Abstract

Introduction

Sexual distress related to sexual function (SDRSF) is pivotal in diagnosing sexual dysfunction. However, there is a lack of theoretical models for its comprehension and of knowledge concerning how to address it in clinical practice.

Aim

To contribute to theory building and clinical practice about SDRSF by collecting clinicians' accounts, aiming to inform a preliminary framework to study and intervene in SDRSF.

Method

Reflexive thematic analysis was used to analyze the data from 16 semi-structured interviews with clinical sexologists. Results: Three main themes were created: (1) Burning from the inside, (2) Wicked games, and (3) Running up that hill. Participants revealed a multidimensional understanding of SDRSF in clinical settings that integrates individual, sociocultural, interpersonal and situational factors. This underscores the interconnected nature of SDRSF, revealing its links to different facets of overall distress in clinical settings. We present a preliminary framework that may be analytically generalized to enhance the comprehension of the specificities of SDRSF.

Conclusion

These insights frame a comprehensive conceptualization of SDRSF in clinical settings that goes beyond sexual activity and implies that interpersonal and societal factors need to be considered in research and intervention in this field.

Keywords: Sexual distress, Sexual function, Reflexive thematic analysis, Clinical sexologists, Preliminary framework

Introduction

Sexual dysfunctions affect a significant proportion of the general population, impacting approximately one-third of adults across all ages and genders (Lafortune et al., 2023). Insights into specific prevalence rates have found that, in men, delayed ejaculation is observed in 1–5 % of them, while premature ejaculation is reported in 8 %−30 %. Erectile disorder is seen in 13 %−21 % of men, and male hypoactive sexual desire disorder affects 3 %−17 %. In the case of women, the prevalence of female orgasmic disorder is 8–72 %, while genito-pelvic pain/penetration disorder is seen in 10–28 %. Additionally, around 30 % of women who experience chronic low desire are impacted by female sexual interest/arousal disorder (APA, 2022). These sexual dysfunctions are characterized by significant impairment of sexual response and pleasure, causing persistent and clinically significant distress for at least six months (DSM-5-TR; APA, 2022). This clinical conceptualization of sexual dysfunctions accentuates the importance of positive outcomes in clinical practice (pleasure) but also reinforces the centrality of negative emotions (distress) as essential to both diagnosis and intervention, highlighting that to intervene more effectively, it is important to have an accurate comprehension of sexual distress related to sexual function (SDRSF). Despite its importance, the literature on SDRSF is scarce. We hope to contribute to advancement in this field by presenting the clinical conceptualization of SDRSF from the point of view of a group of experts who act in clinical sexology, resulting in a preliminary framework to study and, possibly, intervene in SDRSF.

The concept of SDRSF has gained significant attention in research, given its essential role as a mandatory criterion for diagnosing sexual dysfunctions (APA, 2022; WHO, 2022). Some authors argue that including SDRSF as a criterion of sexual dysfunctions helps filter out clinically significant difficulties in clinical contexts (Bancroft et al., 2003; Hendrickx et al., 2019; Perelman, 2011). The intensity of SDRSF may be a crucial factor in prompting individuals to seek professional help (Lafortune et al., 2023). Nonetheless, SDRSF exists in non-clinical contexts, as demonstrated by research that shows that people with distressful sexual function may not seek help (Velten & Margraf, 2023) due to the lack of availability of services, financial constraints, or shame and stigma related to seeking help in mental health (Helmert et al., 2023) or specifically in sexual health contexts (Hinchliff et al., 2021). Moreover, SDRSF may occur without a formal diagnosis, as shown by a cross-sectional quantitative study conducted in Australia, which revealed that nearly one-third of all women experience high levels of SDRSF, even in the absence of specific criteria for diagnosing sexual dysfunctions (Zheng et al., 2020). These results highlight the broader significance of SDRSF, extending beyond the confines of diagnosing sexual dysfunctions, significantly framing subclinical and community populations and acknowledging that SDRSF needs to be studied from a global perspective that includes information derived from multiple contexts, including, but not restricted, to clinical settings.

The negative impact of SDRSF operates in a bidirectional snowball effect, reducing psychological well-being, which, in turn, contributes to heightened SDRSF (Bancroft et al., 2003). In other words, the relationship between SDRSF and psychological well-being is not only bidirectional - meaning that SDRSF can be a risk factor for psychological well-being and vice versa - but it is also self-reinforcing and has the potential to amplify over time. This means that SDRSF can negatively impact psychological well-being, leading to an increase in SDRSF. Complementarily, lower levels of psychological well-being may negatively impact SDRSF, which, in turn, will increase the lower levels of psychological well-being. This creates a snowball effect where each factor exacerbates the other in a continuous, dynamic, escalating loop between the two variables. This continuous loop effect may also involve other processes, such as depression and anxiety (Jacobson & Newman, 2017), usually related to the experience of SDRSF, as highlighted by research that supports that sexual dysfunctions are within the internalized spectrum of psychopathology that includes anxiety and mood disorders (Forbes et al., 2017; Squibb et al., 2019).

Even though psychological distress and SDRSF may be related, they are distinct dimensions, as supported by empirical data that shows a moderate association between these two dimensions (Raposo et al., 2023; Tavares et al., 2020). Psychological distress refers to the negative psychological experiences one may face and often arises from diverse life stressors, traumatic experiences, or underlying psychiatric conditions affecting overall mental well-being (Carrozzino et al., 2022). As for SDRSF, it relates to negative emotions in the sexual domain (Nimbi et al., 2020) and has been associated with a combination of psychological and physical factors, such as body image concerns, trauma, repetitive negative thinking, difficulties with emotion regulation, medical conditions and side effects of medications (Brotto et al., 2016; Manão et al., 2023).

Given the potential bidirectional impact of SDRSF on sexual and mental health, it is essential to explore and clarify its meaning and scope in clinical contexts to identify common and transversal approaches to this construct among professionals in the field.

Despite its clinical relevance and widespread existence, there is a lack of research derived from clinical contexts that contributes to a comprehensive approach to its understanding. Most research on SDRSF has been conducted outside clinical contexts with community participants (e.g., Gunst et al., 2018; Dewitte et al., 2020) and showing a systematic association between SDRSF and mental health outcomes (anxiety, depression) (e.g., Guerreiro et al., 2023; Wahlin-Jacobsen et al., 2017) as well as with interpersonal dimensions (negative partner emotional responses; Stephenson et al., 2018).

To gain a nuanced understanding of SDRSF, it is important to explore how researchers have been operationalizing it. For example, Hendrickx et al. (2016, p. 1662) define SDRSF as “distress that is experienced due to a sexual impairment,” providing insight into a broad experience of distress related to sexual function. However, it is crucial to acknowledge that, despite this valuable understanding, there is a discernible lack of a consensual and precise definition. Instead, several studies that address SDRSF employ different terms, such as “sexually related personal distress” (Bois et al., 2016) and “sexual and relationship distress” (Frost & Donovan, 2018). Each of these instances underscores different aspects of the SDRSF an individual may experience, and these diverse approaches have an impact in clinical and research settings.

In clinical contexts, the lack of precise conceptualization and operationalization may work as a barrier to communication between health professionals, negatively impacting work in clinical settings. Consequently, professionals in sexual health, especially the ones who are dealing with sexual dysfunctions, may find it challenging to identify specific indicators of and correlates for assessment and intervention that are integrated into a comprehensive model. This can lead to challenges in reducing SDRSF in clinical settings and undermine research in this field.

Concerning research, without an existing theoretical framework based on a consistent body of knowledge regarding SDRSF, there may be a lack of comprehension regarding the factors (e.g., predictors, mediators) that may influence SDRSF, making it challenging to formulate straightforward research questions and hypotheses, as well as integrate and interpret empirical findings that contribute to developing a comprehensive understanding of the construct. This knowledge is essential as the existing research highlights the significant detrimental effects of SDRSF on people's lives, including their mental health (Bancroft et al., 2003; Walker & Santos-Iglesias, 2020), relationships (Burri et al., 2011) and overall well-being (Basson et al., 2004). Clear and agreed-upon comprehension is also crucial to developing standardized assessment tools for sex research that focus on SDRSF.

