Abstract

This review provides a practical approach to the imaging evaluation of patients with cervical cancer (CC), from initial diagnosis to restaging of recurrence, focusing on MRI and FDG PET. The primary updates to the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) CC staging system, as well as these updates’ relevance to clinical management, are discussed. The recent literature investigating the role of MRI and FDG PET in CC staging and image-guided brachytherapy is summarized. The utility of MRI and FDG PET in response assessment and posttreatment surveillance is described. Important findings on MRI and FDG PET that interpreting radiologists should recognize and report are illustrated. The essential elements of structured reports during various phases of CC management are outlined. Special considerations, including the role of imaging in patients desiring fertility-sparing management, differentiation of CC and endometrial cancer, and unusual CC histologies, are also described. Finally, future research directions including PET/MRI, novel PET tracers, and artificial intelligence applications are highlighted.

Keywords: cervical cancer, gynecologic cancer, imaging, MRI, PET

Cervical cancer (CC) is the fourth most common cancer in women worldwide. Most new cases and deaths occur in low-to-middle income countries [1]. The primary risk factor is persistent human papillomavirus (HPV), causing 99% of cases. Another key risk factor is HIV, which increases CC risk by sixfold [2]. Primary prevention entails vaccination against HPV [3]. Secondary prevention includes HPV DNA testing to screen for active infection and prompt treatment of cervical precancerous lesions [3, 4].

CC may be asymptomatic or may present with vaginal bleeding, pelvic pain, and dyspareunia. It is diagnosed by cervical cytology and biopsy. The WHO classifies epithelial CC into squamous (70–80% of cases), glandular (adenocarcinoma) (20–25%), and other epithelial (e.g., adenosquamous and neuroendocrine) tumors [5].

Revised FIGO Staging System

CC is staged using the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) system [6, 7]. Given the high CC prevalence in low-income countries, FIGO versions published before 2018 relied primarily on clinical examination, leading to frequent understaging or overstaging [8]. Furthermore, the staging system did not include lymph node (LN) status, a key factor impacting prognosis and treatment selection, because clinical examination cannot evaluate LN metastases [9]. Third, prior FIGO versions did not include fertility-sparing management.

The 2018 revision of the FIGO system addressed these shortfalls, aligning the FIGO system with the current practice of using advanced imaging, when available, to evaluate CC extent [6, 7] (Fig. 1). Imaging and pathologic findings now complement physical examination in stage determination, with inclusion of a notation to specify the method used. However, pathologic findings supersede clinical and imaging findings in stage determination.

Fig. 1—

Illustrations show cervical cancer stages according to International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) staging system [6, 7].

A, Cervix-confined invasive carcinoma is deemed FIGO stage I, which is divided into stage IA and stage IB. All stage IA tumors (not shown) are microscopic with maximum depth of stromal invasion of 5 mm or less. If stromal invasion is 3 mm or less, tumor is deemed stage IA1; if stromal invasion is from more than 3 mm to 5 mm, tumor is deemed stage IA2. All stage IB tumors (yellow) show stromal invasion of more than 5 mm in depth. Stage IB tumors that are 2 cm or smaller in greatest dimension are deemed stage IB1; more than 2 cm to 4 cm, stage IB2; and more than 4 cm, IB3.

B, In FIGO stage II, tumor has spread beyond cervix but has not spread into lower third of vagina or into pelvic sidewall. Stage IIA tumors (yellow, upper panel) involve upper two-thirds of vagina but not parametria, with stage IIA1 tumors being 4 cm or less in greatest dimension and stage IIA2 tumors measuring more than 4 cm in greatest dimension. Stage IIB tumors (yellow, lower panel) show parametrial invasion.

C, FIGO stage III tumors show spread beyond what is seen with stage II. Tumor (yellow, left panel) spread to lower third of vagina is stage IIIA. Stage IIIB involves one or more of: pelvic sidewall extension (yellow, middle panel), hydronephrosis, or nonfunctioning kidney. Tumors metastasizing to lymph nodes (LNs) (yellow, right panel) are stage IIIC: tumors metastasizing to pelvic LNs only are considered stage IIIC1 and tumors metastasizing to paraaortic LNs are considered stage IIIC2.

D, FIGO stage IV tumors involve bladder mucosa or rectum (proven by biopsy) or spread beyond true pelvis. In stage IVA, tumor (yellow, left panel) invades adjacent organs in pelvis, although bullous edema of bladder or rectum only is not enough to assign stage IVA. Stage IVB tumors show distant metastases, including spread to LNs beyond pelvic and paraaortic regions (yellow, right panel).

The 2018 FIGO system includes several key updates relevant to radiologists. Stage IB1 now includes three (instead of two) subgroups based on greatest tumor dimension: IB1, 2 cm or smaller; IB2, larger than 2 cm to 4 cm; and IB3, larger than 4 cm (Fig. 1). The additional cutoff (≤ 2 cm) reflects better prognosis and potential for fertility-sparing management in individuals with tumors 2 cm or smaller and desire for fertility [10]. A newly added stage IIIC indicates the presence of LN metastases (IIIC1, pelvic nodes only; IIIC2, paraaortic nodes without or with spread to pelvic nodes) (Fig. 1).

Primary Management as Informed by the 2018 FIGO System

Potential primary CC treatments include surgery for early-stage tumors versus concurrent chemoradiotherapy (CCRT) for locally advanced disease [11, 12] (Fig. 2). Surgical methods include hysterectomy or, if fertility is desired, conization or trachelectomy. Conization entails en bloc resection of the ectocervix (portion of the cervix protruding into the upper vagina) and endocervical canal. Figure 3 illustrates relevant cervical anatomy. Trachelectomy or hysterectomy may be simple or radical in extent. Simple hysterectomy entails removal of the entire uterus and cervix; radical hysterectomy also includes parametrial resection. Trachelectomy removes most of the cervix, leaving the uterus in place. Simple trachelectomy spares, whereas radical trachelectomy encompasses, the parametrium (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2—

Diagram illustrates how International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics stage informs management of cervical cancer. One asterisk indicates that paraaortic region may be included in radiation treatment if there is suspicion for common iliac lymph node (LN) metastases; two asterisks indicate that paraaortic lymphadenectomy may be performed if common iliac and/or paraaortic LN metastases are suspected on basis of FDG PET findings.

Fig. 3—

Relevant anatomy of cervix and surrounding structures.

A, Illustration shows sagittal view of uterus, cervix, vagina, and urinary bladder. Location of internal os (dotted line) is seen as narrowing between endocervical canal and endometrial cavity. Yellow dashed line illustrates orientation for oblique axial plane. Horizontal line at level of bladder neck approximately divides vagina into upper two-thirds and lower one-third.

B, Illustration shows that location of internal os in oblique axial plane is marked by entrance of uterine vessels (red and blue). Parametrium is connective tissues lateral to cervix.

Stage IA indicates microscopic disease (≤ 5 mm) that is not readily seen on imaging. Patients with visible tumors 4 cm or smaller that are confined to the cervix (IB1, IB2) or upper vagina (IIA1) and who have no desire for fertility are managed by radical hysterectomy [11, 12]. Premenopausal patients can be offered ovarian preservation, but bilateral salpingectomy should be considered. Young patients who wish fertility; who have squamous cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, or adenosquamous carcinoma; and who have a cervix-confined tumor that is 2 cm or smaller (i.e., ≤ IB1) may be eligible for conization or trachelectomy (usually combined with LN assessment) [10]. Traditional LN evaluation consists of lymphadenectomy, but sentinel LN (SLN) mapping and sampling have gained acceptance for treatment of tumors 2 cm or smaller (≤ IB1) [13]. SLNs are the first draining LNs identified after cervical injection with a dye(s).

Stages IB3 and IIA2 (tumor measuring > 4 cm and confined to the cervix or upper vagina) and locally advanced disease (stages IIB–IVA [i.e., spread into the parametria or beyond]) are managed with concurrent external beam radiation therapy (EBRT) and platinum-based chemotherapy followed by brachytherapy [11, 14, 15]. CCRT followed by MRI-based brachytherapy yields 90% local tumor control. Ovarian transposition is considered for patients younger than 45 years. Stage IVB disease (distant metastases) is approached with systemic chemotherapy and, if symptomatic, palliative EBRT [11].

The best imaging approach to determine locoregional tumor extent is pelvic MRI tailored to cervical evaluation [16]. Whole-body FDG PET (fused to CT or MRI) is advised for patients with stage IB3 or greater disease to detect LN metastases and distance disease [11].

