Abstract

Fragaria vesca (2n = 2x = 14), the woodland strawberry, is a perennial herbaceous plant with a small sequenced genome (240 Mb). It is commonly used as a genetic model plant for the Fragaria genus and the Rosaceae family. Fruit skin color is one of the most important traits for both the commercial and esthetic value of strawberry. Anthocyanins are the most prominent pigments in strawberry that bring red, pink, white, and yellow hues to the fruits in which they accumulate. In this study, we conducted a de novo assembly of the fruit transcriptome of woodland strawberry and compared the gene expression profiles with yellow (Yellow Wonder, YW) and red (Ruegen, RG) fruits. De novo assembly yielded 75,426 unigenes, 21.3% of which were longer than 1,000 bp. Among the high-quality unique sequences, 45,387 (60.2%) had at least one significant match to an existing gene model. A total of 595 genes, representing 0.79% of total unigenes, were differentially expressed in YW and RG. Among them, 224 genes were up-regulated and 371 genes were down-regulated in the fruit of YW. Particularly, some flavonoid biosynthetic pathway genes, including C4H, CHS, CHI, F3H, DFR and ANS, as well as some transcription factors (TFs), including MYB (putative MYB86 and MYB39), WDR and MADS, were down-regulated in YW fruit, concurrent with a reduction in anthocyanin accumulation in the yellow pigment phenotype, whereas a putative transcription repressor MYB1R was up-regulated in YW fruit. The altered expression levels of the genes encoding flavonoid biosynthetic enzymes and TFs were confirmed by quantitative RT-PCR. Our study provides important insights into the molecular mechanisms underlying the yellow pigment phenotype in F. vesca.

Introduction

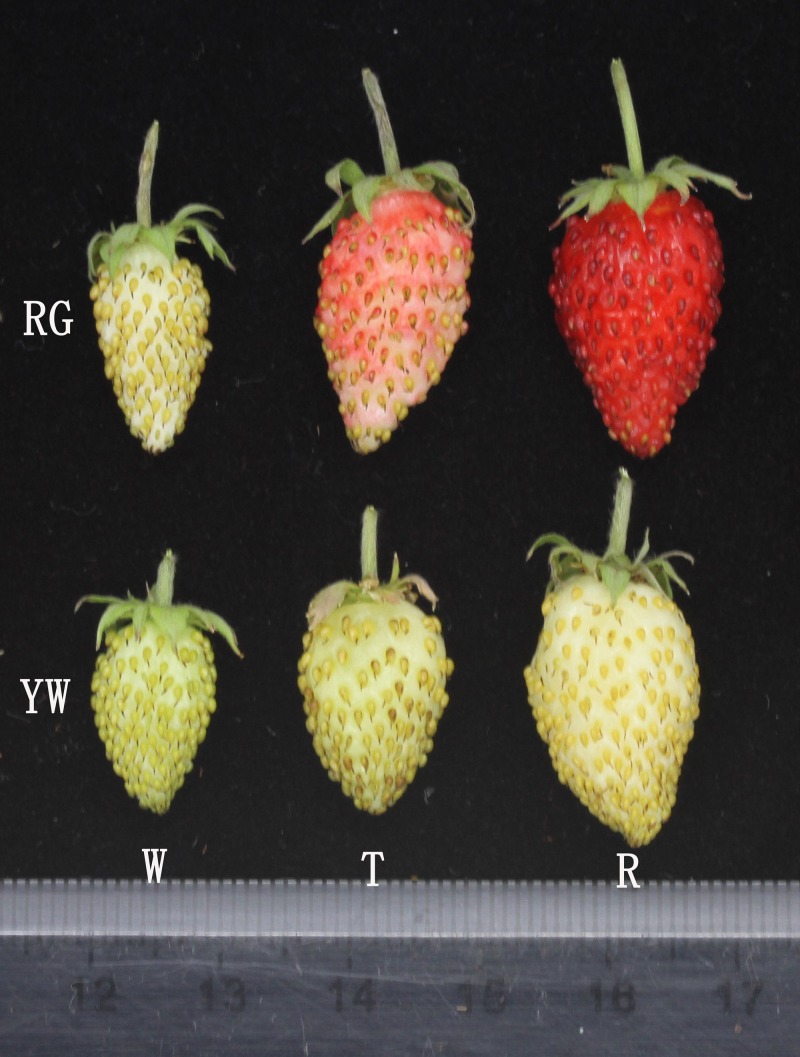

Fragaria vesca, commonly called woodland strawberry, is emerging as an advantageous alternative system for the cultivated octoploids as well as the Rosaceae family due to its small genome size (240 Mb), diploidy (2n = 2x = 14), small herbaceous stature, ease of propagation, short reproductive cycle, and facile transformation [1]. Woodland strawberry fruits are strongly flavored and have a wide variety of colors, such as red, yellow, white, and pink. Ruegen (RG) and Yellow Wonder (YW) are two botanical forms of F. vesca, both of which produce small-sized plants and propagate without runners. RG has fruits with red flesh and red skin, whereas YW fruits have both yellow flesh and skin (Fig 1). The availability of the F. vesca genomics resource affords opportunities to conduct comparative gene studies within the Rosaceae and identify important genes involved in flavonoid biosynthesis in strawberry [1].

Fig 1. Developmental and ripening stages of YW and RG as defined in this research.

Above: RG with white fruit, turning stage fruit and ripe fruit; Below: YW with white fruit, turning stage fruit and ripe fruit.

Anthocyanins are widely distributed in seed plants and responsible for orange to blue colors in various tissues, such as flowers, fruits, leaves, and seeds [2]. Numerous publications have confirmed that anthocyanins are derived from a plant secondary metabolite pathway, known as the flavonoid biosynthetic pathway [3]. The flavonoid biosynthetic pathway has been extensively studied in a number of plant species, and was recently described in strawberry [4,5]. Fruit pigmentation in strawberry appears to be determined by the expression of a set of genes involved in flavonoid biosynthetic pathway, including C4H (cinnamate 4-hydroxylase), CHS (chalcone synthase), CHI (chalcone isomerase), F3H (flavanone 3-hydroxylase), F3′H (flavonoid 3′-hydroxylase), DFR (dihydroflavonol-4-reductase), ANS (anthocyanidin synthase) and 3-GT (3-glycosyltransferase) [6,7], which are coordinated by regulatory proteins called transcription factors (TFs), such as MYB, bHLH, MADS, and WRKY [8,9].