Sexologists and sex therapists lead and treat SDRSF in their clinical practice; therefore, considering their expert opinion is crucial to establishing a consensus and providing guidance for professionals working with individuals experiencing it. Therapists are authoritative sources as they are both recipients and producers of knowledge in their field (Meuser & Nagel, 2009). Although expert opinions may have a low evidence grade, they should not be disregarded as they are a valuable resource for evidence-based practice (Burns et al., 2011). It is important to consider that external evidence methodologies alone may not be sufficient, and without expert opinions, evidence may be insufficient for individual patients (Sackett et al., 1996). Indeed, several studies explored clinicians' opinions to inform clinical practice (e.g., Smith & Gillon, 2021). Research with experts in the realm of sexuality has created preliminary frameworks for research (e.g., Pascoal et al., 2021) or clinical practice (Pretorius et al., 2022). In line with this research that explored experts' opinions, our study aims to provide space for clinical sexologists to share their approaches to SDRSF in clinical practice. We recognize that a shared understanding of SDRSF among experts can enhance comprehension, foster the development of a consensual definition, and inform more uniform practices. This, in turn, can advance research on SDRSF and improve healthcare for individuals with SDRSF.

Clinical sexology in Portugal is grounded in the fields of medicine and psychology. In this context, the profession of a clinical sexologist is shaped by the organizational structures in which they were and are involved. Scientific societies are essential in organizing and legitimizing the profession, awarding diplomas, and formulating ethical and professional guidelines (Giami & Michaels, 2020). These organizations not only frame the professional background but also provide supportive learning for the development of clinical sexologists' work in their clinical practice. Currently, licensed clinical sexologists in Portugal may have gained their theoretical expertise by receiving post-graduate education from international societies (e.g., the European Society for Sexual Medicine) or private or public organizations that run commercial theoretical-based degrees. They should have received (or may be still receiving) their professional training for clinical practice in the context of private and public sexological settings. They could also have been extensively professionally educated in theory and practice by the Portuguese Clinical Sexology Association (SPSC). SPSC has played a pivotal role in clinical sexology training, conferring the title of sexual therapist since 1995. This recognition is granted upon completing a comprehensive three-year training program encompassing theoretical instruction, clinical practice in public settings, supervision sessions, and developing relevant research (Alarcão et al., 2017). SPSC also promotes scientific meetings among experts, produces clinical statements (e.g., position statement regarding conversion therapies; Pascoal et al., 2019), promotes research development (e.g., Beato et al., 2024; Costa et al., 2023), develops community actions (e.g., commemorating national sexual health day) and is actively involved with international societies (e.g., European Federation of Sexology; World Association for Sexual Health). Given this background and intensive training, SPSC experts usually have a deep involvement with the field of clinical sexology and a deep understanding of SDRSF may be due to their unique clinical experience, implicit knowledge, and ability to provide valuable professional insights, and they can offer an informative perspective (Meuser & Nagel, 2009).

To improve clinical practice and research design in the context of SDRSF, it is essential to have a better understanding of how it is conceptualized and approached. Based on expert opinions, we aim to contribute to a preliminary conceptual framework of SDRSF that may guide researchers and clinicians and create a more nuanced and empirically grounded understanding of this concept.

Current study

This exploratory qualitative cross-sectional study aimed to address the research question: “How do clinical sexologists conceptualize SDRSF in clinical settings?”.

Materials and methods

Participants

A total of 16 clinical sexologists participated in this study: 14 self-identified as women (87.5 %), and 2 self-identified as men (12.5 %). With ages between 29 and 52 (M = 39.25; SD = 8.17), participants had between 1 to 28 years of clinical practice in clinical sexology (M = 12; SD = 8.74). Regarding background training, 10 (62.5 %) participants were clinical psychologists, 5 (31.3 %) were medical doctors (3 general practitioners/family doctors, 1 psychiatrist, and 1 clinical pathologist), and 1 was a psychologist specialized in deviant behavior (6.3 %). All participants were trained and are experts in the field of mental health and sexual therapy. Concerning the settings where participants usually practice clinical sexology, 7 (43.8 %) work only in public settings, 5 (31.3 %) work in public as well as private settings, and 4 (25 %) work only in private settings.

Research design

Considering the absence of prior studies dedicated to understanding how SDRSF is clinically conceptualized and considering the study's emphasis on perspectives, meanings, and experiences in clinical practice, we deemed it appropriate to employ an experiential qualitative design (Braun & Clarke, 2021a). This approach allowed us to explore how clinical sexologists perceive and operationalize patients' SDRSF within their professional contexts. Our analysis focused on underlying meaning-making around their clinical experience to make sense of SDRSF. Semi-structured interviews were employed for comprehensive dataset generation.

Dataset generation

Expert interviews were undertaken to gather data from clinical professionals licensed and experienced in treating individuals with sexual dysfunctions. So, to be included in the present study, participants had to: (a) understand the Portuguese language; (b) have professional background training in health areas (e.g., psychologists, medical doctors, nurses); and (c) be clinical sexologist (i.e., having training and supervised experience, along with a degree in the field of sexual therapy or sexual medicine). The participants were recruited through internal dissemination in national institutions related to sexual health (e.g., SPSC; Associação para o Planeamento da Família [APF]) because these institutions are respected authorities in the field of sexual health in Portugal and allow us to reach a pool of clinical professionals licensed and experienced in treating individuals with sexual dysfunctions. A link was shared to an online page with a general description of the study, including conditions of participation, authorship and affiliations, funding sources, and email contact of the first author. Participants were required to thoroughly read the contents of the informed consent document, providing their explicit agreement to the outlined study conditions or contact the research team if they had any doubts. Also, they were requested to provide their email addresses, which were crucial to schedule an interview. No specific number of participants was required to conduct the present study since, in qualitative studies, it is recommended to consider the information power concept. That means the more relevant information participants of a study have, the fewer participants are needed (Braun & Clarke, 2021b; Sim et al., 2018). We cannot calculate the rejection rate as we do not know how many people were reached and how many viewed the invitation to participate.

The authors collaboratively developed the interview guide's structure. Upon consulting with a senior expert in qualitative studies who is a licensed sexual therapist with extensive knowledge of the Portuguese clinical sexology context, the authors agreed not to explore clinicians personal sexual experiences and how these could inform their professional development in clinical sexology as this was beyond the scope of the current study and could be perceived as invasive and judgmental. The first author pilot-tested the interview with 3 sexual health professionals with expertise in qualitative methodology, specifically reflexive thematic analysis. This pilot testing aimed to improve the interview and identify potential challenges for the actual data collection process. After this step, the interviews were conducted remotely through the online Zoom platform, facilitated by the first author - a clinical psychologist trained in the cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) model and with expertise in clinical sexology. The identity of the participants was preserved (only the audio component was recorded, the participants’ names were not mentioned during the conversation as no patient's name was mentioned). However, a brief description of primary sociodemographic data and data about their professional situation was requested to allow the characterization of the study participants. After conducting all the interviews and listening to the recording multiple times, the first author transcribed the audio, indicating any hesitations, pauses, or repetitions in the participant's discourse. All the information collected is stored in folders protected by different passwords on a private device.

Departing from clinician's meaning making of their professional experience, the interview aimed to gain insights into the clinical conceptualization of clinical sexologists when assessing SDRSF. This study was prepared following the principles of the Helsinki Declaration and of the European Textbook on Ethics in Research. The Ethical and Deontology Committee for Scientific Research of the School of Psychology and Life Sciences (CEDIC) of Lusófona University in Lisbon approved it. No incentives were provided to participants. Data was collected between October and December 2021.