Tailored Pelvic MRI and Whole-Body PET for Initial Staging

MRI

Patient preparation—

In our practices, we administer a microenema before MRI to induce a bowel movement and reduce distortion of DWI [17]. We also ask patients to empty their bladder to help with optimal uterine positioning.

Administration of an antiperistaltic agent (hyoscine butylbromide or glucagon) may diminish peristalsis-related artifacts [16, 18, 19]. Glucagon is the only antiperistaltic agent available in the United States and is administered IV or intramuscularly. The mean onset and duration of action are 1 minute and 23 minutes, respectively, after IV administration, and 12 minutes and 28 minutes, respectively, after intramuscular injection [19]. The most common side effects are nausea and emesis. Contraindications include prior hypersensitivity reaction, pheochromocytoma, and insulinoma [20]. Caution is advised in patients with diabetes, cardiac disease, or adrenal insufficiency [20].

No consensus exists regarding vaginal gel administration. Vaginal gel has high T2 signal intensity (SI) and potentially helps detect vaginal invasion by distending the vaginal lumen and outlining the ectocervix and vaginal fornices [21].

Tailored MRI protocol—

Either 1.5- or 3-T MRI scanners can be used depending on local resources and patient factors. Higher SNR at 3-T enables higher spatial resolution or shorter acquisition time. We use supine patient positioning and multichannel phased-array surface coils.

Large-FOV SSFSE axial or coronal T2-weighted imaging from the renal hilum to the pubic bone helps to detect hydronephrosis, hydroureter, and paraaortic LN metastases (Table 1). Axial T1-weighted imaging through the pelvis allows skeletal evaluation and pelvic LN evaluation.

TABLE 1:

Suggested Tailored MRI Protocol for Cervical Cancer Evaluation

| Sequence | Plane(s) | Rationale for Performing Sequence |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Large-FOV SSFSE T2-weighted imaging | Axial or coronal | Assess for hydronephrosis and/or hydroureter Detect paraaortic LN enlargement |

| FSE T1-weighted imaging or 3D in- and opposed-phase GRE T1-weighted imaging | Axial | Detect bone lesions Detect pelvic LN enlargement |

| Small-FOV FSE T2-weighted imaging | Sagittal and oblique axiala | Measure maximal tumor dimension Determine tumor extent Measure distance from tumor to internal cervical os (if fertility is desired) |

| Small-FOV DWI (e.g., multishot DWI with MUSE) | Oblique axialb | Determine tumor extent in conjunction with T2-weighted imaging |

| 3D GRE DCE-MRI (optional)c | Sagittal | Evaluate tumor perfusion as a surrogate marker of tumor hypoxia |

Note—LN = lymph node, FSE = fast spin-echo, GRE = gradient-recalled echo, MUSE = multiplexed sensitivity encoding, DCE-MRI = dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI.

Sagittal and oblique axial planes are required; additional planes are optional.

The orientation, FOV, and slice thickness of the small-FOV DWI sequence should match those of the oblique axial small-FOV FSE T2-weighted imaging sequence.

Primarily used as a research tool.

Small-FOV high-resolution fast spin-echo (FSE) T2-weighted imaging is the cornerstone of morphologic assessment (Table 1). We obtain 2D T2-weighted images in two orthogonal planes (sagittal and oblique axial). The oblique axial plane is obtained perpendicular to the cervix, yielding a doughnutlike view of the cervix and facilitating detection of parametrial invasion (PMI) [22] (Figs. 3 and 4). The use of 3D T2-weighted imaging provides a potential alternative to 2D T2-weighted imaging, offering shorter acquisition time and retrospective multiplanar image reconstruction. We prefer 2D T2-weighted imaging because 3D T2-weighted imaging can be limited by reduced T2 contrast, lower in-plane spatial resolution, greater motion artifacts from longer acquisitions, and more variations in SNR and image contrast owing to B1 inhomogeneity [23]. One study also reported reduced sharpness of cervical tumor margin for 3D T2-weighted imaging [24].

Fig. 4—

35-year-old woman with newly diagnosed invasive squamous cell cervical carcinoma and desire for fertility preservation.

A and B, Sagittal (A) and oblique axial (B) T2-weighted images show 1.2-cm exophytic intermediatesignal cervix-confined tumor (arrows) consistent with International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics stage IB1 disease. Tumor is located away from internal cervical os (arrowhead, A).

C, Axial fused image of T2-weighted image and DWI shows restricted diffusion within tumor (arrow).

D, Sagittal T2-weighted image obtained after radical trachelectomy shows anastomosis (arrows) between remaining uterus and vagina.

DWI is integral to the MRI examination (Table 1). Combined with T2-weighted imaging, DWI facilitates evaluation of tumor size and extent (e.g., PMI and LN metastases). DWI should use the same plane, FOV, and slice thickness as small-FOV T2-weighted imaging to allow side-by-side interpretation and image fusion. We advise the use of reduced-distortion DWI techniques to reduce image degradation by rectal gas [25–28]. Multishot DWI with multiplexed sensitivity encoding (MUSE) and readout-segmented DWI reduce geometric distortion by shortening the echo-train length, whereas reduced-FOV DWI reduces geometric distortion by limiting the FOV in the phase-encoding direction. We acquire DWI in the oblique axial plane with b values of 50 and 800–1000 s/mm2. DWI with b values great than 1000 s/mm2 can be synthesized, maintaining high SNR [29].

Contrast-enhanced imaging, including dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI (DCE-MRI), is optional and primarily investigational. DCE-MRI is a potential surrogate to assess hypoxia, which has been linked to aggressive tumor biology and radiation therapy resistance [30]. Poor perfusion (presumed hypoxia) during CCRT may adversely impact radiation response, tumor control, and survival, whereas improved perfusion may indicate better prognosis, although these results require validation [31]. In one study, persistent early avid tumor enhancement relative to myometrium after CCRT was associated with incomplete response, but the results are limited by variable timing of posttreatment MRI [32]. At present, the absence of standardized or validated methods for acquisition and analysis limits the clinical utility of DCE-MRI [31].

FDG PET/CT and FDG PET/MRI

Before undergoing FDG PET/CT, patients are advised to avoid strenuous exercise for 24 hours and to fast for 4–6 hours to ensure a serum glucose level of less than 200 mg/dL. To reduce attenuation artifacts within the pelvis, patients are instructed to stay well hydrated and to empty their bladder before undergoing scanning. Oral contrast material may help delineate the bowel. The companion CT examination may be acquired either as low-dose CT for attenuation correction and lesion localization or as contrast-enhanced diagnostic CT. FDG PET/CT has a total acquisition time of 20–25 minutes.

FDG PET/MRI uses the same patient preparation as that used for FDG PET/CT. Whole-body coverage is usually obtained with spin-echo T2-weighted imaging, unenhanced gradient-echo T1-weighted imaging, and DWI with b values of 50 and 800–1000 s/mm2. Focused FDG PET/MRI through the pelvis combines the previously described MRI sequences for tailored CC evaluation with simultaneous PET acquisition.

Key Elements of Initial Staging With MRI and FDG PET

Structured reporting facilitates creation of clear and clinically relevant reports in patients with CC [16] (Tables 2 and 3).

TABLE 2:

Key Elements of the MRI Structured Report for Initial Staging and Restaging of Cervical Cancer

| Site | Elements to Report |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Primary tumor | Tumor: absent or present • If present, then tumor’s greatest dimension and if tumor is entirely endophytic or entirely exophytic Uterine corpus involvement: absent or present If fertility is desired, then distance from tumor to internal os |

| Adjacent structures | Vaginal involvement: absent or present • If present, then if tumor involves upper two-thirds or lower one-third of vagina Parametrial involvement: absent or present • If present, then if involvement is right, left, or bilateral Hydronephrosis: absent or present • If present, then severity and if hydronephrosis is right, left, or bilateral Pelvic sidewall involvement: absent or present • If present, then if involvement is right, left, or bilateral Urinary bladder mucosal involvement: absent or present Rectal mucosal involvement: absent or present |

| LNs | Pelvic LN enlargement: absent or present • If present, then location (obturator, external iliac, internal iliac, common iliac, or presacral) and if LN enlargement is right, left, or bilateral Paraaortic LN enlargement: absent or present • If present, then specific location |

Note—LN = lymph node.

