Abstract

A high-throughput radiometric assay was developed to characterize enzymatic hydrolysis of ghrelin and to track the peptide's fate in vivo. The assay is based on solvent partitioning of [3H]-octanoic acid liberated from [3H]-octanoyl ghrelin during enzymatic hydrolysis. This simple and cost-effective method facilitates kinetic analysis of ghrelin hydrolase activity of native and mutated butyrylcholinesterases or carboxylesterases from multiple species. In addition, the assay's high sensitivity facilitates ready evaluation of ghrelin's pharmacokinetics and tissue distribution in mice after i.v. bolus administration of radiolabeled peptide.

Keywords: Butyrylcholinesterase, Ghrelin, Radiometric assay, Enzyme kinetics, Pharmacokinetics

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Ghrelin is a 28-amino acid peptide hormone with the unique feature of an n-octanoylated residue (serine-3). Among ghrelin's numerous and diverse physiological roles are, stimulated pituitary release of growth hormone [1, 2], increased food intake [3, 4], mediation of energy homeostasis [5, 6], and enhanced gastrointestinal motility [7, 8]. Ghrelin is also involved in psychological states linked to psychosocial stress [9, 10], mood [11, 12], and anxiety [13-15]. In vivo, plasma and liver hydrolases convert ghrelin into “largely inactive” desacyl-ghrelin, by cleaving the octanoyl group required for interaction with its key target, the growth hormone secretagogue receptor [16].

Since ghrelin has broad physiological impact, there may be therapeutic potential in modulating its inactivation. As previously shown [17], one enzyme serving this role is butyrylcholinesterase (BChE; EC 3.1.1.8). While investigating mice that received BChE gene transfer for other purposes, we observed that, as BChE activity rose to levels 100-fold above normal, plasma ghrelin dropped toward zero. In contrast plasma ghrelin in BChE-null mice was consistently 50% higher than in wild type animals. These genetic and vector-driven effects had an unexpected impact on emotional behaviors. In particular, mice with high BChE and low ghrelin were markedly less aggressive than vector-naive and knockout animals, while mice with no BChE and high ghrelin exhibited an opposite phenotype [18].

To pursue these phenomena we sought efficient means of characterizing ghrelin substrate kinetics with BChE from multiple species and with various active-site mutations. Available methods included radioimmunoassay [19, 20], enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay [21], high-performance liquid chromatography [22], and mass spectrometry [23]. Most of these assays are both sensitive and reliable, but all are expensive and time consuming. To remedy these drawbacks we developed a new procedure using [3H]-ghrelin as a substrate. The requirements were: 1) a source of ghrelin with high specific radioactivity on the octanoyl moiety; 2) fast separation of octanoic acid from intact ghrelin; 3) adequate sensitivity and precision to track ghrelin hydrolysis at physiological (sub-nanomolar) concentrations; 4) high throughput (~200 samples/day); 5) small variation in replicate samples; 6) much lower cost per sample than with commercial kits. Below we describe the design and performance characteristics of this assay, and its application in examining ghrelin pharmacokinetics in multiple tissues of the mouse.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Radiometric assay of ghrelin de-acylation

Unless otherwise indicated all chemicals and reagents were obtain from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). The key substrate, [3H]-octanoyl-human ghrelin (~80 Ci/mmol) was custom synthesized by Quotient Bioresearch, Cardiff, UK. The assay was based on selective solvent-extraction of [3H]-octanoic acid released by ghrelin hydrolysis (Fig. 1). Before assay, the labeled substrate was diluted 25-fold in 0.02 N HCl and washed 3 times with 10-volume of pure toluene (EMD Chemicals, Inc., Gibbstown, NJ) to remove octanoic acid spontaneously released during storage. Purified human BChE was diluted in 10 mM Tris-acetate buffer, pH 7.4. Labeled substrate was mixed with calibrated amounts of unlabeled human ghrelin (Phoenix Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Burlingame, CA). Reactions were initiated with 100 nCi (0.0125 μM) of [3H]-octanoyl ghrelin and selected amounts of unlabeled ghrelin in a final volume of 100 μl. After 20 min incubation, reactions were stopped with 1 ml of 0.02 M HCl to neutralize the liberated [3H]-octanoic acid. This product was then selectively extracted by vigorous vortexing with 4 ml of toluene containing 16 mg of PPO (2,5-diphenyloxazole) and 0.2 mg of POPOP (1,4-Bis(5-ophenyl-2-oxazolyl)benzene). After centrifugation (3000g, 10 min), aliquots of the upper phase were transferred to a scintillation counter for quantitation of radiolabel, while total aqueous radioactivity in quality-control samples was determined in Bio-Safe II, RPI (Mount Prospect, IL).