RNA-Seq is a powerful, accurate and cost-effective method that produces millions of short cDNA reads [10]. The reads are aligned to both reference-based transcriptome assembly and de novo transcriptome assembly, to produce a genome-scale transcriptional profile for investigating transcriptional regulation [11]. RNA-Seq has been applied successfully in transcriptome profiling of species without genome sequencing data [12].

In this paper, we present a de novo assembly of the fruit transcriptome of F. vesca using Illumina-based RNA-Seq data. Differential gene expression between the red fruit and the yellow fruit was investigated to reveal the differential regulation of key pathways.

Materials and Methods

Plant material

Fragaria vesca accessions (Ruegen, RG) and (Yellow Wonder, YW) were grown in pots and maintained at Shenyang Agricultural University. Ruegen (F. vesca f. semperflorens D), the first modern cultivar, i.e., runnerless, everbearing and red fruited, originated from Castle Putbus in Germany. Yellow Wonder (F. vesca f. alba E) was first found in California, USA. YW has the recessive mutant traits, yellow fruit and runnerless. Three development and ripening stages were distinguished based on the weight and color of the receptacle: W, white fruit; T, turning stage; R, ripe fruit. Two biological replicates of each fruit sample were collected and immediately stored at -80°C after being quickly frozen in liquid nitrogen until use.

RNA extraction and quality assessment

Total RNA were isolated using the modified CTAB method described by Chang et al. [13], and the RNA samples were treated with DNase (TaKaRa, Japan) for 4 h. The integrity of the RNA samples was examined using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, USA).

cDNA library preparation and Illumina sequencing

Total RNA samples of RG and YW fruits at turning stage in two biological replicates were submitted to Biomarker Technology Company, Beijing, China for cDNA library preparation and sequencing reactions. The paired-end library preparation and sequencing were performed following standard Illumina methods using a DNA sample kit (#FC-102-1002, Illumina). The cDNA library was sequenced on the Illumina sequencing platform (HiSeq™ 2500).

De novo assembly

Reads from each library were assembled separately. The trimming adapter sequences were removed and low-quality reads (with unknown nucleotides larger than 5%) were filtered by the Biomarker Technology Company. The Trinity method [14] was used for de novo assembly of Illumina reads of woodland strawberry. Trinity consisted of three software modules—Inchworm, Chrysalis and Butterfly—applied sequentially to process large volumes of RNA-Seq reads. In the first step in Trinity, reads were assembled into the contigs by the Inchworm program. The minimally overlapping contigs were clustered into sets of connected components by the Chrysalis program, and then the transcripts were constructed by the Butterfly program [14]. In this study, only one k-mer length (25-mer) was chosen in Trinity, using the follow parameters: seqType fq, group pairs distance = 150 and other default parameters. Finally, the transcripts were clustered by similarity of correct match length beyond 80% of the longest transcript or 90% of the shortest transcript used multiple sequence alignment tool BLAT [15]. The longest transcript of each cluster was taken as the unigene. The Illumina data set has been deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under accession number SRX1294640.

Functional annotation

We annotated unigenes based on a set of sequential BLAST searches [16] to find the most descriptive annotation for each sequence. The assembled unigenes were compared with sequences in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) non-redundant (Nr) protein and nucleotide (Nt) databases (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov), the Swiss-Prot protein database (http://www.expasy.ch/sprot), the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway database (http://www.genome.jp/kegg), the Cluster of Orthologous Groups (COG) database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/COG), the Translated EMBL Nucleotide Sequence database (TrEMBL) (http://www.uniprot.org/), and the Protein family (Pfam) database (http://pfam.xfam.org/). The Blast2GO program [17] was used to obtain GO annotation of the unigenes. WEGO software (http://wego.genomics.org.cn/cgi-bin/wego/index.pl) was then used to perform GO functional classification of all unigenes to view the distribution of gene functions.

Digital gene expression analysis

Gene expression levels were measured in the RNA-Seq analysis as reads per kilobase of exon model per million mapped reads (RPKM) [18]. DESeq software [19] was used to identify differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in pair-wise comparisons, and the results of all statistical tests were revised for multiple testing with the Benjamini—Hochberg false discovery rate (FDR < 0.01). Sequences were deemed to be significantly differentially expressed if the adjusted P value obtained by this method was <0.001, and there was at least a twofold change (>1 or <− 1 in log 2 ratio value) in RPKM between the two libraries.

Quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis

cDNA was synthesized using Reverse Transcriptase XL (AMV) (TaKaRa, Japan) according to the manufacturer’s protocol in a 20 μL reaction system. The reverse transcription reaction mixture contained 5 μL total RNA (1 μg), 1 μL of each 10 mM dNTPs, 1 μL of random primer (9 mer) (50 μM), 1 μL oligo d(T)18 primer (50 μM) (TaKaRa, Japan), and 6 μL DEPC water. The mixture were incubated at 65°C for 5 min and cooled on ice for 5 min, then 4 μL 5× Reverse Transcriptase buffer, 1 μL RNasin (TaKaRa, Japan), and 1 μL AMV (5 U) were added. The mixture was incubated at 37°C for 2.5 h, and then the enzyme was inactivated by incubating at 72°C for 15 min. qPCR was carried out in an iQ5 Real Time PCR Detection System (BioRad, USA) with RealMasterMix SYBR Green (TIANGEN, China). Primers used for validation of differentially expressed genes are shown in S1 Table. All data were normalized with the level of the Fv26S internal transcript control. Relative fold changes in genes expression were calculated using the comparative Ct (2-ΔCt) method. Each sample was quantified in triplicate.

Total flavonoid content analysis

Total flavonoid analysis of fruit extracts in methanol was carried out based on the method of Swain and Hillis [20]. The flavonoid content was measured using a colorimetric assay developed by Jia et al. [21]. Absorbance was read at 510 nm against the blank (water) and flavonoid content was expressed as mg per gram of fresh weight.

Total anthocyanin content analysis

Determination of total anthocyanin content was performed following the methods detailed previously by Pirie and Mullins [22]. Total anthocyanin content was expressed as nmol per gram of fresh weight.