TABLE 3:

Key Elements of the FDG PET Structured Report for Initial Staging and Restaging of Cervical Cancer

| Site | Elements to Report |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Primary tumor | Tumor: absent or present • If present, then location of activity and whether activity extends to adjacent structures (if possible to assess)a SUVmax |

| LNs | Pelvic LN enlargement: absent or present • If present, then location (obturator, external iliac, internal iliac, common iliac, or presacral) and if LN enlargement is right, left, or bilateral Paraaortic LN enlargement: absent or present • If present, then specific location SUVmax Size on CT (if possible to assess) |

| Metastases | Metastases: absent or present • If present, then location(s) SUVmax |

Note—LN = lymph node.

For this assessment, it is helpful to view PET/CT images on wide window levels.

MRI: Local Extent

Tumor size—

Figure 3 illustrates normal uterine and cervical anatomy. CC shows intermediate-to-high SI on T2-weighted imaging and high SI on high-b-value DWI, contrasting with low-SI fibrous cervical stroma (Figs. 4 and 5).

Fig. 5—

Features on T2-weighted MRI that are useful for determining presence of parametrial invasion of cervical cancer (yellow).

A, Illustration shows partial- or full-thickness cervical stromal invasion, which is not sufficient to diagnose parametrial invasion.

B, Illustrations show parametrial invasion, which is indicated by full-thickness stromal invasion and either nodular (left) or spiculated (right) interface with parametrium without or with parametrial vessel (red and blue, right panel) encasement.

A key question during image interpretation is whether the tumor is confined to the cervix (stage I) or upper vagina (stage IIA) or has spread to the parametrium and beyond (stage ≥ IIB). If disease is limited to the cervix or upper vagina, then the maximal tumor size is essential in determining the FIGO stage and selecting optimal primary treatment (Figs. 1 and 2). Size is more accurate based on MRI than physical examination, using surgical pathology as reference [33]. Tumor should be measured in the plane that best captures its greatest dimension. The major pitfall in tumor measurement is peritumoral edema or fibrosis, which may obscure tumor margins on T2-weighted imaging. DWI may serve as a problem-solving tool because the tumor, but not peritumoral edema or fibrosis, is expected to show restricted diffusion [16, 22, 34, 35]. We recommend primarily using T2-weighted imaging to measure maximal tumor size and using DWI as needed for further guidance [36].

Parametrial invasion—

CCRT is the optimal primary treatment approach in patients with PMI. Conventional MRI has pooled sensitivity and specificity for PMI of 71–75% and 91–92%, respectively [37, 38]. The presence of an intact low-SI rim of cervical stroma around the tumor on T2-weighted imaging excludes PMI. Full-thickness cervical stroma invasion does not necessarily signify PMI [16, 39]. PMI should be diagnosed in the presence of full-thickness cervical stroma invasion (i.e., full-thickness replacement of low-SI cervical stroma by indeterminate- to high-SI tumor with diffusion restriction) and a nodular or spiculated tumor-to-parametrium interface, with possible parametrial vessel encasement [16, 40] (Figs. 5 and 6). The specificity for PMI is higher for the combination of T2-weighted imaging and DWI (97–99%) than for T2-weighted imaging alone (85–89%), without a change in sensitivity (68–81% for the combination of T2-weighted imaging and DWI and for T2-weighted imaging alone) [41]. This difference may reflect the role of the combination of DWI and T2-weighted imaging in differentiating the tumor within the parametrium from peritumoral edema or fibrosis [16, 39, 40].

Fig. 6—

Evaluation of cervical stroma invasion and parametrial invasion (PMI).

A, 46-year-old woman with invasive squamous cell carcinoma. Oblique axial T2-weighted image shows 3.3-cm tumor with full-thickness cervical stromal invasion but smooth outer contour (arrow). Surgical pathology revealed near-full-thickness (16 of 17 mm) cervical stromal invasion and lack of PMI. Findings are consistent with International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) stage IB2 disease.

B and C, 52-year-old woman with invasive squamous cell carcinoma. Oblique axial T2-weighted image (B) and axial fused image (T2-weighted imaging and DWI) (C) show full-thickness cervical stromal invasion and nodular outer contour (arrow, B) indicative of PMI. Findings are consistent with FIGO stage IIB disease.

Vaginal involvement—

A horizontal line at the level of the bladder neck divides the vagina into the upper two-thirds and lower one-third [40] (Fig. 3). Upper vaginal involvement indicates stage IIA disease, whereas lower vaginal involvement signifies stage IIIA disease. The vagina is considered involved when intermediate- to high-SI tumor disrupts low-SI vaginal wall on T2-weighted imaging [40].

Pelvic sidewall invasion—

Hydronephrosis, a nonfunctioning kidney, or pelvic sidewall involvement indicates stage IIIB disease. Pelvic sidewall invasion should be suspected in the presence of hydronephrosis or a distance of 3 mm or less from the tumor to either pelvic muscles or iliac vessels [40].

Pelvic organ involvement—

Biopsy-proven bladder or rectal mucosal invasion is classified as stage IVA disease. Mucosal invasion should be suspected on T2-weighted imaging when intermediate- to high-SI tumor disrupts low-SI wall and extends into edematous high-SI mucosa or lumen [42] (Fig. 7). All available images should be carefully reviewed for localized bullous edema, which may be the first sign of wall invasion. Bullous edema alone is not sufficient to diagnose stage IVA disease; this finding is nonspecific and may be also observed in inflammation or infection [6, 7].

Fig. 7—

64-year-old woman with invasive squamous cell carcinoma.

A and B, Sagittal (A) and oblique axial (B) T2-weighted images show large ill-defined cervical tumor (arrow) with involvement of lower one-third of vagina and urinary bladder lumen. Few areas of bullous edema are present within mucosa. In A, arrow shows tumor. Arrowhead in B shows bullous edema. Findings are consistent with International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics stage IVA disease.

An uninterrupted fat plane, minor loss of fat plane, and abutment or indentation of the bladder or rectum by tumor with preserved low-SI wall on T2-weighted imaging are useful signs to exclude mucosal invasion and alleviate the need for invasive procedures (e.g., cystoscopy or endoscopy) [42].

MRI and FDG PET: Regional and Distant Extent

Lymph node assessment—

CC first spreads to obturator, internal or external iliac, and presacral LNs, followed by common iliac and paraaortic LNs [43]. Paraaortic LN metastases are rare without pelvic LN metastases [44, 45]. Conventional MRI is specific but is moderately sensitive for LN metastases, having pooled sensitivity of 51–57% and specificity of 90–93% [37, 38, 46]. These values reflect performance based on the current primary criterion for the diagnosis of a LN metastasis: a LN short-axis diameter of 10 mm or greater (Figs. 8 and 9). Useful ancillary features, regardless of LN size, include heterogeneous SI, SI similar to SI of the primary tumor, round shape, spiculated margins, and the presence of necrosis (Fig. 8). High-b-value DWI increases LN conspicuity because of high SI of LNs in comparison with low SI of background. Mean ADC values are lower for LN metastases than for benign LNs [47–49]. Several studies have reported improved accuracy for diagnosing LN metastases by DWI than by conventional MRI, suggesting that mean ADC values are more accurate than short-axis diameter [47–49]. Nevertheless, overlap in mean ADC values between malignant and benign LNs limits clinical application.

Fig. 8—

28-year-old woman with invasive squamous cell carcinoma of cervix.

A, Sagittal T2-weighted image shows large exophytic intermediate-signal tumor (T).

B, Oblique axial T2-weighted image shows enlarged external bilateral iliac lymph nodes (LNs) (arrows) with signal intensity similar to that of primary cervical tumor.

C, Oblique axial high-b-value DW image shows enlarged external bilateral iliac LNs (arrows) with high signal intensity. 28-year-old woman with invasive squamous cell carcinoma of cervix.

D and E, Axial fused images from FDG PET/CT show FDG-avid primary tumor (T, D) and bilateral external iliac LNs (arrows, D) and left common iliac LN (arrow, E). Findings are consistent with International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics stage IIIC disease.