Fig. 1.

Scheme of radiometric ghrelin hydrolysis assay. [3H]-octanoyl ghrelin is hydrolyzed into [3H]-octanoic acid and unlabeled desacyl-ghrelin by the enzyme BChE. A critical step separates liberated [3H]-octanoic acid from residual [3H]-octanoyl ghrelin. After acidification by HCl, neutralized octanoic acid partitions into the toluene phase, while [3H]-ghrelin remains in the aqueous phase and escapes detection.

2.2 Enzyme production and purification

Native BChE and mutated variants were purified from mouse serum collected after gene transfer of enzyme cDNA by adeno-associated viral vector (AAV 2/8, 1×1013 viral genomes delivered by tail-vein injection). After two weeks to reach maximal expression, the mice were euthanized by pentobarbital and blood was collected from the vena cava and heart. BChE protein was then enriched to ~ 90% purity by ammonium sulfate fractionation and separation on procainamide Sepharose affinity columns as previously described [24]. Certain experiments utilized >98% pure human BChE (O. Lockridge, Univ. Nebraska, Omaha, NE). Enzyme active sites were titrated with di-isopropyl fluorophosphate (DFP, Sigma) to determine final molar enzyme concentration as described previously [25].

2.3 Substrate kinetics

Optimum conditions for ghrelin hydrolysis were established by assays with human BChE at 23 °C or 37 °C in 10 mM Tris-acetate buffers ranging from pH 6 to pH 9. Substrate kinetics were tested with ghrelin concentrations from 0.025 to 25.6 μM, mixing unlabeled ghrelin with 0.0125 μM of [3H]-octanoyl ghrelin. To estimate Vmax, Km, and kcat, data obtained at 23 °C in three independent experiments were fitted to the basic Michaelis-Menten equation with GraphPad Prism (Version 6.05, GraphPad Software Inc, La Jolla, CA) with a weighting factor of 1/SD2.

2.4 Time-dependent ghrelin levels in blood and tissue samples

Adult male C57BL/6 mice were handled in accord with the Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory animals [26] and EU Directive 2010/63/EU in a facility accredited by the American Association for the Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care. Mice were pretreated with DFP (3mg/kg, i.p.) to inhibit cholinesterases and carboxylesterases as reports indicated that exogenous ghrelin is virtually eliminated after 10 min [27]. One hr later, mice were anesthetized by pentobarbital sodium (Vortech Pharmaceuticals, Ltd., Dearborn, MI, 50 mg/kg, i.p.), and [3H]-ghrelin (5 μCi) was injected i.v. along with varying amounts of unlabeled ghrelin (up to 30 μg/kg). Arterial blood was collected at 3, 6, 12, and 24 min in EDTA-treated tubes with protease inhibitors (1mM p-hydroxymercuribenzoic acid, Sigma-Aldrich; 1.5 μM aprotinin, Roche). Centrifuged plasma was mixed at once with 0.1 volume of 1 N HCl and stored at −80 °C. Mice were then quickly perfused with 80 ml of 0.9% NaCl containing esterase- and protease-inhibitors (100 μM DFP, 1mM p-hydroxymercuribenzoic acid, 1.5 μM aprotinin, and 25 μl/ml saturated NaF). Brain, liver, heart, kidney, spleen, stomach, lung, pancreas, intestine, epididymal fat, and quadriceps muscle were collected on dry ice, homogenized in cold 0.1 M HCl with 0.5 % Tween 20 and enzyme inhibitors as above, and centrifuged (13000g, 10 min, 4 °C). Supernatants were immediately assayed for ghrelin in terms of radiolabel remaining in the acidified aqueous phase after toluene extraction.

2.5 Separation of ghrelin fragments

To investigate ghrelin fragmentation by DFP-resistant proteases and peptidases, plasma samples from the in vivo time course study were dialyzed in FLOAT-A-LYZER bags with three different molecular cut-offs: 0.1 KD – 0.5 KD, 0.5 KD – 1.0 KD, and 3.5 – 5.0 KD (Spectrum Labs, Rancho Dominguez, CA) in PBS for 4 hr. Radioactivity remaining in the dialysis bags was determined as described above, while plasma ghrelin was measured by ghrelin EIA immunoassay (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI).