Data analysis

We followed a reflexive thematic analysis as proposed by Braun and Clarke (2021a), focusing on lived experiences in clinical contexts, and took a critical realist understanding of participants' answers. This exclusively qualitative method not only facilitated a thorough exploration of participants' contextually situated clinical experiences, meanings, and behaviors (Braun & Clarke, 2022) within their specific contexts but also played a crucial role in exploring patterns of meaning. This nuanced approach sheds light on clinical sexologists' viewpoints, significantly contributing to a deeper understanding of how SDRSF manifestations is perceived and interpreted in clinical practice. Moreover, it facilitates the accurate operationalization of these concepts, enriching the comprehension of the intricate dynamics involved.

The data analysis followed a data-driven approach since the meaning of SDRSF is underexplored. Furthermore, a contextual perspective was adopted, which views subjective experiences as inherently situated within specific contexts (Braun & Clarke, 2022), as we consider that participants' meanings and reflections are shaped by the broader social, cultural, and historical contexts in which they are situated.

As thematic analysis acknowledges the role of subjectivity and encourages active reflection (Braun & Clarke, 2021a), the authors’ professional backgrounds and perspectives – mostly CBT psychologists and sexual health researchers - inevitably shape the understanding of how SDRSF is conceptualized in clinical settings, mainly because they have professional experience with patients reporting SDRSF. Moreover, the fact that the authors are clinical psychologists and researchers provides some advantages when conducting qualitative analysis, as this dual role can help strike the right balance between understanding participants’ experiences and maintaining scientific precision. Additionally, being clinical psychologists and researchers may make them more sensitive to identifying data patterns and understanding their findings and clinical implications. As posited by Smith and Thew (2017): “Clinical psychologists’ combination of clinical expertise and research training means that they are in an ideal position to be conduction high-quality research projects that aim to better understand and intervene across a range of clinical issues” (p. 354) and “[…] psychologists already have a number of transferable skills from their clinical work, such as the ability to approach a problem logically and systematically, or the capacity to attend accurately and consider carefully what a client is saying, which are equally important and valuable within the research domain” (p. 354).

According to the guidelines of Braun and Clarke (2021a), the first and third authors read through all the responses to become familiar with the data. They independently generated an exhaustive list of potential codes. In the initial stages of analysis, the generated codes exhibited a semantic nature. Afterward, the revised codes became mostly latent, reflecting a deeper understanding of shared meaning across codes. During the examination of the transcriptions, the first and third authors conducted independent analyses, while the fourth author reviewed and refined the codes, subthemes, and themes until all authors collaboratively achieved a coherent and representative depiction of the data. Again, they tested the coding scheme on a sample of text from their transcriptions to ensure the consistency and clarity of the codes’ definitions, achieving a high level of coding consistency. After the reflexive collaboration between the first and third authors, the fourth author checked again to see if the data fit the final proposal of the thematic analysis.

Although Braun and Clarke (2024) state that it is not recommended to split the “Results” and “General discussion” sections, they recognize that some journals may require this format (Braun & Clarke, 2021a). Therefore, we will follow the journal guidelines and include separate sections for “Results” and “General discussion” in our paper.

In the following sections (“Results” and “General discussion” sections), themes are presented in bold, subthemes are underlined, and examples of quotes are italicized. Each quote includes a brief anonymous sociodemographic description of each participant's area of professional specialization. We have intentionally omitted any reference to age and gender and used fake initial names to ensure the complete anonymity of the participants.

In the presented quotes, we have excluded redundant elements derived from the patient's speech that clinicians referred to enhance readability, but only if it did not modify the meaning of the sentences. We denote these elements with square brackets “[…]”, as in other qualitative studies (Cowie & Braun, 2022). For example, instead of perceive pleasure as a loss of control, generally, generally, I think, experience some distress, we corrected it to perceive pleasure as a loss of control […] generally, I think, experience some distress (G.Z., clinical psychologist). Quotes referring to personal experiences of SDRSF are examples that professionals shared and are related to patients and not their accounts.

Results

Participants offered direct, metaphorical, reflective and reflexive responses provided hypothetical scenarios (e.g., For example, a person comes to the office and usually says that […]”; C.Z., general practitioner/family doctor) to illustrate their reasoning and presented examples of patient cases (e.g., I had a patient that clearly stated that […]; M.V., clinical psychologist). These real-life examples provided concrete instances where SDRSF occurs. The interviews ranged from 15 to 52 min, with an average duration of 28 minutes.

During the interviews, participants shared their definitions of this construct, and they discussed several factors, such as explanatory factors, correlates, and risk factors contributing to the development and persistence of distress related to impaired sexual function, sometimes caused by existing medical conditions and treatments. Participants offered vivid and descriptive examples of cases and situations encountered in their clinical practice – without revealing confidential information about the patients – (e.g., women with pelvic pain – so much sexual distress. Many times, here, there are medical issues in the mix. What happens is that these women sometimes have certain traits that magnify or not the pain, based on that gatekeeping theory of pain, which, depending on the stimuli we select, the thoughts that we give space or not, then the pain ends up having a greater or lesser manifestation on us; J.R., clinical psychologist).

We observed some bias associated with the specific area in which clinical sexologists work. For example, medical doctors focus more on reflecting on psychiatric disorders (e.g., what often comes to the forefront in consultations regarding sexual distress are indeed psychiatric comorbidities, thus related to anxiety and depression; A.B., general practitioner/family doctor) and anatomical aspects (e.g., I think chronic illnesses, undoubtedly, including aging; S.M., general practitioner/family doctor) that may coexist with SDRSF; psychologists focus more on reflecting on explanatory factors for the emergence of SDRSF (e.g., […] people who struggle more to connect with pleasure or perceive pleasure as a loss of control […] generally, I think, experience some distress and difficulty in the realm of leading a pleasurable, healthy, or satisfying sexuality; G.Z., clinical psychologist). We noticed no pattern linking the years of experience and the conceptualization of SDRSF presented.

Although monogamous and heterosexual relationships were more commonly referred to, it is essential to acknowledge that participants mentioned diverse relationship types throughout the interviews. Still, we only found one pattern regarding specific relationship structure and the approach to SDRSF; namely, participants reported that single people seem to feel less pressure toward sexual performance.

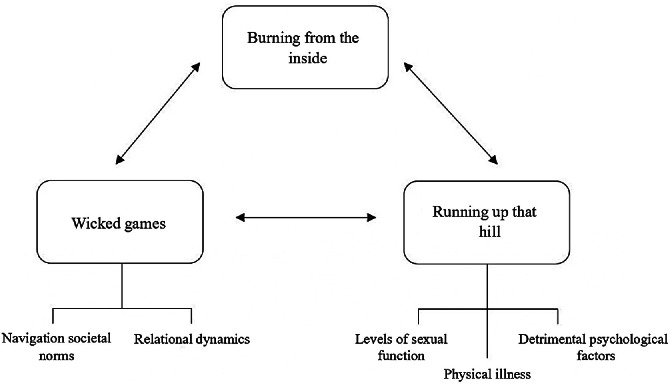

The pattern in responses indicates a multidimensional understanding of SDRSF. Three main interrelated themes were created: (1) burning from the inside; (2) wicked games; and (3) running up that hill. Within these themes, we identified individual (first and third themes), sociocultural (second theme), and situational factors (second theme). No subthemes were created in the first theme, burning from the inside. Two subthemes were created in the second theme, wicked games: (1) navigating societal norms and (2) relational dynamics. In the third theme, running up that hill, three subthemes were created: (1) levels of sexual function, (2) physical illness, and (3) detrimental psychological factors. All subthemes are interrelated. Examples of quotes are presented in-text, but Table 1 presents detailed examples.

Table 1.