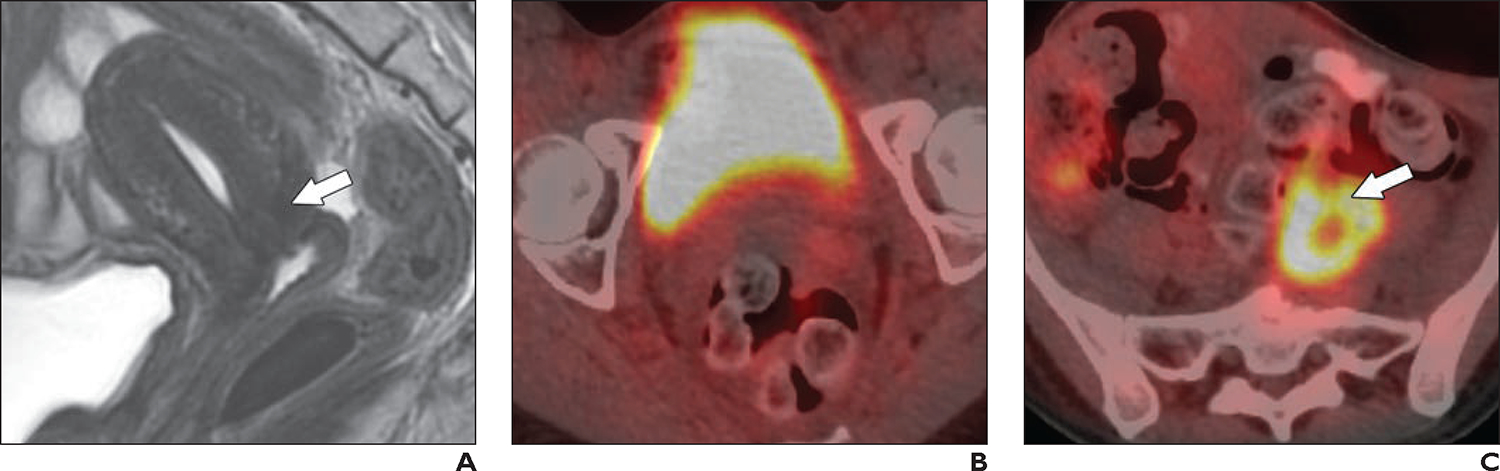

Fig. 9—

53-year-old woman with newly diagnosed adenocarcinoma of cervix.

A, Axial T2-weighted image shows small right external iliac lymph node (LN) (arrow) measuring 6 mm in short axis.

B, Coronal fused image from FDG PET/CT shows FDG avidity within LN (arrow). Findings are consistent with International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics stage IIIC1 disease.

Patients with stage IB3 or greater disease have increased prevalence of LN and distant metastases and benefit from undergoing FDG PET. A meta-analysis reported that, in patients with locally advanced CC, FDG PET has pooled sensitivity and specificity of 88% and 93%, respectively, for pelvic LN metastases and of 40% and 93%, respectively, for paraaortic LN metastases [50] (Fig. 8). FDG PET may show false-positive findings due to reactive LNs [51]. False-negative findings for paraaortic LN metastases, attributed to micrometastases, are common [52]. Given this limitation, debate is ongoing regarding the role of paraaortic LN dissection in patients with suspected pelvic (especially, common iliac) LN metastases but absent paraaortic LN metastases on FDG PET [53–56].

Distant metastases—

Approximately 15% of patients with CC present with distant metastases, with the most common sites being the lungs, bones, liver, and brain [57]. LN metastases beyond pelvic and paraaortic regions are also considered stage IVB disease. The optimal modality to detect distant metastases is FDG PET. A prospective clinical trial reported a sensitivity of 55%, specificity of 98%, PPV of 79%, and NPV of 93% for distance metastases [58]. Suspected metastatic sites on FDG PET should be confirmed by biopsy.

Special Considerations

Fertility-sparing assessment—

MRI is essential to confirm patient eligibility for fertility-sparing management. In addition to previously noted histologic criteria, the tumor on imaging should be confined to the cervix and measure 2 cm or less (stage ≤ IB1) [11]. To achieve optimal oncologic and reproductive outcomes, distance between the tumor and internal os should be 1 cm or greater [10]. The location of the internal os is identified by the site of narrowing between the endocervical canal and endometrial cavity in the sagittal plane and by the entry of uterine vessels in the oblique axial plane (Figs. 3 and 4). Conventional MRI has pooled sensitivity of 86% and specificity of 97% for detection of internal os involvement [38]. Review of both T2-weighted imaging and DWI facilitates assessment of tumor size and extent, including tumor-to–internal os distance [34, 59].

Cervical adenocarcinoma versus endometrial adenocarcinoma—

CC and endometrial cancer have distinct management [60]. MRI may help distinguish cervical versus endometrial origin of adenocarcinoma on the rare occasions that histopathologic evaluation is inconclusive. Findings that suggest a cervical origin include cervical location of the tumor’s epicenter (i.e., > 50% of tumor bulk in cervix), round shape, early avid and late rim enhancement, retained endometrial secretions, cervical stroma invasion, and PMI [60, 61]. Findings that suggest endometrial origin include endometrial location of the tumor’s epicenter, endometrial thickening, oblong shape, myometrial invasion, and an ovarian mass [60, 61].

Unusual histologies—

Rare histologic subtypes of CC include neuroendocrine carcinoma (NEC), gastric-type adenocarcinoma (GTA), and cervical lymphoma.

Neuroendocrine carcinoma—

NEC accounts for 1.0–1.5% of CC. It is an aggressive tumor with propensity for distant metastases. The most prevalent subtype is the small cell variant [62]. MRI features are nonspecific and include homogeneous SI on T2-weighted imaging, diffusion restriction, and homogeneous enhancement. Multimodality treatment is reserved for early-stage tumors, whereas chemotherapy is recommended for advanced disease [62].

Gastric-type adenocarcinoma—

GTA is HPV-related and accounts for 10% of cervical adenocarcinomas. Approximately 10% of patients with GTA have Peutz-Jeghers syndrome [63, 64]. GTA is a mucinous tumor with variable differentiation. If the tumor shows benign-appearing endocervical glands extending deeply into the cervical stroma, then the tumor is described as minimal-deviation adenocarcinoma (i.e., adenoma malignum). Regardless of differentiation, GTA is highly aggressive and carries poor prognosis due to early peritoneal dissemination and chemoresistance. On MRI, GTA appears as a solid endocervical mass with variable multicystic components extending deep into the cervical stroma (Fig. 10). The main entities in the differential diagnosis are nabothian cysts (including tunnel clusters) and endocervical glandular hyperplasia. In comparison with nabothian cysts, GTA often presents with copious watery discharge and abnormal vaginal bleeding, is associated with P eutz-Jeghers syndrome, and shows solid enhancing components [65]. Diagnosis requires cone biopsy.

Fig. 10—

42-year-old woman who presented with clear vaginal discharge and was subsequently diagnosed with International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics stage IB3 gastric-type adenocarcinoma of cervix.

A, Sagittal T2-weighted image shows 6-cm infiltrative partly endophytic mass (arrow) replacing entire cervix; mass shows intermediate signal intensity and has internal microcysts (arrowhead).

B, Sagittal fat-saturated contrast-enhanced T1-weighted image shows enhancement of mass (arrow).

Cervical lymphoma—

Primary cervical lymphoma is rare (< 1% of CC) compared with secondary cervical involvement by systemic lymphoma [66]. Primary tumors are usually large at presentation because they spare cervical epithelium and are not readily detected by routine screening. Diagnosis requires cone biopsy. Non-Hodgkin lymphoma is the most common histology [66]. Primary cervical lymphoma is favored when the cervix is the only or predominant disease site, whereas secondary involvement is favored in the presence of systemic disease [66]. MRI typically shows a large homogeneous intermediate- to high-SI mass on T2-weighted imaging with diffuse cervical enlargement, spared cervical mucosa, preserved architecture, restricted diffusion, and diffuse enhancement without necrosis. Adjacent structures including the vagina, parametria, bladder, and uterine corpus may be involved in patients with advanced disease.

Role of MRI and FDG PET in Radiotherapy Planning

Bulky tumors measuring greater than 4 cm that are confined to the cervix and upper vagina (i.e., stages IB3 and IIA2) and locally advanced tumors (i.e., stages IIB–IVA) are managed with concurrent EBRT and chemotherapy followed by image-guided brachytherapy to optimize local control [11, 14, 15]. Intensity-modulated radiotherapy (IMRT) is the preferred method for EBRT given its more conformal dose distribution with maximal sparing of organs at risk (OARs) (i.e., uninvolved vagina, bladder, rectum, sigmoid colon, and small bowel). The target volume for IMRT includes the primary tumor, adjacent structures (parametria, uterine corpus, vagina [with 2-cm tumor-free inferior margin]), and pelvic LNs. If FDG PET suggests paraaortic or high pelvic LN metastases, then the target volume also includes paraaortic LN basins up to the renal vessels.