3. Results

3.1 Optimizing reaction condition

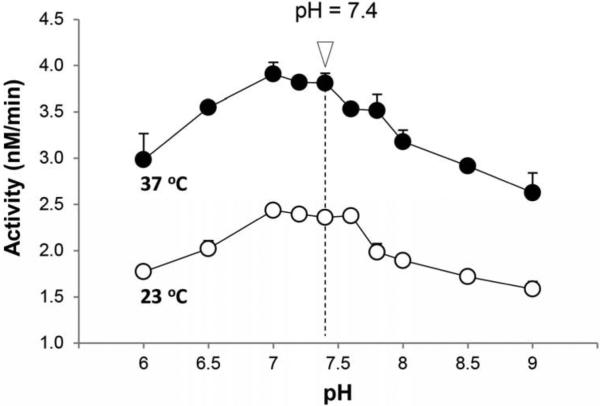

Ghrelin hydrolysis assays with human BChE generated a bell-shaped curve over the pH range 6 to 9 with optimal activity between pH 7 and 7.6 and a rate ~1.5 times faster at 37 °C than at 23 °C (Fig. 2). For convenience, further assays were conducted at 23 °C and pH 7.4, with a 20-min duration.

Fig. 2.

Effects of pH and temperature on BChE activity. Purified human BChE (5 nM) was assayed across a pH range of 6 – 9 in 10 mM Tris-acetate buffer. Substrate was 500 nM unlabeled ghrelin mixed with 12.5 nM [3H]-octanoyl ghrelin. Separate reactions were carried out at 23 °C and 37 °C.

3.2 Sensitivity, specificity, and precision

Assay sensitivity was defined by the lowest substrate concentration yielding twice-blank signals. As [3H]-octanoyl ghrelin stock contains spontaneously released [3H]-octanoic acid (~25%), substrate was cleaned before each assay by dilution in 0.02 N HCl followed by three extractions with 10-fold volumes of toluene. The aqueous phase was then mixed with different amounts of unlabeled ghrelin and diluted to 2 nCi/μl. After this wash, buffer blanks dropped sharply (300 cpm) but then increased at a steady rate of ~ 10 cpm/min. Therefore, for maximum sensitivity, substrate reactions were initiated immediately. With 20-min assays the sensitivity was 250 pM, close to ghrelin's natural level in human plasma. With 1 hr-assays, sensitivity tripled (~ 75 pM). The assays were not only sensitive but also highly reproducible. Relative standard deviation in simultaneous replicates was < 3% and “intermediate precision” (S.D. of mean values from identical experiments on 3 different dates) was < 10%.

To test linearity, regression lines were fitted to sample counts over blank as a function of time and enzyme level. Human BChE generated linear increases in signal cpm (R2 > 0.999) with increasing enzyme concentration or incubation time so long as less than 25% of substrate was hydrolyzed (Fig. 3 A and B). A 20-min pre-incubation with the selective, irreversible BChE inhibitor, iso-OMPA, suppressed enzymatic hydrolysis completely (Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3.

Ghrelin hydrolysis as a function of enzyme level and incubation time. A: Wild-type human BChE in varying concentrations (0.3 – 20 nM) was incubated 10 min with or without the BChE-specific inhibitor, iso-OMPA (100 μM). Substrate (500 nM unlabeled ghrelin plus 12.5 nM [3H]-ghrelin) was then added and incubated for 20 min. B: BChE incubations with ghrelin for varying times. Data are means of duplicates. Blanks (~300 cpm) replaced enzyme with buffer.

3.3 Catalytic properties of BChE with ghrelin as substrate

To obtain enzyme suitable for substrate kinetics study, cDNA for wild-type and mutant versions of human or mouse BChE were incorporated into AAV-vectors that in turn were injected into mice. As described in METHODS, BChE proteins were purified from mouse serum harvested at the time of peak expression. SDS-PAGE gel electrophoresis of human wild-type BChE showed a single major band migrating at 85 kDa (Fig. 4A). After active site titration to determine the molar concentrations of enzyme (see METHODS), substrate kinetics with [3H]-octanoyl human ghrelin were examined (Fig. 4B). The kinetics data fitted well with the basic Michaelis-Menten equation, and yielded linear Lineweaver-Burk plots (Fig. 4C). Km and Vmax values were calculated by nonlinear regression analysis of the untransformed data. Native human BChE showed a Km of 3.6 ± 0.25 μM, a Vmax of 0.034 ± 0.001 μM/min, and a kcat of 2.2 ± 0.09 min−1.

Fig. 4.

