Abstract

Purpose

To describe bladder-associated symptoms in patients with urologic chronic pelvic pain syndromes (UCPPS) and to correlate these symptoms with urologic, non-urologic, psychosocial, and quality of life measures.

Methods

Participants were 233 women and 191 men with interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome or chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome in a multi-center study. They completed a battery of measures, including items asking if their pain worsened with bladder filling (“painful filling”) or if their urge to urinate was due to pain, pressure, or discomfort (“painful urgency”). Participants were categorized into 3 groups: 1) “both” painful filling and painful urgency, 2) “either” painful filling or painful urgency, or 3) “neither.”

Results

Seventy-five percent of men and 88% of women were categorized as “both” or “either.” These bladder characteristics were associated with more severe urologic symptoms (increased pain, frequency, urgency), higher somatic symptom burden, depression, and worse quality of life (all p<0.01, 3-group trend test). A gradient effect was observed across groups (both > either > neither). Compared to those in the “neither” group, men categorized as “both” or “either” reported more frequent UCPPS symptom flares, catastrophizing, and irritable bowel syndrome, and women categorized as “both” or “either” were more likely to have negative affect and chronic fatigue syndrome.

Conclusions

Men and women with bladder symptoms characterized as painful filling or painful urgency had more severe urologic symptoms, more generalized symptoms, and worse quality of life than participants who reported neither characteristic, suggesting that these symptom characteristics might represent important subsets of UCPPS patients.

Keywords: interstitial cystitis, chronic prostatitis, clinical phenotyping, bladder pain, painful urinary urgency

Given their overlapping clinical presentations, interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome (IC/BPS) and chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CP/CPPS) are described under the umbrella term of urologic chronic pelvic pain syndromes (UCPPS).1–6 Traditionally, women with pelvic pain and voiding symptoms are diagnosed with IC/BPS, even in the absence of bladder pain, while men with pelvic pain are typically diagnosed with CP/CPPS, even in the presence of voiding symptoms. IC/BPS patients commonly report that their pain is worse with bladder filling. In previous studies, 56 to 76% of female IC/BPS patients reported that their suprapubic pain was worse with bladder filling.7, 8 Hypersensitivity to bladder distention has also been demonstrated by quantitative sensory testing.9, 10 Besides painful bladder filling, painful urgency has also been described in IC/BPS.11 Notably, 2 recent studies have shown that, in 65% to 87% of female IC/BPS patients, the urge to urinate is primarily due to pain, pressure, or discomfort rather than to fear of leakage.12, 13

Nevertheless, the clinical significance of painful filling and painful urgency is not well understood in women or men. For instance, how would UCPPS patients with painful bladder filling or painful urgency different from those who do not have these bladder characteristics? Although many women report more severe pain with bladder filling, this is not a universal finding (it was observed in 56% to 76% of IC/BPS patients).7, 8 For men, information on the prevalence of bladder pain is limited and mostly anecdotal, because the National Institutes of Health Chronic Prostatitis Symptom Index (NIH-CPSI),14 an instrument commonly used in urologic studies with men, does not evaluate bladder pain.

UCPPS are traditionally associated with the bladder and the prostate. However, the literature suggests that non-urologic associated syndromes (NUAS), especially fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome, and irritable bowel syndrome, share demographic, clinical, and psychosocial features15 as well as objective findings that are consistent with a shared physiological mechanism, such as central sensitization.16–18 One unanswered question is whether UCPPS patients with painful filling or painful urgency have a larger burden of urologic symptoms, non-urologic symptoms, or NUAS than patients without these characteristics. We therefore used data collected by the Multi-disciplinary Approach to the Study of Chronic Pelvic Pain (MAPP) to examine this question. The objectives of this study are to: 1) describe bladder-associated symptoms in women and men with UCPPS, and 2) correlate these symptoms with NUAS and diverse psychosocial measures.

METHODS

Participants

The MAPP Research Network enrolled 191 men and 233 women with UCPPS at 6 clinical sites. Both the study design and the inclusion and exclusion criteria are described in detail in another publication.19 Women were enrolled if they met criteria for IC/BPS, defined as a self-reported sensation of pain, pressure, or discomfort localized in the bladder or pelvic region and associated with lower urinary tract symptoms. Symptoms had to be present most of the time during the most recent 3 months. Men were enrolled if they met the same IC/BPS criteria or either of the following CP/CPPS criteria: 1) self-reported pain or discomfort in the perineum, suprapubic area, testicles, or tip of the penis or 2) self-reported pain associated with urination, ejaculation, or sexual intercourse. Symptoms had to be present most of the time during any 3 of the previous 6 months.

Measures

MAPP included the following urologic measures: 1) IC symptom and problem indexes; 2) a genitourinary pain index (GUPI)20; 3) the American Urological Association symptom index; 4) the RAND Interstitial Cystitis Epidemiology (RICE) study instrument; 5) numeric ratings of pain, frequency, and urgency; 5) the Brief Pain Inventory; and 6) self-report of flares, defined as UCPPS symptoms much worse than usual.

The MAPP also used the Complex Multiple Symptoms Inventory (CMSI) to assess the burden of physical and mental symptoms. Participants who reported “gateway” symptoms on the CMSI (e.g., abdominal pain, diffuse muscle pain, or substantial fatigue) were further assessed for irritable bowel syndrome, fibromyalgia, and chronic fatigue syndrome by using standardized criteria.21

Psychosocial measures consisted of the Short Form-12 (SF-12); modules on fatigue, anger, and sleep from the Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS); the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; the Positive and Negative Affect Scale; the Coping Strategies Questionnaires; and the Perceived Stress Scale. Details of these instruments have been described previously.19 We limited our analyses to baseline data.