When available, MRI is the preferred method for image-guided adaptive brachytherapy given its superior delineation of residual tumor, parametrial and pelvic sidewall involvement, and OARs [67, 68]. MRI-based image-guided adaptive brachytherapy provides effective local control with limited severe morbidity [67]. Post-EBRT prebrachytherapy MRI (using the same protocol as that used for the initial staging) can help determine residual tumor burden (i.e., size and extent) and guide selection of the appropriate intracavitary applicator. The appropriate applicator is essential to maximize dose to the high-risk clinical target volume (i.e., any palpable or MRI-visible residual tumor and the entire cervix) while minimizing dose to OARs. In patients with eccentric tumors or extensive PMI, prebrachytherapy MRI allows determination of the need for and, if necessary, guides planning of interstitial needle placement to adequately cover the high-risk clinical target volume [69].

When available, in-room MRI is useful for real-time guidance of intracavitary applicator placement and interstitial needle insertion or adjustment [70]. If in-room MRI is unavailable, then MRI may be performed after implant placement and immediately before brachytherapy to confirm implant position as well as to assist treatment planning and simulation. The typical protocol includes 2D FSE T2-weighted imaging in three orthogonal planes angled relative to the tandem. Multiplanar reformatting is facilitated by acquisition of 3D FSE T2-weighted imaging [68, 71].

Table 4 details key elements of structured reporting for postimplant prebrachytherapy MRI.

TABLE 4:

Key Elements of the MRI Structured Report for Cervical Cancer Evaluation in the Postimplant Prebrachytherapy Setting

| Object or Site | Elements to Report |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Brachytherapy applicator | Intrauterine tandem: • Whether correctly positioned within endometrial cavity with tip in the fundus • Whether cervical stop (plastic marker) abuts external cervical os Intravaginal ovoids, intravaginal ring, or vaginal cylinder: • Whether correctly positioned in the upper vagina, displacing vaginal wall away from the radiation source Perforation: absent or present • If present, then if perforation involves uterine fundus, posterior uterus, cervix, or posterior vaginal fornix |

| Interstitial needle(s) | Location of needle(s) relative to the tumor: within the tumor or outside of the tumor No. of needles Nontarget insertion (e.g., insertion in the urinary bladder or rectum): absent or present • If present, then location |

| Foley catheter | Foley catheter: absent or present • If present, then whether correctly located in urinary bladder |

| Vaginal packing | Vaginal packing: absent or present • If present, then whether correctly located within vagina |

| Primary tumor | Tumor: absent or present • If present, then tumor's size in 3D with applicator and vaginal packing in place |

| Adjacent structures | Vaginal involvement: absent or present • If present, then if tumor involves upper two-thirds or lower one-third of vagina Parametrial involvement: absent or present • If present, then if involvement is right, left, or bilateral Hydronephrosis: absent or present • If present, then severity and if hydronephrosis is right, left, or bilateral Pelvic sidewall involvement: absent or present • If present, then if involvement is right, left, or bilateral Urinary bladder mucosal involvement: absent or present Rectal mucosal involvement: absent or present |

| LNs | Pelvic LN enlargement: absent or present (right, left, bilateral) • If present, location (obturator, external iliac, internal iliac, common iliac, presacral) If imaged, paraaortic LN enlargement: absent or present • If present, specific location |

Predicting and Assessing Concurrent Chemoradiotherapy Response: Role and Limitations of MRI and FDG PET

An accepted imaging approach to reliably predict CCRT response is presently lacking, but research is ongoing. Pretreatment MRI findings, including tumor size and mean ADC, are not useful to predict CCRT response [72–75]. However, tumor regression rate, mean ADC during treatment, and change in mean ADC during treatment may be informative [72, 73, 76]. For example, a meta-analysis reported a 49.7% increase in mean ADC among responders versus 19.7% in nonresponders within 3 weeks of treatment [74].

Pretreatment FDG PET may help predict CCRT response. A meta-analysis found that higher primary tumor SUVmax was associated with shorter survival in locally advanced CC. Routine clinical use of primary tumor SUVmax remains limited given the lack of universal cutoff values. The role of SUVmax of LN metastases, total lesion glycolysis, and metabolic tumor volume requires further study [77].

Posttreatment MRI is typically performed 3–6 months after CCRT. However, posttreatment changes (e.g., edema, inflammation) can persist for 6–9 months after CCRT. Interpretation of T2-weighted imaging is challenging because both residual tumor and posttreatment edema show intermediate-to-high SI [78, 79]. Reconstitution of the low-SI cervical stroma on T2-weighted imaging after treatment indicates complete response (Fig. 11). The addition of DWI to T2-weighted imaging may help differentiate residual or recurrent tumor from postradiation edema, inflammation, and fibrosis, which should not show restricted diffusion. A multicenter prospective study reported that the combination of T2-weighted imaging and DWI improved specificity for residual tumor (89–95%) in comparison with T2-weighted imaging alone (53–89%) with unchanged sensitivity [79].

Fig. 11—

28-year-old woman with invasive squamous cell carcinoma of cervix (same patient as in Fig. 8).

A, Sagittal T2-weighted image obtained 5 months after definitive chemoradiotherapy shows reconstitution of hypointense cervical stroma (arrow), indicating absence of tumor.

B, Axial fused image from FDG PET/CT shows resolution of FDG avidity within cervical tumor (compared with Fig. 8D).

C, Axial fused image from FDG PET/CT shows increased FDG uptake in left common iliac lymph node (arrow) (compared with Fig. 8E); this finding is consistent with persistent metastatic disease.

FDG PET is also typically performed 3–6 months after CCRT and indicates both treatment response and prognosis (Fig. 11). FDG PET findings can be classified by visual assessment as complete response (resolution of FDG avidity), partial response (any residual avidity), and progressive disease (new foci of avidity), corresponding with progression-free survival of 78%, 33%, and 0%, respectively. This assessment allows timely salvage treatment in patients with partial response or progressive disease [80]. Positive findings on posttreatment FDG PET should be confirmed with biopsy because false-positives are common, particularly in patients with partial response [81].

Posttreatment Surveillance and Management of Tumor Recurrence

The most important predictors of recurrence are tumor stage (including LN status), lymphovascular space invasion (LVSI), and treatment response [82]. Recurrence rate is up to 22% for stages IB and IIA and up to 64% for stages IIB–IVA [83]. Most recurrences occur within 2 years of initial treatment; 40% occur within the 1st year [83]. Common sites of recurrence include the vaginal vault, cervix (after CCRT), LN basins, and distant sites [83].

The role of imaging in CC surveillance remains uncertain. Post-treatment surveillance is currently informed by stage, LVSI, primary treatment, and clinical findings [11, 84]. After standard radical surgery, patients are reimaged if there is clinical concern for recurrence. After fertility-sparing surgery, patients are reimaged with pelvic MRI at 6 months and then annually for 2–3 years. After definitive CCRT, patients are reimaged by FDG PET and MRI at 3–6 months. All patients should undergo further workup in the presence of clinical suspicion for recurrence (e.g., new symptoms).

After treatment, persistent disease is defined as tumor occurring after a tumor-free period of less than 6 months, whereas recurrent disease is defined as tumor occurring after a tumor-free period of 6 months or longer. Patients who underwent surgery or who have recurrence outside of the radiation field may undergo salvage CCRT. Patients with central recurrence in the irradiated region may be offered radical hysterectomy (for tumors < 2 cm) or pelvic exenteration in the absence of LN or distant metastases [11]. Radiologists should be familiar with selection for pelvic exenteration [85, 86].

Restaging MRI is useful to detect residual or recurrent disease and to evaluate locoregional extent, with pooled sensitivity of 73% and specificity of 96% [87]. The protocol is similar to that in the initial staging and posttreatment settings except that the imaging planes are adjusted in the posttreatment setting if the patient underwent prior hysterectomy. Recurrent tumor shows MRI features similar to those of primary lesions, including intermediate-to-high SI on T2-weighted imaging, high SI on DWI, and low ADC. In contrast, the normal vaginal cuff and radiation-induced fibrosis show low SI on all sequences.

Restaging FDG PET has a diagnostic performance for detection of locally residual or recurrent disease that is similar to that of MRI, with pooled sensitivity of 86% and specificity of 95% [87]. However, FDG PET excels at detecting LN and distant metastases (sensitivity, 97%; specificity, 99%) compared with MRI (sensitivity, 31%; specificity, 98%) [87].

Radiologists should be familiar with expected posttreatment appearances, relevant history (including ovarian transposition), and posttreatment complications (e.g., insufficiency fractures, fistulas) to accurately differentiate these complications from residual or recurrent disease [88, 89].