Purification and kinetic analysis of human BChE. A: SDS-PAGE gel with single major protein bands of human BChE purified from sera of AAV-hBChE treated mice. B: Active-site titration with DFP to determine enzyme concentration. C: Km and Vmax of hBChE versus [3H]-ghrelin (100 nCi). Enzyme (5 nM) was incubated with substrate [S] at 0.025 μM – 25.6 μM. Michaelis-Menten plot (V0 versus [S]) and Lineweaver-Burk plot (inset) are shown.

Further experiments with [3H]-ghrelin compared the catalytic efficiency of native BChE and multiple variants carrying different active-site mutations to evaluate their potential for reducing plasma ghrelin levels in live subjects. Table 1 summarizes the resulting parameters. One mutated human BChE, “mut-6ΔC”, was 3-fold less efficient (kcat/Km = 0.22 ± 0.06 μM−1·min−1) than wild type enzyme (kcat/Km = 0.61 ± 0.04 μM−1·min−1). Also of interest, wild-type mouse BChE (kcat/Km = 19.71 ± 6.15 μM−1·min−1) proved 30-fold more efficient than its human counterpart.

Table 1.

Kinetic constants for hydrolysis of ghrelin by wild-type human BChE (hBChE WT), human BChE A199S/F227A/S287G/A328W/Y332G mutant (hBChE mut), human BChE A199S/F227A/S287G/A328W/Y332G ΔC mutant (hBChE mut ΔC), wild-type mouse BChE (mBChE WT), mouse BChE F329M mutant (mBChE F329M), mouse BChE A199S/S227A/S287G/A328W/Y332G mutant (mBChE mut)

| Km (μM) | kcat (min−1) | kcat/Km (μM−1 min−1) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| hBChE WT | 3.64 ± 0.25 | 2.19 ± 0.09 | 0.61 ± 0.04 |

| hBChE mut | 0.69 ± 0.11 | 0.33 ± 0.02 | 0.48 ± 0.15 |

| hBChE mut ΔC | 1.09 ± 0.21 | 0.24 ± 0.01 | 0.22 ± 0.06 |

| mBChE WT | 0.37 ± 0.03 | 7.31 ± 0.16 | 19.71 ± 6.15 |

| mBChE F329M | 0.44 ± 0.08 | 6.05 ± 0.38 | 13.85 ± 4.54 |

| mBChE mut | 1.22 ± 0.13 | 2.02 ± 0.06 | 1.66 ± 0.50 |

3.4 Tissue distribution

Utilizing the same principle of selective solvent extraction, a mirror-image assay was used to assess ghrelin distribution in mice given [3H]-peptide. For that purpose multiple tissues were collected and homogenized after DFP treatment to prevent de-acylation by esterases (see METHODS). The samples were then acidified and extracted with toluene to remove free octanoic acid. The remaining radioactivity, determined in water-compatible “Bio-Safe” scintillation fluor, was taken as an index of [3H] octanoyl-ghrelin.

Each assay tube contained an extract from 15 to 40 mg of tissue, and the assay signal ranged from 60 to 10,000 cpm, depending on tissue weight, sampling time, and amount of unlabeled peptide injected with the radiotracer. Like most short peptides and small molecule drugs, [3H]-ghrelin distributed rapidly to all tissues, with already strong signals 3-min after injection. Kidney accumulated 50% more than liver, which was the second most abundant recipient, and 40-fold more than brain, which had levels comparable to those in fat (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Tissue distribution of [3H]-ghrelin sampled 3 min after i.v. peptide (30 μg/kg, 5 μCi) in anesthetized mice pretreated with DFP. Ghrelin levels were determined by measuring water-soluble radiolabel in acid-treated homogenates of tissue samples processed immediately after collection. Data are expressed in nanograms of ghrelin per ml of plasma or per gram wet weight of tissue (means ± SEM, n = 3).

The further time course of radiolabeled ghrelin in the same tissues from the same mice is represented in Fig. 6. Highest concentrations were seen in kidneys, peaking between 6 and 12 min. Moderate amounts of radiolabel were found in liver, spleen, and pancreas, peaking at 6 min in liver and 12 min in spleen and pancreas. Brain label accumulated slower than in other tissues, but by 12 min brain was equivalent to fat and lung and remained so at 24 min. Similar concentration-time courses were observed in lung, heart, intestine, stomach, and muscle.

Fig. 6.

Time course of tissue [3H]-ghrelin after i.v. administration into DFP-pretreated mice. Mean concentrations are expressed as nanograms per gram of tissue. Three animals were sampled at each time point. Nominal ghrelin concentrations were calculated as described in METHODS on the assumption that all acid-soluble radiolabel was peptide-bound. Tissues: (A) Serum, kidney, liver, spleen, and pancreas. (B) Brain, heart, lung, intestine, stomach, muscle, and fat.

