met these criteria and were selected for further analyses (Supplementary Fig. 1). From these genomic insertions of MSRV-like env, the two of them with ORFs around 10% shorter than the physiological syncytin (1617 bp) were: one located in chromosome X (1425 bp) and the other in chromosome 20 with 1416 bp (Fig. 1). The region of chromosome X which would encode a truncated syncytin protein has been previously studied [26] and in the present work we focused on the other plausible candidate in chromosome 20 (for protein alignments see Supplementary Fig. 2).

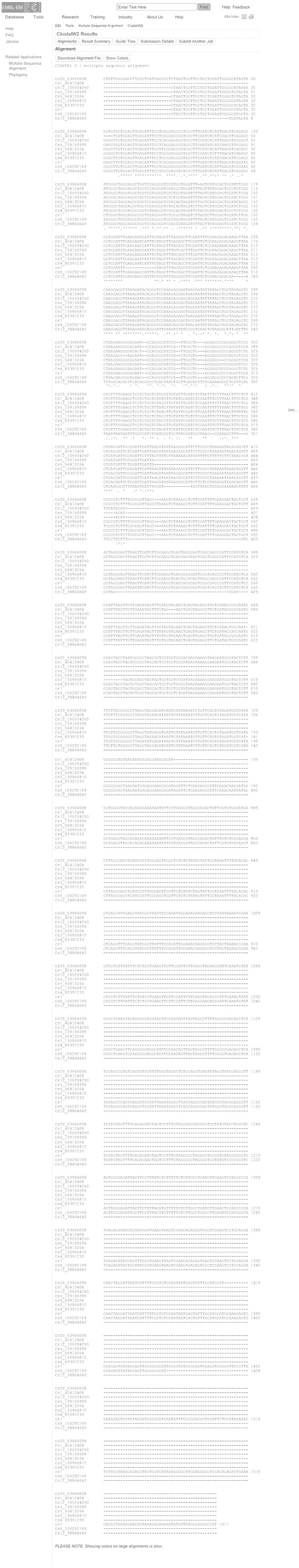

Supplementary Fig. 1.

Comparison of sequences of the nine genomic insertions coding MSRV-like env. Homologous sequences of MSRV env (AF331500) from human genome assembly GRCh37.p5 presenting ORFs harboring the specific primers and probe for MSRV-like env RNA detection.

Fig. 1.

Scheme comparing the HERV-W env ORFs from chromosome 7 (syncytin), chromosome X and chromosome 20. Arrows represent transcript origins and asterisks depict stop codons. Black boxes at 1452 nt and at 1515 nt indicate the 12 bp insertion to identify MSRV-like env. Empty boxes: 12 bp deletion. Light and dark gray sequences indicate non homologous sequences compared with syncytin.