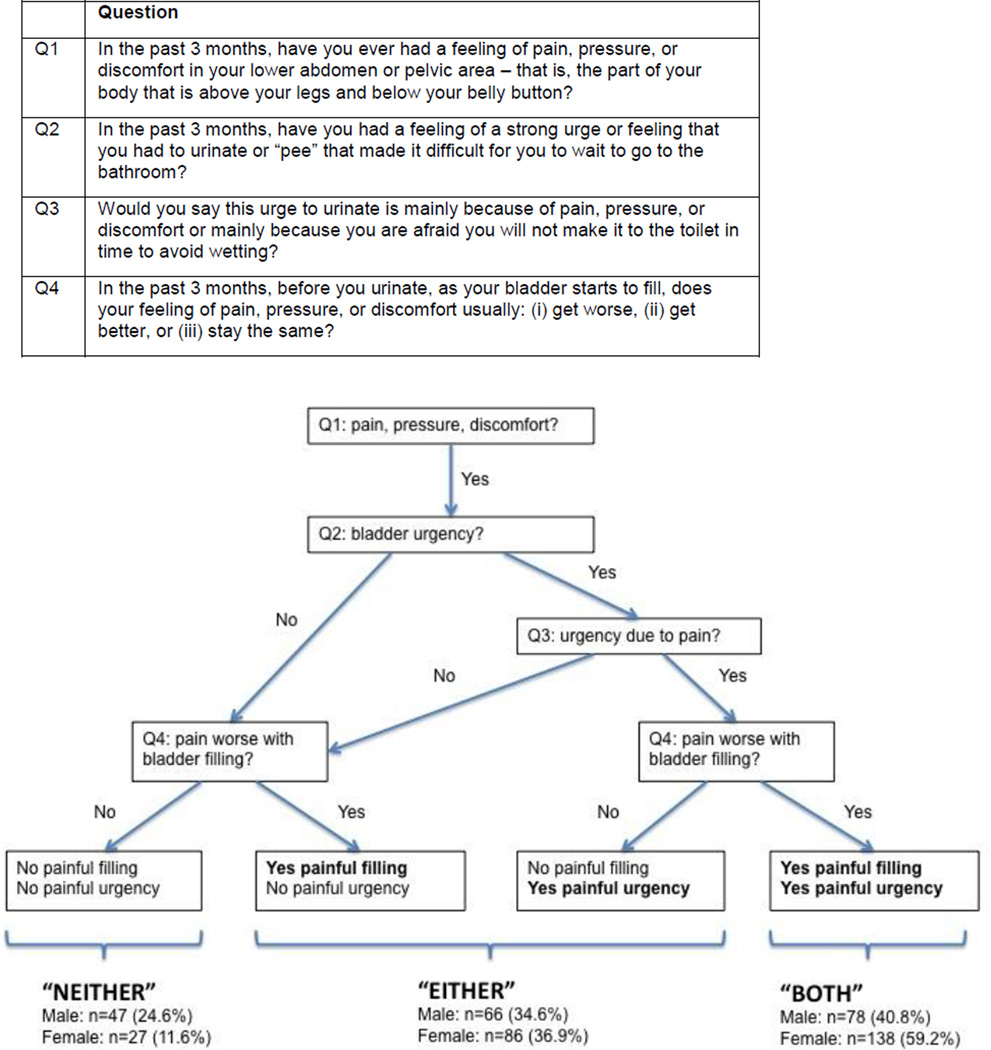

Assessment of Painful Filling and Painful Urgency

We used the RICE instrument to assess “painful filling” and “painful urgency” (Figure 1).5, 11, 22 All participants endorsed the presence of pelvic pain (Q1, the first item). The second item (Q2), which assessed urgency of urination, dichotomized participants into 2 groups. The 2 remaining items (Q3 and Q4) were used to create 3 mutually exclusive groups: participants with “neither” painful filling nor painful urgency, participants with “either” painful filling or painful urgency, and participants with “both” painful filling and painful urgency. Participants who reported increased pain with bladder filling were classified as having painful filling, and those who reported an urge to urinate due mainly to pain, pressure, or discomfort, but not to fear of incontinence, were categorized as having painful urgency.

Figure 1.

Assignment of the 3 BPS groups based on “painful filling” and “painful urgency”

Statistical Analyses

Analyses used all data for each variable. Few data were missing (< 5%) for outcomes other than pelvic tenderness examination (54 (13%) missing). No imputations or adjustments were performed for missing data. Means and standard deviations were reported for continuous variables and relative frequencies for categorical variables.

To test for a linear gradient effect in the 3 groups (both > either > neither, or both < either < neither), an ordinal value was assigned to each group, such that both = 2, either = 1, and neither = 0. Multivariable linear and logistic regression models adjusted for sex-specific confounder variables were then performed for the 3-group trend test. Comparisons were adjusted for race in men and age in women. To compensate for multiple comparisons, a 2-sided significance level of alpha = 0.01 was used. Analyses used SAS software 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Painful Filling and Painful Urgency

Overall, 24.6% of men and 11.6% of women had neither painful filling nor painful urgency (Table 1), while 34.6% of men and 36.9% of women had either painful filling or painful urgency, and 40.8% of men and 59.2% of women reported both characteristics.

Table 1.

Demographics

| Men (n = 191) | Women (n = 233) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | Neither (n = 47) |

Either (n = 66) |

Both (n = 78) |

Neither (n = 27) |

Either (n = 68) |

Both (n = 138) |

| Age, mean years (SD) | 46.2 (15.1) | 45.7 (15.2) | 48.1 (15.7) | 48.5 (14.7) | 39.3 (14.1) | 39.6 (14.0)* |

| White race, n (%) | 37 (79%) | 61 (92%) | 72 (92%)* | 22 (82%) | 59 (87%) | 123 (89%) |

| Non-Hispanic ethnicity, n (%) | 42 (89%) | 62 (94%) | 76 (97%) | 26 (96%) | 61 (90%) | 128 (93%) |

| Urologic / Non-urologic syndromes | ||||||

| Prior diagnosis of IC/BPS, n (%) | 2 (4%) | 13 (20%) | 29 (37%)† | 15 (56%) | 58 (85%) | 114 (83%) |

| Age at diagnosis, mean years (SD) | 40.3 (12) | 38.2 (12.7) | 41.0 (13.7) | 39.7 (18.2) | 24.0 (9.8) | 32.4 (8.2) |

| Prior CP/CPPS diagnosis, n (%) | 36 (77%) | 51 (77%) | 64 (82%) | 6 (22%) | 3 (4%) | 8 (5.8%) |

| Age at diagnosis, mean years (SD) | 38.5 (2.1) | 45.6 (13.0) | 44.5 (16.5) | 42.6 (14.6) | 33.5 (13.2) | 34.6 (13.0) |