Ghrelin's amino acid chain is subject to lysis by peptidases abundant in plasma, not all of them DFP-sensitive. This raised a question: How much tissue radioactivity came from intact ghrelin and how much from octanoylated peptide fragments? To address that issue, aliquots of plasma samples from each time point were dialyzed with different molecular weight cutoffs, residual radiolabel was determined, and intact ghrelin was measured by ELISA. As illustrated in Fig. 7, plasma radioactivity fell sharply during dialysis with membranes that retain full-length ghrelin: 15% lost at 3 min and 90% at 24min. Parallel ELISA data showed even faster disappearance of intact ghrelin. These findings indicate rapid in vivo conversion of ghrelin to octanoylated fragments.

Fig. 7.

Intact ghrelin and ghrelin metabolites in plasma after ghrelin injection. Plasma was collected at 0, 3, 6, 12, and 24 min after i.v. injection of [3H]-ghrelin into DFP pretreated mouse (5 μCi per mouse). Equal amounts of plasma were dialyzed for 4 hours in cellulose ester tubing with 3 different molecular weight cut-offs (0.1-0.5 KD, 0.5-1.0 KD, and 3.5-5.0 KD). Residual ghrelin levels were estimated from the retained acid-soluble radioactivity. Aliquots of the raw plasma were assayed in parallel by ghrelin ELISA to determine levels of intact ghrelin.

4. Discussion

Radiometric ghrelin hydrolase assay separates and quantifies [3H]-octanoyl ghrelin and [3H]-octanoic acid, following procedures developed previously in our laboratory to characterize cocaine hydrolysis by native and mutated BChE [28]. This approach should be useful in defining the enzymatic properties of ghrelin hydrolases and identifying more efficient enzyme mutants for therapeutic use. In addition, the assay is readily adapted to evaluate aspects of the pharmacokinetics of exogenous ghrelin and its distribution in tissues and plasma.

Ghrelin is not highly stable. Its octanoyl form degrades easily during sample preparation [29-31]. For accurate data on ghrelin concentrations in vivo, blood samples and tissue homogenates were centrifuged, acidified, and analyzed immediately, or else frozen until assay. Our in vitro experiments with BChE used extensively purified enzyme. Even so, to ensure that results were not influenced by trace amounts of serum carboxylase or other esterases, parallel assays were run with two BChE-specific inhibitors, iso-OMPA and ethopropazine. As modest concentrations of either inhibitor stopped those reactions completely, BChE was probably the overwhelming driver of the ghrelin hydrolysis. This conclusion is further justified by the outcome of recent mass spectrometric studies by Schopfer et al [23], discussed further below.

The present data compare favorably with those we previously acquired with commercial ghrelin ELISA kits. In the ELISAs several factors limited the range of substrate concentrations for kinetics experiments. A chief limitation was a narrow assay range, from 1 to 250 pM, which necessitated a string of dilutions (up to 100,000-fold) to determine outcomes from the lowest to the highest relevant substrate concentrations. Despite considerable care, these dilution steps introduced error. Furthermore, completion of a single ELISA required several hours or more, which reduced throughput and exaggerated variation in the kinetic studies. By contrast, the [3H]-ghrelin radiometric assay improved efficiency, lowered the cost per sample, and produced consistent results.

We have found that mice over-expressing native or mutant BChE after AAV gene transfer exhibit moderate to large decreases in plasma ghrelin (90% or more) depending on the enzyme version and its level in the bloodstream [18]. Such effects were accompanied by behavioral changes that may offer therapeutic potential in stress disorders [18]. Thus it should be worthwhile to compare different BChE mutants for their impact on ghrelin. In vivo comparisons require tight control of enzyme and ghrelin expression levels, but radiometric assay allows rapid and precise determination of kinetic constants for ghrelin hydrolysis in vitro.

Ghrelin is the largest known BChE substrate, with a molecular weight of 3369 Da. It is striking that mouse BChE hydrolyzes this peptide so much better than human BChE, which is ~80% homologous and shares similar catalytic efficiency for butyrylthiocholine, acetylcholine, and cocaine [24, 32, 33]. Because mouse BChE exhibits a 10-fold lower Km and 3-fold higher kcat than human BChE we conclude that ghrelin docking in the active site must differ widely across species. In human BChE, oddly, ghrelin hydrolysis is affected by the C-terminus, which promotes BChE oligomerization [34, 35] but hasn't been thought to participate in catalysis. Deleting the C-terminus does not affect enzymatic activity with butyrylthiocholine, benzoylcholine, or nitrophenylbutyrate [34], although it enhances protein expression and protects nascent BChE from degradation in the endoplasmic reticulum [36]. Our previous molecular dynamics simulation of ghrelin docking [18] did not examine the C-terminus, but further study is justified.