Future Directions

PET/MRI

Hybrid FDG PET/MRI is an emerging technology that combines excellent soft-tissue contrast of conventional MRI, functional data from DWI and DCE-MRI, and molecular information from PET. It potentially offers simultaneous quantitative and qualitative tumor assessment in a single imaging session [90]. Nevertheless, superiority of FDG PET/MRI in comparison with the combination of separate pelvic MRI and FDG PET/CT examinations, beyond the convenience of a single imaging session, requires validation [91]. Optimal solutions for attenuation and motion correction are areas of active research [90]. Widespread implementation of FDG PET/MRI is hindered by the modality’s high cost and need for advanced technical expertise.

PET Tracers

Besides FDG, several tracers are of interest in CC. First, NECs overexpress somatostatin receptors and thus may be imaged with somatostatin receptor PET agents (e.g., 68Ga-DOTATATE) to improve locoregional and distant staging [92]. Second, hypoxia PET may noninvasively measure hypoxia across space and time. Two main types of hypoxia PET tracers are fluorine-labeled nitroimidazoles (e.g., 18F-fluoromisonidazole [FMISO]) and copper-labeled diacetyl-bis(N4-methylthiosemicarbazone) (ATSM) analogs (e.g., 64Cu-ATSM) [93]. The ability of hypoxia PET to alter treatment plans and improve CC outcomes is not yet established [93]. Third, PET of cell proliferation using radiolabeled DNA precursors (e.g., 3-deoxy-3-[18F] fluorothymidine [FLT]) may facilitate bone marrow–sparing strategies during CCRT [94]. Finally, 68Ga-fibroblast activation protein inhibitor PET allows imaging of desmoplastic reactions in various tumors; its role in CC is under investigation [95].

Artificial Intelligence

Artificial intelligence (machine and deep learning approaches) is currently a major focus of investigation for predicting CC biology and clinical outcomes [96]. Studies have devised machine learning algorithms using findings from FDG PET/CT and/or MRI to predict prognostic CC endpoints such as tumor histology, FIGO stage, depth of cervical stroma invasion, LVSI, LN metastases, treatment response, recurrence, and overall survival [97–100]. Although this growing body of research has shown the feasibility of radiomic signatures to provide useful information for potentially guiding patient management, current studies lack the generalizability and reproducibility required for clinical deployment. An important limitation is the paucity of prospective externally validated studies based on large diverse datasets. Efforts in the gynecologic imaging research community should be directed toward conducting multiinstitutional studies and enlarging publicly available datasets to increase the heterogeneity of patients and image acquisition techniques, thereby improving the generalizability of artificial intelligence models in clinical practice.

Highlights.

MRI and FDG PET aid in initial staging, primary treatment selection and planning, response assessment, and restaging of recurrence in patients with cervical cancer.

MRI is essential to confirm patient eligibility before planned fertility-sparing treatment of cervical cancer.

Structured reporting facilitates creation of clear and clinically relevant reports in patients with cervical cancer.

Acknowledgment

We thank Joanne Chin for her editorial assistance with this manuscript.

Y. Lakhman consults for Calyx Clinical Trial Solutions. S. Nougaret is supported by European Research Council starting grant 10107710. The remaining authors declare that there are no other disclosures relevant to the subject matter of this article.

Supported in part by NIH/National Cancer Institute Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA008748.

Footnotes

Provenance and review: Solicited; externally peer reviewed.

Peer reviewers: Roopa Ram, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences; Kedar Sharbidre, University of Alabama at Birmingham; Soleen Ghafoor, University Hospital Zurich; additional individual(s) who chose not to disclose their identity.

References

- 1.Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2021; 71:209–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stelzle D, Tanaka LF, Lee KK, et al. Estimates of the global burden of cervical cancer associated with HIV. Lancet Glob Health 2021; 9:e161–e169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lei J, Ploner A, Elfström KM, et al. HPV vaccination and the risk of invasive cervical cancer. N Engl J Med 2020; 383:1340–1348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.WHO website. Cervical cancer. www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cervical-cancer. Published Feb 22, 2022. Accessed Nov 7, 2022

- 5.Parra-Herran C Cervix: WHO classification. PathologyOutlines.com website. www.pathologyoutlines.com/topic/cervixWHO.html. Last updated May 28, 2021. Accessed Nov 7, 2022

- 6.Bhatla N, Aoki D, Sharma DN, Sankaranarayanan R. Cancer of the cervix uteri. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2018; 143(suppl 2):22–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.[No authors listed]. Corrigendum to “Revised FIGO staging for carcinoma of the cervix uteri” [Int J Gynecol Obstet 145(2019) 129–135]. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2019; 147:279–280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Qin Y, Peng Z, Lou J, Liu H, Deng F, Zheng Y. Discrepancies between clinical staging and pathological findings of operable cervical carcinoma with stage IB–IIB: a retrospective analysis of 818 patients. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2009; 49:542–544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim SM, Choi HS, Byun JS. Overall 5-year survival rate and prognostic factors in patients with stage IB and IIA cervical cancer treated by radical hysterectomy and pelvic lymph node dissection. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2000; 10:305–312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bentivegna E, Gouy S, Maulard A, Chargari C, Leary A, Morice P. Oncological outcomes after fertility-sparing surgery for cervical cancer: a systematic review. Lancet Oncol 2016; 17:e240–e253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abu-Rustum NR, Yashar CM, Arend R, et al. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology (NCCN Guidelines): cervical cancer—version 1.2023. www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/cervical.pdf. Published Apr 28, 2023. Accessed Aug 12, 2023

- 12.Marth C, Landoni F, Mahner S, McCormack M, Gonzalez-Martin A, Colombo N; ESMO Guidelines Committee. Cervical cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol 2018; 29(suppl 4):iv262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cormier B, Diaz JP, Shih K, et al. Establishing a sentinel lymph node mapping algorithm for the treatment of early cervical cancer. Gynecol Oncol 2011; 122:275–280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chino J, Annunziata CM, Beriwal S, et al. The ASTRO clinical practice guidelines in cervical cancer: optimizing radiation therapy for improved outcomes. Gynecol Oncol 2020; 159:607–610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cibula D, Pötter R, Planchamp F, et al. The European Society of Gynaecological Oncology/European Society for Radiotherapy and Oncology/European Society of Pathology guidelines for the management of patients with cervical cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2018; 28:641–655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Manganaro L, Lakhman Y, Bharwani N, et al. Staging, recurrence and follow-up of uterine cervical cancer using MRI: updated guidelines of the European Society of Urogenital Radiology after revised FIGO staging 2018. Eur Radiol 2021; 31:7802–7816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jayaprakasam VS, Javed-Tayyab S, Gangai N, et al. Does microenema administration improve the quality of DWI sequences in rectal MRI? Abdom Radiol (NY) 2021; 46:858–866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sheikh-Sarraf M, Nougaret S, Forstner R, Kubik-Huch RA. Patient preparation and image quality in female pelvic MRI: recommendations revisited. Eur Radiol 2020; 30:5374–5383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gutzeit A, Binkert CA, Koh DM, et al. Evaluation of the anti-peristaltic effect of glucagon and hyoscine on the small bowel: comparison of intravenous and intramuscular drug administration. Eur Radiol 2012; 22:1186–1194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wolters Kluwer website. Drug decision support from Wolters Kluwer. www.wolterskluwer.com/en/know/drug-decision-support-solutions. Accessed Nov 7, 2022