| Met IC/BPS criteria, n (%) | 30 (64%) | 51 (77%) | 62 (80%)** | 27 (100%) | 68 (100%) | 138 (100%) |

| Met CP/CPPS criteria (men), n (%) | 47 (100%) | 65 (99%) | 78 (100%) | |||

| Medical history, n (%) | ||||||

| Genitourinary disorders | 9 (19%) | 23 (35%) | 18 (23%) | 9 (33%) | 16 (24%) | 40 (29%) |

| Gastrointestinal disorders | 14 (30%) | 23 (35%) | 25 (32%) | 10 (37%) | 19 (28%) | 41 (30%) |

| Psychiatric disorders | 7 (15%) | 15 (22%) | 23 (30%) | 10 (37%) | 32 (47%) | 61 (44%) |

| Sexually transmitted disease | 13 (28%) | 7 (11%) | 17 (22%) | 4 (15%) | 20 (29%) | 25 (18%) |

| Cardiovascular disorders | 14 (30%) | 22 (33%) | 29 (37%) | 6 (22%) | 16 (24%) | 32 (23%) |

| Physical examination, n (%) | ||||||

| Suprapubic tenderness (men) | 3 (6%) | 9 (14%) | 24 (31%)** | |||

| Pelvic floor tenderness | 8 (17%) | 14 (21%) | 23 (30%)† | 9 (33%) | 30 (44%) | 72 (52%) |

Men in the “both” and “either” groups were more likely to be White than were men in the “neither” group (p = 0.040). Women in the “both” and “either” groups were more likely to be younger than women in the “neither” group (p = 0.024).

p< 0.01;

p < 0.001;

Other Urologic Symptoms

We observed a gradient in pain severity and pain interference from neither to either to both, with successively higher mean GUPI pain sub-scores and Brief Pain Inventory pain interference scores (Table 2, p < 0.001). Mean scores also increased in the same pattern for urgency, frequency, number of daily voids, GUPI urinary sub-scores, IC symptom and problem indexes, and American Urological Association symptom index (p ≤ 0.001). Men, but not women, were also increasingly more likely to report a current flare across the gradient from neither to either to both.

Table 2.

Comparison of urologic symptoms (adjusted)*, ** statistical significance.

| Men (n = 191) | Women (n = 233) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neither (n = 47) |

Either (n = 66) |

Both (n = 78) |

p value (3 group trend) |

Neither (n = 27) |

Either (n = 68) |

Both (n = 138) |

p value (3-group trend) |

|

| Duration of symptoms, mean years (SD) | 7.6 (12.5) | 8.2 (11.7) | 7.5 (8.6) | 0.921 | 8.6 (9.1) | 9.6 (10.9) | 9.0 (10.7) | 0.442 |

| Numeric rating of symptom severity, past 2 weeks (SD) | ||||||||

| Pain | 4.2 (2.0) | 4.7 (2.2) | 5.4 (2.3) | 0.003** | 4.3 (2.2) | 5.2 (2.2) | 5.5 (2.1) | 0.037 |

| Frequency | 2.9 (2.5) | 4.7 (2.4) | 5.8 (2.2) | <.001** | 3.9 (2.9) | 5.2 (2.6) | 5.7 (2.3) | 0.001** |

| Urgency | 2.8 (2.6) | 4.7 (2.4) | 5.7 (2.2) | <.001** | 3.4 (2.6) | 5.0 (2.8) | 5.5 (2.3) | <.001** |

| Number of voids (4 categories) | 1.7 (0.8) | 2.3 (0.8) | 2.7 (0.9) | <.001** | 2.2 (0.6) | 2.4 (1.0) | 2.8 (0.9) | <.001** |

| Overall urologic or pelvic pain symptoms | 4.2 (2.1) | 4.9 (2.3) | 5.5 (2.4) | 0.002** | 4.3 (2.5) | 5.4 (2.4) | 5.6 (2.2) | 0.059 |

| Overall non-urologic or non-pelvic pain symptoms | 2.1 (2.2) | 3.1 (2.4) | 2.9 (2.7) | 0.184 | 4.2 (2.7) | 3.7 (2.9) | 3.5 (2.8) | 0.211 |

| GUPI (Genitourinary Pain Index) | ||||||||

| Total score (0–45) | 19.7 (6.1) | 24.1 (8.3) | 27.9 (7.6) | <.001** | 19.5 (7.8) | 24.7 (9.6) | 28.7 (7.8) | <.001** |

| Pain score (0–23) | 10.0 (3.5) | 11.7 (4.1) | 14.0 (4.1) | <.001** | 9.4 (4.5) | 12.0 (4.9) | 14.0 (4.0) | <.001** |

| Urinary score (0–10) | 2.8 (2.4) | 5.1 (3.0) | 5.6 (2.4) | <.001** | 3.4 (2.6) | 5.2 (3.1) | 6.5 (2.6) | <.001** |

| Quality of life score (0–12) | 6.9 (2.6) | 7.2 (2.9) | 8.3 (2.6) | 0.002** | 6.7 (2.6) | 7.5 (3.3) | 8.2 (2.8) | 0.026 |

| IC symptom index (0–20) | 4.8 (3.6) | 8.2 (4.1) | 11.0 (4.2) | <.001** | 6.4 (4.8) | 10.3 (4.7) | 11.9 (3.7) | <.001** |

| IC problem index (0–16) | 3.4 (3.5) | 7.1 (3.8) | 9.9 (3.9) | <.001** | 5.4 (4.4) | 8.4 (3.9) | 10.8 (3.3) | <.001** |

| AUA Symptom index (0–35) | 7.0 (6.1) | 14.6 (7.3) | 17.6 (7.6) | <.001** | 9.0 (6.1) | 14.2 (8.1) | 19.4 (8.0) | <.001** |

| Flare status at baseline (yes/no) | 4 (9%) | 18 (27%) | 24 (31%) | 0.009** | 11 (41%) | 21 (31%) | 42 (31%) | 0.413 |

| The single most bothersome symptom is … | ||||||||

| symptoms in pubic or bladder area | 16 (34%) | 20 (30%) | 29 (37%) | 0.624 | 7 (26%) | 39 (57%) | 88 (64%) | 0.001** |