Overall, our kinetic data on ghrelin hydrolysis by human BChE are in fair agreement with the recent MALDI TOF mass spectrometry results from Schopfer et al [23]. The prior study characterized ghrelin hydrolysis by exceptionally pure human BChE, simultaneously monitoring the disappearance of acyl-ghrelin (3369 Da) and the stoichiometric appearance of desacyl-ghrelin (3243 Da). The results yielded a Km of ~1 μM, and a kcat of ~1.4 min−1 and they revealed substrate inhibition when ghrelin concentration exceeded 10 μM. Reaction rates in our experiments were slightly higher, though well within expected laboratory to laboratory variation. Our failure to detect substrate inhibition may reflect the different systems for measuring reaction product. Schopfer et al calculated reaction rates based on dynamic changes in the normalized ratio between signal intensities for ghrelin and desacyl ghrelin [23]. Here the appearance of free octanoic acid was measured instead. Theoretically, both approaches to detection and quantitation are sound and should generate identical results. It is unlikely that contaminating proteases or esterases affected [3H]-ghrelin hydrolysis in either set of experiments, and there is good evidence that the tritium label was correctly placed on ghrelin's octanoyl group. We therefore suggest that the kinetic parameters are in approximate agreement, and the absence of substrate inhibition in the current data may accurately reflect the kinetics of ghrelin hydrolysis. Alternatively, we hypothesize that BChE may have a slightly lower activation energy for hydrolysis of tritiated ghrelin.

The pharmacokinetics of i.v. [3H]-ghrelin are consistent with previous findings that ghrelin's circulating half-life is brief: 8-13 min in humans [37, 38] and 8 min in rats [27], reflecting both metabolism (i.e., de-acylation and peptide degradation) and diffusion into tissue compartments. In this initial pharmacokinetic study, we focused on tissue disposition in mice pretreated with DFP to prevent hydrolysis of the octanoyl group. Direct measurements of radiolabeled peptide demonstrated widespread and rapid distribution of ghrelin and its metabolites from the bloodstream into various tissues. The finding that ghrelin-derived radioactivity was far greater in the kidney and liver than in most other tissues is consistent with older literature [39]. These two organs have a primary role in metabolizing and excreting exogenous substances. Our observations probably reflect that function and do not suggest that they are major targets for ghrelin-driven actions. With the liver in particular, a tissue rich in BChE, this metabolic role may be especially prominent. In contrast, brain was slower to accumulate the labeled peptide but later on it caught up with well-perfused tissues lacking tight diffusion barriers, i.e., lung, heart, muscle, and fat pads. Such observations support the concept that pulses of ghrelin emanating from a peripheral source (e.g., stomach) will quickly reach growth-hormone secretagogue receptors in CNS, complimenting signals transmitted through vagal afferents [40, 41]. Our data also reveal that endogenous peptidases cause surprisingly rapid fragmentation of ghrelin without affecting its octanoyl moiety. This finding raises the question whether “chopped” peptide retains receptor activity. In any case, continued analysis of ghrelin distribution and elimination in mice should be useful not only in future studies in humans, but also in understanding the pharmacology and toxicology of ghrelin in a clinical context.

In conclusion, although ELISA kits for acyl- and desacyl-ghrelin are available, as well as high-performance liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry procedures, assays with [3H]-octanoyl ghrelin offer reliability, reproducibility, specificity, and long-term economy. Our data indicate that such assays are well suited for screening mutated forms of BChE or other ghrelin hydrolases to modulate ghrelin-driven actions for therapeutic purposes. They may also help advance understanding of ghrelin biosynthesis and regulation in clinical conditions involving emotional and behavioral functions influenced by this important hormone.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by grant MNP13.05 from the Minnesota Partnership for Biotechnology and Medical Genomics, and by the Mayo Foundation for Medical Research.