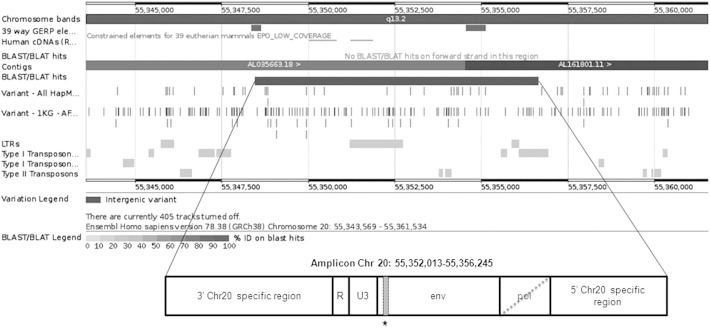

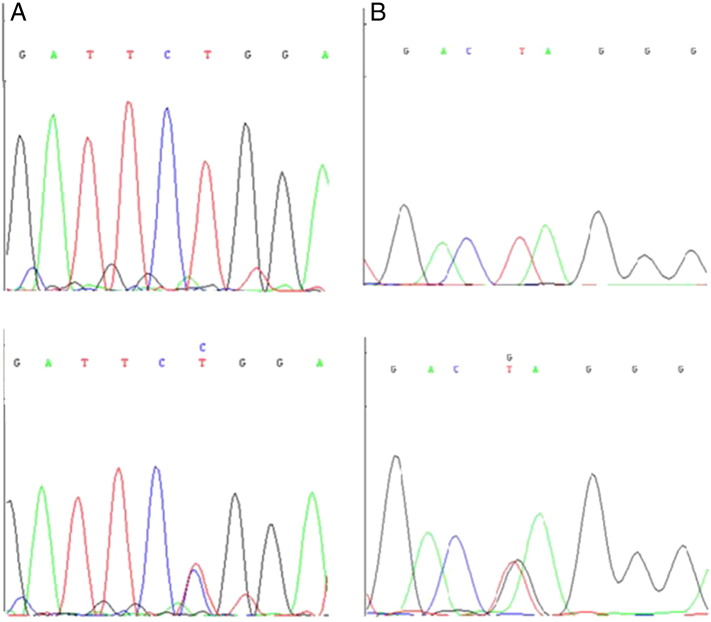

A preparative PCR amplification step from genomic DNA was conducted to isolate the specific MSRV-like env copy in chromosome 20 (Fig. 2), yielding a 4232 bp product used as template to perform HRM analysis in overlapping amplicons (for primers used and PCR conditions see Supplementary Table 1). Whenever a potential variant was detected in an initial screening of 100 samples, it was validated by sequencing and then analyzed by TaqMan technology in the overall 668 MS patients and 678 healthy controls. Two SNPs were identified following this procedure: T/C and T/G changes at positions 221 and 285 from the beginning of the amplification product (D′ = 35%, NCBI_ss# SNP1: 974293065 and SNP2: 974293066) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

The HERV-W insertion in chromosome 20. The insertion includes a truncated pol gene, an env gene with 88% homology to MSRV env and RU3 regions.

Fig. 3.

Two single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), T/C and T/G changes (NCBI_ss# SNP1: 974293065 and SNP2: 974293066), identified within the HERV-W insertion in chromosome 20.

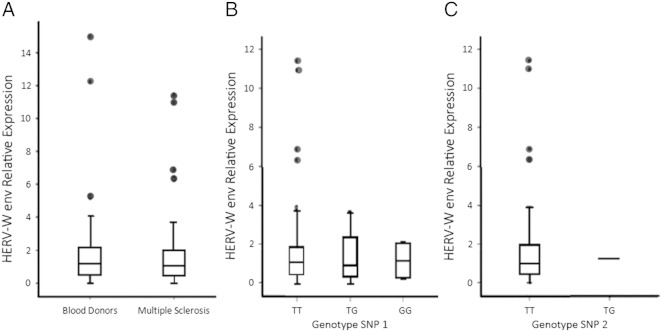

Genotyping success was over 95% for both patient and control cohorts and no departure from Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium was observed. However, no significant differences were found in the allelic or genotypic frequencies between MS patients and ethnically matched controls (χ2 test: p > 0.05, Table 1). Moreover, no significant associations (Mann–Whitney U test: p > 0.05) were found between alleles or genotypes of these SNPs and the RNA expression of MSRV env specifically derived from the chromosome 20 copy (Fig. 4).

Table 1.

Allelic and genotypic frequencies of both SNPs identified in the HERV-W copy of chromosome 20 in MS patients and controls.

| SNP1 | MS |

Controls |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |

| TT | 495 | 75 | 496 | 73 |

| TC | 153 | 23 | 168 | 25 |

| CC | 14 | 2 | 14 | 2 |

| T | 1143 | 86 | 1160 | 86 |

| C | 181 | 14 | 196 | 14 |

| SNP2 | MS | Controls | ||

| n | % | n | % | |

| TT | 652 | 99 | 652 | 98 |

| TG | 9 | 1 | 15 | 2 |

| GG | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| GG | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| G | 9 | 1 | 15 | 1 |

Fig. 4.

Relative expression of HERV-W env copy on chromosome 20 in 52 MS patients and 53 healthy blood donors (A) and stratified by genotype of the identified SNPs (B and C). Lines inside the boxes represent medians, whiskers represent standard deviations.