- 21.Unlu E, Virarkar M, Rao S, Sun J, Bhosale P. Assessment of the effectiveness of the vaginal contrast media in magnetic resonance imaging for detection of pelvic pathologies: a meta-analysis. J Comput Assist Tomogr 2020; 44:436–442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.deSouza NM, Rockall A, Freeman S. Functional MR imaging in gynecologic cancer. Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am 2016; 24:205–222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lim KK, Noe G, Hornsey E, Lim RP. Clinical applications of 3D T2-weighted MRI in pelvic imaging. Abdom Imaging 2014; 39:1052–1062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shin YR, Rha SE, Choi BG, Oh SN, Park MY, Byun JY. Uterine cervical carcinoma: a comparison of two- and three-dimensional T2-weighted turbo spin-echo MR imaging at 3.0 T for image quality and local-regional staging. Eur Radiol 2013; 23:1150–1157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lawrence EM, Zhang Y, Starekova J, et al. Reduced field-of-view and multi-shot DWI acquisition techniques: prospective evaluation of image quality and distortion reduction in prostate cancer imaging. Magn Reson Imaging 2022; 93:108–114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.An H, Ma X, Pan Z, Guo H, Lee EYP. Qualitative and quantitative comparison of image quality between single-shot echo-planar and interleaved multi-shot echo-planar diffusion-weighted imaging in female pelvis. Eur Radiol 2020; 30:1876–1884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen M, Feng C, Wang Q, et al. Comparison of reduced field-of-view diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) and conventional DWI techniques in the assessment of cervical carcinoma at 3.0T: image quality and FIGO staging. Eur J Radiol 2021; 137:109557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hosseiny M, Sung KH, Felker E, et al. Read-out segmented echo planar imaging with two-dimensional navigator correction (RESOLVE): an alternative sequence to improve image quality on diffusion-weighted imaging of prostate. Br J Radiol 2022; 95:20211165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Higaki T, Nakamura Y, Tatsugami F, et al. Introduction to the technical aspects of computed diffusion-weighted imaging for radiologists. RadioGraphics 2018; 38:1131–1144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Walsh JC, Lebedev A, Aten E, Madsen K, Marciano L, Kolb HC. The clinical importance of assessing tumor hypoxia: relationship of tumor hypoxia to prognosis and therapeutic opportunities. Antioxid Redox Signal 2014; 21:1516–1554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Matani H, Patel AK, Horne ZD, Beriwal S. Utilization of functional MRI in the diagnosis and management of cervical cancer. Front Oncol 2022; 12:1030967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jalaguier-Coudray A, Villard-Mahjoub R, Delouche A, et al. Value of dynamic contrast-enhanced and diffusion-weighted MR imaging in the detection of pathologic complete response in cervical cancer after neoadjuvant therapy: a retrospective observational study. Radiology 2017; 284:432–442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mitchell DG, Snyder B, Coakley F, et al. Early invasive cervical cancer: tumor delineation by magnetic resonance imaging, computed tomography, and clinical examination, verified by pathologic results, in the ACRIN 6651/GOG 183 Intergroup Study. J Clin Oncol 2006; 24:5687–5694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Downey K, Attygalle AD, Morgan VA, et al. Comparison of optimised endovaginal vs external array coil T2-weighted and diffusion-weighted imaging techniques for detecting suspected early stage (IA/IB1) uterine cervical cancer. Eur Radiol 2016; 26:941–950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li X, Wang L, Li Y, Song P. The value of diffusion-weighted imaging in combination with conventional magnetic resonance imaging for improving tumor detection for early cervical carcinoma treated with fertility-sparing surgery. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2017; 27:1761–1768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.de Boer P, Spijkerboer AM, Bleeker MCG, et al. Prospective validation of craniocaudal tumour size on MR imaging compared to histopathology in patients with uterine cervical cancer: the MPAC study. Clin Transl Radiat Oncol 2019; 18:9–15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Woo S, Atun R, Ward ZJ, Scott AM, Hricak H, Vargas HA. Diagnostic performance of conventional and advanced imaging modalities for assessing newly diagnosed cervical cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Radiol 2020; 30:5560–5577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xiao M, Yan B, Li Y, Lu J, Qiang J. Diagnostic performance of MR imaging in evaluating prognostic factors in patients with cervical cancer: a meta-analysis. Eur Radiol 2020; 30:1405–1418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Woo S, Suh CH, Kim SY, Cho JY, Kim SH. Magnetic resonance imaging for detection of parametrial invasion in cervical cancer: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature between 2012 and 2016. Eur Radiol 2018; 28:530–541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sala E, Rockall AG, Freeman SJ, Mitchell DG, Reinhold C. The added role of MR imaging in treatment stratification of patients with gynecologic malignancies: what the radiologist needs to know. Radiology 2013; 266:717–740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Park JJ, Kim CK, Park SY, Park BK. Parametrial invasion in cervical cancer: fused T2-weighted imaging and high-b-value diffusion-weighted imaging with background body signal suppression at 3 T. Radiology 2015; 274:734–741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rockall AG, Ghosh S, Alexander-Sefre F, et al. Can MRI rule out bladder and rectal invasion in cervical cancer to help select patients for limited EUA? Gynecol Oncol 2006; 101:244–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McMahon CJ, Rofsky NM, Pedrosa I. Lymphatic metastases from pelvic tumors: anatomic classification, characterization, and staging. Radiology 2010; 254:31–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sakuragi N, Satoh C, Takeda N, et al. Incidence and distribution pattern of pelvic and paraaortic lymph node metastasis in patients with stages IB, IIA, and IIB cervical carcinoma treated with radical hysterectomy. Cancer 1999; 85:1547–1554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee JM, Lee KB, Lee SK, Park CY. Pattern of lymph node metastasis and the optimal extent of pelvic lymphadenectomy in FIGO stage IB cervical cancer. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 2007; 33:288–293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Choi HJ, Ju W, Myung SK, Kim Y. Diagnostic performance of computer tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, and positron emission tomography or positron emission tomography/computer tomography for detection of metastatic lymph nodes in patients with cervical cancer: meta-analysis. Cancer Sci 2010; 101:1471–1479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu B, Gao S, Li S. A comprehensive comparison of CT, MRI, positron emission tomography or positron emission tomography/CT, and diffusion weighted imaging-MRI for detecting the lymph nodes metastases in patients with cervical cancer: a meta-analysis based on 67 studies. Gynecol Obstet Invest 2017; 82:209–222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhou M, Lu B, Lv G, et al. Differential diagnosis between metastatic and non-metastatic lymph nodes using DW-MRI: a meta-analysis of diagnostic accuracy studies. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2015; 141:1119–1130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shen G, Zhou H, Jia Z, Deng H. Diagnostic performance of diffusion-weighted MRI for detection of pelvic metastatic lymph nodes in patients with cervical cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Radiol 2015; 88:20150063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Adam JA, van Diepen PR, Mom CH, Stoker J, van Eck-Smit BLF, Bipat S. [18F] FDG-PET or PET/CT in the evaluation of pelvic and para-aortic lymph nodes in patients with locally advanced cervical cancer: a systematic review of the literature. Gynecol Oncol 2020; 159:588–596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Culverwell AD, Scarsbrook AF, Chowdhury FU. False-positive uptake on 2-[18F]-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose (FDG) positron-emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) in oncological imaging. Clin Radiol 2011; 66:366–382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Leblanc E, Gauthier H, Querleu D, et al. Accuracy of 18-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose positron emission tomography in the pretherapeutic detection of occult para-aortic node involvement in patients with a locally advanced cervical carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol 2011; 18:2302–2309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gouy S, Seebacher V, Chargari C, et al. False negative rate at 18F-FDG PET/CT in para-aortic lymph node involvement in patients with locally advanced cervical cancer: impact of PET technology. BMC Cancer 2021; 21:135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Brockbank E, Kokka F, Bryant A, Pomel C, Reynolds K. Pre-treatment surgical para-aortic lymph node assessment in locally advanced cervical cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013; 2013:CD008217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Martinez A, Voglimacci M, Lusque A, et al. Tumour and pelvic lymph node metabolic activity on FDG-PET/CT to stratify patients for para-aortic surgical staging in locally advanced cervical cancer. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2020; 47:1252–1260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rockall AG, Barwick TD, Wilson W, et al. ; MAPPING Study Group. Diagnostic accuracy of FEC-PET/CT, FDG-PET/CT, and diffusion-weighted MRI in detection of nodal metastases in surgically treated endometrial and cervical carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 2021; 27:6457–6466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.NIH/National Cancer Institute website. Citations for SEER databases and SEER*Stat software. seer.cancer.gov/data/citation.html. Accessed Nov 7, 2022