Abbreviations

- BChE

Butyrylcholinesterase

- AAV

adeno-associated viral vector

- DFP

di-isopropyl fluorophosphate

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Peino R, Baldelli R, Rodriguez-Garcia J, Rodriguez-Segade S, Kojima M, Kangawa K, et al. Ghrelin-induced growth hormone secretion in humans. Eur J Endocrinol. 2000;143:R11–4. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.143r011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Takaya K, Ariyasu H, Kanamoto N, Iwakura H, Yoshimoto A, Harada M, et al. Ghrelin strongly stimulates growth hormone release in humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85:4908–11. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.12.7167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tschöp M, Smiley DL, Heiman ML. Ghrelin induces adiposity in rodents. Nature. 2000;407:908–13. doi: 10.1038/35038090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wren AM, Small CJ, Abbott CR, Dhillo WS, Seal LJ, Cohen MA, et al. Ghrelin causes hyperphagia and obesity in rats. Diabetes. 2001;50:2540–7. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.11.2540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Perello M, Dickson SL. Ghrelin Signalling on Food Reward: A salient link between the gut and the mesolimbic system. J Neuroendocrinol. 2015;27:424–34. doi: 10.1111/jne.12236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kirchner H, Heppner KM, Tschop MH. The role of ghrelin in the control of energy balance. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2012:161–84. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-24716-3_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nakazato M, Murakami N, Date Y, Kojima M, Matsuo H, Kangawa K, et al. A role for ghrelin in the central regulation of feeding. Nature. 2001;409:194–8. doi: 10.1038/35051587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Masuda Y, Tanaka T, Inomata N, Ohnuma N, Tanaka S, Itoh Z, et al. Ghrelin stimulates gastric acid secretion and motility in rats. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;276:905–8. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lutter M, Sakata I, Osborne-Lawrence S, Rovinsky SA, Anderson JG, Jung S, et al. The orexigenic hormone ghrelin defends against depressive symptoms of chronic stress. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11:752–3. doi: 10.1038/nn.2139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rouach V, Bloch M, Rosenberg N, Gilad S, Limor R, Stern N, et al. The acute ghrelin response to a psychological stress challenge does not predict the post-stress urge to eat. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2007;32:693–702. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2007.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nakashima K, Akiyoshi J, Hatano K, Hanada H, Tanaka Y, Tsuru J, et al. Ghrelin gene polymorphism is associated with depression, but not panic disorder. Psychiatr Genet. 2008;18:257. doi: 10.1097/YPG.0b013e328306c979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schanze A, Reulbach U, Scheuchenzuber M, Groschl M, Kornhuber J, Kraus T. Ghrelin and eating disturbances in psychiatric disorders. Neuropsychobiology. 2008;57:126–30. doi: 10.1159/000138915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carvajal P, Carlini VP, Schioth HB, de Barioglio SR, Salvatierra NA. Central ghrelin increases anxiety in the Open Field test and impairs retention memory in a passive avoidance task in neonatal chicks. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2009;91:402–7. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2008.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kristenssson E, Sundqvist M, Astin M, Kjerling M, Mattsson H, Dornonville de la Cour C, et al. Acute psychological stress raises plasma ghrelin in the rat. Regul Pept. 2006;134:114–7. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2006.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meyer RM, Burgos-Robles A, Liu E, Correia SS, Goosens KA. A ghrelin-growth hormone axis drives stress-induced vulnerability to enhanced fear. Mol Psychiatry. 2014;19:1284–94. doi: 10.1038/mp.2013.135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kojima M, Hosoda H, Date Y, Nakazato M, Matsuo H, Kangawa K. Ghrelin is a growth-hormone-releasing acylated peptide from stomach. Nature. 1999;402:656–60. doi: 10.1038/45230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Vriese C, Gregoire F, Lema-Kisoka R, Waelbroeck M, Robberecht P, Delporte C. Ghrelin degradation by serum and tissue homogenates: identification of the cleavage sites. Endocrinology. 2004;145:4997–5005. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-0569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen VP, Gao Y, Geng L, Parks RJ, Pang YP, Brimijoin S. Plasma butyrylcholinesterase regulates ghrelin to control aggression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:2251–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1421536112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hosoda H, Kojima M, Matsuo H, Kangawa K. Ghrelin and des-acyl ghrelin: two major forms of rat ghrelin peptide in gastrointestinal tissue. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;279:909–13. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.4039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yoshimoto A, Mori K, Sugawara A, Mukoyama M, Yahata K, Suganami T, et al. Plasma ghrelin and desacyl ghrelin concentrations in renal failure. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13:2748–52. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000032420.12455.