4. Discussion

In the present work, we aimed to shed some light on the genomic origin of the reported MSRV ENV protein previously identified as MS pathogenic co-factor. Specifically, we pursued to elucidate the putative role in MS risk of the insertion of MSRV-like env in chromosome 20 as one of the plausible candidates by size, together with the insertion in chromosome X already studied by our group [26]. Both chromosomal origins showed similar lengths of their respective ORFs, 10% shorter than the one measured for syncytin [29] and could putatively originate functional proteins. The ENV protein has been recently evidenced within post-mortem MS brain lesions [15], [30], [31], [32]. MSRV ENV induces human monocytes to produce proinflammatory cytokines through engagement of CD14 and TLR4 [19]. Kremer and collaborators demonstrated that the ENV protein is present in close proximity to TLR4-expressing oligodendroglial precursor cells adjacent to MS lesions [33]. In addition, MSRV ENV triggers a maturation process in human dendritic cells driving a Th1-like differentiation [19].

We recently reported that the MSRV-like env copy number is increased in PBMCs of MS patients, as an elevated MSRV-like env load was observed in MS patients compared to controls (p = 4.15 e-7) [34]. Moreover, in our cohort the transcription levels of MSRV-like env were higher in MS patients than in controls (Mann–Whitney U test: p = 0.004) [26], consistent with previous findings [24], [35]. Nonetheless, knowledge is still lacking about which chromosomal location(s) harboring specific retroviral copy(ies) originate(s) these induced levels of transcription. Once the RNA expression in PBMCs was validated (data not shown), we analyzed the insertions encoding modified envelope proteins: those derived from chromosomes X26 and 20. It has been demonstrated that MSRV-like env expression in brain macrophages within MS lesions is consistent with the observed expression in MS PBMCs, supporting the rationale for its ex-vivo detection in peripheral blood [30]. Nonetheless, our findings regarding the transcriptionally active long ORF derived from chromosome 20 dismiss this copy as a predominant origin of the MSRV pathogenic effect.

Previous results of GWAS in MS demonstrated associations with three loci within chromosome 20 including the following genes: CD40, TNFRSF6B and CYP24A1 [2], the latter at 1 Mb of the HERV-W insert studied in the present work. Considering that repetitive sequences of the genome have not been explored in the GWAS, this seemed an adequate analysis to advance in the unresolved issue of the missing heritability of this complex disease [4]. Moreover, one of the proposed co-factors repeatedly involved in the pathogenesis of MS is the Epstein–Barr virus, which was reported to activate in vitro the HERV-W family of human endogenous retroviruses [36]. The specific PCR amplification of the genomic region of chromosome 20 including the MSRV-like env sequence and subsequent HRM analysis led to the identification of two polymorphisms within this repetitive insertion. However, the performed case–control study did not detect significant differences in allelic or genotypic frequencies for these SNPs. Therefore, the results obtained in this study do not encourage further investigation of this MSRV-like env insertion as responsible of part of the genetic risk in MS patients. Despite the mentioned similar size of the two MSRV-like env copies from chromosomes 20 and X, apparent differences have been found between them. One polymorphism identified in chr. X, rs6622139*T, was associated with higher MSRV-like env expression (Mann–Whitney U test: p = 0.003), while the two polymorphisms found in chromosome 20 did not show evidence of association with chromosome 20-specific RNA expression levels. Additionally, rs6622139 was associated in women with MS susceptibility and severity [26]. These results point to the insertion in chromosome X and not the one in chromosome 20 as involved in the origin of MSRV ENV.

Suggestive of its potential pathogenic activity, significant decreases in seroreactivities to HERV-W envelope antigens, closely linked to efficacy of interferon-beta therapy were previously demonstrated [37] and recently, it has been reported that after one year therapy, natalizumab inhibits the plasma-membrane levels of the ENV protein in MS patients [38]. The challenge is now to turn the increasing knowledge in HERV-W to the clinical setting, as it has proven helpful in predicting therapy outcomes [34].

The following are the supplementary data related to this article.

Primers used for the specific amplification of HERV-W env from chromosome 20 and for High Resolution Melting (HRM) analysis and ulterior sequencing of the overlapping amplicons.

Protein alignments of ENV encoded from chromosome 7 (syncytin), chromosome X and chromosome 20. ChrX MSRV-like ENV ORF1 and ORF2: short and long fragments of the canonical ENV sequence from chromosome X.