Hierarchical organization of the preliminary framework about SDRSF.

| Themes | Subthemes | Codes | Description | Examples quotes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Burning from the inside | Negative emotions | Negative emotional states related to individuals' SDRSF | “Psychological distress associated with a sexual problem or sexual dysfunction.” (R.Q., psychiatrist) “[Is when] I feel bad, I feel anxious, I feel sad, most of the time in relation to my sexual and intimate sphere.” (J.R., clinical psychologist) |

|

| Loneliness | Intensified feelings of isolation and profound loneliness | “[SDRSF] turns out to be something experienced almost in a very lonely way.” (L.D., clinical psychologist) “[people with SDRSF] may feel less supported.” (F.G., clinical psychologist) |

||

| Wicked games | Navigation societal norms | Gender scripts | Cultural gender scripts that women and men are compelled to fulfill | “I have to do this [in sexual intercourse] because it is part of my skills as a wife […] woman as a caregiver. [...] “There is all this pressure to men be Latin machos.” (S.M., general practitioner/family doctor) |

| Media pressure | Transmission of ideas and beliefs that amplify comparisons and social pressure to conform to a sexual norm | “I do it because everyone does it, but I do not like it.” (G.Z., clinical psychologist) “I feel that I have to have five or six orgasms all in a row.” (J.R., clinical psychologist) |

||

| Internalized sexual stigma | Stigma associated with aspects of sexual activity that individuals internalize as abnormal | “And it was challenging, for example, he had a boyfriend, but the sexual relationship with his boyfriend did not work out well because for him [homosexual men] sex was something filthy, very wrong. [...] “He was clearly in distress, and this came from this issue of internalized homophobia, which nowadays is debated whether it is internalized homophobia or if we are talking about discrimination.” (J.R., clinical psychologist) |

||

| Relational dynamics | Communication difficulties | Challenges in debating and expressing views and experiences related to sexuality in a clear way | “He also did not know how to approach the topic […] so his way of approaching was to leave the lube on the bedside table so that she would realize that he wanted to have sex, and then this had a tremendous impact on the couple […] they were no longer able to communicate with each other.” (J.R., clinical psychologist) “If we do not have clear and conscious communication with the other person, we may also not give them a clear understanding of what we want […], and they will not correspond to what we expect.” (E.S., clinical psychologist) |

|

| Committed relationships' stressors | Experience of SDRSF in individuals in committed relationships | “In the clinical sessions, I realized that these partners are not predisposed to be understanding and collaborate in the psychotherapeutic process.” (T.N., clinical psychologist) “I think that [premature ejaculation] turns out to be a distress for them when they realize that the partner is dissatisfied and when there is pressure from the partner.” (M.V., clinical psychologist) |

||

| Relationships' avoidance | Interference of SDRSF in the possibility of having a committed relationship | “For some people, it can be more facilitating because they don't feel so exposed that there was a situation that did not go well. If they do not go back […] to see that person, they will no longer deal with that anxiety or something that made them feel bad because they won't see that person again. It is as if there could be a relief.” (F.G., clinical psychologist) “This creates a massive barrier in the search to be with someone sexually because they have many difficulties, and then they avoid it.” (I.C., clinical psychologist) |

||

| Running up that hill | Levels of sexual function | Sexual function impairment | The levels of existing impairment with sexual function's domains are seen as a risk factor for developing and maintaining SDRSF | “Hypoactive sexual desire”, “genital-pelvic pain” (J.R., clinical psychologist); “dyspareunia”, “sexual pain” (R.Q., psychiatrist); “premature ejaculation”, “vaginismus” (C.Z., general practitioner/family doctor) |

| Physical illness | Medical condition | Medical conditions are mentioned as a risk factor for developing and maintaining SDRSF | “Hypertension”, “cardiovascular problems” (I.J., clinical psychologist); “diabetes”, “endometriosis” (J.R., clinical psychologist); “obesity” (L.D., clinical psychologist); “oncological diseases” (S.M., general practitioner/family doctor); “sexually transmitted infections” (F.G., clinical psychologist) “[women with postpartum incontinence] I see them a lot, and there is immense discomfort with themselves and their partners.” (C.Z., general practitioner/family doctor) |

|

| Detrimental psychological factors | Emotional disorders | Psychological and emotional problems mentioned as risk factors for developing and maintaining SDRSF | “Mood disorders.” (I.C., clinical psychologist) “If there is any mental health disorder, if the person has depression or if they have an anxiety disorder, if there is already some pathology, both physical and mental, in reality.” (S.M., general practitioner/family doctor) |

|

| Personality | Personality traits or disorders reported as being associated with SDRSF | “Personality structure”; (T.N., clinical psychologist) “I was thinking here of people who meet the criteria for borderline personality disorder.” (J.R., clinical psychologist) |

||

| Body-disconnection | Negative relationship with one's own body coupled with a limited awareness of personal bodily pleasure preferences | “A non-acceptance of one's own body.” (F.G., clinical psychologist) “When I realize they do not know what they like best [in sexual activity], do not know what kind of practices they prefer [in sexual activity], do not know how to ask how [can] they reach [sexual] satisfaction.” (J.R., clinical psychologist) |

Burning from the inside

This theme apprehends the codes related to negative emotional states that people experience concerning their sexual activity and illustrates the lived experience of SDRSF during and beyond sexual activity. According to the participants, several people in the clinical context mention that they are at the maximum emotional pain threshold, overwhelmed with internal negative experiences related to sexual function (e.g., I cannot take it [the emotional pain] anymore; J.R., clinical psychologist). These negative emotional experiences are linked to partnered sexual activity and appear to intensify feelings of isolation, as it is often described as a profoundly lonely and isolating experience, which in turn further exacerbates the suffering. Participants emphasized this escalating nature, departing from a negative experience during sexual activity that produces negative emotional states throughout time due to reliving the experience and having negative expectations. This process may disrupt and impair individuals, compromising different areas of their lives (e.g., this distress may impact other areas of their lives; J.R., clinical psychologist).

Wicked games

Drawing from their patients’ experiences, participants often associate SDRSF with power dynamics. We defined the subtheme of navigating societal norms since the participants highlighted that, in society, these games of power involve influences such as gender roles, societal pressure, media expectations, and stigma towards sexual activity – making sex a private matter (e.g., it is taboo; C.Z., general practitioner/family doctor) - impacting SDRSF and – ultimately – sexual pleasure (e.g., [due to the media] I think that we [society] still haven't thought in words “sexual pleasure” because we have fallen into that more conservative discourse of “ok, it's a taboo to talk about sex, or masturbation, or this or that”; J.R., clinical psychologist). These societal norms often put social pressure on men regarding their frequency of sexual activity (e.g., [to men] the pressure to be always ready for sex; S.M., general practitioner/family doctor).

Within the subtheme of relational dynamics, SDRSF was considered a complex experience related to communication challenges, conflicting emotions, and relational patterns. Several professionals stated that, often, the pressure of having sexual problems experienced with SDRSF can lead individuals to fear that the relationship will end (e.g., fear that the marriage will end because of this; M.V., clinical psychologist). As a strategy to cope with this perception of a break of the relationship, some people seem to engage in betraying behaviors (e.g., […] some will seek extramarital relations to test their sexual problem [SDRSF] and see if the problem persists [with another sexual partner] (M.V., clinical psychologist).

Also, the pressure to conform to gender roles was highlighted. For example, I was pregnant, in the postpartum period, and [my boyfriend] said to me: «It's been 9 months without [sexual] intercourse; I need to have sex», and he cannot take it anymore, and I have to put up with it. (C.Z., general practitioner/family doctor). This pressure seems to make people in clinical sessions struggle with a dissonance between what they are supposed to do due to the gender roles in sexual activity and what they want to do, such as: I do it because every woman does it, but I do not like it (G.Z., clinical psychologist). However, in single people, there seems to be lower pressure on sexual performance, namely, e.g., it did not go well, I did not feel well, I do not have to face it [the pressure of having a distress sexual problem], I do not have to deal with it, and maybe next time it will go better or not. (F.G., clinical psychologist). SDRSF was associated with not meeting partner expectations and the possible consequences of that (e.g., What makes people search for help is not what they feel about themselves. Instead, it is the impact it ends up having on the relationship, whether it is a real impact or a perceived one, or the person anticipates the consequences that the situation may have. I'm thinking about, for example, cases of desire discrepancy; A.F., clinical psychologist).

These two subthemes related to power dynamics describe contextual factors that contribute to tension and strain involving SDRSF.