| symptoms in sex-specific area (men: perineum; women: vaginal area) | 18 (38%) | 18 (27%) | 9 (12%) | 0.001** | 2 (7%) | 4 (6%) | 5 (4%) | 0.222 |

| symptoms during or after sexual activity | 1 (2%) | 5 (8%) | 3 (4%) | 0.826 | 5 (19%) | 7 (5%) | 0.067 | |

| strong need to urinate with little or no warning | 1 (2%) | 1 (2%) | 7 (9%) | 0.068 | 3 (11%) | 5 (7%) | 5 (4%) | 0.085 |

| frequent urination during the day | 2 (4%) | 7 (11%) | 8 (10%) | 0.300 | 7 (10%) | 8 (6%) | 0.512 | |

| frequent urination at night | 2 (4%) | 2 (3%) | 11 (14%) | 0.040 | 4 (15%) | 4 (6%) | 11 (8%) | 0.732 |

| sense of not emptying bladder completely | 1 (2%) | 3 (5%) | 1 (1%) | 0.540 | 3 (11%) | 5 (7%) | 8 (6%) | 0.266 |

| Other symptoms | 5 (11%) | 8 (12%) | 9 (12%) | 0.850 | 3 (11%) | 4 (6%) | 4 (3%) | 0.126 |

| RICE: high specificity criteria | 3 (5%) | 78 (100%) | 9 (13%) | 138 (100%) | ||||

| RICE: high sensitivity criteria | 6 (13%) | 53 (80%) | 78 (100%) | <.001** | 3 (11%) | 57 (84%) | 138 (100%) | <.001** |

p-values were adjusted for race in men and for age in women because of demographic differences (see Table 1).

Non-urologic and Psychosocial Measures

In both men and women, across the gradient of BPS symptoms (neither to either to both), participants were increasingly more likely to have a higher somatic symptom burden in the past year (as calculated from the CMSI), higher depression scores on the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, and worse physical health on the SF-12 (Table 3, p < 0.01). In men, there was increased prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome and higher pain catastrophizing scores across the same gradient. In women, the likelihood of chronic fatigue syndrome, high PROMIS fatigue scores, having multiple NUAS (irritable bowel syndrome, fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome), negative affect on the Positive and Negative Affect Scale, and worse mental health sub-scores on the SF-12 increased across the same gradient.

Table 3.

Comparison of non-urologic, psychosocial, and quality of life measures (adjusted)*, ** statistical significance.

| Men (n = 191) | Women (n = 233) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neither (n = 47) |

Either (n = 66) |

Both (n = 78) |

p value (3 group trend) |

Neither (n = 27) |

Either (n = 68) |

Both (n = 138) |

p value (3 group trend) |

|

| NUAS (Non-Urologic Associated Syndromes) | ||||||||

| Irritable bowel syndrome | 7 (14.9%) | 16 (24.2%) | 28 (35.9%) | 0.010** | 6 (22.2%) | 19 (27.9%) | 51 (37.0%) | 0.060 |

| Fibromyalgia | 2 (4.3%) | 5 (7.6%) | 2 (2.6%) | 0.416 | 2 (7.4%) | 6 (8.8%) | 21 (15.2%) | 0.196 |

| Chronic fatigue syndrome | 1 (2.1%) | 3 (4.5%) | 5 (6.4%) | 0.214 | 6 (8.8%) | 34 (24.6%) | <.001** | |

| Any one of the above NUAS? | 9 (19.1%) | 20 (30.3%) | 30 (38.5%) | 0.026 | 8 (29.6%) | 24 (35.3%) | 71 (51.4%) | 0.007** |

| More than one of the above NUAS? | 1 (2.1%) | 3 (4.5%) | 4 (5.1%) | 0.425 | 5 (7.4%) | 28 (20.3%) | 0.003** | |

| Somatic Symptom Burden | ||||||||

| CMSI: last year | 6.8 (5.2) | 9.1 (4.8) | 10.4 (5.6) | <.001** | 11.0 (7.6) | 10.9 (7.3) | 14.4 (8.6) | 0.004** |

| CMSI: lifetime | 9.0 (10.0) | 10.6 (9.5) | 9.6 (9.5) | 0.669 | 11.2 (7.4) | 9.1 (8.6) | 9.9 (8.7) | 0.853 |

| Brief Pain Inventory | ||||||||

| Pain severity (0–10) | 3.2 (1.7) | 3.7 (2.1) | 4.1 (2.1) | 0.009** | 3.7 (1.9) | 4.2 (2.2) | 4.4 (1.8) | 0.147 |

| Pain interference (0–10) | 2.5 (2.3) | 2.9 (2.4) | 4.0 (2.6) | <.001** | 2.9 (2.5) | 3.9 (3.0) | 4.6 (2.8) | 0.009** |

| Number of body sites with pain checked on the body map (0–45) | 4.4 (3.2) | 3.9 (3.5) | 4.6 (4.3) | 0.678 | 6.1 (8.0) | 6.1 (6.5) | 7.8 (8.4) | 0.155 |

| SF-12 | ||||||||

| Physical Health (0–100) | 52.4 (8.4) | 51.7 (8.5) | 47.4 (9.2) | 0.002** | 47.9 (10.3) | 47.2 (10.0) | 43.6 (11.0) | 0.010** |

| Mental Health (0–100) | 46.0 (11.0) | 43.9 (10.1) | 43.7 (11.5) | 0.281 | 49.1 (8.1) | 44.8 (10.0) | 41.7 (10.4) | 0.003** |

| PROMIS | ||||||||

| Fatigue T Score (29.4–83.2) | 50.7 (6.9) | 52.5 (5.7) | 53.5 (7.4) | 0.031 | 52.7 (6.4) | 53.7 (6.9) | 56.8 (7.3) | 0.002** |

| Sleep disturbance (28.9–76.5) | 50.0 (7.5) | 53.1 (8.7) | 54.0 (9.5) | 0.031 | 53.8 (7.8) | 53.6 (9.5) | 57.4 (9.3) | 0.015 |