Results

Quantification of anthocyanins and flavone in YW and RG

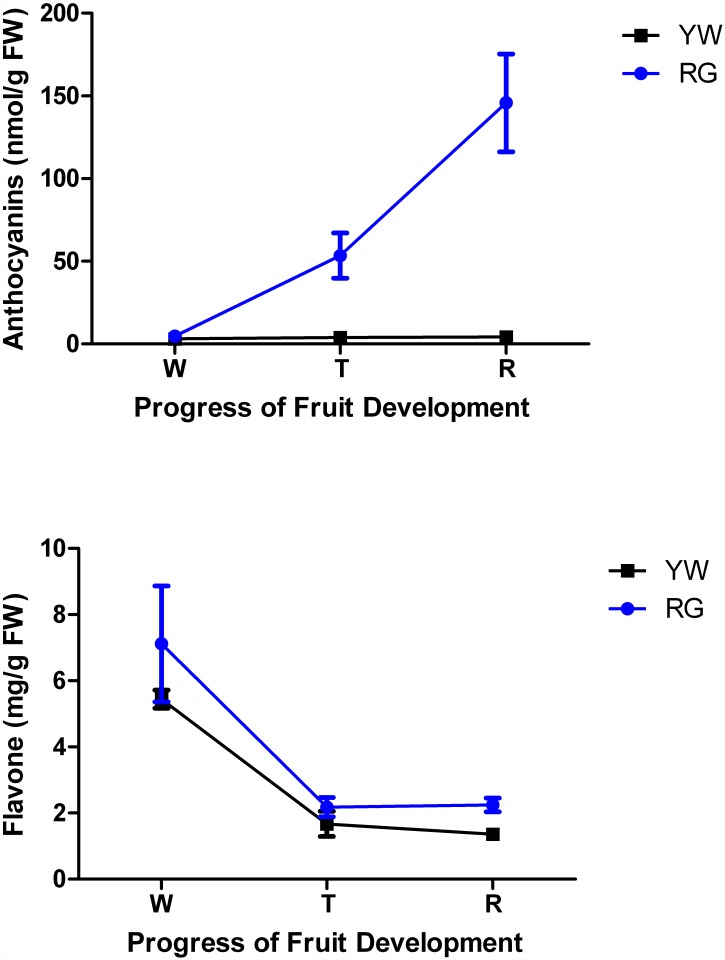

The anthocyanins and total flavone in YW and RG (Fig 1), two botanical forms of F. vesca with significant difference in fruit pigmentation, were examined. RG fruit, showed a continually increase in anthocyanins concomitant with the progress of fruit development and ripening. Conversely, no significant variation in the amounts of anthocyanins in YW fruit was observed during fruit ripening progress (Fig 1). High levels of anthocyanins were detected in red fruit from the turning stage to ripening, but not in yellow fruit. This difference led to the different phenotypic characteristics of the two types of F. vesca fruit. However, the flavone concentration in YW is not affected by the low levels of anthocyanins. YW and RG showed a similar trend in flavone accumulation. The amounts of flavone were highest in immature stages, and decreased concomitant with fruit ripening, reached a similar level in YW and RG at the ripe fruit stage. The amount of flavone in RG was slightly higher than that in YW when the fruit was mature (Fig 2).

Fig 2. Quantification of anthocyanins and flavone in YW and RG.

Blue lines represent Ruegen (RG), black lines represent Yellow Wonder (YW). The Y-axis represents the content of anthocyanins and flavone; the X-axis represents the progress of fruit development. W indicates white fruit; T indicates turning stage; R indicates ripe fruit.

De novo assembly and assessment of the Illumina ESTs

For RNA-Seq analysis, a total of four cDNA libraries were prepared using material from the turning stage fruits of RG and YW in two biological replicates. After removing low-quality reads and trimming adapter sequences, approximately 81.4 million high-quality pair-end reads from RG and YW were obtained, encompassing over 20.5 billion nucleotides (nt) of sequence data (Table 1). De novo assembly was carried out using the software Trinity to construct the full-length transcript, which was designed specifically for high-throughput RNA sequencing [23]. The mean length of contigs was approximately 42 bp, and the number of >200 bp contigs was 84,939 (Table 1). The transcripts were constructed using the Butterfly program of Trinity. Total of 139,997 transcripts were obtained, with average lengths of approximately 1,295 bp (Table 1).

Table 1. Summary of RNA-Seq and de novo assembly of Fragaria vesca unigenes.

| Sequences | |

|---|---|

| Total nucleotides | 20,501,684,236 |

| Number of clean reads | 81,421,741 |

| Number of >200-bp contigs | 84,939 |

| Mean length of contigs (bp) | 42.43 |

| N50 length of contigs (bp) | 43 |

| Number of >200-bp transcripts | 139,997 |

| Mean length of transcripts (bp) | 1,294.78 |

| N50 length of transcripts (bp) | 2,272 |

| Number of Unigenes | 75,426 |

| Mean length of Unigenes (bp) | 750.01 |

| N50 length of Unigenes (bp) | 1,380 |

These transcripts were assembled into unigenes. After combining the unigene data from RG and YW, a unigene database for strawberry containing 75,426 unigenes was established. The total length of the unigenes was 56,570,128 bp, and the mean length of individual unigenes was 750 bp. Among all the strawberry unigenes, 16,034 have lengths of more than 1,000 bp, representing 21.3% (16,034/75,426) of the total unigenes (Table 2). The size distribution of the assembled unigenes is shown in S1 Fig.