Running up that hill

This theme encapsulates participants’ identification of individual risk factors for the development and persistence of SDRSF. Within the subtheme levels of sexual function, participants note that perceived difficulties with sexual function inherently contribute to SDRSF (e.g., [situations in which] people feel more limited, they want [to do something in sexual activity]. Still, they can't, or they feel inadequate in some way by doing it; A.F., clinical psychologist).

The existence of a physical illness (e.g., Chronic diseases [as risk factors], and when we talk about sexuality, they [chronic diseases] are often not given any attention, and people suffer alone, right? It's like: “ok, my sexuality is done; I can't talk about any of this distress because oncological disease is the most important; S.M., general practitioner/family doctor) it is recognized as a potential risk factor for the development and persistence of SDRSF.

In terms of detrimental psychological factors, participants highlight that emotional disorders (e.g., whether the person has depression or an anxiety disorder; S.M., general practitioner/family doctor), personality traits (e.g., These types of personality traits, very anxious, very controlling, very perfectionist, I usually think that they lead to some distress and some difficulty in the context of living pleasant and healthy or satisfying sexuality; C.Z., general practitioner/family doctor), body disconnection as negative emotional experiences (e.g., negative body image, lousy self-image; L.D., clinical psychologist) and low self-esteem (e.g., poor self-esteem; T.N., clinical psychologist) can also function as risk factors for the development and persistence of SDRSF.

This systematic coding process, interpretation, and development of candidate themes and subthemes collaboratively and reflexively led us to a preliminary framework about SDRSF (Fig. 1) drawn from clinical experience.

Fig. 1.

A preliminary conceptual framework of SDRSF.

General discussion

There has been renewed and increasing clinical interest and research on SDRSF in recent years (Santos-Iglesias et al., 2018). This study expands knowledge on SDRSF by analyzing clinical sexologists’ perceptions of SDRSF.

Using a reflexive thematic analysis frame for data analysis, we created three main themes: (1) burning from the inside, (2) wicked games, and (3) running up that hill. Together, these themes demonstrate a strong relationship between SDRSF and intrapersonal, interpersonal and societal dimensions.

The intense negative emotional experience portrayed in the theme burning from the inside underscores the significant impact that SDRSF can have on an individual's psychological well-being, illustrating the parallels between SDRSF and psychological distress (Guerreiro et al., 2023; Pascoal et al., 2020). Psychological distress often incorporates depressive symptomatology and loneliness (e.g., Yung et al., 2023) – psychological risk factors for the development and persistence of problems that are also mentioned in the running up that hill theme. Psychological distress seems to be a core characteristic of SDRSF and, therefore, shares the same emotional base. Thus, our results reinforce that sexual dysfunction should be approached from a dimensional framework of psychopathology (Kotov et al., 2017). This dimensional empirical-based approach underscores the presence of psychological factors across a spectrum of emotional problems and integrates sexual dysfunctions within the internalizing spectrum of disorders (Forbes et al., 2016). Clinical interventions, such as the transdiagnostic approach, are aimed at standard explanatory processes (Dalgleish et al., 2020) and aimed at comorbid emotional disorders. This is supported by preliminary recent research in community samples whose results indicate that there is an association between SDRSF, depression symptoms and transdiagnostic factors (e.g., Guerreiro et al., 2023; Manão et al., 2023; Raposo et al., 2023). So, in sexology clinical settings, it is essential to consider both the severity of psychological distress and any comorbidities with emotional and psychological problems and identify shared underlying mechanisms responsible for SDRSF and psychological distress to have a comprehensive view of the problem being presented (Hendrickx et al., 2019). Also, when working with people with SDRSF, referral to mental health specialists may be necessary as any intervention should consider and address factors that contribute to and exacerbate SDRSF, as shown in the other themes. To help people diagnosed with sexual dysfunctions, intervention models that have a comprehensive assessment and diagnosis and that have shown empirical evidence in reducing symptomatology (e.g., mindfulness-based therapies [Banbury et al., 2023], transdiagnostic interventions for emotional disorders [Dalgleish et al., 2020], and the cognitive-behavioral approach [Mestre-Bach et al., 2022]) should be used.

The second theme, wicked games, focuses on the contextual power dynamics contributing to and perpetuating SDRSF. These power dynamics align with the Sexual Script Theory (Simon & Gagnon, 1973) by underscoring how human sexual behavior and its outcomes, including sexual function, are socially influenced and framed by sociopolitical organizations such as the media or the government. This theme encapsulates the subtheme of navigating societal norms, highlighting the complex interplay between individuals and these prevailing norms.

According to the participants, some contextual and social influences can perpetuate the notion of sex as immoral, viewing it as a private matter. This perception can detrimentally affect individuals' sex lives (Mallory, 2022). Participants noted that viewing sex as taboo leads to communication issues that result in less intimacy and satisfying sexual experiences, regardless of individuals' sexual health status. Consequently, this cycle can lead to the emergence and maintenance of SDRSF, contributing to emotional, psychological, and physical problems.

Due to the impact that societal norms have on sexual scripts and gender roles (Byers, 1996), interpersonal contexts, namely sexual ones, may be strongly genderized. Based on our participants’ accounts, social pressure on men regarding their sexual activity may be internalized through socialization (e.g., Duncan, 2012) and makes it more demanding for them to be aware of and identify their difficulties. If associated with rigid beliefs about the importance of sexual performance to prove men's masculinity and virility (Nobre et al., 2003), this type of societal script can lead men to avoid seeking professional help (Ford, 2021). A systematic review on the role of men's sexual beliefs on sexual function/dysfunction (Moura et al., 2023) offers an overview of the existing scientific evidence that supports this line of reasoning. Men who hold stronger negative sexual beliefs, including sexual conservatism, male-centric beliefs, performance-related beliefs, and masculinity beliefs, tend to experience lower levels of sexual functioning. Furthermore, men who have sexual dysfunctions, such as low sexual desire and erectile dysfunction, tend to exhibit higher agreement with negative and stereotypical beliefs about male sexuality (Moura et al., 2023). These findings align with other studies suggesting that the adaptability of sexual scripts is linked to reduced SDRSF (Moura et al., 2023).

Sexual double standards, in which gender scripts prioritize male sexual gratification and depict men in heterosexual relationships as dominant and sexually demanding while portraying women as submissive and responsible for maintaining the relationship (Ford, 2021) were described by participants. Higher compliance with these scripts seems to exist among women (Scappini & Fioravanti, 2022), potentially translating in women's behaviors aimed at suppressing their sexual preferences and being less sexually assertive (Velten & Margraf, 2023). Despite this, this study's participants argue that nowadays, women seek professional help more easily and have more knowledge about sexual problems. These results are congruent with a recent study about the perceptions of university students (Amaro et al., 2021) that demonstrated that the sexual double standard persists, although with some weakening and the emergence of alternative patterns (e.g., women are moving away from a passive role in sexual contexts).

These findings by Amaro et al. (2021) align with other results that sustain that beliefs about sexual function are socio-cognitive and shared by men and women (Pascoal et al., 2017). These beliefs about sexual function frame the way people relate to each other in sexual contexts and can shape relational dynamics and, consequently, influence the experience of SDRSF. Rigid beliefs can create emotional disconnection that may be an obstacle to the establishment of intimacy (Topkaya et al., 2023) and, in turn, increase SDRSF. Also, rigid beliefs may pressure one to perform and meet unrealistic standards and may create repression of desire for aspects that do not meet the social norms and that can result in internal conflict and exacerbate, once again, SDRSF. According to cognitive models of sexual dysfunction, these inflexible, unrealistic, and, sometimes, erroneous sexual beliefs contribute to the susceptibility of developing sexual dysfunctions (Moura et al., 2023; Nobre, 2023).