- 58.Gee MS, Atri M, Bandos AI, Mannel RS, Gold MA, Lee SI. Identification of distant metastatic disease in uterine cervical and endometrial cancers with FDG PET/CT: analysis from the ACRIN 6671/GOG 0233 Multicenter Trial. Radiology 2018; 287:176–184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.McEvoy SH, Nougaret S, Abu-Rustum NR, et al. Fertility-sparing for young patients with gynecologic cancer: how MRI can guide patient selection prior to conservative management. Abdom Radiol (NY) 2017; 42:2488–2512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jain P, Aggarwal A, Ghasi RG, Malik A, Misra RN, Garg K. Role of MRI in diagnosing the primary site of origin in indeterminate cases of uterocervical carcinomas: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Radiol 2022; 95:20210428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gui B, Lupinelli M, Russo L, et al. MRI in uterine cancers with uncertain origin: endometrial or cervical? Radiological point of view with review of the literature. Eur J Radiol 2022; 153:110357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tempfer CB, Tischoff I, Dogan A, et al. Neuroendocrine carcinoma of the cervix: a systematic review of the literature. BMC Cancer 2018; 18:530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gordhandas SB, Kahn R, Sassine D, et al. Gastric-type adenocarcinoma of the cervix in patients with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: a systematic review of the literature with proposed screening guidelines. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2022; 32:79–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chung SH, Woldenberg N, Roth AR, et al. BRCA and beyond: comprehensive image-rich review of hereditary breast and gynecologic cancer syndromes. RadioGraphics 2020; 40:306–325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bin Park S, Lee JH, Lee YH, Song MJ, Choi HJ. Multilocular cystic lesions in the uterine cervix: broad spectrum of imaging features and pathologic correlation. AJR 2010; 195:517–523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Onyiuke I, Kirby AB, McCarthy S. Primary gynecologic lymphoma: imaging findings. AJR 2013; 201:[web]W648–W655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pötter R, Tanderup K, Schmid MP, et al. ; EMBRACE Collaborative Group. MRI-guided adaptive brachytherapy in locally advanced cervical cancer (EMBRACE-I): a multicentre prospective cohort study. Lancet Oncol 2021; 22:538–547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Jacobsen MC, Beriwal S, Dyer BA, et al. Contemporary image-guided cervical cancer brachytherapy: consensus imaging recommendations from the Society of Abdominal Radiology and the American Brachytherapy Society. Brachytherapy 2022; 21:369–388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Fokdal L, Sturdza A, Mazeron R, et al. Image guided adaptive brachytherapy with combined intracavitary and interstitial technique improves the therapeutic ratio in locally advanced cervical cancer: analysis from the retroEMBRACE study. Radiother Oncol 2016; 120:434–440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ning MS, Venkatesan AM, Stafford RJ, et al. Developing an intraoperative 3T MRI-guided brachytherapy program within a diagnostic imaging suite: methods, process workflow, and value-based analysis. Brachytherapy 2020; 19:427–437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sullivan T, Yacoub JH, Harkenrider MM, Small W Jr, Surucu M, Shea SM. Providing MR imaging for cervical cancer brachytherapy: lessons for radiologists. RadioGraphics 2018; 38:932–944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mayr NA, Taoka T, Yuh WT, et al. Method and timing of tumor volume measurement for outcome prediction in cervical cancer using magnetic resonance imaging. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2002; 52:14–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wang JZ, Mayr NA, Zhang D, et al. Sequential magnetic resonance imaging of cervical cancer: the predictive value of absolute tumor volume and regression ratio measured before, during, and after radiation therapy. Cancer 2010; 116:5093–5101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Harry VN, Persad S, Bassaw B, Parkin D. Diffusion-weighted MRI to detect early response to chemoradiation in cervical cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gynecol Oncol Rep 2021; 38:100883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Meyer HJ, Wienke A, Surov A. Pre-treatment apparent diffusion coefficient does not predict therapy response to radiochemotherapy in cervical cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Anticancer Res 2021; 41:1163–1170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Schreuder SM, Lensing R, Stoker J, Bipat S. Monitoring treatment response in patients undergoing chemoradiotherapy for locally advanced uterine cervical cancer by additional diffusion-weighted imaging: a systematic review. J Magn Reson Imaging 2015; 42:572–594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Han L, Wang Q, Zhao L, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the prognostic impact of pretreatment fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography parameters in patients with locally advanced cervical cancer treated with concomitant chemoradiotherapy. Diagnostics (Basel) 2021; 11:1258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Vincens E, Balleyguier C, Rey A, et al. Accuracy of magnetic resonance imaging in predicting residual disease in patients treated for stage IB2/II cervical carcinoma with chemoradiation therapy: correlation of radiologic findings with surgicopathologic results. Cancer 2008; 113:2158–2165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Thomeer MG, Vandecaveye V, Braun L, et al. Evaluation of T2-W MR imaging and diffusion-weighted imaging for the early post-treatment local response assessment of patients treated conservatively for cervical cancer: a multicentre study. Eur Radiol 2019; 29:309–318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Schwarz JK, Siegel BA, Dehdashti F, Grigsby PW. Association of posttherapy positron emission tomography with tumor response and survival in cervical carcinoma. JAMA 2007; 298:2289–2295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Schwarz JK, Siegel BA, Dehdashti F, Grigsby PW. Metabolic response on post-therapy FDG-PET predicts patterns of failure after radiotherapy for cervical cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2012; 83:185–190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Gadducci A, Sartori E, Maggino T, et al. Pathological response on surgical samples is an independent prognostic variable for patients with stage Ib2–IIb cervical cancer treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy and radical hysterectomy: an Italian multicenter retrospective study (CTF Study). Gynecol Oncol 2013; 131:640–644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.de Foucher T, Hennebert C, Dabi Y, et al. Recurrence pattern of cervical cancer based on the platinum sensitivity concept: a multi-institutional study from the FRANCOGYN Group. J Clin Med 2020; 9:3646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Salani R, Khanna N, Frimer M, Bristow RE, Chen LM. An update on post-treatment surveillance and diagnosis of recurrence in women with gynecologic malignancies: Society of Gynecologic Oncology (SGO) recommendations. Gynecol Oncol 2017; 146:3–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lakhman Y, Nougaret S, Miccò M, et al. Role of MR imaging and FDG PET/CT in selection and follow-up of patients treated with pelvic exenteration for gynecologic malignancies. RadioGraphics 2015; 35:1295–1313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Straubhar AM, Chi AJ, Zhou QC, et al. Pelvic exenteration for recurrent or persistent gynecologic malignancies: clinical and histopathologic factors predicting recurrence and survival in a modern cohort. Gynecol Oncol 2021; 163:294–298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Sanei Sistani S, Parooie F, Salarzaei M. Diagnostic accuracy of 18F-FDG-PET/CT and MRI in predicting the tumor response in locally advanced cervical carcinoma treated by chemoradiotherapy: a meta-analysis. Contrast Media Mol Imaging 2021; 2021:8874990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Papadopoulou I, Stewart V, Barwick TD, et al. Post-radiation therapy imaging appearances in cervical carcinoma. RadioGraphics 2016; 36:538–553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Addley HC, Vargas HA, Moyle PL, Crawford R, Sala E. Pelvic imaging following chemotherapy and radiation therapy for gynecologic malignancies. RadioGraphics 2010; 30:1843–1856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Sertic M, Kilcoyne A, Catalano OA, Lee SI. Quantitative imaging of uterine cancers with diffusion-weighted MRI and 18-fluorodeoxyglucose PET/CT. Abdom Radiol (NY) 2022; 47:3174–3188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Morsing A, Hildebrandt MG, Vilstrup MH, et al. Hybrid PET/MRI in major cancers: a scoping review. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2019; 46:2138–2151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Damian A, Lago G, Rossi S, Alonso O, Engler H. Early detection of bone metastasis in small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the cervix by 68Ga-DOTATATE PET/CT imaging. Clin Nucl Med 2017; 42:216–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Ponisio MR, Dehdashti F. A role of PET agents beyond FDG in gynecology. Semin Nucl Med 2019; 49:501–511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Wyss JC, Carmona R, Karunamuni RA, Pritz J, Hoh CK, Mell LK. [(18)F]Fluoro-2-deoxy-2-d-glucose versus 3’-deoxy-3’-[(18)F]fluorothymidine for defining hematopoietically active pelvic bone marrow in gynecologic patients. Radiother Oncol 2016; 118:72–78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Dendl K, Koerber SA, Finck R, et al. 68Ga-FAPI-PET/CT in patients with various gynecological malignancies. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2021; 48:4089–4100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Ai Y, Zhu H, Xie C, Jin X. Radiomics in cervical cancer: current applications and future potential. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2020; 152:102985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Zhang Y, Zhang K, Jia H, et al. IVIM-DWI and MRI-based radiomics in cervical cancer: prediction of concurrent chemoradiotherapy sensitivity in combination with clinical prognostic factors. Magn Reson Imaging 2022; 91:37–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Zhou Z, Maquilan GM, Thomas K, et al. Quantitative PET imaging and clinical parameters as predictive factors for patients with cervical carcinoma: implications of a prediction model generated using multi-objective support vector machine learning. Technol Cancer Res Treat 2020; 19:1533033820983804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Ren J, Li Y, Yang JJ, et al. MRI-based radiomics analysis improves preoperative diagnostic performance for the depth of stromal invasion in patients with early stage cervical cancer. Insights Imaging 2022; 13:17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Zhang X, Zhao J, Zhang Q, et al. MRI-based radiomics value for predicting the survival of patients with locally advanced cervical squamous cell cancer treated with concurrent chemoradiotherapy. Cancer Imaging 2022; 22:35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]