Table 2. The size distribution of Fragaria vesca unigenes.

| Length of unigene (bp) | No. of unigenes | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 200–300 | 27,798 | 36.85 |

| 300–500 | 18,384 | 24.37 |

| 500–1,000 | 13,210 | 17.51 |

| 1,000–2,000 | 9,486 | 12.58 |

| 2000+ | 6,548 | 8.68 |

| Total | 75,426 |

Functional annotation and characterization of unigenes

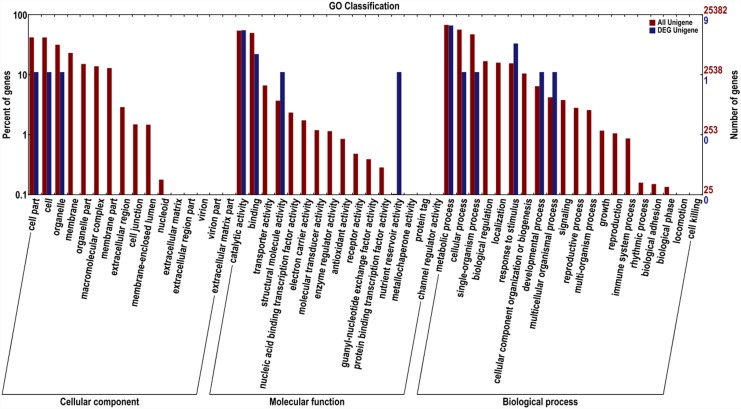

The entire unigenes were annotated on the basis of similarities to known or putative sequences in the web databases. Among the 75,426 unique sequences, 45,387 (60.2%) had at least one significant match to an existing gene model in BLAST searches (Table 3). Based on sequence homology, the unigenes of F. vesca were categorized into 52 functional groups, belonging to three main GO ontologies: cellular component, molecular function, and biological process (Fig 3). The results showed a high percentage of genes from the categories “metabolic process”, “cellular process”, “catalytic activity”, “binding” and “single-organism process”, with only a few genes related to “channel regulator activity”, “cell killing”, and “protein tag”.

Table 3. Summary of annotations of assembled strawberry (Fragaria vesca) unigenes.

| Category | Number of unigenes ≥300 bp | Number of unigenes ≥1,000 bp | Total number of annotated unigenes | Percentage (%) b |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| COG_Annotation | 11,584 | 6,617 | 14,710 | 19.5 |

| GO_Annotation | 17,979 | 8,847 | 25,382 | 33.7 |

| KEGG_Annotation | 7,568 | 3,923 | 10,067 | 13.3 |

| KOG_Annotation | 17,925 | 9,332 | 23,400 | 31.0 |

| Swiss-Prot_Annotation | 20,933 | 11,770 | 26,066 | 34.6 |

| Pfam_Annotation | 21,802 | 12,800 | 26,539 | 35.2 |

| TrEMBL_Annotation | 27,790 | 14,612 | 27,790 | 36.8 |

| Nr a _Annotation | 32,047 | 14,904 | 45,191 | 59.9 |

| All_Annotation | 32,136 | 14,915 | 45,387 | 60.2 |

a Nr = NCBI non-redundant sequence database

b Proportion of the 75,426 assembled unigenes

Fig 3. Histogram of the GO classifications of assembled Fragaria vesca unigenes.

The results are summarized in three main GO categories: cellular component, molecular function, and biological process.

Transcript differences between RG and YW

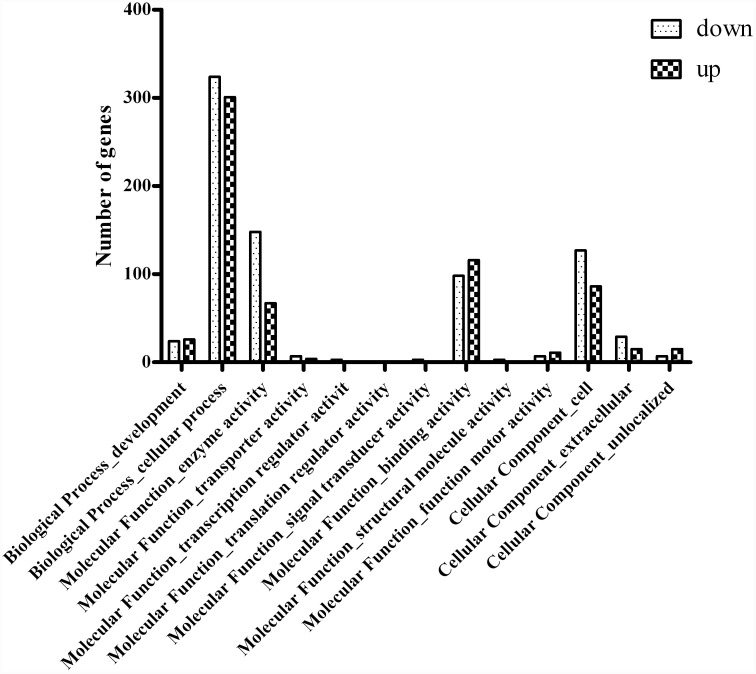

The general chi-squared test was used with a random sampling model in the DESeq software [19] to identify DEG in the turning stage fruits of RG and YW. A total of 595 genes, representing 0.79% (595/75,426) of the total unigenes, were differentially expressed in RG and YW (twofold or more change; p < 0.001) in both biological replicates. The detailed information on these genes is presented in S2 Table. Among the DEGs in the two types of fruit, 224 genes were up-regulated and 371 genes were down-regulated in YW. In addition, 98.0% (583/595) of the DEGs were detected in the fruits of both accessions. GO functional classes were assigned to the DEGs with putative functions. These genes were sorted into major functional categories (Fig 4). In an effort to identify key genes responsible for anthocyanin deposition in the fruit skin, flavonoid biosynthetic pathway genes were identified from the 595 DEGs.

Fig 4. Functional categories of 595 unigenes differentially expressed in Fragaria vesca accessions Yellow Wonder (YW) and Ruegen (RG).

Dark-colored bars indicate the genes up-regulated and light-colored bars indicate the genes down-regulated.

Some flavonoid pathway genes were down-regulated in the fruits of YW compared with the fruits of RG in both biological replicates, including the genes encoding C4H [EC 1.14.13.11], CHS [EC 2.3.1.74], CHI [EC 5.5.1.6], F3H [EC 1.14.11.9], DFR [EC 1.1.1.219] and ANS [EC 1.14.11.19] (Table 4). The gene expression ratios for each selected flavonoid pathway gene were shown in the flavonoid biosynthetic pathway [KEGG map00941 (http://www.genome.jp/kegg-bin/show_pathway?map00941)], and detailed information is presented in S1 File.