| Anger (32.4–85.2) | 53.3 (7.5) | 52.2 (8.8) | 55.5 (8.5) | 0.101 | 51.5 (9.0) | 52.8 (8.6) | 55.3 (9.4) | 0.060 |

| HADS | ||||||||

| Depression (0–21) | 4.6 (3.5) | 4.9 (3.5) | 6.5 (4.7) | 0.009** | 3.7 (3.6) | 4.7 (3.9) | 6.0 (4.5) | 0.007** |

| Anxiety (0–21) | 6.7 (3.8) | 7.1 (4.4) | 8.1 (4.5) | 0.055 | 6.3 (4.2) | 7.5 (4.2) | 8.4 (5.0) | 0.109 |

| PANAS | ||||||||

| Positive affect (5–50) | 31.4 (6.8) | 30.8 (7.2) | 29.8 (7.8) | 0.308 | 31.9 (7.3) | 29.4 (7.6) | 28.7 (8.1) | 0.196 |

| Negative affect (5–50) | 19.6 (7.2) | 20.3 (7.5) | 21.6 (7.8) | 0.141 | 17.5 (6.9) | 20.6 (7.9) | 22.8 (8.7) | 0.009** |

| Pain Catastrophizing: CSQ, total score (0–36) | 8.7 (6.9) | 9.0 (7.5) | 13.3 (9.5) | <.001** | 11.3 (9.0) | 15.2 (9.3) | 14.2 (8.4) | 0.873 |

| Perceived Stress Scale (0–40) | 15.7 (6.7) | 14.0 (6.9) | 16.3 (7.5) | 0.346 | 15.4 (8.1) | 16.4 (7.8) | 18.1 (8.7) | 0.185 |

p-values were adjusted for race in men and for age in women because of demographic differences (see Table 1). To help quantify the size of the differences between the “both” and “neither” groups, we have now included effect size calculations (Cohen’s d) for these comparisons. Cohen’s d value of 0.2 is commonly considered to be the minimal value for a clinically meaningful change. For depression (HADS-D): Cohen’s d = 0.61 for men, 0.44 for women. For pain catastrophizing (CSQ), Cohen’s d = 0.55 for men, 0.32 for women. For fatigue (PROMIS), Cohen’s d = 0.40 for men, 0.61 for women. For negative affect (PANAS), Cohen’s d = 0.26 for men, 0.67 for women. For SF-12 mental health, Cohen’s d = 0.20 for men, 0.79 for women. For many of these measures, the effect sizes are in the moderate range so they are clearly greater than “minimally clinically significant” (> Cohen’s d value of 0.2).

Abbreviations: CMSI = Complex Multiple Symptoms Inventory; CSQ = Coping Strategies Questionnaires; HADS = Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; NUAS = non-urologic associated syndrome; PANAS = Positive and Negative Affect Scale; PROMIS = Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System.

Painful filling: yes versus no

Since painful filling is a feature of IC/BPS and is embedded in the ICS definition of PBS (painful bladder syndrome),23 we have also stratified men and women into 2 groups (painful filling: yes versus no based on Q4 in Figure 1) instead of 3 groups (neither/either/both) (see Table 4). Overall, many the differences in urologic domains (e.g., pain, frequency, urgency) remained significant. However most of the differences in the non-urologic domains were no longer statistically significant, with the exceptions that men with painful filling reported higher somatic symptom burden, and women with painful filling were more likely to have chronic fatigue syndrome and symptom.

Table 4.

Painful filling: Yes versus No comparison (adjusted), ** statistical significance

| Painful Filling Men (n=191) |

3 Group Comparison Men* |

Painful Filling Women (n=233) |

3 Group Comparison Women* |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (n=97) |

Yes (n=94) |

(yes/no) p value |

(neither/ either/both) p value |

No (n=75) |

Yes (n=158) |

(yes/no) p value |

(neither/ either/both) p value |

|

| UROLOGIC DOMAINS | ||||||||

| Numeric rating of symptom severity, past 2 weeks (SD) | ||||||||

| Pain | 4.5 (2.1) | 5.3 (2.3) | 0.011 | 0.003** | 5.0 (2.3) | 5.4 (2.1) | 0.314 | 0.037 |

| Frequency | 3.9 (2.5) | 5.5 (2.4) | <.001** | <.001** | 4.7 (2.8) | 5.7 (2.3) | 0.013 | 0.001** |

| Urgency | 3.8 (2.6) | 5.5 (2.3) | <.001** | <.001** | 4.5 (2.9) | 5.4 (2.3) | 0.011 | <.001** |

| Number of void (4 categories) | 2.0 (0.9) | 2.6 (0.9) | <.001** | <.001** | 2.3 (0.9) | 2.7 (0.9) | 0.003** | <.001** |

| Overall urologic or pelvic pain symptoms | 4.6 (2.2) | 5.4 (2.4) | 0.024 | 0.002** | 5.1 (2.5) | 5.5 (2.2) | 0.238 | 0.059 |

| GUPI (Genitourinary Pain Index) | ||||||||

| Total score (0–45) | 21.9 (7.7) | 27.3 (7.7) | <.001** | <.001** | 23.6 (9.1) | 27.8 (8.5) | 0.001** | <.001** |

| Pain score (0–23) | 10.8 (4.0) | 13.6 (4.1) | <.001** | <.001** | 11.5 (4.8) | 13.5 (4.4) | 0.004** | <.001** |

| Urinary score (0–10) | 4.0 (2.9) | 5.5 (2.6) | <.001** | <.001** | 4.7 (3.1) | 6.2 (2.8) | <.001** | <.001** |

| QOL score (0–12) | 7.1 (2.8) | 8.1 (2.7) | 0.017 | 0.002** | 7.4 (3.0) | 8.0 (2.9) | 0.213 | 0.026 |

| IC symptom index (0–20) | 6.7 (4.3) | 10.4 (4.4) | <.001** | <.001** | 9.1 (5.2) | 11.6 (3.9) | <.001** | <.001** |

| IC problem index (0–16) | 5.5 (4.1) | 9.2 (4.2) | <.001** | <.001** | 7.5 (4.5) | 10.4 (3.5) | <.001** | <.001** |

| AUA Symptom index (0–35) | 11.3 (7.8) | 16.7 (7.8) | <.001** | <.001** | 12.5 (7.8) | 18.6 (8.2) | <.001** | <.001** |