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Akamizu T, Shinomiya T, Irako T, Fukunaga M, Nakai Y, Kangawa K. Separate measurement of plasma levels of acylated and desacyl ghrelin in healthy subjects using a new direct ELISA assay. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:6–9. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-1640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rauh M, Groschl M, Rascher W. Simultaneous quantification of ghrelin and desacyl-ghrelin by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry in plasma, serum, and cell supernatants. Clin Chem. 2007;53:902–10. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2006.078956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schopfer LM, Lockridge O, Brimijoin S. Pure human butyrylcholinesterase hydrolyzes octanoyl ghrelin to desacyl ghrelin. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2015.05.017. doi:10.1016/j.ygcen.2015.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Geng L, Gao Y, Zhan C, Taylor P, Radic Z, Parks R, et al. Viral gene transfer of mutant mouse butyrylcholinesterase provides lifetime high-level enzyme expression and reduced cocaine effects in mice, with no evident toxicity. PLoS One. 2013;8:e67446. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sun H, Pang YP, Lockridge O, Brimijoin S. Re-engineering butyrylcholinesterase as a cocaine hydrolase. Mol Pharmacol. 2002;62:220–4. doi: 10.1124/mol.62.2.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.National Research Council (U.S.). Committee for the Update of the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals., Institute for Laboratory Animal Research (U.S.), National Academies Press (U.S.) Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals. National Academies Press; Washington, D.C.: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hosoda H, Kangawa K. Ghrelin Measurement: Present and Perspectives. In: Ghigo E, Benso A, Broglio F, editors. Springer US; Ghrelin: 2004. pp. 225–36. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brimijoin S, Shen ML, Sun H. Radiometric solvent-partitioning assay for screening cocaine hydrolases and measuring cocaine levels in milligram tissue samples. Anal Biochem. 2002;309:200–5. doi: 10.1016/s0003-2697(02)00238-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hosoda H, Kangawa K. Chapter Eight - Standard Sample Collections for Blood Ghrelin Measurements. In: Masayasu K, Kenji K, editors. Methods Enzymol. Academic Press; 2012. pp. 113–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gröschl M, Wagner R, Dötsch J, Rascher W, Rauh M. Preanalytical Influences on the Measurement of Ghrelin. Clin Chem. 2002;48:1114–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kanamoto N, Akamizu T, Hosoda H, Hataya Y, Ariyasu H, Takaya K, et al. Substantial production of ghrelin by a human medullary thyroid carcinoma cell line. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:4984–90. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.10.7891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bartels CF, Xie W, Miller-Lindholm AK, Schopfer LM, Lockridge O. Determination of the DNA sequences of acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase from cat and demonstration of the existence of both in cat plasma. Biochem Pharmacol. 2000;60:479–87. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(00)00365-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sun H, Shen ML, Pang Y-P, Lockridge O, Brimijoin S. Cocaine Metabolism Accelerated by a Re-Engineered Human Butyrylcholinesterase. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002;302:710–6. doi: 10.1124/jpet.302.2.710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Blong RM, Bedows E, Lockridge O. Tetramerization domain of human butyrylcholinesterase is at the C-terminus. Biochem J. 1997;327:747–57. doi: 10.1042/bj3270747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen VP, Luk WK, Chan WK, Leung KW, Guo AJ, Chan GK, et al. Molecular assembly and biosynthesis of acetylcholinesterase in brain and muscle: The roles of t-peptide, FHB domain and N-linked glycosylation. Front Mol Neurosci. 2011;4:36. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2011.00036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Belbeoc'h S, Massoulié J, Bon S. The C-terminal t peptide of acetylcholinesterase enhances degradation of unassembled active subunits through the ERAD pathway. EMBO J. 2003;22:3536–45. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Akamizu T, Takaya K, Irako T, Hosoda H, Teramukai S, Matsuyama A, et al. Pharmacokinetics, safety, and endocrine and appetite effects of ghrelin administration in young healthy subjects. Eur J Endocrinol. 2004;150:447–55. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1500447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tong J, Dave N, Mugundu GM, Davis HW, Gaylinn BD, Thorner MO, et al. The pharmacokinetics of acyl, des-acyl, and total ghrelin in healthy human subjects. Eur J Endocrinol. 2013;168:821–8. doi: 10.1530/EJE-13-0072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wu R, Zhou M, Cui X, Simms HH, Wang P. Ghrelin clearance is reduced at the late stage of polymicrobial sepsis. Int J Mol Med. 2003;12:777–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Date Y, Shimbara T, Koda S, Toshinai K, Ida T, Murakami N, et al. Peripheral ghrelin transmits orexigenic signals through the noradrenergic pathway from the hindbrain to the hypothalamus. Cell Metab. 2006;4:323–31. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen HY, Trumbauer ME, Chen AS, Weingarth DT, Adams JR, Frazier EG, et al. Orexigenic Action of Peripheral Ghrelin Is Mediated by Neuropeptide Y and Agouti-Related Protein. Endocrinology. 2004;145:2607–12. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]