Table 4. Expression profiles of flavonoid biosynthesis genes in Fragaria vesca.

| Annotation | Unigene ID | Function | log2(YW/RG) |

|---|---|---|---|

| C4H | c19945.graph_c0 | Flavonoid biosynthetic | -1.78 |

| CHS (CHS2/CHS5) | c7666.graph_c0 | Flavonoid biosynthetic | -1.42 |

| CHI | c24522.graph_c0 | Flavonoid biosynthetic | -1.64 |

| F3H | c24499.graph_c0 | Flavonoid biosynthetic | -1.29 |

| DFR (DFR1) | c24714.graph_c0 | Flavonoid biosynthetic | -1.19 |

| ANS | c24538.graph_c0 | Flavonoid biosynthetic | -2.35 |

| MYB1 | c32867.graph_c0 | Transcription factor | -4.36 |

| MYB1R (MYB1R1) | c16952.graph_c0 | Transcription factor | 3.95 |

| MYB86-like | c10204.graph_c0 | Transcription factor | -1.80 |

| MYB39-like | c18291.graph_c0 | Transcription factor | -1.84 |

| WD-repeat (WDR) | c19202.graph_c0 | Transcription factor | -2.03 |

| MADS (AGL11-like) | c14603.graph_c0 | Transcription factor | -2.26 |

| MADS (AGL15-like) | c20999.graph_c0 | Transcription factor | -1.95 |

To identify regulatory factors that potentially controlled flavonoid biosynthesis, candidate transcription factors were chosen from the transcriptome data. We initially focused on MWB (MYB-bHLH-WD40) complex proteins, which were key factors in the regulation of primary and secondary metabolism [24]. Interestingly, one candidate MYB gene (c32867.graph_c0) annotated as the MYB1 gene that was known to control anthocyanin biosynthesis was identified [25], which was strongly down-regulated in the yellow fruit (YW) compared with the red fruit (RG) [log2(YW/RG) = -4.36] in both biological replicates. Some other TFs were down-regulated in YW, including two putative MYB TFs (annotated as MYB86 and MYB39), two putative MADS TFs (annotated as AGL11-like and AGL15-like gene), one putative WD-repeat protein (WDR) TFs (Table 4). Noticeably, a single-repeat MYB genes (Table 4), annotated as MYB1R and previously known as a repressors of anthocyanin accumulation [26], was significantly up-regulated in YW [log2 (YW/RG) = 3.95].

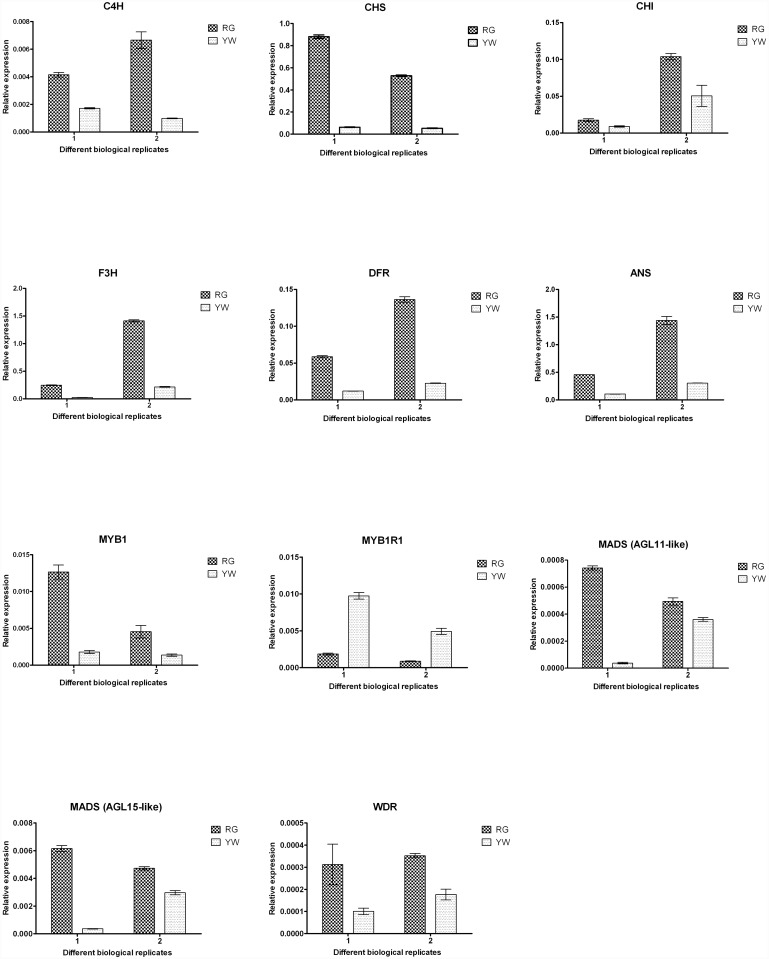

Quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis of the flavonoid pathway genes and TFs

To confirm the results of the Illumina RNA-Seq analysis, the expression levels of six flavonoid pathway genes (C4H, CHS, CHI, F3H, DFR and ANS) and the differently expressed TFs (MYB1, MYB1R, WDR, MADS) were tested in RG and YW by qRT-PCR using the same samples prepared for RNA-Seq. According to the qRT-PCR data (Fig 5), the transcript levels of the six flavonoid pathway genes and the TFs (MYB1, WDR, MADS) were greatly reduce in YW compared with RG, whereas MYB1R was clearly up-regulated in the fruits of YW with respect to RG. As shown in Fig 5, all chosen genes examined by qRT-PCR showed the same trends of mRNA accumulation patterns as identified in the RNA-Seq data.

Fig 5. The expression levels of six flavonoid pathway genes and the TFs at developmental stage T between two biological replicates samples using qRT-PCR.

Dark-colored bars indicate Ruegen (RG), light-colored bars indicate Yellow Wonder (YW). The Y-axis represents relative expression; the X-axis represents the different biological replicates.

Discussion

The genome of F. vesca was sequenced in 2010. This provided an invaluable resource for studying the molecular mechanisms influencing strawberry development. When a reference genome is available, the sequencing reads are aligned primarily by mapping on to the sequenced reference genome. However, although reference-based approaches is a robust and relatively precise way of characterizing transcript sequences, this method remains problems by its inability to account for un-sequenced genome or structural alterations within mRNAs, such as spliced variants, and also does not solve the problem of hypervariable sequences and private genes [23,27,28]. Moreover, relying on a single reference genome may underrate the variability among different genotypes. These challenges can be addressed by using a de novo assembly strategy. De novo assembly can reconstruct short sequences of transcripts into entire sequences of transcriptomes, identify all of the expressed genes, separate isoforms and quantify transcript expression levels, which do not depend on the genome [29]. In this study, a total of 20.5 Gb of raw sequence data were generated by Illumina sequencing of two botanical types of F. vesca, RG and YW, corresponding to 75,426 unigenes.