An essential factor highlighted by the participants of this study concerns how the internalization of gender roles and genderized sexual beliefs impacts the way SDRSF is expressed in relationships. Considering there is a portrayed subtheme that focuses on relational dynamics between partners, this interrelation supports that the factors associated with SDRSF are intertwined and should be seen as mutually influential. Literature shows that lower relationship satisfaction predicts SDRSF (Attaky et al., 2021; Burri et al., 2011; Nickull et al., 2022). More specifically, Attaky et al. (2021) demonstrated that SDRSF in heterosexual women with sexual problems was predicted by their partner's level of sexual satisfaction. Still, in heterosexual women without sexual problems, SDRSF in women was predicted only by their level of sexual satisfaction. These results about relational dynamics between partners affecting the experience of SDRSF align with the participants' opinions in this study, which reinforces that the SDRSF experience also has a relational character, and to understand it, we need to deepen the interaction between relational dynamics and sexual outcomes.

Considering that sexuality is seen as the barometer of the quality of the relationship (Sprecher et al., 2006), individuals may feel pressured to perform sexually to meet societal and personal expectations about sexuality in the specific context of a relationship, which can create a barrier to acknowledging and addressing sexual difficulties or challenges within the relationship to prevent its dissolution. Consequently, SDRSF, such as the desire discrepancy mentioned by some participants, is associated with lower sexual satisfaction (Fischer et al., 2021) and can undermine the relationship. On the other hand, people who are not in committed relationships feel less pressure toward sexual performance, which may reflect that individuals who are not committed are more likely to prioritize their sexual satisfaction over their sex partners, as they do not have a long-term emotional connection (Zheng et al., 2020), and resulting in less SDRSF. This seems to indicate that pressure toward sexual performance may derive from diverse sources and may be exerted within relationships and be a risk factor that develops and perpetuates SDRSF. People who are not in committed relationships may feel less compelled to conform to societal norms and expectations regarding sexual behavior, as there is no expectation of future social interactions with a casual or non-committed sex partner (Alamsyah, 2022). However, people with SDRSF who are not in committed relationships may also experience shame related to sexual activity associated with feelings of inadequacy and fear of rejection by others (Pyke, 2020). When people experience shame, that may lead them to avoid both emotional and/or sexual relationships (Fischer & Træen, 2022). Considering that interpersonal factors affect SDRSF and that being single or in a relationship seems to have distinct effects on the experience of SDRSF, these may be regulated by individual factors (e.g., coping mechanisms) that will shape the impact that interpersonal factors have on personal experience of SDRSF (Zheng et al., 2020).

The third theme, running up that hill, focuses on individual risk factors for the development and persistence of SDRSF. The subtheme levels of sexual function demonstrated that the severity of sexual function problems is a key component of SDRSF that seems to be more important than merely the presence or absence of problems with sexual function. This result was expected since the literature shows that lower levels of sexual function are associated with higher levels of SDRSF (Hayes et al., 2008; Pâquet et al., 2018).

The subtheme of physical illness related to clinical organic conditions, such as diabetes and cardiovascular problems, is in line with previous research (Foley, 2016; Sansone et al., 2022; Terentes-Printzios et al., 2022) that shows that sexual dysfunction, including SDRSF, may arise from a specific illness (e.g., central nervous system lesions), the physical changes linked to indirect impairment (e.g., fatigue) or the psychological impact of the disease (e.g., low self-esteem). In line with this, such factors (physical and psychological changes due to illness) will be determinant or contribute to SDRSF.

Detrimental psychological factors, a subtheme, encompasses negative emotions and cognitive processes that contribute to the onset and perpetuation of SDRSF, aligning with existing literature (Gonçalves et al., 2022). These factors, including depression, anxiety symptoms (Guerreiro et al., 2023) and body image concerns (Alizadeh & Farnam, 2021; Nickull et al., 2022; Pascoal et al., 2019), may serve as indicators of vulnerability to SDRSF. Additionally, our findings suggest that personality traits, like perfectionism, may be associated with SDRSF. Perfectionism, characterized by its high standards and self-critical nature, fosters worry and rumination (Flett et al., 2016) and recognizes transdiagnostic factors contributing to psychological distress (Eley et al., 2020). Research in the sexual domain has underscored the association between worry and rumination, which is also associated with SDRSF (Nobre & Barlow, 2023), offering valuable insights for intervention.

Our results bring forth that SDRSF is a socially constructed phenomenon that needs to be approached from a psychopathology framework that considers its contextual framing, namely interpersonal and societal factors. Sexual healthcare providers should consider the influence of these contextual factors on individuals' experiences and tailor interventions accordingly.

Theoretical and clinical considerations

Our study is innovative because it aims to take a comprehensive view of SDRSF by gathering the perceptions of clinical sexologists regarding SDRSF, offering theoretical and clinical implications.

Our findings are parallel with the revised definitions in DSM-5-TR (APA, 2022) regarding sexual dysfunctions, specifically the additional features such as partner factors, relationship factors, individual vulnerability or cultural and medical factors. This alignment between our results, previous literature and the features displayed in DSM-5-TR regarding sexual dysfunctions emphasizes the need for a comprehensive approach that encompasses various dimensions of understanding and intervention in SDRSF.

Considering the reference to psychological vulnerability and maintenance factors, namely the reference to well-established proximal factors that are found across different psychopathological conditions (e.g., worry; difficulties with emotion regulation), the results suggest that a transdiagnostic approach could be taken at the clinical level to better understand and address sexual dysfunctions in clinical settings. Negative intrapersonal processes (e.g., difficulties with emotion regulation), personality traits and factors (e.g., perfectionism traits), and emotions (e.g., shame) suggest that a therapeutic approach aiming these dimensions are common to many other emotional difficulties may be indicated to the intervention in sexual dysfunctions.

The emphasis on social norms, with a particular emphasis on gender-related norms, as a source of SDRSF highlights that clinical sexologists and therapists should receive training to intervene in detrimental gender-related beliefs and acknowledge that socio-structural factors develop different gender-related sexual norms (Álvarez-Muelas et al., 2023). These can affect SDRSF experienced by women and men in different ways. Being aware of these gender norms and how they affect the experience of SDRSF could help promote equality and patient empowerment.

This study also innovates by suggesting that clinical sexologists should undergo comprehensive training to assess and handle communication patterns, conflict resolution strategies, power dynamics and intimacy and interpersonal challenges found in sexual (dys)function so they can master the unique dynamics of interpersonal relationships and couples' interactions. Therefore, a systemic therapy approach to training could be considered (Ferreira & Narciso, 2021).

Finally, this study makes a significant theoretical and clinical contribution to understanding SDRFSF in research and clinical settings by setting a conceptual framework that can serve as an initial step to guide future research aiming to broaden empirical knowledge and support and expand existing guidelines (APA, 2022) for clinical assessment and intervention in SDRSF.

Limitations and future research

The current study has limitations that need to be acknowledged. The participants are professionals sharing the same nationality and inevitably anchored to a shared cultural perspective regarding sexual issues and the healthcare system. Additionally, these professionals share similar education and training by SPSC in Portugal and are mainly grounded in a cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) approach. Consequently, the participants may be biased towards a CBT perspective, and this shared foundation may lead to convergence or similar conceptualizations of SDRSF. It is possible that these participants were more motivated and reflected on their practice than those who did not choose to participate in our research. We did not explore how clinician's own personal experiences with sexual development could inform their professional choices and professional development and, subsequently, their clinical practice and how this situated knowledge could inform their testimonies. We consider this an important area for research that we did not explore in the current study.

In our view, this study needs to be deepened and complemented by research that captures how clinicians' conceptualization of SDRSF in clinical settings affects their therapeutic options and how they select treatment strategies. It would also be important to explore how laypeople define their experience of SDRSF and sexual distress related to partnered sexuality to expand current findings. Finally, we advocate for developing a targeted measure of sexual distress that accurately captures SDRSF or distress in the context of partnered sexual activity, integrates the specificities found in the present study, overcominggaps identified regarding existing measures, namely their broad focus.