| Flare status at baseline (yes/no) | 19 (19.6%) | 27 (28.7%) | 0.162 | 0.009** | 25 (33.3%) | 49 (31.0%) | 0.763 | 0.413 |

| The single most bothersome symptom is … | ||||||||

| symptoms in pubic/bladder area | 31 (32.0%) | 34 (36.2%) | 0.586 | 0.624 | 36 (48.0%) | 98 (62.0%) | 0.040 | 0.001** |

| symptoms in gender specific area | 31 (32.0%) | 14 (14.9%) | 0.007** | 0.001** | 6 (8.0%) | 5 (3.2%) | 0.097 | 0.222 |

| NON-UROLOGIC AND QUALITY OF LIFE DOMAINS | ||||||||

| NUAS (Non-Urologic Associated Syndromes) | ||||||||

| Irritable bowel syndrome | 20 (20.6%) | 31 (33.0%) | 0.058 | 0.010** | 19 (25.3%) | 57 (36.1%) | 0.092 | 0.060 |

| Fibromyalgia | 5 (5.2%) | 4 (4.3%) | 0.705 | 0.416 | 8 (10.7%) | 21 (13.3%) | 0.647 | 0.196 |

| Chronic fatigue syndrome | 3 (3.1%) | 6 (6.4%) | 0.253 | 0.214 | 5 (6.7%) | 35 (22.2%) | 0.006** | <.001** |

| Any one of the above NUAS? | 24 (24.7%) | 35 (37.2%) | 0.065 | 0.026 | 25 (33.3%) | 78 (49.4%) | 0.020 | 0.007** |

| More than one of the above NUAS? | 3 (3.1%) | 5 (5.3%) | 0.440 | 0.425 | 5 (6.7%) | 28 (17.7%) | 0.032 | 0.003** |

| Somatic Symptom Burden | ||||||||

| CMSI: last year | 8.0 (4.9) | 10.2 (5.7) | 0.007** | <.001** | 11.2 (7.7) | 13.9 (8.4) | 0.020 | 0.004** |

| Brief Pain Inventory | ||||||||

| Pain severity (0–10) | 3.4 (1.8) | 4.1 (2.1) | 0.010 | 0.009** | 4.1 (2.1) | 4.3 (1.8) | 0.591 | 0.147 |

| Pain interference (0–10) | 2.7 (2.3) | 3.8 (2.6) | 0.004** | <.001** | 3.7 (3.0) | 4.4 (2.8) | 0.090 | 0.009** |

| SF-12 | ||||||||

| Physical Health (0–100) | 51.7 (8.7) | 48.4 (9.0) | 0.015 | 0.002** | 47.3 (10.1) | 44.1 (11.0) | 0.034 | 0.010** |

| Mental Health (0–100) | 45.1 (10.7) | 43.4 (11.0) | 0.282 | 0.281 | 46.0 (9.9) | 42.2 (10.3) | 0.023 | 0.003** |

| PROMIS | ||||||||

| Fatigue T Score (29.4 – 83.2) | 51.8 (6.6) | 53.2 (6.9) | 0.179 | 0.031 | 53.2 (6.8) | 56.5 (7.2) | 0.002** | 0.002** |

| HADS | ||||||||

| Depression (0–21) | 4.8 (3.5) | 6.2 (4.5) | 0.021 | 0.009** | 4.4 (3.9) | 5.8 (4.4) | 0.033 | 0.007** |

| Anxiety (0–21) | 6.9 (4.2) | 8.0 (4.4) | 0.068 | 0.055 | 7.0 (4.3) | 8.3 (4.9) | 0.112 | 0.109 |

| PANAS | ||||||||

| Positive affect (5–50) | 30.9 (7.1) | 30.1 (7.6) | 0.509 | 0.308 | 30.4 (8.0) | 28.7 (7.8) | 0.188 | 0.196 |

| Negative affect (5–50) | 19.9 (7.5) | 21.4 (7.6) | 0.188 | 0.141 | 19.9 (8.0) | 22.3 (8.6) | 0.072 | 0.009** |

| Pain Catastrophizing: CSQ, total score (0–36) | 9.2 (7.2) | 12.1 (9.5) | 0.016 | <.001** | 13.6 (9.3) | 14.4 (8.5) | 0.798 | 0.873 |

DISCUSSION

In this large, multi-site study, we have 1) described bladder-associated symptoms in women and men with UCPPS, and 2) correlated these symptoms with NUAS, urologic and psychosocial measures.

One surprising finding of the study was that the percentage of men who reported painful urgency, painful bladder filling, or both, was very high (75%). This was unexpected, since pain with bladder filling7–10 or urgency due to pain, pressure, or discomfort12, 24 are classically associated with IC/BPS. All but one male participant met CP/CPPS criteria (Table 1), consistent with traditional CP/CPPS research. However, 64%, 77%, and 80% of men in the neither, either, and both groups, respectively, also met IC/BPS criteria (p=0.039, 3-group trend test). Across the gradient from neither to either to both, the men were increasingly more “IC-like”: they 1) had higher IC symptom and problem indexes (p<0.001), 2) were less likely to report perineal pain as their single most bothersome symptom (p=0.001), and 3) were more likely to have suprapubic tenderness on physical examination (p=0.002). Our data showed that 3 out of 4 of men with UCPPS have symptoms consistent with IC/BPS, and this overlapping between male IC/BPS and CP/CPPS is under-appreciated.1–6 Unfortunately many previous CP/CPPS studies did not specifically ask men about painful filling or painful urgency, nor did the NIH-CPSI instrument assessed these bladder symptoms.14

We recommend that future clinical trials and research efforts, particularly those involving men with UCPPS, use tools like the RICE questionnaire to further stratify subjects based on their bladder pain characteristics. An important clinical question is whether men with painful filling or painful urgency respond differentially to specific IC/BPS versus CP/CPPS treatments. This question needs further study. For male UCPPS patients who present with painful filling or painful urgency, clinicians might be advised to consider IC/BPS treatments if they do not respond to conventional CP/CPPS treatments. By “splitting” subjects into phenotypes rather than “lumping” them into one (heterogeneous) group, we have a better odd of identifying specific treatments that are preferentially more effective in subjects with certain phenotypes.