Genome-wide transcriptome analysis of the red and yellow strawberry fruit using RNA-Seq technology revealed significant down-regulation of a number of flavonoid pathway genes, both early biosynthetic genes C4H, CHS as well as CHI and late biosynthetic genes ANS and DFR (Table 4) concurrent with a reduction in anthocyanins accumulation and yellow pigment phenotype. Previous researches indicated that the lack of anthocyanin pigmentation seems to be caused by the down-regulation of these flavonoid pathway genes, i.e., the expression levels of CHS, F3H, DFR, ANS were less pronounced in yellow apple cultivar ‘Orin’ compared to the red apple cultivar ‘Jonathan’ [30]. The lack of anthocyanins in the Caryophyllales is caused by the suppression or limited expression of the DFR and ANS [31]. And, the lack of color in white native Chilean strawberry may be also attributed to the low expression of ANS [32]. Moreover, a candidate gene approach was used to determine the likely molecular identity of the c locus (yellow fruit color) in F. vesca, and the results showed that the c locus were tightly linked with the F3H gene [33], which suggested that F3H was necessary for red fruit color in F. vesca. RNAi silencing of F3H in strawberry fruits also exhibited that the anthocyanin content was greatly reduced and flavonol was also decreased [6]. Recently, it was found that differing hydroxylation pattern of anthocyanins in F. vesca and F. ×ananassa was reflected in the expression of F3’H and DFR1, and F3’H deficient lines displayed white or pale pigmentation phenotype [34]. In this study, a set of flavonoid pathway genes were down-regulated in yellow woodland strawberry fruits, including C4H, CHS, CHI, F3H, DFR and ANS, which indicated the transcript abundance of these genes were positively related to the accumulation of anthocyanin. In addition, the expression level of F3’H mentioned above showed no significant difference between yellow and red fruits of F. vesca in our RNA-Seq data. The co-down-regulation of many structural genes in YW indicates that yellow fruit phenotype is unlikely a mutation of one specific flavonoid pathway gene and multiple genes or transcription factors interacting with each other may account for the yellow coloration of woodland strawberry fruit.

The structural genes of plant flavonoid biosynthetic pathway are largely regulated at transcriptional level. The R2R3-MYB TFs played a key role in the regulation of the flavonoid pathway in most plant species [35,36]. R2R3-MYB TFs can interact or not with bHLH proteins and/or with WDR proteins [37]. Two of them, known as MYB10 and MYB1, have been extensively studied in numerous plant species and were recently described in strawberry. MYB10 regulates the expression of most of the early biosynthetic genes and the late biosynthetic genes involved in anthocyanin production in ripened strawberry fruits [38]. Over-expression the FvMYB10 in ‘Alpine’ strawberry F. vesca resulted in plants with elevated leaves, petioles, stigmas and fruit anthocyanin concentrations; while the mature fruit of FvMYB10 RNAi lines showed white fruit skin and white flesh [39]. FaMYB1 was described as a transcriptional repressor in regulating the biosynthesis of anthocyanins and flavonols in strawberry [25]. FvbHLH33, which is a potential bHLH partner for FvMYB10, did not affect the anthocyanin pathway when knocked down using an RNAi construct [39]. Suppressed expression of MBW complex protein encoded by FaTTG1 gene caused enhanced anthocyanin accumulation in strawberry fruit off plant [40].

In this study, the MBW members reported in strawberry (FvMYB10, FvbHLH33 and FaTTG1) were not involved in DEGs. Unexpectedly, MYB1 gene was significant down-regulated in the fruits of YW, and it was previous reported that the high level of transcripts of FcMYB1 was detected in white Chilean strawberry [32]. One possible explanation is the expression levels of MYB1 may be not the main cause of the loss of anthocyanins in YW fruits. However, MYB10 was well-known as a major regulator of anthocyanin biosynthesis in fruits [8,38]. Thus, MYB10 was still considered as an important candidate gene for anthocyanin accumulation in strawberry in this study. The coding regions of FvMYB10 from YW and RG were sequenced and a missense mutation was found in FvMYB10 due to a G to C base substitution at the 35th nucleotide of the cDNA sequence of YW, resulting in an amino acid Trp to Ser change (S2 File). The missense mutation might result in FvMYB10 gene dysfunction and affect many structural genes participated in flavonoid pathway biosynthesis, which might lead to the yellow color fruit phenotype in YW. Functional studies of the point mutation in FvMYB10 will be the next step to gain a better understanding of pigment-deficient phenotype in YW fruits.

In addition, a number of other TFs were differentially expressed in RG and YW, including two putative MYB TFs (annotated as MYB86 and MYB39), two putative MADS TFs (annotated as AGL11-like and AGL15-like), one putative WDR TF and one R3 single-repeat MYB TF (annotated as MYB1R). Among these TFs, MYB86 and MYB39 have not been proved to be involved in flavonoid biosynthesis until now. WDR is more likely to enhance gene activation rather than a direct regulatory function because it commonly has no obvious catalytic activity [37,41]. MYB1R TFs were reported as transcription repressors of anthocyanin biosynthesis in tobacco, Arabidopsis and Mimulus [26,42,43]. Overexpression of two novel MYB1R TFs (GtMYB1R1 and GtMYB1R9) in tobacco flowers induced a decrease in anthocyanin accumulation [26]. MADS is a highly conserved sequence motif found in a family of transcription factors. In plants, MADS genes commonly regulate the development of flower, ovule, fruit, leaf and root [44,45,46]. Recently, MADS genes were found in the plants that have been associated with flavonoid metabolism. ABS/TT16 from Arabidopsis is a member of Bs MADS subfamily GGM13-like gene, which was initially found in the control of flavonoid biosynthesis in the yellow seed coat [47]. A new MADS gene (IbMADS10) from sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas L.) was reported to be related to the red pigmentation [48]. Over-expressing IbMADS10 gene in Arabidopsis showed high accumulation of the anthocyanin pigments [49]. Silencing a SQUAMOSA-class MADS transcription factor, VmTDR4, resulted in substantial reduction in anthocyanin levels in ripe bilberry (Vaccinium myrtillus) fruits [50]. A gene named PyMADS18 and putatively involved in anthocyanin biosynthesis was found in pear (Pyrus communis L.) [51]. Therefore, the limited expression of MADS TFs and/or the high levels of transcription repressors MYB1R may also contribute to the pigment-deficient phenotype of YW fruits.