Transparency Document

Transparency document.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by: Instituto de Salud Carlos III-Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional (Feder), Fondo de Investigaciones Sanitarias FIS (PI13/0879) and Fundaciones: Genzyme (to R.A-L.); Lair (to R. A.) and Mutua Madrileña (to R. A-L.) R.A-L. is recipient of a research contract of the Instituto de Salud Carlos III- Feder (CP07/00273). M.A.G-M. is recipient of a technician contract from the “REEM: Red Española de Esclerosis Múltiple” (RETICS-REEM RD12/0032/009; www.reem.es). B.H. is recipient of a PhD scholarship from the “Fondo de Investigaciones Sanitarias” (FI11/00560), J.V. is recipient of a contract from the “Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad” (PTA2011-6137-1) and E.U. works for the FIB-Hospital Clínico San Carlos- IdISSC. The authors do not disclose any conflict of interest.

Footnotes

The Transparency document associated with this article can be found, in the online version.

References

- 1.Frohman E.M. Multiple sclerosis—the plaque and its pathogenesis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006;354:942–955. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra052130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.IMSGC Genetic risk and a primary role for cell-mediated immune mechanisms in multiple sclerosis. Nature. 2011;476:214–219. doi: 10.1038/nature10251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.IMSGC Analysis of immune-related loci identifies 48 new susceptibility variants for multiple sclerosis. Nat. Genet. 2013;45:1353–1360. doi: 10.1038/ng.2770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Manolio T.A. Finding the missing heritability of complex diseases. Nature. 2009;461:747–753. doi: 10.1038/nature08494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hunt K.A. Negligible impact of rare autoimmune-locus coding-region variants on missing heritability. Nature. 2013;498:232–235. doi: 10.1038/nature12170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Handel A.E. Genetic and environmental factors and the distribution of multiple sclerosis in Europe. Eur. J. Neurol. 2010;17:1210–1214. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2010.03003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Perron H. Isolation of retrovirus from patients with multiple sclerosis. Lancet. 1991;337:862–863. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)92579-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Perron H. Molecular identification of a novel retrovirus repeatedly isolated from patients with multiple sclerosis. The Collaborative Research Group on Multiple Sclerosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1997;94:7583–7588. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.14.7583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nelson P.N. Human endogenous retroviruses: transposable elements with potential? Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2004;138:1–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2004.02592.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dolei A. Endogenous retroviruses and human disease. Expert. Rev. Clin. Immunol. 2006;2:149–167. doi: 10.1586/1744666X.2.1.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bernstein B.E. An integrated encyclopedia of DNA elements in the human genome. Nature. 2012;489:57–74. doi: 10.1038/nature11247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ryan F.P. Human endogenous retroviruses in multiple sclerosis: potential for novel neuro-pharmacological research. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2011;9:360–369. doi: 10.2174/157015911795596568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Parseval N. Comprehensive search for intra- and inter-specific sequence polymorphisms among coding envelope genes of retroviral origin found in the human genome: genes and pseudogenes. BMC Genomics. 2005;6:117. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-6-117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dolei A. Multiple sclerosis-associated retrovirus (MSRV) in Sardinian MS patients. Neurology. 2002;58:471–473. doi: 10.1212/wnl.58.3.471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mameli G. Brains and peripheral blood mononuclear cells of multiple sclerosis (MS) patients hyperexpress MS-associated retrovirus/HERV-W endogenous retrovirus, but not Human herpesvirus 6. J. Gen. Virol. 2007;88:264–274. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.81890-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sotgiu S. Multiple sclerosis-associated retrovirus and progressive disability of multiple sclerosis. Mult. Scler. 2010;16:1248–1251. doi: 10.1177/1352458510376956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Firouzi R. Multiple sclerosis-associated retrovirus particles cause T lymphocyte-dependent death with brain hemorrhage in humanized SCID mice model. J. Neurovirol. 2003;9:79–93. doi: 10.1080/13550280390173328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Perron H. Multiple sclerosis retrovirus particles and recombinant envelope trigger an abnormal immune response in vitro, by inducing polyclonal Vbeta16 T-lymphocyte activation. Virology. 2001;287:321–332. doi: 10.1006/viro.2001.1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rolland A. The envelope protein of a human endogenous retrovirus-W family activates innate immunity through CD14/TLR4 and promotes Th1-like responses. J. Immunol. 