Final considerations

This study brings to light a set of essential components that should be considered in research and clinical practice related to SDRSF as perceived by a set of clinical sexologists. Our findings underscore the profound inter-influence of psychological determinants, interpersonal dynamics, and societal dominant norms in shaping the experience of SDRSF. Considering that analytical generalization occurs when researchers have results that can inform a concept or theory (Kuklick et al., 2016; Smith, 2018), this preliminary work about SDRSF should be considered as an initial framework that can be used as a guide for clinicians working in the field of sexual distress related to partnered sexual activity. This framework can also serve as a benchmark to guide future studies that allow it to be improved and expanded over time

Based on the findings, we can conceptualize SDRSF as a distressing emotional experience that encompasses sexual activities SDRSF is furthermore characterized by a sense of helplessness- related to personal, interpersonal, and societal expectations about normal sexuality, and sexual function- which seems to deteriorate the possibility to experience sexual pleasure during partnered face-to-face interactions.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

Declaration of Generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

The authors used Grammarly to check for spelling mistakes, grammatical problems and punctuation inaccuracies. After using this tool, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed. The authors take full responsibility for the publication's content.

Data statement

Due to the nature of the questions asked in this study, survey respondents were assured raw data would remain confidential and would not be shared.

Funding

This work was supported by the FCT - Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, I.P. under grant SFRH/BD/146833/2019 to the first author, and within the scope of the project 2022.09087.PTDC (https://doi.org/10.54499/2022.09087.PTDC). This work is partially funded by the Center for Psychology at the University of Porto, Portuguese Science Foundation (FCT UIDB/00050/2020), and by Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia (FCT), under HEI-Lab R&D Unit (UIDB/05380/2020, https://doi.org/10.54499/UIDB/05380/2020).

Acknowledgments

The authors sincerely thank the clinical sexologists who willingly participated in this study, acknowledging their valuable time and collaboration.

References

- Alamsyah A.A. Alliant International University, San Francisco; 2022. Cost and benefit analysis of romantic and casual sexual relationships: a prediction.https://shorturl.at/cvN29 [Doctoral dissertation]. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. [Google Scholar]

- Alarcão V., Ribeiro S., Almeida J., Giami A. Clinical practice in Portuguese sexology. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy. 2017;43(8):760–773. doi: 10.1080/0092623X.2016.1266537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alizadeh A., Farnam F. Coping with dyspareunia, the importance of inter and intrapersonal context on women's sexual distress: A population-based study. Reproductive Health. 2021;18(1):161. doi: 10.1186/s12978-021-01206-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Álvarez-Muelas A., Gómez-Berrocal C., Osorio D., Noe-Grijalva H.M., Sierra J.C. Sexual double standard: A cross-cultural comparison of young adults Spanish, Peruvian, and Ecuadorian people. Sexuality Research and Social Policy. 2023;20(2):705–713. doi: 10.1007/s13178-022-00714-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Amaro H., Alvarez M.-J., Ferreira J.A. Portuguese college students’ perceptions about the social sexual double standard: Developing a comprehensive model for the social SDS. Sexuality & Culture. 2021;25(2):733–755. doi: 10.1007/s12119-020-09791-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc; 2022. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5-TR™ (5th ed. text revision) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Attaky A., Schepers J., Kok G., Dewitte M. The role of sexual desire, sexual satisfaction, and relationship satisfaction in the sexual function of Arab couples living in Saudi Arabia. Sexual Medicine. 2021;9(2) doi: 10.1016/j.esxm.2020.100303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banbury S., Lusher J., Snuggs S., Chandler C. Mindfulness-based therapies for men and women with sexual dysfunction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sexual and Relationship Therapy. 2023;38(4):533–555. doi: 10.1080/14681994.2021.1883578. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bancroft J., Loftus J., Long J.S. Distress about sex: A national survey of women in heterosexual relationships. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2003;32(3):193–208. doi: 10.1023/A:1023420431760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basson R., Leiblum S., Brotto L., Derogatis L., Fourcroy J., Fugl-Meyer K., Graziottin A., Heiman J.R., Laan E., Meston C., Schover L., van Lankveld J., Schultz W.W. Revised definitions of women's sexual dysfunction. Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2004;1(1):40–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2004.10107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beato A.F., Pascoal P.M., Rodrigues J. The impact of digital media on sexuality: A descriptive and qualitative study. International Journal of Impotence Research. 2024:1–11. doi: 10.1038/s41443-024-00865-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bois K., Bergeron S., Rosen N., Mayrand M.-H., Brassard A., Sadikaj G. Intimacy, sexual satisfaction, and sexual distress in vulvodynia couples: An observational study. Health Psychology: Official Journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association. 2016;35(6):531–540. doi: 10.1037/hea0000289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun V., Clarke V. SAGE Publications; 2021. Thematic analysis: a practical guide. [Google Scholar]