In summary, our results showed the use of RNA-Seq technology to perform a de novo assembly of the fruit transcriptomes of two botanical forms of F. vesca contrasting in fruit pigmentation. Our data revealed significant down-regulation of certain flavonoid biosynthetic genes, including C4H, CHS, CHI, F3H, DFR and ANS, concomitant with the pigment-deficient phenotype. In addition, we have identified some transcription factors including MYB, WDR and MADS that potentially control flavonoid biosynthesis.

Supporting Information

(EPS)

(RAR)

(DOC)

(XLS)

(XLS)

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

This research was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 31372037) and by Science and Technology Program of Liaoning Province (No. 2015204013). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Shulaev V, Sargent DJ, Crowhurst RN, Mockler TC, Folkerts O, Delcher A, et al. (2011) The genome of woodland strawberry (Fragaria vesca). Nature Genetics 43:109–116 10.1038/ng.740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tanaka Y, Sasaki N, Ohmiya A (2008) Biosynthesis of plant pigments: anthocyanins, betalains and carotenoids. Plant Journal 54:733–749 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03447.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Schijlen EGWM, Ric de Vos CH, van Tunen AJ, Bovy AG (2004) Modification of flavonoid biosynthesis in crop plants. Phytochemistry 65:2631–2648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lepiniec L, Debeaujon I, Routaboul JM, Baudry A, Pourcel L, Nesi N, et al. (2006) Genetics and biochemistry of seed flavonoids. Annual Review of Plant Biology 57:405–430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. De Almeida JRM, D’ Amico E, Preuss A, Carbone F, De Vos R, Deimi B, et al. (2007) Characterization of major enzymes and genes involved in flavonoid and proanthocyanidin biosynthesis during fruit development in strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa). Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics 465:61–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jiang F, Wang JY, Jia HF, Jia WS, Wang HQ, Xiao M (2013) RNAi-mediated silencing of the flavanone 3-hydroxylase gene and its effect on flavonoid biosynthesis in strawberry fruit. Journal of Plant Growth Regulation 32:182–190 [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ariel S, Paula P, Maria AM, Caligari PDS, Raul H (2010) Comparison of transcriptional profiles of flavonoid genes and anthocyanin contents during fruit development of two botanical forms of Fragaria chiloensis ssp. chiloensis . Phytochemistry 71:1839–1847 10.1016/j.phytochem.2010.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lin-Wang K, Bolitho K, Grafton K, Kortstee A, Karunairetnam S, McGhie TK, et al. (2010) An R2R3 MYB transcription factor associated with regulation of the anthocyanin biosynthetic pathway in Rosaceae . BMC Plant Biology 10:50–66 10.1186/1471-2229-10-50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zhao L, Gao LP, Wang HX, Chen XT, Wang YS, Yang H, et al. (2013) The R2R3-MYB, bHLH, WD40, and related transcription factors in flavonoid biosynthesis. Functional & Integrative Genomics 13:75–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Qiu Q, Ma T, Hu QJ, Liu BB, Wu YX, Zhou HH, et al. (2011) Genome-scale transcriptome analysis of the desert poplar, Populus euphratica . Tree Physiology 31:452–461 10.1093/treephys/tpr015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wang Z, Gerstein M, Snyder M (2009) RNA-Seq: a revolutionary tool for transcriptomics. Nature Reviews Genetics 10:57–63 10.1038/nrg2484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wilhelm BT, Landry JR (2009) RNA-Seq-quantitative measurement of expression through massively parallel RNA-sequencing. Methods 48:249–257 10.1016/j.ymeth.2009.03.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chang L, Zhang Z, Yang H, Li H, Dai H (2007) Detection of strawberry RNA and DNA viruses by RT-PCR using total nucleic acid as a template. Journal of Phytopathology 155:431–436 [Google Scholar]

- 14. Grabherr MG, Haas BJ, Yassour M, Levin JZ, Thompson DA, Amit I, et al. (2011) Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-Seq data without a reference genome. Nature Biotechnology 29:644–652 10.1038/nbt.1883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kent WJ (2002) BLAT-The BLAST-like alignment tool. Genome Research 12:656–664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schäffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, et al. (1997) Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Research 25:3389–3402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Conesa A, Götz S, García-Gómez JM, Terol J, Talón M, Robles M (2005) Blast2GO: a universal tool for annotation, visualization and analysis in functional genomics research. Bioinformatics 21:3674–3676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mortazavi A, Williams BA, McCue K, Schaeffer L, Wold B (2008) Mapping and quantifying mammalian transcriptomes by RNA-Seq. Nature Methods, 5: 621–628 10.1038/nmeth.1226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Anders S, Huber W (2010) Differential expression analysis for sequence count data. Genome Biology 11:106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Swain T and Hillis WE (1959) The phenolic constituents of Prunus domestica. I—The quantitative analysis of phenolic constituents. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture 10:63–68 [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jia ZS, Tang MC and Wu JM (1999) The determination of flavonoid contents in mulberry and their scavenging effects on superoxide radicals. Food Chemistry 64:555–559 [Google Scholar]