88% of women reported painful filling, painful urgency, or both. However, 12% of women reported neither characteristic, even though they reported pelvic pain, frequency and urgency. These patients may have a milder form of IC/BPS, or they may have another reason for pelvic pain, such as isolated pelvic floor dysfunction.

Painful filling and painful urgency in men and women were associated with more severe urologic symptoms, more generalized non-urologic symptoms and syndromes, and poorer quality of life. Since painful filling and painful urgency reflect bladder hypersensitivity, we anticipated a stepwise worsening of urologic symptoms. What grasped our attention is that participants with bladder hypersensitivity (both > either > neither) also had the worst systemic manifestations. Our data suggest that evaluating specific bladder pain symptoms is a worthwhile approach to rapidly identify discrete patient groups. Asking patients three simple questions on painful filling and painful urgency (Q2–Q4 in Figure 1) may help to identify UCPPS patients with the most severe pain, urologic, and non-urologic symptoms and psychosocial problems.

Men with bladder pain symptoms are more likely than others to have irritable bowel syndrome; high somatic symptom burden; pain catastrophizing; and depression. Our results generally agree with a recent cluster analysis showing that UCPPS men with bladder-specific features clustered with catastrophizing, depression, systemic and neurologic phenotypes, whereas UCPPS men with prostate-specific features clustered with pelvic or abdominal tenderness.25 As we move across the gradient from neither to either to both in men, the men were increasingly more “IC-like” (discussed above). There was an association between bladder hypersensitivity and higher catastrophizing scores in men but not in women. This suggested that pain catastrophizing is associated more with IC/BPS than with CP/CPPS. All female subjects in this study fulfilled the IC/BPS criteria and reported high pain catastrophizing scores, this may explain why differences between the 3 bladder groups were not detected in women.

Women on the other hand are more likely to be associated with multiple NUAS. We hypothesize that being a female might be a vulnerability factor that predicts the development of pain chronification and central sensitization, which presented as multiple functional pain syndromes within the same subject.

The implication of our findings is that UCPPS patients with bladder symptoms (men or women) should be screened for non-urologic syndromes,26, 27 and referred to the appropriate specialists if needed. Even though this should already be part of good clinical care for women with IC/BPS, this is not yet commonly done for men with UCPPS. The high prevalence of NUAS and psychosocial difficulties in men is under-appreciated in the community and this needs to be addressed. In our dataset, more than 1 in 4 UCPPS men (26.7%) have irritable bowel syndrome, a NUAS that is considered to occur predominantly in women, and normally would not be screened for in men. Many men with UCPPS also reported “flares” of their UCPPS symptoms, widespread somatic symptoms, depression, and pain catastrophizing.

This study laid the foundation for future studies with testable hypotheses. Having identified patient sub-groups at baseline, in ongoing MAPP data analyses we will investigate if patients with bladder characteristics will have better or worse longitudinal trajectories over the course of 12 months. While our intuition may lead us to think that the longitudinal trajectories would be worse when we move along the gradient from neither to either to both, this is not necessarily the most likely scenario. It is possible that patients with bladder hypersensitivity might respond better to peripherally targeted therapies (PTT) for IC/BPS and have better outcomes compared to those without bladder hypersensitivity. It is also possible that patients with bladder hypersensitivity might have the same longitudinal trajectories as those without bladder hypersensitivity. Currently there are no data in this area. This should be formally investigated. The MAPP study had collected biweekly data over 12 months, and we plan to assess prognosis based on baseline characteristics. In men specifically, it would also be insightful to investigate if men who are more “IC-like” (e.g., the “both” group) would do better, same, or worse than men who are more “CP-like” (e.g., the “neither” group).

We will also investigate whether patients with bladder characteristics will correlate with biomarker profiles (e.g., changes in urinary biomarkers, brain functional MRI) that would assist in objective phenotyping. In a recent functional MRI study, Kilpatrick et al showed that: 1) patients have altered functional connectivity between regions of the brain involved in bladder pain, and 2) the alteration in brain connectivity correlated with bladder hypersensitivity.28 In future studies, we plan to stratify UCPPS patients a priori based on these bladder sub-groups and study if patients with bladder characteristics will preferably respond better to peripherally targeted therapies (PTT, e.g., pentosan polysulfate). We hope to link specific symptom questions to specific pathologies or response to treatments, and to optimize the individualized management for UCPPS.

CONCLUSION

Men and women with UCPPS who have bladder symptoms characterized by painful filling or painful urgency also have more severe UCPPS symptoms, more systemic presentation of syndromes, and poorer quality of life than patients who reported neither characteristic, suggesting that these bladder symptoms might represent important subsets of UCPPS patients.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The MAPP Research Network acknowledges support through NIH grants U01 DK82315 (PI: Andriole), U01 DK82316 (PI: Landis), U01 DK82325 (PI: Buchwald), U01 DK82333 (PI: Lucia), U01 DK82342 (PI: Klumpp, Schaeffer), U01 DK82344 (PI: Kreder), U01 DK82345 (PI: Clauw, Clemens), and U01 DK82370 (PI: Mayer, Rodriguez). The NIDDK and MAPP Network investigators wish to thank the Interstitial Cystitis Association and the Prostatitis Foundation for their assistance in recruiting study participants and other network efforts.

We thank the participants and staff from the following sites that participated in MAPP: Northwestern University; University of California, Los Angeles; University of Iowa; Washington University; University of Washington; University of Michigan; University of Pennsylvania (Data Coordinating Core); University of Colorado Denver (Tissue Analysis & Technology Core); and Stanford University. We would also like to thank Dr. Bruce Naliboff at the University of California, Los Angeles, and Drs. John Kusek and Tamara Bavendam at the NIDDK for critical review of the manuscript, Dr. Raymond Harris at the University of Washington for professional editing of the manuscript, and Dr. Alisa Stephens at the University of Pennsylvania for statistical assistance.

This article reports independent research commissioned by the National Institutes of Health. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and are not necessarily those of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases or the Department of Health and Human Services.