2006;176:7636–7644. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.12.7636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Perron H. Human endogenous retrovirus protein activates innate immunity and promotes experimental allergic encephalomyelitis in mice. PLoS One. 2013;8:e80128. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pavlicek A. Processed pseudogenes of human endogenous retroviruses generated by LINEs: their integration, stability, and distribution. Genome Res. 2002;12:391–399. doi: 10.1101/gr.216902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Komurian-Pradel F. Molecular cloning and characterization of MSRV-related sequences associated with retrovirus-like particles. Virology. 1999;260:1–9. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.9792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Knerr I. Endogenous retroviral syncytin: compilation of experimental research on syncytin and its possible role in normal and disturbed human placentogenesis. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 2004;10:581–588. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gah070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mameli G. Novel reliable real-time PCR for differential detection of MSRVenv and syncytin-1 in RNA and DNA from patients with multiple sclerosis. J. Virol. Methods. 2009;161:98–106. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2009.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roebke C. An N-terminally truncated envelope protein encoded by a human endogenous retrovirus W locus on chromosome Xq22.3. Retrovirology. 2010;7:69. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-7-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Garcia-Montojo M. HERV-W polymorphism in chromosome X is associated with multiple sclerosis risk and with differential expression of MSRV. Retrovirology. 2014;11:2. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-11-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McDonald W.I. Recommended diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: guidelines from the International Panel on the diagnosis of multiple sclerosis. Ann. Neurol. 2001;50:121–127. doi: 10.1002/ana.1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rozen S. Primer3 on the WWW for general users and for biologist programmers. Methods Mol. Biol. 2000;132:365–386. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-192-2:365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mi S. Syncytin is a captive retroviral envelope protein involved in human placental morphogenesis. Nature. 2000;403:785–789. doi: 10.1038/35001608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Perron H. Human endogenous retrovirus type W envelope expression in blood and brain cells provides new insights into multiple sclerosis disease. Mult. Scler. 2012;18:1721–1736. doi: 10.1177/1352458512441381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Antony J.M. Human endogenous retrovirus glycoprotein-mediated induction of redox reactants causes oligodendrocyte death and demyelination. Nat. Neurosci. 2004;7:1088–1095. doi: 10.1038/nn1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Perron H. Human endogenous retrovirus (HERV)-W ENV and GAG proteins: physiological expression in human brain and pathophysiological modulation in multiple sclerosis lesions. J. Neurovirol. 2005;11:23–33. doi: 10.1080/13550280590901741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kremer D. Human endogenous retrovirus type W envelope protein inhibits oligodendroglial precursor cell differentiation. Ann. Neurol. 2013;74:721–732. doi: 10.1002/ana.23970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Garcia-Montojo M. The DNA copy number of human endogenous retrovirus-W (MSRV-type) is increased in multiple sclerosis patients and is influenced by gender and disease severity. PLoS One. 2013;8:e53623. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zawada M. MSRV pol sequence copy number as a potential marker of multiple sclerosis. Pol. J. Pharmacol. 2003;55:869–875. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mameli G. Expression and activation by Epstein Barr virus of human endogenous retroviruses-W in blood cells and astrocytes: inference for multiple sclerosis. PLoS One. 2012;7:e44991. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Petersen T. Effects of interferon-beta therapy on innate and adaptive immune responses to the human endogenous retroviruses HERV-H and HERV-W, cytokine production, and the lectin complement activation pathway in multiple sclerosis. J. Neuroimmunol. 2009;215:108–116. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2009.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Arru G. Natalizumab inhibits the expression of human endogenous retroviruses of the W family in multiple sclerosis patients: a longitudinal cohort study. Mult. Scler. 2013;20:174–182. doi: 10.1177/1352458513494957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Primers used for the specific amplification of HERV-W env from chromosome 20 and for High Resolution Melting (HRM) analysis and ulterior sequencing of the overlapping amplicons.

Protein alignments of ENV encoded from chromosome 7 (syncytin), chromosome X and chromosome 20. ChrX MSRV-like ENV ORF1 and ORF2: short and long fragments of the canonical ENV sequence from chromosome X.

Transparency document.