- 22. Pirie A and Mullins MG (1976) Changes in anthocyanin and phenolic content of grapevine leaf and abscisic acid. Plant Physiology 58: 468–472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Roberts A, Trapnell C, Donaghey J, Rinn JL, Pachter L (2011) Improving RNA-Seq expression estimates by correcting for fragment bias. Genome Biology 12:22–35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Dubos C, Stracke R, Grotewold E, Weisshaar B, Martin C, Lepiniec L (2010) MYB transcription factors in Arabidopsis . Trends in Plant Science 15:573–581 10.1016/j.tplants.2010.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Aharoni A, De Vos CHR, Wein M, Sun ZK, Greco R, Kroon A, et al. (2001) The strawberry FaMYB1 transcription factor suppresses anthocyanin and flavonol accumulation in transgenic tobacco. Plant Journal 28: 319–332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Nakatsuka T, Yamada E, Saito M, Fujita K, Nishihara M (2013) Heterologous expression of gentian MYB1R transcription factors suppresses anthocyanin pigmentation in tobacco flowers. Plant Cell Reports 32: 1925–1937 10.1007/s00299-013-1504-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Trapnell C, Williams BA, Pertea G, Mortazavi A, Kwan G, van Baren MJ, et al. (2010) Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA-Seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation. Nature Biotechnology 28:516–520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Birol I, Jackman SD, Nielsen CB, Qian JQ, Varhol RJ, Stazyk G, et al. (2009) De novo transcriptome assembly with ABySS. Bioinformatics 21:2872–2877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Oono Y, Kobayashi F, Kawahara Y, Yazawa T, Handa H, Itoh T, et al. (2013) Characterisation of the wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) transcriptome by de novo assembly for the discovery of phosphate starvation-responsive genes: gene expression in Pi-stressed wheat. BMC Genomics 14:77–91 10.1186/1471-2164-14-77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Honda C, Kotoda N, Wada M, Kondo S, Kobayashi S, Soejima J, et al. (2002) Anthocyanin biosynthetic genes are coordinately expressed during red coloration in apple skin. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 40:955–962 [Google Scholar]

- 31. Shimada S, Inoue YT, Sakuta M (2005) Anthocyanidin synthase in non-anthocyanin-producing Caryophyllales species. Plant Journal 44:950–959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Salvatierra A, Pimentel P, Moya-Leon MA, Herrera R (2013) Increased accumulation of anthocyanins in Fragaria chiloensis fruits by transient suppression of FcMYB1 gene. Phytochemistry 90: 25–36 10.1016/j.phytochem.2013.02.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Deng C, Davis TM (2001) Molecular identification of the yellow fruit color (c) locus in diploid strawberry: a candidate gene approach. Theoretical and Applied Genetics 103:316–322 [Google Scholar]

- 34. Miosic S, Thill J, Milosevic M, Gosch C, Pober S, Molitor C, et al. (2014) Dihydroflavonol 4-reductase genes encode enzymes with contrasting substrate specificity and show divergent gene expression profiles in Fragaria Species. PLoS One 9:e112707 10.1371/journal.pone.0112707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Allan AC, Hellens RP, Laing WA (2008) MYB transcription factors that colour our fruit. Trends in Plant Science 13:99–102 10.1016/j.tplants.2007.11.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Schwinn K, Venail J, Shang YJ, Mackay S, Alm V, Butelli E, et al. (2006) A small family of MYB-regulatory genes controls floral pigmentation intensity and patterning in the genus Antirrhinum. Plant Cell 18:831–851 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hichri I, Barrieu F, Bogs J, Kappel C, Delrot S, Lauvergeat V (2011) Recent advances in the transcriptional regulation of the flavonoid biosynthetic pathway. Journal of Experimental Botany 62:2465–2483 10.1093/jxb/erq442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Laura MP, Guadalupe CL, Francisco AR, Thomas H, Ludwig R, Antonio RF, et al. (2014) MYB10 plays a major role in the regulation of flavonoid/phenylpropanoid metabolism during ripening of Fragaria ×ananassa fruits. Journal of Experimental Botany 65:401–417 10.1093/jxb/ert377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lin-Wang K, McGhie TK, Wang M, Liu YH, Warren B, Storey R, et al. (2014) Engineering the anthocyanin regulatory complex of strawberry (Fragaria vesca). Frontiers in Plant Science 5: 1–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Chen JX, Mao LC, Mi HB, Zhao YY, Ying TJ, Luo ZS (2014) Detachment-accelerated ripening and senescence of strawberry (Fragaria ×ananassa Duch. cv. Akihime) fruit and the regulation role of multiple phytohormones. Acta Physiologiae Plantarum 36: 2441–2451 [Google Scholar]

- 41. Baudry A, Heim MA, Dubreucq B, Caboche M, Weisshaar B, Lepiniec L (2004) TT2, TT8, and TTG1 synergistically specify the expression of BANYULS and proanthocyanidin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana . Plant Journal 39:366–380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Zhu HF, Fitzsimmons K, Khandelwal A, Kranz RG (2009) CPC, a single-repeat R3 MYB, is a negative regulator of anthocyanin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis . Molecular Plant 2:790–802 10.1093/mp/ssp030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Yuan YW, Sagawa JM, Young RC, Christensen BJ (2013) Genetic dissection of a major anthocyanin QTL contributing to pollinator-mediated reproductive isolation between sister species of Mimulus . Genetics 194:255–263 10.1534/genetics.112.146852 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Riechmann JL, Meyerowitz EM (1997) MADS domain proteins in plant development. Biological Chemistry 378:1079–1101 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Smyth D (2000) A reverse trend: MADS functions revealed. Trends in Plant Science 5:315–317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Ng M, Yanofsky MF (2001) Function and evolution of the plant MADS-box gene family. Nature Reviews Genetics 2:186–195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Nesi N, Debeaujon I, Jond C, Stewart AJ, Jenkins GI, Caboche M, et al. (2002) The TRANSPARENT TESTA 16 locus encodes the Arabidopsis Bsister MADS domain protein and is required for proper development and pigmentation of the seed coat. Plant Cell 14:2463–2479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Antonio G, Lalusin KN, Kim SH, Ohta M, Fujimura T (2006) A new MADS-box gene (IbMADS10) from sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas (L.) Lam) is involved in the accumulation of anthocyanin. Molecular Genetics and Genomics 275:44–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Lalusin AG, Ocampo ETM, Fujimura T (2011) Arabidopsis thaliana plants over-expressing the IbMADS10 gene from sweet potato accumulates high level of anthocyanin. Philippine Journal of Crop Science 36:30–36 [Google Scholar]

- 50. Jaakola L, Poole M, Jones MO, Kämäräinen-Karppinen T, Koskimäki JJ, Hohtola A, et al. (2010) A SQUAMOSA MADS box gene involved in the regulation of anthocyanin accumulation in bilberry fruits. Plant Physiology 153:1619–1629 10.1104/pp.110.158279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Wu J, Zhao G, Yang YN, Le WQ, Khan MA, Zhang SL, et al. (2013) Identification of differentially expressed genes related to coloration in red/green mutant pear (Pyrus communis L.). Tree Genetics & Genomes 9:75–83 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(EPS)

(RAR)

(DOC)

(XLS)

(XLS)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.