- Braun V., Clarke V. To saturate or not to saturate? Questioning data saturation as a useful concept for thematic analysis and sample-size rationales. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health. 2021;13(2):201–216. doi: 10.1080/2159676X.2019.1704846. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Braun V., Clarke V. Conceptual and design thinking for thematic analysis. Qualitative Psychology. 2022;9(1):3–26. doi: 10.1037/qup0000196. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Braun V., Clarke V. Supporting best practice in reflexive thematic analysis reporting in Palliative Medicine: A review of published research and introduction to the Reflexive Thematic Analysis Reporting Guidelines (RTARG) Palliative Medicine. 2024;0(0):1–9. doi: 10.1177/02692163241234800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brotto L., Atallah S., Johnson-Agbakwu C., Rosenbaum T., Abdo C., Byers E.S., Graham C., Nobre P., Wylie K. Psychological and interpersonal dimensions of sexual function and dysfunction. Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2016;13(4):538–571. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2016.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns P.B., Rohrich R.J., Chung K.C. The levels of evidence and their role in evidence-based medicine. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2011;128(1):305–310. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e318219c171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burri A., Rahman Q., Spector T. Genetic and environmental risk factors for sexual distress and its association with female sexual dysfunction. Psychological Medicine. 2011;41(11):2435–2445. doi: 10.1017/S0033291711000493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byers E.S. How well does the traditional sexual script explain sexual coercion? Journal of Psychology & Human Sexuality. 1996;8(1–2):7–25. doi: 10.1300/J056v08n01_02. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carrozzino D., Patierno C., Pignolo C., Christensen K. The concept of psychological distress and its assessment: A clinimetric analysis of the SCL-90-R. International Journal of Stress Management. 2022;30(3):235–428. doi: 10.1037/str0000280. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Costa I.B., Manão A.A., Pascoal P.M. Clinical sexologists’ perceptions of the potentials, downfalls, and best practices for digitally delivered therapy: A lesson from lockdown due to COVID-19 in Portugal. Behavioral Sciences. 2023;13(5):376. doi: 10.3390/bs13050376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowie L., Braun V. Between social and biomedical explanation: Queer and gender diverse young people's explanations of psychological distress. Psychology & Sexuality. 2022;13(5):1179–1190. doi: 10.1080/19419899.2021.1933147. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dalgleish T., Black M., Johnston D., Bevan A. Transdiagnostic approaches to mental health problems: Current status and future directions. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2020;88(3):179–195. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewitte M., Carvalho J., Giovanni G., Limoncin E., Pascoal P., Reisman Y., Štulhofer A. Sexual desire discrepancy: A position statement of the european society for sexual medicine. Sexual Medicine. 2020;8(2):121–131. doi: 10.1016/j.esxm.2020.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan D. Plural masculinities: The remaking of the self in private life. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 2012;14(1):117–119. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2011.613564. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eley D.S., Bansal V., Leung J. Perfectionism as a mediator of psychological distress: Implications for addressing underlying vulnerabilities to the mental health of medical students. Medical Teacher. 2020;42(11):1301–1307. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2020.1805101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira L.C., Narciso I. In: Manual de terapia familiar: teoria, avaliação e intervenção sistémica. Gouveia-Pereira M., Miranda M.P., editors. Pactor; 2021. Sexualidade e terapia de casal: Estado da arte da investigação e intervenção; pp. 103–111. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer N., Štulhofer A., Hald G.M., Carvalheira A., Træen B. Sexual satisfaction in older heterosexual couples from four European countries: Exploring the roles of actual and perceived discrepancy in sexual interest. The Journal of Sex Research. 2021;58(1):64–73. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2020.1809615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer N., Træen B. Prevalence of sexual difficulties and related distress and their association with sexual avoidance in Norway. International Journal of Sexual Health. 2022;34(1):27–40. doi: 10.1080/19317611.2021.1926040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flett G.L., Nepon T., Hewitt P.L. In: Perfectionism, health, and well-being. Sirois F.M., Molnar D.S., editors. Springer International Publishing/Springer Nature; 2016. Perfectionism, worry, and rumination in health and mental health: A review and a conceptual framework for a cognitive theory of perfectionism; pp. 121–155. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Foley F.W. In: Primer on multiple sclerosis. Giesser B.S., editor. Oxford University Press; 2016. Assessment and treatment of sexual dysfunction in multiple sclerosis; pp. 249–258. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Forbes M.K., Baillie A.J., Eaton N.R., Krueger R.F. A place for sexual dysfunctions in an empirical taxonomy of psychopathology. Journal of Sex Research. 2017;54(4–5):465–485. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2016.1269306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forbes M.K., Baillie A.J., Schniering C.A. Should sexual problems be included in the internalizing spectrum? A comparison of dimensional and categorical models. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy. 2016;42(1):70–90. doi: 10.1080/0092623X.2014.996928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford J.V. Unwanted sex on campus: The overlooked role of interactional pressures and gendered sexual scripts. Qualitative Sociology. 2021;44(1):31–53. doi: 10.1007/s11133-020-09469-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Frost R., Donovan C. The development and validation of the sexual and relationship distress scale. Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2018;15(8):1167–1179. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2018.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giami A., Michaels S. Sexology as a profession in France: Preliminary results of a national survey (2019) Sexologies. 2020;29(2):57–67. doi: 10.1016/j.sexol.2020.03.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gonçalves W.S., Gherman B.R., Abdo C.H.N., Coutinho E.S.F., Nardi A.E., Appolinario J.C. Prevalence of sexual dysfunction in depressive and persistent depressive disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Impotence Research. 2022;35(4):340–349. doi: 10.1038/s41443-022-00539-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerreiro P.P., Raposo C.F., Salvador Á., Manão A.A., Pascoal P.M. A transdiagnostic approach to sexual distress and pleasure: The role of worry, rumination, and emotional regulation. Current Psychology. 2023;43:15385–15396. doi: 10.1007/s12144-023-05320-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gunst A., Werner M., Waldorp L.J., Laan E.T.M., Källström M., Jern P. A network analysis of female sexual function: Comparing symptom networks in women with decreased, increased, and stable sexual desire. Scientific Reports. 2018;8(1):15815. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-34138-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes R.D., Dennerstein L., Bennett C.M., Sidat M., Gurrin L.C., Fairley C.K. Risk factors for female sexual dysfunction in the general population: Exploring factors associated with low sexual function and sexual distress. Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2008;5(7):1681–1693. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2008.00838.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helmert C., Fleischer T., Speerforck S., Ulke C., Altweck L., Hahm S., Muehlan H., Schmidt S., Grabe H.J., Völzke H., Schomerus G. An explorative cross-sectional analysis of mental health shame and help-seeking intentions in different lifestyles. Scientific Reports. 2023;13(1):10825. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-37955-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrickx L., Gijs L., Enzlin P. Who's distressed by sexual difficulties? Exploring associations between personal, perceived partner, and relational distress and sexual difficulties in heterosexual men and women. Journal of Sex Research. 2019;56(3):300–313. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2018.1493570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrickx L., Gijs L., Janssen E., Enzlin P. Predictors of sexual distress in women with desire and arousal difficulties: Distinguishing between personal, partner, and interpersonal distress. Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2016;13(11):1662–1675. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2016.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinchliff S., Lewis R., Wellings K., Datta J., Mitchell K. Pathways to help-seeking for sexual difficulties in older adults: Qualitative findings from the third National Survey of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles (Natsal-3) Age and Ageing. 2021;50(2):546–553. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afaa281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson N.C., Newman M.G. Anxiety and depression as bidirectional risk factors for one another: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychological Bulletin. 2017;143(11):1155–1200. doi: 10.1037/bul0000111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotov R., Krueger R.F., Watson D., Achenbach T.M., Althoff R.R., Bagby R.M., Brown T.A., Carpenter W.T., Caspi A., Clark L.A., Eaton N.R., Forbes M.K., Forbush K.T., Goldberg D., Hasin D., Hyman S.E., Ivanova M.Y., Lynam D.R., Markon K.…Zimmerman M. The Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology (HiTOP): A dimensional alternative to traditional nosologies. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2017;126(4):454–477. doi: 10.1037/abn0000258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuklick C.R., Gearity B.T., Thompson M., Neelis L. A case study of one high-performance baseball coach's experiences within a learning community. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health. 2016;8(1):61–78. doi: 10.1080/2159676X.2015.1030343. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lafortune D., Girard M., Dussault É., Philibert M., Hébert M., Boislard M.-A., Goyette M., Godbout N. Who seeks sex therapy? Sexual dysfunction prevalence and correlates, and help-seeking among clinical and community samples. PLoS One. 2023;18(3) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0282618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallory A.B. Dimensions of couples’ sexual communication, relationship satisfaction, and sexual satisfaction: A meta-analysis. Journal of Family Psychology. 2022;36(3):358–371. doi: 10.1037/fam0000946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manão A.A., Martins E., Pascoal P.M. What sexual problems does a sample of LGB+ people report having, and how do they define sexual pleasure: A qualitative study to inform clinical practice. Healthcare. 2023;11(21):2856. doi: 10.3390/healthcare11212856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mestre-Bach G., Blycker G.R., Potenza M.N. Behavioral therapies for treating female sexual dysfunctions: A state-of-the-art review. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2022;11(10):2794. doi: 10.3390/jcm11102794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meuser M., Nagel U. In: Interviewing experts. research methods series. Bogner A., B. Littig, Menz W., editors. Palgrave Macmillan; London: 2009. The expert interview and changes in knowledge production. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moura C.V., Vasconcelos P.C., Carrito M.L., Tavares I.M., Teixeira P.M., Nobre P.J. The role of men's sexual beliefs on sexual function/dysfunction: A systematic review. The Journal of Sex Research. 2023;60(7):989–1003. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2023.2218352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nickull S., Källström M., Jern P. An exploratory network analysis of sexual and relationship satisfaction comparing partnered cisgendered men and women. The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2022;19(5):711–718. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2022.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nimbi F.M., Rossi V., Tripodi F., Luria M., Flinchum M., Tambelli R., Simonelli C. Genital pain and sexual functioning: Effects on sexual experience, psychological health, and quality of life. The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2020;17(4):771–783. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2020.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nobre P.J. In: Encyclopedia of sexuality and gender. Lykins A.D., editor. Springer; Cham: 2023. Nobre's cognitive-emotional model of sexual dysfunction; pp. 1–9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nobre P.J., Barlow D.H. In: Encyclopedia of sexuality and gender. Lykins A.D., editor. Springer; Cham: 2023. Barlow's cognitive-affective model of sexual dysfunction; pp. 1–9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nobre P., Gouveia J.P., Gomes F.A. Sexual Dysfunctional Beliefs Questionnaire: An instrument to assess sexual dysfunctional beliefs as vulnerability factors to sexual problems. Sexual and Relationship Therapy. 2003;18(2):171–204. doi: 10.1080/1468199031000061281. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pâquet M., Rosen N.O., Steben M., Mayrand M.H., Santerre-Baillargeon M., Bergeron S. Daily anxiety and depressive symptoms in couples coping with vulvodynia: Associations with women's pain, women's sexual function, and both partners’ sexual distress. Journal of Pain. 2018;19(5):552–561. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2017.12.264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascoal P.M., Alvarez M.J., Pereira C.R., Nobre P. Development and initial validation of the beliefs about sexual functioning scale: A gender invariant measure. The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2017;14(4):613–623. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2017.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]