Abbreviations

- CP/CPPS

chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome

- CMSI

Complex Multiple Symptoms Inventory

- CSQ

Coping Strategies Questionnaires

- GUPI

genitourinary pain index

- HADS

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale

- IC/BPS

interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome

- MAPP

Multi-disciplinary Approach to the Study of Chronic Pelvic Pain

- NIH-CPSI

National Institutes of Health Chronic Prostatitis Symptom Index

- NUAS

non-urologic associated syndromes (irritable bowel syndrome, fibromyalgia, or chronic fatigue syndrome)

- PANAS

Positive and Negative Affect Scale

- PROMIS

Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System

- PTT

peripherally targeted therapies

- RICE

RAND Interstitial Cystitis Epidemiology

- SF-12

Short Form-12

- UCPPS

urologic chronic pelvic pain syndromes

Footnotes

Appendix 1. Investigators in the MAPP Research Network

REFERENCES

- 1.Eisenberg ER, Moldwin RM. Etiology: where does prostatitis stop and interstitial cystitis begin? World J Urol. 2003;21:64. doi: 10.1007/s00345-003-0337-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pontari MA. Chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome and interstitial cystitis: are they related? Curr Urol Rep. 2006;7:329. doi: 10.1007/s11934-996-0013-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Forrest JB, Nickel JC, Moldwin RM. Chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome and male interstitial cystitis: enigmas and opportunities. Urology. 2007;69:60. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2006.08.1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kusek JW, Nyberg LM. The epidemiology of interstitial cystitis: is it time to expand our definition? Urology. 2001;57:95. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(01)01141-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Suskind AM, Berry SH, Ewing BA, et al. The prevalence and overlap of interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome and chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome in men: results of the RAND Interstitial Cystitis Epidemiology male study. J Urol. 2013;189:141. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.08.088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moldwin RM. Similarities between interstitial cystitis and male chronic pelvic pain syndrome. Curr Urol Rep. 2002;3:313. doi: 10.1007/s11934-002-0056-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Warren JW, Brown J, Tracy JK, et al. Evidence-based criteria for pain of interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome in women. Urology. 2008;71:444. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2007.10.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clemens JQ, Meenan RT, O'Keeffe Rosetti MC, et al. Prevalence of interstitial cystitis symptoms in a managed care population. J Urol. 2005;174:576. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000165170.43617.be. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ness TJ, Powell-Boone T, Cannon R, et al. Psychophysical evidence of hypersensitivity in subjects with interstitial cystitis. J Urol. 2005;173:1983. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000158452.15915.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fitzgerald MP, Koch D, Senka J. Visceral and cutaneous sensory testing in patients with painful bladder syndrome. Neurourol Urodyn. 2005;24:627. doi: 10.1002/nau.20178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berry SH, Bogart LM, Pham C, et al. Development, validation and testing of an epidemiological case definition of interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome. J Urol. 2010;183:1848. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.12.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clemens JQ, Bogart LM, Liu K, et al. Perceptions of "urgency" in women with interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome or overactive bladder. Neurourol Urodyn. 2011;30:402. doi: 10.1002/nau.20974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Greenberg P, Brown J, Yates T, et al. Voiding urges perceived by patients with interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome. Neurourol Urodyn. 2008;27:287. doi: 10.1002/nau.20516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Litwin MS, McNaughton-Collins M, Fowler FJ., Jr The National Institutes of Health chronic prostatitis symptom index: development and validation of a new outcome measure. Chronic Prostatitis Collaborative Research Network. J Urol. 1999;162:369. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(05)68562-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alagiri M, Chottiner S, Ratner V, et al. Interstitial cystitis: unexplained associations with other chronic disease and pain syndromes. Urology. 1997;49:52. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(99)80332-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang CC, Lee JC, Kromm BG, et al. Pain sensitization in male chronic pelvic pain syndrome: why are symptoms so difficult to treat? J Urol. 2003;170:823. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000082710.47402.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gracely RH, Petzke F, Wolf JM, et al. Functional magnetic resonance imaging evidence of augmented pain processing in fibromyalgia. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46:1333. doi: 10.1002/art.10225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Giesecke T, Gracely RH, Grant MA, et al. Evidence of augmented central pain processing in idiopathic chronic low back pain. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:613. doi: 10.1002/art.20063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Landis JR, Williams DA, Lucia MS, et al. The MAPP research network: design, patient characterization and operations. BMC Urol. 2014;14:58. doi: 10.1186/1471-2490-14-58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clemens JQ, Calhoun EA, Litwin MS, et al. Validation of a modified National Institutes of Health chronic prostatitis symptom index to assess genitourinary pain in both men and women. Urology. 2009;74:983. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2009.06.078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Williams DA, Schilling S. Advances in the assessment of fibromyalgia. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2009;35:339. doi: 10.1016/j.rdc.2009.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Berry SH, Elliott MN, Suttorp M, et al. Prevalence of symptoms of bladder pain syndrome/interstitial cystitis among adult females in the United States. J Urol. 2011;186:540. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.03.132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abrams P, Cardozo L, Fall M, et al. The standardisation of terminology of lower urinary tract function: report from the Standardisation Sub-committee of the International Continence Society. Neurourol Urodyn. 2002;21:167. doi: 10.1002/nau.10052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Berry SH, Bogart LM, Pham C, et al. Development, validation and testing of an epidemiological case definition of interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome. J Urol. 183:1848. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.12.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Samplaski MK, Li J, Shoskes DA. Clustering of UPOINT domains and subdomains in men with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome and contribution to symptom severity. J Urol. 2012;188:1788. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.07.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Krieger JN, Stephens A, Landis JR, et al. Non-urologic syndromes and severity of urological pain symptoms: Baseline evaluation of the National Institutes of Health Multidisciplinary Approach to Pelvic Pain Study. J Urol. 2013;189:e181. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Naliboff BD, Stephens AJ, Afari N, et al. Widespread psycholosocial difficulties in men and women with urologic chronic pelvic pain syndrome (UCPPS): Case-control findings from the MAPP Research Network. Urology. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2015.02.047. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kilpatrick LA, Kutch JJ, Tillisch K, et al. Alterations in resting state oscillations and connectivity within sensory and motor networks in women with interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome. J Urol. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2014.03.093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.